Capture the warmth and beauty of real wood with stunning finishes in wood-look visuals. Add whisper-quiet acoustics, like NRC 0.95, and sustainably smart durability that contribute to LEED credits. Order samples at armstrongceilings.com/quietdesign.

Order samples

Canada’s first academic mass timber tower, designed by Moriyama Teshima Architects in joint venture with Acton Ostry Architects, opens on the George Brown College campus in Toronto. TEXT Elsa Lam

A new playground by PLANT Architect for a lab school in Toronto advances best practices in designing for open-ended play. TEXT Julia Jamrozik

The University of Auckland’s urban rec centre, designed by Canada’s MJMA Architecture & Design with Warren and Mahoney Architects, interweaves spatial ingenuity with Indigenous cultural references. TEXT Jade Kake

An informed, empowered client is key to the projects featured in this month’s roundup of leading education projects.

Calgary’s Eau Claire Plaza, Winnipeg’s Cool Gardens, and Toronto’s Biidaasige Park open.

Kyle Lewkowich shares learnings from his time at Manitoba’s Public Schools Finance Board, an expert group that for decades collaborated on the design of schools throughout the province.

Mutual Recognition Agreements with the UK and EU will simplify the process for Canadian architects to practice in Europe. Consultants Ian Chodikoff and Jack Renteria explain why it’s a prime moment for firms to start thinking globally.

Kurtis Chen reviews the CCA’s Groundwork film trilogy.

Suresh Perera visits Canada’s pavilion at the Osaka World Expo.

COVER Limberlost, George Brown College Waterfront Campus, Toronto, by Moriyama Teshima Architects, in joint venture with Acton Ostry Architects. Photo by Doublespace Photography

This month’s issue showcases leading educational-sector projects by Canadian architects. In all cases, these projects were championed by clients who embraced ambitious visions for their sites, and provided the needed resources and support to see those visions through.

At Limberlost, an academic tower on Toronto’s waterfront designed by Moriyama Teshima Architects with Acton Ostry Architects, George Brown College took on a bolder mandate than might be expected of a public college, by hosting an international design competition for the country’s and possibly the world’s first academic mass timber tower.

From the start, the college’s vision extended beyond being the first to achieve this impressive technical feat. George Brown aimed to create a model for a holistically sustainable institutional building; Limberlost eventually included a fully integrated natural ventilation system, with solar chimneys and operable windows. Process was also part of the vision: the college wanted to advance local construction expertise and create a place that would serve as a research and teaching tool for their faculty. Appropriately, the new building will house George Brown’s architectural technology program, putting students and future AED workforces at the heart of the project.

Hiwa, a recreation centre for the University of Auckland, was also commissioned through an international design competition, won by Toronto-based MJMA with New Zealand’s Warren and Mahoney. MJMA partner Ted Watson notes how the university sought to create a place that would be able to support competition-level athletes and host international events. At the same time, they also wanted to create a welcoming place that would integrate Māori cultural knowledge, and contribute to the holistic wellbeing of students that didn’t necessarily identify as athletes. “Even if they just came to sit in the building and have a coffee, that would be a win,” recalls Watson.

In pursuit of a world-class facility, the university also showed a willingness to try new systems, looking to international precedents. The main sports hall includes an all-glass floor, with embedded LED s that activate

to demarcate the courts for different activities. It’s a first-of-its-kind technology for Australasia, as well as a first for MJMA

Client vision was also key to the Sara Jackman Playground, designed by PLANT Architect as part of the University of Toronto’s Dr. Eric Jackman Institute of Child Study Lab School. Unlike a typical school board or municipal client, which might prioritize the minimization of risk, the institute worked with the architects to create a play space that would advance best practices in designing for imaginative, open-ended play.

This meant, in part, enabling types of play that would encourage children to take risks, expanding their physical capabilities, confidence, and resilience. As Lab School Vice Principal Chriss Bogert explains, outdoor play that allows children to exercise their own judgement about risk gives them agency over the pace of mastering physical challenges. “With a teacher nearby to offer guidance, this kind of play strengthens children’s self-confidence and self-esteem,” says Bogert. “Giving children the freedom to decide how they engage with the world honours their rights as individuals, supports them in bringing their ideas into play, and helps them develop the ability to continually reassess what is safe as they grow.”

How can the structure of a procurement agency contribute to design quality? Kyle Lewkowich shares learnings from his time as a senior architect with Manitoba’s Public Schools Finance Board. “It is my thesis that when capital planning entities are staffed by architects with specialized knowledge of their typology, the procurement and delivery of projects can be at once innovative, client-centred, and cost-effective,” writes Lewkowich, in a piece that explores how his team’s expertise contributed to a “new golden age” of school design in the province.

“Much of a project’s success is often clientinspired,” says MJMA partner Tim Belanger. Ultimately, architecture is a team sport one that requires all parties to learn from each other, take risks together, and contribute jointly to successful outcomes.

EDITOR

ELSA LAM, FRAIC, HON. OAA

ART DIRECTOR

ROY GAIOT

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

ANNMARIE ADAMS, FRAIC

ODILE HÉNAULT

LISA LANDRUM, MAA, AIA, FRAIC

DOUGLAS MACLEOD, NCARB FRAIC

ADELE WEDER, FRAIC

ONLINE EDITOR

LUCY MAZZUCCO

SUSTAINABILITY ADVISOR

ANNE LISSETT, ARCHITECT AIBC, LEED BD+C

VICE PRESIDENT & SENIOR PUBLISHER

STEVE WILSON 416-441-2085 x3

SWILSON@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

FARIA AHMED 416 441-2085 x5

FAHMED@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

CIRCULATION

CIRCULATION@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM

Ecophon® FADE™ Smooth spray-applied acoustic plaster.

Cover any curve or angle in just two coats—for seamless monolithic ceilings with less hassle.

SCAN QR CODE TO LEARN MORE

Biidaasige Park opens in Toronto

Toronto’s newest island is celebrating the opening of the redesigned Port Lands’ marquee attraction, Biidaasige Park the largest park to open in Toronto in a generation.

Biidaasige Park the name means “sunlight shining toward us” in Anishnaabemowin/Ojibwemowin is located near Cherry Street on the island of Ookwemin Minising, meaning “place of the black cherry trees.” The park, along with the restored waterway, was designed by a team led by landscape architects Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA), who won a competition for the area’s masterplan in 2008.

The opening of Biidaasige is a landmark achievement in the $1.4-billion tri-government investment in flood protection and waterfront revitalization, which includes over $465 million by the Government of Canada, over $471 million by the Government of Ontario and more than $471 million by the City of Toronto.

The construction of a new, naturalized mouth for the Don River protects 174 hectares of land in the Port Lands and eastern waterfront from flooding. This has unlocked space for future mixed-use neighbourhoods on Ookwemin Minising. It is estimated that the island will be home to more than 15,000 residents, nearly 3,000 jobs, and an additional 15 acres of parkland to be developed in later phases. The initial infrastructure and streetscape design for the community will be led by a team that includes architects Allied & Morrison, GHD, and SLA

Biidaasige Park is opening in two phases. Approximately 50 acres (20 hectares) of parkland opened on July 18, with an additional 10 acres (4 hectares) set to open in 2026, including the first-in-Canada Lassonde Art Trail.

Biidaasige Park’s features include picnic areas, a vibrant playground featuring larger-than-life animal sculptures representing Anishinaabe, Ongwehonwe, and Huron dodems, Toronto’s first ziplines, and a recreation waterplay feature called the Badlands Scramble. The park also boasts recreational trails and cycling paths, including step-downs to the river for fishing and birdwatching, slips for non-motorized boats, the Don Greenway wetland for birdwatching, and two off-leash dog areas. waterfrontoronto.ca

Calgary’s Eau Claire Plaza opens

The City of Calgary has officially opened Eau Claire Plaza, a milestone in the city’s riverfront revitalization.

The redesign of Eau Claire Plaza, led by DIALOG, aims to reposition this downtown site as an amenity and essential civic infrastructure. The Eau Claire Area Improvements program began in 2020, with construction starting in 2021. After four years, the Eau Claire Plaza celebrated its grand opening on July 2, 2025.

The plaza was redesigned as part of the refresh of the Eau Claire area to allow for more flexible year-round uses and improved accessibility. Its new design aims to embrace everyday community gatherings and will provide spaces for hosting larger events and festivals.

The transformation, informed by engagement sessions with Indigenous communities, includes plaza event spaces, an urban beach, a reimagined Olympic monument, a misting water feature that doubles as climate infrastructure and a play element, and wide-open pedestrian zones and seating. The design integrates with the adjacent Eau Claire Market redevelopment, Downtown Flood Barrier, Eau Claire Promenade, and Jaipur Bridge replacement. dialogdesign.ca

The 50-acre park, along with the restored mouth of the Don River waterway, was designed by a team led by landscape architects Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA), who won a 2008 competition for the area’s masterplan.

Alberta issues RFP to repurpose Royal Alberta Museum

Alberta’s government is providing an opportunity to explore proposals to either maintain or repurpose the historical site of the former Royal Alberta Museum and keep it as a significant feature in the City of Edmonton. Originally built in 1965 to house Alberta’s Provincial Museum and Archive, the former Royal Alberta Museum (RAM) building has stood as a cultural landmark for almost 60 years. It first opened its doors in 1967 as part of Canada’s Centennial celebrations, and was renamed the Royal Alberta Museum in 2005 following a visit from Queen Elizabeth II to mark Alberta’s 100th anniversary of joining Confederation.

