Sub S criber action required, PG 19

Sub S criber action required, PG 19

Offered exclusively by E-ONE, the all-new Metro 100 is a single axle aluminum ladder with a 100’ vertical reach on a short 220” wheelbase. The 11’ jack spread allows you to easily set up in tight spaces. And, when paired with the Cyclone II aerial cab, the Metro 100 offers an impressively low 10’7” overall travel height. Designed with both the urban and suburban departments in mind, the Metro 100 is a highly maneuverable ladder that’s long on features and short on height.

Industry-leading aerial. Innovative design.

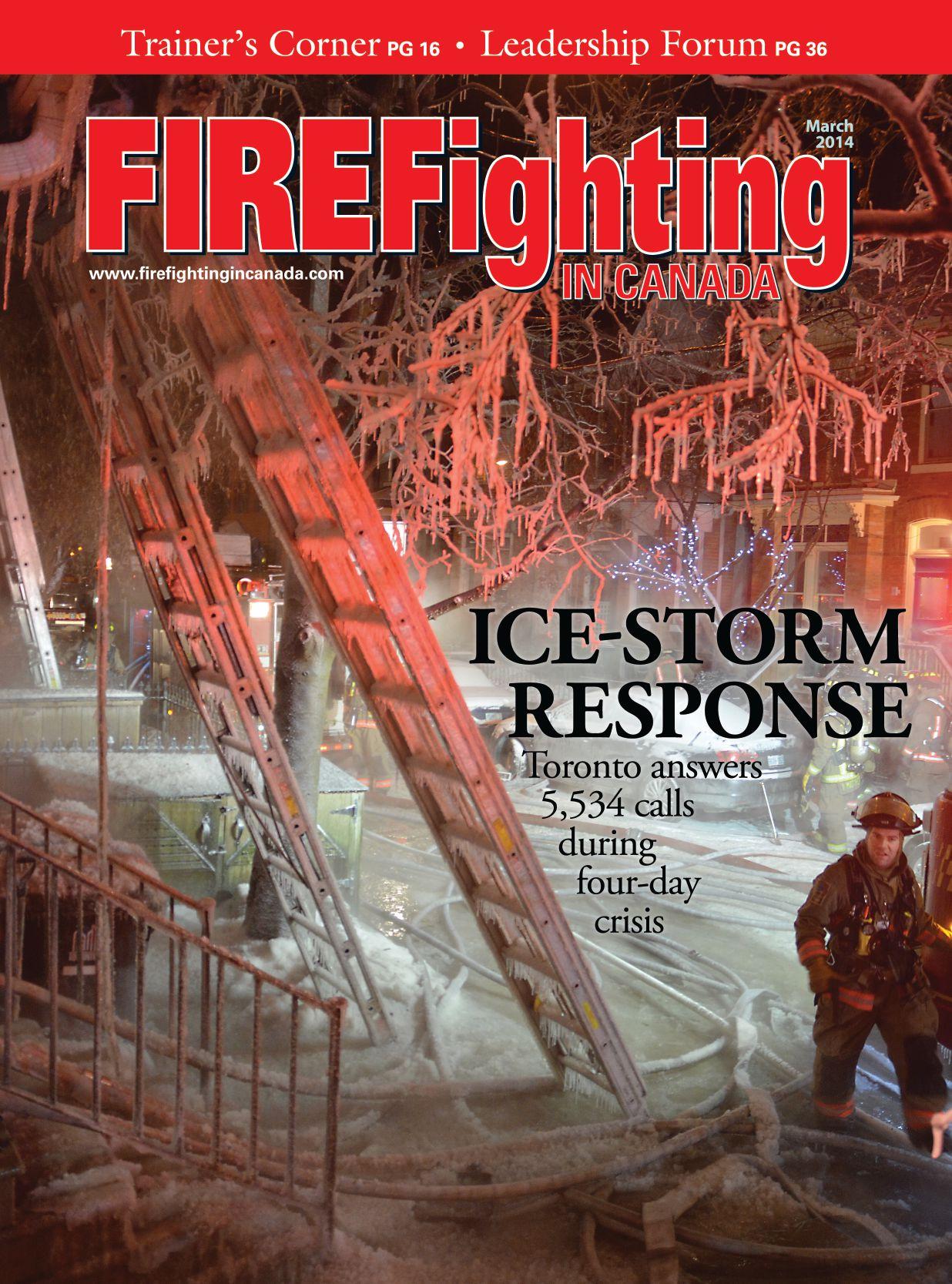

The ice storm that walloped southwestern Ontario in late December wreaked havoc on highways, residential streets and the power grid. As Deputy Chief Debbie Higgins writes, the storm, which left more than 300,000 people in Toronto without power and resulted in 9,655 vehicle responses in just four days, posed several complications due to power outages and calls for assistance.

28

The Surrey Fire Service in British Columbia has improved its customer service at motorvehicle incidents by stocking its apparatuses with packages for those involved in collisions. As Acting Capt. Dave Baird writes, the kits are one example of Surrey’s dedication to providing a higher level of support for residents and visitors.

38

GAS-INCIDENT PREPARATION

Seldom-used skills, such as those involved in the use of a gas monitor, can fade away with infrequent use. Bruce Lake offers a refresher on the do’s and don’ts of using a four-gas monitor, the finer points of maintaining the monitor, and what the results actually mean.

By L AURA K IN g Editor lking@annexweb.com

erspective is everything.

We know the ice storm that smacked southern Ontario on Dec. 21 and 22 affected dozens of fire departments from Kitchener to Kingston, and thousands of firefighters. Downed wires. Power outages. Collisions. Stranded motorists. Carbon monoxide incident. Fires.

We know that other provinces have had their share of what we now call weather events: bitter cold in Winnipeg; snow, rain, more snow, more rain in Nova Scotia; a colder-thannormal winter in Newfoundland and Labrador, combined with brownouts that led to myriad fire-safety issues.

And, as Toronto Fire Services Deputy Chief Debbie Higgins writes in her ice-storm story on page 10, we know that when things go sideways, fire gets the call.

to the retirement home. She will be able to relieve the weary nurses overnight.

“I think that this exemplifies the true spirit of Canadian firefighters. We will adapt and overcome any obstacle to solve the problem and get the job done, including the most ferocious blizzard in recent history.”

Dufferin County, northwest of Toronto, declared a state of emergency on Jan. 29 that lasted four days because there was so much snow and roads were so bad city crews couldn’t keep them clear. Four days earlier, Dufferin County firefighters had sheltered more than 500 motorists who were rescued from unpassable roads.

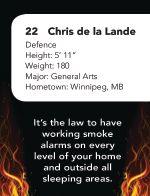

ON THE COvER

Toronto firefighters respond to a blaze that started in the basement and spread up the walls and into the roof during the December ice storm. See story page 10.

In early January, during a fierce snowstorm in southwestern Ontario, I asked fire departments on social media for examples of good news stories from the weather challenges.

Fire Chief Bill Hunter of Perth East e-mailed on Jan. 7.

“This evening,” he said, “my Milverton Station Chief Kim Newbigging received a call from a local retirement home. Their staff had basically been snowed in for the past 24 hours and they really needed a replacement nurse. Trouble was that the roads were all but impassable. ‘Could the fire department help?’

“So in true Perth County spirit, Chief Newbigging and Capt. Mike Carter got their snowmobiles and delivered the nurse

“Emergency services are being stretched to their limits to respond to these,” Dufferin County’s CAO said. “Effectively, all of our local resources have been exhausted.”

In big cities and small towns from coast to coast to coast, first responders seem to have been taxed more often, and more thoroughly, this winter than in most.

We’ve focused on Toronto in our cover story to bring perspective to the myriad challenges for first responders in a big city of more than 2.5 million people. Nineteen of Toronto’s fire stations lost power as did its emergency operations centre. Firefighters responded to 5,534 calls in four days. Perspective indeed.

ESTABLISHED 1957 February 2014 VOL. 58 NO. 2

EDITOR LAurA King lking@annexweb.com 289-259-8077

ASSISTANT EDITOR OLiViA D’OrAZiO odorazio@annexweb.com 905-713-4338

EDITOR EmERITUS DOn gLEnDinning

ADVERTISINg mANAgER CATHErinE COnnOLLY cconnolly@annexweb.com 888-599-2228 ext. 253

ACCOUNT COORDINATOR BArB COMEr bcomer@annexweb.com 519-429-5176 888-599-2228 ext. 235

mEDIA DESIgNER gErrY WiEBE gwiebe@annexweb.com

gROUP PUBLISHER MArTin MCAnuLTY fire@annexweb.com

PRESIDENT MiKE FrEDEriCKS mfredericks@annexweb.com

PuBLiCATiOn MAiL AgrEEMEnT #40065710 rETurn unDELiVErABLE CAnADiAn ADDrESSES TO CirCuLATiOn DEPT. P.O. Box 530, SiMCOE, On n3Y 4n5

e-mail: subscribe@firefightingincanada.com

Printed in Canada iSSn 0015–2595

CIRCULATION

e-mail: subscribe@firefightingincanada.com

Tel: 866-790-6070 ext. 206

Fax: 877-624-1940

Mail: P.O. Box 530 Simcoe, On n3Y 4n5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Canada – 1 Year - $24.00

(with gST $25.20, with HST/QST $27.12) (gST - #867172652rT0001) uSA – 1 Year $40.00 uSD

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Periodical Fund of the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Occasionally, Fire Fighting in Canada will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. if you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

no part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission ©2014 Annex Publishing and Printing inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. no liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

www.firefightingincanada.com

Fresh from winning Motor Trend Truck Of The Year® for an unprecedented second year running is the powerful New 2014 Ram 1500 In Special Service* Vehicle configuration, it offers Firefighters, EMS and First Responders the renowned 5.7 L HEMI V8 engine with 395 HP and 407 lb-ft of torque. Yet it’s also Canada’s most fuel-efficient full-size pickup ¤ With its Electronic Control System including All-Speed Traction Control, Hill Start Assist and Ready Alert Braking, Canada’s longest lasting line of pickups» helps you win in any situation.

Halifax Regional Fire & Emergency volunteer firefighters Greg Kutney, Jason Sparkes and Randy Johnson at Rideau Hall in Ottawa after being honoured by the governor general for bravery. Sparkes received the Star of Courage; Kutney and Johnson received the Medal of Honour.

Unfortunately, calls for people washed off the rocks at Peggy’s Cove, N.S., one of the most popular tourist destinations in Atlantic Canada, are not uncommon.

Rogue waves are a regular occurrence and people wandering too close to the ocean

can get into trouble quickly.

But on the night of Nov. 6, 2010, anywhere on the rocks was unsafe; some waves coming ashore were as high as three-storey buildings. So when the call came in at 6:08 p.m. for a person swept off the rocks, members of Halifax

DALE mCLEAN was appointed fire chief for Kamloops Fire rescue in British Columbia on Oct. 21. McLean, a 33-year fire-service veteran, joined Edmonton Fire rescue in Alberta in 1980 as a firefighter. He was promoted to captain in 2004 and to deputy chief in 2008.

