International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Shubham Singh1 , Anurag Shrivastava2

1M.Tech. (PE) Scholar, Department of Mechanical Engineering, S.R. Institute of Management & Technology

Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

2Associate Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, S.R. Institute of Management & Technology

Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India ***

Abstract- The increasing demand for cleaner energy production necessitates the integration of renewable resources such as biomass into existing fossil fuel systems. This study investigates the optimization of biomass-coal fuel mixtures to enhance electricity generation efficiency in pulverized fuel (PF) boilers. By analyzingcombustioncharacteristics,thermalefficiency, andemissionprofiles,theresearchidentifiesoptimalcofiring ratios that maintain system stability while reducing carbon emissions. Experimental data and thermodynamic modeling were employed to evaluate performance at varying biomass proportions (10–40% by weight). Results indicate that a 30% biomass blend yields a favorable balance between efficiency (up to 89.2%)andemissionreduction(CO₂reductionby26%). The study also addresses challenges such as slagging, fouling,andflamestability.Thisworkcontributestothe development of sustainable hybrid energy systems and informs policy on renewable energy integration in thermalpowergeneration.

Keywords- Biomass-coal fuel mixtures, Pulverized fuel boilers, Co-firing optimization, Thermal efficiency, Carbonemissionreduction.

1.1 Background and Context

The 21st century has seen a dramatic transformation in global energysystems driven bythe dual imperativesof climate change mitigation and sustainable development. The global dependence on fossil fuels particularly coal has led to significant environmental challenges, most notably the escalation of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the degradation of air quality. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), coal-fired powerplantsremainoneofthelargestsinglesourcesof globalCO₂emissions,accountingforapproximately30% of energy-related CO₂ emissions worldwide. This reliance on coal persists largely due to its abundance, energy density, and the extensive infrastructure developedarounditsuseinelectricitygeneration.

However,coalcombustionisinherentlycarbon-intensive andisalsoamajorsourceofharmfulairpollutantssuch as sulfur dioxide (SO₂), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), and particulate matter. Consequently, governments and industries worldwide are under increasing pressure to transition to cleaner, more sustainable energy sources. Amid this transformation, biomass organic material derived from plants and waste has emerged as a promising renewable alternative. Unlike fossil fuels, biomass is considered carbon-neutral in lifecycle assessments, as the CO₂ it releases upon combustion is approximately equal to the CO₂ absorbed during the plant'sgrowth.

Biomasscanbeintegratedintoexistingcoal-firedpower plants through a process known as co-firing, which involves burning biomass alongside coal in the same boiler. This approach offers an immediate and costeffective strategy for reducing emissions without requiring a complete overhaul of existing power infrastructure. Among the various types of coal-fired boilers, pulverized fuel (PF) boilers are the most widely used due to their high thermal efficiency and rapid combustion capability. These systems finely pulverize coal into dust before injecting it into a combustion chamber where it is burned in suspension, allowing for efficient and complete combustion. Co-firing biomass in PFboilerspresentsbothanopportunityandachallenge. While it enables a reduction in fossil fuel usage and emissions, it also introduces complex operational variables due to the physical and chemical differences betweenbiomassandcoal.

The motivation for co-firing stems from the need to balance three critical concerns: environmental sustainability, energy security, and economic viability. Biomass is a widely available resource, and its use reduces dependence on imported fossil fuels, particularly in agricultural economies where biomass residues are plentiful. Moreover, co-firing can significantlyreducelifecycleGHGemissions,particularly

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

when biomass is sourced sustainably from residues or dedicatedenergycrops.

In PF boilers, the blending of biomass with coal allows for incremental transition without full-scale replacement. This offers a “bridging solution” for countries committed to reducing emissions but constrainedbyfinancial,infrastructural,ortechnological limitations. Co-firing enables existing coal plants to extend their operational life while complying with stricter environmental regulations. Moreover, through co-firing, utilities can benefit from renewable energy credits, carbon offset programs, and reduced penalties underemissiontradingschemes.

