International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Korri Anirudh Yadav1, Palthya Srinivas Naik2

1Master’s student, Urban planning Department, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi

Address: 4, Block-B, Indraprastha Estate, Near ITO, New Delhi – 110002, India

2 Assistant Professor -Urban planning Department, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi

Address: 4, Block-B, Indraprastha Estate, Near ITO, New Delhi – 110002, India

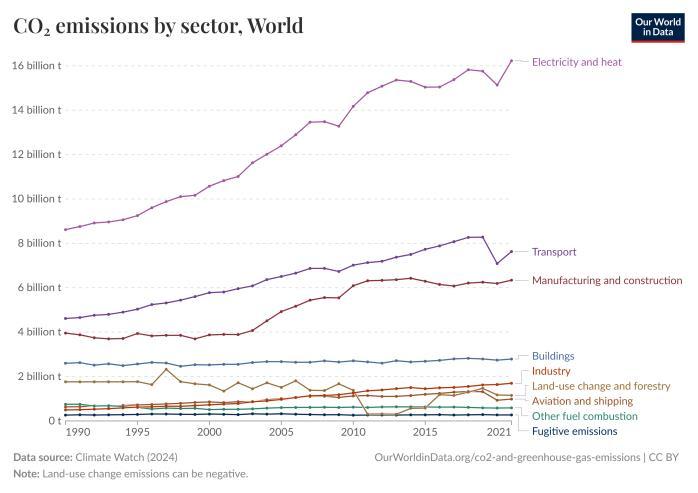

Abstract - Anthropogenic CO2 emissions remain near record highs, with fossil-fuel-and-cement emissions estimated at 36.1±0.3GtCO2(1 gigatonne (Gt) = 1 billion metric tonnes.) in 2022 and total anthropogenic emissions (fossil +land-use change) around 40.7±3.2 GtCO2, while atmospheric CO2 averaged 417 ppm in 2022 and rose to 419 ppm in 2023 (51% above pre-industrial) (Friedlingstein et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023; NOAA, 2024). Emerging analysesindicate theterrestrial carbon sink weakened markedly in 2023, contributing to an anomalously high atmospheric CO2 growth rate and underscoring the vulnerability of nature-based sequestration under compound climate stressors (Yin et al., 2024; Bastos et al., 2024). Rapid urbanization amplifies consumption-based emissions and land-use pressures,yeturbanforestscandeliver carbon sequestration alongside heat mitigation, air-quality improvement, and public-health co-benefits if survival and growth are verified over time (MEA, 2005; Nowak et al., 2013; IPCC, 2022). However, many planting programs lack robust, long-term monitoring, creating a gap between pledges and realized removals (Seddon et al., 2020). An AI-enabled framework integrating satellite remote sensing, in-situ inventories, and near-real-time emissions datasets can be a potential in conducting city-scaletreecensus,trackhealthand mortality, and quantify area-level carbon sequestration capacity with uncertainties, enablingtransparentnet-balance accounting (GRACED, 2021; Tongetal.,2023;Thompsonetal., 2023). The framework is globally scalable and directly supports urban planning, capacity building, program verification, and adaptive management in rapidly urbanizing regions.

Key Words: AI-enabledcarbonsequestration,Urbancarbon accounting, Machine learning for ecology, Environmental sustainability

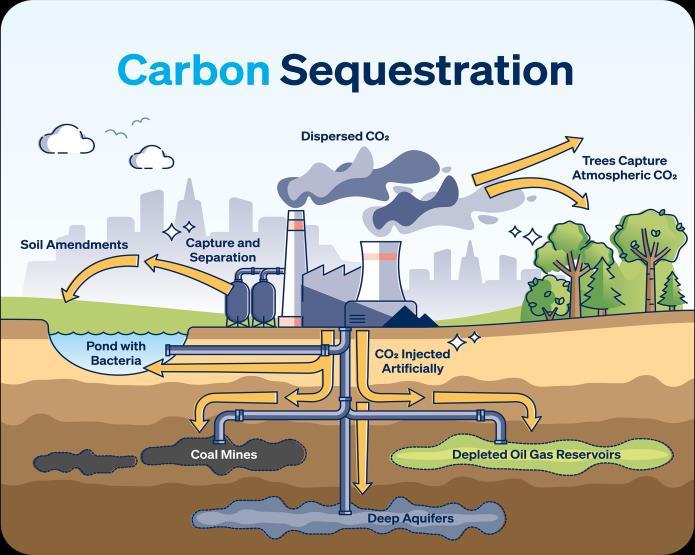

Carbon sequestration refers to the suite of biological, geological, oceanic, and product pathways that remove carbondioxide(CO2)fromtheatmosphereandstoreitover climate-relevanttimescales,therebyreducingatmospheric concentrationsandmoderatingwarmingtrajectories(IPCC framing as reflected in the Global Carbon Budget series) (Friedlingstein et al., 2023; Friedlingstein et al., 2024). In 2023,totalanthropogenicCO2emissionswereestimatedat 11.1±0.9GtC/yr(≈40.6±3.2GtCO2/yr),withfossilemissions

