11 Why Pakistan’s banks won’t finance the solar revolution

14 A quarter billion Pakistanis: a bigger demographic dividend

20 SNGP to install 300,000 LNG connections this year

22 Systems Ltd will acquire Confiz

24 Amoxil recall hits GSK Pakistan revenue in otherwise strong year

26 Jaecoo launch expected to significantly boost Nishat Group earnings

28 The Engro Succession: Smart continuity or a postcard to the past?

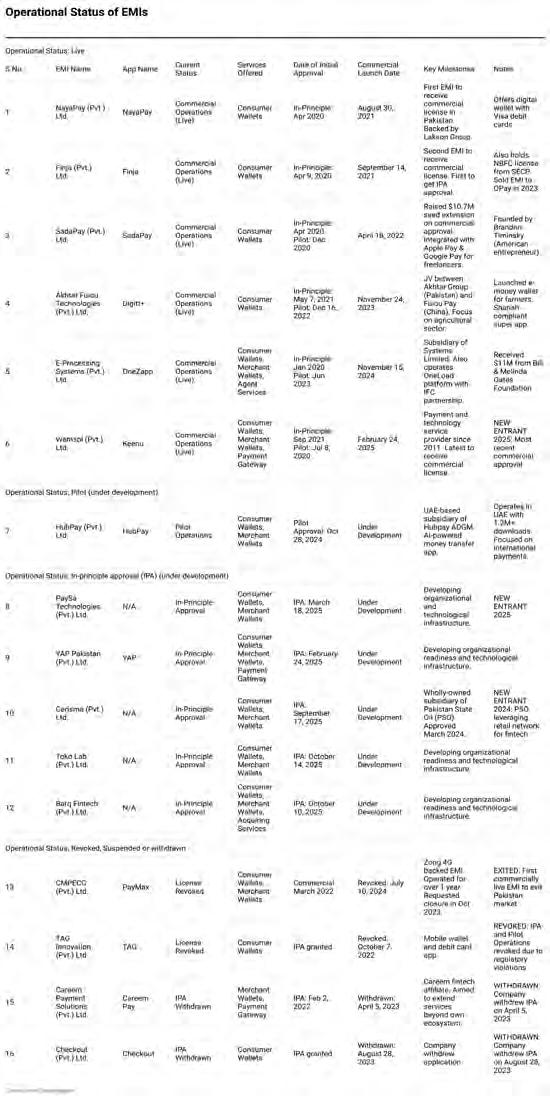

31 Mapping EMIs in Pakistan since 2020: 6 live, 4 face death and 6 at IPA or pilot

32 Agriculture at crossroads: Are we ready? Omar Javed Chohan

34 From cricket fandom to financial hustle — what Pakistan’s 2025 searches say about money, media and ambition

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Usama Liaqat Shahab Omer | Zain Naeem | Nisma Riaz | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Muddasir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) GM Special Projects Zulfiqar Butt - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Ahtasam Ahmad

Pakistan’s banking sector presents a striking paradox. With over $131 billion in deposits and gross advances of only $50 billion as of June 2025, the financial system sits on enormous pools of capital.

The recent surge in private sector credit, crossing Rs1.2 trillion in the first five months of fiscal year 2026 compared to just Rs41 billion in the same period last year, might suggest a credit boom is underway. Yet this apparent expansion masks a deeper structural malaise: the money flows primarily toward short-term working capital needs, particularly for rice crop processing and trading, rather than productive long-term investments.

Pakistan’s investment-to-GDP ratio plummeted to 13.1% in fiscal year 2024, marking the lowest level in over five decades. This represents not just a cyclical downturn but a fundamental breakdown in the country’s capacity to channel savings toward productive investment. While neighboring economies build infrastructure and expand manufacturing capacity, Pakistan’s banks increasingly park their funds in government securities, which now constitute close to two-thirds of total banking assets.

This preference for government paper

over private lending stems from multiple sources. Heavy budgetary borrowing by the government creates an attractive, risk-free asset class offering competitive yields. Banks can earn steady returns without the operational complexity of credit assessment, monitoring, and recovery that private sector lending demands.

A sub 40% advances-to-deposits ratio reveals how far below potential the banking system operates, even as deposits grow.

Within this constrained credit landscape, small and medium enterprises receive particularly short shrift, accounting for merely 6.4% of total private sector credit. Consumer lending fares marginally better at 8.7%, but these figures reveal a financial system that serves primarily large corporate borrowers while leaving vast segments of the economy dependent on informal finance or self-funding. This concentration reflects not capital shortage but institutional preferences deeply embedded in Pakistan’s banking culture.

The regulatory framework, while ostensibly designed to ensure financial stability, effectively reinforces this bias toward established borrowers. Prudential Regulations

mandate that all bank exposures be secured by collateral, with unsecured lending capped at Rs10 million per borrower. Banks interpret these requirements conservatively, accepting primarily liquid assets, property, and machinery with clear secondary markets as valid security. This creates an immediate barrier for sectors like distributed solar energy, where assets generate economic value through energy savings rather than resale potential.

The transition to IFRS 9 accounting standards has further complicated matters. The new Expected Credit Loss model requires banks to provision for potential losses from loan origination, factoring in forward-looking scenarios and sectoral conditions. For emerging sectors like renewable energy, lacking established performance history, this translates into conservative assumptions and higher provision requirements. Banks respond by applying risk premiums that make lending economically unviable or simply avoiding these segments altogether.

The residential and SME solar sector exemplifies how regulatory frameworks and banking practices combine to exclude potentially

The absence of enabling infrastructure compounds these challenges. Pakistan lacks comprehensive credit bureaus covering informal sector borrowers, standardized documentation for small-ticket loans, and efficient dispute resolution mechanisms for financial contracts. Each missing piece reinforces others, creating systemic barriers that individual institutions cannot overcome alone

Ummamah Shah, senior associate energy finance at Renewables First

profitable lending opportunities. Despite strong economic fundamentals, with solar systems offering payback periods of around 2 years and demonstrating significantly lower non-performing loan rates, banks remain reluctant to engage at scale. The core issue revolves around how financial institutions perceive and value solar assets as collateral.

“Solar loans have proven remarkably safe with low default rates, yet banks are still reluctant to lend. The problem isn’t the actual risk, it’s a confluence of regulatory constraints and lack of risk appetite. We are missing out on good business simply because our internal systems haven’t caught up with market realities,” said Naveen Ahmed, climate finance expert and former country transaction coordinator, PFAN.

Solar panels and associated equipment face multiple valuation challenges within traditional banking frameworks. Insurance companies apply aggressive annual depreciation rates to solar assets, settling claims at heavily reduced values that leave loans under-protected.

The absence of liquid secondary markets means banks cannot reliably estimate recovery values in default scenarios. Legal processes for asset repossession can stretch from eighteen months to fifteen years, making

enforcement essentially meaningless for small-ticket exposures. These factors combine to render solar equipment effectively worthless as collateral from a traditional banking perspective.

The enforcement challenge extends beyond simple repossession difficulties. Multi-tenant buildings and rental properties introduce ownership complexities that existing legal frameworks struggle to address. Without clear right-of-access provisions similar to those developed in India’s solar market, banks cannot confidently structure loans for rooftop installations where borrowers may not own the underlying property.

This excludes large urban populations who could benefit most from reduced electricity costs but lack formal property titles or live in shared accommodations.

Banks have developed workarounds that essentially negate the accessibility solar financing should provide. Some institutions now require double collateralization, demanding land or gold as additional security beyond the solar equipment itself.

This approach has enabled portfolios to maintain low default rates but defeats the purpose of making solar accessible to middle and lower-income segments. The very households and small businesses that would benefit

most from reduced energy costs find themselves excluded by collateral requirements they cannot meet.

Microfinance institutions have emerged as a key channel for small-ticket solar lending, specially for the agri sector. Leveraging their grassroots networks and alternative credit assessment methodologies. These institutions demonstrate that solar lending can work at scale; one major microfinance bank has a solar portfolio of around 10% of their lending book, with negligible non-performing loans.

Yet microfinance cannot solve the solar financing challenge alone. These institutions face their own constraints, primarily capital adequacy requirements that limit balance sheet expansion even when liquidity remains abundant. More critically, their lending rates are north of 35% for fully secured loans, making solar installations prohibitively expensive for many potential customers. While partial guarantee mechanisms could theoretically reduce rates to 20-22%, such support remains

The progression pathway from microfinance to commercial banking, where successful small borrowers graduate to mainstream financial services, has failed to materialize at meaningful scale. This leaves a missing middle segment: enterprises and households too large for microfinance but too small or informal for commercial banks

Shezad

Abdullah, banker & former PFAN advisor

Solar loans have proven remarkably safe with low default rates, yet banks are still reluctant to lend. The problem isn’t the actual risk, it’s a confluence of regulatory constraints and lack of risk appetite. We are missing out on good business simply because our internal systems haven’t caught up with market realities

Naveen Ahmed, climate finance expert and former country transaction coordinator, PFAN limited in scope and accessibility.

And even those who are scaling their distributed solar portfolio are compelled to do it with full collateralization in the form of gold or agri-passbook in order to not breach the capital adequacy requirements.

“The progression pathway from microfinance to commercial banking, where successful small borrowers graduate to mainstream financial services, has failed to materialize at meaningful scale. This leaves a missing middle segment: enterprises and households too large for microfinance but too small or informal for commercial banks,” remarks Shezad Abdullah, banker & former PFAN advisor.

