TOP CROP MANAGER

WHEATMICROBE RELATIONS

Advantages include improved crop health

PG. 16

SUPER HARDY WINTER WHEAT

Plant breeders tackle complex challenges

PG. 30

VERY EARLY MATURING SOYBEANS

Pushing the boundaries of soybean production

PG. 44

Advantages include improved crop health

PG. 16

Plant breeders tackle complex challenges

PG. 30

Pushing the boundaries of soybean production

PG. 44

Cereal seed from Syngenta helps you harvest opportunities wherever they are. We’ve been breeding wheat in Canada for four decades, setting unprecedented standards for yield, quality and sustainability. The world depends on Canadian grain, and Canadian growers count on Syngenta.

6 | New cereal varieties update More choices in cereal crop production. By Bruce Barker

New wheat varieties show promise By Carolyn King

Helping microbes to help wheat By Carolyn King 44 Breeding for very early maturing soybeans By Carolyn King

20 | Beneficial wasp control for crop insects

Integrating biocontrol agents with pest management strategies.

By Donna Fleury

30 Super hardy winter wheat –is it possible? By Donna Fleur y

24 Phoma macrostoma: Natural weed control By Madeleine Baerg

SOIL AND WATER

36 | Running on empty Research shows N fertilizer needed on summerfallow fields. By Bruce Barker

40 Consider oats for irrigation alfalfa breaking By Bruce Barker PESTS AND DISEASES 32 Preventing problem fungi from becoming problems By Carolyn King

FERTILITY AND NUTRIENTS

50 Optimizing ESN and urea management By Carolyn King

Advances in plant breeding abound By Janet Kanters

In reference to the “Post-Harvest Weed Control” chart published in the September 2014 issue, BASF Canada has offered clarification on rotational crop safety when applying dicamba after September 1. Cereals and corn may be grown the following spring when dicamba is applied after September 1. However, canola, soybeans and white beans should not be grown, as they are more sensitive to dicamba residues. For fall applications, BASF recommends Distinct herbicide, and notes that Distinct is active at temperatures lower than 5 C. For further information, please consult the label and contact your local BASF representative.

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

JANET KANTERS | EDITOR

Grown on more than 20 million acres in Canada in 2014, canola represents a significant contribution to the agricultural economy. Indeed, a Canola Council of Canada study released in 2013 shows Canadian-grown canola contributes $19.3 billion to the Canadian economy each year, including more than 249,000 Canadian jobs and $12.5 billion in wages.

That’s why an international project that has deciphered the complex genome of Brassica napus is so exciting. The study results provided ground-breaking knowledge about the origins of crop species that will help accelerate ongoing breeding efforts in the crop.

Dr. Boulos Chalhoub, from the National Institute for Agricultural Research in France, led a team of scientists from 30 research institutes from all regions where the crop is produced, including the National Research Council Canada (NRC). Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) researcher from Saskatoon, Dr. Isobel Parkin, is part of the international research team.

According to Chalhoub, Canada’s contribution was an essential component of the research, assisting with the complicated task of assembling the canola genome and providing access to the genome for one of the ancestral parental species. This is not by accident: researchers in Saskatoon have a long history of working with the crop. In fact, the species most commonly grown today, and whose healthy oil is found on the shelves of every supermarket, was developed through collaboration between scientists at AAFC, NRC and the University of Manitoba in the 1970s.

Canola, one of the most recent plant species on Earth, has a unique origin. The first Brassica napus plants originated just a few thousand years ago from unintentional crosses between European cabbages and Asian turnips. While all flowering plants originated from such events (but in most cases millions of years ago), the canola genome provides unique insight into the early formation of new species in plants.

According to information from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, unlike many other plants, canola has retained almost all of the genes of its two parental species, probably due to breeding efforts. These multiple gene copies provide novel material for further adaptation of the crop. What’s really exciting is that with around 101,000 genes, it contains one of the highest gene densities of any sequenced organism – in comparison, humans have less than 30,000 genes.

Parkin says the knowledge gained from this recent study will prove invaluable for making future agronomic improvements to canola, and will contribute to sustainable increases in oilseed crop production to meet growing demands for both its edible and biofuel oils.

