“Magic is a bridge that allows you to move from the visible world to the invisible world and learn the lessons of both worlds.”

One lives more or less removed from the madding crowd, I don't know if it's because I'm entering that phase of retirement that accompanies the cycles of change typical of my advanced age, or because of predilection, that the goat returns to the mountain; but it is a fact that my contact with people, especially those who are not my age, is decreasing every day, with the exception of my beloved wife, who, being insultingly younger than me, is an exception to all the rules. Bless her!

Secluded in my personal world, I am out of step, and I placidly ponder my sought-after asynchrony with the world, almost without realizing that the distance of that rift is growing greater and greater every day.

The radio, TV, and newspapers that I listen to, watch, and read speak to me through the news; there is almost nothing new under the sun in this predictable decline of the West; news that is almost like Groundhog Day, a repetition of itself, contributing nothing to this distance from that other reality that is unfolding far away from me. Two events, however, have changed this ever-increasing distance from the world. The first and foremost is having taken on students in recent years. My interaction with them through feedback brings me back to the world of men, to the territory of others, their concerns and perceptions.

The second event has to do with something I would never have done, which was watching a reality show called “First Dates.” Both events are related because I watched the show for the first time when a student decided to participate in it.

Given the current state of affairs... I am stunned! Surprised! Flabbergasted! I lack the words to describe my state of mind after watching the TV show. Any assumptions I had about the unstoppable decline of the West, the squalor and mental dandruff of the people, pale in comparison to the reality that is out there. Things are really screwed up; the level of stagnation in which my fellow humans find themselves is extraordinary, especially among the younger ones.

You see the older ones who come to the show, and in general there is a sensibility, a disposition, a very different foundation, even though the program tends to attract specimens who are already marked by the mere fact of wanting to sign up for it. But come on! There is a certain order, which contrasts with the mental chaos of the younger ones. The clichés they fall into show the poor upbringing they have received, the total absence of judgment, which leads them to be completely defenseless when faced with information that is intentionally served up in the context that shapes the morality of our times.

Their position on essential issues of life such as sex shows that we are a lost cause; we die as a result of our own success, wallowing in the mud of our ignorance and stupidity. You have to see how they swallow everything hook, line, and sinker, going to the mangers prepared for them, more lost than an octopus in a garage. What gems!

No, I don't want to fall into the trap of thinking that the past was better, because every generation ends up saying the same thing. There are surely wonderful people out there, but the environment in which these extraordinary fish will splash around is so polluted and perverted that they will hardly be able to survive the prevailing chaos.

Empires rot from within; before and after Rome it was like this; the invasion of the “barbarians” that mark the end of historical cycles are only the natural consequence of that putrid and decomposed state. The forest is clean, but if you throw carrion, the vultures will soon appear! Ants, vultures, etc. are only doing their job, following their nature.

The West is breathing its last breaths, trying to react, but the time for that has passed. The cycles of becoming act naturally, for like the Tao, which does nothing, but nothing remains to be done, they fulfill their designs with the imperturbable firmness of the unfailing; when destiny speaks, others are silent.

Europe is drowning in its well-meaning drivel, while its stars and stripes alter ego makes clumsy moves in defense of its way of life and flag, simply destroying them. And it was not just any banner! It was the banner of freedom, law, and justice!

It's no one's fault... for the most restless, relax! There is nothing to be done... Nothing to defend, much less to conquer; on the contrary, any movement, when you are hanging by a thread, will only accelerate the process of decline. Trump is just the trumpet of a foretold apocalypse, Putin the standard-bearer of outdated supremacism on a mixed-race planet.

This is not defeatism, it is experience! Things rise and then inevitably fall; history continues, and before everything gets better, it will have to get much worse.

The balance of the world has shifted toward a new East, and its paradigm does not yet know where it is going. The values of the halved empire, of that fallen West, will not survive as they were formulated, but what is eternal in them will sooner or later flourish in new lands and different times with a new interpretation. I will not see it, but I know it will be so because history teaches us this long-repeated process like a litany in the background that whispers its song before it arrives.

With my most lucid friends (all on the starting line of this world), I attend this “so splendid disaster” like “Zorba the Greek,” most of the time dancing and trying to laugh, because life is too short to live in lamentation and because everything passes. There is no trace left in me of the half-hero, if he ever was, nor of the high-flying Promethean dreamer who once inflamed my dreams; Now it remains to attend to the near, the invisible, and the subtle, much more than the thick worldly stroke, which I avoid, like the sands of time that slip through my fingers, discarding everything futile, banal, and useless.

The spiritual dominates my daily life, but I will still offer some reflections on this apocalypse, like Lao Tzu when he left the kingdom, because I feel like it, and to lighten my load. Let those who come after me take up the reins, as is their duty.

“Empires rot from within; before and after Rome it was like this; the invasion of the ‘barbarians’ that mark the end of historical cycles are only the natural consequence of that putrid and decomposed state. The forest is clean, but if you throw carrion, the vultures will soon appear! Ants, vultures, etc. are only doing their job, carrying out their work, following their nature.”

“Empires rot from within; before and after Rome it was like this; the invasion of the ‘barbarians’ that mark the end of historical cycles are only the natural consequence of that putrid and decomposed state. The forest is clean, but if you throw carrion, the vultures will soon appear! Ants, vultures, etc. are only doing their job, carrying out their work, following their nature.”

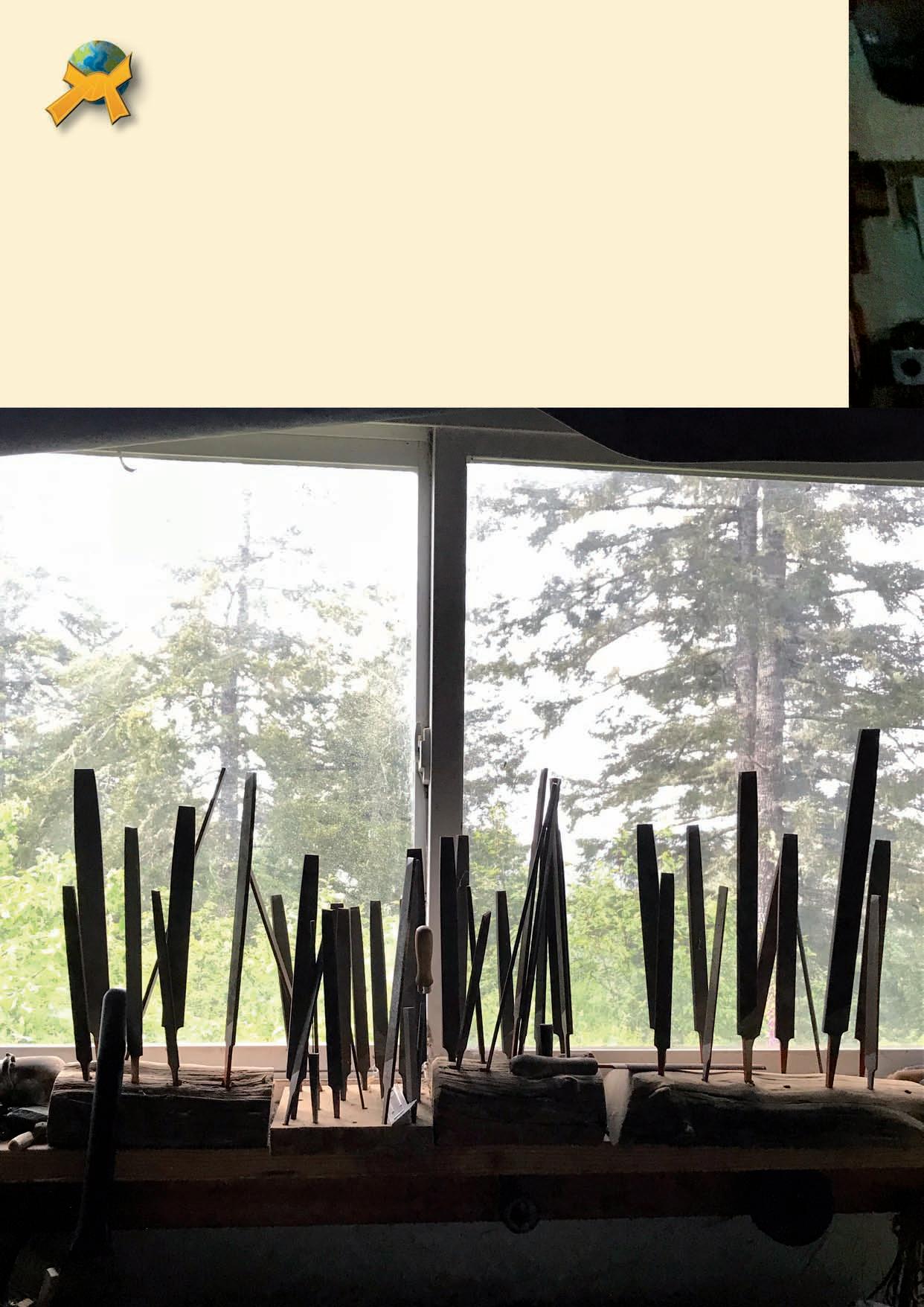

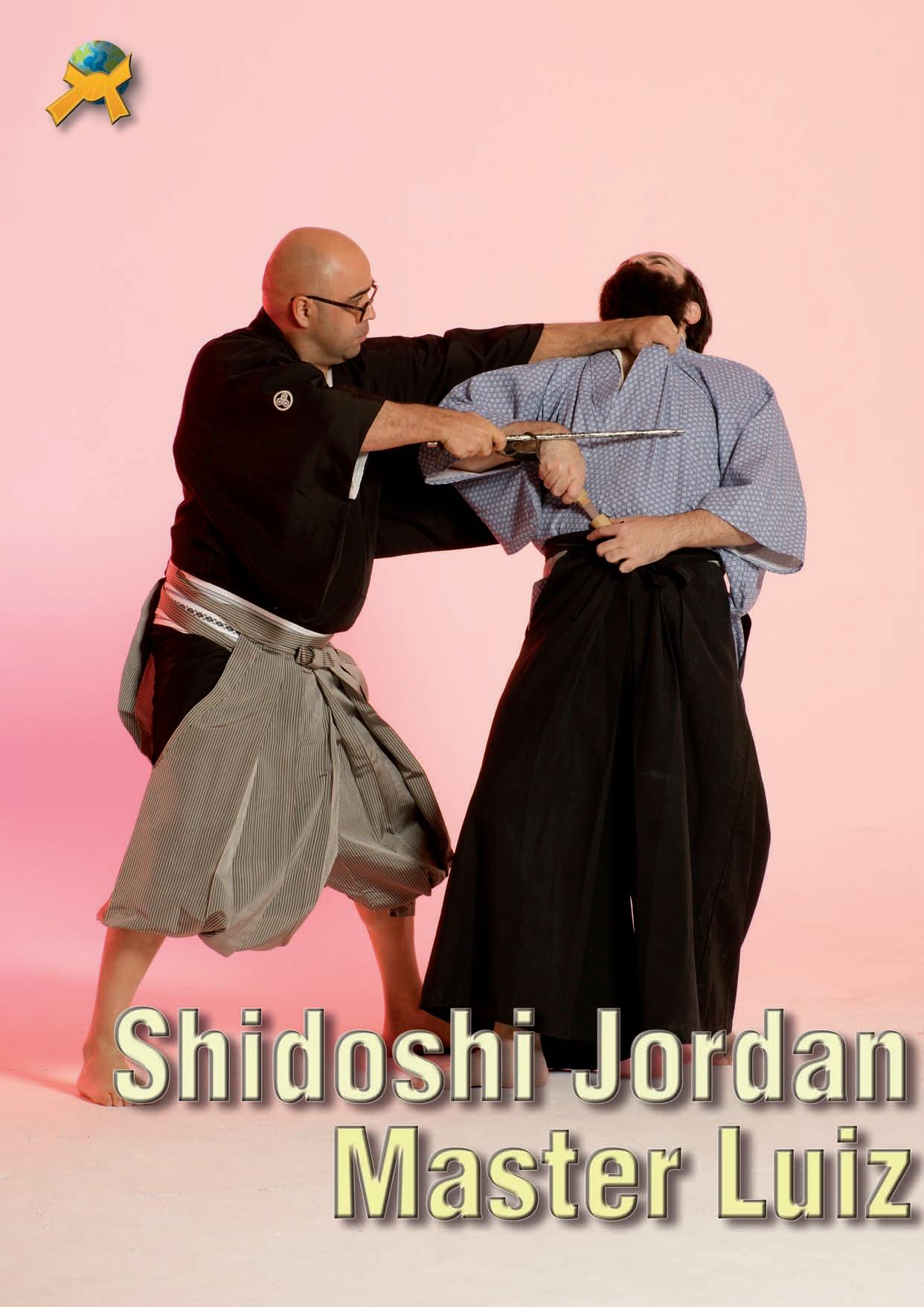

Because of its proximity and easy access, because it doesn't require special training to be lethal, and because it breaks the barrier of "strongest," the knife is the most dangerous weapon in existence.

In a thousand different forms, since man created metal, the knife has made a difference in close-quarters combat. The Yamato banned them in Okinawa; they say there was only one kept in the center of the village for sharing food, a fact that undoubtedly elevated the training of the nascent bare-hand art later known as Karate and all the Kobudo weapons, made from farmyard tools that couldn't be confiscated by the oppressors.

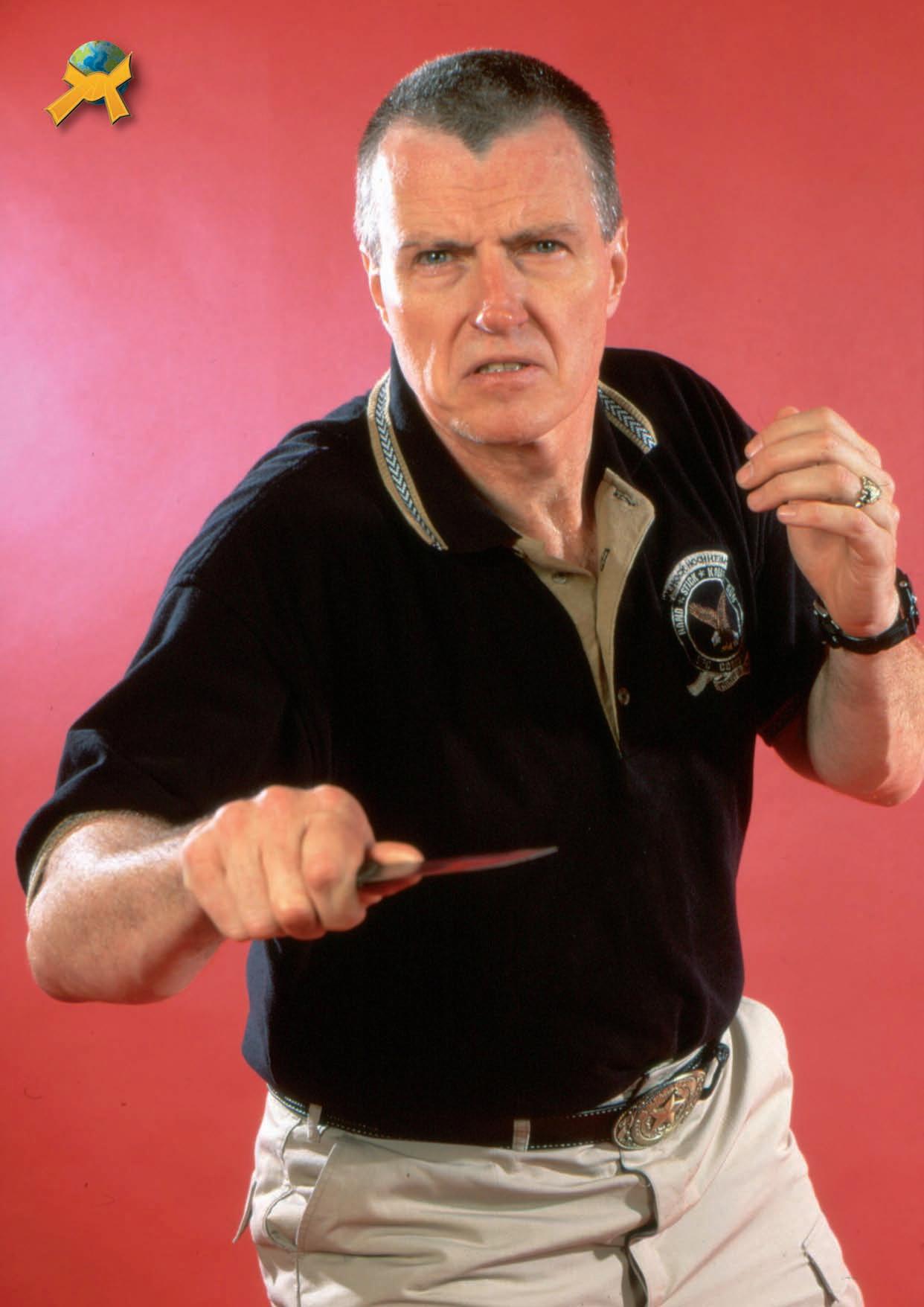

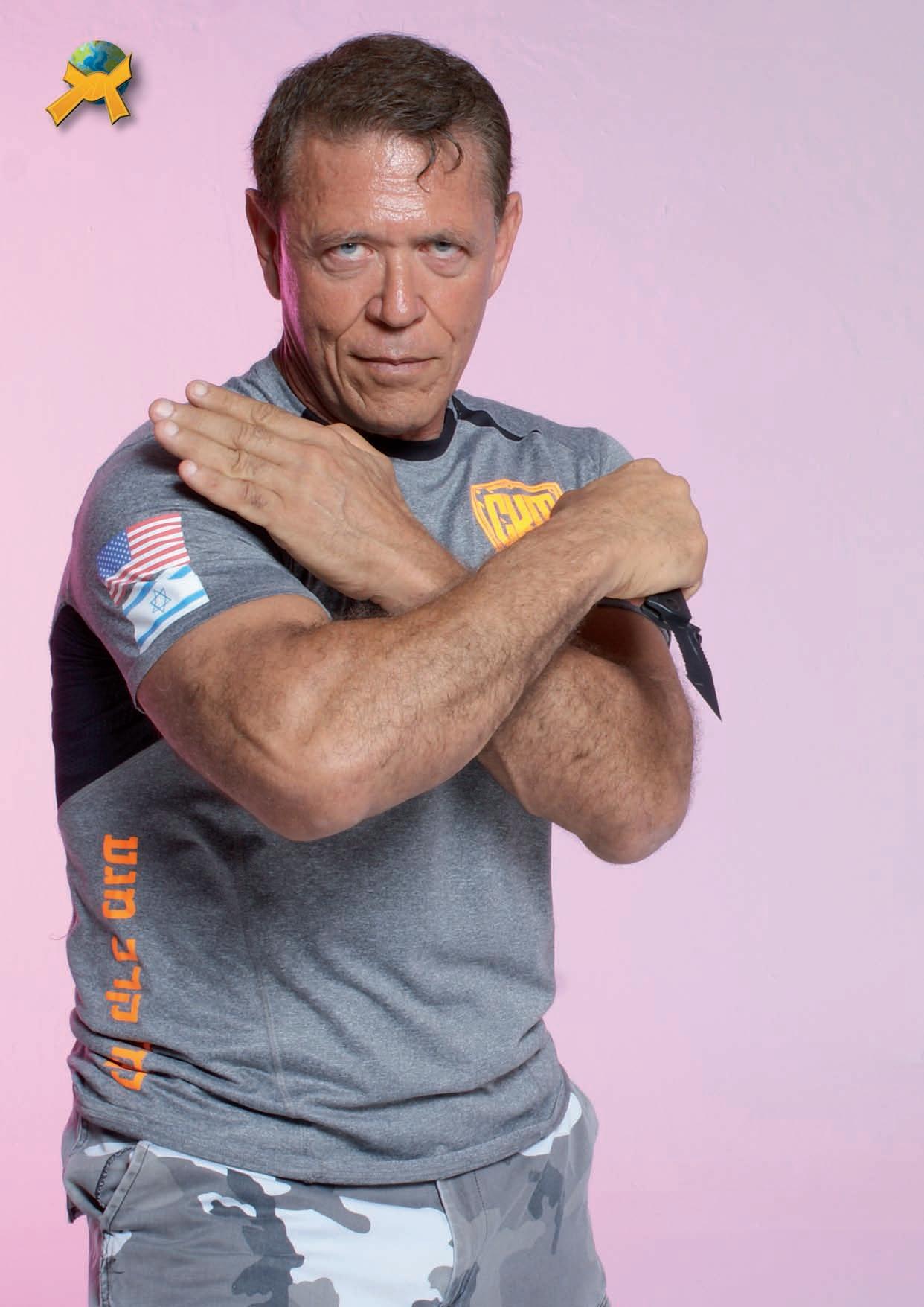

Disqualified during the 19th century with the appearance of revolvers and the widespread use of pistols, in recent decades it has regained prominence among experts, who have demonstrated its superiority even at close range. For all these reasons, our expert David Sensei Stainko reflects on this weapon, its history, and its environment in this excellent article.

