International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Mr. Akshay R. Khadse 1 , Mr. Akash V. Katode2

1Assistant Professor, Dr. Rajendra Gode Institute of Technology and Research, Amravati, Maharashtra, India 2Deputy Manager, Myra Academy Hyderabad, Telangana, India

Abstract - Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs) and Plug-in HybridElectricVehicles(PHEVs)haveemergedastransitional technologiesbridgingthegapbetweenconventionalInternal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles and fully Electric Vehicles (EVs). By combining electric propulsion with combustion engines,theyofferenhancedefficiency,reducedemissions,and extended driving ranges. Among HEVs and PHEVs, the two dominant architectures series and parallel hybrids feature distinct structural designs and operational strategies that significantly influence performance outcomes. This study provides a comparative analysis of series and parallel architectures,focusingonenergyconversionefficiency,power distribution, fuel economy, and adaptability to different driving conditions. The structural characteristics of each configuration are examined to underline their strengths, weaknesses, and suitability in real-world applications. Furthermore, the work extends the analysis by comparing HEVs and PHEVs with traditional EVs, evaluating key parameters such as acceleration, driving range, energy consumption,andenvironmentalimpact.WhileEVsexcelwith zerotailpipeemissionsandsimplifiedpowertrains,HEVsand PHEVs mitigate range anxiety through dual power sources and, in the case of PHEVs, provide the advantage of external charging to extend electric-only operation. The comparative evaluation highlights trade-offs among efficiency, system complexity,cost,andsustainability.Byintegratingstructural and performance perspectives, this article offers a comprehensiveunderstandingofhybridarchitecturesrelative to traditional EVs. The findings aim to inform researchers, engineers, and policymakers on future directions in sustainable vehicle development, supporting the evolution toward cleaner and more efficient transportation systems.

Key Words: ElectricVehicle,HybridE-Vehicle,SeriesPHEVs, ParallelEHEVs,PHEVs,PluginHybridElectricVehicles

The transportation sector is undergoing a profound transformation driven by the urgent need to reduce greenhousegasemissions, minimizedependenceonfossil fuels, and develop sustainable mobility solutions. Electric Vehicles (EVs) have gained global attention as a cleaner alternative to conventional Internal Combustion Engine

(ICE) vehicles. Several categories of EV technologies currentlyexist,includingBatteryElectricVehicles(BEVs), Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs), Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs), and Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs). Each category offers unique advantages in terms of efficiency, sustainability, and emissions reduction, yet challengesremainthataffecttheirpracticalityandadoption onaglobalscale.Despitetheirpromise,battery-basedEVs still face critical limitations that restrict widespread use. Among the most pressing issues are long charging times, limited driving ranges, high battery costs, and inadequate charging infrastructure in many regions. Users often experiencesuddenandunanticipatedbatterydrainduring journeys, creating concerns about being stranded without chargingoptions commonlyreferredtoasrangeanxiety. Furthermore, frequent fast-charging cycles accelerate battery degradation, reducing efficiency and long-term reliability. These factors collectively pose barriers to consumerconfidenceandslowtheglobaltransitiontofull electricmobility.

Nevertheless,thedemandforelectricand hybridmobility continues to grow worldwide, fueled by stricter emission norms, government incentives, and increasing environmentalawareness.CountriesacrossEurope,North America,andAsiahaveannouncedambitiouselectrification targets,whileleadingautomotivemanufacturersareheavily investinginhybridandelectrictechnologies.Inthiscontext, HybridElectricVehicles(HEVs)andPlug-inHybridElectric Vehicles(PHEVs)haveemergedaspracticalsolutionsthat combine the benefits of electric propulsion with the reliability of conventional fuel-based systems. Unlike conventionalHEVs,PHEVsallowexternalcharging,enabling longer electric-only driving ranges while still retaining an internal combustion engine for extended trips. This dualsourcepowertrainnotonlymitigatesrangeanxietybutalso enhances fuel economy, reduces emissions, and provides greater adaptability across varying driving conditions. Hence, PHEVsserveasa critical bridge technology during theglobaltransitiontowardfullyelectrifiedmobility.

Central to PHEVs are the architectural strategies used in their design, primarily the series and parallel hybrid architectures. In a series PHEV, the internal combustion

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

engine does not directly drive the wheels; instead, it operatesasageneratortochargethebatteryorpowerthe electricmotor,makingtheelectricmotorthesolepropulsion unit. This configuration simplifies mechanical design and ensuressmootherelectricdriving,thoughitmaysufferfrom lowerefficiencyduringhigh-speedoperations.Incontrast,a parallelPHEVenablesboththeinternalcombustionengine and electric motor to provide propulsion, either independently or in combination. This improves power delivery and efficiency, particularly on highways, but requiresmorecomplexmechanicalintegration.

Given these differences, the choice of architecture plays a crucial role in determining the overall performance, efficiency,andadaptabilityofPHEVs.Adetailedcomparison ofseriesandparallelarchitecturesisthereforeessentialfor understanding their respective strengths and limitations. This article presents a comprehensive structural and performanceanalysisofseriesandparallel plug-inhybrid electricvehiclearchitectures,withcomparativeinsightsinto conventional EVs. By focusing on power flow, energy consumption, range, and adaptability, the study aims to highlight the trade-offs involved in each architecture and provide guidance for researchers, engineers, and policymakersinadvancingsustainablevehicletechnologies.

The primary objective of this research is to conduct a comprehensivestructuralandperformanceanalysisofseries and parallel plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) architectures, with a comparative evaluation against conventionalbatteryelectricvehicles(EVs).Thestudyaims to systematically investigate how architectural choices influence the efficiency, adaptability, and overall effectivenessofhybridmobilitysolutions.

The specific objectives are as follows:

1. To examine the structural configurations of series and parallel PHEV architectures, highlighting their energy flow mechanisms, powertrain integration strategies,anddesigncomplexities.

2. To evaluate the performance parameters of both architectures, including fuel economy, energy consumption, acceleration characteristics, and drivingrange,undervaryingoperationalconditions.

3. To analyze the comparative advantages and limitationsofseriesandparallelsystemsintermsof efficiency, cost, scalability, and environmental impact.

4. To assess the role of PHEVs as transitional technologies,bridgingthegapbetweenconventional hybrid systems and fully electric vehicles, while mitigatingissuessuchasrangeanxietyandcharging limitations.

5. To provide a comparative perspective with traditional EVs, thereby identifying the trade-offs between architectural complexity, battery dependence,charginginfrastructure,andlong-term sustainability.

6. To derive insights that can guide researchers, engineers, and policymakers in selecting and optimizing hybrid powertrain strategies for nextgenerationsustainabletransportationsystems.

Throughtheseobjectives,theresearchseekstoadvancethe understanding of dual-source powertrain strategies and highlighttheirpotentialinaddressingtheglobalchallenges of energy efficiency, emission reduction, and mobility sustainability.

