What is Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness go beyond the absence of disease. They reflect a continuous journey of balance, growth, and fulfillment, where the mind, body, and spirit are interconnected. Together, they shape how we live, how we connect with others, and how we find purpose in everyday life.

A RETURN TO ESSENTIAL MOVEMENT

1. When the world was stone and wind.

Before cities, machines, or routines existed, the first humans lived in a landscape that shaped them as much as they shaped it. Cavemen didn’t “work out”: they lived by moving.

They crouched to enter their caves, climbed trees as part of their day, ran barefoot following tracks, carried stones and wood to survive. Their body was their tool, their communication, their warmth. Movement was instinct, play, necessity. There was no word for “posture,” yet they knew how to use every muscle because their life depended on it. In that world, thinking and moving were the same.

2. When fire brought bodies together.

Over time, the first communities emerged. Movement began to happen collectively: tribal dances, night rituals, seasonal celebrations.

The body no longer chased only food— it expressed, honored, gave thanks. Movements were expansive, shared, synchronized with nature. The rhythm of the heart became a drum. It was the first time humans moved out of emotion, not survival.

3. When cities were born.

With agriculture and more sedentary life, the body changed roles. Long distances were no longer traveled. Walls were raised, houses were built, heavy loads were transported—yet movement began to fragment, to become function.

For the first time, humans started forgetting parts of their natural mobility. Still, dance remained. Celebrations continued to remind us that the body is part of the earth.

4. When industrialization sat us down.

Thousands of years later, with machines, smoke, and clocks, natural movement nearly disappeared. The workday arrived, along with chairs, production lines, nonstop speed. The body became something to “manage.”

And then a completely new concept emerged: exercise. If moving had once been living, now moving was correcting the lack of movement.

5. When gyms were born.

In recent decades, gyms grew like inverted factories: places where people went to lift what they no longer carried, run what they no longer walked, sweat what their day no longer demanded.

Machines appeared, guiding the body in perfect but rigid trajectories. Movement became repetition, quantity, measurement. Functional, but not natural. Strong, but not free.

6. When boutique studios appeared.

Later came boutique studios: Pilates, hot yoga, barre, HIIT, cycling. The experience became aesthetic, musical, personalized. Spaces aimed to motivate, contain, inspire. Yet at the same time, the “more, more, more” culture began to tire the body and the spirit. Many movements turned into performances, not integral practices. People began to wonder: “Is this really moving… or just training?”

7. And now… when we return.

Today, after millennia of history, we are starting to remember something ancient: that movement is not only strength or speed. That it’s not about correcting the body, but listening to it. That before gyms, there were caves. Before routines, instinct. Before exercises, life.

Everything points in the same direction: returning. Returning to a body that feels. To moving as play, as exploration, as presence. To reconciling the human with their environment.

8. Mindful Movement.

The project stands here—as a bridge between what we were and what we need to become. Mindful movement doesn’t seek more weight, more repetitions, more intensity. It seeks more awareness. More listening. More connection. More roots.

It is a kind of evolutionary return: from the gym to the inner forest, from training to ritual, from the goal to the moment. A return to moving as we once did— but with today’s wisdom.