The knife has been used as a weapon in martial arts since ancient times. Many martial arts instructors today still use it in their training, which might make you think that we know a lot about the knife as a weapon. But is that really true?

Dagger or Knife – a handheld tool used for cutting and a cold weapon used for slashing or stabbing.

Blade – the cutting part of the knife (or sword), which can have one or two sharp edges.

Knives are generally divided into three types: stabbers (made for thrusting), skinners (used for skinning animals), and throwing knives.

The earliest human weapons were made from wood, stone, and bone. Later, with the discovery of metalworking, humans created more practical tools and weapons from bronze and eventually iron – like swords, axes, spears, arrows with metal tips, spiked maces, and of course, different kinds of daggers and knives. In fact, the first tools – flail (maces), axes, and knives – were also some of the first weapons used in wars, leaving lasting scars on human history. Daggers and knives have played a major role in combat throughout the world, used in one-on-one fights and in large-scale battles. Just about every culture has its own distinct style of dagger or knife.

David “Sensei” Stainko David “Sensei” Stainko

As a

a

Knife fighting has existed since ancient times – going as far back as 1500 BC – in places like China, Egypt, Japan, Greece, Rome, Africa, among the Maori, the Mayans, and Native Americans. Yet today, there are only a handful of structured schools that teach knife fighting as a formal discipline. Some have specific names for their style, others don't. Some of the earliest daggers and knives came from China, Egypt, Africa, Europe, Malaysia, and India.

In ancient China, a well-known knife was the “do” – a long, single-edged blade shaped like a crescent moon. These came in two sizes: the larger one was used like a sword, the smaller like a knife. Similarly, in medieval Italy, there was the cinquedea – a dagger made in three different sizes (similar to the German dagger called a rapier came in two sizes or Italian dagger called stiletto) . A regular Chinese long sword is called a gim.

Chinese kung fu masters often use a pair of knives known as butterfly knives, especially in close combat, a tradition dating back to the Sui Dynasty (around 581 AD). The Mayans and Incas also used knives in battle. The most famous Mayan knife was their “sacrificial knife,” (volcanic glass knife – the sharpest knives, sharper than a scalpel) used in ritual killings as offerings to their gods.

Some countries are famous for their daggers and knife traditions. Malaysia, often called “the land of the dagger,” had early daggers that were flat, slightly curved, and sharpened on both sides – meant purely for stabbing. Later, single-edged knives were developed, often used first for skinning animals (hence the term “skinners”), and unfortunately, they were soon also used in combat.

Several knives have become legendary, like the khanjar, a curved double-edged knife from the Arab and Persian world. Then there’s the Turkish yatagan, a large curved blade sharpened on the inside. In Turkish tradition, receiving a knife (called kama) marked a boy’s transition to manhood. Wealthier men carried fancier, decorated versions.

Indonesia is known for its beautiful and traditional kris knives, first appearing in the 7th century. These are often wavy in shape and carried by men and women alike. In feudal Japan, the short dagger known as tanto was popular from around the 1100s. Samurai used it in close combat and often kept it hidden. Japanese women also carried tantos (or kaiken small knives) for self-defense and to protect their honor, much like women in Europe (for example, in Italy, France and England) who hid small knives in their waistbands.

In Scandinavia and parts of Russia, the Finnish knife (Scandinavian knife better known than the seax old Viking knife from the 11th century) was originally used by fishermen to clean fish and open seashells but later became a self-defense weapon. The Russian poet Sergei Yesenin even mentions it in his poem A Letter to My Mother.

In Japan, the art of fighting with a small dagger is known as tanto-jutsu, and samurai also used a long knife similar to a European bayonet, called juken. Training with such knives, known as juken-jutsu, is still practiced today, mostly by soldiers and the police. The bayonet, a long-bladed knife that attaches to a rifle, was invented in Bayonne, France in the 16th century. It could be single-edged, doubleedged, or triangular, and was used both for stabbing and slashing and had flutes on the side so that the opponent's bllod could run off the blade. The blade could be put on the rifle so that it could be also used as a spear after firing, i.e. to stab an opponent in close combat. Such "plug-in" bayonets were fixed on rifles by using a special kind of rings at the end of the 17th century. French pirates liked using it often, too.

Moroccan riflemen in the French army during both World Wars became famous for their bayonet skills – they were known as the “Swallows of Death.” As a weapon, it was placed on the left hip and almost all armies of the world used it up until the Korean War in 1965. Although the bayonet is no longer widely used in modern warfare, it’s still taught in some armies for self-defense training. Collectors around the world highly value historic bayonets.

A major breakthrough in knife fighting came with the invention of the Bowie knife. Unlike the other knives (like the Arkansas toothpick a famous knife in the early 19th century), this one has an inventor and it was named after American frontiersman James Bowie who was born in Georgia in 1799. He was very adventuristic and crossed the entire Mississippi and Alabama as a young man while hunting and exploring the terrain. Bowie started using such a knife in 1828 and some believe he got the idea from a popular pirate Jean Lafitte who was his friend and a slave trader. Bowie died in 1836 defending the Alamo alongside the legendary American fighter Davy Crockett. The name of the knife remained connected to his own name.

“Daggers and knives have played a major role in combat throughout the world, used in one-onone fights and in largescale battles. Just about every culture has its own distinct style of dagger or knife.”

As

His knife featured a long, curved blade, about 22–28 cm in length and 5–7 cm wide – good for both stabbing and slashing. U.S. frontiersmen later adopted this type of blade. Over time, the knife was modified – some versions had serrated edges and some had smooth edges. Mass production began in England in 1932. A popular variant today is the Buck knife, used by hunters. Such a hunting knife is also being used by certain militaries around the world in combat actions, i.e. in close combat. In Australia, this style of knife is practically part of the culture. Knife fights have been recorded by historians all over the world. One famous story is the 1876 duel between W. F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) and Sioux Chief Yellow Hand, where Bill won using a knife in a traditional Native American fighting style.

In more recent times, in the 1940s, a new type of knife appeared – the switchblade, with a spring-loaded blade that popped out from the handle. It was easy to conceal and became a popular self-defense weapon. Nicknamed “The grasshopper“ because of the way the blade “jumped” out, this American invention was especially popular among Italian-Americans. Still, the most iconic knife of the modern era that appeared at the end onf the 1950s is the so called "butterfly" knife. Versions of this knife existed before, especially in Europe, for example, the Spanish knife navaja and in the Philippines. The handle folds around the blade and flips open with a twist of the wrist so it makes the handle and the blade both usable. The knife is very practical for carrying and is effective in self-defense. Its real name is balisong and it originates from the Philippines where Filipino women often carried them for self-defense. In the U.S., it became very popular and known as the “nunchaku of knives” in the 1980s.

In America and Europe, the knife is known as the butterfly and its blade can be both smooth or serrated. Another modern favorite knife is the karambit, a small, curved knife from Indonesia that resembles a claw. Originally used for farming, it later became a combat tool. Interestingly, you could say that it's a mix between the Spanish knife navaja (navaha) and a small curved Finnish knife. Some prefer a small Filipino dagger called a punyal.

David “Sensei” Stainko David “Sensei” Stainko

As a Martial

Some of the most wellknown military knives include:

• The M3 Trench Knife used by U.S. soldiers in WWII. This knife has a longer blade and a serrated back for better functionality.

• The Fairbairn–Sykes Commando Knife is known as being used by British commandos. It is a very sharp and effective knife.

• The Yank knife – Bert „Yank“ Levy began training Home Guard and SOE recruits in large-scale combat.

• The Kukri knife – from Nepal, a Gurkha soldier's knife similar to a smaller machete.

• The Yarara - Argentine parachute knife, knife of Argentine army since 1964.

• The Ka-Bar (USMC Mark 2) known for its long blade and leather-wrapped handle. This knife was used by the American marines.

• The Hitler Youth Knife (HJ-Messer) –a simple German knife given to Hitlerjugend members. This knife had a simple design with a foldable blade.

• The SOG Seal Pup Elite – praised for its toughness and functionality.

• The Emerson CQC-7, a favorite of special forces for its reliable folding mechanism for which it was popular among professionals.

Of course, apart from these knives, other military knives exist as well.

“Although most martial arts focus on teaching defense techniques against knife attacks, but many instructors also teach offensive knife skills”

Knives are used by military forces all over the world, and knife fighting is part of many armies’ martial arts training. Instructors often train with versions of the Buck or Bowie knife.

An interesting legal note: if someone holds a knife with the blade pointing up or straight ahead, it’s often seen as selfdefense. But if the blade is pointed downward and swung from above, that’s typically viewed as an attack.

Knives are mostly used in close-range combat, though there are also throwing knives. These types of knives appeared very early in some parts of the world- around 1600 in the East, in Europe, and the Americas. Early on, people used daggers rather than true knives. Today’s throwing knives are flat, double-edged, and sharply pointed. The key to a good throwing knife is that its weight is slightly shifted toward the blade, so it hits tip-first.

In 1400s old Japan, fighters used to throw small metal needles or mini-daggers called shuriken, and star-shaped metal weapons known as shaken (now commonly both are referred to as shuriken). Some martial artists even threw heavier knives like the sai dagger. In Africa, large throwing knives were used by various tribes, such as a multi-bladed version from Cameroon around 1700.

“The earliest human weapons were made from wood, stone, and bone. Later, with the discovery of metalworking, humans created more practical tools and weapons from bronze and eventually iron – like swords, axes, spears, arrows with metal tips, spiked maces, and of course, different kinds of daggers and knives”

Nowadays, knife throwing is mostly practiced by the military, police, or a few dedicated martial arts masters – and of course, mostly in circus shows as a part of knife attractions. A thrown knife spins around its length as it flies through the air and ideally lands point-first (daggers). Knife throwing is extremely difficult and it takes strength (a forceful thrust), precision in hitting the target, and a lot of practice to master.

Although most martial arts focus on teaching defense techniques against knife attacks, but many instructors also teach offensive knife skills. People have been defending themselves against knife attacks for centuries so different defensive techniques exist. For example, an old English method involved wrapping part of your clothing around your arm to block the attacker. In Argentina, there's a style of defense that also uses clothing to parry or entangle the opponent’s knife (a scarf, jacket, t-shirt or similar).They mostly use a dagger called a corvo.

“People have been defending themselves against knife attacks for centuries so different defensive techniques exist”

As a Martial As a Martial

Gypsies used to take off their sandal (sometimes slippers or shoes), put their toes in it with the thumb on top, and in this way, they tried to defend themselves from attacks and knife stabs. Also, many people instinctively place a bag (a briefcase or some business bag) in front of them, using it as a shield from knife attacks. The techniques of self-defense against knife attacks are indeed numerous. Some individuals who are armed with a knife actively defend themselves with it, using various knife-fighting techniques they are familiar with. Certainly, those who are armed with firearms and defend themselves from a knife-wielding attacker, for example with a pistol, are in the best position.

Although there are those who think that a sudden attacker will strike with a smaller knife or some kind of dagger, that is not really the case. Attacks with smaller knives or daggers are more often used in some gangster and street confrontations, as well as in certain prisons and similar settings.

According to some statistical data, most attackers use some variant of a Bowie knife, then various types of machetes, and only a smaller number of attackers use a smaller knife. Most attackers use a larger knife in order to more easily intimidate their victim. Also, by having a larger knife, they themselves feel more dangerous. These attackers usually do not actually know how to handle a knife properly. They mostly hold the knife tightly and rigidly in their hand, and during the attack they make a grimace and shout in order to further frighten their victim. If a person is calm and knows what to do, they can defend themselves from such attackers.

Those who truly know how to handle a knife will not be “attackers” at all, but will use their knife skills exclusively for selfdefense. Such people will hold the knife lightly in their hand, as if holding glasses, a spoon, a comb, or something similar. Their face will not be tense but relaxed. Many of those who have already been in knife fights will have visible scars on their hands or body. Most top knife-fighting instructors also have some prior experience from real close-quarters knife combat.

Although knife fighting is banned in many countries, there are still some countries in the world where this custom has survived to this day (for example; Argentina, Brazil, Albania, Philippines , Gypsies and some others). Secretly, hiding from the police and numerous curious onlookers, certain individuals meet in secluded places to test their skill and ability in knife fighting.

Among them are top experts, but also many adventurers — those who want to try out their skills without being aware of the dangers. Knife fights usually do not last long, on average from one minute to at most a minute and a half. So, if you are a “beginner” and lack sufficient experience in knife fighting, and do not have complete confidence in your fighting skills, you are an “adventurer.” To try your hand at knife fighting, in addition to great skill and courage, you must also possess a fair amount of “madness.” Do not engage in such an activity, because the consequences can be very dangerous. In other words, if you wish to experience something like this, make sure you are in the immediate vicinity of a hospital because you will need it. The question is not whether you will be injured, but only how life-threatening your injuries will be.

A knife attack or knife fight is certainly very dangerous. If someone wants to attack you with a knife — that is, threatens you with a knife — and you can leave or run away, do so immediately. This is not cowardice but a rational decision. The consequences of defending yourself or fighting against a knife attack are not worth the injuries you may sustain. So, when you see someone threatening you with a knife, leave if you can. If you must fight, do it cautiously, very calmly, and in defending yourself, show no mercy toward your attacker. It can also happen that some attackers might throw a knife at you. Most often, these are amateurs. If the knife is not specifically designed for throwing, it will not make the proper rotation in the air and will generally not turn with the blade toward you, nor will it be able to seriously injure you. If the knife or dagger thrown at you is not a proper throwing weapon, not only will you remain unharmed, but the attacker will have actually armed you further. Take a knife attack or a knife fight very seriously. Practicing knife handling, as well as training in certain martial arts, will certainly be of great help in defending yourself against a knife attack.

“Knife fights usually do not last long, on average from one minute to at most a minute and a half.”

David “Sensei” Stainko David “Sensei” Stainko

As a Martial As a Martial

Using a military knife requires certain skills and knowledge from the user. The choice types of knife usually depends on specific needs, field conditions, and tactical requirements. It is very important to know that each knife, according to its shape, has a different application in attack or defense. Depending on its purpose, some knives are designed exclusively for stabbing an opponent, while others are intended for cutting and slashing. Therefore, each knife has its own specific use in an attack. Some knives are better suited for delivering an upward strike, others for a downward strike, and some for a straight thrust forward. Accordingly, defending yourself against an attacker using a particular type of knife will always require a slightly different approach. This means you need to know how to adapt your defense to the type of knife your attacker is using. Although much more can be said about the knife as a combat weapon, I hope I have given you part of the answer to some common questions.