Located in Edmonton’s Glenora neighbourhood, the original museum has been vacant since 2015. A new $375.5-million Royal Alberta Museum opened its doors on October 3, 2018, in downtown Edmonton.

The original museum building has since faced potential demolition. However, pressures and concerns from the public have pushed the Alberta government to consider adaptive reuse instead. Architects have argued that the mid-century structure, which features a Tyndall limestone façade and interiors with historic significance, could be transformed into a cultural and commercial hub with shops, restaurants, and event spaces.

Recognizing the building’s historical importance and long-standing presence in the community, Alberta’s government initiated a public engagement process to explore potential future uses of the site. Alberta Infrastructure analyzed various options for the site by gathering input from Albertans through an online survey and engaging with First Nations, community members, and other organizations.

“Albertans have a very strong connection to the former Royal Alberta Museum in Glenora. We have heard your suggestions, your feedback and your ideas. We’re creating this opportunity to ensure that we explore all avenues for repurposing the site,” said Martin Long, Minister of Infrastructure.

As such, the province has paused its demolition plans and issued a call for proposals, which is open until September 26, 2025, inviting ideas to repurpose the building. purchasing.alberta.ca

Ontario court finds bike lane removal unconstitutional, Province pledges to appeal decision

Ontario Superior Court Justice Paul Schabas found the province’s plan to remove bike lanes along Toronto’s Bloor Street, Yonge Street and University Avenue violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, putting people at an “increased risk of harm and death.”

The challenge was brought by the advocacy group Cycle Toronto and two individual cyclists a university student who relies on the Bloor Street bike lane to get to school and a bike delivery driver who uses the lanes daily. They asked the court to strike down parts of the law that empowered the province to remove 19 kilometres of protected bike lanes on the three roads.

“The applicants have established that removal of the target bike lanes will put people at increased risk of harm and death which engages the right to life and security of the person,” Schabas wrote in his decision. “The evidence is clear that restoring a lane of motor vehicle traffic, where it will involve the removal of the protected, or separated, nature of the target bike lanes, will create greater risk to cyclists and to other users of the roads.”

Dakota Brasier, a transportation ministry spokesperson, said the province plans to appeal the ruling. “We were elected by the people of Ontario with a clear mandate to restore lanes of traffic and get drivers moving by moving bike lanes off of major roads to secondary

roads,” Brasier said in an email. “To deliver on that mandate, we will be appealing the court’s decision.”

Six cyclists were killed in Toronto last year, all on roads that did not have protected bike lanes, court heard.

Michael Longfield, executive director of Cycle Toronto, called the judge’s ruling “a full win.” “We won on the facts and on the law. The court accepted our argument that the government’s actions increased the risk of harm to Ontarians, and that doing so without justification breaches our most basic constitutional rights,” Longfield said in a statement.

Ford has blamed the Bloor Street, Yonge Street and University Avenue bike lanes for contributing to increased traffic in Toronto and vowed to get the city moving again. He also made removing the bike lanes a campaign issue during the snap election he called and won in February.

The provincial government had argued before the court that cycling is a choice, and risk is assumed voluntarily by cyclists while there are alternative forms of transit available, Schabas wrote, concluding that submission “has no merit.” “The evidence establishes that cycling in Toronto is often driven by reasons of reliability and affordability. For many, such as couriers, their livelihood depends on using bicycles,” Schabas wrote.

Schabas also noted that the government had received advice from experts, reports from Toronto officials and evidence from the city and elsewhere that removing bike lanes “will not achieve the asserted goal” of the law to reduce traffic.

“The evidence shows that restoring lanes for cars will not result in less congestion, as it will induce more people to use cars and therefore any reduction in driving time will be shortlived, if at all, and will lead to more congestion,” Schabas wrote. “This makes the law arbitrary.”

Schabas previously ordered an injunction to keep the government’s hands off the bike lanes until he rendered a decision.

ABOVE Located within The Leaf conservancy, PAIRIDAEZA is one of nine installations created as part of StorefrontMB’s 10th annual Cool Gardens festival.

Alberta’s transportation minister said on July 30 the province is watching the Ontario court ruling with interest. Devin Dreeshen has said in recent months that the Alberta government wasn’t ruling out putting forward similar legislation.

–Liam Casey and Rianna Lim, The Canadian Press

Storefront Manitoba has launched Cool Gardens 2025, a landscape art and design festival featuring nine new installations across Winnipeg. The contemporary gardens, located in Assiniboine Park, Osborne Village, St. Boniface, The Forks, and on the reimagined Graham Avenue pedestrian and active transportation corridor, are in place until the end of September, 2025.

This year’s designs include Petals in Perspective by Noah Shotton, Gavin Buhler, Bayan Shaeri + Owen Tintor, PAIRIDAEZA by Yasaman Kashani, Madeleine Dafoe + Calvin Tan, OSBO by SKHLD, Anything for a Breeze by OSO planning + design, The Living Shore by Nyta Design (Lingzhe Lu + Kun Chen), Woven Relations by University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Architecture, berdie by derdie, Tawnday pe’ oototayan? by Manitoba Métis Federation –National Government of the Red River Métis, and Art City Downtown Street Sculpture by Art City.

“The program for Cool Gardens 2025 focuses on new and existing community partnerships and explores themes of sustainability, lifecycles, and stewardship,” said Abigail Auld, curator, Cool Gardens 2025. “The open call invited teams to consider reused and repurposed materials and to feature local vegetation. Designers were asked to consider the afterlife of their temporary installations, with teams planning plant giveaways and reuse of installation components once Cool Gardens 2025 wraps in September.” storefrontmb.ca

For the latest news, visit www.canadianarchitect.com/news and sign up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.canadianarchitect.com/subscribe

We pioneered the rst PVC-free wall protection. Now, we’re aiming for every 4x8 sheet of Acrovyn® to recycle 130 plastic bottles—give or take a bottle. Not only are we protecting walls, but we’re also doing our part to help protect the planet. Acrovyn® sheets with recycled content are available in Woodgrains, Strata, and Brushed Metal finishes. Learn more about our solutions and how we’re pursuing better at c-sgroup.com.

We pioneered the rst PVC-free wall protection. Now, we’re aiming for every 4x8 sheet of Acrovyn® to recycle 130 plastic bottles—give or take a bottle. Not only are we protecting walls, but we’re also doing our part to help protect the planet. Acrovyn® sheets with recycled content are available in Woodgrains, Strata, and Brushed Metal finishes. Learn more about our solutions and how we’re pursuing better at c-sgroup.com.

PROJECT Limberlost Place, George Brown College Waterfront Campus, Toronto, Ontario

ARCHITECTS Moriyama Teshima Architects, in joint venture with Acton Ostry Architects

TEXT Elsa Lam

PHOTOS Tom Arban, unless otherwise noted

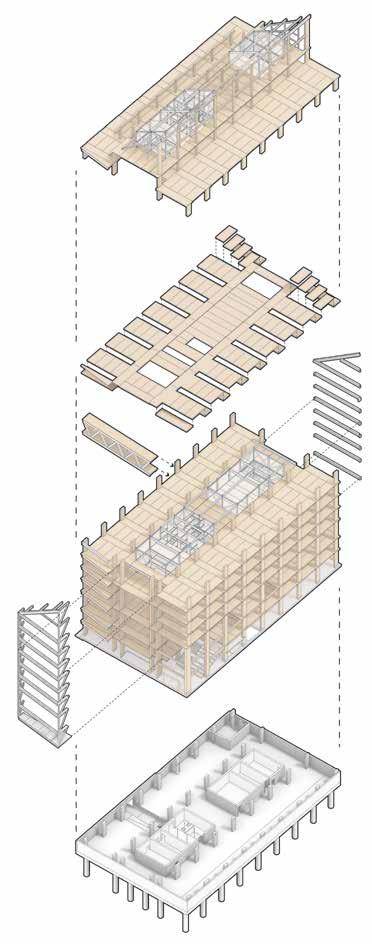

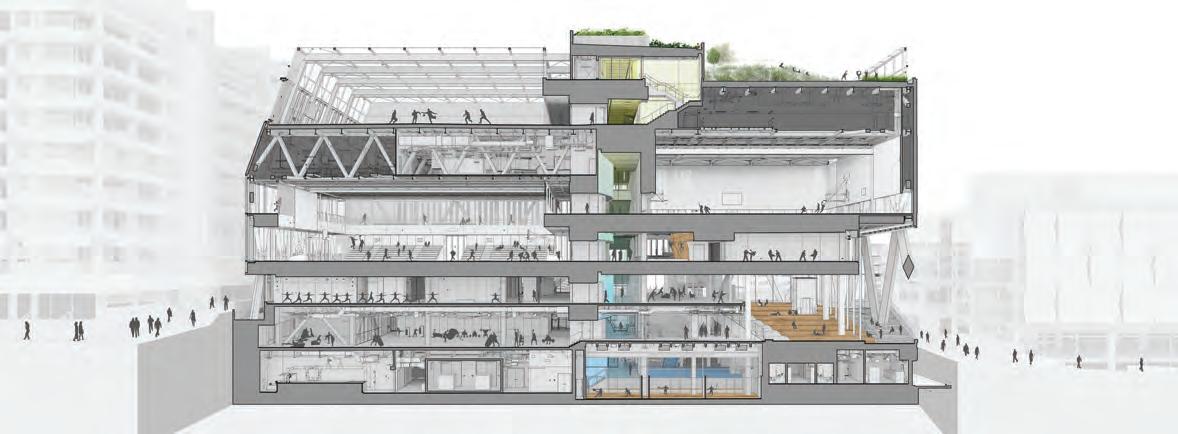

In many Canadian cities, mass timber is becoming more widespread as the structural basis for offices and residential buildings. But the newly opened 10-storey Limberlost Place, part of George Brown College’s waterfront Toronto campus and soon to be home to its architectural technology program, is still a rarity: it’s Canada’s only and possibly the world’s first mass timber academic tower.

