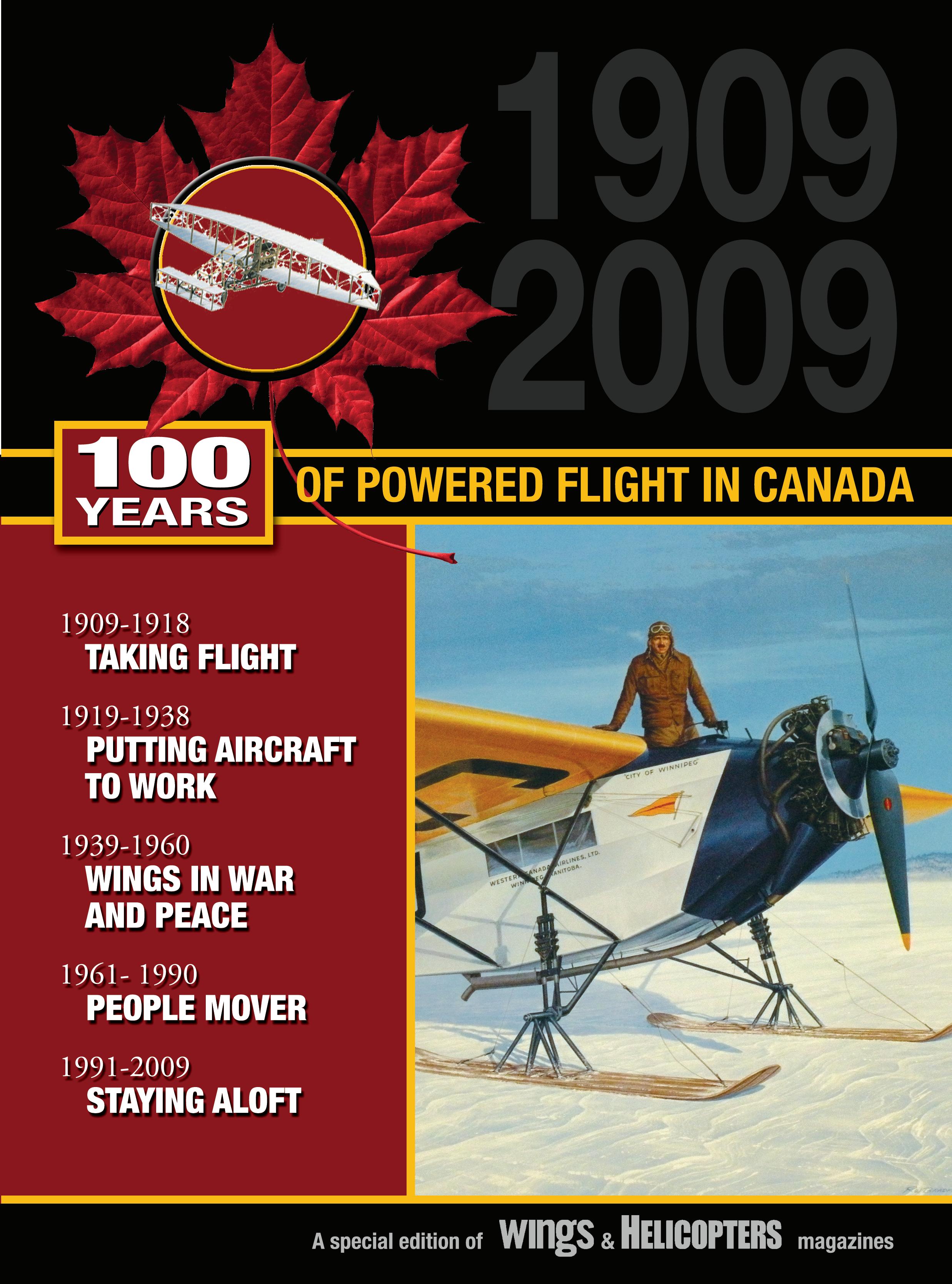

In commemoration of Canada’s 100th anniversary of powered flight, we are pleased to offer our readers this special edition supplement to Wings and Helicopters magazines. We hope that it will become a valued keepsake for you, for many years to come.

The story of this country’s rich aviation history is a source of pride for all Canadians, the intelligence and vision of those who came before us – inspirational.

To tell the story, we called upon two of our most experienced and knowledgeable writers, Peter Pigott and Raymond Canon. Peter is one of Canada’s most renowned aviation historians and he graciously agreed to write the five main sections of this supplement. You can read his biography on page 5. His work, as you will see, speaks for itself.

We also prevailed upon Wings columnist Raymond Canon to provide us with an introductory overview of the global impact of our aviation history. Those of you familiar with Ray’s “A Look Back” column will

already know about his passion for Canadian aviation.

There are many others who contributed. We would especially like to thank Justin Cuffe of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame, Paul Cabot from the Canadian Air & Space Museum, Marie-Josée Cadieux from the Canada Aviation Museum and BGen Gaston Cloutier and his staff from the Department of National Defence for supplying us with a host of great photography.

The cover and interior design of this publication were created by production manager Angela Simon of Annex Publishing and the meticulous layout done by Annex production artist Brooke Shaw.

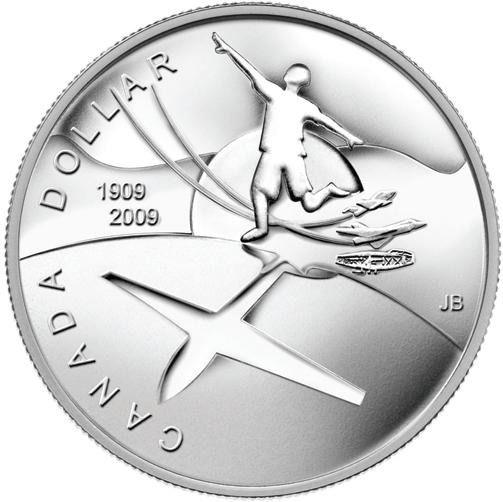

We would also like to thank those who sponsored this edition: Hamilton Watches, Petro Value, the Silver Dart Centennial Association and the Royal Canadian Mint. Without them this commemorative edition would not have been possible.

As the editors of this project, we learned much about Canada’s aviation pioneers and, as we did, our sense of admiration