Inthisresearcharticle,wepresentacomparativestructural and performance analysis of series and parallel plug-in hybridelectricvehicle(PHEV)architectures,withextended insightsintotheirevaluationagainstconventionalelectric vehicles (EVs). The study systematically investigates the design configurations, energy flow mechanisms, and powertrainstrategiesofbothseriesandparallelhybridsto highlight their operational differences, advantages, and limitations.Performanceparameterssuchasfueleconomy, energyefficiency,range,acceleration,andadaptabilityunder varyingdrivingconditionsarecriticallyanalysedtoassess the effectiveness of each architecture. Furthermore, the article emphasizes the role of PHEVs as transitional technologies,bridgingthegapbetweentraditionalhybrids and fully battery-powered EVs by addressing critical challengessuchasrangeanxiety,charginglimitations,and batterydependence.Byintegratingbothstructuralinsights andperformanceoutcomes,theresearchaimstoprovidea holistic representationofhowarchitectural choicesshape hybridvehicleperformance,whilesimultaneouslyofferinga comparativeperspectivewithEVstoguidethedevelopment ofnext-generationsustainablemobilitysolutions.

The methodology adopted for this study is based on a comprehensive literature review and secondary data analysis, focusing on the comparative structural and performance characteristics of series and parallel plug-in hybridelectricvehicles(PHEVs)andtheirevaluationagainst conventional electric vehicles (EVs). The research design followsasystematicreviewapproachtoensuretheinclusion ofdiverseandcrediblesourcesspanningbothacademicand industrial domains. Relevant data were collected from a wide range of peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings,technicalreports,industrywhitepapers,and government publications. Major scientific databases, includingIEEEXplore,ScienceDirect,SpringerLink,Taylor& Francis,WileyOnlineLibrary,andElsevier,wereutilizedto obtain scholarly articles and review papers addressing

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

hybrid vehicle architectures and performance outcomes. Additionally,ScopusandWebofScienceindexingservices were employed to identify high-impact and recent publications. To strengthen industrial and practical perspectives, data were also gathered from Society of AutomotiveEngineers(SAE)technicalpapers,International Energy Agency (IEA) reports, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)publications,andmanufacturerreportsfromleading automotivecompanies.Theliteratureselectionprocesswas carriedoutusingtargetedkeywordssuchas“SeriesHybrid ElectricVehicle,”“ParallelHybridElectricVehicle,”“Plug-in Hybrid Vehicle Architecture,” “Hybrid Powertrain Performance,” and “Comparison with Electric Vehicles.” Articlespublishedbetween2010and2025wereprimarily considered to capture both historical developments and emergingtrendsinhybridvehicledesign.

Dataextractedfromthesesourceswerecarefullyanalysed and synthesized to compare structural design principles, energy flow mechanisms, fuel economy, energy consumption, range capabilities, cost implications, and environmental impacts across series, parallel, and plug-in hybridarchitectures.ComparativereferenceswithEVswere drawn from both empirical performance evaluations and simulation-basedstudies.Bytriangulatinginformationfrom academicresearch,technicalstandards,governmentreports, and industrial case studies, this study ensures that the findingsarecomprehensive,reliable,andreflectiveofboth theoretical advancements and real-world applications in hybridelectricvehicletechnologies.

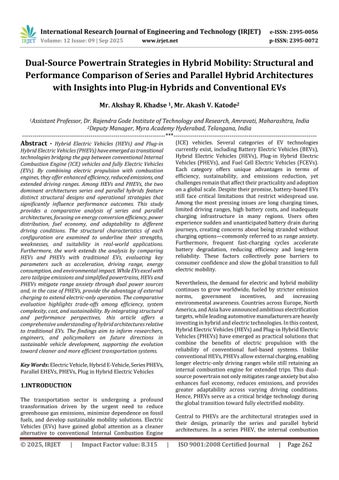

Plug-inHybridElectricVehicles(PHEVs)constituteaclassof electrified road vehicles that integrate an internal combustionengine(ICE)withoneormoreelectrictraction motors and a substantially larger rechargeable traction batterythanconventionalHEVs.DistinctfrompureBattery Electric Vehicles (BEVs), PHEVs are designed to accept externalelectricalenergyviagridchargingandthusenablea significantproportionofeverydaytraveltobeaccomplished in an electric-only mode while retaining the ICE as a complementaryenergysourceforextended-rangeoperation. This dual-source paradigm positions PHEVs as pragmatic transitional technologies that reconcile the operational advantagesofelectrificationreducedoperationalemissions, instantaneous torque, and high urban efficiency with the ubiquityandfastrefuellingcapabilityofliquidfuels.Assuch, PHEVs are conceptually and practically important in contextswherecharginginfrastructure,rangedemands,or user behaviours render full battery electrification problematicinthenearterm.

PHEV powertrains are principally realized through three architecturalparadigmsseries,parallel,andseries-parallel (power-split) each embodying different mechanical

couplings,energyflowtopologies,andcontrolexigencies.In theseriesconfigurationtheICEismechanicallydecoupled fromwheelpropulsionandservesprimarilyasanon-board generatortochargethebatteryordirectlyfeedthetraction motor; this simplification of mechanical elements reduces driveline complexity but introduces additional energyconversionstagesthatmaybesuboptimalatsustainedhigh speeds.Parallel architecturespermit both the ICEandthe electric motor to apply torque to the driveline, enabling moredirect,mechanicallyefficienthigh-speedpropulsionat theexpenseofgreatermechanicalcouplingcomplexityand more sophisticated torque coordination controls. Seriesparallel or power-split architectures deploy planetary gearsetsorpower-split devicestocontinuouslyapportion power between the engine and electric machine(s) and thereby seek to synthesize the efficiency benefits of both pure series and parallel arrangements while incurring greater system complexity and control burden. Core hardware across these variants includes traction motors, invertersandpowerelectronics,tractionbatterypackswith onboardchargingmodules,DC/DCconverters,theICEand transmission elements, and an overarching energy management system (EMS) to orchestrate real-time operation.

Operationally,PHEVsarecharacterizedbymultiplediscrete and blended modes electric-only or charge-depleting operation,hybridorcharge-sustainingoperationinwhich the engine assists or dominates propulsion, regenerative braking for energy recovery, and in some configurations, engine-only cruising modes optimized for highway efficiency. The concept of the utility factor, defined as the proportionofvehiclekilometresundertakeninelectric-only mode,emergesasapivotalmetricthatmodulatesaPHEV’s real-worldenvironmentalandfuel-consumptionadvantages. The same nominal electric range can yield markedly differentlife-cyclebenefitsdependingonchargingfrequency andusertripprofiles.Empiricalevidenceandfieldstudies indicate that standardized laboratory cycles often overestimatereal-worldelectric-shareperformancebecause userchargingbehaviour,ambientconditions,andduty-cycle variability frequently depress the utility factor. Consequently, rigorous assessment of PHEV efficacy must accountforobservedchargingpatternsandrealistictravel distributions rather than relying solely on manufacturerdeclaredelectricrangesoridealizeddrivecycles.

