Something

BY MAGGIE MONAST

BY JULIENNE ISAACS

BY DIANE METTLER

Something

BY MAGGIE MONAST

BY JULIENNE ISAACS

BY DIANE METTLER

When the teams behind our agriculture brands at Annex Business Media tossed around the idea of a project recognizing women in agriculture, I’ll admit I was hesitant to move forward.

My skepticism wasn’t because I thought women aren’t worthy of recognition, or that we’d have a hard time finding candidates – in fact, it was kind of the opposite.

I started working in agriculture in 2013, and since then, I’ve worked alongside a team comprised almost entirely of women. I’ve met, read about and learned from hundreds of women doing great things within the industry. I grew up listening to stories from my grandparents, who were raised on farms in Canada and Italy, and know that the women who came before me played an important role in agriculture too. Traditionally, being a woman in agriculture meant you would take care of the meals, house and family while men worked the fields or tended to livestock. Make no mistake: these tasks were – and still

But then I realized this was exactly why we needed to go forward with our initiative. It doesn’t matter that women have been playing an influential role in agriculture for the better part of the last century. What matters is that we have to continue to recognize the importance of women in agriculture. The onus is on us to honour the women who have paved the way for us in the past by spotlighting some of the industry’s brightest lights.

Influential Women in Canadian Agriculture will honour six women from all areas of agriculture –farming, research, consulting, breeding, medicine and everything in between. We know that the work women do on farms and partner farms, in the lab or classroom, or behind the scenes at an office is making a difference to the future of agriculture in Canada, and we intend to highlight their important work and contributions through this program.

Please visit www.agwomen.ca to submit your nomination. Nominees

Women have been making their mark on this sector for centuries.

are – important to the success of the farm, but this was a stereotype for many years that wasn’t definitive of every farm wife or daughter. I’m willing to bet my grandmothers and great-grandmothers weren’t the only women helping out in the barn when needed.

With time, a woman’s role on the farm has evolved from the traditional interpretation, but the point is that women have been making their mark in this sector for centuries. When is it not considered “new” anymore?

must be 18 years of age or older and must reside in Canada. After the honourees are chosen, we’ll be sharing their stories with you through podcasts and a special digital edition. Stay tuned – you won’t want to miss what’s to come. •

(888) 599-2228 ext. 277 scroley@annexbusinessmedia.com

Associate Editor ALEX BARNARD (519) 429-3966 ext. 276 abarnard@annexbusinessmedia.com

Advertising Manager SHARON KAUK (519)

Media Designer CURTIS MARTIN

Circulation Manager SHAWN ARUL sarul@annexbusinessmedia.com

VP Production/Group Publisher DIANE KLEER dkleer@annexbusinessmedia.com COO SCOTT JAMIESON Printed in Canada

Mail Agreement #40065710

#867172652RT0001

rthava@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: (416) 442-5600 ext 3555 Fax: (416) 510-6875 (main) (416) 442-2191 Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Occasionally, Manure Manager will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above. Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2019 Annex Publishing and Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertisted. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

The California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) is accepting grant solicitations for the next round of Healthy Soils Program projects, which has approximately $25.2 million available in this round.

The Healthy Soils Program is part of California Climate Investments, a statewide program that puts cap-and-trade dollars to work reducing GHG emissions, strengthening the economy, and improving public health and the environment.

The cap-and-trade program also creates a financial incentive for industries to invest in clean technologies and develop innovative ways to reduce pollution.

The CFDA says the changes to the application process aim to make it easier, provide enhanced tools to assist with information required in the application, and achieve better alignment with USDA programs. For full details about the changes to the program, visit www.manuremanager.com.

Registration is now open for the 2020 World Pork Expo, presented by the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC).

This year’s trade show will be hosted from June 3-5 at the Iowa State Fairgrounds in Des Moines, Iowa. Join more than 20,000 industry professionals for educational seminars, learning about industry innovation and networking.

“There’s truly something for everyone at the World Pork Expo,” said David Herring, NPPC president and pork producer from Lillington, NC. “Anyone in the pork industry is encouraged to attend.”

The expo covers more than 360,000 square feet of exhibition space making it the world’s largest pork-specific event. More than 500

exhibitors will display products and services – from animal health, nutrition, build and equipment, financial marketing, genetics and more.

Sixty-plus companysponsored hospitality tents provide an opportunity to network in a more relaxed setting for porkindustry professionals. Stop by the NPPC tent to learn about current legislation, regulation and public policy

issues that impact pork production through one-on-one discussions with NPPC board members and staff.

The Expo will feature many educational and informational seminars, which will address innovative production and management strategies, and current issues related to the pork industry.

For registration and more information, visit worldpork.org.

To maintain soil organic matter at 2.7%: In the top six inches of soil:

2,000,000 lbs. (weight of top six inches of soil in an acre) X 0.027 = 54,000 lbs. organic matter per acre X 0.03 (3% SOM decomposes each year)

Lost by decomposition = 1,620 lbs. organic matter

20 tons of dairy manure per acre annually will maintain soil organic matter levels.

Approximate application rates required to maintain soil organic matter:

Solid dairy = 15.5 tons/acre

Liquid dairy = 9,400 gallons*/acre

Liquid hog = 23,000 gallons*/acre

Solid broiler chicken = 6.1 tons/acre

Leaf and yard compost = 8.1 tons/acre

*1,000 gallons approximately equivalent to five tons

Potential crop-yield increases of about 12% for every 1% organic matter.

An increase of approximately 80 bushels of corn per acre when organic matter increased from 0.8% to 2%.

Less than 20:1 is the ideal C:N ratio in manure for crop production. Figures courtesy of SARE.org

All other figures courtesy of Christine Brown, OMAFRA.

Kuhn recently announced the latest in their lineup of hydraulic push box spreaders.

The new Kuhn Knight HP 160 features the proven ProPush design in a higher capacity, commercial duty package. The HP 160 with VertiSpread vertical beaters is designed to haul and spread solid materials from dairies and feedlots, including gutter manure, yard scrapings, bedding pack and feedlot manure. The hydraulic push-type design means no apron chains, fewer moving parts and dependable service life.

The HP 160 joins the 2044 and 2054 ProPush hydraulic push box spreader family, but features upgrades and a greater heaped capacity of 600 cubic feet. The all-steel welded frame provides a solid foundation for the spreader’s sides and floor. The solid weldin tongue is cross-braced for strength and rigidity, while the updated pusher design has increased the clearance between the tractor and implement for greater maneuverability. For precise monitoring and application tracking, an optional scale system is available.

Case IH introduces the AFS Connect Steiger series tractor – available in Quadtrac, Rowtrac and wheeled configurations from 370 to 620 horsepower. The robust chassis and massive axles can carry up to 66,000 pounds.

Users can log in to AFS Connect to view current field operations, fleet information, agronomic data and more, remotely keeping an eye on their operation.

AFS Connect Steiger series tractors also feature larger fuel tanks. Producers can keep working long days with no engine regeneration, 600-hour oil change intervals and ground-level maintenance to lower operation cost and keep equipment in the field.

Livestock Water Recycling (LWR), a global manufacturer of manure treatment systems, announced recently that it has been awarded a patent in Brazil. The LWR system makes it possible for livestock producers to achieve environmental sustainability while maximizing farm productivity through water recycling and precision nutrient application, including fertigation.