These potential borrowers remain trapped between two financial worlds, unable to access appropriate credit despite demonstrable repayment capacity.

The challenges facing solar and SME finance reflect deeper structural issues within Pakistan’s financial ecosystem. Despite regulatory mandates requiring banks to maintain Internal Credit Risk Rating Systems aligned with Basel guidelines, most institutions treat these frameworks as compliance exercises rather than decision tools.

Credit officers continue relying on collateral coverage and borrower relationships over cash-flow projections or probability-of-default metrics. Historical performance data that could calibrate risk models remains unused, perpetuating conservative lending practices inherited from previous banking crises.

Ummamah Shah, senior associate energy finance at Renewables First, “The absence of enabling infrastructure compounds challenges. Pakistan lacks comprehensive credit bureaus covering informal sector borrowers, standardized documentation for small-ticket loans, and efficient dispute resolution mechanisms for financial contracts. Each missing piece reinforces others, creating systemic barriers that individual institutions cannot overcome alone.”

Banks respond rationally to this environment by concentrating on familiar, lower-risk segments where existing systems function adequately.

Cultural and behavioral factors within banking institutions further entrench the status quo. Branch-level credit officers lack discretion to innovate beyond rigid policy templates, while credit committees prioritize portfolio protection over growth into new segments.

The prevailing risk culture, shaped by past experiences with non-performing loans and weak legal recourse, creates institutional memories that resist change even when market conditions improve. Success is measured by avoiding losses rather than capturing opportunities, leading to systematic under-lending relative to economic potential.

Breaking this deadlock requires coordinated action across multiple fronts. Regulatory frameworks need updating to recognize cash-flow-based lending and performance-linked structures that align with renewable energy economics. Legal reforms enabling faster dispute resolution and asset recovery would reduce risk premiums across all lending segments. Standardized documentation and credit scoring models specifically designed for solar and SME lending could reduce transaction costs and improve risk assessment.

Financial innovation offers particular promise. Lease-based structures that avoid ownership transfer until full payment could circumvent collateral enforcement challenges. Embedded finance models integrating repayment with utility bills or digital payment systems would improve collection rates while reducing administrative costs.

Securitization of performing solar portfolios could create tradable instruments attracting institutional investors, transforming solar finance from a niche development product into a mainstream asset class.

Technology-enabled solutions present immediate opportunities. Smart inverters allowing remote disconnection in default scenarios provide technical enforcement mechanisms without legal proceedings.

Digital credit scoring using alternative data, utility payment history, mobile money transactions, business revenues, could extend credit access to currently excluded segments. Aggregation platforms connecting multiple small borrowers with institutional capital could achieve economies of scale while maintaining local relationships.

The residential and SME solar financing gap represents more than a missed business opportunity. It symbolizes broader failures in Pakistan’s financial architecture, the inability to channel abundant savings toward productive investment, the exclusion of dynamic economic segments from formal finance, and the perpetuation of inequality through restrictive credit practices.

With solar technology costs declining and energy prices rising, the economic case for distributed renewable energy has never been stronger. The financial system’s inability to support this transition reflects not market failure but institutional failure—a fixable problem requiring political will, regulatory innovation, and cultural change within banking institutions.

As Pakistan grapples with chronic energy shortages, climate vulnerabilities, and economic stagnation, unlocking solar finance for households and SMEs offers a rare opportunity to address multiple challenges simultaneously.

The question is not whether the financial system can afford to support this transition, but whether the country can afford continued inaction. With billions in deposits seeking productive deployment and millions of households seeking affordable energy solutions, the ingredients for transformation exist.

What remains missing is the institutional courage to bridge the gap between capital abundance and investment scarcity, to transform Pakistan’s credit paradox into an engine for sustainable growth. n

By Farooq Tirmizi

The government did not make a formal announcement of this, but based on trends in our population growth, in the calendar year 2025, the population of Pakistan has very likely crossed 250 million. A quarter billion human beings are citizens of our republic. This is a milestone worth marking in its own right because scale has a logic of its own. While we are still a poor country on a per capita basis, adding more human beings has effects worth understanding in full.

Predictably, a section of the press and commentariat has viewed the population as something of a millstone, and there appears to have been some recently produced think tanks reports pointing to all the ways Pakistan’s population is a problem.

That view is mistaken, and based on a very static and backward looking examination of Pakistan’s demographic data. If one examines not just where Pakistan is, or has been, but tries to project out where the country is going, a very, very different picture emerges.

In this story, we will attempt something slightly ambitious: using differential calculus concepts to explain why Pakistan’s population is no longer a problem. We will then place Pakistan’s current position in a wider global context as one of the handful of large countries in the world – and the only large country outside sub-Saharan Africa –that is not on track to experience population collapse within this century.

This, then, has implications for the government of Pakistan’s policies on population welfare. Specifically, the government needs to stop spending money on encouraging contraception.

Before diving into all of that, let us take stock of where Pakistan currently stands and where it has been over the course of its existence. The country has very likely crossed 250 million in total population this year, and there is a chance that it may even has crossed that level some time last year.

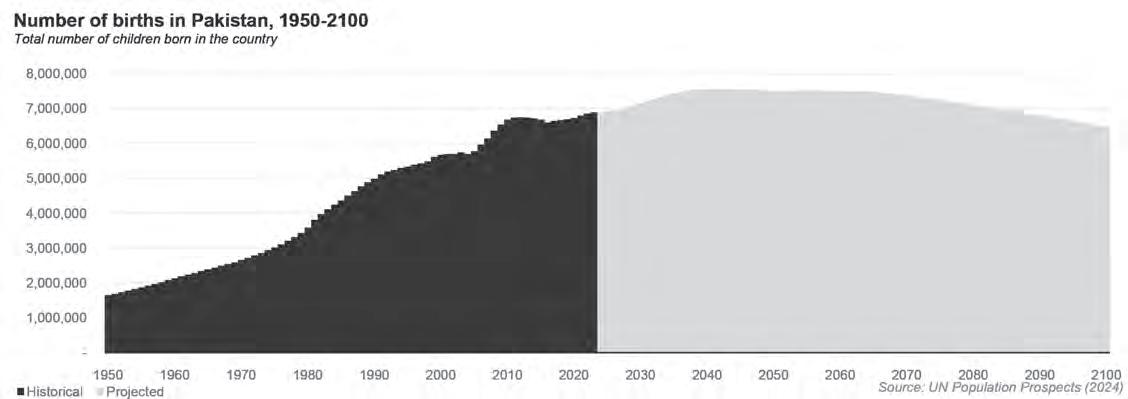

About 6.9 million babies will be born in Pakistan this year, and approximately 1.6 million people will die, which means the natural increase in population is about 5.3 million people. The average Pakistani woman is expected to have about 3.2 children over the course of her lifetime.

These data points are what seem to be causing some alarm in the English-language press in the country, and some publications outside of it. This growth rate in the population is deemed to be “unsustainable” and seen as a continuation of the kind of problems you may have studied about in your Pakistan Studies textbook in school, no matter how long ago you were in school.