TheEnergyManagementSystemconstitutesthealgorithmic core of a PHEV, determining in real time how to allocate power between the battery, electric motor(s), and ICE to meet driver torque demands while optimizing objectives suchasfuelconsumption,batterystate-of-health,emissions, and occupant comfort. Control strategies range from heuristic rule-based implementations to advanced modelpredictive control, dynamic programming for offline benchmarking of optimality, and emerging data-driven or

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

reinforcement-learning approaches that exploit vehicle connectivityandroutepredictions.Predictiveandadaptive EMS frameworks that incorporate route topology, traffic forecasts, and grid or charging-station availability have demonstratedsignificantpotentialtoincreaseelectric-mile shares and reduce fuel consumption, albeit at the cost of higher computational and sensing requirements. The selectionandtuningoftheEMSdirectlyinfluencenotonly instantaneous performance metrics but also long-term batterydegradationtrajectoriesanduser-perceivedutility, underscoringitscentralroleindefiningtheeffectivenessof PHEVoperation.

Fromaperformancestandpoint,PHEVscombineattributes ofbothelectricandinternal-combustionpropulsion:electric driveaffordshighlow-speedtorqueandsmooth,responsive accelerationinurbancontexts,whiletheICEsupplements continuoushigh-powerdemandsandlong-distancecruising efficiency. Electric-only range commonly engineered from approximately a few tens of kilometres to several dozen kilometres depending on market positioning critically determinesthefractionoftripsthatarepurelyelectricand thus the marginal environmental benefit. Overall system tank-to-wheelefficiencyandfueleconomyforPHEVsexhibit bifurcated behaviour: in charge-depleting operation the vehicle can approximate BEV-like efficiencies, whereas in charge-sustainingormixedusageregimesfueleconomyis strongly contingent on EMS, charging frequency, and user habits. Therefore, comparative assessments of PHEV performancemustdisaggregatemetricsbyoperatingmode and examine composite performance over representative duty cycles to ensure that evaluations are not artificially biasedtowardanysinglemodeofoperation.TypicalPHEV recharging behaviour centres on overnight Level-2 AC charging and opportunistic workplace or public charging; owing to their smaller battery capacities relative to BEVs, PHEVsgenerallyexperiencefewerdeep-cycleandextreme fast-charge events, which can be beneficial for longevity. Nevertheless, battery state-of-charge windows, ambient temperatureexposure,depth-of-dischargepatterns,andthe occasional use of high-power DC fast chargers exert measurable influences on calendar and cycle degradation. Best-practicebatterymanagement suchaslimitingcharge windows (for example 20–80%), avoiding repeated deep discharges, and managing thermal conditioning during charging can materially extend usable battery life and preserveelectric-rangereliability.Importantly,suddeninjourneybatterydepletionremainsapracticalriskforusers who do not adhere to regular charging habits or who encounter atypical auxiliary loads or ambient thermal extremes,underscoringthecontinuedoperationalvalueof theICEasafail-saferangeextenderinPHEVsystems.

Life-cycleanalysesthatintegratemanufacturing,use-phase, andend-of-lifeprocessesrevealthatPHEVstypicallyoccupy an intermediate position between ICE vehicles and BEVs

withrespecttogreenhouse-gasemissions,withtheprecise orderingdependingsensitivelyongridcarbonintensity,the frequency of electric-mode operation, and manufacturing impacts arising chiefly from battery production. On lowcarbon electricity systems and under high utility-factor regimes,PHEVscanrealizesubstantialoperationalemission reductionscomparedwithICEcounterparts.Conversely,in regions where grid electricity is fossil-intensive or where drivers rarely charge, PHEV benefits diminish and may converge toward those of conventional hybrids. Thus, accurate appraisal of PHEV environmental performance mandatesscenario-basedlife-cycleassessmentthatcouples realisticusagedistributionswithregion-specificgridmixes andmanufacturingfootprintassumptions,therebymoving beyondsimplifiedlaboratoryprojectionstomorerigorous sustainabilityappraisals.

Adoption patterns for PHEVs exhibit marked regional heterogeneity that reflects policy frameworks, consumer incentives, and charging infrastructure maturity. In jurisdictionswherepurchasesubsidies,taxadvantages,or regulatory mandates incentivize plug-in adoption while chargingnetworksremainnascent,PHEVsoftenserveasa favoured compromise, delivering partial electrification benefitswithoutimposingextensivecharginginfrastructure dependency on users. Conversely, in markets with rapid expansionoffastandovernightcharginginfrastructureand strong incentives for BEVs, pure battery electrics are increasingly displacing PHEVs as the preferred electrification pathway. Policy instruments that more accurately reflect real-world electric usage such as incentives keyed to demonstrated electric-mile shares wouldbetteralignconsumerincentiveswithenvironmental objectivesandreducediscrepanciesbetweenexpectedand realized benefits, thereby ensuring that PHEVs deliver tangiblesustainabilityoutcomesratherthanonlynominal compliancewithregulatorytargets.Notwithstandingtheir practical advantages, PHEVs pose research challenges spanningrobustEMSdesignunderreal-worlduncertainty, optimized battery thermal and lifecycle management tailoredtomixed-modedutycycles,andthequantificationof real-worldutilityfactorsacrossdiversepopulations.Future work should prioritize predictive and connected energy management strategies that integrate routing, traffic, and gridsignalstomaximizeelectricmileagewhilesafeguarding battery health. Additionally, standardized field evaluation protocolsandricherempiricaldatasetsareessentialtoclose thegapbetweenlaboratory-basedperformanceclaimsand operational realities. Finally, policy and incentive designs must evolve to reflect nuanced lifecycle outcomes by rewarding configurations and usage patterns that demonstrablydeliververifiableemissionreductionsandby supporting infrastructures that encourage consistent grid charging,ensuringthatPHEVsfulfilltheirroleasaneffective transitional technology within the broader electrification landscape.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Figure1.IllustratesthebasicstructureofaPlug-inHybrid ElectricVehicle(PHEV).Thediagramdepictstheintegration ofbothelectricandcombustionpowersourceswithinacar body. Keycomponentsincludethebattery, electricmotor, gasoline engine, gasoline tank, and charging port, all interconnected to enable dual-source propulsion. The batterysuppliespowertotheelectricmotor,whichdirectly drivesthewheels,whilethegasolineengine,supportedby the fuel tank, provides additional mechanical power or assists in charging the battery. The charging port allows external electricity to recharge the battery, extending electric-only operation. Arrows indicate the energy flow paths between these components, highlighting the hybrid powerdistributionstrategy.Thisschematicrepresentation provides an overview of how PHEVs combine efficiency, extendedrange,andreducedemissionsbymergingelectric and combustion technologies within a single vehicle architecture.

3.1. Energy Management and Control Strategies in Plugin Hybrid Electric Vehicles

Overview of EMS in PHEVs

The Energy Management System (EMS) represents the supervisory control unit responsible for optimally distributingpowerbetweentheinternalcombustionengine (ICE),theelectricmotor(s),andthehigh-voltagebattery.The central objective is to satisfy instantaneous driver torque andspeeddemandswhilesimultaneouslyoptimizinglongterm objectives such as fuel economy, battery health, and emission reduction. Unlike conventional HEVs, PHEVs introduceanadditionallayerofcomplexitysincethesystem mustalsoaccountforgrid-chargingopportunities,battery

state-of-charge (SOC) planning, and electric-only driving ranges.

