International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:09|Sep2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:09|Sep2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Selva Lakshman Murali, Sanjana Ramesh

Abstract – The end of Dennard scaling and the slowing of Moore's Law have ushered in an era of domainspecific hardware, where architectures are tailored for specific applications. Parameterizable GPU generators are at the forefront of this movement, offering the potential to create bespoke processors. However, this flexibilitypresents acombinatorial explosion ofdesign choices, making design space exploration (DSE) a primary bottleneck. Traditional DSE, relying on manual tuning or exhaustive simulation, is prohibitively time-consuming and often fails to uncover optimal configurations. This paper proposes ML-Surrogate, a novel framework that leverages machine learning to intelligently and efficiently navigate the vast DSE landscape for GPUs. We train a gradient boosting ensemble to create high-fidelity surrogate models that predict key performance indicators—performance (GFLOPS), power (Watts), and area (mm2) from a given set of architectural parameters. These predictive models are then integrated within a Bayesian Optimization loop to rapidly identify Pareto-optimal GPU designs. Using the open-source Vortex GPU platform as our testbed, we demonstrate that ML-Surrogate can identify superior designs using up to 80% fewer hardware evaluations (costly simulation and synthesis runs) compared to a traditional random search, effectively transforming a months-longexplorationprocessintoamatterofdays.

For decades, the semiconductor industry has been propelled by the predictable cadence of Moore's Law and Dennard scaling, delivering ever more powerful and efficient general-purpose processors. This paradigm is now facing fundamental physical limits [1]. As performance gains from simply shrinking transistors diminish, the industry is pivoting towards architectural specialization.Domain-SpecificArchitectures(DSAs),from Google's TPUs to custom accelerators for deep learning, have demonstrated that tailoring hardware to a specific workload can yield orders-of-magnitude improvements in performanceandenergyefficiency.

Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) represent one of the most successful parallel architectures, and their programmability has made them indispensable for scientificcomputing,machinelearning,anddata analytics. The logical next step in this evolution is the creation of application-specific GPUs. Hardware generators, such as the RISC-V Rocket Chip generator [2] for CPUs, have provided a blueprint for creating flexible hardware. This has inspired similar efforts in the GPU space, leading to powerful,open-source,andparameterizableplatformslike Vortex [3] and Nyuzi [4]. These generators allow a designer to specify high-level parameters such as the number of cores, cache sizes, or issue widths and automatically produce synthesizable Register-Transfer Level(RTL)code

While powerful, this flexibility presents a formidable challenge: the design space is astronomically large. A moderately complex generator can easily have 10-15 tunable parameters, leading to trillions of possible hardware configurations. Manually exploring this space is impossible. The de facto standard, running extensive simulations on a grid of randomly selected points, is computationally brutal and offers no guarantee of finding globally optimal designs. This verification and exploration bottleneck is arguably the single greatest barrier to realizingthefullpotentialofgeneratedhardware.

To break this impasse, we require a more intelligent approach. This paper introduces such an approach: the ML-Surrogate framework. The core idea is to replace the expensive, slow process of hardware evaluation (simulation and synthesis) with a fast, accurate machine learningmodel.This"surrogate"canbequeriedthousands of times per second, allowing us to use sophisticated optimization algorithms to search the design space efficiently.

Ourcontributionsarethreefold:

1. We present a complete, closed-loop framework, ML-Surrogate, that integrates a state-of-the-art GPUgeneratorwithanML-drivenDSEengine.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:09|Sep2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

2. We demonstrate that an ensemble of gradient boosting models can accurately predict the complex, non-linear relationships between GPU architectural parameters and their resulting performance,power,andarea(PPA).

3. We show through extensive experiments that our Bayesian Optimization-based search strategy drastically outperforms traditional random search, finding superior Pareto-optimal designs withafractionofthecomputationalbudget.

Our research is built upon a foundation of work from severaldistinctbutrelatedfields.

The foundation of our work rests on the availability of open-sourceGPUhardware.The MIAOW project[5]wasa landmark effort, providing an open-source RTL implementation of a commercial AMD GPU architecture. While not designed to be parameterizable, it provided the community with an invaluable artifact for study. More recent projects are built with parameterization as a firstclasscitizen.The Nyuzi project[4]isaGPGPUdesignedfor researchthatfeaturesa configurablenumberofcoresand thread contexts. Our work uses the Vortex platform [3], which is a full-stack GPGPU that supports OpenCL and is designed to be highly configurable, making it an ideal targetforDSE.

