International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Veeshal Rathod V1 , Naveen R2 , Vallabha C D3 , Pavan4

1M Tech Scholar, Dr Ambedkar Institute of Technology, Bengaluru

2Assistant Professor, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Dr Ambedkar Institute of Technology, Bengaluru

3M Tech Scholar, Dr Ambedkar Institute of Technology, Bengaluru

4M Tech Scholar, Dr Ambedkar Institute of Technology, Bengaluru

Abstract - Monolithic construction systems cast-in-place concrete, tunnel formwork, insulating concrete forms (ICF) and related continuous wall–slab systems are increasingly promotedforrapid,durablehousinginhazard-proneregions. This review synthesizes reviewed literature on the physical vulnerabilityofbuildingstolandslides,structuralandlifecycle cost factors for monolithic and traditional framed systems, and practical implications for design, siting and post-event losses.Evidenceshowsthatbuildingvulnerabilitytolandslides depends strongly on foundation depth, building footprint/orientation and soil–structure interaction; monolithicRC/ICFsystemstendtoprovidesuperiorcontinuity, higher out-of-plane strength and reduced maintenance demands compared with conventional framed or masonry stock,withlife-cyclebenefitsinenergyanddurabilityreported in several journal studies. However, site-specific landslide mechanics, debris flow vs slow-moving slides, and local construction supply chains largely determine whether monolithic systems are cost-efficient. Gaps remain in quantitative, landslide-specific cost–benefit studies; we proposestandardized assessment frameworks thatintegrate fragility functions with life-cycle cost modelling.

Key Words: Monolithic construction1, Landslide vulnerability2,costanalysis3,Framedstructures4

Landslides and slope failures constitute a major driver of building damage in hilly and mountainous regions worldwide. Beyond immediate repair costs, repeated or progressive damage increases life-cycle costs, hinders recovery and shifts insurance and social burdens. Practitionersandpolicymakersthereforeseekconstruction systems that minimize both expected direct losses (repair/replacement) and long-term ownership costs (maintenance, energy, insurance). Monolithic building systems where walls, floors and structural elements are cast or constructed as continuous units are frequently proposed as more robust, faster and sometimes cheaper alternativestotraditionalreinforced-concrete(RC)framed structuresortimber/steelframedhousesinhazardzones. Yet, the comparative evidence specifically addressing landslide-prone contexts is fragmented across disciplines: geotechnicalengineering(landslidemechanics),structural

engineering (fragility/strength), and building economics (construction and life-cycle cost). This review collates reviewed journal findings to evaluate cost efficiency of monolithicvsframedsystemsinlandslidecontextsandto identifyresearchgapsforfuturepractice[1,2].

Theobjectivesofthisreviewareto:

1. Summarize the state of knowledge on building vulnerability to landslides and the structural behaviorsthatmediatedamage[1,2].

2. Synthesize journal evidence on construction, operational and life-cycle costs for monolithic systemsandforconventionalframedstructures[3, 5,6]

3. Assesswhethermonolithicsystemsprovidenetcost advantages in landslide-prone areas, under what conditions,andwhereevidenceislacking.

4. Propose a standardized methodology for comparativecost–vulnerabilityassessmentstoguide futurestudiesandpractitioners.

Databases and sources searched: ScienceDirect, MDPI, Copernicus(NHESS),Elsevierjournals(Energy&Buildings), and multidisciplinary indexes via publisher pages and abstracts.Searchesusedkeywordsandcombinationssuchas “monolithicstructurecost”,“tunnelformworkcostframedvs monolithic”,“insulatingconcreteformlifecycleassessment”, “building vulnerability landslides”, “fragility landslide buildings”,and“costefficiencymonolithicconstruction”[1, 3,4].

Inclusion criteria: peer-reviewed journal articles (not conference-onlynon-peerpublications)addressing:building vulnerability to landslides; structural behavior of monolithic/ICF/continuousRCsystems;comparativecost, life-cycle assessment (LCA) or energy-cost studies comparing monolithic systems and framed structures. Publications from 2000–2025 were prioritized; seminal earlierworkwasincludedwhererelevant.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Exclusioncriteria:non-peersources(industrywhitepapers withoutpeerreview),purelyanecdotalreports,andjournal content that did not present empirical, experimental, analyticalorLCAdata.