at10.1±0.5GtC/yrandland-usechangeat1.0±0.7GtC/yr, while the atmosphere accumulated 5.9±0.2 GtC (2.79±0.1 ppm), the ocean absorbed 2.9±0.4 GtC, and land took up 2.3±1.0 GtC, yielding an average atmospheric CO2 concentrationof419.31±0.1ppm(about52%abovethepreindustrial 278 ppm) (Friedlingstein et al., 2024). These numbers underscore why global leaders prioritize sequestration, even as ocean and land sinks remove a substantial share of annual emissions, atmospheric CO2 continuestorise,tighteningtheremainingcarbonbudgetfor 1.5–2°C and elevating climate risks across sectors and regions (Friedlingstein et al., 2023; Friedlingstein et al., 2024).Global warming is advancing in lockstep with cumulative emissions, and recent carbon-cycle dynamics highlight growing hazards, in 2023 the atmospheric CO2 growth rate jumped to a record-high 3.37±0.11 ppm at MaunaLoa,86%above2022despiteonlyamodest+0.6% increaseinfossilCO2,drivenprimarilybyanunprecedented weakeningofthelandcarbonsinkto0.44±0.21GtC/yr,with major anomalies in the Amazon, Canada (fires), and SoutheastAsia(ElNiñoinfluence)(Bastosetal.,2024;Yinet al., 2024). A low-latency synthesis through mid-2024 confirmsthepersistenceofanomalies,attributingthe2023–2024 spike in atmospheric growth chiefly to a approx. of 2.24GtC/yr reduction in the net landsink duringEl Niño, concentrated in tropical regions (Amazon, Central Africa, SoutheastAsia),withtheyearJuly2023July2024postinga record 3.66±0.09 ppm/yr growth since 1979 (Yin et al., 2025;Bastosetal.,2024).

Figure 1: CarbonSequestration, Source:Battenfield,R.and Abernathy, B. (n.d.) Carbon Sequestration 101: UnderstandingtheRisksandFindingInsuranceSolutions. Forpolicymakersandmarkets,thisvolatilitymeansnaturebased sequestration is indispensable but cannot be presumed stable without robust monitoring, risk buffers, andadaptationmeasures(Bastosetal.,2024;Friedlingstein et al., 2024).From an industrial and financial perspective, sequestrationmattersbecauseheavy-emittingsectorssteel, cement, chemicals, refining, and other energy-intensive industriesfacerisingnet-zerocommitments,carbonpricing, disclosure mandates, and supply-chain pressures, making credible emissions reductions and removals a strategic necessity (Liu et al., 2023). Global fossil-fuel-and-cement CO2reached36.1GtCO2in2022,consuminganestimated 13–36%oftheremaining1.5°Ccarbonbudgetinthatyear alone, implying that without rapid mitigation and scaled removals, the 1.5°C consistent budget could be exhausted withinafewyearsoncurrenttrajectories(Liuetal.,2023). CCUS deployment is accelerating but remains far from offsetting present emission scales; annual reviews show progress in projects and technology readiness, yet emphasize the need for parallel nature-based and engineeredremovals,rigorousMRV(Monitoring-ReportingVerification),andintegrationwithbroaderdecarbonization (Zhang et al., 2024). For large capital-intensive emitters, high-integritysequestration whetherviaforests,soils,blue carbon,biochar,enhancedweathering,BECCS,orgeological storagecanhedgetransitionrisks,reducecompliancecosts over time, open access to green finance, and support customer demand for low-carbon products, provided outcomes are measured and verified with transparency (Zhangetal.,2024;Liuetal.,2023).Urbanizationamplifies theurgencyandopportunity:citiesconcentrateenergyuse, materials,andconsumption-basedemissions,whileurban greeningcandeliverquantifiablecarbonremovalsalongside heatmitigation,air-qualitygains,andresilienceco-benefitsif survivalandgrowtharesustained(Liuetal.,2023).

