3 minute read

Reflection

from W19P325

by PDF Uploads

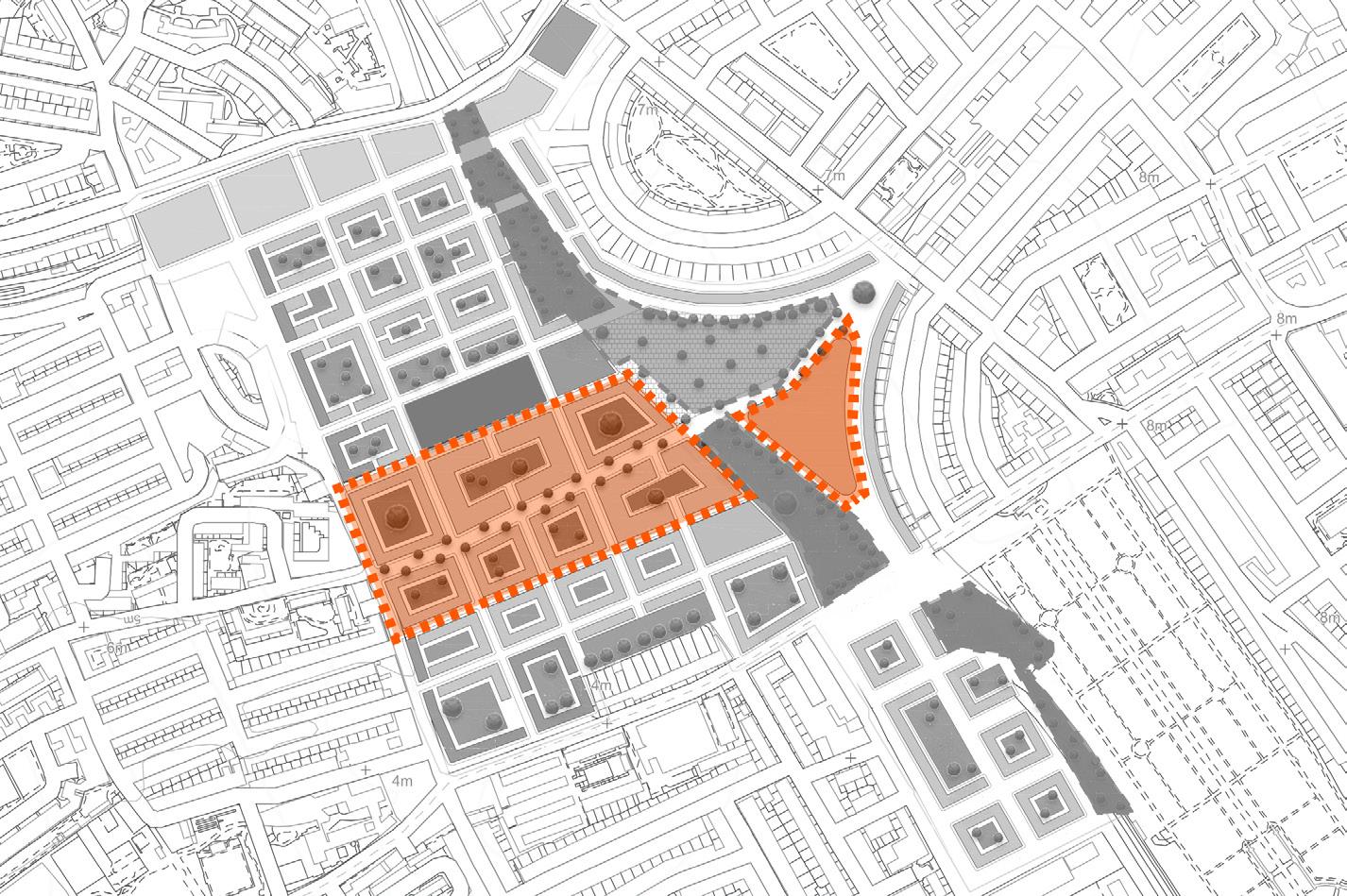

The first meeting involved reflecting on the learning from Task 1. This was an interesting exercise as not only did we realise how much we had learnt about the site and policy making process, but we were proud of the report we delivered despite losing two members of our team. In light of our small team size we decided to focus on the most essential policies necessary for delivering a successful scheme. This allowed us to still demonstrate a critical evaluation of the policies proposed. After reflecting on Task 1, we were able to summarise an evaluation of the SPD, highlighting what worked and what needed to change. As has been laboured across both reports, there were two fundamental shortfalls of the SPD. The first was the breakdown in consultation around the demolition social housing and the Earl’s Court Exhibition centres which led to major opposition and has slowed down the project. The second is the lack of ambition around a new cultural exhibition centre of a scale large enough to realise a socio-economic impact which could build on the legacy of the former venues. In view of these two dilemmas, we set out to develop our own vision for the scheme and set out three key planning objectives: sustainable housing, culture-led economic vitality and connectivity. These formed the foundation of our vision: “Delivering a new cultural quarter for West London, building on the legacy of Earl’s Court and creating a vibrant new neighbourhood”. After viewing other group’s projects in the module presentation, we discussed the pros and cons of different planning tools in achieving successful objectives. In light of how the Earl’s Court SPD’s guidance tools did not manage to achieve certain outcomes due to its flexibiilty, we decided that we would safeguard certain policies by establishing them in legally binding section 106 agreements. At first glance this seems a wise method of ensuring certain outcomes are achieved. However it posed the risk that developers will choose not to submit an application based on the local authorities’ expectations. Nonetheless, we decided to be confident and enshrine them as best we could.

For each objective we proposed two policies which were backed up by precedent case studies from around the world. These provided evidence of potential success for the policies, however their relevance to the site varied. On top of this, as discussed in the conclusion, their deliverabilty in the current political landscape is questionable. The final policies were the result of various discussions and iterations around what the most important outcomes should be. After an interesting exploration into funding and phasing (mitigating against land banking which has taken place in this scheme), we developed some indicators which can be used to measure the success of policies. This was important learning as it allowed us to better understand the monitoring process and the difference between outputs and outcomes. Outputs in urban planning practice are the policy documents as well as the built product itself. Outcomes describe the actual social, environmental and economic impact of policy. It is critical to evaluate the outcomes of schemes beyond the construction phase. All too often, there is scarce funding allocated to monitoring and this is detrimental to learning in the sector. This even applies even to the case studies we included in the report. Where data on the outcomes of case studies was missing (most of the time), we had to rely on the reputation of the scheme which is somewhat less verifiable. We propose that this scheme is carefully monitored over a minimum 10 year period, with funding ringfenced for independent evaluation.

Reflection

Overall it was a pleasure to work together and we each brought our unique skills to the table to create a good report, thus relfecting real life teamwork scenarios. Despite being a small team, we carefully sketched out a report structure and shared the work equally.