To accomplish this feat, the team led by Moriyama Teshima Architects and Acton Ostry Architects needed to achieve the longer spans needed for classrooms with mass timber, as well as to overcome regulatory hurdles related to the occupant load of an assembly-type building accommodating up to 3,400 people in this case, a much higher density than a comparable office or residential building.

Added to the use of mass timber was a host of other sustainability ambitions: a passive, natural ventilation strategy for the building to achieve net-zero emissions, a pre-fabricated façade to save time and materials, and a small-footprint, localized mechanical system that would open up penthouse space.

GEORGE BROWN COLLEGE’S 10-STOREY WATERFRONT ACADEMIC BUILDING IS A NEW KIND OF PUBLIC BUILDING: A MASS TIMBER TOWER PRIORITIZING RENEWABLE MATERIALS, OPERABLE WINDOWS, AND PLENTY OF DAYLIGHT AND FRESH AIR.

LEFT Limberlost’s design includes solar chimneys on the east and west façades that support the building’s natural ventilation. The peaked form refers to traditional Ontario roofscapes, with its slope optimized for capturing solar energy.

Bringing it all together is a design vision of creating a new kind of institutional building: an academic structure with a rich variety of social spaces throughout, and where, like in a home, students and faculty have agency in the interior comfort of the building. It’s simultaneously a place that exudes comfort the main spaces are replete with the forest scent and tactile warmth of wood and a landmark building that anchors Toronto’s waterfront and stands proudly on the international stage.

Building the vision

“There is a complete buy-in from everybody involved that what we’re doing here is we’re changing culture,” says Carol Phillips, Partner of Moriyama Teshima Architects. “We’re building a new kind of public building, where there are operable windows, and daylight, and renewable materials. It’s not about a building lasting a hundred years because it’s so durable, but because people love it and connect with it.”

The spirit of innovation started from the beginning, when George Brown envisaged using a waterfront parcel it owned to create a sustainability-forward building. The level of ambition was high from the outset, with the institution hitting above its weight in its aspirations and in its courage and determination to realize them. “It wasn’t initially ‘We just want a mass timber building,’ it was always more than that,” recalls Nerys Rau, project director at George Brown College. Rather, she explains, the College wanted to create a building that would build sustainability knowledge in the design and construction industries, as well as serving as a living lab for students and faculty to conduct research.

To launch the ideation process, George Brown’s Institute Without Borders ran design charettes to understand the criteria for the building, crystallizing the vision for a low-carbon, future-proofed smart building. Exceptionally, they determined that the project would be awarded through an international design competition.

Moriyama Teshima and Acton Ostry won the competition based on both their design and technical vision. Phillips says that they “embraced

OPPOSITE The triple-height Learning Commons at the base of the building provides a spacious welcome to students and faculty. ABOVE LEFT A threestorey CLT stair is a focal point in the centre of the building. ABOVE RIGHT Located in a skip-stop arrangement on the classroom floors, the Breathing Rooms offer dynamic social spaces for students. The rooms sit alongside the solar chimneys, and are an integral component of the building’s natural ventilation system.

the competition’s constraints, and saw them as opportunities,” as well as proposing a student-centred design that was “less about form-making, and more about space and place making.”

“The brief didn’t have that human-centred aspect, but we brought that to the project,” says Phillips, “and I think it really resonated with the unspoken criteria that George Brown College is one of the most open and inclusive institutions [in Toronto], and its St. James campus is so embedded in the city’s urbanism. How do you bring that sense of urbanism to the waterfront, and create that kind of community within the building?”

The solution, in their scheme, was to create an array of social areas: from the triple-storey Learning Commons at the base of the building, to paired double-height Breathing Rooms on each classroom level, to intimate lounges where students looking for a quieter area might retreat. “There was an understanding that we need to build different spaces for students than we used to,” says Rau. “It’s not just that they’re going to go into a classroom and the faculty’s going to lecture to them. They have expectations of this type of social space: they want to come to campus and be able to be here all day, in various spaces sometimes with other students, sometimes by themselves. And we wanted to ensure that it worked for them in that respect, but also promoted health and wellbeing, and inclusion and accessibility.”

The academic functions are also interwoven with community spaces: a fitness area that provides the waterfront campus with pickleball courts and a climbing wall, a daycare facility with a soaring sheltered outdoor

area. A mass timber stair provides an enticing path through the building’s middle levels, while at top, a college-wide event space is topped by a vaulted ceiling, whose steep angles recall the Gothic lines of Toronto’s historic structures.

In terms of mass timber expertise, the project built on Acton Ostry’s previous experience with creating the 18-storey Brock Commons at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver the tallest contemporary mass timber building in the world at the time of its completion.

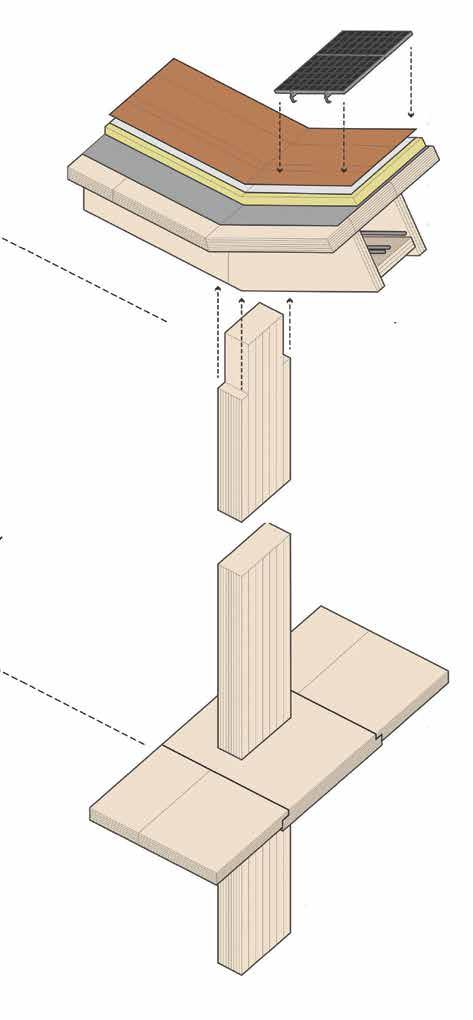

For Limberlost, Acton Ostry principal Russell Acton recalls challenging engineers Fast+Epp to create a mass timber structural system that would span nine metres, the width of typical classrooms, and “that wouldn’t use any beams.” Using regular wood construction techniques for such a span would create beams that were unmanageably deep. Meanwhile, the design required fitting 10 storeys within the site’s 38-metre height restriction.

To create the flattest system possible, Fast+Epp developed an extrawide beam (a “slab band”) supported by columns embedded in the walls (dubbed “wallums”). The structural concept, says Fast+Epp partner Robert Jackson, borrowed from the humble underground parkade, where heights are low and economical, and re-imagined it in mass timber. “You have the flexibility to move partitions because it’s essentially a beamless system,” says Jackson. The engineering details for

the structure have been placed in the public domain, with the intention of opening and enabling future possibilities for mass timber. “It’s a transferable model so that others could see mass timber not as an impediment to density, but as a solution,” says Phillips.

The work towards this solution involving both extensive research and testing of composite spanning members and connection systems was funded by a Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) grant of $4.1 million, along with additional funding from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. The process, says Jackson, included a program of breaking some 60 specimens on testing equipment at the University of Northern British Columbia. “The goal of that research was to ensure that we had a safe and reliable design for Limberlost,” says Jackson, “but also to discern the most cost-effective composite connector” which, the research showed, was a kerf plate “to connect the concrete and the wood.”

“Grants don’t pay for the capital cost [of a project],” says Phillips. “They pay for closing the gap: the extra engineers we need, the peer reviews, the iterations of design, the study tours that we went on to really educate ourselves on how to procure the wood,” which would eventually come from Nordic Structures, based in Chibougamau, Quebec.

Jackson also notes that a second key structural advancement was the use of a structural steel braced-frame core, instead of the conventional cast-in-place concrete core that is seen on most mass timber buildings. “This was a steel core that went up in two-storey lifts, and then was followed by two storeys of wood,” says Jackson, noting that Walters Inc. performed the fabrication and installation of the steel. “It was a pretty novel concept in the mass timber space that’s gaining traction.”