David „Sensei“ Stainko,prof. , 8thDan – Martial Arts Expert

“The choice types of knife usually depends on specific needs, field conditions, and tactical requirements”

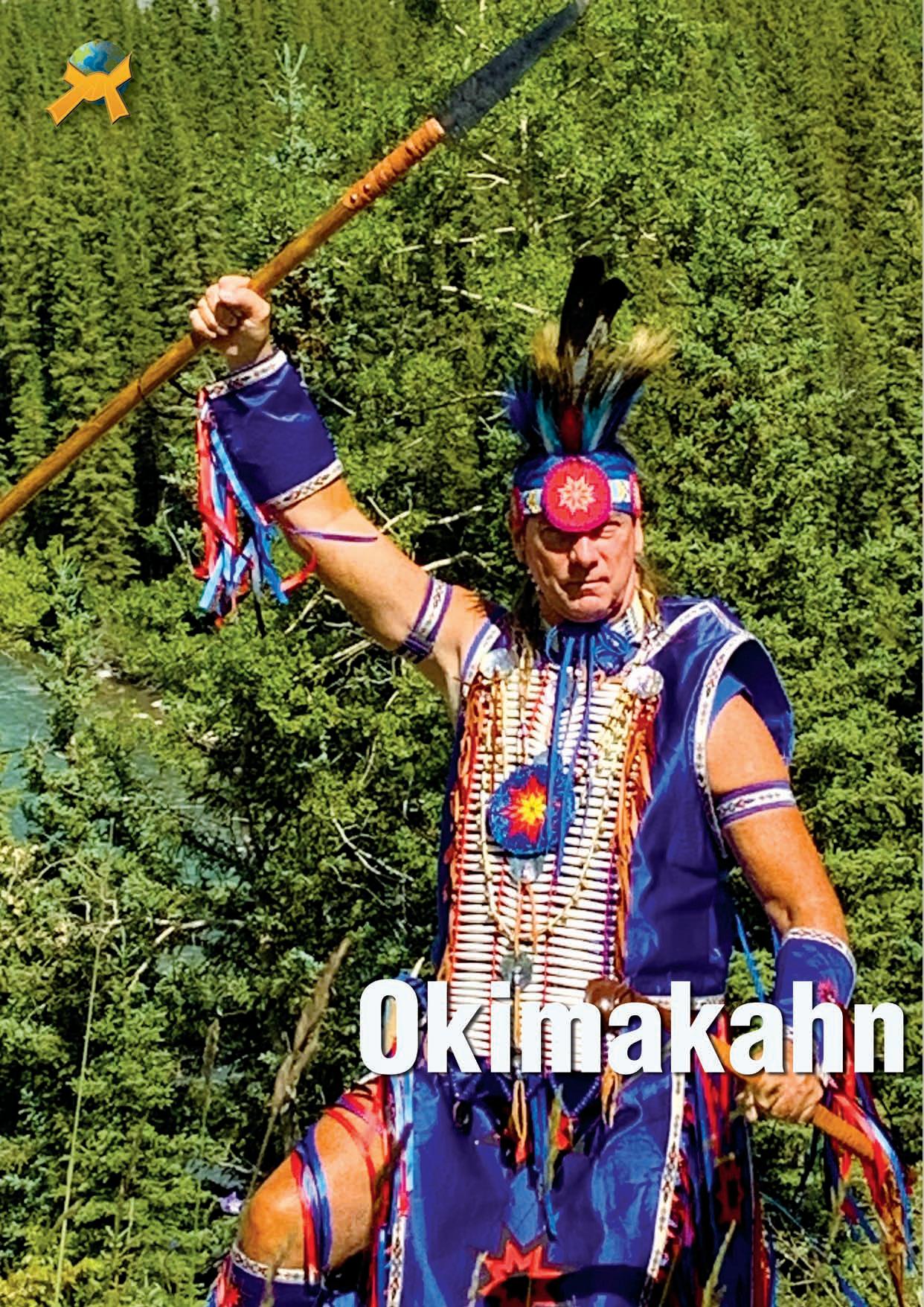

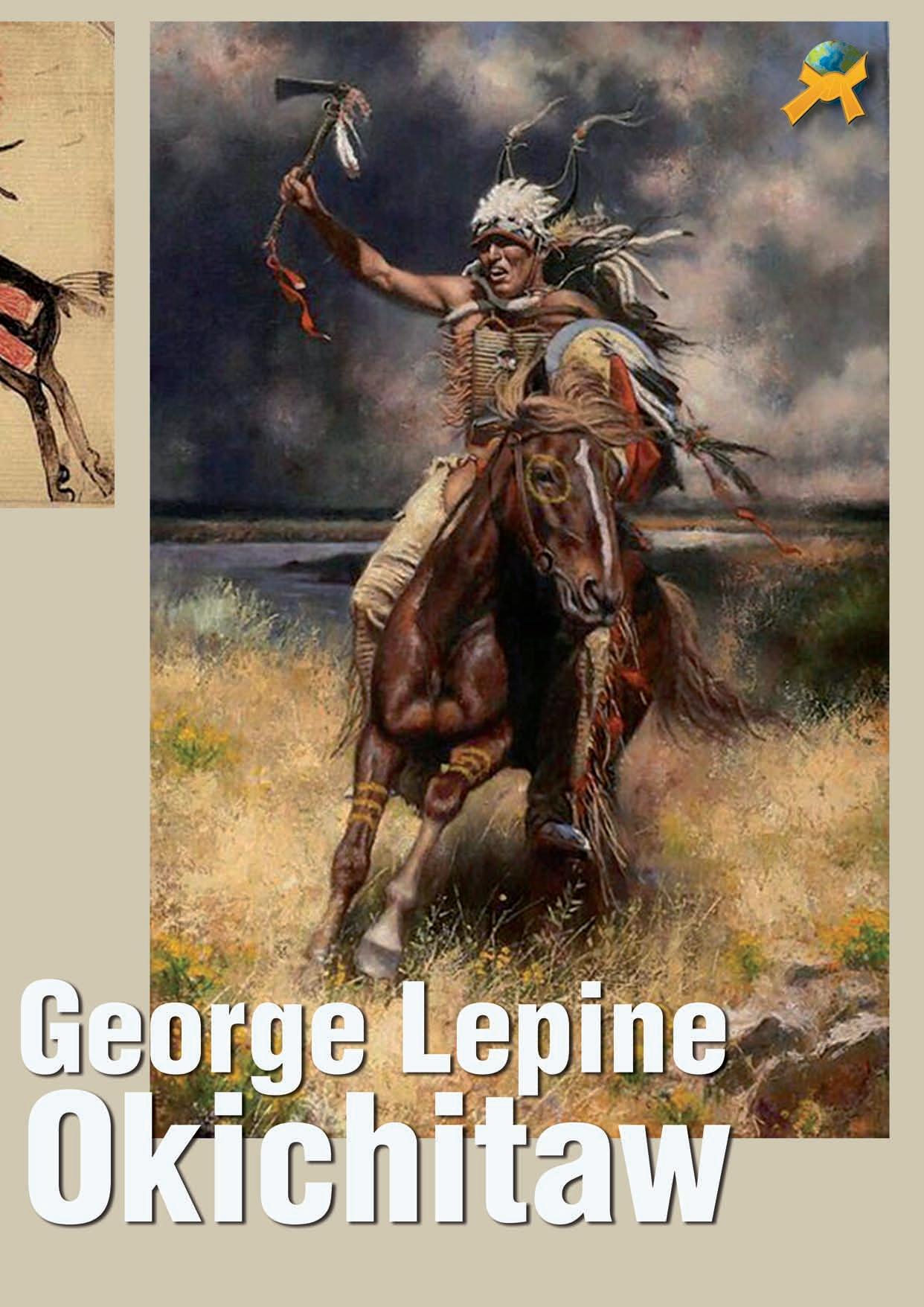

I have students that are new to Okichitaw as well as some non-Indigenous students where they have noted a particular interest in our history using the well-known "War Cry" applied during combative engagements of yesteryear. The depiction, display as well as audio impact of the "War Cry" from the Indigenous Warrior on the North American Plains has been recorded throughout history. It has also been provided in mainstream film as a form and application of entertainment. However, it is important that I explain this unique tactic not from an entertainment or amusement perspective, but rather from a tactical, spiritual and cultural one. The shriek of the warrior's cry in North America has been experienced by many who have effectively recorded it throughout a multitude of reports, journals, military entries, and of course from personal accounts.

This impacting verbal tactic as a result of our combative culture is somewhat similar to the shouting, screaming, and yelling applications of other military cultures and campaigns which have been recorded throughout history and around the globe.

It should be noted that Native American battle cries were quite unique to each tribe and region. These cries served as powerful expressions of unity, resistance, and intimidation which rallied Warriors to instill fear in their enemies during engagements. Our war cries were also noted to be quite diverse as well and aligned ourselves spiritually with our ancestors as we faced death. Everything from high-pitched shrieks to deep chants, or using the charging battle scream

could be in conjunction with loud expressions such as Plains-Cree Warriors yelling the words "Mo-ske-stam!" meaning to "Charge at Them!" or simply "Sisikoc!" which means to Attack!". Whether we conducted a sneak-up-guerilla form of attack, or administered an open frontal assault, our first goal was simply to declare our presence. The use of the war cry not only served as a powerful statement of our existence, but it also indicated that we strongly refused to surrender and thus remained committed to our task. The second concept of the war cry was to effectively intimidate our enemy with sounds all of which are meant to scare and disorient the enemy as well as display our personal power of bravery, and courage.

The psychological purpose of the war cry was also used to assist in pushing warrior morale within the war party and cultivate a very strong advancement of our Indigenous unity and our shared purpose. As I indicated earlier, one of the primary functions of the war cry was to frighten and effectively unnerve the enemy. This presented the enemy with the impression of overwhelming aggression and strength, all of which was assisted by adrenaline which increased our power output and the warrior's readiness before and during battle engagements. There are numerous historical accounts where the Indigenous war cry was so overwhelming, that it could cause the enemy to freeze or retreat because of their own fears in relation to fighting Indigenous Warriors.

Two such accounts where Indigenous Warriors used the War Cry at the same location are noted here. These events have been well documented, one of them occurred during the Pontiac's War in 1763 and the other happened during the War of 1812 – both of them took place in the area now known as Detroit, Michigan. I'll focus on the second event which occurred during the War of 1812. It was during the month of August in 1812 when the war cry of Native American warriors caused American General William Hull to effectively surrender and then abandon Fort Detroit on August 16th, 1812. The American's perception and their fears increased while they were surrounded by Indigenous warriors. This fear was additionally increased by the shrieking war cries of their adversaries which were released as they were hidden within the surrounding forest area. This impactful tactic alone, subsequently caused the American General and his soldiers to abandon Fort Detroit for fear of their lives.

A northern plains war cry known to be spoken by Crazy Horse has also been passed down through Lakota generations. This famous war cry associated with the "Battle of Greasy Grass" (commonly known as the Battle of the Little Bighorn) was yelled out by Oglala Lakota leader Crazy Horse during this famous battle. According to Lakota Oral Tradition, Crazy Horse yelled, "Maka-kecela-tehani-yanke-lo!", which in English means "Only the Earth lasts forever!" several times during the battle. This war cry served as a rallying call for warriors fighting during the period of 1876 to defend their people and land from the United States Army 7th Cavalry, which was led by Lt. Col. George Custer. The battle involved a coalition of Indigenous tribes which included some such as the Lakota Sioux, the Northern Cheyenne, and the Arapaho. During this battle engagement, Plains Indigenous war cries incorporated a high-pitched shrieking sound which came across constantly during the battle and would have been incredibly powerful and intense to experience. All of the participating Indigenous nations utilized the war cry during this aggressive battle which no doubt assisted in them achieving a decisive victory during the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Another item to note is in relation to Tecumseh who was a famous Shawnee Warrior. It is known that he said to warriors prior to experiencing combat, "Sing your death song and die like a hero going home". His statement and the application of the term "Death Song", a.k.a. "War Cry" was used by Tecumseh to encourage warriors to make sure that they live and die with purpose, and that a warrior should always face death with courage and honor without any regret whatsoever. This warrior philosophy in conjunction with the use of the War Cry was always powerful throughout Indigenous circles.

Even though much time has passed since Indigenous War Cries have been shouted and experienced in battle engagements, it is important to remind ourselves that the purpose of the Warrior's War Cry was also used to serve as a powerful declaration of our Indigenous presence. Nevertheless, our refusal to be conquered while we continued to embody various periods of resilience was displayed through the use of our War Cries.

In Unity, Chief George J. Lepine, Okichitaw Canada Okimakahn Kiskinahumakew / Chief Instructor / Yakanikinew Paskwawimostos / Pushing Buffalo Okichitaw Indigenous Combat Arts, History and Knowledge NATIVE CANADIAN CENTRE OF TORONTO 16 Spadina Road Toronto, ON Canada M5R 2S7

Tel: 416-964-9087 Cell: 416-566-3094

Email: okichitaw4@gmail.com www.okichitaw.com

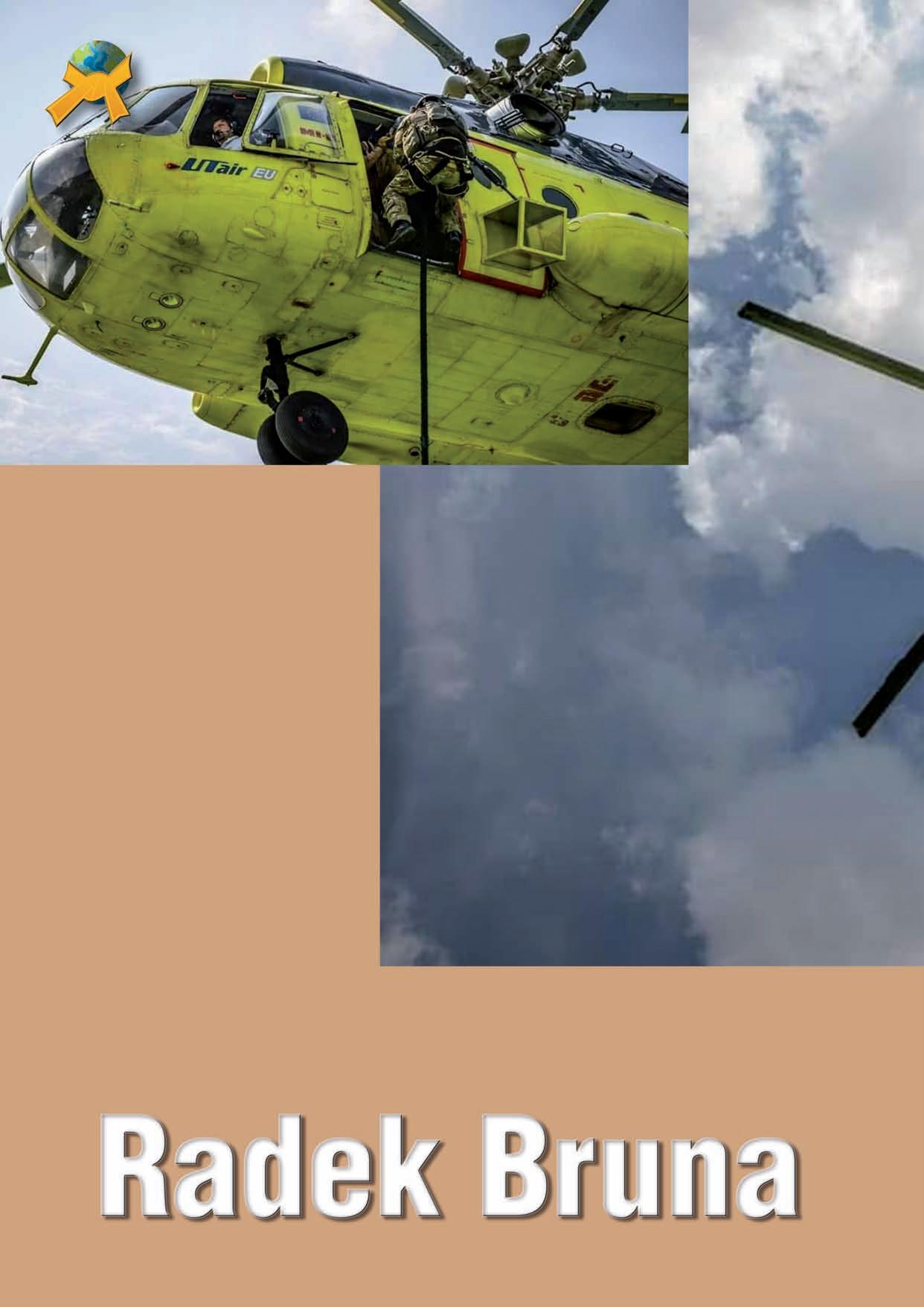

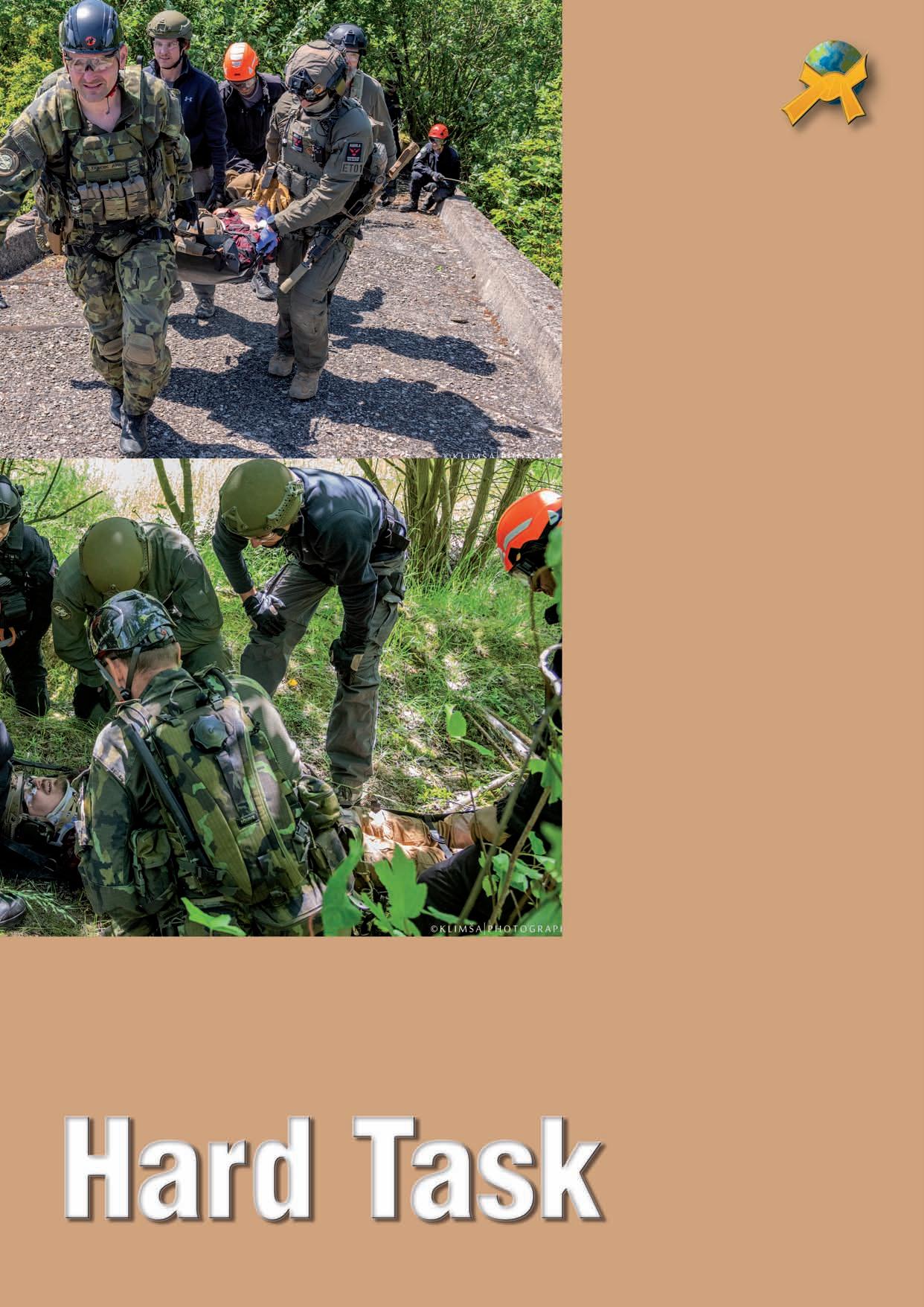

“In martial arts, we often equate our success with another’s failure. Many in Martial arts see their Objects Fail as their success, but during a recent visit to the Czech Republic’s Hard Task Air Assault Course, I discovered a philosophy that flips that thinking on its head: when one student succeeds, we all succeed. This isn’t just a slogan—it’s a principle lived and enforced by instructors from elite military units, fire rescue teams, stunt coordination, and aviation. Their unified mission? Teach students to conquer fear—not by avoiding it, but by meeting it head-on.”