Classification of EMS Approaches

EMSstrategiesforPHEVscanbebroadlyclassifiedintorulebasedmethodsandoptimization-basedmethods:

1. Rule-Based Control (RBC):

Deterministic Rules: Predefined thresholds (e.g., SOC>40%⇒electricmode,SOC<30%⇒engine mode).

FuzzyLogic/HeuristicRules:Softthresholdsand decisionmatricestoadapttovaryingconditions.

Advantage:Simple,lowcomputationaldemand.

Limitation: Sub-optimal in dynamic or unpredictabledrivingenvironments.

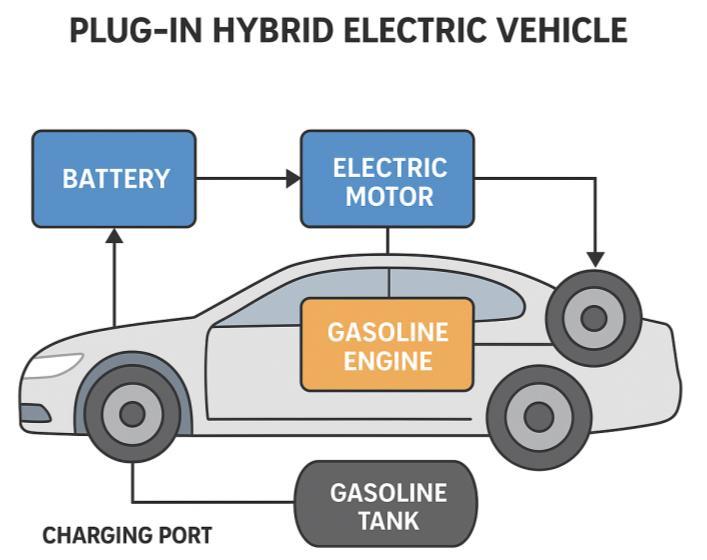

Dynamic Programming (DP): Solves global optimizationovera givendrivecycle tominimize fuelconsumptionandemissions.

where,��˙��������(��)m˙fuel(t)isfuelconsumption,��������(��)Pbat (t)isbatterypowerusage,and����������(��)representsemission cost.

Model Predictive Control (MPC): Uses predictive models to optimize control inputs over a moving horizon.

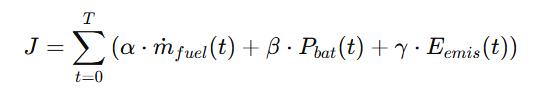

Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (ECMS): Converts electric energy use into an equivalentfuelconsumption: where“��”λistheequivalencefactor,��������isbattery efficiency,and“������”isfuellowerheatingvalue.

TheUtilityFactor(UF)quantifiestheproportionofdistance drivenelectricallyandiscriticalinreal-worldassessmentof PHEVs: where:

������=distance driven in electric-only mode (chargedepletingmode),

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 © 2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 |

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

������������=totaldistancedriven.

AhigherUFimpliesgreaterutilizationofgridenergy,leading to reduced gasoline consumption and improved environmentalbenefits.However,UFishighlysensitiveto driver charging habits and daily travel distances. For example,aPHEVwith50kmelectricrangeachieveshighUF forshortcommutes(<40km)butlowUFforlongcommutes (>100km)ifintermediatechargingisunavailable.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Integration

EMSdecisionsdirectlyinfluencetheLifeCycleAssessment (LCA) outcomes of PHEVs, as energy consumption modes alterbothoperationalemissionsandbatteryaging.ThelifecycleCO₂emissionscanbeexpressedas:

electricitygenerationmix.Maintenancerequirementsalso differ significantly, with BEVs benefiting from simplified drivetrainsandfewermovingparts,whilePHEVsnecessitate more frequent and intricate servicing due to the dual powertraincomponents.

Parameter

Propulsion System

Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV)

Solelyelectricmotor withhigh-efficiency powerelectronics

Energy Source

where:

Emanu=emissionsfrommanufacturing(including batteryproduction),

EGrid(t)=gridemissionfactorattime��,

DEV(t),��������(��)=electricandICE-drivendistances,

ηEV,ηICE= efficiency factors for electric and combustionpropulsion,

EEOL=end-of-lifeprocessingemissions.

IntegratingEMSoptimizationwithLCAallowsresearchersto evaluate true sustainability of PHEVs under diverse grid carbonintensitiesanddrivingpatterns.

Table1illustratesacomprehensivecomparativeanalysisof BatteryElectricVehicles(BEVs)andPlug-inHybridElectric Vehicles(PHEVs),emphasizingthefundamentaldifferences intheirdesign,operation,andperformancecharacteristics. BEVsarefullyelectric,relyingexclusivelyonhigh-efficiency electricmotorspoweredbyrechargeablebatterysystems, whichenablessuperiorwell-to-wheelefficiencyandnearzero tailpipe emissions. Their driving range is primarily constrained by battery capacity and state-of-charge limitations,makingthemparticularlysuitedforshort-range urban commuting where frequent charging is feasible. In contrast, PHEVs employ a dual-source propulsion system thatintegratesanelectricmotorwithaninternalcombustion engine(ICE),allowingthevehicletooperateinelectric-only mode for short distances while providing extended range through ICE assistance for longer trips. This hybrid configurationenhancesoperationalflexibilityandmitigates range anxiety, but introduces additional mechanical and control system complexity, as well as variable energy conversionefficiencydependingontheproportionofelectric and ICE usage. Furthermore, PHEVs exhibit moderate lifecycle emissions that depend on the ratio of electric operation to fuel consumption, whereas BEVs’ environmental performance is largely influenced by the

Driving Range

Charging and refueling

Rechargeablelithiumionoradvanced batterychemistries

Limitedbybattery capacity;subjectto state-of-charge(SoC) andtemperature effects

Requiresexternalgrid charging infrastructure; dependenton chargingrateand batterycharacteristics

Energy Conversion Efficiency

Environmental Impact

Maintenance Complexity

Optimal Use Case

Highwell-to-wheel (WTW)efficiencydue todirectelectrical propulsion

Zerotailpipe emissions;lifecycle emissionsdependon electricitymix

Lowerdueto simplifieddrivetrain andminimalmoving parts

Urbanandshortrangetravelwith frequentcharging opportunities

Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV)

Combinationof electricmotorand internalcombustion engine(ICE)enabling dual-modeoperation

Batterysupplemented byconventionalfuel (petrol/diesel)for extendedoperational range

Extendedrangedue toICEintegration; electric-onlymode availableforshort trips

Supportsbothgrid chargingforelectric operationand conventional refuelingforhybrid operation

VariableWTW efficiency;energy lossesoccurduring ICEoperationand motor-ICE coordination

Reducedtailpipe emissions;overall environmentalimpact dependsonelectricto-fuelusageratio

Higherduetodual powertrain componentsand integratedcontrol systems

Mixeddriving scenarioswithurban andhighway operation;mitigates rangeanxiety

Table 1. comprehensive comparative analysis of Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs)

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Overall, the table underscores that the selection between BEVs and PHEVs should be informed by driving patterns, energyefficiencyconsiderations,environmentalimpact,and totalcostofownership,highlightingthetrade-offsbetween sustainability, operational flexibility, and technological complexityinherentineachvehicletype.