The water that is recycled through LWR’s system makes farms cleaner and safer for animals and employees while simultaneously reducing the amount of well water that is used for irrigation. Treating manure with the system reduces greenhouse gas emissions by more than 81 percent, and producers have seen crop yields increase anywhere from 30 to 50 percent due to strategic nutrient application.

Agriculture has always been a massive contributor to the Brazilian economy, and Brazilian exports have recently surged due to increased demand from China. The Institute for Applied Economic Research, a public

institution that provides technical support to the Brazilian government with regard to public policies, predicts that the Brazilian agricultural GDP will rise two percent, as farming is expected to grow by 2.8 percent. Livestock may rise 2.2 percent, driven by a two percent increase in cattle production.

While Brazilian agricultural production is expected to grow three times faster this year than it did in 2019, the Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock warns that farmers will face higher costs –such as imported fertilizers – due to a weaker currency. Brazil imported some 26.3 million tonnes of fertilizer last year, according to fertilizer association ANDA, which amounts to three quarters of the nutrients that farmers used.

This presents a significant opportunity for manure fertilizer plants in Brazil, especially given that a recent report cites pig manure as a promising resource for the fertilization of tropical soils, characterized as having low natural fertility.

Brightmark Energy (BE), a San Francisco-based waste and energy development company, continues to build their renewable natural gas (RNG) network, with their most recent addition in western New York. Earlier in the year BE announced a partnership with the Larson family in Florida, and more recently they collaborated with Boadwine Farms and Moody County Dairy in South Dakota. Both projects involve the construction of anaerobic digesters to process the manure produced by the dairies’ cows and capture the resultant methane for conversion to RNG.

In New York, BE will partner with six farms for the Yellowjacket biogas project, which will extract methane from 265,000 gallons of dairy manure per day and convert it to RNG and other useful products.

The AFS Connect Steiger Rowtrac tractors provide fixed-frame configuration, turn like a traditional tractor, and feature the same traction and flotation as all Case IH track systems.

The participating farms – Boxler Dairy Farm, Lamb Lakeshore Dairy, Lamb Farms, Lawnhurst, Swiss Valley Farms and Zuber Farms – already have functioning anaerobic digesters that produce electricity, but some of the digesters are more than 10 years old and have begun to cost more to maintain and operate than they generate in value. Through the partnership with BE, the digesters will be upgraded to function more efficiently and include technology capable of converting biogas to pipeline-quality RNG.

After the planned installation of gas upgrade equipment across all of the farms is complete in early 2021, the project is anticipated to produce about 305,000 million British thermal units (MMBtu) of renewable natural gas each year. This will reduce the net greenhouse gas emissions from the manure processed at a rate of almost 130,000 tons per year, which is equivalent to planting approximately 153,000 acres of forest each year.

On-farm innovations make this Ontario dairy farm the cream of the crop.

BY ALEX BARNARD

Balancing innovation with tradition can be a delicate dance. Breaking from the methods used by those who came before can be difficult – especially on family legacy farms – and newness doesn’t always represent an improvement. But finding a mix that works is a task for each farm, and it’s one that the Johnston families of Maplevue Farms have grabbed by the horns.

Maplevue Farms is located outside of Listowel, ON, in Perth County, the heart of Ontario’s dairy country. The current farm owners, brothers Dave and Doug, are the fifth generation of Johnstons to operate the farm.

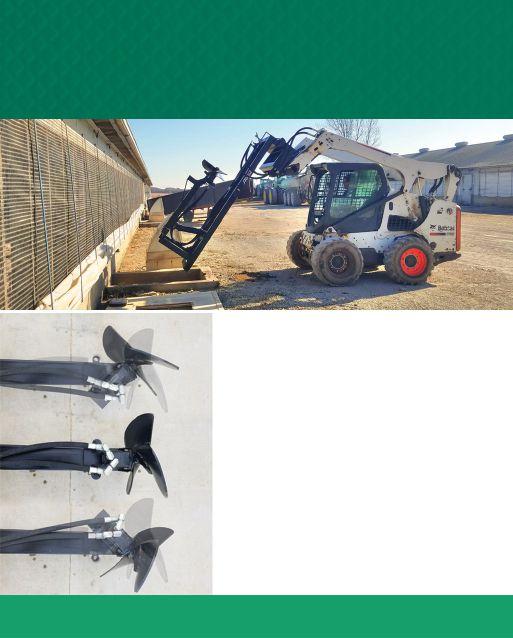

In August, Maplevue Farms

will be only the second Canadian location to host the North American Manure Expo. The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) asked the Johnstons to host this year’s Manure Expo, which will see hundreds of custom applicators, producers and other attendees come to southern Ontario to check out the latest in manure technology, equipment and education. After attending the 2019 Manure Expo in Indiana, Doug thought they could bring something different to the event.

“We’re doing some things that OMAFRA likes to promote,” Doug says. The farm has used many “best practices” for years, including ABOVE

cover-cropping, composted manure cow bedding, crop rotations and minimum-till.