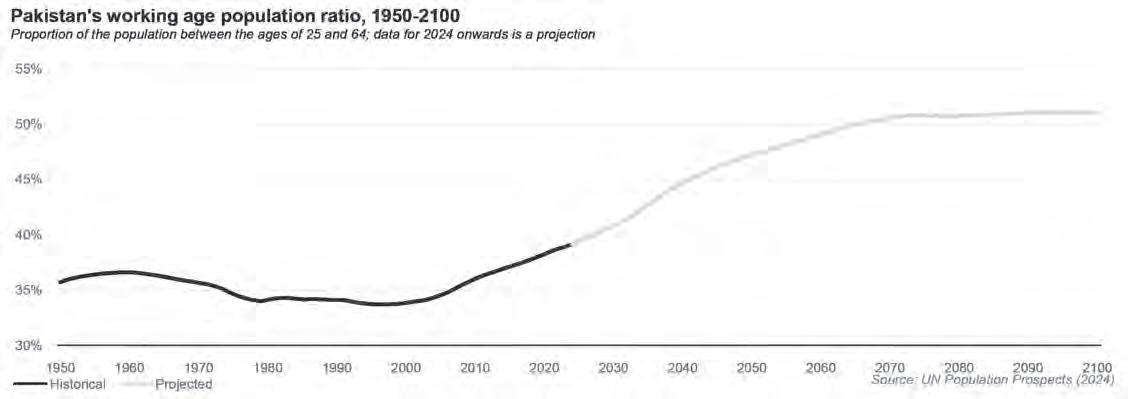

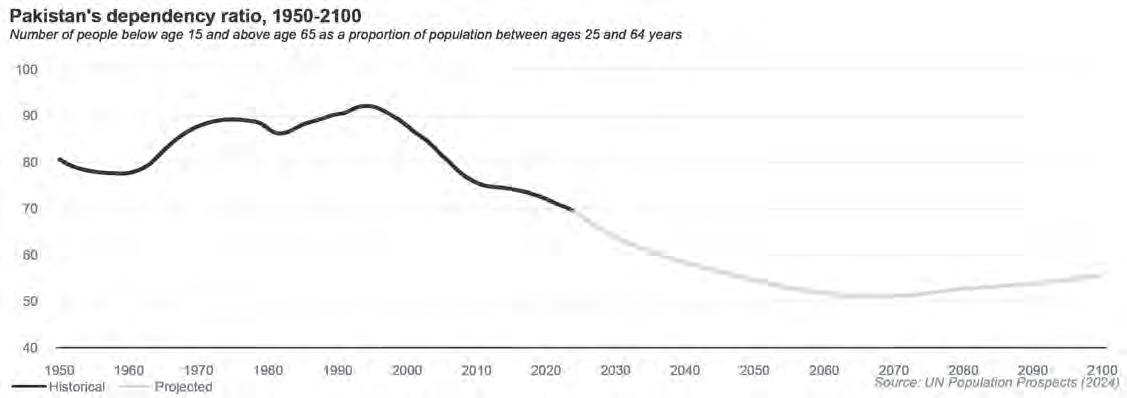

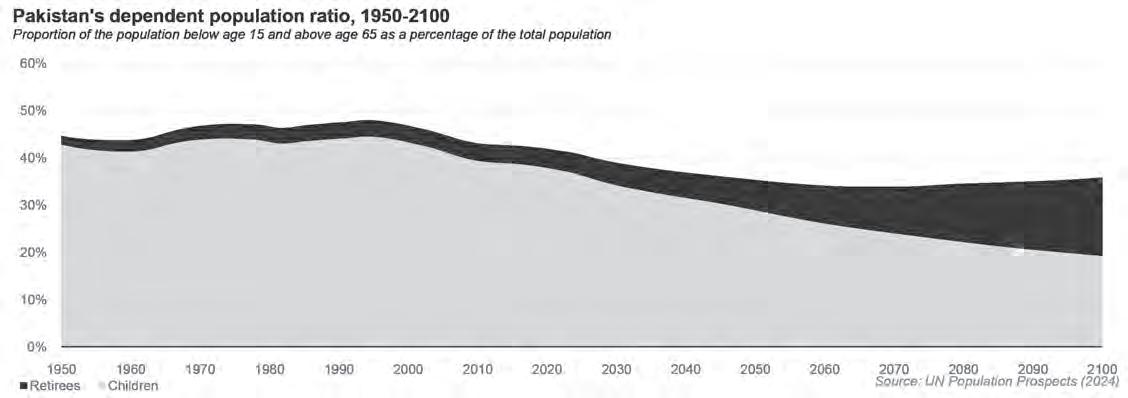

The evolution of one single data point may illustrate why this is not true. For the first 50 years of the country’s existence, Pakistan’s working age population ratio – the proportion of the population that is of prime working age between 25 and 64 – was either stagnant or actually falling, meaning every worker had either the same (high) number of mouths to feed, or even more.

Since 1997, the working age population ratio has been rising every single year and is currently a full six percentage points higher than it was in 1997.

This is a very important point to understand. The characteristics of Pakistan’s population increase for the first 50 years and in the subsequent 28 years is very different. In

the first 50 years, the number of children was rising faster than the number of adults entering the workforce to earn the money to feed them. In the 28 years since then, the number of adults who can earn a living has been rising faster than the number of children being born in the country.

This is the statement of fact that needs to be repeated in several ways: yes, Pakistan’s population is growing, but it is doing so by adding more workers than dependents, and so it is increasing its earning capacity faster than it is increasing its dependent population.

And as we have previously reported in our stories on Pakistani education and the Pakistani workforce, the country’s workforce is becoming literate enough (youth literacy close to 90% in most urban areas) to be sufficient for at least the first phase of industrialization, and the Pakistani economy is increasingly creating a larger number of more stable, salaried jobs than at any point in his history (45% of all new jobs created over the past 15 years have been fixed monthly salary jobs).

So the marginal increase in population is from a Pakistani who is entering the workforce, more likely to be literate than not, and increasingly likely to have a stable salaried job. This is the demographic dividend phase of our population growth, which means this is the time when population growth adds to economic growth and does not cause a drag on it.

To look simply at the headline growth numbers and start talking about “the problem with population growth” like it is still the 1990s is incomplete analysis at best.

The most important fact to understand about demographic change is that it can move very slowly for centuries, and then very suddenly

move in one direction. And as we have recently seen from most of the world, populations that have been increasing for centuries can start declining very rapidly.

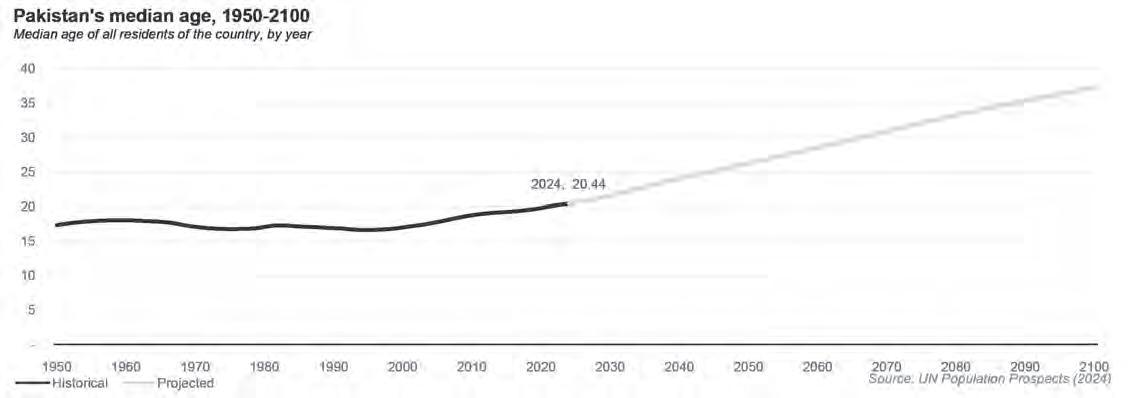

The second most important fact to understand about demographic change is that because it is slow-moving, it is also possible to make very accurate projections for several decades out. It is possible to reasonably estimate how many working age people the economy will have 30 years from now by looking at how many babies were born this year, and then making adjustments for mortality.

And the third critical fact to understand is the demographic habits – that is, the decisions people make about family size –can take at least a generation to change.

All of this is a long way of saying it is now time to talk about differential calculus, because that is the mathematical tool we use to understand rates of change, which in turn will help us see how patterns are shifting, and perhaps allow us to predict what will happen to the country’s demographics over the course of this century.

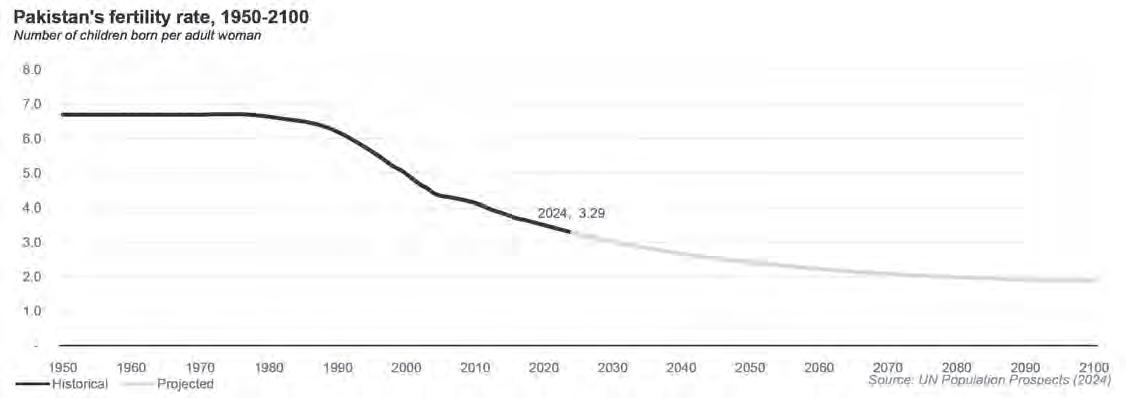

The simplest measure of change in population is its annual growth rate. But that only tells you what is happening this year. To understand it at a deeper level, one needs to understand the total fertility rate (TFR), which is a measure of the average number of children an adult woman will have in her lifetime, given the rate at which children are being born in the country in a given year.

What we want to do is go one step further, and examine not just how TFR has changed over the past few decades, but also examine the rates at which it has changed (dy / dx) as well as the rate at which the rates of TFR have changed (d2y / dx2). We shall put this as plainly as possible.

Let us start with the current rate, which we at Profit calculate at around 3.16 children per woman. Our measure is the average TFR for Pakistan measured by three separate entities: the United Nations, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington in Seattle, and the Swedish research foundation Gapminder.

Now let us take a look at how this number has changed over time. Prior to

the 1970s, this number hovered around 6.7 children per woman for much of the past century. It was not until 1992 that it went below 6.0 children per woman for the very first time.

From that point, the pace of change was somewhat rapid, going down from 6 to 5 children per woman by 1999, just 7 years to change the average by one full child. The next drop was somewhat longer. TFR dropped to 4 children per woman in 2011, so taking about 12 years to go down by one more child. This next drop is taking somewhat longer still and expected to happen sometime in 2028, or about 17 more years to go down one more child.

In other words, we made a very rapid climb down from 6 to 5 and 5 to 4, and are currently in the process of making a slightly slower, but still steady climb down to 3 children per woman. This suggests that Pakistani households are converging on what they consider to be a manageable family size, which is between 2 and 3 children per household. By no stretch of the imagination is that too many children.

In short, if you look at how people are making decisions right now, and have in the past few years, the average Pakistani family is no longer having too many children. But this is a fact that you would not be able to guess simply by looking at the population growth rate, or even the static TFR number. The TFR in Pakistan is changing, and declining at steady pace. And thankfully for our country, it appears to be headed towards a manageable number: not too high, and hopefully not too low either.

