A Toronto block by BDP Quadrangle, Stantec, Two Row, and ERA Architects includes an Indigenous health centre, skills training facility, heritage structure, and residential buildings. TEXT Elsa Lam

Lapointe Magne et associés and L’OEUF Architectes’ municipal hub creates a vibrant civic centre for a Montreal suburb. TEXT Odile Hénault

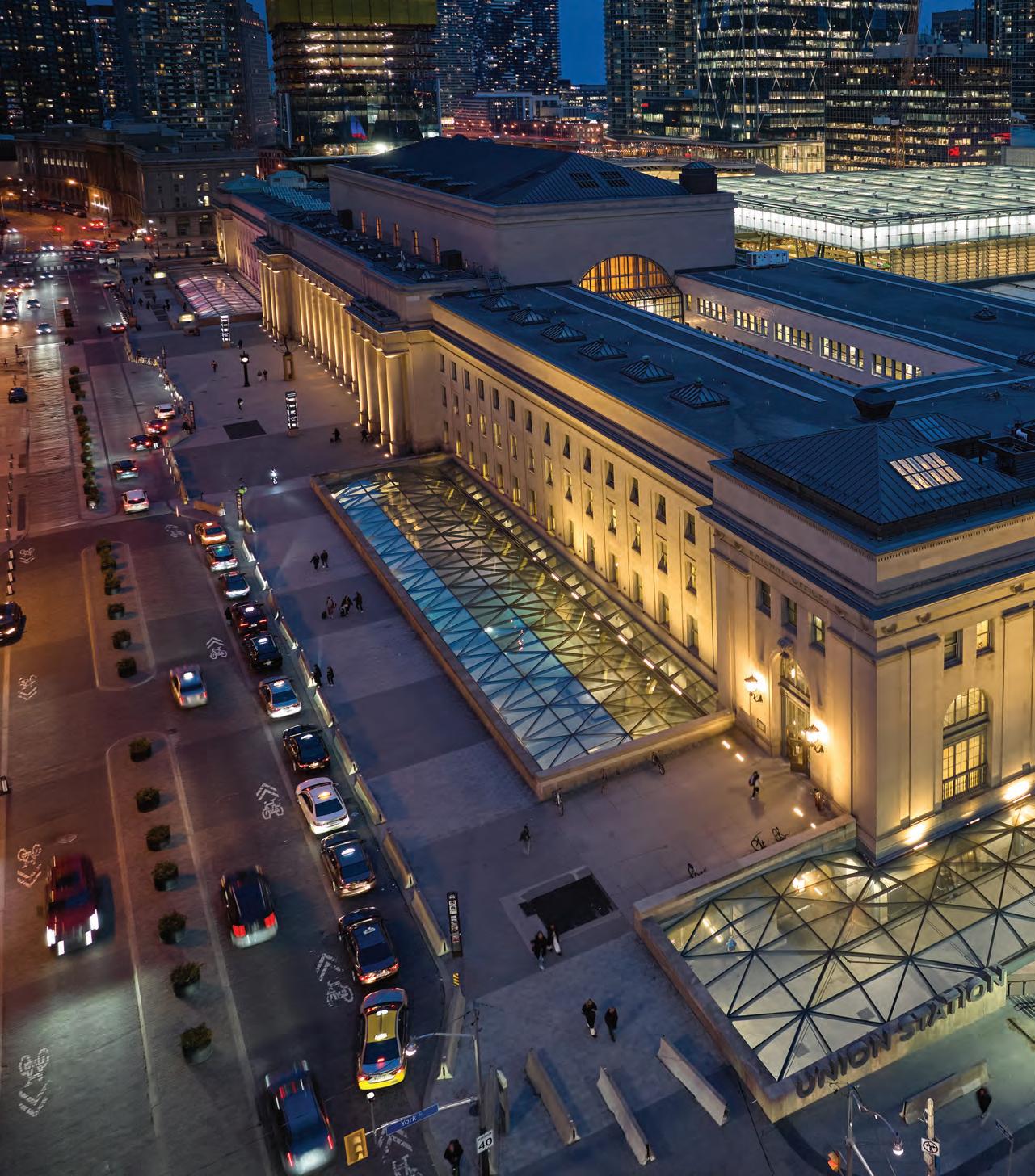

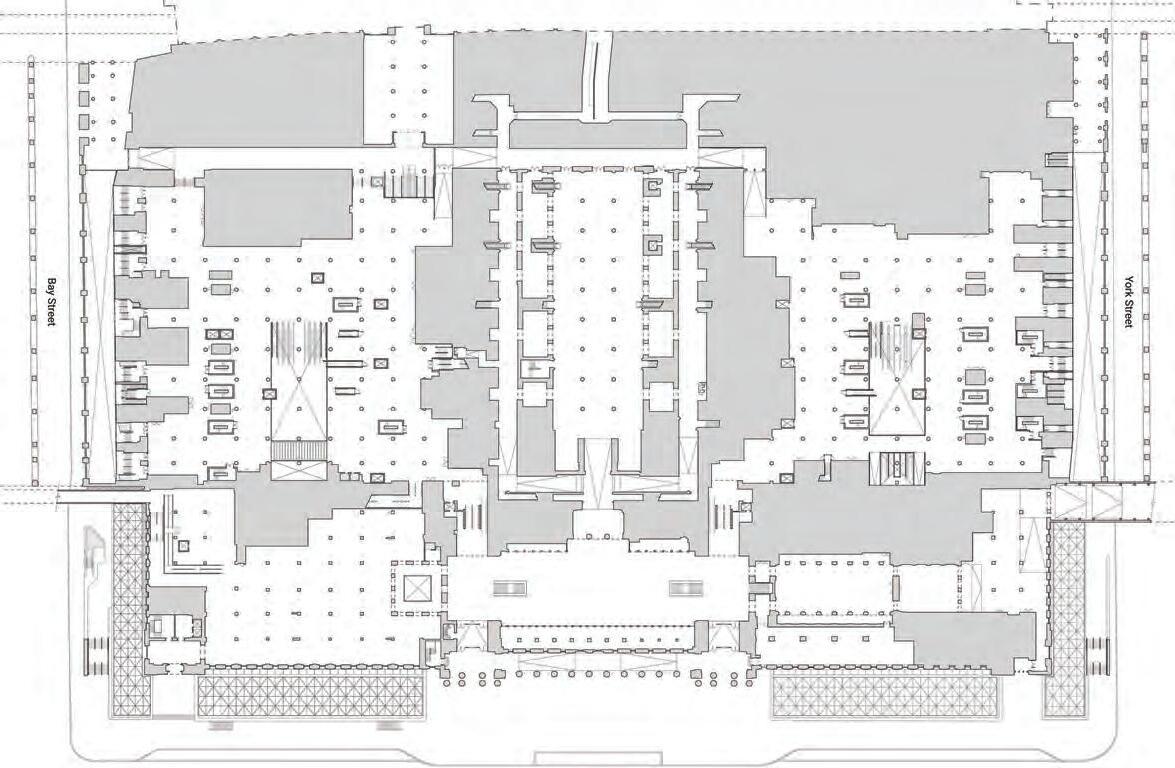

A comprehensive overhaul of Toronto’s Union Station, led by NORR Architects & Engineers with heritage architects EVOQ Architecture, positions Canada’s largest multi-modal transportation node to handle over 130 million passengers annually. TEXT Pamela Young

4 VIEWPOINT

Ontario Place heads to the Supreme Court.

6 NEWS

AFBC winners, Edmonton Urban Design Award winners.

9

Larry Wayne Richards pays tribute to the late Frank Owen Gehry (19292025).

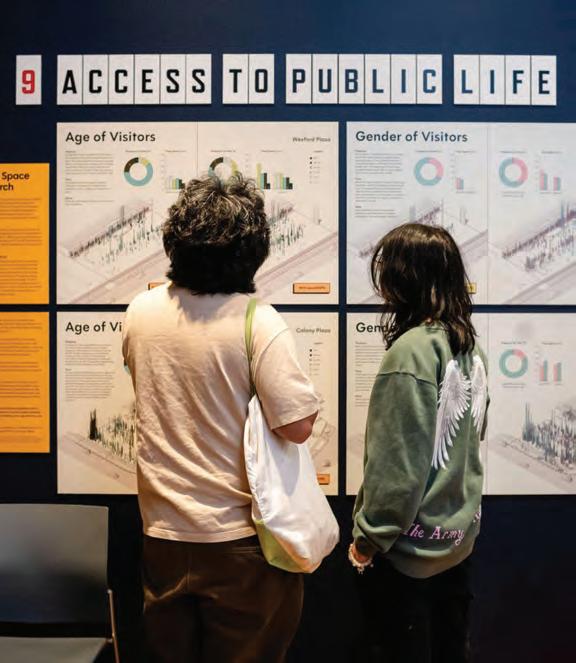

Annual progress report; community engagement process results.

Landscape architect and public space advocate Brendan Stewart on how plazaPOPS is moving from one-off installations to becoming a facilitating institution.

47

David Winterton’s new book examines the life and work of Edwardian Toronto architect Frank Darling.

50

Our picks from last fall’s Feria Hábitat València.

52

The late Richard Johnson’s photos document the winter infrastructure of Canada’s ice fishing huts.

COVER Union Station, Toronto, Ontario, by NORR Architects & Engineers with heritage architects EVOQ Architecture. Photo by doublespace photography.

Canada’s Supreme Court will be hearing a challenge to a key piece of a legislation enabling Premier Doug Ford’s redevelopment of Ontario Place.

Occupying a series of man-made islands on Toronto’s waterfront, Ontario Place originally opened in 1971 as a provincial counterpart to Montreal’s Expo 67. It featured mega-structural pods and the world’s first permanent IMAX theatre, both designed by Eberhard Zeidler, and set in a naturalized landscape by Michael Hough.

The Province’s plans to redevelop the site have faced widespread criticism for turning over a large part of the site to an Austrian waterpark developer, Therme, which has signed a 95-yearlease to create a stadium-sized indoor waterpark and spa on the west part of the islands. The award of the contract came under scrutiny from Ontario’s auditor general, and Therme has been the subject of investigative reports from both the New York Times and Toronto Star bringing its finances into question.