DAVID FORFAR is the new fire chief for Caledon Fire and Emergency Services in Ontario. Forfar, who started in his new position on Dec. 9, has more than 30 years of fire-service experience. He was named district chief for Markham Fire and Emergency Service in 2000, and in 2007 became deputy fire chief for Barrie Fire and Emergency Service.

Regional Fire & Emergency’s Station 55 in Seabright were not surprised.

It’s an 18-minute run from Station 55 to Peggy’s Cove. Volunteer firefighter Greg Kutney was driving Engine 55 with a crew of three.

Volunteers Jason Sparkes and Randy Johnson were following behind in Rescue 55. Sparkes had no idea that in a few minutes he would be in the ocean himself.

Sparkes and Kutney had donned life jackets en route, grabbed their rescue gear and went to the top of the rock face with RCMP Const. Chris Richard. They gave the constable a life jacket and fanned out to see if they could spot the missing person. (They did not, and the body of that victim was recovered several days later.)

A lot happened in the next few minutes. Const. Richard was swept into the ocean by a huge wave and seriously

RyAN JAgOE was appointed deputy fire chief for East gwillimbury Emergency Services in Ontario on nov. 25. Jagoe previously worked as a paid-on-call firefighter with the East gwillimbury department, having been promoted to captain in 2011. He also has 11 years of experience as a paramedic and superintendent with the York region EMS.

injured when waves slammed him against the rocks.

Firefighter Sparkes was washed into the ocean twice trying to rescue Richard. Another RCMP constable, Scott Lock, was swept into the ocean. But they all survived, thanks in part to additional help from firefighters Kutney and Johnson. (See the January 2011 edition of Canadian Firefighter and EMS Quarterly.)

On Dec. 5, Kutney, Sparkes and Johnson were honoured for their bravery by Gov. Gen. David Johnston. Firefighter Sparkes received the Star of Courage. Firefighters Kutney and Johnson were awarded the Medal of Honour.

HRFE has submitted information to the RCMP regarding the outstanding bravery of Const. Lock. A possible nomination for a governor general’s award for bravery is being reviewed by the Force.

–

John Giggey

DERyN RIZZI was promoted to deputy fire chief for Vaughan Fire & rescue Service in Ontario on Dec. 6. rizzi, who is the first female chief officer in York region, joined the department in Vaughan in 2001. She was appointed acting captain in 2009 and became captain in 2013.

Toronto-based Safedesign has survived 25 years by striving to be the best firefighter gear distributor – and that’s it. As president Bill Sparfel said, the company’s secret to longevity has been to avoid diluting its core business.

“We focus on what we do and doing it better than anyone else,” Sparfel said in an interview.

“If you need parts for your rescue tools, we’re not the people to call. But if you need turnout gear, we’re the people.”

Safedesign Apparel Ltd. had its official start on March 1, 1989. Sparfel had spent 11 years working for Safety Supply

Canada but had always wanted to start his own company. That drive eventually led him to

turnout gear maker Globe.

“I went down to Globe’s manufacturing plant in New

Hampshire,” Sparfel said. “I made a deal to represent Globe outside of the continental United States.

“[That was] 25 years ago, and we haven’t looked back.”

Now Safedesign exclusively represents Globe in more than 80 countries.

To celebrate its quarter century in the business, Sparfel said the company is planning a big party for its 22 staff members.

“We take pride in what we’ve done,” Sparfel said. “It’s not just me; the success of any business is with the people who take pride in the business.

“We’re going to revel in our 25 years of history.”

– Olivia D’Orazio

Thunder Bay Fire Rescue in Ontario has teamed with the Lakehead University Thunderwolves and local telephone-service provider Tbaytel to release a series of limited-edition hockey cards that feature players from the university’s varsity team as well as a fire-safety message.

“We were looking for a way to get fire safety information into the hands of young children,” said Anthony Stokaluk, public education officer. “So the partnership with the hockey team

Thunder Bay Fire Rescue developed hockey cards to promote fire safety. The cards featured players from the Lakehead University Thunderwolves and were distributed to Grade 4 students.

IAN SHETLER retired from the greater napanee Fire Service in Ontario on Dec. 31. Shetler joined the napanee department as a volunteer firefighter in 1987. He was hired as full time in 1989, and rose through the ranks to training officer,

deputy fire chief and acting fire chief.

TERRy HUBBARD , communications co-ordinator with the Burlington Fire Department in Ontario, retired n ov. 28. Hubbard began working in communications with the Halton r egional Police Service in 1980, before moving to the Burlington fire department in 1985. i n 1999,

was a great fit.”

Tbaytel sponsored the campaign, covering the cost of the cards. Just 500 sets of cards were produced, with each set containing 30 cards.

The cards were available during the Thunderwolves’ last home game of the regular season on Feb. 15. Members of the Thunder Bay department as well as some hockey players also visited several elementary schools and minor hockey league events to distribute the cards and

promote fire safety.

In particular, the department targeted Grade 4 students, based on their age and interest in the university’s hockey team.

“It’s also a grade that we’re not targeting with our other public education events,” Stokaluk said.

“So we’d go to the classes with the LU players and the kids really bought into [the fire-safety messaging] because of the players.”

– Olivia D’Orazio

Hubbard worked as program co-ordinator for the Canadian Centre for Emergency Preparedness at Mohwak College. She returned to Burlington Fire in 2002.

RICK ADA m SON , 64, died Dec. 28 after a brave battle with cancer. Adamson was

a firefighter with the Town of Erin Fire and Emergency Services in Ontario for 20 years. He also was the president of the WellingtonDufferin Mutual-Aid Association, and was instrumental in getting the new Hillsburgh station operational. i n his honour, the communication room in the station is named The r ick Adamson Communications r oom.

The Panorama Fire Department in British Columbia, under Chief Martin Caldwell, took delivery in November of a Hub Fire Engines & Equipment-built light attack vehicle. Built on an International chassis and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a MaxxForce 330-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a 500-gallon water tank, a Whelen LED light package and a Zico Quic ladder.

The Leduc County Fire Department in Nisku, Alta., under Chief Darrell Fleming, took delivery in January of a Fort Garry Fire Trucksbuilt pumper. Built on a Spartan Metro Star chassis and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a Cummins 380-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Darley 1,050-gpm pump, a 1,000-gallon pro-poly water tank, a FoamPro foam system, a Federal Light package, FRC Focus telescopic lights, an Elkhart Vulcan RF monitor, On Spot tire chains and a Honda generator.

The Adams Lake Fire Department in British Columbia, under Chief Tony Dennis, took delivery in January of a Hub Fire Engines & Equipment-built pumper. Built on a Freightliner chassis and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a Cummins 330-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Hale Q-Flo 1,050-gpm pump, a FoamPro foam system, a 1,000-gallon co-poly water tank, Zico LAS ladder storage, a Whelen LED light package and Magnafire Push Up lights.

Flagstaff Regional Emergency Services in Flagstaff County, Alta., under Chief Kim Cannady, took delivery in October of a Fort Garry Fire Trucks-built tanker. Built on a Freightliner chassis and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a Cummins 350-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Hale 420-gpm pump and a 2,500-gallon co-poly water tank.

Edmonton Fire Rescue in Alberta, under Chief Ken Block, took delivery in January from Safetek Emergency Vehicles of a Smeal Fire Apparatus-built pumper. Built on a Spartan Gladiator chassis and powered by an Allison 4000 EVS transmission and a Cummins 500hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Hale Q-Max 1,875-gpm pump, a FoamPro dual foam system, a 480-gallon polyurethane water tank, Akron electric valves and a 15,000-watt Harrison hydraulic generator.

The Skeetchestn Band Volunteer Fire Department in British Columbia took delivery in January of a Hub Fire Engines & Equipment-built pumper. Built on a Freightliner M2 chassis and powered by an Allison 3000 EVS transmission and a Cummins ISL 350-hp engine, the truck is equipped with a Hale Q-Flo 1,050-gpm pump, a FoamPro foam system, a 1,000-gallon co-poly water tank, a Whelen LED light package, an Akron Apollo monitor, a Zico LAS ladder rack and a Honda generator.

