Bridging the Ville-Marie Expressway, a plaza by Lemay + Angela Silver + AtkinsRealis centres women in Montreal’s history—and in the present-day city.

TEXT Claire Lubell

Simon Fraser University’s art museum, by Hariri Pontarini Architects with Iredale Architecture, is designed to encourage frequent encounters with art.

TEXT Adele Weder

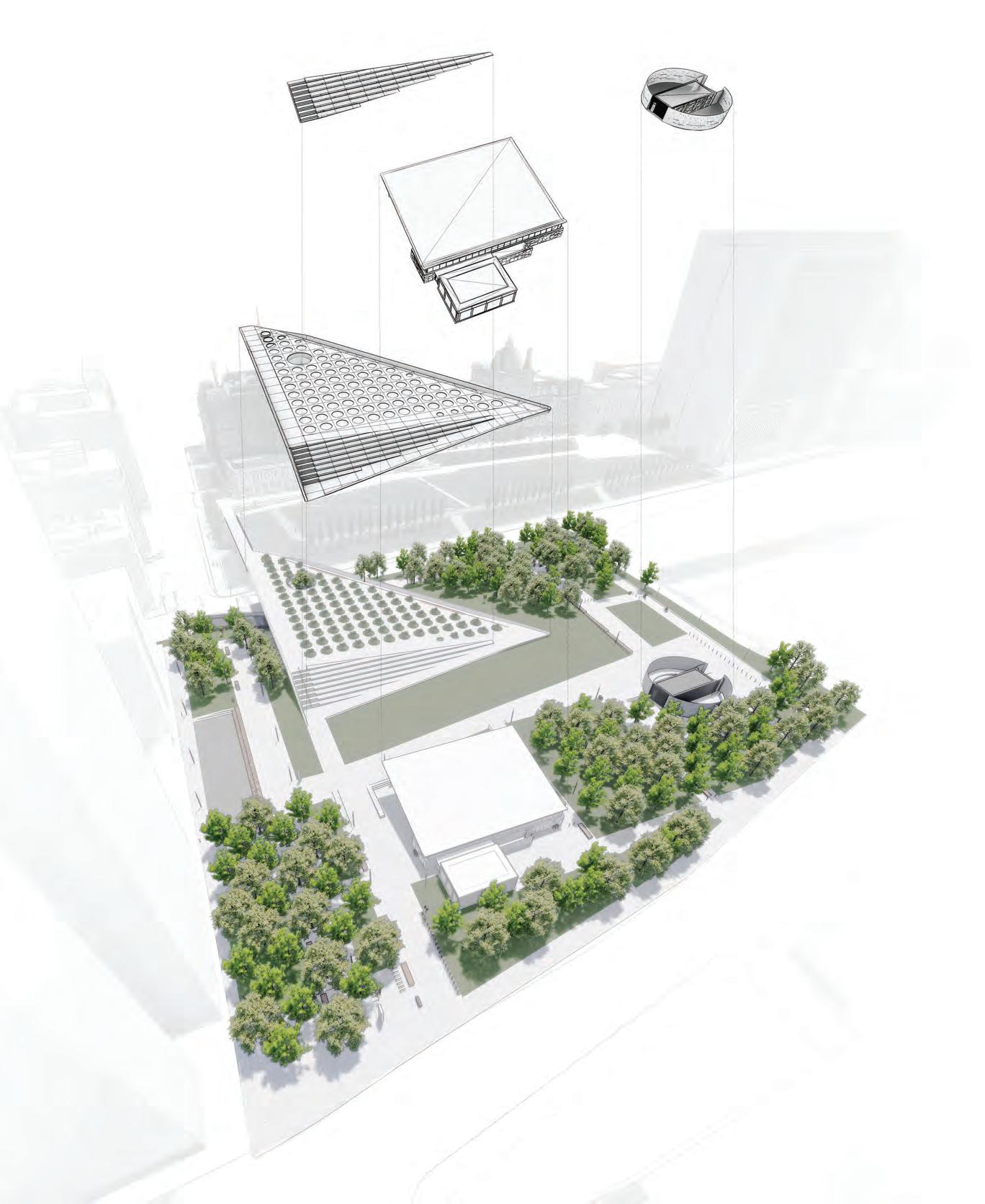

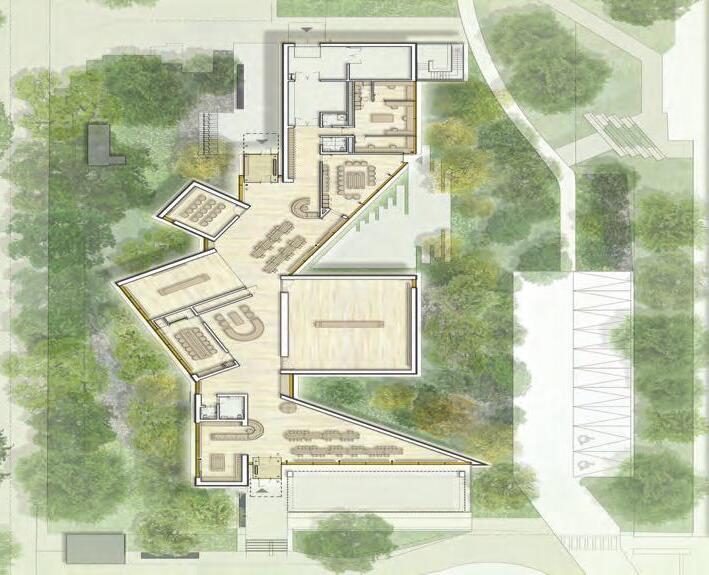

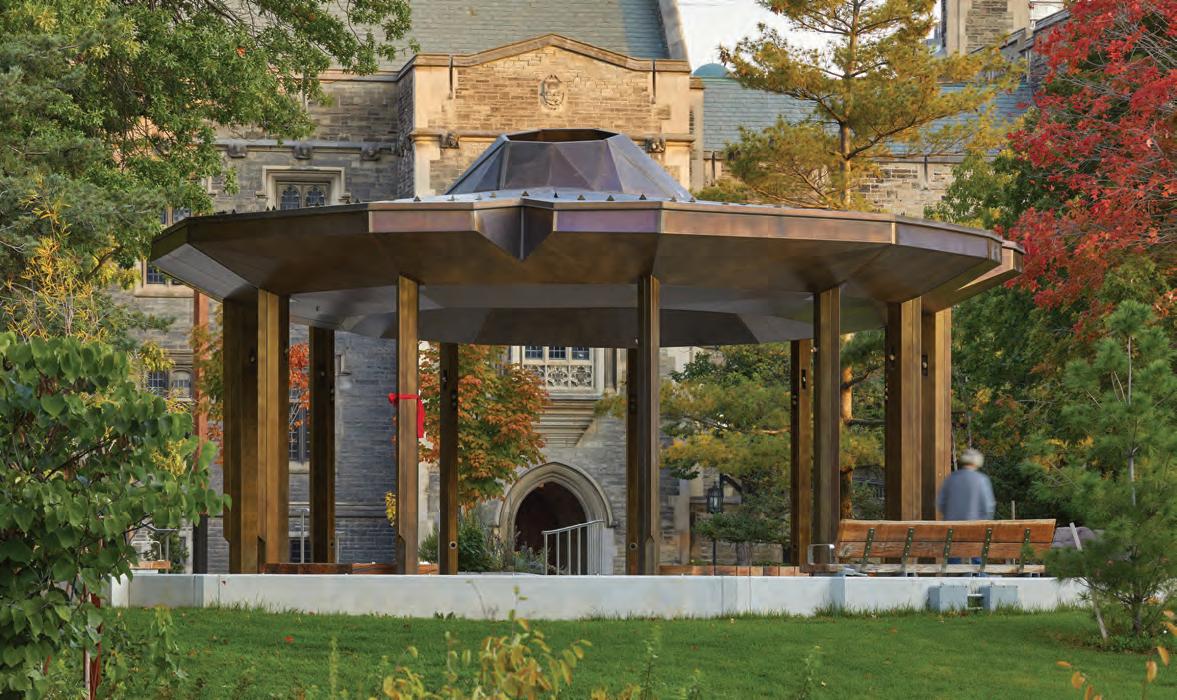

The University of Toronto’s central green is remade with a landscape by KPMB Architects with MVVA and an Indigenous space by Brook McIlroy Architects.

TEXT Pamela Young

Editor Elsa Lam considers projects at the intersection of landscape and architecture.

Vancouver Art Gallery selects designers; shortlist announced for Banff Avenue redevelopment; remembering Dr. Kongjian Yu (1963-2025), Paul Stevens (19632025), and Alex Temporale (1946-2025).

Intern architect survey results; inclusive design; reclaiming the value of architecture.

A Lake Story sends a flotilla of flag-bearing canoes through Toronto’s inner harbour.

Marc Treib reflects on Bill Pechet and Daly Landscape Architecture’s Little Spirits memorial garden.

A playful book by Leslie Van Duzer surveys Bill Pechet’s interdisciplinary work.

An architectural installation by Witthöft & LaTourelle aims to enact reconciliation through art.

COVER Place des Montréalaises, Montreal, Quebec, by Lemay + Angela Silver + AtkinsRealis. Photo by Vincent Brillant

At first blush, there’s a clear distinction between the scope of work of architects and landscape architects. But that doesn’t always hold true. This month’s issue looks at a series of projects where the work of architecture and landscape architecture are tightly intertwined and interwoven.

