READY, SET, COBOT

How to deploy collaborative robots

THE ROBOTICS PIPELINE

How well is academia sharing automation R&D with industry? p.10

CAD REPORT

World Model AI is expanding to include everything p.14

LOOKING AHEAD

What will 2026 bring for Canada’s robotics sector? p.18

Hose Clamps

Spiral Rings

Disc Springs Wave

INSIDE

6 Collaborative robots

Cobots offer a quick entry into automation, and design engineers are increasingly turning to them. But there’s a right way to deploy them on the factory floor.

10 Robotic research and development

Canada has strong robotic research at top universities from coast to coast, but how efficiently is it being transmitted to the design engineers and others who can use it? 17 Microrobotics

Researchers have developed the world’s smallest fully programmable, autonomous robots.

18 Canada’s robotics sector in 2026

From delivery robots to humanoids to a possible national robotics strategy, here are some of the latest updates.

Canadian/German digital alliance, Magna deepens China footprint 14 CAD Report

The new bet on AI for MCAD

20 Idea Generator

The latest industrial products

2 2 Canadian Innovator

Tracking hockey pucks with AI

Aye, robot

When it comes to cutting-edge technology, there’s not much that can touch robotics. Integrating artificial intelligence, advanced sensors, and machine learning to create increasingly autonomous, adaptable, and dexterous systems, robotic automation is transforming industries as disparate as manufacturing, through highspeed industrial robots; healthcare, through surgical robots; logistics, through autonomous delivery; the agricultural sector, through automated harvesting, soil monitoring, and pest control; and even the extraterrestrial, where they could soon be vital to building and maintaining lunar and orbital infrastructure, and humanoid robots are edging closer to conducting actual space missions.

Speaking of the extraterrestrial, sometimes the planets align and hand us a lucky break here on Earth, and I believe this is the case for me – as the new editor of Design Engineering – and this particular issue, which will explore the growing use of robotics in the manufacturing sector. I’ve been the editor of Canadian Plastics, a sister publication to Design Engineering, for almost 20 years, and while I wouldn’t call myself an expert in engineering, I think I’ve become reasonably well-educated about robotics, which have long been used to automate tasks in plastics like machine tending, assembly, quality control, and packaging. So hopefully it makes my learning curve a little less whiplash-inducing.

The feature articles in this issue will explore some best practices for deploying collaborative robots – or cobots – in Canadian factories, and the ways in which Canadian universities are trying to connect their robotics innovations with industry for use in real-world applications. We’re only scratching the surface in this issue, of course, and I’m struck by how the challenges that remain for automation are as interesting (to me, anyway) as the successes: challenges such as the comparatively low adoption rates for robots in Canada, for example, or – as laid out in a recent University of Waterloo study – the fact that hackers can identify a robot’s action with a 97 per cent accuracy rate, exposing a major privacy weakness in cobots. But there will be time to explore these in detail in later articles in later issues, and we plan to.

It’s my hope, as I take the helm of Design Engineering, that you find the content in this issue informative and enlightening and, going forward, if you have news on interesting projects, innovative technologies or upcoming events that you’d like to share, please don’t hesitate to get in touch. I’d love to hear from you.

It’s my privilege to be here, and I look forward in succeeding issues to trying to capture as much as possible of the incredible evolution currently transforming the roles of design engineers and machine builders. |DE

MARK STEPHEN Editor mstephen@annexbusinessmedia.com

Editorial Board

DR. MARY WELLS, P.ENG Dean, Faculty of Engineering, University of Waterloo

KEVIN BAILEY CEO, Design 1st

MASSIMILIANO MORUZZI CEO, Xaba

JAYSON MYERS CEO, NGen Canada

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2026

Volume 71, No.1 design-engineering.com

READER SERVICE

Print and digital subsciption inquiries or changes, please contact Angelita Potal Tel: (416) 510-5113

Fax: (416) 510-6875

Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto ON M2H 3R1

EDITOR Mark Stephen (416) 903-8041 • mstephen@annexbusinessmedia.com

DIGITAL EDITOR Jared Dodds (437) 775-9680 • jdodds@annexbusinessmedia.com

PUBLISHER Kathryn Swan (647) 339-4880 • kswan@annexbusinessmedia.com

ACCOUNT COORDINATOR Cheryl Fisher (416) 510-5194 • cfisher@annexbusinessmedia.com

GROUP PUBLISHER Paul Grossinger (416) 510-5240 • pgrossinger@annexbusinessmedia.com

AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Beata Olechnowicz (416) 510-5182 • bolechnowicz@annexbusinessmedia.com

CEO Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

Design Engineering, established in 1955, is published by Annex Business Media, 5 times per year except for occasional combined, expanded or premium issues, which count as two subscription issues.

Printed in Canada

Publications Mail Agreement #40065710 ISSN: 0011-9342 (Print), 1929-6452 (Online)

Subscriber Services: Canada: $61.00 for 1 year; $98.12 for 2 years; Outside Canada: USA - $149.04; Overseas - $160.18; $10.00 for single copy.

All prices in CAD funds.

Add applicable taxes to Canadian rates.

From time to time we make our subscription list available to select companies and organizations whose product or service may interest you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Business Media Privacy Officer: privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission.

©2026 Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. DE receives unsolicited features and materials (including letters to the editor) from time to time. DE, its affiliates and assignees may use, reproduce, publish, re-publish, distribute, store and archive such submissions in whole or in part in any form or medium whatsoever, without compensation of any sort. DE accepts no responsibility or liability for claims made for any product or service reported or advertised in this issue. DE is indexed in the Canadian Business Index by Micromedia Ltd., Toronto, and is available on-line in the Canadian Business & Current Affairs Database.

CANADA AND GERMANY ADVANCE DIGITAL ALLIANCE, EMPHASIZE AI

Canada and Germany have agreed to advance a Canada-Germany Digital Alliance, a partnership focused on concrete collaboration in areas of mutual interest, including ar tificial intelligence (AI), digital sovereignty, digital infrastructure, and cooperation with respect to startups and the digital economy.

Evan Solomon, minister of artificial intelligence and digital innovation and minister responsible for the Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario, met with Karsten Wildberger, German minister for digital transformation and government modernization, on the margins of the G7 Industry, Digital and Technology Minister s’ Meeting in Montreal on Dec. 8, 2025. The ministers agreed that, among the first deliverables under the Alliance, both sides would finalize a Joint Declaration of Intent (JDoI) on AI in the coming months. They highlighted the following potential areas of cooperation under the JDoI: AI adoption, with a focus on physical AI and industrial AI; building and deploying compute infrastructure; exchange on polic y development and inter-operability; research and commercialization; AI safety; development and adoption of generative AI as well as algorithmic innovation (frontier AI); talent attraction and mobility; and business engagement, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

The minister s also discussed opportunities to strengthen commercial ties and highlight investment and business opportunities that AI can bring to firms, especially small to medium-sized enterprises, in both countries.

AUTOMOTIVE MAGNA DEEPENS CHINA FOOTPRINT WITH NEW WUHU FACILITY

Bolton, Ont.-based automotive parts maker Magna International Inc. is strengthening its presence in China with a new facility in the Jiujiang Economic Development Zone,Wuhu to support the growing demand of electric drive systems.

“This expansion reflects Magna’s commitment to supporting our customer s’ electrification strategies and advancing sustainable mobility,” said Diba Ilunga, president, Magna Powertrain, in a media release. “Wuhu offers a strong industrial foundation and an environment conducive to innovation. We are excited to bring our world-class electric drive technologies closer to Chery and other par tners in China.”

The new facility will manufacture Magna’s eDrive systems, delivering smooth, high-performance electric propulsion with a scalable architecture for a wide range of battery electric vehicles (BEVs).

Magna’s newly leased facility spans over 160,000 square feet and is expected to generate approximately 200 new jobs upon reaching full production.

Over the past 20 years, Magna has accelerated its growth in China. In 2024, the company recorded US$5.6 billion in sales in the market, with approximately 60 per cent of this revenue coming from Chinese OEMs.