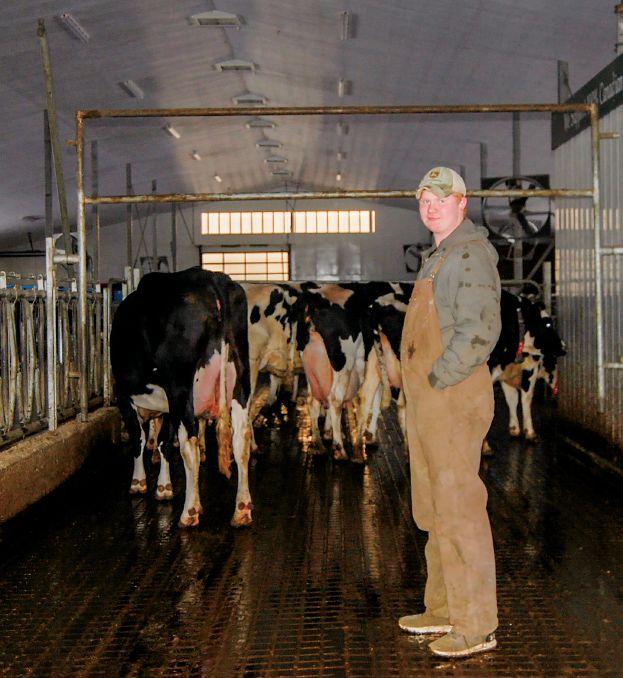

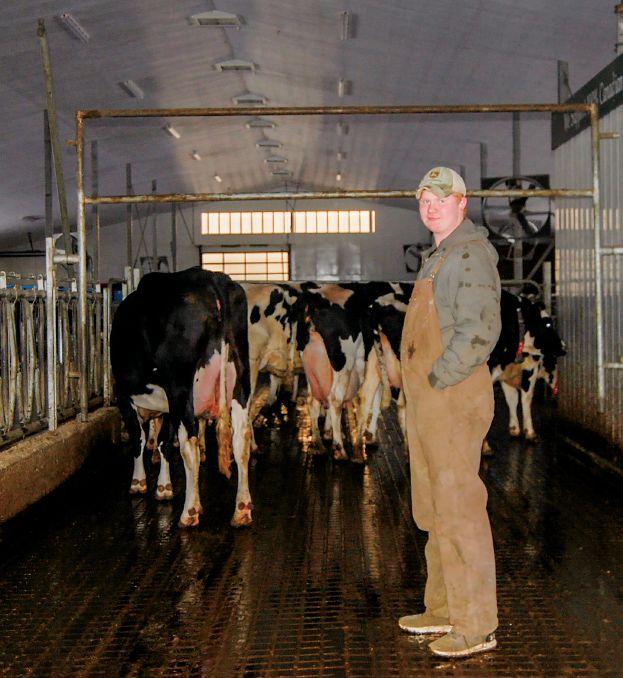

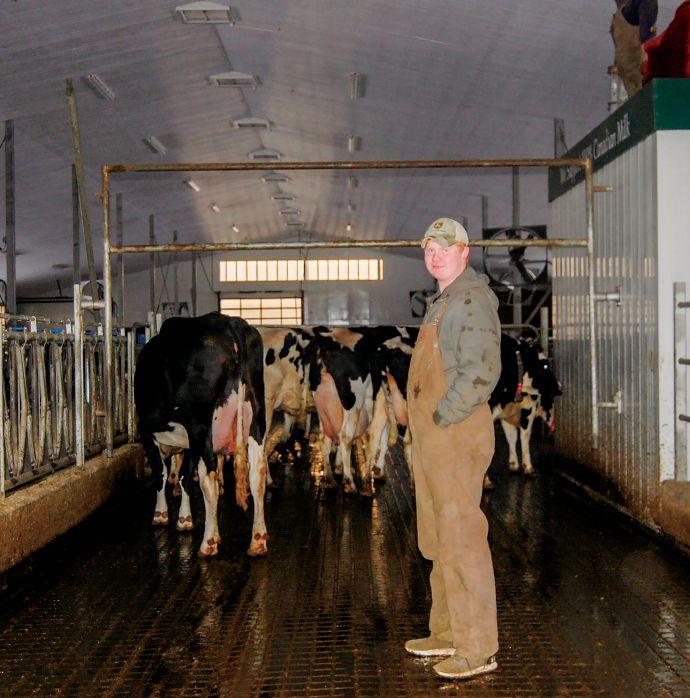

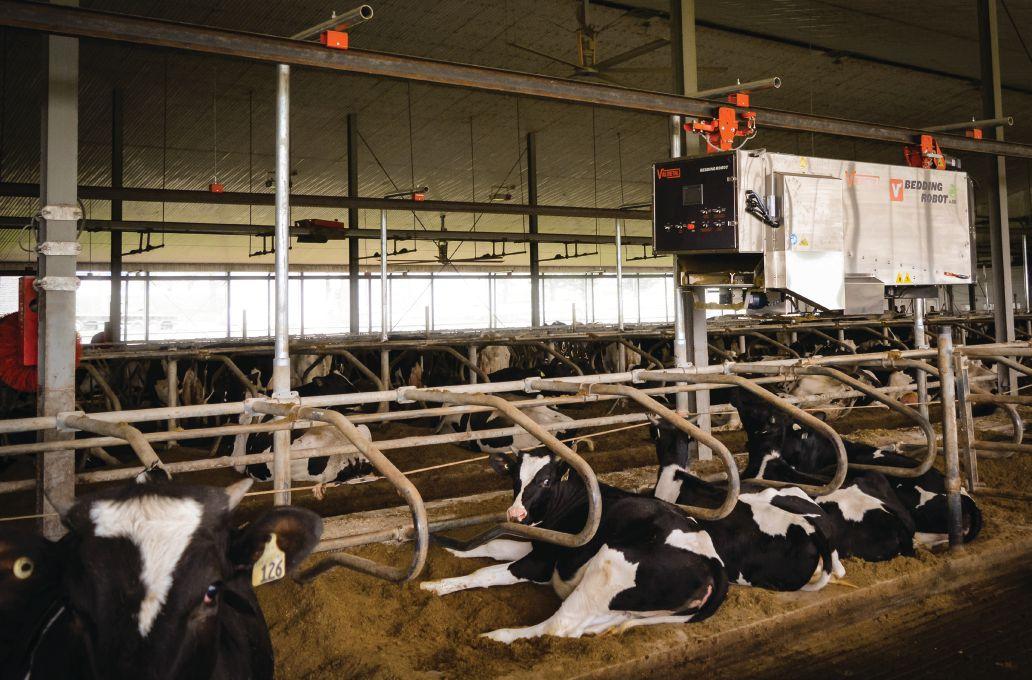

Combined with more recent innovations, like manure collectors and robotic cow milkers, these practices have made Maplevue a farm to emulate.

Maplevue Farms currently has 200 cows on the farm, with 65 being milked regularly. While the brothers have acquired the quota to milk 100 cows and built the new barn to accommodate at least that many, the efficiency and quantity produced by using the new robotic milkers has made 100-head a number to work towards for the future. The robotic milkers have been in place since December 2018, when the new barn was completed. While the technology has helped, the brothers say it was a steep learning curve.

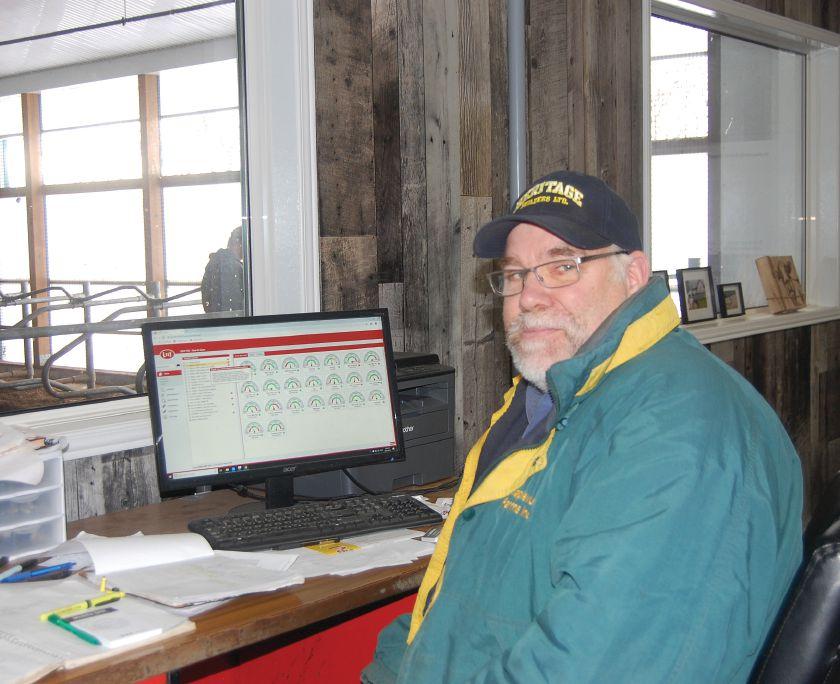

“Now that I know what to look for, it’s easier,” Dave says. “For the first little bit, I was kind of in the ‘old farmer’ stage where you’re going, ‘What the heck am I doing here?’ But you do learn it, and now I find it second nature to sit at the computer and check cows out.

“Most mornings, I walk in the barn –do a walk around, make sure everybody’s okay, make a pot of coffee,” Dave says. “And then the next 10 minutes I sit at the computer and check, and those are the most important 10 minutes of my day –to see what’s going on.”

“We can almost tell a cow is sick before the cow can tell you she’s sick,” Doug says.

“I can closely monitor pretty much everything,” Dave adds. “And you have to know what she did yesterday to know what you’re looking for, too. You still have to know your cows.”