Another casualty of the redevelopment plans is the Moriyama Teshima-designed Ontario Science Centre, which was shuttered in 2024 on the false premise that its roof was faulty. (The engineer’s report used to support the decision did not call for a full closure). The planned relocation of the Science Centre to a new, halfsized facility at Ontario Place is at least in part intended to justify the construction of a site-wide parking solution—current plans call for a mallsized aboveground structure on the waterfront.

Because of the Rebuilding Ontario Place Act (ROPA), a piece of legislation passed hurriedly in late 2023, the Province’s redevelopment plans for Ontario Place aren’t required to adhere to standard environmental or heritage regulations, or to follow municipal processes. The Ontario government has also used ROPA to insulate itself and its agents against civil lawsuits that may arise as a result of redevelopment activities.

A coalition of organizations and advocates named Ontario Place Protectors has been calling for the overturn of ROPA , saying that its broad immunity clauses are legal overreach that violate Canada’s constitution. The group also argues that removing the site from environmental and heritage protections is a breach of public trust—a legal doctrine that suggests that the site ultimately belongs to the people of Ontario, and is held in trust by the Government of Ontario.

Ontario Place Protectors has so far unsuccessfully challenged ROPA in the Ontario Superior Court and the province’s Appeal

Court. Last May, the group applied for leave for its case to be heard at Canada’s Supreme Court. It was granted in early January, 2026.

The Supreme Court only hears cases that it deems to be of significant public or national importance. Ontario Place Protectors writes that more than 90 percent of cases put forward to the Supreme Court are not selected to be heard. “At a minimum, having our case accepted is recognition of an issue that has national repercussions,” the group writes. “Left unchallenged, [ROPA] will give the Ontario premier and cabinet a template to ignore Ontario’s heritage, environmental, and planning laws—and their responsibility to the public—anywhere in the province.” They add, “In fact, similar provisions to ROPA are in Ontario’s Bill 5 and Federal Bill C-5.”

As of yet, there is no injunction in place that would force work on Ontario Place to be paused until the Supreme Court hears the case. And it may be too late to reverse the damage already done at Ontario Place. In 2024, over 850 trees were removed overnight to clear the West Island, the site of Therme’s future waterpark. (The Ontario government paid $40.4 million to speed up this demolition—a $30-$35 million premium over their initial estimates of $5-10 million for this work.) An RFP process has been initiated to construct a 3,500-spot, five-level aboveground parkade. The designers of a new Ontario Science Centre at Ontario Place are expected to be announced this spring. The Province has extended ROPA to cover the CNE grounds—suggesting that parts of the project may take place in this municipal property, without requiring buy-in from the City of Toronto.

But even bigger issues may now be at stake, going beyond the Ontario Place and CNE sites, as large as they are, to other potential developments in Ontario and Canada—and getting to issues at the heart of our democracy. Can governments fast-track developments by providing blanket immunity against civil liability? Do governments have the obligation to treat prominent sites as being held in public trust? Must governments respect environmental and heritage laws intended to protect the integrity of such sites?

We’ll be watching closely for the answers as Ontario Place Protectors’ case is heard at the Supreme Court this fall.

The winners of the AFBC Architectural Awards of Excellence, the highest level of architectural awards in British Columbia, were announced on October 27, 2025, at the Vancouver Club.

The Architecture Foundation of British Columbia (AFBC) is a nonprofit organization that advocates for the advancement of architecture and design in the province. The Architectural Awards of Excellence are held bi-annually, and recognize projects built in BC by BC architects.

This year, two Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia Awards in Architecture were given. The winners are Northern Secwepemc Cultural Centre in 100 Mile House by McFarland Marceau Architects Ltd. and The Butterfly + First Baptist Church Complex in Vancouver by Revery Architecture Inc.

Design Awards of Excellence went to s q lxen m ts’exwts’áxwi7 –Rainbow Park in Vancouver by DIALOG, Hall Street Pier in Nelson by Stanley Office of Architecture (Architect of Record) and the marc boutin architectural collaborative inc. (Urban Design), t m sew’tx w Aquatic and Community Centre in New Westminster by hcma architecture + design, s itw nx Child Care at UBC Okenagan by PUBLIC Architecture + Design, Focal on 3rd in North Vancouver by PH 5 Architecture Inc., Sala Apartments in Vancouver by office of mcfarlane biggar architects + designers inc., The Granary at Southlands in Tsawwassen by MOTIV Architects Inc., Arbour house by Patkau Architects, Fluevog House in Vancouver by Marianne Amodio and Harley Grusko Architects Inc., Monos Flagship in Vancouver by Leckie Studio Archi-

ABOVE The Northern Secwepemc Cultural Centre in 100 Mile House, BC, by McFarland Marceau Architects Ltd., was the winner of a Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia Award in Architecture.

tecture + Design Inc., and Kicking Horse Café in Invermere by the marc boutin architectural collaborative inc.

The Bing Thom Legacy Award for Architectural Excellence went to Fraser Mills Presentation Centre in Coquitlam by Patkau Architects. Innovation awards went to Chief Leonard George Building in Vancouver by GBL Architects and 105-Storey Zero Carbon Hybrid Wood Tower Prototype and Hybrid Timber Floor System (HTFS) by DIALOG. Equity awards were garnered by Daylu Dena Council Multipurpose Cultural Centre in Lower Post by Scott M. Kemp Architect, and by Masque: A Modern Beaux-Arts Ball, led by Field Collective, PH5 Architecture Inc., Atmospheric Perspective Architecture Inc., Twobytwo Architecture Studio Ltd., WNDR Architecture + Design Inc., MOTIV Architects Inc., and Tony Osborn Architecture + Design Inc. with performers Mx Bukuru, Sabrina the Teenage Bitch, PM, SKIM, Maiden China, and Batty Banks.

An Unbuilt Award went to Mariners Park Community Bandshell in Prince Rupert by Atmospheric Perspective Architecture Inc. The Emerging Firm Award was given to Eitaro Hirota Architecture Inc. Special Jury Awards were bestowed on Broadhurst & Whitaker Block in Vancouver by Marianne Amodio and Harley Grusko Architects Inc., and on the Museum of Anthropology Great Hall Seismic Renewal in Vancouver by Nick Milkovich Architects Inc. www.architecturefoundationbc.ca

The 2025 Edmonton Urban Design Awards winners have been announced. Award of Excellence winners include Station Park by HSEA Architecture, Roundhouse Park at Station Lands by DIALOG, The Stacks by Thomas Perl, e4c by Dub Architects, Calder Corner Store Public Realm Improvements by by Green Space Alliance with contributor WSP, 105 Avenue (Columbia Avenue) Streetscape by AECOM, Touch the Water Promenade by Dub Architects with Stoss Landscape Urbanism, Northeast River Valley Park Strategic Plan by Public City Architecture, A Mischief of Could-be(s) and UGO by Edmonton Arts Council, Erin Pankratz + Christian Peres Gibaut (Red Knot Studio), Lulu Lane by hcma architecture + design with contributors Jamelle Davis, Macha Abdallah and Bashir Mohamed, and student project Winter City Urbanism by Danielle Soneff. Awards of Merit were given to Coronation Park Sports and Recreation Centre by hcma architecture + design and Dub Architects in collaboration with FaulknerBrowns, Jasper Place Bowl by Dub Architects, Point Access Blocks by Dub Architects, Inglewood Lofts by Dub Architects, Centennial Plaza Rehabilitation by MBAC with contributor PFS Studio, Okîsikow (Angel) Way by Al-Terra Landscape Architecture, Klondike

Park Redevelopment by groundcubed, Parallax by Next Architecture, Fort Edmonton Park by DIALOG, and student project Established Neighbourhoods Revitalization Master Plan by Neil Roy Choudhury, Gabriella Dunn, Shirley Le-Huynh, and August Millan.

An Honorable Mention went to Lauderdale Terrace by DIALOG (formerly RPK Architects), and the People’s Choice Award was bestowed on POLYKAR Edmonton by FARMOR Architecture. www.edmonton.ca

WW+P and SvN merge

UK-based firm WW+P and Canadian firm SvN have announced the merger of their practices. The new practice will integrate planning, urban design, landscape, and architecture.

Headquartered in London, England, WW+P, formerly Weston Williamson + Partners, is a leader in the design and delivery of architecture, urban design, and masterplanning for city-shaping projects. Headquartered in Toronto, SvN is a multidisciplinary regenerative design practice, with projects across Canada and worldwide. Both practices boast experience in transit-oriented development and transport infrastructure.

The joint practice will encompass 12 combined global studios. It will adopt the name and branding of WW+P, under the stewardship of 10N Collective, a collective of urbanism, architecture and related design experts brought together by French company Egis Group. Egis Group operates in 100 countries and has 19,500 employees. www.wwparchitects.com

ACROVYN WALL PROTECTION

ACROVYN WALL PROTECTION

ACROVYN DOORS

ACROVYN DOORS

PRIVACY CURTAINS + TRACK

PRIVACY CURTAINS + TRACK

ARCHITECTURAL LOUVERS

ARCHITECTURAL LOUVERS

ARCHITECTURAL SCREENS

ARCHITECTURAL SCREENS

SUN CONTROL SOLUTIONS

SUN CONTROL SOLUTIONS

ENTRANCE FLOORING SOLUTIONS

ENTRANCE FLOORING SOLUTIONS

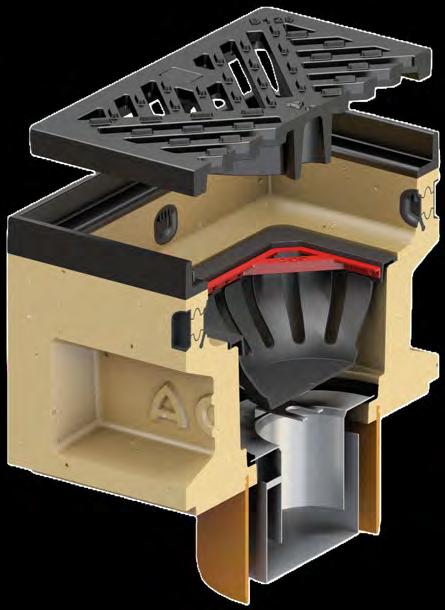

EXPANSION JOINT SOLUTIONS

EXPANSION JOINT SOLUTIONS Find A Solution

JUNO™ 95/30 MINERAL FIBER HIGH-NRC PANELS

Juno ™ ceiling panels are the newest breakthrough addition to CGC’s 0.95 NRC mineral fiber collection. Combining best-in-class acoustic performance and smooth texture design with durable, encapsulated edges, Juno ™ panels help create attractive and sustainable spaces.