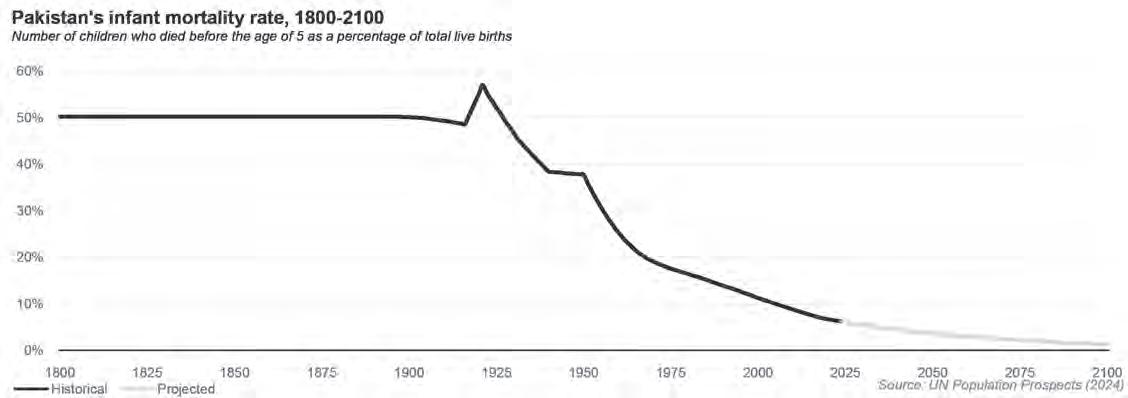

But also consider the fact that it took a long time to get people to start changing their habits. This is best understood by examining why people had 6 or 7 children on average to begin with, a picture that emerges once you understand the historical link between fertility and infant mortality.

We gathered data on infant mortality in what is now Pakistan from the year 1800 through the present day to the year 2100 (yes, 300 years of data). For most of that time, the probability of a child dying before turning five years old was greater than 50%.

People in the 1930s through the 1980s did not have 6 children because that is how many they wanted. They had 6 children because they were taught that is how many you have by people who used to have 6 children because they knew that, in their day, only about 3 would survive.

Indeed, infant mortality was higher than 50% in the region that is now Pakistan until 1927, and did not go below 30% until 1956. My father’s generation, in other words, could expect one out of every three siblings to be dead before the age of 5, and were operating under cultural assumptions formed even earlier, when every second sibling would not live beyond their fifth birthday. The infant mortality rate did not go below 10% until 2006 and is still above 6% today. In developed countries, it is usually well below 1%.

We now know that it takes about 2-3 generations for data about family sizes to take effect among a population. Now that this information has trickled through – that you do not need to have so many children because nearly all of them will survive –people in Pakistan are choosing to have fewer children.

Now, take the above set of facts about how long it takes people to change their habits about fertility, and layer on top of it the understanding that they are currently in the process of already lowering their family size preferences down toward what will hopefully be a stable point between 2 and 3 children.

Do you think the government needs to continue encouraging people to have fewer children, or has the message been received?

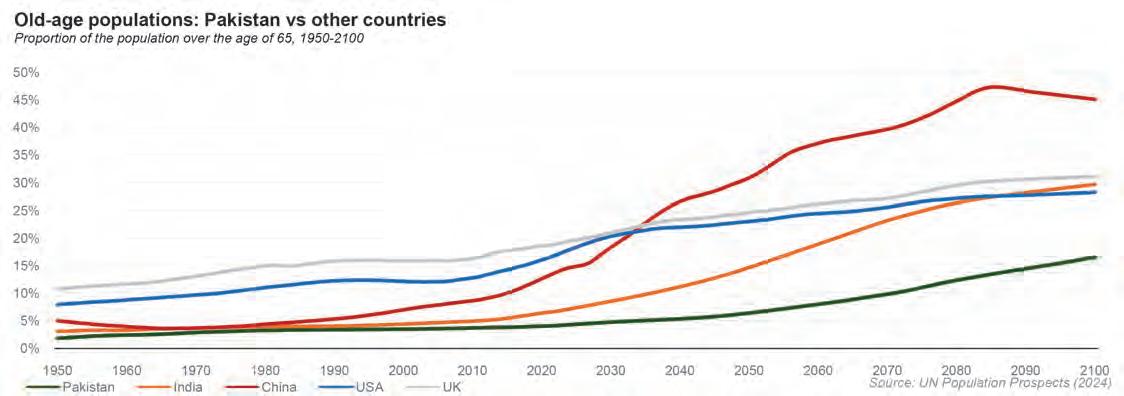

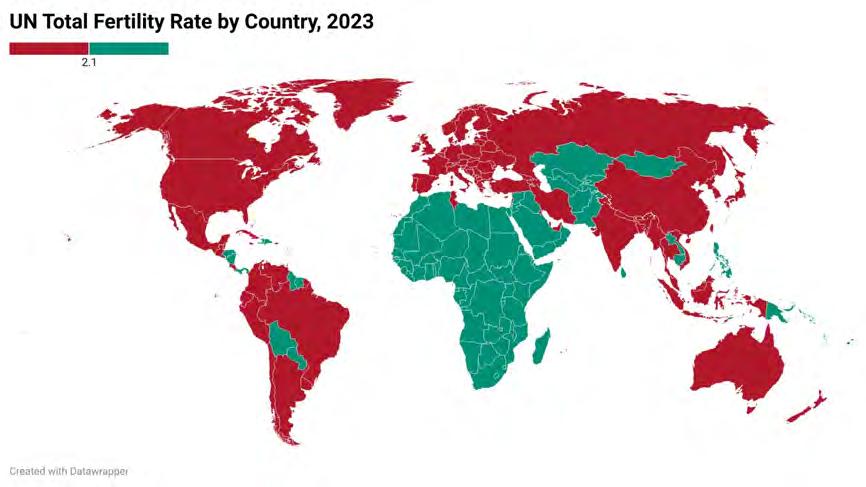

We think it is clear that the message has been received by the population. You could argue that there is no harm in the government continuing to provide education and resources to people towards this outcome that has been a success in getting people to reduce their total family sizes. But that is where it is helpful to understand the global context of population dynamics, specifically the coming population collapse in large parts of the world.

Here is a statistics we suspect most Pakistanis do not know: in 2022, the total number of children born in Pakistan (6.8 million) was greater than the total number of children born in all of Europe (6.5 million), the first year Pakistan had more children than the entire continent of Europe.

Pakistanis are not having too many children. Europeans are having too few.

This is a concept that is very difficult to understand for most Pakistanis. Most of you reading this in Pakistan have grown up with siblings, and probably had very regular contact with your first cousins, including probably having lived at least part of your childhood in the same house as them. You can probably name most, if not all, of your second cousins. The total number of siblings, cousins, and second cousins is probably close to 100 or exceeding it for most of you.

For most people, all of their first cousins are descended from four people, and all of their second cousins are descended from eight people. So, if the total number of siblings, first and second cousins combined is 100 (very common in most Pakistani families today), those 8 people have 100 great grandchildren. Keep that number in mind.

At the current birthrate in South Korea, 100 South Koreans today will have a total of 6 great-grandchildren between all of them combined.

The exact reverse of the way Pakistanis live today.

Nearly the whole world – including large countries like India and China – have too few children to replace the current generation of young people when they grow old, which means these societies will continue to just get older and older for the foreseeable future.

The only large country (more than 50 million people) outside sub-Saharan Africa that is currently not suffering from this terminal lack of children is Pakistan. All other countries are in a belt within sub-Saharan Africa.

We are it.

We are the only people in the world who continue to have children at historically normal rates, and have families that consist of siblings, first cousins, and second cousins, and have large family gatherings where we have a next generation to pass down our traditions and way of life to.

The rest of the world is slowly committing suicide. It is all fun and games at first (and that is the stage India is at right now). The young people start growing up and entering the workforce and earning money have few, or zero, children to spend it on, so they save, and spend on luxurious lives that push up the standard of living, and within a generation, you see a city that was barely more than a village turn into the kind of magnificent metropolis that is Shanghai and Shenzhen (and soon will be Mumbai and Bengaluru). Publications like The Economist start doing cover stories about you (China in the 1990s, India in the 2000s, Poland today).

But then, as there are fewer young people, you start noticing some things. Fewer applicants for entry level jobs, and the people who do take those jobs are not as eager to learn and get ahead (because they know they have less

competition). Fairly soon, this starts translating into fewer new customers and slower growth for any industry that does not cater to the elderly. (Hospitals and healthcare usually start booming around this time.) This is the part of the cycle China is at right now.

Then you become Japan or South Korea. The youth start to vanish to the point where society literally forgets what it is like to have children around. The few people who do have children go around apologizing to their neighbours for the noise their children make, the kind of happy sounds that are normal on Pakistani streets.

All of society is waiting to die. Nobody has children or grandchildren in whose future they feel invested.

It is a dark, depressing, and often lonely wait for death, except that it takes place at a society-wide scale, so it is not interspersed with other people starting off lives and getting married and giving birth or sending their children off to school. There are towns in South Korea where the last birth was recorded in 1988.

If we keep encouraging people to have fewer children, that could be us.

For reasons we do not fully understand yet, Pakistanis have not yet seemed to follow other countries – including our neighbours India and Iran – down that depressing road yet. As we get closer to the point of 2.1 children per woman – the replacement rate TFR – we seem to be slowing down our descent, and may even stabilize above that point, which would be a very happy outcome. Why would we want to risk overshooting that balanced point and arrive at the nightmare that many countries on our continent are facing?