For our cover story, Claire Lubell visits Place des Montréalaises, a plaza led by architecture firm Lemay, artist Angela Silver, and engineers AtkinsRealis. Structured around a giant inclined plane that bridges the Ville-Marie Expressway, it’s a hefty piece of infrastructure and a rich meadowlike landscape. Narrative, too, is imbued throughout the project, whose name and design honours some two dozen women who were key to the city’s history.

Travelling to the West Coast, we take a look at Simon Fraser University’s Gibson Art Museum, designed by Hariri Pontarini Architects with Iredale Architecture. It’s nestled at the edge of the campus famously designed by Arthur Erickson as an architectural response to its site atop Burnaby Mountain. The Gibson, too, sits in tight relationship to its landscape: its entry canopy stretches out in an echo of Erickson’s horizontal forms, and its low-slung volume blends among the trees. More importantly, the Gibson centers the idea of a promenade more common in gardens than buildings encouraging students to short-cut along its main spine, while enticing them with study areas and art exhibitions en route.

The revamp of the University of Toronto’s central green is another instance of architecture and landscape design working in tight coordination. The Landmark Project by KPMB Architects and Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA) removed the traffic circle that long dominated the front campus. After sinking the parking underground, they topped it with a pedestrian-priority lawn and necklace of gardens. Within the Landmark Project, Brook McIlroy Architects’ Ziibiing landscape, with its bronze Knowledge House pavilion, offers an Indigenous space for ceremony, education and contemplation.

On a larger scale, MVVA also recently completed Toronto’s Biidaasige, a 50-acre

park on Toronto’s waterfront. The park is part of a masterplan by MVVA that builds a new, naturalized mouth for the Don River, and protects 174 hectares of land in the Port Lands and eastern waterfront from flooding, unlocking space for future mixed-use neighbourhoods. While Biidaasige’s parkland and playgrounds were officially inaugurated this summer, its waterways enjoyed a kind of second inauguration this fall. Photographer Amanda Large captured the event: a performance by artist Melissa McGill, featuring a flotilla of 120 canoes with hand-dyed flags, travelling from Biidaasige to the city’s harbour.

Architecture-trained Bill Pechet, who also trained in geography and visual arts, is the subject of two pieces in this month’s pages. Leslie Van Duzer’s recent monograph on Pechet’s wide-spanning work from houses and commercial interiors to playgrounds, plazas, and urban lighting is reviewed. And Marc Treib takes us on a visit to one of Pechet’s most striking projects, Little Spirits Garden, a memorial ground for infants near Victoria, B.C. Composed of concrete retaining bars topped with house-like forms that invite personalization by families, it combines primary elements from both landscape and architecture, to poignant effect.

At Winnipeg’s Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, Witthöft & LaTourelle’s Betonwaves installation uses rubble to tell a powerful story of reconciliation. Using demolition waste from the Hudson’s Bay Company Building across the street, the artists created new bricks, arrayed in irregular walls. Painted in shades of blue, the sculptures evoke sky rather than earth, and ruins rather than monuments: this turns the narrative of the colonial building on its head.

Finally, we pay tribute to Dr. Kongjian Yu, founder of Chinese landscape firm Turenscape, who died in a plane crash in Brazil. Yu pioneered the Sponge Cities concept for water resilience in urban environments, which became Chinese national policy in 2013, and has taken hold in cities and countries around the world.

EDITOR

ELSA LAM, FRAIC, HON. OAA

ART DIRECTOR

ROY GAIOT

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

ANNMARIE ADAMS, FRAIC

ODILE HÉNAULT

LISA LANDRUM, MAA, AIA, FRAIC

DOUGLAS MACLEOD, NCARB FRAIC

ADELE WEDER, FRAIC

ONLINE EDITOR

LUCY MAZZUCCO

SUSTAINABILITY ADVISOR

ANNE LISSETT, ARCHITECT AIBC, LEED BD+C

VICE PRESIDENT & SENIOR PUBLISHER

STEVE WILSON 416-441-2085 x3

SWILSON@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

FARIA AHMED 416 441-2085 x5

FAHMED@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

CIRCULATION CIRCULATION@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

PRESIDENT & EXECUTIVE PUBLISHER ALEX PAPANOU

HEAD OFFICE

For your commercial projects, Gentek is here to lend a hand. In fact, we’ve got all hands on deck. By bringing leading suppliers together in one place, Gentek delivers advanced interior and exterior solutions, service, and support. Your building needs are covered.Your customers are satisfied. And your reputation is built strong.

One distribution source for commercial building solutions.

Ready to experience the transformational impact of Gentek’s committed representatives and extensive product portfolio? Go to www.gentek.ca/professionals/architects/ to explore the unparalleled difference.

The Vancouver Art Gallery has named Formline Architecture + Urbanism and KPMB Architects as the architectural team to lead the next phase of design for its new purpose-built home at Larwill Park, located at 181 West Georgia Street. Selected from proposals submitted by 14 leading Canadian firms, this award marks an important milestone in the Gallery’s renewed vision to create a destination for art and culture that reflects the diversity of its audiences.

“This is the beginning of a collaborative process toward a new conceptual design in 2026 one shaped by listening, dialogue and the perspectives of the communities the gallery serves,” writes the Vancouver Art Gallery in a press statement.

“The selection of Formline + KPMB to envision the new gallery is a bold and topical statement supporting Canadian innovation and excellence,” says Jon Stovell, Chair of the Gallery Association Board. “KPMB Architects brings a proven track record for creating elegant, world-class museums that centre art and community, while B.C.–based Formline Architecture + Urbanism leads with an Indigenous design vision that is both contemporary and deeply rooted in tradition.”

“Our team is deeply honoured to receive the commission to design the new Vancouver Art Gallery, as it brings my personal journey full circle in a profound way,” says Alfred Waugh, founder and principal of Formline Architecture + Urbanism. “My mother left this world too early, and during my formative years, she asked me to do something meaningful for our people a request that has sparked my journey into architecture. Now we have been privileged with this opportunity to celebrate Vancouver’s vibrant

culture while honouring the Indigenous peoples who have stewarded this land for generations and paying tribute to the beautiful mountains and lush rainforests that define our region.”

“It’s an honour to collaborate with Alfred Waugh and Formline to help shape the future of an institution that holds such profound cultural and civic significance for Vancouver and British Columbia places that express a diversity of world views all at once,” says Bruce Kuwabara, a founding partner at KPMB Architects. “Following their release from an internment camp in British Columbia, my family relocated to Hamilton where I was born. Returning to the province to design the Vancouver Art Gallery is deeply meaningful for me.”

www.vanartgallery.bc.ca

Winnipeg-based firm LM Architectural Group | Environmental Space Planning (LM-ESP), in collaboration with DIALOG, were recently selected through a competitive process to design CancerCare Manitoba’s new second building development, representing a historic investment into the future of cancer care in the province.

The new CancerCare Manitoba facility will focus on supporting cutting-edge cancer care research and treatment and creating a provincial hub to help combat the impacts of cancer in Manitoba and beyond. It plans for expanding specialized departments and industry-leading professionals to empower seamless collaboration and innovation and providing advanced technology and equipment to help improve patient outcomes for the future. The facility’s planning is further anchored in creating a modern, hope-inspired destination that prioritizes people-centered design for optimal oncology care, enhanced staff well-being and workflows, and increased support for patients and their families as they move through the continuum of cancer care.

This major development will be located adjacent to the existing CancerCare Manitoba facility that forms part of the greater Bannatyne Campus in Winnipeg the largest healthcare facility in the province.

Currently the project is in pre-design. The design team will pursue extensive user group and stakeholder engagement to help maximize the impact of this multi-generational healthcare development in the centre of Canada. cancercare.mb.ca

The Experiential Design Authority (TEDA) recently announced this year’s winners of its World Expolympics competition, which recognizes exceptional examples of experiential design at Expo 2025 in Osaka, Japan.

The Canada Pavilion was honoured in two major categories: it received the Gold Award for Best Tech Integration, recognizing a unique virtual experience, both for its innovation and for the significant impact of its integration on the overall visitor experience, and the Silver Award in the Best Large Pavilion category, based on the criteria of concept/design, creativity/innovation, engagement/immersion, execution/fabrication, and overall impact.

The Canada Pavilion was inspired by dramatic Canadian ice formations and represents a blend of nature’s power and Canada’s warmth and openness. The pavilion was initially designed through a competition won by Rayside Labossière (Canada), Guillaume Pelletier (Canada) and So&Co (Japan).

The inside of the pavilion is an immersive experience, powered by augmented reality, that allows visitors to discover Canada in what the designers describe as a “fresh and engaging way through a poetic, reflective journey.” www.expo2025.or.jp

The Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC), in partnership with Parks Canada, has announced the six multidisciplinary teams selected to advance to Phase II of the 200-Block Banff Avenue Redevelopment Project design competition.

The six teams advancing to the design competition are Alison Brooks Architects, EVOQ + Ryder, Kengo Kuma & Associates + Paul Raff Studio, KPMB Architects, Revery Architecture, and Stantec Architecture.

200-Block is a set of 10 contiguous lots that includes Banff Avenue Park, the current visitor information centre and its associated parking, and two other buildings. The long-held vision for the 10 lots is that they would be revitalized to contain purpose-built spaces and facilities to support visitor reception, enjoyment and connection with the rest of the park, and foster understanding of the challenges faced by protected areas like Banff National Park.