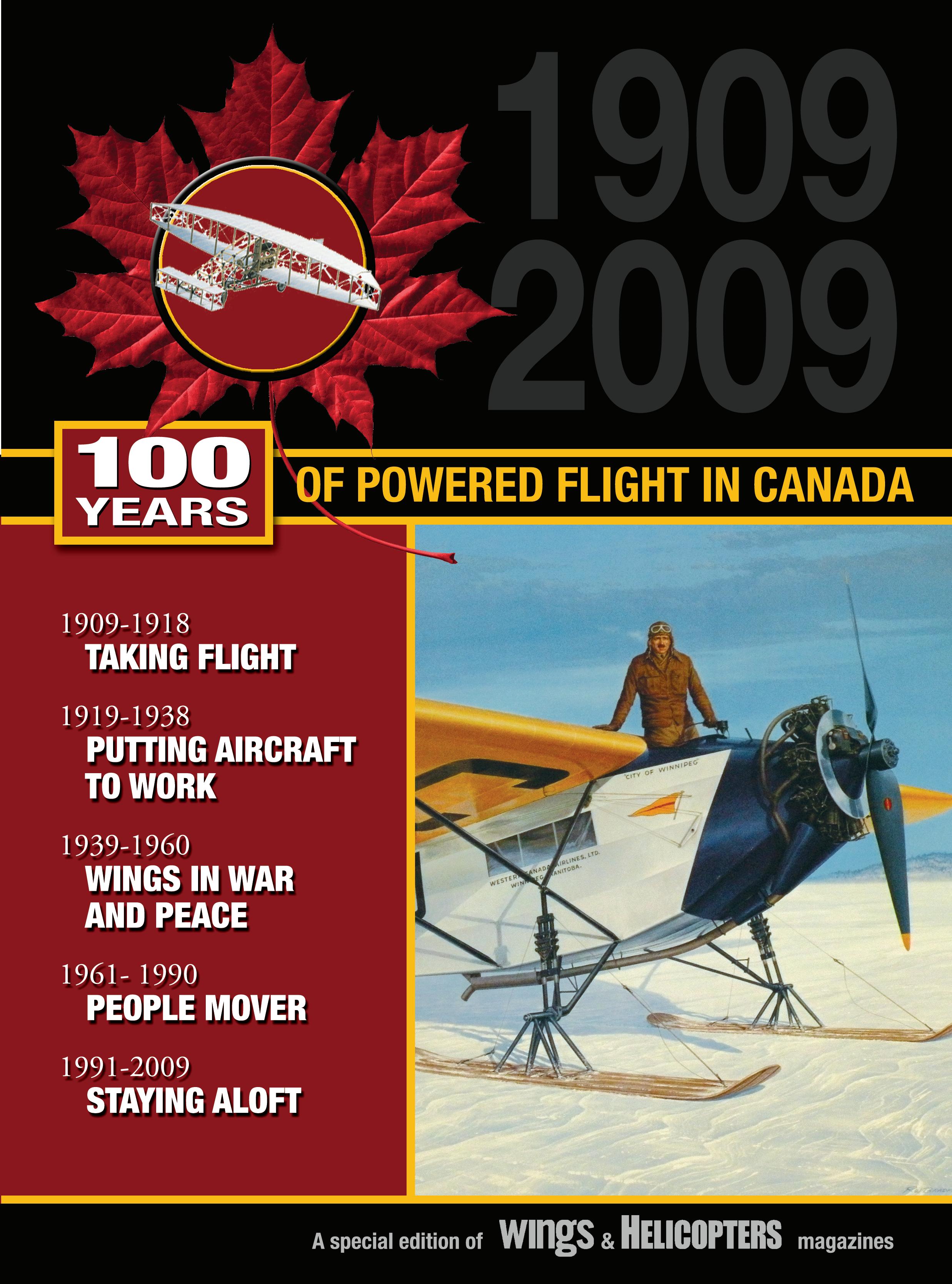

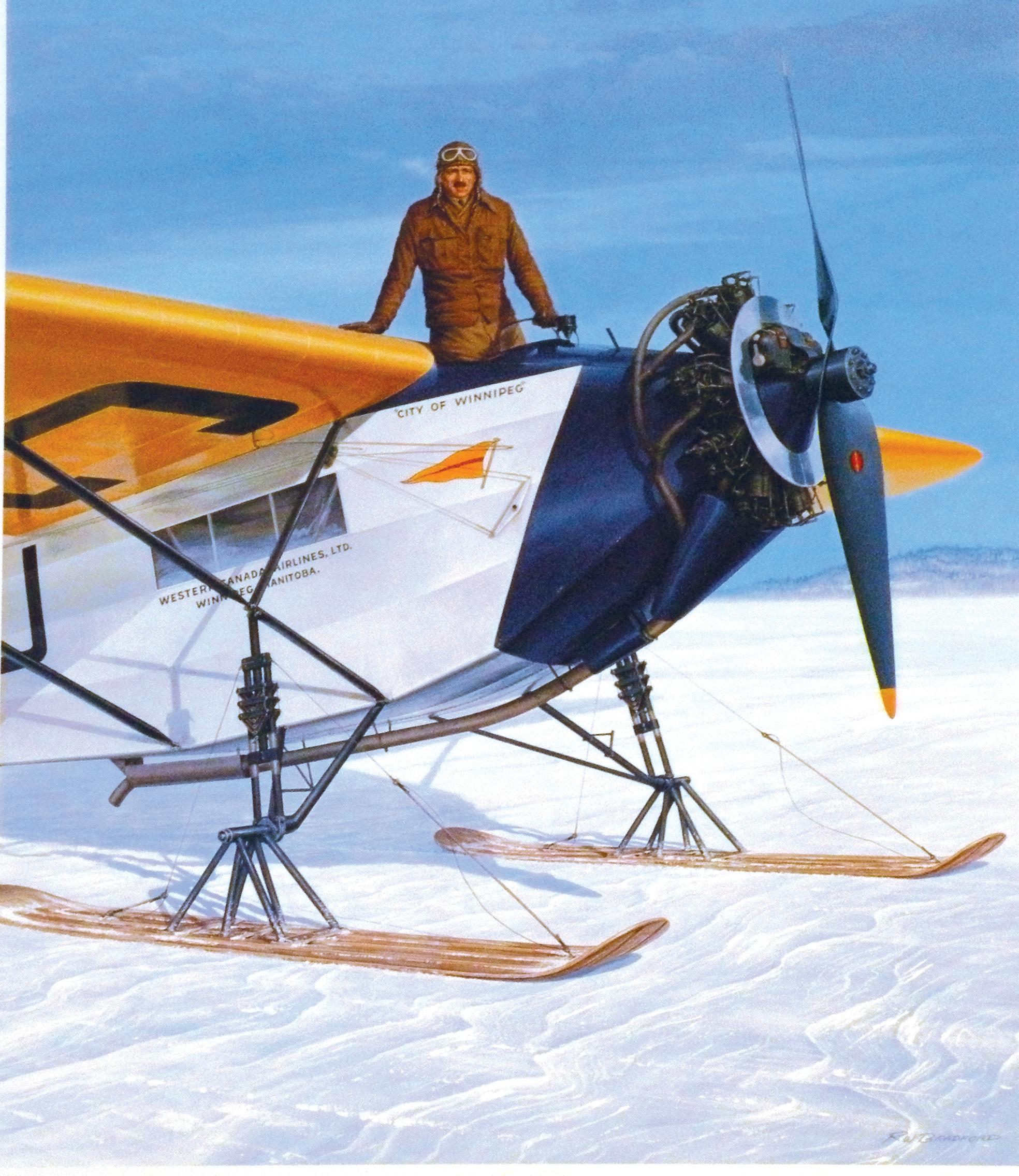

We would like to thank Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame (CAHF) and Robert William Bradford for providing us with a copy of Bradford’s 1980 painting, “Doc Oaks and Friend,” for use on our cover.

Almost 30 years ago, CAHF in association with James Richardson & Sons, Ltd. commissioned Bradford to create, on canvas, a scene depicting Harold Anthony “Doc” Oaks, in commemoration of the birth of Western Canada Airways Ltd. in 1926.

Robert Bradford’s paintings of significant

Canadian aircraft are familiar to any aviation enthusiast. From beginnings as an RCAF pilot in 1943, he has distinguished himself by dedicating his life as aviation artist, historian and curator to preserving Canada’s Aviation heritage. He was instrumental in the development of the Canada Aviation Museum in Ottawa and its building stands as a testament to his great energy, skill, leadership and persistence.

Robert William Bradford was born in Toronto on Dec. 17, 1923. He was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in 1996.

grew. In the end, we also found ourselves reminded of the words of Sir Isaac Newton: “If I have seen further, it is only by standing on the shoulders of giants.” You will recognize many giants in the pages that follow.

Editor

Drew McCarthy; dmccarthy@annexweb.com Associate Editor Andrea Kwasnik; akwasnik@annexweb.com

May 2009

© Annex Publishing and Printing 105 Donly Drive South Simcoe, Ont. Canada N3Y 4N5

www.wingsmagazine.com www.helicoptersmagazine.com

Raymond Canon

an’s attempts to fly can be said to have had a truly noble beginning. The Greek gods thought enough of flight to appoint Hermes as their winged messenger and, in so doing, provided the world’s first air mail service. This action also caught the attention of mere mortals such as Daedalus who, in his efforts to imitate the gods, discovered that there were risks involved, ones that could lead to a dangerous downside.

But man never gave up his desire to fly. Even such a renowned person as Leonardo da Vinci made sketches in the 15th century of what a flying machine should look like. So it went until first the Wright brothers and then Alexander Graham Bell entered the scene. Bell, not being content just to invent the telephone, assembled a notable team of experts at Baddeck, N.S., and, on Feb. 23, 1909, from the windy, frozen waters of Bras D’or Lake, watched his Silver Dart, flown by John McCurdy, take to the air – the first powered flight not only in Canada but in the entire British Empire.

Even Bell’s wife Mabel caught the fever. It was she who, when money was running short, found the finances to support the project to its successful conclusion. Perhaps there should be a plaque attached to the replica of the Silver Dart with the words: “Brought to you through the financial acumen of Ma Bell.”

But Canada was a country ready for the development of flight. The second largest nation on the planet with a small population strung out mainly near the American border, it needed a fast and efficient means of transportation to join the various parts. Having early realized the potential of air travel, cities rushed to establish airports that would form part of a country-wide system and, 30 years after the flight at Baddeck, the first national carrier, Trans Canada Airlines, made its initial flight. Canada was in the aviation business in a big way.

Few were the Canadians who realized just how big. The advent of the Second World War in 1939 saw the rapid expansion of the RCAF in time for a Canadian unit, No. 1 Squadron, to take part in the epic Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. At the same time the epoch-making decision was taken to train aircrew from the entire Commonwealth; out of this came the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

The effect on the Canadian population

can well be imagined. From almost totally empty skies, the air became filled with Tiger-Moths, Ansons, Harvards, Bolingbrokes and many other types of aircraft. By the end of the war, flying was an integral part of the Canadian psyche and so it would remain.

In such planes as the Noorduyn Norseman the country set the standards for flying across rugged landscape. In a few short years the growing aviation industry went from building military aircraft to becoming one the greatest in the post-war world. Two names stood out: de Havilland and Avro Canada. The former designed and built a series of STOL aircraft that set the standard for this segment of the industry, a standard that lasts to this day. One of these creations, the Twin Otter, has recently been put back in production over 40 years after it first flew, with the American military among the first to place an order.

“There is not one segment of the planet, including Antarctica, that has not called on Canada to meet aviation needs.”

It was, nevertheless, Avro Canada that caught the country’s, and subsequently the world’s, attention with its advanced series of aircraft. Cutting its teeth on the CF-100 all-weather fighter, the company went on to create the four-engined Jetliner, a flying saucer and, above all, the Avro Arrow. Reams have been written on this golden age of Canadian aviation but suffice it to say that it demonstrated what the country was capable of achieving. The Canadian government of the day, thinking that all of this flying was, Daedalus-like, too close

to the Canadian aviation sun, in 1959 abruptly put an end to this golden age. But de Havilland persisted and added further STOL aircraft to its stable. Today, as part of the Bombardier consortium, it continues to turn out quality aircraft with worldwide sales.

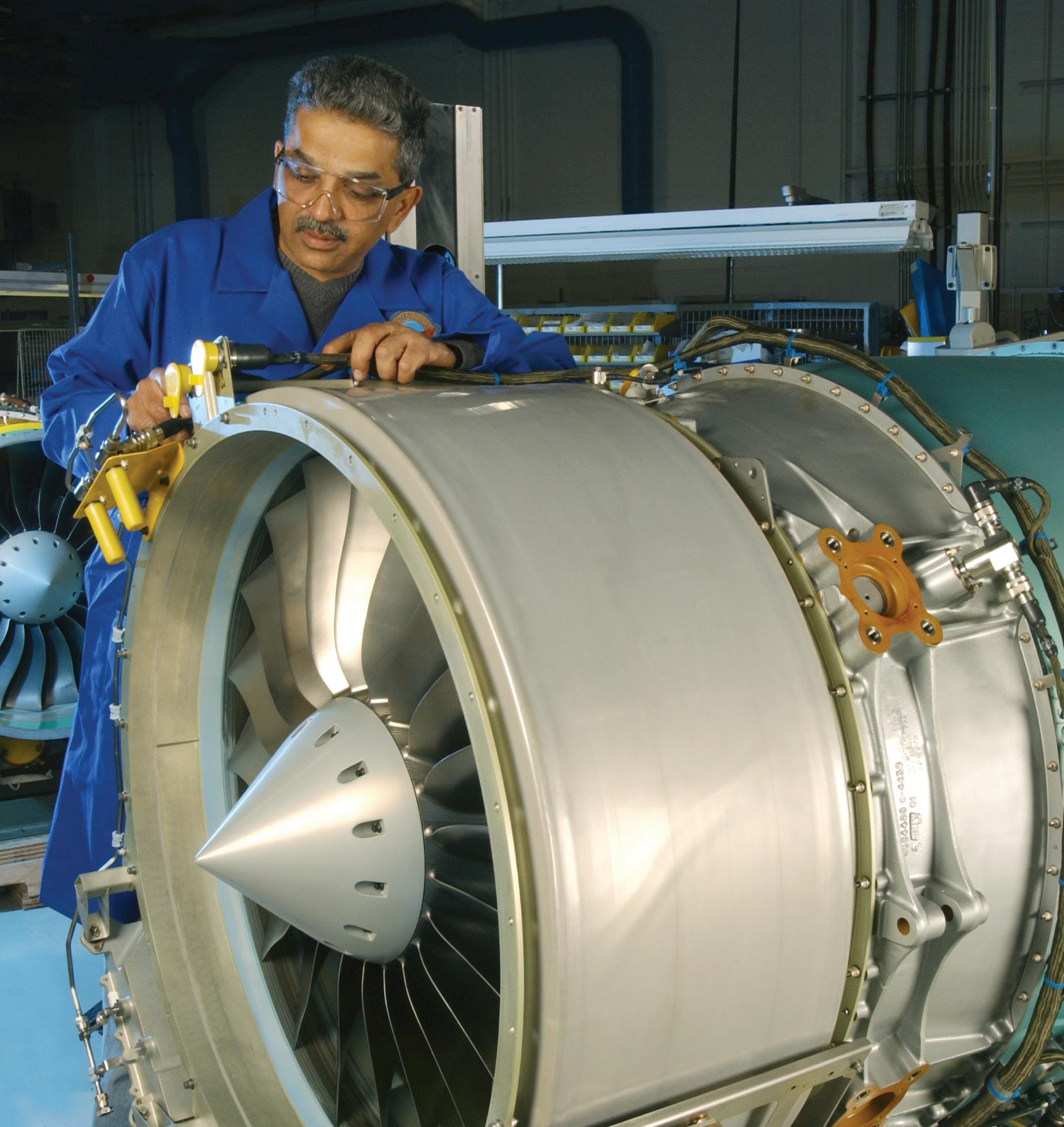

If Canada did not excel in the areas it desired in the 1950s, there were other avenues to explore. Over the last half of the 20th century a service industry has grown up right across the country, developing an excellence along the way that has caught international attention. Aircraft come from all over to be refurbished, rebuilt, repainted, outfitted and modified; all this has illustrated to the aviation world that what goes on in the air is not the only thing that counts. There is not one segment of the planet, including Antarctica, that has not called on Canada to meet aviation needs.

