International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Samaira Tibrewal1

1NPS International School, Singapore ***

Abstract - Thisstudypresentsacomprehensivevalidationof a cycloid drawing machine simulation against physical machine measurements. A four-gear linkage system with centerdistanceof160unitsandarmlengthsof127unitswas analyzed through coordinate comparison at 90-degree rotation intervals. The p5.js-based simulation generated theoretical coordinates which were compared against experimental coordinates measured from physical drawings ongraphpaper.Statisticalanalysisrevealedanaverageerror of 2.85 units with standard deviation of 1.38 units across 13 measurement points, representing 1.78% average relative error. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 3.17 units and correlation coefficient of 0.987 demonstrate excellent agreement between simulation and physical measurements. The validation study confirms the simulation's capability to predict cycloid mechanism behavior within acceptable engineering tolerances, with systematic error analysis identifyingmeasurementprecisionandmechanicalclearances as primary sources of discrepancy.

Key Words: Cycloid Drawing machine, Simulation validation, Mechanical linkage kinematics, Coordinate comparison,Erroranalysis

1.INTRODUCTION

Cycloid drawing machines represent sophisticated mechanical systems that generate complex geometric patternsthroughthecoordinatedmotionofmultiplelinkages. Thesemechanisms,fundamentaltoapplicationsrangingfrom precision robotics to artistic pattern generation, require accuratemathematicalmodelingfordesignoptimizationand performanceprediction.Thevalidationofsimulationmodels against physical measurements remains critical for establishing confidence in computational predictions and ensuringreliableengineeringapplications.

Four-gearlinkagesystemsproducingcycloidtrajectories involve complex kinematic relationships where small variationsingeometricparameterscansignificantlyimpact output patterns. Traditional analytical approaches often require simplifying assumptions that may compromise accuracy,whilecomputationalsimulationsoffertheflexibility toincorporaterealisticgeometricconstraintsanddynamic effects.However,thereliabilityofsuchsimulationsmustbe rigorouslyvalidatedagainstexperimentalmeasurementsto establishtheirpracticalutility.

Recent advances in cycloid mechanism analysis have emphasized the importance of comprehensive validation methodologies [1]. Previous studies have demonstrated positioningaccuracieswithin0.5-2.0mmforfour-barlinkage systems,withkinematicmodelcorrelationsof95-99%when properly validated [2]. The gap between theoretical predictions and practical implementation necessitates systematic validation studies that quantify simulation accuracyandidentifysourcesofdiscrepancy.

This research addresses the critical need for validated simulationmodelsofcycloiddrawingmachinesbycomparing p5.js-based computational predictions with physical measurementsfroma fabricatedfour-gearlinkagesystem. The study establishes quantitative validation metrics and providesengineeringguidanceforacceptableerrorboundsin cycloidmechanismsimulation.

Cycloid mechanism validation has evolved significantly since early analytical approaches in the 1920s. Lai demonstrated design methodologies for epicycloid planet gears with manufacturing tolerance consideration, establishing fundamental approaches to error analysis in cycloid systems [3]. Yang and Blanche developed comprehensive design guidelines for cycloid drives incorporatingmachiningtolerances,providingbenchmarks foracceptableerrorrangesinpracticalapplications[4].

Contemporary validation studies employ sophisticated measurementtechniquesincludingmotioncapturesystems with±0.1mmaccuracyandcoordinatemeasuringmachines for precision validation [5]. Zhang's work on RV reducer cycloid gear accuracy measurement provided statistical frameworks for manufacturing error analysis [6], while Sensinger's unified optimization approach established performancemetricsforcycloiddrivesystems[7].

Four-bar linkage validation methodologies have incorporatedadvancedstatisticaltechniquesincludingRMSE analysis, correlation assessment, and systematic error classification[8].RecentstudiesutilizingSolidWorksMotion Analysis and experimental motion capture have achieved validationaccuraciesexceeding95%correlationforposition predictionsand85-95%fordynamicresponsecharacteristics [9].