BREATH IN A BREATHLESS CITY

TRACING WHAT EXISTS

THE DISTRICT

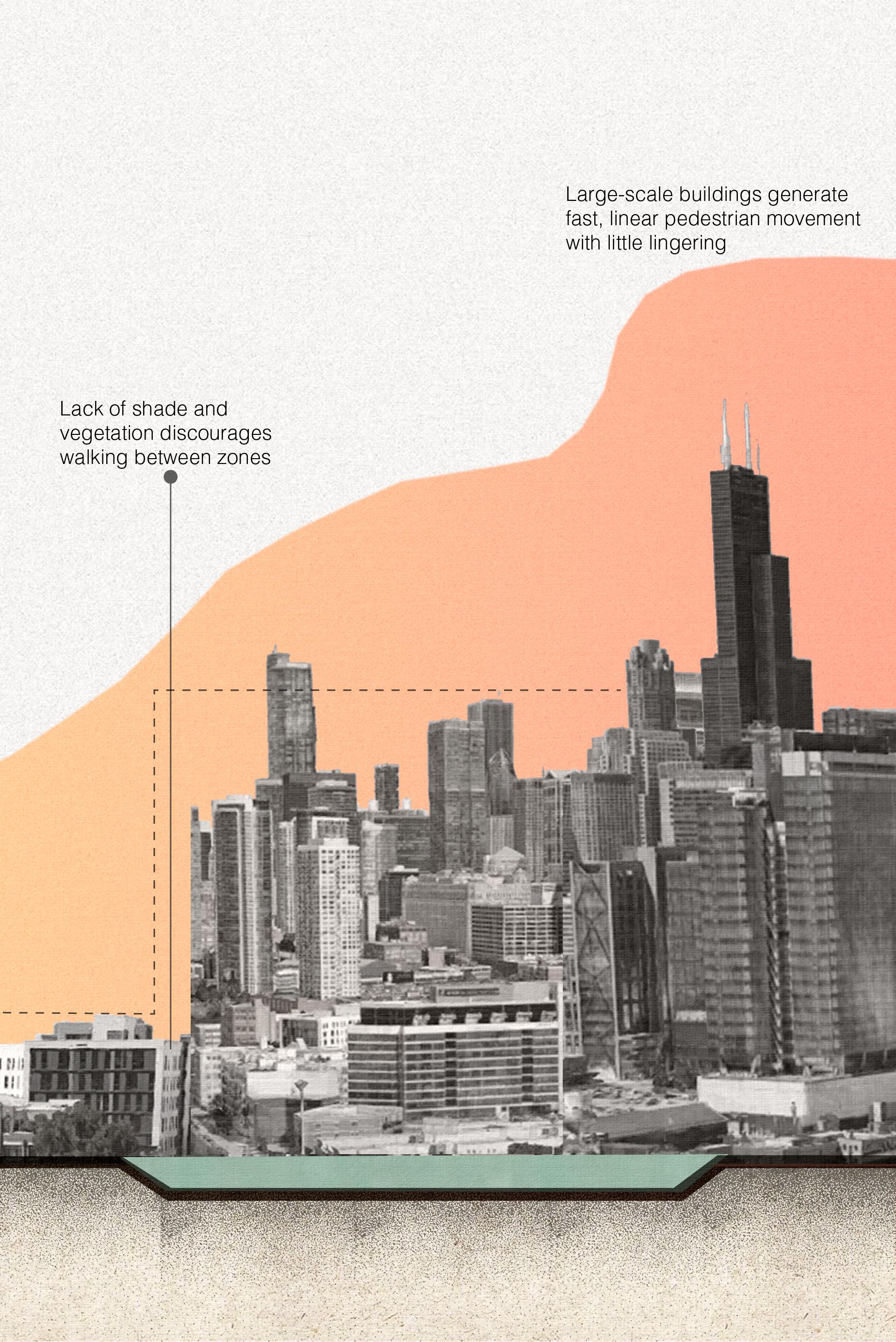

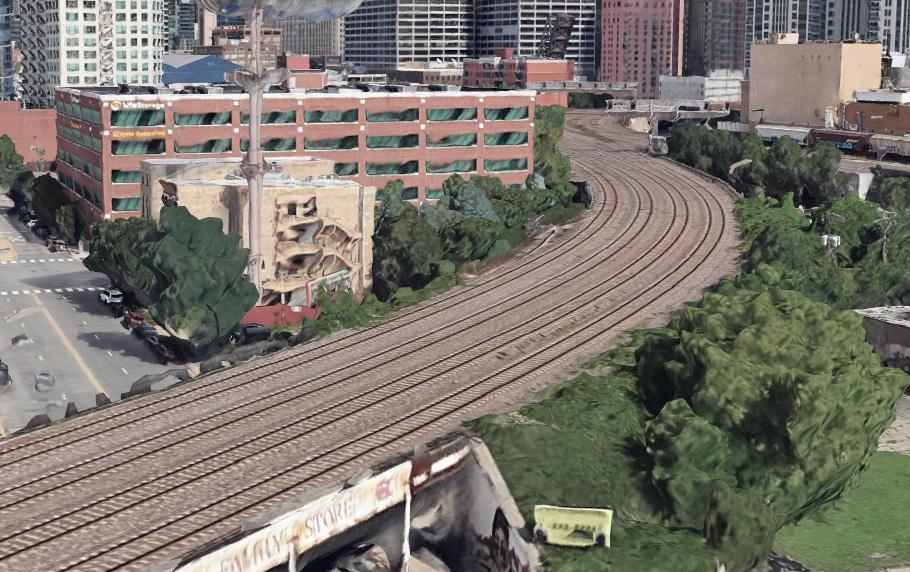

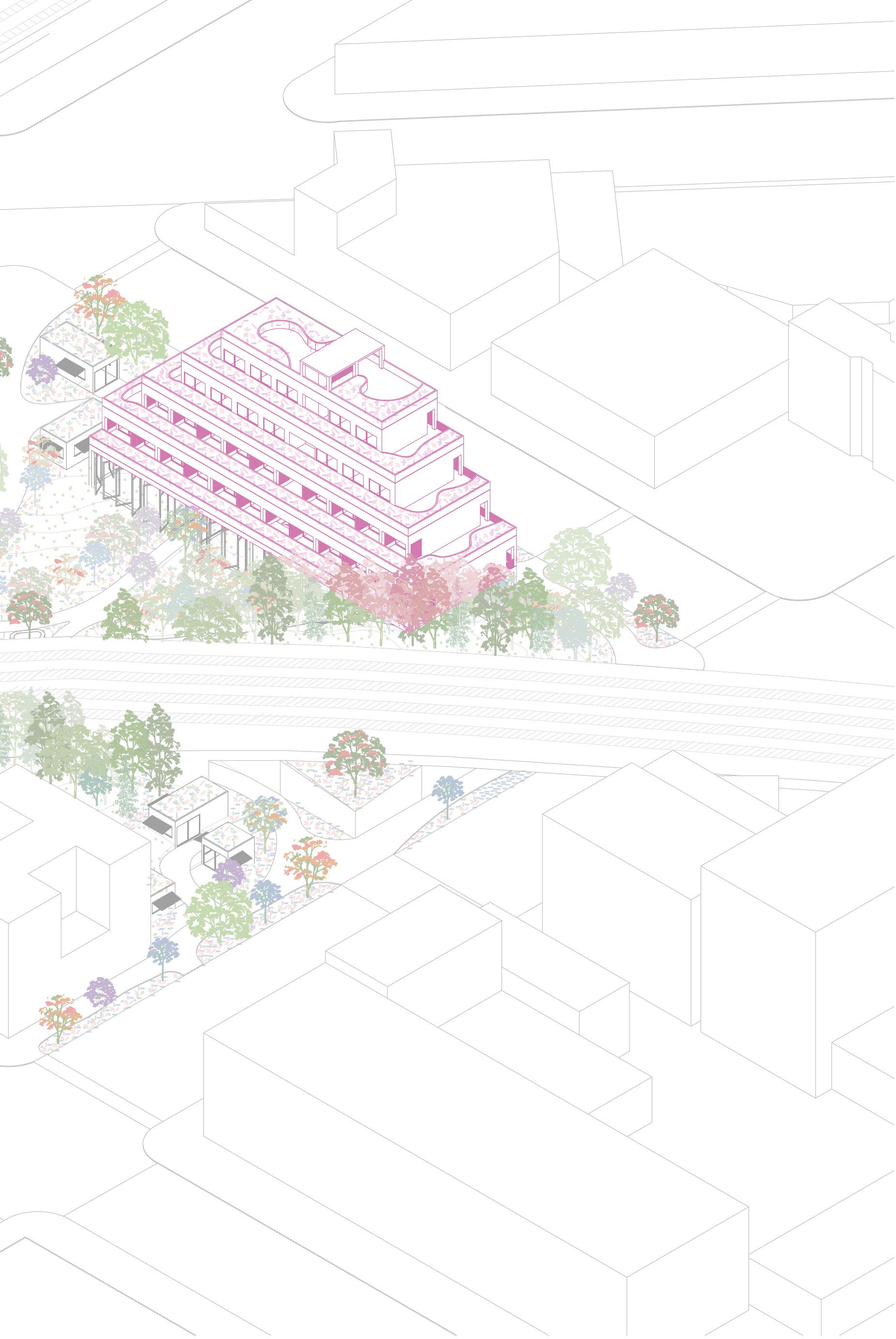

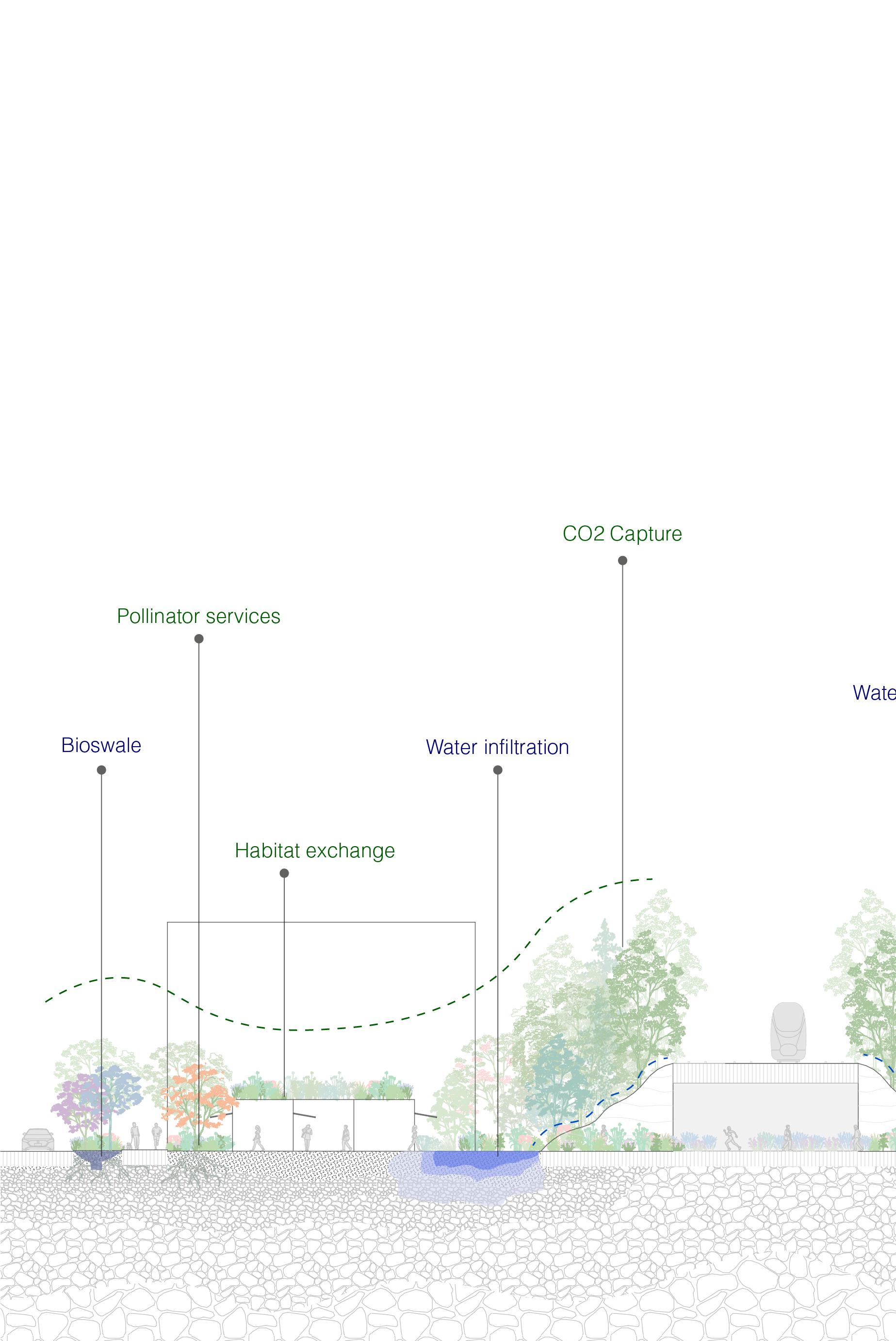

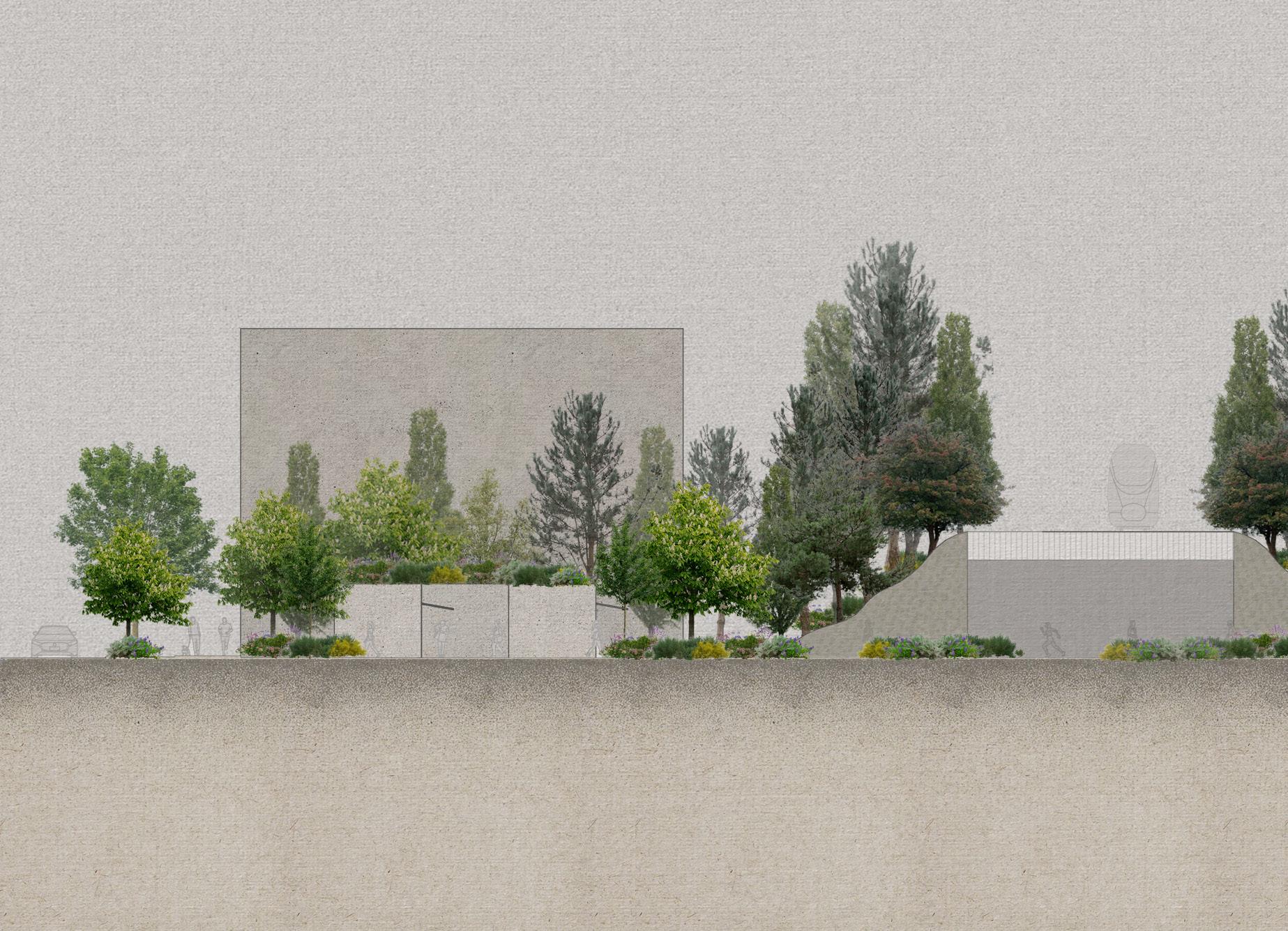

Chicago is a rapidly growing city with limited green spaces, yet Milwaukee Avenue stitches together the ones it does have — Fulton Park, Wicker Park, Eckhart Park, and the 606 Greenway — forming a continuous urban ecological corridor. This network enables residents to move fluidly between parks, encouraging walking, cycling, recreation, and social interaction within an otherwise dense and expanding metropolitan fabric.

At a more focused scale, we concentrate on a city block that outwardly appears green, but whose usability is hindered by steep slopes, physical barriers, and elevated train tracks. Positioned strategically at a corner along

Milwaukee Avenue, this site holds potential to bridge fragmented landscapes and integrate into the larger ecological framework. Our intention is to extend the city’s green corridor, transforming this block into an accessible, welcoming public space that strengthens community life and enhances everyday urban experience.

Currently, pedestrian, vehicle, and train movements in the site operate in distinct but overlapping patterns. The most active flows are concentrated along the primary Avenues (Milwaukee Avenue and Grand Avenue) where daily movement is intensified by the presence of the metro station and several bus stops located at their intersection. This transit convergence generates a strong influx of people throughout the day, making the junction a key mobility node in the neighborhood.