Canada still trains NATO pilots as we have done since the 1950s; other air forces have seen fit to take advantage of this service. In addition, many flying schools across the country now include international students anxious to profit from our expertise as well as improve their English, the common language of the aviation world. Some of these pilots will undoubtedly fly “Made in Canada” aircraft.

In aviation circles we have regained our reputation as a dynamic country and have risen, Phoenix-like, from the (cr)ashes of the Arrow-Jetliner era to create and maintain the third largest aviation industry in existence. This is an accomplishment in which the entire country can take pride; it transcends linguistic borders and a look at our honour roll reads like a phone directory for the United Nations. Our aviation industry is a kaleidoscope of the Canadian mosaic where native-born Canadians work alongside those who have chosen this country as their new home.

At a time when the world has entered one of the steepest recessions in decades, our aircraft industry finds itself in an excellent position to build on its strengths to profit from the eventual expansion. Alexander Graham Bell, his team and wife Mabel would be extremely pleased with what has been created in the aftermath of that historic flight 100 years ago!

Thank you to Connie Constable for her assistance on this project.

My earliest childhood memory is of a Dakota (DC-3) clawing its way into the air over our house. I must have been five years old and my mother remembers that I ran in and tried to pronounce its registration letters” Peter Pigott recalls. “In that instant I was smitten for life.” Peter’s childhood was spent in Mumbai, India, where his father worked for Trans World Airlines. In those halcyon, innocent days, with unlimited passes, he hitched rides in Connies and 707s anywhere in the world, remaining onboard, each crew handing the wide-eyed youngster on to the next.

Peter joined the Department of External Affairs and began writing about aviation when posted to the Canadian Embassy in Hong Kong. Going to Kai Tak Airport to meet the diplomatic courier, he never forgot the thrill of watching giant aircraft thread their way carefully through the surrounding hillside to touch down. When the Kai Tak Airport closed, the Hong Kong government honoured Peter for his book about the airport by flying him back and allowing him to turn off the runway lights for the last time.

Several postings later, on return to Canada, Peter began turning out a book a year. His titles were: Flying Canucks, (1993), Hong Kong Rising (1994), Gateways: Airports of Canada (1995), Flying Colours: A History of Commercial Aviation in Canada (1996), Flying Canucks II (1997), Wingwalkers: The History of Canadian Airlines (1998), National Treasure: The History of Trans-Canada Airlines (1999), Flying Canucks III (2000), Wings Across Canada (2002), Taming the Skies (2003), On Canadian Wings (2004), Royal Transport: An Inside Look at the History of British Royal Travel (2005), Canada In Afghanistan: The War So Far (2007) and Canada In Sudan: War Without Borders (2009).

Now retired from External Affairs, Peter teaches in the Aviation Faculty at Algonquin College, Ottawa. But for two days annually as he helps put on the Classic Air Rallye at Rockliffe Airport, Ottawa, he relives that childhood thrill of watching a Spitfire climb into the sky. Aviation for Peter Pigott is not a matter of life and death. It’s more important than that.

To Fly! It is a universal human aspiration and although the story of Icarus is best known, every civilization can be credited in some way with contributing to the invention of Flight. But for most of us today, the wonder of aviation means delayed flights and overcrowded airports. We tolerate aircraft as mere pressurized buses with wings, forgetting that they whisk us over oceans and continents and do it safely and economically. It is sobering to think that barely a lifetime has passed since the Silver Dart hopped 1.5 kilometre on Feb. 23, 1909, to Air Canada’s daily non-stop Boeing 777 flights from Vancouver to Sydney, Australia, with 340 passengers on board.

The earliest aeronautical observers in Canada must have been the First Nations hunters who saw the aerodynamic designs in birds and crafted their arrows to fly accordingly. European colonists brought to British North America their balloons; the first aerial traveller, Louis Anslem Lauriat ascended above Saint John, N.B., in a hot air balloon on Aug. 10, 1840, to float 21 miles. The most imaginative use of balloons occurred in the high Arctic when, in 1850, Royal Navy ships searched for the delayed Franklin expedition. Stuck in the ice pack, the searchers released hydrogen-filled balloons carrying messages in the hope that Franklin would see them. By the late 19th century, balloons (and parachute jumps from them) were star attractions at exhibitions. But although they provided the first aerial views and photographs of Canada, dependent on the wind, balloons were unreliable and (in Canada) never more than a curiosity. With a lightweight gasoline engine to drive a propeller, they could be controlled, as Lincoln Beachey demonstrated on July 13, 1906, with his dirigible (meaning steer-able) over Montreal. But ballooning wasn’t really flying and it took a young Montrealer, Larry Lesh, in August 1907, to build the first heavier-than-air machine in Canada. Christening it “Montreal 1” he would hangglide six miles over the St. Lawrence for 24

minutes. Significantly, his next machine, “Montreal 2,” used elementary ailerons, or “little wings” – a first in North America.

Then as now aviation was not for the fainthearted or poor and Alexander Graham Bell was neither. Fortunately for Canadian history, the telephone’s inventor summered in Baddeck, N.S., and at 58 years of age was content to leave practical flight to younger men. In September 1907, he invited his secretary’s son John McCurdy and McCurdy’s university friend F.W. “Casey” Baldwin, along with the American motorcycle racer Glenn Curtiss and Lt. Thomas Selfridge, from the U.S. Army, to Baddeck. This band of brothers assembled to in Bell’s words “talk aircraft.” Realizing that she was watching history being made, Mabel Bell suggested to her husband that they form a legal association and offered to finance it. The Aerial Experimental Association (AEA) was born in the Bells’ living room on Oct. 1, 1907, with a simple goal: “to get a man into the air.” In the winter the young men transferred to Curtiss’s workshop at Hammondsport, N.Y., to discuss, design and build a series of aircraft, which were “pushers,” all wing and no body, with the elevators in the front. Selfridge’s Red Wing, Baldwin’s White Wing and Curtiss’s June Bug were evolutionary stages in the search for a stable, controllable aircraft. When Selfridge was ordered home, Baldwin took his Red Wing into the air, becoming on March 12, 1908, the first Canadian to fly.

The fourth AEA craft was McCurdy’s Silver Dart, so called because its rubberized winsook fabric was dyed silver to stand out in photographs for patent protection. Incorporating the lessons of the previous aircraft, its tail section had been shortened to help with turning, it was powered by Curtiss’s latest eight-cylinder, water-cooled, 50-horsepower engine but, most significantly (and safely), lateral control was finally possible through ailerons.

But by the end of 1908 the AEA was breaking up. Curtiss’s fame had grown with every record flight, Baldwin, now married, was lecturing in Toronto, and Selfridge had been killed in a Wright biplane in September –aviation’s first fatality. Worried they were slipping away over Christmas, Bell summoned Curtiss and McCurdy to Baddeck with the Silver Dart. The ice on Bras d’Or Lake was sufficiently firm by Feb. 23 for a flight and the Bells and a crowd of locals, whom McCurdy would recall, “…consisted largely of very doubtful Scotsmen – they didn’t say much, just came to wait and see,” assembled to watch. At about 1 p.m., the craft was wheeled out of the Kite House and McCurdy seated. Confounding his skeptics, the 22-year-old made history, flying for half a mile at 60 feet at about 40 miles per hour, the first such flight in the British Empire. But by spring the Association had ended. McCurdy and Baldwin then formed the Canadian Aerodrome Company, Canada’s first aviation company, in June 1909, to build Baddeck No. 1.

To interest the military, the pair took it with the Silver Dart to Ottawa. The flight trials were held at the Petawawa Army camp

July 13, 1906

Aug. 1907

Mar. 12, 1908

Feb. 23, 1909

J.A.D.

ABOve:

Members

leFT:

William

and in the first instance of Ottawa’s expenditure on aviation, $5 was approved for tar paper in the assembly of the two aircraft. Before the dignitaries on Aug. 2, 1909, McCurdy demonstrated the Silver Dart, taking Baldwin up as an observer – the first time in Canada that an aircraft had carried a passenger. On the fourth flight he hit a grassy knoll and the Silver Dart was written off. Ten days later, he took Baddeck No.1 into the air – the first flight of an aircraft completely designed and built in Canada – but when it too stalled and crashed, the government lost all interest and the two aviators returned home, penniless. They would build a Baddeck No. 2 out of spares for one of Mabel Bell’s wealthy relatives – the first aircraft to be sold in Canada and to be exported. But for the Canadian Aerodrome Company it was too late – the technology had passed them by.