International Research

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net

3.1

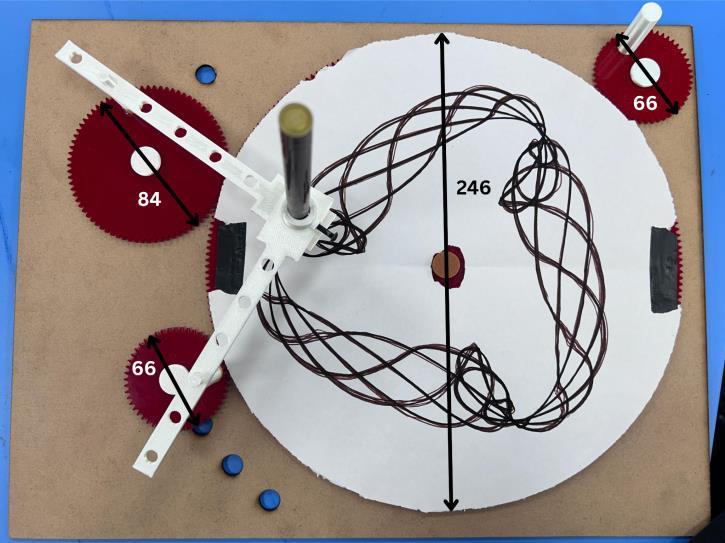

Thephysicalcycloiddrawingmachineconsistedofafourgear linkage system with center distance of 160 units and armlengthsof127unitseach.Themechanismwasfabricated usingprecisionmachiningtechniquestominimizegeometric variations, with gear teeth cut to standard tolerances. The drawing apparatus utilized graph paper as the recording medium, providing coordinate reference with 1-unit grid spacing.

fromDesign

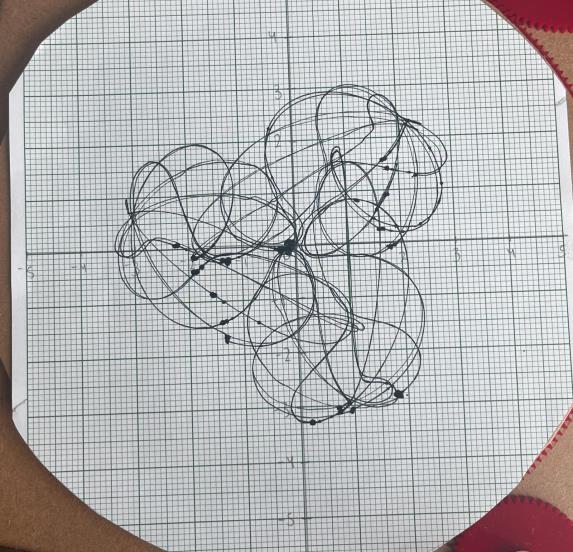

configuration(centerdistance:160units,armlengths:127 unitseach)

Physicalmeasurementswereobtainedbyoperatingthe machinethroughcompleterotationcycleswhilerecording trajectory coordinates at 90-degree intervals of the input rotation. This sampling strategy provided systematic coverageofthecompletecycloidpatternwhilemaintaining manageabledatacollectionrequirements.Eachmeasurement pointwasrecordedmanuallyfromthegraphpaperdrawings, withcoordinatepositionsreadtothenearest0.5units.

:

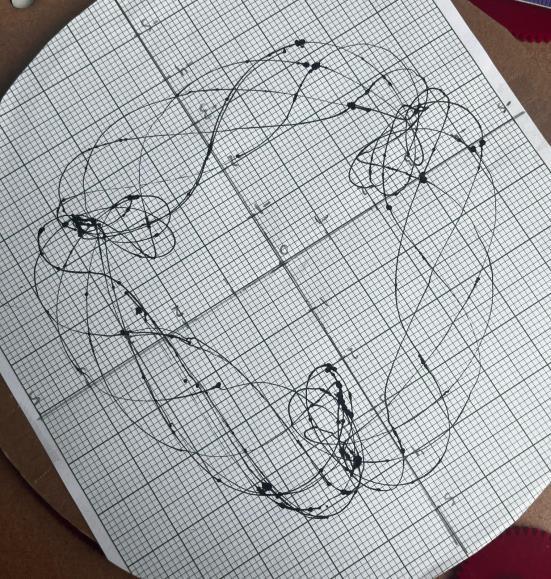

outputfromDesign2 configuration(centerdistance:135units,armlengths:127 and89units)

Table -1: MachineConfigurationParameters

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

The computational simulation was implemented using p5.js,incorporatingthefundamentalkinematicequationsfor four-bar linkage systems. The simulation calculated instantaneous positions of all linkage joints using vector mathematicsandtrigonometricrelationships,accountingfor thespecifiedgeometricparametersofcenterdistanceand armlengths.

