I ntroduction

Have you ever needed to make a decision that truly scared you?

I did, while I was writing this book.

I love writing all of my books. But some were certainly more difficult to write than others, and one of the difficult ones was Jolly Foul Play. Working on it was the first time I experienced real panic during a drafting process. I knew I had a great idea – a murder during a fireworks display, a wildly daring killer who struck while everyone was looking the other way – and my brain was full of the lovely set-piece moments that were going to make the story sing. But no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t get my suspects’ movements and alibis to fit together. It just didn’t make any sense.

I knew I had to get this right. I had people who were waiting for the next instalment of Daisy and Hazel’s adventures. I didn’t want to disappoint them. And more importantly, I didn’t want to disappoint myself. My mysteries are always, first and foremost, puzzles

I set for myself. The moment I’ve untangled all the problems with the story, and I can feel it flowing perfectly from murder to denouement, I know it’s ready for publication.

I was nowhere near that.

So what could I do?

Unfortunately, I knew. I had to quit my job. I had actually known this for months, but I had been trying to put it off. The thing is, I loved my job very much. While I had been writing the first books in the Murder Most Unladylike series, I’d also been working in the editorial department of a publishing house. This was something I didn’t want to say goodbye to. I was also very afraid to. What if people stopped reading my books? What would I do then?

But sometime around the complete despair of the second draft of Jolly Foul Play, I realized that something needed to change. I had to try. So I took a deep breath and handed in my notice.

And when I woke up the next morning, I realized something. I was finally a full-time author – something that had been a secret dream of mine for years, but one I had been too afraid to admit. Whatever happened next, I would at least be able to live that dream for a while.

I went to the British Library every day, all day, for a week, instead of trying to cram in writing in evenings

and mornings and weekends, and I discovered that the reason why nothing in Jolly Foul Play made sense to me was just because I had been very tired.

I fixed all the issues with the draft in days. Everyone’s alibis were suddenly clear. I could see the story again, as though a fog had lifted around me. Very embarrassingly, Jolly Foul Play turned out to be the best book I’d ever written.

I think you can tell I was afraid when I was initially working on this story. Daisy and Hazel are at odds with each other, and the whole of Deepdean feels unsettled and angry. But those redrafts I was able to do at the end of the process turned its darkness into something ultimately hopeful.

People often tell me that Jolly Foul Play is their favourite book, and ten years on I can understand why. It’s clever and intricate, and it isn’t afraid to show something that I think can never be explored enough in fiction: how absolutely horrible girls can be to each other. For inspiration I took two of my very favourite stories about blackmail and backstabbing: the Sherlock Holmes short story ‘The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton’ and the movie Mean Girls. I remember what a revelation that film was to me when I first watched it. It gets to the heart of how terrible unhappy female friendships can be, and how destructive (and self-destructive) it is to be locked in that kind of

emotional battle. That’s what I wanted to explore in Jolly Foul Play, and what I think I succeeded in showing. But of course, at the end, all that cruelty is overpowered by real goodness and strong friendship. Daisy and Hazel and the rest of their friends are bold and brave enough to fix their problems, both with the crime and with each other, just as I was able to solve my problems with the story.

Writing Jolly Foul Play reminded me that doing the right thing is terrifying sometimes – but it’s always worth taking that risk. My favourite moment in this book is Beanie’s great act of bravery at the end of the story. You can’t be brave without being afraid – and, like so much in my own writing, I now realize I was writing my own decision into the book when I wrote Beanie taking that terrified leap of faith.

All these years later, I am still deeply proud of both of us.

Robin

Stevens 2026

Being an account of The Case of the Murder of Elizabeth Hurst, an investigation by the Wells and Wong Detective Society.

Written by Hazel Wong (Detective Society Vice-President and Secretary), aged 14.

Begun Wednesday 6th November 1935.

