International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

1Consulting Environmental Engineer, Retired Superintending Engineer, PHED, Govt. of West Bengal

Abstract - Age (residence time) of water in distribution systems governs disinfectant persistence, microbial risk, and user acceptability. This study applies EPANET 2.2 to a rural multi-village Water Distribution Network (WDN) in West Bengal having low demand and minimum permissible diameter (≈90 mm OD; ≈80.4 mm ID) under extended period simulation (EPS) to quantify systemwide water age and identify vulnerability zones. Using assumed diurnal peaking factors (PF) over 96 hours (Case-1) and two simplified constant-demand scenarios (Case-2; PF=1 and PF=3). It is shown that in Case-1 (i) average network age during 73–96 h ranges ~9.9–16.3 h (mean ≈12.4 h) while maximum node age ranges ~30.1–39.7 h (mean ≈35.2 h); whereas in Case-2 (ii) terminal segments exhibit very long travel times (≈17.7 h fora length of 785 m at PF=1, improving to ≈5.9 h at PF=3). The results indicate persistent risk of low chlorine residuals at the periphery under single-point chlorination.

The findings highlight that water age analysis provides an essential diagnostic tool for rural WDNs, revealing hidden vulnerabilities not captured by conventional chlorine decay modeling alone. Incorporating water age into routine water quality assessments can guide the placement of chlorine booster stations, inform dosing strategies, and support more resilient distribution system design and operation. The study demonstrates that water age analysis offers a more comprehensive understanding of the fate of residual chlorine in a rural WDN.

Key Words: Rural Water Supply, Water Distribution Network, Water Quality Analysis, Hydraulic Analysis, Water AGEAnalysis,ResidualChlorine,EPANET,Extended Period Simulation.

In water supply systems, safety depends not only on treatment at the source but also on conditions during distribution. Water that is safe at the treatment plant/ sourcemaybecomecontaminatedduetoleakages,microbial growthonpipewalls,andotherfactors.Chlorinationisthe most widely used disinfection method, valued for both its effectivenessagainstbacteriaanditsresidualprotection(B. Kowalska et al., 2006; Denis Nono et al., 2019; J. J. Vasconcelosetal.,1997).

However, chlorine effectiveness declines with time as it decaysduringtransport,withhigherdecaylinkedtolonger

residencetimes.Whiledecaymodelspredictconcentration overtimeanddistance,theycannotfullyexplainpersistent under-chlorinationinsomeareas.Akeyoverlookedfactoris Water AGE theresidence timeof waterinthesystem whichdirectlyinfluencesdisinfectantpersistence,microbial regrowth, and overall acceptability. Water age analysis addresses this by showing how hydraulic residence times governchlorinebehaviorthroughoutthenetwork.

Rural water supply systems in India typically have low demandandlong,scatteredpipelines.Minimumdiametersof 75–90mm(OD)aregenerallyusedduetoregulatorynorms. Chlorineisusuallydosedonlyonceattheheadworks,after whichitdecaysprogressivelyaswatertravelsdownstream (B Kowalska et al., 2006). Extended residence times accelerate decay (Hossein Shamsaei et al., 2013), creating zonesvulnerabletolossofresiduals.

International guidelines, including those of the WHO, stipulate that free residual chlorine concentrations below 0.2–0.3mg/Lareundesirableforsafesupply(JuliusCeaser, 2024).Adequateresidualsatallnetwork nodesserveas a safeguard against microbial contamination, ensuring bacteriological safety of the distributed water. However, excessive dosing to compensate for decay is not a sustainable strategy, as it can lead to the formation of disinfection by-products (DBPs) and generate consumer acceptability issues (Ababu T. Tiruneh et al., 2019; Denis Nonoetal.,2019;HosseinShamsaeietal.,2013).Residual chlorineisnotconstantacrossadistributionsystem;rather, it fluctuates spatially and temporally depending on flow dynamicsandlocalresidencetime.

Chlorine decay during transport through a WDN occurs predominantlyviatwopathways:bulkdecay(kb)andwall decay(kw).

Themagnitudeof bulkdecayisinfluencedbywaterquality parameters such as natural organic matter, inorganic constituents, and temperature. Conversely, wall decay is largelydeterminedbythematerial,condition,andageofthe

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

pipelineinfrastructure(J.J.Vasconcelosetal.,1997,Julius Caesaretal.,2024)

Reportedvaluesofbothcoefficientsshowwidevariability, even within the same network, due to site-specific conditions and operational practices (P. R. Bhave and R. Gupta,2006).Thisvariabilityunderlinestheimportanceof case-specific calibration of chlorine decay parameters for accuratepredictionofresidualchlorinepersistence.

Thisstudyapplieswaterageanalysisusing EPANET 2.2 toa ruralmulti-villageWDNinWestBengal,India.Theobjective istodemonstratehowwateragegovernsresidualchlorine persistenceandtoidentifyvulnerablezoneswithexcessive residencetimes.ExtendedPeriodSimulation(EPS)results emphasizetheroleofresidencetimeasacriticaldesignand operationalparameter,particularlyinsystemsdependenton single-pointchlorination.

1.3 Challenges in Quality Analysis in Rural Water Supply System

Intermittentwatersupplyremainsthemostcommonmode ofoperationinruralIndia.Longgapsbetweensupplyhours cause pipelines to drain and making conventional quality analysislessreliable(RoopaliV.GoyalandH.M.Patel,2015)

To overcome this limitation, the present work assumes a continuous 24×7 supply with variable hourly demand, creatingasimplifiedbutrepresentativeframeworkforwater ageandchlorineresidualevaluation.