The design competition winner will be announced in spring 2026. www.letstalkmountainparks.ca

Dr. Kongjian Yu, founder and principal designer of Chinese landscape firm Turenscape, has died in a plane crash in Brazil. Brazilian authorities have confirmed that the aircraft in which he travelled crashed in a rural region close to Aquidauana, resulting in the deaths of Dr. Yu and three others, including the pilot and two filmmakers.

“It is with profound sadness that we announce the passing of Professor Kongjian Yu the founding Dean of the College of Architecture and Landscape at Peking University, Boya Distinguished professor, editor-in-chief of Landscape Architecture Frontiers journal, and an internationally acclaimed landscape architect and educator,” reads a post by the firm he founded, Turenscape. “Professor Yu tragically passed away in a plane crash at the age of 62 on September 23, 2025, while conducting ecological research in the Pantanal region of Brazil.”

25_010736_Canadian_Architect_NOV_CN Mod: September 15, 2025 11:24 AM Print: 10/03/25 2:01:52 PM page 1 v7

We provide quality shipping, packaging and industrial supplies to businesses across North America. From tape and tags to boxes and bubble, everything’s in stock. Order by 6 PM for same day shipping. Best service and selection – experience the difference. Please call 1-800-295-5510 or visit uline.ca

ABOVE Chinese landscape architect Dr. Kongjian Yu, founder of Turenscape and conceiver of the “sponge cities” concept, passed away in a plane crash in Brazil.

Dr. Yu was the 2025 recipient of the RAIC International Prize, awarded to Turenscape in recognition of its contributions to landscape architecture, ecological urbanism, and climate-resilient design. “We were saddened to hear of the tragic passing of Dr. Kongjian Yu. His vision of working with nature to shape resilient, livable cities has left a lasting impact on the global design community. His loss is deeply felt, and our thoughts are with his family, friends, and colleagues,” said Jason Robbins, RAIC immediate past president and co-chair of the RAIC International Prize Selection Committee.

Dr. Yu was also the winner of the 2023 Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize, a biennial $100,000 prize supported by The Cultural Landscape Foundation. “His legacy is secure and his impact continues to grow and expand,” writes The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s Nord Wennerstrom. “The [sponge cities] idea that Yu first nurtured while getting his doctorate at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (1992-95) remarkably became Chinese national policy in 2013. Imagine... a single landscape architect fundamentally restructured the urban planning policy of a global superpower. And the ‘sponge cities’ concept has taken hold in cities and countries around the world.”

In a tribute post on Harvard University Graduate School of Design’s website, Charles Waldheim wrote, “As we mourn our collective loss, we should remember that we have benefitted from Yu’s exemplary life and works. His boundless enthusiasm and relentless optimism remain with us. Despite our grief he would encourage us all, with his characteristic good humor and enthusiasm for our collective project, to persist in this important work in his wake.”

www.turenscape.com

ZAS Architects + Interiors founder Paul Andrew Stevens has passed away at his beloved farm in Prince Edward County.

Paul studied architecture at the University of Toronto and graduated in 1987. Within less than seven years of practice, he became co-owner of a new firm, ZAS Architects + Interiors.

As Senior Principal of ZAS, Paul led the design of institutional buildings, civic structures, offices, arenas, condominiums, and public spaces across Canada, and globally from Shanghai to Dubai. Projects include the Billy Bishop Airport Tunnel, Canoe Landing Community Campus + Schools,

River City Condominiums in Toronto (with Saucier+Perrotte architectes),

CFB Borden’s Curtiss + Vickers dining facilities (with FABRIQ Architecture), Vaughan Civic Centre Library, York University’s Bergeron Centre for Engineering Excellence, and the Stockey Centre for the Performing Arts.

Paul’s final project before his passing, the recently opened University of Toronto Scarborough Campus Sam Ibrahim Building (with CEBRA), marked a full circle moment for Paul as a U of T alumnus.

“Paul’s generosity of spirit defined his transformational leadership style that guided his ZAS family in fulfilling a vision of design excellence, exemplary collaborations, and industry-leading community engagement,” writes ZAS Architects.

www.zasa.com

Heritage conservation architect Alexander (Alex) Temporale, founder of ATA Architects, passed away on September 18, 2025.

Alex graduated from the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Architecture, co-founded Stark Temporale Architects in 1974, and later founded ATA Architects.

Alex had a passion for heritage conservation and was a trusted voice in the field. His work was instrumental in the creation of Ontario’s first Heritage Conservation District in Meadowvale Village and in the rehabilitation of landmarks such as the Bell Gairdner Estate (now the Harding Waterfront Estate), and the Historic Bank of Montreal (now an Anthropologie store) in Oakville. Alex’s work was recognized with the Lieutenant Governor’s Ontario Heritage Trust Award for Excellence in Conservation, the Heritage Canada Foundation Cornerstone Award, and distinctions from the Town of Oakville and the City of Mississauga.

Beyond his professional achievements, Alex volunteered with organizations including the Ontario Historical Society, Heritage Canada, Mississauga Heritage Foundation, and the Ontario Association of Architects’ Perspectives (now Right Angle) journal.

www.raic.org

Governor General’s Medals in Architecture

The Royal Architectural Institute of Canada and the Canada Council for the Arts have opened submissions for the Governor General’s Medals in Architecture. Eligible projects can be built anywhere in the world, and must have been completed within the past seven years. The deadline for submissions is December 11, 2025.

www.raic.org

The Royal Architectural Institute of Canada is accepting submissions for the 2026 RAIC Gold Medal, the Architectural Practice Award, the Emerging Architectural Practice Award, the RAIC Advocate for Architecture Award, the RAIC Architectural Journalism and Media Award, the RAIC Research & Innovation in Architecture Award, and the Prix du XXe Siècle. The deadline is January 9, 2026.

www.raic.org

For the latest news, visit www.canadianarchitect.com/news and sign up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.canadianarchitect.com/subscribe

Renew Your RAIC Membership Today

Lock in your 2026 benefits and get a chance to win! The earlier you renew, the more chances you have to win in our tiered prize draw. Join or renew today at raic.org/why-join

Renouvelez votre adhésion à l’IRAC dès aujourd’hui

Renouvelez dès aujourd’hui pour profiter de vos avantages 2026 et courir la chance de gagner ! Plus vous renouvelez tôt, plus vous augmentez vos chances de gagner dans notre tirage progressif. Adhérez ou renouvelez dès aujourd’hui à raic.org/fr/ raic/pourquoi-adherer.

RAIC Honours & Awards Calls for Submission

It’s awards season! The 2026 Governor General’s Medals in Architecture competition (closing December 11, 2025) and the 2026 RAIC Annual Awards (closing January 9, 2026) are inviting submissions. For more information, visit raic.org.

Distinctions et prix de l’IRAC—

Appels à candidatures

C’est la saison des prix! C’est la saison des prix! Le concours des Médailles du Gouverneur général en architecture 2026 (date limite : 11 décembre 2025) et les Prix annuels 2026 de l’IRAC (date limite : 9 janvier 2026) sont maintenant ouverts aux soumissions. Pour plus d’information, visitez raic.org.

Save the Date—2026 RAIC Conference on Architecture

Mark your calendars for the 2026 RAIC Conference on Architecture, taking place in Vancouver, BC between May 5-8. Registration will open in early February. Keep an eye out for updates at conference.raic.org.

Réservez la date— La Conférence d’architecture 2026 de l’IRAC

Notez à votre agenda : la Conférence d’architecture 2026 de l’IRAC lieu à Vancouver (C.-B.) du 5 au 8 mai.

L’inscription ouvrira au début de février. Restez à l’affût des mises à jour sur conference.raic.org/fr/.

Renew your 2026 RAIC membership to retain access to your benefits.

Renouvelez votre adhésion à l’IRAC pour 2026 afin de conserver vos avantages.

This issue explores the multifaceted challenges and opportunities shaping contemporary architectural practice. Our intern survey reveals the aspirations and concerns of emerging professionals navigating licensure while envisioning a more equitable profession. The Fees and Procurement Working Group’s conference insights demonstrate the urgent need to reclaim architecture’s value in society, moving beyond outdated perceptions to establish architects as essential contributors to community well-being.

Our climate action coverage highlights the RAIC’s successful national Whole Building Life Cycle Assessment training initiative, which equipped over 1,100 professionals with critical tools for decarbonizing the built environment. Finally, we examine the idea of “inclusivity” in public spaces, beyond the concept of accessibility, by drawing inspiration from global examples.

Together, these articles underscore architecture’s responsibility to address systemic challenges while building a more sustainable, equitable, and digitally-responsive future for Canadian communities.

Ce numéro explore les multiples défis et occasions qui façonnent la pratique architecturale contemporaine. Notre sondage auprès des stagiaires met en lumière les aspirations et préoccupations des professionnel·le·s émergent·e·s qui naviguent le processus d’obtention du permis tout en imaginant une profession plus équitable. Les réflexions du Groupe de travail sur les honoraires et l’approvisionnement, présentées lors de la conférence, démontrent l’urgence de redonner sa pleine valeur à l’architecture dans la société, en dépassant les perceptions désuètes pour positionner les architectes comme des acteurs essentiels du bien-être collectif.

