“Serenity is the greatest demonstration of power”

Iknow people who are great admirers of Japanese society and its concepts of harmony. I myself find its aesthetics and manners charming, and I have always been passionate about its cuisine, culture, and elegance. However, behind this formal framework, there is often a sacrifice of individuality. The suicide rate, as the ultimate marker of the failure of a human system, is extraordinarily high, and the multiplicity of misfits seeking compensation for a rigid system of social relations and personal satisfaction is overwhelming and incredible. Bars where you can rent a cat for an hour, extraordinary and colorful sexual fetishes, a pathological search for a space for all kinds of obsessions resulting from a crushed identity, which leads to an urgent need for a sense of belonging, or a frenzy like the hatching and explosion of a suffocating environment. In the background, the Japanese fascination with robots says it all...

We have to understand that this system did not arise out of nowhere, but from very particular geographical, historical, and environmental conditions; in the end, everything is a product of the environment. Extremely high population levels, lack of space, and the isolationism to which their society was subjected for centuries established the need for an intense hierarchical and social order. It is not the same to spend an hour locked in an elevator with people as it is to spend an hour in the open air! Surviving as a group in such conditions shapes character and behavior. This model undoubtedly has its advantages: it is an orderly, hyperproductive people, capable of weighing the details of their actions like no other, based on a specialization that is undoubtedly neurotic, but with excellent results.

The alienation generated by this system, the submission to it, the lack of questioning, produce people with immense identity problems who justify themselves by what they do rather than who they are.

The great achievement of the West, its greatest contribution to humanity, has been the concept of the individual, something generally foreign to Eastern cultures, where individuality is a luxury that only those at the top of the social pyramid, who ran the show, could afford to a certain extent.

The conceptual models produced by each type of culture are regulated by norms that are often unwritten but self-assumed, and which at some point take shape in the form of moral principles. Morality is thus a social construct and, ultimately, a system to which one can cling in order to avoid having to think.

If morality worked to change people, in monotheistic cultures we would all be saints and live in paradise on earth. But morality or etiquette does not change people, it only constrains them to shape their socialization, sooner rather than later (fanatics sign up for everything!) becoming a system of manipulation.

The same is true of laws. Modern civil society does not differ much from religions in its purpose of creating an earthly paradise, this time a secular one, through legislation, and they do so ad nauseam and with lubricity. But putting on a girdle does not make you lose weight, it makes you look thin.

Apart from the usefulness of bringing order to chaos in order to normalize coexistence, neither laws nor morals change anyone. Do we ever really change? Structurally, human beings only change with the passage of time. Those born with blue eyes will have them all their lives, those born blond will go bald or gray, but they will never be brunette. Functionally, time does its thing, and with each phase of life, we adapt from what our nature and individuality push us to change. Our essence, however, is shaped by what it is, through what it does, and how it lives the experiences that slowly, day by day, determine it.

Destiny already exists in a structural form, predefining our continent, our body, nature, desires... and functionally, predetermining our environment, family, country, etc. Freedom is a narrow corridor limited by these two spheres, a corridor that nevertheless makes a big difference.

Faced with a bigamous and paradoxical destiny, human beings decide at every moment and in their becoming to change their destiny. Freedom is thus established as the sine qua non for evolutionary processes, hence corsets, molds, labels, or morals are nothing but a mistake, an inconvenience in the process of experimentation and personal growth.

The truth is that we do not change, but rather we modulate ourselves based on who we are, and this process can be conscious or unconscious. When we surrender to evolutionary forces, we need consciousness; otherwise, we will be crushed by the inertia of the material, the instinctive, and the animal, so that life for many is reduced to being born, eating, defecating, reproducing, and dying.

Only within a framework of free will can we evolve, raising our vibrational tone, not in a spurious and affected way, but in a true and firm way. Hence, rules, morals, or labels, far from being a solution, can even become a problem. We can spend half our lives trying to remove the straitjackets imposed on us, psychotherapy sessions, ayahuasca ceremonies, etc... pain and folly just to be able to loosen our belts and let out that fart that has been troubling our hearts since childhood.

Underlying this approach, there is always a question that resonates: Change for what, why? Morals, laws, and educational etiquette have a social purpose, but they do not solve anything on an individual level.

The question we ask ourselves is really very profound: What is the purpose of life? Is there such a thing?

When I was a young man, one summer day on the Alberche River, sitting on a rock, as naked as the day we were born, my teacher Sánchez Bárrio gave me the answer.

“The purpose of life?” said Sánchez Bárrio.

“Look at nature! She is the great Teacher who never makes mistakes! What is the purpose of an apple tree?”

“To give apples,” I replied.

“Right? So Tucci's purpose will be to make tuccistuff!”

Life is a process of bringing out what we have inside, of exchanging (in the best of cases...) energy for wisdom, of letting go of baggage, while the winds of life inevitably smooth out your rough edges, eliminate the excess, trim away what is superfluous, leaving only the essential.

We come to experience, resolve, readjust, undergo transformations, fulfill, give, share, and even honor what surrounds us, if we are capable.

Every process of evolution follows universal guidelines, namely: Forward, upward, inward, and finally toward the whole. There is no belt, girdle, or bra that will change who you are; fear of punishment by the law will not make you better or change you internally either. Only the process of realization opens the doors to evolutionary processes; transcendence requires the participation of the united will and consciousness.

Let those who practice “goodism” swear by the universal idealism of forms, for they will end up wanting to impose their own vision on others; it does not work and will never work.

Respecting the freedom of others cannot be reduced to a simple “posture”; it must be something taken to its ultimate consequences.

We can only accompany others in this process; teaching is above all educating by example, always remembering that what may be valid for me will not necessarily be valid for others and that evolution can only be the fruit of an inner desire.

There is no paradise on earth! Those who try to impose it always end up creating hell.