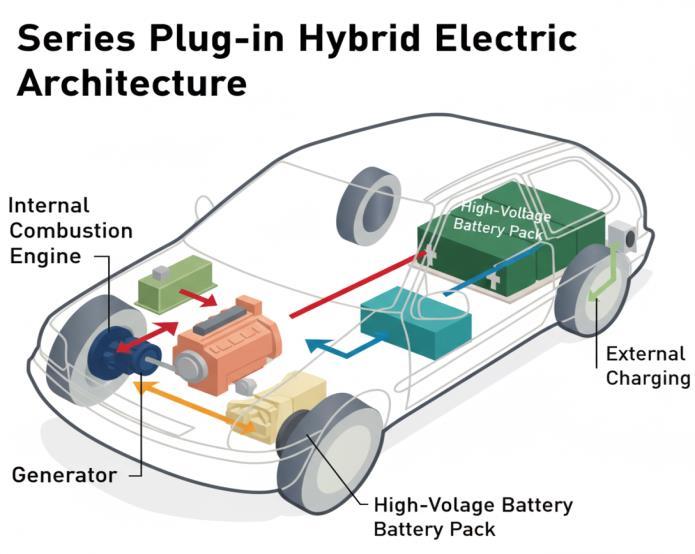

4.1. A plug-in series hybrid electric vehicle (series PHEV or range-extended EV)

A plug-in series hybrid electric vehicle (series PHEV or range-extended EV) integrates an internal combustion engine (ICE) with an electric generator but has no direct mechanicalconnectionbetweentheengineandthewheels. Instead,thegeneratorconvertsthemechanicalpowerofthe ICE into electrical energy, which either charges the highvoltagebatteryorsuppliesthetractionmotorthatdrivesthe wheels. All propulsion is delivered by the electric motor, allowingthevehicletooperateinanall-electricmodeuntil thebatterystate-of-chargefallsbelowacertainthreshold,at whichpointtheICErunsasageneratortosustainthecharge orextendtherange.Theplug-incapabilityenablesexternal chargingfromthegrid,somuchofthedailydrivingdistance can be achieved in electric-only mode with zero tailpipe emissions.Themainstructuralcomponentsincludeahighvoltagebattery,electrictractionmotor,powerelectronics, generator, ICE, fuel tank, and charging port, all interconnectedtosupportdual-sourceoperation.

Figure 2 illustrates the architecture of a plug-in series electric vehicle, also known as a range-extended electric vehicle(REEV).Inthisdesign,aninternalcombustionengine (ICE)ismechanicallylinkedonlytoagenerator,notdirectly tothewheels.Thegeneratorproduceselectricity thatcan either charge the high-voltage battery pack or power the electricmotor,whichisthesolesourceofpropulsionforthe wheels.Thissetupallowsthevehicletooperateonelectric poweraloneforacertainrange,whiletheICEfunctionsasan on-boardpowerplanttoextendthedrivingrangewhenthe battery is depleted. The vehicle can also be externally chargedbypluggingintoanelectricalpowersource.

Figure 2. Architecture of A plug-in series hybrid electric vehicle (series PHEV or range-extended EV)

Intermsofoperation,aseriesPHEVfunctionsinthreemajor modes:charge-depletingmode,inwhichthevehicleoperates entirelyonbatterypower;charge-sustainingmode,where the ICE and generator provide energy to the motor and batteryoncetheSOCthresholdisreached;andregenerative braking,inwhichthemotorrecoversenergytorechargethe battery.Theenergymanagementsystem(EMS)coordinates transitionsbetweenthesemodesanddetermineswhether generatorpowerissentdirectlytothemotororstoredinthe battery. The design of this control strategy has a strong influence on the real-world efficiency and emissions performanceofthevehicle.

The architecture offers several strengths. Because propulsion always comes from the motor, series PHEVs providesmoothtorquedelivery,fastresponse,andstrong accelerationcomparabletobatteryelectricvehicles(BEVs). The ICE can be optimized to run at narrow, efficient operatingpointsbecauseitismechanicallydecoupledfrom the drivetrain, which helps improve fuel economy during generatoroperation.Fordailyuse,especiallywithregular charging,mosttripscanbecompletedinelectric-onlymode, reducing fuel consumption and tailpipe emissions significantly. These advantages have made series architecturesattractiveforapplicationssuchasurbanbuses andpassengercarswithrange-extenderoptions.

However,trade-offsexist.WhentheICEruns,energymust undergomultipleconversions fromchemicalenergyinfuel to mechanical energy in the ICE, then to electricity in the generator, and finally back to mechanical energy in the motordrivingthewheels.Thesesequentiallossesmakethe system less efficient than parallel hybrids in many conditions, particularly during sustained highway driving. Serieshybridsalsorequirelargerandmorepowerfulelectric

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

motors,largerbatteries,andanadditionalgenerator,which increaseweight,cost,andsystemcomplexity.Furthermore, the environmental benefits depend heavily on charging behavior. If drivers seldom recharge, the vehicle spends more time running in range-extender mode, which diminishes fuel savings and increases real-world CO₂ emissionscomparedwithlaboratoryratings.

Inelectricmode,theenergyconsumptionofaseriesPHEVis similar to that of a BEV of comparable mass and aerodynamics, with typical efficiency expressed in watthours per kilometer. In range-extender mode, the overall efficiency is a product of the ICE’s thermal efficiency, the generator’sconversionefficiency,andthemotor’sefficiency, compounded by drivetrain losses. While these cumulative lossesreducetank-to-wheelefficiency,theadvantageisthat the ICE can be kept in a narrow and efficient operating window.Thus,seriesPHEVsachievetheirgreatestbenefits whendesignedwithsufficientlylargebatteriestomaximize electric driving and when used in driving profiles that includefrequentrecharging.

Real-world studies show that the gap between laboratory testresultsandon-roadperformancecanbesubstantial.In standardized tests, PHEVs are often credited with large reductions in CO₂ emissions and fuel use, but in practice thesebenefitsdependonthefractionofkilometersdriven electrically, also known as the utility factor. If the utility factorislowduetoinfrequentcharging,theactualemissions can be far higher than certified values. This has led to increased scrutiny by policymakers and researchers, who emphasizetheneedtoalign PHEVtestingproceduresand userincentiveswithreal-worldbehavior.

Additional issues include battery degradation, which is influenced by charging habits, temperature extremes, thermal management, and the number of deep charge/dischargecycles.Newerdatasuggeststhatalthough battery replacements in PHEVs remain rare, degradation overtimereduceselectric-onlyrangeandmayleadtolossof performanceorincreasedrelianceontheICE.Properbattery management systems, cooling and heating control, and warranty protections are key mitigators. Owners who seldommaintainbatteryhealth,oroperateinhotclimates, oftenseeearlierdropsinrange.Maintenancechallengesalso includetheICEstarting/stoppingfrequently,whichcanlead toincreasedwearinenginecomponents,especiallyunder sub-optimalwarm-uporlubricationconditions.Thecost-ofownershipmustaccountforhigherupfrontcostduetothe dual powertrain, the extra electrical components, and possibly higher maintenance of high-voltage battery pack and power electronics. In lifetime cost analyses, series PHEVssometimesapproach,butdonotalwaysbeat,parallel hybridorBEValternatives,dependingstronglyonbattery cost trends, charging infrastructure availability, fuel cost, andusagepatterns.