Notre couverture de l’action climatique met en évidence la réussite de l’initiative nationale de formation sur l’analyse du cycle de vie complet des bâtiments, menée par l’IRAC, qui a doté plus de 1 100 professionnel·le·s d’outils essentiels pour la décarbonisation de l’environnement bâti. Enfin, nous examinons la notion d’« inclusivité » dans les espaces publics — au-delà de l’accessibilité — en nous inspirant d’exemples à l’échelle mondiale.

L’IRAC est le principal porte-parole en faveur de l’excellence du cadre bâti au Canada. Il démontre comment la conception améliore la qualité de vie tout en tenant compte d’importants enjeux sociétaux par la voie d’une architecture responsable. www.raic.org/fr

Ensemble, ces articles rappellent la responsabilité de l’architecture de s’attaquer aux défis systémiques tout en bâtissant un avenir plus durable, équitable et sensible au numérique pour les collectivités canadiennes.

Fiona Hamilton, MRAIC, Director Representing Interns and Intern Architects, MRAIC, directrice représentant les stagiaires et les architectes stagiaires

Giovanna Boniface, Chief Commercial Officer, Chef de la direction commerciale

In spring 2025, the RAIC invited architectural interns from across Canada to share their experiences, challenges, and ideas for the future of the profession. The responses offer valuable insight into the realities of internship today and evolving expectations of those preparing to become architects. This summary distills key themes and highlights opportunities to support interns navigating the Internship in Architecture Program (IAP) and their journey to licensure.

Top concerns for interns today

Intern architects identified several ongoing challenges impacting their path to licensure and professional growth. Compensation is a commonly raised concern, with many noting salaries don’t reflect education levels or responsibilities. Unpaid overtime and job uncertainty are also mentioned, particularly given architectural practice’s unique demands.

Another challenge relates to completing required internship hours, particularly in site visits and construction administration.

Some interns struggle to access these experiences due to firm size, project type, or logistical constraints. Interns want more opportunities to participate in full project lifecycles.

The licensure process, especially the Examination for Architects in Canada (ExAC), presents another barrier. Interns cite structure, timing, and cost as stress sources, with internationally trained professionals facing additional complexity. Finally, mentorship access remains a key concern. While many have supportive supervision, others struggle to identify mentors or navigate IAP expectations.

Future challenges facing the profession Interns are thinking critically about the profession’s long-term future. Many foresee growing pressure from workforce challenges, including talent shortages, limited pathways for graduates, and attrition due to compensation, work-life balance, and sustainability concerns.

Technological change is another central concern. Participants anticipate significant impacts from artificial intelligence, automation, and evolving design tools, considering how architects can adapt while preserving human creativity. Rising software costs present challenges for small firms and independent practitioners.

Environmental and social responsibility emerged as strong themes. Many interns want more integration of climate change and sustainable design into practice. Others expressed concern about the disconnect between architectural ideals and real-world constraints, particularly regarding affordability and development priorities.

Finally, interns emphasized clearly communicating architectural services’ value. As expectations rise and practice scope becomes more complex, the profession must evolve to remain relevant and impactful.

What interns need most Interns are asking for resources, community, clarity—and to be heard. Interns seek accessible, practical support to navigate licensure: low-cost training, digital tools for logging IAP hours, and online courses aligned with IAP competencies. There’s strong demand for ExAC preparation resources and clearer licensure guidance.

Beyond technical support, interns want mentorship, mental health resources, and guidance on equity and workplace expectations. They’re calling for advocacy around fair compensation, transparent hiring, and inclusive development.

Most respondents want a national intern community to connect with peers, access mentorship, and share resources. They envision a platform fostering support and collective voice, especially for those in smaller firms, rural areas, or equity-seeking groups. Virtual meetups, peer learning groups, and advisory roles could help interns feel supported and engaged.

Interns highlighted gaps in communication across the profession. Many expressed uncertainty about responsibilities of regulators, employers, and organizations. There’s desire for consistent messaging across provinces and national tools—onboarding guides, webinars, centralized platforms—to clarify expectations and support mobility.

The message from interns is clear: they’re ready to contribute but need more support. They’re calling for fairness, clarity, connection, and practical resources reflecting today’s architectural landscape.

Guests at the Emerging Profes-

Invités à la rencontre réseautage des professionnels émergents lors du Congrès 2025 de l’IRAC.

As a national, voluntary, non-regulatory association, the RAIC is uniquely positioned to convene stakeholders, champion intern voices, and curate tools bridging gaps across regions, firms, and career stages. By supporting this emerging generation, the profession can build a stronger, more inclusive, and future-ready foundation for Canadian architecture.

Au printemps 2025, l’IRAC a invité des stagiaires en architecture de partout au Canada à partager leurs expériences, leurs défis et leurs idées pour l’avenir de la profession. Les réponses reçues offrent un aperçu précieux des réalités actuelles du stage et des attentes en évolution de celles et ceux qui se préparent à devenir architectes. Ce résumé présente les principaux thèmes soulevés et met en lumière les occasions de mieux soutenir les stagiaires qui naviguent dans le Programme de stage en architecture (PSA) et leur parcours vers l’obtention du titre.

Principales préoccupations des stagiaires aujourd’hui

Les stagiaires en architecture ont identifié plusieurs défis persistants qui influencent leur cheminement vers l’obtention du titre et leur développement professionnel. La rémunération constitue une préoccupation fréquente : plusieurs estiment que les salaires ne reflètent ni leur niveau de formation ni leurs responsabilités. Les heures supplémentaires non rémunérées et l’incertitude d’emploi sont également mentionnées, compte tenu des exigences particulières de la pratique architecturale. Un autre défi touche la réalisation des heures de stage obligatoires, notamment celles liées aux visites de chantier et à l’administration de la construction.

Certain·es stagiaires ont de la difficulté à accéder à ces expériences en raison de la taille de leur firme, du type de projet ou de contraintes logistiques. Plusieurs souhaitent avoir davantage d’occasions de participer à l’ensemble du cycle de vie des projets. Le processus d’obtention du titre, particulièrement l’Examen des architectes du Canada (ExAC), constitue un autre obstacle.

Les stagiaires mentionnent la structure, le calendrier et le coût comme sources de stress, tandis que les professionnel·les formé·es à l’étranger doivent composer avec une complexité accrue. Enfin, l’accès au mentorat demeure une préoccupation clé. Si plusieurs bénéficient d’un encadre -

ment soutenant, d’autres peinent à trouver des mentors ou à comprendre les attentes du PSA.

Défis futurs de la profession

Les stagiaires réfléchissent de manière critique à l’avenir de la profession. Beaucoup anticipent une pression croissante liée aux défis de main-d’œuvre, notamment la pénurie de talents, les voies limitées pour les diplômé·es et l’attrition découlant de la rémunération, de l’équilibre travail-vie personnelle et des préoccupations liées à la durabilité.

Les changements technologiques constituent une autre préoccupation majeure. Les participant·es prévoient des impacts importants liés à l’intelligence artificielle, à l’automatisation et à l’évolution des outils de conception, tout en s’interrogeant sur la manière dont les architectes peuvent s’adapter sans perdre la créativité humaine. La hausse des coûts des logiciels représente un défi pour les petites firmes et les praticien·nes indépendants.

Les thèmes de la responsabilité environnementale et sociale se sont imposés avec force. De nombreux stagiaires souhaitent une intégration accrue des enjeux climatiques et du design durable dans la pratique. D’autres expriment une préoccupation quant à l’écart entre les idéaux architecturaux et les contraintes réelles, notamment en matière d’abordabilité et de priorités de développement.

Enfin, les stagiaires ont souligné l’importance de mieux communiquer la valeur des services architecturaux. À mesure que les attentes augmentent et que le champ de pratique se complexifie, la profession doit évoluer pour demeurer pertinente et porteuse d’impact.

Ce dont les stagiaires ont le plus besoin Les stagiaires demandent des ressources, une communauté, de la clarté — et qu’on les écoute. Ils recherchent un soutien accessible et concret pour naviguer dans le processus d’obtention du titre : des formations à faible coût, des outils numériques pour consigner les heures du Programme de stage en architecture (PSA) et des cours en ligne alignés sur les compétences du programme. La demande est forte pour des ressources de préparation à l’ExAC et des orientations plus claires concernant le processus de délivrance du titre.

Au-delà du soutien technique, les stagiaires souhaitent avoir accès à du mentorat, à des

ressources en santé mentale et à des conseils sur l’équité et les attentes en milieu de travail. Ils réclament également un plaidoyer en faveur d’une rémunération équitable, d’une transparence dans l’embauche et d’un développement inclusif.

La majorité des répondant·es souhaitent la création d’une communauté nationale de stagiaires afin de se connecter entre pairs, d’accéder à du mentorat et de partager des ressources. Ils imaginent une plateforme favorisant le soutien et une voix collective, en particulier pour ceux et celles qui travaillent dans de petites firmes, en régions rurales ou qui font partie de groupes en quête d’équité. Des rencontres virtuelles, des groupes d’apprentissage par les pairs et des rôles consultatifs pourraient aider les stagiaires à se sentir soutenus et engagés.

Les stagiaires ont également souligné des lacunes de communication au sein de la profession. Plusieurs ont exprimé de l’incertitude quant aux responsabilités respectives des organismes de réglementation, des employeurs et des organisations professionnelles. Ils souhaitent une cohérence accrue des messages à l’échelle des provinces et des outils nationaux — guides d’accueil, webinaires et plateformes centralisées — pour clarifier les attentes et soutenir la mobilité.