Pakistani families are already deciding to have two, three, or four children, on average. Those are reasonable numbers. Let them have those families. There is no longer a need for the government to encourage more contraception, or to keep harping about having fewer children. These policies were conceived at a time when it was not considered possible that the world might start running out of children, and too many children was the norm, so the

message was never modulated to encourage people to have manageable family sizes. In most other countries in the world – including large Muslim majority countries like Iran, Indonesia, and Bangladesh – this messaging has resulted in a slowdown in childbearing that has overshot the goal of stable population size.

We should learn from the mistakes of those countries, and avoid the same fate. The Population Welfare Department in each provincial government, which tends to be focused on contraception, needs to be redirected towards lowering the still-too-high maternal and infant mortality rates.

On contraception, the government should declare “mission accomplished” and move on.

As for the population growth projections, the next time someone tells you that Pakistan’s population will exceed 500 million by the year 2100, we hope you will no longer look at that as something to be concerned about, and perhaps even something to celebrate.

Then smile, and go hug your children, nephews, and nieces. Because you will still have them, and too many people in the rest of the world do not. n

Sui Northern Gas Pipelines (SNGP) is positioning re-gasified liquefied natural gas (RLNG) as a mass-market product for households, with management telling analysts it plans to install 300,000 RLNG connections in FY25, and then 600,000 connections annually in the years that follow. The scale is notable in a sector where new domestic gas connections were long constrained by shortages and policy bans; in effect, RLNG connections are being pitched as the workaround that lets the network keep expanding even as indigenous gas availability shrinks.

The early demand signal has been strong. Management said 50,000 RLNG connections were provided within 1.5–2 months, a pace that suggests latent demand from households that either remained unserved or were forced into costlier alternatives. The pitch is as much about economics as convenience: SNGP argued the average cost of RLNG is 30% lower than LPG, while also being “more convenient and safer”.

SNGP’s evolving RLNG proposition is also arriving at a moment when Pakistan’s gas system is being forced to adapt in multiple di-

rections at once. Management said two RLNG cargoes will be diverted monthly, while it expects an improvement in forced curtailment from local E&P fields. The subtext: the system is oscillating between shortage management and surplus management – sometimes in the same year – because demand, supply, and contracted LNG volumes do not move in lockstep.

Pakistan’s LNG story is now a decade old, and it was born from depletion anxiety. Domestic gas production peaked in the early 2010s and began declining thereafter, while proven reserves also fell in the absence of major new discoveries, widening the demand–supply gap. A separate assessment of Pakistan’s “shift from domestically produced gas to LNG” similarly notes domestic production and proved reserves have been declining, accelerating the move towards imported LNG.

The infrastructure followed quickly. The Engro Elengy Terminal at Port Qasim, widely described as Pakistan’s first LNG import facility, has been operating since 2015. Engro’s own release on the terminal notes it began operations in March 2015, delivering regasified gas into the network. A second floating terminal at Port Qasim – associated with Pakistan

GasPort – was inaugurated in 2017, expanding the country’s ability to bring LNG into the system.

The long-term contracting architecture was put in place in parallel. Qatar’s national LNG supplier (then Qatargas) signed a longterm agreement with Pakistan State Oil for 3.75 million tonnes per annum for 15 years, with the first cargo expected in March 2016. Over time, LNG moved from “stop-gap” to “structural”, and the share of imported gas in total supply has been on a rising trajectory as domestic production declines.

But the LNG era has also created new kinds of volatility. Reuters has reported that Pakistan has at times faced an LNG surplus because domestic demand – particularly from gas-fired power plants – fell sharply for several years through 2024, as cheaper alternatives (notably solar) displaced gas generation. In late 2025, Reuters further reported Pakistan agreed to cancel a large number of LNG cargoes scheduled for 2026–27, with most cancellations requested by SNGPL, reflecting how distributor demand can drive national import decisions.

This demand compression links directly

back to SNGP’s own operating metrics. Management told analysts that overall unaccounted-for-gas (UFG) rose partly because gas input by the power sector and captive power plants fell by 65 BCF, changing system dynamics. In plain terms: when large, steady off-takers step back, the economics of the pipeline network – and the accounting of losses – start to look worse, even if operational leakage or theft has not suddenly exploded.

That is why RLNG household connections matter strategically. They represent an attempt to “re-home” volumes: shifting reliance away from a shrinking domestic gas pie and away from power sector demand that has become more cyclical, towards a household base that is politically important and, in many areas, still under-served.

If imported gas was the defining supply-side shift of the last decade, circular debt has been the defining balance-sheet constraint.

At SNGP’s briefing, management explicitly linked shareholder payouts to the circular debt situation, saying payouts have decreased temporarily, but should improve once circular debt is resolved – and that KPMG has been hired as a consultant as “serious efforts” are made. This mirrors wider reporting that Pakistan’s gas-sector circular debt sits in the trillions of rupees and requires a formal management plan to unwind without repeatedly shocking consumers with tariff spikes.

One key reason circular debt is so hard to tame is that gas utilities operate a regulated cost-recovery model while facing delayed payments, politically constrained tariffs, and uneven enforcement – especially in highloss areas. The most visible manifestation of that friction is UFG, which blends physical leakage, measurement issues, and theft into a single headline number.

At the briefing, management said the distribution benchmark for UFG is 6.25%, and that OGRA uses key monitoring indicators (KMIs) – 31 factors including theft and leakage – to determine what portion of losses is allowed. A Petroleum Division document describing OGRA’s approach similarly notes OGRA undertook a benchmark study and incorporates a performance factor via KMIs; UFG above benchmark is treated as a disallowance and deducted from utility revenue.

SNGP’s own recent UFG trend illustrates how quickly these numbers become politicised. Management said overall UFG increased to 5.27% in FY25 from 4.93% in FY24, but argued the increase was primarily due to lower gas input and sales to power and captive plants; without that sales reduction, it claimed UFG would have been 4.73%. It also highlighted that UFG volume was broadly flat (30,026 MMCF in FY25 vs 31,319 MMCF in FY24), suggesting the percentage rise reflects

denominator effects as much as deteriorating field controls.

Meanwhile, the company is trying to demonstrate enforcement credibility on theft. Public reporting over the last year has repeatedly described SNGPL disconnecting illegal connections and imposing fines as part of anti-theft drives. Whether these actions are large enough to materially shift UFG in highloss zones is a longer-term question, but the direction of travel is clear: as imported LNG makes every unit of gas more expensive, the tolerance for losses – commercial or physical – shrinks.

Circular debt also shows up in the mechanics of RLNG cost recovery. Management noted OGRA’s latest decision on REER allows 75% of working-capital finance costs for RLNG, compared to 50% previously; it said OGRA approved almost all costs in the last FRR except Rs2 billion, and expressed confidence this will be fully allowed in the next year’s FRR. For investors, those seemingly technical lines matter: the more predictable the cost pass-through, the less likely RLNG becomes a working-capital trap that deepens payables down the chain.

SNGP’s RLNG connection drive is happening alongside big-ticket pipeline investments designed to stabilise supply and improve network performance.

Management described a “mega project” to inject 45 MMCFD of gas from the Palak gas project, with estimated capex of Rs28 billion. It also cited an augmentation of the network in Rawalpindi and Islamabad with a cost of Rs27 billion. Those projects highlight the dual-track strategy: (1) squeeze more utility out of domestic upstream projects where possible, and (2) strengthen distribution networks in high-demand urban corridors where pressure issues become politically sensitive during winter peaks.

Publicly available material from SNGPL’s own annual reporting also points to network optimisation and augmentation work in recent years, including projects in major load centres and ongoing work in the Islamabad/Rawalpindi corridor aimed at addressing low pressure and enhancing operational performance. In a system where end-user anger often focuses on “low pressure” as much as “load shedding”, these network investments can be as reputationally important as they are financially material.

At the same time, the Palak injection project reflects a broader national priority: reduce the LNG import bill by bringing any incremental domestic supply online, even if the volumes are modest relative to national demand. That logic is echoed in ongoing public discussion about unconventional gas and tighter E&P activity, as policymakers try

to claw back some energy sovereignty while managing the fiscal costs of long-term LNG commitments.

SNGPL is Pakistan’s largest integrated gas utility, serving more than 7.30 million consumers across Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Azad Jammu & Kashmir through a large transmission and distribution network. It was established in 1963, is listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange, and is engaged in the purchase, transmission, distribution and supply of natural gas.

Yet the “integrated utility” identity is being stress-tested. Historically, SNGP was predominantly a distributor of domestic system gas. Now, it increasingly operates as a balancing entity for an imported RLNG system whose costs, contract terms, and demand swings can be difficult to manage – particularly when power sector demand falls away.

The financial performance shared at the briefing reflects that complexity. Management said profitability decreased to Rs14.6 billion (EPS Rs23.01) in FY25 from Rs19.0 billion (EPS Rs29.92) in FY24, attributing the decline mainly to a reduction in return on assets as the regulated return fell from 26.22% to 21.25% following lower interest rates. In other words, even when operational execution improves, regulated utilities remain exposed to macro variables – particularly interest rate assumptions embedded in the return framework.

On regulation, management also addressed investor anxieties around the asset-based model, saying OGRA has been working on revising the rate of return, but that it expects no change to the fixed-based regime and believes it will continue. That reassurance matters because the investment case for gas utilities often hinges less on “growth” in the conventional sense and more on the stability and transparency of the regulatory compact.