The manure collectors are the newest addition at Maplevue Farms, installed in June 2019. Lely, manufacturer of the manure collectors, sent a limited supply to Canada in their introductory phase, but the Johnstons’ use of composted bull manure as cow bedding made their farm a high priority for installation. Because of the fineness of the composted bedding particles, the manure collectors have no problem sucking up bedding that gets mixed in with the manure, as they tend to with coarser sand bedding.

The Johnstons have been using composted bull manure bedding for years. “Our vet was quite skeptical right off the bat, and now she’s almost bragging about it,” Doug says. “It’s something different, and we’re using a renewable

resource that we’re going to put on our ground anyway.

“We are ecstatic that we have these manure suckers and they’re working really well for us.”

The two manure collectors alternate which side of the cow enclosure they clean; while one is out sucking up manure, the other dumps its contents through a floor grate into storage, fills with water and charges for 45 minutes before going back out.

Though the new technology may take

some getting used to for humans, the learning curve for cows is just one day.

“Once they get used to the noise and the thing moving, cows are fairly easy to adapt,” Dave says.

“I think we’ve had more trouble learning than the cows have, because we have to remember to shut it off when we catch cows, because it won’t stop – it’ll take a cow down,” Doug adds.

The Johnstons use straw for bedding for their heifers, calves and springers, but not for the cows they’re milking.

FAN PR

BENEFITS

▪ Dry Matter content up to 38% in solids when separating cattle slurry

▪ Economical production of high-quality bedding from the manure solids already on the farm. No need to buy additional bedding

▪ High dry matter content even at high throughput rates

▪ Low energy consumption

▪ Press screw and screen basket made of stainless steel

▪ Long life of the auger due to hard metal coating

▪ Including automatic weight control

▪ Including control panel

▪ New robust cage and XC wearing screen

▪ Housing made of cast iron

▪ Permanent cleaning of the screen by the auger

▪ Easy to maintain

▪ Gearbox with NEMA flange allows convenient and costeffective sourcing of US motors up to 15 HP

Life time of waste parts is depending on the consistency of the manure and the dry matter of the plug.

Separator GREEN BEDDINGTM 3.3-780 HD

Capacity up to 3 cubic yards of bedding material per hour

Dry matter content up to 38%

Input power max. 15 HP

Screen size 0.75 / 1.0 mm

motor pump gear unit design

Dave and Doug’s mother, Marcie, emphasized succession planning as a part of farm management. This made the transition easier when their father, Sam, passed away suddenly and unexpectedly in 1998, and when Marcie passed away from cancer a couple years later.

“We’ve basically been here now for 20 years with no grandparents [for the kids],” Doug says. “It’s been an interesting go.”

The brothers have been in charge since the late 1980s, when Sam told them that he no longer wanted to run the farm.

“I was already doing all the books. So, the transition was already well underway,” Dave says. “It was just, you missed that shoulder to lean on and the guidance.”

“Succession planning was always a forte of my mother’s, and she pushed it all the time,” Doug says. “We used to have monthly meetings within the family.” The brothers began having more regular conversations about succession with the construction of the new barn and the meeting space it contains.

“We probably have the bad problem that we have too many kids interested in farming,” Doug says. Their seven combined children – Doug has three, Dave has four – might not end up in farming, Doug says, “but they’re all interested in the agriculture business.”

“We try to have fun farming,” Dave says. “With my kids, Doug’s kids, whoever – I try to make coming to the barn enjoyable, so that they want to come to the barn.”

The two brothers have a policy for their children when they finish their education: rather than return to the farm immediately, they suggest the kids find a job off-farm to gain some varied experience.

“We’re not worried about them not coming back,” Doug says. “We’re actually trying to figure out how we can fit as many as we can in. It’s a nice problem to have, but it’s a problem.”

Marcie was also a school teacher, and for 25 years every fifth-grade student would visit Maplevue Farms. Now, the brothers find that their former classmates want to bring their own children to the farm to have that same experience.

“In a rural school, you have two kids out of 25 that are from a farm,” Doug says. “We’re under two per cent of the population now that are actual farmers. So, we’re trying to help out by helping educate the public.

“And this is part of the reason that we don’t mind hosting the Manure Expo either, because I think people need to see the technology that’s in manure, too. [The manure’s] not something that we get rid of.”

All of these innovations and practices are part of one cohesive whole. How do the Johnstons approach whole farm management? “Running it like a business,” Doug says.

“But it’s right from one end to the

other. From nutrient management, to rotation of crops, to the genetics we use on our cows, to financial planning: it’s the whole farm picture, and that is what is so hard to teach,” Dave adds. “You can teach some of it, but most of it you learn year after year.”

“And we don’t do things because Dad always did it that way.” Doug says. “We always change things to try to say, why are we doing it this way? Does it make more economic sense to do it this way? We may not get top yields; we might get a more economical yield.”

Doug and Dave Johnston (center), surrounded by their wives and children. From left to right: Lexi, Devin, Brooklyn, Laura and Doug; Kaleb, Dave, Seth, Christine, Sam, Hannah and Laura Empringhan (Sam’s girlfriend).

“It’s also the public image,” Dave adds. “Farmers, we have to watch our public image, watch what we do, even how we drive on the road with tractors.”

The scrutiny farmers find themselves under is just one more thing Dave and Doug balance in the business of running a farm. It’s a job that requires them to wear many hats, but they find ways to make the job their own.

“For me, whole farm management is looking after every aspect,” Dave concludes. “It’s the complete circle. And we have different areas of expertise. Don’t ask me what kind of corn we grow, but don’t go out and ask Doug what name is on cow 1163 and her pedigree – I can tell you that.”

“Trying to be good at a lot of things, but not being too proud to bring expertise in when you need it, too,” Doug adds. •

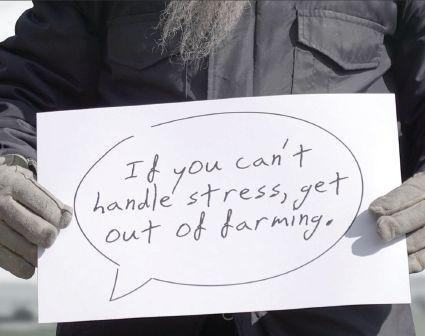

The dairy industry is a critical part of the landscape, economy and social fabric of the country. But it’s under stress.

Dairy is in the fourth year of an economic downturn in which many farmers have struggled to break even. Dairy farmers across the U.S. are highly motivated to increase their resilience to unfavorable economic and environmental conditions, including highly variable milk and feed prices, unpredictable farm policies and extreme weather – most notably increased heavy rain events and flooding.

Most of these factors are out of farmers’ control, but conservation is something farmers can be sure of. My colleagues and I concluded this after digging into the budgets of four Pennsylvania dairy farmers in our new report: How conservation makes dairy farms more resilient, especially in a lean agricultural economy. The report shows how conservation practices, including manure storage, nutrient management, cover crops, conservation tillage and stream fencing, generate a variety of financial benefits, including reduced labor hours, savings on external feed and bedding, and lower vet bills due to improved herd health.

Specifically, our analysis found that manure storage options have high capital costs and almost always require supplemental grants or other sources of funding. However, the farmers that were able to improve manure management realized significant benefits beyond water quality improvements.

Additional benefits to manure storage included improved nutrient management, which was

cell count – a measure of milk quality.

Another farmer from the study, Farmer D, invested in manure storage that holds six months’ worth of liquid manure in the summer and three months’ worth in the winter, helping him get more value out of his manure through better utilization and improved crop yields. He said, “We’ve been doing conservation here for decades, but taking the plunge to install our digester took us to the next level. We have no regrets from installing technologies that provide these environmental and economic benefits to our farm.”

