MADE HISTORY PUTTING MEXICO BACK ON THE TENNIS MAP

MADE HISTORY PUTTING MEXICO BACK ON THE TENNIS MAP

THE 2026 FIFA WORLD CUP, JOINTLY HOSTED BY MEXICO, THE U.S., AND CANADA, FACES UNPRECEDENTED SECURITY CHALLENGES THAT EXTEND BEYOND STADIUM SAFETY. FROM TERRORISM AND ORGANIZED CRIME TO CYBERATTACKS AND EXTREMISM, THE TOURNAMENT REQUIRES INTEGRATED, MULTILATERAL STRATEGIES. THE REAL TEST WILL BE WHETHER THE EVENT BECOMES A POLITICAL FLASHPOINT OR A CATALYST FOR ENDURING REGIONAL COOPERATION.

The organization of the 2026 FIFA World Cup, hosted by Mexico, the United States, and Canada, presents an unprecedented security challenge.

It is the first World Cup to be held in three countries, requiring coordination of protocols, infrastructure, and messaging in a setting marked by transnational violence, irregular migration, and cyber threats, among other issues. FIFA anticipates 6.5 million spectators will

attend the event, scheduled from June 11 to July 19, 2026. Planning and managing sports or large-scale events demand comprehensive strategies, with cooperation playing a vital role.

The task is not just to secure stadiums or airports, but also to manage transnational risks such as terrorism, organized crime, cyberattacks, and social violence.

The OAS, through its Inter-American Committee against Terrorism (CICTE), emphasizes that major sporting events require integrated and multilateral strategies to ensure success.

A World Cup involves responsibilities that go well beyond the sports themselves. Besides respecting the daily lives of host communities, it is crucial to ensure the safety of fans, players, technical teams, the media, and volunteers. Mexico, the United States, and Canada face a significant challenge that lasts beyond the month of the tournament. It includes the entire preparation phase—building infrastructure, establishing emergency protocols, and coordinating institu-

A WORLD CUP INVOLVES RESPONSABILITIES THAT GO WELL BEYOND THE SPORTS THEMSELVES.

tional efforts—as well as the postevent period, which must create lasting legacies in security, public trust, and organizational capacity. The framework proposed by the OAS highlights a comprehensive security approach based on the SIPOC model, which divides responsibilities into six pillars: Suppliers, Inputs, Process, Outputs, and Customers. Applied to the World Cup, this means Mexico, the U.S., and Canada must work together beyond symbolism, establishing clear roles in border security, protecting tourist flows, and intelligence sharing. Given today’s security priorities and tensions in U.S. relations with Canada and Mexico, the question remains whether this coordination will be genuine or exploited for political reasons related to migration, trade, or organized crime.

Security in crowded spaces—especially stadiums, airports, hotels, and busy urban areas—poses another challenge. For Mexico, this is particularly urgent in cities like Mexico City, Monterrey, and Guadalajara, where high urban

violence meets the need to convey hospitality. Risks include theft, extortion, and cyberattacks on ticketing systems. The key is balancing international safety standards with making visitors feel safe and welcomed.

Another key element is preventing violent extremism. The OAS program highlights seven priority areas: governance, conflict prevention, community participation, youth empowerment, gender equality, education, and strategic communication. These factors are especially relevant in the Mexico–U.S. context, where threats manifest differently: white supremacism and domestic terrorism in the U.S., versus criminal violence and armed groups linked to drug trafficking in Mexico. The World Cup could serve as a binational testing ground for resilience policies that tackle these root causes.

The role of youth and women is also crucial in the international security strategy for major events.

The OAS emphasizes how sports can serve as a tool to challenge stereotypes, encourage non-violent

as a shared value. Mexico and the U.S. could adopt a joint approach that not only deters threats but also encourages binational cooperation to build mutual trust. In a time of political tensions over migration and trade, this form of public diplomacy can act as a positive counterbalance.

masculinity, and promote youth leadership. For Mexico, this involves developing inclusive programs that use the World Cup as a platform for social prevention, moving beyond police containment. Engaging at-risk youth or marginalized communities in sports projects can decrease their vulnerability to criminal networks.

Another essential element will be public–private partnerships.

The OAS highlights the importance of involving private actors, such as airlines, hotels, sports federations, and tech firms, as key stakeholders in security. In Mexico, this sparks debates about trust in institutions: can a collaboration framework ensure transparency and prevent corruption risks? Ticketing companies, telecom providers, and private security firms will play a strategic role in safeguarding critical infrastructure.

Public narratives will also be important. The #MoreThanAGame campaign, promoted by the OAS during the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, showed how strategic communication can highlight security

The legacy of the World Cup should extend beyond the final whistle. The OAS stresses that major tournaments must create sustainable legacies, including upgraded infrastructure, established protocols, and dedicated agencies. For Mexico, this involves bolstering the National Guard, tourist police, and cybersecurity along with financial intelligence. In the U.S., it might enhance regional security cooperation. However, these efforts will likely spark debate: are they essential improvements in capability, or just a cover for increased militarization and border enforcement?

The 2026 World Cup poses a dual challenge: preventing the event from becoming a target while also using it as a catalyst for regional cooperation. The OAS recommendations, combined with institutional experience in defense and intelligence, offer a clear framework for managing security at major events. The key will be whether Mexico, the U.S., and Canada can turn this moment into a positive legacy—or let it become a reactive exercise driven by shortterm political agendas.

* The author holds a bachelor’s degree in International Relations from the University of the Americas, Puebla, and has completed postgraduate diplomas in National Security, AI, Foreign Affairs, and Human Rights. She currently works as a legislative and regulatory affairs analyst and as an international consultant.