ROBOTICS

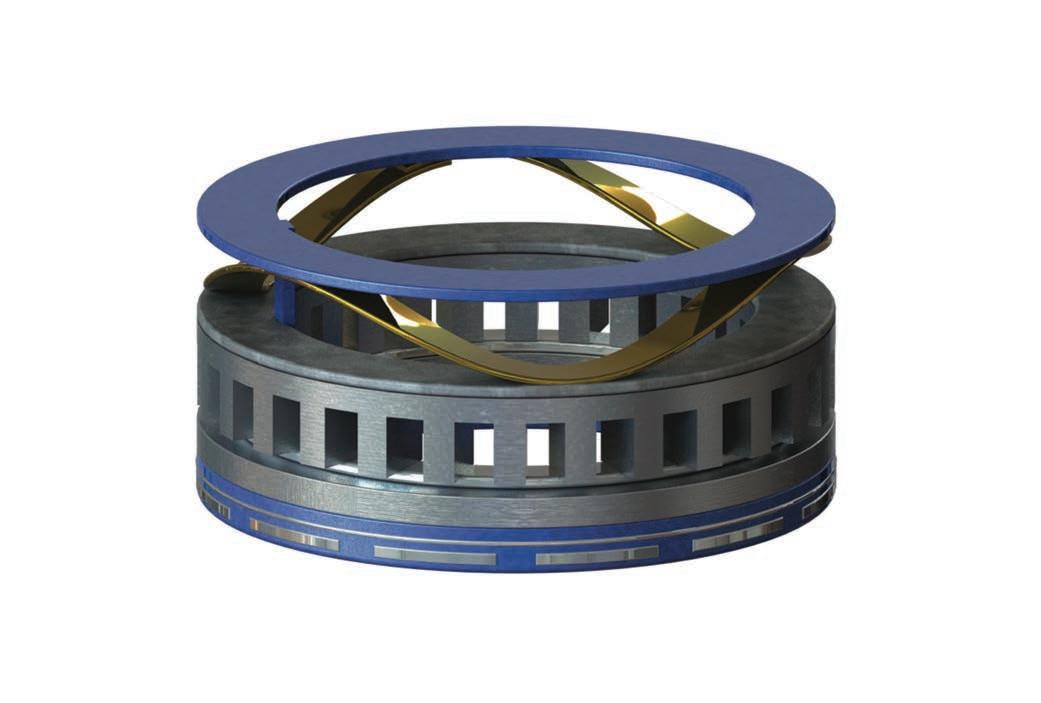

SCHAEFFLER, HUMANOID ENTER STRATEGIC TECHNOLOGY PARTNERSHIP

German manufacturer Schaeffler AG and British technology company Humanoid have formed a strateg ic partnership to develop

From left: Georg F. W. Schaeffler, family shareholder of Schaeffler AG; Artem Sokolov, CEO and founder of Humanoid; and Klaus Rosenfeld, CEO of Schaeffler AG, sealing the technology partnership.

innovative components for humanoid robots. The collaboration will focus on the development and supply of actuators used in wheeled robots and in bipedal (two-legged) humanoids.

Magna’s eDrive systems deliver smooth, highperformance electric propulsion with scalable architecture for a wide range of BEVs.

The specific deliverable is the development and supply of strain wave gear actuators, produced using several manufacturing processes including winding, surface mounting and machining technology, as well as assembly and testing technologies. Strain wave gear actuators are used primarily in the upper body, shoulders, and arms of humanoid robots, and enable complete internal cabling of actuators and extremities through their weight-to-torque ratio and large hollow shaft.

“For years, humanoid robotics has been taking place in labs, p roduct demonstrations, and ‘proof-of-concepts’, but real-life application in large volumes is the moment when the technology will truly be put to the test,” said Artem Sokolov, CEO and founder of Humanoid, in a media release.

“At Humanoid, we believe that the future of humanoid robotics will not be defined by the most impressive demonstrations but by its large-scale scalability and capacity for use in challenging real-world environments.”

Additionally, Schaeffler has committed to introducing several hundred humanoid robots into its global production network over the next five years. The goal, company officials said, is to become a prefer red technology partner in the humanoid robotics segment.

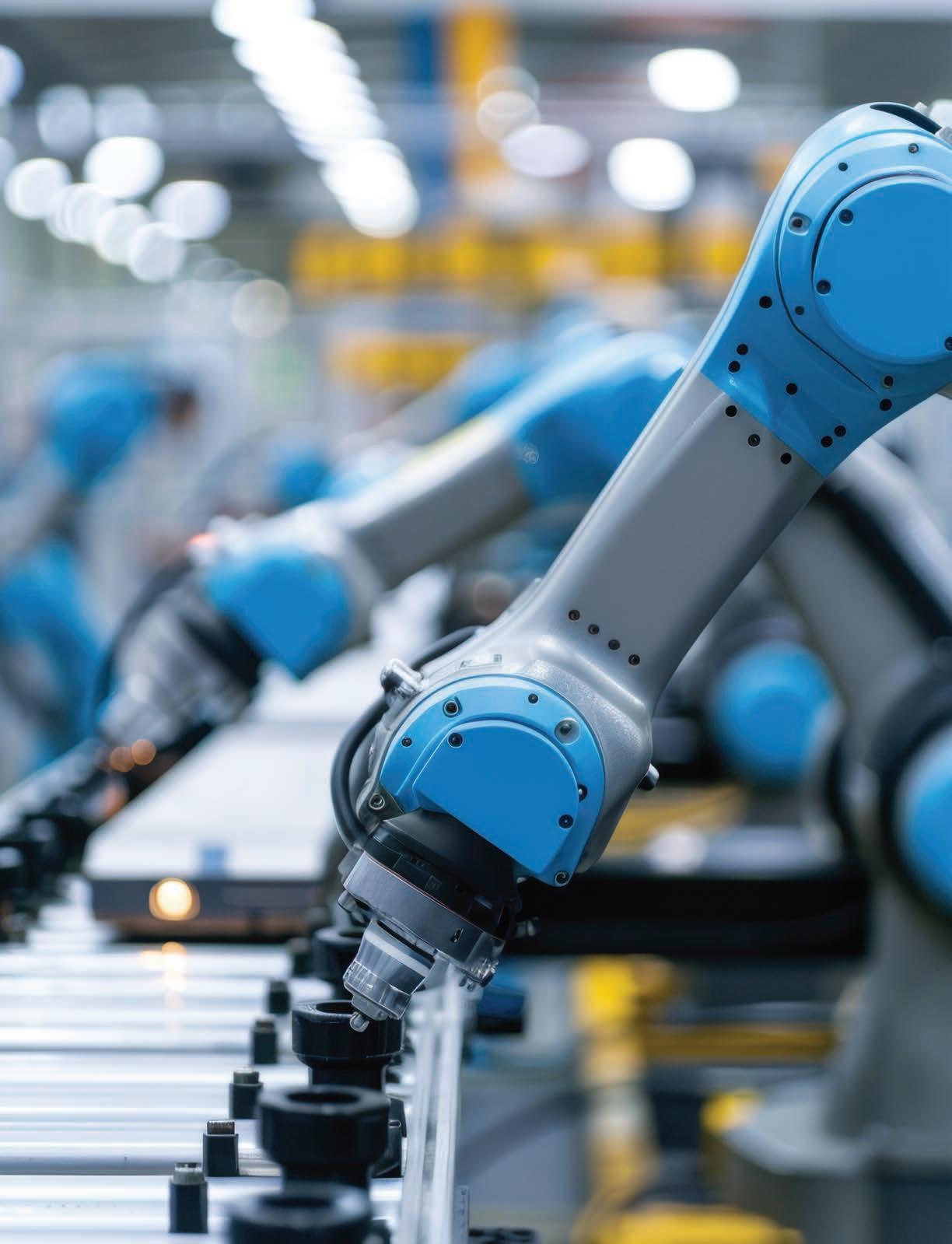

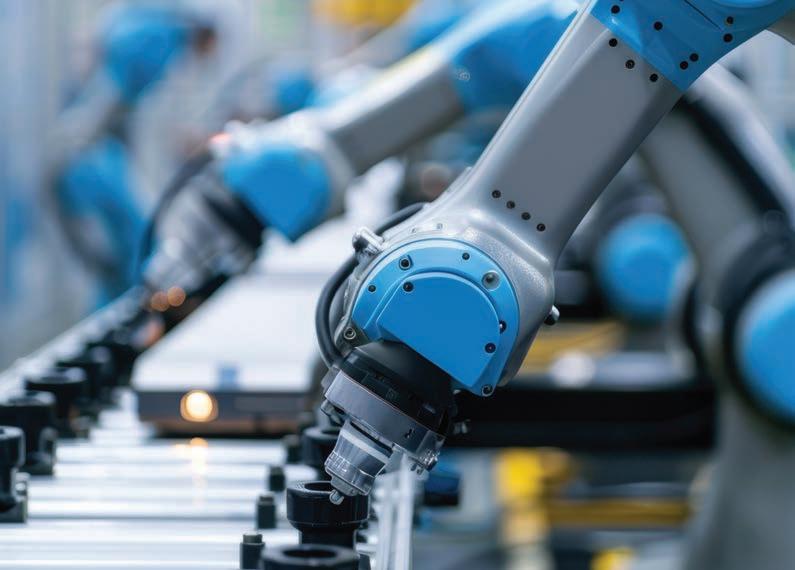

READY, SET, COBOT

Collaborative robots offer a quick entry into automation, and design engineers are increasingly turning to them. But there’s a right way to deploy them on the factory floor.