By DEBBiE Higgins

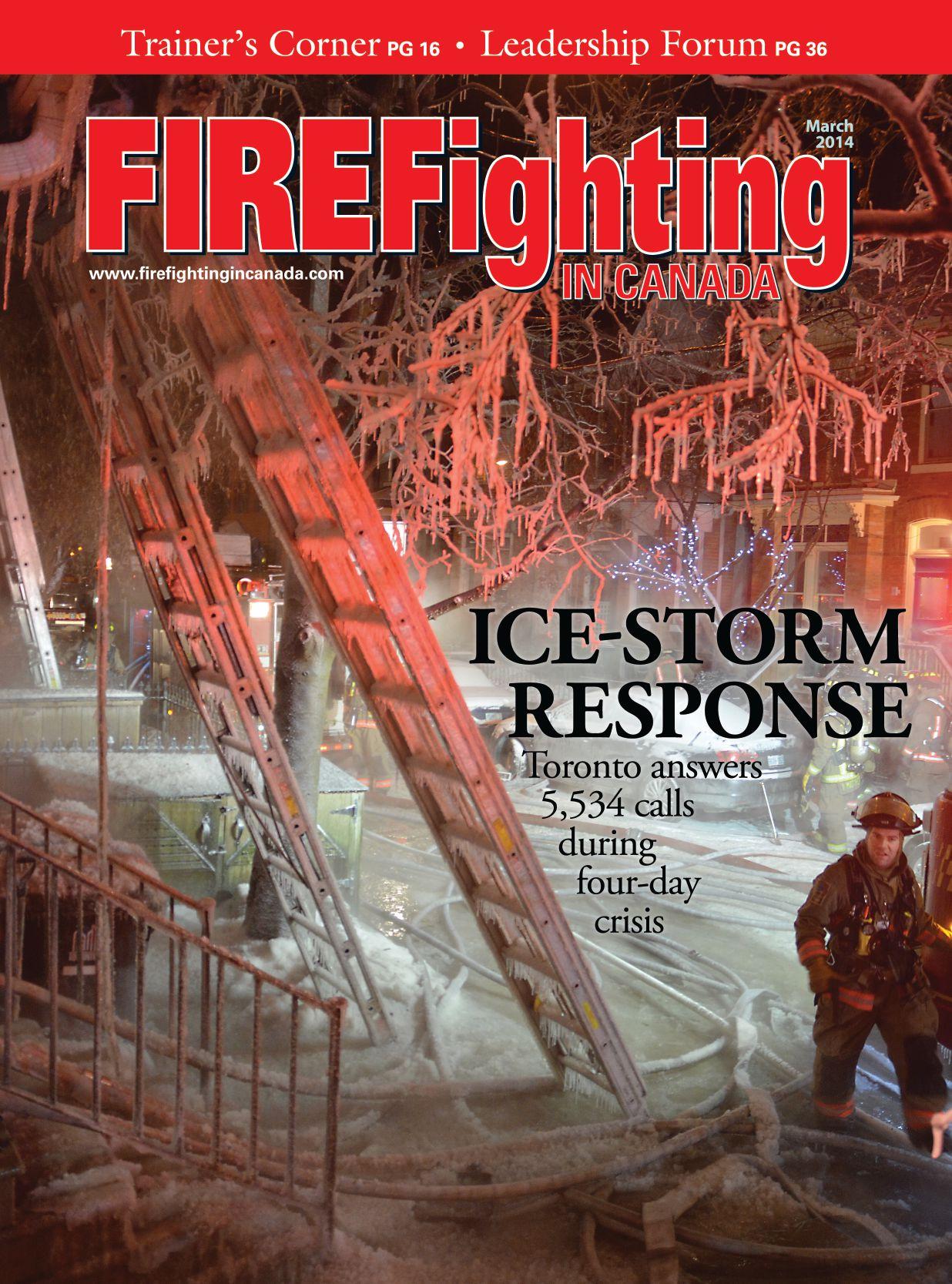

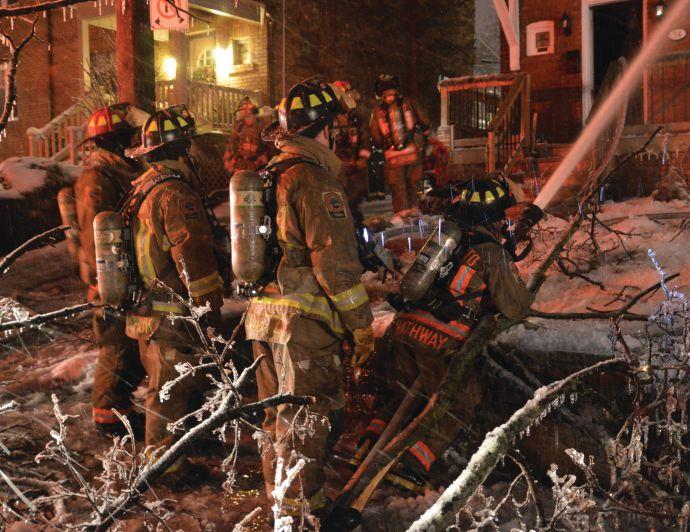

l eft and a bove: In addition to fires, Toronto Fire Services responded to 316 carbon monoxide calls, 813 medical calls, 128 rescues, 102 vehicle incidents and 538 check calls during and after the Dec. 21-22 ice storm.

the ice storm that walloped southwestern Ontario in late December wreaked havoc on highways, residential streets and the power grid. In Toronto, the epicentre of the storm, the 10 to 30 millimetres of ice that fell between 22:00 on Saturday, Dec. 21, and 07:00 on Sunday, Dec. 22, caused power outages for more than 300,000 people – that’s twice the population of Prince Edward Island.

Between 07:00 on Dec. 21 and the end of the spike in calls at 07:00 on Dec. 25, Toronto Fire Services (TFS) responded to 5,534 incidents, with 9,655 vehicle responses. In the same period in 2012, there were just over 1,200 incidents. Forty-two per cent of the calls during the storm – or 2,351 – were for downed wires. Of the 668 fire calls in this period, nine were multiple-alarm fires, and an additional 15 were working-fire responses, all made more difficult because of extreme weather conditions. There were 316 carbon monoxide calls, 813 medical calls, 128 rescues, 102 vehicle incidents and 538 check calls.

Two of the fire calls resulted in fatalities, both through the night on Dec. 24-25. The first was a male victim who died in a car fire; the vehicle was fully involved when crews arrived. The man was a resident of the building at which the car was located, which was without power at the time of the incident. The second incident was at a four-storey residential building that had full power, so there was no indication that the fatality was storm related.

Unlike the rain storm on July 8 that hit Toronto with no warning and caused flash floods – TFS responded to 1,185 calls in 24 hours – the freezing rain had been predicted for days in advance of the pre-Christmas ice storm.

The first update from Toronto Hydro was received very early on Sunday, Dec. 22 (just after midnight on Saturday, Dec. 21), indicating increasing power outages across the city, which were expected to persist as ice continued to form on power lines and tree branches.

At the time, there were about 8,500 customers without power, and Toronto Hydro was projecting that power could be restored in 12 to 16 hours. By 03:00 on Dec. 22, the number of customers without power had increased to 50,000; a few hours later the utility declared a Level 3 emergency, the highest level emergency. At the height of the emergency, the number of Toronto Hydro customers without power reached almost 300,000.

Of course, emergencies never seem to coincide with regular office hours so the initial storm response started with a conference call made very early Sunday morning from the homes of department heads and the most senior city staff, as the city tried to establish the extent of the damage from the ongoing storm and potential timelines for re-establishing normal operations. It became clear early on that this was a storm of enormous magnitude, and would require the co-operation of almost every city department to ensure citizens remained safe and warm.

Within a few hours the city had opened its Emergency Operations

Centre (EOC), but not without tremendous difficulty. The building that houses the EOC was one of the structures without power, meaning it could not be used for this vital operation. The back-up EOC location was also without power, and did not have generator back-up. As the primary EOC location is also the Toronto Police primary 911 call centre, and the city’s main data centre location, there was a significant amount of work that had to occur in a very short time to keep the city systems operational.

By late morning on Sunday, Dec. 22, a temporary EOC location had been devised at Metro Hall. Given that none of the rooms was big enough to house the entire operations, planning, logistics, finance and administration teams, the group split up over several office areas and communicated through regular conference calls – and a fair amount of walking up and down the hallways. Updates from the EOC on the status of operations of city divisions were sent out regularly to ensure that division heads, senior city staff and elected officials remained up to date on the status of the situation.

It is important to note that the ice storm was not a fire emergency; it was a hydro emergency more than anything (there was no state of emergency declared), but as we all know, when disaster strikes, the fire department is almost always called to do the heavy lifting, at least in the early stages.

TFS senior staff started working on our longer-term emergency plan early Sunday afternoon. Fire Chief Jim Sales worked with the mayor’s office, the city manager and other elected officials. A deputy chief and a division commander had been dispatched to the EOC for the start-up of operations, and the deputy chief of operations was at headquarters to oversee the activities of the department until the EOC could take over. I pulled the short straw and was assigned the first overnight shift in the EOC, from 22:00 on Dec. 22 until 07:00 on Dec. 23. However, once everyone became aware of the situation, all TFS senior staff became involved in the response, regardless of EOC assignments or scheduling.

The loss of hydro also hit TFS. By the time the freezing rain stopped late on Sunday, 19 fire halls had lost power, which also meant they were without heat. While fire crews were busy responding to emergency calls, staff from our heavy urban search and rescue team began to distribute generators and portable heaters to as many

• BACK-UP POwER, EqUIPmENT AND COmmUNICATION SySTEmS

The city should have a back-up EOC with a generator, and should ensure that staff have access to all necessary supplies, including laptops, in emergencies. Because the entire city network was down – it is housed in the same building as the EOC –communication was spotty for several hours. TFS deputies set up a BBm group to share information; a better system is needed.

• RELIEF STAFFINg

TFS works 24-hour shifts. During the ice storm, crews were so busy there were few, if any, opportunities for breaks. Because all halls were running flat out, TFS did not have the capacity to provide relief, as it would at a big fire scene or a localized incident. The same was true for communication staff, who worked straight through their shifts with no breaks or meals.

• RECORD mANAgEmENT

TFS found out after the fact that many trucks, when returning from calls, came across other incidents and stopped to help make wires safe or assist with other tasks. given the overload at communications, crews did not necessarily radio in and create these additional stops as incidents. As such, while response numbers were very high, they may have been considerably higher had all calls been logged. TFS is considering options for better incident reporting.

halls as possible. Mechanical staff were called in for the duration of the outage to go from fire hall to fire hall to start up and refuel generators.

Not surprisingly, most of the calls to which TFS responded in the first hours of the storm were related to downed wires. Crews responded as quickly as possible, in most cases working to make each situation safe so they could move on to the next location. Our communications centre kept

a list of all wires-down locations to pass on to Toronto Hydro, as it was having difficulty keeping up with the volume of calls.

The first update from our communications centre came at 18:00 hours on Dec. 22, by which time staff had a handle on the volume of calls and were able to start generating some statistics. At the time, they reported that between 16:00 on Dec. 21 (the night of the storm) and 06:00 on Dec. 22, TFS had responded to 1,200 calls,

Since March 4, 1989 Safedesign Apparel Ltd. has been the recognized solution provider to the Fire Service, committed to providing premium, technologically advanced personal protective equipment and accessories to first responders around the world.

After 25 years, Safedesign is thriving and positioned for continued growth.

Thanks to our valued customers. We look forward to working with you over the next 25 years.

almost 800 of which occurred between midnight and 06:00. Almost 500 of those calls were related to downed wires, but there were also a significant number of alarm ringing calls and elevator-rescue calls as the power shut down across the city.

It became obvious that TFS would not be able to keep up with the call volume, and in the early hours of Dec. 22, our single-truck response protocol was activated. This protocol allows TFS to treat fire alarm ringing calls and any others deemed appropriate as if they are check calls (depending on the information available at the time of the call), so that we can respond to more incidents in a more timely fashion. Even with that protocol in place, by 15:00 on Dec. 22 we had more than 150 responses pending, waiting for a truck to be available. The number of pending calls fluctuated for many hours, and it wasn’t until 04:00 on Dec. 23 that crews responded to the last pending call, the single-truck response protocol was terminated, and we returned to normal dispatching procedures. (TFS did not call for mutual aid; all surrounding municipalities were dealing with similar circumstances and most calls were make-safe situations.)

As the city began to wake again the morning of Dec. 23, TFS again began to generate lists of pending calls, but not to the extent as in the previous 24 hours. Monday, Dec. 23, brought new challenges, as many staff returned to workplaces in civic centres and other locations that were still without power. Last-minute arrangements had to be made to accommodate staff (particularly those in fire prevention, who tend to work in civic centres) in offices other than their own until power could be restored at their base locations, which generally did not happen until after Christmas.

By the end of the day on Dec. 23, and through the night to Dec. 24, TFS had largely caught up on all responses, and had offered about as much assistance to Toronto Hydro as was possible. By 15:00 on Dec. 24, senior staff of TFS were no longer staffing the EOC, but remained on call to assist should the need arise. Toronto Hydro continued the painstaking process of restoring power, which was not entirely complete until the first week of January. The city in general continued in emergency mode until after the new year, operating warming centres for citizens during the day and at night, and providing as much assistance as possible through wellness checks carried out by police, fire and shelter, housing and support.