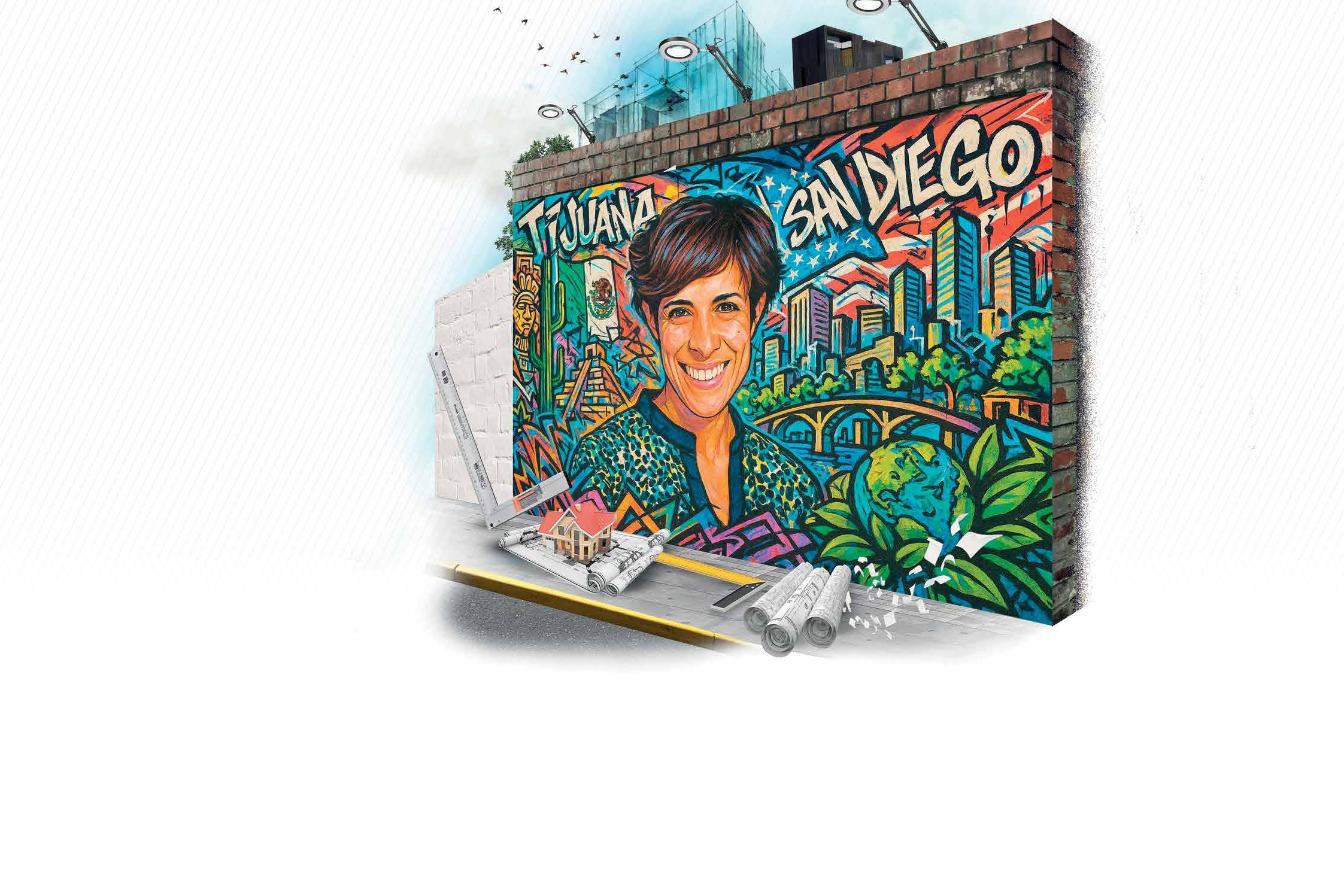

Dideal project for yourself in this border region between Tijuana and San Diego, what would it be? What would that ideal project look like for you?

A.C. think we have many, and above all, it would be a collective project. I think the ideal would be that—there are so many incredible initiatives from all the students we work with, very specific ones, but when added together they could generate an amazing city. Ideally, many of these initiatives would be taken into account like a map, a master plan for envisioning the border—the border as an infrastructure that goes far beyond just control infrastructure.

We’ve been working on speculative projects: if the project became a large greenhouse crossing the border, or structures that capture the breeze, or collective spaces integrated with urban space that would prevent erosion. The city has a serious problem: construction takes place on all the slopes and in zones very vulnerable to landslides, and yet building continues in these areas.

So how do we rethink all these spaces? As you said: the silences. That seems fundamental to me. That all voices come together and work with the government or with the decision-makers in this collective master plan.

BY: DANIEL BENET

PHOTOART: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

.B. You were born in San Diego, but grew up in the city of Tijuana, so you have this personal binational perspective, and at the same time you’re working on very interesting issues in the border region.

I’d like to start with you giving us a general overview of the space and telling us what the impacts of spatial design are on society and the environment.

A.C. As you say, that border issue is something deeply personal that we live every day crossing the border.

8.8 the environment we live in right now presents many challenges and many injustices, but at the same time there is a strong desire to connect

I grew up in Tijuana, I was born in San Diego, and I’ve been working on both sides of the border. The dynamics are very diverse; the stories from the south and the north vary greatly.

I think the environment we live in right now presents many challenges and many injustices, but at the same time there is a strong desire to connect, to understand the landscape, to understand our environment both urban and ecological, and to think about the future—how we are living this border and what the future of the border will be. Those are the questions that are really moving us right now.

D.B. It’s an issue that has become even more relevant because of the current challenges you mentioned. These border spaces between Mexico and the United States—how would you describe them? What differences do you see in the architectural or environmental spaces between the north and the south?