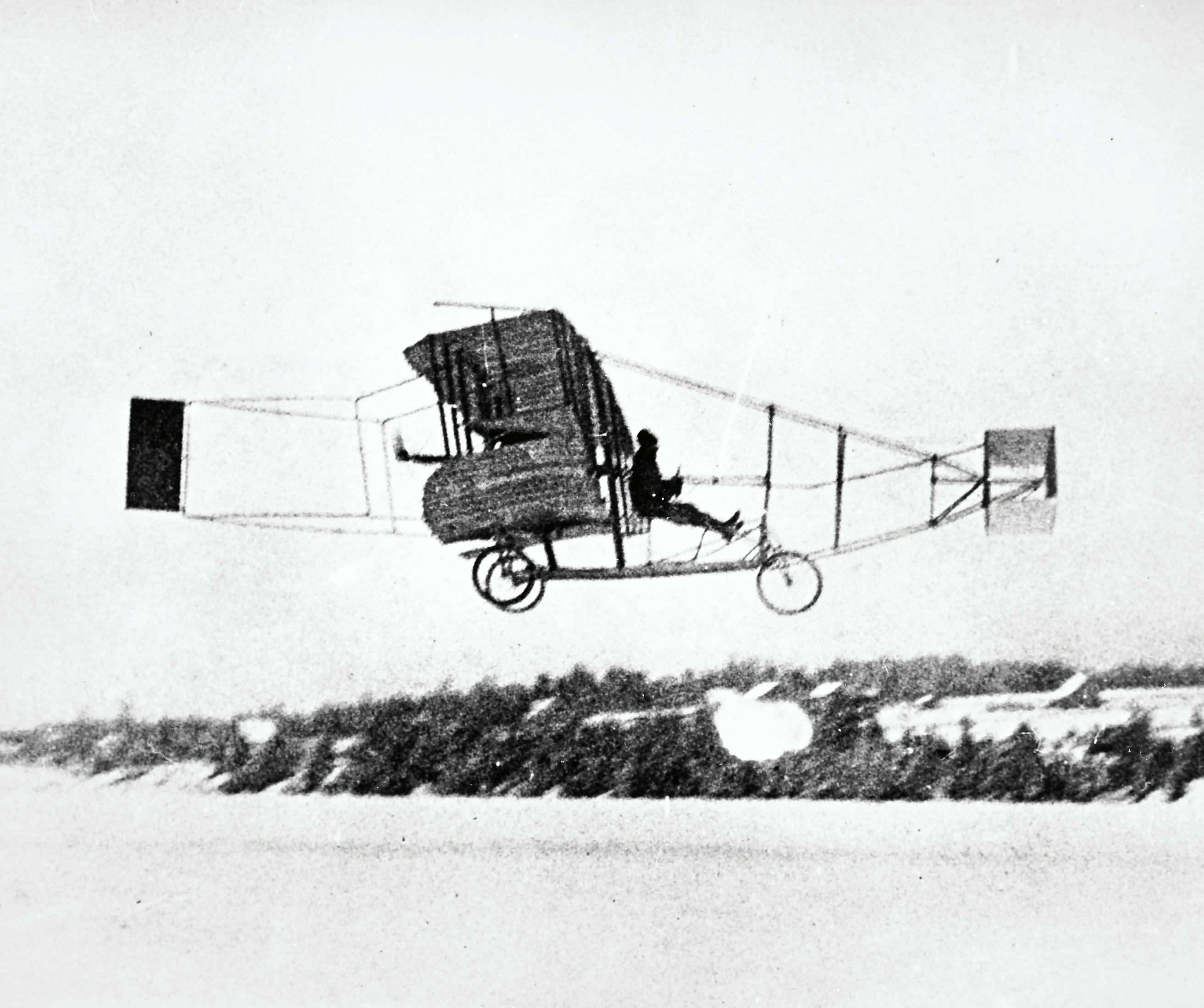

The Silver Dart’s flight, coming with Louis Blériot’s crossing of the English Channel, spurred Canadians from British Columbia to the Maritimes to build and fly their own aircraft. Soon Minoru Park (Vancouver), Hanlan’s Point (Toronto), and Bois Franc polo grounds (Montreal) became the country’s

first airports. From June 25 to July 5, 1910, the first aviation meet in Canada was held at Lakeside, Montreal, featuring Blériot monoplanes, Wright biplanes, dirigibles and balloons. McCurdy would enter Baddeck No.2, but it crashed several times, the day belonging to the Blériots with Jacques de Lesseps circling over Montreal in one, a first for a Canadian city. The Blériot monoplane design had made the Wright and Baddeck biplanes obsolete. High wing, tractor driven, with fully enclosed fuselage and cockpit, stable undercarriage and empennage (tail) to counterbalance the wing and its ailerons, the Blériot would be the dominant model for aircraft to the present day.

Four years later with the declaration of war, Minister for Defence Col. Sam Hughes formed the Canadian Aviation Corps, buying an American-made Burgess-Dunne, and sending both off to England, where they disappeared. Working for Curtiss, McCurdy returned to Canada to set up the Curtiss Aeroplane Company in Toronto with flying schools at Hanlan’s Point and Long Branch and an aircraft plant to mass produce JN-3s. If starting an indigenous industry weren’t enough, he also built the Curtiss Canada, the first twin-engined aircraft designed, built and flown in Canada.

The First World War spurred the development of aviation at an incomprehensible speed. If in 1914 aircraft could barely sustain flight, by 1915 they were far-ranging scouts, and a year later fighters with synchronized machine guns. In 1917, German bombers were dropping 1,000-kilogram bombs on London and in the last year of the war the all-metal, cantilever Junker monoplanes appeared – too late to affect the outcome. On the Western Front the struggle for air superiority raged back and forth, each side developing aircraft with more efficient engines, higher speeds, longer range and better manoeuvrability.

Canadians who wanted to fight for the Empire would join the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), which grew from five aircraft and 22 men in 1914, to 290,000 men and 22,000 aircraft by the war’s end. A third of its pilots were Canadians, some destined to become air aces, achieving celebrity status. The

home front took pride in hearing that Flt. Lt. Arthur Strachan Ince was the first Canadian credited with a “kill,” while Flight Lt. N.A. Magor would sink a U-boat and Flight Lt. Robert Leckie would shoot down a zeppelin. That Capt. W.A. Bishop single-handedly on June 2, 1917, attacked a German airfield, destroying three enemy aircraft proved that Canadian pilots were among the very best. They had to be: combat losses averaged one airman killed for every 92 flight hours, one plane for every 100 sorties. Given the wooden airframes, unprotected cockpits and fuel tanks, absence of parachutes and superiority of the German Fokkers, it is a wonder that any of the RFC pilots survived at all. But through dogged heroism, the “kills” of Canadian aces totalled: Lt.-Col.W.A. Bishop (72), Lt.-Col. R. Collishaw (60), Maj. W.G. Barker (53).

But the meat grinder that was the airspace over the Front was consuming pilots faster than they could be trained and in 1917 the British and Canadian governments inaugurated a large-scale pilot training program at Camp Borden using locally built JN-4 “Canucks.” By the war’s end, the aviation scene in Canada had changed beyond imagining. The first airmail was flown from Montreal to Toronto on June 24, 1918, McCurdy’s former plant was building giant flying boats for export and the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service, and soon after, the Canadian Air Force, was established.

By Peter Pigott

June 25, 1910

The first Canadian aviation meet uses Blériot monoplanes.

1914-1918

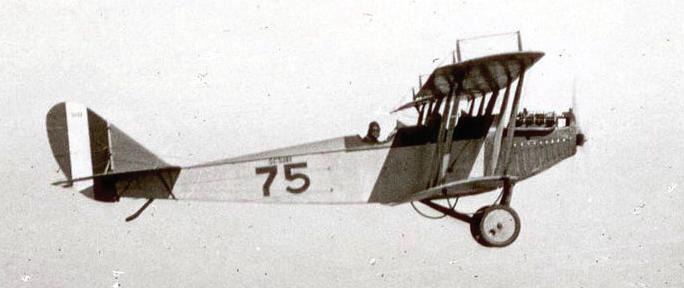

The JN3 was the first twin-engine designed and built in Canada.

Oct. 1, 1907

The Aerial experimental Association is born after Mabel Bell offers to finance it.

When Stuart Graham piloted an HS-2L (later called “La Vigilance”) on June 5, 1919, from Halifax, N.S., to Lac-a-la-Tortue (near Grandmere) Que., covering 645 miles in four days, he set a record not only for the longest flight in Canada to date – but he became history’s first bush pilot.

If ever there was a country made for aviation, it was Canada. Until that day, it had been explored and settled in an almost straight line from east to west – along the St. Lawrence and then, once the railways were hacked through the Shield, to the Rockies and Pacific. Few Canadians lived in the North or far from the coast or rail line –with good reason. Most of the country had barely been surveyed. Governments at any level were hard pressed to tell industries or immigrants just what was out there. Bush flying would change that forever.

Between 1914 and 1918, the War Measures Act prohibited civilian aviation and perhaps this contributed to the aviation frenzy in the decade that followed when ex-RFC pilots worked their way across rural Canada in JN-4 “Canucks,” selling joyrides, barnstorming and “wingwalking.” While it reinforced the idea that aviation was an amusement – and dangerous one at that – the aerial gypsies did give most Canadians their first sight of an aircraft, epitomizing the unregulated, exuberant decade. In contrast, the Curtiss flying boats left by the U.S. Navy in Halifax would be put to more practical use. Pulp and paper companies and the Ontario government would rent them to patrol their vast forests, mining companies to drop prospectors and the federal government for surveying and fisheries patrols.

In Europe governments subsidized their airlines to tie their colonies together and in the United States the Post Office had a coast-to-coast airmail service operating as early as 1918. In contrast, the Canadian government did little. Ottawa was still

“if ever there was a country made for aviation, it was Canada.”

paying for an overbuilt railway network and in 1923 had been forced to merge bankrupt railways into the Canadian National Railway (CNR). As a low cost measure, the Air Board was formed to control all aviation activities, flying clubs were subsidized and the Royal Canadian Air Force put to work as bush pilots in uniform. Using mainly float planes and flying boats, on Oct. 17, 1920, the RCAF completed the first transCanada flight from Halifax to Vancouver, in 49 hours flying time. The abundance of lakes and rivers kept flying boats in use well into the late 1920s, Canadian Vickers even building Vikings and Vedettes for the local market. But lack of business meant that the few brave entrepreneurs like Thomas Hall who started their own air companies quickly went bankrupt.

When James Richardson, the Winnipeg grain merchant, began Western Canada Airways (WCA) on Dec. 10, 1926, he knew that it would be a gamble. But, investing his own fortune, he bought the latest Fokker Universals. In contrast with the HS-2L, the Universal had a welded steel fuselage with a “one piece” plywood wing, a maximum speed of 118 m.p.h. and range of 535 miles. Most important of all was its interchangeable undercarriage of skis, floats or wheels. In the first airlift in history, from March 22 to April 17, 1927, WCA’s pilots made 27 round trips with supplies and men from Cache Lake to the Fort Churchill waterfront.

Contracts with mining and lumber companies followed, allowing Richardson to hire more staff and to buy Fairchild FC-2s, and, in 1928, 14 Super Universals. Built by Canadian Vickers under licence, they had double the power and endurance of their predecessors. Knowing that he could not rely on the “boom and bust” cycles in mining, Richardson lobbied aggressively for mail contracts, securing some until with the Depression they were curtailed along with all investment in mining. As part of an

unemployment relief scheme, the government did initiate the construction of the Trans Canada Airway, building airfields, navigation aids and later radio beacons across the country. The Depression meant that the plight of commercial aviation elicited little sympathy from either the government or public – when compared to the widespread financial devastation all around. In a feat still unknown to most, on Oct. 9, 1930, Errol Boyd became the first Canadian to fly the Atlantic Ocean, using a borrowed Bellanca and, to pay for his fuel, a collection had to be taken up at St. Hubert Airport.

Expanding across the country, Richardson bought air companies on the Pacific coast and St. Lawrence but although WCA employed legendary bush pilots like C.H. “Punch” Dickins to explore as far north as Aklavik, N.W.T., it rarely broke even. As Canada remained one of the few countries without a national air service, Richardson clung to the hope that Ottawa would make his air company, renamed “Canadian

TOP leFT:

Pushing back the Canadianbuilt Jn-4 “Canuck.”

ABOve:

lord hiver (rolls-royce),

rt. hon. C.D. howe, G.W.G. McConachie and G.r. McGregor.

(Photo courtesy of Canada'sAviation hall of Fame/national Archives of Canada C-63278)

leFT:

Trans Canada Air lines

Douglas DC-3 on runway. (Photo courtesy of CanadaAviation Museum)

Airways” in 1930, its official airline to ply the Trans Canada Airway. Other bush pilot outfits – Grant McConachie’s United Air Transport and Leigh Brintnell’s Mackenzie Air Services – were also undercutting Canadian Airways for business. One of the problems all bush companies faced was that given the type of customer they had, it was rarely possible to get paid in cash. Payment in wolf bounties and muskrat fur was more likely than dollars. Hanging on grimly, Richardson concentrated on freighting, buying Junkers all-metal aircraft – the lowwing W-34s and later his most extravagant purchase, the giant single-engined Junkers 52. This last was initially a disappointment and not until its BMW engine was replaced by one from Rolls-Royce, did it earn its nickname “The Flying Boxcar.”