However, as circulation moves away from these main avenues and the transit intersection, pedestrian activity decreases noticeably. Side streets become quieter, with reduced visibility, weaker commercial presence, and fewer reasons for people to continue walking deeper into the block. Vehicular flow follows a similar logic, maintaining high density near the arterial streets and dispersing as it enters smaller residential roads.

In contrast, the train introduces a different kind of movement — constant, linear, and elevated. Its uninterrupted rhythm provides connectivity at a metropolitan scale, yet simultaneously acts as a physical and perceptual barrier at ground level, shaping circulation and influencing how people access or avoid certain areas.

Abandoned

Housing Commerce

Bike lane

Slopes

Circulation

Barriers

Bus stops

Bad smells

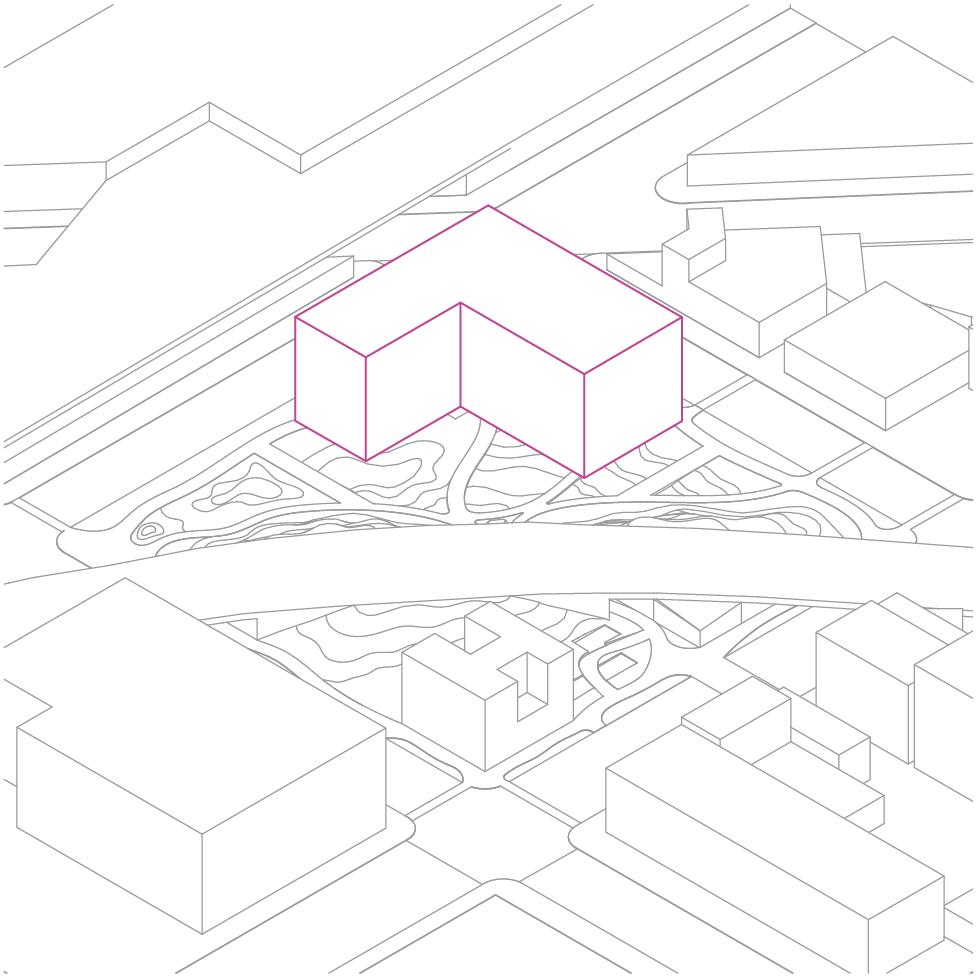

The presence of abandoned buildings creates urban inactivity and weakens community life.

The underbridge suffers from bad odors and poor maintenance, leading to avoidance and underuse.

The block is heavily built with concrete, offering very limited space for vegetation to thrive.

Despite being the greenest block in the district, access is restricted and remains uninhabited.

Physical barriers prevent fluid movement and connectivity within the block.

An elevated train runs through the site, fragmenting space and introducing constant noise.