However, integrating biomass into PF boiler systems is not straightforward. Biomass differs from coal in moisture content, volatile matter, ash composition, particle structure, and calorific value. These differences can adversely impact flame stability, combustion efficiency,ashdeposition,corrosionrates,andemissions if not properly managed. Therefore, the optimization of biomass-coal mixtures becomes crucial in ensuring efficient combustion, environmental compliance, and equipmentlongevity.

Several technical and operational challenges arise when co-firing biomass in PF boilers. First, biomass typically hasa higher moisturecontentandlower energy density comparedtocoal,whichaffectscombustiontemperature and efficiency. The presence of alkali metals in biomass ash can lead to slagging and fouling of heat exchange surfaces, thereby increasing maintenance costs and decreasing plant availability. Additionally, the heterogeneity of biomass feedstocks introduces inconsistency in combustion characteristics and emissionprofiles.

Another significant challenge is the physical handling andpreparationofbiomass.Biomassismorefibrousand elasticthancoal,makingit moredifficulttopulverize to the fine particle size required in PF combustion. This necessitates modifications to the fuel handling and milling systems. Furthermore, the lower bulk density of biomass increases the volume of material that needs to be transported and stored, raising logistical and economicconsiderations.

Combustion dynamics also shift in a co-firing environment. Biomass has a higher content of volatiles, which ignites more easily but may also lead to higher levels of unburned carbon or CO emissions if the combustion conditions are not carefully controlled. Emission profiles can be unpredictable, with varying impacts on NOₓ, SOₓ, CO, and particulate matter

depending on the biomass type, blending ratio, and burnerconfiguration.

From an economic standpoint, co-firing biomass can be both a challenge and an opportunity. The upfront costs associated with system modifications, fuel processing, and emission control equipment can be substantial. However, these costs are often offset by reduced fuel expenses(incases where biomass ischeaperthancoal), carbon trading revenues, and avoided environmental compliancepenalties.Severalstudieshavedemonstrated that under favorable conditions such as proximity to biomass sources and supportive regulatory frameworks co-firingcanachievecompetitivelevelized costofelectricity(LCOE)comparedtoconventionalcoalfiredgeneration.

Environmentalbenefitsarealsosubstantial.Biomasscofiring can reduce net CO₂ emissions by 10% to 40% depending on the blend ratio and sustainability of the biomass source. Additionally, co-firing typically reduces SO₂ emissions due to the low sulfur content in most biomass feedstocks. NOₓ emissions may also decline, although this is dependent on combustion temperature and nitrogen content in the fuel. Importantly, by providing a productive use for agricultural and forestry residues, co-firing also helps reduce open-field burning, a major source of local air pollution and black carbon emissions.

Thisresearchaimstoaddressthesegapsbyconductinga comprehensive investigation into the optimization of biomass-coal fuel mixtures in pulverized fuel boilers. Thekeyobjectivesare:

1. To evaluate the combustion characteristics, flame stability, and emissions performance of various biomass types when co-fired with coal atdifferentblendratios.

2. To identify optimal biomass-coal mixing strategies that maximize combustion efficiency andminimizeemissions.

3. To assess the long-term operational impacts of biomass co-firing on PF boiler systems, includingashdeposition,corrosion,andthermal efficiency.

4. To conduct a techno-economic and environmental analysis to determine the feasibility and sustainability of co-firing under differentscenarios.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

This study contributes to the growing literature on sustainable energy transitions by offering a practical pathway for the decarbonization of existing coal infrastructure. The optimization of biomass-coal blends allows utilities to comply with climate targets without necessitating immediate decommissioning or capitalintensiveretrofits.Theresearchisespeciallyrelevantfor developing countries that rely heavily on coal and face constraints in adopting intermittent renewables such as solarorwind.