A.C. Let’s start with the natural landscape of the border. Here we have the Tijuana Estuary, which is located on the San Diego side. More than 70% of the water flow of this estuary comes from the north, moves south, and passes through Tijuana—which is the densest point of the entire region—before returning. So, this generates many binational challenges and makes clear the dynamics, the need for collaboration, because we’re in a shared landscape, a shared environment. Border cities, also because of this political, economic, social, and cultural division, are very diverse and are lived in very different ways. The city of Tijuana is much denser and more compact; however, it has grown in a very accelerated way. San Diego is also very large, but it expands across the territory with many more open spaces.

So, there’s a discrepancy in terms of space, of landscape, of how it’s perceived in both cities, and of course, issues like housing, infrastructure, etc. These are differences people experience on a daily basis, and the communities that live in and share those spaces are also victims of the spaces, especially in many of the canyons in Tijuana. Seventy percent of the city has been developed in an informal way, which has gradually been formalized in these canyons. In San Diego, the canyons have been preserved, so development is very different.

D.B. These natural and social dynamics—no matter how high or what color the wall is painted—it’s not a wall that can stop those dynamics, and rather what’s needed is to understand how to address them. You have a research project in the canyons, tell us about it.

A.C. We’ve been working for a couple of years in Cañada de los Sauces Norte. It’s a canyon located just south of the border that has been designated as a conservation site for more than 10 years.

However, urban development decisions have been made that put at risk the water

flow, the conservation of the canyon, and its positioning in the border space—so that’s already a huge challenge.

At the same time, this is one of the canyons that has remained without urban development inside. So, with students, we’ve tried to question design and landscape as an initiative for conservation. We ask architectural questions so that even urban projects could collaborate with the landscape from a constructive, not destructive, standpoint. We’ve carried out several projects as part of this research, and it opens up many more questions. And beyond these specific questions about the canyon, they’re really questions about our natural landscape on the border.

D.B. This project and other projects you’ve worked on from the perspective of architecture—how do they help make the border more of a meeting or connection space rather than a division? What does architecture contribute here,

and the projects you’re bringing to the border region?

A.C. think that’s a fundamental question: what does design have to do with all of this? Often, environmental solutions stay only within the environmentalist sphere, and architecture is completely separate. But here what we’re trying to manage is that correlation. For example, we have a project in Camino Verde, which is also a canyon in the southeast of the city. It was the site with the highest crime rates in 2010 and 2011. This has been an initiative to transform the area through urban space. The architectural project we did was conceived with the idea of having no walls separating the building from the landscape, and of using spatial movements with the materials—avoiding concrete surfaces that are used extensively throughout Tijuana. All the buildings, especially public ones, have these security walls, and here that perception is changed. It’s been very interesting to see that the building has held up.

Of course, it’s not only about architecture. It has a lot to do with the initiatives of the programs being managed there, such as the Casa de las Ideas with a host of social programs. All of this correlates with the design that enables it, so a public space is generated, a link with the city space is generated, and that link is what changes how we live, share, and eventually care for these spaces.

D.B. The spaces where people grow up in some way shape their worldview, and I think architectural and geographic spaces are a bit like music. It’s not just the sounds, but also the silences; and in architecture it’s not just what is there, but also what isn’t. For example, the absence of a wall, as you just mentioned, creates a completely different perception of a space depending on whether the wall is there or not. think that’s important in how communities and people imagine their spaces. If you could design an

D.B. Do you think that on both sides of the border, the authorities or governments fail to take into account the voices of the people who occupy the spaces? Are these mechanisms missing?

A.C. Definitely. And also continuity. We know very well that on both sides, the length of government terms is three years, and all the money has to be spent within that time, due to financial limits. So how can we create institutions or platforms where the citizen’s voice continues and is managed independently of political parties?

There have been platform initiatives, but in some way, they need to be strengthened.

D.B. What’s next for the architecture program and the vision that the University of San Diego has on these issues?

A.C. I think there are some incredible initiatives happening at USD on the border issue. We’ve launched the Border Ecology project, through which we have an association with Promotora de las Bellas Artes. The university serves as a platform to build these cross-border links.

Marcel Sánchez in the architecture program has been managing the transborder association of architectural education, which I think is a very important transformation that is mobilizing the entire border community—academics and students—around these issues. And think there are initiatives being generated within the university that are highly important for connection, and feel progress is being made.

D.B. Thank you for sharing this vision of your efforts and those of the University of San Diego to integrate community spaces that are currently facing strong divisive pressures. Where can we find information about the results of your research projects or about the University of San Diego’s architecture programs?

A.C. Thank you, Daniel. We have a webpage where we’re uploading project information: borderdesignlab.org.

In many American buildings, the 13th floor is skipped because of the superstition that links the number 13 with bad luck.

BY LUIS PÉREZ COURTADE

ILUSTRATION: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

Over 35 years ago, in 1985, British journalist Alan Riding, after living in Mexico for 12 years, wrote the book “Distant Neighbors: A Portrait of the Mexicans.”

It was intended for an American audience, but in Mexico, it became a classic that helped us understand our relationship with the United States—and how different we are.

Hotels and apartment buildings often omit the 12th and 13th floors to prevent unsettling guests and tenants. This practice is linked to the Last Supper, where 13 people sat at the table and Judas was the betrayer.

The term Zócalo (base) dates to 1843, when Spanish architect Lorenzo de la Hidalga built only the pedestal of a planned Independence monument that was never completed. Over time, people started referring to the entire plaza by that name. TODAY, 40 MILLION PEOPLE OF MEXICAN ORIGIN LIVE IN THE U.S. CURIOSITIES ABOUT THE UNITED STATES

The book starts with this line: “Probably nowhere else in the world are there two countries so different that live side by side.”

It quickly caused controversy and drew the interest of a broad audience.

It was both a publishing breakthrough and a political bestseller.

The book’s title—written ten years before NAFTA was signed—highlighted the cultural, social, and economic gap between the two countries, despite their geographic closeness.

In 1985, Mexico faced some of the most difficult events in its modern history: a

However, the U.S. flag features 13 red and white stripes symbolizing the original 13 colonies established along the East Coast in the 17th and 18th centuries. On the Great Seal, the eagle holds 13 arrows in its talons.