THE STAFF

Miss Barnard – Headmistress

Miss Lappet – History and Latin mistress

Mr MacLean – Reverend

Mademoiselle Renauld, ‘Mamzelle’ – French mistress

Miss Runcible – Science mistress

Miss Morris – Music and Art mistress

Miss Dodgson – English mistress

Miss Talent – Games mistress

Mrs Minn, ‘Minny’ – Nurse

Mr Jones – Handyman

Matron – Matron

THE GIRLS

Daisy Wells – Fourth Former and President of the Wells & Wong Detective Society

Hazel Wong – Fourth Former and Vice-President and Secretary of the Wells & Wong Detective Society

HEAD GIRL

Elizabeth Hurst

PREFECTS

Florence Hamersley

Lettice Prestwich

Una Dichmann

Enid Gaines

Margaret Dolliswood

BIG GIRLS

Pippa Daventry

Alice Murgatroyd

Astrid Frith

Heather Montefiore

Emmeline Moss

Jennifer Stone

Elsie Drew-Peters

FOURTH FORMERS

Lavinia Temple – Assistant and Friend of the Detective Society

Rebecca ‘Beanie’ Martineau – Assistant and Friend of the Detective Society

Kitty Freebody – Assistant and Friend of the Detective Society

Clementine Delacroix

Sophie Croke-Finchley

Rose Pritchett

Jose Pritchett

THIRD FORMERS

Binny Freebody

Martha Grey

Alma Collingwood

The Marys

SECOND FORMER

Betsy North

FIRST FORMERS

Emily Dow

Charlotte Waiting

1We were all looking up, and so we missed the murder. I have never seen Daisy so furious. She has been grinding her teeth (so hard that my teeth ache in sympathy) and saying, ‘Oh, Hazel! How could we not notice it? We were on the spot !’

You see, Daisy needs to know things, and see everything, and get in everywhere. Being reminded that despite all the measures she puts in place (having informants in the younger years, ingratiating herself with the older girls and Jones the handyman and the mistresses), there are still things going on at Deepdean that she does not understand – well, that has put her in an even worse mood than the one she has been in lately.

And, if I am honest, I feel strangely ashamed. The Detective Society has solved three real murder mysteries so far, and yet we still missed a murder taking place

under our noses, in our very own Deepdean School for Girls – the place where we began our detective careers one year ago.

It really is funny to think about that. It seems in a way as though we have not moved at all – or as though we have made a circle, and come all the way back to the beginning again. I suppose I still look almost exactly like the Hazel I was when I ran into the Gym and found Miss Bell, our Science mistress, lying on the floor last October. I am not much taller, anyway. When I measured myself last week, I found I have hardly grown at all – or at least, not upwards. My hair is still straight and dark brown, my face is still round, and I still have the spot on my nose (I suppose it must be a different spot, but it does not look that way). Inside, though, I feel quite different. All the things that have happened the past year have made me quite a new shape, I think – one who has faced up to the murderer at Daisy’s home, Fallingford, and defied my father to solve the Orient Express case. On the other hand, sometimes I think that even though Daisy keeps on shooting upwards, and becoming blonder and lovelier than ever, she has stayed the same inside. She bounces back from things, like a rubber ball – not even what happened at Fallingford could truly alter her.

Before the fifth of November, I had not been enjoying Deepdean much this term. Just like the changes that

have taken place in me, the school has felt different from last year, and not at all in a good way. It has felt as though something awful were rushing towards us all term. Last night was dreadful, but now it has happened I feel almost relieved. It is like the difference between waiting to go in to the dentist and sitting in his chair.

And now that there is a murder to solve, Daisy and I can be the Detective Society again. It is sometimes difficult being Daisy’s best friend, but being her Vice- President and Secretary is much more simple. This case, though, will not be simple at all.

You see, the person who has died – who we think has been murdered – is our new Head Girl.

This case began yesterday, on Tuesday the fifth of November, but all the same, to explain it properly I must wind backwards, all the way to the end of summer term.

That was when Daisy and I were preoccupied with our upcoming holiday on the Orient Express, but although we were not paying much attention to them at the time, extremely important things were happening with Miss Barnard and the Big Girls.