Martial arts, success is often seen as individual—one fighter wins, the other loses. In Hard Task Air Assault Course in the Czech Republic, I encountered a different philosophy—one that stands in direct contrast to ego-driven competition: “Your success is our success.”

Here, instructors from vastly different backgrounds—military veterans, rescue personnel, helicopter pilots, and stunt professionals— form a unified team. Their shared goal? To push students to their limits in a safe yet mentally demanding environment where fear isn’t avoided but confronted, studied, and ultimately, mastered.

Hard training prepares you for hard tasks Missions. This philosophy drives the approach to confronting heights and fear, particularly as it applies to teaching martial arts and fear management. In the martial arts world, often loaded with ego, practitioners typically celebrate their own success while dismissing others’ failures. However, there’s an exceptional approach that stands out—one where another person’s failure becomes everyone’s success.

The most professional instructors in the Czech Republic have created an environment that amazed even seasoned practitioners. Their commitment to making all students successful, including those who initially failed, demonstrates an extraordinary team effort. These instructors and their entire team work tirelessly to help, push, guide, and direct students toward success. This collaborative approach represents something truly revolutionary in combat training.

The entire course operates under Hard Task company, led by head instructor Zdeněk Charvát. My self As a supervisor for presidential bodyguards, Made the connection with Hard Task spans many years across different tactical training programs. Hard Task provides comprehensive training including firearms, surveillance, tactical driving, VIP protection skills, hand-to-hand combat, and medical training under combat conditions—all delivered at the highest professional levels.

Significantly, almost all air assault instructors carry martial arts backgrounds and combat skills, with many being former specialized army and police unit members.

Hard Task Air Assault Course: A Unique European Experience thats now welcome also civilians and Martial artist.

For over a decade, the Czech training group Hard Task has been delivering a unique tactical experience through their Air Assault course, focused on helicopter-based insertions using fast rope techniques. This course, developed with operational realism and safety in mind, is among the very few—if not the only—civilian-run training of its kind in Europe, and possibly worldwide.

The Air Assault course launched in 2011, with early editions conducted on Mi8 heavy transport helicopters in cooperation with Slovak partners. Since then, Hard Task has hosted one to two courses annually, building a solid reputation for delivering helicopter insertion training with operational-level realism.

Now in its third season in the Czech Republic, the course runs in partnership with HELITOM s.r.o. All operations are conducted using the Eurocopter EC135, outfitted with the EAD03 External Load System by ECMS—a certified platform enabling fast rope insertions, static rope descents, and human external cargo transport.

Participants train with Marlow fast ropes and high-quality climbing and safety gear from Singing Rock, a renowned manufacturer of professional climbing equipment.

The course’s lead instructor is Wendy, a respected figure in the Czech tactical community. After graduating from Charles University’s Faculty of Law in 1983, Wendy joined the Czech Police as a criminal investigator. In 1990, he successfully passed selection for the Counter-Terrorist Unit, serving for 15 years and progressing from tactical team member to deputy team leader, then commander of the Special Intervention Group, and ultimately becoming a shooting, tactics, and special training instructor.

Throughout his career, Wendy completed numerous domestic and international training programs, working alongside elite units including Delta Force, SAS, SO19, RAID, GIGN, GSG9, Cobra, BBE, NOCS, and GIS. He holds specialized certifications in work at heights and jump master qualifications, participating in multiple live interventions against armed offenders. He also served in protective roles at the Czech Embassy in Baghdad.

After leaving the police in 2006, Wendy shifted focus to training, consulting, and security services, supporting governmental and armed forces in Kurdistan, Lebanon, Jordan, Libya, Iraq, Egypt, and the UAE. His extensive operational and international background ensures the course reflects real-world demands and best practices.

Supporting Wendy is a team of rope masters, paramedics, and rescue professionals, many bringing over a decade of experience from HEMS operations, fire rescue climbing teams, and tactical helicopter deployment. He also a Kapap Krav Maga and CDC Close Distance Combat.

The comprehensive two-day course combines theoretical preparation with live Helicopter operations:

Helicopter safety, operational planning, ground-based rope training (on a climbing tower), and tactical procedures in and around a grounded aircraft.

Live fast rope descents from 3 to 10 meters from a hovering EC135, tactical team insertions into prepared mission scenarios, and team extractions.

Though maintaining high standards and serious tactical content, the course welcomes a wide range of participants. Over the years, attendees have included military and law enforcement personnel from around the world, as well as reenactors, tactical enthusiasts, stunt professionals, and actors training for physically demanding roles.

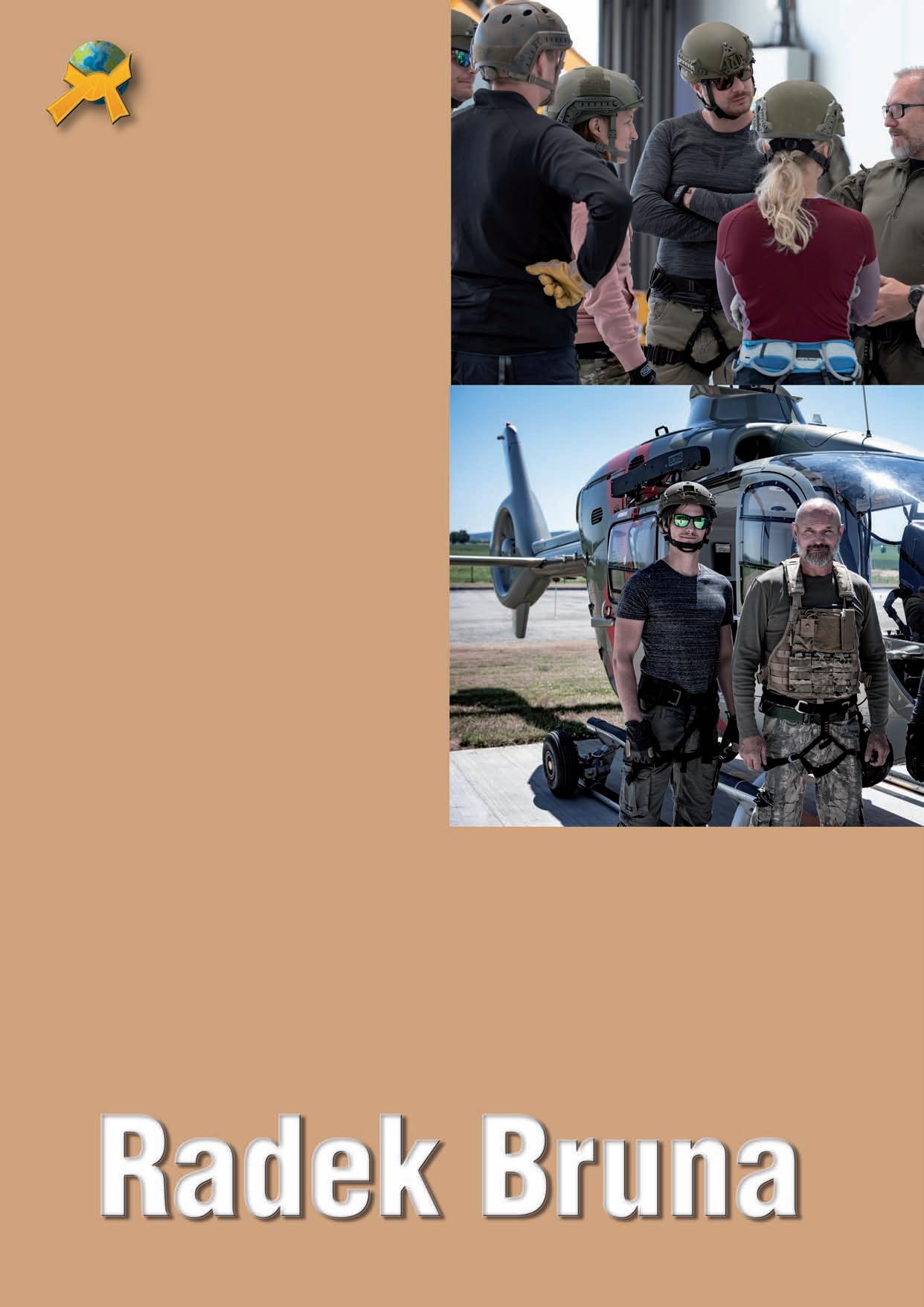

Radek Bruna: The Stuntman’s Perspective

One of the course instructors, Radek Bruna, brings a unique perspective to this training. With 26 years of experience as a stuntman and 11 years as a stunt coordinator, Bruna represents the intersection of professional film work and tactical training.

The Humble Professional

“You don’t see his face that often, but you do see his performances,” describes Radek Bruna perfectly. Despite being one of the most recognized stuntmen in the industry, he emphasizes that success is always a team effort, never his alone.

“I wouldn’t see it that way, I don’t really like acting for myself,” Bruna explains when asked about his fame. “I work in the FILMKA stunt team and even now I’m here more as a representative of Filmka and my colleagues than as myself, Radek Bruna.”

Bruna’s journey into stunt work began somewhat accidentally. As a young man on the karate national team who loved action movies, he would immediately try to learn the tricks he saw on screen. A chance call about a karate-themed washing powder commercial started his film career. From there, connections led him to stunt training and a meeting with Láďa Lahoda, marking the beginning of his film story.

Bruna has collaborated on approximately 250-300 film and advertising projects. His impressive filmography includes major Hollywood productions such as:

• Black Hawk Down - where he played sniper Clark from

Delta Force, a role that became a turning point in his career and inspired the creation of Filmka’s tactical department

• The Bourne Identity - showcasing his skills in this acclaimed action thriller

• Babylon A.D. - working alongside Vin Diesel

• Shanghai Knights - collaborating with Jackie Chan

• Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol - part of the renowned action franchise

• Casino Royale - contributing to the James Bond legacy

• The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

• Anthropoid

• Jojo Rabbit

He has worked with legendary actors including Tom Cruise, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sean Connery, Vin Diesel, Jackie Chan, Matt Damon, and many others.

Bruna was instrumental in creating Filmka’s tactical department, composed of former army and police special forces members, stuntmen, and crime writers. This specialized unit provides realistic police and military action for films, including consulting and training actors in shooting and tactical skills.

“Because we want to do our job 100%, we train as much as possible like real police officers and soldiers, so that our performance looks as realistic as possible,” Bruna explains. “There are police officers and soldiers in the audience, and they recognize it. We want these viewers to say: ‘Yeah, I liked this, it fits.’”

Bruna emphasizes that successful stunt work requires humility and teamwork. “This work is interesting and fun, but there is not much room for one’s own ego, which, I think, is quite similar to police and military special operations. One must be humble and not play the know-it-all.”

The fundamental principle guiding all their work is simple: “SAFETY FIRST.” Despite having a “slightly shifted instinct for self-preservation,” professional stunt performers never abandon safety considerations entirely. As Bruna notes, “We wouldn’t want a person without it, he is dangerous to himself and others.”

When asked if the job hurts, Bruna’s response is characteristically direct: “It hurts. Sometimes yes.”

The work extends far beyond simply falling or jumping in place of actors. As a coordinator, Bruna oversees all stunt actions on film projects, which can include chases, car crashes, fights, duels, shootings, explosions, falls, burning, rope work, fencing, and horse work. “We are simply a bit of film magicians,” he describes.

The Hard Task Air Assault course represents a unique convergence where professional film stunt work meets real-world tactical training. With instructors like Radek Bruna, who bring both extensive film industry experience and genuine tactical knowledge, participants receive training that bridges the gap between cinematic action and operational reality. This combination offers civilians an unprecedented opportunity to experience professional-grade fast rope training from helicopters, guided by instructors with extensive real-world operational backgrounds. For those seeking to push their limits under rotor wash, this training provides an experience as close to reality as possible outside of military service.

“The Hard Task Air Assault course represents a unique convergence where professional film stunt work meets real-world tactical training. With instructors like Radek Bruna, who bring both extensive film industry experience and genuine tactical knowledge, participants receive training that bridges the gap between cinematic action and operational reality.”

The course exemplifies the philosophy that hard training prepares you for hard tasks, whether those tasks involve creating realistic action sequences for major motion pictures or developing the skills and mindset necessary for real-world tactical operations. In both cases, success depends on professional instruction, proper equipment, rigorous safety protocols, and the humility to learn from those who have gone before.

The Hard Task Air Assault course remains one of the only opportunities worldwide for civilians to undergo professionalgrade helicopter insertion training, combining the expertise of seasoned tactical professionals with the practical knowledge of film industry veterans who understand both the demands of performance and the imperative of safety.