In 1935, William Lyon McKenzie King’s Liberals swept to power and Clarence Decatur Howe was appointed the country’s first minister of transport. The indefatigable Howe was air minded but did not think a private airline was suitable for the Trans Canada Airway. A firm government commitment on commercial aviation was needed –

and soon. Both Imperial Airways and Pan American Airways were manoeuvring to begin air services by flying boat across the Atlantic Ocean and both wanted to set up connecting services in Canada. New York might be the terminal for transoceanic flights but on the Great Circle, Montreal was closer to Europe. London even coerced Ottawa into setting up the Joint Operating Company to construct bases for its flying boats at Shediac, N.B., and Longueuil, Que. Rather than antagonize the Americans, in 1936 King asked Howe to expediently nominate a national airline. Hearing this, to better his chances, Richardson bought two non-bush planes – sleek Lockheed 10A airliners – and put them on the Vancouver-Seattle mail route. Designed to compete with the Boeing 247 and DC-3, the 10A Electra was a twin-engined, stressed skin monoplane, with flaps and retractable undercarriage, that could carry 10 passengers.

But influenced no doubt by Howe, on April 10, 1937, the Liberals approved the creation of Trans Canada Air Lines (TCA). A subsidiary of the CNR, it would initially be run by Americans experienced in the airline business like P.G. Johnson from United Air Lines until Canadians had been trained to take over. It would operate scheduled services, at night, from coast to coast and fly only on the new radio range. But while it would strive to be profitable, TCA’s mission was to bind the country together – to be Ottawa’s “chosen instrument” in the air. At this, several of the Canadian Airways’ employees left to join the government airline. To publicize the air service, Howe would stage an audacious “Dawn to Dusk” flight on July 30, 1937, flying from Montreal to Vancouver within a single day. Bitterly disappointed, Richardson sold the Electras to TCA and returned to bush flying. Acknowledged as the Father of Commercial Aviation in Canada, he would die on June 26, 1939.

The inaugural TCA flight was on the Vancouver-Seattle route on Sept. 1, 1937, using the former Canadian Airways Electras. If the passengers on Imperial Airways had five-course meals and attentive stewards, TCA was not to be left behind. Its aircrew were uniformed and trained to fly on instruments, passengers were served meals

and there was even a toilet on board. But, as the 10As were unpressurized and unable to fly above the weather – making flights stomach-churning experiences – what was needed was a combination of an airborne waitress (to take the coats and serve the meals) and a reassuring female trained as a nurse. She had to be single, between 21 and 26 years old, no taller than 5' 4" (to walk within the 10A cabin), weigh not more than 125 pounds but be strong enough to carry luggage. In June 1938, registered nurses Lucille Garner and Pat Eccleston were the first stewardesses hired by TCA – neither had been to an airport before, let alone flown. Using the stewardess manuals and uniforms from United Air Lines, the pair organized the airline’s cabin crew school and hired the first 15 stewardesses. Amazingly, with just 71 employees strung out across the Airways, on April 1, 1939, three decades after the Silver Dart flight, TCA inaugurated passenger service between Montreal and Vancouver and to Lethbridge and Edmonton.

Between the First and Second World Wars, there were 678 aircraft made in Canada. These were airframes only with engines imported from the United States and Britain. The companies that made them were British subsidiaries (Canadian Vickers and de Havilland) or sidelines of railcar manufacturers (Canadian Car & Foundry, National Steel Car Corporation and Ottawa Car Manufacturing Ltd.) or a few aviation enthusiasts (Reuben Fleet, Robert Noorduyn and W.T. Reid). All that was to change on Sept. 10, 1939, when Canada declared war on Germany.

By Peter Pigott

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan was signed in Ottawa on Dec. 17, 1939, with the first Air Observer School opened at Malton. The schools were to be operated by flying clubs and bush companies and soon students from across the Commonwealth arrived in the thousands to be trained as aircrew. Supplying not only the instructors and airfields but most of the aircraft as well, Canada would become not only the “Aerodrome of Democracy” as President Roosevelt said, but the arsenal as well. Canadian companies would build Hurricanes and later Curtiss Helldivers at Canadian Car & Foundry plant, Fort William, Ont., Lysanders at National Steel Car, Malton, Ont., Hampden bombers at Fairchild Montreal, Norsemen at Noorduyn, Cartierville, Que., Tiger Moths at de Havilland, Downsview, Ont. and Finch trainers at Fleet Aircraft, Fort Erie, Ont. Called the “Minister of Absolutely Everything,” Howe spread the contracts around (like playing cards his enemies said) to build Avro Ansons among several Canadian companies, securing Wasp engines from the United States. Nothing was insurmountable for him or it seemed Canada, and by 1940, 17,000 Canadians were employed building aircraft. A year later, the figure had doubled and by 1942 the workforce totaled 71,000, and with most men in uniform, was increasingly female.

The Battle of Britain was the first time in history that the fate of a nation depended on the country’s air force. In its midst were Canadian pilots S/L E.A. McNab and F/L G.R. McGregor, both awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in October 1940. Desperate for aircraft, the British government placed large orders with American manufacturers but, because of American neutrality, these were delivered only as far as Canadian airports. With the U-boats infesting the Atlantic, the Canadian press baron Lord Beaverbrook considered hav-

“Canada would become not only the ‘Aerodrome of Democracy,’ but the arsenal as well.”

ing them flown over and asked the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) to organize it. The CPR formed ATFERO (Atlantic Ferry Organization) and the first ferry flight of seven Hudson bombers left Gander, Nfld., on Nov. 10, 1940, for Aldergrove, Northern Ireland. Fighting lack of oxygen, icing and airsickness, the fact that those aircrews had initiated the age of mass trans-Atlantic air travel was probably the last thing on their minds. With the ever-increasing volume of American-built aircraft, the Royal Air Force Ferry Command would take over ATFERO in August 1941.

The war was a boon for the faltering Canadian bush companies. The vulnerability of British Columbia and Alaska to air attack and the need to ferry aircraft to the Soviet allies meant that roads, pipelines and airports were hastily built through British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon. The bush outfits were now awarded routes, precious gasoline and scarce aircraft - making them attractive to the CPR, which wanted to get into the airline business like its rival CNR. After running ATFERO, the CPR began buying up bush airlines and when James Richardson’s widow agreed to sell Canadian Airways, on March 24, 1942, the railway merged all of them to form Canadian Pacific Airlines (CPA). The federal government resented this but realized it was essential to the war effort.

By 1942, the RCAF was operating fighter, flying boat and bomber squadrons based mainly in England but also as far away as Alaska, Egypt, India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). As No.6 Bomber Group was Canadian, Ottawa wanted it equipped with Canadian-built Lancasters. The country had never built so advanced an aircraft but, undaunted, Howe nationalized National Steel Car, renamed it Victory Aircraft and, by August 1943, the first Lancaster, christened the “Ruhr Express,” was rolled out. At the same time, Ottawa built a plant at Cartierville for Canadian Vickers to turn

out Canso flying boats. At Downsview, de Havilland “glued and screwed” wooden Mosquito bombers together, the engines built by Massey-Ferguson. At its peak in 1944, 116,000 Canadians were employed in the aviation industry and in that year alone 1,900 combat aircraft were built. But Howe was only beginning...

To deliver mail to the Canadian troops in Europe, he asked the Allies for longrange aircraft. With an eye to the future, they refused – both BOAC (the successor to Imperial Airways) and Pan American were jockeying for position in the postwar world. By 1943, TCA was already too stretched to consider flying the Atlantic35 per cent of its staff were female and the airline with new Lockheed Lodestars was now serving New York, Newfoundland and Victoria. But TCA pilots like George Lothian and Lindsay Rood had been flying the Liberators that brought the Ferry Command pilots back to Canada and had even trained the RCAF aircrews when 10 Squadron got the bombers. All that was needed was the right aircraft. The pattern Lancaster that Avro had sent over for

TOP leFT:

Avro Anson, BCATP.

(Photo courtesy of DnDArchives)

ABOve:

Women assembling aircraft cables, Canadian Car & Foundry Co., 1945. (Photo courtesy of theArchives of Ontario)

leFT:

rCAF pilots in Britain racing to their hurricanes.

(Photo courtesy of DnDArchives)

Victory Aircraft was available - it had been ferrying supplies to the new airport at Goose Bay. Howe commandeered it and the Canadian Government Trans Atlantic Ferry Service (CGTAS) was born in July 1943. The minister then ordered Victory Aircraft to convert eight of its Lancaster bombers into passenger aircraft immediately. The nose turrets were removed, and soundproofing and seating for 10 passengers were added. Run by TCA personnel and dubbed “Lancastrians,” they flew thrice weekly to Prestwick. CGTAS was a temporary solution but gave TCA experience.

In November 1944 Howe attended the Chicago Conference on international aviation and secured for Canada the worldwide approval that Montreal was to be the headquarters for the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Air Transport Association (IATA). By the war’s end, Canada had built 16,415 aircraft, hundreds of new airfields dotted the country and through the Air Training plan had trained 131,553 aircrew, of which 80 per cent were Canadian. The British company A.V. Roe bought Victory Aircraft in 1946

renaming it Avro Canada and Electric Boat Co. bought Canadian Vickers, renaming it Canadair. The Second World War had jump-started aviation and the country was on the threshold of a new era.

The new president of CPA, the flamboyant bush pilot Grant McConachie moved his airline from Montreal to Vancouver, looking to fly to the Pacific and China. Like Howe and the RCAF, he needed an appropriate long-range transport but there was none available. At Howe’s instigation, Canadair bought a complete Douglas C-54 plant in Illinois and had it shipped to Cartierville. Assembled and named North Stars, the country’s first airliners were DC-4s powered by Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. Designed for Spitfires and Lancasters and not for commercial use, the Merlins were noisy, smoky and unreliable. But Canadair pressed ahead and built 71 North Stars, hoping to export them. Howe managed to sell 22 to BOAC and rumours have persisted that the British gave Canada its colony of Newfoundland as part of the deal. With its North Stars TCA expanded to London, Paris and the Caribbean, its new president the air ace Gordon McGregor struggling to keep the Crown Corporation out of deficit.

The two airline presidents, McGregor and McConachie would dominate commercial aviation in Canada for the next two decades. They had more than their Scottish ancestry in common. Both were experienced pilots – the last of their profession to run major airlines in Canada – McConachie had begun hauling frozen fish and McGregor had been awarded the Webster trophy as best amateur pilot. Eight years older than McConachie, Gordon McGregor was his apotheosis. McConachie had kept his bush companies aloft through sheer charm and would continue to do so with CPA. But the TCA president thrived in the security of large organizations, beginning his working life in Bell Telephone before joining the RCAF. At a time when jet aircraft were closer to science fiction than commercial use, in 1952, McConachie convinced the CPR to buy two of the first jet airliners – de Havilland Comets – only cancelling the order when one crashed at Karachi, Pakistan, attempting to set a speed record. Hoping that he would overreach himself and go bankrupt,

Howe allowed McConachie to fly to the Far East and Australia. But thanks to the Korean War and immigration from Hong Kong, CPA prospered on those routes and McConachie began to agitate for permission to cross Canada and link Vancouver with Toronto and Montreal.