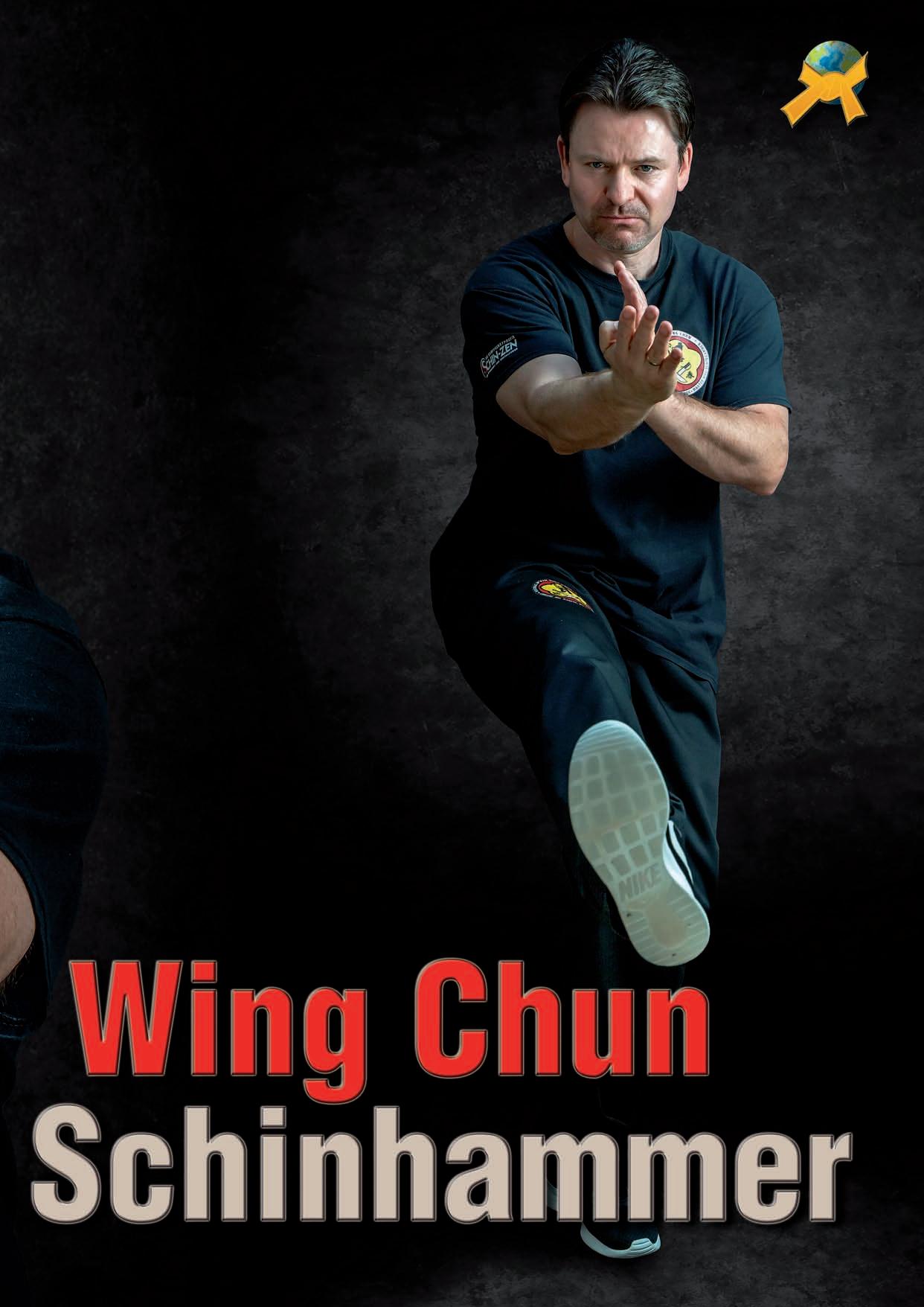

The art of simplicity – why Wing Chun is more relevant today than ever before

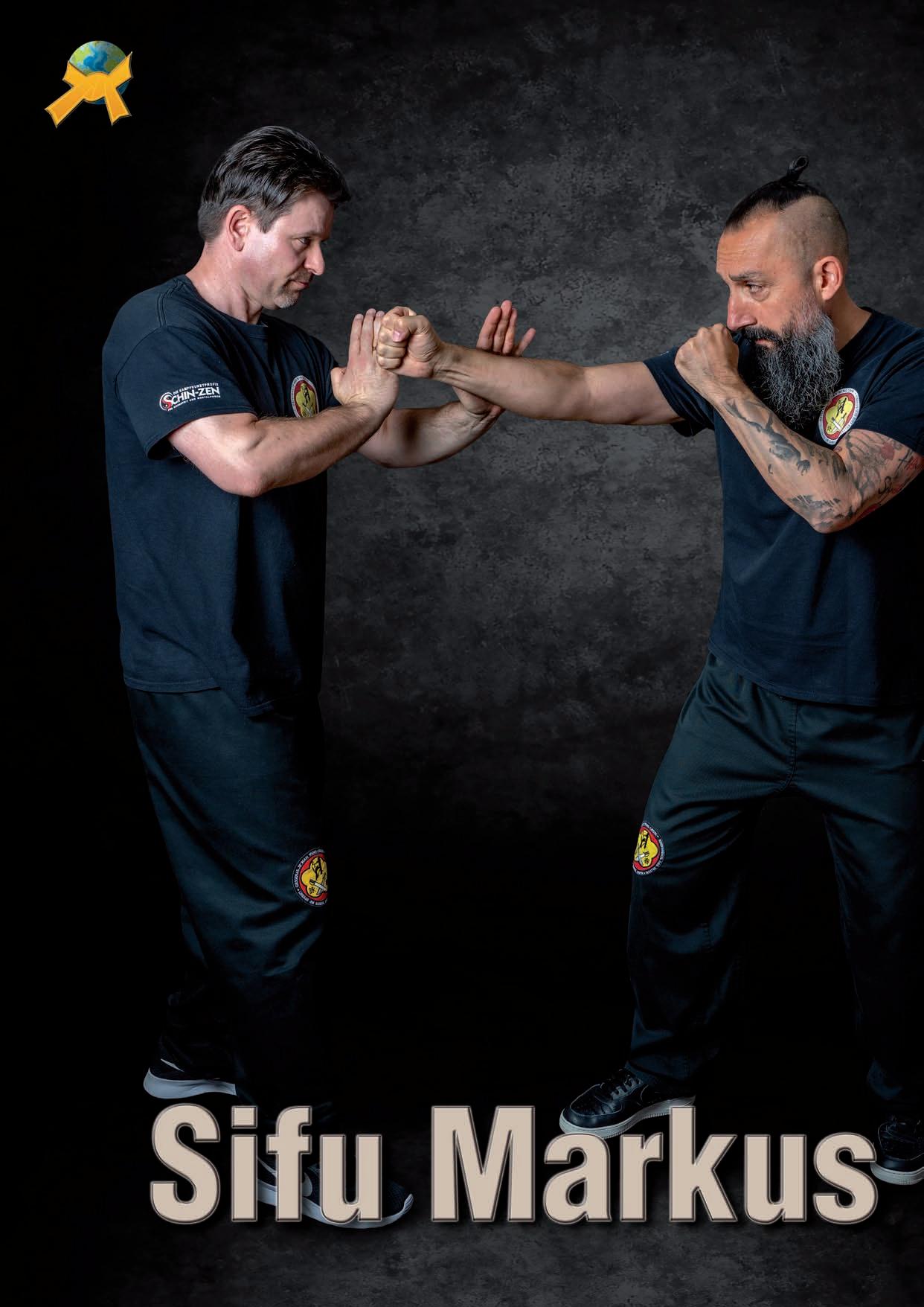

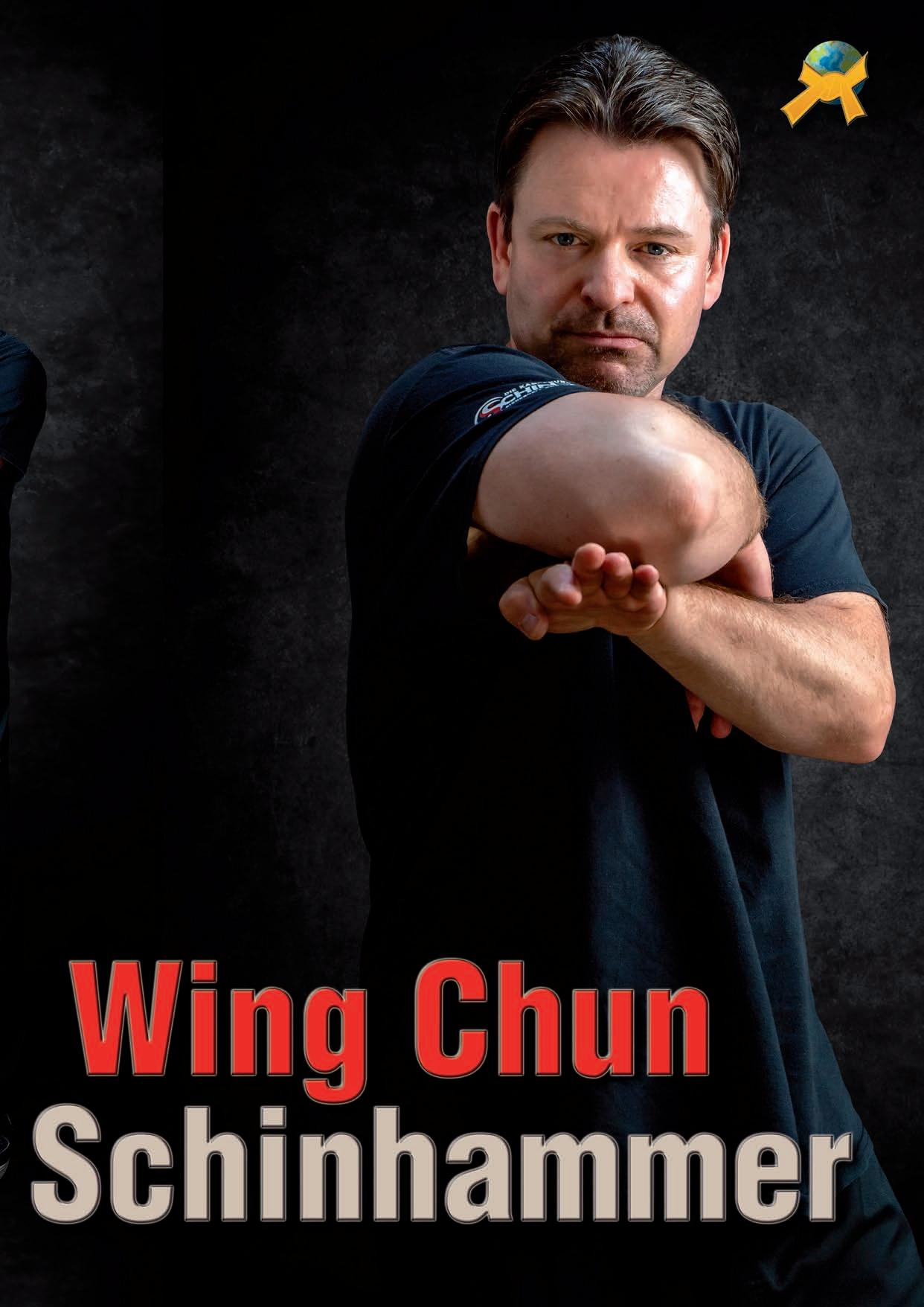

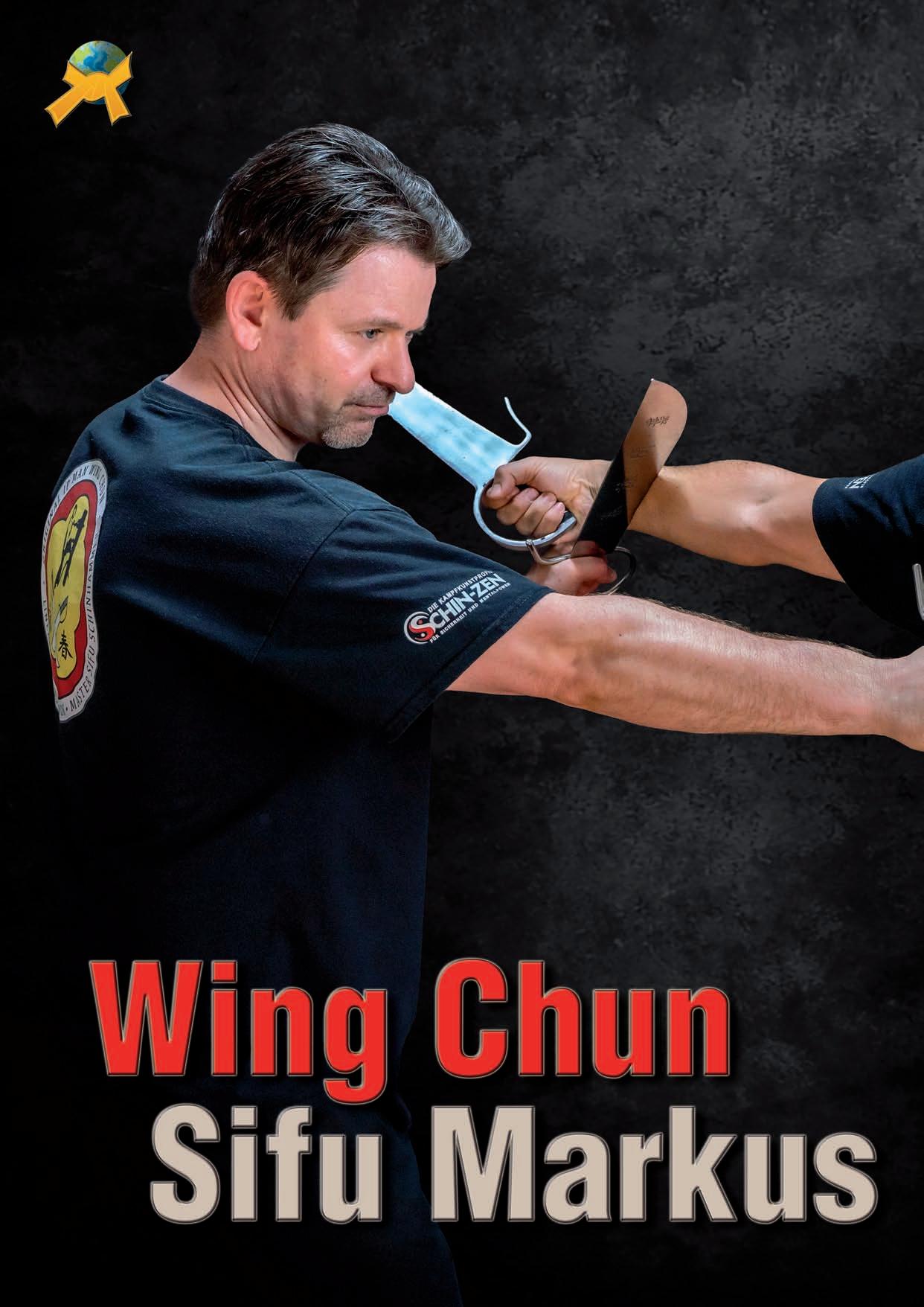

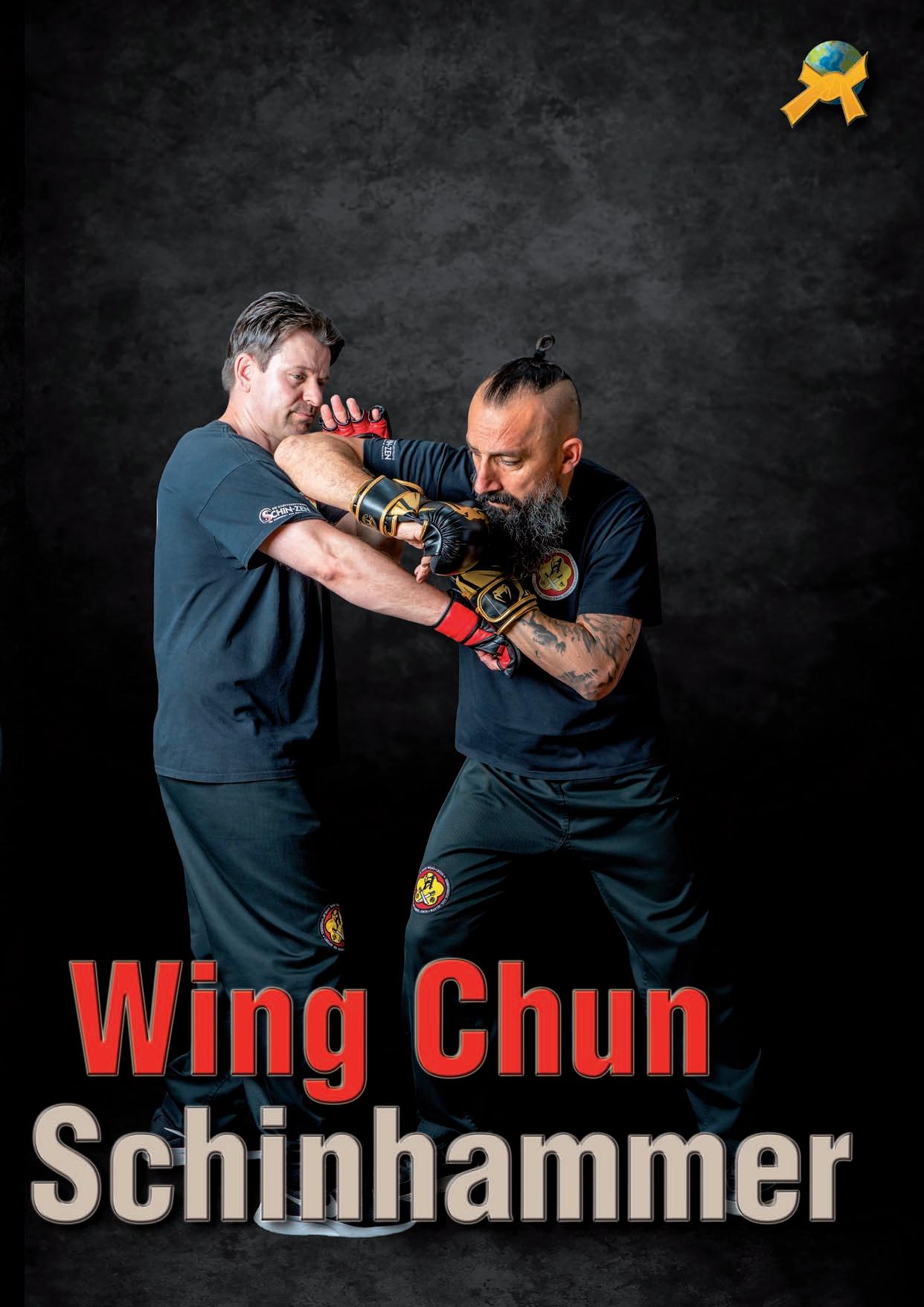

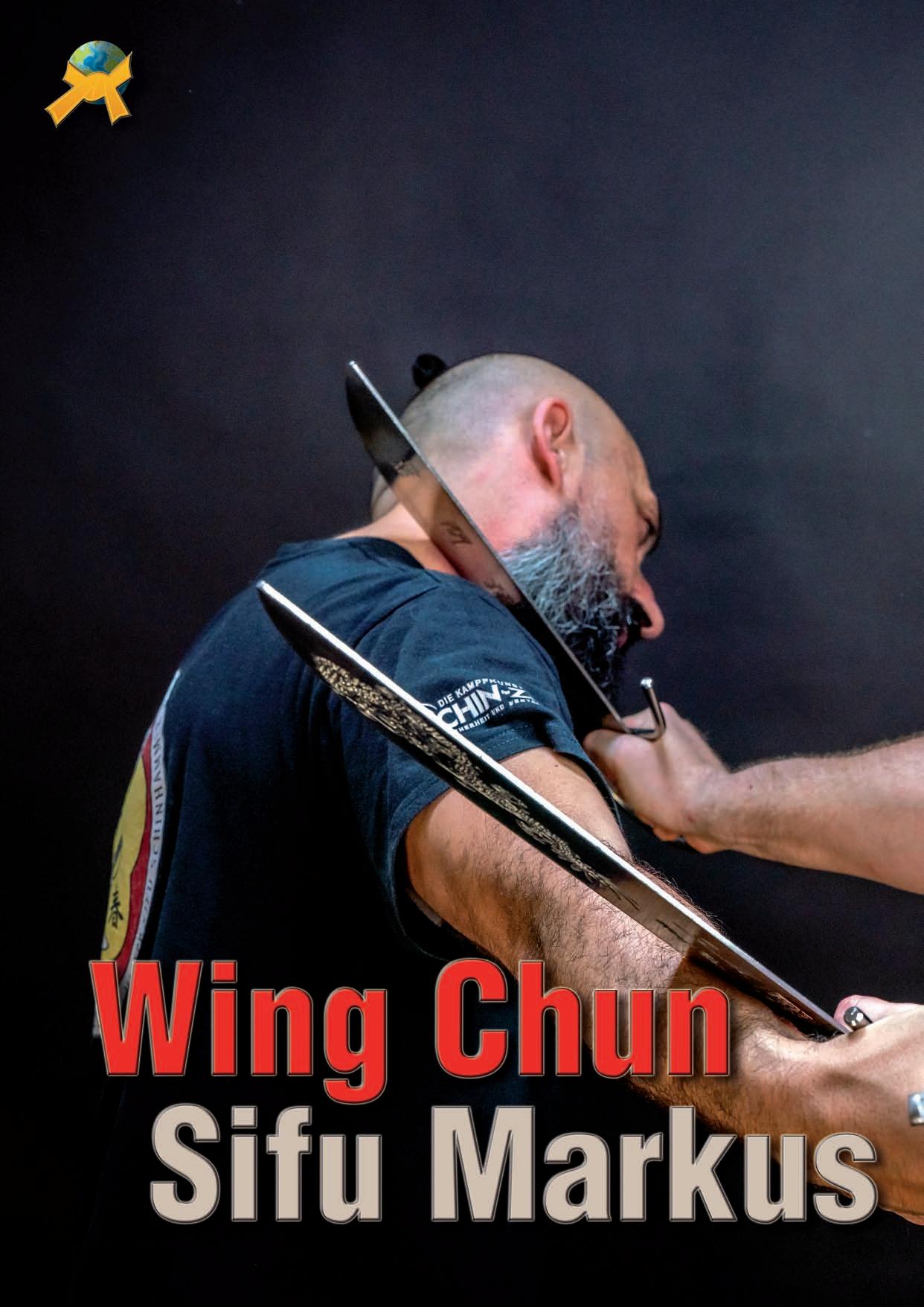

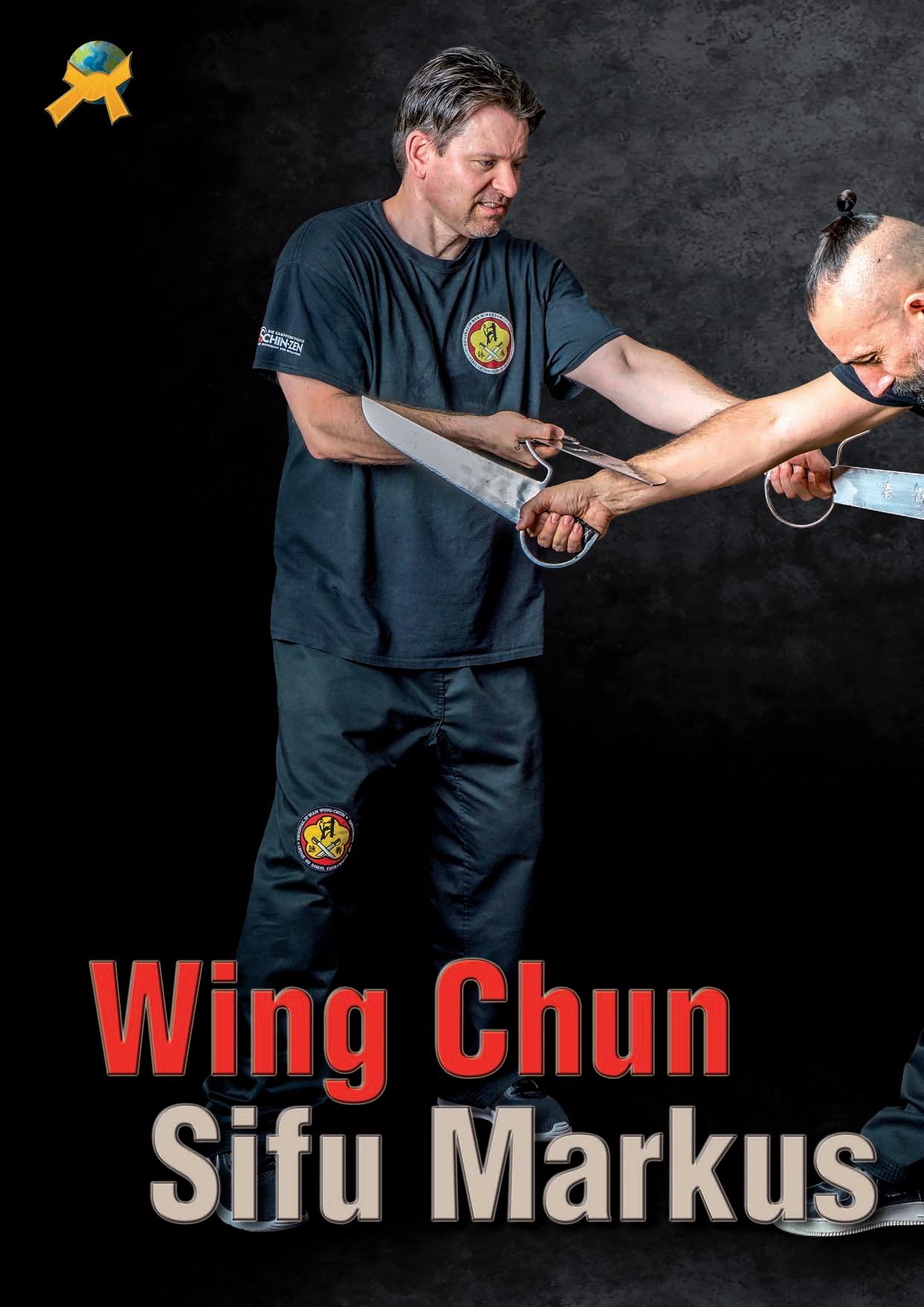

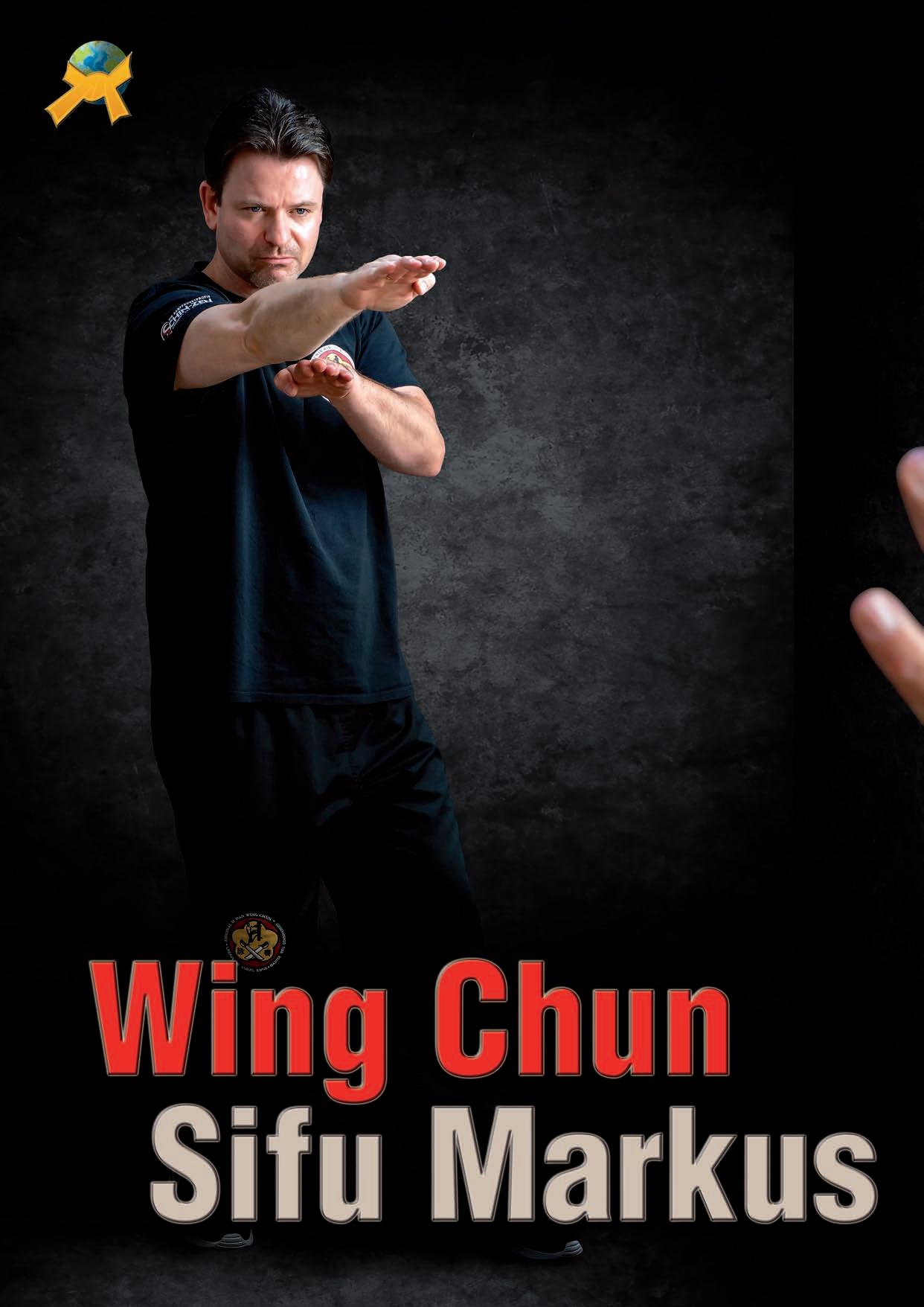

By Sifu Markus Schinhammer, Wing Chun master student of Grand Master Samuel Kwok

In a world that is becoming ever faster, louder, and more complex, many people are looking for ways to find peace again. They long for clarity, focus, and a sense of inner strength. This is precisely the core of Wing Chun – a martial art that appears simple at first glance, but is in fact one of the most profound systems of selfdefense and personal development ever created. I myself have been practicing Wing Chun for many decades, and although I have learned, passed on, and deepened countless techniques, the central insight remains the same: true strength lies in simplicity. The longer I train and teach, the clearer it becomes to me that the principles on which Wing Chun is based are more relevant today than ever before. In an age of sensory overload, time pressure, and constant distraction, many people long for a clear, reduced, honest path. A path that does not create even more complexity, but helps to penetrate it. Wing Chun is just such a path—direct, clear, unadorned.

Wing Chun is not a martial art of showmanship or pomp. It is the opposite of that. While many combat systems rely on complex sequences of movements, spectacular kicks, or acrobatic elements, Wing Chun reduces everything to the essentials: short distances, direct lines, maximum efficiency. Every movement has a purpose, every step a task, every contact a piece of information. There are no superfluous movements, no ends in themselves.

This simplicity is no coincidence. It is the result of centuries of observation, testing, and reduction. The question was asked again and again: What really works under pressure? What remains when you leave out everything decorative, everything playful? What remains is a system designed to function under stress, fear, and chaos. Wing Chun is therefore not only a method of self-defense, but also a principle of thinking. Those who learn to simplify complex things learn to see more clearly – in training as well as in everyday life.

Many beginners – and even some martial artists from other styles – confuse the word “simple” with “easy.” But Wing Chun is anything but easy. It is mercilessly honest. It does not forgive inaccuracy in structure, carelessness in contact, or ego displays. Simplicity in Wing Chun does not mean doing less, but rather not doing anything superfluous. And that is precisely what makes it so demanding.

You learn to shorten, refine, and refine your own movements more and more. You learn to let go— unnecessary tension, brute force, old patterns. You learn to realign your body, to find your center and stay there, even when pressure comes from outside. It's a process that takes years and is never really complete.

I remember many hours of training with my Sifu Grandmaster Samuel Kwok. I was often convinced that I had finally understood a technique. Then he would smile and say calmly, “When you think you understand, that's when understanding really begins.” That sentence has stayed with me. It sums up what Wing Chun is all about: it's not about ticking off lots of techniques, but about gaining a deeper and deeper understanding of what lies behind them.

We live in an age where complexity has become the norm. People juggle appointments, information, expectations. Their heads are full, their bodies tired, their attention fragmented. Many wish for more focus, more clarity, more inner peace. This is precisely where one of Wing Chun's great strengths lies.

In training, we learn to quiet our minds for a moment and enter into a state of awareness. We focus on posture, breathing, contact, and our own center. In Chi Sao—sticky arms training—we practice not only seeing stimuli, but feeling them. We train to take pressure, redirect it, absorb it, instead of resisting everything. What at first glance looks like fighting is actually training in presence.

Many of my students come to training with similar issues: stress at work, inner turmoil, sleep problems, difficulty concentrating. They want not only to become physically fitter, but also to find a balance to their everyday lives. Wing Chun offers them both. Through the clear structure of the forms, the repetition of basic movements, and the partnership work in Chi Sao, they experience something that is often missing in everyday life: the state of complete presence in the here and now.

One of the most important concepts in Wing Chun is the center— on several levels. Physically, it means the central line of the body, the protective axis through which we attack and defend. Those who lose their center are open, vulnerable, and unstable. That is why we learn from the very beginning to align our structure in such a way that we can protect and utilize the center at the same time.

But the center is not just an anatomical term. It is also an inner principle. Grandmaster Samuel Kwok once said to me, “If you lose your center, you lose yourself – in combat as in life.” This sentence has stayed with me to this day. It reminds me that Wing Chun is always about maintaining balance – between tension and relaxation, between alertness and calmness, between action and reaction.

Those who learn to stay centered during training will find that this carries over into other areas of life. People who practice Wing Chun seriously often report that they react more calmly, make clearer decisions, and are less easily thrown off course by external circumstances. Working on your physical center thus becomes work on your inner center.

A central component of Wing Chun training is Chi Sao, or “sticky arms” training. This is not about performing a set sequence of techniques, but about feeling. The contact between the arms should be lively, sensitive, and conscious. Instead of constantly thinking about what our partner might do next, we learn to feel it in their body.

In an age where so much is done via screens, theories, and abstractions, this is something enormously valuable. Chi Sao is immediate feedback. If I am too hard, I lose my balance. If I am too soft, I am pushed together. If I am too slow, I feel the gap. The body does not lie. The principle of yin and yang applies. There is not only hard or only soft. This experience trains not only responsiveness but also honesty with oneself.

My own journey in Wing Chun began like many others:with curiosity and respect. I was impressed by the clarity of the movements, the efficiency of the techniques, and the inner calm. Over time, the initial techniques became fixed structures, individual lessons became a daily routine, and a hobby became a vocation.

The opportunity to study intensively with Grandmaster Samuel Kwok and ultimately be recognized by him as a private master student was a turning point for me. Under his guidance, I learned not only to imitate Wing Chun, but to understand it. He placed great emphasis on precision—in posture, distance, angle, and energy. At the same time, he was always modest, calm, and clear. He didn't need big words; his presence and skill spoke for themselves.