Integrating city-scale sequestration with near-real-time, gridded emissions data enables net-balance tracking visualizing whether local removals are keeping pace with localemissions,andguidingwheretoinvestformaximum climateandpublic-healthimpact(Jiangetal.,2021).Daily, high-resolutionemissionsproductslikeGRACEDandCarbon Monitor are already used for situational awareness and policy applications, allowing decision-makers to connect sequestration outcomes with emissions dynamics in near real time (Jiang et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023).Climate risks linkedtowarminglikeheatextremes,drought,wildfire,and flood-related disruptions are increasingly visible in the carbonbudgetrecordthroughvariabilityofsinksandspikes in fire emissions; the 2023 Canadian fires contributed an estimated 0.58±0.10 GtC/yr to the budget anomaly, illustrating how hazards can erase years of accumulated biogeniccarboninasingleseason(Bastosetal.,2024).The Global Carbon Budget 2024 further documents that atmospheric CO2 rose by 2.79±0.1 ppm in 2023 to 419.31±0.1 ppm and is preliminarily estimated to have reached to an approximate of 422.45 ppm in 2024 (+2.87 ppm),reinforcingtheneedforbothrapidemissionscutsand resilient sinks that can withstand climate volatility (Friedlingsteinetal.,2024).Insum,carbonsequestrationis central to stabilizing climate, but it must be made measurable, verifiable, and resilient to be relied upon by governments,investors,andindustryatscale(Friedlingstein etal.,2024;Bastosetal.,2024).

CarbonsequestrationistheprocessofremovingCO2from the atmosphere and storing it in biomass, soils, oceans, geologicalformations,orlong‑livedproducts,while“carbon sinks”aretheaccountingcategoriesunderUNFCCCwhere these removals are measured and reported; in practice, global climate governance used “sinks” to operationalize sequestration through rules, MRV(Monitoring-Reporting-

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Verification),andmarkets.Since1992,successivemilestones embedded sequestration more deeply into policy: the UNFCCC(1992)recognizedsinks;theKyotoProtocol(1997) brought land-use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) intocomplianceaccounting;theMarrakeshAccords(2001–2002) set detailed LULUCF rules; Kyoto’s entry into force (2005) enabled afforestation/reforestation crediting and MRV; the Bali Action Plan (2007) launched REDD+; the Cancun Agreements (2010) added REDD+ safeguards and MRV(Monitoring-Reporting-Verification); the Warsaw Framework (2013) completed REDD+ with results-based payments; the Paris Agreement (2015) Article 5 called to conserve and enhance sinks, mainstreaming both naturebased and engineered removals; the Katowice Rulebook (2018) standardized transparency for LULUCF; Glasgow (2021) advanced Article 6 market rules stressing highintegrity removals; Sharm el-Sheikh (2022) progressed implementation and LT-LEDS with quantified sinks; and Dubai’sfirstGlobalStocktake(2023)reaffirmedtheneedfor high-integrityremovalsalongsidedeepemissionscuts,while parallel CCS/CCUS initiatives (2000s–present) scale geologicalstoragewithinnationalnet‑zerostrategies.This sequenceshowshowinternationalagreementsmovedfrom acknowledging sinks to governing measurable, verifiable carbonsequestrationacrosslandandengineeredpathways, settingthecontextforyourtable.

Table-1: ShowingtheCarbonsequestrationoutcomesin varioussummits

Year Summit/Instrument Outcome

1992 UNFCCC (Rio Earth Summit)

Establishedglobalframework tostabilizeGHGs;recognized the role of sinks and reservoirs.

1997 KyotoProtocol(COP3) Brought LULUCF into compliance accounting; enabled afforestation/reforestation; raised permanence/leakage/MRV issues.

2001–2002 Marrakesh Accords (COP7)

DefinedoperationalLULUCF rules (Articles 3.3/3.4) for forestcarbonaccounting.

2005 Kyotoentersintoforce Launched practical sink crediting via LULUCF and CDMA/Rprojects;expanded land-sectorMRVcapacity.

2007 Bali Action Plan (COP13)

2010 Cancun Agreements (COP16)

IntroducedREDD+pathway to reduce deforestation/degradation and enhance forest carbon stocks.

Established REDD+ safeguards,referencelevels, andMRVguidance.

2013 WarsawFrameworkfor REDD+(COP19) CompletedREDD+rulebook; enabled results-based paymentsforverifiedforest carbon.

2015 Paris Agreement (COP21)

2018 Katowice Rulebook (COP24)

Article 5 called to conserve/enhance sinks; mainstreamedbiologicaland engineered removals in NDCs/LTS.

Standardized transparency and reporting for LULUCF underParis.

2021 Glasgow Climate Pact (COP26) Advanced Article 6 market rules; emphasized highintegrity nature-based removals.

2022 Sharm el-Sheikh (COP27) Continued Article 6 implementation; more LTLEDS with quantified sinks/removals.

2023 Dubai(COP28) – First GlobalStocktake

Reaffirmed need for highintegrityremovalsalongside deep cuts; highlighted forests/land and CCS in transitions.