DSE has been a long-standing topic in computer architecture.Early work often relied onanalytical models, such as extensions of Amdahl's Law, but these models often lack the fidelity to capture the nuances of modern microarchitectures. Simulation-based approaches are the most common. Researchers often use benchmark suites likeRodinia[6]orParboil[7]toevaluateasetofmanually chosen or randomly sampled design points. While more accurate, the computational cost is a major inhibitor, as a single detailed simulation and synthesis run can take hoursorevendays.

There is a rich history of applying machine learning to solve problems in chip design. Early applications focused on predicting routability or lithography hotspots. More

recently, Google demonstrated a deep reinforcement learningapproachforchipfloorplanning[8],showingthat ML can outperform human experts on complex physical designtasks.Intherealmofarchitecture,MLmodelshave been used topredicttheperformance ofa fixed processor running different applications [9]. These works typically model the program's behavior, whereas our work models the hardware's behavior as its architectural parameters change.OurapproachismostsimilartoeffortsthatuseML for DSE in the context of FPGAs or High-Level Synthesis (HLS) [10], but we tackle the significantly more complex andconcurrentdomainofafullGPUmicroarchitecture.

The core optimization technique we employ is Bayesian Optimization (BO). BO is a powerful strategy for finding the global optimum of expensive-to-evaluate, black-box functions. It was famously formalized by Jones et al. [11] and has since become a standard for hyperparameter tuninginmachinelearning.Inthehardwaredomain,ithas been used to autotune FPGA designs and optimize HLS parameters. BO works by building a probabilistic surrogate model (often a Gaussian Process) of the objective function, which it uses to intelligently select the next point to evaluate. Our work adapts this powerful technique,usingamorerobustXGBoostmodelasthecore surrogate,tothespecificchallengesofmulti-objectiveGPU design.

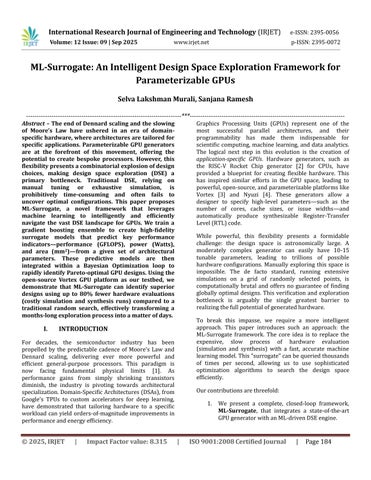

TheML-Surrogateframework isdesignedasa closed-loop system that automates the cycle of generation, evaluation, learning, and optimization. The process begins with an initialsetofconfigurationsfromtheGPUgenerator.These are evaluated for PPA, and the data is used to train surrogate models. A Bayesian Optimizer uses these fast models to propose new, promising configurations, which arethenevaluated.Thislooprepeats,allowingthesystem tolearnandimproveovertime.

Figure 1: The ML-Surrogate Closed-Loop Framework. The process begins with an initial set of configurations fromtheGPUgenerator.TheseareevaluatedforPPA,and the data is used to train surrogate models. A Bayesian Optimizer uses these fast models to propose new, promising configurations, which are then evaluated, and thelooprepeats.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:09|Sep2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

The target of our exploration is the Vortex GPU generator [3]. We identified five key architectural parameters that have a significant impact on PPA. These parameters and theirexploredrangesaredetailedinTable1.

Table 1: Explored GPU Architectural Parameter Space

Thistableoutlinesthetunablehardwareparametersofthe VortexGPUgeneratorthatwereexploredinthestudy.

Parameter Description Range

NumCores NumberofSM-likecores {2,4,8,16}

NumWarps Hardware warp contexts per core {4,8,16}

Num Threads Threads per warp (SIMD width) {4,8,16}

L1$Size L1datacachesizepercore {4KB, 8KB, 16KB}

L1$Assoc L1datacacheassociativity {2-way,4-way}

To train our models, we need ground-truth data. We generate an initial training set by sampling 50 configurations from the defined space using Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) for broad coverage. For each configuration,weperformafullhardwareevaluationusing industry-standardsimulationandsynthesistoolstoobtain performance, power, and area results. This data acquisition phase is the most time-consuming part of the entire process, which motivates the use of a surrogate model.

