THE PHOTO ALBUMS OF

1857 – 1869

1857 – 1869

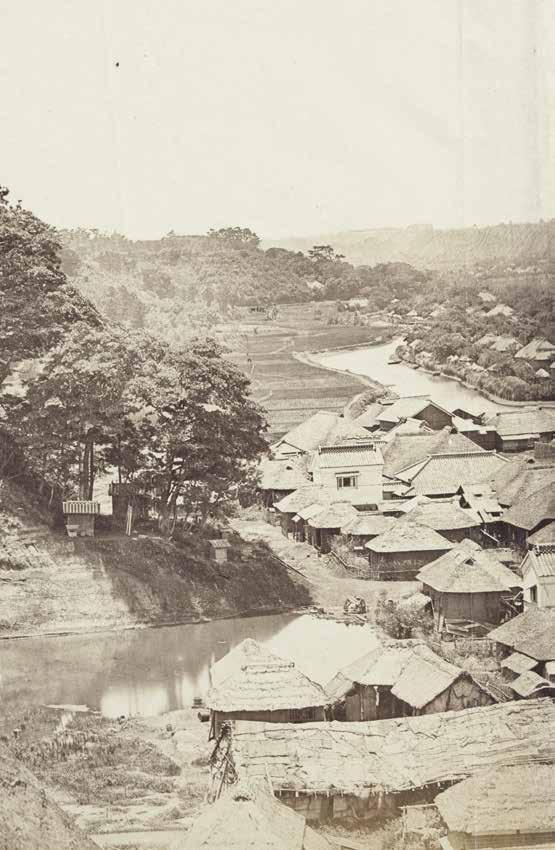

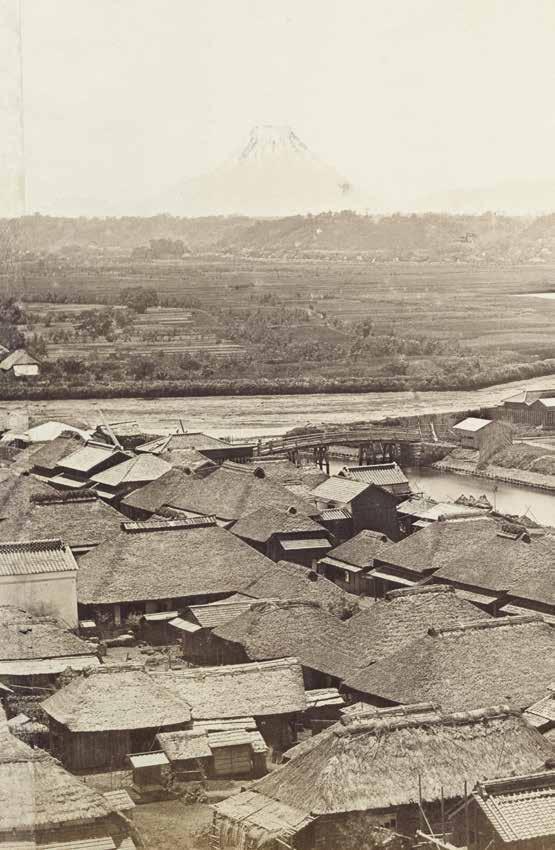

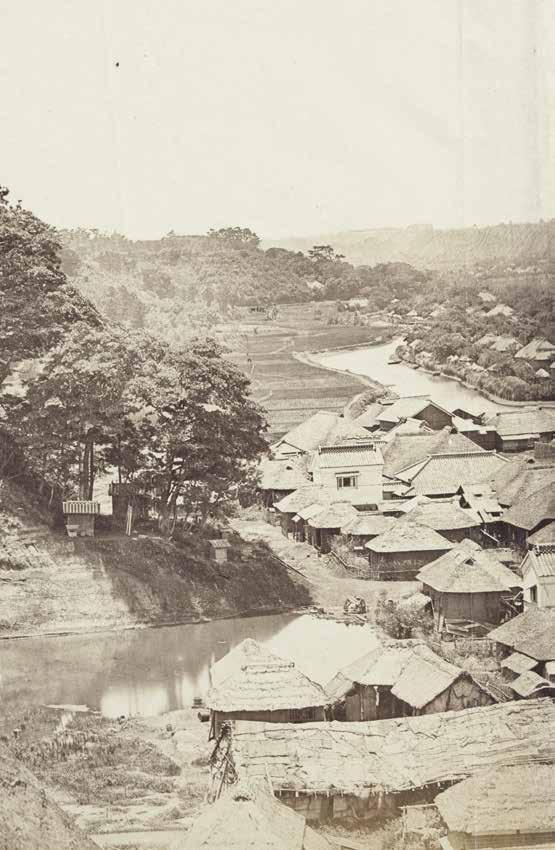

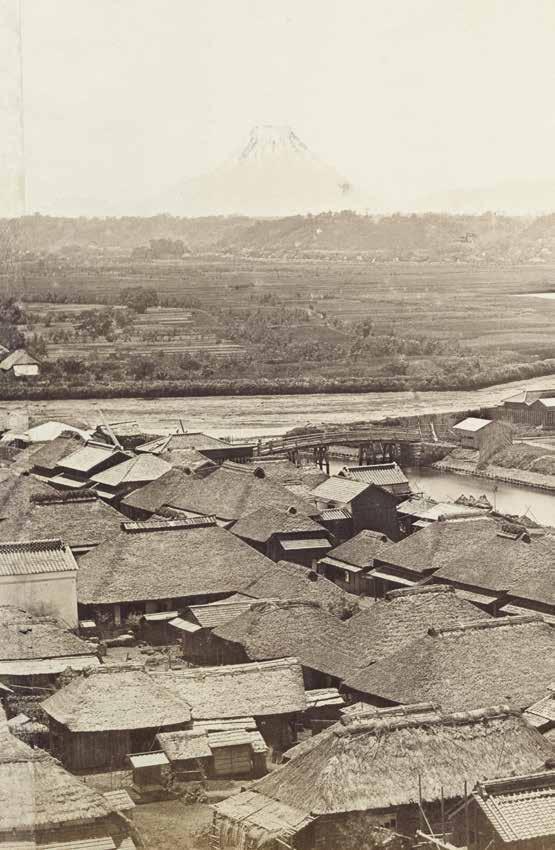

Felice Beato (1832-1909), Detail from a photographic panorama of Yokohama, 1863. Albumen print S.3628(03)008

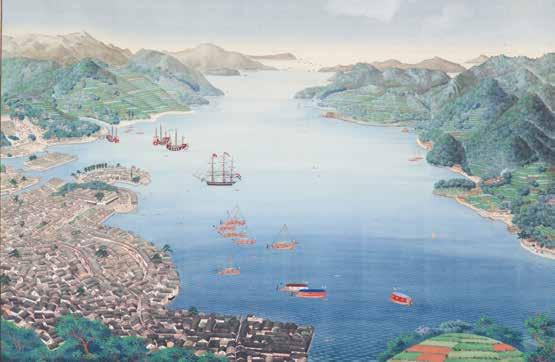

When 23-year-old Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek sailed into Nagasaki he was left ‘quite speechless with wonder’ as he saw the bay, surrounded by densely wooded hills whose green canopy reflected in the water.1 After a stormy voyage, the Anna Digna dropped anchor off the island at the entrance to the bay, known by the Dutch as Papenberg, at seven in the morning of 24 July 1857.2 As soon as land had been sighted, they had raised the Dutch tricolour and their signal flag. A six-gun salute had then sounded from the coastal battery and the chain was lowered to allow the Japanese boats to guide the vessel to its anchorage. There, on the fan-shaped island of Dejima, Dirk de Graeff set foot on Japanese soil, the country he was to call home for almost twelve years.

In the light of the rising sun | The photo albums of Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek

Kawahara Keiga (1786–1860?)

Drawing of Nagasaki Bay showing Dejima island, 18291860.