The RLNG connections plan is therefore best understood as a strategic adaptation: a way to keep the business expanding in customer terms, while the underlying fuel mix shifts. If SNGP can scale RLNG domestic connections as promised – 300,000 this year and 600,000 a year thereafter – it not only builds a new demand pillar, but also strengthens its negotiating position in a gas market where LNG cargoes, diversion decisions, and power-sector off-take can swing the system from shortage to surplus.

Ultimately, SNGP’s next chapter may be defined by how well it turns that pivot into something operationally durable: expanding the customer base without inflating receivables, managing UFG in a higher-cost gas world, and pushing capex that improves pressure and reliability – while Pakistan’s energy transition steadily erodes the “must-run” status gas once enjoyed in the power mix. n

The listed tech giant is acquiring a domestic competitor with a product portfolio focused on Microsoft services and

Systems Ltd (PSX: SYS), Pakistan’s largest listed technology and IT services exporter, has approved the acquisition of Confiz Pakistan (Pvt) Ltd in a transaction that will be executed through a court-sanctioned merger rather than a straightforward cash purchase.

In a notice to the Pakistan Stock Exchange dated 11 December 2025, Systems said its board – via resolutions passed through circulation on 10 December – had “considered and approved” the acquisition of Confiz Pakistan (Pvt) Ltd and “all its direct and indirect shareholdings in the Confiz Group of Companies” by way of an “amalgamation / merger” of Confiz “with and into” Systems.

Confiz, meanwhile, has also publicly confirmed that a definitive agreement has been signed. In a 11 December 2025 announcement published on its website, Confiz said it had entered into a definitive agreement to be acquired by Systems Ltd, describing Systems as “the region’s largest global IT services and consulting” organisation, and noting that the acquisition remains subject to customary regulatory and corporate approvals. Confiz framed the deal as a “strategic global expansion” move, and said it would continue operating as an independent business unit supported by talent hubs across multiple regions, adding that the combined entity will operate in “13+ countries”.

While the public disclosures so far do not provide a valuation or a timeline, the structure signals an important point: Systems appears to be using its listed equity as acquisition currency to consolidate capabilities in a fast-evolving market where scale, specialised skills (especially in cloud and AI), and access to premium enterprise clients increasingly determine who wins the next generation of contracts.

Systems Ltd occupies a unique position in Pakistan’s capital markets: it is one of the few large, globally oriented technology companies on the PSX, and it has steadily expanded from a domestic software house into a multi-region services exporter spanning consulting, engineering, and business process services.

On its investor-facing company profile, Systems traces its corporate licensing to 1977–78 and positions itself as “the country’s first Information Technology company” providing business solutions and business process outsourcing (BPO), also describing itself as Pakistan’s largest software exporter. The company says it has delivered “48+ years” of sustainable, profitable growth and employs “over 9000+ client-focused employees globally”.

One of the more distinctive features of Systems’ ownership story is the emphasis on employee ownership. The company profile notes that Systems was meant to be an employee-owned enterprise and says that leaders and top-performing employees, past and present, own 84% of the company’s stock. That matters because, in services businesses where talent retention and delivery quality directly affect revenue, ownership alignment is often framed as a competitive advantage – not just a governance curiosity.

In terms of what it actually sells, Systems presents itself as a full-spectrum technology services organisation. Its corporate profile describes proven expertise in deploying and supporting ERP, mobile, BPM, turnkey and complex software solutions. The company’s services menu spans digital consulting and strategy, digital commerce and business applications, plus a sizeable data and analytics stack that includes data modernisation, advanced analytics, data management and generative AI offerings. It also lists cloud operations and migration, cloud application development and integration, managed services, digital infrastructure services, security and emerging technologies.

Beyond “build and transform” work, Systems also offers business process services – an increasingly important part of the export story for Pakistani tech firms because it provides recurring revenues and deeper client relationships. Systems’ disclosed offerings include BPO, contact centre services, digital marketing, finance and accounting outsourcing, staff augmentation and legal process outsourcing.

Third-party ecosystem alignment is another pillar. Systems publicly lists alliances with major global platforms including Micro-

soft, Temenos, IBM, AWS, SAP and Salesforce. Microsoft, in particular, features prominently across Systems’ positioning: a Microsoft partner case study describes Systems as “well diversified” across BPO, omnichannel contact centres, data integration, application development, and cloud and digital services around the world. Microsoft also notes Systems has been a Microsoft partner since 2012 and highlights multiple competencies across cloud, data analytics, DevOps and ERP, among others.

This breadth is important context for the Confiz deal. Systems is not buying a company to “enter IT services” so much as to add depth in specific, commercially valuable capability clusters – particularly Microsoft business applications and AI-driven enterprise transformation, where demand is expanding rapidly.

Confiz is smaller than Systems but has built a clear identity in a particular corner of the enterprise technology stack – one that is especially relevant as corporations shift from bespoke systems to platform-led transformation.

On its website, Confiz describes itself as a global technology services company that has been helping businesses “build, evolve & scale since 2005”. It says it serves clients ranging from SMEs to Fortune 100 firms, with particular emphasis on retail, consumer packaged goods (CPG) and related sectors. Confiz also highlights its partner ecosystem, stating it is recognised as a trusted Google Cloud and Microsoft Solutions Partner.

What stands out most in Confiz’s service catalogue is the concentration around Microsoft’s enterprise stack – exactly the capability set that many Pakistani IT exporters want to deepen as global clients standardise on a smaller number of strategic platforms.

Confiz lists Microsoft Dynamics 365 (including customer engagement and finance & operations), managed services, implementation, upgrades and Copilot-related work as a core part of its offering. Alongside that, it emphasises data and AI services – ranging from data platform modernisation and analytics to “enterprise AI” – as well as cloud services, consulting and migration/integration work, and Microsoft Power Platform services such as

Power Apps, Power BI and Power Automate.

Confiz’s own homepage messaging underscores the “AI-forward” orientation: it markets programmes and proof-of-concepts around generative AI chatbots and highlights work tied to Dynamics 365 Copilot, as well as initiatives built on Azure OpenAI services.

Confiz also presents itself as having moved beyond pure services delivery into solutions and accelerators. Its published solutions list includes items such as a Dynamics 365 automotive solution, a “Gen AI virtual assistant” and an HR and payroll solution for Dynamics 365 – signals that the firm has been productising parts of its implementation experience, a strategy that can improve margins and create stickier client relationships when executed well.

In scale terms, Confiz says it has grown to a workforce of more than 700 team members, with offices spanning North America, the Middle East, Pakistan and Estonia. That is meaningfully smaller than Systems, but large enough to represent a serious delivery engine –particularly if integrated into Systems’ broader multi-region footprint.

Confiz’s deal announcement adds further colour on strategic positioning. It describes Confiz as bringing engineering, data and AI expertise to help large enterprises modernise technology landscapes and scale AI, and it highlights “two decades” of specialisation in retail and CPG. (Confiz) This is notable because retail and CPG are sectors where platform-heavy transformations (ERP, CRM, data platforms, demand forecasting and supply chain tooling) are often broad, multi-year programmes – precisely the sort of work where Systems’ scale and Confiz’s platform depth could be mutually reinforcing.

On paper, Systems’ acquisition of Confiz looks like a classic services-industry logic deal: combine scale with specialised capability, then attempt to drive growth through cross-selling, deeper platform partnerships and larger deal eligibility.

Systems already markets a wide portfolio and has long highlighted its alliances with global platforms, including Microsoft. Confiz’s identity, however, appears more tightly concentrated around the Microsoft ecosystem –Dynamics 365, Power Platform, and now Copilot-led enterprise workflows – alongside data and AI. For Systems, adding a Microsoft-heavy services specialist could deepen expertise in a commercial segment that tends to carry strong demand, recurring managed services revenues, and long-term client lock-in when implementations are successful.

Both firms talk about AI, but in slightly different languages. Systems positions itself as a broad digital transformation partner across data integration, application development, and

cloud and digital services. Confiz, by contrast, markets AI more explicitly – highlighting generative AI programmes, Copilot-related productivity tooling, and AI-driven data modernisation journeys. In a market where “AI capability” is quickly shifting from marketing slogan to procurement requirement, Systems may view Confiz as a way to accelerate credibility and delivery capacity in a fast-moving segment.

Systems’ Q3 2025 directors’ report describes its performance by verticals and notes that BFS (banking and financial services) remains the highest revenue contributor, while telecom is among the fastest-growing segments, and retail and technology are among the most profitable. Confiz’s own narrative puts significant weight on retail and CPG specialisation. If Systems can cross-pollinate Confiz’s retail/CPG expertise into its global sales engine – and, conversely, introduce Confiz’s Microsoft business applications stack into Systems’ BFS and telecom client base – the combined group could widen both its pipeline and its wallet share across existing accounts.

Confiz’s published list of “solutions” (including a Gen AI virtual assistant and industry-targeted Dynamics 365 solutions) suggests it is trying to package repeatable IP rather than purely selling hours. Systems, with its larger platform, may be able to scale those accelerators more widely, turning niche tools into broad offerings – though doing this well typically requires disciplined product management and clear go-to-market ownership.

Systems has explicitly disclosed that Systems shares will be issued to Confiz shareholders as the consideration for the merger. That structure typically helps the buyer preserve cash for other investments (or further acquisitions) and aligns incentives, because the selling shareholders participate in the combined entity’s future performance. At the same time, it introduces the usual trade-off: dilution for existing shareholders, making execution and synergy realisation more important.