Theselectedcasestudyrepresentsa medium-sized multivillage water supply scheme,referredtoasthe Balagarh network (SoumitraGanguly,2025).Thesystemistypicalof rural infrastructure being implemented across India and provides a suitable example for exploring the interaction betweenwaterageandchlorineresiduals.

2.1

Pipes and Nodes:488pipes,486nodes

Reservoirs:1overheadservicereservoir(OHSR)at theheadworks,wherechlorineisdosed.Thereisno Tankinthesystem.

Pipeline Length:~40.45km

Pipe Material:HDPE(PE100/PN6)

Minimum pipe dia.90mm(OD);

Topography: Flat terrain, node elevations consideredzero

In the WDN, the OHSR is located at the Headworks site asymmetrically with respect to the command area a

commonbuthydraulicallydisadvantageoussituationinrural settings, dictated by land availability rather than optimal networkgeometry.

The projected design population of the WDN for the year 2050is15,277persons.Consideringapercapitademandof 55litresperday(LPCD)andaccountingfor10%distribution losses,thetotalwaterdemandoftheWDNisestimatedat 924kilolitresperday(kLD), equivalentto10.70litresper second(LPS).

Forhydraulicmodelling,nodaldemandswereapportioned proportionally within each village to represent spatially distributedconsumptionpatterns.Thenetworkcomprises 486 demand nodes connected by a pipeline system of approximately40.5kminlength.Undertheseconditions,the WDNischaracterizedbyacomparativelylowunitdemand intensity,whichhasdirectimplicationsforflowvelocities, residencetimes,andconsequently,waterqualitydynamics.

HydraulicsimulationsarecarriedoutinEPANET2.2using Hazen–WilliamsformulaconsideringC=145.TheOHSRis assumedtoprovideaheadof16m,ensuringaminimumof7 mpressureatalldemandnodes.

Asingleperiodsimulationwithademandmultiplierof3is first conducted to size the network and ensure pressure adequacyduringpeakconditions.Thisestablishesastable hydraulicbaseline.

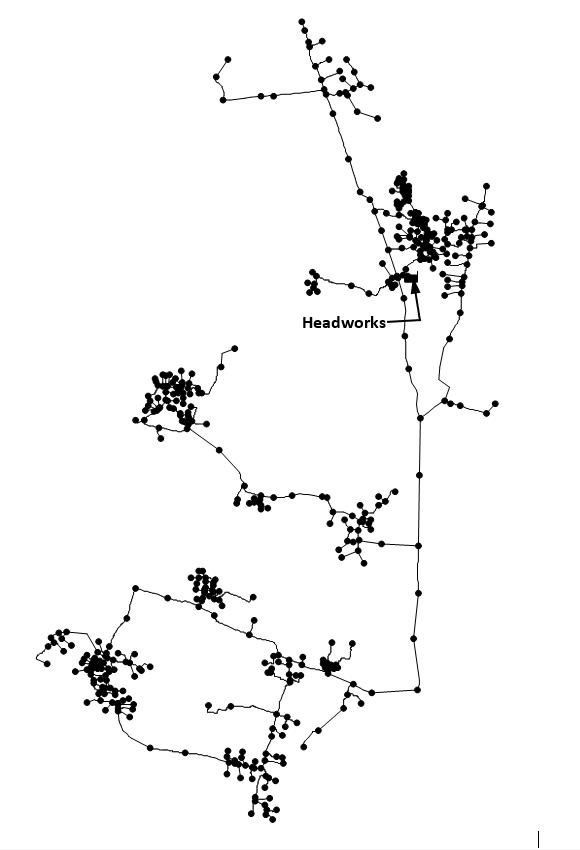

ThenetworklayoutisshownintheFig-1andnetworkdata arepresentedintheTable-4andTable-5.

ForthehydraulicanalysisunderEPS,diurnalpeakingfactors (PF) have been adopted for the Balagarh distribution network,assuggestedbySoumitraGanguly(2025).These factors,whichrepresentvariationsindemandacrossa24hourcycle,wereappliedconsistentlyatalldemandnodesto simulaterealisticfluctuationsinconsumption.Theadopted valuesarepresentedinTable-1,whichformsthebasisfor subsequenthydraulicandwater-qualityanalyses.

Table – 1 : HourlyPeakingFactor

PeakingFactor

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

To investigate the influence of chlorine dosage and decay kinetics under variable hourly demands in EPS, a water qualityanalysiswascarriedoutfortheBalagarhdistribution network using the same peaking factors as applied in the present study (Soumitra Ganguly, 2025). Initial chlorine doses of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mg/L were simulated under two decayscenarios:

Scenario 1: kb =-1.2/day,kw =-0.12/m/day

Scenario 2: kb =-0.6/day,kw=-0.06/m/day

ThecoefficientsinScenario1wereselectedbased on published literature (R. Gupta et al., 2012), whereasScenario2employedreducedvalues(50% ofScenario1)toaccountformorefavorabledecay conditions.