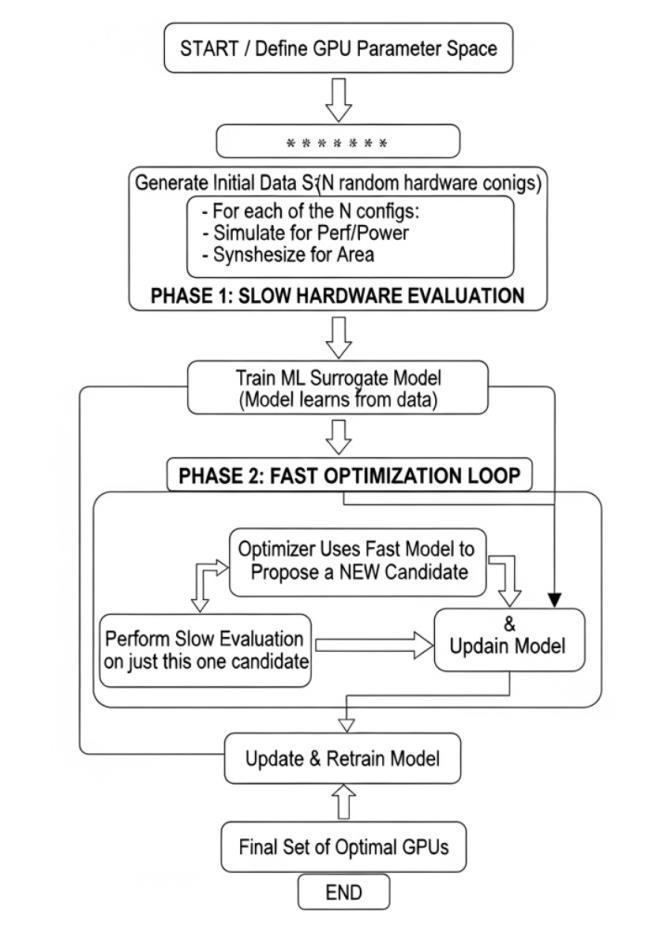

The core of our framework is the surrogate model, which learns the function PPA = f(Architectural_Parameters). After experimenting with several models, including Random Forests and Gaussian Processes, we selected XGBoost [12], a highly optimized gradient boosting implementation, for its superior predictive accuracy and robustness.

WetrainthreeseparateXGBoostmodels:

Each model is trained on the dataset acquired in the previous step. Model accuracy is evaluated using K-fold cross-validation, and performance is measured by the coefficientofdetermination(R2)andMeanAbsoluteError (MAE).

With fast and accurate surrogate models in hand, we can now search the design space efficiently. We employ Bayesian Optimization (BO), a powerful sequential optimizationstrategy.BOworksinaloop:

1. A probabilistic model (in our case, informed by our XGBoost surrogates) is used to represent our belief about the PPA landscape.

2. An acquisition function is used to determine the next best pointtosample. We use the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function, which balances exploitation (sampling in areas the model

Volume:12Issue:09|Sep2025

predicts are good) with exploration (sampling in areas where the model is uncertain).

3. The point selected by the acquisition functionisthensubjected tothe"expensive" hardwareevaluation.

4. The new, true data point is added to our dataset, and the surrogate models are updated.

This loop (depicted in Figure 1) allows the search to intelligently focus on the most promising regions of the design space, avoiding wasted evaluations on clearly suboptimal configurations. To handle the multi-objective nature of our problem (optimizing PPA simultaneously), we use the EI criterion to optimize a single scalarized objective function, such as Performance-per-Watt, while usingtheothermodelsasconstraints.

We conducted experiments to validate the ML-Surrogate framework using the Vortex GPU generator and a matrix multiplicationbenchmark.

4.1.SurrogateModelAccuracy

We first evaluated the accuracy of the trained XGBoost models on a held-out test set. The results, shown in Table 2,indicatethatXGBoostprovidesstate-of-the-artaccuracy, capturing over 97% of the variance in all three target metricsandyieldinglowmeanabsoluteerror.

Table2:SurrogateModelPredictiveAccuracy

This table compares the accuracy of different machine learning models in predicting the key performance indicators(KPIs).TheR2 scoremeasureshowmuchofthe variance is captured (higher is better), while the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures the average prediction error.