Sports Bar

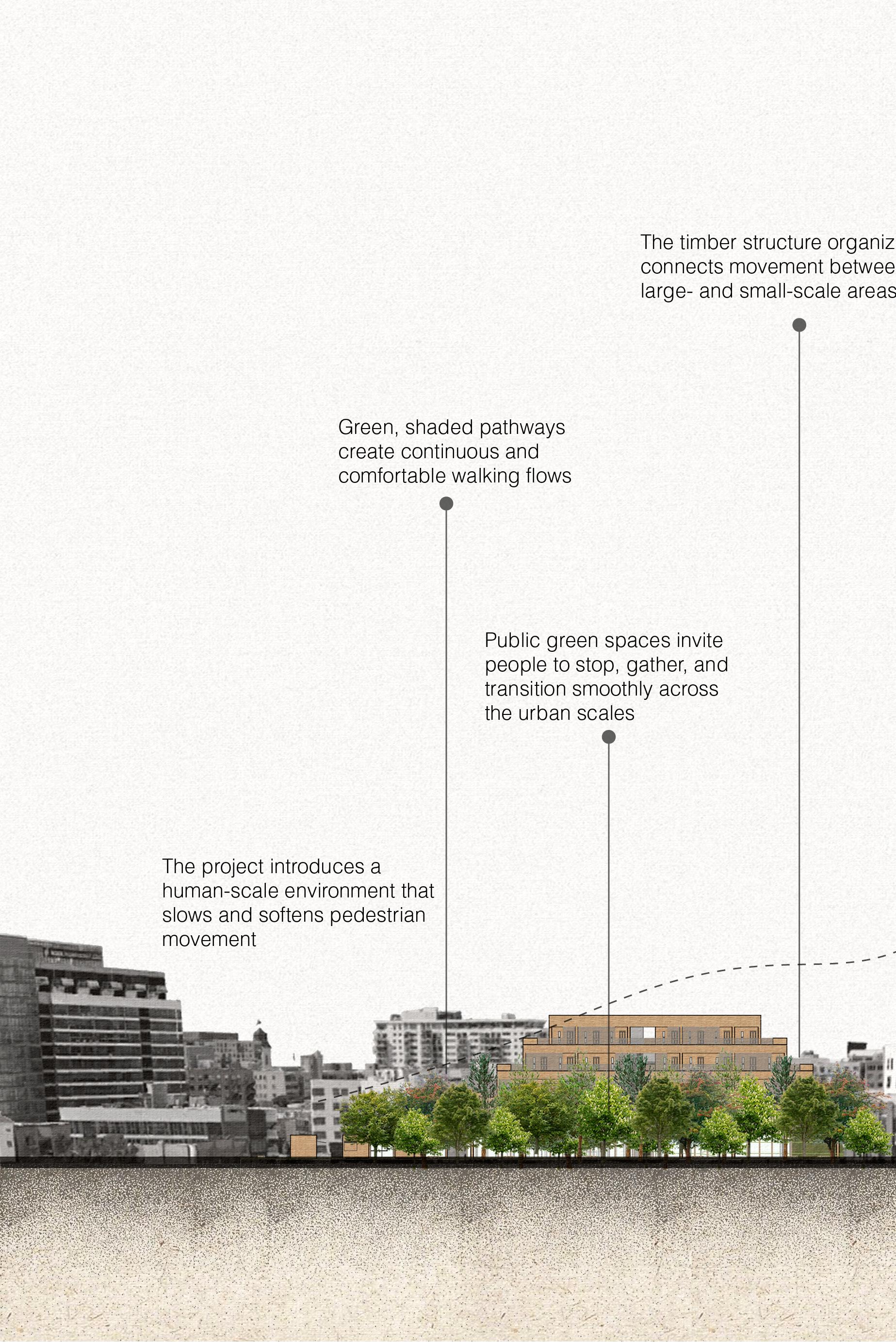

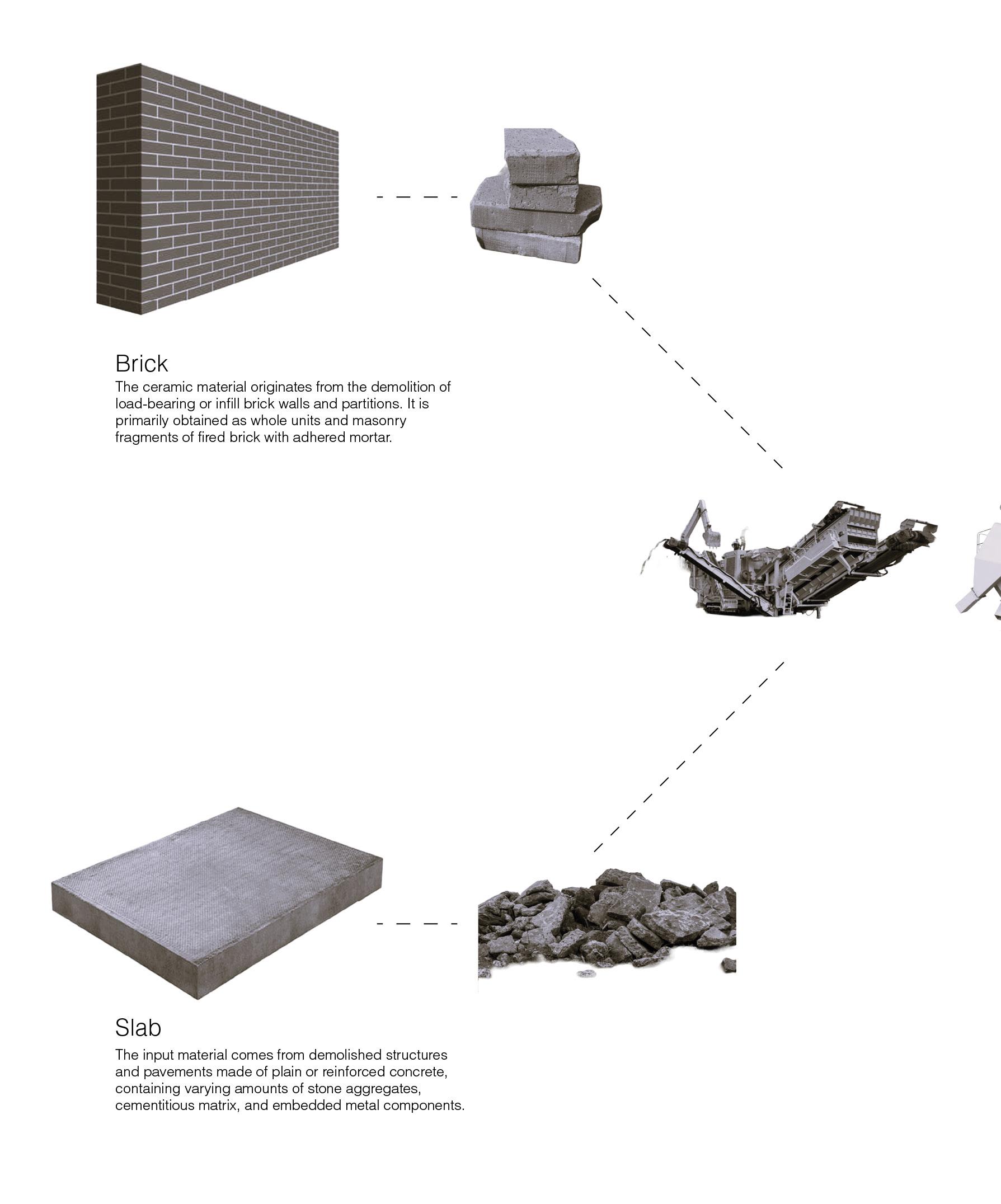

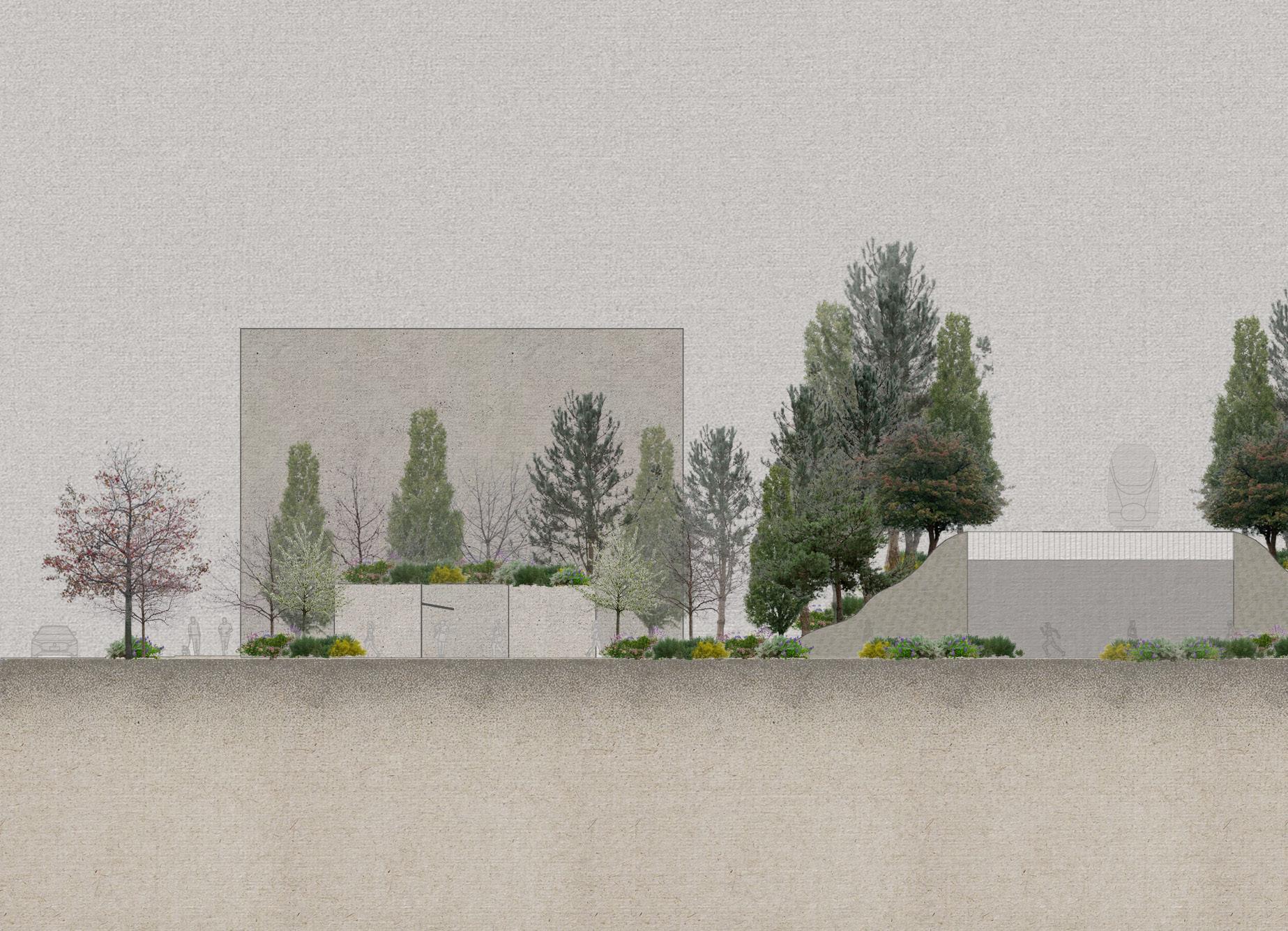

For this intervention, we propose transforming the entire block, including the strategic demolition of selected buildings to unlock circulation and activate its currently inaccessible interior. Removing these structures is not an act of subtraction, but one of release: it opens space for new pedestrian pathways, public programs, and ecological restoration.

By clearing built barriers, we allow the block to breathe, enabling movement through its core rather than only around its edges. This intervention makes it possible to reveal and expand the latent green potential of the site, turning an underused interior into a walkable, open, and connected landscape that invites community presence rather than excluding it.