Confiz has said it will continue operating as an independent business unit after the deal, backed by a network of regional talent hubs, and has positioned the transaction as a route to scale faster while strengthening customer value delivery. If Systems adopts a “federated” integration approach – keeping Confiz’s delivery culture and leadership intact while leveraging Systems’ sales reach and corporate backbone – it may reduce the risk of talent attrition, which is often the biggest value destroyer in services M&A.

The timing of the Confiz acquisition is notable because it comes as Systems is reporting a strong run in financial performance – potentially giving it the confidence (and equity-market credibility) to attempt a larger

consolidation move.

In its third-quarter 2025 report covering the nine months ended 30 September 2025, Systems reported consolidated revenue of Rs57.42 billion, up 18.9% year-on-year from Rs48.31 billion. Over the same period, consolidated net profit rose 46.3% to Rs7.94 billion (from Rs5.43 billion), while gross profit and operating profit increased 33.1% and 32.8%, respectively.

The company explicitly highlighted a key headline for investors: it exceeded its full-year 2024 operating profit and net profit in just nine months of 2025. It disclosed full-year 2024 operating profit of Rs8.15 billion and net profit of Rs7.46 billion, and said it surpassed those levels by 3.8% and 6.5% respectively over the nine-month period.

Systems also reported improved profitability ratios, stating gross margin and operating margin stood at 29.7% and 16.3%, respectively, and attributed the performance to growth, operational efficiencies, productivity improvements, billing rate improvement and optimisation of costs – particularly fixed costs. It also discussed the impact of currency movements, noting an exchange loss in the quarter that was offset by gains earlier in the year, and nonetheless said the quarter’s absolute net profit was higher than Q2.

From an operating standpoint, Systems’ directors’ commentary points to continued strategic focus on key verticals, noting BFS remains the highest revenue contributor, telecom among the fastest-growing, and retail and technology among the most profitable – with the company citing the development of AI use cases to support growth in targeted segments. That matters when considering Confiz’s integration: Confiz’s Microsoft business applications and AI-led data work could be positioned as an accelerator within these very vertical priorities.

In short, Systems is approaching the Confiz transaction from a position of strength: growing revenues, expanding profits, and an explicit drive to scale AI-related capabilities. The open question for investors is whether the proposed merger can compound that momentum – adding specialist Microsoft and AI depth without losing the delivery discipline and talent stability that have underpinned Systems’ recent results.

If the scheme progresses smoothly through approvals and the Lahore High Court process, the deal could mark one of the more consequential consolidation steps in Pakistan’s IT services landscape: a large listed exporter using equity to absorb a Microsoft-centric peer with an explicit AI and productisation layer – at a time when global clients are simultaneously cutting discretionary spend and doubling down on platform-led transformation.

Deregulated drug pricing allowed the company to improve gross margins, but the recall still caused revenue to decline

GlaxoSmithKline Pakistan Ltd (PSX: GLAXO) has just delivered one of those “two-truths” sets of numbers that investors in Pakistan’s pharmaceutical sector are rapidly getting used to: a sharp improvement in profitability metrics, alongside signs that demand is not keeping pace with the industry’s new pricing reality.

On the surface, the year looks like a breakout. Chase Securities’ briefing note highlights earnings per share (EPS) of Rs20.52 for CY24, compared to Rs1.68 in CY23 – a leap that speaks to both the operating leverage in the business and the impact of the industry’s shift in pricing power. The same note points to a still-resilient performance in the latest reported quarter: 3QCY25 EPS of Rs6.40, up from Rs6.05 a year earlier.

But revenue is telling a more complicated story – particularly in the most recent period. The company’s net sales in 3QCY25 are shown at Rs14.2 billion, down 4% year-on-year. In the same quarter, gross profit rose 29% and gross margin widened dramatically to 37% (from 27%), aided by a 16% decline in cost of sales. Put differently: pricing and product mix are now doing the heavy lifting, even when volumes and revenue wobble.

Management’s explanation for the weaker revenue trend converges on two intertwined issues. The first is volume compression in legacy blockbusters, as customers and prescribers respond to price increases. Management notes volume declines of 15% for Augmentin and 24%

for Amoxil, with management attributing this to price elasticity after necessary price hikes. Pakistan’s drug market has always had pockets of intense brand loyalty – especially in antibiotics –yet even strong brands eventually hit a demand wall when purchasing power is squeezed and cheaper substitutes are plentiful.

The second, more acute factor is the voluntary recall of Amoxil, one of the company’s major antibiotic brands. The recall was initiated due to a packaging issue, while management stressed that product quality was not compromised and framed the recall as an expression of “ethical standards”. The Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan’s (DRAP) own recall alert, published in August 2025, described the issue as a complaint related to the induction seal for Amoxil Suspension and Amoxil Forte Suspension – exactly the kind of defect that can force a swift, expensive response, even when the active ingredient itself is not the problem.

The financial implications of a recall are rarely confined to the recalled product alone. For a business like GSK Pakistan – where distribution relationships, pharmacy confidence, and prescriber perception matter – any disruption in supply can create an opening for competitors, particularly in crowded categories like antibiotics. Even if the company restores supply quickly, the “gap quarter” often shows up as lost market share that takes time (and promotional spending) to claw back.

And yet, the other half of the results story is unambiguously positive: gross margin expansion. The margin step-change is directly tied to

price adjustments following deregulation. GSK Pakistan commands roughly 6% market share by value. That line is important: it places GSK Pakistan among the companies best-positioned to benefit from a more flexible pricing regime –large enough to push price, but also diversified enough to manage the political and reputational heat that higher medicine prices can attract.

The most revealing management commentary is not about the recall itself, but about what it suggests regarding demand behaviour.

For years, Pakistan’s regulated pricing environment created a peculiar stability: many branded medicines stayed “affordable” on paper, even as currency depreciation and input inflation eroded manufacturer economics. When shortages hit, patients and doctors often substituted within the same brand family or relied on whatever was available. Deregulation has begun to unwind that system. When prices move sharply, consumers become more price-sensitive; pharmacies may shift their recommendations; and physicians may lean more heavily on generics and alternatives –especially in therapeutic areas where multiple equivalents exist.

That is essentially what GSK Pakistan is now describing for its older brands: volume declines in Augmentin and Amoxil are being attributed to price elasticity. This is not a unique problem for GSK; it is a sector-wide dynamic. But it is especially salient for multinationals, whose pricing decisions must balance local realities against global compliance and brand equity considerations.

The more forward-looking part of management’s message is about the pipeline – and it reflects the post-Haleon shape of the group. Analysts at Chase Securities, an investment bank, believe that future growth is expected to come from a more focused launch strategy aligned with GSK’s global footprint and R&D strengths, naming adult vaccines, oncology assets, and specialty therapies such as respiratory treatments as key areas of emphasis. This is consistent with how global GSK has been repositioning itself: less consumer-health, more “biopharma” with defensible science and higher-value portfolios.

Two operational comments in the briefing also hint at how the Pakistan business is being rebalanced.

Toll manufacturing continues, but has been scaled down for Haleon, with new partners brought in to rebalance the portfolio. That is a local echo of the global separation: consumer-health volumes that once ran through shared infrastructure are being untangled, forcing the Pakistan operation to either replace that utilisation or lean more heavily into its own ethical/ specialty mix.

On inputs, management describes API sourcing as diversified across Europe, China, and India, with reliance on India reduced compared to the past, and with a strong emphasis on quality and testing. In a period where supply-chain risk has become a board-level issue for Pakistani manufacturers – whether due to FX volatility, shipping costs, or geopolitical shocks – this kind of diversification is both a resilience play and a quality assurance story.

Finally, there is a sustainability footnote that is becoming increasingly common among large manufacturers: the company has installed a 2.2MW solar system at one of its manufacturing sites. It is not likely to move earnings on its own, but it does speak to cost management and ESG signalling – both relevant when energy costs and reliability remain persistent business constraints.

GSK Pakistan is unusual among Pakistan Stock Exchange listings for both its longevity and its multinational governance DNA. The company traces its legacy to Glaxo operations in the country, and GSK Pakistan’s own corporate website notes that GlaxoLaboratories Pakistan Ltd was the first pharmaceutical company listed on the Karachi Stock Exchange in 1951.

Operationally, the footprint is substantial. GSK Pakistan reports employing around 1,700 people, and states that its Global Supply Chain division manufactures over 400 million packs annually across three Karachi sites (including West Wharf, F-268 SITE and Korangi). That scale matters in a market where many local competitors remain single-plant operations and where international quality systems can be a differentiator – particularly for vaccines and higher-spec products.

The business mix has historically leaned

on large, familiar brands – especially in antibiotics and consumer-adjacent ethical lines. While detailed product economics vary by year, sellside disclosures frequently cite brands such as Augmentin and Amoxil among the key antibiotic franchises. The challenge now is that “legacy strength” is no longer enough. In a more flexible pricing regime, companies can fix broken unit economics – but they also risk triggering the very demand response that GSK Pakistan is now observing in its volumes.

GSK’s Pakistan strategy cannot be separated from the parent’s global restructuring over the past few years.

In July 2022, GSK separated its Consumer Healthcare business to form Haleon, an independent listed company. The separation was not a cosmetic change: it altered capital allocation priorities, executive attention, and the “portfolio narrative” the group tells investors. The strategic bet was that a more focused GSK could invest more heavily in its pharmaceutical and vaccines pipeline – while Haleon could pursue consumer health growth without being judged by pharma-style metrics.