As a master student, I have a dual responsibility: on the one hand, for my own ongoing learning, and on the other, for passing on this teaching to my students. I see myself as a link between the tradition I received from my Sifu and the modern training reality in my schools with children, teenagers, and adults.

A large part of my work today involves teaching Wing Chun to children and young people. At first glance, it may seem surprising to associate a seemingly “hard” martial art with young people. But this is precisely where the true strength of the system lies. Wing Chun is structured, clear, and logical—qualities that help children develop confidence and orientation.

Training children is not about raising little fighters, but strong personalities. Children learn to concentrate, follow instructions, treat their partners with respect, and at the same time recognize and protect their own boundaries. They learn that strength has nothing to do with volume or aggression, but with inner calm, clarity, and steadfastness.

Even in adult training, Wing Chun is much more than just a self-defense program. Many of my adult students come not only to challenge themselves physically, but also to find a balance to everyday life, reduce stress, and clear their minds. They appreciate that Wing Chun is not a competitive system in which you constantly have to measure yourself against others, but rather a path on which you can develop at your own pace.

In my schools, I attach great importance to preserving the traditional structure of Wing Chun: the forms, Chi Sao, Lat Sao, wooden dummy training, and weapon parts. These elements are the backbone of the system. At the same time, I am convinced that martial arts must remain alive. This means that we can adapt the language we use to teach them to the people of today – without watering down the essence.

Especially with children and young people, I therefore work with clear programs, well-structured levels, and understandable images. I explain principles in such a way that they become comprehensible in everyday life: balance not only as a physical center, but also as an emotional center; respect not only as a rule in training, but as a basic attitude in life. This keeps the bridge between traditional martial arts and the modern world stable.

The longer I teach Wing Chun, the less I see it as just a system of self-defense. Yes, the techniques work, yes, they can protect you in an emergency. But for me, the deeper meaning lies in personal development.

A student who trains for years changes. They become more upright—not only physically, but also internally. They learn to fall down and get back up again, to accept resistance without becoming hard, and to take responsibility for their own actions. They develop perseverance, learn to deal with frustration, appreciate small steps forward, and think long-term.

In a society where so much is geared towards quick results, Wing Chun stands for the opposite: for the long road, for slow growth, for the value of patience and perseverance. That makes the art challenging – and that is precisely what makes it so valuable.

When I am asked why Wing Chun is still “modern” in our time, I often answer: Precisely because our times are so turbulent, we need something calm. Precisely because so much is loud and spectacular, we need something simple and genuine. Precisely because many people lose themselves in the outside world, we need a path that leads us back to ourselves.

Wing Chun offers exactly that: a clear, direct path on which we can get to know ourselves better – physically, mentally, and emotionally. It teaches us not to respond to complexity with even more complexity, but with clarity. It reminds us that true strength has nothing to do with hardness, but with inner stability. And it shows us that simplicity is not a deficiency, but a sign of maturity.

As a private master student of Grand Master Samuel Kwok, I consider it a great privilege and at the same time a responsibility to pass on this art in all its depth. Every lesson, every hour with my students is also a reminder for me to remain a student myself – open, willing to learn and alert. Wing Chun is not a chapter that you finish at some point. It is a path that one walks.

In this sense, I understand the art of simplicity not as something that one achieves once and then possesses, but as an attitude that one adopts again and again. In training, in class, in everyday life. And that is precisely why I am convinced: Wing Chun was never just a martial art –and today it is more relevant than ever.

Sifu Markus Schinhammer is a private Wing Chun master student of Grand Master Samuel Kwok, Champion of Hong Kong (2017) and recognized teacher of the Ving Tsun Athletic Association in Hong Kong. He runs several Wing Chun schools in Munich with over 1,000 students and combines traditional martial arts with modern pedagogy and an authentic philosophy of life.

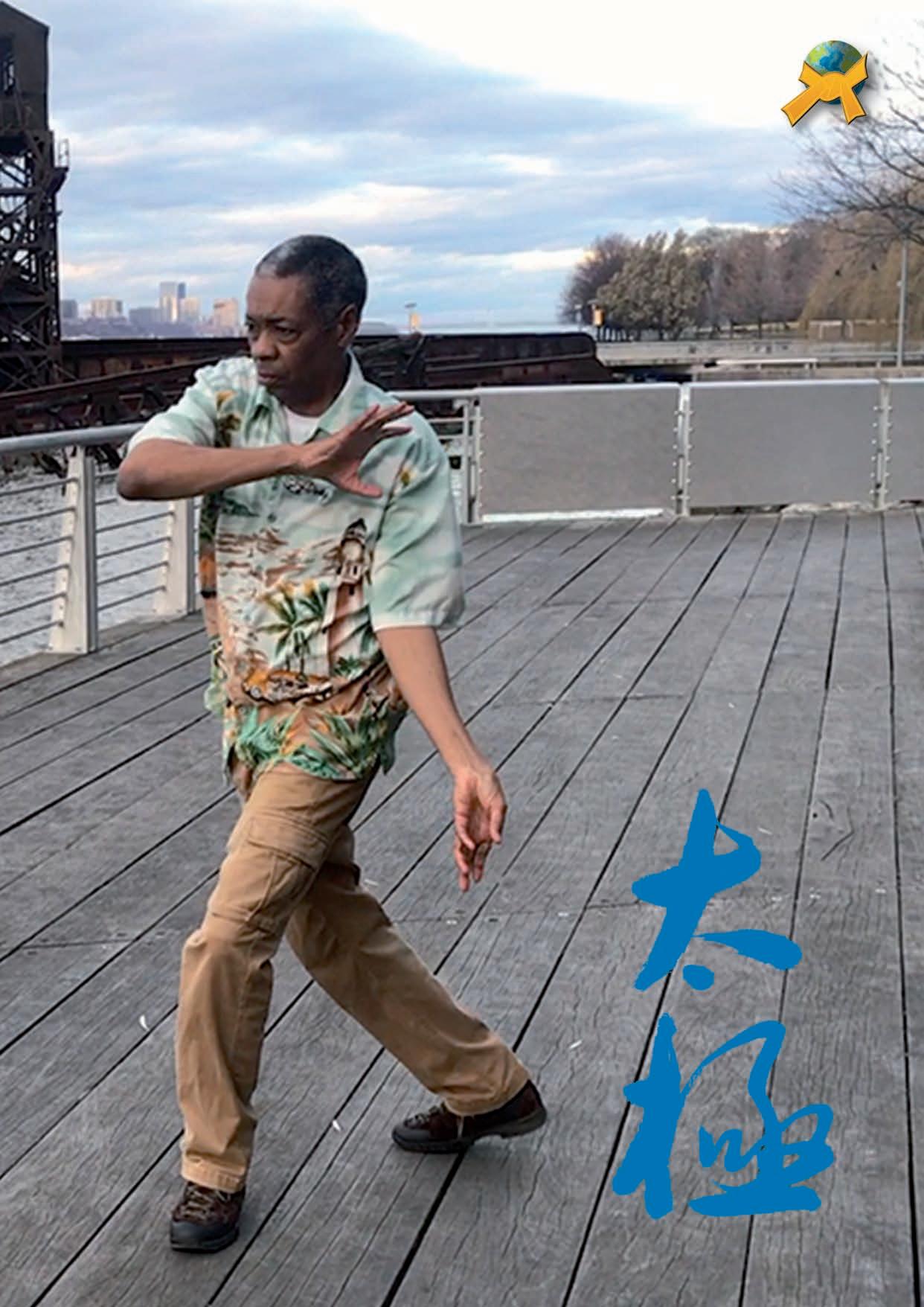

Like many of today's masters, I started as a child in the 1960s with judo. In addition to Japanese wrestling, I learned, with a certain pride, to pronounce numbers in Japanese, the names of techniques, and how to score points. The language, clothing, and ways of greeting during practice were those of the Far East. The Japanese had seen it right: after the defeat suffered during World War II, they tried to recover, not only in the eyes of the Emperor's subjects but also in front of the whole world. Their redemption came through the spread of their martial arts, which paved the way for Japanese culture, followed by economic competitiveness. Judo served as a “bridgehead,” followed by karate, then aikido, and countless other disciplines belonging to budo: from kendo to iaido, from ju jitsu to kyudo. But it was not just a panoramic view of the martial arts; knowledge, albeit superficial, extended to the life and code of the Samurai (an example of the supreme warrior), Zen, Buddhism, Shintoism, and Taoism. Physical practices were not neglected either. People read and, if possible, underwent Shiatsu, Kuatsu, and acupuncture treatments. The word KI was on everyone's lips, the energy that pervades everything and whose mastery confers extraordinary powers. The Japanese influence even reached the dinner table. In Italy, home to a varied and excellent cuisine, restaurants opened where you could enjoy raw fish, sushi, and sashimi. Next, The Book of Five Rings, by the 17th-century Japanese swordsman, together with the Hagakure code, tickled the minds of many trainers, bringing the strategy of the Land of the Rising Sun into companies as an example of perfect leadership or negotiation. Japan was the first, followed by a giant called CHINA with its kung fu, divided into a myriad of styles. The West learned about the legendary monasteries of Shaolin and Wu Dang, the former Buddhist and the latter Taoist. The slow-moving gymnastics called Tai Chi also arrived from the Far East, which the vast majority of Western practitioners later discovered to be a martial art. People became aware of vital points, which seemed to give extraordinary power to the expert who knew how to locate and strike them. Chinese strategic philosophy, with texts such as the TAO TE CHING, the 36 Stratagems, and Sun Tzu's The Art of War, was also translated and found its way into the libraries of many practitioners of Eastern disciplines. The more daring then began to study the language, customs, and traditions, such as the tea ceremony, pottery repair, and more.