BY MARK STEPHEN

Collaborative robots – commonly known as cobots –are power- and force-limited robots that represent an important shift in manuf acturing automation. Unlike their industrial predecessors – which are typically fixed-location robots in cages performing high-volume, lowmix tasks – some cobot applications can work alongside humans, handling repetitive and ergonomically challenging duties while workers focus on quality control and complex assembly steps.

For manufacturing plants and design engineers that

haven’t used robots before, cobots offer a quick entry into automation thanks to their easy programming, usually through hand guiding or tablet interfaces. Also, cobots can sometimes allow for fenceless applications directly integrated into existing production areas; and can adapt flexibly by using plug-andplay technologies, making them attractive for companies that don’t have engineering experts, with low-volume/ high-mix manufacturing environments, and in industries where production needs are constantly changing.

And they’re ideal for

factories. But that doesn’t mean that installing and integrating them is a no-brainer. Just the opposite: success hinges on carefully choosing the right task. And for a lot of first-time users, their first instinct can be wrong. “Firsttime cobot users typically want to automate the hardest job first, but I always recommend against that,” said Mike DeGrace, solution sales and ecosystem success manager with Novi, Mich.-based Universal Robots (UR). “Instead, I recommend that cobots be used first to alleviate the hidden costs to operating a factory, like having an operator off alone in the corner folding boxes for eight hours a day.That’s a waste of money and human capital.”

In other words, cobots can’t be simply dropped into existing processes. Workflows must often be rethought to optimize human-robot collaboration, and workers retrained on safety and new ways of working that leverage each partner’s strengths. So, choosing the right tasks for a cobot involves understanding what a cobot can – and can’t – do, and then deploying it in a safe and productive fashion.

reducing errors and augmenting workforce productivity. A recent Massachusetts Institute of Technology study found that pairing humans with a collaborative application reduces idle time by 85 per cent compared to working in an all-human team.

And that last part is particularly important, as the skills shortage in manufacturing continues to put pressure on the entire economy, particularly small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). For these, cobots can help take pressure off overworked teams.

In short, cobots are a no-brainer for use in today’s

Safety first

The word “safe” might come as a surprise, since the common perception is that cobots are all safe. But that’s not true. Cobots are designed to be safe to work with due to built-in sensors, force/speed limiting, and safety-rated stops, but they aren’t safe in all applications – it depends on the payload, speed, end effector, workpieces, and workspace analysis. “From a safety and compliance standpoint, what matters is how the robot is applied and used, not what it’s called,” said Roberta Nelson Shea, global technical compliance officer at Teradyne

Robotics, in Odense, Denmark. “International safety standards such as ISO 10218 state requirements for a robot application that’s designed, assessed, and validated for safe use – regardless of whether the application is or isn’t collaborative. Canada uses Z434, which is a Canadian national adoption of the ISO 10218 Industrial robots and robot applications – Part 1 and 2 combined. The Canadian edition will be updated this year to be an adoption of the 2025 ISO 10218 series, but there’s no special standard about collaborative applications – it’s covered in ISO 10218.”

A cobot application’s safety depends entirely on its use, in other words, not on the robot itself – and the setup is only as collaborative as the most dangerous element. For these reasons, a risk assessment at the

outset is crucial and mandatory for identifying and reducing r isks in cobot applications. Key steps are identifying the risks due to pinch points, unexpected movements, and workspace intrusions; analyzing the workspace, including how it interacts with existing equipment and people; evaluating the risks, considering f actors like force, pressure, and energy; and then reducing those risks by redesigning the application, adding guards or safety devices, and having the user implement training and procedures. “Every application should have a risk assessment,” said John McCormick, president of Mississauga, Ont.-based Cobots Inc. “Things to consider are speed and operation type –packaging is typically low risk, for example, and drilling and grinding are higher risk.”

The impact of cobots is most evident in tasks that require proximity to human workers, but the assessment might determine that guarding is necessary. “If a cobot application could injure a person, then safeguarding is required,” said Roberta Nelson Shea. “It’s really only low-payload and lower speeds that are possible for cobots without safeguarding.” And obviously, it’s better to make that determination sooner rather than later. “You want to avoid going through the procurement process expecting to have a cobot shoulder to shoulder with human workers, only to find out during installation that you need to close off the area with guarding,” said Jasper Arthur, a research officer with the Ottawa, Ont.-based National Research Council Canada (NRC). According to

subject-matter experts, guards or extra safeguards – such as the creation of zones to detect the presence of people – might be needed if the cobot application has tools that can injure or in settings where human movement or robot behaviour isn’t fully controlled or detected. “Applications that use sharp tools need to be guarded, but the guarding is usually less complex than for industrial robots,” said John McCormick. And for applications moving large, heavy materials, if there’s the remote possibility of even a momentary collision, then unguarded cobots aren’t a good fit.

One reason that cobots can be dangerous is that they’re getting faster and stronger. “In general, cobots are now moving as quickly as industrial robots – 2,000 to 3,000 millimeters [mm] per second

– and can handle payloads up to 50 kilograms [kg], compared to the 2.5 kg or 5 kg payload limits of the early days,” said Jerry Perez, executive director for global accounts with Royal Oak, Mich.-based Fanuc America Corp. Fanuc’s CR-35iB cobot has a payload of 35 kg or 50 kg, he noted.

Rules of thumb

Once the risk assessment has been completed and risks are addressed, successful adopters typically begin with one or two well-chosen applications that prove the value and then expand – rather than attempting to transform entire production lines. “This slower approach builds internal expertise, demonstrates return on investment [ROI], and helps overcome cultural resistance,” said Mike DeGrace. While each application is different, there are some general rules to follow for first-time cobot deployments. “Especially for first-time adopters, I would caution against replacing a bottleneck process, even if it’s highly conducive to automation,” said Jasper Arthur. “Integration can take a long time and sometimes you need to stop and fix malfunctions. The best processes to work out these kinks are typically the high-volume ones and not just-in-time.”

A good rule of thumb for first-time deployment, the subject-matter experts say, is to look for applications that combine repetitive motions that cause worker fatigue, operations requiring consistent force or torque application, high-mix/ low-volume production with frequent changeovers, quality-critical tasks benefiting from both automation and human oversight – but that don’t require decision-making from the cobot – and space-constrained areas where traditional robot cells won’t fit. And then, once the application has been identified, choose the right cobot and peripherals for the application, matching payload, reach, precision, repeatability, and options to the task.

As with everything in manufacturing, there’s a process for this. “A

new customer should walk their production line and identify what they think is a good application to automate; and then bring in an expert to give an independent opinion and identify some low-hanging fruit based on cost and ROI,” said Jerry Perez. “Then, contact a vendor with specifications and they can deliver a solution for a pilot run. Once it’s been proved out in testing, consider turning it into a fulltime application and then training staff to work with, and around, the cobot.” All of which can take time, Perez noted. “If the first-time customer insists on deploying the cobot quickly – within, say, three months – a pre-engineered cell is probably the best solution,” he said. On average, a cobot typically ranges from US$35,000 to US$60,000, but the total price of a fully integrated cobot application – including tooling, software licenses, safety features, and integration costs – can run to over US$150,000 depending on the ease of integration. Which is why some OEMs offer flexible payment plans that can make a pricier model more accessible. “A typical ROI is usually measured in months instead of years,” said John McCormick. “ROI on cobots is typically much shorter since the installation is simpler and needs less guarding.”

Know the limits

And it’s equally important to understand what cobots can’t do – and it often boils down to the value of two arms versus one, with the former favouring human operators. “Single-arm finishing-type applications – painting, welding, sanding, polishing, and buffing – are being done very well by cobots today, even Class A surface finishes,” said Jerry Perez. “Human workers are better for jobs that require two hands or very fine precision detail, such as running wires through different cable trays or handling a high mixture of items for packaging coming down a single line. Industrial robots can do some of these applications, but not cost-effectively.”

that

with a collaborative application reduces idle time by 85 per cent compared to working in an all-human team.

Also, the combination of fine motor control, perception, and reasoning that almost every human comes equipped with by default is a long way from being automated. “Some of the harder jobs to automate are things like detailed inspection and correction of quality issues, or highly variable assemblies which have a general shape but differing dimensions,” said Jasper Arthur. “This is an area of research and development at the NRC, and it’s not impossible right now, but it won’t be plug-and-play. But anything involving troubleshooting, teamwork, empathy, adaptability, complex decision-making, or problem-solving are all tasks that humans still excel at.”

Implementing AI

Cobots are primarily used today as tools to aid human workers, and the human-cobot relationship is somewhat linear, with the robot mainly performing the same actions. But we can expect that to change – and for cobots to become increasingly proactive – through things like greater integration of artificial intelligence (AI), which may allow robotics in

A recent Massachusetts Institute of Technology study found

pairing humans

Photo: Teradyne Robotics

manufacturing to analyze real-time environmental data and improve their efficiency over time, predict maintenance needs before failures occur, and even learn new tasks through demonstration rather than programming. These cobots will be ideal for applications such as mater ial handling, AOI inspection, and palletizing, and could collaborate efficiently with workers without the need for physical barriers, subject-matter experts say. This development follows the larger overall trend of physical AI – where machines can make instantaneous data-based decisions – moving deeper into industrial robotics.