ThesimulationresultsindicatethatunderScenario1,even withaninitialchlorinedoseof5mg/L,asignificantnumber of nodes recorded residual concentrations below the minimum threshold of 0.2 mg/L throughout the diurnal cycle.Atthelowestdose(1mg/L),nearlyhalfofthenetwork exhibitedresidualsbelow0.2mg/L.Conversely,inScenario 2, most nodes-maintained residuals above 0.2 mg/L for doses≥2mg/L

Comparative evaluation between the two scenarios highlightssubstantialdifferencesinresidualconcentrations, particularlyatdistalnodes.Thisclearlydemonstratesthat chlorinepersistenceisstronglygovernedbyresidencetime, reinforcing its role as a critical parameter in modelling chlorine decay in distribution systems and justifies this study.

TheageofwaterinaWDNrepresentsthetimeelapsedsince a parcel of water entered the system (from source or reservoir) until it reaches a given node or segment. This metricisvaluableforunderstandinghow“stagnant”zones develop,estimatingresidencetimes,andassessingrisksof microbialgrowthorchemicalby-productformation.

Wateragecannotbemeasureddirectlybutcanbeestimated through hydraulic models (Fernando G-Avila et al., 2024) Since every WDN has unique features, there are no fixed thresholds for water age; however, lower values are desirable.Keyfactorsinfluencingwaterageincludewater demand, distance from reservoirs, network configuration, andpipesizing.Strikinga balancebetweenwaterageand pressure is essential to maintain safe and reliable water supply(BenBurkhartandRobertJanke,2023,M.Pateliset al.,2020)

EPS with variable demand patterns allows for dynamic estimation of water age across the day, capturing the influenceofdiurnalconsumptionandstorageturnover.Low wateragevalues,typicallyobservednearsourcesorunder peakdemandconditions,indicaterapidturnoverandhigher probabilityofmaintainingdisinfectantresiduals.Conversely, high water age values, common in peripheral nodes, oversizedpipes,suggestprolongedresidencetimesthatmay leadtodisinfectantdecay,microbialregrowth,andoverall deteriorationofwaterquality.

InatypicalWDN,wateragemayvaryfromasingledayto severaldays(FernandoG-Avilaetal.,2024),withstudiesin theUnitedStatesreportinganaveragerangeofaboutoneto threedays(N.Kourbasisetal.,2020).

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

In EPANET 2.2, water entering a source node such as a reservoirortankisassignedanageofzeroandtheelapsed travel time is tracked as it moves through pipes and junctions.Atjunctions,thewaterageiscomputedasaflowweighted average of all incoming links, while tanks accumulatewaterofdifferentagesaccordingtotheirinflow and mixing conditions. At each simulation hour, EPANET computesthewaterageateverynodeinthesystem.

Water age analysis provides a simple but powerful diagnostictoolinEPANET2.2,inconjunctionwithchlorine decaymodeling,toassessdistributionsystemperformance andidentifyoperationalordesigninterventionsnecessaryto safeguarddrinkingwaterquality(Rossman,2020).

EPANET 2.2 supports age-tracking (nonreactive tracer) analyses, meaning it does not simulate chemical transformationsorreactionsduringtheagecalculationitself (unlessfurtherreactionmodelsareactivated).Forwaterage analysis using EPANET, EPS is essential, so that temporal accumulation and mixing of flows can be captured over hoursordays.Itissuggestedthatthesimulationdurationfor thewaterageanalysismustbelongenoughforwateragesto evolvetowardquasi-steadyprofiles(AgnieszkaT.,2022)

UsingEPANET2.2onecanviewwateragespatiallyonthe network map (color-coded), or plot time‐series of age at selectednodesorstorageelements.Atthesametimeonecan getAveragewaterageandMaximumwaterageofaWDN.

During single period hydraulic simulation, extremely low flowvelocitieswereobservedattheterminalbranchesofthe network, where stagnation effects are likely to influence residencetimeandwaterquality.Tounderstandthereason behind the high residence time therefore, two analytical schemes were designed to evaluate the WDN’s hydraulic behaviorundervaryingoperatingconditions.

Case-1:EPSwithdiurnalPeakingFactors(Table-1), for96hsimulation

Case-2:TwosimplifiedEPSscenarioswithconstant PeakingFactorsforeachhourfor72hsimulation.

Scenario-1:PF=1(flatday)

Scenario-2:PF=3(uniformpeakload)

Case-1 characterizes the whole-network temporal behaviour

Case-2 isolates travel-time/velocity effects along a representativepath.

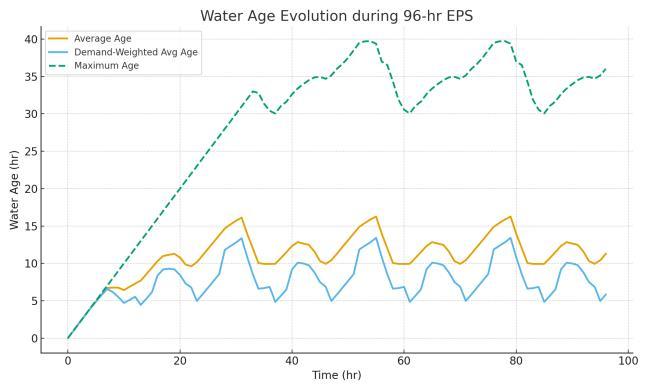

Water age analysis was carried out for Case-1: EPS with diurnalPeakingFactors(Table-1)for96hdurationandthe resultduring73 to96hsimulationperiod ispresented in Table-2.