Too often, these economic benefits are not recognized or quantified because farmers’ recordkeeping tools aren’t set up to easily connect agronomic and financial sides of the business. Farmers, their advisers and other stakeholders often take too narrow a view of the costs and benefits of conservation – looking at a single practice for a single year – which means they miss a large part of the picture. Presented this way, much of the economic value is hidden.

associated with increased yield; there was also a host of benefits from manure separators, which allowed farmers to use manure for bedding instead of wood shavings, resulting in significant savings on bedding costs, vet costs and reduced cow mortality.

One farmer, identified anonymously in the report as Farmer A, said, “Implementing better conservation strategies, especially manure management, has changed our farm for the better. Our manure separator has hugely impacted our herd health and reduced our costs, in addition to the other positive changes we’ve made over the past decade.”

While reduced bedding costs were expected from the switch in manure management, an unexpected benefit was the improvement in cow health. From the switch in bedding, participating farmers saw their herds experience reductions in mastitis, leg infections and mortality, and an increase in somatic

The real value becomes apparent when farmers see the economics of conservation within the context of their entire operation and tallied over multiple years. By looking at conservation in the context of overall farm budgets, farmers can see the impacts on yield, herd health, input costs, labor costs and more, and understand how combinations of practices have a larger positive impact than expected based on the individual instance. Finally, our analysis found that investments in conservation have increasing returns. Specifically, farmers who have access to additional financial assistance for conservation through cost-share programs and grants are typically able to make larger investments in practices like manure storage that achieve even greater economic and environmental benefits.

Increasing financial support for farmers through government programs, tax incentives and other innovative financing strategies is an important next step to making the dairy industry more resilient in the face of economic and environmental pressures.

It’s my hope that this report will help dairy farmers and other producers sustain their way of life for generations to come. •

Maggie Monast is the Senior Manager of Economic Incentives for Agricultural Sustainability at the Environmental Defense Fund. Learn more about this report and EDF’s other farm finance analyses at edf.org/ farm-finance.

Cycling nutrients of animals, soils and plants by effectively managing manure.

BY DONNA FLEURY

Effectively managing and cycling nutrients – in animals through feed rations, in soils through manure applications and back through crops – is a fine balance. Nutrient management planning, feed ration analysis, manure testing and soil testing are all important components of balancing nutrients throughout the feeding and cropping system, and optimizing performance of animals and crops.

“Along with the ability to supply important nutrients, manure contributes to a positive effect on plant growth by enhancement of soil organic matter, contributing to important soil physical attributes such as water infiltration and storage, soil structure and others,” explains Jeff Schoenau, professor of soil science at the University of Saskatchewan.

“Manure typically doesn’t have the nutrient balance that crops always need, so both manure testing and soil testing are important to determine the necessary adjustments, such as supplementation with commercial fertilizer. In some cases, unbalanced manure fertilizer application can lead to high soil test phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) levels beyond what crops can utilize, and possible supplementation with commercial fertilizers may be required to balance crop requirements.”

ABOVE

Livestock producers can also adjust animal diets to optimize animal performance, manage feeding costs and potentially reduce the amount of nutrient output that needs to be managed for crop production. “The concept of what goes into the animal as it affects what comes out in terms of nutrients is important,” Schoenau says. “Feed testing to understand the nutrient content for each feed ingredient and bioavailability can help balance and optimize the animal diet, and also assist in managing nutrient output in the manure.

“Any time there is a change in the feeding ration, analysis of the manure is a good idea to see how it may have affected the composition. The manure analysis determines the total nutrient content and helps predict the availability of those nutrients in order to make the best prescription for its use as a fertilizer when applied out in the field.”

With nutrient management, all sources –including manure – must be applied using the 4R principles – the right source at the right time, right place and right rate. Applying the 4R principles to manure is an effective way of getting maximum economic and agronomic benefit to plants while minimizing the risk of losses. Schoenau notes one

Variable rate application of cattle manure using a JBS manure spreader to the University of Saskatchewan Livestock Forage Centre of Excellence Beef Cattle Research Feedlot precision manure application research site in early May 2019.

important finding from their long-term research trials is when manure is managed the right way, nutrient loading and runoff issues do not appear to be a concern. Losses are minimized when manure is applied at “agronomically right rates,” or the rates at which the nutrient applied is balanced or matched by the amount of nutrient that leaves the system in crop harvest over the years. Precisely managing manure and fine-tuning rates can improve those responses and economic returns. One challenge of utilizing manure is

the dilute nature, with low concentration of nutrients per unit weight or volume compared to conventional fertilizer, and the amount required to apply at an agronomic rate. Applications of a few thousand gallons per acre of liquid effluent or a few tons per acre of solid manure are typically required in order to supply nutrients at an agronomic rate.

Schoenau adds, “Liquid manure sources tend to have a higher proportion of nutrients in available forms that plants can immediately use and are more valuable in

providing available nutrients in the short term. Solid manure tends to have a lesser proportion of nutrients in inorganic forms that plants can immediately use, and the organic forms that dominate have to be converted or mineralized into inorganic plant available ions.

“The slow release of available N from decomposition of organic matter in manure typically provides available nutrients slowly over several years,” he says. “There are other important balance relationships – such as the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio in solid manures, the available nitrogento-sulphur ratios in liquid manures, and the nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio in all manures – that we need to pay attention to so we get the best benefit out of those manure nutrients.”

One of the tools available to livestock producers is NMAN, a database of various animal manure samples, part of the larger AgriSuite – tools and calculators developed by the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). “This database, which now probably numbers over 15,000 samples, is continually updated, including the nutrient values of N, P, K and micronutrients,” explains Christine Brown, Field Crops Sustainability Specialist with OMAFRA. “When doing a manure analysis, it is useful to compare your farm’s nutrient analysis with the database averages to see how they compare.”

Differences can be an indication that the ration needs to be tweaked. If some of the nutrients are higher than normal, it would be a good idea to talk to a nutritionist to understand why. It can also be a way to manage the nutrient levels in the manure, such as the use of phytase in pig and poultry rations for managing P, both for improving feeding efficiency and reducing nutrients in manure.

Brown emphasizes that without a manure analysis, understanding the value of the manure resource is difficult, as is determining application rates, timing and potential environmental outcomes.

“Along with manipulating nutrients in the feed ration, the manure analysis helps with manipulating nutrients at the pit or manure management stage and in the field application,” she says. “For some manure types, the nutrients can settle out in the pit, which provides an opportunity to manage nutrients differently. For example, pig manure can settle out in the pit leaving the top layer (first two or three feet) with high ammonium N but very low P levels.

“It is important to know where the

nutrient layers change and make sure to test the manure. One strategy is to skim off this low P/high N layer and use it on corn fields that require high N inputs, but no additional P. The remainder of the manure that is higher in concentrated nutrients can be applied to fields further from the storage after harvest. This seems to work for liquid pig manure, but not liquid dairy manure.”

Brown adds good samples can help to fine-tune the application. “Mixing those samples together will give you a good idea of the average nutrient levels going

into those fields, and help to fine-tune the additional commercial fertilizer that may be required usually for N but not for P or K, depending on the crop,” Brown says.