A.2714

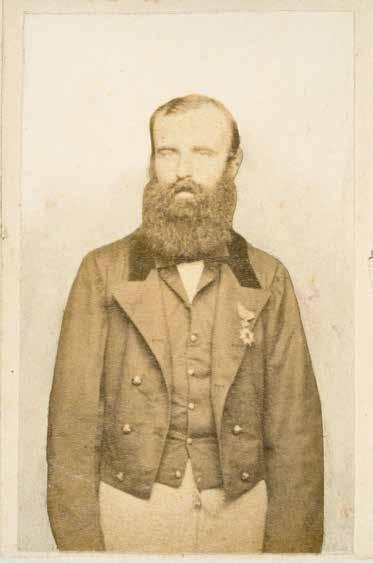

Felice Beato (1832-1909), De Graeff van Polsbroek, Minister of Holland

Portrait of Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek, Dutch Consul General, 1863. Albumen print

S.3628(03)003

Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek (Amsterdam, 28 August 1833 – The Hague, 27 June 1916), scion of an Amsterdam regent family, left Batavia three weeks earlier.3 He lived and worked there for almost four years. First employed at his cousin’s notarial office, he later served as an administrative official at the Directorate of Cultures.4 When he arrived in Japan, he took up a new post. He was appointed assistant 2nd class to Jan Hendrik Donker Curtius (1813-1879), commissioner of the Dutch trading post on Dejima. De Graeff was to assist the latter in drawing up the so-called Additional Articles to the treaty concluded with Japanese authorities in 1856. He translated these into French and compiled summaries of the secret correspondence of recent years. A highlight of these first years was undoubtedly the five-month journey of the Dutch delegation to Edo, today’s Tokyo, for an audience with the shogun – Japan’s supreme military leader and de facto ruler – on which he accompanied Donker Curtius in 1858. The following year, De Graeff moved from Dejima to Kanagawa on the other side of Yokohama Bay, to take up a post as partner in the trading firm of Textor & Co.5

When De Graeff moved to Kanagawa, Donker Curtius promoted him to acting vice-consul. This designation was the start of a meteoric diplomatic career. In March 1861, De Graeff became consul in Yokohama, which had grown from a small fishing village to become the political and commercial hub of Japan’s emerging foreign community. Two years later, he was a political agent and consul general. De Graeff’s career reached new heights on 8 July 1868, when he was installed as minister resident, akin to a modern-day ambassador. In 1859, De Graeff married Koyama Ochō (her date of birth and death are not recorded), daughter of a Japanese tea trader. They had a son, Pieter (1861-1909), who sailed to the Netherlands with his father in February 1869, never to see his mother again. De Graeff’s departure had been intended as a well-earned furlough, but domestic political intrigue would later prevent his return to Japan. On 12 January 1870, he was honourably discharged from the civil service at his own request.6

The picture of De Graeff that emerges from written sources is one of a man with a strong sense of justice and a profound love of Japan. His many excellent contacts – both Japanese and other foreign representatives – and his tact ensured that De Graeff was often asked for advice and assistance in negotiations and remained well-in-

formed through sources outside official channels.7 From this we may conclude that he probably had a good working knowledge of the Japanese language. In disputes, he never rushed to side with his compatriots or other foreigners, so that colleagues tended to see him as a friend of the Japanese.8 De Graeff frowned on the Dutch who behaved ‘crudely and improperly’ – like many newcomers to Yokohama – and did not hesitate to impose punishments.9 A contemporary notes that despite his youth, De Graeff was resolute and not easily swayed by others. He ‘made good ground’ as a political agent and ‘rode his luck well’ in Japan. Dame Fortune clearly favoured him.10

De Graeff left behind a journal and three photo albums. In its current form, the journal is a transcript — that is, a handwritten copy of original diary fragments and notes — and is highly fragmentary in nature. Up until 1862, De Graeff compiled his journal retrospectively from the many notes and documents in his possession. Only the five-month journey to the court in Edo in 1858 is described in a true day-by-day account. On 1 January 1863, he began a new diary, but it has been lost. A relative deemed it unremarkable and is said to have burned it along with other papers. Only the loose notes De Graeff made in connection with that diary have survived, forming the final, brief section of the journal.11 Yet although it is incomplete, Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek’s record is a valuable document. It highlights the experiences of a diplomat immersed in the momentous changes that gripped Japanese society shortly before and after the country was compelled to open its first three ports to international trade.12

Equally remarkable are the three photo albums he left behind. Photography arrived just in time to record this extraordinarily turbulent period in Japanese history. The opening of the ports effectively brought Japan into the frame of photography. While the medium may have by then existed for twenty years, in Japan, photography was still limited to small scale experiments. The photographs in Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek’s albums, which were donated to the Maritime Museum together with his journal in 1963, are among the earliest of Japan in existence.13 They represent the work of the country’s first commercial photographers who focused principally on topographical, portrait and genre photos (scenes of everyday life), and the work of amateur photographers who tended to take pictures of their own surroundings and social circles. De Graeff did not take photographs himself, or at least there is nothing to suggest that he did. He bought or received prints made by friends and professional photographers. He collected these in three albums, each different in size, binding, cover and content.