In this issue of Top Crop Manager, we feature several other plant breeding topics that are of particular interest to Prairie crop producers, including the development of very short season soybeans. Dr. Elroy Cober, a soybean breeder at AAFC in Ottawa, says with the continued interest in growing soybeans in Manitoba and the increasing interest in Saskatchewan and Alberta, “we’ve seen a need to push for even earlier maturing soybeans.”

Also in this issue we feature a story about new wheat varieties developed at the University of Alberta. And, as usual at this time of year, we present our annual cereal varieties update – a close look at cereal varieties available for the 2015 crop season from public and private plant breeders.

Enjoy!

1717-452X

CIRCULATION email: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES Crop Manager West - 9 issuesFebruary, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, September, October, November and December1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

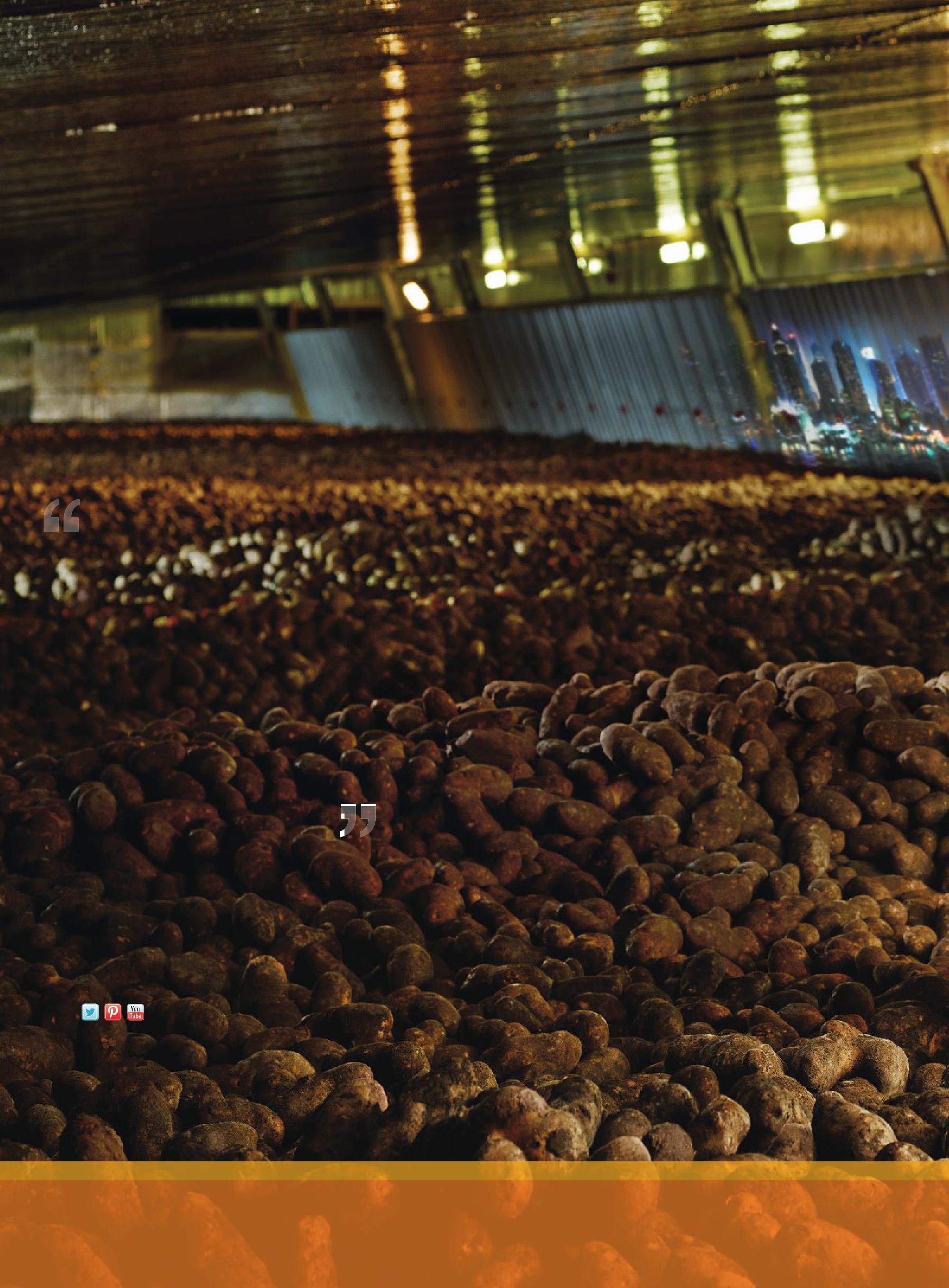

Potatoes in Canada 4 issues Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter 1 Year $16.00 Cdn plus tax All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail

www.topcropmanager.com

Overlap happens on every farm, every year – wasting valuable inputs. SeedMaster’s Auto Zone Command™ overlap control technology helps eliminate overlap – saving SeedMaster customers millions of dollars since it was introduced in 2011.