“The available N from the analysis is based on corn crop requirements, so other crops, such as wheat [which needs the nitrogen earlier in the season, when cool soils may delay availability], may result in a different application recommendation. We are encouraging producers to get a full analysis that includes organic matter, C:N ratios and a full nutrients package to

FEATURES AND BENEFITS:

• Oil bath bearings - self cooled and lubricated, needs no water flush

• Disintegrator tool - for hoof blocks and other solids

• Heavy duty seal and bearing systemlonger life in severe service

• Ductile iron casing and bearing housingheavy castings for long life

• Heat treated cast steel wear parts - for longer life in abrasive grit service

• Most parts readily available from stock for expedited delivery

APPLICATIONS INCLUDE:

• Digester Feed

• Digester Mixing

• Small Pit Recirculation

• Tanker Loading

• Flush Water

• Feeding Heat Exchangers

• Manure Transfer

• Separator Feed

not only help with better manure nutrient distribution to fields, but also to assist with manure being traded or sold for nutrient sources to other growers.”

There are some other factors to consider when recycling manure nutrients back into forage feed that is going to be fed again to livestock. “Manure in general tends to be quite high in available K content, so producers need to be aware that lands that have received repeated manure applications may have an excess of K relative to calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) in the soil. This can ultimately produce a high ratio of K to Ca and Mg in the subsequent forage crop that could cause issues with tetany or milk fever in the cows,” Schoenau says.

“In a past research trial using low disturbance injection of liquid manure into forages – in one particularly cold, dry spring where forage growth was restricted – we had issues where grass at one of the sites had a fairly high nitrate content. In another in-field winter feeding trial with bales of differing N contents and C:N ratios – where the bales were fed, the forage growth the following year was positively influenced both by the nutrients in manure deposited in the field and also the nutrients from the leftover feed. These issues emphasize the importance of feed testing along with manure and soil testing as part of the nutrient utilization toolbox.”

Schoenau is currently involved in a research project at the University of Saskatchewan Livestock and Forage Centre of Excellence, looking at performance of variable rate precision application of solid cattle manure for barley silage production. “The preliminary results indicate the VR application worked well and was able to even out the productivity across the land area, identifying those low-lying areas in watershed basins where manure application rates could be reduced or eliminated without yield penalty,” he says.

“We need to strive to effectively recycle those nutrients in a system. A good example is where the animals are consuming feed from a land area and producing manure – and its associated nutrients from the feed – that is recycled back into the soil to grow more feed.”

For both livestock and crop producers looking to fully understand and optimize feed and nutrient management, the AgriSuite planning tools are a great place to start. The tools are useful for managing different types of feed rations, manure and crop nutrients, and alternative nutrient sources like anaerobic digestate. Visit Ontario.ca/agrisuite to access the tools. •

Reducing whole-farm greenhouse gas emissions through diet and manure management.

BY JULIENNE ISAACS

An innovative study at the University of Manitoba is exploring how different animal and manure management strategies influence whole farm greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in cattle production systems.

The study, which is co-led by Kim Ominski, a professor and associate head in the department of Animal Science, and Mario Tenuta, a professor of applied soil ecology in the department of Soil Science, began in 2017 and will run until 2021.

It’s unique for its layered approach: the project “stacks” feeding, animal and manure management practices to optimize nutrient efficiency and reduce net GHG emissions from stockpiled manure.

Ominski’s role in the project is to oversee animal management and supervise graduate student Rhea Teranishi, who is conducting a feeding experiment to assess four different diets designed to reduce methane (CH4) emissions.

Tenuta’s role in the project is to analyze emissions – direct nitrous oxide (N2O), indirect ammonia (NH3) and methane emissions – from stockpiled solid manure from feedlot-fed cattle consuming the four different diets.

Diet has a huge influence on emissions, Tenuta says. “The biggest factor impacting N losses in the manure itself will be the amount of protein that is ingested as part of the feed – the percent of N that the animal is taking in as part of their diet ration,” he says. “The lower the protein, the lower the nitrogen output.”

But the research won’t look at diet alone: Tenuta says an important factor in the quality of manure is bedding management. When cattle are confined over the winter, bedding is provided; any resulting solid manures will include bedding material, which changes manure composition.

Ominski and Teranishi are conducting the feeding experiment at Glenlea Research Station in collaboration with the University of Manitoba’s National Centre for Livestock and the Environment. A team of dedicated technicians is responsible for much of the experiment’s implementation.

The cattle, on loan from area producers, are fed four diets: a low-protein grass hay diet, an adequate protein grass hay diet that serves as a control, an adequate protein grass hay diet supplemented with sunflower screenings, and an adequate protein diet with grass legume hay.

“We know low protein diets cause higher methane emissions because there’s an element of the nutrient profile missing in the rumen. Low protein is one of the strategies by which methane is increased,” Ominski explains.

Teranishi says she expects higher emissions from the first diet and baseline emissions from the adequate protein (control) diet.

“We had a grad student a number of years ago who looked at different solid manures with different ratios of bedding, and the highest composition of bedding resulted in the lowest nitrogen losses when applied to surface soil,” he says. “That got me thinking: we can control the bedding amount, so if we alter the amount of carbon added to manure in bedding, let’s see if that ties up carbon so we can add it to the soil.”

ABOVE

“The third diet is adequate protein hay but similar in quality to the second diet, and we supplemented that diet with sunflower screenings,” she says. “Fat has been shown to reduce enteric methane emissions in other trials.”

Ominski says incorporation of fat can be challenging – it can form only a small amount of the animals’ diets due to the risk of digestive disturbance. Balance is key.

The last diet, Teranishi says, contains slightly higher protein content than the two previous diets, and it contains a legume that has been shown to reduce enteric methane emissions.

The potential for supplementing animal feed with oilseed byproducts is of great interest to the industry, Ominski says.

“Low protein diets typically cause higher methane emissions, and that’s why there are opportunities here to add byproduct feeds,” she says. “Balancing diets to meet requirements is kind of a win-win, because feeding animals byproducts reduces enteric methane emissions and typically improves performance.”

Master’s student Rhea Teranishi stands with cattle in the feeding experiment.

Tenuta adds that a protein deficiency can impede animal performance, but there is room to adjust protein levels. Livestock producers want to know if they can utilize such “waste” products as oilseed production increases on the Prairies.

Manure stockpiles used for the experiment are housed in a covered structure with open sides, and measure roughly 15 square feet at their largest and about eight feet tall as they shrink over time.

Tenuta says he has not been satisfied with past techniques for measuring nitrogen losses from piles; this study uses a new approach. A hood made of furnace ducting and measuring about 29.5 by 79 inches (75 by 200 centimeters) is placed on the top of the pile.

“We flow air into and out of the chamber, and [attached to the hood is] an instrument that’s a multi-gas analyzer, so we can sample the gas going into and out of the hood,” he explains. This instrument is called a “constant flow flux chamber,” and because the piles are aerated, the atmosphere from the pile is convected upward and out of the pipe.

Flux chambers are constantly gathering readings on a given pile, but the researchers move them around three times a week, Tenuta says.

The research team will collect readings on losses of ammonia, nitrous oxide and methane, as well as carbon dioxide, from the pile. They’ll also collect readings on nitrogen dioxide, which is not a GHG but is a pollutant that can produce smog and react with ozone.

Ammonia losses are problematic due to odor, but they’re also a significant source of nitrogen loss from manure. Nitrous oxide is also a significant GHG that can be released from aerated or stockpiled manures. Methane is produced by cattle rumen but also wet stockpiled manure, Tenuta says.