As I grew up, I developed, as did many of my friends who practiced Eastern disciplines, albeit different ones, the idea that a wave of physical skills, war strategies, fascinating philosophies, and sublime arts were coming from the East, turning simple habits such as drinking tea or observing peach blossoms into activities of sublime meditation.

How unfortunate to be born in the West!

Here we only have technology and boring school subjects, I thought.

No martial arts.

No profound philosophies of life.

No practices for improving the inner self.

About 44 years ago, I realized that I was wrong, and so were many of my friends who practiced and professed Eastern arts and disciplines.

The West has its own wonderful martial arts, a sublime practical philosophy, and unparalleled artistic development.

We had this right before our eyes, but we didn't see it.

They say that to hide something, you have to highlight it.

A few kilometers from where I was born lies the city of Crotone in northern Calabria, a region in southern Italy. At the time when these areas were called Magna Graecia, one of the most important schools ever created by humanity was founded in that city: the Pythagorean school.

Yes, that very person about whom we know nothing except for the school obligation to prove his famous theorem. Most of the time, the rest of his life is neglected or underestimated and even knowingly belittled. This is not the case for the initiated. Those who keep the flame of tradition alive and who have been able to preserve ancient knowledge by resisting centuries of pressure from the dominant political and religious powers. Powers that saw the initiatory tradition as a real threat to political dominance because it deeply undermined philosophical and cultural beliefs. The smear campaign was constant, heavy, and bloody, but fortunately, the ancient knowledge was hidden and protected at the cost of life. A mere accusation of heresy was enough to end up at the stake. The example of Giordano Bruno is sufficient to understand the climate of the time. In addition to its well-known political implications, the witch hunt was a means of eliminating “competition” without too many problems.

Let's go back to Pythagoras. What is Pythagoras doing in a magazine about martial arts and Eastern culture?

If you have asked yourself this question, it is because you lack knowledge of what the Pythagorean school really was, its aims, and its practices.

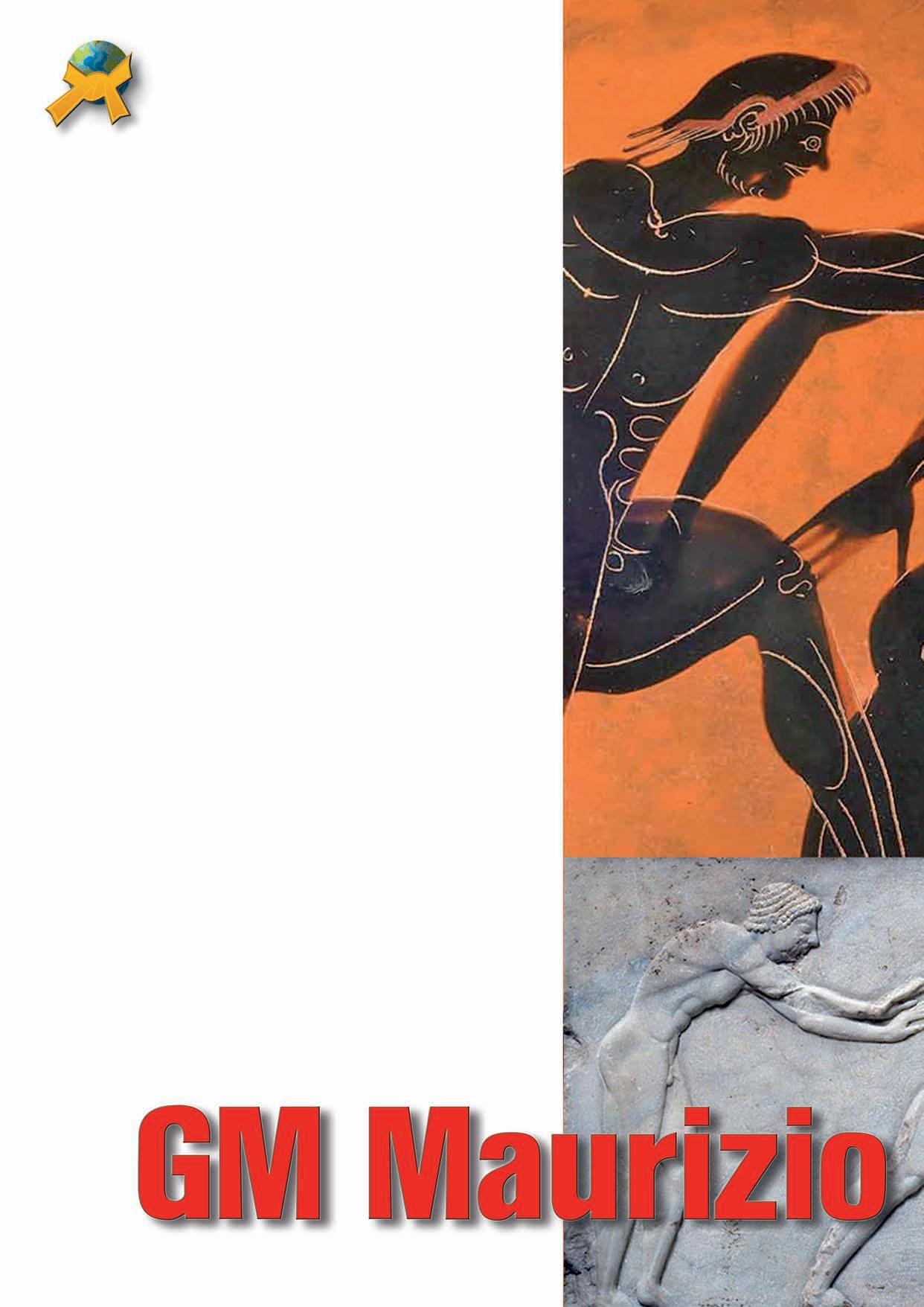

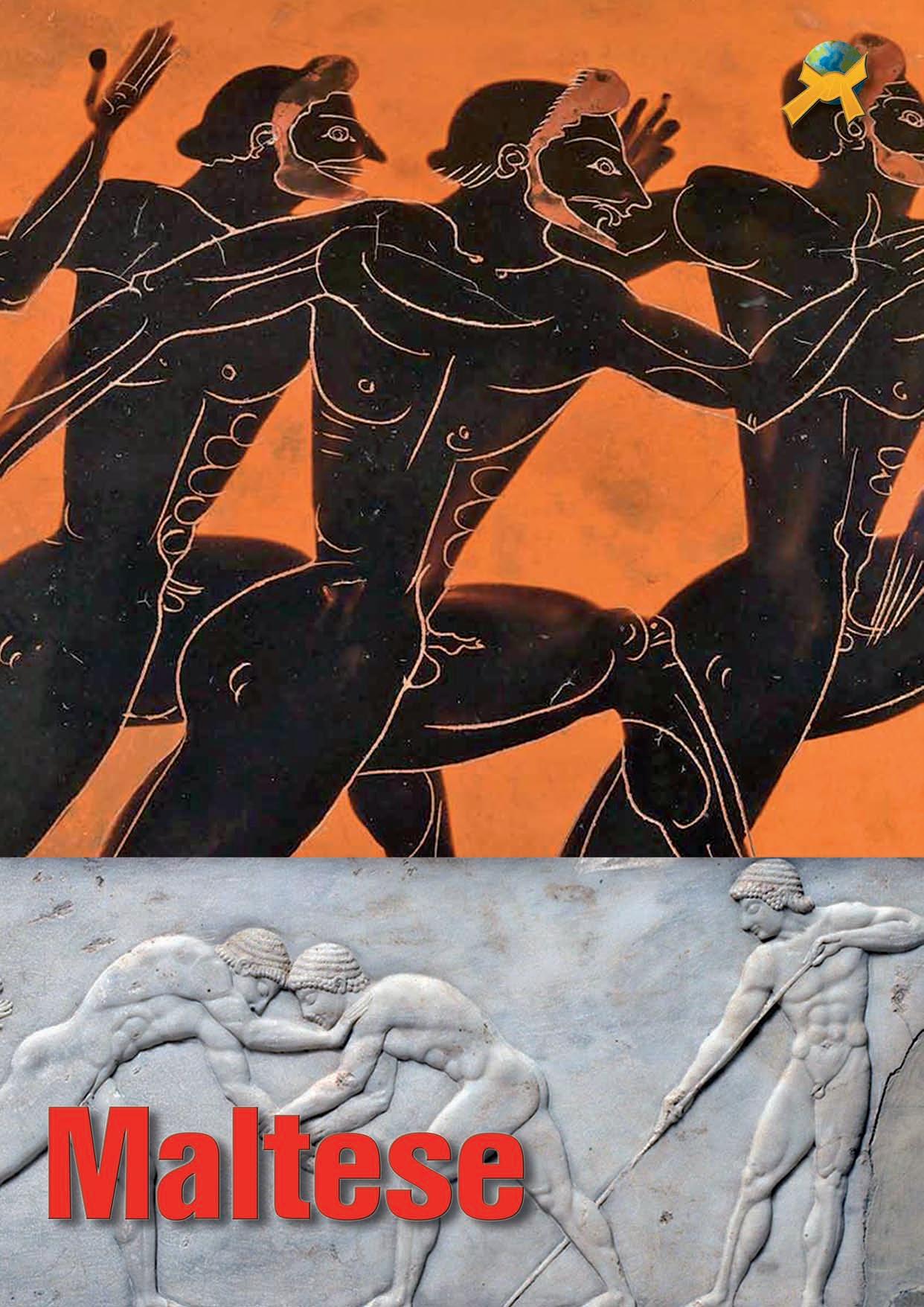

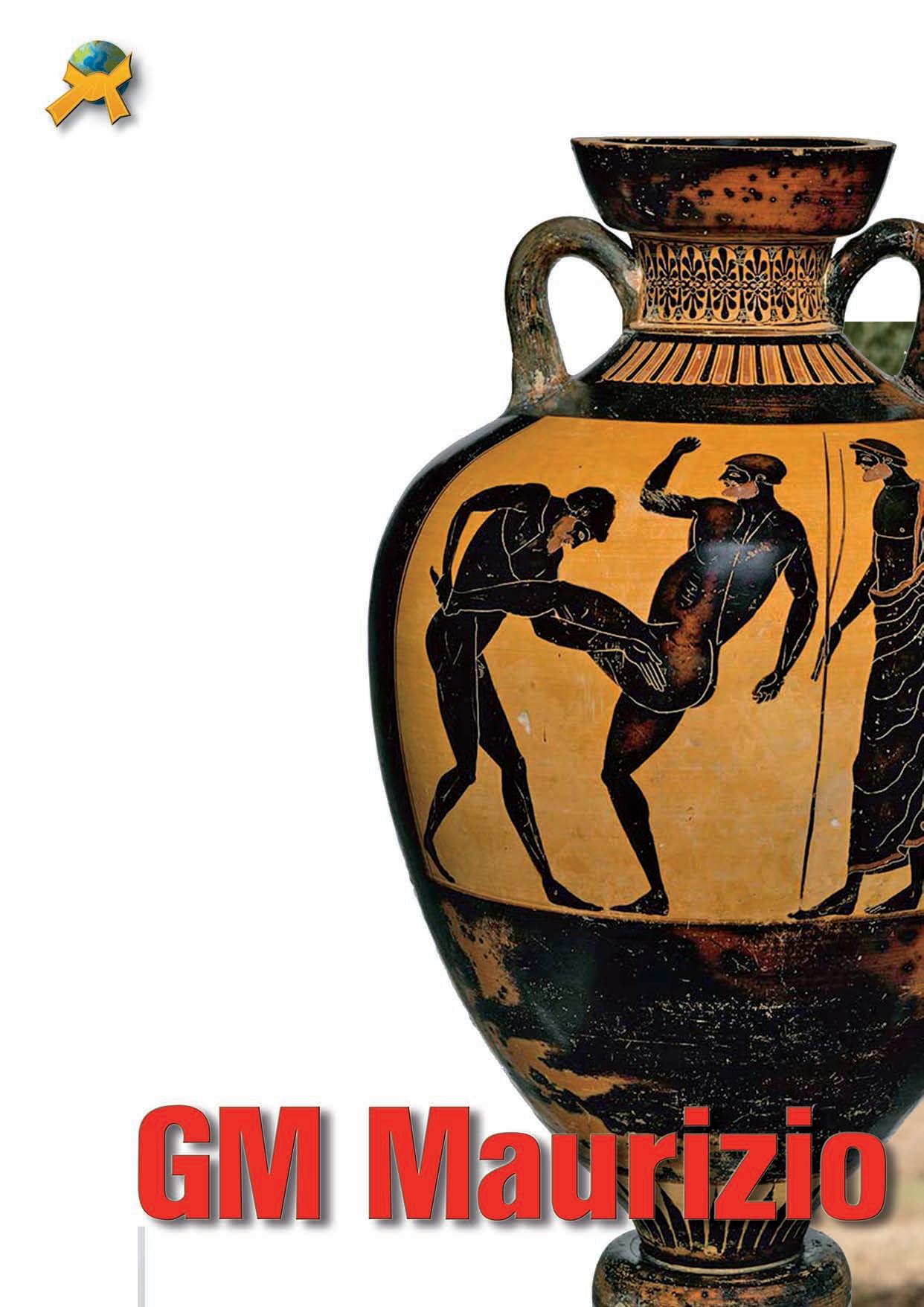

Let's start by saying that Pythagoras was a boxer and also a prestigious trainer of excellent boxers. Let's add that his son-in-law was none other than the legendary MILON, the undefeated wrestler, winner of numerous Olympic editions, who retired with the title of champion.

Why be surprised?

Haven't we always been taught that the Greeks (we are in Magna Graecia) held physical activity and intellectual activity in equal high regard?

So it is easy to deduce that many of the philosophers we have studied, or heard of, were excellent athletes and even experts in weapons and hand-to-hand combat. We must realize that we are victims of a general belief that today considers it normal for athletes to be intellectually deficient and intellectuals to be physically handicapped.

This has never been the case.

Many books have been written about Pythagoras, aimed mainly at a small circle of researchers. Information about ancient civilizations is not always certain and is sometimes contradictory. However, by referring to a modern-day Pythagorean, we can learn a lot about Pythagoras' initiatory school. I am referring to Vincenzo Capperelli.

The scholar was born in 1878 in Cosenza, moved to Catanzaro to attend middle school, and then went to Rome to graduate in medicine. He was a medical officer during the world wars and then, having returned permanently to Rome, he specialized in dentistry. He died in Rome in 1958. Throughout his life, he studied Pythagoras early in the morning, delving into the secrets of his school, which we will now not only examine but also compare with the well-known Eastern schools mentioned above.

The Pythagorean ‘dojo’ was founded, as we have said, in Crotone in southern Italy. Itwas not easy to enter this school, which was more like a monastery.

Admission was considered a very serious matter to which very few of the many who applied could gain access. First of all, the selection process was very tough, and the information gathered about the person concerned all aspects of their private life, including their family, inclination to study, behavior, habits, speech, and emotional management.