SeriesPHEVsthusrepresentacompellingarchitecturefor achieving high levels of electrification without fully abandoning liquid fuels. They are particularly effective in urbancommutingscenarioswheredailychargingisfeasible, and their ability to run exclusively on electricity for most trips offers substantial environmental advantages. Nevertheless, their benefits are highly dependent on user behavior, charging infrastructure, and EMS design. If implemented well, series plug-in hybrids can serve as an importanttransitionaltechnologytowardfullelectrification, thoughtheirlong-termsustainabilitycomparedwithBEVs andparallelhybridsremainsasubjectofongoingresearch anddebate.

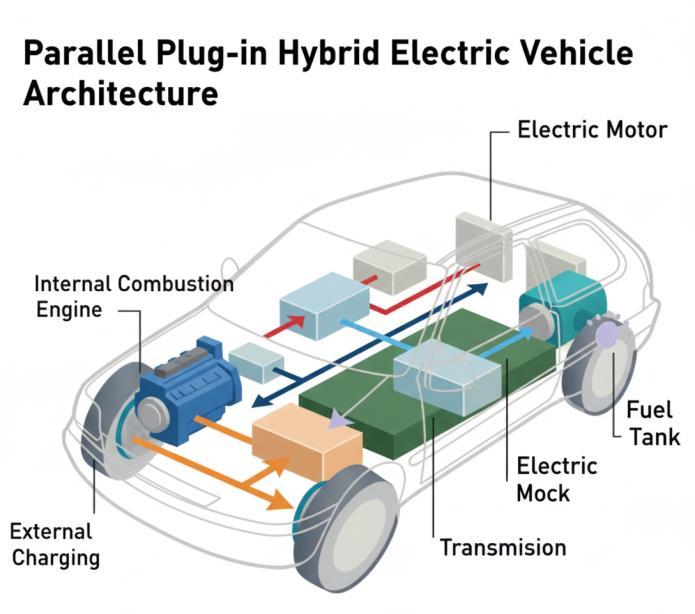

4.2. A plug-in Parallel hybrid electric vehicle (series PHEV or range-extended EV)

A plug-in parallel hybrid electric vehicle (parallel PHEV) architectureintegratesaninternalcombustionengine(ICE) with one or more electric motors, both of which are mechanicallycoupledtothewheelsto providepropulsion either independently or simultaneously. This dual-path arrangement allows the ICE to supply direct mechanical power to the drivetrain while the electric motor supplementsperformanceoroperatesindependentlyunder low-loaddrivingconditions.Thebatterypowersthemotor andisexternallyrechargeablefromthegrid,extendingthe vehicle’s ability to operate in electric-only mode and reducingdependenceonpetroleum.Inaddition,theICEmay recharge the battery through a generator or regenerative braking,creatingaflexiblesystemthatcombinesfuel-based and electric propulsion. Such a structure balances the strengthsofbothsystemsbymaintaininghighefficiencyand offeringlongerrangecomparedtopurelyelectricvehicles, whilereducingtailpipeemissionscomparedtoconventional ICEvehicles.

In practice, parallel PHEVs rely on an advanced energy management system (EMS) that governs the interaction betweenICEandelectricmotor.Thissystemoptimizesthe divisionoflaborbetweenthetwopowersourcesbasedon powerdemand,batterystate-of-charge(SOC),anddriving conditions. At low speeds or during stop-and-go urban traffic, the electric motor typically handles propulsion, maximizing efficiency and reducing local emissions. Conversely, during highway cruising or high-load acceleration, the ICE either takes over or operates in conjunction with the motor to provide sufficient torque. Parallel-split powertrains, also known as power-split or dual-mode configurations, introduce further flexibility by enablingcontinuouslyvariableblendingofpowerbetween the two sources. The sophistication of EMS algorithms, rangingfromrule-basedcontroltopredictiveandmachinelearning-basedoptimization,iscentraltoachievingoptimal fueleconomy,seamlessdrivability,andemissionsreduction.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

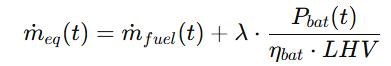

Figure 3 illustrates the architecture of a plug-in parallel electricvehicle,whereboththeinternalcombustionengine (ICE)andtheelectricmotorcandirectlydrivethewheels, either independently or together. This configuration typically uses a high-voltage battery pack that can be chargedexternallyandsuppliespowertotheelectricmotor. Thepowerelectronicsmanagetheflowofenergybetween thebattery,electricmotor,andgenerator(oftenintegrated withthemotor),allowingforflexibleoperationmodessuch as pure electric driving, engine-only driving, or a combinationformaximumperformanceorefficiency.

OneofthemajorstrengthsoftheparallelPHEVarchitecture isitsabilitytoavoidmultipleenergyconversionlossesthat characterizeseriesPHEVs.SincetheICEdirectlytransmits mechanical energy to the wheels, efficiency is preserved during sustained high-speed driving or long-distance cruising.

3. Architecture of A plug-in Parallel hybrid electric vehicle (series PHEV or range-extended EV)

Additionally,theelectricmotorprovidesvaluablesupport during transients, allowing engine downsizing without compromisingperformance.Thissynergymakesitpossible toachievecomparableorbetterperformancewithsmaller batteries than those required in series PHEVs, thereby lowering cost, reducing vehicle weight, and improving packaging. From an operational standpoint, the electric motorprovidesquiet,emission-freeoperationduringshort trips, while the ICE ensures confidence for long-distance driving,mitigatingrangeanxietycommonlyassociatedwith BEVs.

Nonetheless,theparalleldesignintroducesimportanttradeoffs.BecausetheICEremainsmechanicallyengagedwiththe wheels,itoperatesacrossawiderangeofspeedsandloads, which can reduce average efficiency compared to a series

designwheretheengineoperateswithinanarroweroptimal range.Transientconditions,suchasfrequentaccelerations, may also generate higher emissions unless carefully managed by the EMS. The complexity of transmissions, clutches, and torque-splitting mechanisms adds both technicalandeconomicchallenges,raisingconcernsabout long-termdurability,systemreliability,andmanufacturing cost. Furthermore, the environmental benefits of parallel PHEVsarestronglydependentonchargingfrequency.When owners consistently charge the vehicle and maximize electricdriving,real-worldfuelsavingsandCO₂reductions align closely with laboratory predictions. However, infrequentchargingresultsingreaterICEuse,significantly reducingtheenvironmentaladvantages.

Empirical studies emphasize the importance of the utility factor the proportion of kilometers driven on electricity relative to total kilometers. High utility factors, achieved through daily charging, substantially reduce fuel use and emissions,whilelowutilityfactorsdiminishthesegains.For example,vehicleswith~15kWhbatteriesrechargeddaily can reduce fuel consumption by nearly 70% compared to hybrid counterparts, but these benefits fall sharply when chargingisirregular.Advancedpredictivecontrolstrategies thataccountfordrivingroutes,trafficconditions,anddriver behaviorcanenhanceelectricdriveutilizationandminimize fuelconsumption,highlightingthecriticalroleofintelligent EMSdesign.