The experiment hasn’t been underway long enough for researchers to draw conclusions. Early on, when the piles were first set up, Tenuta says carbon dioxide and ammonia emissions are high as microbes begin to degrade the material. When wet material is added to piles, methane emissions increase, but they stop once the piles dry down.

Emissions from stockpiled cattle manures have never been measured in this way, and the researchers are excited about potential applications, he adds.

The experiment doesn’t reflect producers’ practices – most manure piles are larger and taller than those in the experiment to minimize surface area water can reach. But it will add to the industry’s knowledge of how animal and manure management practices influence emissions.

“Producers think of their animals as being part of the landscape, and a very beneficial component of the landscape,” Tenuta says. “They are interested in what they can be doing with animal diet to reduce nitrogen losses. They’re thinking about the system beyond their animals, and how their animals can impact environmental processes.”

Extension efforts will be directed at producers to communicate the results of the study on its completion, Ominski says. •

We’re looking for six women making a difference to Canada’s agriculture industry. Whether actively farming, providing agronomy or animal health services to farm operations, or leading research, marketing or sales teams, we want to honour women who are driving the future of Canadian agriculture.

A renewable energy power plant is up and running in North Carolina.

BY DIANE METTLER

It was years in the making, but this past October, North Carolina’s Power Resource Group (PRG) flipped the switch of its $32 million power plant in Farmville, NC.

“You spend so many years dealing with finance, engineering, permitting and building everything – the highlight is flipping that plant on and and watching it operate,” PRG’s CEO Rich Deming says. “You see that number flicker and the power starting to go in the grid. It’s pretty exciting.”

The Carolina Poultry Power facility in Farmville – owned and operated by PRG – converts turkey waste into electricity and sells it to local utility Duke Energy. It generates two megawatts (MW) of power and 75,000 tons of steam per hour, using more than 250 tons of turkey waste a day.

In the heart of North Carolina’s farming industry, PRG leases a 167-acre farm. The company uses six buildings, each three and a half acres in size, where the litter is dried out and

ABOVE

treated. Combined, roofed areas can hold more than 40 days’ worth of feedstock.

“We don’t deal directly with the farmer,” Deming says. “We deal with the hauler who goes around and cleans out local poultry houses.”

PRG works with only one hauler – Shawn Mitchell of Mitchell Farms in Dudley, NC, who owns a fleet of trucks and hauls 1,600 tons a day.

“We have to have 250 tons a day no matter what, so we got the biggest guy with the most stability that we could find to rely on,” Deming says.

“There are about four of these energy projects, including ours, within a 200-mile radius, and Shawn delivers to all of them.”

One of the issues with poultry waste is that it’s mostly distributed on the land as fertilizer, which means that the chemical components not used by the crops can end up in runoff ditches, creeks and streams, and larger waterways.

“At our facility, those components end up in the

The Carolina Poultry Power facility in Farmville, NC, converts waste from area poultry farms, using more than 250 tons of turkey waste per day.

ash, which is then used by the fertilizer industry for a more tightly controlled application,” Deming says. “Little is lost into the waterways.”

In addition to preserving the purity of the water, using litter as an energy resource prevents a substantial amount of methane from being released into the atmosphere, something that naturally occurs when composting outside.

Deming found the science of renewable energy fascinating, particularly waste energy and biomass projects, because they provide a solution to waste management issues while also generating energy.

“I was the president of a construction company until 2004 and I really wanted a change. So, I quit and really dived deep into renewables. I got involved with biodiesel and solar, and eventually I found my way to waste energy and biomass projects. I love this waste energy stuff, because you’re taking care of a waste problem at the same time you’re creating energy.”

Deming worked on several waste energy projects through the last recession. Afterwards, he worked as a consultant to developers and supervised the building of several projects until he went out on his own in 2013. The Farmville plant is the first one fully under Deming’s direction.

In designing the plant, Deming focused on finding the most cost-effective method to maintain and manage plants using waste as an energy resource.

“When I started, there was a large company from England called Fibrowatt that tried to come into North Carolina,” Deming says. “Their approach was to build

Carolina Poultry Power generates two megawatts of power and 75,000 tons of steam per hour.

a massive plant, what I refer to as utilityscale. The problem with utility-scale is, it’s a hundred trucks a day going into and out of that facility. You would need a Title V Air Permit for the emissions. It’s just not an efficient way to do this. It’s almost like in the old days with incinerators and all the associated problems.”

Rather than a massive utility-scale approach, Deming decided to use what he termed an industrial-scale utility approach, where PRG co-locates their plant next to an industry or industrial park that can use the heat, which is a byproduct of creating electricity.

PRG keeps its plants small enough to have a Minor Source Air Permit, which saves money and also makes monitoring air emission controls much easier, although it is more difficult to find the perfect elements for a plant site.

“It’s a lot trickier the way we do it,”

Deming says. “We’ve got to really find the right location, where we can be in the right place in relation to the feedstock and in relation to an off-taker of our thermal energy.

“We are very precise in what we’re looking for. There has to be convenient access to a waste facility with a tipping fee, or is subsidized with an REP (renewable energy portfolio). It has to be a thermal load. There also has to be the right interconnection set up, so we are able to cost-effectively interconnect with the grid.”

In finding locations for plant sites, PRG usually starts with what Deming terms a “pain point” – an issue that needs a solution, like farmers with a waste disposal problem. Those are the farmers PRG wants to find.

“We can usually figure out most of the other stuff one way or the other, but locating the waste is the key part. The second part is interconnection to utilities.”

PRG already plans to expand their wasteto-energy facilities.

“We will build another poultry project, which is supported by North Carolina

Renewable Energy certificates, which you don’t have in most States. But those are running out. We have about five projects in the pipeline, and we’re going to get started on a couple of them by the end of this year,” Deming explains.

“It will be late 2021 or early 2022 before those go online. So, we will probably look for a couple more in that timeframe.”

After building the one plant using strictly poultry litter, PRG plans to move

to a different mix of feedstocks, such as combining swine with poultry, or even different kinds of waste from other industries.

One of the most intriguing avenues the company is exploring is taking both swine waste sludge and waste from wastewater treatment facilities to create a blended fuel using a more highly

With one plant built using strictly poultry waste, the company is hoping to expand future projects to include other types of waste.

combustible resource.

“You can mix something that’s a disposal problem, but doesn’t have a lot of energy value, with something else that’s a disposal problem and has an extremely high amount of energy value –like unrecyclable plastics,” Deming says. “This mix definitely helps the agricultural industry.”

Within the agricultural industry, Deming flagged another pain point – how to dispose of landfill materials such as unrecyclable plastics and contaminated cardboards. Rather than creating landfill, Deming sees that these heat-producing items could be blended with swine and waste treatment sludge to solve two problems while creating electricity.

“The technology has been around in Europe for a while,” Deming says. “That is a very highly controlled, oxygencontrolled combustion, so that you get a very complete combustion.