For the purposes of this new casebook, I must mention who Miss Barnard is. You see, after the case of Miss Bell was over, there were almost no mistresses left at Deepdean. This means that everyone except redhaired, dramatic Mamzelle, old Mr MacLean, and Miss Lappet with her big bosom, is entirely new since last December. Miss Barnard is our new Headmistress. She is slender and tall, and I think quite young – at least,

there is still brown in her hair. She is also calm, and kind, and sensible, and she has a way of making you feel safe – something Deepdean badly needs, after last year. But sometimes kindness is not the best thing. As Daisy always says, it is no good being nice if the people you are being nice to are not nice themselves.

Now Miss Griffin, our last Headmistress, always chose the next Head Girl at the end of each school year. She knew every girl’s character, and judged it carefully before she made her choice. But Miss Barnard did not know any of the Big Girls really well by the time it came to make her selection last summer term, and so instead of choosing, she let it go to a vote. And that was quite disastrous, for it meant that Elizabeth Hurst could bend the vote her way, and have herself elected Head Girl.

The outside of Elizabeth Hurst was not particularly remarkable. She was tall and broad- shouldered, with a pale face and sandy hair, just like most of the girls at Deepdean. The only clue as to what was inside her was the smile at one side of her mouth. It never went away, and it was not a very nice smile. It looked as though she was remembering something nasty about you, and deciding whether or not to say it aloud. That smile was the truth about her, for Elizabeth was in the business of secrets.

That makes her sound somewhat like Daisy – but while Daisy likes to know things just for the pleasure of

it, to make things fit in her head, Elizabeth used the things she knew. Just like a cat snatching little birds out of their nests, she took all the information she could find about each girl at Deepdean, and kept it. And she didn’t simply use the information she gathered – or at least, not immediately. Instead, she would store it up like a present for the day when it would become useful to her. And when it did – well, then you would be ruined. There had been one girl, Nina Lamont, generally thought to be the front runner for the Head Girl position – until Elizabeth was seen paying Miss Barnard a visit one morning, looking very grave. Later that day it came out that Nina had stolen from the Benefactors’ Fund. And after that no one could vote for her at all. She did not even come back to Deepdean this year. Apparently, she had been sent to prison –although Daisy said that this was not true, and that it was only to a school in France.

Elizabeth led a group of five girls, the oddest and angriest and most hateful in their year. They were Elizabeth’s helpers, like a bruising, bullying version of Daisy’s little informants, and they went about prising facts out of all us younger years and feeding them back to Elizabeth. We called them the Five, and we hated them.

So you can see why everyone at Deepdean was quite terrified of Elizabeth, and why we all got the most

horrible thrill when we heard that she had indeed been elected Head Girl – and, as was tradition, had chosen five other Big Girls to be her prefects. Of course, she chose her helpers – and so when we came back to Deepdean this year, Elizabeth and the Five were running the school.

We had been afraid of Elizabeth and the Five, but all the same, I do not think we quite understood how dreadful the new year would be until we were a few weeks into it. At first, the autumn term felt as clean and full of possibility as ever – new timetables, new pencils and inkwells, and exercise books with none of their pages torn out to pass notes. We were fourth formers, closer than ever to being Big Girls, and we undid our top buttons daringly in celebration. Kitty even tried to leave her hair down, although Miss Lappet told her off at once. Clementine had a new contraband bracelet, and Beanie had a dormouse which she hid in her tuck box (it was called Chutney, and all it did was sleep). It seemed as though this term might be better than the last – the shadow of Fallingford had finally lifted, for The Trial was over and the murderer in prison. But then the Five began their punishments.

Elizabeth was absolutely in control of the school’s discipline, and behind everything that happened, but the genius of her was that she never carried out any of the punishments. It was only ever the Five who came after us, and they did it quite dreadfully.

Red-headed, fierce, athletic Florence Hamersley, captain of the hockey team and in training for the hurdles at next summer’s Olympics, was a stickler for laziness. If you were late to breakfast or dinner, or slow at toothbrushes in the evening, her hand would come down on your shoulder and the next thing you knew you were running ten laps around House in the cold and the rain. If you did it slowly, you had to run twenty.