Another major area of innovation is the building’s natural ventilation a sustainability-minded approach that is not a given in university buildings. Germany-based consultant Transsolar was part of the team from the competition stage. “In Germany, opening windows for fresh air is part of the culture,” says Transsolar partner Krista Palen. “It’s an important thing we like to push for, for human comfort and connection to the outside.”

To allow for passive heating, cooling, and ventilation, Palen and her team introduced solar chimneys to the east and west of the building. The needed height for these chimneys one and a half storeys above the highest floor they serve became a primary driver of the building’s form. The chimneys rise to a gable-like peak, made possible by the building’s adjacency to a park. Its southern slope simultaneously gestures to traditional Ontario roofscapes and provides an optimal angle to support photovoltaic panels.

Each of the solar chimneys is composed of two glass walls, with exterior vents at the top and bottom, and glazing that opens to the interior of the building. Diagonal bronze-toned shelves sit between the glass layers, collecting heat and shielding the interior from solar gain.

In the winter, all of the vents are shut, and the warmed air inside the chamber acts as a blanket insulating the building. In the summer, the interior glazing is closed, but the exterior vents are open. The air within is heated by the sun, creating an upward draw as the hot air rises. This allows outside air to flush against the façade, mitigating heat build-up against the glass.

In the shoulder seasons four or five months of the year the building enters natural ventilation mode. The exterior vents at the bottom of the solar chimney close, and the vents at the top open. The interior

glazing also opens. Air from the classrooms is pushed up into the ceiling, passing through acoustical transfer vents into plenums above the corridors. These lead to the two-storey social spaces known as Breathing Rooms adjoining the solar chimneys. From there, the air moves up through the chimneys. As the stale air exits, fresh air is pulled into the building through opened windows in the classrooms and other spaces.

In public areas, the windows are motorized to automate ventilation. In classrooms and small offices, the windows are manually operated. Thermostat screens throughout the building provide notifications glowing green or red when the windows should be opened or closed to optimize passive heating, cooling, and ventilation. “We’re creating a welcome guide that will talk about the building and some practical logistics,” says George Brown’s Nerys Rau. “It will take continued buyin and effort from the College to make sure that changing students and faculty are still being introduced to the building, and educated to the fact that they’re participating in what we’re trying to achieve.”

Transsolar’s Krista Palen explains that part of Limberlost’s innovation is in finding synergies between the operation of the building in passive mode, and when it is actively heated and cooled. “The passive concept and the active concept use almost the same airflow pathway, and that allows us to save a lot of space and duct work,” says Palen. That pathway has been meticulously engineered to maintain the pressure differentials needed for the solar chimneys to function.

Instead of a centralized heating and cooling system, the designers installed two ERVs on each floor. In active mode, fresh air is pumped into the plenum space below the raised floors, and when rooms are occupied, vents automatically open to provide air flow into each space. Radiant ceiling panels fed by EnWave’s deep lake water system provide heating and cooling. “The district energy system is very efficient, and very low carbon,” says Palen.

The use of ERVs means that there is no large mechanical space needed at the top storey of the building. Instead, the top level is a lofty open space with panoramic views of the city that can be used for college events, and is already being booked for external dinners.

Prefabricated cladding, and a mass timber bridge Phillips says that at their first Waterfront Toronto Design Review Panel, it was suggested that they should consider cladding the building in wood. At the second meeting, she recalls panel chair George Baird saying, “I want to offer you an apology. We just didn’t understand enough about how far this building was pushing everything. And to try to encumber you with a combustible cladding on a zero-lot line” which would endanger the viability of the project from a code perspective, and would require cost prohibitive maintenance measures, such as taking out street permits and scaffolding the entire building for refinishing was too much. “We didn’t understand.”

Instead, the team specified a profiled aluminum cladding in a copper-penny hue that evokes wood. The double-height panels were fabricated complete with double-height vertical ribbon windows, reinforcing the building’s vertical rhythm. The panels were prefabricated in Windsor, Ontario, minimizing waste and trucking distance, and delivered just-in-time to eliminate on-site storage. The high windows allow for daylight penetration deep into the rooms, while a high ratio of solid walls limits heat gain.

Originally, says Acton Ostry associate principal Milos Begovic, the idea of prefabricating the façade came from a drive to enclose the timber as quickly as possible. “A lot of the existing systems, including the ones we used at Brock Commons, are designed to be wide and short, with a height limitation of about 12 feet, which isn’t sufficient for an academic floor height,” says Begovic. “That pushed us to seek various envelope contractors who could potentially revise their existing sys-

tems to suit the project demands.” CGI was selected as the fabricator, and worked closely with the architects and sustainability consultant to develop a system that would reach near-Passive House levels of airtightness. “That took really extensive design by the prefabricator, and lots of testing and field review,” says Begovic.

Another notable building feature is a mass timber pedestrian bridge that connects Limberlost to George Brown’s original waterfront campus building to the south. While a handful of mass timber bridges exist elsewhere in North America, Limberlost’s is the first to be six storeys in the air. The bridge was assembled on site, and lifted into place. “It took about a week to put together on the ground, but years before it ever got installed, I remember sketching up how we were going to have to lift it up,” says PCL Construction senior superintendent Mike Love. Love explains that the bridge needed to be lifted on an angle, drifted into place as it was being turned, and pinned on the south end. “That was a critical moment of the lift, because if something didn’t line up by literally a millimetre or two, we could have been in trouble with this 70-foot bridge in the air.” But the extensive planning paid off, and the 30-minute process went smoothly. “I don’t think I took a breath for half an hour,” says Love.

While the project was not administered through an Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) model, an integrated and collaborative relationship between the manufacturer, contractor, client, architects, and engineers emerged that was key to the project’s realization.

One instance was with the concrete topping for the composite slab bands, which the team initially thought could be site poured. But then, recalls Mike Love, they realized that the slab bands would not be structurally sound until the concrete cured. Pouring on site would entail erecting temporary columns and shoring all the way down to the basement, a $3-million expense that would slow the whole site down.

The team considered precasting the concrete at the mass timber facility. “But then Nordic stuck up their hand and said, ‘I can currently put ten slab bands on a truck. If I have to do it with concrete on top, that goes down to two,” says Phillips.

Together, the team came up with the solution of setting up a slab band facility on nearby Commissioners Street in Toronto. “We rented two acres of land, and had the bare slab bands eight feet by 30 feet wide come in,” says Love. “We installed the kerf plates, and the rebar, and the structural screws on top of them, and then we cast the 100 mm of concrete onto that, stacked them, and let them cure for 28 days.”

The system also allowed for ease of delivery coordination, says Love. “When we were ready for a slab band or two, they would bring them over to the site within 15 minutes, and we could drop them into place.”

Another challenge arose with the feature stair an exposed all- CLT wood showpiece that winds its way up through three storeys in the centre of the building. “PCL didn’t think they could get the [mass timber] stair guards in,” says Phillips. “They were too heavy, and the space was too narrow.” But the architects and mechanical engineers realized that the ceiling above the stair would need radiant panels, and would not be

exposed. “The solution was we could put a temporary winch into that CLT, because we didn’t have to be too concerned about the appearance of the CLT there,” said Phillips. “This allowed us to create a truly special moment in the project that celebrates the use of CLT and envelops those who move through the building in it.”

Love describes a careful sequence “this dance” to map in advance the path of each individual panel, some of which weighed upwards of 1,200 pounds, up through the building and to its final location in the complex stair geometry. “A lot of 3D modelling, a lot of spatial awareness went into that.”

Early mass timber projects typically involved specialized mass timber installers, says Robert Jackson of Fast+Epp, and in some other projects, steel and iron workers are erecting mass timber. In the case of Limberlost, the work was “own forces” labour completed by PCL . The contractor brought in experts from a previous mass timber project they had delivered in Denver, and PCL’s carpenters worked with the trade unions to lead specialized construction training building up capacity for future mass timber construction. “The local carpenters’ union really stepped up and said, ‘We’ll facilitate all the training,’” says Love.

“The great thing about this project is that everybody bought into the big idea,” says Begovic. “The consultant team, the client, and ultimately PCL too are really invested in doing something innovative and unique. Most often in construction, you’re just told, ‘This is how we do it, this is how we’ve always done it.’ Here it was different: ‘We’ve never done this before, so let’s all put our heads together and figure out a good way to do it.’”

The municipality and Waterfront Toronto also became enmeshed in the collaborative process. After winning the design competition, the team arranged a special meeting that included the architect and engineering teams, structural engineer, and code consultant from the design side, together with the City’s heads of planning and building, the project’s plans examiner, the fire marshal, and the structural lead for the City. After presenting the project and the credentials of the team, the designers asked: “How are we going to do this?” The City’s first reaction was to insist on encapsulating it all in drywall, concealing the building’s timber bones. But the discussion eventually became more oriented towards a collaborative solution. Since the City did not feel it had the expertise to review the project, it asked George Brown to hire another structural engineer and another fire and life safety expert to peer-review the work. David Moses of Moses Structural Engineers and David Barber from Arup became those people, essentially working for the City, but paid by George Brown another use of the NRCan grant funding. In its final iteration, a full 50 percent of the building’s mass timber is exposed. Some of the most challenging of the alternative compliances had nothing to do with the timber, but were about the interconnections of space. This relates to two building features: firstly, the idea of weaving multi-storey social spaces throughout the building, instead of concentrating them on the lower levels, as is the case with many post-secondary institutions. The building’s main gathering space

is a triple-height Learning Landscape a place for informal lectures and gatherings, with oversized steps that starts at the main doors. In addition, each upper floor includes a pair of two-storey Breathing Rooms, which adjoin the twin solar chimneys in a skip-stop arrangement. The solar chimneys themselves allow for natural ventilation, daylight, and views but also interconnect the entire building.