Auto Zone Command is smart, proven technology – included at no additional cost on all SeedMaster metering systems. Contact your closest dealer and find out how Auto Zone Command can save you THOUSANDS every year on your farm!

by Bruce Barker

Public and private plant breeders continue to bring new cereal varieties to market, with improved yield, disease resistance and agronomic performance. Obtainable in commercial quantities for the 2015 planting season, 17 new varieties are available throughout the different cereal classes.

AAC Brandon is an awned, semi-dwarf CWRS variety. Compared to AC Carberry, it has five per cent higher grain yield, 0.5 days earlier maturity, is one cm shorter, and has similar lodging, tolerance and disease resistance. AAC Brandon is well-adapted across Western Canada but will be especially attractive to wheat producers in the high yielding areas of the Prairies who desire a short, strong strawed variety with good Fusarium head blight (FHB) resistance. Available from SeCan Association members.

AAC Elie is an awned, semi-dwarf red spring variety that will work well for growers looking for excellent yields, good disease resistance and consistent performance across the Prairies. AAC Elie has short, strong straw, and is later maturing but similar to Carberry. In three years of Western Bread Wheat Cooperative tests across Western Canada from 2009-2011, AAC Elie yielded 4.6 per cent more than the average of the

checks. In these tests, AAC Elie averaged almost four per cent more than Carberry and had an average grain protein of 14 per cent. AAC Elie has an intermediate reaction to loose smut, common bunt and leaf spots. AAC Elie is resistant to known races of stem and leaf rust. Available through Alliance Seed retailers including Parrish & Heimbecker, Paterson Grain and Alliance seed retailers.

AAC Redwater is an awned, early maturing CWRS with good lodging tolerance and disease resistance. AAC Redwater is well adapted across Western Canada, but will be especially attractive to wheat producers in the shorter-season areas of the Prairies who desire a short, strong-strawed variety with fair/intermediate FHB resistance. AAC Redwater is expected to have excellent grade retention based on its parentage of AC Intrepid/Harvest/McKenzie. Available from SeCan Association members.

CDC Plentiful is a very early maturing, hard red spring wheat. It has excellent resistance to FHB and a very good rating for resistance to lodging. CDC Plentiful is resistant to leaf rust, stem rust and stripe rust. It yields 110 per cent of AC Barrie. CDC Plentiful will be very popular in

ABOVE: Seventeen new cereal varieties are available for the 2015 crop season, with improved yield, disease resistance and agronomic performance.

As a farmer, you have a lot of decisions to make. The DEKALB® brand team is here to empower you with expert advice, agronomic insight and local data. With every important decision you face on your farm, we’re behind you. And we’re ready to help you turn great seed potential into actual in-field performance. DEKALB canola, corn and soybeans... Empowering Your Performance.

® Talk to your DEKALB dealer today, or visit DEKALB.ca

all areas due to the complete package of yield and disease resistance it delivers. Available from FP Genetics.

AAC Ryley is an awned, early maturing CPSR spring wheat with high yield potential, improved protein and good disease resistance. AAC Ryley should be an excellent replacement for AC Crystal. It is well adapted and will be especially attractive to wheat producers in the shorter season areas of the Prairies. Available from FP Genetics.

Enchant VB is a hard red spring wheat that yields 117 per cent of AC Barrie. It has very good resistance to leaf rust, stem rust and bunt. It brings resistance to the orange wheat blossom midge, which saves time, reduces cost and increases returns for the grower. Available from FP Genetics.