While the majority of the calls to which TFS responded throughout the emergency were related to wires down, it became evident that the loss of power – especially within a few days of Christmas and during a particularly cold spell – was causing citizens to disregard fire-safety messages, resulting in a number of significant fire incidents. On Dec. 23, TFS issued a press release stressing ice-storm related fire-safety tips, largely focused on candle safety, cooking, heating and messages related to carbon monoxide, which was increasingly becoming a problem as residents looked for ways to provide heat to their homes. These fire-safety messages continued to be promoted through daily press conferences held by the mayor and other senior staff. In addition, TFS communications staff used social media to send out safety messages.

While the ice storm emergency is over, southwestern Ontario was – when this was written – in the midst of what weather experts said may have been the coldest winter in 25 years. It appeared that all emergency services need to be prepared for extreme weather events of all types, as meteorologist and climatologists say they are likely to increase in frequency. Several valuable lessons were learned through this ice-storm experience, as unlike the flood of July 2013, there was a prolonged period of higher-than-normal call volumes and responses to non-fire-related events.

Good emergency planning by the municipality and the fire service is required to ensure we continue to meet our goal of service to the public no matter the circumstances.

Debbie Higgins is a deputy chief with Toronto Fire Services, responsible for fire prevention and public education. Debbie previously held the portfolio of staff services and communications, following her promotion to deputy in 2010. Prior to this, she spent 11 years as an executive officer for TFS, with responsibility for special projects. Debbie previously worked with the City of Mississauga as a business planner, where her work included strategic projects for the fire department. Before joining the municipal sector, Debbie spent five years working as a consultant. She has a degree in applied geography from Ryerson University and a certificate in business from McMaster University. She is completing her diploma in public administration through the University of Western Ontario. Contact Debbie at dhiggin@toronto.ca and follow her on Twitter at @debbiejhiggins

By ED BROUwER

while developing our department’s standard operational guidelines (SOGs), I was shocked to see the scope of duties performed by the training officer. Certainly every firefighter and fire officer plays a vital role in Canada’s fire services, but I believe – though I am biased – the highest calling is to be a training officer.

Our guidelines state that all training officers shall – a more palatable term than must – be familiar with and carry out their duties outlined in the operational guidelines and reference documents. While subject to the requirements of written orders and regulations, and the verbal directions of a superior, the training officer will exercise independent judgment and action while in command at fires and rescues. Under the direction of the fire chief, the training officer will develop and deliver the fire department training program to all fire department members.

The guidelines explain that the training officer is responsible for:

• determining the department’s training needs,

• maintaining training records for all fire department members,

• developing the department’s training programs,

• evaluating the continuity of training and the department members’ skills and knowledge,

• scheduling and co-ordinating special training sessions,

• conducting training,

• participating in firefighting operations, at times entailing the command of an incident, apparatus, equipment and department members on the fire ground,

• supervising firefighting activities, including laying hoselines, directing water streams and the required pressure of those streams, placing ladders, ventilating buildings, rescuing victims, administering first aid and placing salvage covers,

• directing the overhaul and cleaning of the premises after the fire has been extinguished,

• supervising the return of all apparatus and equipment to their proper places in the fire hall, and

• compiling and keeping various records and reports, as assigned.

Your department’s SOGs will be close in comparison to those listed above. This represents an impressive yet doable list of responsibilities; and therein lies the rub. Even if you follow these responsibilities to the letter, there is no guarantee that you will be effective in your role as instructor. It takes certain character traits to be an educator.

It takes certain character traits to be a great training officer. Think back to your own instructors. What was the most effective training session you attended, and why was it so effective?

The practical components of many training officer courses focus on developing lesson plans and teaching the techniques required to prepare and deliver a training program – including exposure to new teaching aids and evaluation methods.

Think back to your instructors. I’m sure we have all had some examples of what not to do. But take a moment and reflect on the traits of a person who you felt was a great communicator in the classroom. What was it about that instructor? What was the most effective training session you attended, and why was it so effective?

I want you to become a better-than-average training officer. I encourage you to check out the various fire schools

More Power... More Torque ... Better Fuel Efficiency

More Power... More Torque ... Better Fuel Efficiency

75% Less Emissions

75% Less Emissions

The new Dual-Air intake engine technology significantly improves overall cutting performance and meets all Air Quality Control standards at the same time.

New 2100 Series includes two engine sizes: 70.7cc and 87.9cc. Each engine is designed for use with Cutters Edge Carbide

Tipped BULLET Chain® to cut the widest range of materials found at fireground and rescue scenes.

New H Series is engineered and powered to work harder and operate longer in the most extreme fire and rescue conditions anywhere. The new technology engine is available in three sizes: 74cc, 94cc and 119cc. The Cutters Edge Black Star and Black Diamond Blades offer long cutting life and high speed cutting of virtually all materials.

New BULLET BLADE TM is now available - see video on website

A new technology 94cc engine and a new style Diamond chain cuts reinforced concrete up to 16-inches thick. Features a lighter weight power head and full-wrap handle for high performance concrete cutting in any position.

All Cutters Edge NEXT GENERATION TECHNOLOGY Fire Rescue Saws are available in fully-equipped Field Kits designed for Rescue Cutting anywhere.

Contact Your Local Cutters Edge DealerSee New Engine Technology Video Now

WESTERN CANADA

WFR Wholesale Fire & Rescue Ltd. Calgary AB - Ph 403-279-0400

1-800-561-0400

Web: www.wfrfire.com

QUEBEC

Areo-Fire

5205 J-Armand Bombardier

Longueuil QC, J3Z 1G4

1-800-469-1963

E-Mail: info@areo-feu.com

NEW BRUNSWICK

Micmac Fire & Safety Source 518 St. Mary's Street, Unit 1 Fredericton, NB E3A 8H5

1-800-561-1995 or (506) 453-1995

E-Mail: r.henderson@mmfss.ca

NEWFOUNDLAND

Medical West Supplies 13 Rowsell St., Corner Brook, NF

709-632-7852

E-Mail: jkenny@nf.sympatico.ca

ONTARIO

M&L Supply Ingleside, ON 1-866-445-3473

Email: markp@mnlsupply.com Web: www.mnlsupply.com

NOVA SCOTIA

Cumings Fire & Safety Equipment Ltd. Bridgewater, NS Ph 902-543-9839 1-800-440-3442

E-Mail: kylej@cumings.ca Web: www.cumings.ca

across Canada, looking specifically for a fire instructor course.

If you have a little bit of money set aside in your training budget, attending a fire instructor course is a good investment. Some courses offer a combination of distance education and hands-on workshops. These courses do not teach you how to fight fire – you had better have a handle on that already!

The theory components of these courses usually cover the fundamentals of learning theory, interpersonal communications, an overview of safety and legal considerations for the instructor, management of the learning environment and student behaviour, and lesson plan development.

The practical components focus on developing lesson plans and teaching you the techniques required to prepare and deliver your training program. You will be exposed to training aids and evaluation methods. You may even learn some new methods of record keeping.

Before you dismiss this idea of fur-

thering your education, understand that instructors can only take his or her students where they have gone. A great teacher never stops learning, or as singer Phil Collins said, “In learning you will teach, and in teaching you will learn.”

For many years I have been pushing for training officers to involve their students. Hands-on training is my go-to practice. However, there is a lot of theory in firefighter training and that cannot always be hands-on. Albert Einstein said, “Any fool can know. The point is to understand.”

So how do we get firefighters to understand fire fighting rather than just know how to do it? Benjamin Franklin, who co-founded the first volunteer fire department in Philadelphia, said, “Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn.”

There are many ways to involve your students in the classroom setting. The website Teachers Pay Teachers (www.teacherspayteachers.com) has downloadable PowerPoint templates for games such as Jeopardy, Family Feud, and Who Wants To Be A Millionaire.

It’s important for training officers to advance their skills in order to bring new and effective methods to their departments.

I bought the Jeopardy game for $10 and spent several hours filling in the blanks with Firefighter Level I questions and answers. It was quite easy – and I type with two fingers! We projected the game on the wall of the fire hall, and the firefighters got right into it.

The only limitation to you being an effective fire-service training officer is your level of willingness to advance your personal skills as an instructor. Once you are willing to keep learning, mix in a healthy portion of creative imagination and a good measure of humour.

Until next time please stay safe, and remember to train like lives depend on it.

Ed Brouwer is the chief instructor for Canwest Fire in Osoyoos, B.C., and Greenwood Fire and Rescue. The 24-year veteran of the fire service is also a fire warden with the B.C. Ministry of Forests, a wildland urban interface fire-suppression instructor/evaluator and an ordained disaster-response chaplain. Contact Ed at ebrouwer@canwestfire.org

By gORD S CHREINER Fire Chief, Comox, B.C.

ffective radio communication is the most important safety factor on the fire ground. While not all fire departments can provide a radio for each firefighter, it is safe to say that more radios on the fire ground mean a safer fire ground. However, if radio discipline is not practised, more radios also make for a more complicated fire ground.

The first step in effective communication is to select a basic model that works for your department. The next step is to train, either on the training ground or in the classroom, using the model.

As with most of the topics I write about, I like systems that are simple. If you don’t have a system in place, you are likely to spend more time trying to sort out radio communications than you spend trying to solve the problem to which you were called in the first place.

I suggest a model known as the four Cs of communication: connect, convey, clarify and confirm.

Here is an example of the system:

The incident commander (IC) wants to communicate with Team1. Connect: Command calls Team 1: “Team 1 from command.” Team 1 responds: “Team 1.” If Team 1 were to say, “Go ahead,” the IC would not know definitively with whom he or she is communicating. Convey: Command sends a message: “Team 1, withdraw from structure.”

Clarify: Team No. 1 clarifies: “Team 1 is withdrawing from structure.” If Team 1 just says, “Roger,” it is unclear if the message was understood. Confirm: Command confirms: “Affirmative Team No. 1.” This system is very simple, easy to use and very reliable. However, it still needs to be practised.

When should a team communicate on the radio?

• 100 per cent of the time when asked to do so. Why? So we know you are safe.

• 100 per cent of the time to convey important information, such as the number of victims, fire location and status, and any benchmarks. Who should be speaking on the radios? Team leaders only; other members on the team should have their radios on (why carry a radio if you are not going to turn it on?) but the volume should be turned down. Team leaders speak; other team members listen and speak only when asked or if they become separated from the team.

What you say over the radio should mean something. I recommend that every fire department develop a glossary of terms. A simple document with 20 to 30 words should be developed and shared with the department (and with neighbouring departments) so that everyone knows the terms and their meanings. Why? Incident commanders don’t have time to explain the meaning of each order on the fire ground at 3 a.m. Does everyone understand that evacuate, withdraw and abandon each have different meanings? If your firefighters do not know the proper meaning of each word, your fire ground will quickly become more challenging and dangerous than it needs to be.

i f you don’t have a system in place, your radio communication can become a big challenge. ‘‘ ’’

• 100 per cent of the time when entering a structure or an environment immediately dangerous to life and health (IDLH). Why? For many reasons, but the No. 1 reason is to ensure your radio is on and turned to the right channel. Other reasons are to let others on the fire ground know what you are up to and to confirm your orders.