The lyrics of Mexico’s national anthem were written by Mexican poet Francisco González Bocanegra, while the music was composed by Jaime Nunó, a Spaniard.

Mexico City’s main square, commonly called the Zócalo, is officially known as the Plaza de la Constitución. It was named to honor the Spanish Constitution of Cádiz, which was enacted in 1812 when Mexico was still a colony.

MEXICO AND THE UNITED STATES SHARE A 3,152 KILOMETER BORDER

severe economic crisis; ongoing interference in its internal affairs by U.S. Ambassador John Gavin; the murder of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena, which shocked both Mexico and the United States; and a devastating earthquake that revealed the inefficiency of the political class but also showed the resilience of civil society, as millions of citizens—armed only with their will—participated in rescuing victims and supporting affected families.

In 2001, a second edition of Distant Neighbors was published, featuring an epilogue in which Alan Riding reflects on key events, such as the end of PRI’s rule and Mexico’s move toward democracy.

The trade agreement greatly impacted U.S.–Mexico relations. It has boosted their partnership to the point where over 80% of Mexico’s exports now head to its northern neighbor.

Mexico and the United States have a 3,152-kilometer border. It isn't the longest

In 1985, Alan Riding captured the complex relationship between Mexico and the United States. Decades later, with ongoing disputes over trade, migration, and security, his portrait still reflects a border that remains both closed and conflicted.

in the world—the U.S.–Canada border is longer—but the U.S.–Mexico border is one of the most significant globally because it is the busiest, handling large flows of people and trade. It holds immense cultural, social, and economic importance.

Mexico’s geographic and cultural location also makes it the gateway to Latin America.

Today, 40 million people of Mexican origin live in the U.S.

Nineteen of Mexico’s 50 land customs checkpoints are located along its northern border.

Over the last eight months, the White House has heightened tensions in the bilateral relationship through disputes over energy, trade, tariffs, and drug trafficking, among other issues.

What Alan Riding wrote in 1985 about U.S.–Mexico relations goes beyond the idea of “distant neighbors.”

More than 40 years after it was written and

published, the book 'Distant Neighbors: A Portrait of the Mexicans' remains as relevant as ever.

The actors might have changed, but the script remains the same—just updated. The differences between these distant neighbors begin with their origins: Mercenaries and prisoners took over Mexico, while English families settled in the United States.

In Mexico, a strong mix formed between the native population and European conquerors, who interacted and blended with Indigenous groups.

In contrast, in the United States, colonies were mainly settled by whole families, which limited social interaction and racial mixing.

In the U.S., Native peoples were compelled into reservations, limiting opportunities for cultural blending. Individuals of mixed ancestry were broadly classified as nonwhite, mainly Indigenous or Black.

This resulted from family-based colonization, a Calvinist religious ideology that discouraged intermixing, the severe decline of native populations due to disease and conflict, and “anti-miscegenation” laws that banned interracial marriages, reinforcing segregation.

Our political voice is strong, but tonight I want to inspire people to set politics aside and focus on humanity and humility. These are turbulent times, and yes, we are all scared—but fear is not an option. Art is our life’s narrative, but actual change always comes from people uniting and taking action.

Rosie Perez - actress

BY GONZALO LIRA GALVÁN

ILUSTRATION:

ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

The Hispanic Heritage Awards were established in 1988 by the White House, in conjunction with the official proclamation of Hispanic Heritage Month in the United States. Since then, they have become one of the greatest honors granted by Latinos and for Latinos, recognizing individuals who have left their mark on culture, the arts, science, sports, innovation, and community leadership. Organized by the Hispanic Heritage Foundation (HHF), the event takes place annually in Washington, D.C.

Such iconic venues as the Kennedy Center or the Warner Theatre have been the home for this celebration that, over nearly four decades, has honored iconic personalities such as Rita Moreno, Celia

01

A CORNERSTONE OF TRUMP'S IMMIGRATION POLICY IS THE EXPULSION OF UNDOCUMENTED IMMIGRANTS AND THE PROMISE OF MASS DEPORTATIONS.

Cruz, Gloria Estefan, Sonia Sotomayor, Los Tigres del Norte, Carolina Herrera, and many more.

“This is not just a celebration. This is a call for unity” exclaimed Antonio Tijerino, president and CEO for the Hispanic Heritage Foundation as he walked the red carpet for the 38th Hispanic Heritage Awards at downtown Washington D.C.

“We need to be united if we expect to move forward. We’ve been practicing for so many years to face this kind of challenges. So I think we will survive this difficult times”, Tijerino exclaimed.

The Hispanic Heritage Awards ceremony is broadcast nationwide through PBS, allowing millions of people across the United States and beyond to watch and celebrate the achievements of the Latino community. Yet, in an era where public media is being challenged by presidential mandates in the United States, the broadcast of this ceremony in particular seems as a resistance call more than ever.

“If you’re watching this ceremony on a screen, it surely is through PBS”, said Felix Contreras as he received the recognition for

his journalistic contributions. Contreras is the creator of NPR’s Alt. Latino podcast and one of the main creative minds behind the very popular Tiny Desk Concerts format.

Felix Contreras championed his recognition in this year’s ceremony claiming how necessary the journalistic work is in difficult times. “Journalism is so important right now. We’ve always had a job to do and it never changes. We have the same responsibility we had in the past, the present and the future”, said Contreras. “Because journalism is the best way to tell our stories and contextualize our existence in our very own ways”, he pointed.