TEXT Larry Wayne Richards 1929–2025

Toronto-born architect Frank Owen Gehry was 96 when he died on December 5, 2025. He practiced architecture for 71 years, reaching the pinnacle of his profession. He received the Pritzker Prize, the AIA Gold Medal, the RAIC Gold Medal, the RIBA Gold Medal, the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom, and honorary degrees from 20 universities, the latter including the Technical University of Nova Scotia (Dalhousie) and the University of Toronto. As an architect, he was bold, sometimes brazen. As a friend for nearly 45 years, he was loving and generous.

I met Frank through Globe and Mail architecture critic Adele Freedman, soon after I moved from Halifax to Toronto, in 1980. Adele and I were drawn to Frank’s imaginative form making and unconventional use of ordinary materials. We revelled in his openness and rebellious nature, and we went to Los Angeles to see his work first-hand. Frank and his wife, Berta, invited us to their house in Santa Monica, a remarkable, other-worldly renovation completed in 1978. We had dinner while their boys, Samuel and Alejandro, played in the background.

Soon, Adele and I made more trips to L.A. to see work by Frank: the Temporary Contemporary, Rebecca’s restaurant, Loyola Law School, Santa Monica Place, the Aerospace Museum, and the shocking Chiat Day “binoculars building.” We marvelled over Frank’s Formica fish and snake lamps, forerunners of his later fish-like constructions, emanating, it seems, from

memories of his Jewish grandmother bringing a carp home to make gefilte fish and his desire to instill Baroque-like movement into architectural forms.

In those days in the 1980s, Adele and I often felt alone in our attraction to Frank’s architecture. Some Toronto architects and academics at that time were hostile towards his work, engaging in a kind of class snobbery—and even going so far as attempting to thwart a 1981 invitation for Frank to lecture in Toronto. (They didn’t succeed.) Amidst the conservative resistance, Adele and I soldiered on, feeling privileged to be part of Frank’s world.

Fast forward: Capping four decades of engagement with Frank, we had lunch with him at his office in September 2024, joined by his chief of staff Meaghan Lloyd. Frank’s son, Sam, now an accomplished designer, toured us around the office. Adele and I had a wonderful afternoon, not knowing that, sadly, it would be our last time with Frank.

Now, reflecting on Frank’s monumental legacy and iconic projects such as the Guggenheim Bilbao Museum and Disney Concert Hall, I’m even more in awe of his creativity and his complex, highly particular intersection of architect-artist sensibilities. Finally, what was it all about? Frank once commented that “I think all of us are, finally, just commenting in our own way about what’s going on in our cone of vision.” In his case, that was a kind of profound, abstract yet intensely material mocking up of life as he experienced it—starting in Toronto and ending in Santa Monica.

Although Frank Gehry became well known internationally in the early 1980s, opportunities for projects in his native Canada unfolded slowly. In the mid-80s he was considered for Toronto’s Metro Hall as part of a proposal by Olympia & York and Adamson Associates. “Frank’s scheme was fantastic,” recalls Ron Soskolne, a long-time friend of Gehry’s and O&Y Vice-President at the time. “However, the Harbourfront site was controversial politically, and our vision didn’t fly. It was disappointing.”

Another non-start centered on the Montreal Museum of Decorative Arts (MMDA), which opened in 1979 and by 1988 quickly outgrew its home. Around 1991, the museum’s director, Luc d’Iberville-Moreau, noted in an exhibition catalogue preface that “At present we are working with the Canadian-born architect Frank Gehry to develop designs for a new facility. Our expectations are that he will design a remarkable setting for our collections and a structure that will add a notable presence to the city of Montreal.”

Although the MMDA , working with Knoll, presented the exhibition, “Frank Gehry: New Bentwood Furniture Designs” in the fall of 1992, the hoped-for new museum by Gehry never materialized.

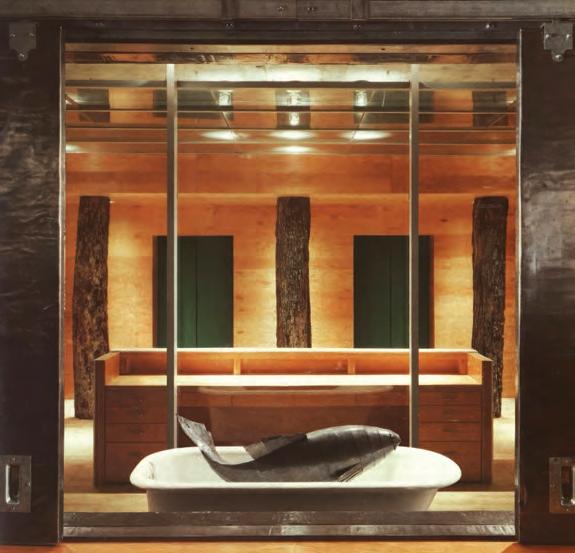

Frank’s first realized project in Canada was a suite of offices for the Los Angeles-based advertising firm Chiat Day, completed in Toronto in March 1989. It was an interior project on the sixth and seventh floors of a squat, mirror-glazed building at 10 Lower Spadina, near the lakefront. Designed in collaboration with Toronto architect David Fujiwara, the Chiat Day offices

combined plywood, tree trunks, crumpled steel, wool felt, and a focal, disconcertingly real-looking fish in a bathtub. It was a warm, witty, elegant place. An image of it was featured on the cover of the May 1989 issue of Canadian Architect, which included my review of the project.

In the 1990s, I went to see projects by Gehry in Cincinnati, Cleveland, Prague, and Seattle. The Nationale-Nederlanden Office Building in Prague, completed in 1996, became one of my favourites. Located along the Vltava River in the central historic district, twin corner towers, affectionately nicknamed “Ginger and Fred” after the famous Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire Hollywood dancing couple, flow into a long, undulating façade scaled superbly to the urban context.

For the Prague building, Frank’s office employed 3-D computer modelling to, as his office put it, “link the design process more closely to fabrication and construction technologies as opposed to the imaging software more typically used by architects.” Technological innovation became increasingly important for Gehry Partners and their subsidiary Gehry Technologies. They adopted Computer-Aided Three-Dimensional Interactive Application (CATIA) from aerospace engineering, eventually developing Digital Project, a platform that advanced BIM and complex geometric coordination.

The highly sculptural, magnificent Guggenheim Bilbao Museum opened in 1997, followed by Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. Meanwhile, Frank was working on his cloud-like design for

ABOVE LEFT In 1996, Gehry completed an exuberant office building for Dutch insurance company Nationale-Nederlanden. Early in the design process, he nicknamed the project “Ginger and Fred,” connoting the dancers Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, whose flow he captured in paired towers.

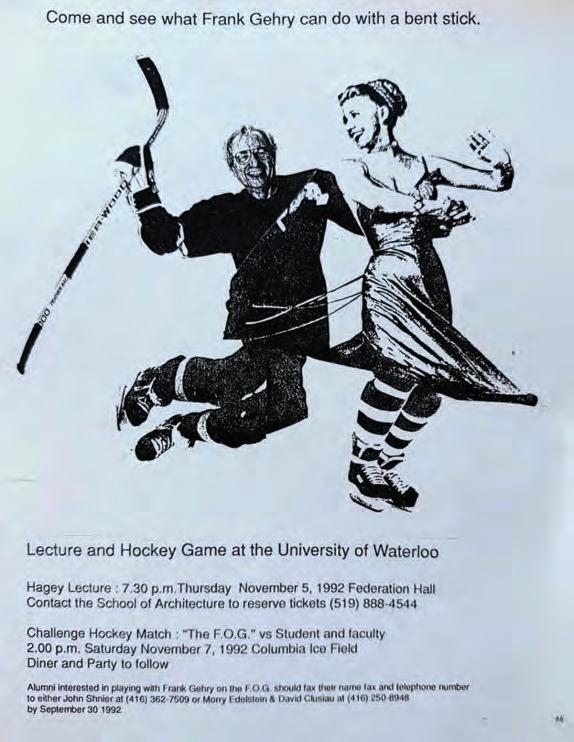

ABOVE RIGHT In a poster for Gehry’s 1992 University of Waterloo visit, alumnus David Clusiau collaged a photo of Frank in hockey gear (from a Knoll advertisement for Gehry-designed bentwood furniture) with a doctored image of Ginger Rogers, alluding to the evolving “Ginger and Fred” project in Prague.

the Le Clos Jordanne winery in Ontario’s Niagara Region, developed during 2002-03 but, disappointingly, unrealized.

This period coincided with my deanship at the University of Toronto from 1997 to 2004, a time when I became even more engaged with Frank and his work. In 1998, I helped steer the University’s awarding of an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree to Frank. Then, in 2002, working closely with alumnus Bruce Kuwabara and others, I enabled our faculty to launch the endowed, Frank Gehry International Visiting Chair in Architectural Design, which has brought stellar architects to teach advanced design studios at U of T. Frank was thrilled with both recognitions from the institution where, as a teenager, he had attended a lecture by the extraordinary Finnish architect, Alvar Aalto.

Then, in 2006, I curated the exhibition Frank’s Drawings: Eight Museums by Gehry ” for the University of Toronto Art Centre and the Patricia Faure Gallery in Santa Monica. The exhibition included his alluring, wiry sketches and an array of telephone-pad/thumbnail sketches by Frank never before shown—scores of yellow sheets piled in Gehry-esque heaps. It made him smile!

Meanwhile, the Gehry-designed transformation of the Art Gallery of Ontario was unfolding with its fish-skeleton-like galleria along Dundas Street, bold blue volume facing Grange Park, and radically changed Walker Court. Completed in 2008, this was Frank’s first major Canadian project.