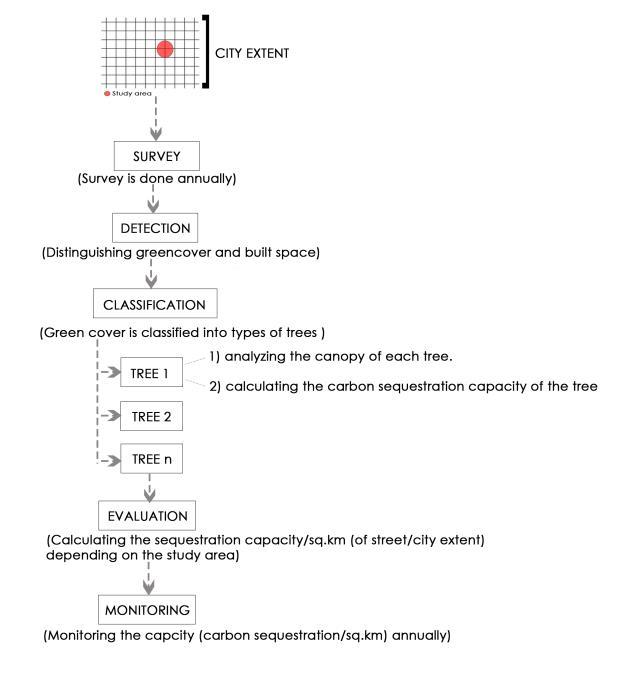

Whenlookingatapatchof“greencover”insatelliteoraerial imagery,itisnotobviouswhetheritisatreecrown,shrub, grass,orevenalgaeonwaterandwithoutknowingtheobject type and its structure, estimating how much carbon it can capture is unreliable (misclassification propagates large errorsintobiomassandsequestrationestimates)(Weinstein et al., 2020; Foster et al., 2022). Artificial intelligence overcomesthisbylearningtodetectanddelineateindividual treecrowns,classifyspeciesorfunctionalgroups,andtrack structuralchangeovertime,scalingrobustlyfromstreettrees to national inventories with quantified uncertainty (Weinsteinetal.,2020;Chaveetal.,2014).

Emphasized outcome: From green pixels to trees with attributes.AIusesdeeplearningonhigh-resolutionimagery (satellite, aerial, UAV) to delineate individual tree crowns, counttrees,estimatecrownarea/heightproxies,andclassify speciesgroups,enablingreliablebiomassinputsacrossurban andperi-urbanlandscapes(Weinsteinetal.,2020;Wegneret al.,2016).

Data fusion and scaling: Integrates multispectral imagery withLiDARandfieldplotstocalibrateallometryandreduce

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

biases from overlapping canopies and understory; scales from neighborhood to city and national levels while maintaininguncertaintybounds(Chaveetal.,2014;Fosteret al.,2022).

Healthandrisksurveillance:Time-seriesanomalydetection flags die-off, drought stress, pests, or post-planting maintenance failures, protecting permanence by enabling timely interventions; urban trees and trees outside forestsoften undercounted are brought into inventories (Bastosetal.,2024;Yinetal.,2024).

3.2 Reporting: Convert observations into credible carbon and co-benefit metrics

Emphasized outcome: Transparent biomass-to-carbon accounting. AI pipelines convert crown metrics to aboveground biomass using species/site-aware allometry, then to carbon and CO2 with uncertainty propagation suitablefordashboards,credits,anddisclosures(Chaveetal., 2014;Fosteretal.,2022).

Net-balancecontext:PairAI-estimatedremovalswithdaily, griddedemissions(e.g.,GRACED;CarbonMonitor)toreport ward/district net carbon balance, trendlines, and scenario progressforrapidlyurbanizingregions(Jiangetal.,2021;Liu etal.,2023).

Policy and finance ready outputs: Generate standardized MRV(Monitoring-Reporting-Verification)summariessurvival rates,annualincrements,mortalitylosses,andriskbuffersfor municipal programs, investors, and corporate reporting alignedwithtighteningclimatetargetsandcarbonbudgets (IPCC,2022;Friedlingsteinetal.,2023).

3.3 Verification: Independently validate, minimize over-crediting, and ensure durability

Emphasized outcome: Evidence-backed claims. Crossvalidate AI estimates with stratified field plots, eddycovarianceorotherindependentfluxproxieswherefeasible, and consistency checks against regional inversions and vegetation models, reporting 95% uncertainty intervals (Baldocchi,2014;Friedlingsteinetal.,2023).