The literature emphasizes that building damage from landslides arises via multiple interacting mechanisms: (a) lateralthrustandimpact(rapidslidesanddebrisflows),(b) differentialsettlementandtilt(slow-movingslides),and(c) scour or foundation undermining. Accordingly, fragility differsmarkedlybetweendebris-flow-pronesitesandslowmovingtranslationalslides.Mechanics-basedstudiesshow that building geometry (length vs width relative to slide direction), foundation depth and stiffness of the soil–structure interface are dominant predictors of damage; notably,longerbuildingaxesperpendiculartoslidedirection increase vulnerability, while deeper foundations reduce it. These mechanics provide the physical linkage between structural form (monolithic vs framed) and expected performanceunderlandslideloading[1].

Empirical and modeling studies have developed physical vulnerability curves linking landslide intensity metrics (displacement, thrust, impact energy) to damage states; thesecurvesformthebasisforprobabilisticlossestimation. Theconstructionsysteminfluencestwokeycomponentsof the vulnerability function: (i) the threshold at which structuralintegrityislost(monolithiccontinuityandhigher shearcapacityoftenraisethisthreshold),and(ii)thepostevent repair cost associated with similar damage states (repairabilityandcostofreplacementelements)[1,7]

2.1 Properties of monolithic systems relevant to landslides

Monolithic systems including cast-in-place RC with continuous diaphragms, tunnel formwork multi-storey monolithicunits,andInsulatingConcreteForms(ICF)share featuresthatinfluencelandslideresilience:

Structuralcontinuity anddiaphragm action: Continuous wall–slabintegrationdistributeslateralloadsandreduces concentration of stress at discrete connections (beams–columns),improvingout-of-planeresistancetolateralthrust. This continuity can reduce catastrophic collapse under distributedlateralslidingthrust.[5]

Out-of-plane wall stiffness and shear capacity: Solid concretewalls(monolithic)presenthighershearandout-ofplanecapacitythanframedsystemsrelyingoninfillwalls; thisisbeneficialunderimpact/thrustloading.[3]

Simplified foundations and reduced number of critical joints: Fewer discrete structural joints can reduce local differential movement amplification, though the entire

monolithic load path may transfer higher demand to foundations making foundation design and soil-structure interactioncritical[1].

Durability, maintenance and thermal performance: StudiesofICFandmonolithicwallsreportimprovedthermal performance and reduced maintenance over framed/masonry walls; life-cycle assessments often show operational energy savings that partially offset slightly higherinitialembodiedimpactsinsomecontexts[3,6]

These structural and operational attributes suggest monolithic systems can alter both the probability and severityoflandslide-induceddamageandthelife-cyclecost profile. However, the magnitude of the effect is site- and hazard-specific.

Journalstudiescomparingconstructioncostsofmonolithic vs framed systems present mixed results depending on region,Labourrates,andsystemspecifics:

ExperimentalandcomparativecasestudiesofICFandother monolithic options often report initial construction cost premiums in the range of roughly 0–10% relative to standard framed or masonry methods in regions with established supplychains, whileinsomecases monolithic tunnel-formsystemshavebeenshowntoreduceLabourand formwork time and therefore reduce total costs [5, 6] Reported cost advantages relate to reduced Labour time, simplerformworkcycles(tunnelform),andeliminationof secondaryfinishes.

Where monolithic systems require specialized materials (e.g., EPS ICF blocks) or skilled crews, initial costs can be higher. Conversely, pre-fabrication and repetitive tunnel form production in multi-storey projects can deliver economies of scale, often making monolithic approaches cost-competitiveorcheaperthanframedRCwithmasonry infills.

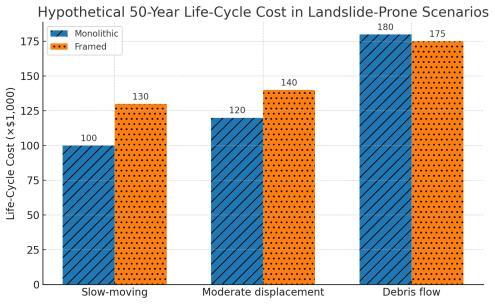

Chart -1:Hypotheticalcomparisonof50-yearlife-cycle costsformonolithicandframedstructuresunderdifferent landslidescenarios

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Repaircostsfollowinglandslidedamagedependondamage mode:tiltandsettlementvsimpactrupture.

For slow-moving landslides producing progressive settlement, framed structures with discrete connections, non-ductile infills and shallow strip foundations can experience concentrated damage to non-structural componentsthatiscostlytorectifyrepeatedly.Monolithic continuous systems may better tolerate moderate differential movements before major cracking, reducing cumulative repair frequency and cost. Mechanics-based assessments indicate foundation depth and stiffness are primaryvariables;however,whenfoundationundermining orhighimpactforcesoccur,nosystemisimmuneandrepair costsscalewiththeextentoffoundationandsuperstructure damage.