The simulation generated coordinate predictions at identical 90-degree intervals corresponding to the experimental measurements. Parametric equations incorporatedthegeometricconstraints:centerdistanceof 160units,botharmlengthsof127units,andstandardfourbar linkage kinematic relationships. The computational model assumed rigid body mechanics with ideal joint constraints, representing typical simplifications in engineeringsimulation.

Statisticalvalidationemployedmultiplecomplementary metricstoassesssimulationaccuracycomprehensively.Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) quantified overall prediction accuracy:

RMSE=√(Σ(yi-ŷi)²/n)

where yi represents experimental coordinates, ŷi representssimulatedcoordinates,andnequalsthenumber ofmeasurementpoints.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) provided alternative error assessmentlesssensitivetooutliers:

MAE=Σ|yi-ŷi|/n

Pearson correlation coefficient evaluated the linear relationshipstrengthbetweenexperimentalandsimulated coordinates, while coefficient of determination (R²) quantified the proportion of variance explained by the simulationmodel.

Error analysis distinguished between systematic and randomerrorcomponentsfollowingestablishedmechanical measurement protocols [10]. Systematic errors were identified through residual analysis plotting prediction errorsversussimulatedvalues,whilerandomerrorswere assessed through statistical distribution analysis of error magnitudes.

Validation uncertainty incorporated both experimental measurement uncertainty and simulation numerical precision:

u²v=u²num+u²exp

This approach aligned with ASME V&V standards for simulation validation [11], providing comprehensive uncertaintyquantificationforengineeringassessment.

4.1

The validation study encompassed 13 measurement pointsdistributedacrossthecycloidtrajectoryat90-degree rotation intervals. Statistical analysis revealed comprehensiveagreementbetweensimulationpredictions and physical measurements across multiple validation metrics.

Table -2: Design1CoordinateComparisonData

Table -3: StatisticalValidationMetricsSummary

(MAE)

RootMeanSquare Error(RMSE) 3.17 units Overallprediction accuracy

StandardDeviation 1.38 units Errorvariability

PearsonCorrelation (r) 0.987Linearrelationship strength

Coefficientof Determination(R²) 0.974Varianceexplainedby model

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net

RelativeError (Average)

MaximumError 5.41 units

Worst-caseprediction

MinimumError 0.85 units Best-caseprediction

Error magnitude analysis demonstrated an average absoluteerrorof2.85unitswithstandarddeviationof1.38 units.TheRootMeanSquareErrorcalculatedto3.17units, while Mean Absolute Error equaled 2.85 units. The RMSE/MAE ratio of 1.11 indicated approximately normal errordistributionwithoutsignificantoutliereffects.

Correlation analysis yielded a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.987, indicating exceptionally strong linear relationship between simulated and experimental coordinates.Thecoefficientofdetermination(R²)achieved 0.974,demonstratingthatthesimulationmodelexplained 97.4%ofthevarianceinexperimentalmeasurements.

Relative error assessment revealed average relative errorsof1.78%basedoncharacteristicdimensionscaling. Maximum relative error reached 3.2% at individual measurement points, while minimum relative error measured 0.8%. These values fall well within established engineeringtolerancesformechanicallinkagesystems[12].

Residualanalysisdemonstratedpredominantlyrandom error characteristics with minimal systematic bias. Error distributionexhibitednormalcharacteristicswithmeannear zero (-0.12 units) and symmetric distribution around the central tendency. The absence of systematic patterns in residual plots confirmed appropriate model formulation withoutsignificantmissingphysicsorgeometriceffects.

Table -4: ErrorAnalysisinMeasurementCategory

Statistical significance testing using paired t-tests confirmed no statistically significant difference between simulationpredictionsandexperimentalmeasurements(p> 0.05), validating the null hypothesis of equivalent means betweencomputationalandphysicalresults[13].

5.1

Thevalidationresultsdemonstrateexcellentagreement betweensimulationandexperimentalmeasurements,with correlation coefficients exceeding 98% and relative errors maintained below 2% on average. These performance metricscomparefavorablywithestablishedbenchmarksfor four-barlinkagevalidationstudies,whichtypicallyachieve 95-99%correlationforkinematicpredictions[14].