MINDFUL MOVEMENT

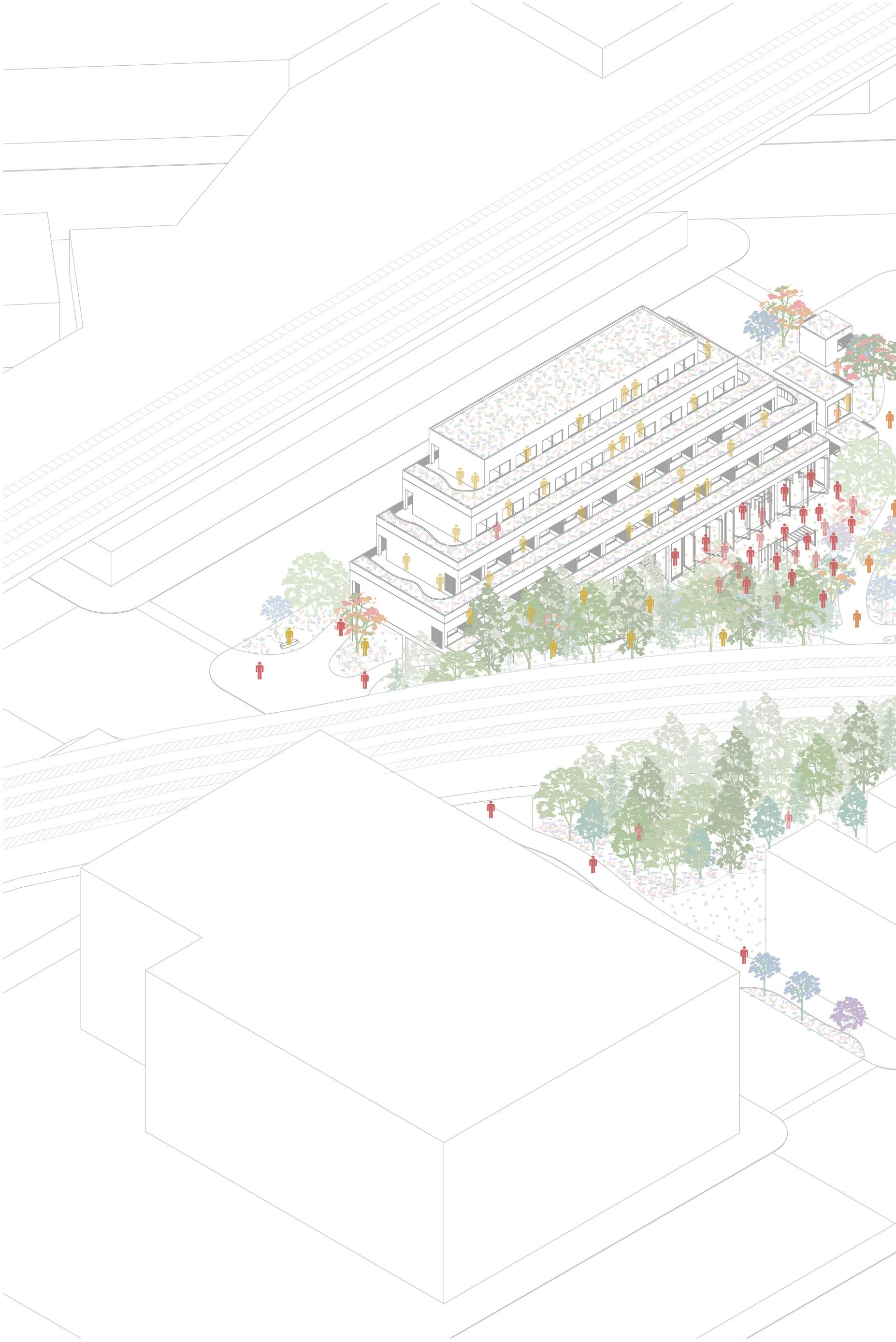

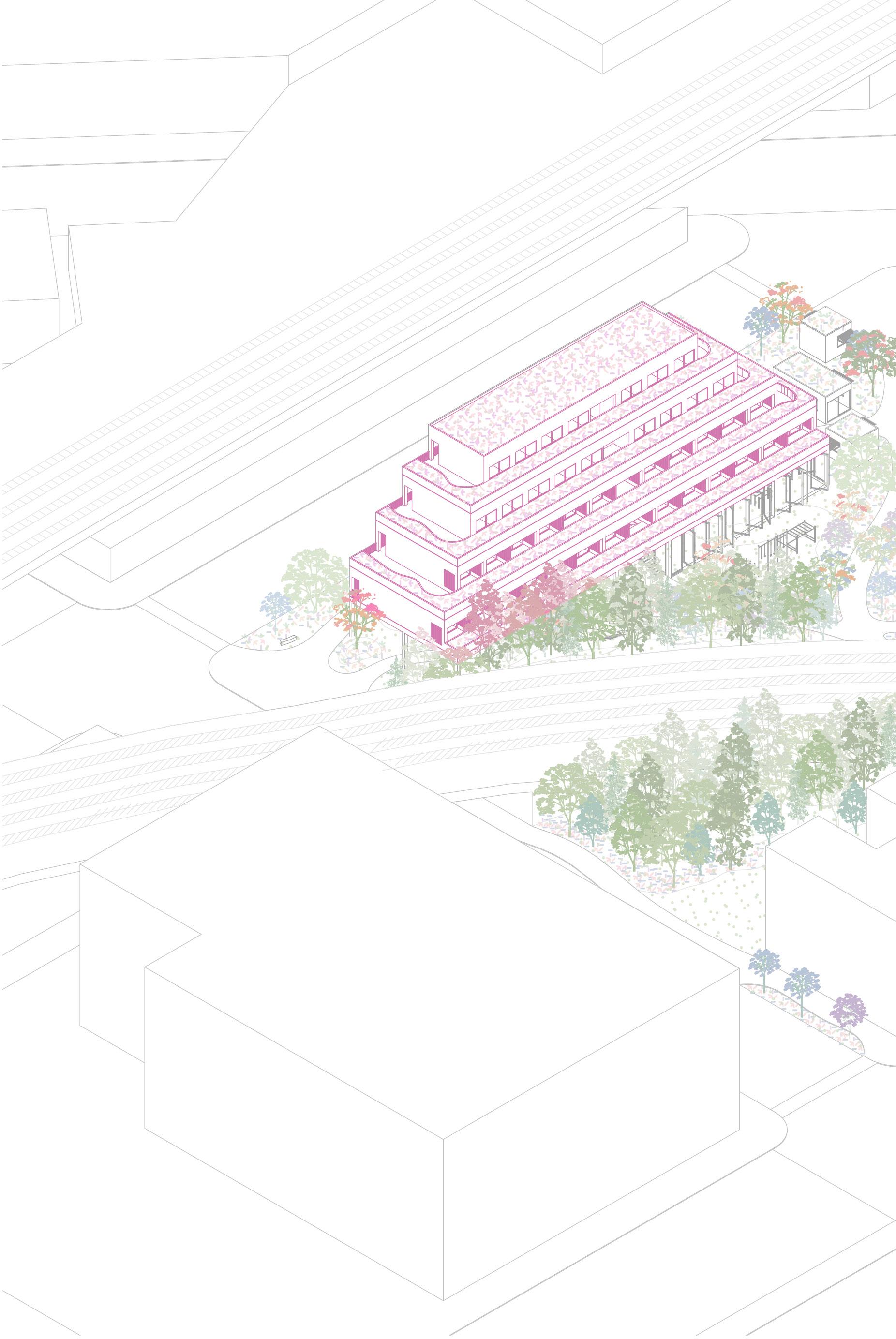

1. The project is initially placed at the corner of the block with an ‘L’-shaped configuration, directing the building’s attention toward the block’s interior.

3. The volumes are rotated to reorient the building toward the center of the block and are strategically shifted to create space for a public access plaza.

2. The mass is divided into two volumes to reduce its overall solidity and create a lighter, more approachable presence within the context.

4. The volumetry steps down progressively toward the block’s interior, echoing the descending rhythm of the slopes that define the site’s frontage.

Restorative Movement

Conscious movement Commerce

Vital movement

Typology A

Typology B

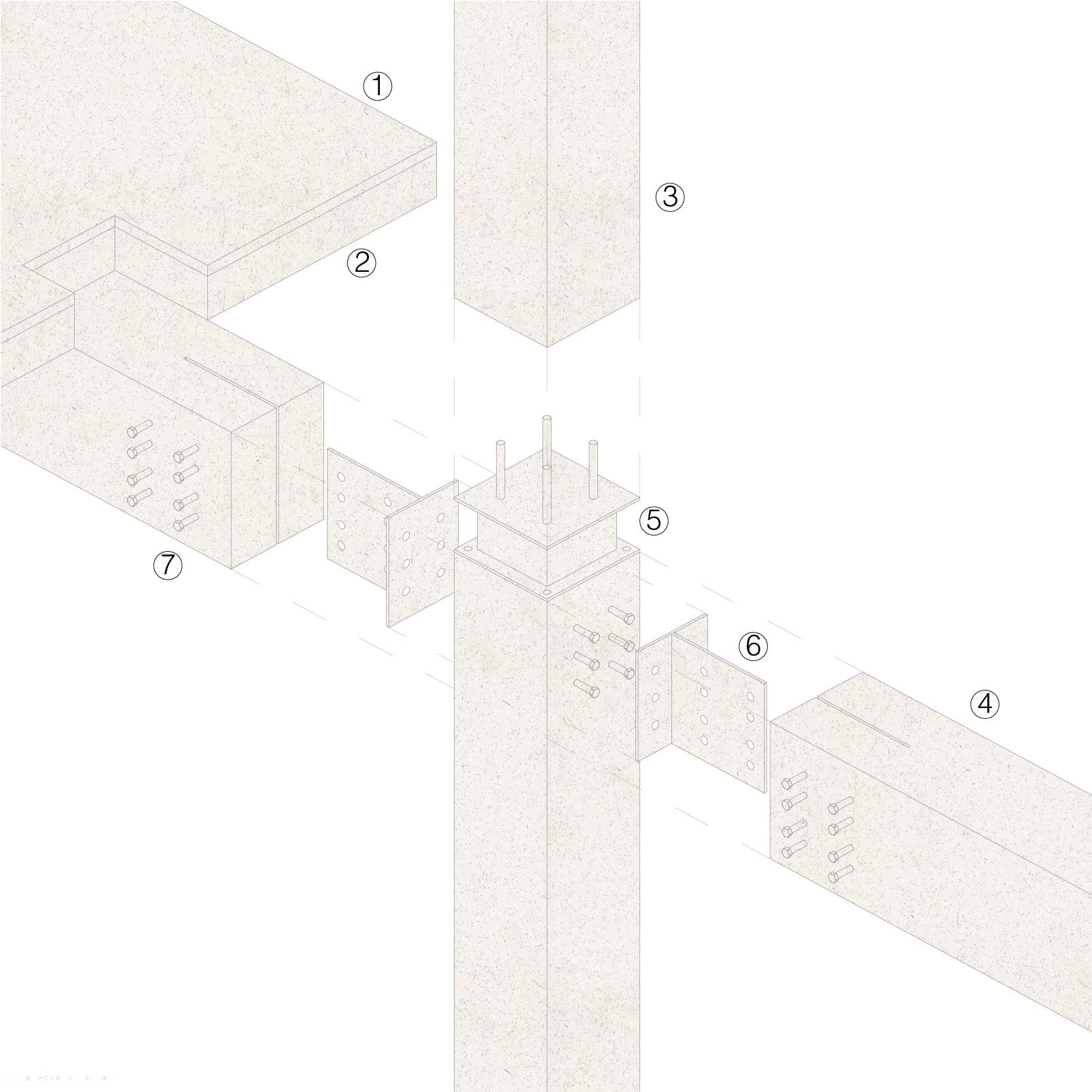

1. 8” x 8” Wooden columns

2. 8” x 8” Wooden beams

3. Cross laminated timber slab

4. Steel fin plate

1. Waterproofing membrane 2. Protection course 3. Root barrier 4. Drainage layer 5. Thermal insulation 6. Aeration layer 7. Moisture retention layer 8. Reservoir layer with aggregate 9. Filter fabric 10. Engineered soil with plantings

1. Surface layer: Crushed red brick (3–10 mm) + Fine sand + Stabilized with lignin

2. Permeable base: Crushed RCA (Recycled Concrete Aggregate, 19–38 mm), Dry-compacted, Approx. thickness: 12–18 cm

3. Drainage sub-base: Washed local gravel (38–50 mm), Thickness: 8–15 cm

4. Existing soil + light improvement

1. Vehicular surface: Permeable paver / thin modular slab with open joints

2. Bedding layer: Sand + fine RCA (3–6 mm), Thickness: 3–5 cm

3. Structural base: Compacted coarse RCA (19–38 mm), Stabilized with lignin, Thickness: 25–35 cm

4. Drainage sub-base: Clean gravel (38–50 mm), Thickness: 10–20 cm

5. Existing soil + light improvement

1. Rain garden soil

2. Clean washed sand min. 7.5 cm

3. Pea gravel min. 7.5 cm

4. Washed rock ¾ - 1 ½ in. (min. 15 cm above and below perforated pipe)

5. Perforated pipe 4 - 8 in. to outfall lower in elevation

Vital Movement emerges as an impulse that reawakens the body’s energy in dialogue with its surroundings. It takes shape through dynamic gestures—jumps, supports, climbs, changes of direction— that spark strength and celebrate natural agility. This movement reminds the body that it was made to explore: that running can be play, that balance invites laughter, that the musculature responds when the space calls for it. When practiced, the city opens up: it feels wider, more breathable, almost as if it were moving alongside those who traverse it.