The group’s disentanglement from Haleon did not stop at the initial demerger. GSK has since continued to reduce and then exit its stake, completing its sell-down over time as part of its refocus on biopharma. For Pakistan, that matters because the old GSK structure often meant shared services, shared manufacturing utilisation, and brand adjacency between ethical and consumer portfolios. As those ties loosen, local subsidiaries have to re-optimise: what capacity is dedicated to which lines, how distribution is structured, and how new launches are prioritised. Toll manufacturing has been scaled down for Haleon, and the portfolio is being rebalanced. The implication is that GSK Pakistan is increasingly being run as an “ethical pharma and vaccines” platform – more directly aligned to the parent’s science-led identity –rather than as a hybrid operation with a heavy consumer-health shadow.

Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry is going through its most consequential commercial reset in years, driven by changes in pricing policy.

In early 2024, the government approved deregulation of medicine prices outside the National Essential Medicines List (NEML) – a move widely interpreted as granting more pricing autonomy for non-essential products, while keeping essential medicines under tighter control. Discussion around the Drug Pricing Policy has also continued through amendments and implementation changes, reflecting the state’s attempt to balance affordability, availability, and industry viability. Crucially, reporting has emphasised that hundreds of essential drugs remain subject to government price controls, even as non-essential pricing becomes more flexible.

The “why” behind deregulation is not

hard to understand: when prices are held below sustainable levels amid currency depreciation and input inflation, products disappear, shortages emerge, and quality risks can rise. But the “so what” is what investors care about – and what GSK Pakistan’s results illustrate vividly.

Across the sector, deregulation has helped companies lift gross margins, because price increases can finally catch up to cost inflation. GSK Pakistan’s gross margin improvement –7% to 25% for CY24, and 27% to 37% in the latest quarter – sits squarely inside that broader margin story. Yet the same environment has introduced a new constraint: demand elasticity. When prices rise quickly, volumes can fall, and brand loyalty is tested. GSK Pakistan’s reported volume declines in Augmentin and Amoxil are a textbook example of that trade-off.

This is also why exports have become such a prominent theme in pharma boardrooms. With healthier margins and more predictable pricing for non-essential lines, companies can justify investment in certifications, capacity upgrades, and export-oriented product strategies. Pakistan’s pharma exports have reportedly grown strongly in FY25, with Business Recorder reporting exports rising to $457 million, a 34% increase year-on-year. Separately, trade bodies and government-linked documents – such as TDAP’s export strategy work – have underscored that scaling exports requires targeted investment and long-term planning, not just opportunistic selling.

GSK Pakistan sits slightly differently in that export narrative: the company is exploring export opportunities, but as a multinational it operates within a different framework, given many global manufacturing sites are already dedicated export hubs. In plain language: local players may chase exports as a central growth engine, while GSK Pakistan may treat exports more selectively – focusing instead on bringing in globally aligned launches, maintaining stringent quality standards, and optimising its Pakistan footprint within GSK’s wider supply chain.

That framing brings the story back to 2025’s defining episode for GLAXO: the Amoxil recall. In a newly deregulated market, where margins can be rebuilt but consumer patience for price hikes is Ltd, execution risk becomes more visible. A packaging defect that triggers a national recall can hit revenues even as profitability rises – because the market does not pause while a multinational fixes its supply chain.

For investors, the question for the next few quarters is whether GSK Pakistan can turn this “otherwise strong year” into a sustainable trajectory: rebuild antibiotic volumes where feasible, diversify growth through specialty launches, and use its scale and compliance culture as a moat – without losing relevance in a market that is rapidly becoming more competitive, more price-sensitive, and more demanding.

The competitively priced Chinese SUV has seen strong interest at the pre-booking phase and is expected gain significant share after launch

Pakistan’s car market has become used to “launch hype”, but the early response to the Jaecoo J7 appears to be translating into something more tangible: bookings at a scale that can materially move earnings for the listed members of the Nishat Group.

NexGen Auto, the Nishat-backed venture that has partnered with China’s Chery Automobile, announced the arrival of the Jaecoo and Omoda marques in October 2025. The Jaecoo J7 was introduced at Rs9.99 million, before being revised to Rs10.5 million effective 1 December 2025. That pricing matters, because it places the model squarely

in the heart of the rapidly expanding SUV/ crossover battleground – expensive enough to signal “premium”, but not so expensive that it becomes a niche import-like indulgence.

In its first month, the company cited 3,000 units booked – the highest first-month Jaecoo booking volume in any country, based on an official newspaper advertisement. Put simply, the pre-booking phase has functioned as a market test, and consumers appear to have answered loudly.

The operational implications show up in delivery timelines. With the J7 carrying a delivery time of roughly 3–4 months, this signals monthly production in the range of 700–800 units. For buyers, that means the

“new normal” in Pakistan’s auto market is continuing: waiting still exists, but it is no longer the multi-quarter ordeal that once made “own money” a parallel pricing system. For the Nishat Group, it suggests something even more important – NexGen Auto may be moving quickly from “brand launch” to “volume ramp”.

There is also a competitive point embedded in how the car is being positioned. Equity research analysts at Topline Securities, an investment bank, argue that the J7 is not primarily targeting Haval’s higher-tier SUVs; rather, it is competing more aggressively with “lower-tier SUVs such as the Corolla Cross and other petrol variants”, with the

J7 described as smaller than a Haval H6 but slightly bigger than a Corolla Cross. The J7 is priced at Rs10.5 million versus Rs7.9 million for the Corolla Cross and Rs12.9 million for the Haval H6. That is a deliberate “mid-point” strategy: offer size and features that feel like an upgrade from mainstream crossovers, while undercutting the more expensive end of the Chinese-SUV spectrum.

NexGen Auto is not listed, but its cap table makes it highly relevant for public market investors. Two cash-rich, publicly listed IPPs –Nishat Power Ltd (NPL) and Nishat Chunian Power Ltd (NCPL) – each hold 33% equity in NexGen Auto, according to the research note. Nishat Mills Ltd (NML), the flagship listed holding within the broader group, sits above them: NML owns 51% of NPL and 24% of NCPL. In other words, the economic exposure to the Jaecoo ramp-up is already “wired into” listed entities that investors can buy on the PSX.

Topline estimates that 800 units per month in FY27 and gross margins of 18% would translate into incremental EPS of Rs6.77/share for NPL and Rs6.52/share for NCPL.

Why does this matter so much for two power companies? Because their existing investment profile is unusually conservative by Pakistan standards. Topline describes both NPL and NCPL as “cash rich” following cash receipts linked to power-sector circular debt resolution, with net cash cited at Rs16 billion for NPL and Rs10 billion for NCPL. Both companies are investing Rs2 billion each in this auto business.

The strategic logic is easy to read: mature IPPs have faced questions globally about growth, contract durability, and longterm reinvestment opportunities. In Pakistan, where power-sector receivables and circular debt dynamics can distort cash flows, an auto venture that can scale quickly – especially one benefiting from a market-wide pivot towards SUVs – offers an alternative growth runway.

The Nishat Group is not new to automotive assembly. Its Hyundai partnership – Hyundai Nishat Motor (Pvt) Ltd – has already shown that the group can navigate the regulatory, localisation, and dealer-network challenges that define Pakistan’s auto industry.

Hyundai Nishat describes itself as a Nishat Group company and a joint venture involving Nishat Group, Japan’s Sojitz Corporation and Millat Tractors, with Hyundai Motor Company as the partner for manufacturing, marketing and distribution of Hyundai’s product line in Pakistan. The venture began assembling locally within a few years of its greenfield push; Hyundai Nishat’s own communications around its Faisalabad facility highlight the start of local production and the

broader ambition to expand the model line-up over time.

This matters for NexGen Auto for two reasons. First, NexGen Auto is assembling vehicles through toll manufacturing with Hyundai Nishat while also planning to invest Rs14.7 billion in working capital and development of its assembling facility (including a paint shop and other elements). That suggests a phased industrial strategy: use existing manufacturing infrastructure and operational expertise to get to market quickly, while building out dedicated capacity and deeper localisation later.

Second, the existence of Hyundai Nishat provides a ready reference point for how Nishat approaches the auto sector: partner with a global OEM, invest in manufacturing capability, and build the distribution footprint. NexGen Auto’s parallel partnership with Chery – through its export-focused Omoda and Jaecoo marques – fits that playbook.

Chery has become one of the most aggressive Chinese OEMs in global expansion, and its recent growth provides context for why Pakistani assemblers and groups are eager to align with it.

Reuters reported that Chery’s global sales rose 38.4% in 2024 to 2.6 million vehicles, with revenue rising sharply as well, and exports reaching about 1.14 million – maintaining its position as China’s top car exporter. Chery’s own international-facing communications echo the same arc, highlighting total sales above 2.6 million and exports above 1.14 million in 2024, alongside rapid growth in new-energy vehicles (NEVs).

Omoda and Jaecoo, in turn, are not random sub-brands. They are designed as export-oriented marques. Public brand descriptions note that Omoda and Jaecoo are sister brands owned by Chery and marketed outside China as part of its export strategy, often sharing dealer channels in many markets. This is important for Pakistan: it means the product pipeline, the brand positioning, and the righthand-drive/market adaptation capabilities are being built with international markets in mind – rather than Pakistan being an afterthought.

In practical terms, it is also why the J7 arrives with a “feature-forward” value proposition. Pakistan’s SUV consumers increasingly compare not just price and engine displacement, but infotainment, safety kits, hybrid systems, warranty packages, and dealership experience. In that environment, a Chery export brand can compete by over-delivering on perceived specifications relative to traditional incumbents.

The Jaecoo story is ultimately a story about the market shifting under the feet of the incumbents.