The Average AGE of water is the mean of all these node values It tells on average, how long has the water in the network been resident since leaving the source? It’s a system-wide indicator of freshness. A lower average age usuallymeansgoodturnoverandlowstagnationrisk.

The Maximum AGE istheoldestwaterfoundanywherein the network at that time. This value highlights the worstcasestagnationzone.

Table-2 : AGEAnalysisResultsofBalagarhNetwork

of water during 73 to 96 Hrs. simulation

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

TheAverageAGEandMaximumAGEofwaterispresentedin Table-2during73to96hourssimulation period.Average AGEiscalculatedintwodifferentaspects:(i)plainaverage and(ii)demand-weightedaverage.Maximum,minimumand average of Average AGE, Maximum AGE and demandweightedaveragearealsopresentedinthetable.

System freshness vs. hotspots: Meannetworkwaterageis seentobemoderate(~12h),buthotspotspersistwithages ~30–40 h, implying peripheries experience >1 day residence.Undersingle-pointchlorination,suchwaterages are likely incompatible with maintaining ≥0.2–0.3 mg/L residual chlorine at terminal nodes without booster strategiesandishighlightedinthestudydonebySoumitra Ganguly,2025.

Morning peak effect: ThehighestAverageAge(16.26hat 79h)coincideswiththelargest“DemandAvg.”Aplausible interpretationisbulkflushingofolderperipheralwaterinto thenetworkduringthemorningramp,temporarilyraising the network-average age before fresher water propagates andtheaveragedeclines.

Recovery: Afterthepeak,AverageAgedecreases(hrs80–86), reflecting increased turnover and ingress of younger water from the source; Maximum Age remains elevated, signalingpersistentpocketswhereturnoverstayspooreven asthenetworkrefresheselsewhere.

Design/operation signal: Thecombinationofarelatively modest systemwide average but high and sticky maxima suggests structural limitations (layout/diameter) rather thanpurelyoperationaltiming aclassicsignatureoftreelikeruralnetworkswithterminaloversizing.

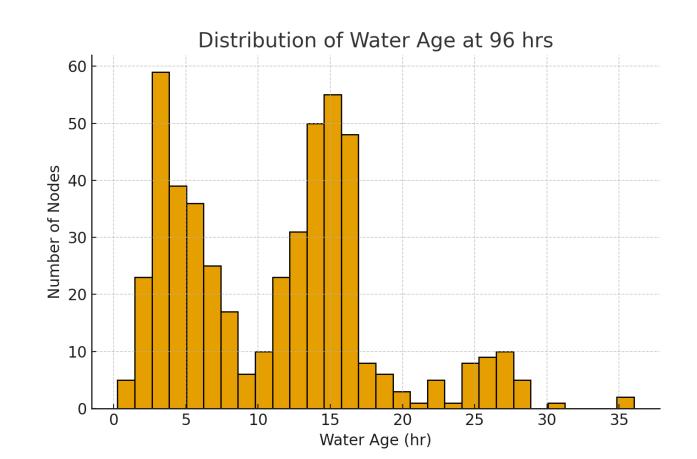

Figure–2 showswaterageevolutionand Figure–3 shows distributionofnumbersofnodesandcorrespondingwater ageat96-hrEPS

Performing water age analysis with hourly variations in demand generates highly complex outcomes. To simplify interpretation, two representative scenarios were considered:

Scenario1:Equalpeakingfactorof1foreachhour,

Scenario2:Equalpeakingfactorof3foreachhour.

WaterageanalysiswasthencarriedoutunderEPS,allowing wateragetobetrackedacrosstheentiresystem.

6.2.1 Case-2 Water Age Analysis Result

FordetailedillustrationofCase-2,apipelinestretchfromthe OHSR(R-1)toaterminaljunction(J365)wasselected.While severalintermediatejunctionsexistbetweenR-1andJ365, the analysis focused on those locations where pipe diameters changed. Results for both scenarios are summarizedinTable-3,showingdistance,traveltime,and averagevelocitybetweentheselectedjunctions.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net

In Table-3, the last row (Column 3) corresponds to a terminalpipeof90mmOD(80.4mmID)betweenjunctions J362 and J365, with a length of 785 m. For this segment, Columns(5)and(6)indicateatraveltimeof17.73handan averagevelocityof0.012m/satPF=1.Incontrast,Columns (7) and (8) show a reduced travel time of 5.91 h and an increased average velocity of 0.037 m/s at PF = 3. These results highlight that terminal branches experience extremelylongresidencetimes(≈17.7hfor785matPF=1), which improve but remain significant even under higher demandconditions(≈5.9hatPF=3).

Table – 3: AGEAnalysisusingequalPeakingFactors

Junctions Pipe ValuesbetweenJunctions From To

6.2.2 Case–2 Discussion of Result

Terminal bottleneck: Segments down to ~100 mm ID behaveacceptablyforalow-demandWDN,butthe80.4mm ID terminal shows abnormally high travel time and extremely low velocity, explaining the stubborn high maximumwateragesseeninCase-1.

Sensitivity to demand: Uniformly increasing demand (PF=3)improvesvelocityandreducestravel timeby~3×, yettheterminalbranchstillexhibitsmulti-hourresidence, indicating geometry-driven stagnation risk that cannot be solvedbyoperationalone.