Physical appearance, gestures, and facial features were also examined (anticipating physiognomy). If you passed this first selection, you were admitted to the school and, for three years, you were on probation. During these three years, the novice was almost despised, subjected, if not to insults, to total indifference on the part of everyone else. This tested their determination and detachment from honors and recognition. After three years, if they were accepted, they moved on to the echemuthia, a phase lasting from two to five years. This was a period of silence during which they had to listen to lessons without being able to ask any questions. The teacher spoke from behind a curtain that hid him from the audience (perhaps reminiscent of the Eleusinian mysteries, a secret Athenian religious practice). Material goods were shared, and the adepts were subjected to physical trials that bordered on cruelty. The novice who completed the echemuthia (2 or 5 years) rose to the next level. Upon leaving the novitiate, one was no longer exoteric or external but became part of the esoteric or internal circle. The first degree of the new level was mathematics, a field in which sister disciplines such as arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy were studied. Then there was physics, in which the phenomena of nature were studied, and also the most arcane of the Pythagorean fields: arithmology. Physiology, medicine, and psychology were also studied, to the extent that every Pythagorean was also considered a physician. The goal of the Pythagoreans was to train a PANOURGO, that is, a person capable of dealing with everything in life. This is the exact opposite of what we do today with super-specialization. For Pythagoras, all human faculties had to be developed to the fullest.

“The Pythagorean ‘dojo’ was founded, as we have said, in Crotone in southern Italy. It was not easy to enter this school, which resembled a monastery. Admission was considered a very serious matter, and very few of the many who applied were granted access.”

As soon as they got out of bed, the adepts had to remember everything they had learned the previous day. They were often helped to wake up by singing and the sound of the lyre. In the evening, they also had to do what they called ‘examination of conscience’, reviewing the events of the day, and again, appropriate music was played, capable of influencing the mind according to a science that has now been lost. In the morning, physical exercises were followed by massages with oils. Running, wrestling, boxing, and shot put were daily activities. So was dancing, to which they attached great importance. It gave grace, elasticity, and eurhythmics to the body as well as helping to invigorate it. This was followed by a light first meal. The afternoon was devoted to politics and the development of what we would today call management skills. In the evening, small groups would go for walks with the aim of repeating what they had learned, reinforced by exchanges with other students.

They bathed in cold water, followed by the evening meal. Dinner was always eaten before sunset and always at a common table with no more than ten people (everything had a deep and hidden meaning). After dinner, there were instructive readings. The development of memory was held in high regard. The ‘media res’ or middle way was pursued: never any excesses, in any physical or mental activity. Women were held in high regard and were educated on an equal footing with men.

The aim was to build what the philosopher Nietzsche would later call the superman, a figure who in the school of Croton was known as the Pythagorean man.

The Pythagoreans recognized each other by a handshake (as members of Masonic lodges do today). Their characteristic sign was the pentalpha (also called the pentagram), or the five-pointed star drawn with a single stroke.

"They bathed in cold water and then had their evening meal. Dinner was always eaten before sunset and always at a common table with no more than ten people.“

“Running, wrestling, boxing, and shot put were daily activities. So was dancing, to which they attached great importance. It gave grace, elasticity, and eurhythmics to the body as well as helping to invigorate it”

As in the Eastern cultures we refer to when we talk about samurai or Chinese social organizations, the Pythagoreans were also strongly anti-democratic because they believed that only educated and trained people could govern. This absolute intransigence generated discontent among the people as the government slowly moved towards dictatorship. The people, who did not have the psychophysical training of the adepts, could not bear and did not understand the constraints imposed on them by these members of the government.

Political opponents fanned the flames of discontent and ended up leading a revolt that overthrew the government of the enlightened.

In conclusion, Pythagoras was the cornerstone of Western culture, but it cannot be denied that his school was influenced by Eastern culture. Indeed, once again, this obsession of intellectuals with dividing humanity into categories does not always match the human habit, especially that of researchers, but also of warriors, of traveling the world and learning and teaching by mixing knowledge that is no longer easily classifiable.

It seems that Pythagoras had the opportunity to learn from everyone, arriving at a synthesis that culminated and crystallized in his school in Crotone, laying the foundations for human development in Italy. The Pythagoreans were convinced that one had to work on oneself relentlessly. No knowledge was excluded, as this was the only way to evolve immediately, even in earthly life.

The similarities with the schools of human perfection in the Far East are striking. Modern man, watching films about Eastern warrior monks from the comfort of his sofa, is unaware that schools similar to those in the East existed very close to him. The Pythagorean school was impressively comprehensive, focusing on the development of both mind and body. Pythagorean adepts were warriors, doctors, scientists, politicians, administrators, and even excellent teachers capable of guiding others in the practice of exercises aimed at self-knowledge.

Perhaps the time has come to reveal what has been hidden from us for centuries.

”The Pythagorean school was impressively comprehensive, focusing on the development of both mind and body. Pythagorean adepts were warriors, doctors, scientists, politicians, administrators, and even excellent teachers capable of guiding others in the practice of exercises aimed at self-knowledge."

True Jutsu

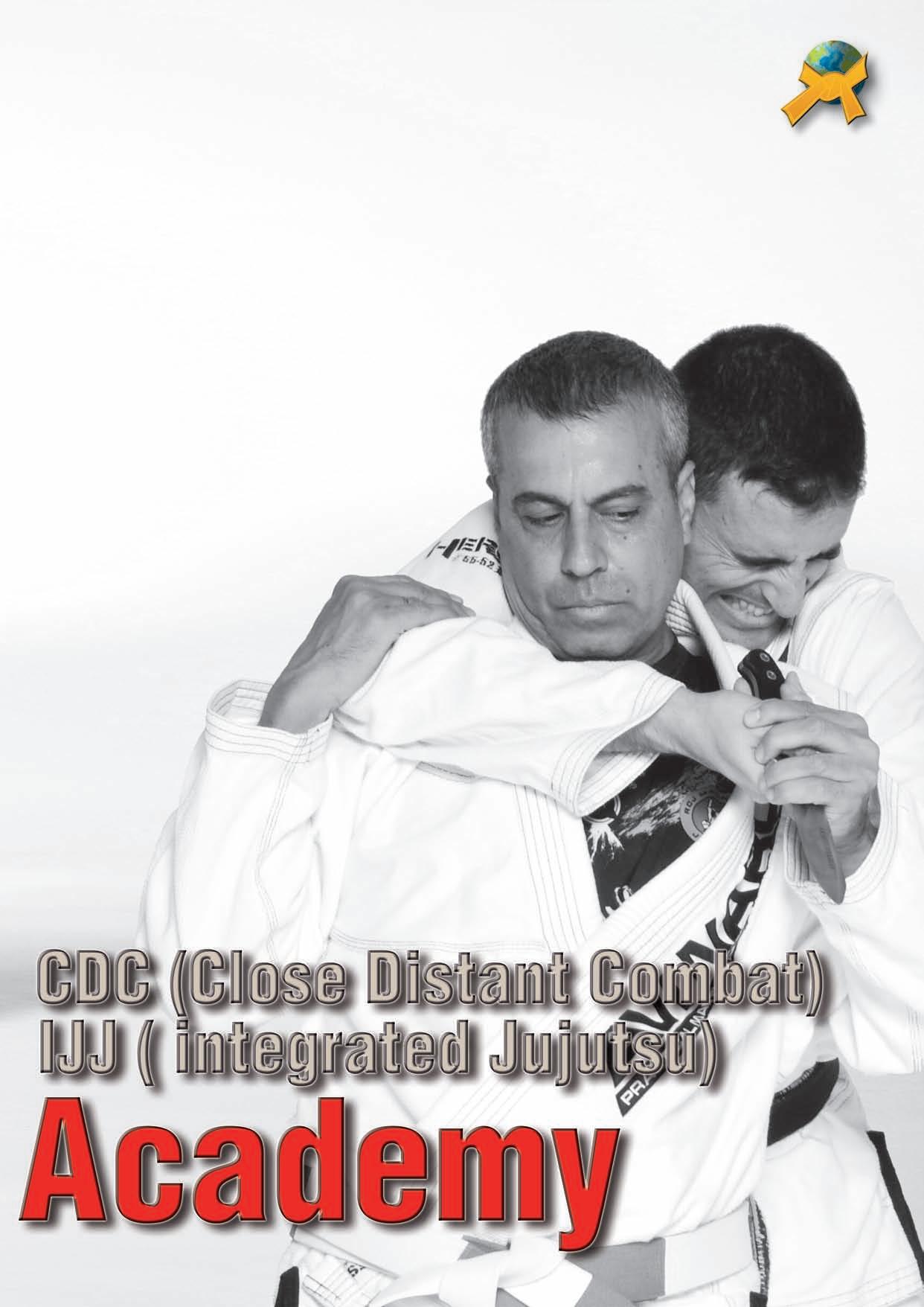

Martial arts and integrity seem to be fading as society moves deeper into the digital era. A new generation believes self defense can be learned like an app, while true teachers become fewer each year. In their place, self appointed instructors appear, supported by business driven organizations and federations willing to hand out ranks, titles, and certificates to anyone who can pay. In Israeli martial arts such as Kapap and Krav Maga, this issue has become especially severe. Every day I receive messages from people who want to buy ranks they have not earned, or who boldly grant such ranks to themselves without shame. No one asks who their teachers were or what lineage they came from. We are losing the True Jutsu—not only in martial arts, but in every walk of life.

In my 64 years, my parents and my generation taught me honesty and integrity. They made mistakes, and so did I, but I learned that truth is often hidden and must be discovered through hardship. Still, I chose to follow my own path. This is the Do of martial arts—the same spirit found in Judo and Karate-Do— and it is one of the reasons I stopped teaching Israeli martial arts.

Over the years, I have stayed with all kinds of wealthy people—billionaires with cars worth more than government budgets, homes with more rooms than residents, yachts and pools that change color, and even dogs with full time nannies. Lying in bedsheets that cost more than my car, I realized something: they all share a secret. None of them say it aloud. It is not written in books or taught in universities. But every one of them lives by it.

If you said this secret on the street, people would think you were crazy. But if you heard it from a billionaire sitting on his balcony, sipping desalinated water at a carefully chosen “spiritual” temperature, it would suddenly make perfect sense.

This secret is the truth about life—a truth the wealthy know but never share. They do not write it, whisper it, or preach it. Yet it silently fuels their success. Here is that truth, the True Jutsu of life:

When

People do not value what comes for free. Anything given away without cost becomes invisible. If you give your time, your attention, and your energy freely to everyone, people will treat your presence like background noise. They forget anything that required no effort from them. People rarely understand value—they understand price. Respect begins the moment you stop giving yourself away.

Eastern masters say patience leads to peace. In some countries, patience only leads to someone cutting in front of you and saying, “I just asked something.” A monk may sit twelve hours listening to a waterfall, but anyone who waits twelve hours for a plumber who keeps saying “I’m on my way” achieves a higher level of spiritual enlightenment. The universe calls it “enlightenment.” We call it “breaking quietly inside.”

It is true that money cannot buy happiness. But it can buy a plane ticket to Greece, where you can argue with your problems on a turquoise beach instead of on a crowded bus. It can buy space, peace, and a bed that doesn’t collapse when you turn over. Happiness isn’t sold in stores, but misery doesn’t have to ride the bus either. Money cannot solve everything, but it cushions almost everything.

People who claim they are “simple” often leave IKEA with a bill that looks like a national budget. They love a “simple life,” as long as it includes a 50 euro coffee and a playlist curated by a tortured vegan artist. Somehow, their minimalism always costs more than they expect. They say they need very little—except for everything in the store.

The world does not reward honesty; it rewards strategy. The world is not a temple—it is a battlefield. Honest people are often used, not respected. They apologize for existing while others take what they want without hesitation. The world knows exactly who will not fight back, and it shows them no mercy. Truth is a knife without a handle—if you do not know how to hold it, you will be the one who bleeds. Honesty is a luxury only the strong can afford.

Some people dress simply, yet their “simple” wardrobe costs three months’ salary. They claim not to spoil themselves, but somehow they end up at a three hour spa using creams supposedly made from unicorn tears. They sincerely believe they are simple—and that is the most extravagant illusion of all.

Money does not change people; it unmasks them. Poverty hides flaws beneath necessity and humility. When resources appear, the true person emerges. The one who is empty becomes a loud, insecure king. The one with strength and character gains the ability to lead without breaking. Wealth magnifies what is already inside. It does not corrupt—it exposes.

True Jutsu is not about fighting techniques. It is about clarity. It is about recognizing value, setting boundaries, seeing through illusions, and understanding how the world truly works. Martial arts once taught this naturally—discipline, honesty, lineage, and responsibility. Today, as false masters and easy certificates spread, remembering the deeper lesson is more important than ever: power comes from truth, but only if you know how to carry it.

When I was young, I never understood Kyokushin.

Kyokushin means “ultimate truth” or “the way of the ultimate truth.” The name comes from the Japanese words “Kyoku” (extreme) and “Shin” (truth).

The Japanese phrase for “ultimate truth” is 究極の真実 (kyūkyoku no shinjitsu). It can also be expressed as 極真 (kyokushin), the name of a martial art that literally means “ultimate truth.”

In martial arts such as Thai Boxing, Kickboxing, Judo, BJJ, and Sambo, the truth can be seen on the mat. But in many martial arts with no sparring or contact, people can demonstrate “magic” techniques that work only when no one resists. Without resistance, everyone looks like they can fight.

By Kahlil Gibran

Your joy is your sorrow unmasked. And the self same well from which your laughter rises was often times filled with your tears. And how else can it be?

The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain. Is not the cup that holds your wine the very cup that was burned in the potter’s oven?

And is not the lute that soothes your spirit, the very wood that was hollowed with knives? When you are joyous, look deep into your heart and you shall find it is only that which has given you sorrow that is giving you joy. When you are sorrowful look again in your heart, and you shall see that in truth you are weeping for that which has been your delight.

Some of you say, “Joy is greater than sorrow,” and others say, “Nay, sorrow is the greater.”

But I say unto you, they are inseparable. Together they come, and when one sits alone with you at your board, remember that the other is asleep upon your bed.

Verily you are suspended like scales between your sorrow and your joy. Only when you are empty are you at standstill and balanced. When the treasure-keeper lifts you to weigh his gold and his silver, needs must your joy or your sorrow rise or fall.

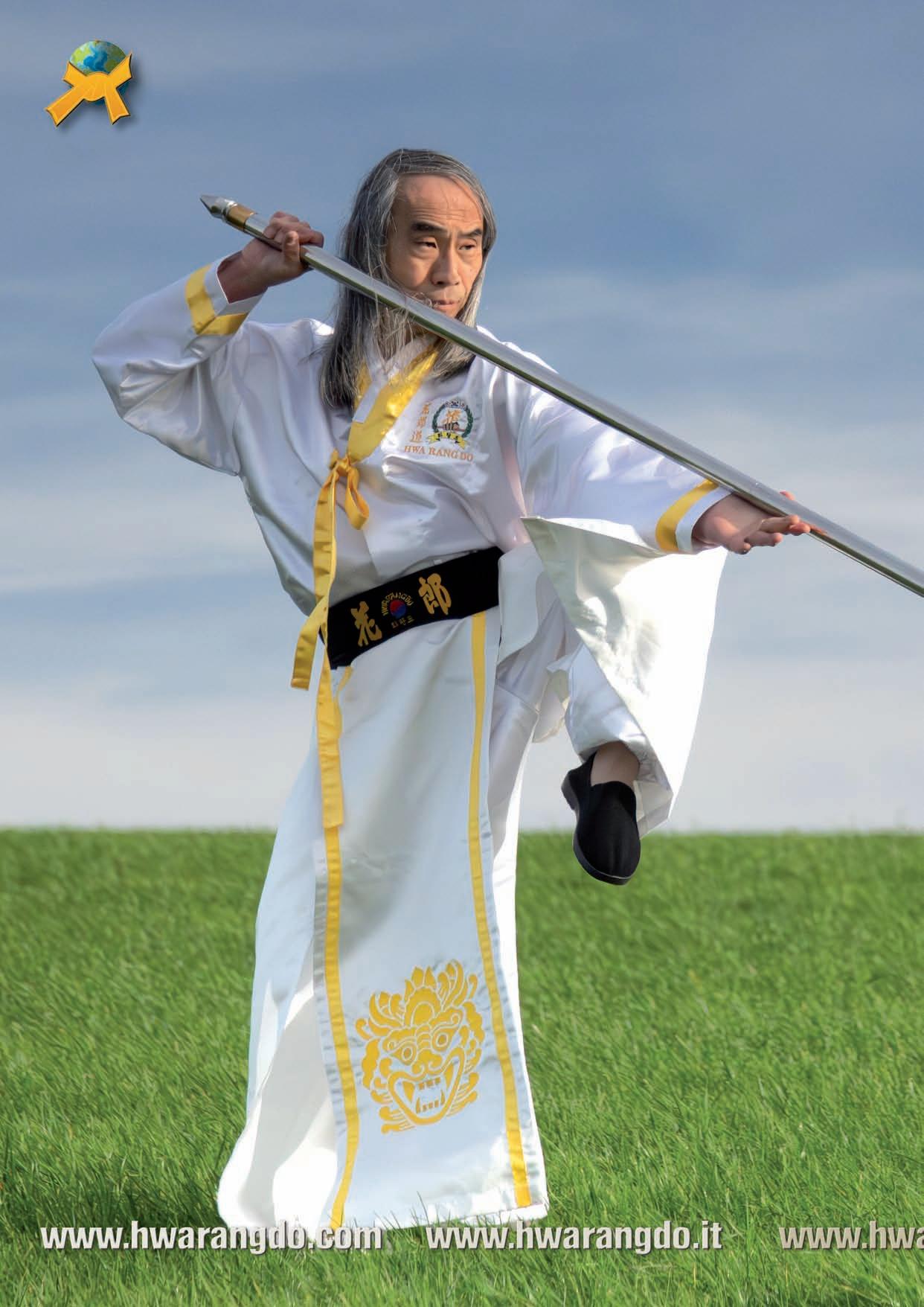

Human beings are naturally drawn toward pleasure and repelled by pain. From childhood, both by nature and conditioning, we learn to pursue what feels good and avoid what feels painful. We chase accomplishments, recognition, comfort, and the fleeting highs of life, while we recoil from difficulty, failure, loss, and discomfort. Yet, this instinctive behavior overlooks one of life’s deepest truths: joy and sorrow are intimately connected, like two sides of the same coin. As Gibran eloquently states, “the same well from which laughter rises was oftentimes filled with tears.” Laughter and tears share the same source—they are different expressions of the same human depth. This principle is foundational to the philosophy of Hwa Rang Do®. Martial arts are often taught as a path of physical mastery—punch, kick, throw, or block—but at its core, Hwa Rang Do trains the whole human being: body, mind, and heart. Every emotion, every experience, is interconnected. Mastery is not achieved by avoiding pain or refusing to confront hardship; it is achieved by recognizing and embracing the interplay of joy and sorrow. A practitioner who shies away from difficulty cannot cultivate true resilience, just as a person who avoids sorrow cannot fully experience the richness of happiness.