FragilitystudiesappliedtomonolithicRCremainlimitedfor landslide loading; however, earthquake fragility literature (analogous in some structural response aspects) suggests monolithic continuity reduces collapse risk and extensive repairneedscomparedtopoorlydetailedframedsystems. Extrapolatingcautiously,thisimplieslowerexpectedposteventreplacementcostundermanylandslidescenarios,but theeffectsizeremainstobepreciselyquantifiedfordifferent slidetypes[1,7].

Life-cycleassessments(LCA)comparingICFandtraditional framingreport:

Operational energy savings in ICF and well-insulated monolithic walls (due to thermal mass and continuous insulation) that reduce heating/cooling demand, contributing to lower operational cost and sometimes offsetting slightly higher embodied costs over a 20-to-50yearhorizonintemperateclimates[3,6].

Reducedmaintenanceneeds(lessfinishing,fewerjointsand penetrations) also contribute to lower life-cycle cost for monolithic systems in several published LCAs. The magnitudedependsonclimate,materiallongevityandlocal maintenancepractice.

Given the evidence, practitioners can adopt the following site-specificdecisionheuristics:

Rapid debris-flow/high-impact zones: When impact energy and burial depth are the dominant threats (debris flows,rapidtranslationalslides),structuralcontinuityalone doesnotguaranteesurvivability;instead,siting,protective works (deflection berms, check dams), and elevating/retrofitting foundations are primary loss-

reductionmeasures.Monolithicsystemsmayreducerepair costspost-eventonlyifthestructureisnotfullyburiedor catastrophicallyimpacted[2,7].

Slow-moving displacement zones: For progressive landslides producing differential settlement and tilt, monolithiccontinuoussystemswithappropriatelydetailed foundations (deepened or stiffened) can reduce the frequency and severity of reparable damage by better distributing deformation and avoiding concentration at discretejointsleadingtofavorablelife-cyclecostoutcomes [1].

Where Labour costs dominate: In areas where skilled Labour is scarce or expensive, monolithic methods that reduceconstructiontime(tunnelformwork,modularICF) can deliver lower total construction cost and earlier occupancy, improving economic feasibility. Conversely, if materials for monolithic systems are expensive to import, conventionallocalframedsystemsmayremaincheaper[3, 5].

Despite promising mechanistic and LCA evidence, clear quantitativestudiesthatintegratelandslide-specificfragility curveswithlife-cyclecostmodelsformonolithicvsframed systemsarescarce.Keygapsinclude:

Fragilityfunctionsfor monolithic systemsunderlandslide loading:Mostpublishedfragilityworkfocusesonmasonry and framed systems or on seismic loads; analogous, peerreviewedfragilitycurvesformonolithic/ICFbuildingsunder landslidethrust,impactandprogressivedisplacementare limited[7].

Integratedprobabilisticcost–vulnerabilitystudies:Thereisa shortage of probabilistic analyses that combine spatial landslide hazard models with building resistance metrics andlife-cyclecostoutcomestoproduceexpected-lossmaps or cost-optimal mitigation strategies. Recent machinelearning vulnerability mapping advances offer an opportunitytolinkbuildingresistanceindicestoeconomic outcomesatscale[4].

Context-sensitiveLCAinlow-income/high-hazardsettings: Existing LCA studies often reflect temperate, developedcountry contexts. Studies that incorporate constrained supplychains,informalbuildingpractices,anddifferential Labour costs in developing, landslide-prone regions are neededtorenderconclusionsactionableforpolicy[3,6].

To resolve current uncertainty and enable robust policy advice,weproposeastandardizedassessmentframework combininghazard,vulnerabilityandcostmodelling:

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Hazardcharacterization:Maplandslidetypes(debrisflow, rapid translational, slow creep) and intensities (impact energy, displacement rate) using remote sensing, slope modelsandfieldinventories[4].

Building resistance metrics: Define structural resistance indicesformonolithicandframedprototypes(e.g.,critical thrustatonsetofsignificantdamage,allowabledifferential settlement, out-of-plane wall capacity). Obtain these via experimental testing, FE simulation and analogy with seismicfragilitywherejustified[1].

Fragilityfunctiondevelopment:Translateresistancemetrics into fragility curves (probability of damage states conditional on hazard intensity) for each prototype and retrofitoption[7].

Economic module: Calculate initial construction cost (material, Labour, time), expected annualized repair/replacementcostsusingfragility×hazardfrequency, and operational energy/maintenance costs (LCA perspective).Discountfuturecoststopresentvaluetoobtain net present value (NPV) and life-cycle cost (LCC) comparisons[5,6].