Integrity under climate variability: Apply conservative creditinganddynamicriskbuffersreflectingsinkvolatility observedin2023–24(landsinkweakening,fireemissions), ensuring credits remain high-integrity under El Niño, drought,andwildfireextremes(Bastosetal.,2024;Yinetal., 2024).

Compliance and audits: Maintain traceable data lineage, modelversioning,andreproducibleworkflows;enablethirdparty audits and periodic re-measurement to confirm persistenceofcarbongainsandaccuracyofspecies/biomass assignments(GlobalCCSInstitute,2023;IPCC,2022).

4. Framework and methodology

Figure 3: FrameworkandMethodology Source: Author

5 Financing Carbon Sequestration With AI-Verified MRV (Monitoring-Reporting-Verification: Viable Models for Industry, Cities, and Cross‑Border Markets

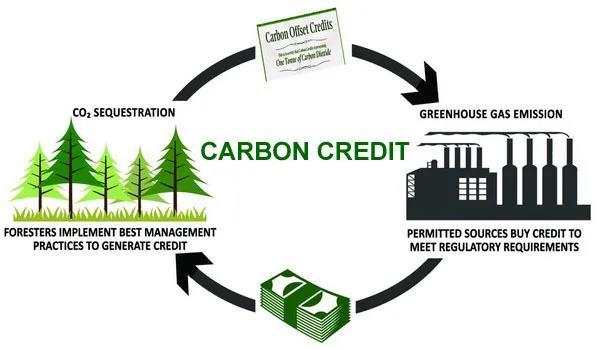

Figure 4: Carboncredits Available at: WhatAreCarbon CreditsandHowtoInvestinThemtoMaximizeYour EarningPotential

AI-verified carbon sequestration makes climate action financially viable for industries inside a city and across borders by turning local removals (from trees, soils, wetlands, biochar, or engineered storage) into trusted “carbon credits” that buyers can use under clear internationalrules,especiallytheParisAgreement’sArticle 6;withrobustmonitoring,reporting,andverification(MRV), cities and firms can aggregate many small projects,

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

document real tons removed, prevent double counting throughstandardizedregistryprocesses,andconvertthose tons into internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs)viabilateralArticle6.2dealsorcreditsunderthe Article6.4mechanism,whichopensaccesstocross-border demand and results-based payments when country processesandinstitutionalarrangementsareproperlyset up. For industries operating within the city, this creates multiple revenue and risk-management options: they can co-fundurbannature-basedsolutionsandreceiveastream ofverifiedremovalunitstobalanceresidualemissionswhile theydecarbonizeoperations;theycansignforwardofftake contractstolockinpriceandvolumeofremovals,improving planning and investor confidence; and they can use these creditswhenrecognizedunderArticle6oralignedvoluntary standards to meet internal targets, prepare for future compliance,andrespondtoinvestorandcustomerscrutiny that increasingly hinges on transparent MRV and credible accounting.Forcitiesandutilities,thesameMRVdatacan anchorsustainability-linkedloansormunicipalgreenbonds withclearKPIs(forexample,verifiedtonsofCO2removed peryear),whichlendersrewardwithbetterpricingbecause the risk of “greenwashing” is reduced by auditable measurements; standardized data and governance also improve“visibility”innationalgreenhouse-gasinventories so that local removals can be authorized for Article 6 transfers(withcorrespondingadjustments)andqualifyfor internationalresults-basedclimatefinance,furtherlowering thecostofcapital.AIisthepracticalenginethatmakesthis financeworkatscale:itautomatestreedetection,biomass estimation,growthupdates,andhealthalarmsfromsatellite and drone imagery, generates uncertainty bounds, and producesconsistenttime-seriesthatauditorscantest;these automated, reproducible measurements cut verification costs,shortentransactioncycles,andenablecityprograms to pool many small sites into investable portfolios, which greatlyimprovesliquidityandpricinginbothvoluntaryand Article 6-linked markets. At the market-design level, separating“emission reductions”from“carbonremovals,” and enforcing robust MRV, improves price discovery and system stability; emerging literature and policy guidance emphasizethatclearbaselines,conservativebuffersagainst reversals, and transparent registries reduce counterparty riskandincreasewelfareincarbonmarketsconditionsthat AI-verified city removals can meet more reliably than manual systems, especially when combined with tamper-evident ledgers and standardized reporting templates. For cross-border participation, the playbook is straightforward:

(1) align city MRV with national Article 6 authorization pathways, including corresponding adjustments to avoid doublecounting;

(2) choose the track bespoke Article 6.2 cooperation for tailored bilateral deals or Article 6.4 for standardized issuanceandembedsocialandenvironmentalsafeguards;

(3) structure finance to match risk and durability by blending upfront grants with results-based payments and long-termcommercialofftakes,andbyaddinginsuranceor bufferreservestoprotectbuyersfromreversals;and

(4) maintain public dashboards so local stakeholders and internationalbuyersseethesameauditednumbers,which sustainstrustandsustaineddemand.