But if some of the outlines of AI for cobots can already be seen – with future trends pointing toward greater AI integration and expanded applications as the technology matures and costs decline – others are still unknown. “There’s a huge debate going on right now about whether industry will adopt either 100 per cent, end-to-end AI control, or a blending between traditional-method robotic control and modern AI methods,” said Mike DeGrace. “At the moment, we don’t know which way it will go.”

The human element

Given this focus on cutting-edge technology, the human element to cobot application implementation can get overlooked. Which would be a mistake, since both OEMs and subject-matter experts recommend bringing human operators into the decision-making process as much as possible, both to allay any concerns on the workers’ part about being kicked to the curb and to get additional input about the best ways to deploy the new cobots. “Involving the technicians is a big part of an effective deployment strategy,” said Jasper Arthur. “If you’re making a palletizing cobot, you should probably ask the person doing that job a lot of questions about the best way to deploy it. Also, figure out early in the process where the human workers will fit in post-automation – you can’t just use a cobot to do everything a human does but without breaks.”

So, while automation is a key to the future of manufacturing, deploying cobots in a production application is – and probably always will be – a partnership between human and machine. “The real value of a cobot is to automate 70 to 80 per cent of your application and allow the remaining 20 per cent – the difficult, intricate work that requires a high degree of dexterity – to be handled by a person,” said Mike DeGrace. “And if you can do that for one application, hopefully you can exploit commonalities and use the same structure for other applications with the same configurations with extremely minimal reteach time. It takes a paradigm shift, and the customers that have figured it out are usually amazed at the results.”

A successful first-time cobot deployment requires a strategic approach: a careful task selection focusing on ergonomically challenging, repetitive work that benefits from consistent force application; a thorough risk assessment for a safe application (collaborative or non-collaborative), choosing the cobot for the payload and reach; and training staff for smooth adoption, focusing on human-robot interaction – not job replacement – to boost efficiency and quality. But since the adoption of cobots in manufacturing has exploded over the last decade, they can now be found in almost every industry, tested out in almost every configuration imaginable. Which means design engineers don’t have to reinvent the wheel here – just get with the program. |DE

REAPING THE BENEFITS

Universal Robots recently installed a UR12e cobot welder at St. Augustine, Fla.-based Centerline Brackets, for an application of MIG welding two-inch flat bar steel brackets to produce heavy-duty supports for countertops, shelves, and shower benches. The cobot reduces weld time per bracket from about eight minutes to one minute or less, increases capacity by allowing two welders and one cobot to achieve the same output as eight welders previously, and has delivered ROI in less than three months. “Our goal was to make the process smoother and not be at the mercy of the employment pool available around here,” said Chris Smith, manag ing partner at Centerline Brackets. He added that the financial results delivered by the cobot application also gave Centerline the ability to pay employees “a good chunk more than they were making before.”

ACADEMIA AND INDUSTRY: AN “INCOMPLETE” GRADE

Canada has strong robotic research at top universities from coast to coast, but are the results getting through to industry? BY MARK STEPHEN

Research and development (R&D) plays a pivotal role in the manufacturing industry, serving as the engine that drives innovation, technological advancement, and overall progress. Without exposure to the many streams of outside R&D, even companies with the best in-house design engineers can struggle to adapt and stay relevant.

And this conduit is especially valuable when it comes to the adoption of industrial automation in Canada, which – to put it mildly – isn’t great. Indeed, Canada’s robot density (robots per 10,000 employees) in manufacturing is lower than the U.S., Ger many, and Japan, and is ranked only 15th among the top 20 countries for industrial robotics adoption by the Inter national Federation of Robotics. And it’s a problem that plagues small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in par ticular, often due to a lack of accessible information on real-world applications and a clear understanding of the return on investment (ROI).

And it’s costing them, because robots are crucial to modern manufacturing for boosting efficiency, quality, and safety; working 24/7 to increase output; reducing errors; and performing dangerous or highly precise tasks beyond human capability. Robotic automation is the missing link between the information age and key sectors

of the physical economy, from manufacturing and extractive industries to agriculture, logistics, and health.

It doesn’t have to be this way, however, since Canada has strong robotic research at top universities from coast to coast, including the University of Waterloo (U of W)’s RoboHub robotics research facility, the University of Toronto (U of T)’s Robotics Institute, the Offroad R obotics interdisciplinary field robotics research group at Queen’s University, the robotics department at the University of Alberta, the University of British Columbia’s Robotics and Control Laborator y, Dalhousie University’s student-led Combat Robotics Team, and many more. These universities offer broad expertise, from fundamental artificial intelligence

(AI)/control to applied areas including industrial automation.

And standing atop it all is the Canadian Robotics Council (CRC), a non-profit that brings together leading robotics experts from across research, government, and industry.

The presence of strong university research institutions can attract private investment and support the creation of local innovation clusters and research parks, which in turn drives regional economic development and job creation. That’s the theory, at least. But is the pipeline between the academic researchers and potential end users in industry as open and free-flowing as it could be or should be? An honest grade, the subject-matter exper ts say, would probably be an “I” for “Incomplete.”

“There’s not a good mechanism yet for widespread flow of information between industry and academia, but it’s getting better,” said Brandon DeHart, the manager of RoboHub and an adjunct assistant professor at U of W. “The CRC is getting there, but it’s only a few years old. We’re not at the point yet where there are good channels outside of dedicated organizations, and we still lack a pool of common knowledge.”

The Swiss Army knife

The RoboHub’s main showcase facility was established in 2018 with the goal of enabling researchers, industry par tners, and students alike to develop and deploy heterogeneous robot teams and simulate complex, real-world environments. To support academic and industry projects, the facility has dedicated

The RoboHub’s main showcase facility at the University of Waterloo.

Photo: University of Waterloo/RoboHub

infrastructure including an advanced 360-degree 3D indoor positioning system, a control centre for effective fleet management and visualization, and switchable privacy glass for confidentiality. RoboHub’s sectors of application include manufacturing and processing , aerospace and satellites, automotive, agriculture, construction – including building, civil engineering, and specialty trades – defence and security industries, education, and healthcare and social services.