From a broader sustainability perspective, parallel PHEVs often provide a practical compromise between BEVs and conventionalICEvehicles.Theirsmallerbatteriescompared toBEVsreducedependenceoncriticalrawmaterialssuchas lithium, cobalt, and nickel, lowering environmental and supply chain concerns associated with large-scale battery production.Atthesametime,theyoutperformconventional ICEvehiclesintermsofefficiency,especiallyinurbandriving environments. However, lifecycle analyses reveal that the overallenvironmentaladvantageofparallelPHEVsishighly context-dependent, influenced by regional grid carbon intensity,typicaldrivinghabits,andcharginginfrastructure availability.

Table1illustratesacomparativeanalysisbetweentheseries andparallelarchitecturesofplug-inhybridelectricvehicles (PHEVs).

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Feature Series PHEV

Parallel PHEV (electric-onlymode) speeds(ICEand motorcombined)

Battery Dependence

Highlydependenton batteryforpropulsion

Regenerative Braking Efficient;onlyelectric motorused

Canoperatewith smallerbattery;ICE assists

Efficient;motorand ICEcanassist

Control Strategy Easier;motoralways driveswheels Requirescoordinated ICE-motorcontrol

Cost Generallylower mechanicalcost

Best Use Case Urbancommuting, frequentstop-and-go traffic

Higherduetodual powerpath components

Mixeddriving,longdistance,high-speed travel

Table 1. Comparative analysis between the series and parallel architectures of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs).

Inregionswithcleanerelectricitygridsandstrongcharging infrastructure, parallel PHEVs contribute substantially to reducinggreenhousegasemissions.Conversely,inregions withcarbon-intensivegridsorpoorchargingpractices,their benefitsdiminish.

TheseriesPHEVreliesprimarilyonthe electricmotorfor propulsion, with the internal combustion engine (ICE) generating electricity, making it highly efficient in urban, stop-and-go driving conditions. In contrast, the parallel PHEVallowsboththeICEandelectricmotortodirectlydrive thewheels,offeringbetterefficiencyathigherspeedsandon long-distance travel. The table highlights differences in power flow, mechanical complexity, battery dependence, regenerative braking, control strategies, cost, and optimal usecases,providinga clearoverviewofthestrengths and limitationsofeacharchitecture.

ThisstudypresentsadetailedcomparativeanalysisofPlugin Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs) and Battery Electric Vehicles(BEVs),withparticularemphasisonthedistinctions betweenseriesandparallelPHEVarchitectures.Theanalysis incorporates multiple performance and sustainability metrics, including Well-to-Wheel (WTW) efficiency, component-level energy losses, lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, regenerative braking effectiveness, thermalmanagementefficiency,andtotalcostofownership (TCO), providing a comprehensive understanding of the technological trade-offs inherent in these powertrain systems. BEVs exhibit higher WTW efficiencies, typically ranging between 70% and 90%, primarily due to their simplified electric-only propulsion and the absence of

conversion losses associated with internal combustion engines(ICEs).Thedirectenergytransferfromthebattery tothemotorminimizesintermediatelosses,enablinghigh overall drivetrain efficiency, particularly under urban driving conditions characterized by frequent acceleration anddecelerationcycles.Incontrast,PHEVs,owingtotheir dual-sourcepropulsionsystem,demonstratereducedoverall efficiency, as energy conversion between ICE-generated mechanical or electrical power and the traction motor introduces significant losses. In series PHEVs, the ICE functionsexclusivelyasageneratortochargethebatteryor supplypowertotheelectricmotor,resultingincumulative energy conversion inefficiencies, whereas parallel PHEVs allowboththeICEandelectricmotortocontributetorque directly to the wheels, reducing energy wastage in highspeed cruising but introducing additional mechanical complexityandcontrolrequirements.

Fromanenvironmentalperspective,lifecycleGHGemissions offercriticalinsightsintothesustainabilityimplicationsof vehicle electrification. BEVs charged from low-carbon or renewable electricity sources achieve near-zero tailpipe emissions and substantially reduced lifecycle emissions. However, in regions with a fossil fuel-dominated grid, the relative advantage of BEVs diminishes, highlighting the dependence of environmental performance on the energy mix. PHEVs provide a balanced solution by combining electric-onlyoperationforshort-rangeurbantripswithICEbased propulsionfor extendedtravel,yettheseriesPHEV configuration often results in higher emissions than the parallelconfigurationduetothecontinuousoperationofthe ICEfor electricitygeneration,whereasparallel PHEVscan leverage electric propulsion in low-load scenarios and switch to ICE assistance only when efficiency gains are maximized.Additionalenvironmentalconsiderationsinclude thermal management and regenerative braking effectiveness;seriesPHEVsbenefitfromsimplifiedthermal loadsontheICEbutrequirerobustbatterycoolingtohandle high charge-discharge cycles, whereas parallel PHEVs distribute energy loads across two propulsion sources, moderating thermal stress and enabling more efficient regenerativeenergyrecoveryduringbrakingevents.

EconomicevaluationthroughTCOanalysisrevealsfurther distinctionsbetweenthetechnologies.BEVsgenerallyincur higherupfrontcostsdrivenbylarge-capacitybatterypacks andassociatedpowerelectronics,buttheseareoffsetover time by lower operational and maintenance expenditures duetotheabsenceofconventionalICEcomponents,reduced lubricationrequirements,andfewermovingparts.PHEVs, whileexhibitinglowerinitialacquisitioncosts,facehigher operational expenses associated with dual powertrain maintenance, ICE servicing, and more complex electronic control systems. Within PHEV configurations, series architectures typically impose additional maintenance burdens due to the inclusion of generators, power converters, and auxiliary electronics, whereas parallel

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

architectures, with mechanically coupled ICE and motor systems,presentlowerincrementalcomplexitybutrequire advancedcontrolstrategiestooptimizeenergysharingand torque delivery under varying driving conditions. Market suitabilityishighlydependentonusagepatterns:BEVsexcel in urban, short-range scenarios with well-developed charging infrastructure, enabling frequent utilization of electric-only mode, whereas PHEVs offer operational flexibility for users with mixed urban and highway travel requirements,mitigatingrangeanxietyandprovidingenergy source redundancy. Parallel PHEVs are particularly advantageousinhighway-dominanttravelduetoimproved high-speed efficiency and reduced reliance on battery capacity, while series PHEVs remain suitable for predominantly urban applications where electric-only operationcanbemaximized.

In summary, the comparative evaluation underscores the multifactorialnatureofvehiclepowertrainperformanceand the necessity of aligning architecture selection with operational context, energy availability, and sustainability objectives. While BEVs offer superior electric propulsion efficiencyandenvironmentalperformanceunderfavorable gridconditions,PHEVsprovidestrategicflexibility,enabling atransitionarypathwaytowardlow-emissionmobilitywhile addressing practical limitations related to range and charging infrastructure. The series and parallel PHEV architectures each present unique trade-offs in terms of energy conversion efficiency, emissions, thermal management,regenerative braking potential,andlifecycle costs,emphasizingtheimportanceofinformeddesignand control strategies to optimize the performance and environmentalfootprintofhybridelectricmobilitysolutions. Future research should focus on advanced energy managementalgorithms,predictivecontrolstrategies,and integrationwithrenewableenergysourcestoenhancethe operationalefficiencyandecologicalbenefitsofhybridand electricvehicletechnologies.