Soon an even grander Toronto opportunity came to Gehry—a large, mixed-use development, initially launched by David Mirvish, for a site along King Street West. As proposed by Frank, it entailed three soaring residential towers. The City’s planners reduced the ensemble to two towers, Mirvish bowed out, and the developer branded the landmark project

“Forma,” announcing it in their promotional brochure as “A Homecoming Masterpiece Designed by Gehry.” The first tower—74 floors, exuberant, silvery-metallic—is now under construction. The second, taller tower is currently on pause, but Mitchell Cohen, COO of Westdale Construction, says that it will proceed when market conditions are less uncertain. Such uncertainties have pervaded many of Frank’s projects in Canada, but it never seemed to diminish his pride in being Canadian. And sometimes that manifested itself in relatively simple ways. I recall how extremely happy he was in 1992 to be invited to the University of Waterloo, where I was a professor at the time, to lecture, visit a former high school classmate teaching there, and to play hockey! He brought along his own team, The F.O.G., stacked with ex-NHL players, and was totally in his Canadian element. Pure Frank.

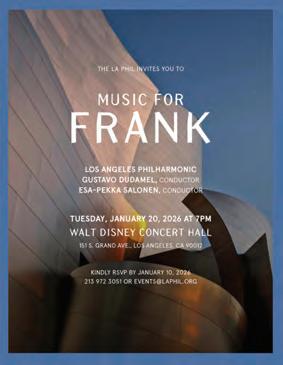

Now, as the curtain falls, family, office colleagues, and friends will gather at Disney Hall on January 20th for a special concert honouring this remarkable man. I will be there, embraced by the warm, wood-lined space that he created and the music that he loved.

TOP The wood-lined interior of the 2003 Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles has both intimacy and superb acoustics.

ABOVE LEFT The stainless-steel-clad hall includes extensive public terraces that wind up and around the building. ABOVE RIGHT Invitation to “Music for Frank” at Disney Hall, January 20, 2026.

The Next Generation of Building Envelope Has Arrived. At Kingspan Insulated Panels, we are pioneering better technologies and methods of building that incorporate superior performance and industry-leading sustainability. From unparalleled aesthetic flexibility and energy efficiency to thermal, air, water and vapor barrier performance, we invite you to meet the future’s favorite façades.

Register Now: 2026 RAIC Conference on Architecture

We’re bringing the architectural community together for four days of education, architectural tours, a reimagined Expo, and several special events. Early bird rates end on March 17. https://conference.raic.org/

Inscrivez-vous dès maintenant : Conférence 2026 de l’IRAC sur l’architecture Nous réunissons la communauté architecturale pour quatre journées de formation, de visites architecturales, d’un Expo réinventé et de plusieurs événements spéciaux. Les tarifs de préinscription prennent fin le 17 mars. https://conference.raic.org/

Elevate your career: Renew your RAIC membership for 2026

Your RAIC membership helps you stay connected, informed, and up to date with the latest developments in the field. Ensure uninterrupted access to exclusive benefits, cost savings, and learning opportunities in 2026 by renewing your RAIC membership. https://raic.org/join/renewal

Propulsez votre carrière : Renouvelez votre adhésion à l’IRAC pour 2026

Votre adhésion à l’IRAC vous permet de rester connecté, informé et à jour sur les plus récents développements dans le domaine. Assurez-vous de conserver l’accès à des avantages exclusifs, à des économies et à des occasions d’apprentissage en 2026 en renouvelant votre adhésion. https://raic.org/join/renewal

Catch Up On Continuing Education

Meet your 2024-2026 continuing education requirements! RAIC’s expert-led courses and convenient webinars keep you licensed, inspired, and at the forefront of architectural innovation. Complete your credits—start learning today. https://raic.org/professional-development/continuing-education/

Rattrapez vos exigences de formation continue Respectez vos exigences de formation continue 2024-2026! Les cours dirigés par des experts de l’IRAC et les webinaires pratiques vous permettent de rester autorisé, inspiré et à l’avant-garde de l’innovation architecturale. Obtenez vos crédits— commencez à apprendre dès aujourd’hui. https://raic.org/professional-development/continuing-education/

February Février 2026

The 2026 RAIC Conference on Architecture is taking place in Vancouver from May 5-8. Register today!

La Conférence 2026 de l’IRAC sur l’architecture aura lieu à Vancouver du 5 au 8 mai. Inscrivezvous dès aujourd’hui!

This issue reflects on the RAIC’s and architecture’s evolving role in shaping Canada’s future. President Jonathan Bisson outlines how the RAIC is translating ambitious vision into concrete action—from climate leadership and Truth and Reconciliation to strengthening our voice in housing policy and public affairs.

Architects should also be at the forefront of exploring innovative construction methods, such as prefabricated precast concrete, as examined by Brian Hall in his article.

Ce numéro porte un regard sur le rôle évolutif de l’IRAC — et de l’architecture — dans la définition de l’avenir du Canada. Le président Jonathan Bisson explique comment l’IRAC traduit une vision ambitieuse en actions concrètes : leadership climatique, vérité et réconciliation, mobilisation en matière de politiques de logement et affaires publiques.

the

environment in Canada, demonstrating how design enhances the quality of life, while addressing important issues of society through responsible architecture. www.raic.org

L’IRAC est le principal porte-parole en faveur de l’excellence du cadre bâti au Canada. Il démontre comment la conception améliore la qualité de vie tout en tenant compte d’importants enjeux sociétaux par la voie d’une architecture responsable. www.raic.org/fr

The RAIC’s comprehensive community engagement process revealed what over 800 architects, interns, and students expect from a national membership organization: clarity, accessible professional development, visible advocacy, and transparent communication.

Together, these pieces help map a path that is more responsive, more relevant, and more aligned with the profession’s diverse needs and Canada’s urgent priorities.

Les architectes doivent également être à l’avant-garde de l’exploration de méthodes de construction novatrices, notamment le béton préfabriqué, comme l’examine Brian Hall dans son article.

Le vaste processus de mobilisation communautaire de l’IRAC a révélé ce que plus de 800 architectes, stagiaires et étudiants attendent d’un organisme national d’adhésion : clarté, développement professionnel accessible, plaidoyer visible et communication transparente.

Ensemble, ces contributions tracent une voie plus réceptive, plus pertinente et mieux alignée sur les besoins diversifiés de la profession et sur les priorités urgentes du Canada.

Jonathan Bisson, FIRAC RAIC President, Président de l’IRAC

A little over a year ago, I invited you to think differently in order to shape the future. After a year as President and Chair of the RAIC Board, I would like to share how these ambitions are now taking form in concrete actions, in a context marked by the climate emergency, the housing crisis, the transformation of our built environment, and the ongoing technological revolution. The RAIC’s role is not to solve everything, but to provide direction and to remind decision-makers and the public that architecture remains at the heart of collective well-being.

Implementing a National Vision

From the outset of my mandate, I wanted the RAIC to act as a bridge between provincial realities. More regular meetings between organizations, better structured collaborations, and our participation in collective initiatives focused on the quality of the built environment have strengthened this dialogue and our presence across the country, challenging our respective approaches and enriching them with international perspectives.

Providing Climate Leadership

In 2024, I wrote that addressing ecological challenges was no longer optional. This conviction has since taken form in the RAIC Climate Action Plan, developed by the Steering Committee for the Climate Action Engagement and Enablement Plan. It provides a framework to accelerate the transition to low-carbon, resilient, and regenerative design by embedding climate action into practice, education, and partnerships. The Plan, presented in June alongside the American Institute of Architects, Royal Institute of British Architects, and New Zealand Institute of Architects, situates the Canadian profession within an international

movement that recognizes the structural role of architecture in addressing the climate crisis.

This first year has confirmed for me that a true culture of design must explicitly be brought back to the centre of public conversation. Design is not just a matter of form: it shapes everyday experience, health, dignity, and the sense of belonging to a neighbourhood, a community, a place. The quality of the built environment must become a collective reflex. To champion a culture of design is to affirm design as a public good.

Embracing the Technological Revolution

Since 2023, a significant part of my reflection has focused on artificial intelligence (AI) and what it means for our practice. We belong to a self-regulated profession, enriched by several generations of architects. By combining the experience of some with the curiosity of others, we must facilitate access to AI for all cohorts, anticipate its uses, and retain control over it so that it strengthens, rather than weakens, our professional judgement and the long-term quality of our built environment.

We have also worked to consolidate the RAIC’s role as an advisor to public decisionmakers: the federal government, PSPC, DCC/DND, and CMHC, notably through the Housing Design Catalogue Initiative and Maisons Canada. A public affairs policy and a clearer value proposition are being developed to support this voice and further clarify the RAIC’s role. This presence—along with our participation in media and various housing-related panels—serves a simple purpose: to ensure that the voice of architects is heard, consistently and credibly, when housing, infrastructure, and construction quality are being discussed.

This past year was also marked by more frequent exchanges with colleagues, partners, and leaders from First Nations. These encounters are powerful reminders that architecture in Canada has too often been built on territories rather than with the peoples who have lived there for millennia, and that Truth and Reconciliation must now tangibly influence how we think about land, housing, places of memory, and public spaces.

Thinking differently becomes meaningful only when it leads us to act differently: in the way we work together across the country, integrate the climate emergency, defend a rigorous culture of design, engage with technology, and take Truth and Reconciliation seriously. The initiatives launched since June 2024 are not ends in themselves; they sketch, for the RAIC and for the profession, a more ambitious, more inclusive, more ecologically aware leadership that is fully conscious of the cultural role of architecture in Canadian society.

Il y a un peu plus d’un an, je vous invitais à penser différemment pour façonner l’avenir. Après une année à la présidence du Conseil de l’IRAC, je souhaite partager comment ces ambitions se traduisent désormais en gestes concrets, dans un contexte marqué par l’urgence écologique, la crise du logement, la transformation de notre cadre bâti et la révolution technologique. Le rôle de l’IRAC n’est pas de tout résoudre, mais de donner une direction et de rappeler que l’architecture demeure au cœur du bien-être collectif.

Mettre en œuvre une vision nationale Dès le début de mon mandat, j’ai souhaité que l’IRAC agisse comme un pont entre les réalités provinciales. Des rencontres plus

régulières entre organisations, des collaborations mieux structurées et notre participation à des chantiers collectifs sur la qualité de l’environnement bâti ont renforcé ce dialogue et notre présence à l’échelle du pays, en confrontant nos approches et en les nourrissant de perspectives internationales.