7. RECOMMENDATIONS

OperationalStrategies

Chlorination should be validated against field residualmeasurements;incaseswhereresidualsare consistently low at peripheral nodes, booster chlorination or staged dosing may be introduced,

with due consideration of disinfection by-product (DBP)risks.

Diurnal demand patterns require refinement by recalibrating peaking factors using metered consumptiondata,therebyimprovingtheaccuracy ofextendedperiodsimulations(EPS).

Terminaltreeconfigurationsshould,wherefeasible, be converted into looped networks to reduce effectivetravelpathsandmitigatestagnation.

In networks where regulatory requirements mandate oversized diameters under low demand conditions,hydraulicrebalancingmaybeachieved throughlocalizedsmaller-IDinserts,orificeplates,or pressure/flowcontrolvalves(PRVs/FCVs),provided these align with applicable standards and maintenance practices (Menelaos Patelis et al., 2020).

Optimal siting of overhead service reservoirs (OHSRs)shouldprioritizecentralorzonalplacement tominimizeconveyancedistancestoterminalnodes.

District metered areas (DMAs) equipped with pressure and residual chlorine loggers should be established at peripheral locations, and periodic waterageanalysesshouldbeintegratedwithfield data to support adaptive operational management (NikolaosKourbasisetal.,2020).

TheBalagarhWDNexhibitsmoderatemeanage(~12h)but persistent high maximum ages (~30–40 h), implying periphery zones with >1 day residence under single-point chlorination.

Terminalgeometry(≈80.4mmID,longreach,lowdemand)is the dominant driver of stagnation; even uniform high PF (PF=3)leavesmulti-hourresidence.

The above findings indicate persistent risk of low chlorine residuals at the periphery under single-point chlorination.

Under single-point chlorination, such water ages are likely incompatible with maintaining ≥0.2–0.3 mg/L residual chlorine at terminal nodes without booster strategies and is highlighted in the study done by Soumitra Ganguly, 2025.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Sustainable quality control requires structural (looping/rebalancing) plus operational (flushing/booster dosing)measures,guidedbyAGE+chlorinedecaymodelling andfieldresidualmonitoring.

While Water Age analysis quantifies the residence time of waterthroughoutthedistributionsystem,itsimplicationsfor disinfectant persistence will become evident only when combinedwithWaterQualityAnalysis(WQA).

WaterageandWQAtogetherprovideamoreholisticpicture of how chlorine residuals behave across the network, especiallyinlow-demandruralsystems, and this integrated assessment will be taken up as part of future work

[1] Ababu T. T, Tesfamariam Y. D, Gabriel C. B, and Stanley J. N. (2019). “A Mathematical Model for VariableChlorineDecayRatesinWaterDistribution Systems.” Modelling and Simulation in Engg Vol 2019,ArticleID5863905.

[2] Agnieszka TRĘBICKA, (2022). “Modeling of water agechangesInwaterdistributionsystems Intime and space.” EKONOMIA, SRODOWISKO • 4(83) • 2022

[3] B Kowalska,D Kowalski,andAnnaMusz (2006). “Chlorine decay in water distribution systems.” EnvironmentProtectionEngineering,Vol.32,2006, No.2.

[4] Ben Burkhart and Robert Janke, (2023). “UnderstandingWaterAgeinDistributionSystems With EPANET.”J Am Water Works Assoc. 2023 March06;115(2):24–34.doi:10.1002/awwa.2052.

[5] Denis Nono., Phillimon T. O., Innocent B. and Bhagabat P P. (2019). “Assessment of probable causesofchlorinedecayinwaterBOTSWANA.”ISSN 1816-7950(Online)=WaterSAVol.45No.2April 2019.

[6] FernandoG-Avila,GeovannaA-Barbecho,MelisaEBustamante,LorgioV-Gonzales,EstebanS-Cordero, RitaC-Tores,HoracioG-Ortega,(2024).“Waterage indrinkingwaterdistributionsystems:Acasestudy comparing tracers and EPANET.” Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 10(2024)100817, Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2024.100817

[7] Hossein Shamsaei, Othman Jaafar, Noor Ezlin Ahmad Basri, (2013). “Effects Residence Time to WaterQualityinLargeWaterDistributionSystems.”

ScientificResearch.Engineering,2013,5,449-457 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/eng.2013.54054

[8] John J. Vasconcelos, Lewis A. Rossman, Walter M. Grayman, Paul F. Boulos, and Robert M. Clark. (1997).“KineticsofChlorineDecay.”Article,AWWA –July1997.

[9] Julius Caesar, Kwio-Tamale, and Charles Onyutha. (2024) “Influence of physical and water quality parameters on residual chlorine decay in water distributionnetwork.”Heliyon10(2024)e30892.

[10] MenelaosPatelis,VasilisKanakoudisandAnastasia Kravvari, (2020). “Pressure Regulation vs. Water AginginWaterDistributionNetworks.”Water2020, 12, 1323; doi:10.3390/w12051323 www.mdpi.com/journal/water.

[11] Nikolaos Kourbasis, Menelaos Patelis, Stavroula TsitsifliandVasilisKanakoudis.(2020).“Optimizing Water Age and Pressure in Drinking Water DistributionNetworks.”Environ.Sci.Proc.2020,2, 51;doi:10.3390/environsciproc2020002051

[12] P.R.BhaveandR.Gupta.(2006). Analysis of Water Distribution Networks. Narosa Publishing, 2006, 388-416.