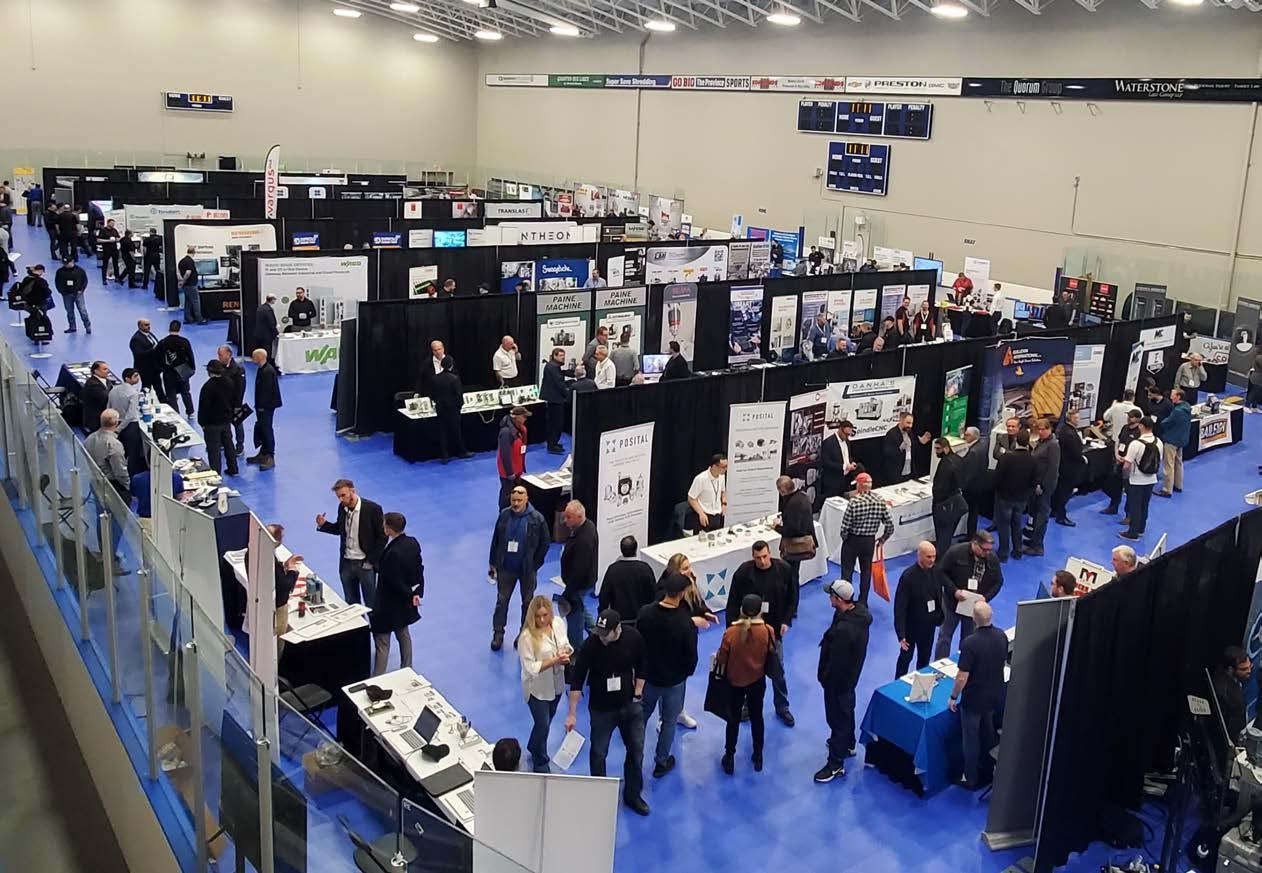

DeHart describes RoboHub as the “Swiss Army knife” of robotics and automation R&D in Canada – highly versatile, multi-functional, and adaptable to work with industr ial collaborators and disseminate the latest innovations to industry at large. “We have a very diverse group of researchers who are at the forefront of international robotics research, and we have a variety of ways of connecting with industry,” he said. “We run events a few times a year attended by hundreds of people to talk about the intersections between government, industry, academia, and star tups in the robotics space and adjacent spaces; we’ve done lots of projects with manufacturers – SMEs in particular – to integrate robots into their plants; we offer a partnership program, where organizations looking for automation talent or matchmaking can come to us and we can connect them to a particular solutions provider; and we launched a membership program in 2025 where professor s and independent researchers from across the country can opt in and pay a low fee to get the same access to the RoboHub and its resources as the professors on campus do.”

According to DeHart,

conferences are among the most effective tools for opening the pipeline between research and industry at present. “The conversations between industry and academics and government at our conferences usually end up seeding dozens of projects and collaborations,” he said. “We’re playing ‘matchmaker,’ and these events are one of the primary mechanisms for getting research commercialized in established companies.The other mechanism is through engineering students, such as those in the mechatronics program, who work on robotics design teams, enter robotics competitions, and create startups which grow into massive companies – like Clearpath Robotics, which was acquired by Rockwell Automation – thanks to our inventor-owned IP policy.”

Companies usually want RoboHub’s help with integration, DeHart said, often on the quality assurance/quality control side and especially for machine tending solutions –applications where robots are being modified and trained to suit the environment they’re put into, which was built for humans to work in. “We also do a lot of vision systems and machine learning development,” he said. But there’s a limit to what RoboHub can deliver, based primarily around timelines. “We don’t work on developing core automation hardware because that leads to situations where an SME wants large-scale delivery of 100 or more units, and we don’t have the time or resources for that,” DeHart said. “We prefer buying a smaller robot and adapting it for the collaborator’s needs by adding some code or adding an end effector to create a proof of concept in the human-centric space – in general, we’re looking at smaller scale robot arms

that are either tabletop or mounted on a mobile system.”

Outreach initiatives

The U of T’s Robotics Institute is home to a large and diversified robotics research program, and among its activities it runs the annual Toronto Robotics Conference to showcase some of the latest projects by its students. The 2025 show, held at the school’s Mississauga, Ontario campus, displayed the latest AI-robotics research and drew more than 300 researchers, students, and industry partners. The conference featured talks from industry experts and researchers, and showcased graduate student work, including surgical robots that wielded metal-tipped arms with the guidance of cameras; a robot built from 3D-printed, stackable segments that link together to form a flexible spine, that’s designed to inspect the narrow interior of an aircraft wing; and a voice-controlled robotic rover built for rugged terrain that could have applications in fields ranging from agriculture to space exploration.

Important outreach efforts undertaken recently by the CRC,

meanwhile, include a new case study library, which will serve as a publicly accessible resource that showcases successful robot deployments across various sectors.

“Our goal is to de-risk technology investments for Canadian SMEs by providing clear, measurable examples of how robotics can make a positive impact and generate clear ROI,” CRC officials said. Also, the CRC is advocating for a national Canadian robotics strategy – a coordinated effort, headed by the federal government, to support manufacturing organizations throughout the adoption process.

At a time when Canada’s productivity is falling behind while other countries are embracing automation, this idea has gained traction, especially given the emergence of Canadian strategies in other critical technology areas such as AI, and quantum science and technology. “Australia, the United States, China, and the European Union are among the regions that have launched new robotics strategies or renewed existing frameworks,” said Hallie Siegel, CEO of the CRC. “This means increased competition but could also pave

the way for new partnerships for robotics stakeholders in Canada.”

Pushing for a national strategy

A June 2025 paper by Daniel Araya and Peter Suma summarized the problem, noting that Canada lacks focused industrial execution for robotics development and deployment. “The hard reality is that Canadians need to get serious about long-ter m strategy,” they said. Araya and Suma propose robot clusters that include an industrial robotics hub in Ontario’s Toronto-Waterloo corridor, AI-driven robotics and healthcare robotics in Montreal, humanoid and service robotics in Vancouver, agricultural and resource extraction robotics in the Prairies, and ocean robotics in Atlantic Canada. “These clusters would concentrate talent, investment, and infrastructure, creating dynamic innovation ecosystems that continually generate new companies,” they said.

By contrast, as we’ve seen, Canada currently has a decentralized ecosystem of programs, clusters, and other agencies to promote robotics adoption in the manufacturing sector, and they tend to offer piecemeal initiatives. A national

Aoran Jiao, a U of T graduate student, let conference-goers test drive a voice-controlled robotic rover at the 2025 Toronto Robotics Conference.

The CRC’s new case study library is designed to de-risk automation by demonstrating how robotics deployment can yield a measurable ROI to organizations in a range of critical sectors.

Photos: Nick Iwanyshyn/University of Toronto Mississauga; Canadian Robotics Council

strategy, on the other hand, would offer an organized approach to leveraging Canada’s growing robotics talent pipeline by accelerating commercialization of university research, spinoffs, and startups, and then encouraging more companies at all scales to adopt Canadian robotics technology.

There is, as Hallie Siegel noted, ample precedent for this, with perhaps the best model being Denmark, one of the most digitized and automated nations in the world. In his keynote address at the CRC’s third annual symposium in Toronto in June 2024, Søren Elmer Kristensen, CEO of Odense Robotics, explained that collaboration between academia, industry, a trade union, and local government was critical to the success of Denmark’s robotics cluster. Located in Odense, this world-leading cluster has grown over two decades to include over 500 firms that employ 12,700 people. This collaborative model is also advocated by the CRC.

A failure to communicate

But is Canada ready for this level of academia/industry collaboration? The answer is yes, the subject-matter experts say, but with a language-related asterisk. “The problem is having shared goals without having a shared, common language,” Brandon DeHart said. “Academia and industry don’t talk the same way – they use very different jargon to describe the same things, which creates confusion.” And the disconnect goes deeper than that, he continued. “Even among robot academia, there’s still no consensus on what to call different types of robots and how to describe them – we don’t have a good classification among ourselves of the hardware, let alone the software and what it’s capable of, so how can we communicate effectively with industry about our research?” he said. “We have to do better at translating what one side is saying to the other, and what we’re saying to each other.” As a concrete example, DeHart points to last year’s Humanoids 2025 conference held in Seoul, South Korea. “The conference had relevant mobile manipulators and other industrial robot technologies on display, but companies that go to other robotics shows didn’t attend this one because the title is ‘Humanoids,’

which doesn’t interest them,” he said. “So even naming conferences properly needs some work.”

Ultimately, university research –particularly basic and applied R&D –often leads to breakthrough advances and radical innovations that have both immediate commercial applications and also form the foundation for new industrial products and even entirely new sectors. And this definitely includes industrial automation. This

r esearch is the engine for growth, giving manufacturing firms access to cutting-edge automation knowledge and technologies – including AI-driven processes – to help them innovate, streamline operations, and remain competitive and stay profitable in a dynamic global landscape. Fully opening the pipeline between academia and industr y, including through direct collaboration and knowledge spillover, can turbo-charge that engine. |DE

The New $8-Billion Bet on AI for MCAD

World Model AI is expanding to include everything – so its financial supporters hope. BY

RALPH GRABOWSKI

With talk swirling of an LLM-based AI financial bubble collapse, perhaps as soon as this year, investors are looking at different kinds of AI. “These [LLM] systems can never truly understand the world, because they can’t move through it,” says Patrick Vanbrabandt of Carya.

Last year, two companies announced they are spending eight billion dollars to model reality with World Model AI. This is a form of AI that is trained to understand how the real world works, such as through physics and in 3D spaces.