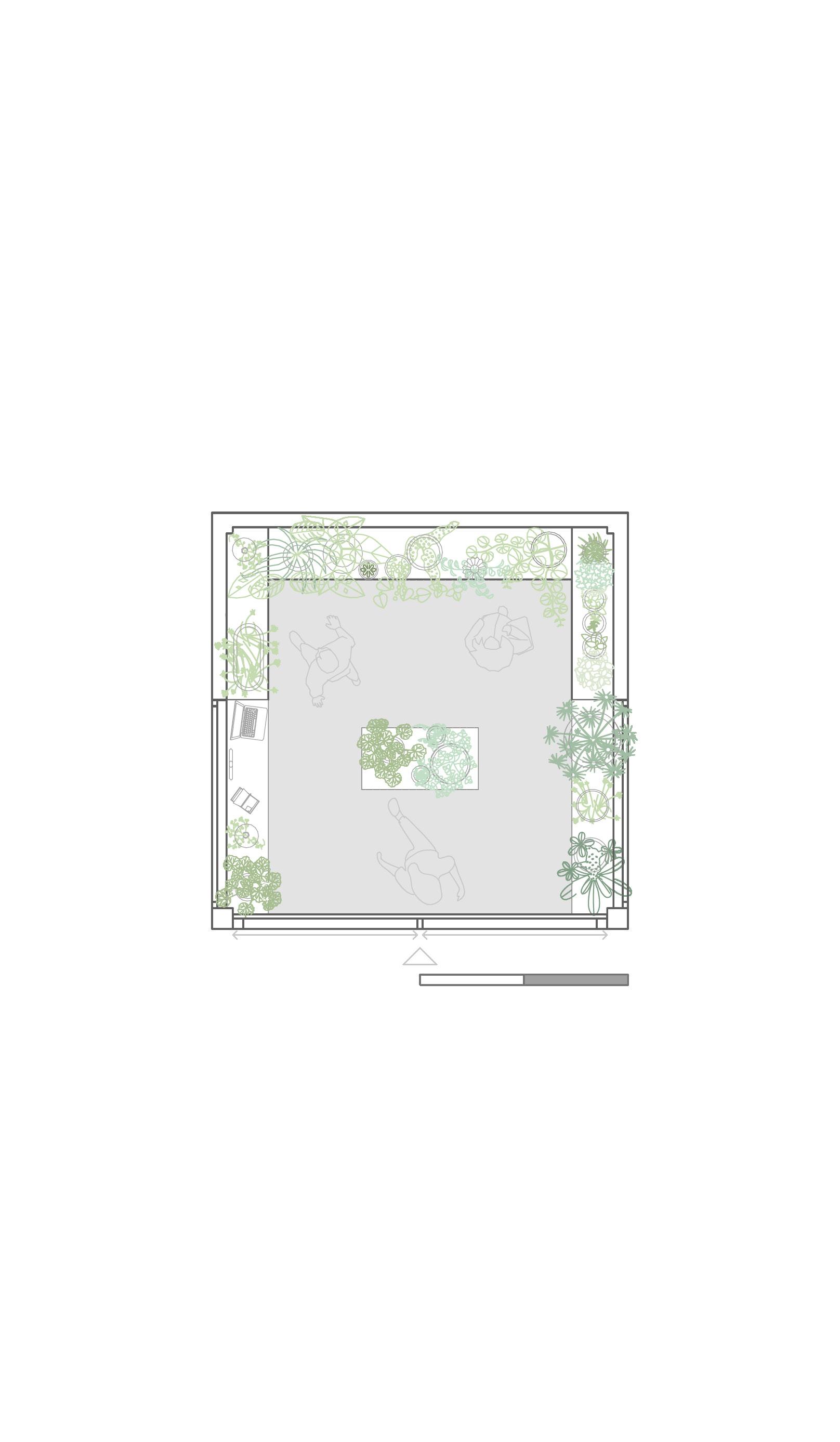

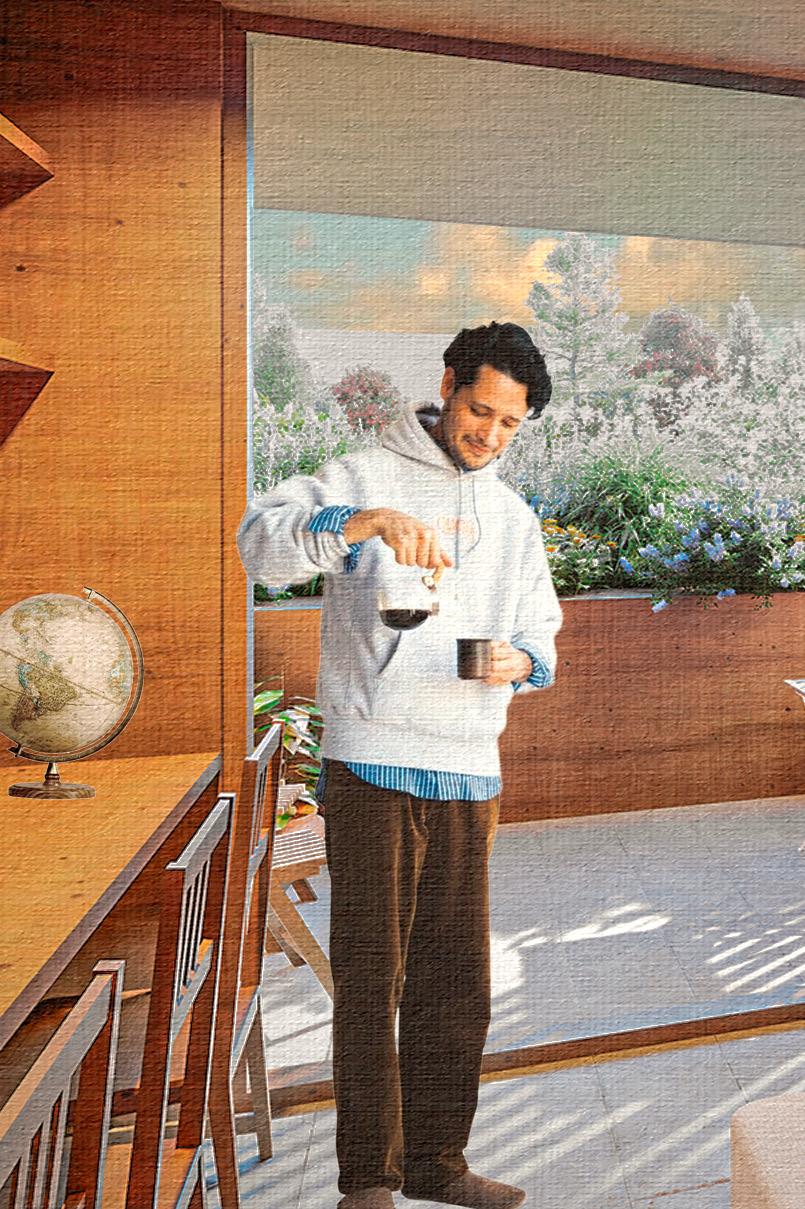

Conscious Movement is a slow conversation between breath, posture, and landscape. Its actions—flowing, mirroring, sustaining, moving gently—reeducate the body and refine presence. Here every gesture finds its tempo, every inhale accompanies the motion, every shift in weight brings clarity. The practice invites a deep listening to the environment: the light marking transitions, the wind softening the pace, the temperature embracing the body. To move in this way is to inhabit space with shared awareness, as if body and territory were learning to move together.

Restorative Movement is a slow return inward. It offers expansive breaths, gentle stretches, meditative walks, and gestures that soothe the nervous system. It is a movement that supports and repairs: it opens the senses, allows the body to be felt without hurry, and creates a pause within urban rhythms. In this practice, time loosens, the mind quiets, and the body regains its natural balance. It does not seek performance, but relief: the possibility of returning to oneself with honesty and softness.