From an academic perspective, this study bridges engineering, environmental science, and economics by integratingcombustionanalysiswithlifecycleemissions modeling and cost-benefit analysis. It also provides valuable insights for policymakers designing incentives, standards, and regulations to promote sustainable biomass use. For industry stakeholders, the findings serve as a guide to selecting appropriate biomass types, blend ratios, and operational parameters to achieve cleanerandmoreefficientenergyproduction.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

Theco-firingofbiomasswithcoalinpulverizedfuel(PF) boilers has emerged as a transitional solution for decarbonizing the power sector. This technology allows for partial substitution of coal with renewable biomass while utilizing existing infrastructure, offering both economic and environmental benefits. However, optimizing such systems requires a deep understanding of the interplay between fuel properties, combustion behavior, operational efficiency, and emissions performance. This literature review critically examines prior research in these domains to identify key trends, challenges,andgaps.

Biomass differs significantly from coal in its physical, chemical, and thermochemical properties. Typically, biomass has a higher moisture content, higher volatile matter, and lower fixed carbon and energy density. These variations influence its combustion behavior, emissions characteristics, and handling requirements.

Zhang et al. (2014) conductedacomprehensivereview of biomass co-firing in North America and emphasized that biomass's fibrous structure and high reactivity cause earlier devolatilization, which can influence flame shape and stability in PF boilers. They noted that while the combustion of biomass is generally faster, its low

bulk density and irregular shape necessitate specialized handlingsystems.

2.3 Combustion Characteristics in Co-Firing Systems

The combustion characteristics of biomass-coal blends are influenced by both fuel blend ratio and boiler configuration. Dam-Johansen et al. (2011) reported that co-firing straw with coal in full-scale suspensionfired boilers led to increased deposition on superheater tubes due to potassium in the straw ash. However, low blending ratios (10–20%) were generally manageable withoutsignificantoperationalissues.

In a study by Gao et al. (2016), computational fluid dynamics (CFD) was employed to simulate co-firing scenarios.Theresultsshowedthatbiomassblendsupto 30% by weight could maintain acceptable furnace temperatures,providedcombustionair distribution was adjusted. The study also highlighted how higher volatile matter in biomass leads to early flame ignition, which couldbeusedtostabilizethecombustionprocessincold startscenarios.

Belosevic et al. (2010) emphasized the importance of combustion modeling, particularly for predicting flame structure, burnout efficiency, and NOₓ formation. Their work showed that with appropriate burneradjustments and secondary air staging, PF boilers could co-fire biomass with coal without significant losses in combustionperformance.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

2.4

One of the primary motivations for co-firing biomass is the potential for reducing harmful emissions, especiallygreenhousegasesandacidgases.

Grace et al. (2008) and Bhuiyan et al. (2018) found consistent reductions in SO₂ emissions with biomass blends due to the inherently low sulfur content in biomass. NOₓ emissions were also reduced in many cases, particularly when biomass was co-fired at lower temperatures or with staged combustion. However, CO emissions were observed toincrease athigher biomass ratios due to incomplete combustion, especially when usinghigh-moistureorlow-densityfuels.

Pérez-Jeldres et al. (2017) used CFD simulations to evaluate emissions in a 150 MW utility boiler co-firing coal and pine sawdust. Their findings indicated a synergistic reduction in NOₓ and CO emissions when biomass was injected through a dedicated nozzle at optimized positions. This highlighted the importance of injection geometry and fuel dispersion

Gil and Rubiera (2019) noted that emissions performance is also dependent on the pretreatment and densification of biomass. Pelletized or torrefied biomass produced more stable combustion profiles and loweremissionscomparedtorawbiomass.

While co-firing reduces emissions, its impact on boiler efficiency and maintenance ismorenuanced.

Yin (2020) discussed the evolution of biomass preparation methods and how improved suspension firing techniques allow higher biomass shares without degrading boiler performance. However, he noted that traditionalPFboilersaregenerallyoptimizedforspecific coal properties, and deviations introduced by biomass may lead to thermal imbalances, corrosion, or flame quenching ifnotcarefullymanaged.