The 38th edition of the Hispanic Heritage Awards is more than just an award show, it is a gala that combines tributes with live music, inspiring speeches, and an atmosphere that reflects Latino cultural pride. The awards cover a wide range of fields. Some categories include: Legend Award, honoring established careers that have influenced generations. Vision Award, for innovators and

THERE ARE OVER 65 MILLION HISPANICS IN THE U.S., ABOUT 19% OF THE TOTAL POPULATION, INCLUDING PEOPLE OF ALL LATINO ORIGINS. WITHIN DAYS OF TAKING OFFICE, TRUMP'S DEFENSE DEPARTMENT USED MILITARY PLANES TO DEPORT OVER 5,000 DETAINEES HELD BY BORDER PATROL.

creators opening new paths. Recognitions in science, education, sports, community leadership, media, art, and business.

This diversity highlights the vast contributions of Hispanics to U.S. society and the world in a historical moment where Hispanic and Latino identities are trying to be diminished on its relevance and influence.

For the 2025 edition, notable honorees included Mexican singer Gloria Trevi, recognized with the Legend Award for her more than 40-year musical career. Also Puertorican reggaeton singer/songwriter Rauw Alejandro, who received the Vision Award for his innovation in urban music and international reach. Comedian Cheech Marin and actress Rosie Perez accompanied them on the stage of the Warner Theatre as they also received their very own recognitions the same night.

“I’m the son of a cultural mixture and I’m proud of carrying this in my blood”, said Rauw Alejandro as he received the main award of the night from reggaetonlegend Ivy Queen. “My blood and lineage has guided my art all the way. Because our great-great grandparents came and help to build this beautiful nation we’re sharing. We shall never forget we are the result of that effort”, said the puertorican urban singer.

The Hispanic Heritage Foundation not only organizes this annual event but also leads impactful programs such as the Youth Awards, which support

pays tribute to those already shining but also inspire new generations to continue building a Latino legacy with global impact.