Dark-haired Lettice Prestwich was even nastier. She ought to have been pretty – she would have been, if she were not so thin. With her, we lived on shifting sand, waiting for the catastrophe. Any flaw in your uniform at all – a missing button, an undone tie – and she would pounce on you, shrieking. She made the shrimps cry almost every day. Once she marched into our dorm and, hearing squeaks from Beanie’s tuck box, discovered Chutney the dormouse. She took him to Matron at once, who put him outside – Beanie sobbed, of course, and we were all furious. Beanie, our friend and dorm mate, is very small, and not at all good at schoolwork –but she is good , and that counts for quite a lot. But there was nothing to be done. Chutney was gone.

Una Dichmann is from Germany, where her father has a most important position in the Nazi Party, and she is blonde and pretty as a fairy- tale princess – but if you failed to treat her, or any of the rest of the Five, with the respect you ought, she would have you carrying her books between lessons and shouting at you if you did not move quickly enough.

Enid Gaines does not look as threatening as the others, at first. She is a swot, Deepdean’s great hope for a Classics place at Oxford next year, and her nose is always in a book. She is small – almost as short as I am –and has a dull, forgettable face. But if you laughed in the corridors, or whispered in Prayers, she would turn on you, and you would find yourself writing lines –I must obey my elders and betters – a hundred times at lunch break.

The last member of the Five is Margaret Dolliswood. She is large and angry – unhappiness radiates off her in waves. Fail to get out of her way, or draw attention to yourself at meals and bunbreaks, and you would find your food snatched out of your hands and your wrists pinched. I have gone hungry many times because of her – which I think the worst cruelty of all.

The Five’s punishments were dreadful, and there was no escape from them. When we went up to House, one would always be taking our Prep, and another supervising the common room, and they all sat at the

end of our tables at dinner. We were under siege, and the worst thing was that none of the mistresses or Matron noticed. Grown- ups never do see this sort of thing – to them, any harm children do to each other does not really matter.

It felt as though we were rabbits waiting for the fox to pounce. Elizabeth and her five prefects patrolled the school, and their viciousness spread down, until we were all at each other’s throats. They made us all so miserable that even the nicest girls began to argue and snipe at each other horribly. Under the force of the Big Girls’ nastiness, we all became nastier too – the fifth formers to the fourth, us to the third, the third to the second and so on. All the old alliances broke down under the pressure of it. Deepdean itself was changed, so much so that although its black- and- white corridors and wide windows and chalk smell was no different, I could barely recognize it.

Daisy, of course, was furious. There are certain places that, in her own mind, belong to her. Deepdean is one of them, and the fact that it had gone wrong sent her into an absolute rage. I had decided that this year would simply have to be endured, like any other unpleasant thing, but Daisy does not endure. She cannot bear not to try to solve any problem that she comes up against, and Elizabeth and the Five became the most fascinating of problems, all the more so because the truth was that

there was nothing she could do about them. She did not even have her old confidant King Henry to give her prestige among the Big Girls – for, of course, King Henry was no longer our Head Girl. She was far away at Cambridge, where Daisy could not use her.

‘I’m watching them,’ Daisy told me, over and over again. ‘I’m watching her. Elizabeth can’t think she’ll get away with it. She can’t be allowed.’

It seemed to me that she could – and that she was. Elizabeth had committed no crime apart from nastiness. Her blackmail was so subtle that there was nothing we could pin on her, nothing we could detect. In fact the Detective Society had no cases at all this term, apart from the strange case of Violet Darby which Daisy solved in a day in September. (Daisy is rather proud of that case.)

‘I’d like to squash Elizabeth’s head,’ said Lavinia furiously as Beanie sobbed over her fifth detention in two weeks (for misspelling the word ‘privilege’ in the essay she wrote for her fourth detention. This was not fair at all. Beanie struggles with making her words the right shape, and her numbers add up properly on the page). ‘I’d like to squash her into pulp.’

We all agreed with her, but all the same we (except Daisy) understood how hopeless it was to expect anything to change.

That is, until what happened on Guy Fawkes Night.

The fireworks display on the fifth of November was Miss Runcible’s idea at first. Miss Runcible is our new Science mistress. She is very cheerful and excited about life – which is odd, after cold Miss Bell. Her Science lessons are always very full of strong smells and explosions (which make them excellent for pranks – in the third week Kitty tricked Clementine into getting too close to one of Miss Runcible’s experiments, then there was a pop! and Clementine’s eyebrows burned away to nothing), so I suppose it was not at all surprising that she should want to hold a proper Guy Fawkes Night celebration, even though such a thing had never happened at Deepdean before.