The first album (following the order established by the museum) contains the earliest photographs and is the most diverse in terms of maker, location, subject and date.14 It also contains paintings on silk and paper whose authors are now no longer known. De Graeff probably compiled this album after returning to the Netherlands, combining various prints he collected while in Japan and occasionally had sent to the Netherlands. The second album was compiled in Japan in late 1863 by photographer Felice Beato (1832-1909). All the pictures were taken by Beato in the latter half of that year. The third album consists primarily of work once again by Beato. It includes early hand-coloured souvenir prints dating mostly from the years 1866 and 1867. Together, the albums offer a perspective on a volatile period in Japanese history, reflecting the growth of photography in that country, and showing the personalities and events that featured in the young diplomat’s career.

While the albums were extensively researched in the 1980s, and have excited interest around the world, the photographs they contain have tended to be regarded as little more than an accompaniment to the journal. They were used mainly as illustrations to descriptions of historical events in Japan or as examples of the work of photographers. The visual information, the matter depicted in the photographs, has been thoroughly researched, as have the methods used in the printing process. In recent years, however, the study of early photography in Japan has shifted considerably and the contexts in which photographs were made, distributed and used have increasingly been subjected to critical examination.15 This changing focus has brought new insights and thrown a different light on Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek’s involvement in the early development of photography in Japan: the Dutch diplomat helped, however unwittingly, to shape the nineteenth-century view of a country shrouded in mystery, which was just beginning to open up to the West.

Maker unknown, in the tradition of Kawahara Keiga (1786–1860?), Domestique de boutique Painting of a shop assistant, c. 1865.