[13] R. Gupta, S. Dhapade, S. Ganguly and P. R. Bhave. (2012).“Waterqualitybasedreliabilityanalysisfor water distribution networks.” ISH Journal of HydraulicEngineeringVol.18,No.2,June2012,80–89.

[14] RoopaliV.GoyalandH.M.Patel. (2015).“Analysis of residual chlorine in simple drinking water distributionsystemwithintermittentwatersupply.” Appl Water Sci (2015) 5:311–319 DOI 10.1007/s13201-014-0193-7.

[15] RossmanLewisA.(2020).EPANET2.2UserManual. U.S.EnvironmentalProtectionAgency.

[16] SoumitraGanguly.(2025)“AssessmentofChlorine Residuals in a Rural Water Distribution Network withEPANET2.2:ImpactofvaryingChlorineDose and Decay Coefficients.” International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET), Volume:12Issue:08,Aug2025,474-483

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

WaterDistributionNetworkData–NodeTable

Node LPM Node LPM Node LPM Node LPM

J1 0.321 J51 0.643 J101 0.184 J151 1.908

J2 1.056 J52 0.367 J102 0.597 J152 1.060

J3 1.561 J53 0.826 J103 2.571 J153 1.749

J4 1.607 J54 1.377 J104 2.984 J154 1.060

J5 0.184 J55 0.872 J105 1.745 J155 2.755

J6 1.102 J56 0.826 J106 1.974 J156 1.484

J7 1.515 J57 1.791 J107 1.607 J157 3.126

J8 0.551 J58 0.689 J108 3.030 J158 1.590

J9 0.689 J59 1.148 J109 5.234 J159 2.225

J10 0.872 J60 1.515 J110 4.316 J160 1.007

J11 1.423 J61 0.459 J111 2.525 J161 2.914

J12 0.275 J62 0.643 J112 0.918 J162 1.855

J13 0.918 J63 0.551 J113 1.791 J163 1.643

J14 0.551 J64 0.230 J114 0.689 J164 1.272

J15 0.321 J65 0.826 J115 2.020 J165 1.537

J16 1.607 J66 0.275 J116 0.918 J166 1.113

J17 0.781 J67 0.643 J117 1.928 J167 1.855

J18 0.643 J68 0.184 J118 1.332 J168 0.954

J19 1.837 J69 0.459 J119 2.525 J169 1.484

J20 2.250 J70 0.643 J120 1.377 J170 0.477

J21 2.250 J71 0.505 J121 1.102 J171 0.742

J22 1.745 J72 0.230 J122 1.286 J172 1.960

J23 1.056 J73 1.423 J123 8.520 J173 0.477

J24 0.918 J74 0.275 J124 8.611 J174 0.742

J25 0.413 J75 1.332 J125 4.280 J175 1.272

J26 0.321 J76 0.275 J126 5.645 J176 0.795

J27 2.938 J77 0.597 J127 4.218 J177 2.066

J28 3.581 J78 0.184 J128 1.799 J178 0.636

J29 3.306 J79 0.459 J129 1.091 J179 0.848

J30 0.367 J80 1.469 J130 2.433 J180 1.749

J31 1.240 J81 0.275 J131 1.930 J181 1.325

J32 0.459 J82 0.230 J132 1.594 J182 1.378

J33 0.964 J83 0.781 J133 4.530 J183 1.378

J34 0.367 J84 0.459 J134 1.762 J184 0.795

J35 0.367 J85 1.056 J135 5.029 J185 2.861

J36 3.857 J86 0.367 J136 1.332 J186 2.172

J37 1.561 J87 0.321 J137 2.893 J187 1.166

J38 1.699 J88 0.964 J138 3.719 J188 2.967

J39 1.240 J89 0.413 J139 4.637 J189 1.088

J40 0.321 J90 0.918 J140 2.250 J190 1.323

J41 0.275 J91 0.321 J141 0.476 J191 0.501

J42 0.184 J92 0.643 J142 5.140 J192 1.422

J43 0.781 J93 0.735 J143 1.166 J193 2.505

J44 0.826 J94 0.964 J144 2.702 J194 1.055

J45 0.230 J95 0.321 J145 3.020 J195 0.835

J46 0.689 J96 0.551 J146 1.007 J196 1.626

J47 1.010 J97 0.643 J147 6.729 J197 0.791

J48 0.321 J98 0.964 J148 3.497 J198 0.395

J49 0.643 J99 0.321 J149 3.179 J199 1.934

J50 0.275 J100 0.689 J150 1.219 J200 0.703

Table – 4: NodeData(Contd.)