Miss Barnard announced it in Prayers towards the end of October.

‘Girls,’ she said, standing very calm and collected at the lectern. ‘On the fifth of November, Guy Fawkes

Night, you are to go up to House for dinner and then march back down to the sports field for a bonfire and a fireworks display. The prefects and Head Girl will be supervising, as well as Miss Runcible and myself, and you are all to have an excellent time.’

We all went rather tense. I remember thinking how very optimistic Miss Barnard could be, and how concerning this plan of hers was. It was yet another opportunity for the younger girls to be bullied by Elizabeth and the Five – and this time we would be shivering on a cold sports pitch while it happened.

Then I looked over at Daisy. As I knew she would be, she was staring not at Miss Barnard, but at Elizabeth and the Five. I saw the familiar crinkle appearing at the top of her nose. I knew that expression, and I felt rather apprehensive. I knew that Daisy was still looking for a way in to Elizabeth and the Five – but I could not see how a Bonfire Night celebration would be any help with that at all. I almost opened my mouth to tell her to leave it, but I knew it would only make her more determined. So I began to think about something quite different: the letter that would almost certainly be waiting for me when we got up to House for lunch that day.

You see, this term I have a secret. I have been writing to someone, and they have been writing back to me. The Hazel of a year ago would never have dared to keep such a thing hidden from Daisy – but I am not the Hazel

of a year ago. I am still not a heroine, but I think I am a little braver.

There is now quite a pile of papers at the bottom of my tuck box. Every time I slip another letter on top of it the fizzing in my chest grows stronger. It is lovely, but all the same it turns me jumpy. The two of us send each other logic puzzles, and funny things that we notice at school, and little cases – nothing at all, really, but I know that if Daisy were to find out, she would be terribly cross. She does not like me detecting with anyone else, you see – in her mind, I am her detective friend, and although we have assistants, no one else can truly be a part of that.

I was still thinking about the letters, and what Daisy would say if she knew, on the evening of the murder.

Our dorm walked down to the sports field together on Tuesday night after dinner, wrapped up in our hats and scarves and shivering. No one was feeling cheerful. We were having one of those strange not- arguments that happen so much this term, where everyone simply complains at each other and you are left feeling worn out and cross.

‘Beanie’s still upset about that fifth former taking her pudding last night, even though I’ve told her not to be,’ said our dorm mate Lavinia, shaking back her heavy dark hair. ‘After all, I got her one of the shrimps’, didn’t I? I don’t see what the fuss is.’

‘You can’t take other people’s things!’ said our other dorm mate, Kitty, self-righteously. Kitty has brown hair and freckles, and loves to gossip. ‘It’s not nice, Lavinia. You wouldn’t have done it last year.’

‘Yes I would,’ said Lavinia. ‘Don’t be po - faced, Kitty.’

Kitty scowled. ‘Well, you might have done, but you still oughtn’t.’

‘Everyone’s so nasty this year,’ said Beanie sadly.

‘It’s Elizabeth Hurst,’ I said, stepping in without meaning to, and then wincing. I knew what must come next, and sure enough—

‘Exactly!’ said Daisy triumphantly. ‘I’ve been saying this all term, Hazel. Elizabeth Hurst and the Five are the problem, and we must solve it.’

‘It isn’t a problem we can solve!’ I said. ‘Oh, do give over, Daisy.’

I suddenly felt the difference between us. All of Daisy’s head was obsessed with Elizabeth Hurst, focused on her like a spotlight, while all of mine was wrapped around the newest letter that had been waiting for me that afternoon, as I’d hoped. It was all I could see, overlaying the dark line of girls in front of us, the pavilion and the flare of the lit bonfire beyond.