For Join Contact Hard Task: https://www.hardtask.cz/eng/intro

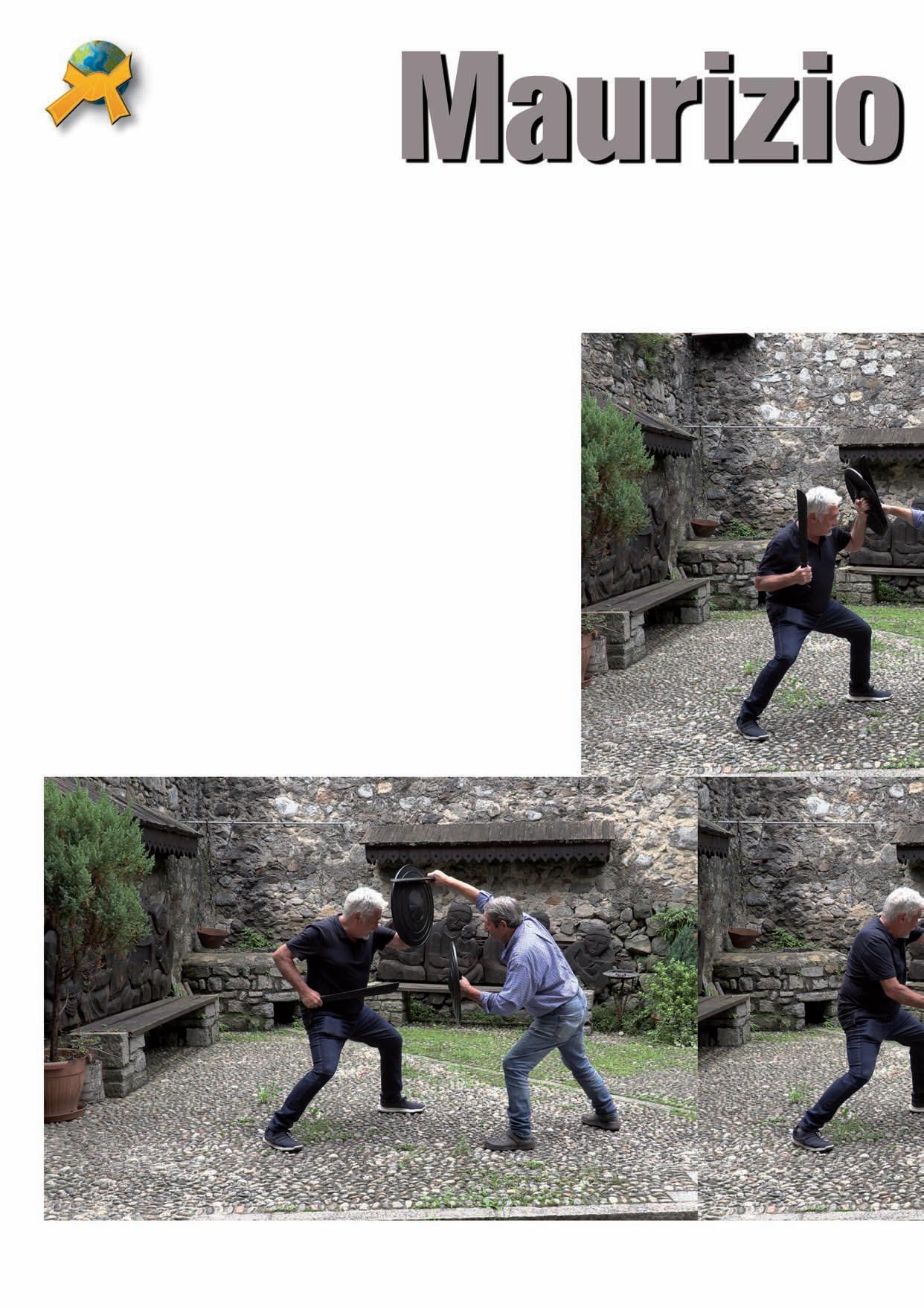

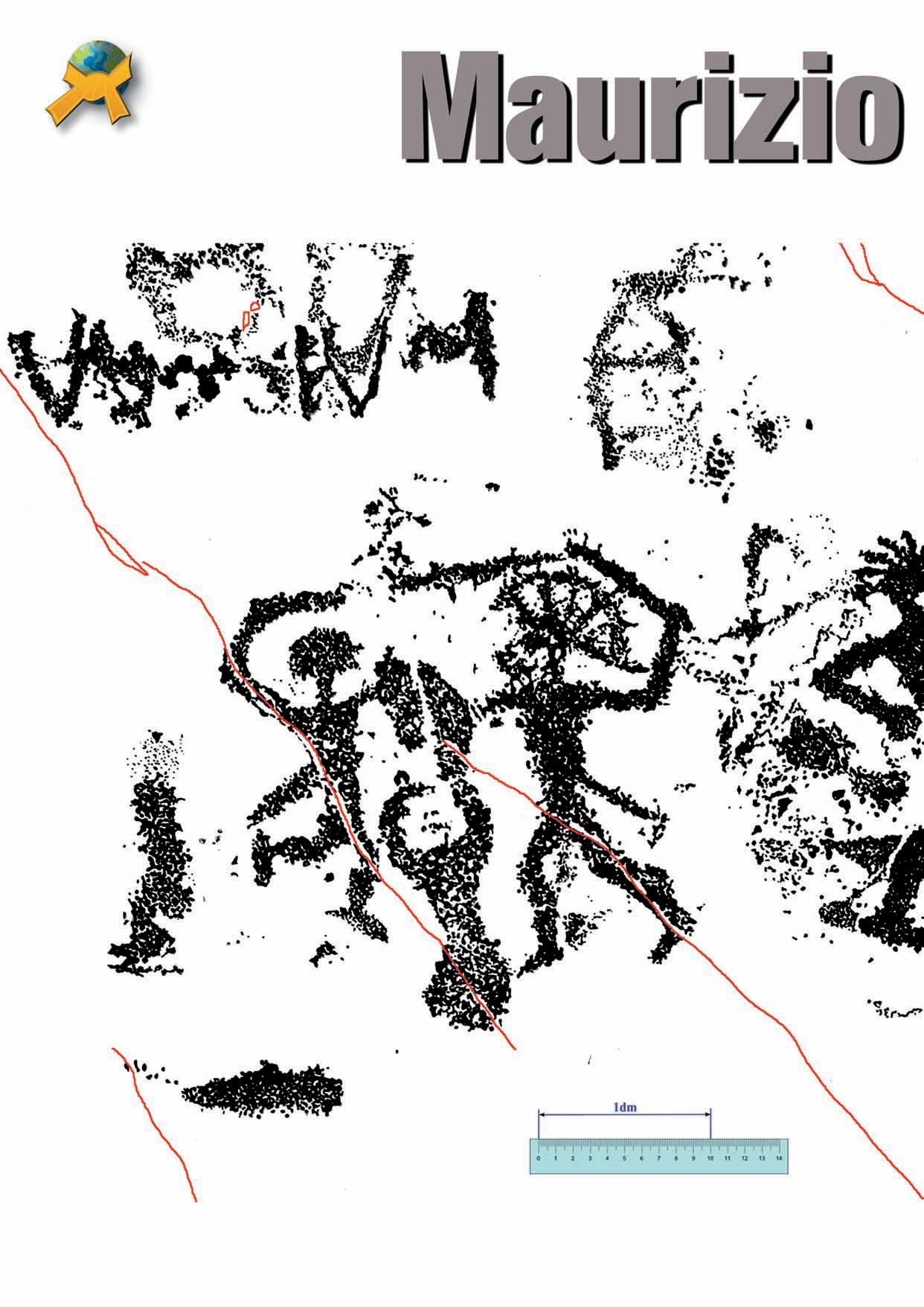

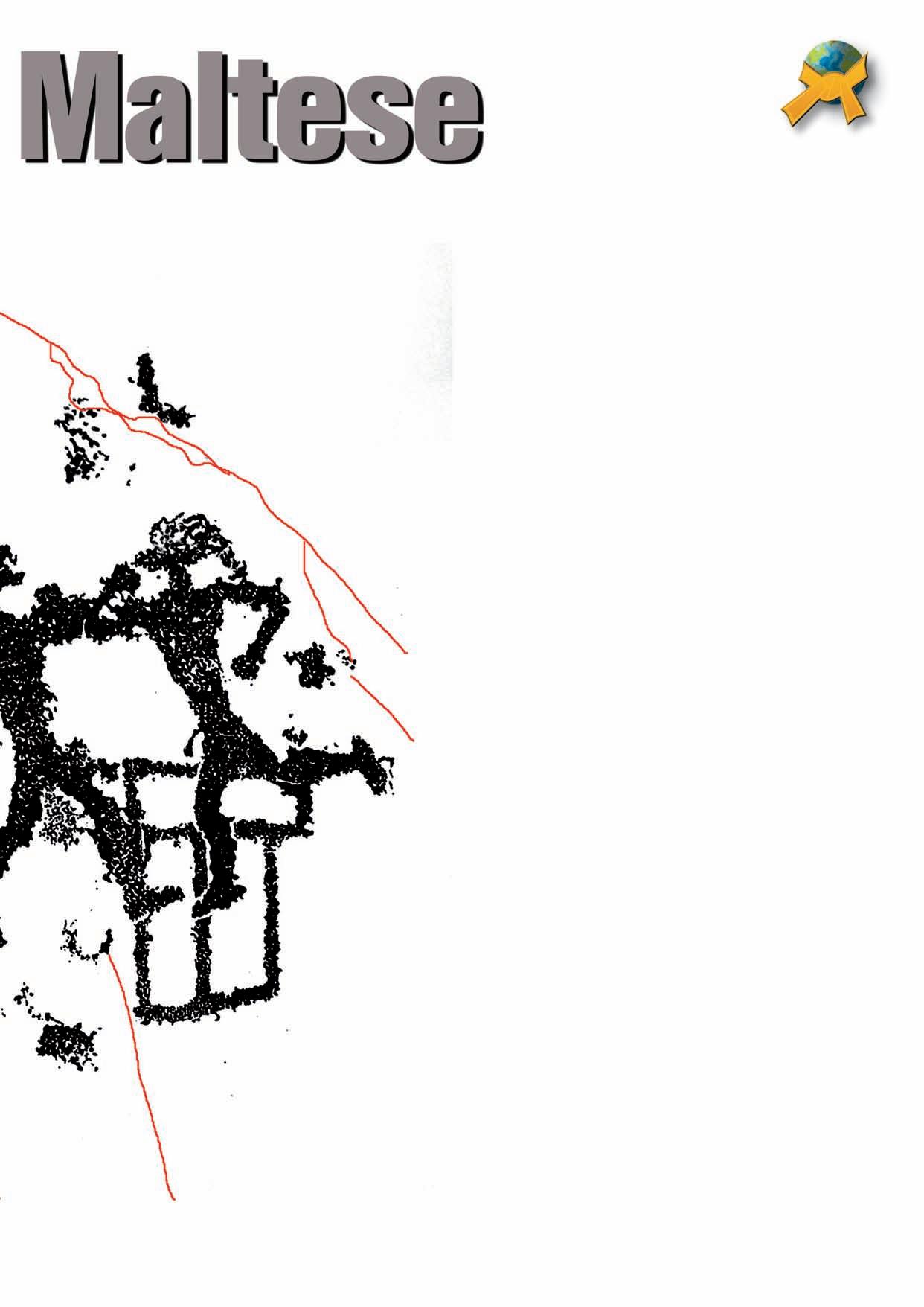

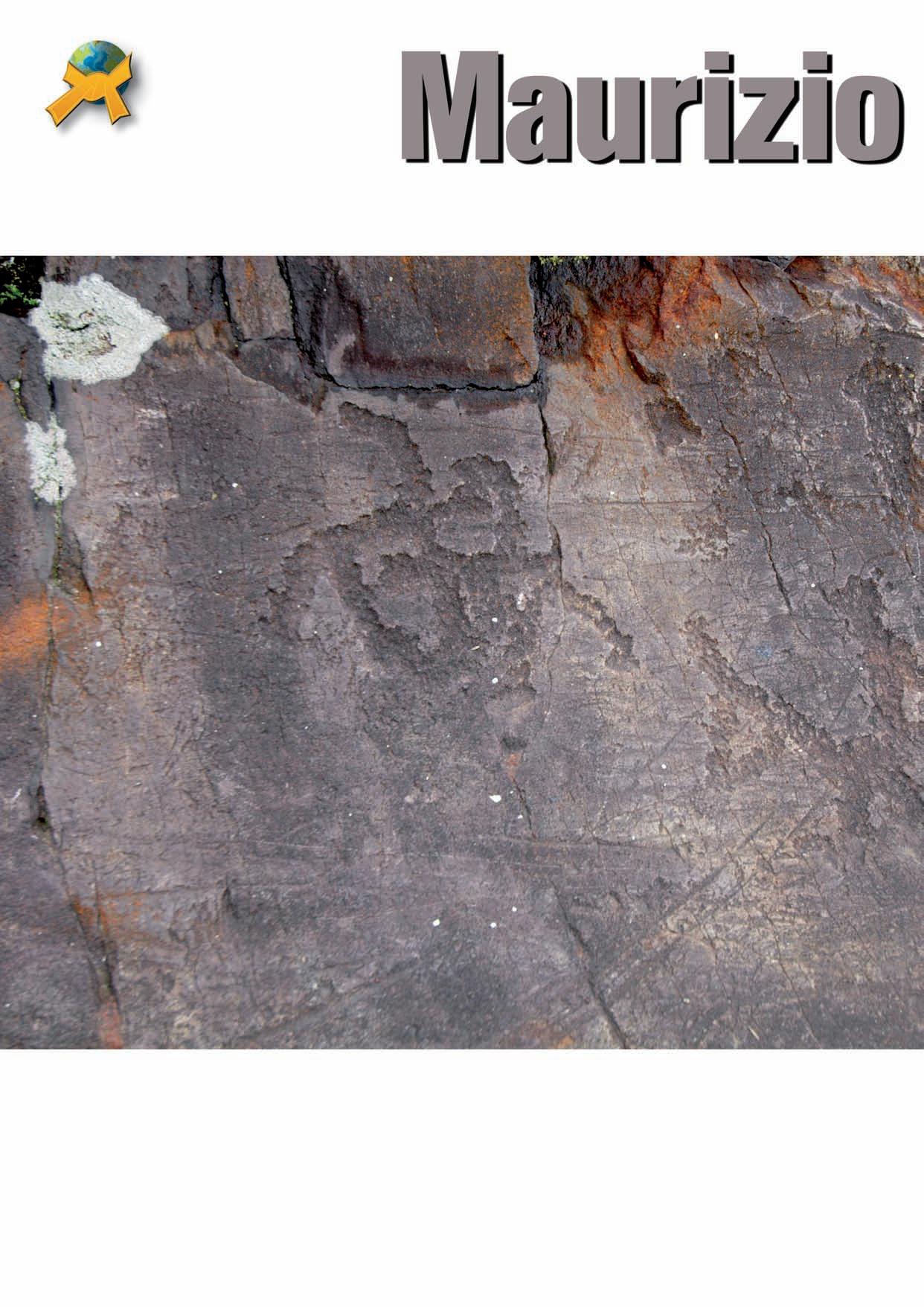

A dozen years ago, a friend asked me if I could help him decipher some rock carvings depicting scenes of duels. These carvings had been catalogued by academics as “the warriors.” Val Camonica, in northern Italy, the first site in the world recognized by UNESCO, is rich in such depictions. My first reaction was a polite refusal, but later, given my friend's insistence, I decided to try to analyze some of them. It wasn't the first time I had delved into the past to attempt

a technical recovery of martial arts, but I had never gone further back than the Middle Ages. I didn't like to proceed by making assumptions and developing hypotheses that could not be validated by written documents. Facing the period from the Neolithic to the Iron Age with engravings as my only source, I thought I was making a futile effort. I was wrong.

Little by little, those ancient depictions began to reveal their potential. Those who had engraved them must have had a clear understanding of the martial meaning of the gesture, and equally clear was the biomechanical function that led to the effectiveness of the action imprinted on the rock.

It took years, but I finally managed to form a complete mental picture in order to offer experts, especially archaeologists, the tools to interpret the martial positions and actions skillfully engraved on those cliffs.

First of all, we can see that the warrior's main weapons are depicted: the shield, sometimes round, sometimes rectangular, used in combination with a spear or sword. At other times, the figure depicted seems to be wielding a flexible weapon such as a long whip, used either alone or in combination with the shield. Knives are also present in large quantities. The shape of these weapons is very similar to that of the Indian weapon used in Kalari Payattu, with a wide triangular blade designed to strike mainly with the tip and a handle designed to prevent the weapon from being accidentally lost during use or to make it difficult to disarm.

Axes also feature prominently in these images. That this tool is used for martial purposes can be deduced from at least two factors: the first is that the other hand (usually the left) holds the shield, and the second is provided by the opponent depicted, who is also armed and facing him. It goes without saying that if I use an axe to chop wood, I don't take a shield with me, nor do I stand in front of another equally armed man.

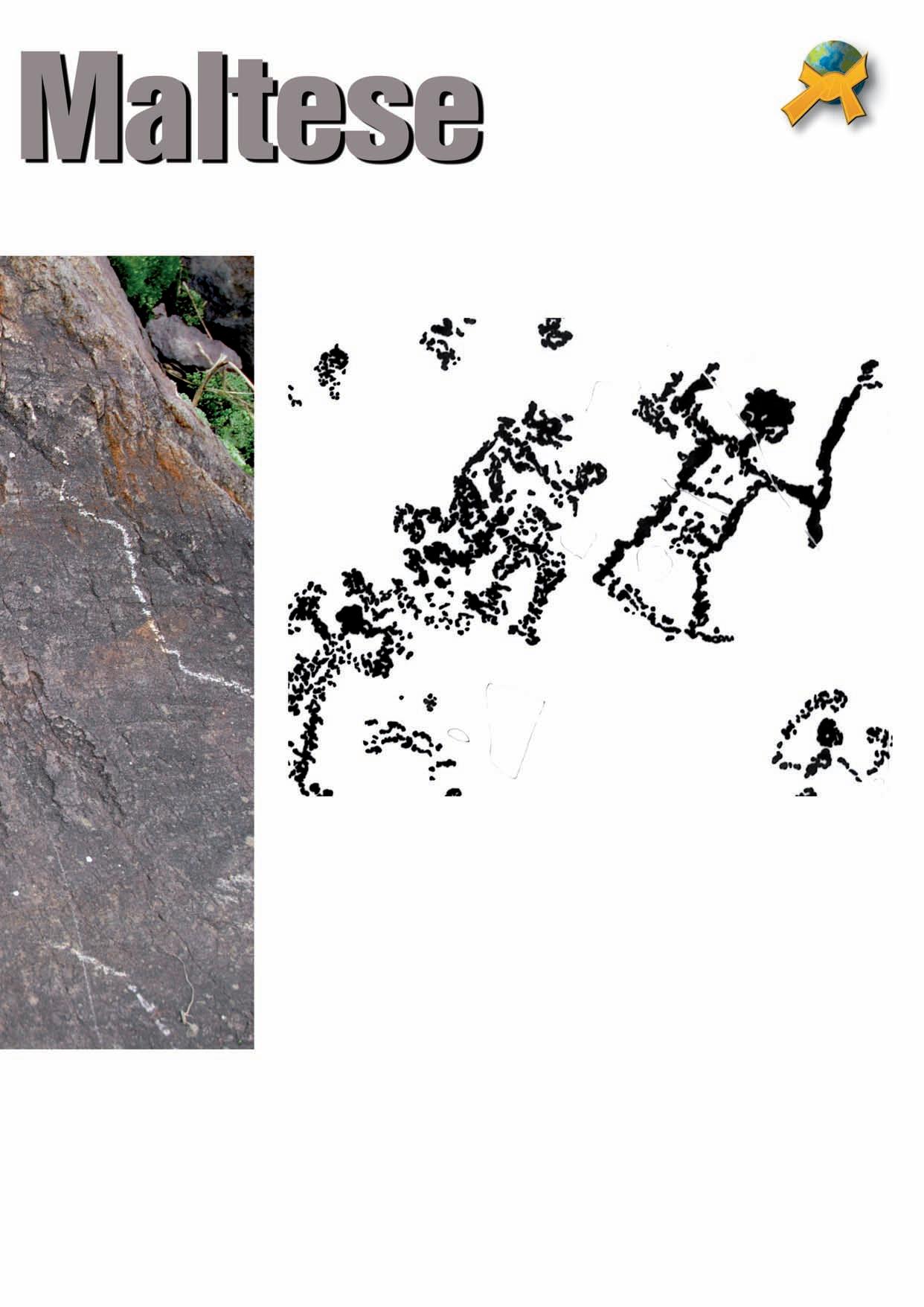

There are also scenes of hand-to-hand combat, both with fists and depicting actual wrestling holds as we understand them today. Let's start with the first image, entitled ‘The Boxers’.

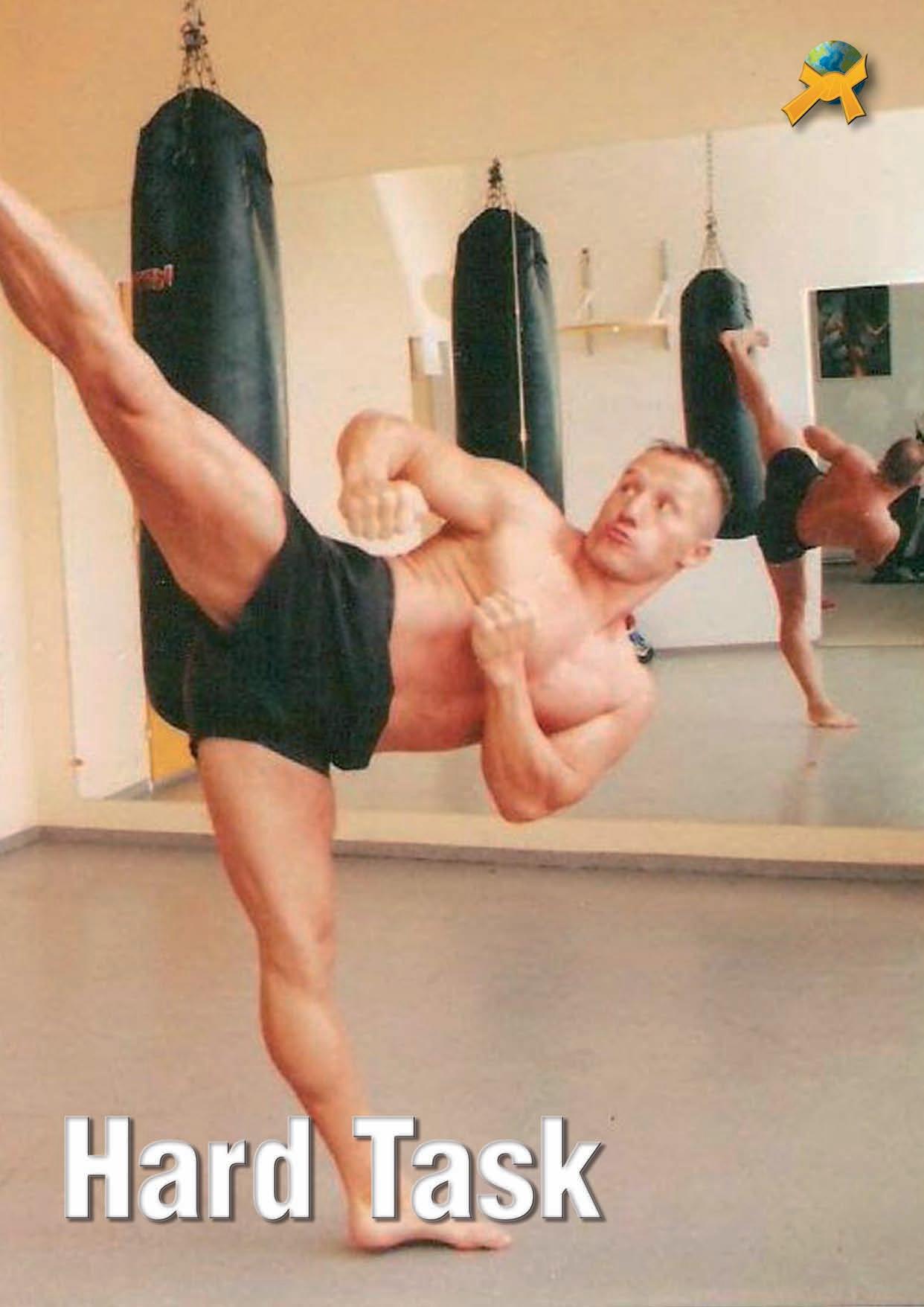

Any martial arts expert, and in particular those who practice Southeast Asian disciplines, will recognize the movements typical of Thai Muay Thai, Malaysian Tomoi, or Burmese boxing.