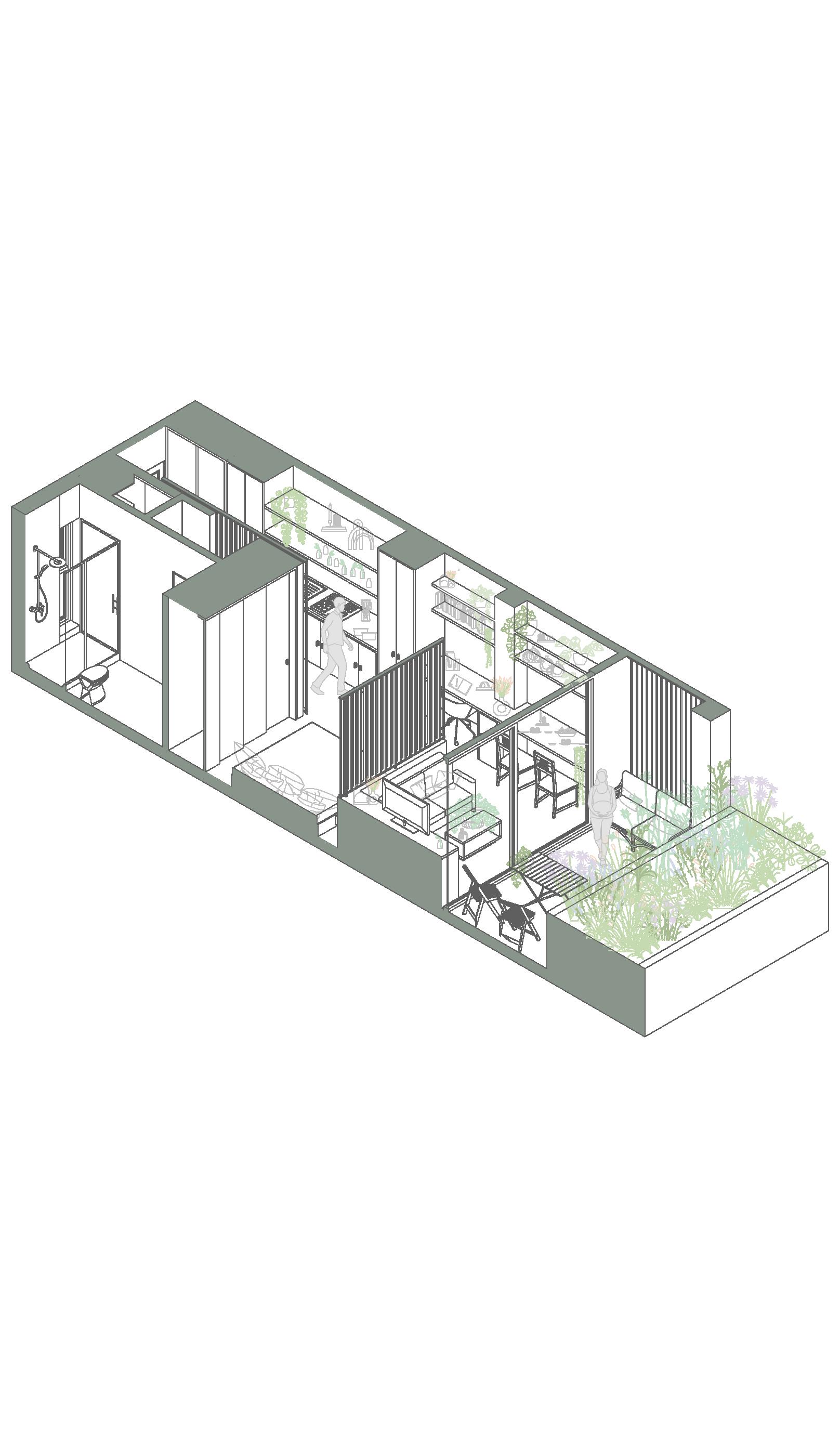

Housing modules

Terrace

Planter

1.Concrete finish

2.Cross laminated timber slab

3.16” x 16” Structural wooden column

4.16” x 16” Structural wooden beam

5.Steel union

6.Steel fin plate

7.Bolt

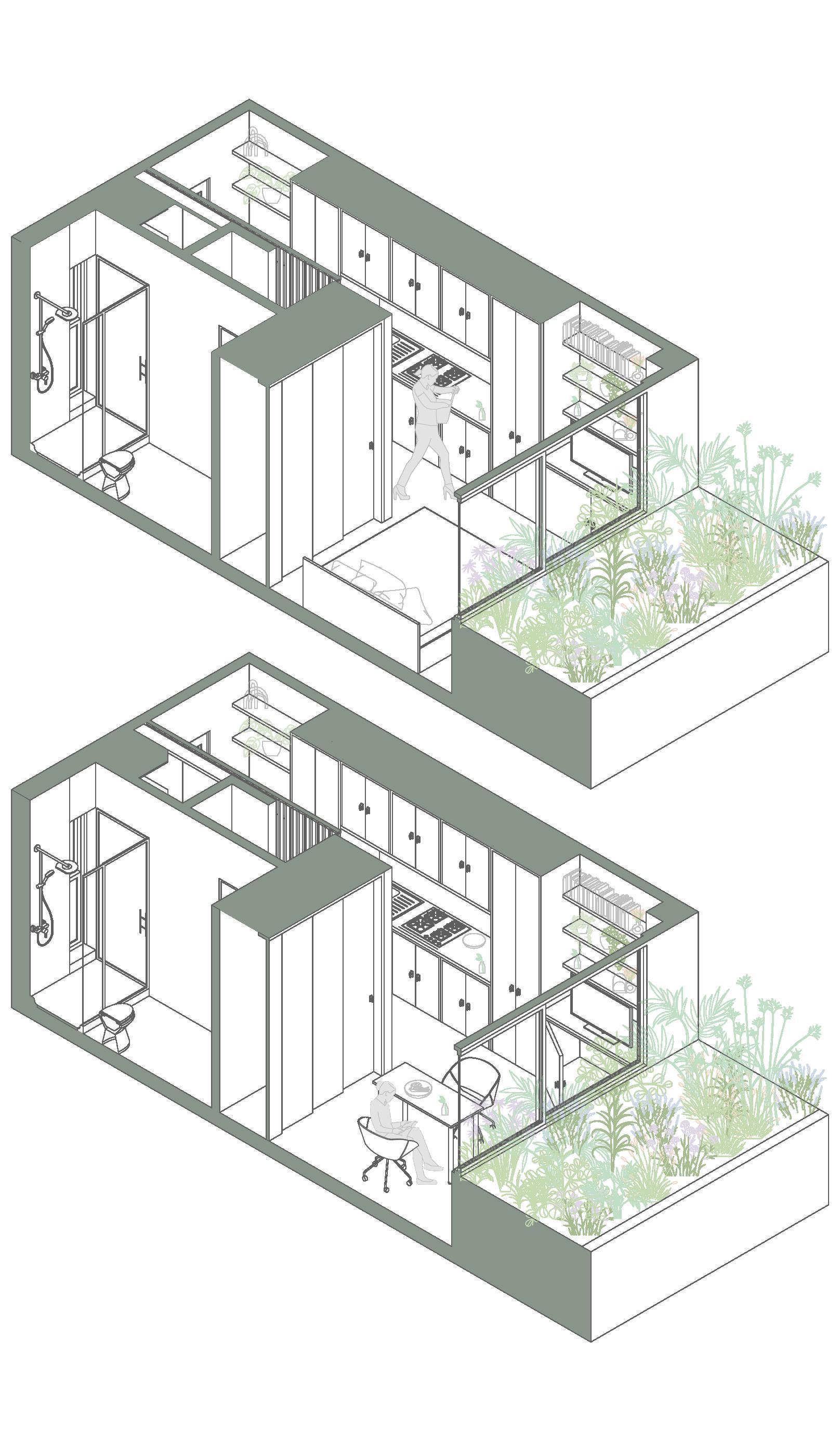

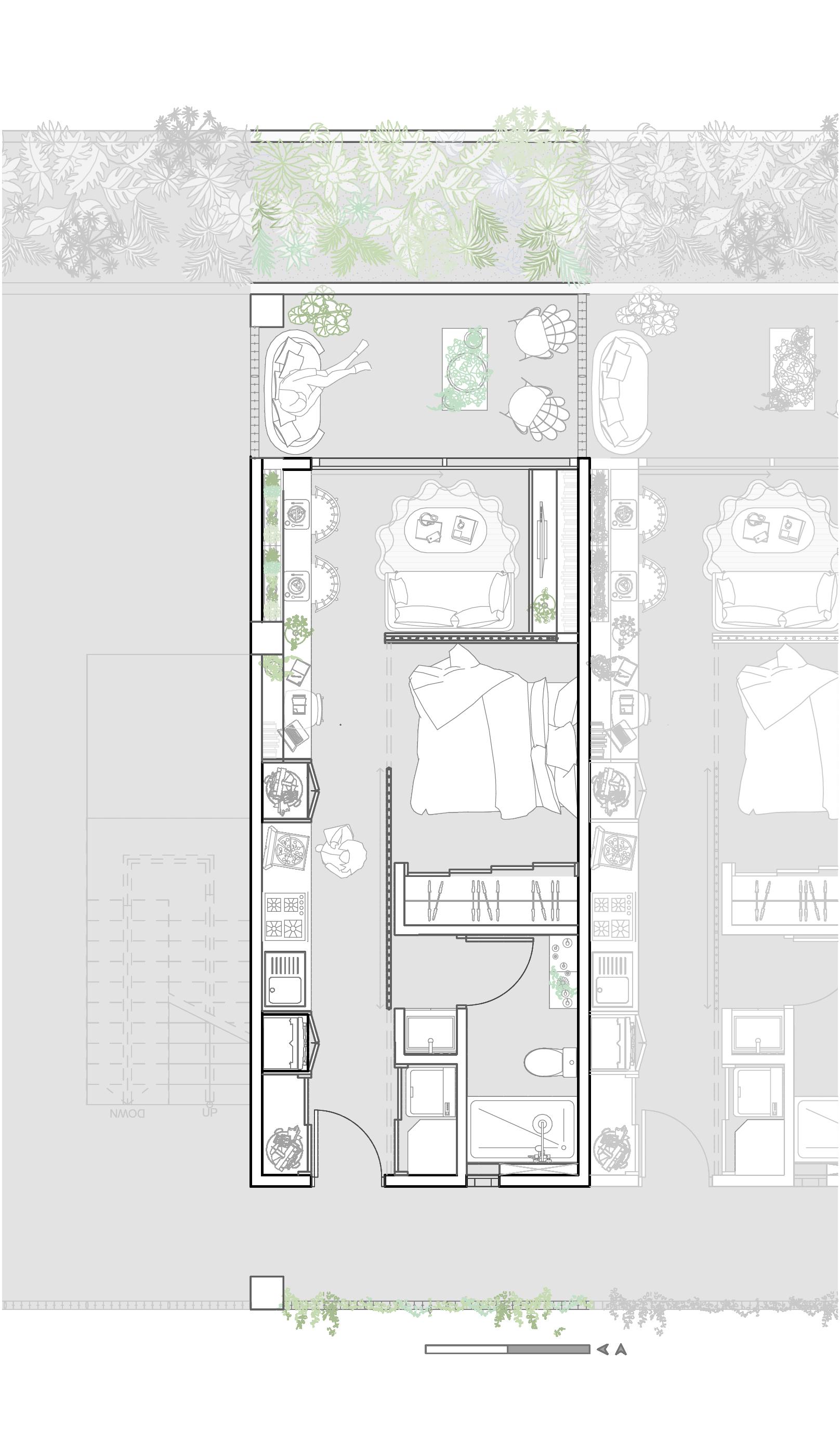

Closet

TV Stand

Planter

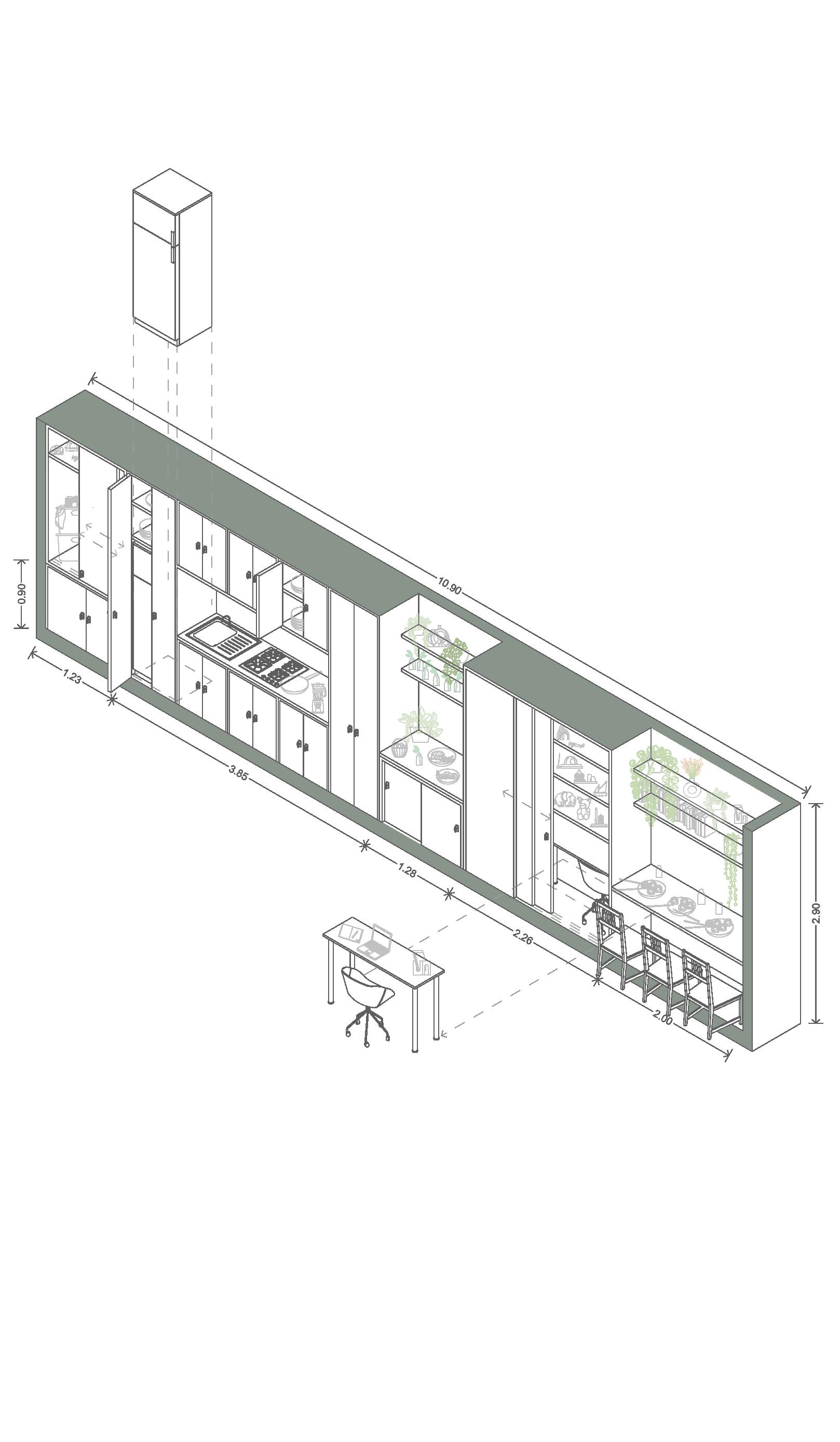

Kitchen

Storage

Sliding Panel

Dividing Panel

Workspace

Dining

Living Room

Planter

Bathroom

Bedroom

Closet

Laundry

Storage

Sliding Panel Kitchen

Workspace

Dividing Panel

Living Room

Dining

Terrace

Bathroom

Bedroom

Closet

Laundry

Planter

Storage

Sliding Panel

Kitchen

Office / Secondary Room

Storage

Dining

Terrace

Living Room

Dividing Panel

Bathroom

Bedroom

Closet

Laundry

Planter

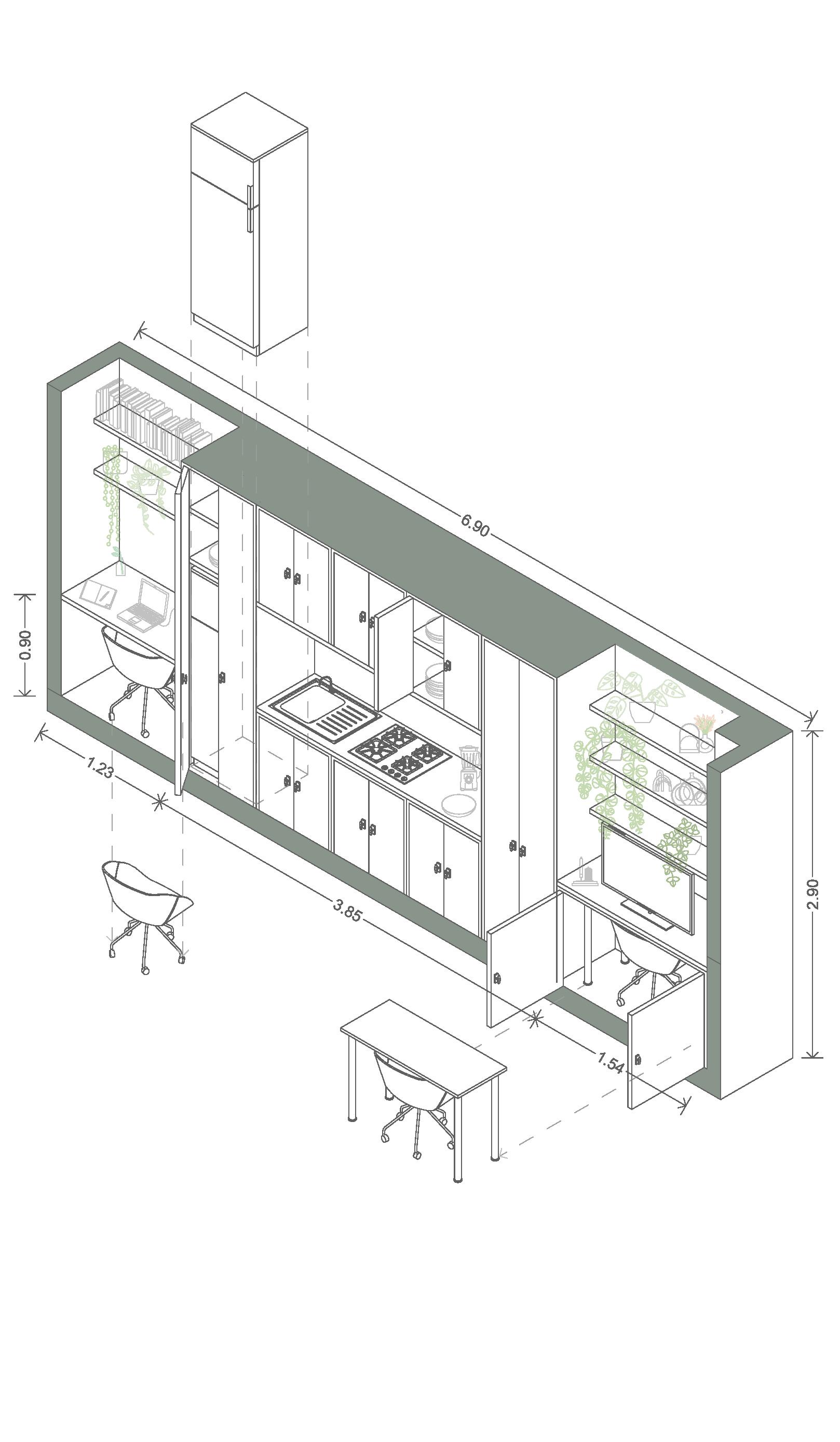

Dining

Table armoire

Fridge

Fridge

Cupboard

TV stand

Chinese Juniper

>40 ft 13-20 ft

Evergreen T

American Holly >40 ft 18-40 ft

Evergreen T

Eastern White Pine >40 ft 20-40 ft

Evergreen I

Blue Spruce 25-40 ft 10-20 ft

Evergreen M

Serviceberry 15-25 ft

Variable

Deciduous T

Crabapple 15-40 ft

20-30 ft

Deciduous T

Prairie

Downy

Saucer Magnolia

25-40 ft

20-30 ft

Deciduous M

Sweetbay Magnolia

25-40 ft 10-20 ft

Deciduous I

Flowering Dogwood

15-40 ft

20 ft

Deciduous

Intolerant

Sugar Maple >40 ft 40-50 ft

Deciduous

Black Gum Tupelo

25-40 ft

20-30 ft

Deciduous M

Drought tolerant

Drought intolerant

Moderately

Golden Alexanders 1’ - 2’

Orange Cornflower

2’ - 2 1/2’ 1 1/2’ - 2’ T

Butterflyweed 1’-2 - 1/2’ 1’ - 3’ T

Blue

2’ - 3’ 1’-1 1/2’ T

Attractions

Bee

Butterflies

Hummingbirds

Birds

Great

Lobelia

Rough Blue Aster 1 1/2’ - 3’ 1 1/2’ - 2’

Rough Blazing 2’ - 5’ 1’ - 1/2’

Pennsylvania Sedge

1/2’ - 1 1/2’ - 2’

Prairie Dropseed 2’ - 3’

2’ - 3’ T

Height Width

Drought tolerant

Drought intolerant

Moderately drought tolerant Sun

Partial sun Shadow T I M

American holly

Eastern white pine

Blue spruce

Downy serviceberry

Prairie crabpple

Flowering dogwood

Saucer magnolia

Sweetbay magnolia

Sugar maple

Black gum tupelo

Golden alexanders

Orange cornflower

Butterflyweed

Great blue lobelia

Rough blazing

Smooth blue aster

Pennsylvania sedge

Prairie dropseed

Spring

Autumn

LEARNING FROM OTHERS

The High Line is an elevated linear park built on a former railway spur on Manhattan’s west side. It transforms abandoned infrastructure into a dynamic public space that blends nature, movement, and urban life. Stretching approximately 1.45 miles, it connects neighborhoods, streets, and cultural landmarks, offering a continuous green corridor within a dense city.

Adaptive reuse is about taking infrastructure that is underused or normally inaccessible and transforming it into meaningful, welcoming public spaces. Urban ecology comes into play by incorporating native plants, walking paths, and gardens, which not only create habitats but also improve the city’s microclimate. The design encourages movement and interaction, providing areas to walk, pause, and gather socially, fostering both physical activity and mindful engagement. Connectivity is also key, linking fragmented parts of the city, much like green corridors connect parks and open spaces. Finally, flexibility and inclusivity ensure that the space can accommodate a variety of activities—recreational, social, and cultural—while remaining seamlessly integrated into the urban fabric.