AAC Current is a Canada Western Amber Durum (CWAD) with excellent yield potential, especially in the traditional durum growing areas of Zones 1 and 2. In three years of durum co-operative tests, AAC Current yielded an average of two per cent more than Strongfield in the main durum growing area (Zone 2). AAC Current has good straw strength and is slightly taller than checks with similar maturity to Strongfield. The test weight of AAC Current was significantly higher than all the checks in the durum co-op trials. It is rated resistant to leaf and stem rust. Available through Alliance Seed retailers including Parrish & Heimbecker, Paterson Grain and Alliance seed retailers.

AAC Raymore is one of Canada’s first durum varieties with a very solid stem, which provides excellent sawfly resistance. Agronomically, AAC Raymore is very similar to AC Strongfield, with comparable height, lodging, yield, disease tolerance and quality characteristics. Available from SeCan Association members.

CDC Fortitude offers improved yields over Strongfield, and introduces a high level of solid stemness in the durum class, minimizing the risk of grade and quality loss resulting from wheat stem sawfly. With improved lodging over Strongfield, and moderately resistant rating for FHB, CDC Fortitude is an excellent option for durum acres. Available through Proven Seed at CPS retail locations.

AAC Gateway is a new Canadian Western Red Winter (CWRW) wheat variety bred by Rob Graf in Lethbridge, Alta., with top yields and protein, and an excellent disease package. AAC Gateway has best-in-class lodging

resistance with very short, strong and uniform straw. AAC Gateway is well adapted throughout Western Canada and will be available for the fall of 2015 from select Seed Depot dealers and Seed Net in Alberta.

Pintail is a new Canadian Western General Purpose (CWGP) wheat developed at the Field Crop Development Centre in Lacombe, Alta. It is a very high yielding (107 per cent of Radiant) feed wheat with excellent winter hardiness, as well as good lodging and stripe rust resistance. Seed is now available in commercial quantities through Mastin Seeds retailers.

AAC Synergy two-row malting barley yields 113 per cent of AC Metcalfe and 107 per cent of CDC Copeland. The variety matures similar to AC Metcalfe and produces heavy, plump kernels and short, strong straw with good resistance to lodging. The widely adapted variety offers high yield potential, good foliar disease resistance and excellent malting quality. AAC Synergy is currently under market development by Syngenta Canada and is available through Richardson and Cargill.

Amisk is a six-row feed barley with a semi-smooth awn. It has grain yield similar to Vivar six-row feed barley with 15 per cent higher plump kernels than Vivar. It has very good lodging resistance. Maturity is rated as medium. Available from SeCan Association members.

Brahma is a new, two-row feed barley that offers growers the top yield performance they have come to expect from Proven Seed and CPS, while providing improvements to disease resistance and harvest efficiency. Available through Proven Seed at CPS retail locations.

CDC Maverick is a two-row, feed and forage barley with a smooth awn for improved palatability and is considered a good replacement for CDC Cowboy. It is a tall plant with top forage and silage yields, with a 16 per cent higher forage yield than AC Ranger. It is well suited for dry areas or low input production. It is moderately resistant to FHB and has a medium maturity similar to AC Metcalf. Available from SeCan Association members.

CDC Haymaker forage oat is a good replacement for CDC Baler forage oat with a seven per cent higher yield than CDC Baler. CDC Haymaker has a tall stature, later maturity and large, plump kernels. It has good forage quality and improved digestibility. Available from SeCan Association members.

CS Camden is a white milling oat that has been selected through Canterra Seeds’ research and product development program. This oat is from the same breeding program as Triactor and has very high yields and a shorter stature with better lodging resistance. It also displays improved quality attributes with higher per cent plumps and higher beta-glucan. CS Camden is under evaluation with millers. Look for CS Camden at a Canterra Seeds retailer near you.

Brasetto is the first viable hybrid cereal to be introduced to Western Canada. It features very high yield, approximately 20 to 25 per cent better than current varieties. Brasetto is shorter, and its greater uniformity in maturity will mean straight cutting is possible. It also has better winter hardiness than other winter crops. Brasetto exhibits a significantly higher falling number than existing varieties, making it even more valuable for baking and distilling. Available from FP Genetics.

Grain Guard’s new line of 4" wide corrugated grain bins are manufactured using state-of-the-art technology and are available in diameters from 15' to 105' in flat bottom models, as well as 15' to 27' in hopper bottom models. With an established catalogue of aeration and conditioning equipment, high-quality grain storage bins are yet another solution provided by Grain Guard.

Grain Guard also offers turnkey construction packages on all flat bottom bin models. Trust the storage and conditioning experts to be your one-stop shop.