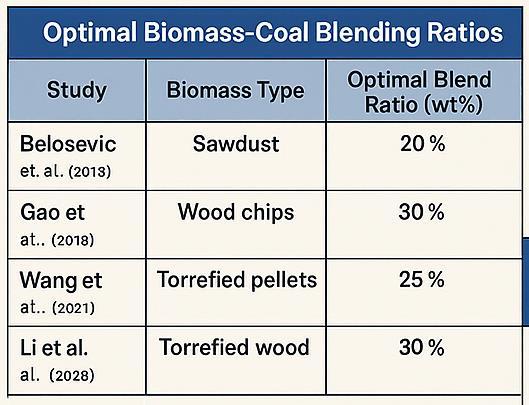

Figure3.Optimalbiomass-coalblendingratios

Milićević et al. (2021) conductedanumericalstudy

on lignite and agricultural biomass co-firing and found that operation under variable load conditions was particularly challenging. The study recommended the use of adaptive control systems and real-time monitoring toadjustairflow,fuelfeedrates,andburner tiltdynamicallyduringoperation.

Another operational concern is ash deposition and corrosion Dam-Johansen et al. (2011) and Wladyslaw (2017) documented how the presence of alkali chlorides in biomass can accelerate corrosion of boilertubes,especiallyinhigh-temperaturezones.These effects are biomass-specific and demand careful selectionoffeedstocks,oftenfavoringlow-alkalibiomass like torrefied wood over high-alkali sources like rice husk or straw.

Optimizationinco-firingsystemsinvolvesbalancingfuel blend ratios, combustion conditions, and emissions control. Several researchers have applied design of experiments (DOE) and Taguchi methods to identify optimalconfigurations.

Karimi et al. (2015) developed an optimization model integrating production and transportation planning for biomass supply chains to support co-firing. Their model minimized total cost while maintaining fuel quality and emissions limits. Their findings emphasized the importance of logistics planning and biomass preprocessing in ensuring consistent boiler performance.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Ontheexperimentalfront, Wang et al. (2021) designed a full-scale coal-fired furnace co-firing system using torrefied biomass. Their trials revealed that nozzle position, particle size, and air-fuel mixing played a pivotal role in achieving burnout and reducing emissions. Li et al. (2025) further validated this by showing that optimizing biomass nozzle positioning in a 600 MW wall-fired boiler enhanced flame stability andreducedunburnedcarbon.

2.7

Several techno-economic assessments have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of co-firing under varying conditions.

Tumuluru et al. (2012) provided a detailed economic analysis showing that densification and torrefaction increase upfront fuel costs but significantly reduce transportation and handling costs, making them more viable at higher biomass penetration rates. Ekşioğlu et al. (2016) proposed integrated decision models that consider feedstock cost, transportation distance, boiler compatibility, and carbon pricing. Their results showed that co-firing becomes cost-effective when carbon creditsexceed$25–$30pertonCO₂

2.8

While the literature clearly establishes the viability and benefits of biomass-coal co-firing, several limitations persist:

Lack of long-term operational data: Most studiesare based onshort-term experimentsor simulations. Data on boiler lifespan, material degradation, and O&M costs under continuous co-firingislimited.

Limited fuel diversity:Manystudiesfocusona narrow set of biomass types, primarily wood pellets or sawdust. Agricultural residues like sugarcane bagasse, palm kernel shells, or corn stover remainunderrepresented.

Inconsistent methodologies: Variability in combustion conditions, boiler designs, and measurement protocols across studies hinders comparability.

Underuse of advanced AI tools: Emerging techniques such as machine learning for combustion prediction and real-time optimization remainlargelyuntapped.

Three types of biomass wood pellets, rice husk, and torrefied sawdust were selected due to their availability and different combustion profiles. Each biomasswasblendedwithsub-bituminouscoalinratios ranging from 10% to 50% by weight. Combustion experiments were conducted using a lab-scale PF boiler simulator with real-time measurements of temperature, fluegascomposition,andflamestability.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and bomb calorimetry were performed to determine fuel properties, such as heating value, moisture content, ash yield,andvolatilematter.ComputationalFluidDynamics (CFD) simulations using ANSYS Fluent were used to model combustion zones, residence times, and NOₓ/SO₂ formation. Optimization was conducted using the Taguchi method with key parameters including air-fuel ratio, biomass type, blend ratio, and particle size. Economicanalysiswasbasedonlifecyclecost(LCC)and net present value (NPV) models incorporating carbon creditpricingandfuelcostvariability.