Inpractice,industries benefitinthreetangible ways:they hedge policy and price risk by locking in a pipeline of verified removals tied to their facilities and communities; they unlock cheaper capital because lenders and equity investors now prefer projects with measurable, audited climate KPIs; and they gain access to Article 6 and high-integrity voluntary markets where credits command better prices due to strong MRV and clear legal transfer under international rules. Put simply, AI turns neighborhood-scale sequestration into a bankable, exportable climate asset: it qualifies for Article 6 trades, attracts results-based payments, lowers MRV costs, and supports sustainability-linked finance, while helping industries inside and beyond the city procure credible removalstomeettighteningclimate

Several cities are already documenting urban carbon sequestration,offeringconcreteexamplesofhowmunicipal programscanmeasure,map,andmanagecarbonsinksatcity scale,andthesepointtoabroadermarketonceAI-enabled MRV standardizes and lowers costs. Helsinki has piloted “urban carbon sink parks”) as public demonstration sites where city officials, scientists, companies, and residents co‑design spaces explicitly to sequester and verify carbon, emphasizingvisible,scientificallysound,andcost‑effective verificationas part of city practice. InChina, multiple cityscalestudiesshowoperationalaccountingofsequestration withinurbanplanning:Suzhouquantifiedcitywideemissions versus sinks using multisource data, finding 240.3Mt total emissionsin2020withasmallbutmappedurbansinkand thenzoningdistrictsby“carbonbalance”toguidepolicyand investment; Yancheng evaluated how optimizing an urban ecologicalnetworkboostscarbonsequestrationcapacityand used network analysis to target corridors and “stepping stones”formeasurablegains;Dongguanintegratedmodeling frameworks(LEAP,Markov-PLUS,LANDIS)tospatializeboth urban emissions andsequestration, identify weak areasof “urban carbon metabolism,”and designatecontrol regions linked to green corridors to improve the city’s net carbon balance. Additional urban cases quantify sequestration in public green spaces (e.g., Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, where researchersmeasuredtree-basedcarbonuptakeacross12 parks,pairingitwithwoodfuelproductivitytoinformcity policy),andassesssoilorganiccarbonindensemetropolitan greenspace(e.g.,Guangzhou),highlightinghowmanagement

Research

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

practicescanraiseorerodetheurbansoilcarbonpool.These efforts illustrate that cities can already document sequestration today with remote sensing, inventories, and planning models and AI will accelerate this trend by automatingcrowndetection,biomassestimation,uncertainty quantification,andchangetracking,enablingstandardized, auditable MRV that jurisdictions can plug into finance and markets.OnceAI-enabledMRVisroutine,cityprogramscan aggregatemanysmallsitesintoverifiedremovalportfolios, making credits suitable for voluntary buyers and, where authorized, for Article 6 transfers, effectively creating a scalable international market for high‑integrity, urban removals linked to transparent dashboards and national inventory “visibility.” In short, the emerging city examples Helsinki’s sink park verification, Suzhou’s carbon-balance zoning, Yancheng’s network optimization, Dongguan’s metabolism mapping, Bulawayo’s Park sequestration accounting,andGuangzhou’surbansoilcarbonassessments point to a near-term pathway where AI turns local green assetsintomeasurable,financeableclimateperformancethat canbecompared,traded,andgovernedacrossborders.

In a rapidly urbanizing, warming world, trees and other greenblueassetsarecriticalclimateinfrastructureasthey cool cities, improve air quality and public health, support biodiversity,andthroughcarbonsequestrationinbiomass andsoilsremoveCO2tostabilizecarbonbudgetsandbuild resilience.Plantingaloneisnotimpactonlyverifiedsurvival, growth, and durable carbon gains matter. An AI-enabled framework closes this gap by turning ambiguous “green cover”intomeasurable,auditableperformancedelineating individual crowns, classifying species, estimating biomass andannualincrementswithuncertainty,andtrackinghealth, mortality, and disturbances then rolling results into dashboards that guide urban planning, targeted maintenance,andheat-andflood-mitigation.

This same MRV backbone unlocks finance and policy efficiency through consistently-measured, transparently reported,independentlyverifiedremovalsthatcanbecome bankable units for results-based payments, sustainabilitylinked bonds/loans, and high-integrity carbon credits. Alignment with national inventories and Paris Agreement Article 6 (6.2, 6.4) enables corresponding adjustments, avoids double counting, and opens cross-border demand, making local nature-based sequestration investable. Clear rules on baselines, leakage, permanence buffers, and periodic re-measurement automated by AI with auditable data lineage lower verification costs, strengthen market integrity,andsupportpremiumpricing.