• 100 per cent of the time when exiting a structure or environment that is IDLH. Why? So everyone knows you are out.

• 100 per cent of the time when changing floors. Why? So everyone knows where you are.

Gord Schreiner joined the fire service in 1975 and is a full-time fire chief in Comox, B.C., where he also manages the Comox Fire Training Centre. He is a structural protection specialist with the Office of the Fire Commissioner and worked at the 2010 Winter Olympics as a venue commander. Contact him at firehall@comox.ca and follow him on Twitter at @comoxfire

Do you have a formatted status report? Again, select a model and practise it. I like to use the TAP acronym for my status reports. Team: is your team accounted for? Air: what is the lowest level of air on your team? (We use only two choices for air supply – above 50 per cent or below 50 per cent; this lets command know which teams can continue working and which teams should be withdrawn.) Position: where is your team? This report confirms much of what should already be on the IC’s scene-management board, while checking on the firefighting team’s air supply. Teams can add other pertinent information if needed.

A status report is different from a roll call, which is used to quickly determine if all of the teams are still accounted for. Often after a collapse, explosion or other major fire-ground event, both a status report and a roll call are requested to achieve a personal accountably report.

Practise these simple radio models and your fire ground operations will go a lot smoother in the future.

By T O m D E S ORC y

Fire Chief, Hope, B.C.

ocial media can be our best friend or our worst enemy. Say the wrong thing, post the wrong picture and you have more than egg on your face. In the past year, I’ve sat in on four or five sessions involving the use of social media in emergencies, and it’s this fear of posting the wrong thing that I think has scared people away from being regular participants. Frankly, I thought we were beyond that; using this concern as an excuse to not get involved is starting to wear a little thin with me. More and more fire-service managers have discovered that we can use social media to our advantage.

A close friend of mine recently got a new smartphone. This guy comes from the rotary-dial generation. Naturally, I got involved helping to set up the phone, when he said, “Hey, sign me up for Twitter.” He really doesn’t know why he wants to “be on it,” just that he does. I’m pro-social media for just about anyone but if you want it just to say you have it then it’s not for you. Needless to say, my friend’s education now begins, but his attitude brings up an excellent point: too many chief fire officers jump into social media – in particular, Twitter – create a profile and then that’s it. To be effective on Twitter, you need to take it to the next level. Think about it: the pump on your truck won’t work when you need it if it hasn’t been used regularly. Twitter is not going to work for you if you don’t embrace it and learn how to manage it.

In fire fighting, training and practice are two different things. Sometimes you learn something new; other times you practise the skills you already have. In the world of social media, you learn technique and practise common sense. Getting your point across in 140 characters or fewer can be tough. Add a hashtag or two and mention the right people and you’ve got your work cut out for you to stay within the character count. Twitter is based on an advertising practice – I tell two people and they tell two people and so on. Because Twitter is written rather than spoken, it remains accurate no matter how many times it’s repeated. However, inaccurate information on Twitter can be re-tweeted and, therefore, the error is perpetuated; that’s why it’s so important to be active on your account – to make sure correct information goes out regularly and that any incorrect information is quickly corrected by you or your department. Starting out on Twitter may seem like a bit of a project but it’s really just information you already have: you create a profile, a presence in the online world, which gives you an opportunity to

promote and sell yourself and your department and monitor what’s going on.

Twitter is a two-way street. Not only are you developing a following, but you also have the ability to follow others and see what they are saying about you or your department. If you see something you like, you can support it by “favouriting” it, or re-tweeting it. If there are inaccuracies you can correct them or even ignore them. This form of communication is extremely valuable in incidents as today everyone else knows as much about our activities as we do and sometimes even more. Take a look around an emergency scene and try to count the number of mobile devices recording everything – all the more reason to know what they are saying. I recently followed the operation of a major structure fire from a department 500 kilometres away and knew exactly what was going on even though none of the information came from the department itself – it all came from bystanders. Many departments that have Twitter accounts have demonstrated the effectiveness of this medium for communicating in emergencies. The fact that the departments had an established following before the incident made getting their messages out much easier. How do

You create . . . a presence that gives you an opportunity to promote and sell yourself and your department and monitor what’s going on. ‘‘ ’’

you develop that following? Follow people, agencies and departments you’re interested in. Follow me and other Fire Fighting in Canada writers but don’t stop there. Tweet and re-tweet. By doing this you are developing a presence and when the time comes, you will have an established audience. If you’re still worried about being painted in the wrong light, well, social media is just that – social; if it’s not socially acceptable behaviour then don’t post it.

Tom DeSorcy became the first paid firefighter in his hometown of Hope, B.C., when he became fire chief in 2000. E-mail Tom at TDeSorcy@ hope.ca and follow him on Twitter at @HopeFireDept

I grew up in the media so I’m drawn to this type of communication. However, the fire world in which I grew up was one in which our activities were kept a secret of sorts. We didn’t tell the public what happened at a fire scene. We seemingly went about our business anonymously, which I found ironic as we were called to duty by a fire siren that the whole town heard. If you wanted to go to a call without anyone knowing, then that certainly wasn’t the way to do it.

We

■ Internal Ladder & Suction Hose Storage

■ 1000 IMP/1200 US Gallon Copoly Tank

■ Heated Pump Compartments

■ Gear Box Rise (For better driveline angle)

■ Freightliner Chassis

■ Aluminum Body (5083 Salt Water Marine Grade)

■ 20 Year Body Warranty

■ Darley PTO Rear Mount 1050 IMP/1250 US Gallon Pump

■ Grass Nozzles Option

■ Foam System Options

■ 12V Bumper Turret w/ Joystick Option

■ 100’ Hose Reel Under Cab Option

■ Aluminum Body (5052 Fresh Water Marine Grade)

■ 10 Year Body Warranty

■ High Side Compartments

■ Aluminum Extruded Rub Rails

■ Amdor Roll Up Doors

■ Two Speedlay Hose Beds

■ Short Wheelbase

■ Side Control Pump House

■ 800 IMP/960 US Gallon Water Tank

■ Foam System Options

■ Freightliner or International Chassis

■ Wildland Option

By MARk vAN DER fEyST

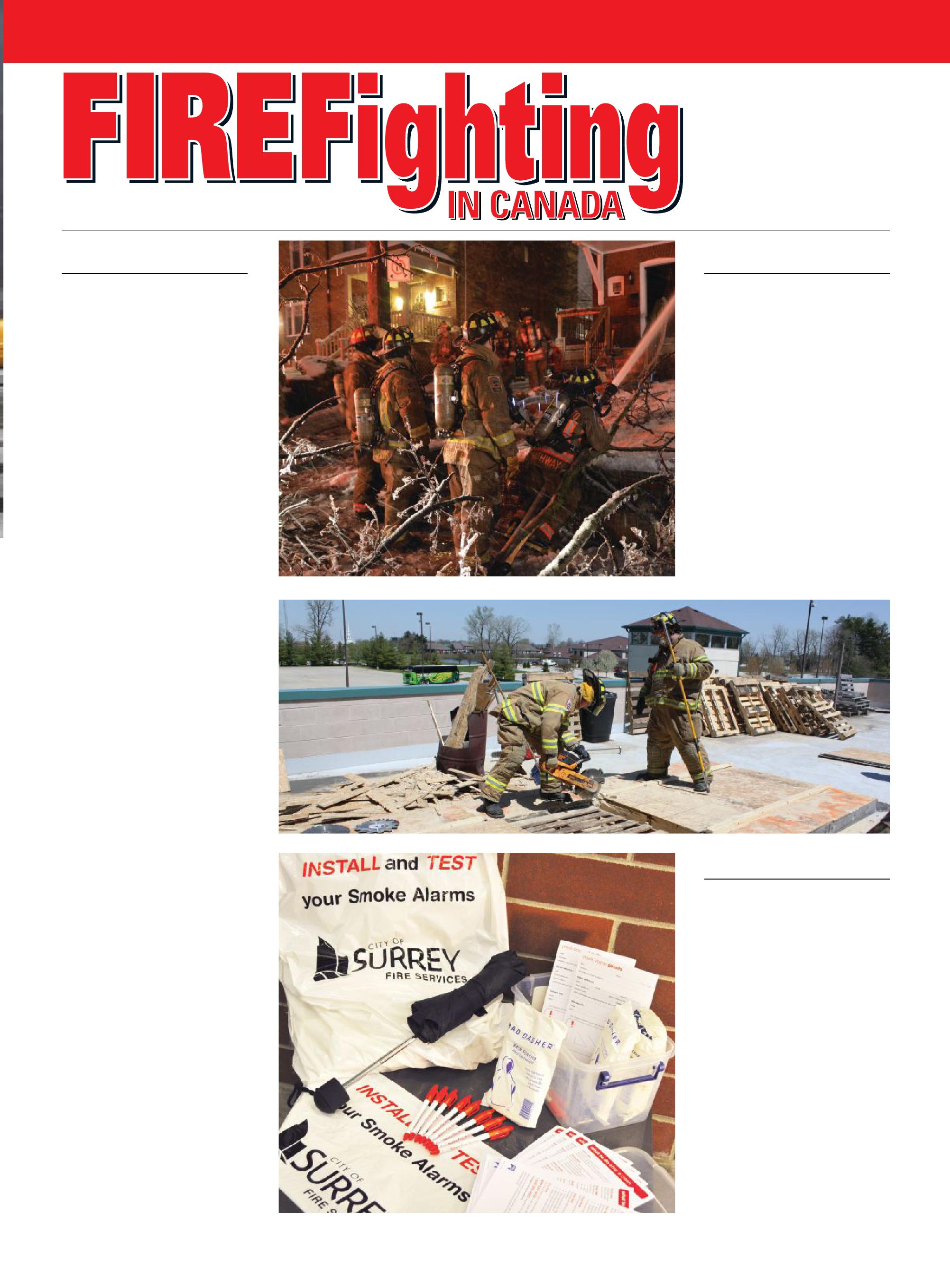

In February, we explored some aspects of flat-roof ventilation, such as safety considerations and the composition of the roof. Now, we’ll look at two ways to ventilate a flat roof.

Depending on the roofing material, use either a rotary saw or a ventilation saw to make the cuts. Determining which saw to use requires some planning. The rotary saw is almost always the best choice because most flat roofs involve some type of metal. Make sure the saw is fuelled, and always bring a set of hand tools with you to help you make the cuts, remove the roofing material, sound the roof deck, and in a worst-case scenario, finish the cut for you. Ideally, bring a flathead axe or a pick head axe and a 1.8-metre (six-foot) roof hook or pike pole.

■ COffIN CUT

The coffin cut – also known as the 7-9-8 cut – is one way to ventilate a flat roof. As you can see in photo 1, there are four steps to make this cut; the cuts resemble the numbers 7, 9 and 8.