Analysis of the movement imprinted in the rock reveals extraordinary technical knowledge:

The scene depicts two boxers in combat. We can see that the boxer to the right of the viewer:

1) is in the process of attacking. His body weight is shifted onto his right leg, which is forward, while his left leg is raised.

2) The attack appears to be delivered with his right elbow in an upward trajectory (elbow uppercut).

3) His left arm is in the process of preparing a follow-up blow after the first.

4) The illustration highlights the momentum phase, necessary to shorten the distance just enough to strike the opponent with the elbow, presumably to the chin.

Let's move on to examine the defensive action:

1) The boxer on the reader's left has his body weight loaded on his right leg, which is behind him.

2) The defender blocks the blow with his left forearm, holding it horizontally.

3) The forcefulness of the attack can also be inferred from the fact that the defender's left leg is raised or resting on his left heel due to the impact.

4) The right arm is in the charging phase in a position similar to that of the attacker.

“Any martial arts expert, and in particular those who practice Southeast Asian disciplines, will recognize the movements typical of Thai Muay Thai, Malaysian Tomoi, or Burmese boxing.”

1) We can assume that the boxers assumed a left guard (the left side is forward).

2) It could be thought that at least one of the two fists in the charging phase was positioned on the side, as is still the case today in Chinese kung fu, Japanese karate, and Korean taekwondo schools (to name a few).

3) The attacker, in order to give more force to his elbow strike, presumably takes a sudden step forward, charging the

elbow strike with the momentum of the forward movement of the right side.

4) Both knees of the two combatants are bent, which suggests the existence of a “school.” Anyone who has attended any martial arts course, Eastern or Western, is well aware of the difficulty of keeping the knees bent. This is a posture that is learned through long practice.

“We are sometimes led to believe that the world before written records was populated by ‘anthropomorphic apes’ guided only by base instincts. Rock carvings, however, have gradually allowed us to reevaluate our distant ancestors. First of all, we note that, on a psychomotor level, these men of the past may have had greater abilities than modern humans.”

One of the most interesting fighting scenes depicts a duelist lunging at his opponent, grabbing him by the leg and throwing him to the ground. We note that the other is armed and is off balance. Another image seems to depict the opponent being thrown onto the hip, as is used in almost all fighting systems around the world and which judoka will recognize as the technique called O goshi.

We are sometimes led to believe that the world before written documents was populated by “anthropomorphic apes” guided only by base instincts. However, rock carvings have gradually allowed us to reevaluate our distant ancestors. First of all, we note that, on a psychomotor level, these men of the past may have had greater abilities than modern man. They had fewer tools at their disposal but greater psychophysical abilities, and it could not have been otherwise, since survival in a hostile and dangerous environment, such as we can imagine, was linked above all to their ability to move, their reflexes, and above all their fighting skills to defend themselves from both ferocious beasts and other men. In this regard, it should come as no surprise that from the images that have come down to us, we can deduce the existence of a real school in which those who knew more took on the role of teachers and, as we see in the depictions, encouraged others to practice. We can even imagine that, in the first social groups, a sort of specialization began, in which the most gifted were trained to become warriors, while others were mainly assigned to farming or other tasks.

Biomechanical and strategic functions have not changed much since then. If there has been a significant change, it is in materials and technology, but the way of wielding an axe, a shield, a sword, the way of throwing a punch or an elbow strike, or making a grab to unbalance an opponent does not seem to have undergone any major changes.

The depictions show shields, swords, daggers, spears, axes, fighting scenes with throws to the ground, punches and elbow strikes, but I have not seen a single kick. Kicks and knee strikes are absent. There are at least three possible reasons for this:

1. Often, in those mountainous areas, the terrain is steep, so it is better to remain steady on both feet rather than kick while balancing on one foot on an inclined and uneven surface.

2. The often rainy climate makes the rocky ground very slippery, as are the short grassy areas.

3. The habit of using shields and long weapons such as swords and axes does not make kicking easy.

I would like to thank Professor Mila Simoes de Abreu of the University of Villa Real in Portugal and the director of the Centro Camuno Studi Preistorici museum, Dr. Tiziani Cittadini, for giving me access to the study material for this article.

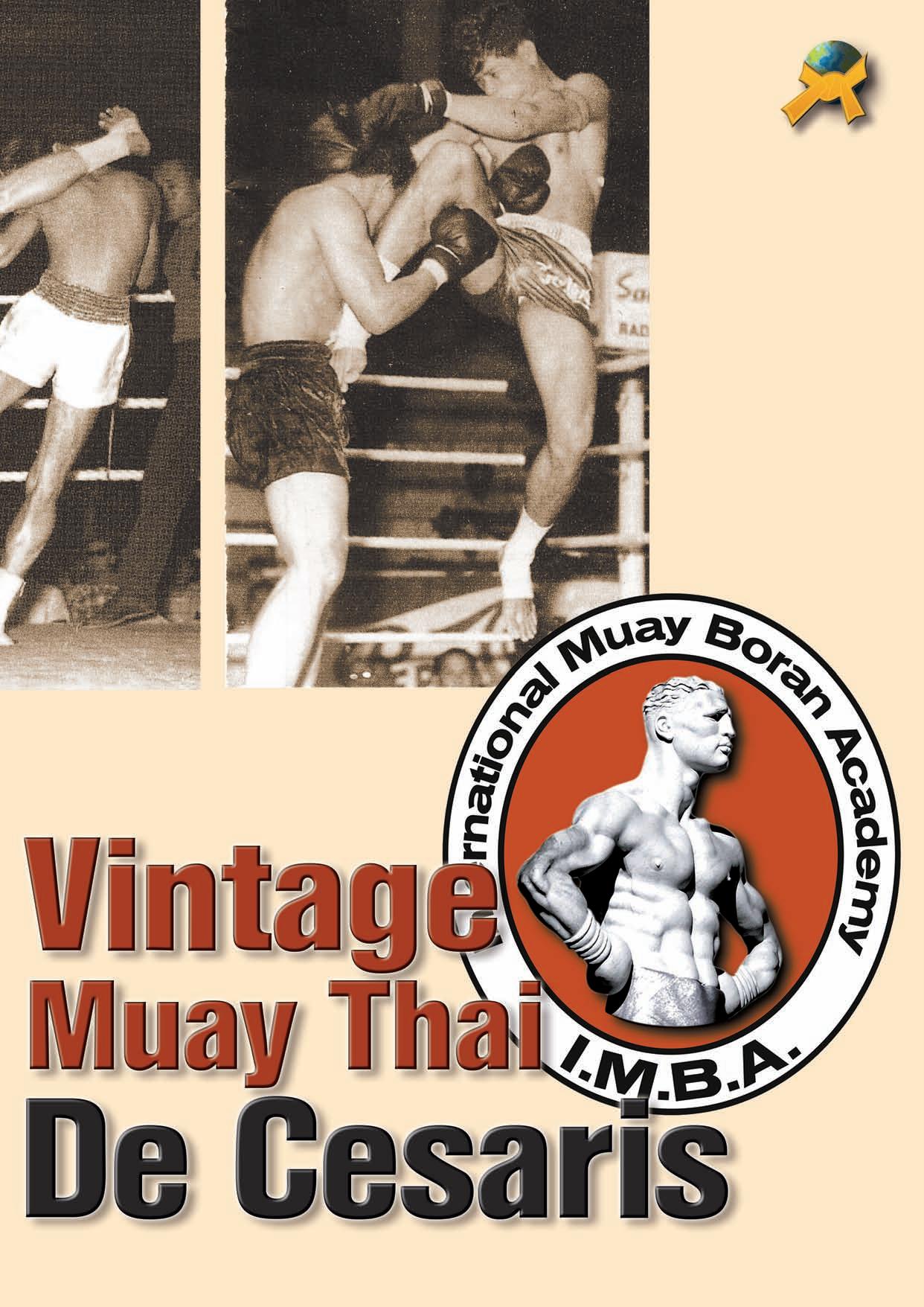

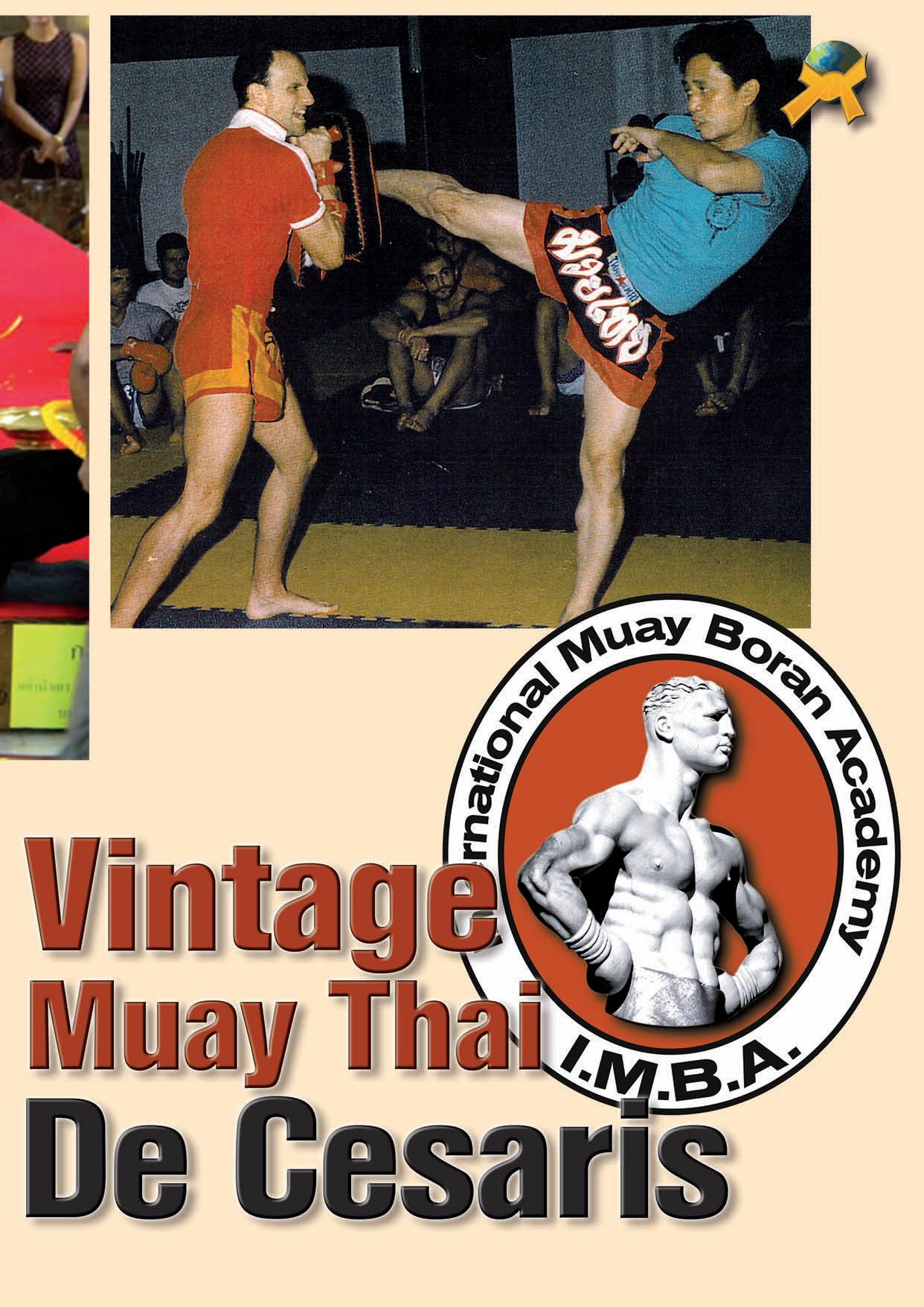

Vintage Muay Thai.

Vintage: denoting something from the past of high quality, especially something representing the best of its kind. Vintage is a word that can have several meanings. Its primary definition is “of old, recognized and enduring interest, importance or quality.” It is usually associated with the quality of aging, enduring or improving over time.

Muay Thai is a Martial Art with a long tradition, dating back hundreds of years. The origins and primordial history of this art are unknown; however, researchers trace back the periods of development of Muay from the 13th century onwards. The traditional classification of the history of Siam (that became Thailand in 1949) is based on five Eras; each one of them is identified by the city elected capital at that time. According to this classification there was a prehistoric Era or pre-Sukhothai, a Sukhothai Era, an Ayutthaya Era, a Thonburi Era and Rattanakosin Era; this last one is commonly divided into 3 Ages (ancient, middle, and late). Muay Thai went through many transformations along the centuries going from a purely battlefield skill to a wellregulated sport. The much appreciated fighting sport we know today is the result of the mixing of ancient Muay with western Boxing: this mix was created in the course of a few decades, during the middle and late Rattanakosin Era, that is roughly from 1909 to 1970. Conventionally, this period corresponds to King Rama VI to early King Rama IX reign. According to many scholars, a “vintage” expression of Muay Thai corresponds to this specific time-span. Let us see why.

During Rama VI (king Mongkut) reign (1909-1924), Muay went through a transformation that led to the future development of this Art. In fact, the very first permanent boxing stadium was erected (Sanam Muay Suan Kularb) in 1921 and boxing matches were organized on a regular basis. Boxers still wrapped their hands with raw cotton ropes, fighting with the old Muay Kard Chiek rules. In this period western boxing gloves started to be used and the rules and regulations slowly became stricter, aimed at defining a new approach to fighting, less brutal and extremely spectacular. The introduction of western Boxing was not welcome at first: however, trainers and fighters accepted the new “companion” and little by little absorbed the elements that could upgrade their technique and training methodology. Every camp structured training sessions according to a more modern approach: proper dieting and functional fitness programs were developed and training equipment borrowed from western Boxing started to be employed by all teachers.

In Rama VII (king Prachathipok) period (1924 to 1933), two more stadiums were established: Sanam Muay Lak Muang and Sanam Muay Ta Chang. In those years several textbooks were written by prominent teachers of the time, outlining a martial art in full evolution: this process didn’t stop then and it is still on at present time. According to many experts this evolutionary capability represents the real strenght of Muay Thai. In 1929 the use of boxing gloves was declared mandatory: the death of a boxer caused by the head punches he had suffered in the course of a Kard Chiek fight brought to the final decision of banning rope binding. Since then, the ancient style of hand wrapping started to slowly disappear until becoming a part of the attire used in Muay demonstrations.

Rama VIII (king Anandha Mahidol) (1933-1945). Before World War II Muay Thai was for many years in a quiet phase. Bangkok Rajadamnern Stadium’s foundation was ordered by former Prime Minister Pibulsongkram. The italian “Imprese Italiane all’Estero” company won the construction contract to build the stadium in 1941. The foundation stone was laid on March 1st (the definitive, well-equipped stadium was completed in 1951). Later on, at the end of 1944, an attempt to revive Thailand’s national sport was initiated and in August 1945 after the war ended the revival was in its full swing. Rajadamnern Stadium was renovated: by the end of that year boxing matches were once again held there. This could be counted as the true starting point of the modern age of Muay Thai.

Those years saw the great transformation of an ancestral fighting discipline that evolved into a modern sport. But what happened to the old styles of Muay that evolved independently in each regions of Thailand and made the history of this Art before modernity changed it? The four principal regional styles are Muay Lopburi (central Thailand), Muay Korat (north east Thailand), Muay Chaiya (southern Thailand) and Muay Ta Sao (northern Thailand). The researchers agree that during Rama VI to Rama VIII periods all these local styles went through a systematic transformation that aimed at adapting the old martial techniques and fighting strategies to the new situation. In fact these years are labelled as “development” or “changing” period by the followers of traditional styles: Muay Thai changed from Boran to Modern.

Thai people are very pragmatic: when the needs change, the tools must be changed accordingly. For this reason, all of the main regional styles adapted their skills to the new necessity of competing with rules and regulations they had never used before. The result was that many of the techniques that had made Muay stylists famous along the centuries, slowly started to be abandoned because they were considered obsolete. In order to win fights while following the new rules, practitioners of old styles had to focus on a few effective techniques that guaranteed the best results. The famed Pla Kat style of fighting started to be abandoned: Pla Kat or fighting fishes attack and quickly retreat more and more times until the opponent is defeated. Before the introduction of boxing gloves, many Nak Muay Kard Chiek (fighters) employed the same strategy to strike and rapidly get back to a safe position, thus avoiding with quick footwork a possible counterattack. Along the years, the “new” approach tended to a more solid footwork that allowed to unleash strikes charged with more power. This attitude was similar to the one used by fighters from Nakhon Ratchasima province (Korat): in fact, that period witnessed a long series of successful performances by Muay Korat boxers, since their style was already well suited to incorporate the new regulations. One of the trademarks of modern Muay Thai, the famed Tae Wiang (swing kick) was borrowed

from Korat boxers; in a short time it proved to be one of the most effective kicking techniques that could be used in modern competition and most fighters and teachers adopted it. Punching techniques coming from western Boxing were by far the best ones when fighting with boxing gloves on. Thai fighters tended to rely on lower limbs (knee and lower leg) and elbows to attack: since the introduction of big boxing gloves they were forced to re-structure their style and they had to “learn” to use the new piece of equipment. Without presumption, they studied and eventually learned the new way of the gloved fist without forgetting some of the old hand blows such as the fisherman punch, the open hand strike and the back fist. The so called fisherman punch was actually a hammer punch that boxers used to attack the collarbones and the crown of the head. The palm or heel of the hand blow was a common technique both in Kard Chiek fighting and in military close combat. The back of the hand was used to unleash wide horizontal swings or short downward strikes: the former aimed at the side of the head while the latter was employed to attack the bridge of the nose from a close distance. Drawing on their vast experience, in a few years the best thai teachers devised a superb new fighting art that combined the best of two worlds: the ancient Art of Siamese warriors and the modern Science of western athletes. Thai Boxing was starting its long journey to the top of the world of fighting sports.