In the end, the City was satisfied by a combination of fire shutters in the Breathing Rooms to compartmentalize the building, vents added to the outside face of the solar chimneys to expel smoke in the case of a fire, and a second connection to the City’s water mains for firefighting.

“It’s rare that you have projects like Limberlost, where everybody is pushing in the same direction including the contractor, all the way down to the subs, and all the way up to the partner-in-charge at the architectural firm,” says Robert Jackson of Fast+Epp. “This project is a true picture of the stars aligning, with the hundreds of people it took to actually realize this building. It’s an example of what true teamwork can do.”

The key innovations that drove the building are open source, says Phillips. “We’re not holding any secrets because we want these kinds of buildings to be successful for everyone else going forward.” Moriyama Teshima, PCL , and Ontario WoodWorks led over 350 tours through the building during its various phases of construction. Rau emphasizes that post-secondary institutions like George Brown are well positioned

to undertake this kind of research-in-action. “Our drivers are around students, research and sustainability pillars,” she says. “I personally think that the public sector and post-secondary have an obligation to push this type of innovation, because only when we can prove it through this type of work and this type of change, then others will say, ‘Okay, we’ll start to do this.’”

Some of those results are already visible. Limberlost’s innovations are reshaping the Canada, Ontario, and Fire and Life Safety Codes which previously only allowed six-storey non-assembly mass timber buildings. Another firm has developed a composite mass timber beam spanning 12 metres that seemingly iterates from Limberlost’s slab bands.

Phillips says that Moriyama Teshima has also seen the speaking engagements and tours given to share learning around the project begin to inform a more nuanced understanding of mass timber in the industry. She recalls giving one tour where she explained to attendees how the site had to be dewatered until the entire structure was in place, because mass timber is relatively light the building needed to be weighed down enough to avoid the raft slab lifting under the hydrostatic pressure of being on a site close to the lake. A developer on that tour approached Phillips not long afterwards, intrigued by the idea of mass timber being lightweight. His company had a building in development approval, on top of an existing heritage building that was being retained. If it was done in timber, he wondered, would he get more floors? Moriyama Teshima worked with Fast+Epp to conduct a feasibility study, and determined that they could get three additional floors with the lighter-weight and more sustainable structural material. “Given the increase in units, they were motivated to change the design to timber,” says Phillips. “We’re at 11 storeys of purpose-built rental, and that’s now in site plan approval.”

Another innovation, notes Begovic, is in having the width of the corridors spanned by CLT, which is point-supported on adjacent columns. “This leaves two corridors that are completely unencumbered by beams,” he says. While in the case of Limberlost, a pressurized raised access floor is used to distribute mechanically forced air, “in other projects, those [unencumbered] corridors are really good for mechanical and electrical distribution.” He says it’s a move that both Moriyama Teshima and Acton Ostry have since implemented in other educational projects.

As for Limberlost itself? Prior to completion, Limberlost Place had already won 24 international architecture, design, sustainability, and engineering awards including a Canadian Architect award “and we haven’t even applied for the built awards yet,” says Phillips.

Perhaps the most gratifying feedback will be from the faculty and students who will start occupying the building this fall. As I spoke with Phillips and Rau, one of those students newly accepted into the College’s architectural technology program, which will be the building’s main occupant came into Limberlost and asked if he could tour himself around. When he was finished, Phillips asked him what he thought. “I couldn’t be more excited,” he said.

CLIENT GEORGE BROWN COLLEGE | ARCHITECT TEAM MTA—CAROL PHILLIPS (FRAIC), THE LATE ADRIENNE TAM, ALA ZUCHNIAK, CHRIS ERTSENIAN, DANIEL KINNETT, DANIEL TERAMURA, EMMANUEL AWUAH, JAY ZHAO, KAYLEY MULLINGS, MAHSA MAJIDIAN, MARIA PAVLOU, OLIVIA KEUNG, PHIL SILVERSTEIN, VERONICA MADONNA, WILL KLASSEN, BORIS PAVICEVIC, BRYCE STUART, EVELINA TERKA, NICOLE LIAO, NORMAN JENNINGS, SEAN ROBBINS, TRISTAN ROBERTSON. ACTON OSTRY—RUSSELL ACTON, IVAN KUPTSOV, MARK OSTRY, MATTHEW WOOD, MILOS BEGOVIC, NATHANIEL STRAATHOF, NEBO SLIJEPCEVIC, SEAN KOUDELA STRUCTURAL FAST + EPP MECHANICAL/ELECTRICAL

A TORONTO LAB SCHOOL’S OUTDOOR SPACE ADVANCES BEST PRACTICES IN DESIGNING FOR IMAGINATIVE, OPEN-ENDED PLAY.

PROJECT The Sara Jackman Playground, Toronto, Ontario

ARCHITECT AND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT PLANT Architect Inc.

TEXT Julia Jamrozik

PHOTOS Steven Evans Photography

The designers of the new playground at the Dr. Eric Jackman Institute of Child Study (JICS) Laboratory School at the University of Toronto started with a seemingly simple task: to replace two aging play structures, edged by trees but surrounded by a sea of asphalt. In practice, the challenge was much broader and more fundamental: to reimagine how the outdoor space of the Lab School could become an extension of its innovation-centered classrooms and its pedagogy. How could the new playground advance best practices around education and play, and embody the research-based institute’s philosophy of child-centered, independence-fostering learning?

Toronto-based PLANT put their multidisciplinary team to the task, to magical effect. The resulting space is both practical and full of whimsy. While bespoke, it’s also a prototype for how others schools, daycares, city playgrounds can encourage more experimental and inclusive ideas of play.

“Play is many things: joyful, intense, quiet, rambunctious, intrinsically motivating, and deeply satisfying,” reads the Institute’s Outdoor Play Policy. The playspace succeeds by embracing this broad and at times contradictory nature of play. As PLANT ’s Lisa Rapoport puts it, the playground layers opportunities “like a city does,” creating both a density of spatial conditions and an intensity of possibilities of use for children to enjoy.

The teachers are enjoying the new playground, too: not just as an aesthetic upgrade, but also in functional and operational terms. With more choice for kids, there are fewer conflicts, and recess duty has become a more stress-free and pleasing experience for all.

Though all elements on the new playground necessarily follow appropriate codes and safety regulations, there is an overall commitment by all involved to pushing boundaries and embracing risk. This bold approach is enabled through both off-the-shelf elements and bespoke designs, carefully calibrating opportunities for children to grow and develop by challenging themselves and testing their own abilities.

The lively orange Wave by Kompan does a lot of heavy lifting in this department it’s a storey-high structure that enables climbing, running, and sliding at different levels. (After a short adjustment period, some older kids have taken to sprinting across the upper rope lattice in games of tag.) So does the Log Mound installed by Earthscape a hill designed by PLANT and made from logs cut to different lengths and set on end, creating an area that can be used for climbing, hopping, and sitting. PLANT also designed two multifunctional storage sheds playfully named the Onion and the Potato whose curved surfaces, grip handles, and nooks invite exploration. Even the trees themselves, preserved from the original playground and which the children are notably not discouraged from climbing, are part of the fun.

The playground responds to different abilities, encouraging kids to find the spaces which may be right for them, depending on where

they find themselves physically, emotionally and socially that day, or that year. While the kinesthetic challenges of climbing and jumping from different heights may be most obvious, equally important is how PLANT’s design provides spaces to crawl, to retreat, or to hide. There’s also the opportunity to create a mess in a sand area, which can be transformed into a muddy river when kids cooperate to use a water pump.

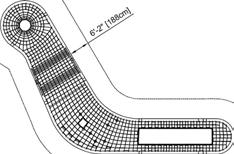

A thirty-metre-long sloping surface meanders its way from the main level of the school to the playground, creating a new connection between inside and out. A playful transformation of the standard accessibility ramp, this significant component of the yard was refined with feedback from individuals with different abilities and lived experiences. Because of its design, the inclined path is not only a means of access, but also a place to play: a curved cut-out holds a planting bed known as the “secret garden,” and the handrail does triple-duty as a climber and a place to hang jackets.

The whole playground is tied together with a figure-eight tricycle route that loops and connects the different zones. This path allows for generous circulation and for the spillover and connection of activities.

When I visit on a warm summer day, the Sara Jackman Playground strikes me as full and messy: both in the best sense possible. There is a plethora of things to do and see, and evidence of play scattered all around from the blue blocks of David Rockwell’s Imagination Playground to milk crates and chalk. These loose parts, as much as the carefully arranged fixed elements, offer choice and agency. It’s a space anticipating activity, but also one that is not prescriptive about where and how one should play.