The first cut follows the 7 pattern. The firefighter makes two cuts in the shape of the number 7, roughly 1.2 metres (four feet) along the top part of the 7 and about 1.8 to 2.4 metres (six to eight feet) along the spine of the 7. This sets up the coffin cut to be divided into two 1.2-metre by 1.2-metre (four-feet by four-feet) openings, allowing for one large vertical ventilation exit point. The two halves also allow crew members to handle only a small section of the roof – a 1.2-metre by 1.2-metre (four-feet by four-feet) section – at one time, rather than one large section.

The second set of cuts transforms the 7 into a 9 shape by cutting down about 1.2 metres (four feet) from the tip of the 7 and then across to the centre of the spine of the 7. When making these cuts, overlap the corners by about 15.2 centimetres (six inches). This frees the section of roof that is being cut from any obstructions and ensures that it is fully detached from the roof. When the corners are not overlapped, more work is involved to free the cut section.

The third set of cuts is the point at which the 9 becomes the 8. Two more cuts are made down and across to finish the number 8. Once completed, make a diagonal cut in the corner of the 8. This diagonal cut can be made either at the end of the series, at the beginning with the number 7, or at both points in the operation.

This diagonal cut creates a small triangular hole, allowing a roof hook or a pike pole to be inserted. This cut will aid as a starting point in pulling up the material.

Pulling up the roofing material takes some effort. Once the material has been removed, do not let it fall inside the building – place it beside the opening.

The square cut is another way to ventilate a flat roof. The square cut is a shortened version of the coffin cut – just five cuts are made in total and the size of the opening can vary. The advantage of the square cut over the coffin cut is that a firefighter making the square cut travels in one direction all the way around the cut. The coffin cut requires a change in direction, providing opportunities for tripping, unsafe footing or even falling into the hole.

The firefighter makes four separate cuts (see photo 2), each overlapping one another by at least 15 centimetres (six inches). The firefighter then finishes the square with a diagonal cut.

There should always be two firefighters making any type of roof cut. The firefighter making the cut focuses on the operation. Another set of eyes are required to guide and watch over the conditions, the surrounding area and any other hazards. It is important that the firefighter making the cut is aware of his partner’s feet and body

in relation to the rotary or ventilation saw.

In photo 3, you can see how the firefighter working the rotary saw is being guided by the second firefighter. This is a tandem operation in which the second firefighter is usually behind the first firefighter. The guiding firefighter can get the attention of the cutting firefighter by tapping his shoulder. Notice that the hand of the guiding firefighter is placed on the back/ shoulder of the cutting firefighter. This is another way to maintain accountability between the two.

In photo 4, you can see what should not take place: the guiding firefighter is no longer behind or beside the cutting firefighter, but is in front of him. This is a bad position in which to be as the debris from the cut is being thrown into that pathway and because team integrity is now broken. Always make sure the guiding firefighter is beside or behind the cutting firefighter.

Mark van der Feyst is a 15-year veteran of the fire service. He works for the City of Woodstock Fire Department in Ontario.

Mark instructs in Canada, the United States and India and is a local-level suppression instructor for the Pennsylvania State Fire Academy and an instructor for the Justice Institute of BC. E-mail Mark at Mark@FireStarTraining.com

By DavE BairD

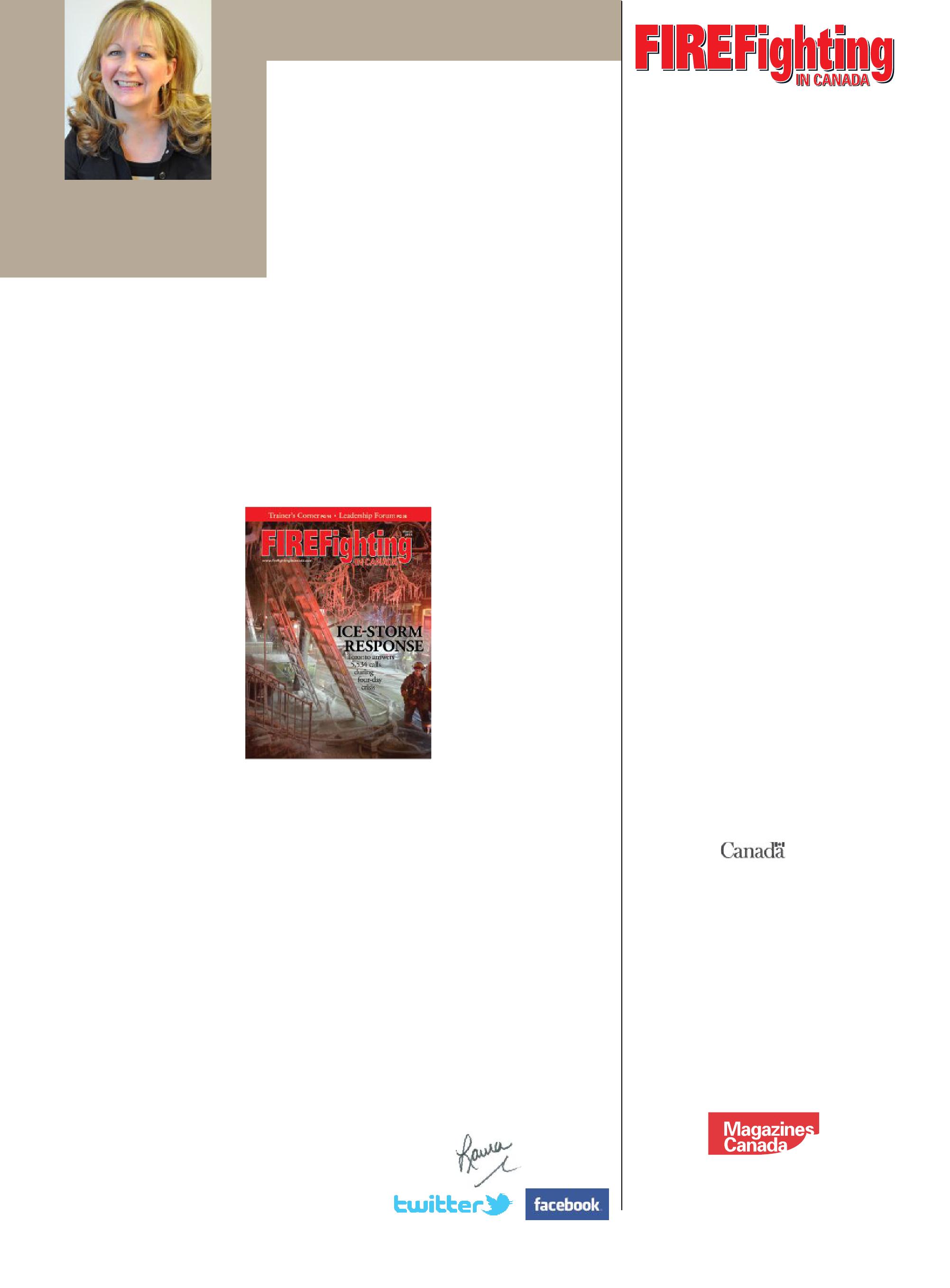

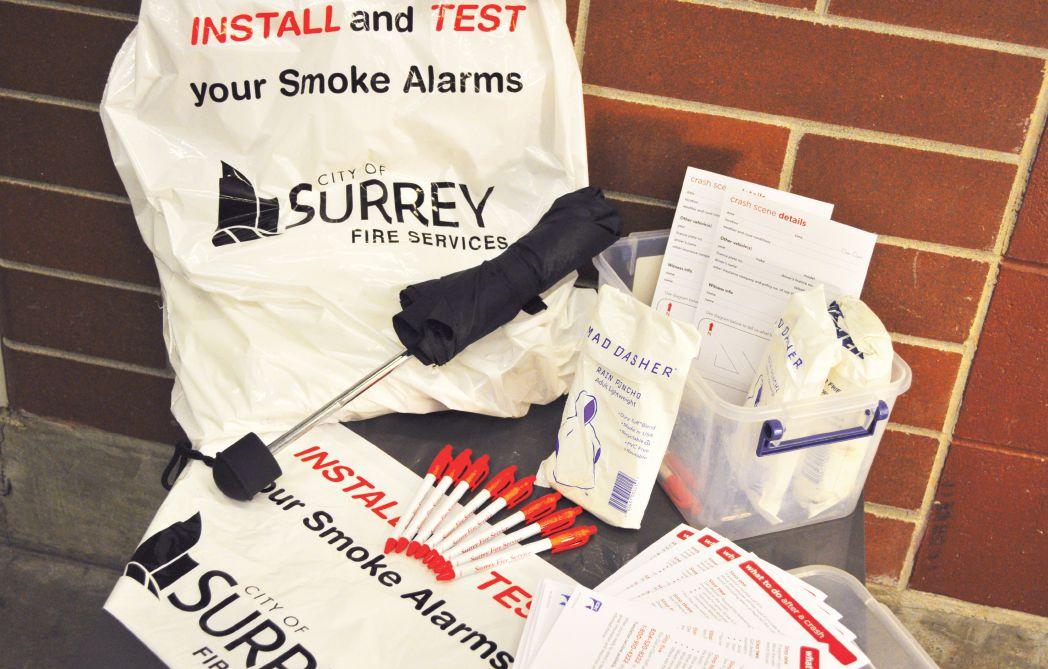

top and r I ght: The costefficient MVI Kit that is carried on all Surrey apparatuses includes insurance cards, pens, bags for belongings, ponchos, and umbrellas. Surrey had bags specially made that feature the department logo and a fire-safety message.

You and your crew are dispatched to a motor vehicle incident (MVI). The first order of business is, of course, to secure scene safety – the apparatus driver positions the vehicle to ensure the safe flow of traffic around the scene. Once all of the hazards are removed from the scene the next priority is the care of the patients. If it’s raining, back to the truck to search for an umbrella and rain ponchos for the patients who are not ambulatory and will remain on the scene.

Back on the scene, the driver of the car, who we’ll call Mr. Smith, expresses concern

over reporting the incident to the insurance company, so, back to the truck to find the exchange information cards to assure Mr. Smith that the insurance company is involved.

Whoops, of course Mr. Smith doesn’t have a pen. Back to the truck to find a pen.

Mr. Smith’s car is about to be towed away. Back to the truck to grab a plastic bag for his possessions. While the possessions are being packed into bags, Mr. Smith misplaces the pen. Back to the truck for another pen . . . Does this sound familiar?

The Surrey Fire Service responds to more than 4,000 MVIs every year, this accounts

The needs of the myriad Mr. Smiths who are involved in collisions every day are varied and unpredictable; nonetheless, every time contact is made with a person in the community, there is an opportunity to demonstrate a high level of customer service that has become a tradition in the Surrey Fire Service.

for 15 per cent of the total emergency response incidents in Surrey. Firefighters regularly witness firsthand the trauma and confusion that people face when confronted with these unexpected incidents. Customer

service is a large part of the modern fire service. One of the challenges responders face is co-ordination of all the available resources for success at an incident.