WaterDistributionNetwork

J201 1.934 J251 0.483 J301 3.118 J351 0.864 J202 1.494 J252 1.318 J302 3.005 J352 0.376

J203 0.923 J253 0.439 J303 1.315 J353 0.563 J204 0.483 J254 0.527 J304 2.479 J354 0.451 J205 1.934 J255 1.099 J305 1.014 J355 0.714 J206 1.626 J256

J260

J218

J222

J223

J268

J269

J270

J271

J272

J273

J224 0.308 J274

J315

J318

J321

J322

J324

J225 0.923 J275 0.571 J325

J365

J366

J368

J369

J370

J371

J372

J373

J374

J375 0.150

J226 0.659 J276 0.879 J326 4.996 J376 1.465

J227 0.747 J277

J228 0.395 J278

J327

J328

J229 0.835 J279 0.308 J329

J230 4.878 J280 0.967 J330

J377

J378

J379

J380 0.751 J231 1.230 J281 0.747 J331

J381 1.653

J232 0.264 J282 0.527 J332 0.413 J382 0.563

J233 5.053 J283 0.835 J333

J383 1.540 J234 4.394 J284 0.483 J334

J384

J235 0.527 J285 1.099 J335 0.413 J385 0.413

J236 0.703 J286 0.747 J336

J386 0.601 J237 0.571 J287

J337

J238 1.186 J288 1.626 J338

J387 0.826

J388 0.601 J239

J289

J339

J389 0.413 J240

J290

J340

J390

J241 1.099 J291 0.483 J341 0.413 J391 0.413

J242 0.923 J292 0.703 J342 0.376 J392 0.263

J243 2.505 J293 1.670 J343 1.127 J393 0.601 J244 0.395 J294 0.659 J344 0.225 J394 0.451

J245 0.835 J295 1.977 J345 0.601 J395 0.488

J246 0.923 J296 0.264 J346 0.526 J396 0.714

J247 3.603 J297 0.766 J347 1.465 J397 0.488

J248 0.747 J298 3.145 J348 0.413 J398 0.751

J249 2.505 J299 5.109 J349 0.939 J399 0.451

J250 0.571 J300 3.381 J350 0.488 J400 0.751

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

WaterDistributionNetworkData–Node

Node LPM Node LPM Node

J401 0.413 J423 3.531 J445 1.052 J467 0.601

J402 0.263 J424 0.751 J446 0.601 J468 1.352

J403 0.751 J425 1.089 J447 0.826 J469 1.803

J404 1.315 J426 0.789 J448 0.338 J470 0.639

J405 0.751 J427 1.052 J449 1.352 J471 5.710

J406 0.413 J428 0.413 J450 0.451 J472 1.615

J407 0.714 J429 0.826 J451 0.676 J473 0.488

J408 0.714 J430 0.751 J452 0.563 J474 0.601

J409 1.690 J431 0.676 J453 1.089 J475 4.283

J410 0.751 J432 4.508 J454 0.826 J476 1.766

J411 0.864 J433 4.095 J455 0.751 J477 3.193

J412 0.714 J434 3.231 J456 1.540 J478 1.615

J413 0.563 J435 0.639 J457 0.826 J479 0.188

J414 1.202 J436 0.676 J458 2.517 J480 0.225

J415 1.352 J437 0.639 J459 0.601 J481 1.202

J416 0.263 J438 0.789 J460 0.338 J482 0.789

J417 0.751 J439 0.301 J461 1.165 J483 1.202

J418 1.277 J440 1.277 J462 2.141 J484 0.376

J419 0.413 J441 0.714 J463 1.803 J485 1.352

J420 0.902 J442 1.089 J464 1.352 J486 0.601

J421 1.428 J443 0.751 J465 0.376 J422 0.563 J444 0.338 J466 1.916

– 5: PipeData

P1 R-1 J1 20 251.4 P51 J43 J41 30

P2 J1 J2 35 251.4 P52 J53 J51

P3 J2 J3 45 98.6 P53 J39 J53

P4 J3 J4 135 80.4 P54 J54 J38 55

P5 J4 J5 20 80.4 P55 J57 J55 10

P6 J4 J6 25 80.4 P56 J59 J57 15

P7 J6 J7 35 80.4 P57 J57 J56 90 80. 4

P8 J7 J8 65 80.4 P58 J54 J59 40

P9 J7 J9 75 80.4 P59 J59 J58 80

P10 J6 J10 70 80.4 P60 J60 J54 60 98.

P11 J10 J11 25 80.4 P61 J60 J61 50 80. 4

P12 J11 J13 105 80.4 P62 J62 J60 60 98. 6

P13 J11 J12 30 80.4 P63 J65 J64 25 80. 4

P14 J10 J14 5 80.4 P64 J69 J68 20 80. 4

P15 J14 J15 35 80.4 P65 J67 J66 30 80. 4

P16 J14 J16 25 80.4 P66 J65 J63 65 80. 4

P18 J16 J17 90 80.4 P68 J67 J65 5 80.

P17 J16 J18 70 80.4 P67 J70 J69 30 80. 4

P19 J19 J2 45 251.4 P69 J62 J70 5 80.