By 1954, with the North Stars nearing the end of their lives, Avro Canada hoped to sell its Jetliner to TCA and the RCAF. Ahead of its time, the Jetliner depended on two British jet engines – and when the British government suddenly made them unavailable was forced to use four smaller, older engines. This increased its weight and limited the range. The RCAF opted to buy the de Havilland Comet instead and, cautious with the taxpayers’ dollars, McGregor would have nothing to do with the Jetliner. He selected Vickers Viscounts to replace the DC-3s and Lockheed Constellations the North Stars. The tried and true Constellations were already in use on the Atlantic by other airlines but the Viscounts were unknown to North Americans. Vibrationless, the little turboprop airliners had great passenger appeal. Accused of being an Anglophile for not buying Canadian aircraft, McGregor was enough of a pilot to recognize a superior aircraft – but, after the Merlin problems, secured a free maintenance warranty from Rolls-Royce for the Viscount’s engines. In 1949, having assembled the last of the North Stars, Canadair was licensed to build the RCAF’s jet fighter for its NATO squadrons. The superb Canadair Sabres made the RCAF pilots in Europe for a while the undisputed kings of the air. The air force retired the last Sabre in 1969 – and for a whole generation of aviation enthusiasts there was never a more beautiful aircraft. At Malton, Avro’s gas turbine division had just designed the first Canadian gas turbine engine for the CF-100 “Canuck,” the country’s first indigenous jet fighter, which flew on Oct. 17, 1951.

Impressed, the RCAF then asked Avro to design a supersonic fighter for its NORAD requirements. It had to be supersonic, twin engined, have a range of 6,000 miles, be capable of Mach 1.5 and have its missiles capable of being stored in an internal bay. Nothing less would do for the CF-105 called the “Arrow.” That Avro was able to design and build the Arrow while it was still modifying the CF-100 and Jetliner

remains beyond comprehension. Its rollout on Oct. 5, 1957, was witnessed by J.A.D. McCurdy and when the Arrow broke the sound barrier, it was the most important event in Canadian aviation history since the Silver Dart’s flight. In hindsight, the Arrow was too expensive for any one country to build without securing export orders and when the Conservatives came to power, Prime Minister Diefenbaker cancelled further production. Ironically, the Cabinet decision was taken on Feb. 23, 1959, as a reproduction of the Silver Dart was lifting off the ice at Baddeck. Fearing that the technology in the six prototypes would fall into the wrong hands, the RCAF ordered them scrapped. Howe had been voted out of office by then, ending an era in Canadian aviation.

More resilient were the innovations taking place at Downsview where, under Phil Garratt, de Havilland had broken away from its parent to build a series of unique aircraft. If the nimble Chipmunk were not enough, in 1951 the company turned out a family of the best Short Take Off and Landing (STOL) aircraft in the world. Beginning with the high-wing, all metal Beaver, the quintessential bush plane (pilots called it the Swiss Army knife of aircraft – it could do anything) , Garratt followed with the Otter, the Twin Otter, the Buffalo and the Caribou. The United States military increasingly involved in fighting a war in Vietnam bought the Canadian STOL aircraft as did several of the Third World air forces.

It was the mundane airlifting of supplies for the building of the Distant Early Warning Line and not the Comet that made CPA wealthy – and ambitious. Its North Stars were replaced with DC-6Bs for routes to Lima, Mexico City, Buenos Aries and Santiago. When Ottawa prevented it from flying into London, in 1955, CPA began “Over the Pole” flights from Vancouver to Amsterdam and Lisbon. On its British Columbia routes the airline used war surplus Cansos - one of which in RCAF service had sunk a German submarine – and replaced them in 1952 with Convair 240s. The tubby little airliner had come about when American Airlines was looking for a replacement of its DC-3s and Convair designed a 40-passenger Model 240 in 1945. Not as glamorous as TCA’s Viscounts, the Convair 240s gave good service until the

Boeing 737s appeared.

CPA’s letterhead proclaimed it to be “Wings of the World’s Greatest Travel System” but in reality the airline was as fragmented as Canadian Airways had been. It flew to Sydney, Santiago and Hong Kong but within Canada its network ended at Sioux Lookout, Ont., and began again at Montreal with the Quebec City-North Shore runs. To travel between Vancouver and Montreal, even CPA crews had to fly TCA. It was obvious to McConachie that as long as the government airline had the monopoly on transcontinental flights, CPA would never prosper. All it was doing was feeding customers from overseas to TCA at Vancouver.

The TCA monopoly was breached in 1957 when the Conservatives were elected.

Stephen Wheatcroft, a British economist, was hired to study the Canadian aviation market and he concluded that some competition was necessary. The Diefenbaker government not only gave BOAC landing rights into Toronto but allowed CPA a single daily flight, Vancouver-WinnipegToronto-Montreal. Elated, McConachie bought six turboprop Bristol Brittanias. Nicknamed “The Brutes,” they were magnificent anachronisms: sturdy, quiet and fast but beset (like British sports cars) with electrical problems. But, by 1958, both TCA and CPA had their eyes on the new jet airliners that were about to fly.

After concentrating on swept wing bombers, Boeing re-entered the commercial market in 1953.

Juan Trippe, the president of Pan American, fearing the return of the BOAC Comets, thought that the Boeing KC-135 tanker used by Strategic Air Command could be “civilianized” and ordered 20. Boeing was happy to comply and the first 707 Dash 80 was rolled out on May 14, 1954. If a single aircraft could be said to have launched the Jet Age and changed the face of air travel, it was

the 707. By the time production of the 707 ended in 1991, Boeing had made 1,010, gaining great prestige when the model was selected to be “Airforce One.”

Two of the few airlines that did not buy 707s were TCA and CPA, both opting for Douglas DC-8s instead. Unlike Boeing, Donald Douglas had to design his first jet aircraft from the ground up and scrambled to get financing. But by offering the DC-8 in domestic and intercontinental versions simultaneously, he was able to convince many airlines to sign on. The first DC-8 flew on May 30, 1958, and, as Douglas had stretched the DC-6 into the DC-7, so he stretched the DC-8s - something that Boeing could not do with the 707. The TCA and CPA DC-8s had Rolls-Royce Conway engines, which were quieter, more economical and increased their range.

Having lost its cross Canada monopoly, for TCA the Tory years were bad ones. The airline was now the 6th largest in the world, having grown from 5,512 employees in 1950 to 11,284 in 1960. On Sept. 25, 1960, TCA took delivery of its first DC-8 — and with its Viscounts and Vanguards, now had an all-turbine fleet. One of the new DC-8’s visitors was Canada’s first pilot, J.A.D. McCurdy. He would die on June 25, 1961, having lived to see his country enter the Jet Age.

By Peter Pigott

“Canada would become not only the ‘Aerodrome of Democracy,’ but the arsenal as well.”

1961-1990

When President John F. Kennedy arrived in Ottawa on May 16, 1961, he stepped off an Air Force One Boeing 707, both man and machine symbolizing a revolution in politics and flight that reverberates to this day.

The 1960s were years of great optimism in aviation technology. With their Constellations and DC-7s, the airlines had been pushing the limits of noisy, unreliable, turbo-compound piston engines. Now with the 707s and DC-8s, they could fly above the weather, no longer burning expensive, dangerous, high-octane fuel but cheaper, safer jet fuel. If that weren’t enough, in 1962, the British and French signed an agreement to develop a supersonic airliner called the Concorde. Boeing and Lockheed also designed SSTs (supersonic transports) but Congress killed their projects in 1973. Through the next decades, the speed and size of the new jets soared as Boeing would launch its 747, McDonnell Douglas the DC-10-10 and Lockheed the Tristar. While the 707’s size meant intercontinental travel was restricted to a glamorous few – the jet set – the new wide-bodied airliners would give wings to the common man. With 300plus seats to fill in each of their new “jumbo jets,” through a variety of schemes, airlines brought fares within reach of all. As farreaching was the advent of the Semi Automatic Business Research Environment (SABRE) in 1964. First developed for NORAD, the use of computer systems to run the airlines’ reservations revolutionized the industry, with Apollo, Galileo and Gemini following soon after. It was all just in time for an industry that since the 1930s had catered to a pampered elite and now was coping with mass transit. Although the SST never flew (both Air Canada and CPA placed orders), it did affect aircraft design profoundly. Pan American’s Juan Trippe was so convinced the future for passengers belonged to supersonic transports that he insisted Boeing design its 747 as a freighter – its interior the width of two containers and a nose door for straight-in loading. The result was an upper

deck cockpit that had to be extended into an aft fairing (to reduce drag) and became large enough to accommodate a passenger cabin. In Canada, the decade began badly for both TCA and CPA. The last of the North Stars had been sold off in 1961 and the last DC-3 and Constellation in 1963. In fleet size and routes, TCA was now the 8th largest in the world and Canadian Pacific the 25th. But the two Canadian airlines were suffering from acute “jet indigestion,” an illness that afflicted airlines worldwide as the purchase of jet fleets almost bankrupted them. Because they had to borrow extensively to do so or allow themselves to be bought by banks or hotel chains, it was at this time that control of most airlines moved out of the hands of their pilot founders and into those of lawyers and the “bean counters.” Gordon McGregor lobbied for TCA and CPA to be merged into a single airline, arguing that the rationalization in routes and equipment made economic sense. Lester Pearson’s Liberal government agreed but McConachie argued that the Canadian public should have a choice, and that the only countries with a single airline were in the Third World or Soviet empire.

A symptom of the swinging sixties, both airlines underwent an image makeover. TCA had been using the name “Air Canada” on its timetables as early as 1960 – but now with its overseas routes, “Trans Canada Air

Lines” was no longer valid and neither did it translate into French. At the insistence of Jean Chretien, then a young Liberal backbencher, on Jan. 1, 1965, it was officially changed to reflect the airline’s international status and its maple leaf logo stylized. Selling off its oceanliners and passenger trains, the CPR also underwent a facelift. Heralded by the slogan “Orange is Beautiful,” CPA was renamed “CP Air,” the Canada goose logo replaced with the “Multimark” triangle and all aircraft painted a bright orange. Grant McConachie did not live to see this. The consummate dreamer and gambler died on June 29, 1965, his death making commercial aviation in Canada a more prosaic place.