Assumer un leadership face à l’urgence écologique En 2024, j’écrivais que relever les défis écologiques n’était plus une option. Cette conviction s’est incarnée dans le Plan d’action climatique de l’IRAC, élaboré par le Comité directeur sur le Plan d’engagement et d’habilitation en matière d’action climatique : un cadre pour accélérer la transition vers une conception sobre en carbone, résiliente et régénérative, en intégrant l’action climatique à nos pratiques, à la formation et aux partenariats, présenté en juin aux côtés de l’AIA, du RIBA et du NZIA.

usages et en garder le contrôle, afin qu’elle renforce plutôt qu’elle n’affaiblisse notre jugement professionnel et la durabilité de notre cadre bâti.

Accroître la crédibilité publique et politique

Nous avons également travaillé à mieux asseoir la place de l’IRAC comme interlocuteur auprès des décideurs publics : gouvernement fédéral, SPAC/PSPC, DCC/DND et SCHL, notamment à travers la Housing Design Catalogue Initiative et Maisons Canada. Une politique d’affaires publiques et une proposition de valeur plus explicite sont en développement pour appuyer cette voix et clarifier encore le rôle de l’IRAC. Cette présence, tout comme nos interventions dans des médias ou différents panels sur le logement, vise un objectif simple : faire entendre, de manière constante et crédible, la voix des architectes lorsqu’il est question de logement, d’infrastructures et de qualité de construction.

Approfondir notre engagement envers la vérité et la réconciliation

Cette année a aussi été marquée par des échanges plus fréquents avec des collègues, partenaires et leaders issus des Premières Nations. Ces rencontres nous rappellent que l’architecture au Canada s’est trop souvent construite sur des territoires plutôt qu’avec les peuples qui y habitent depuis des millénaires, et que vérité et réconciliation doivent désormais influencer concrètement notre façon de concevoir le territoire, le logement et les espaces publics.

Agir différemment

Faire progresser la culture du design

Cette première année m’a confirmé que la culture du design doit être explicitement remise au centre de la conversation publique. Le design n’est pas qu’une question de forme : il façonne l’expérience quotidienne, la santé, la dignité, et le sentiment d’appartenance à un quartier, une communauté, un territoire. La qualité du cadre bâti doit devenir un réflexe collectif : défendre une culture du design, c’est affirmer le design comme bien public.

S’approprier la révolution technologique Depuis 2023, une part importante de mes réflexions porte sur l’intelligence artificielle et sur ce qu’elle signifie pour notre pratique. Nous exerçons une profession auto-régulée, forte de plusieurs générations d’architectes ; en croisant l’expérience des uns et la curiosité des autres, nous devons faciliter l’accès à l’IA pour toutes les cohortes, anticiper ses

Penser différemment n’a de sens que si cela nous amène à agir différemment : dans notre manière de travailler ensemble à l’échelle du pays, d’intégrer l’urgence écologique, de défendre une culture du design exigeante, d’apprivoiser la technologie et de prendre au sérieux la vérité et la réconciliation. Les chantiers engagés depuis juin 2024 ne sont pas des fins en soi ; ils esquissent, pour l’IRAC et pour la profession, un leadership plus ambitieux, plus inclusif, plus écologique et pleinement conscient du rôle culturel de l’architecture au sein de la société canadienne.

Jonathan Bisson presents to the National Architects Exchange delegation from Germany.

Jonathan Bisson présente devant la délégation allemande du National Architects Exchange.

Charis Village, Lacombe, AB. The precast concrete solution was designed and built in just 8 months.

Charis Village, Lacombe (Alb.). La solution en béton préfabriqué a été conçue et réalisée en seulement huit mois.

Le béton préfabriqué peut contribuer à répondre aux besoins en logement du Canada

Brian J Hall, B.B.A., MBA, FCPCI, MRAIC

Managing Director, Canadian Precast/ Prestressed Concrete Institute; TrusteeRoyal Architectural Institute of Canada Foundation Directeur général, Institut canadien du béton préfabriqué et précontraint; Fiduciaire – Fondation de l’Institut royal d’architecture du Canada

The prefab precast concrete industry has demonstrated resilience despite challenging market conditions, establishing itself as a vital component of Canada’s construction sector.

Prefabricated (prefab) precast construction can help solve Canada’s housing needs by significantly cutting build times, often by 20-50% (McKinsey & Company), which accelerates the supply of new housing units. The components required for a complete residential structure—such as cladding, flooring, elevator shafts, stairs, and structural elements—can be manufactured in a controlled precast factory environment. Prefab methods reduce

waste, enhance quality control, and enable continuous construction regardless of weather, ultimately delivering more housing units faster to meet high demand.

Precast concrete is no longer limited to conventional infrastructure or below-grade construction. Its use has expanded into a wide range of building types, including low- and mid-rise residential developments, hotels, care homes, and other commercial projects. The material is especially effective for developments that leverage repetitive, factoryproduced elements, which promote uniform quality and streamlined production.

One of the core strengths of prefabrication is the ability to repeat components. This repetition enables manufacturers to reuse formwork and automate key steps, reducing waste, accelerating production, lowering costs, and improving overall quality. Although many producers offer standardized systems,

the precast industry still provides considerable design flexibility and numerous opportunities for customization.

Depending on the construction method— whether it’s a total precast system or a hybrid structure—precast engineers work closely with the design team to support the overall design concept. Engaging a precast producer early in the design process, also known as “design assist,” is a collaborative approach that leverages the precaster’s expertise to improve project quality, save time, and reduce costs. Strong partnerships between architects, developers, contractors, and precast concrete suppliers—sustained over multiple projects—are essential to achieving reliable, high-performance, profitable outcomes and avoiding learning curves on a project-by-project basis.

Although prefabricated off-site construction might be seen as a “new” idea in some countries, building components made off-site for

on-site assembly have historically been used because they are efficient, scalable and can significantly reduce construction schedules. However, despite these benefits, prefab and modular building methods have been slowly adopted in North America. A McKinsey & Company study shows that prefabricated modular techniques make up less than 4 percent of the U.S. housing stock and even less in Canada, while in Japan it’s about 15 percent, and in countries like Finland, Norway, and Sweden it’s around 45 percent.

Precast concrete is a highly effective way to introduce modularity into the Canadian construction industry. Its capacity to support year-round production, regardless of weather conditions, makes it especially valuable in Canada’s climate, where seasonal restrictions can delay conventional construction. By manufacturing components in a controlled factory environment, precast systems guarantee consistent quality and minimal delays.

Precast concrete provides a ready-to-scale solution to help address Canada’s housing shortages. A network of established precast companies across Canada stands ready to quickly increase production of high-quality components and sections needed for home building, including fully insulated wall panels, factory-installed windows, and integrated parts that simplify installation and reduce onsite labour.

The benefits of speed, affordability, yearround construction, and the ability to scale up quickly mean precast is a solution that can make a meaningful difference in helping Canada achieve our housing goals.

For more information, check out www.cpci.ca or scan the QR Code below.

L’industrie du béton préfabriqué a fait preuve d’une grande résilience malgré des conditions de marché difficiles, s’imposant comme un élément essentiel du secteur de la construction au Canada.

La construction préfabriquée en béton préfabriqué peut contribuer à répondre aux besoins en logement du Canada en réduisant considérablement les délais de construction — souvent de 20 à 50 % (McKinsey & Company) — ce qui accélère l’offre de nouvelles unités d’habitation. Les composants nécessaires à une structure résidentielle complète — revêtements extérieurs, planchers, cages d’ascenseurs, escaliers et éléments structuraux — peuvent être fabriqués dans un

environnement contrôlé en usine. Les méthodes préfabriquées réduisent le gaspillage, améliorent le contrôle de la qualité et permettent une construction continue, peu importe les conditions météorologiques, ce qui permet ultimement de livrer plus rapidement un plus grand nombre d’unités pour répondre à la forte demande.

L’utilisation d’éléments en béton préfabriqué dans la construction de bâtiments Le béton préfabriqué ne se limite plus aux infrastructures traditionnelles ou aux ouvrages en sous-sol. Son utilisation s’est élargie à une vaste gamme de typologies, notamment les immeubles résidentiels de faible et moyenne hauteur, les hôtels, les centres de soins et d’autres projets commerciaux. Ce matériau est particulièrement efficace pour les projets qui tirent avantage d’éléments répétitifs produits en usine, favorisant une qualité uniforme et une production rationalisée.

L’un des principaux atouts de la préfabrication est la possibilité de répéter les composants. Cette répétition permet aux fabricants de réutiliser le coffrage et d’automatiser certaines étapes clés, réduisant ainsi le gaspillage, accélérant la production, abaissant les coûts et améliorant la qualité globale. Bien que de nombreux fabricants offrent des systèmes standardisés, l’industrie du préfabriqué demeure très flexible et offre de nombreuses possibilités de personnalisation.

Selon la méthode de construction — système entièrement préfabriqué ou structure hybride — les ingénieurs en béton préfabriqué collaborent étroitement avec l’équipe de conception pour appuyer le concept global. L’engagement précoce d’un fabricant de béton préfabriqué dans le processus de conception, connu sous le nom de design-assist, constitue une approche collaborative qui permet de tirer parti de l’expertise du producteur pour améliorer la qualité du projet, gagner du temps et réduire les coûts. Des partenariats solides entre architectes, promoteurs, entrepreneurs et fournisseurs de béton préfabriqué — maintenus sur plusieurs projets — sont essentiels pour obtenir des résultats fiables, performants et rentables, tout en évitant les courbes d’apprentissage répétitives.

Une perspective mondiale

Bien que la construction préfabriquée hors site puisse sembler une « nouvelle » idée dans certains pays, les composants fabriqués en usine puis assemblés sur le chantier sont utilisés depuis longtemps en raison de

leur efficacité, de leur évolutivité et de leur capacité à réduire considérablement les délais de construction. Malgré ces avantages, les méthodes de construction préfabriquée et modulaire ont été adoptées lentement en Amérique du Nord. Une étude de McKinsey & Company indique que les techniques modulaires préfabriquées représentent moins de 4 % du parc résidentiel américain, et encore moins au Canada, tandis qu’au Japon, elles atteignent environ 15 %, et dans des pays comme la Finlande, la Norvège et la Suède, environ 45 %.