P20 J19 J20 15 125.4

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

J124 J125 90 80.4 P176 J174 J175 25 80.4

P126

P127 J125 J126 270 80.4 P177 J175 J172 70 80.4

P128 J126 J127 205 80.4 P178 J172 J170 50 80.4

P129 J127 J128 150 80.4 P179 J169 J181 40 80.4

P130 J123 J137 75 80.4 P180 J180 J177 10 0 80.4

P131 J133 J132 100 80.4 P181 J177 J175 30 80.4

P132 J137 J136 150 80.4 P182 J181 J180 10 80.4

P133 J134 J135 110 80.4 P183 J188 J187 11 5 80.4

P134 J135 J133 150 80.4 P184 J183 J185 13 5 80.4

P135 J130 J129 65 80.4 P185 J186 J184 80 80.4

P136 J133 J131 40 80.4 P186 J169 J188 55 80.4

P137 J131 J130 85 80.4 P187 J188 J186 12 5 80.4

P138 J137 J135 105 80.4 P188 J185 J182 14 0 80.4

P139 J19 J138 150 225.4 P189 J186 J185 10 80.4

P140 J138 J139 270 225.4 P190 J141 J189 40 5 201.8

P141 J140 J139 255 225.4 P191 J190 J189 52 0 201.8

P142 J140 J141 370 225.4 P192 J190 J191 26 5 125.4

P143 J141 J142 225 112 P193 J191 J192 16 5 125.4

P144 J143 J142 45 80.4 P194 J192 J193 75 80.4

P145 J144 J143 70 80.4 P195 J193 J194 13 0 80.4

P146 J145 J144 195 80.4 P196 J193 J195 10 0 80.4

P147 J146 J145 100 80.4 P197 J192 J196 75125.4

P148 J142 J147 460 98.6 P198 J201 J200 80 80.4

P149 J147 J148 205 98.6 P199 J199 J198 45 80.4 P150 J148 J149 145 98.6 P200 J201 J199 85 80.4

Table – 5: PipeData(Contd.)

P251 J249 J250

P202 J196 J201 60 80.4 P252 J249 J264 10 0 98.6

P254 J263 J264

J258 J257

P206 J210 J209 55

P256 J255 J253

P207 J213 J211 95 80.4 P257 J259 J260 85

P208 J202 J213 20 80.4 P258 J252 J251 60 80.4

P209

P212 J208 J206 130 80.4 P262 J252 J265 40 98.6

P213 J206 J205 60 80.4 P263 J262 J260 20 98.6

P214 J205 J203 110 80.4 P264 J260 J258 5 98.6

P215 J214 J202

P218 J215 J217 110

P268 J270 J271 85 80.4

P219 J217 J218 35 125.4 P269 J269 J266 11 5 80.4

P220 J219 J218 225 125.4 P270 J271 J265 15 80.4

P221 J219 J220 135 125.4 P271

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

P332 J330 J331 40 80.4 P382 J378 J376 85 80.4

P333 J332 J330 25 80.4 P383 J376 J375 20 80.4

P334 J333 J332 30 80.4 P384 J383 J382 80 80.4

P335 J334 J336 315 80.4 P385 J384 J373 45 80.4

P336 J339 J340 40 80.4 P386 J385 J384 55 80.4

P337 J338 J337 65 80.4 P387 J398 J397 65 80.4

P338 J338 J336 35 80.4 P388 J400 J399 60 80.4

P339 J333 J340 40 80.4 P389 J386 J387 85 80.4

P340 J340 J338 40 80.4 P390 J388 J387 30 80.4

P341 J336 J335 60 80.4 P391 J390 J391 30 80.4

P342 J345 J344 30 80.4 P392 J393 J394 20 80.4

P343 J342 J343 50 80.4 P393 J394 J396 20 80.4

P344 J349 J348 55 80.4 P394 J388 J394 20 80.4

P345 J347 J346 75 80.4 P395 J401 J403 45 80.4

P346 J353 J352 55 80.4 P396 J391 J393 25 80.4

P347 J355 J354 60 80.4 P397 J400 J401 15 80.4

P348 J351 J350 65 80.4 P398 J396 J398 15 80.4

P349 J347 J343 50 80.4 P399 J398 J400 25 80.4

P350 J343 J341 60 80.4 P400 J403 J384 30 80.4

Table – 5: PipeData(Contd.)

DistributionNetworkData–PipeTable

P401 J395 J396 70

P445 J443 J444 45

P402 J392 J393 35 80.4 P446 J445 J442 45 98.6

P403 J403 J402

P447 J445 J446

P407 J414 J413 80 80.4 P451 J462 J449 70

P408 J420 J419 55 80.4 P452 J453 J452 75 80.4

P409 J411 J410 60 80.4 P453 J451 J450 65 80.4

P410 J417 J418 65 80.4 P454 J459 J461 85 80.4

P411 J415 J414 45 80.4 P455 J458 J457 11 5 80.4

P412 J407 J410 45 80.4 P456 J456 J454 75 80.4

P413 J414 J412 40 80.4 P457 J454 J453 40 80.4

P414 J412 J411 55 80.4 P458 J462 J461 35 80.4

P415 J409 J415 50 80.4 P459 J453 J451 35 80.4

P416 J415 J418 85 80.4 P460 J458 J462 20 0 80.4

P417 J418 J420 20 80.4 P461 J456 J458 40 80.4

P418 J420 J404 50 80.4 P462 J461 J460 50 80.4

P419 J409 J408 100 80.4 P463 J455 J456 10 5 80.4

P420 J416 J417 40 80.4 P464 J449 J463 65 98.6

P421 J407 J406 55 80.4 P465 J463 J464 13 5 80.4

P422 J409 J421 85 80.4 P466 J464 J465 50 80.4

P423 J421 J422 80 80.4 P467 J463 J466 45 98.6

P424 J430 J429 60 80.4 P468 J466 J467 85 80.4

P425 J426 J427 110 80.4 P469 J466 J468 14 0 98.6

P426 J425 J427 30 80.4 P470 J468 J469 55 98.6

P427 J423 J425 25 80.4 P471 J470 J469

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 © 2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified

P439 J438

P440

P442 J441 J440

P443 J442 J440

P444 J442 J443

J485

L=Lengthofthepipeinm. Diametershownareinternaldiameter ofpipelineinmm.