Setting aviation policy for decades, in 1967, Jack Pickersgill, the Minister of Transport, brought in the National Transportation Act. Responsibility for the airlines now passed to the Canadian Transportation Commission. The Air Canada monopoly was weakened and for the first time in Canadian history competition among rail, road and air carriers officially sanctioned. The world was divided up between CP Air and Air Canada and the status quo of one public, one private, airline was acknowledged. Feeder airlines like Pacific Western, Nordair and Eastern Provincial were to be encouraged – as long as they did not interfere

“The

were

with Air Canada’s or CP Air’s routes. With many of the original TCA staffing in 1968, Gordon McGregor retired. Although he had groomed Vice President Herb Seagrim to be his successor, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau appointed Yves Pratte instead. That the Quebec lawyer had no airline experience was thought an advantage. Canada’s national airline, it was felt, was overstaffed, inefficient, sexist and unilingual. Pratte’s inexperience, the vast sums spent on the new jet aircraft and the first mainframe computers – all plunged Air Canada into annual deficits. Wages were frozen and morale plummeted and the airline suffered its first strike in April 1969.

Bradley Air Services, Kamloops Air Services, Matane Air Services, Mont Laurier Aviation: away from the main air routes these bush outfits still supplied the mines, lumber camps, DEW line and tourist lodges. Many of these were still run by their pilot founders using war surplus aircraft like Ansons but none was more picturesque than the Stranraer flying boats with which Jim Spilsbury began Queen Charlotte Airlines. The Jet Age had also made piston-engined airliners surplus and combined with the growth of the leisure industry, some of the bush outfits graduated to overseas charters. Russ Baker sold off Pacific Western’s Beavers and bought 707s to fly vacationers south, as did Max Ward, who had begun Wardair with a single Fox Moth in 1947. To maintain air services in sparsely populated areas, governments both provincial and federal, bought up regional airlines, with Alberta buying Pacific Western and moving it to Calgary, Quebec buying Quebecair and Ottawa (through Air Canada) buying Nordair.

As the turboprop Viscounts and Electras reached the end of their service lives, aircraft manufacturers in Europe and the United States diversified into building short-haul jet airliners. With cities closer together, the Europeans led the way with Sud Aviation flying its Caravelle as early as 1955. The British caught up with the Hawker Siddley Trident and BAC 1-11 and by 1968 Douglas and Boeing were selling their DC-9, 737 and 727. This last had been developed as a medium range tr-jet for Eastern Airlines to get in and out of New York’s La Guardia and Washington’s National airports. It climbed quickly and came down (as Boeing ads claimed) “like a helicopter.” Both Air Canada and CP Air would buy 727s for their transcontinen-

tal routes but as none of the Canadian cities they serviced were from downtown airports, they proved uneconomical and were soon sold off. More successful was Boeing’s 737 twin jet. For airlines that already flew 707s and had commonality in galleys and seats, Boeing adapted the 707 fuselage to allow for six-abreast seating and fitted in 100 (later 130) seats – the 737 “Classic” going through several reincarnations – outliving its rival DC-9, which itself would remain in production until 2006. The workhorse of Eastern Provincial Airlines, CP Air and later WestJet, the 737 was destined to be the most widely used jet airliner in the world. To compete in the inter-urban, high density market, Air Canada took delivery of its first DC-9-14 in April 1966, using the series until 2002 when the last one was flown to the Canada Aviation Museum, Ottawa.

The 1960s were still busy years for Canadair as it licence-built fighters, trainers, drones and maritime patrol and transport aircraft for the military market. The company’s only original design was the experimental VTOL CL-84 “Convertiplane.” Able to fly like an aircraft but land like a helicopter by tilting its wing upward, sadly, the CL-84 like the Avro Jetliner found no customers. More successful was Canadair’s adaptation of the Bristol Britannia to build the Argus – considered the best anti-submarine reconnaissance aircraft of its time. Instead of the troublesome Proteus engines, Wright 3350 piston engines were substituted for better fuel consumption at low altitudes. The largest aircraft built in Canada, the Argus would serve in the Canadian Forces from 1957 to 1981. Less well known was its derivative, the CL-44 Yukon passenger and freight aircraft. The RCAF specified that it had to have Rolls-Royce Tyne turboprop engines, which caused delays. But when it eventually did fly, the Yukon was able to carry 189 passengers, had a better range and fuel economy than the Boeing 707 and set world records for endurance. Although Canadair did stretch the fuselage for its CL-44D version and produced the ingenious “swing tail” for easy loading, with the Jet Age, it never went into mass production. Uniquely Canadian was the company’s other design – the CL-215 water bomber. Quebec forestry officials wanted a floatplane that could fight forest fires more

effectively than their postwar Cansos and this evolved into an amphibian configuration with a pair of shoulder-mounted Pratt & Whitney R-2800 piston engines. The distinctive yellow “water scooper “ made its maiden flight on Oct. 23, 1967, the year of the country’s 100th birthday – a descendant of Stuart Graham’s flying boat that had begun forestry protection almost half a century before. Less successful was the program to build the Northrop F-5, a fighter aircraft without a clear role. Debuting too in the 1960s was the Canadair CL-41, the lowwing monoplane with the distinctive T-type tail still familiar 50 years later (and much loved by millions of Canadians) as part of the “Snowbirds” aerobatic team.

With the exception of Pan American’s Sikorsky service from Manhattan, the postwar dream of passenger helicopters rising off downtown buildings never caught on. But it did give impetus to the commuter airlines and in 1965, de Havilland would launch the world’s first truly significant, cost-effective family of commuter Short Take Off and Landing (STOL) airliners, the DHC6 Twin Otter, Dash 7 and Dash 8. But the

“The

STOL market never developed in Canada and the Dash 7 airliner, like the SST, while a technical success was an economic failure. With de Havilland, Canadair was close to bankruptcy – its military market no longer viable. The federal government was concerned not only because both manufacturers were in politically important cities but as with the demise of the Avro Arrow, Canadian aeronautical talent would be lost to the United States. To forestall this, in 1974, Ottawa took control of de Havilland and

In

Debuting

then sold it to Boeing. Ottawa then poured $60 million in loans into Canadair so that it could buy the rights to build William P. Lear’s Learstar 600. Renamed the Challenger 600, the first executive jet was rolled out on May 25, 1978. Then, with Ottawa’s encouragement, the transportation giant Bombardier purchased Canadair in 1986 and de Havilland from Boeing in 1992. Under Bombardier, the Challenger 600 would be the first of a successful line of executive and regional jets.

With the oil crisis, a spate of hijackings and a recession, the 1970s were difficult years for both Air Canada and CP Air. On the surface, the size of the government airline would have made C.D. Howe proud. It had 17,447 employees, 38 DC-8s, 36 DC9s, 12 Vanguards and 31 Viscounts and flew from Los Angeles to Moscow. The first of three 747s was accepted in 1971 and all Air Canada passenger agents were now adept at using the second-generation Reservec computers. But the Crown corporation’s deficits had become an annual occurrence and its disregard for passengers was legend-

ary. Abandoning its appointee, the Trudeau government created a Royal Commission to study the airline and Pratte resigned on Nov. 28, 1975. He was succeeded by the airline’s director of public relations, the popular and outgoing Claude Taylor.

The new Minister of Transport, Otto Lange, wanted to see the airline regain its profitability – before he put it up for sale. In 1977, he guided the Air Canada Act through Parliament and cut the airline’s ties with the CNR, and the race to privatize it was on. When President Jimmy Carter deregulated the airlines in the United States in 1978, Canadians waited to see if their own were to be thrown into a free-for-all marketplace of competition. But when Prime Minister Brian Mulroney came to power in 1985, he vowed that Air Canada, “our national birthright,” was not for sale. His Minister of Transport, Don Mazankowski thought otherwise. His predecessors like Pickersgill and Lang had been academics but “Maz” was more in the mould of C.D. Howe than mandarin. The former car dealer knew that Air Canada desperately needed $3 billion to buy fuelefficient, hush-kitted Airbuses and he wanted the Crown corporation privatized.

For CP Air, the 1980s should have been a decade of expansion and fiscal harmony. Ottawa had eliminated all restrictions on the transcontinental market in 1979 and it also broke into Air Canada’s territory in Europe. But itstill had no domestic network – and its Vancouver hub was too isolated. To remedy the first, in 1982, its president Daniel Colussy began buying up regional airlines like Nordair, Quebecair and Air Atlantic and moving more of his company’s operations to Toronto. But Ottawa was now boosting Wardair as Canada’s third airline, giving it scheduled flights between major Canadian cities and on to London. With Wardair siphoning off customers, Colussy and his successor Don Carty (who would revert the airline’s name to “Canadian Pacific”), focused on business executives with “Attache Class,” using the Boeing 737 fleet. In 1986, not unexpectedly, the CPR put its airline up for sale and in a move that would have been inexplicable to Grant McConachie on Dec. 2, 1986, Pacific Western’s dynamic president Rhys Eyton purchased Canadian Pacific for

$300 million. Eyton also saw that the financially troubled Wardair was in the throes of learning a bitter lesson: that 90 per cent of the domestic market was controlled by Air Canada and Canadian Pacific and that it had no connecting flights. On Jan. 19, 1989, with his airline hemorrhaging millions of dollars daily, Max Ward sold it to Eyton. But he had bitten off more than he could chew as coping with disparate corporate cultures proved to be Canadian Pacific’s undoing.

In Britain, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher privatized British Airways, even as upstarts like Freddie Laker and Richard Branson were giving it a run for its money –and Mazankowski knew his time had come. On Aug. 28, 1987, the National Transportation Act was given Royal Assent, deregulating the industry completely, and the Canadian Transport Commission was replaced by the National Transportation Agency. As deputy prime minister in April 1988, “Maz” also orchestrated the Air Canada Public Participation Act in two waves – allowing it to re-equip with the latest aircraft and to pay off its debt. To ally the fears of the Opposition, no more than 25 per cent of the company’s shares could be owned by nonresidents, the airline’s headquarters would always be in Montreal and the Official Languages Act would be enforced.

The 1990s ended with the skies over Canada becoming a battleground as Air Canada and Canadian Airlines (it dropped “Pacific”) attempted to clobber each other into bankruptcy, the next decade promising to be a duel to the finish.

By Peter Pigott

The last decade of the 20th century began well for Canadian aviation.

Deregulation had proved a boon for Air Canada, Bombardier’s success with regional and executive jets held great promise, and even Canadian Airlines – that perennial Oliver Twist of the industry – was making a small profit. But in retrospect, the two Gulf Wars that began the 1990s were an omen of what was to come.

The oil spike caused by the invasion of Kuwait created a sharp economic recession as the price of jet fuel climbed. Travellers were too frightened to fly, leaving airlines crippled with exorbitant fuel prices and empty planes. Both Air Canada and Canadian Airlines grounded aircraft and cancelled flights. Ironically, the latter’s immediate future looked promising: although burdened with a heavy debt load, it had taken delivery of three 747-400s, improved its share of the domestic market (moving up from 30 per cent in 1988 to 45 per cent in 1992) and the flow of red ink had been staunched – its unit costs were 14.6 cents per available seat mile (ASM) as compared with Air Canada’s 18.2 cents per ASM. But that was the last of Canadian’s victories.