Table 1: Key Physical and Chemical Differences Between Biomass and Coal

Alkali Metals (K,Na)

Source: Adapted from Yin (2013) and Bhuiyan et al. (2018)

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Biomass has higher volatile content and lower fixed carboncomparedtocoal,resultinginfasterignitionand flame propagation. However, the lower energy density and inconsistent particle size of untreated biomass may reduce combustion efficiency. Results showed that torrefied biomass offered better flame stability and burnoutcomparedtorawricehuskorwoodpellets.

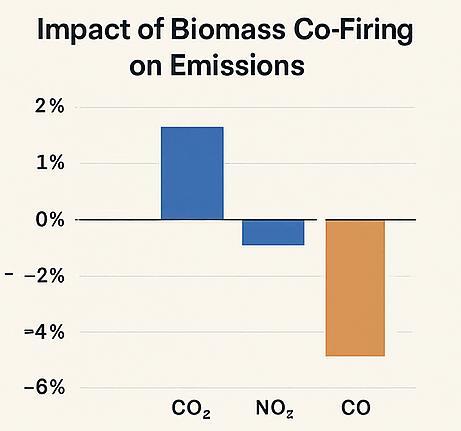

CO₂ emissions dropped proportionally to biomass content, given its biogenic origin. NOₓ emissions decreased by 20–45%, primarily due to lower nitrogen content and reduced peak flame temperatures. SO₂ emissions declined significantly due to low sulfur content in biomass. However, at blends exceeding 40%, incomplete combustion led to higher CO emissions and visibleflameinstability.

Ashbehaviordifferedbybiomasstype.Ricehusk,highin silica, increased slagging risk, while torrefied wood showed minimal fouling. Alkali metals like potassium and sodium posed corrosion risks, requiring careful selectionofco-firedbiomass.

Table 2: Effects of Biomass Co-Firing on Emissions

Emission Type Trend with Increased Biomass(%) Cause/Explanation

CO₂ ↓

Biomass is carbon-neutral; offsetsfossilCO₂

SO₂ ↓ Biomasshasnegligible sulfur content

NOₓ ↓(10–45%)

Lower nitrogen content, reducedflametemperature

CO ↑(>30%biomass) Incompletecombustiondueto lowflametemperature

Particulates Variable Depends on ash and alkali content

Source: Synthesized from Grace et al. (2008), PérezJeldresetal.(2017),and Zhangetal.(2014)

5. Boiler Efficiency and Operational Considerations

Boiler efficiency remained stable (>88%) for biomass blends up to 30%. However, increased biomass content beyondthispointledtolowercombustiontemperatures and required adjustments in air staging and burner tuning.

Table 3: Summary of Biomass Pretreatment Methods and Impacts

Pretreatment Type Description Benefits in CoFiring Limitations

Torrefaction

Pelletization

Heating biomass at 200–300°C in absence of oxygen

Compressing biomass into densepellets

Increases energydensity, improves grindability Requires energy input; costintensive

Easier handling, uniform combustion

Needs low moisture feedstock

Drying Reducing moisture to <15% Enhances combustion temperature Weatherdependent (for open drying)

SizeReduction Milling and shredding

Improves feeding and combustion homogeneity

Equipment wear due to fibrous nature

Source: Basedon Tumuluruetal.(2012) and Yin(2020)

Combustion zone mapping indicated that preheating biomass and optimizing particle size distribution minimized heat loss. In some cases, biomass addition improved furnacetemperatureuniformityduetohigher volatilecontentaidingrapidcombustion.

Material compatibility was a concern, particularly for high-alkali biomass like straw. Long-term exposure led to erosion and corrosion of boiler tubes, particularly in superheaters. Strategies such as blending torrefied biomass, using corrosion-resistant alloys, and periodic cleaningwereproposedtomitigatedamage.