La construction préfabriquée en béton au Canada

Le béton préfabriqué constitue un moyen très efficace d’introduire la modularité dans l’industrie canadienne de la construction. Sa capacité à soutenir une production continue, peu importe les conditions climatiques, en fait une solution particulièrement précieuse au Canada, où les restrictions saisonnières peuvent ralentir la construction traditionnelle. En fabriquant les composants dans un environnement contrôlé, les systèmes préfabriqués assurent une qualité constante et minimisent les retards.

Le béton préfabriqué offre une solution évolutive pour contribuer à répondre à la pénurie de logements au pays. Un réseau d’entreprises de béton préfabriqué bien établies partout au Canada est prêt à augmenter rapidement la production de composants et de sections de grande qualité nécessaires à la construction résidentielle, y compris des panneaux muraux entièrement isolés, des fenêtres installées en usine et des éléments intégrés qui simplifient l’installation tout en réduisant la maind’œuvre sur le chantier.

Les avantages associés à la rapidité, à l’accessibilité financière, à la construction en toutes saisons et à la possibilité d’augmenter rapidement la capacité signifient que le béton préfabriqué peut jouer un rôle déterminant pour aider le Canada à atteindre ses objectifs en matière de logement.

Pour en savoir plus, visitez www.cpci.ca ou numérisez le code QR.

Ce que nous avons entendu : Perspectives issues du processus de mobilisation communautaire de l’IRAC 2025

Giovanna Boniface, Chief Commercial Officer, Chef de la direction commerciale, l’IRAC

The question was straightforward: what does the architectural community need from a national organization? The answers, gathered from over 800 voices across Canada, painted a picture both challenging and hopeful—one that points toward a reimagined model of professional membership built on transparency, relevance, and shared purpose.

In 2025, the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada undertook one of its most comprehensive community engagement initiatives in recent years. Through the RAIC Community Survey, four national focus groups, and the RAIC Intern Member Survey, architects, interns, students, educators, allied professionals, and foreign-trained practitioners contributed evidence-informed insights about the state of the profession and their expectations for national membership. Despite the diversity of respondents across career stages, regions, and practice contexts, the findings revealed remarkably consistent priorities.

Clarity of Purpose and Membership Value

The call for transparency echoed across every engagement stream. Respondents want to understand clearly how membership fees translate into tangible benefits. Many emphasized the need for updated models that recognize different practice contexts, income levels, and career stages. Flexibility, affordability, and tiered offerings emerged as essential strategies for making membership accessible and equitable.

Non-members and former members noted that uncertainty about value was a primary barrier to joining or rejoining. This alignment across active and prospective members suggests significant potential for renewed engagement if a clearer value proposition is both communicated and delivered. The message is unambiguous: architects want to see the return on their investment.

Professional development emerged as the most consistently valued element of national membership. Participants emphasized continuing education, on-demand learning, practical tools, and access to high-quality training that reflects contemporary practice realities. Education was identified not only as supporting individual career growth but also as signaling national leadership in shaping professional competence and resilience.

The RAIC Intern Member Survey reinforced these findings with striking clarity. Interns highlighted structural challenges including wage inequities, limited involvement in full project cycles, and unclear pathways to licensure and mentorship. They identified affordable training, ExAC supports, and national coordination of early-career pathways as priorities where the RAIC is uniquely positioned to lead. This alignment between intern-specific insights and broader survey results underscores the importance of designing education and support systems across the entire professional lifecycle— from student to seasoned practitioner.

Advocacy emerged as a powerful theme throughout the engagement process. Respondents consistently emphasized the need for the RAIC to represent architecture with a stronger, more unified national voice. Urgent areas requiring coordinated representation include procurement reform, architectural fees, housing policy, sustainability, climate resilience, and digital transformation.

Participants from all professional categories expressed that visible advocacy outcomes directly increase the perceived value of membership. National leadership is critical for elevating the profession’s status, clarifying architects’ roles in public policy, and addressing the persistent devaluation of architectural expertise. The community wants to see tangible results from advocacy efforts and

clearer communication about the RAIC’s policy influence and impact.

Transparent, accessible, and bilingual communication was identified as foundational to trust and engagement. Respondents noted that even when the RAIC is doing strong work, insufficient visibility limits both impact and member awareness. Clearer reporting on advocacy initiatives, educational investments, partnership programs, and organizational priorities would strengthen connection and confidence.

Participants also emphasized that digital experience matters. Expectations for streamlined, accessible communication are shaped by contemporary online standards, and members want to see these reflected in their interactions with a national professional body. The bar has been raised, and meeting it is essential.

The four focus groups held in October 2025 provided crucial qualitative depth that validated and expanded survey themes. Bringing together individuals representing a crosssection of the profession, these discussions explored mentorship, support for early-career professionals, and the RAIC’s role in fostering community across regions and generations.

Participants emphasized that mentorship should be treated as a core professional pillar, not an add-on. They reinforced the importance of embedding equity, diversity, inclusion, and reconciliation into all programming and advocacy, noting that these commitments must be visible, credible, and sustained. Many highlighted the need for more regionally attuned engagement and stronger connections among practitioners nationwide.

The insights from this comprehensive engagement process illustrate a coherent national vision for architectural membership. The profession’s expectations are clear: transparent and flexible membership models, career-stage-responsive professional development, strong and visible advocacy, accessible bilingual communication, commitment to climate action and equity, and community building that spans regions, disciplines, and generations.

These findings are now informing the next phases of the RAIC Membership Re-invigoration Project, including model development, value proposition refinement, and testing with representative groups. With evidence at

the centre of decision-making, the RAIC is working toward a membership model that reflects practice realities, supports a diverse and evolving profession, and strengthens national leadership in architecture.

The architectural community has offered a clear roadmap. The next step is translating these insights into meaningful action that reinforces the value, relevance, and future impact of national membership in Canadian architecture.

La question était simple : que souhaite la communauté architecturale d’un organisme national? Les réponses, recueillies auprès de plus de 800 voix à travers le Canada, ont révélé un portrait à la fois exigeant et porteur d’espoir — un portrait qui ouvre la voie à un modèle réinventé d’adhésion professionnelle fondé sur la transparence, la pertinence et un objectif commun.

En 2025, l’Institut royal d’architecture du Canada a entrepris l’une de ses initiatives de mobilisation communautaire les plus approfondies des dernières années. Grâce au Sondage communautaire de l’IRAC, à quatre groupes de discussion nationaux et au Sondage 2025 de l’IRAC auprès des membres stagiaires, des architectes, stagiaires, étudiants, enseignants, professionnels associés et personnes formées à l’étranger ont partagé des perspectives éclairées sur l’état de la profession et leurs attentes envers un organisme national d’adhésion. Malgré la diversité des répondants selon les étapes de carrière, les régions et les contextes de pratique, les priorités exprimées se sont révélées remarquablement cohérentes.

Clarté de la mission et valeur de l’adhésion L’appel à la transparence s’est fait entendre dans chacun des volets de mobilisation. Les répondants souhaitent comprendre clairement comment les frais d’adhésion se traduisent en avantages concrets. Plusieurs ont souligné la nécessité de modèles actualisés qui tiennent compte des divers contextes de pratique, niveaux de revenus et étapes de carrière. La flexibilité, l’accessibilité financière et les offres modulées ont émergé comme des stratégies essentielles pour rendre l’adhésion plus équitable.

Les non-membres et anciens membres ont noté que l’incertitude quant à la valeur de l’adhésion constitue un obstacle majeur à l’adhésion ou au retour. Cet alignement entre membres actifs et potentiels indique un fort potentiel de mobilisation renouvelée si une

Key insights from the RAIC’s 2025 community engagement process

Perspectives clés issues du processus de mobilisation communautaire 2025 de l’IRAC

proposition de valeur plus claire est communiquée — et réalisée. Le message est sans équivoque : les architectes souhaitent voir un retour concret sur leur investissement.

Le développement professionnel comme infrastructure essentielle

Le développement professionnel s’est imposé comme l’élément le plus fortement valorisé d’une adhésion nationale. Les participants ont souligné l’importance de la formation continue, de l’apprentissage à la demande, d’outils pratiques et de formations de grande qualité reflétant les réalités contemporaines de la pratique. L’éducation a été identifiée non seulement comme un levier de croissance individuelle, mais aussi comme un marqueur de leadership national en matière de compétence et de résilience professionnelles.

Le Sondage 2025 de l’IRAC auprès des membres stagiaires a renforcé ces conclusions avec une grande clarté. Les stagiaires ont mis en lumière des défis structurels, notamment des inégalités salariales, une participation limitée à l’ensemble du cycle des projets, et des parcours peu clairs vers l’agrément et le mentorat. Ils ont désigné la formation abordable, les soutiens à l’ExAC, et une meilleure coordination nationale des parcours en début de carrière comme des priorités où l’IRAC est particulièrement bien placée pour exercer un leadership. Cette convergence entre les perspectives des stagiaires et celles de l’ensemble de la profession souligne l’importance de concevoir des systèmes de formation et de soutien adaptés à toutes les étapes de la carrière — de l’étudiant au praticien chevronné.

Un appel à un leadership national visible et crédible en matière de défense d’intérêts La défense d’intérêts s’est révélée comme un thème majeur tout au long du processus de

mobilisation. Les répondants ont exprimé un besoin constant que l’IRAC représente la profession avec une voix nationale plus forte et plus unifiée. Les domaines identifiés comme nécessitant une représentation coordonnée incluent la réforme de l’approvisionnement, les honoraires d’architecture, les politiques de logement, la durabilité, la résilience climatique et la transformation numérique.

Les participantes et participants de toutes catégories professionnelles ont indiqué que des résultats tangibles en matière de défense d’intérêts renforcent directement la valeur perçue de l’adhésion. Le leadership national est essentiel pour rehausser le statut de la profession, clarifier le rôle des architectes dans les politiques publiques et s’attaquer à la dévalorisation persistante de l’expertise architecturale. La communauté souhaite voir des résultats concrets des efforts de plaidoyer, accompagnés d’une communication plus claire sur l’influence et l’impact de l’IRAC.

Communication et accessibilité

Une communication transparente, accessible et bilingue a été identifiée comme un fondement essentiel de la confiance et de la mobilisation. Les répondants ont noté que, même lorsque l’IRAC réalise un travail solide, son impact demeure parfois limité par un manque de visibilité. Une meilleure communication sur les initiatives de plaidoyer, les investissements en formation, les partenariats et les priorités organisationnelles renforcerait le lien et la confiance.