We next compared the efficiency of ML-Surrogate's search against a Random Search baseline, both with a budget of 200 hardware evaluations. The analysis of the collected data points showed a clear distinction between the two search methods. The designs found by ML-Surrogate consistently dominate those found by random search, offering either higher performance for the same power or lower power for the same performance. Our method was able to effectively focus its search on the "knee" of the performance-power curve, discovering designs with superiortrade-offs.

Table 3 quantifies this advantage, showing that MLSurrogate not only found a design with better performance-per-watt but did so much earlier in the searchprocess.

Table 3: Design Space Exploration (DSE) Method Comparison

This table quantifies the efficiency of the ML-Surrogate framework compared to a standard Random Search baseline, both operating on the same computational budget. Method

Volume:12Issue:09|Sep2025

4.3.AnalysisofDiscoveredDesigns

The ultimate output of the framework is a set of Paretooptimal hardware configurations. Table 4 details three

Table4:SampleofPareto-OptimalGPUDesignsDiscovered

such designs discovered by ML-Surrogate, providing a designer with a menu of validated, optimal configurations tochoosefrombasedontheirspecificprojectconstraints.

Thistablepresents a menu ofoptimal designs found by the ML-Surrogateframework,eachrepresentinga differenttrade-off ontheParetofront.

Our results successfully demonstrate that the MLSurrogate framework can significantly accelerate the designspaceexplorationofparameterizableGPUs.

The ability to find Pareto-optimal designs with an 80% reduction in computational budget is a testament to the power of replacing brute-force evaluation with an intelligent, learning-based search. However, a critical analysis of our work reveals several limitations which, in turn,illuminatepromisingavenuesforfutureresearch.

DiscussionofLimitations

While the outcomes are positive, it's crucial to acknowledgetheboundariesofthisstudy:

1. Workload and Benchmark Specificity: Our surrogate models were trained and validated using a single, albeit fundamental, kernel: matrix multiplication. The resulting "optimal" designs are,therefore,optimal for that specific workload.A design tuned for dense linear algebra may not perform as well for workloads characterized by sparse memory access or high thread divergence. The framework's effectiveness across a comprehensive benchmark suite like Rodinia [6] remainsanopenquestion.

2. The "Cold Start" Problem: Like many ML applications,ourframeworkrequiresaninitial

dataset for training. This phase, involving 50 full hardwareevaluations,stillrepresentsasignificant upfront computational cost. For very large and complex parameter spaces, this initial sampling coulditselfbecomeabottleneck.

3. Generator Dependency: The framework was tightly integrated with the Vortex [3] generator. Porting it to another generator, such as Nyuzi [4] or a proprietary industrial tool, would require non-trivial effort. The model, having learned the specificbehaviorsandparameternamesofVortex, wouldneedtobecompletelyretrained.

4. Scalability of the Parameter Space: Weexplored afive-dimensionalparameterspace.Aproductionlevel generator could easily expose dozens of parameters. As the dimensionality of the search space grows, the number of samples needed to build an accurate model (the "curse of dimensionality") could challenge the efficiency of thisapproach.

These limitations provide a clear roadmap for future research.Weproposethefollowingkeydirections:

1. Generalization through Transfer and Multitask Learning: To address the workload and generator specificity issues, we plan to explore transfer learning.Afoundationalmodelcouldbe

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:09|Sep2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

pre-trained on a variety of benchmarks and generator architectures. When presented with a new,specifictask(e.g.,optimizinganewGPUfora specific bioinformatics kernel), this model could be rapidly fine-tuned with a much smaller number of new data points, drastically reducing the"coldstart"cost.

2. Advanced Multi-Objective Optimization: Our current approach optimizes for a scalarized objective (Performance-per-Watt). A more powerful technique would be to employ true multi-objective optimization algorithms. Future work will investigate integrating advanced Bayesian methods like Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) or using evolutionary algorithms like NSGA-II guided by the ML surrogate. This would allow the framework to discover the entire Pareto front simultaneously, providing the designer with a richer set of tradeoffoptions.

3. Incorporating Physical Design Awareness: Our current PPA model stops at post-synthesisarea.A major source of designfailure occurslater, during physical place-and-route, where timing closure or routingcongestionbecomesanissue.Asignificant step forward would be to create a physicallyaware surrogate model. This model would be trained not just on synthesis results but also on datafromphysicallayouttools,predictingmetrics like worst negative slack (WNS) and routing congestion. This would guide the DSE process away from designs that are functionally correct butphysicallyunrealizable.