The achievements of the Sara Jackman Playground may be best understood by considering the alternative. Instead of the typical playground-as-a-collection-of-structures, PLANT has created a set of linked spaces full of play potential. And instead of the lazy shortcut

of a themed playground say, a play space made to look like a village of tiny cabins, a boat, or a spaceship PLANT has leaned on abstract elements that create a rich openness of interpretation and expand the possibilities for play.

Little in the Sara Jackman Playground is truly avant-garde: those of us following the history of design for play have seen similar elements and moves in the work of Aldo van Eyck, Isamu Noguchi, Cornelia Oberlander, and M. Paul Friedberg, among others. But there is nevertheless a confidence in PLANT ’s overall design that is refreshing in our place and time. It is an investment into the realm of play, and into the careful coexistence of opportunities fostered through design.

The project has received professional recognition, including praise from the University of Toronto’s Design Review Committee for its inventive approach to accessibility, and a National Award of Excellence from the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects. The public is curious too, as can be attested by two at-capacity tours facilitated by the Toronto Society of Architects during this year’s Doors Open.

The Sara Jackman Playground is an exemplary model for other playspaces to come. Yet I’m perplexed by its closed gate and the low but nevertheless present encircling fence. Neighbourhood kids who might not attend the school shouldn’t have to trespass to experience a playground like this, and neither should the seniors out for a stroll who may want to just sit and watch. While truly opening the playground to the city may involve risks, those risks like the possibilities of imaginative and open play could also be worth taking.

Julia Jamrozik is an associate professor with Toronto Metropolitan University’s Department of Architectural Science. She is the co-founder of an art and design practice with Coryn Kempster, which focuses on fostering playful interactions in physical space, and is co-author of Growing up Modern: Childhoods in Iconic Homes (Birkhäuser, 2021).

PREVIOUS SPREAD Dubbed “the Potato,” a bespoke storage shed doubles as a climbable structure. Each custom play element in the Sara Jackman Playground underwent rigorous CSA approvals for safety. OPPOSITE A log mound introduces open-ended play possibilities, from running and hopping games to serving as seating for informal presentations. To the left, a leaf-shaped canopy can be used year-round for outdoor story time and other small group gatherings, even in inclement weather. ABOVE LEFT The large-scale Wave structure, developed by commercial playground manufacturer Kompan, includes areas for activities including climbing, sliding, running, and lounging. ABOVE RIGHT An accessibility ramp was reimagined as a curvilinear extension of the playground, with a cut-out for a secret garden, hand and footrails whose lower sections can be used for climbing, and pickets that often serve to hang children’s coats.

CLIENT UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO – DR. ERIC JACKMAN INSTITUTE OF CHILD STUDY | ARCHITECT AND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT TEAM LISA RAPOPORT, FRAIC (MANAGING PARTNER); ERIC KLAVER, OALA (LANDSCAPE PARTNER); JULIE OURCEAU (PROJECT MANAGER–CONSTRUCTION); THEVISHKA KANISHKAN (PROJECT MANAGER–DESIGN), WENDY DUGGAN, KARTIK KUMAR, SIQI LYU, ANTHONY MOURAD, CELINE ABI SABER | STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING LINK INC.| MECHANICAL GPY+ ASSOCIATES ENGINEERING INC. ELECTRICAL SUMMIT ENGINEERING (NOW PART OF MCGREGOR ALLSOP LIMITED) | LANDSCAPE PLANT ARCHITECT INC. INTERIORS 66 M2 INTERIOR RENOVATION BY PLANT ARCHITECT INC. CONTRACTOR MARANT CONSTRUCTION LTD. | CIVIL KWA SITE DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING ARBORIST URBAN FOREST ASSOCIATES INC. | CODE CODENEXT INC. | IRRIGATION DESIGN CREATIVE IRRIGATION SOLUTIONS INC. | SPECIFICATIONS SPECIIFX | COSTING A.W. HOOKER ASSOCIATES LTD. CSA INSPECTOR RS NORTH AMERICA | AREA 1,256 M2 (PLAYGROUND); 66 M2 (INTERIOR RENOVATIONS) | BUDGET WITHHELD COMPLETION JANUARY 2024

NAMED AFTER A STAR IN THE PLEIADES CONSTELLATION, A REC CENTRE BRINGS TRADITIONAL MAORI CULTURAL ELEMENTS INTO THE HEART OF THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND’S URBAN CAMPUS.

PROJECT Hiwa, Recreation Centre, Waipapa Taumata Rau University of Auckland, Auckland Tāmaki Makaurau, New Zealand Aotearo

ARCHITECTS MJMA Architecture & Design and Warren and Mahoney

Architects

TEXT Jade Kake

PHOTOS Scott Norsworthy

/ CAFÉ / AUDITORIUM

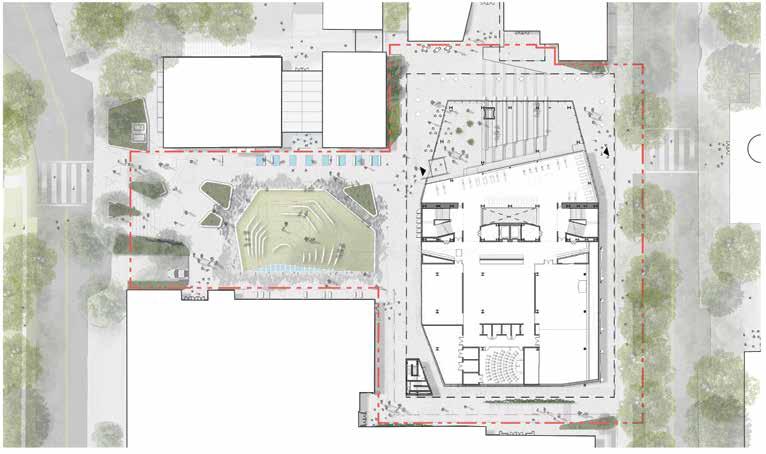

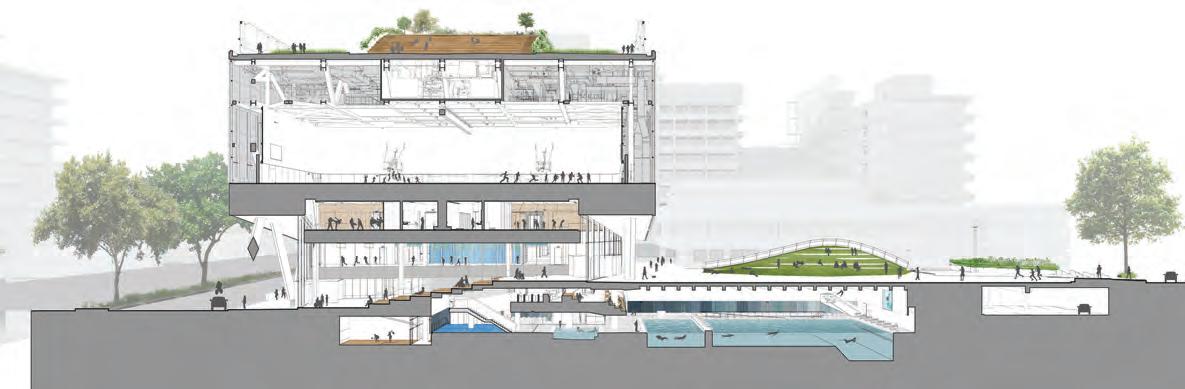

As one approaches from the city’s Albert Park, the building is unassuming: a shimmering, silvery box, that at times recedes and disappears into the sky. And yet Hiwa, the Waipapa Taumata Rau University of Auckland Recreation Centre, has bold ambitions. Designed by Toronto-based MJMA Architecture & Design and Auckland-based Warren and Mahoney, it is placed at the heart of the university’s student precinct. It aims to bring hauora a holistic concept that encompasses social, physical, mental, cultural and spiritual wellbeing into the centre of campus life.

The land the building sits upon and its past, present and future associations forms the tūāpapa or foundation for the project. Part of the original gift made by Apihai Te Kawau of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei for the establishment of the city, earlier narratives speak to Waihorotiu, the dormant awa (river) beneath the surface, and the taniwha (guardians of waterways) that reside within.

The plaza is topped with a mound that brings additional volume and light into the aquatic hall below. The site designated for a Recreation Centre was a T-shaped, sloping parcel and offered a complex set of physical constraints. To accommodate the desired program, the architects made the decision to raise the main sports hall and place the aquatic hall below grade, freeing up the ground plane to create a new student plaza. The text engraved on the concrete steps of the turfed mound in Hiwa’s plaza hints at the land’s history: “Rangipuke the papakāinga in Albert Park” and “Te Horotiu a pā site adjacent to Rangipuke.” The constructed mound itself nods to pā terracing, and offers students a place to sit, to pause, to enjoy the sun.