Institutionally, standardized data governance, open MRV protocols, and municipal training in remote sensing, ML annotation, and urban forestry create a capacity-building flywheel better monitoring drives smarter maintenance; survival improves; finance follows; and programs scale. Internationally,consistentMRVintegratescityactionsinto nationalstocktakesandArticle6transactions;domestically, it links budgets to verified outcomes, targets hot spots of heat,flood,andairpollution,andembedsresilienceandcobenefitsintozoningandinfrastructure.

This integrated approach directly advances sustainability goals: SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities) via resilient, green infrastructure; SDG 13 (Climate Action) through verified removals and adaptation; SDG 15 (Life on Land) by enhancingurbanbiodiversityandsoils;SDG3(GoodHealth) through cooler, cleaner air; and SDG 17 (Partnerships) by enablingArticle6cooperationandfinance.Lookingahead, three pillars must work together: science-based sequestration(trees,soils,wetlands,engineeredstorage),AIenabled verification (measurement and risk management fromstreettonationalscales),andfinanceablegovernance (nationalinventories,Article6,integrity-focusedmarkets). Together they transform planting from a pledge into performance: verified tree monitoring safeguards permanence;cityhealthimproves;carbonbalancesbecome manageable;communitiesbuildskillsandstewardship;and millionsofurbangreenpixelsconvertintodurableclimate assets accelerating net-zero pathways, de-risking investment,anddeliveringequitable,resilientcitiescapable ofwithstandingfutureclimatestresses

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Palthya Srinivas Naik, Assistant Professor (Urban planning Department)attheSchoolofPlanningandArchitecture,New Delhi,forhisguidanceandsupportthroughoutthisresearch

[1] Friedlingstein, P. et al. (2025) Global Carbon Budget 2024.EarthSystemScienceData,17,965–1048.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

[2] LeQuéré, C. etal.(2018)Global Carbon Budget2018. EarthSystemScienceData,10,2141–2194.

[3] Yin,Y.etal.(2024)Thedeclineintropicallandcarbon sinkdrovehighatmosphericCO2growthratein2023. CommunicationsEarth&Environment,5,406.

[4] Bastos, A. et al. (2024) Low latency carbon budget analysisrevealsalargedeclineofthelandcarbonsinkin 2023.arXiv:2407.12447.

[5] Smith, C.J. et al. (2025) Indicators of Global Climate Change 2024. Earth System Science Data, 17, 2641–2699.

[6] Gruber, N. et al. (2019) The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007. Science, 363(6432),1193–1199.

[7] Hauck, J. et al. (2023) The ocean carbon sink: Recent trendsandvariability.AnnualReviewofMarineScience, 15,91–118.

[8] Weinstein, B.G. et al. (2020) DeepForest: A Python packageforRGBdeeplearningtreecrowndelineation. MethodsinEcologyandEvolution,11(12),1743–1751.

[9] Chave, J. et al. (2014) Improved allometric models to estimate the aboveground biomass of tropical trees. GlobalChangeBiology,20(10),3177–3190.

[10] Foster,A.C.etal.(2022)Uncertaintyinremotesensingbased forest carbon estimates: A review. Remote SensingofEnvironment,271,112895.

[11] Thompson, D.R. et al. (2023) Space-based imaging spectroscopy of methane and CO2 point-source emissions.ScienceAdvances,9(36),eadg4673.

[12] Wulder,M.A.etal.(2019)CurrentstatusoftheLandsat program and prospects for Landsat Next. Remote SensingofEnvironment,225,127–147.

[13] Zhu, Z. et al. (2019) Benefits of the free and open Landsat data policy. Remote Sensing of Environment, 224,382–385.

[14] Rödenbeck,C.etal.(2023)Theatmosphericinversion challenge:Lessonsforregionalcarbonfluxestimation. AtmosphericChemistryandPhysics,23,1–29.

[15] Song,Y.etal.(2024)XCO2datafull-coveragemapping using random forest models. Remote Sensing, 16(4), 621.

[16] Wegner,J.D.etal.(2016)Catalogingpublicobjectsusing aerialandstreet-levelimages.In:CVPR,601–610.

[17] IPCC(2022)ClimateChange2022:MitigationofClimate Change. WG III contribution to AR6. Cambridge UniversityPress.

[18] Seto, K.C. et al. (2014) Human settlements, infrastructureandspatialplanning.In:IPCCAR5WGIII, Ch.12.CambridgeUniversityPress.