The metaphor of the potter’s kiln illustrates this beautifully. A wine cup does not emerge complete without having endured the fire, without having been shaped, hardened, and tested. Likewise, a lute—the instrument that creates melody and harmony—owes its voice to the careful carving of the wood, a process that involves removal, shaping, cutting, chiseling, drilling, and vulnerability. In both cases, beauty and utility emerge not despite the shaping process, but because of it. Likewise, human joy emerges in the space created by challenge, loss, and sorrow.

In the life of a martial artist, this principle is made tangible. Every bruise, every failed technique, every correction from a teacher, every reprimand, and every moment of frustration represents sorrow. These are not mere inconveniences—they are formative experiences that carve the vessel of the warrior’s skill and character. When the body finally executes a move flawlessly, when a technique flows naturally, and when the spirit rises with accomplishment, the joy that fills the practitioner is profound precisely because it has been earned through struggle. That joy is richer, deeper, and more sustaining than any fleeting pleasure because it is inseparable from the experience that preceded it.

Moreover, this understanding cultivates humility and patience. The warrior recognizes that mastery is not instantaneous. Joy does not appear without effort, and success is not devoid of sacrifice. Each challenge, each moment of difficulty, contributes to the refinement of skill and character. To embrace sorrow is not to invite suffering for its own sake, but to acknowledge its formative role in shaping the soul and the body.

This interplay also fosters empathy and wisdom. A warrior who has felt sorrow—who has faced failure, endured pain, or navigated personal struggle—is equipped to understand the challenges of others. This capacity for compassion is as important as physical skill, for it transforms a fighter into a guide, a teacher, and a leader. The mastery of Hwa Rang Do is, therefore, not only technical but deeply human: it is the ability to harmonize experience, transform adversity into growth, and cultivate a heart capable of both resilience and joy.

Ultimately, this principle teaches that joy is never free, and sorrow is never meaningless. Each moment of bliss is the fruit of prior effort, endurance, and reflection. Each difficulty is an invitation to expand capacity, to refine skill, and to deepen awareness. The martial path, therefore, is a mirror for life itself: the more the warrior learns to honor and integrate both joy and sorrow, the greater their mastery—not just of technique, but of self.

Many students experience joy as a fleeting rush of exhilaration without pausing to examine its origin or meaning. In martial arts, this often appears when a beginner, a white belt, finally executes a technique correctly or wins a sparring match. The moment is electric—a sudden surge of pride and excitement—but without mindful reflection, this joy can subtly seed the ego. The student may begin to measure themselves by accomplishments rather than by growth, attach their sense of self-worth to external validation, or develop a fear of failure, all of which undermine long-term development.

A mature warrior recognizes that joy is rarely spontaneous; it is born of struggle, effort, and persistence. Every mastered technique reflects countless repetitions, failed attempts, physical strain, corrections from instructors, and the quiet endurance of self-doubt. Joy is not an endpoint but the byproduct of a process—a mirror of the effort invested and the lessons absorbed. In this sense, the celebration of success without acknowledgment of its roots is incomplete and potentially misleading.

In Hwa Rang Do, progression is symbolized by belts and ranks, yet these markers are not merely rewards—they are signposts reminding the practitioner that mastery is continuous. The white belt who lands a technique today should understand that the lesson of that accomplishment is not that they have “arrived,” but that they have built a new foundation from which to continue growing. Yesterday’s ceiling becomes today’s floor, and the process of learning, correcting, and refining is ongoing. Joy arises fully only when we recognize and honor this context.

Reflection transforms joy into wisdom. When students trace their victories back to their efforts, failures, guidance, and support, joy becomes deeply rooted. It cultivates gratitude for mentors who challenged them, peers who pushed them, and even rivals who forced them to improve. It nurtures humility, reminding the practitioner that no accomplishment exists in isolation. This awareness strengthens the character as much as the body and mind, creating a joy that is sustainable rather than ephemeral.

Conversely, unexamined joy carries risks. Pride inflates the self, fostering arrogance and complacency. Attachment ties one’s identity to outcomes, so that future failures feel catastrophic. Lack of reflection blinds the student to the lessons hidden in struggle and the contributions of others, leaving them isolated in their perception of achievement. Over time, these habits can stunt growth and distort understanding.

By cultivating examined joy, a student learns to celebrate without attachment, appreciate accomplishments without arrogance, and use pleasure as fuel for further development. This practice transforms joy from a temporary emotion into a tool for growth, strengthening not only technique and performance but also character and perspective. True mastery, therefore, is inseparable from awareness: it is the ability to embrace the sweetness of success while remaining grounded in humility, gratitude, and a clear understanding of the path that led there.

While joy is celebrated and often sought after, sorrow is frequently feared or avoided. Many students instinctively recoil from difficulty, failure, or pain, seeing them as threats rather than opportunities. In the context of martial arts, this might appear as a student avoiding challenging techniques, shying away from sparring, or becoming discouraged after repeated mistakes. Yet, sorrow is not a sign of weakness—it is one of the greatest teachers a warrior will ever have. It forges resilience, nurtures compassion, and illuminates insights that comfort and pleasure alone cannot provide.

Sorrow is unavoidable in life. Physical injuries, losses, setbacks, and disappointments will come to every practitioner, just as they come to every human being. The same principle applies in the training hall: every failed technique, every correction, every loss in sparring carries the sting of disappointment. But it is precisely through these moments that a student is presented with opportunities to develop strength, awareness, and perseverance. Avoiding sorrow or masking it with superficial victories only delays growth; it leaves the practitioner emotionally underdeveloped, incapable of fully responding to life’s inevitable challenges.

A deeper truth is that sorrow often carries hidden joy within it. Consider the initial sting of failure: a student may feel embarrassment, frustration, sadness, and/or disappointment. But beneath this surface, there is meaning. The sorrow reflects the value of what was attempted: the love of learning, the desire to excel, the appreciation of the teacher’s guidance, or the significance of the relationships and experiences that created the moment. Sorrow is the shadow of love; it marks what we hold dear. Without sorrow, joy would be shallow and fleeting, for it is the contrast that gives pleasure its depth.

The mature warrior asks a crucial question: “What is this sorrow teaching me?” Not merely to endure, but to observe, integrate, and grow. Each setback becomes a mirror, reflecting where skill, patience, or understanding needs refinement. Emotional mastery is developed not by suppressing pain but by facing it directly with courage, awareness, and reflection. In the dojang, this might look like accepting a loss in sparring without defensiveness, analyzing the mistakes made, adjusting strategies, and returning to practice with renewed determination. Over time, these experiences teach adaptability, self-discipline, and humility—qualities far more enduring than any trophy or medal.

A heart that avoids sorrow becomes callous, rigid, and incapable of true empathy. By contrast, a heart that embraces sorrow—acknowledging the pain, understanding its origins, and learning from it—develops strength, humility, and compassion. These qualities extend far beyond martial practice: they shape how a person interacts with family, friends, colleagues, and even strangers. Only those who have faced their own suffering can truly empathize with the struggles of others, lead with integrity, or guide students in ways that resonate on both technical and human levels.

Sorrow, therefore, is not the enemy of the warrior; it is an essential partner in the path of mastery. It sharpens the mind, strengthens the heart, and deepens understanding. When integrated consciously, sorrow becomes a source of wisdom, a teacher whose lessons endure long after the pain has passed. In this light, every failure, every setback, and every challenge is not merely an obstacle to be endured but a steppingstone toward a more complete, capable, and compassionate self.

Humans are naturally drawn to categorize experience. From early childhood, we instinctively divide life into dualities: good versus bad, pleasure versus pain, success versus failure, joy versus sorrow. These distinctions help us navigate daily life, yet they are incomplete and potentially misleading. By privileging one side—seeking only pleasure, avoiding only pain—we risk creating imbalance in perception and response. We fail to grasp the deeper truth that life is an interwoven continuum, where contrasting experiences are not opposing forces but complementary threads of a single fabric.

Gibran reminds us that joy and sorrow are inseparable. They exist not as independent experiences but as reflections of the same human depth. A warrior who seeks only joy—clinging to success, accolades, or fleeting satisfaction—becomes fragile. When inevitable setbacks arrive, when failure strikes or the world tests their resolve, they are unprepared and vulnerable. Conversely, a warrior who identifies exclusively with sorrow—focusing on loss, hardship, or struggle—hardens over time, losing the capacity to fully experience happiness, gratitude, and love. In both cases, an incomplete engagement with life diminishes growth.

The philosophy of Hwa Rang Do emphasize integration and acceptance: joy arises not in spite of sorrow but because of it. Just as a cup is formed in fire before it can hold wine, sorrow shapes the vessel of the heart, preparing it to receive the depth and richness of joy. Victory and defeat, love and loss, praise and criticism—they are not separate entities but interconnected elements of the same rhythm. The mature practitioner recognizes that to embrace one fully, one must also accept the other. Emotional freedom arises when the warrior no longer chases joy alone or flees sorrow but rather moves fluidly within the totality of human experience. This is where it gets difficult…

This principle is mirrored directly in martial training. In the dojang, attacks are inseparable from defenses. A strike is only meaningful when paired with the awareness of countering threats; offense is defined by the presence of resistance. Strength is inseparable from flexibility; rigidity may appear powerful, but only adaptability ensures survival and efficacy. Physical technique is inseparable from mental awareness; without mindfulness, a perfectly executed move may fail under pressure. The same lesson holds for life itself: joy cannot exist without sorrow, and growth arises when both are integrated.

In practical terms, this means approaching training—and life—with a mindset of acceptance and balance. When a student fails in sparring, they do not merely endure the loss—they reflect on its meaning, recognize what it teaches, and carry the insight forward. When a student achieves a victory, they do not inflate their ego—they acknowledge the struggle and guidance that made it possible. Every experience, pleasant or painful, becomes part of a continuous learning process. By embracing the inseparability of joy and sorrow, the Hwa Rang Do practitioner cultivates resilience, emotional intelligence, and equanimity. Life becomes less a series of dualities to be fought or feared, and more a flowing continuum to be navigated with awareness, skill, and grace. The mature warrior, both in the dojang and in life, moves within this continuum confidently, integrating all experiences as teachers, and responding not with reactivity but with conscious, measured action.

Gibran’s metaphor of the scales captures the essence of emotional mastery:

“Verily you are suspended like scales between your sorrow and your joy. Only when you are empty are you at standstill and balanced.”

The world will test us. Praise, criticism, success, failure—they lift and lower the pans of our internal scales. The novice reacts, the intermediate resists, but the master stands at the fulcrum. The ability to remain centered amidst the shifting tides of life is the hallmark of the fully realized warrior.

Balance is not absence of movement—it is equilibrium amid motion. The Hwa Rang Do practitioner learns that every challenge, every moment of success or defeat, is an opportunity to cultivate this balance. By observing both joy and sorrow without attachment, the warrior develops freedom from emotional extremes, achieving clarity and steady purpose.

Emptiness is often misunderstood. To many, it might sound like a void, a lack of feeling, or even a detachment from life itself. But in the context of Hwa Rang Do and the path of the warrior, emptiness is the core of balance, the essential state that allows a person to engage with life fully while remaining centered. It is not numbness, nor is it avoidance of feeling. Rather, it is the capacity to receive life as it comes—joy, sorrow, triumph, and loss—without being controlled, defined, or destabilized by these experiences.

An empty heart and mind are like a cup ready to receive water. The cup has space; it is not clogged or rigid. Likewise, the mind that has cultivated emptiness is open, perceptive, and adaptable. It can respond fluidly to circumstances, discerning the proper course of action without obstruction from ego, fear, or attachment. This state enables the warrior to act decisively in moments of crisis, to respond rather than react, and to maintain clarity when emotions and events threaten to overwhelm.

In combat, this concept is captured by the principle of mushim (무심 / 無心), often translated as “no-mind.” The practitioner in mushim does not pause to calculate, second-guess, or hesitate. They respond instantly and accurately to the flow of the encounter, their body and mind functioning as one integrated instrument. Techniques are executed with precision, timing is instinctive, and reactions arise naturally from training rather than from conscious deliberation or emotional interference. The mind is not blank in the sense of being inert; it is fully present, fully aware, and completely free to act.

In life, emptiness manifests as emotional and spiritual clarity. Joy and sorrow, praise and criticism, gain and loss—all arise and pass, yet the center of the practitioner remains unmoved. They feel deeply, yet they are not carried away by emotion. They engage fully with people and experiences, yet they retain the freedom to observe, reflect, and act with discernment. This balance between engagement and detachment, feeling and clarity, is what allows the mature warrior to navigate the complexities of life with grace.

True emptiness is not given; it is earned. It emerges only after fully experiencing life in all its dimensions—confronting sorrow without fleeing, celebrating joy without clinging, facing fear without collapsing, and enduring challenges without surrender. Each experience shapes the mind and heart, carving space for presence, awareness, and centeredness. This is why the calm of the mature warrior is distinct—it cannot be imitated. It is the calm of someone who has lived deeply, suffered fully, loved profoundly, and grown through it all. It is a calm forged in fire, tempered in experience, and polished by reflection.

In Hwa Rang Do, cultivating emptiness is both a practical and spiritual practice. On the training floor, it is achieved through repetition, meditation, mindful observation, and disciplined reflection. In life, it requires conscious engagement with experiences, self-inquiry, and the courage to face both internal and external challenges. The empty mind and heart are not passive—they are alive, receptive, and capable of extraordinary insight and action.

Ultimately, emptiness is the foundation of mastery. Without it, skill becomes mechanical, emotion becomes erratic, and judgment becomes clouded. With it, a warrior moves through the world with clarity, balance, and a deep, unshakable presence. Joy is experienced fully because sorrow has been integrated; sorrow is endured gracefully because the heart is steady. Emptiness allows life itself to flow through the practitioner, and in that flow, true freedom and mastery are realized.

Up to this point, the path of the warrior has followed a clear progression. We train, refine, struggle, suffer, rise, fall, learn, and grow. Through discipline and experience, we carve out depth within ourselves. We become capable of holding joy and sorrow without being destroyed by either. This is the maturity earned through sweat, failure, heartbreak, and perseverance. Many believe that this is the end of the journey—that once we achieve inner balance, emotional clarity, and the emptiness of a steady heart, we have arrived at the peak.

But Gibran does not stop there.

Just when he has brought us to the height of personal mastery, he suddenly introduces a force beyond the warrior—the treasure-keeper. And with that single image, the tone shifts. Gibran reminds us that even the strongest warrior, the wisest monk, or the most disciplined seeker stands before a scale they do not control.

This is the point where many martial artists—after decades of training—encounter the greatest realization of all: Selfmastery is not the final destination. It is only the preparation for seeing our limits clearly.