When Air Canada’s new president, Hollis Harris, was hired in 1992 he was told that putting Canadian Airlines out of business was a priority. He made Air Canada a founding member of the Star Alliance and proposed a merger with Canadian –but only if the federal government would absorb the airline’s debt load. Instead, Canadian’s new president, Kevin Jenkins, went to American Airlines (AMR) for an infusion of cash. In return AMR was given equity interest and use of Canadian’s Vancouver hub. It also meant that Canadian would have to code share with the One World airline alliance that AMR was part of and drop its Gemini reservations system for AMR’s Sabre – a move that cost the airline dearly when Gemini sued. Aware of the lack of airline competition (to say nothing of the loss of jobs in the West) if

Canadian died, in 1994, Ottawa, Alberta and British Columbia gave it loan guarantees of $120 million.

On Feb. 25, 1995, when President Bill Clinton and Prime Minister Jean Chrétien signed the “Open Skies” agreement to deregulate air travel in North America, it should have been a win-win situation for both Air Canada and Canadian Airlines. Airlines from Canada now had the right to immediately fly into any U.S. city, while U.S. airlines would get access to Canadian airports over the next three years. Harris took full advantage of “Open Skies” by giving Air Canada a makeover, phasing out the old 747s and deploying the new fuelefficient, 50-seat Canadair Regional Jets (called “hub busters”). With their range and speed, the CRJs didn’t have to decant passengers at hubs but could directly link up cities on “thin” routes.

Unfortunately Canadian Airlines was not positioned to take advantage of “Open Skies.” Air Canada had beaten it to the best U.S. airport slots and its aged fleet was no match for the CRJs. Although its 16,700 employees valiantly took repeated pay cuts and bought equity stakes in their employer, much of their airline’s woes were beyond its control – the strength of the U.S. dollar, rising interest rates and a weak Japanese yen. Not unexpectedly, by February 1996, Harris would announce a profit of $129 million while Canadian lost $194.7 million.

Historically, to gain a foothold in the airline industry is almost impossible and the Canadian aviation scene is littered with the wrecks of failed airlines – City Express (1991), Intair (1992), Nationair (1993), Air Astoria (1995), Vistajet (1997), Canada 3000 (2001) and Roots Air (2001). Few survive in the rabid dog-eat-dog world against the established airlines. But Clive Beddoe and his partners were determined

that WestJet was going to. He watched as discount airlines ValuJet and Southwest Airlines in the United States cut fares by 40 per cent – and still prospered, and was convinced that there was a market for a properly managed discount airline in Canada. Using only 737s, in 1996, Beddoe positioned WestJet as a no frills, lowfare airline offering flights between Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver, Kelowna and Winnipeg. Ticketless travel, snacks, no baggage connections and a young, goodhumoured staff were its hallmarks. And unlike the “legacy” airlines, WestJet had no crippling debts.

Others followed Beddoe. The Greyhound bus company started up its own discount carrier, Greyhound Air at the same time, taking another approach. Using the hub and spoke system, it chose Winnipeg as its hub and operated 727s on “spokes” to Vancouver, Kelowna, Calgary, Edmonton, Ottawa and Toronto. Kelowna Flightcraft Air Charter maintained the 727s while the bus company fed passengers from land to the air transportation system. Unfortunately, the start-up costs proved too high “if

TOP leFT:

An Air Canada Boeing 777.

(Photo courtesy ofAir Canada)

ABOve:

The present day Bombardier Challenger 605.

(Photo courtesy of Bombardier)

leFT:

In 1996, WestJet became a no frills, low-fare airline.

(Photo courtesy Brian Mcnair)

and the delays in the government regulatory system drove Greyhound Air to bankruptcy by September 1997. The WestJet model was more successful and today, the airline flies to 51 destinations including Hawaii and the Bahamas. Rare in the airline industry, its 6,200 employees are nonunionized, sharing in the airline’s profits.

When he took over Canadian Airlines on June 28, 1996, Kevin Benson likened his job to assuming the captaincy of the Titanic. He gamely negotiated a rescue package with the unions, dropped the European routes, increased capacity in the Far East with new 767s and put the regional airlines up for sale. It gave Canadian a temporary reprieve allowing the airline to exist on life support through the last years of the decade. In a final splash of glory, the airline grasped at new concepts, attempting to capture the road warrior (business traveller) market with airport lounges equipped with workstations and shiatsu massage attendants. In January 1999, it unveiled its “Proud Wings” livery – bringing back the

old Canada goose. But by now everything, from aircraft to cutlery, telephones to the “Proud Wings” logo itself was mortgaged; and as Canadian’s stock plummeted 90 per cent in five years, AMR was losing interest – and there was no sympathy in Ottawa, Victoria or Edmonton. Benson acknowledged that his airline was going to hit the wall by March 2000, and accepted the inevitable – initiating talks with Air Canada on a merger.

To everyone’s surprise, another suitor emerged. Financially sound and politically well connected, Onex’s Gerry Schwartz also proposed a merger of both airlines – but under Onex management. It would create he said “one, truly great, national airline.” Although Schwartz planned to name the new airline “Air Canada” and base it in Montreal, Canadian’s directors and financially battered employees were delighted –as was AMR. So was Ottawa, relieved that a private sector solution had been found. Buzz Hargrove, president of the Canadian Auto Workers, which had members in both airlines, thought it offered security for the first time in the aviation industry. But not so Robert Milton, Air Canada’s new wunderkind president. Cocky and flush with cash from Star Alliance and the Quebec pension fund “Caisse de depot” on Oct. 8, 1999, he had Air Canada’s shareholders publicly reject the Onex offer. Schwartz raised the stakes on Nov. 5 and that proved his undoing. The Quebec Supreme Court ruled that under the Air Canada Public Participation Act, the Onex offer would be illegal. At this Schwartz bailed out. Milton who could have allowed Canadian Airlines to fade away at no cost on Nov. 15, made a public offer to purchase it for $92 million. With his airline now losing $2 million a day, on Dec. 4, Benson recommended to the board of directors that it be accepted. In the last days of the century, Milton had achieved what his predecessors, from Gordon McGregor to Hollis Harris couldn’t –control over Air Canada’s archrival.

On Jan. 19, 2000, Air Canada’s Paul Brotto was appointed to succeed Benson at Canadian Airlines. The twin battles of debt restructuring and employee integration were fought through that first year as the airlines merged into one. When did Canadian Airlines – with roots in Canada’s aviation history as far back as Western Canada Airways in 1927 finally disappear?

Most agree that it was on Oct. 21, 2002, when the computer reservations systems were combined, its name vanished from airports and all tickets from that date were issued in Air Canada’s name only. Although it had been dealt a weak hand against the government-owned TCA from the earliest days, assuming the debt of the airlines it had taken over proved the undoing of Canadian Airlines.

The victorious Air Canada was soon to undergo its own near death experience. The 2001 economic downturn, 9/11, the SARS outbreak, soaring fuel prices, its pension fund problems and subsequent restructuring caused the country’s remaining national airline to struggle through the first years of the century. On April 1, 2003, hobbled by $12 billion in debt and two years of losses totaling $1.6 billion, it filed for bankruptcy protection under the Companies Creditors Arrangement Act. Led by Milton and later Monte Brewer, the airline painfully emerged from bankruptcy in 2004 under the holding company of ACE Aviation Holdings Incorporated that owned 75 per cent of the airline. While it survived to find more financing, by 2009, lower passenger revenue and a weaker Canadian dollar combined with rising costs on a number of fronts cut deeply into Air Canada’s profits and inevitably it shed 2,000 jobs. Parent ACE Aviation Holdings, having lost $633 million in 2008, planned to wind up its operations and distribute its 75 per cent stake to shareholders by April 2009. Analysts warn that any signs of a recovery for Air Canada are not likely until early 2010, aided by an influx of tourists for the Winter Olympic Games in Vancouver.

If ever a single aircraft radically altered airline economics, as well as the entire pattern of regional air transport, it was the Bombardier CRJ. But had another McConachie not written to Bombardier in 1986 about the potential of its 12-passenger Challenger executive jet, the CRJ family might never have been born. Eric McConachie, an Edmonton-born graduate of MIT and Stanford sent an unsolicited proposal to Canadair suggesting that the Challenger could be transformed from executive jet to passenger airliner. The fastest-growing and most profitable sector in the airline industry was the small, short-haul regional

carriers that fed passengers into the big airlines the world over. These little regional airlines (called the “mom-and-pop” carriers) flew rickety F27 turboprops into the hubs so that the passengers could transfer to the bigger jets. From its de Havilland plant at Downsview, Bombardier would cater to this market by expanding its turboprop portfolio, launching in 1998 the 70-seat Dash 8, the first of the Q Series that would evolve to the present day Next Generation (NG) aircraft.

But, the savvy McConachie pointed out that the executive Challenger (developed at great expense by Canadair) had been built with a wide-body fuselage, capable of two-by-two seating. Bombardier’s executives were intrigued enough to hire him and budget $14 million in August 1987, to study how to stretch the Challenger. One of its assets was, that, as Canadair, the company had built so many aircraft under licence that its workers were proficient at using CADAM (Computer Aided Design and Manufacturing). Bombardier CEO Laurent Beaudoin knew that his company couldn’t compete with Boeing or Airbus for large airliners but it might carve out a niche in regional jets. Its competitors in this field were Saab-Scania, Fokker, Short Brothers in Belfast and Brazil’s Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica SA, better known as Embraer. In 1989, the company launched the CRJ program selling its regional jet to airlines for routes of 650 to 1,500 kilometres, a distance that their turboprops couldn’t fly, but also shorter than their conventional jets could cover while still making a profit.

The CRJ concept arrived at an opportune time. Liberalization of air routes in North America as well as Europe was taking place and Communist China, Asia’s sleeping giant was about to trade in its Soviet designed antique aircraft for jet airliners. Whatever their nationality, passengers loved the CRJ because it was quieter and faster than a turboprop and with six-feet and one inch of headroom, four-abreast seating in two rows and 31 inches of legroom, was as roomy as the economy-class cabin of most airliners. The first CRJ 100, the 50-seat model, entered service with Germany’s Lufthansa CityLine in November 1992, and orders followed from Comair in the United States, Brit Air, Great China Airlines and Air Canada, which bought 26 CRJs to take advantage of “Open Skies.”

Although its CRJ200, 700 and 900 models are better known, the company kept its lead in the regional jet race by constantly adapting the aircraft: for example, to comply with the “scope clause,” which, because of the pilot’s contracts, limited the number of 50-seat aircraft in its fleet, Bombardier built the CRJ440 for Northwest Airlines with 44 seats. Its greatest success was undoubtedly selling 25 of the 70-seat CRJs to AMR’s American Eagle, the world’s largest regional carrier, for the high-density routes that its Embraer aircraft couldn’t handle.

Bombardier wisely adopted Aerospatiale’s strategy of passing around the risk. Of the $800 million spent to develop the Global Express, only 50 per cent came from Bombardier – the wings were designed and built by Mitsubishi, the engines by BMW-Rolls-Royce GMBH of Germany, the avionics by Honeywell in the United States and the flight controls by Sextant Avionique of France. Short Brothers were bought in 1989 to build centre fuselages. As Prime Minister Chrétien enthused about a Bombardier aircraft: “It’s virtually a G-7 project.”