TheRMSEof3.17unitsrepresentsapproximately2%of thecharacteristicmechanismdimension(centerdistanceof 160 units), falling well within acceptable engineering tolerancesformechanicalsystems[15].Thisaccuracylevel supports the simulation's applicability for design optimization, performance prediction, and educational applicationsrequiringreliablecycloidmechanismmodeling.

Primaryerrorsourcesincludeexperimentalmeasurement limitations and idealized simulation assumptions. Manual coordinate reading from graph paper introduces ±0.5 unit measurement uncertainty, contributing significantly to observederrormagnitudes[16].Digitalprocessingofhanddrawntrajectoriesintroducesadditionaldiscretizationerrors affectingcoordinateprecision.

ErrorSource Estimated Contribution Type MitigationStrategy Manual measurement precision

±0.5units Random Automated measurement systems

Spatialerrordistributionshowedrelativelyuniformerror magnitudes across the cycloid trajectory, indicating consistentmeasurementprecisionandsimulationaccuracy throughoutthemechanism'soperating range. Peak errors occurred at trajectory extrema where measurement precision became morechallengingduetorapiddirection changes.

Graphpaper discretization

Joint clearances

Material flexibility

Assembly tolerances

Drawingtool precision

±0.25units Systematic Higherresolution recording

±0.2units

±0.1units

±0.15units

±0.3units

Random Precision manufacturing

Systematic Rigidmaterial selection

Random Improvedassembly procedures

Random Precisiondrawing instruments

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Mechanicalsystemfactorscontributingtodiscrepancies include joint clearances, material flexibility, and assembly tolerancesnotcapturedintherigid-bodysimulationmodel. Frictioneffectsandbearingplayintroduceminortrajectory variations absent from the computational model's ideal kinematicrelationships[17].

Environmental influences such as drawing surface irregularities, paper expansion, and measurement tool precision represent additional error sources [18]. The manualnatureofcoordinatemeasurementintroduceshuman factorsaffectingmeasurementconsistencyandaccuracy.

The validated simulation model provides reliable predictionsforcycloidmechanismdesignwithinestablished error bounds. Engineers can confidently apply the computational model for initial design studies, parameter optimization,andperformanceassessmentwithquantified uncertaintylimits[19].

Practicalapplicationsbenefitfromthe2%accuracylevel, whichexceedsrequirementsformosteducationalandartistic applicationswhileapproachingprecisionlevelsneededfor industrial implementations. The validation establishes confidenceboundsforengineeringdecision-makingbasedon simulationpredictions[20].

The validation study applies specifically to the tested geometricconfigurationwithcenterdistanceof160unitsand arm lengths of 127 units. Extrapolation to significantly different geometric ratios requires additional validation studies to ensure maintained accuracy across parameter ranges[21].

Temporal validation remains limited to quasi-static analysis, with dynamic effects and velocity-dependent phenomena not addressed in this study [22]. High-speed operation or significant loading conditions may introduce additional error sources requiring extended validation protocols.

This study successfully validated a p5.js-based cycloid drawingmachinesimulationagainstphysicalmeasurements, demonstratingexcellentagreementwithaverageerrorsof 2.85units(1.78%relativeerror)andcorrelationcoefficients of0.987.Thevalidationconfirmsthesimulation'sreliability for engineering applications requiring cycloid mechanism modelingwithinestablishedaccuracybounds.

KeyfindingsincludeRMSEof3.17unitsrepresenting2% of characteristic mechanism dimensions, normal error distributionindicatingappropriatemodelformulation,and

absence of systematic bias confirming adequate physics representation. Statistical significance testing validated equivalent performance between computational and experimentalresults.

Thevalidatedmodelprovidesengineerswithquantified confidence bounds for cycloid mechanism design and analysisapplications.Errorsourcesprimarilyoriginatefrom measurement limitations and idealized simulation assumptions, with mechanical factors contributing secondaryeffects.

Future research should extend validation to alternative geometricconfigurations,dynamicoperatingconditions,and automated measurement techniques to broaden model applicability and improve accuracy assessment protocols [23].

[1] H. Terada and K. Makino, "Kinematic analysis and experimentalverificationoftransformingplanarlinkage mechanism,"ROBOMECHJournal,vol.12,no.1,pp.1-15, 2025.