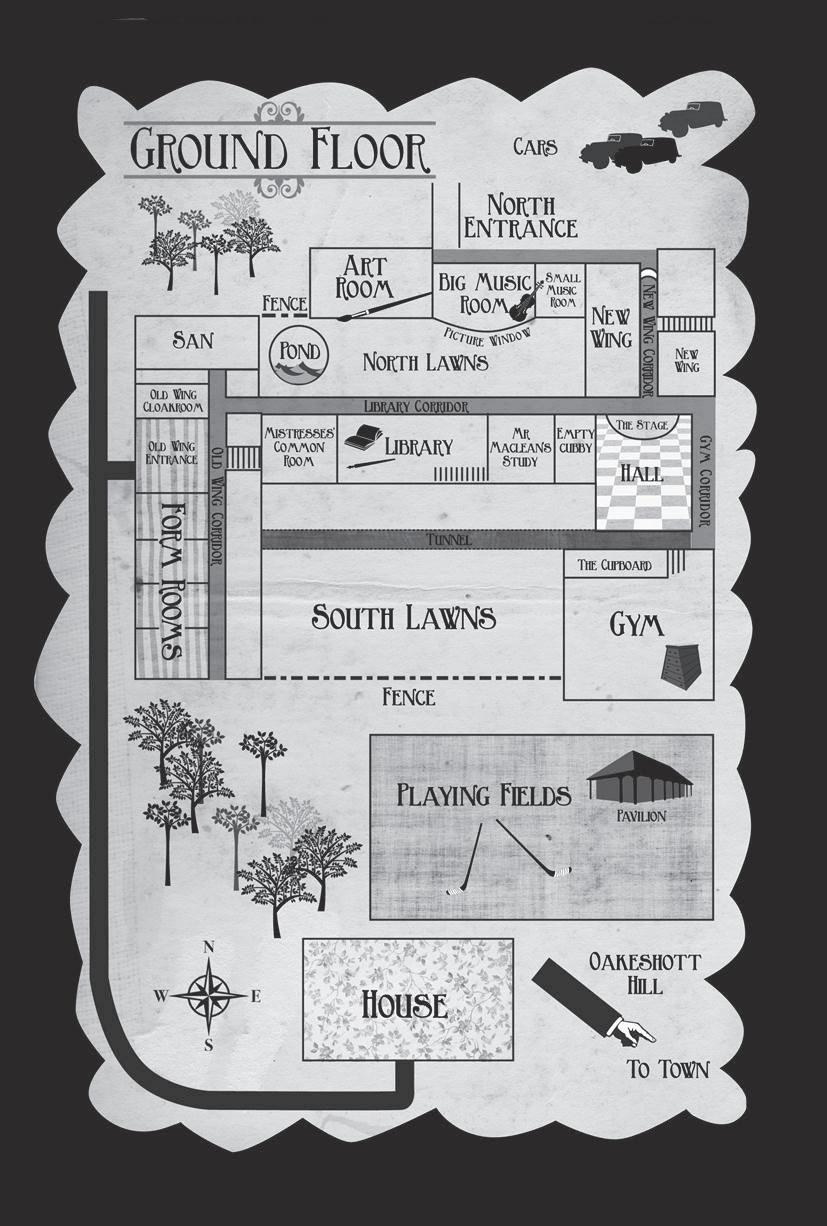

Apart from the brightness of the bonfire, the field was dark, little tendrils of fog drifting through the crowd. I could only dimly make out the shadow of the pavilion behind the fire, and the girls crowding in front of it looked like scribbles on a page. I could not even see the trees on the far edge of the pitch that led into Oakeshott Woods, although I knew they were there. I breathed out and my breath misted in front of me. I shuddered. I do not like English winter nights at all.

Through the gates we walked, and there was Miss Barnard, calmly greeting all of the girls as they went by. Next to her was Elizabeth Hurst. She was smiling as usual, but her smile looked hard and fake. For once the Five were not behind her, but ranged away to the side, with a gap between her and them. They were not smiling at all. I would like to say that I wondered about this, and that I caught how Margaret was clenching her fists, and

how Florence, wrapped in her scarf, was pale, and Una flushed, and Enid was poison- faced and Lettice was shaking, her thin form looking unusually bulky in her big Deepdean coat – but I did not. I was distracted.