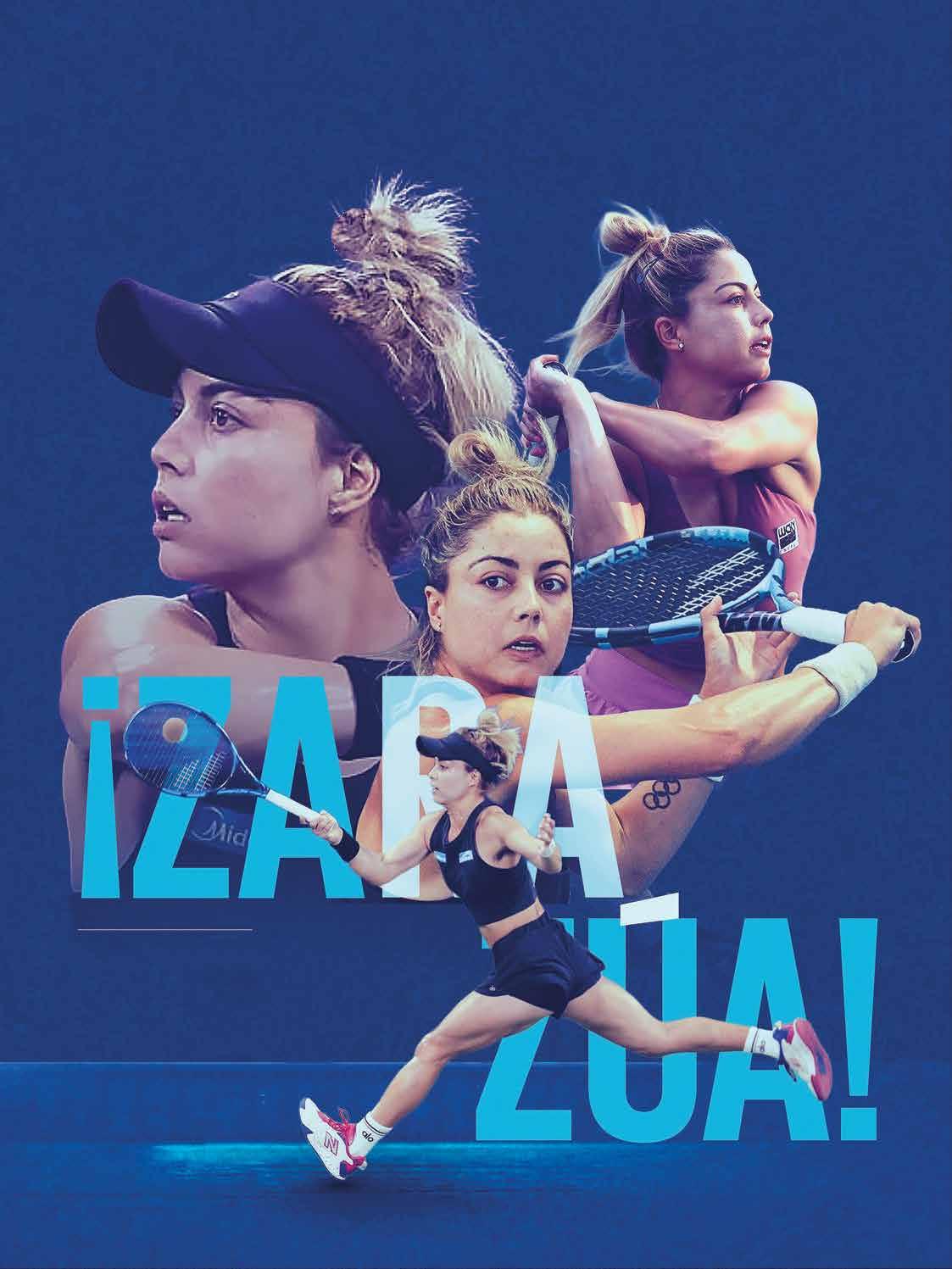

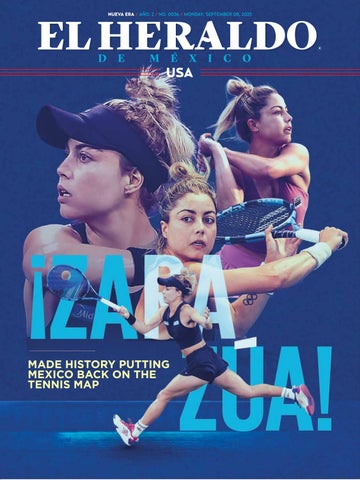

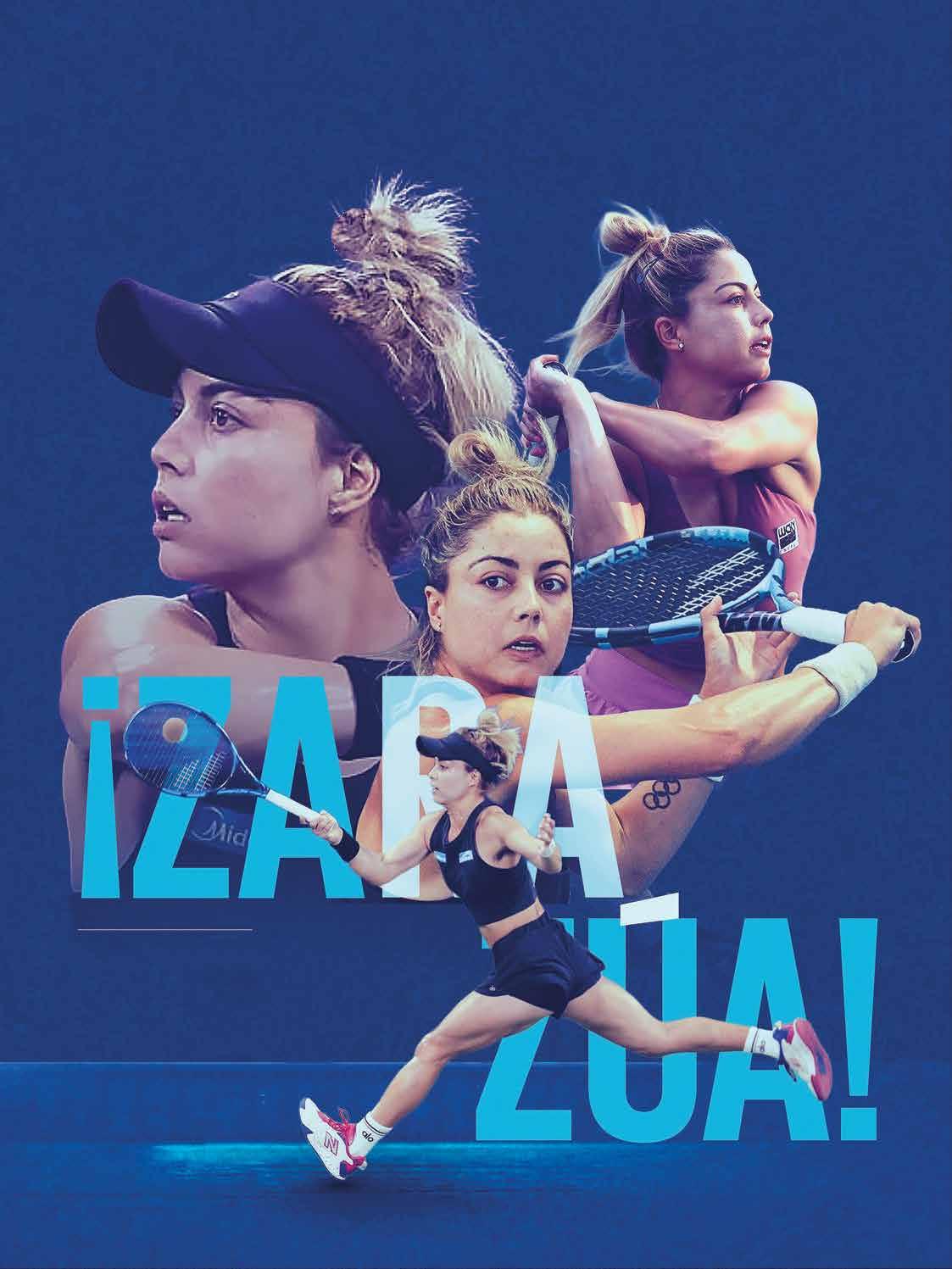

Renata Zarazúa made history at the 2025 US Open by defeating Madison Keys, the world No. 6 and reigning Australian Open champion, in a stunning upset at Arthur Ashe Stadium. Her victory not only marks the first time a Mexican has beaten a top 10 player in a Grand Slam, but also revives Mexico’s longdormant tennis legacy. More than a match, it was a triumph of resilience, sacrifice, and national pride.

BY ANTONIO DE VALDÉS

ello, friends!

What we witnessed at Arthur Ashe Stadium will stay forever in the history of Mexican sports. Beating Madison Keys, a local player, world No. 6, and Australian Open champion is not something you see every day. And you, Renata, achieved it with the composure of a true champion.

The numbers speak for themselves. Keys had won 11 of her last 13 matches on hard court and hadn’t lost to a player outside the top 50 in over a year. And then came you, the Mexican who never gives up, to shatter all predictions with tennis full of grit, intelligence, and heart.

This victory is no coincidence. It’s the result of a career that has always faced challenges.