The warrior becomes empty, balanced, reflective, and strong—only to discover that emptiness is not the end, but the doorway to something greater. When we look back over our striving, we begin to understand that all our effort, refinement, and growth have been preparing us for a truth we could never have seen in the beginning:

Strength alone is not enough.

Wisdom alone is not enough.

Balance alone is not enough.

For all our mastery, we still cannot control life’s scales.

And so, the poem moves—from human achievement to divine reckoning, from the work of the warrior to the mystery of God. This is where Part VII begins: with the humbling recognition that everything we have built, learned, and become must ultimately stand before the One who weighs all things.

Gibran’s final image—the treasure-keeper lifting the scales—often passes quickly over the heads of those who read the poem casually. But for anyone who has lived long enough, fought hard enough, or tried with all their strength to master themselves, this image stops us. It does not whisper—it confronts.

Here, the poem pivots. Up to this point, Gibran has spoken of the relationship between joy and sorrow, of the vessel and the contents, of the carving of pain and the capacity for happiness. But when the treasure-keeper enters, the entire meaning deepens. Suddenly we are forced to ask:

Who holds the scale of our lives?

Who weighs our efforts, our joys, our sorrows, our achievements, our failures?

It is not us.

Most martial artists begin their journey believing the opposite. We train hard because we believe that the right combination of inner strength, discipline, technique, and wisdom will allow us to take command of our lives—to be unaffected by circumstance, unshaken by misfortune, victorious over pain. And in many ways, this belief is necessary at the beginning. It fuels the grind. It drives practice. It creates the hunger to grow.

But eventually, life brings every warrior to the same realization: Self-mastery, though noble and essential, is not ultimate. It cannot secure us against the uncontrollable.

We may: Condition our bodies, develop sharp minds, discipline our emotions, accumulate skill and experience, becoming wise, calm, and formidable—but we are still human. We are still subject to the events of life. We are still vulnerable to the unexpected—and we always were.

Gibran is brutally honest about this truth. He is saying: “Your training can refine you, but it cannot make you God.”

Only the treasure-keeper—God, the Divine Judge, the Ultimate Authority—has the right and the power to lift the scale. And when that moment comes, all our gold and silver—our strength, our wisdom, our resilience, our accomplishments— are placed on the balance.

This is where the poem becomes uncomfortable, because it means: We never had control. We never owned the scale. That is a hard truth for warriors, because we are built to fight, to drive forward, to take responsibility, to stand and say, “I will not be defeated. I will never surrender!” But the deeper reality is that no amount of effort guarantees victory in life. No one escapes sorrow. No one escapes loss or suffering. No one has achieved enough mastery to exempt themselves from being human.

Many philosophies try to solve this problem by telling us: “Let go so you won’t suffer. Become emotionally neutral. Transcend feelings.”

But Gibran is saying the opposite.

He insists: We will feel joy fully, we will feel sorrow fully, and that is not weakness—it is the human condition.

To numb sorrow is to numb joy.

To silence grief is to diminish love.

To seek neutrality is to trade humanity for anesthesia.

The way out is not emotional control. It is spiritual surrender.

This is the turning point most disciplined people resist. We want to believe that if we train long enough, meditate deeply enough, think clearly enough, and analyze precisely enough, we can manage life with internal strength.

But eventually, life presents us with something that does not yield to skill: A loved one dies, a dream collapses, a relationship ends, a betrayal strikes, or the body begins to fail. In those moments, every technique, every insight, every ounce of discipline we have cultivated proves valuable—but limited. And it is precisely in that place that the warrior is forced to confront the truth: We are not the masters of existence. We are only participants in it.

This is where humility enters—not the false humility of pretending to be small, but the humility of recognizing: We did not create ourselves; we did not design the universe; we did not set the laws of life; we do not hold the scale. The treasure-keeper does.

And this realization does not invalidate the path—it completes it. Because the true purpose of self-mastery is not to eliminate the need for God. It is to reveal the need for God.

Gibran is saying: Mastery shows us how far human effort can go; life shows us where effort ends; and beyond that border, God waits. This is the true meaning of emptiness.

Emptiness is not: The mind blank of thought, the heart devoid of emotion, the soul detached from life. True emptiness is the profound recognition: “I cannot carry this alone.”

And with that realization, the heart opens—not to resignation, but to trust, to surrender. Then: Peace does not depend on the absence of sorrow; joy does not require protection from loss; balance does not come from perfect control.

Peace arises from the knowledge: “I am held.”

This is the peace that cannot be shaken, even when the scale rises or falls dramatically. Because now peace is no longer: An emotional accomplishment, a philosophical posture, or the reward of training.

Peace becomes: A relationship with the One who holds the scale.

Gibran’s final teaching is not an invitation to transcend humanity, but to fully become human: To feel deeply, to strive honorably, to grow sincerely, and then, having done all we can, to surrender to God.

Because the warrior who has fought, trained, and pushed himself to the limit eventually discovers a sacred truth:

Strength leads to surrender, not because we fail—but because we finally understand.

At the end of mastery, God waits.

At the end of effort, grace begins.

At the end of self-sufficiency, peace becomes real.

This is the treasure-keeper’s message.

This is the meaning of the scale.

This is the truth beyond mastery.

Most people believe the path ends when they master themselves—when the emotions are steady, the technique sharp, the mind disciplined, and the heart clear. And indeed, this is a milestone worth honoring. It is not given to the half-hearted. It is forged in sweat, bruises, effort, humiliation, disappointment, and triumph. Anyone who reaches this stage has already passed through trials that break the average person.

But Gibran is not speaking to the average person—and neither is the Hwarang Warrior tradition.

He takes the student who has climbed the mountain of self-mastery and tells them: “There is still one mountain higher.”

Because even the one who has mastered: Mind, body, emotion, focus, strategy, breath, awareness, and balance still stand before a truth that no amount of training can change: We do not hold the scales.

“Can all your worries add a single moment to your life?”

Matthew 6:27

Life is not weighed by our will.

The universe is not arranged around our desire.

The outcomes of existence are not under our command.

The treasure-keeper—God—lifts the scale, not us.

This realization, for some, is terrifying. For others, disappointing. But for the warrior who has lived deeply, it is liberating.

Because when a person has truly tasted life—not as a philosophy but through experience—they eventually discover: No matter how strong we become, how disciplined our practice, how refined our techniques, we cannot control joy or sorrow.

We cannot schedule blessings, and we surely cannot prevent heartbreak.

As long as we believe that mastery guarantees favorable outcomes, we remain chained to expectation, anxiety, and disappointment. This is why many seekers, after years of training, still feel incomplete—because they are trying to accomplish with discipline what can only be received through surrender.

Self-mastery is essential—but it is not sufficient. It prepares the vessel, but it does not fill it.

Gibran’s teaching is not a dismissal of training; it is the revelation of its purpose: True wisdom begins only when mastery reveals its limits.

The strongest warrior eventually learns: Self-sufficiency is an illusion; human control is temporary; life is larger than personal achievement; and the heart cannot rest on a foundation it must maintain by force.

This does not negate the journey—it completes it.

A beginner seeks control. An intermediate tries to balance control. A master understands: Control was never the goal.

If we try to neutralize sorrow to protect ourselves, we also neutralize joy.

If we flatten our emotions so that life cannot hurt us, life also cannot move us.

If we try to stand alone, we eventually collapse under the weight of existence.

So, Gibran points to the higher truth: The path does not end with self-mastery, but with surrender. Not surrender as defeat, but surrender as recognition: God is the center, not the self; peace is received, not manufactured; the heart is steadied not by personal control, but by divine assurance. This is the only way to experience life fully without being broken by it.

With surrender: Joy remains joy—pure, bright, undefensive; sorrow remains sorrow—real, deep, meaningful; but neither rules us anymore. We are able to feel deeply without being destroyed, because we finally understand: We were never meant to carry life by ourselves.

This is where the path of the warrior becomes the path of the human being: To strive with all our strength, to cultivate our abilities and character, to learn wisdom through experience, and then to kneel—not in defeat, but in truth.

Only then can grace enter.

Only then can peace deepen.

Only then can the warrior’s heart rest.

At this stage: Action arises without arrogance, endurance without bitterness, success without pride, loss without despair because the warrior is no longer the center of their world—the Creator is. Thus: Training shapes the vessel; experience deepens it; reflection polishes it, but only God fills it.

This is the final message that crowns all the others: Self-mastery is the road; surrender is the destination. A warrior is completed not when they become invulnerable, but when they finally discover the humility to say: “I am strong, but God is greater.”

This is the ultimate freedom.

This is the ultimate peace.

This is the true meaning of life’s joys and sorrows.

And this—at last—is the warrior’s final understanding: Not “I have conquered life,” but: “I walk with the One who holds the scales.”

In that truth lies the essence of Hwa Rang Do, the essence of Gibran, and the essence of the human journey toward wisdom, wholeness, and real freedom.