Ko wai a Hiwa? He aha te orokohanga o tēnei ingoa? Who is Hiwa? What is the origin of this name? The name of the building, Hiwa,

TOP The mound nods to the pā terracing of traditional Māori hillforts, while also offering a place for students to sit, meet, and lounge. The mound is the focal point of a new campus plaza, opened up by the building’s massing strategy. BOTTOM The text engraved on the concrete steps of the turfed mound hints at the land’s history: “Rangipuke—the papakāinga in Albert Park” and “Te Horotiu—a pā site adjacent to Rangipuke.”

references Hiwa-i-te-rangi, a whetū or star within the constellation of Matariki (also known as Pleiades) that is associated with moemoeā and wawata, dreams and aspirations. ‘Hiwa’ is a verb that refers to vigorous growth, and ‘i te rangi’ means simply, in the skies or the heavens. As Māori, we send our wishes, dreams and hopes for the future to Hiwa-i-te-rangi at the time of the Māori lunar year, which begins in late June or early July as Matariki rises.

Each entry point to the building is a lightbox, bright and welcoming and in its first months, the building saw over 500,000 visits through its doors. The building’s main entry is off Symonds Street, the street forming the central spine of the campus. Inside the double-height lobby, a set of generous seating stairs ascends to the plaza and secondary Albert Street entrance. The stairs are a light-coloured timber, with moveable cushions and seating elements in blues and greens. Symonds Street is busy, and the stairs offer a prime position for people-watching. Students sit and work, chat and doze.

Moving through the lobby, a series of small level changes is expertly navigated through gentle, accessible ramping. The soft grey tile used throughout the open public areas gives them a distinctly urban feel. Accessibility is key, and there is careful consideration given to creating low-sensory areas, and minimizing glare and noise reverberation throughout. All signage is trilingual: te reo Māori, English, and braille, including additional conceptual markers and explanations that go beyond literal translation.

The cultural narrative drives a wayfinding strategy that includes patterns derived from Māori culture, and shifts in colour to mark level changes. The whakairo or patterns, which are mapped to specific activity areas, can also be broadly read to relate to different aspects of the build-

Satisfy safety regulations with Aluflam, the key system featuring true extruded aluminum vision doors, windows and glazed walls, fired-rated for up to 120 minutes. Aluflam products are indistinguishable from non-fire-rated doors and windows and are available in a wide portfolio of most architectural finishes.

ing, including the delineation between active and passive spaces (Ao Kapakapa), the flow and movement through vertical and horizontal circulation (Ao Korikori), the connection to place and context (Tuku Whenua), and accessibility and sensory elements (Ao Riporipo).

The cultural concept was led by Karl Johnstone (Rongowhakaata, Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki, Ngāi Tāmanuhiri) and his team at Haumi, a specialist creative agency that spans the intersection of graphic design, branding, wayfinding and visual art, and the building’s cultural design elements have been developed through close collaboration between Haumi and MJMA’s in-house Environmental Graphic Design team. Haumi’s work is underpinned by in-depth knowledge of mātauranga and tikanga Māori (Māori knowledge systems and customs).

One of the two main stairwells offers a choice of pathways to hīkoi (walk) or oma (run), the beginning of a one-kilometre track circuit that winds through the building, traversing levels 0-6. The vertical colour progression unfolds in vertical battens lining the circulation core. On the lower level, the battens are blues interspersed with some greens, denoting the first stage in a transition from ocean to sky, from moana to rangi. In te reo Māori, the words used to describe the blue of the ocean are a multitude and include tai tonga (a bright blue colour), tai koehu (a dishwater grey-blue shade, a stormy blue), and moanauri (a deep ocean blue).

Beyond the CNC-routed reception desk, a large wall-hung hand-carved takarangi is by the carvers of Te Wānanga Whakairo o Ruawhetū, led by tohunga whakairo (master carver) Te Taonui-a-Kupe (James) Rickard (Tainui, Ngāti Porou). The takarangi spiral refers to creation, balance, and the connection to the heavens. On this gym floor level, the whakairo (pattern) used is Tuku Whenua (derived from aramoana, pathways to the sea), denoting connection to whenua (land) and referencing Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei and the gift of land for the establishment of the city.

The main stairs’ handrails include inserts made from a native timber and patterned with etched grooves, whose tactile quality invites the hand to linger. Speaking to the whakapapa of the site, these inserts are carved from a pōhutukawa tree that once grew from the whenua. Fitting, perhaps, that Pōhutukawa is the balance to Hiwa-i-te-rangi the opposite part of a pairing, signifying loved ones who have passed, the name of the whetū (star) itself a reference to the Pōhutukawa tree located at Te Rerenga Wairua, the place of departure for spirits. The star’s appearance is also a tohu, a sign of those close to us who will pass on soon. Some of the handrail insets are a lighter coloured timber, some are darker, but always marking a threshold, an important moment of transition.

At the lower level, there is a sense of calm, and the space is awash with blue light. Students sit in circles on the floor, idle in hammocks or on beanbags. Some wear headphones and are engaged in focused work, while others are meeting with friends in small groups. A cavelike space, te wāhi whakatau wairua (a space to calm the spirit), this area invites solitude, the noise softened by acoustic panels on three sides and carpet below. A strip of indirect light spills out of the back wall above and below, providing a minimum amount of illumination. The space looks out to the squash courts on one side and the restorative pools on the other. The water glistens but is perceived dimly through frosted glazing, the application of patterns an artful exercise in positive and negative space. Ao Korikori based on the raperape

OPPOSITE Vertical battens lining the circulation core shift in colour to mark level changes, and a transition from ocean to sky. ABOVE In the main lobby, seating stairs are a prime spot for people-watching along bustling Symonds Street, the main campus throughfare.

pattern, an interlocking spiral used in tā moko (traditional tattooing), including pūhor is used here, evoking the movement of water and the shifting of people.

Inside the pool area, the wai koropupū (hot pool) space is awash with gentle conversation, blue lights providing illumination from within the pool, which includes full wheelchair access. The tiles here and around the main aquatic basin are tactile, enabling gentle footfall and pre-

TOP A hand-carved takarangi refers to creation, balance, and the connection to the heavens. BOTTOM The reception desk is CNC -routed and hand-finished with a Tuku Whenua whakairo (pattern) used derived from aramoana, pathways to the sea. The whakairo denotes connection to whenua (land) and references Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei and the gift of land for the establishment of the city.

venting slipping. Strip lights above the pools offer diffuse lighting without harsh bright spots. It is slightly noisier here, with the splash of lane swimmers and the conversation of lifeguards, but not overwhelming. The undulating ceiling fans out to a higher space above the diving board a bump that forms the seating mound in the plaza above.

A spectator zone overlooking the pool area is warm like a womb: a low-sensory space to curl up. The air is noticeably warmer, and the ceiling steps down, narrowing the viewing area over the pool. Spectating is possible, but the pool area does not dominate, providing a gentle backdrop to another cave-like space to whakatau wairua (settle the spirit).

Upstairs from the main lobby, Level 1 houses group fitness studios. The treadmill area is set up like a stage or deck, looking out over the main lobby. On Level 2, the colour scheme becomes lighter, yellows and greens interspersed like leaves of early autumn, evoking yellow plants gone to seed. A large multi-sports court is technologically impressive, with floor-embedded LED lights under glass that can be electronically configured to suit a myriad of sports yet the floor feels soft and springy underfoot.

An inviting corner dance studio on this level is nestled in treetops, light and bright. The subtleties of the glazing strategy are apparent here: the fritted patterns are more open and transparent on the court side, and more closed and opaque on the dance side; one inviting spectating, the other providing privacy and just a hint of activity and connection. The whakairo used on this level include Ao Riporipo (a pattern derived from unaunahi, fish scales), denoting movement and flow, and connecting to the activities of kanikani (dance) and gentle movement that occur in these spaces.

On Level 3, the central core is almost entirely green. Some of the te reo Māori words for shades of green karera, matomato refer to the green of new shoots, and the green of foliage. Here, the colours speak to a transition through the canopy of the forest. The multi-sports courts on this level are permeated with a sense of lightness and calm, with perforated metal brise-soleils letting in daylight but not direct sun. The ara omaoma (indoor running track) includes a loop on this level, with views to the main sports hall below.

At the point of arrival to level 5, the central, coloured core has completely transitioned to yellow. In the Māori language, the yellows kōwhai, karamū, whanariki relate to the yellows of flowers, plant dyes, and sulphur, but here, the colour brings us yet closer to the sky. Exiting through a vestibule gives access to a rooftop sports field that is open to the elements, occupying the south half of the building. Wind and rain whip your face, a connection to Ranginui (the sky father). The upper levels of adjacent buildings are visible, giving this level a distinctly urban feel, like the setting of a music video.

One last stop is at level 6, which gives access to the north rooftop, the culmination of the jogging loop and an area for leisure. The coloured core now includes pink. Of the te reo Māori words for pink, mā tuawhero feels the most appropriate: a white that is pinkish, the light red of a sky. The whakairo used on this level is Ao Tukupū (derived from purapura whetū, the myriad of stars), denoting limitless potential and the connection to the stars. The roof terrace includes expansive views to Waitematā and across the city.

On the day that I visit, a cool breeze lifts off the harbour. This final roof terrace is an invitation for students, having completed their time at the recreation centre, to linger just a little longer. In the spirit of Hiwa,

it’s a pause that reminds us that the growth towards our dreams and aspirations in a university setting is not only about academic learning. It’s about integrating physical, mental, social, cultural and spiritual wellbeing, and developing a deeper understanding of our connection to land, to each other, and to our shared histories. It’s ultimately about finding our place as tangata whenua (people of the land), tangata tiriti (people of the Treaty) or as manuhiri (guests) in te ao (the world).