La voie à suivre

Le message des stagiaires est clair : ils sont prêts à contribuer, mais ont besoin de plus de soutien. Ils réclament de l’équité, de la clarté, de la connexion et des ressources pratiques reflétant la réalité actuelle de la pratique architecturale.

En tant qu’association nationale, volontaire et non réglementaire, l’IRAC est idéalement positionné pour rassembler les parties prenantes, défendre la voix des stagiaires et créer des outils qui comblent les écarts entre les régions, les firmes et les étapes de carrière. En soutenant cette nouvelle génération, la profession pourra bâtir une base plus forte, plus inclusive et tournée vers l’avenir de l’architecture canadienne.

Visite du Grand Anneau de l’Expo Osaka, conçu par Sou Fujimoto.

Dr. Henry Tsang Architect, AAA, FRAIC, RHFAC Professional architecte, AAA, FRAIC, professionnel RHFAC

In Canada, people see me as an Asian person, a member of a visible minority. What people don’t see is that I am diabetic and have a chronic eye disease. I am also a father of three toddlers, often navigating the city with a cumbersome triple stroller. These perspectives lead me to question how the built environment supports inclusion for people like me.

Canada is one of the most multicultural countries in the world. Yet, underrepresented groups, including women, Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, members of visible minorities, and the 2SLGBTQI+ community, are calling for more accessible and inclusive spaces. Policy developments, such as the Accessible Canada Act, along with accessibility bylaws and codes are being revised and updated. Accessibility Standards Canada and the Canadian Standards Association have been publishing new guides annually, including the widely applied CSA/ASC B651. The Rick Hansen Foundation has also been providing us with a certification program for accessibility. But what about inclusive design?

There is considerable confusion, as terms such as “universal design,” “barrier-free design,” “accessible design,” and “inclusive

design” are often used interchangeably. In my view, inclusive design should go beyond removing barriers to promote social equity and foster a sense of belonging through thoughtful design.

During my sabbatical year in Japan, I had the opportunity to examine this topic in a different cultural context. In contrast to Canada, Japan is one of the most ethnically homogeneous countries in the world, where the notion of “inclusive design” is not widely known. Last May, I was invited to speak on a global panel session at the World Expo in Osaka on this very topic. Renowned panelists from around the world presented award-winning projects, such as the Enabling Village designed by WOHA in Singapore, a poster child for inclusive design. While the conversation around accessibility for persons with disabilities quickly became a call to action, inclusion was loosely addressed, often described in terms such as ”welcoming”, “understanding”, and “enabling diversity. Coincidentally, Japan is the only country in recent years to have hosted two of the world’s largest multinational events: the 2020 Summer Olympics and the 2025 World Expo. Both events and their buildings were planned to welcome a diverse crowd and were specifically designed for inclusion: a perfect petri dish to study inclusive design.

To dig deeper, I attended Sou Fujimoto’s Expo presentation at the University of

Tokyo in August. The master plan embraces a “unity in diversity” concept, with the country pavilions looped inside the Grand Ring, a gigantic wooden structure that serves as a covered walkway and observation deck. “Being on the Ring allows people to appreciate the ‘one sky’ we all look at, regardless of their position on it,” says Fujimoto. I walked around the Ring myself, and I felt encompassed in the space and a sense of belonging to something much bigger, like a drop of water in the ocean. Perhaps one blueprint for inclusive design is to focus on the macro level of human co-existence on the planet. The Expo site was accessible, but wayfinding for people with disabilities remained challenging. Given that each pavilion was designed by a different architect, their functional programming was also inconsistent. Some pavilions were particularly inclusive, offering amenities such as resting areas and prayer rooms.

The Japan National Stadium designed by Kengo Kuma to host the Olympic and Paralympic Games is another case study for inclusive architecture. The design shares similarities with the Expo, featuring a large annular wooden structure and a unifying theme of nature, which Kuma articulated as a “Stadium in a Forest.” The building is thoughtfully designed with the playing field sunken so that spectators can enter the stands at grade from the main level entrance. Innovative accessible features include designated washrooms for service animals and emergency video communication devices for sign language users. I was pleasantly surprised to see some more intentional inclusive features, including multilingual audio and visual wayfinding, playrooms for families with children, sensory-friendly “calm down cool down rooms”, and dedicated viewing areas for wheelchair users with seating for accompanying caregivers.

From a Canadian perspective, inclusive design embodies a deeper meaning. It is at the core of our national pluralistic and multicultural identity. This theory was expressed in A Contributing Community (Canadian Architect, May 2025), in which Ian Chodikoff wrote in celebration of the architectural legacy of the Aga Khan IV, “While multiculturalism emphasizes the coexistence of diverse cultures within

a society, pluralism requires active engagement and collaboration between diverse communities as a necessary building block for resilient and cohesive societies.” The relationship is the same between diversity vis-à-vis inclusion.

Inclusive design in the built environment seeks to create spaces that are welcoming, functional, and user-friendly, bonding a wide and diverse range of people. Although Canada leads global conversations on the social and cultural dimensions of inclusive design, there remain relatively few built case studies that demonstrate environments that are both accessible and truly inclusive. These combined experiences continue to shape my perspective on how architecture can advance both accessibility and inclusion.

Au Canada, on me perçoit comme une personne asiatique, membre d’une minorité visible. Ce que les gens ne voient pas, c’est que je suis diabétique et que je vis avec une maladie oculaire chronique. Je suis aussi père de triplés en bas âge et je me déplace souvent en ville avec une poussette triple encombrante. Ces perspectives m’amènent à m’interroger sur la façon dont l’environnement bâti soutient l’inclusion pour des personnes comme moi.

Le Canada est l’un des pays les plus multiculturels au monde. Pourtant, les groupes sous-représentés — notamment les femmes, les peuples autochtones, les personnes en situation de handicap, les membres de minorités visibles et la communauté 2SLGBTQI+ — réclament des espaces plus accessibles et inclusifs. Des avancées législatives, telles que la Loi canadienne sur l’accessibilité, de même que des règlements municipaux et codes d’accessibilité, sont en cours de révision. Normes d’accessibilité Canada et l’Association canadienne de normalisation publient chaque année de nouveaux guides, dont la norme largement utilisée CSA/ASC B651. La Fondation Rick Hansen offre également un programme de certification en accessibilité. Mais qu’en est-il du design inclusif?

Beaucoup de confusion règne, car des termes comme « design universel », « design sans obstacles », « design accessible » et « design inclusif » sont souvent employés de manière interchangeable. À mon avis, le design inclusif devrait aller au-delà de l’élimination des obstacles pour promouvoir l’équité sociale et favoris-

er un sentiment d’appartenance grâce à une conception réfléchie.

Durant mon année sabbatique au Japon, j’ai eu l’occasion d’examiner ce sujet dans un contexte culturel différent. Contrairement au Canada, le Japon est l’un des pays les plus homogènes au monde sur le plan ethnique, où la notion de « design inclusif » est peu connue. En mai dernier, j’ai été invité à participer à une table ronde internationale à l’Exposition universelle d’Osaka sur ce thème. Des panélistes de renom venus du monde entier ont présenté des projets primés, comme l’Enabling Village conçu par WOHA à Singapour, devenu un modèle de design inclusif. Alors que la conversation autour de l’accessibilité pour les personnes en situation de handicap a rapidement pris la forme d’un appel à l’action, la notion d’inclusion a été abordée de manière plus vague, décrite en termes comme « accueil », « compréhension » et « valorisation de la diversité ». Fait intéressant, le Japon est le seul pays ces dernières années à avoir accueilli deux des plus grands événements multinationaux au monde : les Jeux olympiques d’été de 2020 et l’Expo 2025. Ces deux événements et leurs bâtiments ont été conçus pour accueillir une foule diversifiée et intégrés dans une logique d’inclusion : un terrain d’étude idéal pour observer le design inclusif.

Pour approfondir le sujet, j’ai assisté à la présentation de Sou Fujimoto sur l’Expo, tenue à l’Université de Tokyo en août. Le plan directeur adopte le concept d’« unité dans la diversité », avec les pavillons nationaux disposés en boucle à l’intérieur du Grand Anneau, une immense structure en bois qui sert à la fois de promenade couverte et de plateforme d’observation. « Être sur l’Anneau permet aux gens d’apprécier le “même ciel” que nous regardons tous, peu importe notre position », explique Fujimoto. J’ai moi-même parcouru l’Anneau et j’ai ressenti un sentiment d’appartenance à quelque chose de beaucoup plus grand, comme une goutte d’eau dans l’océan. Peut-être qu’un modèle de design inclusif consiste à se concentrer sur le niveau macro de la coexistence humaine sur la planète. Le site de l’Expo était accessible, mais l’orientation pour les personnes en situation de handicap demeurait difficile. Étant donné que chaque pavillon était conçu par un architecte différent, leurs programmations fonctionnelles étaient aussi incohérentes. Certains pavillons se distinguaient toutefois par leur inclusivité,

offrant des commodités comme des aires de repos et des salles de prière.