Small breeding program targets early maturity, high yields and disease resistance.

by Carolyn King

In the last two years, three new cultivars have come out of the University of Alberta’s wheat breeding program, and more are on the way. To put that in perspective: from 1959 to 2012, the university released a total of three wheat varieties. The current program, led by Dr. Dean Spaner, may be small, but it’s developing some top-notch varieties.

Spaner started his wheat breeding program about a dozen years ago. His main emphasis is on Canada Western Red Spring (CWRS) wheats, but he’s also doing some work with Canada Prairie Spring (CPS) and Canada Western General Purpose (CWGP) wheats. CWRS wheats are high protein, hard wheats with superior milling and baking qualities, and are often used for yeast breads. CPS wheats have good milling and baking qualities and somewhat lower protein levels than CWRS. And CWGP wheats have higher starch and lower protein contents than milling wheats, making them suitable for uses like ethanol and animal feed.

Spaner’s breeding program draws on diverse breeding material. “Every year we get some germplasm from international nurseries. For example, two of the three lines that we’ve registered in the last two years have had roughly one-third of their germplasm from CIMMYT [International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center] in Mexico, from international sources,” he says. “We also get some germplasm from Canadian and American wheat breeders, and we may start to get some from Europe.”

Funding from the Western Grains Research Foundation and the Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund, and more recently the Alberta Wheat Commission, has been very important to the program’s success. Spaner has also received funding support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Three CWRS varieties released

All new wheat cultivars seeking to become registered varieties for use in Western Canada are evaluated by the Prairie Recommending Committee for Wheat, Rye and Triticale. This committee makes registration recommendations to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s Variety Registration Office based on the results of multi-location, multi-year, replicated trials to evaluate agronomic performance, disease and insect pest responses, end-use quality and other traits. The trials follow specific procedures to ensure the resulting information is relevant, unbiased and representative of the candidate cultivars.

The committee recommended Spaner’s BW947 and PT765 cultivars in 2013, and his PT769 in 2014. All three are CWRS wheats that

Mastin Seeds has the rights to PT769, a very early, high-yielding variety with large kernel size and good disease resistance.

out-yielded the check varieties in their registration trials.

PT765 has been registered as Coleman. Spaner says this high-yielding, early maturing variety has elevated resistance to Fusarium and very good stripe and leaf rust resistance.

Lefsrud Seed at Viking, Alta., has the rights to Coleman. According to Ed Lefsrud, they expect to have very small amounts of seed available by the spring of 2015. “If the variety is as good as it appeared last year, then by spring of 2016 there should be a few townships of seed available.”

Lefsrud likes Coleman’s disease package and its earliness. “In southern Alberta, it was the first to head out this year,” he says. “We’re hoping it will do well in the Red Deer region and north.” He is pleased that Spaner’s program is developing varieties like Coleman that per-

Introducing AFS Connect.™ The only advanced farm management system that guards your data as closely as you. It’s simple. When you buy a combine, a tractor or a piece of land, it’s yours. So when you buy a farm management system that gives you one easy dashboard to track and manage every piece of equipment on your farm, the data should be yours — yours alone. See how AFS Connect gives you total control over your data at caseih.com/afsconnect

form well in the Parkland region.

Canterra Seeds has the rights to BW947. The company has picked a name for it, but it is not yet registered with the Variety Registration Office.

“We’re keenly interested in Dr. Spaner’s program, and in BW947, which we think has an excellent fit for Western Canada,” notes Brent Derkatch, director of operations and business development at Canterra Seeds. “His program has been able to incorporate some unique germplasm into BW947, and genetic diversity is important for making positive gains in product performance in wheat.”

BW947 combines great yield potential with early maturity, says Derkatch. “BW947 yields five per cent higher than Carberry, which is one of the leading yield products in Western Canada, and it’s five days earlier than Carberry. It’s not easy for breeders to make yield gains and also shorten the maturity window. So I think this variety could work quite well from Manitoba all the way up into the Peace River area of B.C. and Alberta.”

He also likes this awnless variety’s well-rounded combination of other traits, such as resistance to stripe rust and leaf rust, moderate resistance to stem rust, good lodging resistance and very good quality.