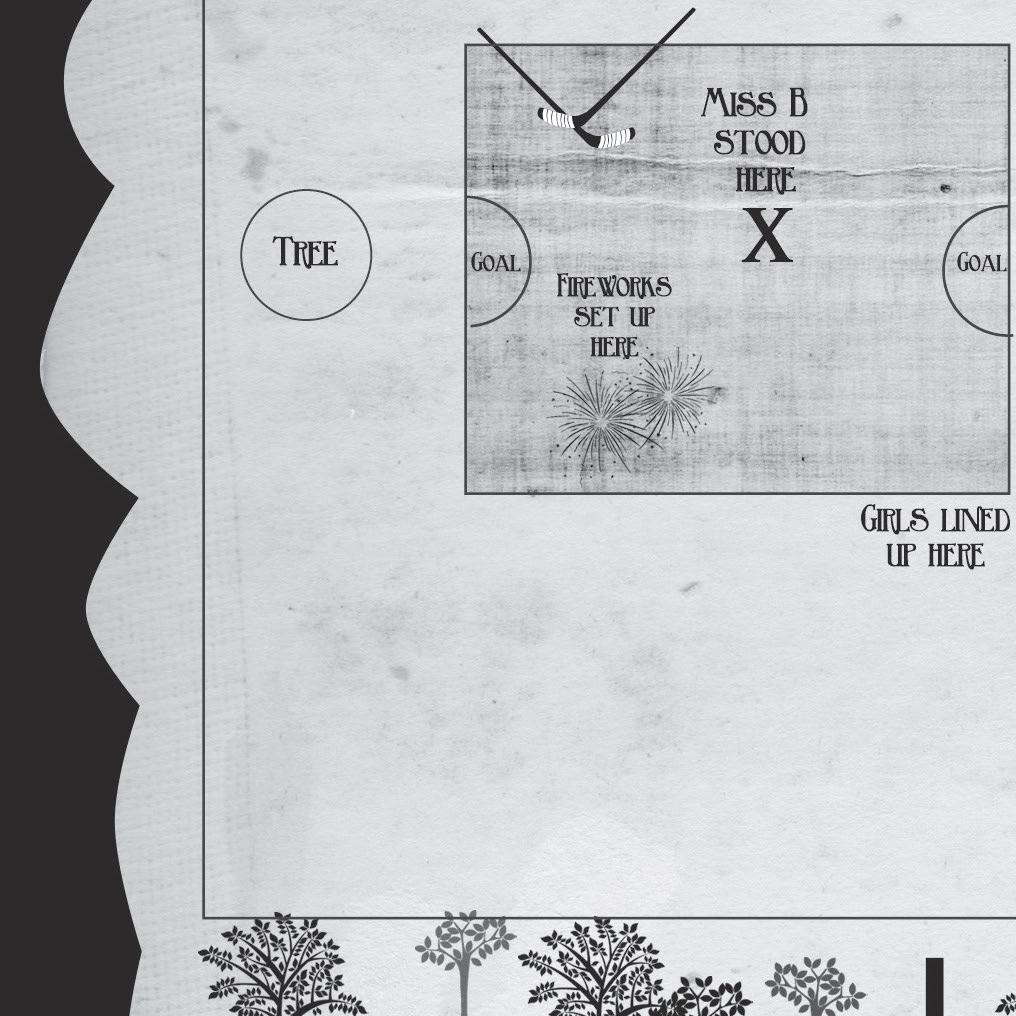

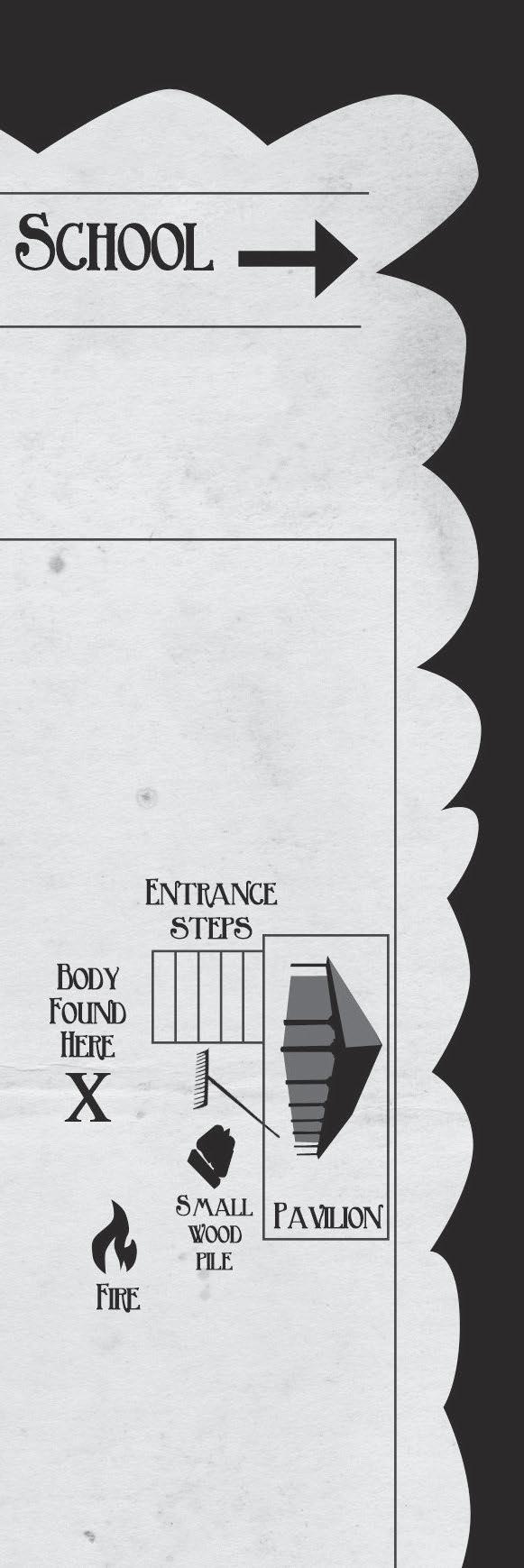

We milled about a bit, once we were on the field, jostling against other groups of girls from other years. We were supposed to be in form group sets, but of course that started to go wrong in the darkness and the excitement. Then Jones, Deepdean’s handyman, came forward with the Guy. As he tossed it onto the bonfire, which had been set up near the pavilion (though not too near), sparks flared out and it blazed up fiercely. Everyone surged towards it. All of us fourth formers were swept up in the confusion – I bumped against Lavinia and she said ‘Hey!’ but good-naturedly. Jones bellowed at us all indignantly to keep away. Only Elizabeth and the Five were allowed to go near the fire – Elizabeth was supervising the Five on bonfire duty. They were bringing armfuls of wood from the pile near the pavilion to throw onto the blaze. They worked in shifts, walking back and forward from the pavilion to make sure that the fire was never left untended.

My eyes were on the Guy, a hot dark shape at the middle of the blaze. Guys always give me an eerie shiver down the back of my neck, although I know that they are not real – they look so like a body that I cannot quite bear it. It makes me feel as though I am in the sort of

dream where something is wrong, and I am the only one to know it.

I was brought back to myself when Daisy nudged me and pointed. There was Margaret Dolliswood, a load of wood in her arms. She was not taking it to the fire, though, but standing by Elizabeth Hurst. She looked as though she wished she could have hurled the wood at her, but Elizabeth did not seem intimidated. Instead, she leaned forward, a swagger in her shoulders, as though she owned the sports field and everything in it. I could not see her face, or hear what she said, for we were too far away, but the fight went out of Margaret’s pose, and Elizabeth seemed to stand taller. Then Margaret turned, walked stiltedly over to the Big Girl Astrid Frith and snapped something at her. Astrid burst into tears, and Margaret spun round and stormed back to the bonfire. She hurled her armload onto the flames, and they flared up, with a crackle and burst of redness.

‘Now, what was that ?’ Daisy asked me, without turning round. ‘What did Margaret say to Astrid? And why?’

‘It was only Elizabeth making the Five be horrid, as usual,’ I said, not wanting to encourage her. ‘Look, it’s time to light the sparklers.’

Miss Runcible, Enid and Lettice were handing out sparklers. Miss Runcible gave one to me, looking as