Le Stade national du Japon, conçu par Kengo Kuma pour accueillir les Jeux olympiques et paralympiques, constitue un autre exemple d’architecture inclusive. Le design partage des similitudes avec celui de l’Expo, notamment une grande structure annulaire en bois et un thème unificateur axé sur la nature, que Kuma a décrit comme un « stade dans une forêt ». L’édifice est conçu avec soin : le terrain de jeu est en contrebas, permettant aux spectateurs d’accéder aux gradins de plain-pied depuis l’entrée principale. Parmi les caractéristiques d’accessibilité novatrices, on trouve des toilettes désignées pour les animaux d’assistance et des dispositifs de communication vidéo d’urgence pour les utilisateurs du langage des signes. J’ai été agréablement surpris de constater certaines caractéristiques inclusives intentionnelles, comme la signalisation multilingue audio et visuelle, des salles de jeux pour les familles avec enfants, des « salles de retour au calme » adaptées aux besoins sensoriels, ainsi que des zones de visionnement réservées aux utilisateurs de fauteuils roulants avec places pour leurs accompagnateurs.

D’un point de vue canadien, le design inclusif revêt une signification plus profonde. Il est au cœur de notre identité nationale pluraliste et multiculturelle. Cette idée a été exprimée dans A Contributing Community (Canadian Architect, mai 2025), où Ian Chodikoff, en célébrant l’héritage architectural de l’Aga Khan IV, écrivait : « Alors que le multiculturalisme met l’accent sur la coexistence de diverses cultures au sein d’une société, le pluralisme exige un engagement actif et une collaboration entre les différentes communautés, éléments essentiels à la construction de sociétés résilientes et cohésives. » La relation entre diversité et inclusion est similaire.

Le design inclusif dans l’environnement bâti vise à créer des espaces accueillants, fonctionnels et conviviaux, adaptés à un large éventail de personnes. Bien que le Canada soit un chef de file dans les discussions mondiales sur les dimensions sociales et culturelles du design inclusif, il existe encore relativement peu d’exemples construits démontrant des environnements à la fois accessibles et véritablement inclusifs. Ces expériences combinées continuent de façonner ma perspective sur la façon dont l’architecture peut faire progresser à la fois l’accessibilité et l’inclusion.

Architectural professionals discussing fees, procurement and the public image of the sector at a 2025 RAIC Conference session.

Professionnels de l’architecture discutant des honoraires, de l’approvision nement et de l’image publique du secteur lors d’une séance du Congrès 2025 de l’IRAC.

RAIC Fees and Procurement Working Group / Groupe de travail sur les honoraires et l’approvisionnement de l’IRAC

At the 2025 RAIC Conference, the Fees and Procurement Working Group (FPWG) hosted a session examining systemic challenges and emerging solutions related to architectural fees, procurement, and the public perception of architectural value. Guided by six structured questions, delegates engaged in open dialogue. The following is a summary of key insights and takeaways.

Professionalism and public value

Delegates began by reflecting on how current fee structures and procurement processes fail to reflect the value of architectural services. A consistent message emerged: the public image of architects is outdated and undervalued. Many expressed frustration with the view of architects as suffering artists rather than skilled professionals delivering cultural, environmental, and economic benefits.

There was strong support for reframing architecture as a strategic discipline essential to societal well-being, and architects as stewards of the public interest. Delegates emphasized the need for architects to have better tools and language to demonstrate value—particularly through early project

between project scope and evaluation metrics. Delegates encouraged the RAIC to champion procurement reform at all levels of government and to offer firms tools and training for responding to equitable procurement opportunities.

Market conditions and public perception

A strong theme was the need to shift how clients and the public perceive architecture. Delegates emphasized that architectural services should be framed as an investment with long-term economic and social returns. Storytelling, education, and consistent engagement were cited as essential to changing these perceptions.

Clearer service descriptions, including phase-based breakdowns, were recommended to better align with client expectations. Delegates also noted confusion around the RAIC Fee Guide and its application across regions and recommended improving communication and regional alignment to build trust and clarify value.

Emerging models and solutions

decisions that shape long-term outcomes. The RAIC was identified as a key leader in public education and advocacy.

Competition and undercutting

The second discussion focused on feebased competition and undercutting. Delegates noted that excessive price competition weakens quality and undermines professional integrity. Low fees reduce the time and resources needed for thoughtful, responsible design.

Participants highlighted regional differences in practice norms and cost expectations, as well as issues like liability insurance that distort pricing. There was strong support for clearer ethical frameworks and a national architectural policy to guide reform, and for procurement practices that prioritize qualifications and long-term value rather than lowest cost.

When discussing improvements to procurement, delegates suggested several practical strategies: standardizing RFP requirements, using quality-based selection (QBS), and reducing the weight of price in evaluation criteria.

They stressed the importance of model RFP templates, third-party fee reviews to establish fair baselines, and better alignment

Delegates explored innovative approaches to fees and procurement. International tools, such as the Royal Institute of British Architects’ fee calculator, and models like post-occupancy performance contracts were cited as promising.

Participants supported evolving fee models, specialization, and value-based pricing. Several pointed to emerging service areas— such as community engagement and datadriven evaluation—as new revenue opportunities. Technology was seen as both a challenge and a way to differentiate services.

The final discussion focused on advocacy strategies. Delegates proposed a range of initiatives, including public-facing video content, employer branding, national awards, and community campaigns, and segmented messaging tailored to various audiences.

The RAIC was encouraged to develop advocacy and education toolkits that help firms demonstrate how fees relate to outcomes. Building coalitions with allied professions was also recommended to amplify the voice of architecture across Canada.

The session emphasized the urgency of addressing fee and procurement issues. Across all themes, delegates called on the RAIC to serve as a convener, advocate, and educator. This includes

advancing procurement reform, updating tools, expanding education on fees and value, and tracking progress through measurable improvements.

The 2025 Conference affirmed its role as a platform for collective leadership. Continued action is needed through tools like a construction cost calculator, an RFP review process, updates to the RAIC Fee Guide, and a follow-up session at the 2026 Conference.

Lors de la Conférence 2025 de l’IRAC, le Groupe de travail sur les honoraires et l’approvisionnement (GTHA) a animé une séance portant sur les défis systémiques et les solutions émergentes liés aux honoraires d’architecture, aux processus d’approvision-nement et à la perception publique de la valeur des services architecturaux. Guidés par six questions structurées, les délégués ont pris part à un dialogue ouvert. Ce qui suit résume les principaux constats et points à retenir.

Professionnalisme et valeur publique

Les délégués ont commencé par réfléchir à la façon dont les structures actuelles d’honoraires et les processus d’approvisionnement ne reflètent pas la véritable valeur des services architecturaux. Un message constant est ressorti : l’image publique des architectes est dépassée et sous-évaluée. Plusieurs ont exprimé leur frustration face à la perception des architectes comme des artistes souffrants plutôt que comme des professionnel·les qualifié·es apportant des bénéfices culturels, environnementaux et économiques.

Un fort appui s’est manifesté en faveur d’un repositionnement de l’architecture comme discipline stratégique essentielle au bienêtre de la société, et des architectes comme gardien·nes de l’intérêt public. Les délégués ont souligné la nécessité pour les architectes de disposer de meilleurs outils et d’un langage plus clair pour démontrer leur valeur — notamment à travers les décisions précoces de projet qui influencent les résultats à long terme. L’IRAC a été identifié comme un acteur clé dans l’éducation du public et le plaidoyer.

Concurrence et sous-enchère

La deuxième discussion a porté sur la concurrence fondée sur les honoraires et la sous-tarification. Les délégués ont noté qu’une concurrence excessive sur les prix affaiblit la qualité et compromet l’intégrité professionnelle. Des honoraires trop bas

réduisent le temps et les ressources nécessaires à une conception réfléchie et responsable.

Les participant·es ont mis en lumière des différences régionales dans les normes de pratique et les attentes en matière de coûts, ainsi que des enjeux comme les assurances de responsabilité professionnelle qui faussent la tarification. Un fort appui a été exprimé pour l’élaboration de cadres éthiques plus clairs et d’une politique architecturale nationale afin d’orienter la réforme, ainsi que pour des pratiques d’approvisionnement fondées sur les qualifications et la valeur à long terme, plutôt que sur le plus bas prix.

Appels d’offres et réforme de l’approvisionnement

En discutant des améliorations possibles au processus d’approvisionnement, les délégués ont proposé plusieurs stratégies concrètes : normaliser les exigences des appels d’offres, utiliser la sélection fondée sur la qualité (SFQ) et réduire le poids du prix dans les critères d’évaluation.

Ils ont insisté sur l’importance de modèles types d’appels d’offres, de vérifications externes des honoraires pour établir des bases équitables, et d’une meilleure correspondance entre la portée du projet et les critères d’évaluation. Les délégués ont encouragé l’IRAC à jouer un rôle moteur dans la réforme des approvisionnements à tous les ordres de gouvernement et à offrir aux firmes des outils et formations pour répondre à des occasions d’approvisionnement équitables.

Conditions du marché et perception publique

Un thème fort a été la nécessité de transformer la façon dont les clients et le public perçoivent l’architecture. Les délégués ont souligné que les services architecturaux doivent être présentés comme un investissement offrant des retombées économiques et sociales à long terme. La narration, l’éducation et un engagement constant ont été cités comme essentiels pour modifier ces perceptions.

Des descriptions de services plus claires, incluant des décompositions par phases, ont été recommandées afin de mieux s’arrimer aux attentes des clients. Les délégués ont aussi relevé une certaine confusion entourant le Guide des honoraires de l’IRAC et son application selon les régions, recommandant une communication améliorée et une harmonisation régionale pour renforcer la confiance et clarifier la valeur.