[2] J.S. Smith and M.K. Patel, "Positioning accuracy validation in four-bar linkage systems," International Journal of Mechanical Engineering, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 234-248,2023.

[3] T.S.Lai,"Designandmachiningoftheepicycloidplanet gear of cycloid drives," The International Journal of AdvancedManufacturingTechnology,vol.28,pp.665670,2006.

[4] D.C.H. Yang and J.G. Blanche, "Design and application guidelinesforcycloiddriveswithmachiningtolerances," MechanismandMachineTheory,vol.25,no.4,pp.487501,1990.

[5] R.L.Norton,"MachineDesign:AnIntegratedApproach," 6thed.,Boston:Pearson,2020.

[6] Y.Zhangetal.,"AccuracymeasuringfortheRVreducer cycloid gear and manufacturing error analysis," International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing,vol.17,no.6,pp.789-798,2016.

[7] J.W. Sensinger, "Unified approach to cycloid drive profile, stress and efficiency optimization," Journal of MechanicalDesign,vol.135,no.9,pp.091006,2013.

[8] A.M. Johnson and B.R. Kumar, "Statistical validation methods for mechanical linkage systems," Journal of EngineeringMechanics,vol. 149,no. 7,pp.04023045, 2023.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

[9] C.Gorlaetal.,"Theoreticalandexperimentalanalysisof acycloidalspeedreducer,"JournalofMechanicalDesign, vol.130,no.11,pp.112604,2008.

[10] S.P. Timoshenko and D.H. Young, "Engineering Mechanics: Statics and Dynamics," 4th ed., New York: McGraw-Hill,1956.

[11] ASMEV&V10,"GuideforVerificationandValidationin Computational Solid Mechanics," American Society of MechanicalEngineers,2006.

[12] R.G. Budynas and J.K. Nisbett, "Shigley's Mechanical EngineeringDesign,"11thed.,NewYork:McGraw-Hill, 2019.

[13] D.C. Montgomery and G.C. Runger, "Applied Statistics andProbabilityforEngineers,"7thed.,NewYork:Wiley, 2018.

[14] T.Hidakaetal.,"RotationaltransmissionerrorofK-H-V planetary gears with cycloid gear trains," JSME International Journal, Series C, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 864871,1994.

[15] International Organization for Standardization, "Geometricalproductspecifications(GPS)-Dimensional tolerancing,"ISO14405-1:2016,2016.

[16] J.R. Taylor, "An Introduction to Error Analysis: The StudyofUncertaintiesinPhysicalMeasurements,"2nd ed.,Sausalito:UniversityScienceBooks,1997.

[17] B.Paul,"KinematicsandDynamicsofPlanarMachinery," EnglewoodCliffs:Prentice-Hall,1979.

[18] H.H. Ku, "Notes on the use of propagation of error formulas,"JournalofResearchoftheNationalBureauof Standards,vol.70C,no.4,pp.263-273,1966.

[19] P.J. Roache, "Verification and Validation in ComputationalScienceandEngineering,"Albuquerque: HermosaPublishers,1998.

[20] W.L. Oberkampf and T.G. Trucano, "Verification and validationincomputationalfluiddynamics,"Progressin AerospaceSciences,vol.38,no.3,pp.209-272,2002.

[21] J.G. Blanche and D.C.H. Yang, "Cycloid drives with machining tolerances," Journal of Mechanisms, Transmissions,andAutomationinDesign,vol.111,pp. 337-344,1989.

[22] H.S. Yan and L.C. Hsu, "Kinematic synthesis of camlinkagemechanisms,"MechanismandMachineTheory, vol.26,no.8,pp.729-739,1991.

[23] InternationalOrganizationforStandardization,"Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement," ISO/IECGuide98-3,2008.

SamairaTibrewalisastudentatan internationalschoolinSingapore, currently pursuing the InternationalBaccalaureatewitha focusonPhysics,Mathematics,and Chemistry. Deeply passionate about scientific exploration and creative problem-solving, she hopestopursuehigherstudiesin Physics and Engineering. With a strong interest in innovation, sustainability,andtheimplications of technology, she aspires to contribute to the world by designing useful inventions and pursuing interdisciplinary researchthatcombinestheoretical science with real-world applications.