S.3628(02)111

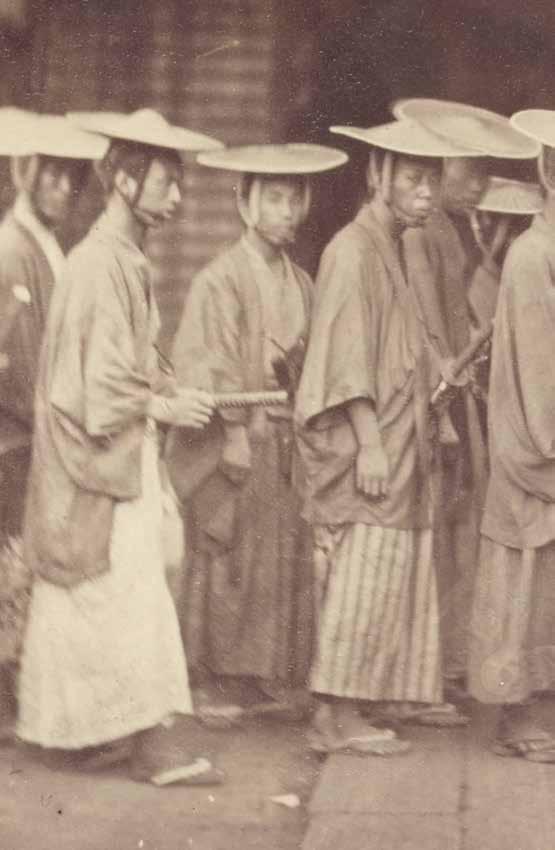

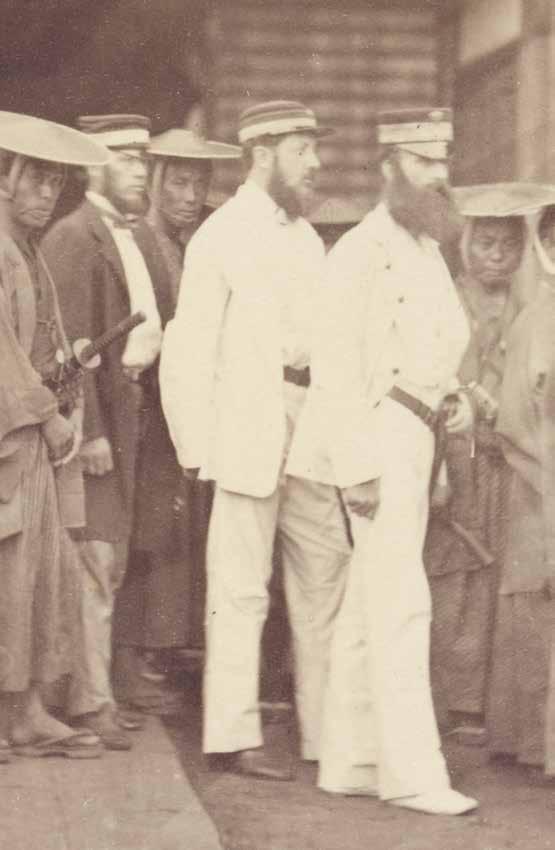

Felice Beato (1832-1909), Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek (white suit, right) and Secretary J.P. Metman (white suit, left) with a Japanese escort at Chō’ōji temple in Edo; (Detail, full picture on p. 75)

It must have been a surreal and alarming sight when, on 8 July 1853, a squadron of four heavily armed American naval vessels appeared in the bay of Edo under a cloud of thick black smoke.1 Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858) arrived bearing a letter to the Japanese ‘emperor’2 from America’s president, Millard Fillmore (1800-1874)3, instructing him to employ gunboat diplomacy to compel Japan to abandon its isolationist policy, which had been in place since 1639. In his letter, Fillmore insisted that Japan should engage in diplomatic and commercial relations with the United States (US). The country’s strategic location and rumours of substantial coal deposits gave the Americans good reason to establish relations. They wanted to have a string of coal stations for their steamships en route to China, which had been forced by the British to open four additional ports to international trade after the First Opium War (1839-1842).4 The Americans also wanted safe harbours and supply stations for their whalers in the stormy northern Pacific Ocean, and proper treatment of shipwrecked sailors.

For the Japanese, Perry’s ‘black ships’ were the biggest foreign threat the country had ever faced. All attempts to compel the fleet to leave failed, as Perry further increased pressures by conducting intimidating expeditions along the coast. Thunder of blank cannon salvos echoed far and wide. In a letter, Perry threatened to crush the Japanese if they would oppose him. Following fevered consultations, the Bakufu – the government of shogun Tokugawa Ieyoshi (1793-1853), by then seriously ill – agreed to receive Fillmore’s letter. On 17 July, Perry withdrew from the bay, promising to return for Japan’s answer. Seven months later, he reappeared with a squadron of eight ships, raising the pressure even further. After weeks of negotiations, in which the exchange of diplomatic gifts played a prominent role, the Tokugawa shogunate signed the Treaty of Kanagawa.5 The treaty stipulated that the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate would be opened for the provisioning of American ships. It also included a most-favoured nation clause: any commercial concessions that Japan made to other countries would also apply to the US.6 This paved the way for the first trade agreement between the two nations, signed in 1858.7

20 In the light of the rising sun | The photo albums of Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek

Hibata Ōsuke (1813-1870), painter

Takagawa Bunsen (1818-1858), painter

Onuma Chinzan (1818-1891), calligrapher

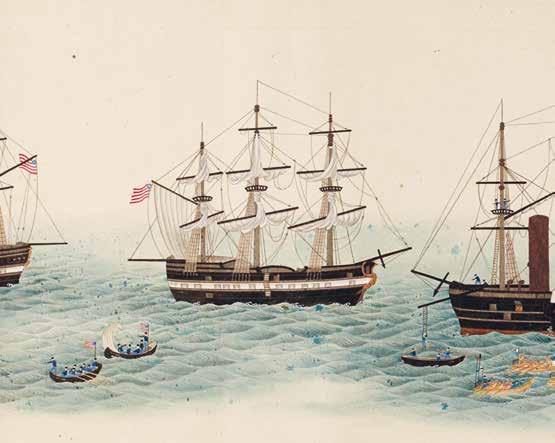

Detail from a painted silk scroll showing the return of the reinforced American squadron to Japan in 1854, 1854-1858. British Museum collection. 2013,3002.1