4. Hardware-Software Co-Design Loop: The ultimate vision is a framework that co-optimizes both the hardware and the software. We envision extending ML-Surrogate to not only configure the GPU's hardware parameters but also to tune the application's software parameters (e.g., thread block sizes, memory access patterns) in tandem. Thisholisticapproachwouldunlockanewlevelof performance by ensuring the software and hardwareareperfectlymatched.

The transition to domain-specific architectures presents bothamonumentalopportunityandasignificantchallenge for the field of computer architecture. While hardware

generatorsprovidethemeanstocreatecustomsilicon,the sheer complexity of the available design space has emergedasamajorbottleneck.Thispaperintroduced MLSurrogate, a framework designed to directly address this DSEchallengeforparameterizableGPUs.

Ourcorecontributionisthedemonstrationthatamachine learning-based surrogate model, integrated within a Bayesian Optimization loop, can effectively replace the brute-force nature of traditional exploration with an intelligent, learning-based search. Our findings are conclusive: the ML-Surrogate framework successfully identified Pareto-optimal GPU configurations with a computationalbudgetreductionofupto80%comparedto a random search methodology. Furthermore, the designs discovered by our framework were qualitatively superior, offering better trade-offs between performance, power, andarea.

This work serves as a critical proof-of-concept for the "AI for EDA" paradigm. It shows that the complex, non-linear, and often unintuitive relationships that govern hardware microarchitecturecanbeeffectivelylearnedandnavigated by modern machine learning techniques. By making the process of design space exploration faster, cheaper, and more effective, we can unlock the full potential of generated hardware. The ultimate promise is a future where hardware design is more agile and accessible, enabling the rapid creation of truly novel, applicationspecific processors that will drive the next wave of computationalinnovation.

[1] M. Horowitz, "Computing's energy problem (and what we can do about it)," in IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference Digest of Technical Papers (ISSCC), 2014.

[2] K. Asanović et al., "The Rocket Chip Generator," EECS Department, University of California, Berkeley, Tech. Rep. UCB/EECS-2016-17,2016.

[3]F.F.Fung,A.T.B.Lastra,andZ.P.DeVito,"Vortex:AA Full-System GPGPU and Runtime for Research in Real Systems," in Proceedings of the 2019 ACM/SPEC International Conference on Performance Engineering, 2019.

[4]J.Tan,C.M.Gill,J.A.Jablin,andL.-N.Pouchet,"Nyuzi:A parameterizable GPGPU," in IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Code Generation and Optimization (CGO), 2017.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:09|Sep2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

[5]M.Guz,J.F.Jablin,A.G.M.Smith,B.C.S.F.T.D.R.Kaeli, "MIAOW – An Open Source GPGPU," in Proceedings of the 9th Annual Workshop on General Purpose Processing using GraphicsProcessing Units,2016.

[6]S.Che,M.Boyer,J.Meng,D.Tarjan,J. W.Sheaffer,S.-H. Lee, and K. Skadron, "Rodinia: A benchmark suite for heterogeneous computing," in IEEE International SymposiumonWorkloadCharacterization(IISWC),2009.

[7]A.D.Stratis,M.M.Aater,andD.I.August,"TheParboil Benchmark Suite: A Set of Parallel Applications for Architecture and Compiler Research," in Performance Analysis ofSystemsandSoftware(ISPASS),2012.

[8] A. Mirhoseini et al., "A graph placement methodology for fast chip design," Nature, vol. 594, no. 7862, pp. 207–212,2021.

[9] J. L. Henning, "SPEC CPU2006 benchmark descriptions," ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News, vol.34,no.3,pp.1–17,2006.

[10]P.N.whatmough,S.K.Lee,S.K.saeidi,Z.A.zhou,M.H. ben-yosef, and D. M. Brooks, "A 28nm SoC for a 10-core 1.2V0.98pJ/instAll-DigitalNear-ThresholdProcessorwith a Data-Adaptive Clocking Scheme," in IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference Digest of Technical Papers (ISSCC),2015.

[11] D. R. Jones, M. Schonlau, and W. J. Welch, "Efficient global optimization of expensive black-box functions," Journal of Global Optimization, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 455–492, 1998.

[12] T. Chen and C. Guestrin, "XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System," in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining,2016.

[13] S. Li et al., "McPAT: An Integrated Power, Area, and Timing Modeling Framework for Multicore and Manycore Architectures," in 42nd Annual IEEE/ACM International SymposiumonMicroarchitecture(MICRO),2009.