From those junior tournaments where you had to fight against the odds to your qualification for Roland Garros in 2020, when you became the first Mexican woman in the main draw in over twenty years. Tears, injuries, sacrifices, and most importantly, the resolve to keep going when it would have been easier to quit. All of that was evident on the scoreboard, point by point, game by game, on that unforgettable night in New York. And your story touches us all. Decades ago, Mexico celebrated the achievements of Rafael Osuna, who won the US Open in 1963; Yola Ramírez, a finalist at Roland Garros; Angélica Gavaldón, who reached the quarterfinals in Australia; and Raúl Ramírez, a top 5 player in the world and Wimbledon doubles champion. But those accomplishments seemed increasingly distant. In tennis, we had grown used to watching Serena, Federer, Nadal, or Djokovic win from afar. Until today. Because in 2025, you gave Mexico back the pride of seeing one of our own defeat a top 10 player in the world, on the biggest stage in tennis. By the numbers, your victory is historic: never before had a Mexican defeated a top 10 player in a Grand Slam. And doing it at Arthur Ashe, with a capacity of more than 23,000 people, makes it even more memorable. Renata, today you are trending nationwide, and rightfully so: you achieved what once seemed impossible, and you did it with that contagious smile and inspiring grit. This victory serves as a lesson. To those of us who dream of achieving something great, you remind us that the path is not always straight; it’s filled with stumbles and doubts, but if you

CURRENTLY, THEIR SPONSORS ARE FOREIGN. THEY ARE SEEKING SUPPORT FROM MEXICO.

THE MAIN GOAL IS TO SLIDE THE STONES INTO THE “HOUSE,” AS CLOSE TO THE CENTER AS POSSIBLE.

TO SCORE POINTS, A TEAM MUST HAVE AT LEAST ONE STONE INSIDE THE HOUSE.

THERE ARE NO REFEREES — FAIR PLAY IS EXPECTED.

BY ÉRIKA MONTOYA

O’GAM

One night, far from her homeland, Adriana Camarena turned on the TV and came across a broadcast that would change her life forever.

On the screen, athletes slid granite stones across the ice with a precision that resembled a choreographed ritual, shouting at the top of their lungs. It was curling, a sport unknown in Mexico, but for her, it represented something much greater. What started as curiosity quickly turned into the discovery of a community she didn’t know she was missing.

A lawyer and writer, Camarena migrated in pursuit of a better professional and personal life. But like many migrants, she also experienced the loneliness of being far from home and in a place where the language was not her own.

Curling became an unexpected refuge, a place where discipline and teamwork gave her a sense of belonging. She decided to take lessons and quickly realized she had found a second family on the ice.

“Curling is my safe place. found a community that immediately embraced me, and they not only explained the sport to me but also pitched in to buy me my first equipment. That really surprised me,” Camarena told Heraldo USA. Her discovery coincided with a call from the Mexican Curling Federation, which was recruiting players abroad to represent the country

After the pandemic, I realized there were families who had lost everything, and that’s why we decided, to found the organization and support my community”.

in international competitions. Adriana saw the opportunity and seized it, even knowing she would compete against women half her age with twice her experience. Her motivation was clear: to prove that sport could also be a way for the Mexican diaspora to leave its mark on unexpected stages.

Over time, her personal gamble evolved into a collective effort. Other migrant women joined her — living in different cities across the U.S. and Canada — connected not by their careers but by a shared belief. Among them: designer Estefana Quintero, teacher Karla Martínez, scientist Verónica Huerta, and real estate agent Karla Knepper. What they shared was the confidence that they could create a new space for Mexico in winter sports.

“It’s a dream to represent Mexico. It’s something I can’t even explain. The world of curling is so welcoming to everyone, and that feels really good,” Karla tried to put into words.

“We’re trying to represent Mexico in the best way possible, and what better way than to wear the uniform, play a sport, and carry

A GROUP OF MEXICAN MIGRANT WOMEN HAS DISCOVERED CURLING AS AN UNEXPECTED PLATFORM TO PURSUE AN OLYMPIC DREAM. FROM COMMUNITY SUPPORT AND SACRIFICE TO RESILIENCE ON THE ICE, THEY ARE ABOUT TO MAKE HISTORY AS MEXICO’S FIRST TEAM WINTER SPORTS.

ADRIANA

our name with pride,” added Estefana, who jokes that her house floors aren’t nearly as polished as the curling ice.

The challenge for this group of women is immense. None of them receives institutional support, and Mexico has little history in these disciplines. Training remotely, organizing via video calls, and paying for travel and training camps out of their own pockets has become routine. Many times, they juggle two or three jobs to keep the dream alive. Still, in just six years, they reached the A category of the international circuit, standing among the best in the world and now with a real shot at fighting for the last two spots at the 2026 Winter Olympics.

For Adriana, this project is about migrant identity more than a sports triumph. The ice rink became a place where identities are rebuilt, and where the distance from Mexico becomes a source of strength.

Her leadership has aimed to emphasize that aspect: curling isn’t just about reaching the Olympics. It’s also about setting an ex-

Curling has become something addictive in my life. It’s my safe place, and I’m glad more women have joined,”

ample and leaving the door open for future generations.

The message is clear: collective dreams go beyond borders.

“We dream of passing the torch,” said Karla, confident that their effort won’t be an isolated story.

They hope that future generations in Mexico will see winter sports as a promising opportunity, inspiring young people who never imagined competing on ice to find motivation on their journey.

Without official support, they have had to depend on their own effort and the solidarity of those who believe in their cause.

Even so, they stay determined: each competition is a chance to demonstrate that, even thousands of miles from home, they can start a new chapter in their country’s sports history. Today, with their eyes on the final qualifying rounds, the team dares to dream of an Olympic spot.

For Mexico, it would be a historic debut in curling — a sport far from its national culture but rich in symbolism. Behind every stone launched is the will to give something back to their homeland.

Adriana Camarena’s story shows that sport can be just as powerful as the written word and that one person's gesture can create a lasting community legacy.

If Mexico ever competes in Olympic ice skating, her name will be remembered as the woman who, from abroad, planted the first seed of an impossible dream: opening the path for Mexico in curling.