Modèles émergents et solutions

Les délégués ont exploré des approches novatrices en matière d’honoraires et d’approvisionnement. Des outils internationaux, comme le calculateur d’honoraires du Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), ainsi que des modèles comme les contrats de performance post-occupation, ont été cités comme prometteurs.

Les participant·es ont appuyé l’évolution des modèles d’honoraires, la spécialisation et la tarification fondée sur la valeur. Plusieurs ont souligné l’émergence de nouveaux champs de services — tels que la mobilisation communautaire et l’évaluation fondée sur les données — comme sources de revenus potentielles. La technologie a été perçue à la fois comme un défi et une opportunité de différenciation des services.

Redonner sa valeur grâce au plaidoyer

La discussion finale a porté sur les stratégies de plaidoyer. Les délégués ont proposé une gamme d’initiatives, incluant la production de contenu vidéo grand public, le marketing des employeurs, des prix nationaux et des campagnes communautaires, ainsi qu’un message segmenté adapté à divers publics cibles.

L’IRAC a été encouragé à élaborer des trousses de plaidoyer et d’éducation pour aider les firmes à démontrer le lien entre les honoraires et les résultats des projets. Le renforcement des coalitions avec les professions connexes a également été recommandé afin d’amplifier la voix de l’architecture à l’échelle du Canada.

Un appel à l’action

La séance a souligné l’urgence d’aborder les enjeux liés aux honoraires et aux approvisionnements. Dans tous les thèmes abordés, les délégués ont appelé l’IRAC à agir comme catalyseur, défenseur et éducateur. Cela inclut la promotion de la réforme des approvisionnements, la mise à jour des outils, l’expansion de la formation sur les honoraires et la valeur, et le suivi des progrès à l’aide d’indicateurs mesurables.

La Conférence 2025 a réaffirmé son rôle en tant que plateforme de leadership collectif. Des actions soutenues demeurent nécessaires, notamment à travers la création d’un calculateur de coûts de construction, la mise en place d’un processus d’examen des appels d’offres, la mise à jour du Guide des honoraires de l’IRAC, et la tenue d’une séance de suivi lors de la Conférence 2026.

The RAIC, in partnership with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC), recently concluded a year-long national initiative to build capacity in Whole Building Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) across the architecture, engineering, and construction sectors. This knowledge mobilization project was launched in response to the urgent need for education on embodied carbon and whole-life carbon accounting as Canada moves toward its climate targets.

Between September 2024 and May 2025, the RAIC delivered nine in-person workshops across Canada, as well as one federal session hosted by the NRC. In total, over 1100 professionals were trained, including architects, engineers, municipal officials, educators, and students. Participants reported a significant increase in knowledge, with 74.7 percent rating the content as very useful and 90 percent indicating they are likely to implement LCA in their practice within three months of completion of the training.

Feedback also revealed a strong appetite for continued learning. More than half the participants indicated they are very likely

L’IRAC, en partenariat avec le Conseil national de recherches du Canada (CNRC), vient de conclure une initiative nationale d’un an visant à renforcer les capacités en analyse du cycle de vie complet (ACV) des bâtiments dans les secteurs de l’architecture, de l’ingénierie et de la construction. Ce projet de mobilisation des connaissances a été lancé en réponse au besoin urgent de formation sur le carbone intrinsèque et la comptabilité du carbone sur l’ensemble du cycle de vie, alors que le Canada progresse vers ses cibles climatiques.

Entre septembre 2024 et mai 2025, l’IRAC a offert neuf ateliers en personne à travers le pays, ainsi qu’une séance fédérale organisée par le CNRC. Au total, plus de 1 100 professionnels — dont des architectes, ingénieurs, responsables municipaux, éducateurs et étudiants — ont été formés. Les participants ont signalé une augmentation significative de leurs connaissances, 74,7 % jugeant le contenu très utile et 90 % indiquant qu’ils prévoyaient mettre en pratique l’ACV dans les trois mois suivant la formation.

La rétroaction a également révélé un fort intérêt pour la poursuite de l’apprentissage.

Participants at the Whole Building Life Cycle Assessment workshop held in Montreal.

Participants à l’atelier sur l’analyse du cycle de vie complet des bâtiments tenu à Montréal.

to pursue additional education in LCA and embodied carbon, with many calling for an advanced part 2 of this curriculum. The results confirm both the impact of the initiative and the growing demand for deeper training in sustainable building practices.

To broaden access and continue the momentum, an open-access, on-demand version of the LCA workshop was launched in June 2025 through the RAIC’s learning management system. This digital course offers the same evidence-based curriculum and practical exercises as the in-person sessions, providing a flexible learning pathway for professionals across the country. Register for this course today https://raic.org/LCAworkshop

The project affirms the RAIC’s commitment to climate leadership through education and collaboration. It also highlights the critical role of LCA literacy in transforming Canada’s built environment. The RAIC looks forward to future collaborations that deepen technical competencies and support the decarbonization of the construction sector.

Plus de la moitié des participants ont indiqué qu’ils étaient très susceptibles de suivre une formation complémentaire en ACV et en carbone intrinsèque, plusieurs appelant à un deuxième niveau avancé de ce programme. Les résultats confirment à la fois l’impact de l’initiative et la demande croissante pour une formation plus approfondie en pratiques de construction durable.

Afin d’élargir l’accès et de maintenir l’élan, une version en ligne libre accès et sur demande de l’atelier ACV a été lancée en juin 2025 par l’intermédiaire du système de gestion de l’apprentissage de l’IRAC. Ce cours numérique propose le même contenu fondé sur des données probantes et les mêmes exercices pratiques que les ateliers en personne, offrant ainsi une voie d’apprentissage flexible pour les professionnels partout au pays. Inscrivez-vous dès aujourd’hui : https://raic.org/LCAworkshop

Ce projet réaffirme l’engagement de l’IRAC envers le leadership climatique par l’éducation et la collaboration. Il souligne également le rôle essentiel de la littératie en ACV pour transformer l’environnement bâti du Canada. L’IRAC se réjouit de futures collaborations visant à renforcer les compétences techniques et à appuyer la décarbonisation du secteur de la construction.

Low carbon. High circularity. No compromise.

A brighter solution for a better tomorrow

GREENGUARD Gold certified for low VOC-emissions.

Scan the QR code to learn more

In late September, a flotilla of 120 canoes travelled from the new mouth of Toronto’s Don River at the MVVA-designed Biidaasige Park, heading towards Lake Ontario. The floating procession paddled past the new developments at East Bayfront, looping back at the CCxAdesigned Sugar Beach. Each of the canoes bore a large silk flag, dyed with materials gathered from Toronto’s shorelines.

The performance, called A Lake Story, was orchestrated by The Bentway, which stewards an urban park beneath the Gardiner Expressway. It was realized in less than a year: last winter, The Bentway received the invitation to curate a flagship performance for a new Water/Fall festival on the harbourfront. Co-executive director Ilana Altman quickly decided that instead of using The Bentway’s plazas, which are set back from the lakeshore, the piece “needed to engage the water proper as a site.”

Early in the planning process, Altman reached out to artist and activist Melissa McGill, who describes her work as “celebrating sustainable traditions and lifting up reciprocal relationships with watersheds and waterways.” McGill conceived of a work that aimed to make Toronto more aware of the shared resource of Lake Ontario, and that would come together as a “big community collaboration.” She chose the launch location the recently renaturalized mouth of the Don River to point to “what is being done in right relationship to waterways in this very challenging moment we’re in.” Through an open call, over 500 locals volunteered to paddle canoes and to provide on-shore support. Says McGill, “the project is a collaboration with the water, the wind, and then with many people.”

Jason Logan, founder of the Toronto Ink Company, developed the colours for the silk flags flown on each canoe by combing the city’s waterways for materials from lake clay from the bottom of Lake Ontario to copper pipe from the Leslie Street Spit. “There’s moments when plants come together with construction waste and bits of rusted wire so many alchemical moments of finding colour in unexpected places,” says Logan. He notes that one of the brightest colours was made from a combination of yellow flowers, some foraged from the banks of the Don River. “Tansy forms this highlighter yellow on the silk,” he says. A particularly moving moment was “seeing that glowing yellow flower colour [on the flags] when the very banks they had been made from was dead [plants].” He adds, “Each silk is a natural archive an archive of a moment in Toronto’s history.”

Photographer Amanda Large is co-founder of doublespace photography. Her image of A Lake Story is from an ongoing series examining the diverse ways in which urban residents encounter and engage with nature in a city environment. From relatively untouched areas, to planned green spaces, to incidental ecological moments, the project explores how natural elements persist within and integrate into the built environment.

A PLAZA WITH A FEMINIST DESIGN VISION BRIDGES OVER AN URBAN EXPRESSWAY, CONNECTING MONTREAL’S CITY HALL TO ITS DOWNTOWN.

ABOVE The mirrored circular enclosure is incised with the names of twenty-one Montreal women—the fourteen victims of the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre, and seven other pioneers of the city. Each full name appears once, and then is deconstructed in letters that sweep around the enclosure, allowing all women to find fragments of their own names.