Even if Thai Boxing is a wonderful hybrid that found its place among the most spectacular sports, it cannot be denied that during the years of the great change from Muay Kard Chiek to Thai Boxing, for a brief time-span, fighters showed the best of two worlds: the ancient one (still linked to old Muay Boran) and the modern one (resulting from the mix of western Boxing and traditional Muay). For modern practitioners and especially for all Khru Muay, the study of the training systems, fighting strategies and special techniques of the great thai fighters of that time has the greatest value. Vintage Muay Thai represents a precious technical heritage that must not be lost no matter what direction Thai Boxing will take in its future development.

For more information please visit IMBA official website: www.muaythai.it

“Even if Thai Boxing is a wonderful hybrid that found its place among the most spectacular sports, it cannot be denied that during the years of the great change from Muay Kard Chiek to Thai Boxing, for a brief time-span, fighters showed the best of two worlds”

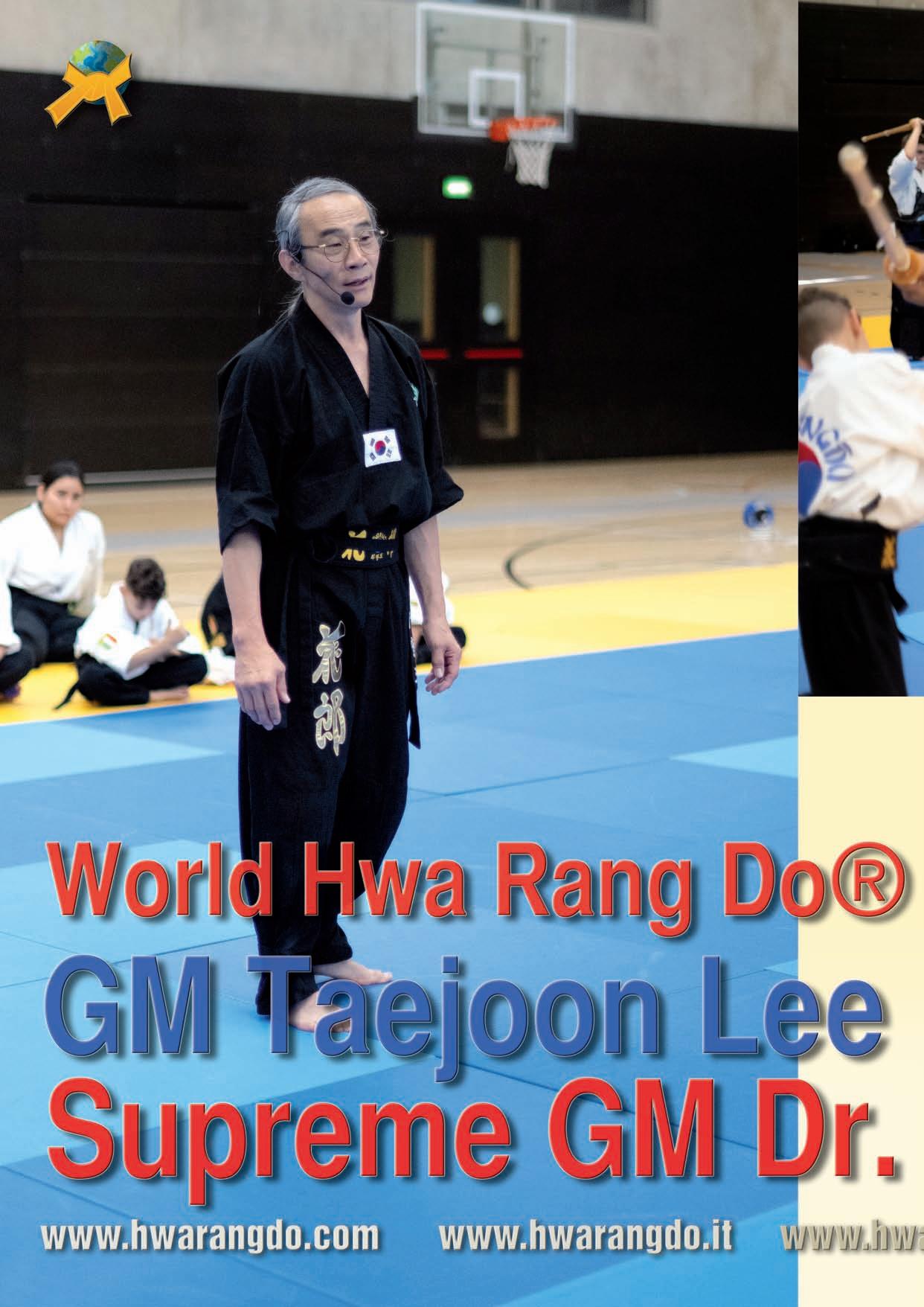

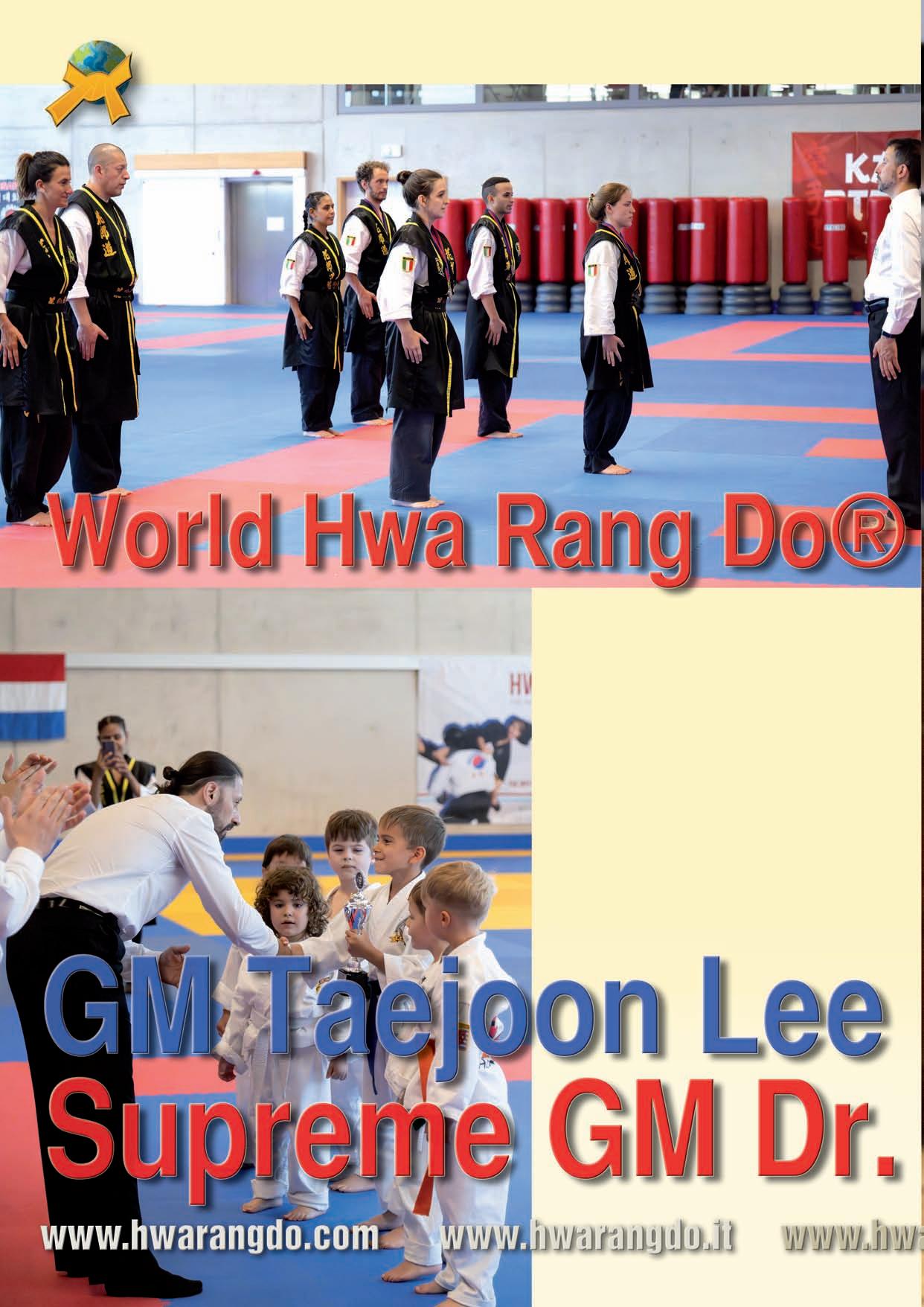

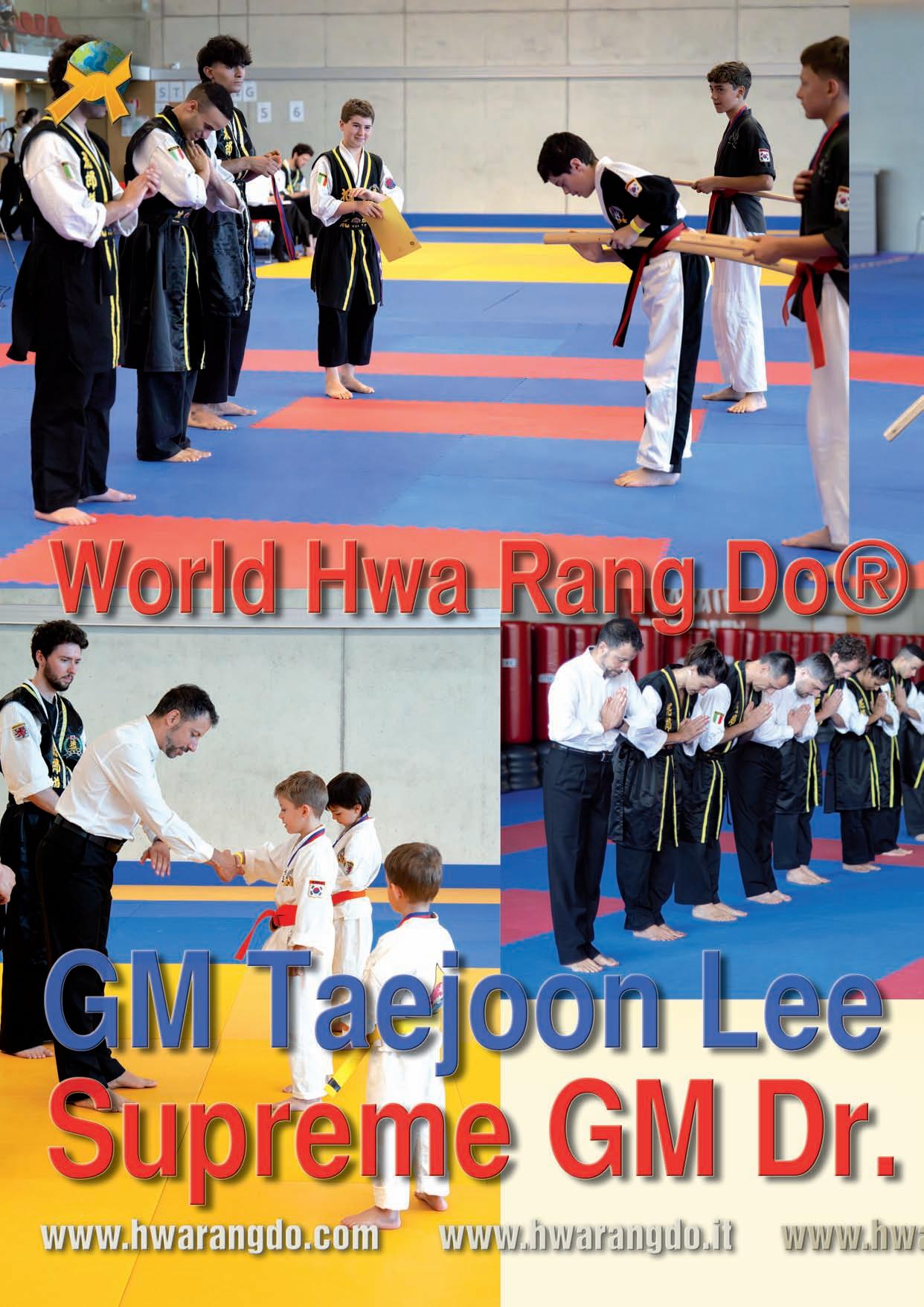

Hwa Rang Do® Annual

In an era where martial arts are too often reduced to a narrow frame—whether dazzling but empty choreography for action films, a checklist of techniques to display, or the cutthroat atmosphere of competitive sport—Hwa Rang Do stands apart as something far greater. It is not merely a system of combat or a set of skills to master; it is a way of life. To practice Hwa Rang Do is to embrace a path that shapes the body through relentless physical discipline, but also to refine the mind and spirit through deep questioning, honest reflection, and continual renewal. It offers more than the pursuit of strength or victory—it provides a framework for living fully, guided by courage in the face of hardship, honor in our actions, and humility in our growth. In this way, Hwa Rang Do becomes not just a martial art, but a compass for existence, pointing us toward becoming not only stronger warriors, but better human beings.

After sixteen years of practice, I remain profoundly aware of how little I truly know. Paradoxically, the deeper I go, the more I realize how vast the path is before me. Far from discouraging, this realization fills me with wonder. I feel like a beginner every time I bow into the dojang (training hall), as though I am just scratching the surface of an immense legacy that stretches across centuries, generations, and lives. Each encounter, every lesson, each mistake, and even each frustration becomes an opportunity for growth. Inside the dojang, I learn about discipline and technique. Outside, I learn about patience, resilience, humility, and—above all—love.

By

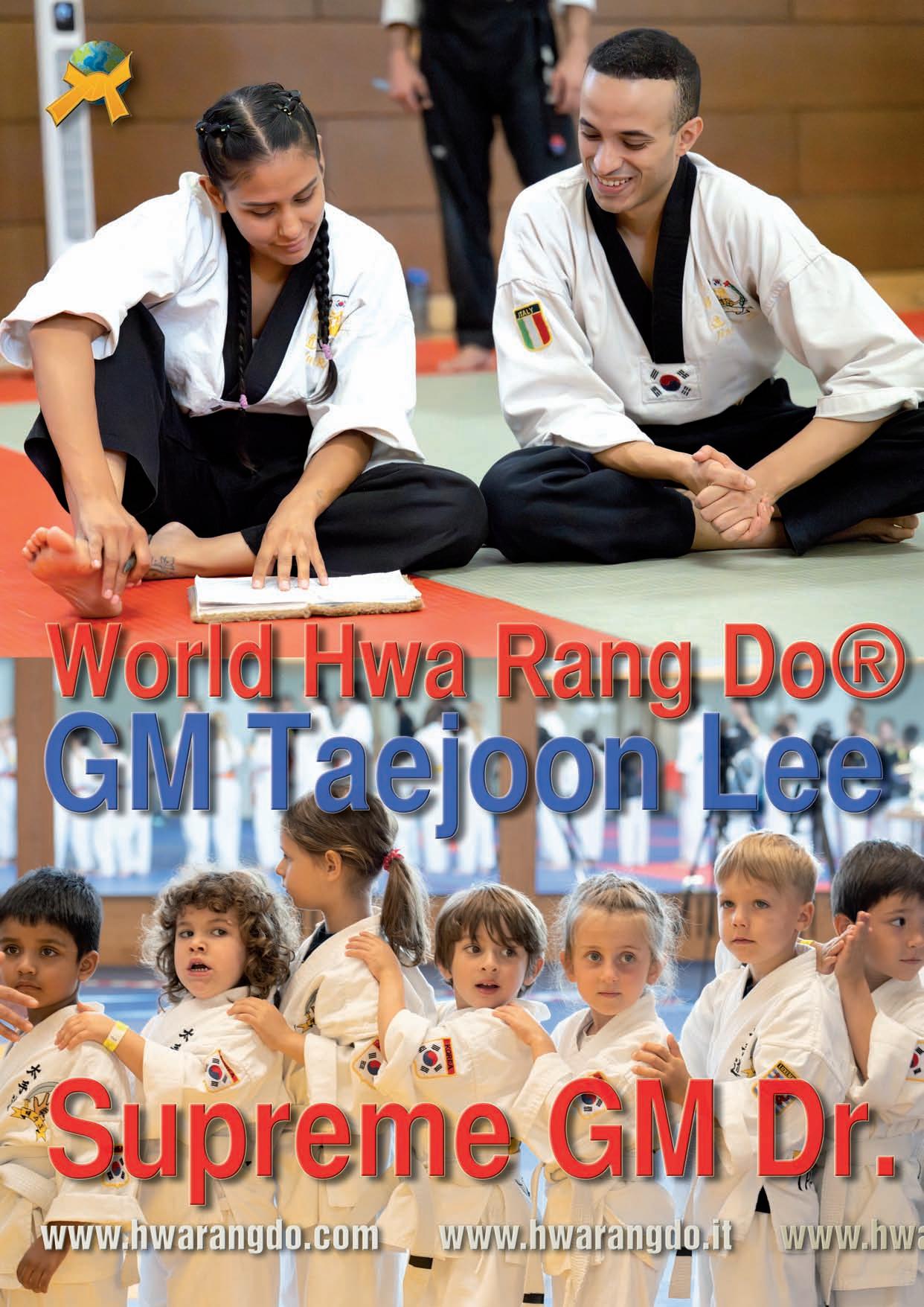

This truth crystallizes each year at the Hwa Rang Do World Championships and Seminars, the most meaningful opportunity to train directly with the Founder, Do Joo Nim Supreme Grandmaster Dr. Jo Bang Lee, his son and heir, Grandmaster Taejoon Lee, and Masters from around the world. These gatherings are not just tournaments or technical intensives; they are living experiences of the Art’s soul during a ten-day full immersive gathering. Over the years, and thanks to the constant support of my Instructor and Master, I have had the privilege of attending several such events. Each has left an indelible mark on me. The 2025 edition, held in Luxembourg under the guidance of Grandmaster Taejoon Lee, was no exception. In fact, it was truly transformative.