World Model AI is best known for training self-driving cars, which need to be taught what can be driven on, and what must be driven around. Now World Model AI is expanding to include everything – so its financial supporters hope.

Project Prometheus

Six billion dollars of the new funding went into a new CAD/CAM company, nicknamed Project Prometheus. The New York Times newspaper was first to describe it, saying “The company is focusing on AI that will help in engineering and manufacturing in a number of fields, including computers, aerospace, and automobiles.” The company is cochaired and co-funded by Jeff Bezos, the former CEO of Amazon.

Sadly, that’s all we know, other than its tagline, “AI For the Physical Economy.” The company remains silent. Still, we can piece Prometheus together from sources like employees hired and other areas in which Bezos is involved.

From their biographies on LinkedIn, we know that most of the 100 employees are from AI fields, such as autonomous intelligence and neural networks. A very few are in CAD-related fields, such as real-time simulation

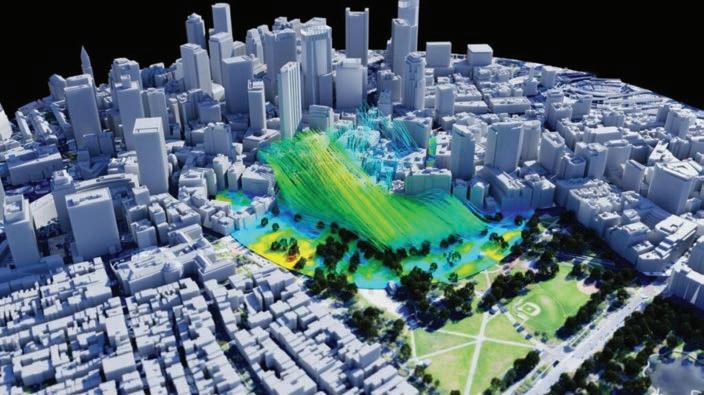

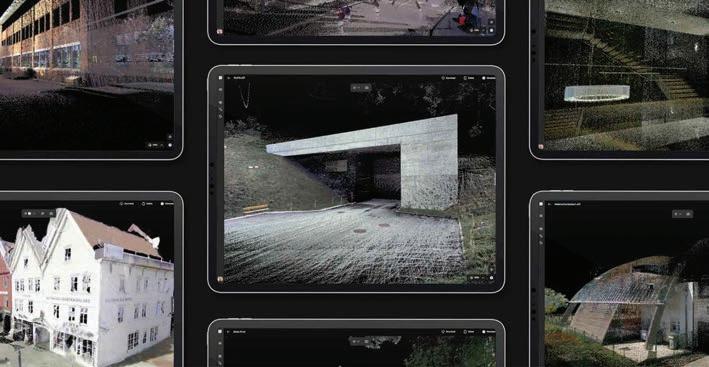

Omniverse displaying SimScale’s CFD-generated wind simulation.

Hexagon’s reality capture recording physical structures.

of industrial particulate flows. More are needed: co-founder William Guss made a public appeal on Twitter (X) for “Anyone in manufacturing and builds real things. Really trying to understand the space and see some factories :).”

The other hint comes from Bezos’s involvement in manufacturing

companies: Blue Origin’s reusable rockets and Slate’s low-cost electric trucks. My conclusion is that Prometheus wants to build an in-house CAD/CAM system assisted by a form of AI that understands the physical world to drive down development and manufacturing costs of products.

Photos: Simscale; Hexagon

Nvidia and Synopsys

Last December, Nvidia copied Bezos by buying US$2 billion worth of Synopsys shares, the biggest electronic design fir m – and new owner of simulation stalwart Ansys. Patrick Moorhead of Moore Insights says, “The partnership is a big tell for where AI likely goes next: engineering, simulation, and digital twins.”

A multi-year agreement places Nvidia’s CUDA, Agentic AI, and Omniverse into Synopsys software. CUDA is the programming interface for Nvidia’s graphics boards (GPUs), short for Compute Unified Device Architecture. GPUs are used for

accelerating everything from games, to CAD, to crypto currency mining, and now for AI by running dozens or thousands of strands of programming code in parallel.

AI chatbots, like ChatGPT, handle a single prompt (question) at a time. Agentic AI works on multi-step problems. Agents are seen as a next stage in AI helping users, but come up against blockages, such as needing permission (like passwords) to access data and handling difficult-to-navigate websites. For this reason, the AI industry in December endorsed MCP [model context protocol] to “tell AI models which external tools, data sources, and workflows they’re able to access, then allow them to connect and perform tasks,” says AI reporter Hayden Field.

Omniverse is APIs [application programming interfaces] and SDKs [software development kits]. CAD vendors use

it to illustrate real-time effects in massive models. For instance, SimScale deploys it to combine cityscapes with wind simulations generated by its CFD [computation fluid dynamics] software.

Hexagon ADAS

It turns out, however, that World Model AI is not all that new. Hexagon of Sweden has worked on it for close to a decade in its ADAS [advanced

driver-assistance system] program. Hexagon’s reality capture software records physical structures along roads as 3D point clouds. Then its Virtual Test Drive software simulates vehicles driving on the roads, taking into account the 3D model, vehicle software and hardware, and the driver.

Hexagon is committed to its virtual test drive software, updating it for the desktop and porting it to the cloud.

Process improvement is increasing efficiency whilst ensuring compliance.

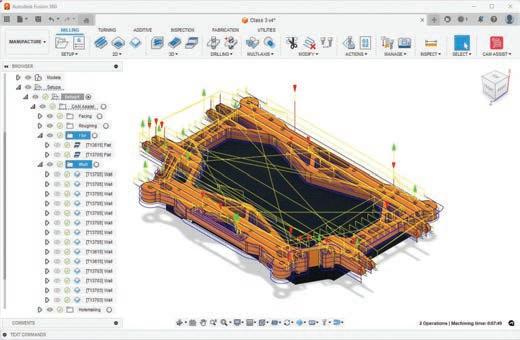

World Model AI In MCAD MCAD systems, both old and new, boast of AI to stay relevant. Legacy MCAD vendors like Dassault Systemes and Autodesk state they’ve been working on AI for a decade already, but their reference point is generative design, which a decade ago they didn’t call “AI.”

AI in legacy MCAD systems tends to be chatbots that implement shortcuts: ask one question and get one answer. A common scenario is asking the chatbot to render a scene with specific parameters; it’s a shortcut to tracking down commands – like a search engine. Sometimes, there is no solution, because the chatbot hasn’t been programmed with the answer yet, a sign that we might not be dealing with artificial intelligence after all.

Autodesk says it has lots of AI in its Fusion design package, but further reading reveals that its AI tends to be automation – replacing many steps with one, such as automating tool paths, automating drawings, and automating fastener replacements.

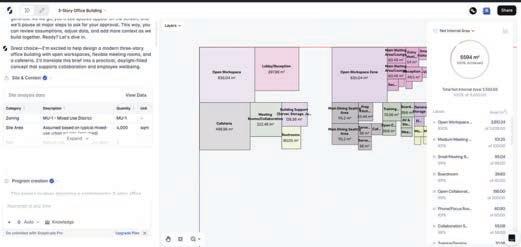

The one firm I found furthest along is an architectural one, Snaptrude. With it, you enter a one-line prompt, such as “Design a three-story office building with open workspace, meeting rooms, and cafeteria,” and then it spends ten minutes generating and optimizing an initial room layout that meets the specs of building codes –happily chattering to you as it carries out the determinations.

Conclusion

The closest MCAD comes to World Model AI is with digital twins, where the CAD model is a replica of what will be built and has been built. It lets designers run simulations and optimizations on products like expresso machines and airplanes before building them. Adding AI could help identify problems designers might not have noticed. The caution for us is that LLM-based AI can have a 30 per cent failure rate by returning hallucinations – information that it makes up.

Just like it is concerning that unexperienced engineers could access simulation software early in the design process, the same caution ought to apply to blackbox AI assisting designers. |DE

ROBOTS GO MICROSCOPIC

Researchers

have

developed the world’s smallest fully programmable, autonomous robots.

BY MARK STEPHEN

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan have just made a huge breakthrough in robotics by going incredibly small.

The research team has created what’s being called the world’s smallest fully programmable, autonomous robots: microscopic swimming machines – smaller than a g rain of salt and barely visible to the naked eye – that can independently sense and respond to their surroundings, operate for months, and cost just a penny each to manufacture. This marks the first time engineers have successfully miniaturized a complete autonomous robot below the one-millimeter threshold that’s stumped the field for decades.

Measuring about 200 by 300 by 50 micrometers and operating at the scale of many biological microorganisms, the robots could advance medicine by monitoring the health of individual cells and manufacturing by helping construct microscale devices.