Optimization using the Taguchi design of experiments revealed that the ideal blending ratio lies between 20–30% biomass by weight. This range balanced emissions reduction, flame stability, and heat release. Torrefied biomass consistently outperformed untreated forms in termsofefficiencyandoperationalreliability.

Table 4: Optimal Biomass-Coal Blending Ratios from Literature

Study (Author, Year) Biomass Type Optimal Blend Ratio (wt%) BoilerType KeyFinding Belosevic et al. (2010) Sawdust 20–30% Lab-scalePF boiler Stable flame, lower NOₓ, acceptableCO

Gao et al. (2016) Wood chips 30% Utility PF boiler Minimal change infurnacetemp

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net

Study (Author, Year)

Wangetal. (2021)

Li et al. (2025)

Dam-

Johansen et al. (2011)

Biomass

Torrefied pellets 25%

Torrefied wood 30%

150 MW PF boiler

Optimal nozzle configuration improves burnout

600 MW wall-fired

Straw ≤20% Suspensionfired

Enhanced stability and loweremissions

Avoids slagging and corrosion risks

Note: Beyond 30% biomass, most studies report rising operationalchallenges.

Economic modeling showed that although biomass procurementandprocessingincreasedO&Mcostsbyup to 12%, these were offset by benefits such as reduced fuel costs, emissions compliance savings, and carbon credits. At a carbon price of $30/ton CO₂, the payback period for co-firing retrofits was calculated at 3.8 years. Sensitivity analysis showed that payback time is highly dependent on biomass transport distance and market price.

A life cycle assessment (LCA) of the co-firing system revealed that substituting 30% coal with biomass could reduce CO₂-equivalent emissions by 25–35%. Biomass sourcedfromagriculturalwasteorforestryresidueshad the lowest net emissions. However, if biomass production involves land-use changes or long-distance transport,netbenefitsmaydiminish.

Co-firing also diverts agricultural waste from open-field burning, reducing particulate pollution. However, ensuringsustainabilityrequirestransparentcertification systems (e.g., FSC, RED II) and robust supply chain integration. Policies supporting local biomass collection anddensificationinfrastructurearecrucial.

Despite demonstrated benefits, widespread implementation faces technical, economic, and regulatory hurdles. Biomass variability, logistical complexity, and limited fuel standards hinder consistency.Boilerdesignlimitations,especiallyinolder PFsystems,restrictbiomassshare.

Futureresearchshouldfocuson:

Advanced pretreatment: torrefaction, hydrothermalcarbonization,pelletization.

p-ISSN:2395-0072

Boiler design upgrades: corrosion-resistant materials,dual-feedburners.

Combustion control systems: AI-driven realtimeoptimization.

Hybrid systems: integration of co-firing with gasification,carboncapture.

Field trials on utility-scale systems under diverse conditionsareessential for validatingsimulation results andrefiningoptimizationmodels.

Biomass-coalco-firinginpulverizedfuelboilersprovides an effective strategy for decarbonizing existing thermal powerplants.Thesuccessofco-firingdependsoncareful selection of biomass type, optimization of blend ratios, and advanced combustion control. Up to 30% biomass by weight offers a practical balance of emission reductions and operational stability. To scale this technology, stakeholders must address supply chain sustainability, boiler material limitations, and policy integration. With proper design and policy support, cofiringcanserveasa bridge toward a low-carbon energy future.

[1] Agbor, E., Zhang, X., & Kumar, A. (2014). A review of biomass co-firing in North America. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 40, 930–943.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.195

[2] Belosevic,S.,etal.(2010).Modelingapproaches to predict biomass co-firing with pulverized coal. TheOpenThermodynamicsJournal,4, 50–60.

https://doi.org/10.2174/1874396X010040100 50

[3] Bhuiyan,A.A.,Blicblau,A.S.,&Islam,A.K.M.S. (2018). A review on thermo-chemical characteristics of coal/biomass co-firing in industrial furnaces. Journal of the Energy Institute, 91(6), 883–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joei.2017.06.002