First, I want to express heartfelt gratitude to Grandmaster Lee and the entire Luxembourg team. Their organizational efforts were extraordinary. While the basic structure of the event remains consistent from year to year, each edition somehow feels fresh, renewed, elevated. It made me pause and reflect: why not simply repeat what has already worked so well? Why invest so much energy into improving something that already seems flawless?

The answer lies at the very heart of Hwa Rang Do. Excellence is not a destination; it is a constant pursuit. In our community, this striving for more, this refusal to settle, is so embedded in our culture that we often take it for granted. But this year, I tried to see it with new eyes, as if I were an outsider. Then I recognized the invisible thread woven into everything: the discipline, the care, the attention to detail, the sacrifices willingly made. That thread is not just tradition—it is love expressed through excellence.

The championships are demanding in ways that are difficult to fully capture. For students, the focus is singular: to give their absolute best in competition, whether performing forms or facing opponents in combat. But for Instructors and Assistant Instructors, the burden is far greater and layered with responsibility. They referee, manage, organize, and officiate—ensuring fairness and order for everyone else— while simultaneously maintaining their own readiness to step onto the mat and perform at the highest level. It is a relentless cycle of shifting focus: one moment demanding impartial judgment with razor-sharp clarity, the next moment requiring full intensity of body and spirit in competition.

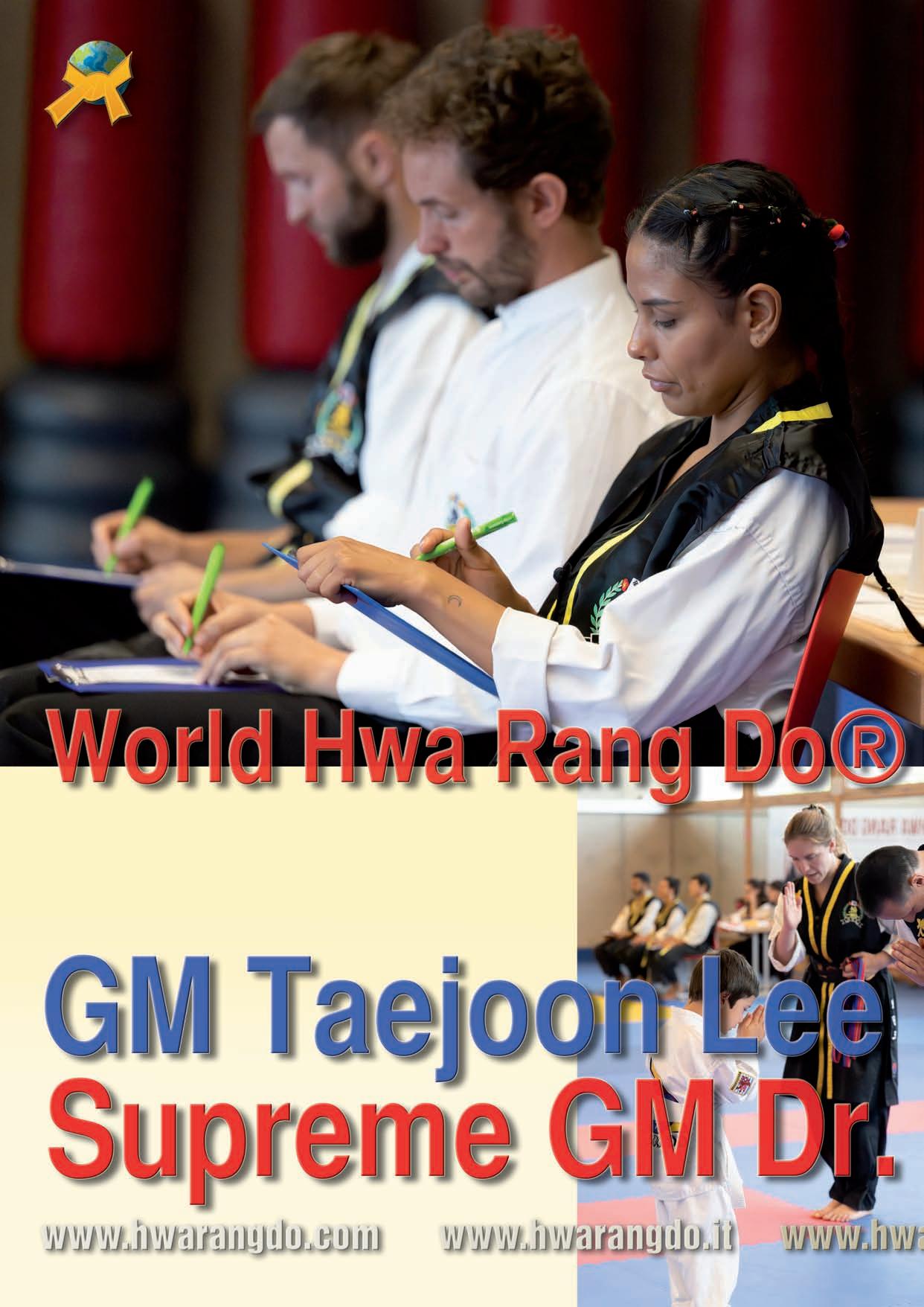

And yet, this is only the beginning. Once the championships conclude, five more days of intensive seminars begin—covering an astonishing breadth of subjects across our vast curriculum. From morning until night, we immerse ourselves in everything from core techniques to advanced applications, from sportive drills to the subtle, refined nuances of energy and flow. The physical intensity is matched by the mental demand, as each lesson requires openness, adaptability, and deep concentration.

The schedule does not relent when the training day ends. After hours of seminars, we gather again for group dinners and late-night meetings, sharing insights, laughter, and reflections. The bonds forged in these moments are as important as the lessons learned on the mat. By the time we retire to rest, it is already late into the night. Sleep becomes a rare luxury. And yet, at the first light of dawn, we rise again—not sluggishly, not reluctantly, but with determination. Each morning begins with the internal practice of Hwa Rang Do: nae gong—breathing exercises, internal energy development, and meditation to align body and spirit before the day’s grueling physical training begins anew.

This rhythm, exhausting as it may sound, is embraced by all. No one attends expecting comfort or leisure. We did not come to sleep; we came to learn, to grow, and to cultivate deeper bonds with our Hwa Rang Do family. The fatigue becomes secondary, almost irrelevant, overshadowed by the shared sense of purpose and the profound joy of belonging to something greater than ourselves.

And yet, despite the exhaustion, I have never witnessed bitterness or resentment. Competitors who just moments before had clashed with full intensity—sometimes exchanging blows with every ounce of strength they could summon—embrace afterward as brothers and sisters. Volunteers give up rest, sometimes sacrificing their own preparation, in order to serve others with a smile. Where else in the world, I wondered, do we encounter such a spirit?

The answer began to reveal itself more clearly during the seminars.

One Instructor, who had earned the coveted Black Sash only the year before at our Annual Event in Tuscany, Italy, had traveled all the way from Los Angeles to Luxembourg. His journey was long, his body heavy with jet lag and fatigue, but his dedication was unwavering. From the very start, he gave himself fully: refereeing tirelessly, competing with honor, and supporting his Teacher—our Founder, Supreme Grandmaster Dr. Joo Bang Lee—in every way possible.

Late one evening, after ensuring that Do Joo Nim and his family were safely transported back to their hotel, this Instructor suffered a minor car accident on his way back, brought on by exhaustion and lack of rest. Thankfully, no one was injured. The next morning, after dealing with the stress and bureaucracy of insurance paperwork, he still appeared at the seminar, though a little late. For most people, this delay would have seemed forgivable, even commendable, given the circumstances. But in Hwa Rang Do, discipline is absolute, and excuses—however understandable—are never allowed to weaken its foundation.

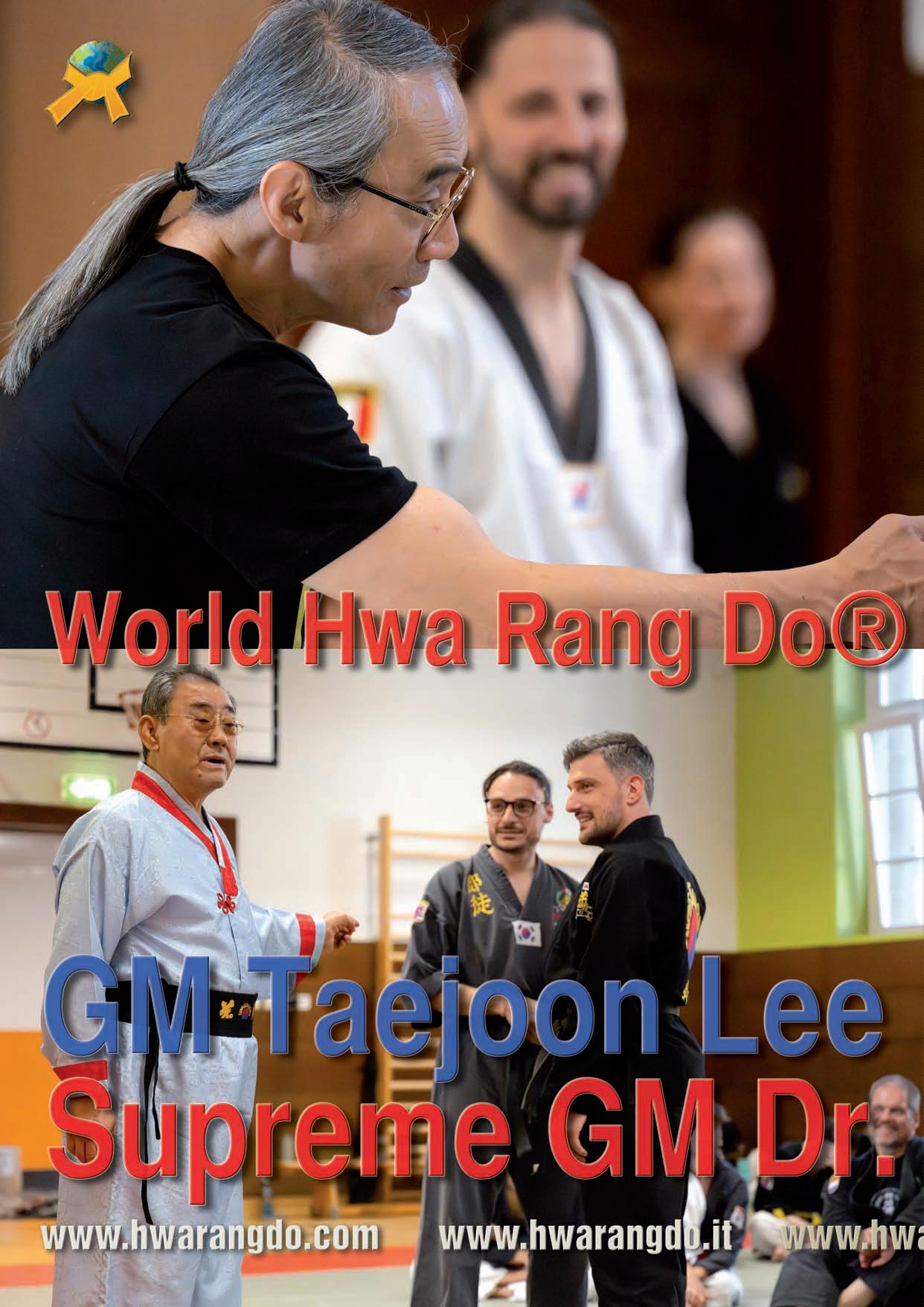

In front of everyone, Grandmaster Lee reprimanded him firmly and without hesitation, ordering him to perform one hundred knuckle push-ups on the hard floor. The hall fell into silence as he obeyed. What struck me most was not the firmness of the correction, but the Instructor’s response. He did not argue. He did not explain or complain. He bowed his head, dropped to the floor, and endured every push-up with dignity and humility. When it was over, he bowed again—grateful for the correction.

At that moment, something profound crystallized for me. In Hwa Rang Do, discipline is not punishment. It is love. It is a gift—a clear and undeniable reminder of responsibility, accountability, and commitment to the path we have chosen. When Grandmaster says, “Discipline is what I’m offering you, because I love you and I care for you to succeed,” these words are not abstract philosophy. They are lived truth. We do not feel diminished by discipline; we feel valued, protected, and honored.

True love is not permissive. Loving someone does not mean accepting or approving of everything they do. On the contrary, it often means taking the harder path: pointing out mistakes, delivering firm corrections, and insisting on what is right—even when it is uncomfortable or inconvenient to do so. To discipline is to care enough to guide someone back onto the path that will allow them to flourish, to become their best self, and to reach their full potential. This is the essence of a Master’s love: not indulgence, but responsibility.

As Grandmaster Lee often reminds us: “Discipline is out of love, and punishment is out of hatred. We discipline our family; we punish criminals.” These words resound deeply. Discipline within Hwa Rang Do is never meant to break us down or humiliate us; it is meant to build us up, to protect us from the complacency and excuses that might otherwise derail our growth. It is an act of love, born of the desire to see us rise higher than we ever thought possible.

Perhaps the most powerful moment of the entire week did not arrive in the midst of competition, nor during the intensity of the seminars, but around a simple dinner table. After an exhausting day—one that would have justified rest or solitude—Grandmaster Lee instead insisted on a communal meal at the Scout House where many of us were staying. He could have chosen comfort, yet he chose connection. As we gathered, he explained softly but firmly: “This is what a parent does. If the children cannot come home for dinner, the parent must go visit them.”

That single sentence pierced my heart. It carried again the weight of lived truth, the kind of wisdom you do not simply hear but feel. As a father of two, I know intimately the heavy burden of parental love: the sleepless nights, the constant vigilance, the endless cycle of worry and sacrifice. I know the pain of discipline—the moments when correcting your child wounds you more deeply than it wounds them, yet you persist because you love them enough to guide them. Much of this labor remains unseen, unacknowledged, even resisted. And yet, we do it. Not because it is easy or gratifying, but because love leaves us no other choice.

So why would a Master—already carrying the weight of an entire legacy, already advanced in years—choose to bear such a burden for his students? Why would Do Joo Nim, year after year, continue to cross continents, to spare no effort, to give all of himself without rest or retreat? What could possibly sustain such relentless devotion?

The answer came to me unexpectedly, not in a grand gesture but in an unremarkable moment one morning. My Instructor was in the kitchen preparing breakfast for everyone. He had brought fresh ingredients all the way from Italy, even carrying his own cooking tools across borders, and he prepared each dish with the same care and focus he brings to teaching on the mat. Watching him, I suggested something simpler—a quick meal, or perhaps ordering in—to save him the effort. He smiled gently and replied: “For me, cooking is a way to love.”

In that instant, the pieces fell into place. The quiet devotion, the tireless giving, the discipline that corrects rather than condemns—it all flows from the same source. The answer, as simple as it is profound, is Love.

Love is the hidden thread that binds together every sacrifice, every late-night meeting, every stern correction, every gesture of service. Love is why Masters devote themselves endlessly to their students, even when recognition is absent and the cost is high. Love is why Do Joo Nim continues, undeterred by age, to travel the world— because like a parent, he cannot stop loving his children. And it is this Love that transforms Hwa Rang Do from a martial art into a living family, and from a discipline of combat into a way of life.

Love lies at the very heart of Hwa Rang Do. It is love that compels the Masters to give endlessly of themselves, even when they receive little or nothing in return. It is love that transforms loyalty from mere blind obedience into a conscious, deliberate act of commitment. Love is the root, the foundation from which loyalty grows, and loyalty itself is the visible fruit of love in action. Without love, loyalty becomes servitude; with love, it becomes devotion.

Love grants us the strength to believe in someone even after repeated failure. It softens the heart, making room for forgiveness, teaching us to persevere, and enabling us to continue giving without any expectation of reward.

Compassion, forgiveness, and mercy are not signs of weakness; they are, in truth, the most courageous and noble expressions of love.

We are only able to love because God first loved us. His love is boundless, unconditional, and freely given, not because we deserve it, but because it is His nature. As recipients of that immeasurable grace, we are called to reflect it in our own lives. Just as God loves us without limit, so too must we learn to love others—with patience, with sacrifice, and with unshakable steadfastness.

This kind of love cannot be demanded, nor can it be claimed by right. It is a gift—freely given, often undeserved, always precious. I have received this love in abundance throughout my years of practice. And while I know I have not yet earned it fully, I remain deeply grateful for it. That gratitude is what fuels my training, what drives me to strive harder each day: not merely to receive love, but to become strong, disciplined, and humble enough to give it in return. To become, in essence, a vessel through which the same love that was poured into me can flow outward to others.

In a world where strength is too often confused with arrogance, and discipline mistaken for cold rigidity, Hwa Rang Do illuminates a different path. It teaches us that true strength is inseparable from compassion, that real discipline is not harshness but care, and that the greatest forces a warrior—or indeed any human being—can embody are love and loyalty. To fight without love is brutality; to discipline without love is tyranny. But when strength, discipline, and loyalty are rooted in love, they become transformative. This is the true essence and value of Hwa Rang Do.

This path is not easy. It demands everything: time, energy, humility, patience, and sacrifice. It strips away illusions, forces us to confront our weaknesses, and challenges us relentlessly. But in doing so, it reshapes us. It forges not only better martial artists, but better fathers, mothers, sons, daughters, leaders, and friends. It transforms us into better human beings.

For this, my heart overflows with gratitude—to Do Joo Nim, to Grandmaster Taejoon Lee, to my Master, to my Instructor, and to the worldwide Hwa Rang Do family. They have given me the priceless gift of love expressed through discipline, loyalty, and sacrifice. And in their example, I find not only guidance, but also the calling to one day give the same.

Hwarang Forever and May God Bless Us Always,

The six elements and martial arts

“Dress me slowly, for I am in a hurry!”

Spanish wisdom

“The best closed door is one that can be left open.”

Chinese wisdom

Extremes have always been outlined and referred to as the essence of opposites in comparison, in fair position—whether at levels of convergence or divergence. An imaginary reality for those who observe it and seek balance as a middle ground; an exaggerated movement that requires clarity and lucidity between what is seen, felt, interpreted, and understood.

Immanuel Kant was right when he said: “In the realm of ends, everything has either a price or a dignity.” A small “sip” from the cup of wisdom that teaches us that from the day we come into this world, when we leave our mothers' wombs, good and evil, positive and negative, beauty and ugliness, etc., are united in the unstoppable game of adjustments. It is certain that no one leaves this life alive, and the in-between, what happens to us in the meantime, is still a mystery. After 31 years, I meet again a very dear person who was part of a transformative past, of struggle, suffering, encounters, misunderstandings... Writing this article in her company shows me that if we know the point of arrival, we also know the starting point of our personal evolution – so individual and non-transferable!