Powered by light, the cellscale robots carry microscopic computers and can sense their environment and local temperatures. They can be programmed to move in complex patterns and adjust their paths by independent decision-making without magnetic or ultrasonic control systems. Each device can travel its own body length in one second; and the robots have electronic sensors that can detect the temperature

A microrobot, fully integrated with sensors and a computer, small enough to balance on the ridge of a fingerprint.

to within a third of a degree Celsius, which lets them move towards areas of increasing temperature, or repor t the temperature –which is a proxy for cellular activity – thereby allowing them to monitor the health of individual cells.

Propulsion problem

A problem the research team had to overcome involved the robot’s propulsion. Strategies that move larger robots, like limbs, rarely succeed at the microscale, so the team had to design an entirely new propulsion system, one that worked with – instead of against – the unique physics of locomotion in the microscopic realm. Instead of flexing their bodies, the new robots generate an electrical field that nudges ions in the surrounding solution. Those ions, in turn, push on nearby water molecules, animating

the water around the robot’s body. The robots can adjust the electrical field that causes the effect, allowing them to move in complex patterns and even travel in coordinated groups, similar to a school of fish.

Each robot carries a complete computer running on just 75 nanowatts – less than 1/100,000th of a smartwatch’s power consumption – and future versions of the robots could store more complex programs, move faster, integrate new

sensors, and operate in more challenging environments, the researchers say. “This is really just the first chapter,” said team member Marc Miskin, assistant professor in electrical and systems engineering at Penn Engineering. “We’ve shown that you can put a brain, a sensor, and a motor into something almost too small to see, and have it survive and work for months. Once you have that foundation, you can layer on all kinds of intelligence and functionality.” |DE

CANADA’S ROBOTICS SECTOR: 2026 PROMISES MORE EXCITING DEVELOPMENTS

From delivery robots to humanoids to a possible national robotics strategy, here are some of the latest updates.

The robotic revolution is heating up worldwide, and Canada is maintaining a mighty position relative to its size in this industry sector. Let’s jump right in for the latest updates.

Among recent, exciting developments is Magna International’s pilot testing of a delivery robot in Toronto for five months in 2025. Some technical difficulties were reported, as can be expected, but overall the trial went well. However, it’s humanoid robots that will gain most of the attention in this sector during 2026 in Canada and beyond.

Peter King, owner of Nepean, Ont.-based Cypher Robotics and vice president of its sister company Indro Robotics, predicts a continued focus in the Canadian – and global – robotics sector in 2026 on development of mobility and dexterity across the entire spectrum of humanoid robot applications. “At Indro, we will continue to apply existing, validated, and safe technologies and new innovations to these robot forms,” he says. “It’s still pretty early for industrial applications, we’re in the exploratory phase for that, but we know there’s a huge demand for more dexterous and mobile robots in industrial settings, for jobs that many people don’t want and are very hard to hire for.”

King also points to a number of new Canadian startups that have emerged in this subsector, such as Sarcomere Dynamics in Ontario. Sarcomere offers the ARTUS Lite robotic hand, a plugand-play agnostic technology that can be used in many applications.

More startup news comes from Cambridge, Ont.-based Axibo. Its three founders began at McMaster University and built a groundbreaking

BY TREENA HEIN

autonomous shuttle there. They then founded a successful cinema robotics company, working with Netflix and other players. In late 2025, the firm achieved an C$11-million funding round to launch Axibo AI, which is focused on building advanced humanoid robots

West coast leadership

Vancouver’s Sanctuary AI has long been out front in the humanoid robotic sector and its achievements continue.

CEO James Wells explains that in 2025, the importance of dexterity in creating general purpose robotics that serve practical use in the real world was realized, as were the challenges associated with creating industrial-grade robotic hands. “In 2026, I expect greater

urgenc y to be placed on addressing the challenge of industrial dexterity and for companies focused on dexterity-driven physical AI to step into the spotlight,” he says.

Sanctuary AI recently integrated new tactile sensor technology into its Phoenix robots to help pilots teleoperate these units with more precision and accurac y. In addition, in the use of its proprietary Reinforcement Learning approach, Sanctuary AI has also recently achieved an unprecedented feat. Inhand reor ientation was achieved under an extreme disturbance – a 500 gram load that was not encountered during training. Co-founder and CTPO Olivia Norton describes this achievement as “the first of its kind and a significant milestone.”

Sanctuary AI recently integrated new tactile sensor technology into its Phoenix robots to help pilots teleoperate these units with more precision and accuracy.

Photo: Sanctuary AI

Government funding, and collaboration

King also notes that many are celebrating the new, large boosts in defence spending by the federal government. “It has a pretty big funnel effect into robotics innovation,” says King.

He adds that “organizations such as the Canadian Robotics Council (CRC) and the Canadian AgRobotics Working groups are showing strong growth while working to enhance collaboration in this sector and helping startups identify problems that can be solved with robotics, with strong interest from the industrial communities.”

The CRC viewpoint

CRC CEO Hallie Siegel is pleased to report that Canada’s policy window is finally opening for robotics to scale beyond its traditional niche space applications. “With the establishment of the federal Ministry of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Innovation, we now have a clear mandate to prioritize digital sovereignty and the modernization of our hard infrastructure,” she has stated. “Minister Solomon’s focus on ‘Sovereign Compute’ and the defence budget’s alignment with NATO’s two per cent target are creating a ‘Buy Canadian’ roadmap with real teeth for our domestic innovators.”

Siegel notes that the procurement cycle is a challenge, however. While digital AI is sweeping through IT and finance, physical AI (robotics) is still largely confined to a few manufacturing sub-sectors, leaving food and beverage manufacturing, construction, and general log istics largely untapped. This is a massive, missed opportunity for the national economy, in Siegel’s view.

During the year ahead, CRC plans to codify a national robotics strategy through Sector Intelligence (Siegel notes that, unlike many of our peer nations, Canada does not yet have a unified strategy for robotics).

She and her colleagues will also focus on achieving ecosystem readiness for ROSCon 2026 Toronto in September, which Siegel describes as “a unique opportunity to showcase Canadian robotics and physical AI to the international community.” |DE

FLUID HUMANOID MOVEMENT

One thorny issue with humanoid robotics is achieving more natural and fluid movement. “Soft” robots differ from “hard” robots in that they’re pliable and flexible, making them safer. However, the materials currently used for components enabling their movement aren’t strong enough to be effective.

This is why an international team led by researchers at the University of Waterloo has developed new material that can be used as flexible “artificial muscles.” They’ve discovered how to dramatically strengthen smart, rubber-like materials by mixing liquid crystals (LCs) – commonly found in displays for electronics and sensors – into promising “soft robot” building blocks, known as liquid crystal elastomers (LCEs). The material is stiffer than traditional LCEs and display higher work density than typical human muscles. The team recently published a paper “Stiffening Liquid Crystal Elastomers with Liquid Crystal Inclusions” in Advanced Materials.

The next step for the team is to develop the new materials for use in 3D printers to create the actual artificial muscles.

BUILDING INDUSTRIAL METAVERSE ENVIRONMENTS AT SCALE

Siemens recently introduced Digital Twin Composer, a software solution that builds industrial metaverse environments at scale, empowering organizations to apply industrial AI, simulation, and real-time physical data to make decisions virtually, at speed and at scale. It combines 2D and 3D digital twin data from Siemens’ comprehensive digital twin with physical real-time information in a managed and secure real-time photorealistic visual scene, to provide contextualized insights and intelligence that allows users to visualize, interact with, and iterate on any product, process or factory in its real-world context before physical design or construction.

ROBOTIC PLATFORM FOR PHYSICAL AI

Edge AI hardware provider Lanner Electronics has launched the EAI-I351, a robotic platform engineered for the next era of physical AI. Built on Nvidia’s Jetson Thor system-on-module (SoM), the EAI-I351 is designed to deliver server-class performance for autonomous mobile robots (AMRs), heavy-duty industrial vehicles, and edge-native generative AI applications. The platform is fully optimized for Nvidia AI software stack, including Nvidia Isaac for robotics simulation and deployment, Nvidia Metropolis for vision AI, and Nvidia Holoscan for real-time sensor processing. It also supports agentic AI workflows, such as Video Search and Summarization (VSS) using Nvidia Cosmos Reason.

COMPACT, HIGH-TORQUE JOINTS FOR ROBOTIC APPLICATIONS

Electromate Inc. has introduced the maxon HEJ 90 high-efficiency joint, an integrated actuator designed for high-torque joints in mobile and legged robotic systems. The HEJ 90 combines a brushless motor, precision gearbox, encoder, servo drive, and thermal monitoring into a sealed joint assembly, to reduce system complexity while delivering high torque density and energy efficiency for battery-powered robots. With efficiencies reaching 86 per cent, the joint minimizes power losses and heat generation, extending the operating time of autonomous mobile platforms. The joint’s footprint of 110 millimeters (mm) diameter and 90 mm length makes it suitable for space-constrained designs.