Decision rules: For each location and prototype, compute expectedLCCandexpectedannualizedloss;determinethe cost-efficientoptionsubjecttoperformanceobjectives(e.g., acceptableprobabilityofexceedanceofcatastrophicloss). Conduct sensitivity analyses on Labour rates, material transportcosts,hazardfrequencyanddiscountrate.

Applyingthisframeworkacrossrepresentativesiteswould yield generalizable guidance on when monolithic systems areeconomicallypreferableinlandslidecontexts.

Synthesisofreviewedjournalliteratureindicates:

Monolithic systems (ICF, tunnel formwork, cast-in-place continuous RC)havestructural andoperational attributes continuity,out-of-planestrength,thermalperformanceand reduced maintenance that can reduce life-cycle costs and expected post-landslide losses versus some conventional framed or masonry systems, particularly in slow-moving landslide contexts and in high-Labour-cost or repetitive multi-unitprojects[1,3,5,7].

Therelativecostefficiencyishighlycontextdependent.For high-impactdebris-flowzones,structuralformisnecessary but insufficient; siting and protective works dominate expectedlosses.Forslow-movingslides,monolithicsystems combined with foundation adaptation often yield lower expectedrepaircosts,givingafavorablelife-cycleoutcome.

Evidence gaps remain, notably the lack of peer-reviewed fragility curves for monolithic systems under landslide

loading and limited probabilistic LCC studies integrating spatial hazard models. Addressing these gaps will require cross-disciplinary experiments, field monitoring, and standardizedLCCprotocolsforhazard-specificcontexts[2, 4,7].

Practical recommendations for practitioners and policy makers:

Inslow-movinglandslidezones,favourmonolithicwall-andslab solutions with appropriately deep or stiffened foundationswherelocalsupplychainssupportcost-effective monolithicconstruction.

In debris-flow/high-impact corridors, prioritize nonstructuralmitigation(avoidance,diversionstructures,early warning)andconsidermonolithicsystemsonlyifcombined withprotectiveworks.

Forhousingprogramswithrepetitivelayouts(multi-storey socialhousing),evaluatetunnelformmonolithicsystemsfor potentialtimeandcostsavings.

Commission site-specific probabilistic assessments that combine local hazard maps, building prototypes and lifecyclecostmodelsbeforeadoptinglarge-scalepolicyshifts.

Theauthorswouldliketothank Er.NageshPuttaswamy for his valuable guidance, constructive feedback, and support throughoutthedevelopmentofthiswork.Hisinsightsand encouragementgreatlycontributedtoshapingthedirection andqualityofthisreview.

[1] Q.Chen,L.Chen,L.Gui,K.Yin,D.P.Shrestha,J.Du,andX. Cao, “Assessment of the physical vulnerability of buildingsaffectedbyslow-movinglandslides,” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, vol. 20, pp. 2547–2565,2020,doi:10.5194/nhess-20-2547-2020.

[2] P. F. Saba, M. Rossi, and L. Bianchi, “Vulnerability of buildingstolandslides:Thestateoftheartandfuture needs,” Earth-Science Reviews, vol. 240, 104360, Mar. 2023,doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104360.

[3] M.Al-Ghobari,S.A.Al-Sanea,andA.M.Zeyad,“Thermal and structural performances of screen grid insulated concrete forms (SGICFs) using experimental testing,” Buildings, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 2599, Sept. 2024, doi:10.3390/buildings14092599.

[4] Y. Zhang, J. Liu, Q. Wei, X. Li, and F. Wang, “Building vulnerability to landslides: Broad-scale assessment in XinxingCounty,China,” Sensors,vol.24,no.13,p.4366, Jul.2024,doi:10.3390/s24134366.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

[5] A. S. Hermansson, J. Myhren, and F. Hagentoft, “Structure,energyandcostefficiencyevaluationofthree different building systems,” Energy and Buildings, vol. 81, pp. 203–210, Oct. 2014, doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.06.032.

[6] J.Kosny,J.Christian,andD.Yarbrough,“Comparativelife cycle assessments of insulating concrete forms and traditionalframing,” JournalofGreenBuilding,vol.9,no. 4,pp.123–140,2014,doi:10.3992/jgb.9.4.123.

[7] H.Wang,L.Chen,andK.Yin,“Probabilisticvulnerability evaluation of buildings under landslide loading,” Engineering Structures, vol. 302, 116876, Feb. 2025, doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.116876.