This study elucidates the comparative performance of BatteryElectricVehicles(BEVs)andPlug-inHybridElectric Vehicles(PHEVs),withemphasisonseriesandparallelPHEV architectures.BEVsdemonstratesuperiorenergyefficiency, lower lifecycle emissions, and reduced maintenance demands, particularly suited for urban, short-range operation. PHEVs offer enhanced operational versatility, balancing electric propulsion with internal combustion support to extend range and accommodate mixed driving conditions. Within PHEVs, series architectures optimize electric-only operation in low-speed scenarios, whereas parallel architectures achieve higher efficiency and performance under high-speed, long-distance travel. The analysis highlights that vehicle selection and architecture design must consider driving patterns, energy efficiency,

emissions,andlifecyclecosts,emphasizingthecriticalroleof strategic powertrain integration in advancing sustainable mobilitysolutions.

[1] P.JuanTorreglosa,PabloGarcia-Trivi˜no,DavidVera,A. Diego L´opez-García, Analyzing the improvements of energymanagementsystemsforhybridelectricvehicles usingasystematicliteraturereview:howfararethese controlsfrom rule-basedcontrolsusedincommercial vehicles?Appl.Sci.10(23)(2020)8744.

[2] C.Sun,F.SunF,H.He,Investigatingadaptive-ECMSwith velocityforecastabilityforhybridelectricvehicles,Appl. Energy185(2017)1644–1653.

[3] C.Samanta,S.Padhy,S.Panigrahi,B.Panigrahi,Hybrid swarmintelligencemethodsforenergymanagementin hybrid electric vehicles IET Electr Syst Transp 3 (1) (2013)22–29.

[4] P.K. Gujarathi, V.A. Shah, M.M. Lokhande, Hybrid artificial bee colony-grey wolf algorithm for multiobjective engine optimization of converted plug-in hybridelectricvehicle,AdvancesinEnergyResearch7 (1)(2020)35–52.

[5] T. Gowrishankar, A. Nirmal Kumar, Improving the performance of a parallel hybrid electric vehicle by heuristiccontrolmethod,J.Electr.Eng.18(2018)236–247.

[6] L.Serrao,S.Onori,G.Rizzoni,Acomparativeanalysisof energy management strategies for hybrid electric vehicles, J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 133 (3) (2011) 031012.

[7] Y. Huang, H. Wang, A. Khajepour, H. He, J. Ji, Model predictive control power management strategies for HEVs:areview,J.PowerSources341(2017)91–106.

[8] Y.Huang,H.Wang,A.Khajepour,B.Li,J.Ji,K.ZhaoK,C. Hu, A review of power management strategies and componentsizingmethodsforhybridvehicles,Renew. Sustain.EnergyRev.96(2018)132–144.

[9] O. Yeniay, Penalty function methods for constrained optimization with genetic algorithms, Math. Comput. Appl.10(1)(2005)45–56.

[10] N. Belen Arouxet, Echebest Elvio, A Pilotta Active-set strategy in Powell’s method for optimization without derivatives,Comput.Appl.Math.30(1)(2016)171–196.

[11] M.BenAli,G.Boukettaya,Optimalenergymanagement strategiesofaparallelhybridelectricvehiclebasedon differentofflineoptimizationalgorithms,International

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 09 | Sep 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Journal of Renewable Energy Research-IJRER 10 (4) (2020).

[12] A. V. Katode and S. Gupta, "AI and IoT Integration in PediatricPhototherapy: RevolutionizingApproachfor NeonatalCare,"202517thInternationalConferenceon Electronics,ComputersandArtificialIntelligence(ECAI), Targoviste, Romania, 2025, pp. 1-7, doi: 10.1109/ECAI65401.2025.11095609.

[13] D.-D. Tran, M. Vafaeipour, M. El Baghdadi, R, Barrero Fernandez,J.VanMierlo,O.Hegazy,O,Thoroughstateof-the-art analysis of electric and hybrid vehicle powertrains: topologies and integrated energy management strategies, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 119(2020)(2020).

[14] Fredrikbaberg & Elliotdahl, Optimization of Fuel Consumption in Hybrid Electric Vehicles, Master of ScienceSchool,Stockholm,Sweden,2013.MScThesis.

[15] S. Zhang, R. Xiong, Adaptive energy management of a plug-inhybridelectricvehiclebasedondrivingpattern recognitionanddynamicprogramming,AppliedEnergy Journal155(2015)68–78.

[16] K. Namwook, C. Sukwon, P. Huei, Optimal control of hybridelectricvehiclesbasedonPontryagin’sminimum principle, control systems Technology, IEEE Transactions19(5)(2011)1279–1287.

[17] Mr. AKASH V. KATODE, PROF Dr. A. O. VYAS “Multipurpose Agriculture Pesticide Sprayer Robot (SprayRo)” International Research Journal of EngineeringandTechnology(IRJET),Volume:10Issue: 03|Mar2023

[18] D. Edward Tate, P. Stephen Boyd, Finding Ultimate Limits of Performance for Hybrid Electric Vehicles, Society of Automotive Engineers, FTT-50, Stanford University,1998.

[19] Trattner,A.,Pertl,P.,Schmidt,S.,Sato,T.,“NovelRange Extender Concepts for 2025 with Regard to Small Engine Technologies”, SAE International Journal of AlternativePowertrains,1(2):566-583,(2012).

[20] Fraidl,G.,Beste,F.,Kapus,P.,Korman,M., “Challenges and Solutions for Range Extenders - From Concept Considerations to Practical Experiences”, Highlighting the Latest Powertrain, Vehicle and Infomobility Technologies,Turin,1-2,(2011).

[21] Borthakur, S., Subramanian, S.C., “Design and optimizationofamodifiedserieshybridelectricvehicle powertrain”, Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering,233(6):1419-1435,(2019).

[22] Chen,B.C.,Wu,Y.Y.,Tsai,H.C.,“Designandanalysisof powermanagementstrategyforrangeextendedelectric vehicleusingdynamicprogramming”,AppliedEnergy, 113:1764-1774,(2014).

[23] Fang, Y., Zhao, H., Peng, Q., Liu, S., “Research on generator set control of range extender pure electric vehicles”, Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference,Chengdu,1-4,(2010).

[24] Mackintosh, T., Tataria H., Inguva S.,” Energy storage system for GM volt-lifetime benefits”, IEEE Vehicle PowerandPropulsionConference,Dearborn,321-323, (2009).

Name:Mr.AkshayR.Khadse AssistantProfessor,P.R.PatilCollegeof Engineering&Technology,Amravati. Education:Diploma(E.E.),B.E.(E.E.)M.E. (ElectricalPowerSystem)

Email:akshay.drgitrdiploma@gmail.com

Name: Mr.AkashV.Katode DeputyManagerMyraAcademy Education: B.E.(ExTC),M.Sc.(Electronics Instrumentation), MTech (VLSI & Embedded)

Email:Katodeakash@gmail.com

© 2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page273