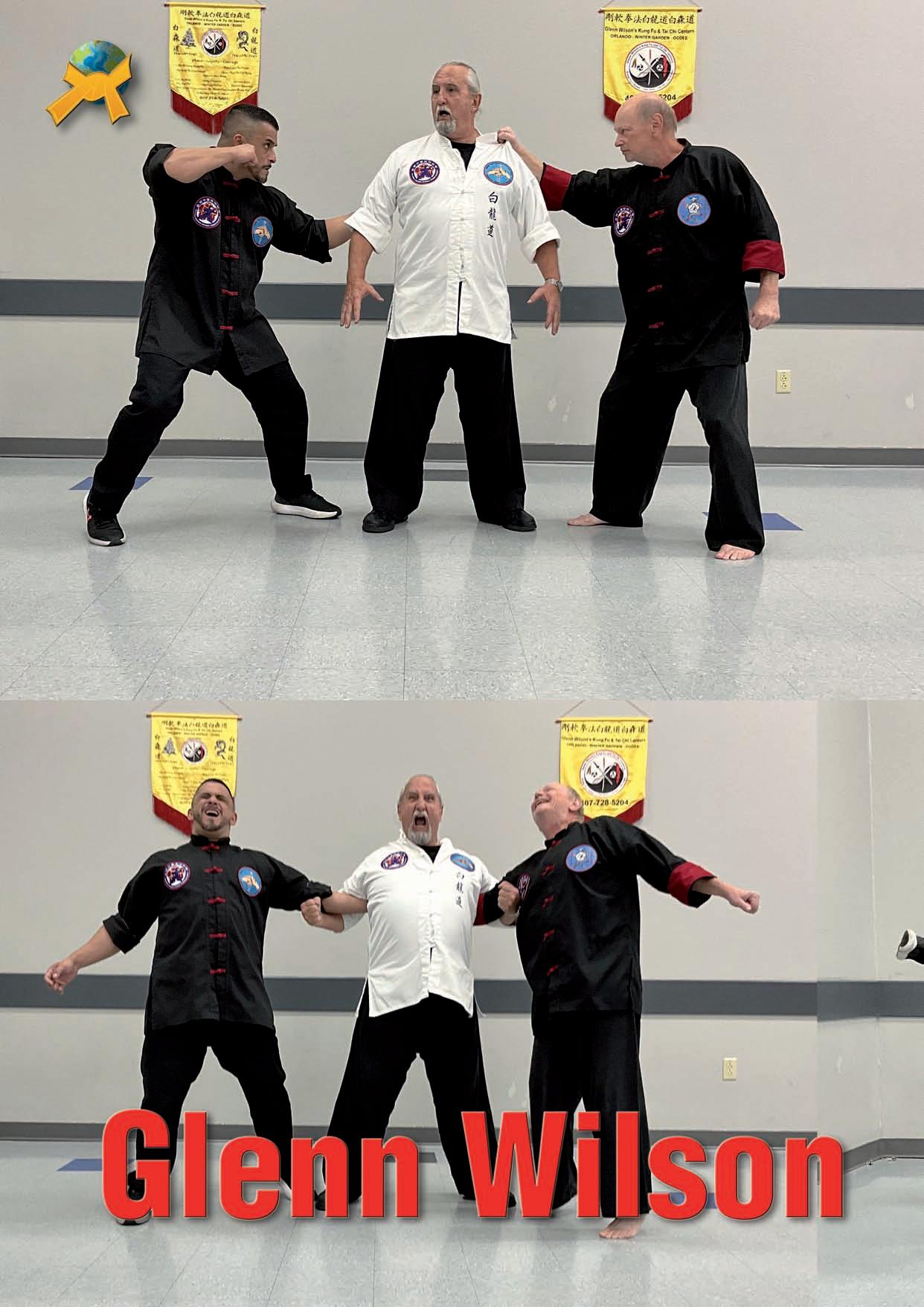

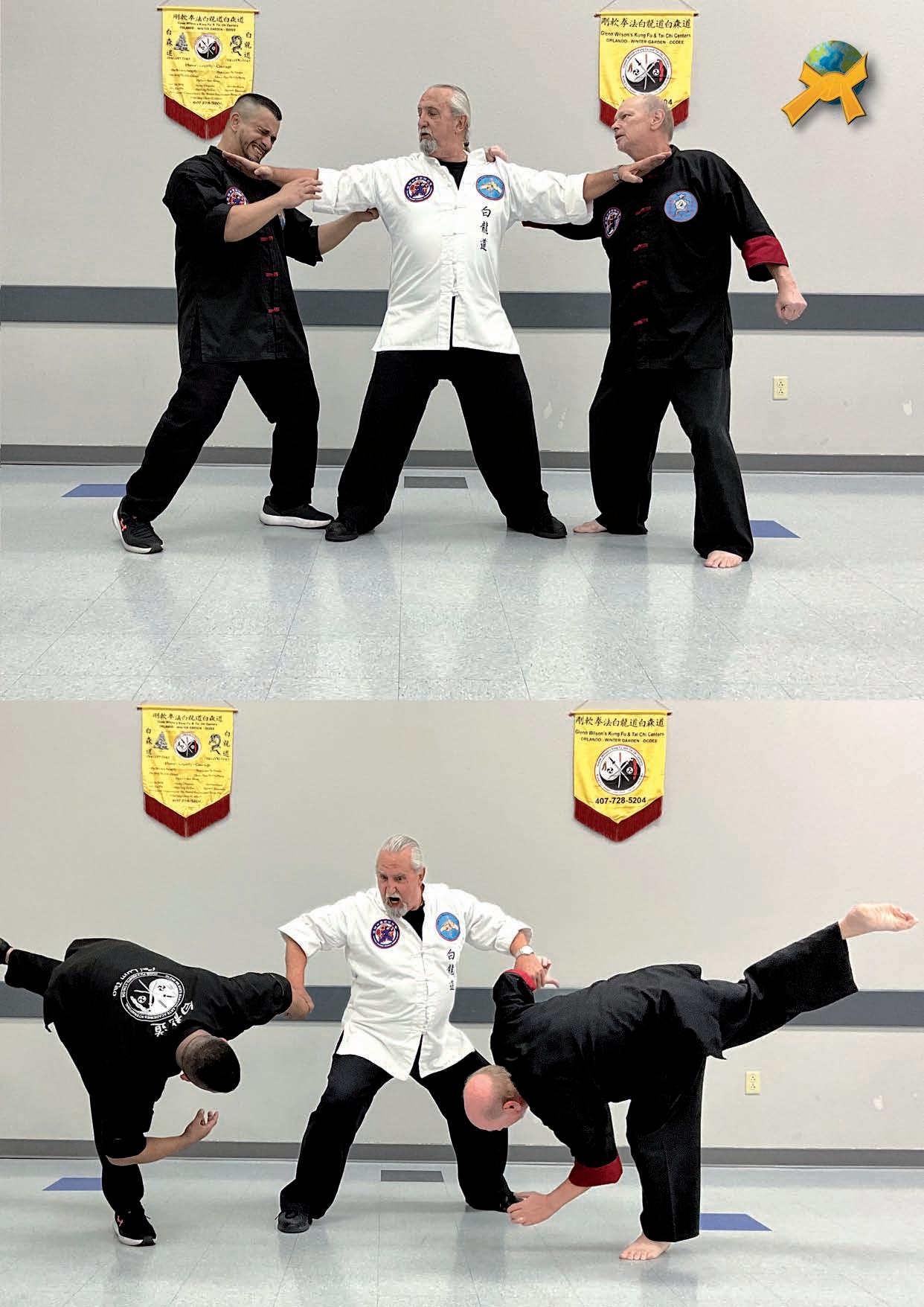

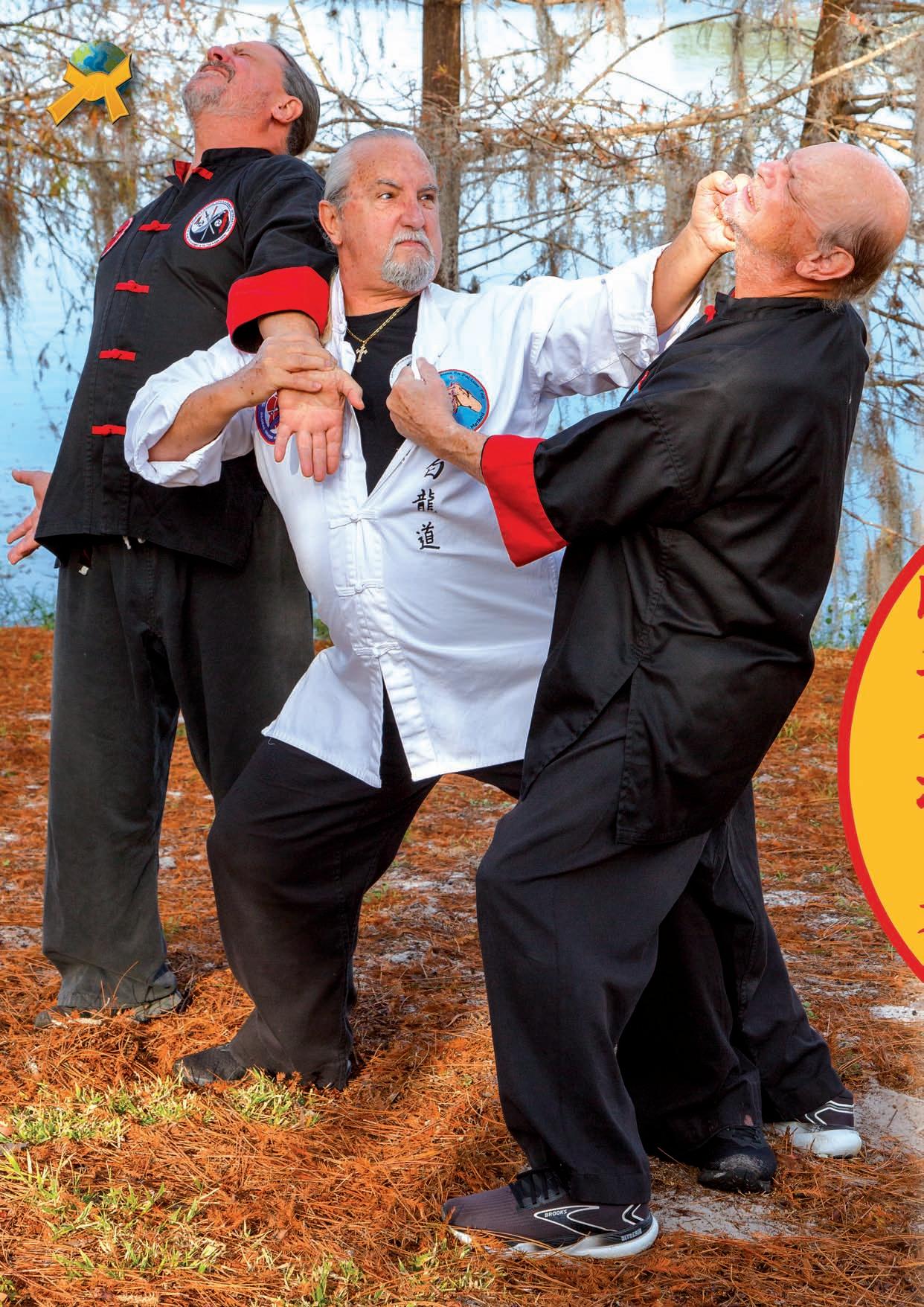

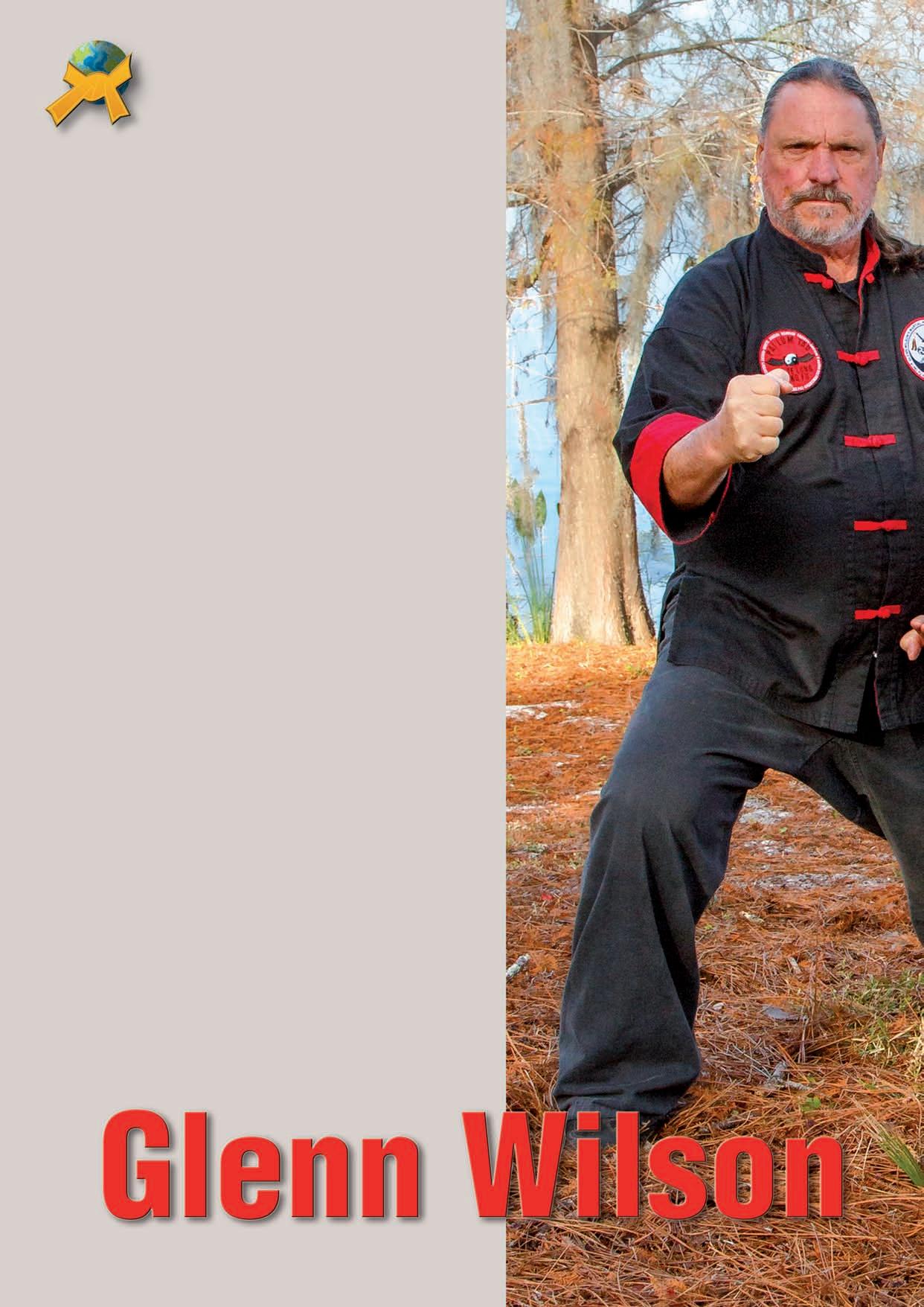

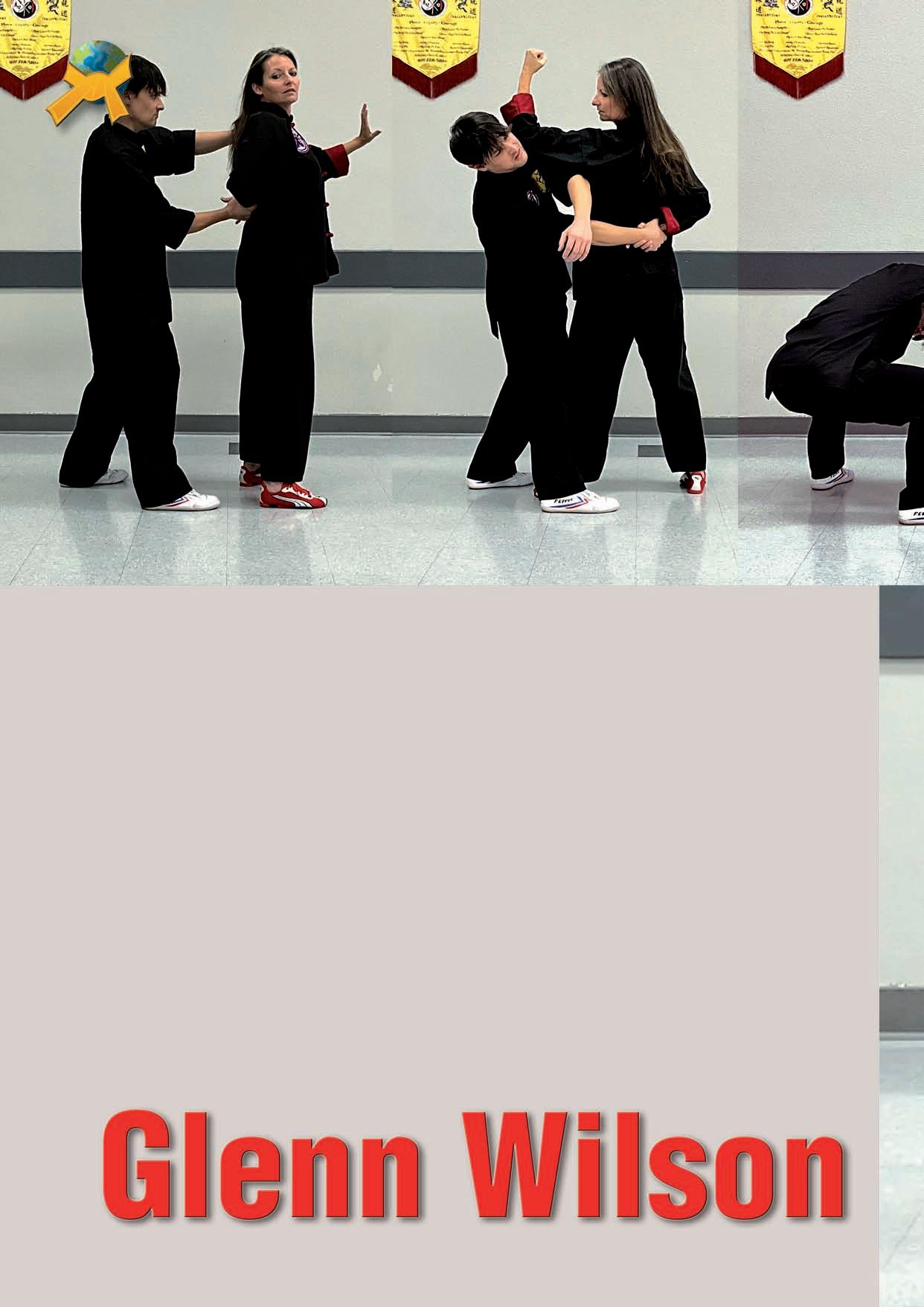

Pai Lum Tao’s Bone Crushing Combat

The history of pugilism in China is vast and diverse to say the least. The development of fighting techniques and styles has been assembled by generations of skilled warriors who drew from personal combat experiences. The theories and formulas generated by such activity were employed in combat by the warrior, who believed that his technique and style would be superior on the battlefield. The warrior would train diligently and thoroughly to master each technique. The warrior could not afford failure; the price for failure was usually death. The warrior's training would form the basis for a unique fighting style, the worth of which would ultimately be proven on the field of combat.

One of the byproducts of this constant development was the White Dragon / Pai Lum Tao system and its highly effective series of ‘Lightning Bolt / Bone Crushing’ punches and kicks. These highly guarded and effective fighting theories are at the very center core of Gong Yuen Chuan Fa Pai Lum Tao. The cutting series strikes to a target using vertical, horizontal, and circular motions. Distinguishing the cutting series from other theories and formulas are its unique composition of linear and circular striking, which are utilized within the implementation of every move.

Even though the technique is gifted with power and explosion, it is the penetration of the ‘Lightning Bolt / Bone Crushing’ punch or kick that highlights its significance. The technique is thrown into the target, but does not stop at it; instead, it cuts through the target. Such devastating penetration and diffusion makes these techniques among the most effective and deadly in the martial arts repertoire.

This series of striking developed from an evolution of fighting styles. Borrowing from the strengths of both Northern and Southern kung-fu, the cutting punch emerged as a powerful combination of motiongenerated power and explosive short-range combat. The power and penetration is second to none in theory and execution.

The Northern styles of Kung Fu are known for their mobile stances and long-range striking. The Southern style enveloped a belief in short-range explosiveness into a target. The Northern style developed sinew strength and power through movement. The Southern style practiced powerful explosion into the target area. From a blending of motion and explosion, the cutting punch emulated venerable qualities of both styles with emphasis on penetration.

The ‘Lightning Bolt / Bone Crushing’ punches employ both gong (hard) and yuen (soft) theories and applications of Pai Lum Tao Martial Arts and martial arts in general. They use either a basic shoulder whipping motion or a figure-eight pattern in which are made a continuous series of punches. The cutting punches and kicks are delivered quickly, often many times a second in a rapid-fire type of delivery, to overwhelm an opponent. This speedy delivery will interrupt the thinking and reacting process of the opponent.

The power and momentum of the ‘Lightning Bolt / Bone Crushing’ punch finds its basis in strong, solid stance work. From the toe, the energy moves into the calf, travels up the thigh, is reinforced by the hip, surges through the waist, shoots up the back, travels into the shoulder, elbow and wrist, and culminates in the fist. The hand technique strikes into and through the target. During the movement, the air should travel from the body via the mouth, directly matching the physical motion of the technique.

While this series is being executed, the body should be relaxed, yet firm: tight muscles or joints should be avoided, as this restricts energy flow, and interferes with sinew and/or muscle movement vital to the proper execution of this technique. Relaxation is necessary to allow the body to express the whipping motion required to guide the path of the punch or kick. Stiff tense motion contradicts the fluidity and adaptability this technique demands.

A key component of the cutting series of punches is that it utilizes linear and circular motions combined into one continuous, fluid and penetrating movement. Different parts of the hand may be used to transform this energy into unique and effective strikes, Pin chuan (flat punch, as in a ram's head punch) cuts with the fore knuckles, driving directly into and then ripping through the target. Basically, the punch penetrates a few inches into the target with a linear motion and then cuts through with a continued circular motion, which results in the hand either being chambered at the body or continuing in the opposite direction (as in a series of cutting punches).

Other hand positions include:

Li chuan (vertical fist, as in sunfist);

Fan sou chuan (reverse hand strike);

Bon chuan (backfist);

Pie chuan (palm slap);

Wye hen sou (elbow/forearm);

Sou den (elbow strike)

Hen chie (chopping wing).

The system of cutting techniques also includes a number of lightening bolt kicks. These can be further distinguished into a subcategory of jumping kicks. Utilizing relaxed, fluid motion focussed on penetration also applies to the kicks.

Among the kicks are:

Ti twe (front toe)

Teng twe (heel strike)

Shi ding (knee strike)

Wye bie (sweeping/crescent)

Nei bie (sweeping/crescent)

Tse tie (side)

The two major jumping kicks are tiao teng twe, which strikes with the heel, and tiao hou teng twe, a rear/jumping spin kick.

Some of these techniques may be recognizable by name as being practiced elsewhere in the martial arts: the distinction is that these techniques are executed in a unique manner. The cutting punches and cutting kicks pene-trate and cut through the target as a single execution. This arsenal of attacking can then be repeated with a barrage of strikes and explosions.

In the Gong Yuen Chuan Fa Pai Lum Tao ‘Lightning Bolt / Bone Crushing’ there is no adjustment of the hand or body in reaction to the target. There is a designated target, but should that target move, the technique is designed to smash and destroy whatever lies in its path. This formula ensures maximum results.

Strict and continuous conditioning of the body and training of the mind is required before these techniques can be properly mastered. Solid stance-work and proper chi kung breathing methods also must already be firmly established before beginning the complete range of cutting technique training.

Prior to THE first‘Lightning Bolt / Bone Crushing’ technique is taught, the student must concentrate on learning proper breathing and acquiring an understanding of the techniques. The techniques are then practiced against the heavy bag, where penetration and cutting through the target is established. Finally, the techniques are worked in two-man sets, with body padding serving to absorb the impact of the punch. These two-man sets polish the cutting: technique and teach the student how to properly take the cutting punch or kick. This training is supervised by qualified instructors to ensure that injuries are kept to a minimum.