The Lurie Garden, located in Millennium Park, Chicago, is a 2.5-acre urban garden designed by Piet Oudolf and Kathryn Gustafson. It transforms an urban site into a vibrant, ecologically rich landscape that blends naturalistic planting with public accessibility. The garden is planted with perennial species and native flora, creating a dynamic environment that evolves through the seasons.

The Lurie Garden uses ecological planting with native and perennial species to foster biodiversity and create habitats for birds and insects. Its design incorporates seasonal dynamics, changing visually throughout the year and offering continuous sensory engagement while connecting people with natural cycles. The garden encourages public interaction, inviting walking, contemplation, and immersive experiences within the urban environment. It integrates seamlessly with the dense city context, serving as a natural oasis that allows people to connect with nature without leaving the city. Overall, the design combines aesthetics with ecological function, showing how urban landscapes can support both human experience and environmental health.

Brock Commons Tallwood House is an 18-story residential building that demonstrates how mass timber construction can be a viable, sustainable, and highly efficient alternative in urban environments. The structure combines 17 timber floors (CLT panels on glulam columns) over a concrete base, with concrete cores providing stability.

The project is characterized by fast and controlled construction: thanks to the prefabrication of its components, the timber structure was completed in approximately 70 days from the arrival of materials on site—considerably faster than a conventional project of this scale. Its design houses a student residence with over 400 beds, combining private spaces (rooms) with shared areas, which promotes community, social interaction, and functionality.

From an environmental and sustainability perspective, Brock Commons stands out because the timber used acts as a carbon sink, significantly reducing construction-related emissions compared to traditional materials. Additionally, its hybrid typology— timber + concrete + steel—demonstrates flexibility, allowing structural efficiency and sustainability to coexist without compromising safety, comfort, or code requirements (even under strict seismic or fire protection standards).

a+t Architecture Publishers (Aurora Fernández Per, Javier Mozas & Javier Arpa, eds.). This Is Hybrid: An Analysis of MixedUse Buildings. a+t Architecture, VitoriaGasteiz, 2011. ISBN: 978-84-614-6452-4

Creating Wildness: Piet Oudolf’s Private Gardens. (n.d.). FLOWERMAG. https:// flowermag.com/piet-oudolf-gardenshummelo/

High Line. (n.d.). The High Line. https:// www.thehighline.org/ Northern Illinois

Think Wood. (2022, September 16). Brock Commons Tallwood House - Think Wood. https://www.thinkwood.com/constructionprojects/brock-commons-tallwood-house

Think Wood, & WoodWorks. (2022). Mass Timber Design Manual (Vol. 2). Think Wood / WoodWorks.

Tree Species List. (n.d.). The Morton Arboretum. https://mortonarb.org/app/ uploads/2021/05/Northern_Illinois_Tree_ Species_List.pdf ULUC, Sea Grant, & Storm water home. (n.d.). Illinois Native

Oudolf, P., & Kingsbury, N. (2013). Planting: A New Perspective. Timber Press

Plants for the Home Landscape. Illinois Extention ULUc. https://iiseagrant.org/wpcontent/uploads/2024/03/Illinois-NativePlants-for-the-Home-Landscape_Spanish. pdf Whats blooming. (n.d.). Lurie Garden. https://www.luriegarden.org/

Structurlam Mass Timber Technical Guide. (2020) Structurlam Mass Timber U.S., Inc.

Zimmermann, A. (Ed.). (2015). Constructing Landscape: Materials, Techniques, Structural Components (3rd ed.). Birkhäuser.

MOVEMENT IS THE MOST AUTHENTIC

AUTHENTIC WAY TO INHABIT THE WORLD.