STEEL INTERNAL GEARS FOR HIGH-PERFORMANCE POWER TRANSMISSION

KHK USA Inc. is expanding its line of precision gear solutions for demanding industrial applications with its SI internal gears. Manufactured from S45C carbon steel and with a precision grade of JIS N8, the gears ensure smooth and reliable operation, making them an excellent choice for planetary gear drives, robotics, automation equipment, and other high-performance machinery. And the SI internal gears are offered in a wide range of modules from 0.5 to 3, and tooth counts from 50 to 200, allowing engineers and designers to select the optimal size for their specific requirements.

MOISTURE SENSOR FOR SUSTAINABLE MANUFACTURING

By providing continuous, real-time, non-contact moisture measurement, the new IR-3000 series moisture sensor from MoistTech Corp. allows production lines to operate at maximum efficiency without the energy-intensive pauses of traditional lab testing. The sensor’s instant feedback capability empowers operators to fine-tune

drying and heating processes on the spot, allowing manufacturers to minimize over-drying, conserve natural resources, and significantly lower operating costs while maintaining top-tier product quality. Pre-calibrated at the factory and engineered with robust materials, it performs reliably even in harsh industrial environments, reducing both maintenance-related resource use and overall equipment footprint.

WATERTIGHT SEALING SYSTEM

Designed for sealing box culverts, manholes, concrete chambers, and vault structures, Denso Inc.’s new Viscotaq precast sealing system is meant to deliver a completely watertight, flexible seal that stops liquid, gas, and contaminant infiltration. The system comprises Denso’s Viscotaq line, a visco-elastic, non-shrinking coating which includes ViscoMatic, ViscoSealant, and ViscoWrap (or optionally Viscotaq EZ Wrap). Viscotaq materials are inherently self-healing, and the system requires minimal surface preparation, adheres instantly without primer, and adapts to any size or configuration. And Viscotaq materials are inert, UV-resistant, and non-toxic; and resistant to harsh soils, freeze–thaw cycling, and a wide range of temperatures.

FUTURE-READY INTERFACE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEVICES

Hilscher has introduced the new embedded module comX 90, a future-ready communication interface for industrial devices. Based on Hilscher’s netX 90 communication controller, the module combines powerful multiprotocol communication, integrated security functions, and IIoT capability in a compact form, while minimizing integration effort. Measuring 30 by 70 millimeters (mm), the comX 90 has the same dimen-

sions as the comX 51, making it easy to use in space-constrained devices. It also fits directly into existing solutions with an SPI host interface, with no hardware redesign required due to identical pinning.

EXPANDED DIGITAL SIMULATIONS SOLUTION

ABB has launched the ACS880 Virtual DrivePlus, a high-fidelity Software-in-theLoop (SIL) solution that allows industries to design, configure, and validate their systems virtually, reducing risks and allowing customers to develop applications long before the physical drive hardware is available. The ACS880 Virtual DrivePlus has the capacity to operate as an inverter, active rectifier, or DC/DC chopper within a virtual environment, and its simulation features allow for easy expansion and customization. By enabling accurate, hardware-free testing early in the project, it speeds up development, cuts commissioning time, and lowers costs, helping businesses bring products to market faster and more reliably.

EXPANDED POWER DISTRIBUTION TERMINAL BLOCK LINE

WAGO, the innovator of spring pressure connection technology, has expanded its TOPJOB S power distribution terminal block portfolio. The newest addition features a 4 AWG input in a 0.5-inch compact design, significantly reducing the required footprint on the DIN rail. Both the 2216 and 2016 series are UL 1059 certified and rated for 70 A/600

V applications. Additional advantages include a built-in meter-lead test port for touch-safe troubleshooting, molded conductor entry markings for easy identification, and compatibility with 2004 series TOPJOB S push-in jumper bars for scalable and flexible distribution.

VISION SOC POWERS 8K MULTI-STREAM AI

Ambarella Inc. has unveiled its new CV7 edge AI vision system-on-chip (SoC), designed to improve video analytics and image quality in a range of AI perception applications, including industrial automation, aerial drones, advanced AI-based 8K consumer products, and high-performance video conferencing devices. The CV7 can also be utilized for multi-stream automotive designs – especially those running CNNs and transformer-based networks at the edge –such as AI vision gateways and hubs in fleet video telematics, 360-degree surround-view, and video-recording applications and passive driver assistance systems (ADAS). And compared to its predecessor, the CV7 consumes 20 per cent less power.

FESTO’S NEW UNIVERSAL ADAPTIVE GRIPPER

Festo has unveiled the HPSX universal adaptive gripper, a hygienic soft gripper designed to handle delicate, irregularly shaped, and hygiene-sensitive products. Capable of performing multiple picks per second, it’s highly corrosion-resistant; features a sanitary design; and has a high-pressure washdown rating of IP69k, which ensures it meets food safety regulations and cleanliness standards. The HPSX is available in three sizes (40 mm, 70 mm, and 100 mm) and in two-, three-, and four-finger designs. Also, nine different forms widen its application range, and it features a universal ISO50 fitting for robotic end-of-arm tooling.

Corrosion resistant

Lightweight & lead free

Simple & clean installation

Permanent / tamper resistant

Quicker assembly time and lower assembly equipment costs compared to screws and adhesives

Puck control

University of Waterloo researchers have developed AI systems that significantly improve how hockey games are watched and analyzed.

BY MARK STEPHEN

Ice hockey may not be Canada’s national religion, but it comes close. So anything that helps to improve the ways in which the fast-paced sport can be analyzed is a welcome development. And a good place to star t is by improving puck detection in televised hockey games, which has long been plagued by problems due to the puck’s small size, high speed, and frequent obstruction behind players.

But these may soon become issues of the past. Drawing on the school’s strengths in computer vision and systems design, researchers at the University of Waterloo (U of W), in Waterloo, Ontario, have developed two innovative artificial intelligence (AI) systems that significantly improve how hockey games can be analyzed using machine learning and video footage without the need for expensive equipment.

“These improvements in detection accuracy could transform how coaches, teams, and broadcasters analyze game dynamics, leading to better strategic decisions and more engaging fan experiences,” said Dr. David Clausi, a professor of systems design engineering at U of W.

An alternative to Hawk-Eye

In one study, researchers developed a model that leverages the fact that players typically keep their eyes on the puck during games to help infer its location based on body position and

Liam Salass, a U of W graduate student and a lead researcher on the AI-based PLUCC system, tests the technology while showing his hockey colours.

the direction of their gaze.

The AI-based system, called Puck Localization Using Contextual Cues (PLUCC), boosted the accuracy of puck location by 12 per cent while also reducing localization error by more than 25 per cent compared to existing technology. PLUCC uses a detection network paired with a contextual encoder that predicts the puck’s location based on players’ gaze, body position, stick placement, and other visual cues in broadcast video. Researchers expect the system to be particularly useful for smaller organizations and amateur teams by offering a low-cost alternative to much more elaborate and expensive tracking technology such as Hawk-Eye, which is a popular computer vision system that uses multiple high-speed cameras to track the 3D path of a puck or ball. “Our goal was to make puck tracking something that doesn’t require a million-dollar setup,”

said Liam Salass, a U of W graduate student who was lead author of the study. “If a coach can analyze a game using only video, that’s a big win for accessibility in sports analytics. Finding the puck in broadcast video is one of the toughest problems in sports vision, so seeing our system accurately predict its location using contextual cues was incredibly rewarding. It was like we’d given computers real game sense.” In its current form, PLUCC analyzes individual video frames, which means it can miss the puck when visual or contextual evidence is weak. Salass is now developing a version that processes full video sequences, enabling continuous inference even when the puck momentarily disappears behind players. And beyond hockey, the researchers see the system being used in sports such as lacrosse, where small, fast-moving objects are similarly difficult to track.

Do the mamba

The second study involved the development of an AI-based framework called SportMamba that improves how multiple moving players are tracked in sports videos. The model dynamically predicts player movements during games, accounting for rapid motion, blocked camera angles, and camera shifts.

Tested across soccer, basketball, and hockey footage, SportMamba outperformed existing tracking methods by up to 18 per cent in accuracy and efficiency, allowing teams and broadcasters to conduct real-time, data-driven performance analysis without the need for costly sensor systems or fixed-camera setups.

“Tracking a hockey player on a breakaway is relatively easy,” said Dr. John Zelek, also a systems design engineering professor and a director, along with Clausi, of the Vision and Image Processing Lab at U of W. “It’s much more difficult to track and differentiate players in a scrum along the boards or in front of the net. SportMamba can tackle these difficult situations and tell us, for example, who deflected the puck and scored.”

The research papers, “Ice Hockey Puck Localization Using Contextual Cues” and “SportMamba: Adaptive Non-Linear Multi-Object Tracking with State Space Models for Team Sports,” were presented last year at the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops. |DE

Photo: University of Waterloo

Langley,