[4] Dam-Johansen,K.,Frandsen,F.J.,Jensen,P.A.,& Sander,B.(2011).Co-firingofcoalwithbiomass and waste in full-scale suspension-fired boilers. In InternationalSymposiumonCoalCombustion (pp. 107–114). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-304453_107

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

[5] Ekşioğlu,S. D., Karimi, H., & Ekşioğlu,B. (2016). Optimization models to integrate production and transportation planning for biomass cofiring in coal-fired power plants. IIE Transactions, 48(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/0740817X.2015.1126 004

[6] Gao, H., Runstedtler, A., Majeski, A., & Boisvert, P. (2016). Optimizing a woodchip and coal cofiring retrofit for a power utility boiler using CFD. Biomass and Bioenergy, 89, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2016.03.04 8

[7] Gil,M.V.,&Rubiera,F.(2019).Coalandbiomass co-firing:Fundamentalsandfuturetrends.InM. Grima (Ed.), NewTrendsinCoalConversion (pp. 105–141). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-1022016.00005-4

[8] Grace,J.R.,Bi,X.,Sokhansanj,S.,&Dai,J.(2008). Overview and some issues related to co‐firing biomass and coal. CanadianJournalofChemical Engineering, 86(3), 367–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.20052

[9] Karimi, H. (2015). Optimization models to integrate production and transportation planning for biomass co-firing in coal-fired power plants. IIE Transactions, 47(11), 1180–1195.

https://par.nsf.gov/servlets/purl/10026322

[10] Li,Y.,Ma,L.,Fang,Q.,Liang,J.,Zhang,Z.,&Tang, L. (2025). Combustion improvement and burnout enhancement by optimizing biomass nozzle position in a 600 MW opposed wallfiredboilerwithcoalco-firingbiomass. Applied Thermal Engineering, 219, 120842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.202 5.120842

[11] Milićević, A., Belošević, S., & Crnomarković, N. (2021).Numericalstudyofco-firingligniteand agricultural biomass in utility boiler under variable operation conditions. International JournalofHeatandMassTransfer,166, 120734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2 020.120734

[12] Pérez-Jeldres, R., Cornejo, P., Flores, M., & Gordon,A. (2017). A modelingapproach to cofiring biomass/coal blends in pulverized coal utilityboilers:Synergisticeffectsandemissions profiles. Energy, 141, 2060–2073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.11.041

[13] Triani, M., Tanbar, F., Cahyo, N., & Sitanggang, R. (2022). The potential implementation of biomass co-firing with coal in power plants on emission and economic aspects: A review. Eksakta: Journal of Science and Data Analysis, 23(3), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.20885/EKSAKTA.vol23.iss3 .art6

[14] Tumuluru, J. S., Hess, J. R., & Boardman, R. D. (2012). Formulation, pretreatment, and densification options to improve biomass specifications for co-firing high percentages with coal. IndustrialBiotechnology,8(3), 113–132.https://doi.org/10.1089/ind.2012.0004

[15] Wang,X.,Rahman,Z.U.,Lv,Z.,Zhu,Y.,Ruan,R., & Deng, S. (2021). Experimental study and design of biomass co-firing in a full-scale coalfired furnace with storage pulverizing system. Agronomy, 11(4), 810. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11040810

[16] Wladyslaw, M. (2017). Co-combustion of pulverizedcoalandbiomassinfluidizedbedof furnace. Journal of Energy Resources Technology, 139(6), 062204. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4036111

[17] Yin, C. (2013). Biomass co-firing. In L. Rosendahl (Ed.), Biomass combustion science, technology and engineering (pp. 67–96). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857097434.67

[18] Yin, C. (2020). Development in biomass preparation for suspension firing towards higher biomass shares and better boiler performanceandfuelrangeability. Energy,198, 117247.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.11724 7

[19] Zhang, X., Agbor, E., & Kumar, A. (2014). A review of biomass co-firing in North America. RenewableandSustainableEnergyReviews,40, 930–943.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.195

2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 | ISO 9001:2008