Les participants ont également souligné l’importance de l’expérience numérique. Les attentes en matière de communication fluide et accessible sont façonnées par les normes actuelles du milieu numérique — et les membres souhaitent voir ces standards reflé-

tés dans leurs interactions avec un organisme professionnel national. La barre est haute, et il est essentiel de s’y conformer.

Perspectives des groupes de discussion

Les quatre groupes de discussion tenus en octobre 2025 ont offert une profondeur qualitative cruciale, venant valider et enrichir les thèmes des sondages. Rassemblant des personnes représentant un large éventail de la profession, ces échanges ont exploré le mentorat, le soutien aux professionnels en début de carrière et le rôle de l’IRAC dans le renforcement des liens à travers les régions et les générations.

Les participants ont souligné que le mentorat doit être considéré comme un pilier professionnel essentiel, et non comme un ajout facultatif. Ils ont insisté sur l’intégration de l’équité, de la diversité, de l’inclusion et de la réconciliation dans l’ensemble des programmes et initiatives de plaidoyer, tout en soulignant que ces engagements doivent être visibles, crédibles et durables. Plusieurs ont mis en lumière le besoin d’une mobilisation plus sensible aux réalités régionales et de liens plus solides entre les praticiens du pays.

Une vision commune pour l’avenir

Les perspectives issues de ce vaste processus de mobilisation décrivent une vision nationale cohérente de l’adhésion architecturale. Les attentes de la profession sont claires : des modèles d’adhésion transparents et flexibles, un développement professionnel adapté aux étapes de carrière, un plaidoyer fort et visible, une communication bilingue accessible, un engagement envers l’action climatique et l’équité, et un renforcement de la communauté à travers les régions, les disciplines et les générations.

Ces constats orientent maintenant les prochaines étapes du Projet de revitalisation de l’adhésion de l’IRAC, incluant l’élaboration de modèles, le raffinement de la proposition de valeur et des tests auprès de groupes représentatifs. En plaçant les données probantes au cœur de la prise de décision, l’IRAC travaille à concevoir un modèle d’adhésion qui reflète les réalités de la pratique, soutient une profession diversifiée et en évolution, et renforce le leadership national en architecture.

La communauté architecturale a tracé une voie claire. L’étape suivante consiste à transformer ces perspectives en actions concrètes qui renforcent la valeur, la pertinence et l’impact futur d’une adhésion nationale en architecture canadienne.

Participants in a group discussion about architectural fees, at the 2025 RAIC Conference on Architecture

Participants à une discussion de groupe sur les honoraires d’architecture

lors de la Conférence 2025 de l’IRAC sur l’architecture

As part of Nashville’s ongoing efforts to improve its water management infrastructure, the city completed a major upgrade to the Gibson Creek Equalization Facility. This $18.9 million project added a 10-million-gallon concrete tank and a new pump station to help manage excessive sewer flows. The facility is a key component of the city’s Overflow Abatement program, aimed at reducing sewer overflows and improving water quality in local waterways.

A critical part of the facility’s infrastructure upgrade was the installation of 15 BILCO access doors, including several heavy-duty H-20 reinforced doors designed to withstand high traffic and environmental stresses. These corrosion-resistant doors, made of durable stainless-steel, provide secure, long-lasting access to various components such as the valve vaults, wet walls and flow diversion structure.

“You need to have stainless steel when dealing with sewage treatment plants and corrosive materials. They also have gaskets to seal in moisture. From a containment standpoint, that’s the biggest advantage to those doors.”

– Thomas Ward, Reeves Young

• Nashville completed an $18.9 million upgrade to its water management infrastructure, including a new equalization facility and pump station to manage sewer system flow.

• The new system will store peak flows and release them when the sewer system has the capacity to handle them, addressing both population growth and fluctuating water volumes.

• The project involved the installation of 15 BILCO access doors.

• These included H-20 reinforced doors for AASHTO H-20-wheel loading.

Keep up with the latest news from The BILCO Company by following us on Facebook and LinkedIn.

For over 100 years, The BILCO Company has been a building industry pioneer in the design and development of specialty access solutions for commercial and residential construction. For more information, visit www.BILCO.com.

The BILCO Company is now part of Quanex (NYSE: NX), a global, publicly trade manufacturing company serving OEMs in the fenestration, hardware, cabinetry, solar, refrigeration, security, construction, and outdoor products market.

A DEVELOPMENT CENTERED ON AN INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTRE AND SKILLS DEVELOPMENT TRAINING FACILITY SUGGESTS HOW RECONCILIATION CAN TAKE PHYSICAL FORM.

PROJECT Indigenous Hub, Toronto, Ontario

ARCHITECTS BDP Quadrangle, Stantec Architecture, Two Row Architect, ERA Architects

TEXT Elsa Lam

PHOTOS James Brittain unless otherwise noted

The Indigenous Hub is Toronto’s best-sounding block. As you approach from the south, a fringe made of tens of thousands of metal beads, hung from the eaves of the Indigenous Community Health Centre, rustles in the wind, making a sound uncannily like a babbling brook.

It’s one of many details designed to make this complex of community, commercial, and residential buildings an oasis in the city. It was crucial to create a safe, welcoming place of healing for the clientele of the Indigenous Health Centre and for Miziwe Biik, the Indigenous Employment and Training Centre that adjoins it. That spirit also extends to the rest of the block including a rental apartment building to the south, a condominium building to the north, and a restored industrial heritage building.

The project was the dream of Anishnawbe Health Toronto’s longtime executive director Joe Hester, who died on January 1, 2025, at the age of 77. A decade ago, when the Canary District as a whole was opened up for development thanks to the construction of a flood-protecting landform in Corktown Common park, the 2.4-acre property was transferred to the Indigenous community which Hester viewed as a “return.” Hester led a search for a team that could realize the vision of creating a health facility purpose-built for the Indigenous community.

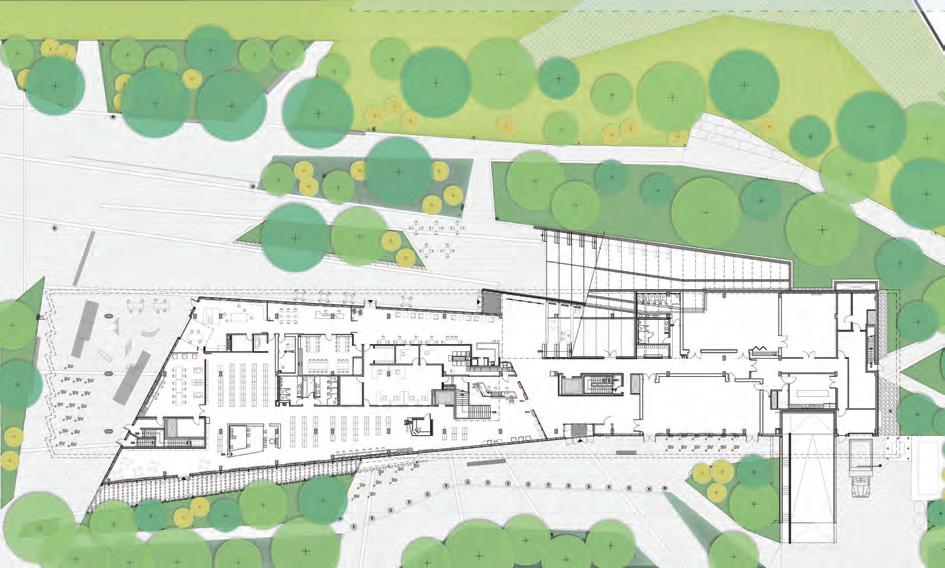

LEFT The Indigenous Hub is a full block of buildings that includes the Indigenous Health Centre (centre left), Miziwe Biik Employment and Training Centre (left of the health centre), restored Canary restaurant (far left), and residential buildings (top centre and right).

“We wanted to bring an architecture to the Toronto landscape that represents us culturally, which then, of course, our community would see as something they could be proud of. The interior spaces had to be able to facilitate our cultural approaches to health and healing because our ceremonies are very important to the healing process,” said Hester.

The initial master plan for the 440,000-square-foot development was developed by Stantec Architecture with Two Row Architect. The master plan was subsequently further developed with the added collaboration of BDP Quadrangle and contributions from Urban Strategies. Stantec Architecture and Two Row designed the Indigenous Health Centre, while BDP Quadrangle and Two Row designed Miziwe Biik and the residential components, and ERA Architects led the restoration of the industrial heritage Canary Building.

“It is an honour to contribute to a new and much-needed layer of Indigenous culture and presence within the urban fabric of the city,” says Michael Moxam, project design principal and design culture practice leader for Stantec.

“Our goal was to create a community of inclusiveness,” says BDP Quadrangle co-founder Les Klein. “Inclusion was a core principle guiding everything from material choices to public space access. This pro-

ject is not just symbolic, it is structural; not a gesture, but a grounded return. It is a space of healing, a platform for community-led growth, and a new urban typology born of Indigenous values.”

At the heart of the project, the Indigenous Health Centre is a curved volume whose façade refers to the fancy shawl and jingle dresses worn by Anishnawbe dancers for healing ceremonies. The aluminum façade is perforated to create large-scale patterns drawn from those textiles, explains Moxam; the silvery finish itself was adapted from car manufacturing to produce a glimmering, changeable appearance in different weather conditions.

In an earlier version of the design, the shawl’s fringe was proposed to have been made of stainless steel mesh. Hester dismissed that proposal: “that’s not a fringe; it’s not going to blow in the wind,” he told the architects. Two Row Architect partner Matthew Hickey developed the detail that was eventually used, which involves 12,000 strings of metal beads oversized versions of the drain chains used for sink stoppers. A single worker installed the chains one by one over the course of several months.

“The shawl, also used traditionally for carrying medicine, wraps around the body, but it opens at the heart,” says Two Row Architect principal Brian Porter. Similarly, the building’s four-storey atrium opens to a central

ABOVE The main floor of the Indigenous Health Centre includes curve-edged pods designed to resemble pebbles in a stream. A steel-cut mural by Anishnawbe artist Christi Belcourt runs alongside the feature stair. OPPOSITE LEFT To the east, the atrium opens to a multi-level courtyard garden. The red feature stair refers to a teaching about “walking the red path”—meaning living a good, healthy life. OPPOSITE RIGHT A series of traditional healers’ rooms were designed and built by artist and carpenter John Bird.

courtyard to the east, aligning with the sunrise a direction of beginnings, renewal and spiritual grounding in Indigenous cosmologies. The multi-layered courtyard includes a waterfall fountain, screened sweat lodge court, bioswales, and medicinal plantings. These outdoor spaces facilitate Indigenous ceremony and teachings, and create connections between ground, sky, and nature.