[19] Norton, B.A. et al. (2015) Planning for cooler cities: Prioritisinggreeninfrastructure.LandscapeandUrban Planning,134,127–138.

[20] Nowak,D.J.etal.(2013)Treeandforesteffectsonair quality and human health in the US. Environmental Pollution,193,119–129.

[21] Zhao,L.etal.(2014)Interactionsbetweenurbanheat islands and heat waves. Environmental Research Letters,9(11),114002.

[22] MEA (2005) Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis.IslandPress.

[23] UNDESA(2019)WorldUrbanizationProspects2018: Highlights.UnitedNations.

[24] Near-real-timeemissionsanddataassimilation

[25] Liu,Z.etal.(2023)Near-real-timemonitoringofglobal CO2 emissions reveals 2022 levels. One Earth, 6(10), 1145–1156.

[26] Tong,D.etal.(2023)Near-real-timeemissionestimates andapplicationsforpolicy.Joule,7(7),1462–1483.

[27] Jiang, X. et al. (2021) Global Gridded Daily CO2 Emissions(GRACED).arXiv:2105.10842.

[28] Friedlingstein, P. et al. (2017) Global Carbon Budget 2017.EarthSystemScienceDataDiscussions,10,405–448.

[29] Policyframeworks:LULUCF,REDD+,Article6,integrity

[30] UNFCCC (1997) Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations FrameworkConventiononClimateChange.

[31] UNFCCC (2001–2002) Marrakesh Accords: LULUCF modalitiesunderArticles3.3/3.4.

[32] UNFCCC(2010)CancunAgreements:REDD+safeguards, referencelevels,MRV.

[33] UNFCCC (2013) Warsaw Framework for REDD+: CompleteREDD+rulebookandRBP.

[34] UNFCCC(2015)ParisAgreement(Article5andArticle 6).

,

| Impact Factor value: 8.315 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page180

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 08 | Aug 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

[35] UNFCCC(2018)KatowiceRulebook:Paristransparency frameworkforLULUCF.

[36] WorldBank(2021)CountryProcessesandInstitutional ArrangementsforArticle6 Transactions.Washington, DC.

[37] Lockley, A. et al. (2024) The Carbon Removal Budget: Theoryandpractice.ClimatePolicy,24(5),1–14.

[38] Finance,credits,MRVintegrity,andmarketdesign

[39] GlobalCCSInstitute(2023)GlobalStatusofCCS2023. GlobalCCSInstitute.

[40] Zhang,H.etal.(2024)AnnualprogressinglobalCCUSin 2023.EnergyScience&Engineering,12(6),2290–2315.

[41] Chan, S. et al. (2022) Article 6 readiness: Institutions, governanceandaccounting.ClimateandDevelopment, 14(8),757–770.

[42] Fuss,S.etal.(2018)Negativeemissions Part2:Costs, potentials and side effects. Environmental Research Letters,13,063002.

[43] Smith,P.etal.(2016)Biophysicalandeconomiclimitsto negativeCO2emissions.NatureClimateChange,6,42–50.

[44] Minx, J.C. et al. (2018) Negative emissions Part 1: Research landscape and synthesis. Environmental ResearchLetters,13,063001.

[45] Seddon, N. et al. (2020) Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change. PhilosophicalTransactionsB,375,20190120.

[46] Grassi, G. et al. (2022) Reconciling global-model and country-reported land-use CO2 emissions. Nature ClimateChange,12,335–342.

[47] Foundational/statistical anchors and health of the system

[48] NOAA GML (2024) Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide: Global monthly mean CO2. NOAA Global MonitoringLaboratory.

[49] Baldocchi,D.(2014)Measuringfluxesoftracegasesand energy between ecosystems and the atmosphere. EcologicalApplications,24(6),1209–1229.

[50] Jenkins, J.C. et al. (2003) National-scale biomass estimatorsforUStreespecies.ForestScience,49(1),12–35.

[51] Grassi, G. et al. (2023) Harmonising land-use flux estimates of global models and national inventories

(2000–2020). Earth System Science Data, 15, 1093–1117.

[52] Saunois, M. et al. (2020) The Global Methane Budget 2000–2017.EarthSystemScienceData,12,1561–1623.

KorriAnirudhYadavholdsaBachelor's degreeinArchitecturefromDayananda Sagar Academy of Technology and Management,Bengaluru,andiscurrently pursuingMaster’sinUrbanPlanningat theSchoolofPlanningandArchitecture, New Delhi. His interests lie in the integration of technology with urban systems, focusing on AI-enabled solutions for future-ready, sustainable, andintelligenturbandevelopment.