Through their naming, public spaces in Montreal, as in most cities, have long centred the influence of male leaders past and present on society. Though at one level symbolic, this insidious practice makes a subtle, but profound impact on public space’s role in shaping urban identity. Imagine if the city’s Jean-Drapeau Park, honouring the mayor of Montreal during the Quiet Revolution, was instead named after Thérèse Casgrain, a key figure in Quebec’s women’s suffrage movement. Or if rather than honouring an Italian colonialist, Christophe-Colomb Avenue paid homage to Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) activist Mary Two-Axe Earley, who challenged the male lineage outlined in the Indian Act.

Another common practice more blatantly affects public space: the zealous infrastructural planning that has for over a century prioritized highways and railways, whose paths now sever the urban fabrics of many Canadian cities. This has left behind disjointed spaces that are unwelcoming, unsafe, and inaccessible for citizens especially for women, who are statistically less likely to have reliable access to a car and are therefore more often out walking after dark.

The new Place des Montréalaises, inaugurated this summer, confronts both issues strategically and elegantly. First, it begins a legacy of using public space to foreground the accomplishments of women. (The term Montréalaises specifically refers to female Montrealers, as opposed to the masculine Montréalais.) The effect is already tangible:

this fall, mayor Valérie Plante announced the five station names for the Blue line metro extension, three of which recognize women who have impacted the city including Mary Two-Axe Earley.

Second, Place des Montréalaises joins a legacy of projects that aim to repair urban-infrastructural fissures. It does this by extending a sequence of planned green spaces that bridge over the Ville Marie Expressway, which formerly ran in an open-air trench, returning the ground plane to public use. In Montreal, the broader project of repairing a major infrastructural fissure using large-scale public space is a unique, generational effort. Unlike the commercial-oriented projects of the city’s modernist heyday (like the world-within-a building of downtown’s Place Bonaventure) or recent efforts to reconnect neighbourhoods that focus on more limited modes of use (the cycle and pedestrian link between Outremont and Parc-Ex at the Université de Montréal Campus MIL), Place des Montréalaises is a large-scale plaza that is fully in the public realm, and intended to be freely inhabited.

Indeed, what could have been a simple footbridge connecting Champs de Mars metro station to Old Montreal is instead an immense inclined sculptural plane, hiding the highway beneath a new landscape. This monumental gesture is the work of architectural firm Lemay, artist Angela Silver, and engineers AtkinsRealis, who together won the 2018 international architecture competition for the site. A core team

of designers guided the project, led by Patricia Lussier (Design Principal at Lemay), Andrew King (then Chief Design Officer and Design Principal at Lemay), and Angela Silver (Project Partner and independent artist). According to Lussier, this consistency ensured the coherence of the design, especially as it was refined through years of City committee reviews and changes.

A key design goal was to create a pure, inclined surface defined by an urban meadow that would conceal the hyper-technical supporting structure below. Perhaps even more than a feat of architecture and landscape, Place des Montréalaises is a feat of engineering: the elevated plaza deftly traverses a dense infrastructural junction that includes a metro station and tunnel, a highway, pedestrian tunnels, and a secondary roadway. Several key design moments in fact originate with structural challenges. Take the immense opening at the south end of the site, which frames an elm tree planted at the roadway level below. The void reduces the weight of the structure at a critical moment where the inclined plane becomes a bridge a structural transition that is imperceptible from above. Over time, the elm will grow through the void, becoming part of the meadow.

Place des Montréalaises, in Andrew King’s words, “is not a delicate project.” For King, it is primarily a monumental design, shaped by the

relationship between large sculptural forms. But there is also a high degree of delicacy in the project’s textures, reflections, and planted landscapes.

This play between monumentality and intricacy unfolds throughout the design. For instance, the mirrored walls that conceal a technical building for the highway below are immense, and yet, the continuous curved surface playfully reflects the movement of the city around it.

Into these walls are cut the names of twenty-one Montreal women the fourteen victims of the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre and seven other pioneers of the city. The full names appear once on the mirrors, and are then deconstructed with the letters drifting around the circular surface. As if a strong wind had swept them across the site toward the meadow, more letters appear dispersed along the risers of the amphitheatre steps. As Angela Silver points out, this “allows all women to find fragments of their name, regardless of the language they speak.” The continuously shifting light, shadows, and reflections from the mirrored artwork create a sense of personal interaction, and a sundiallike effect on the surrounding ground that marks the passage of time.

The meadow a field of circular planting beds features twenty-one species of plants, becoming a living representation of the women honoured. While today the rhythmic plan of the planting beds is immediately apparent, soon the vegetation will grow to create softness and moments

ABOVE The planting beds are spaced to allow for clear sightlines even as the plants mature. Wide, inviting ramps—and the inclined plane itself—integrate accessibility across the site.

of intimacy as you move through it. One of the goals during the design phase, says Lussier, was to increase the accessibility of the planted area, which in the initial competition entry was planned to cover an even greater expanse in a denser grid. As the design evolved, the planted field’s area and slope was reduced, its spacing adjusted to allow greater ease of circulation between the circular beds, and a large amphitheatre, ramp, and lawn integrated to transition to the level of Champ de Mars station.

Landscape design is a critical component of Place des Montréalaises but as with any landscape, it is a work in progress, and hard to judge in its first year. The twenty-one new species of the meadow will increase the site’s biodiversity and, in time, the 150 new trees should create an urban forest that offers a reprieve from the dense, bright, and noisy surroundings. The success of the amphitheatre as public space, for its part, is already evident: it creates a natural setting for events, as well as for enjoying the new view of downtown Montreal and of Marcelle Feron’s 1966 stained-glass artwork embedded in the south façade of Champs de Mars station. (Angela Silver comments that Marcelle became, for the design team, the 22nd woman to be specifically honoured through the project; while a parcel immediately west of the metro was developed as Place Marie-Josèphe-Angélique honouring a 23rd woman.)

The potential of the redesigned site to accommodate new social activities is starting to reveal itself. During one site visit, a film screening was being set up; during another, a yoga class was taking place on the lawn. From the opening day, people began meeting for lunch on the wide tables and benches, and along the amphitheatre’s steps. The project’s success as an act of “suturing the city,” to use King’s words, is also clear in the number of people circulating between Old Montreal and City Hall on the south side of the park, the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) on the north side, and the metro station to the west.

In the long term, the project’s success will rest in part on the question of broader accessibility. Will the site provide refuge for surrounding users in all their diversity tourists, city and hospital employees, as well as the unhoused and other vulnerable groups? The intention is certainly there: the wide tables and benches (without armrests) were specified to double as surfaces for sleeping, and a self-cleaning, accessible toilet was included in a service access area under the sloped plane. Beyond the twenty-one names distributed across the site, Lussier points out that the design honours all women by making spaces that are secure, visually open, and well lit.

Place des Montréalaises is ultimately intended, as Lussier puts it, to be “an homage and celebration of women.” Rather than an inert memorial crystallized in time, this is a public space to be occupied and used by all. The initial signs are positive that this is indeed a project that will go beyond the gesture of a name to become a place that offers a better urban realm to all Montrealers: Montréalaises and Montréalais alike.

Claire Lubell is a designer and editor who works in heritage and territorial research at the Montreal cooperative L’Enclume.

CLIENT VILLE DE MONTRÉAL | ARCHITECT TEAM ANDREW KING (FRAIC), PATRICIA LUSSIER, JEFFREY MA, JEAN-PHILLIPPE DI MARCO, VIRGINIE ROY-MAZOYER, ALEXIS LÉGARÉ, MARIYA ATANASOVA, BENOÎT GAUDET, FRANÇOIS MÉNARD, ARNAUD VILLARD, GÉRALD PAU, JEAN DESLAURIERS, RENÉ PERREAULT, ERIC ST-PIERRE, JASPER SILVER KING, THEODORE OYAMA, MICHAEL TAYLOR, JETH OWEN GUERRERO. ARTIST PROJECT PARTNER— ANGELA SILVER, HANNAH SILVER KING, JASPER SILVER KING | STRUCTURAL ATKINSREALIS AND ELEMA EXPERTS-CONSEILS MECHANICAL/ELECTRICAL ATKINSREALIS LANDSCAPE LEMAY | CONTRACTOR CONSTRUCTION GÉNIX SITE SUPERVISOR EXP | LIGHTING OMBRAGE | PLANTING STRATEGY ISABELLE DUPRAS | AREA 19,890 M2 | BUDGET $55 M | COMPLETION SPRING 2025

PROJECT Marianne and Edward Gibson Art Museum, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC

ARCHITECTS Hariri Pontarini Architects (Design Architect) with Iredale Architecture (Architect of Record)

TEXT Adele Weder

PHOTOS Ema Peter Photography

Completed this fall by Hariri Pontarini Architects with Iredale Architects, the Marianne and Edward Gibson Art Museum stands in a prime location on the edge of Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, B.C. Siamak Hariri describes the building as “a new gateway” to SFU, given its location at the eastern end of the mountaintop campus. But to this observer, it feels like something arguably more important: a cultural thoroughfare.

Interdisciplinary connectivity was Erickson/Massey Architects’ big concept for the university’s original 1963 master plan and academic quadrangle. The architecture would encourage professors and students of biochemistry to fraternize with their peers in sociology and so forth, and the cross-fertilization of ideas would enrich the entire intellectual ecosystem. That was the theory, anyway. In reality, the discourse between disciplines rarely achieved the levels envisioned by Arthur Erickson. But this museum may well be the architecture to accomplish that original goal.