Creating openness and transparency was crucial to providing a safe, comfortable environment for a client group that has historically faced stigma and even harm from healthcare providers. Surrounding the atrium, rounded pavilions housing traditional and western services allude to stones in a river a nod to the site’s location on the historic Don River delta. A red staircase, the side of which is a stunning steel-cut mural by Anishnawbe artist Christi Belcourt, refers to an Indigenous teaching about “walking the red path” meaning cultivating healing by living a good, clean, healthy life.

Stacked above the entry, a series of traditional healers’ rooms was designed and built by artist and carpenter John Bird to recall healing lodges from different Indigenous traditions. The ventilation systems in these rooms allows for smudging, dimmable lights offer a gentler environment, and there is ample room for healers to meet with families and individuals alike.

The integration of traditional and western medicine is part of the Indigenous Health Centre’s model of providing wrap-around care. Services range from primary health care and a dental clinic, to palliative care, to a mental health program, to assistance for people searching

for housing. A child and youth program includes a range of services, from support for expecting and new mothers, to an Outward Bound program for teenagers, to youth outreach workers who can accompany someone to court or help with a college application.

“Joe [Hester]’s philosophy was to have a one-stop shop we call it our circle of care,” explains Anishnawbe Health Toronto’s executive office manager, Christopher Doucett. “So when people come in, if you’re having mental health issues and your [physical] health is not being addressed, you can’t really fix the mental health. Or if your health is in bad shape, and you have no housing when you’re living on the streets, it’s hard to take care of that. So we’re trying our best to do everything under one roof, to completely care for someone.”

Complementing this work, the adjoining Miziwe Biik offers Indigenous training and education, focused on the construction trades. The five-storey facility includes daylight-filled double-height carpentry shops, metal and wood-frame electrical mock-up structures, and classroom spaces. “The idea was to produce a state-of-the-art facility that would not only provide hands-on training, but also the classroom and health and safety training all of the things that are required to create a well-trained tradesperson,” says BDP Quadrangle’s Les Klein.

The building also includes an Early ON drop-in centre for families, and a daycare that will prioritize Indigenous families, while not being exclusively Indigenous. Both of these spaces are equipped with outdoor playspaces, large stroller parking areas, and open kitchens in the Early ON centre, the kitchen is intended to host training for care -

givers, while their kids are cared for within view. Where possible, the building is designed with natural wood finishes and curves rather than right angles, making the spaces feel comfortable and home-like, rather than institutional.

Double-storey glazing in the workshops allows for generous daylight and views for trainees and encourages passersby to peek in. “It’s really great because we have people coming by our front desk asking, ‘what is it that you do here?’,” says Johnny Gionette, training and apprenticeship coordinator at Miziwe Biik. “That really ties into the larger message of the Indigenous Hub, which is that it should actually inspire the customer,” adds Les Klein. “Why is this building different from other buildings? It’s intended to engender conversation about reconciliation all those elements that we need to talk about, but that rarely have physical form.”

Outside, Miziwe Biik’s textured precast façade, says Two Row’s Matthew Hickey, was designed to reference birch bark; the same precast appears as an accent in other parts of the block. “I’m excited for when it gets a little dirty to really see [the textural effect],” says Hickey. Other precast concrete façades on the block are sandblasted with Indigenous petroglyphs, while a large-scale weathering steel screen cov-

ering ventilation shafts is designed with graphics by Indigenous artist Patrick Hunter. Brick considered a colonial material reminiscent of residential schools is avoided in the two Indigenous facilities. Where brick appears as cladding on the podium levels of the condo and rental buildings, it was reimagined to create a traditional basketweave pattern that makes reference to Indigenous craft.

The lobby of the condo building was conceived by Elastic Architects as a sequence of smaller, more private spaces, rather than a single large open room. “People live differently now they might work from home, they might want to work from the lobby, or just hang out,” says Elastic Architects studio director Laura Abanil, who describes the space as a collective ‘living room’. “We wanted it to be a very tranquil space I hope everyone feels peaceful as soon as they walk in here from the hustle and bustle of the city.”

The entire block and especially the Indigenous Health Centre and Miziwe Biik at its heart is infused with a sense of community and care. “I feel like this was very much built from the ground up, through collaboration with our healers and community,” says Anishnawbe Health Toronto’s Christopher Doucett. “Joe [Hester] always told me that everything here was always through community feedback, and

ABOVE LEFT 12,000 strings of metal beads were hung from the health centre’s awnings, creating a fringe that refers to fancy shawl and jingle dresses used as part of traditional healing ceremonies. ABOVE RIGHT Precast concrete façades on the block are sandblasted with imagery derived from Indigenous petroglyphs. OPPOSITE The multi-level courtyard at the centre of the block is designed to facilitate Indigenous ceremony and teachings. It includes a sweat lodge (centre right), a court based on the cardinal directions (far left), and a gathering plaza based on the 13 moons (far right).

everything we do is for community. He would reference [the Indigenous Health Centre] as our house as the community’s house. He wanted it to be inviting to the neighbourhood.”

Hickey says that “removing the ego from the architecture” was key to centering community in the design. “The architect is servicing the community that they’re working for so who are the architects to say what’s right? When the community says it’s right, then there you go. Which means you’ve got to be small sometimes.”

Ultimately, this is a place that offers lessons and healing that extends beyond Toronto’s Indigenous community to the city at large. “There are so many beautiful metaphors in this building,” says Klein. One of his favourites is the large rocks that came from across Canada,

ANISHNAWBE HEALTH TORONTO INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTRE ARCHITECTS STANTEC ARCHITECTURE WITH TWO ROW ARCHITECT | CLIENT ANISHNAWBE HEALTH TORONTO ARCHITECT TEAM STANTEC ARCHITECTURE—MICHAEL MOXAM (FRAIC), SUZANNE CRYSDALE (MRAIC), KHALED ABDELAZIZ, NORMA ANGEL (MRAIC), TINO AUGURUSA, DORA BATISTA, VLAD BORTNOWSKI, GREG BOURIS, DEANNA BROWN (FRAIC), MELISSA CAO, EDA DEMIREL, SOLMAZ ESHRAGHI, VALYA FOX, TANIA GENOVESE, RICH HLAVA, NISSAN IKHLASSI, RONALDO JARING, ANDREA JOHNSON, TAMMIE LEE, LYDIA LOVETTE-DIETRICH, DEAN MACAPAGAL, MAHSHID MATIN, STEVE MOORE, SARAH O’CONNOR-HASSAN, MAT PERICH, IVA RADIKOVA, ANITA SHRESTHA, MARSHA SPENCER, JOHN STEVEN (FRAIC), DANIEL THOMAS, PETER VALENTE, DATHE WONG (MRAIC). TWO ROW ARCHITECT—MATTHEW HICKEY (FRAIC), BRIAN PORTER (FRAIC), ERIK SKOURIS LANDSCAPE , MECHANICAL , ELECTRICAL , STRUCTURAL , CIVIL , SUSTAINABILITY STANTEC CONSULTING LTD. | INTERIORS STANTEC ARCHITECTURE LTD. | PLANNING URBAN STRATEGIES CONTRACTOR HARRBRIDGE AND CROSS AREA 4,180 M2 | BUDGET $34 M COMPLETION APRIL 2025

ENERGY USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 177.7 EKWH/M2/YEAR

and serve as seating in the public plaza. “It expresses not only the way rocks were pushed by the glaciers, but also how Indigenous people were pushed across the landscape against their will, and sometimes where they landed was where they lived.”

“Everyone who walks past here, if they’ve never seen the building, they just stare at everything,” says Anishnawbe Health Toronto’s Christopher Doucett. “Especially the fringe. If it’s a really windy day, you can hear it. You can almost see it dancing in the wind.”

CONDOMINIUM AND RENTAL BUILDINGS, MIZIWE BIIK, CANARY RESTAURANT RESTORATION ARCHITECTS (RESIDENTIAL AND MIZIWE BIIK) BDP QUADRANGLE, TWO ROW ARCHITECT | ARCHITECT (CANARY RESTAURANT) ERA ARCHITECTS | CLIENT (RESIDENTIAL AND CANARY RESTAURANT) DREAM UNLIMITED, THE KILMER GROUP, TRICON RESIDENTIAL | CLIENT (MIZIWE BIIK) ANISHNAWBE HEALTH TORONTO | ARCHITECT TEAM BDP QUADRANGLE—LES KLEIN (FRAIC), KEN BROOKS, AMIR TABATABAEI; TWO ROW ARCHITECT—MATTHEW HICKEY; ERA ARCHITECTS—JORDAN MOLNAR | STRUCTURAL JABLONSKY, AST & PARTNERS MECHANICAL/ELECTRICAL M.V. SHORE ASSOCIATES LTD. LANDSCAPE STANTEC CONSULTING LTD. | INTERIORS BDP QUADRANGLE, ELASTIC ARCHITECTS | CONSTRUCTION MANAGER ELLIS DON | AREA 40,877 M2 (RESIDENTIAL BUILDINGS); 2,530 M2 (MIZIWE BIIK); 2,230 M2 (CANARY RESTAURANT) | BUDGET $104.5 M | COMPLETION APRIL 2025

ENERGY USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 200 KWH/M2/YEAR | WATER USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 1.44 M 3/M2/YEAR

NEW CITY HALL AND LIBRARY COMPLEX

TO BECOME

PROJECT Pôle municipal de Vaudreuil-Dorion, Vaudreuil-Dorion, Quebec

ARCHITECTS Lapointe Magne et associés and L’ŒUF Architectes

TEXT Odile Hénault

PHOTOS David Boyer, unless otherwise noted

In June 2025, a new building was inaugurated in Vaudreuil-Dorion, a rapidly growing municipality just west of Montreal. Home to a city hall and a public library, this recent addition to a traditional suburban landscape is more than the sum of its parts. It represents an attempt to create a vibrant city centre in an area where there was none before.