Members of the Surrey Fire Service have

developed a tool called the MVI Kit that saves time and frustration at MVI scenes. The project had the support of administration, Local 1271, and Surrey Fire’s customer service committee. The kit gives responders an opportunity to provide a higher level of support to those involved in collisions.

The needs of the myriad Mr. Smiths who are involved in collisions every day are varied and unpredictable; nonetheless, every time contact is made with a person in the community, there is an opportunity to demonstrate a high level of customer service that has become a tradition in the Surrey Fire Service. In many cases, Mr. Smith will see his vehicle leave the scene on the hook of a tow vehicle. For some involved in collisions, this will be the last time they see their cars – and their possessions inside. The Surrey Fire Service recognizes the stress that this places on those involved in collisions and has developed the MVI Kit to facilitate better customer service.

The need for the kit was identified by the firefighters as they made numerous trips back to the various compartments of the truck to grab the resources required to support the people involved in the collisions.

COMBINATION WRENCH

• Fits Standard Rocker Lug Hose ends from 1/1/2” (38mm) thru 4” (100mm)

• Fits Stortz Hose ends from 1-1/2” (38mm) thru 4” (100mm)

• Fits 1-1/4” Hydrant nut

• Tenzaloy Aluminum Alloy

• Weight: 15 oz.

• Length: 16 in.

MOUNTING BRACKET

• Mounts on the side of the Truck or inside a compartment

• Holds one or two wrenches

• Each wrench is securely held independently by a stainless steel spring clip

• Weight: 10 oz.

• 5” mounting hole centres for 3/8” bolts

Firefighters thought it would be more efficient and effective if all the items were placed into one handy kit that could be easily accessed and carried to the scene in one convenient waterproof and sturdy container.

The MVI Kit contains insurance cards, pens, large white plastic bags, an umbrella, and four rain ponchos.

The kits cost about $12 each. All that is required is a waterproof plastic container that will fit easily into an accessible compartment on board your fire trucks. Regular garbage bags purchased in bulk are sufficient for gathering the possessions of those involved in collisions; however, Surrey Fire Service opted to personalize the kits by upgrading to highly visible, white, heavy duty plastic bags that include a fire safety message, this increased the cost by 22 cents per bag. Surrey Fire decided to prominently display the department logo on the bags, along with the message “Install and Test Your Smoke Alarm,” to leave a lasting reminder of positive customer service.

An additional benefit of the white plastic bag is its high visibility on dark nights when those involved in collisions may be standing on the side of a road.

The dollar store is a good place to find items such as pens and umbrellas. The umbrellas must be sturdy, compact and, ideally, no more than $5 each. To lower the ongoing running costs, the firefighters are reminded not to give away the umbrellas as the intent is to cover the patient during care, or to cover a patient who is physically unable to pull a rain poncho over his or her head. Rain ponchos were purchased through a local fire-supply company for $2.50 each.

Every fire truck on the Surrey Fire Service now carries an MVI Kit. Firefighters are finding the kit handy and easy to use.

“Once the dust has settled at an incident you simply grab the kit, carry it with you, and pass out the right item to meet the customer’s needs,” says Surrey firefighter Brian Boles. “I like it because it saves searching for things because they’re all in one place.”

The MVI Kit is a useful and constructive tool to help those involved in an MVI, and it adds to the services already provided by Surrey’s customer service program, which was started in 2004 and has 10 members from various divisions within the department.

“I’ve actually left the scene of an accident and the victims were smiling because we took such good care of them,” said Capt. Dean Cleave.

The MVI Kit is a proactive example of the good service that is provided by Surrey’s fire department members.

“The MVI Kit is another opportunity to take our customer service to the next level,” said Assistant Chief Brian Woznikoski.

Firefighters are in a unique position to deliver service. The challenge is to provide a consistent, reliable message, and to co-ordinate the available resources for success on the job.

The MVI Kit is seen by firefighters as an opportunity to give a higher level of support when they are attending to the needs of Mr. Smith.

Acting Capt. Dave Baird has worked in the suppression division of the Surrey Fire Service for 21 years. He also instructs for the Justice Institute of BC. In 2012 and 2013 he was a committee member for the validation of the IFSTA Aerial Operators Handbook. He can be reached at DCBaird@surrey.ca

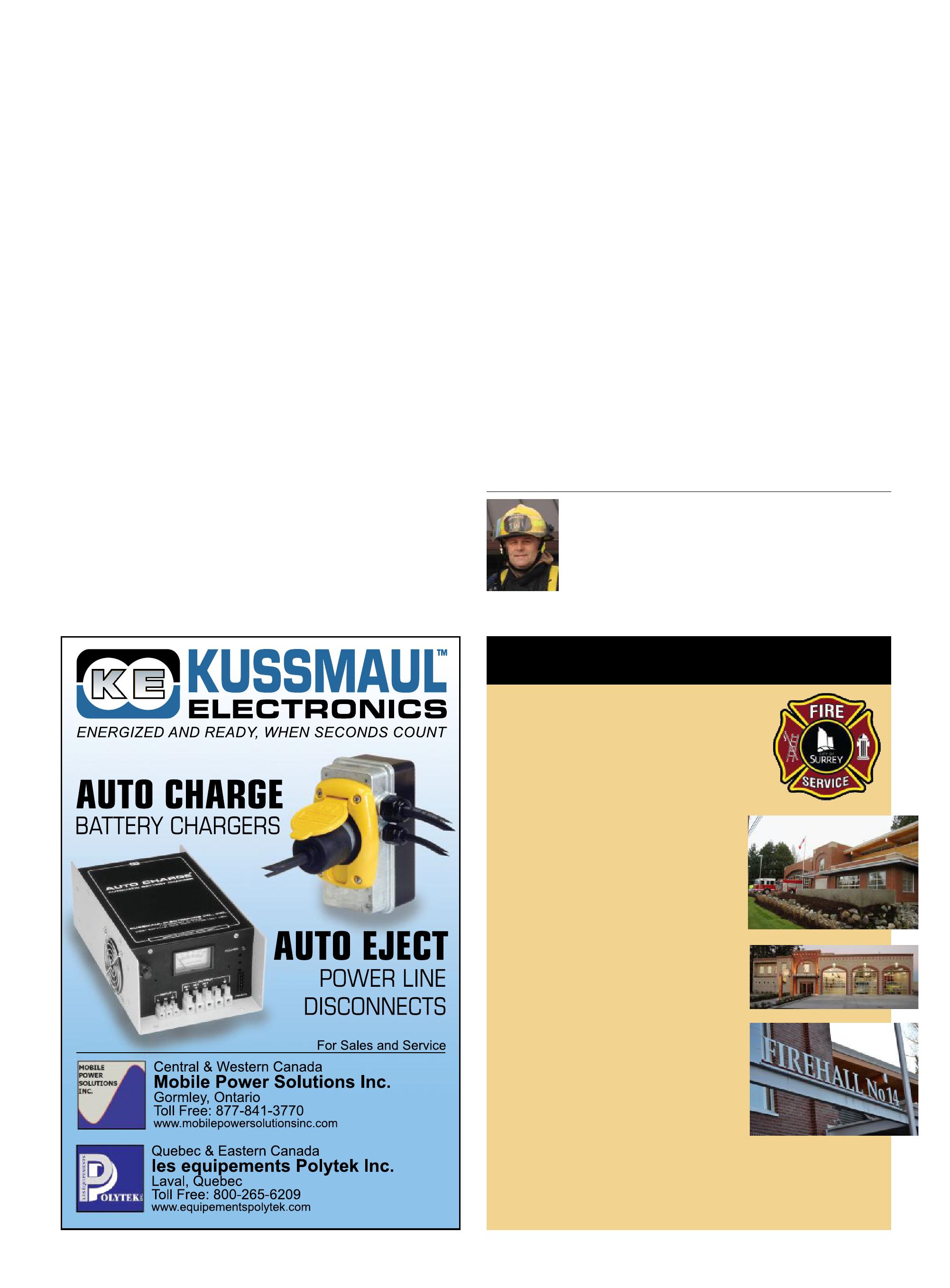

SURREy FIRE SERVICES

• Area served: 342 square kilometres

• Population: 492,160

• Fire halls: 17

• 342 career / 88 paid-on call firefighters, plus:

o 11 command staff

o 8 fire prevention officers

o 3 full time, 1 part time support staff

o 3 IT specialists

o 4 mechanical staff

o 16 full time, 6 part time dispatchers

• 30,146 calls in 2013

o medical 19,371

o mVIs 4,135

o Alarms 2,335

o miscellaneous calls 1,415

o Other fires 1,019

o Structure fires 702

o Burning complaints 532

o Hazardous materials response 415

o Vehicle fires 220

• Apparatus

o 16 Engines

o 1 aerial (100 feet)

o 5 quints (75 feet)

o 1 telesquirt (50 feet)

o 1 technical rescue

o 3 rescues

o 2 hazardous response units

o 1 command vehicle

o 1 mobile command post

o 1 mobile air unit

o 1 rehab/clothing vehicle

o 1 POD container vehicle

o 1 wildland interface response vehicle

By LES KARPLUK AND Ly LE q UAN

we have had the pleasure of writing leadership columns for Fire Fighting in Canada since 2010. All of our columns have focused on current issues or less-dramatic but just-as-relevant topics, such as succession planning or creating a positive culture in the fire hall. And, all of our columns have focused on one key theme that we both embraced the day we started writing: the true essence of leadership.

One of the greatest benefits of writing these columns is that, through our research and the feedback we receive from our peers, we have learned quite a bit about leadership. No one knows everything about leadership and team building, but together we have shared and learned from each other.

Through our columns and presentations we advocate that leadership is more than just wearing the white helmet or having more stripes on your shoulder than the rest of the department members; it’s about sharing what you have learned, yet at the same time, allowing others to make mistakes as they grow into their roles as leaders. Leadership is more than giving orders, it’s also about leaving a legacy that will continue to flourish long after you have left your organization.

For the fire chief, leadership is also about making sure the house is in order when you retire or leave for other opportunities. Ultimately, your goal should be to ensure that you leave the department in better shape than when you arrived and have things in order for the new fire chief. Do you have a strategic or master plan in place that can give the new fire chief some guidance as to what has been accomplished and what still needs to be addressed? Even if you don’t plan to leave the fire service in the very near future, do you have a formal plan in place to give your team and the community for which you work some indication of your future vision of the fire service? Remember, if it isn’t on paper, how can you measure your progress, or lack thereof, and how can others understand your future plans? The only way you can track

and demonstrate success with your programs and initiatives is to have a plan that identifies your baseline and sets the benchmarks, along with milestones to create check points for timely reviews.

Sooner or later, every firefighter or fire chief needs to retire and move into another phase of life. Though retirement is on the horizon (for Lyle), we plan to continue our work to promote leadership at all levels within the fire service. That might be through our column, at speaking engagements, by working with other fire departments in a consulting/supportive role or by publishing a book; that is what we see as our legacy.