BY ALAN VARGAS ILUSTRATION: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

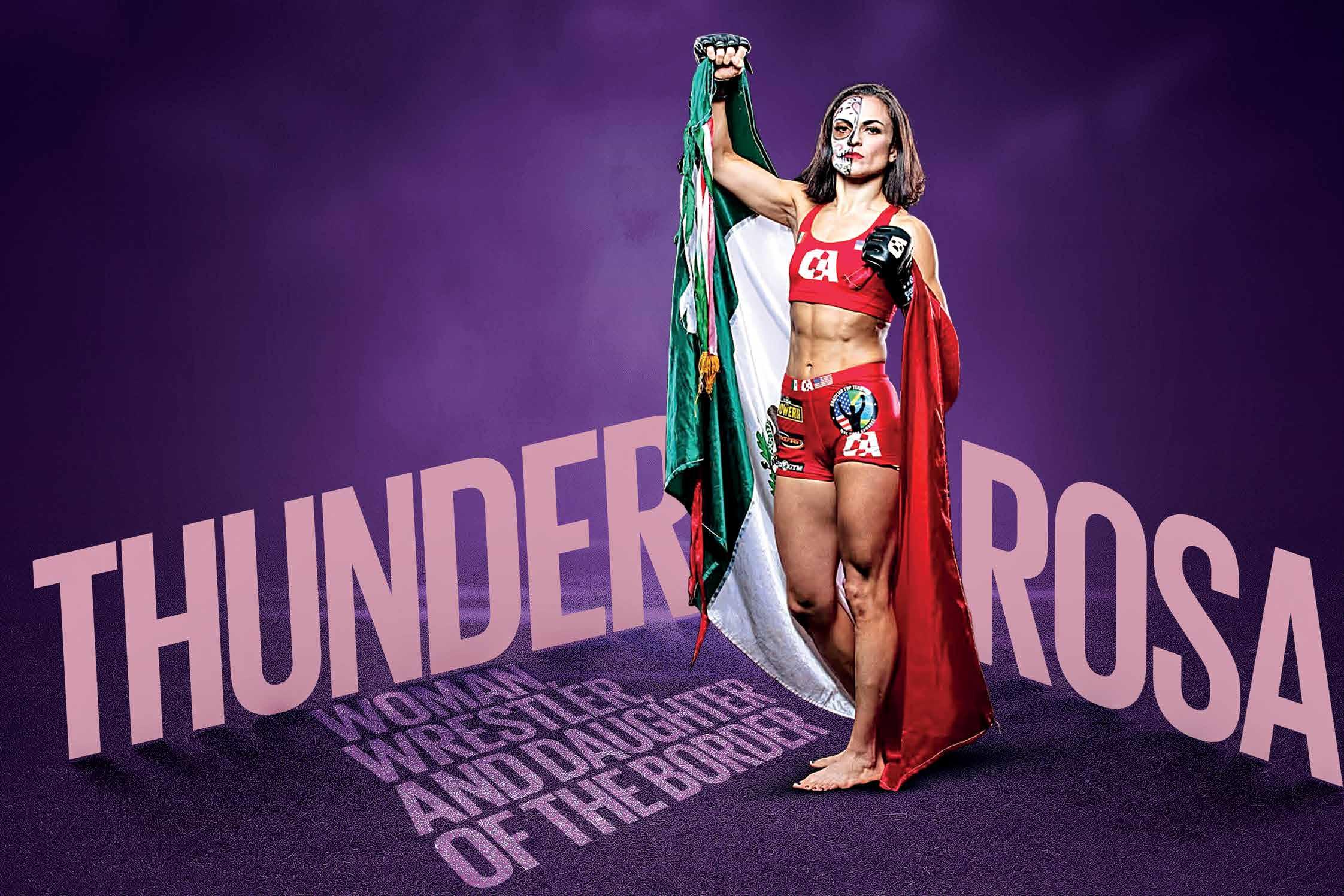

With her face painted like a Catrina in the ring, she says it’s a way to honor the women and men who fought along the border in search of a better future. Melissa Cervantes was born on July 22, 1986, in Tijuana. She studied sociology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Her story and accomplishments

This unique combination of her sociology studies, combat sports, and ongoing activism now serves as a voice for Mexicans in the United States. Her name, “Thunder Rosa,” holds significance today in the world of international wrestling. In 2020, she signed with All Elite Wrestling (AEW), the leading professional wrestling company in the U.S., where she has played a vital role. In 2019, she also signed with Combate Américas. She is the first Mexican wrestler to win both the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) and AEW Women’s World Championships—an unprecedented accom-plish-ment in the U.S. She also founded Mission Pro Wrestling (MPW) in 2019, a promotion dedicated to promoting and showcasing women’s talent in professional wrestling.

Reaching the biggest stages in wrestling and mixed martial arts has been a tough journey in a sport where men have long dominated. It has required breaking from convention while embracing the commitment and responsibility of being a World Wrestling Champion.

Before wrestling and during her early college years, Melissa worked as a social worker, supporting at-risk youth facing mental illness, homelessness, and substance abuse. This is worth mentioning because she understands that her people’s struggles are not always fought in the ring.

Thunder Rosa, born Melissa Cervantes in Tijuana, is a pioneering Mexican wrestler and activist who became the first to win both the NWA and AEW Women’s World Championships. Outside the ring, she advocates for Latina women and migrant communities, using her platform to motivate girls to chase their dreams without limits.

In 2022, she was named one of the top three female wrestlers in the world by Pro Wrestling Illustrated Women’s 150, an influential publication that also ranked her among the top five in 2021. On March 16, San Antonio, Texas, celebrates “Thunder Rosa Day,” an honor that extends beyond sports and recognizes her career and social commitment.

A wrestler who uplifts her sisters Working with AEW has enabled her to share her voice at universities and border communities, highlighting the richness of Mexican culture. She has expanded into platforms like radio, music, and hosting — serving as co-host of the wrestling podcast Busted Open on Sirius XM and recording Thunder Nights on YouTube. Her social commitment includes working with organizations like Boys & Girls Clubs in Tijuana and Nuevo León, supporting youth in vulnerable communities, and collaborating with MANA de San Diego, a nonprofit dedicated to improving the quality of life for Latina women in the U.S. Her goal