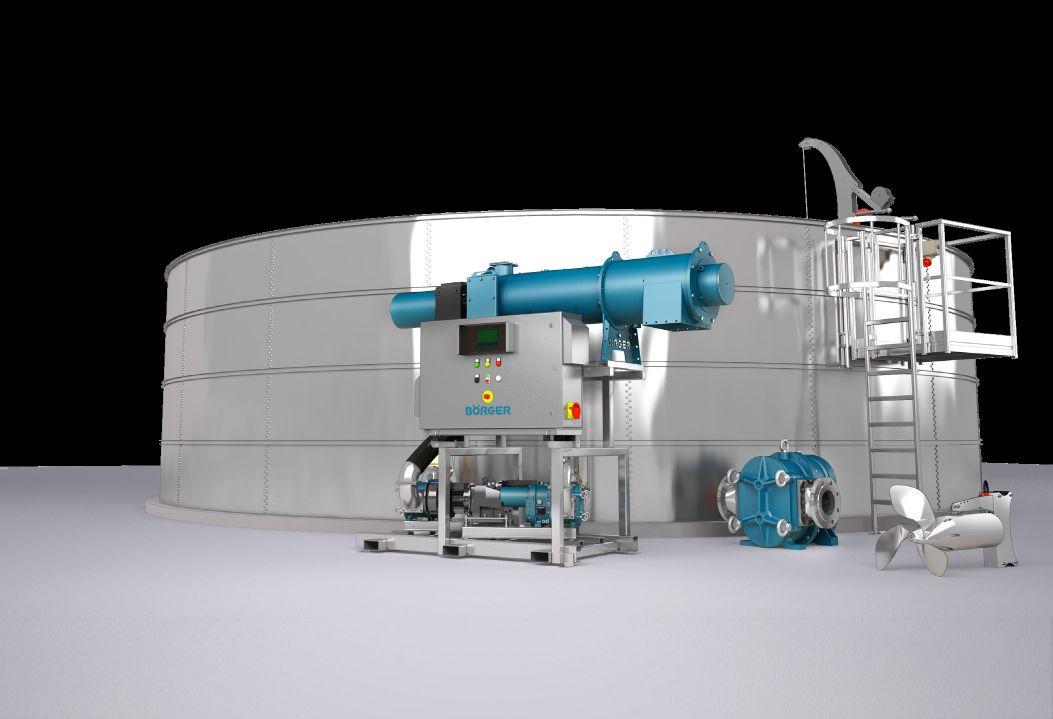

CONSISTENT NUTRIENT VALUE - AGITATION

MAKES THE DIFFERENCE

Center agitation system evenly blends nutrients

Better utilization of “waste” translates into less purchased fertilizer

ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND

Designed and constructed using bolted glass-fused-to-steel panels for secure storage and high corrosion resistance

Aboveground - minimizes the danger of run-o , leaching and groundwater contamination

Environment-friendly odor control - releases odors above ground level into higher air currents

“Now the key is continuing to improve the emission systems. You’ve got to do it right. You’ve got to blend it into a fuel, and then you’ve got to put it into an appropriate-sized facility with good emissions control. When you do that, you’ve turned a big waste problem into a great source of energy.”

PRG would rather use animal waste, but without Renewable Energy Credits, it is more difficult to sell electricity made in this manner, as there are more cost-effective alternatives. Plastics could become an affordable alternative. Since plastic is no longer sent to China to be recycled, it is causing massive issues. Recycling systems are failing all across the United States, landfills are filling up with plastics, and many companies have no landfill policies, so their plastics are ending up in warehouses – where it goes from there is anybody’s guess.

“You’ve got a good chance to control what actually comes out of a plant like ours,” Deming says. “And so, that is where I’m going to be finishing in my career – creating electricity from fuel blends that come from almost impossible to get rid of waste – like plastics, like swine sludge, and like wastewater from treatment plants.”

Until then, it’s turkey waste that will be powering Pitt County.

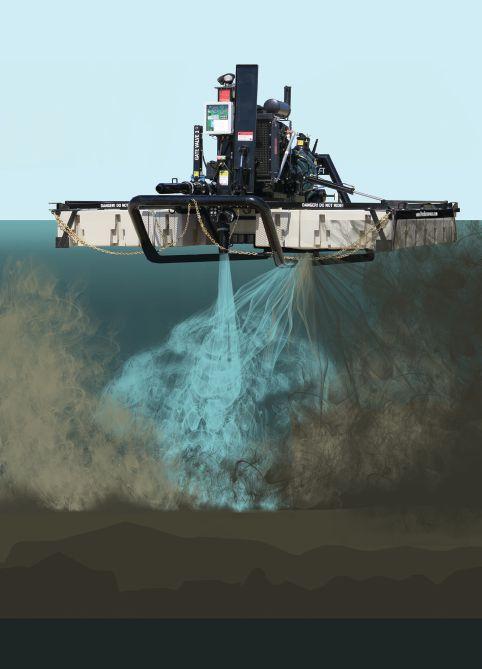

• Propeller is able to move 45 degrees either way.

• Able to slide in pump out hole at an angle to miss barn overhang.

• Easy skidloader maneuverability around buildings.

• Working depth for pits: 6-10′

Sometimes we get bogged down in the intricacies of manure and farm management. At these times, it’s refreshing to take a step back and be reminded of the basics. On-farm manure stockpiling doesn’t need to be complicated, but there are a few important things to keep in mind. Here are some things to consider when it comes to manure storage and stockpiling.

As it is in real estate, stockpiling is all about location, location, location.

The ideal stockpile location is out of the way, can be accessed with hauling equipment, and will not lead to runoff into sensitive features. A flat area, outside of areas that flood, with a non-permeable base to avoid leaching is best. And, try to be considerate of your down-wind neighbors.

Clean water from rain, roofs, or uphill areas should not be allowed to pool around or run through a manure stockpile, as any water that comes in contact with the manure will carry away pollutants.

Soil berms may be built to divert rain and uphill water, and gutters and downspouts can be added to barns and buildings to divert water.

For example, let’s say you’re a horse owner. With manure and bedding, a 1,000-pound horse can produce 60 to 70 pounds of waste per day, occupying around 2.4 cubic feet. If you have five horses that each weigh exactly 1,100 lbs., that’s 5,500 lbs. total. You haul away your manure twice per year – once in the spring and again in the fall.

You know that an average of 2.4 cubic ft. of manure is produced each day per 1,000-lb. horse. So how much space will you need for manure storage?

The formula: 2.4 cubic ft. x (5,500 lb. / 1,000 lb.) x 365 days = 4,818 cubic ft. per year

But, you haul manure twice per year, so you really only need storage for half of a year (182.5 days).

The final calculations: 2.4 cubic ft. x (5,500 lb. / 1,000 lb.) x 182.5 days = 2,409 cubic ft. needed.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

As it is in real estate, stockpiling is all about location.

Once you have the perfect location picked out, it’s time to think about what the storage area will look like. First, to determine how much space is needed, ask yourself the following questions:

• How many animals will contribute to the manure stockpile?

• How much, and what kind of bedding will be in the manure?

• How long will the stockpile remain before being hauled away?

Does this mean you should build a storage pad that is exactly 2,409 cubic feet? No. These calculations were based on averages to give you an idea of the size needed. Actual space allotted for storage should be larger than the calculated value to account for variability. For one, you will likely not haul the manure away at exactly 182.5 days, and you need to ensure that you’ll have enough storage if it is a long winter. And the actual manure and soiled bedding might vary based on the horse or bedding type.

It’s always best to err on the side of having too much space for manure, rather than cutting it close. That way, if you change bedding or add animals, you won’t need to expand your storage size. •

Chryseis Modderman is a Crops Extension Educator with a focus on manure nutrient management at the University of Minnesota. Read her previous Manure Minute columns online at www.manuremanager.com.

For Professionals with a little dirt on their boots