Māori architect Jade Kake is director of Matakohe Architecture + Urbanism. Her design practice is focused on working with Māori organizations on their marae, papakāinga and civic projects, and in working with mana whenua groups to express their cultural values and narratives through the design of their physical environments.

CLIENT WAIPAPA TAUMATA RAU | UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND | ARCHITECT TEAM MJMA—TED WATSON (FRAIC), TARISHA DOLYNIUK (FRAIC), VIKTORS JAUNKALNS (FRAIC), ANDREW FILARSKI (FRAIC), CHRIS WANLESS, AARON LETKI, DARYL BIEDRON, HALEH GHODSIMAAB, MELISSA LUI, LUKE DUROSS, PATRICK KNISS, AFSANEH TAFAZZOLI, JANICE WOO, JANOUQUE LERICHE, ALEXANDRA SERMOL, ANDREW CHUNG, KENYON JIN, JUSTIN BOUTTELL, ZAVEN TITIZIAN, SNEZANA SMILEVA. WARREN AND MAHONEY—BLAIR JOHNSTON, DAVID MAHON, TONY DEW, ANTONIA LAPWOOD, SOANE TUI, DAVID INGLEY, ROD RUDDUCK, BARRINGTON GOHNS, EDMUND IBALIO, SOANE TUI, JAMES MORGAN, ANDREW BARCLAY, SEBASTIAN HAMILTON, MITCHEL CANTLON, CHRIS KERR, SOWMYA GNANASEKARAN, JAE JEONG | EXPERIENTIAL GRAPHIC DESIGN MJMA ARCHITECTURE & DESIGN (TIM BELANGER, VANESSA TARASIO, CHRIS WANLESS, RAYMUNDO PAVAN, ANDREA HERRERA BETANCOURT, LUCAS POSTLETHWAITE) | CULTURAL DESIGN & FACILITATION HAUMI NZ LTD. (KARL JOHNSTONE, RICKY-LEE MITAI, AARON TROY, ANI MCGAHAN) CONSTRUCTION HAWKINS STRUCTURAL/SERVICE/MECHANICAL BECA LIMITED BUILDING ENCLOSURE MOTT MACDONALD NEW ZEALAND LIMITED | LANDSCAPE LANDLAB | PLANNERS BARKER & ASSOCIATES | PROJECT MANAGEMENT COLLIERS PROJECT LEADERS | AREA 22,500 M2 | BUDGET $275 M NZD COMPLETION FEBRUARY 2025

TOTAL ENERGY USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 197 KWH/M2/YEAR | THERMAL ENERGY DEMAND INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 112 KWH/M2/YEAR | GREENHOUSE GAS INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 22 KGCO2E/M2/YEAR

ABOVE LM Architectural group’s major addition and renovation to École

in La

Manitoba, was completed with the collaboration and support of the province’s Public Schools Finance Board. As part of the project, the former gymnasium floor was repurposed as a focal wall installation.

WHEN CAPITAL PLANNING ENTITIES ARE STAFFED BY ARCHITECTS WITH SPECIALIZED KNOWLEDGE OF THEIR TYPOLOGY, THE PROCUREMENT AND DELIVERY OF PROJECTS CAN BE AT ONCE INNOVATIVE, CLIENT-CENTERED, AND COST-EFFECTIVE.

In 2008, I accepted a newly created architect position within a unit called the Public Schools Finance Board (PSFB) PSFB was the capital plan management entity for the Manitoba Department of Education, with responsibility for planning, programming, and architecture/engineering design for K-12 public schools and school-based childcare facilities. I was hired specifically to help PSFB meet its obligations under the newly enacted Manitoba Green Building Policy, which required that all Provincially-funded major capital projects achieve a minimum LEED Silver certification.

Initially assigned the illustrious job title of “Architect 3,” I eventually became the Architect for Sustainable Schools, and then the Senior Project Leader. Over nearly 15 years, I was fortunate to make a significant contribution to what we called the “new golden age” of school design in Manitoba (the first “golden age” referring to the province’s circa 19101930 schools).

This era came to an organizational end in November 2020 with the legislated dissolution of the PSFB and culminated for me personally in June 2022, when I, as the PSFB ’s final member remaining in the Department of Education, departed for a new position.

The story of PSFB however, is important from an architectural perspective: both as historical narrative, and as a best-practice example of how to staff and operate an architect/engineer-led project management and procurement entity. The results of the PSFB ’s collaborative, architect-guided Integrated Design Process can be seen in the resulting high-quality, goal-driven designs, the entity’s reputation for effective and fair consultant procurement, and the unit’s support for client and user stakeholder contributions.

The Manitoba Public Schools Finance Board Act (1967) first created the PSFB as a work group within the Department of Education, reporting to the Deputy Minister. In its first decades, the principal functions of the PSFB were administering a capital support program for education capital projects, consulting with school divisions to assist in developing and maintaining a five-year capital plan and operating plan, and providing financing structure to support capital improvements for school facilities.

Over time, the number of school divisions consolidated from over 100 (including many in rural areas with two- or four-room schoolhouses) to the 37 that exist today. In tandem, the major capital budget

for PSFB evolved to include separate planning and funding streams for new schools, major additions/renovations, special program initiatives, mechanical system upgrades, structural remediation and building envelope upgrades, barrier-free accommodation upgrades, and portable classroom installations.

By the time I joined PSFB in 2008, new leadership at the Director level under Rick Dedi, responding to the desires of the government of the day, had forged an ambitious transformation of the mandate with respect to capital planning. At this time, the PSFB Act was amended to require that the financial resources of the capital support program specifically “meet the needs of students and school divisions” and consider the following factors (edited here for brevity) when providing funding for projects:

T he curriculum and instructional needs, particularly for kindergarten to Grade 8;

t he requirements of students with special needs;

t he community use of schools;

t he influence of the design of school buildings on the health and safety of students and other school users;

sustainable design;

t he life-cycle costs of school buildings;

heritage preservation;

t he inclusion of early learning or childcare facilities in a new, or renovated, school.

With this mandate, the PSFB was recalibrated to design schools “to meet the scope and intent” of the Act. The means of achieving this recalibration was to be through the direct project participation of the design professionals within the PSFB , including architects, mechanical and structural engineers, an interior designer, and a landscape architect. These professionals would be embedded within Integrated Design Process (IDP) meetings as “owner/client stakeholder” in partnership with the school division. This in-house professional team would also collectively and collaboratively be responsible for reviewing all consultant design submissions to ensure that the design mandate would be met through the Integrated Design Process.

From within the department, I then developed four key project-charter style goals to define the details of this mandate for the consultant teams. These project-charter goals were embedded in the preamble of every RFP issued for consultant services, and required architects to achieve the goals of:

RIGHT At Queenston School, Public City Architecture’s entry link between the existing school and a new gymnasium features Manitoba’s first school-based use of bird-friendly glazing.

OPPOSITE TOP A second-storey link between the existing Laura Secord School and a new gymnasium by LM Architectural Group preserves outdoor play space below.

OPPOSITE BOTTOM LEFT The new main entry of Stantec’s École communautaire St. Georges allows for community access after hours.

OPPOSITE BOTTOM

RIGHT Prairie Architects’ renovation and addition to École communautaire Gilbert-Rosset includes a new gymnasium.

Sustainability: High degree of sustainability for design and construction; D urability: Construction to meet a 75- to 100-year design lifecycle for the facility;

Energy Efficiency: High energy efficiency and environmental performance, with defined and achievable metrics for Energy Use Intensity (EUI); and most importantly:

Liveability: Coordination of built form with curriculum/teaching goals, and designing so that consideration of the student and instructor environment is foremost.

The combination of programming responsibility, authority over design standards (both architectural and engineering), professional-led project management, selection/evaluation of consultants, and budget authority allowed PSFB to achieve a consistent track record of high-quality new schools, school addition/renovation projects, and engineering retrofit projects. The tangible results of this track record were a “new golden age” generation of school projects that were innovative, that advanced the use of new materials and technologies, that addressed different teaching methods and pedagogies, and that successfully explored new technology options for mechanical systems engineering and energy efficiency.

Case studies

As I look back at PSFB ’s accomplishments during my time there, I am impressed by even this abridged list of milestones and benchmarks that illustrate innovation in school capital projects:

Completed the 2nd LEED Platinum school in Canada, at Amber Trails School, Seven Oaks School Division, Winnipeg, by Prairie Architects;

More LEED projects than any other single entity in Manitoba; F irst large-scale use of photovoltaic panels on a school project in Manitoba, at Collège Jeanne-Sauvé, Louis Riel School Division, Winnipeg, by Number 10 Architectural Group; Development of effective strategies to store rainwater roof drainage in crawlspace cisterns for use in toilet flushing, and other non-potable uses; F irst Manitoba-based comparative analysis of different anti-bird strike glazing strategies used across a number of projects;

Authorship of “School as a Teaching Tool” LEED Credit initiatives that connect curriculum to the design/construction process, including permanent installation of artifacts at the schools to reflect the genius loci of the site;

Creation, and written documentation, for a new typology for Outdoor Learning Environments (OLE), connecting school sites to curriculum/learning outcomes.