Our overall goal is to ensure that our teachings and the lessons we have learned continue to flourish in the fire service. Based on this goal, we have been working on a book that we hope will offer some sage advice to present and future leaders within the fire service. We want it to be more than just another fire service book, so we have added some exercises through which you can write down and track your thoughts and future goals. As with anything in life, the results you achieve will be in direct proportion to the effort you put into your goals.

The only way you can track and demonstrate success with your programs and initiatives is to have a plan that identifies your baseline and sets the benchmarks . . . ‘‘ ’’

The book was expected to be released in March. Ultimately, we are hoping that the exercises in the book will lead readers to search out more information to become more aware of the key issues facing our present and future fire-service leaders.

Les Karpluk is the fire chief of the Prince Albert Fire Department in Saskatchewan. Lyle Quan is the fire chief of Waterloo Fire Rescue in Ontario. Both are graduates of the Lakeland College Bachelor of Business in Emergency Services program and Dalhousie University’s Fire Service Leadership and Administration program. Contact Les at l.karpluk@sasktel.net and Lyle at lyle.quan@waterloo.ca. Follow Les on twitter at @GenesisLes and Lyle at @LyleQuan

Years from now, it is your legacy that will dictate how others remember you. Will you be one of those fire chiefs who did what they could but got out when they reached the age of retirement? Or will you be remembered as the fire chief who truly cared for his or her fire department and the people in it? These are some major questions that you not only need to ask yourself, but you need to answer honestly.

We will leave you with this final thought: If there is no plan in place for your successors then you are setting them up to fail. This is not what true leaders would leave as their legacy.

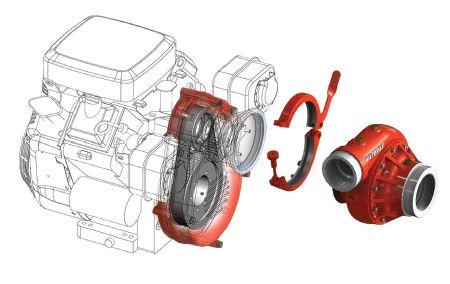

WATERAX , maker of high pressure, portable, centrifugal pumps is proud to introduce the new B2X Series, a full line of versatile mid-range portable pumps that produces an unmatched 215 US GPM (814 L/Min) @ 100 PSI (7 BAR), making it a weapon of choice for dual attack lines for municipal and wildland urban interface operations.

WATERAX ’s innovative pump end quick release clamp provides ease of maintenance without having to disassemble the complete unit, thus significantly reducing equipment downtime.

In addition, the B2X Series features a low maintenance drive belt system that provides efficient and dependable performance.

The WATERAX B2X comes in portable & vehicle mounted configurations and is powered by 4-stroke Briggs and Stratton Vanguard (18HP & 23HP) or Honda (21HP) engine.

By BruCE LakE

top : Gas monitors must be zeroed before each use to ensure accurate readings. However, firefighters must never zero the device in a contaminated environment, such as near the truck’s exhaust pipe.

r I ght: Seldom-used skills, such as those involved in the use of a gas monitor, can fade away with infrequent use. Develop a cheat sheet to keep near the monitor so that firefighters can quickly access key information when using the monitor.

the old saying, Jack of all trades, master of none, nicely sums up what it takes to be a 21st century firefighter. Today, fire-service personnel are expected to be competent in myriad skills but not necessarily outstanding in any particular one.

A skill that is often forgotten is gas monitoring. It is not uncommon for firstdue apparatuses to have a four-gas monitor on board. As the name implies, this gas detector has four sensors: a lower explosive limit (LEL) sensor, an oxygen (O2) sensor, a carbon monoxide (CO) sensor and a hydrogen sulfide (H2S) sensor. The LEL

sensor measures gases and vapours that burn, such as propane and natural gas. The O2 sensor measures oxygen enrichment or deficiency. The other sensors measure the toxic gases for which they are named. The technology found inside all brands and models of four-gas monitors is basically the same. As such, the fundamentals of using and maintaining a four-gas monitor are the same for all fire departments.

There is more to using a four-gas monitor than knowing how to turn it on and off. The fundamentals of using the device can be boiled down to three things: maintenance, initial procedures and interpretation of numbers.

Gas-monitor maintenance can be divided into two parts: serviceability check and calibration. A serviceability check is performed daily in station by the firefighters who use the device. The check includes inspecting the gas monitor for physical damage, ensuring that the batteries are fully charged, confirming that the sensors are working by turning on the device and, finally, noting that the device has been calibrated within the timeframe recommend by the manufacture. Most manufacturers recommend that the gas monitor be calibrated monthly and immediately after exposure to high concentrations of gas. This procedure is vital to ensure accurate sensor readings. Gas monitors that have exceeded the due date for calibration should be taken out of service until calibration can be completed. At Halifax Regional Fire & Emergency, gas monitors are calibrated by personnel at the hazmat station. Each time a monitor is calibrated, a new sticker is placed on the device with the date of calibration. This sticker enables anyone to quickly determine when the meter is next due for calibration.

Gas monitors should be calibrated each month or after exposure to high concentrations of gas. After calibrating the device, put a sticker on the monitor so that users can easily and quickly determine whether the device is due for calibration or is ready for use.

Assuming that the daily serviceability check has been completed, there are several steps that must be conducted immediately prior to using a four-gas monitor. These steps are necessary to ensure the accuracy

of gas readings. It takes a few minutes to perform these steps. Don’t get frustrated or skip a step, even if someone is urging you to hurry up.

1. Turn on the device. This can be done en route to the call, only if you can safety reach the gas monitor from your seat-belted position.

2. Zero the device. Two things happen during zeroing. First, the O2 sensor is calibrated to ambient air. During storage, the O2 sensor is constantly exposed to oxygen. This exposure reduces the sensor’s accuracy. Zeroing is necessary to ensure accurate O2 readings. It is vital that this step take place in fresh air. Zeroing in a contaminated environment, such as next to a vehicle’s idling exhaust pipe, will produce inaccurate readings. The second thing that happens during the zeroing process is the removal of any numbers that appear on the display screen after the device is first activated. During storage, all sensors are routinely exposed to miscellaneous gases, such as diesel exhaust. These gases will sometimes react with the sensors to produce a positive or negative number on the display screen. The zeroing process removes these numbers. After zeroing, any numbers that appear on the display screen will be the result of exposure to gases in the current environment and not from past storage or previously zeroing the meter in a contaminated environment.

3. Bump testing. During bump testing, all sensors are exposed to concentrations of gases that will activate sensor alarms. This step confirms that sensors will detect and react to the gas that the sensor was designed to detect. If your sensors do not respond, a full calibration should be conducted prior to using the monitor. Some departments choose not to bump test gas monitors. Others choose to bump test once a week or after each incident. Refer to your manufacturers’ instructions for options.

4. Clear the peaks. Many gas monitors will record the highest LEL, CO and H2S gas readings. They will also save the lowest O2 reading. These high/low readings, or peaks, should be cleared from the device’s memory before use. This is done to ensure that any recorded numbers are from the current incident, and not from a previous incident or the bump test.

Firefighter safety and the safety of the public are the main priorities at a gas incident. In order to determine whether conditions are safe or not, firefighters must be able to accurately interpret what the gas monitor is trying to tell them. This means understanding what those numbers on the display screen mean. What numbers are safe or unsafe? What are the department’s benchmark numbers for masking up, evacuating civilians, evacuating firefighters, doffing masks and civilian re-entry?

Below are some benchmark numbers used by Halifax Regional Fire & Emergency. The source of these numbers include manufacturers’ instructions, internal operating guidelines and provincial legislation. Your numbers may be different for a variety of reasons, such as using another brand of gas monitor, being mandated to follow different regulations or because your department approaches gas incidents in another manner. Always follow your fire department’s internal operating procedures, policies and guidelines. If your department has not established any benchmark numbers, now would be a good time to raise the issue with the appropriate officer.

LEL sensor:

• Unit of measurement: per cent of lower explosive limit

• Measurement range: zero to 100 per cent of LEL in increments of one per cent of LEL

• Response time after exposure to gas: greater than 35 seconds

• Don respiratory protection at one per cent of LEL

• Evacuate civilians at one per cent of LEL

• Evacuate firefighters at 10 per cent of LEL

• Less than 10 per cent O2 by volume will result in LEL readings less than actual gas concentrations

• If O2 readings are below 10 per cent by volume, determine LEL levels by dilution sampling

• Flashing display: OR stands for over range, meaning that flammable gas concentrations are above 100 per cent of LEL

• Blank display: flammable gas concentrations are above 100 per cent of LEL, or the LEL sensor is dead

• Doff respiratory protection and/or allow civilians to reoccupy a structure at zero per cent of LEL

• Oxygen-enriched readings greater than 23 per cent by volume will result in LEL readings that are higher than actual concentrations of gas

O2 sensor:

• Unit of measurement: per cent by volume

• Measurement range: zero to 30 per cent by volume, in increments of 0.1 per cent by volume

• Flashing display: OR stands for over range, meaning that O2 levels are above 30 per cent by volume

• Response time after exposure: greater than 10 seconds

• Normal O2 readings: 20.8 to 21 per cent by volume

• O2 deficient reading: less than 19.5 per cent by volume

• O2 enriched reading: greater than 23 per cent by volume

• Don respiratory protection at 19.5 per cent by volume

• Evacuate civilians at less than19.5 per cent or greater than 23 per cent by volume

• Evacuate firefighters at 23 per cent by volume or greater

• High humidity or the presence of an oxygen-displacing gas can cause O2 readings to drop

CO sensor:

• Unit of measurement: parts per million (ppm)

• Measurement range: zero to 1,500 ppm, in increments of one ppm

• Flashing display: OR stands for over range, meaning that CO levels are above 1,500 ppm

• Response time after exposure: greater than 50 seconds

• Don respiratory protection at 25 ppm

• Evacuate civilians at 25 ppm

• Allow civilians to reoccupy a structure at zero ppm

• Recharging batteries, welding, home brewing, dry cleaning chemicals and diesel exhaust will cause false CO readings

H2S sensor:

• Unit of measurement: parts per million (ppm)

• Measurement range: zero to 500 ppm, in increments of 0.1 ppm

• Flashing display: OR stands for over range, meaning that H2S levels are above 500 ppm

• Response time after exposure: greater than 50 seconds

• Don respiratory protection at 10 ppm

• Evacuate civilians at less than 10 ppm

• Allow civilians to reoccupy a structure at zero ppm

• Gas sources that will cause false H2S reading: water treatment facility, combustion of coal or petroleum, incomplete combustion, and pulp mills

I have by no means exhausted all the topics you may wish to cover during a review of gas monitoring. Additional topics may include vapour density, sampling pumps, tubing, accessories and correction factors.