Canterra Seeds accelerated seed production of BW947 in New Zealand in the winter of 2013-14, so the company expects to have Certified seed available in the fall of 2015, for spring 2016 planting. (To meet the demand for seed, seed companies may rely on winter season production in warm climates. This off-season, winter production is commonly referred to as contra season production.)

“There’s an added cost to contra season seed increases, so seed companies are very careful about which products they select for

that,” notes Derkatch. “BW947 was one of the first wheat varieties that we’ve chosen for a contra season increase. That’s because we believe it has the potential to become a very popular variety.”

Mastin Seeds in Sundre, Alta., has the rights to PT769. Bob Mastin likes the variety’s “large kernel size, high yields, early maturity, good lodging resistance and good disease resistance.”

According to Spaner, PT769 is one of the earliest cultivars on the Prairies. Mastin says, “I’m always interested in early. I’m on the western edge of Alberta up against the foothills, so I’ve grown up farming in a reduced season area and early is important. I also believe that with the wild weather we’ve been having lately, we’re getting a lot of violent or unseasonable weather in the spring that delays seeding. So I think early maturing varieties will be of interest everywhere, even in the longer season areas.”

He adds, “There were two early spring wheat varieties I was looking to bid on, this one and an Ag Canada variety. I was amazed when I looked at them to see that their data was almost identical, even though they had totally different breeding backgrounds.

“I settled on PT769 for several reasons. One was it had CDC Go heritage. I’ve grown Go, I like Go, and a lot of farmers like Go. I also have never bid on a variety from the University of Alberta and I wanted to become more familiar with their program. And if I can support a local breeder in a smaller breeding program, I’m all for that, and he’s developed a world-class product.”

Mastin expects to have PT769 seed available by spring 2016. He’s currently holding a contest to name the variety. “I’m hoping to incorporate Go in the name so people will want to give the variety a try.” Some of the suggestions so far are Go Early, Go Far, Go Forward and Go West.

Early maturity is a major focus of Spaner’s breeding program. Over the last decade, his group has had various projects with CWRS, CPS and CWGP wheats related to the genetics of earliness.

“We’re the northern-most wheat breeding program, so focusing on early maturity makes sense,” says Spaner. He notes that earlier maturities allow earlier harvesting and reduce the risk of problems like frost damage, pre-harvest sprouting and downgrading of wheat quality.

Resistance to stripe, stem and leaf rust is also a special interest, especially as stripe rust has emerged as a growing problem in Alberta. Spaner’s group is currently working on mapping genes for rust resistance and pyramiding several sources of resistance into breeding lines, to provide more durable resistance to these diseases.

One of the biggest challenges for the program is Fusarium resistance. Spaner explains, “We can screen for all the rusts, bunts and other diseases through our disease nurseries, and we can screen for quality and early maturity, but we can’t screen for Fusarium because

we can’t bring Fusarium here [to Alberta]. So we have to do that screening in Manitoba, and getting space in Manitoba [Fusarium nurseries] has been a challenge.”

Developing improved CWRS lines is also challenging. “CWRS is an extremely difficult class to breed in because it encompasses so many traits that have to be pooled together,” he says.

A further challenge for this small breeding program is that it has dual goals. Spaner notes, “As [the operator of] a university program, my mandate is not 100 per cent about breeding wheat. My mandate is also to educate scientists who will in the future be breeding wheat or part of the agricultural scientific community.”

The program is clearly up to these challenges. Spaner currently has, along with the three new varieties, several CWRS lines in the third and second years of the registration trials, and some CPS and GP lines in the first-year trials.

For more on plant breeding, visit www.topcropmanager.com.

If you’ve ever searched for the secret to consistent and reliable yields, you probably already know the answer is Proven® Seed. Year over year, growers choose Proven Seed because we spend so much time researching, developing and testing our seed varieties across western Canada to ensure it’s the best choice for local growers. Learn more at ProvenSeed.ca or ask your CPS retailer.

Improving crop health, quality and yield by drawing on wheat-microbe interactions.

by Carolyn King

When we look at a wheat field waving in the wind, we don’t see the incredibly complex community of micro-organisms associated with those plants.

But with the help of DNA sequence-based methods, researchers are starting to shed light on that complexity. They’re finding that the microbial community’s characteristics are critical to the success or failure of those plants.

A major project is underway to learn more about these wheat-microbe relationships. The resulting information will help wheat growers to choose practices that favour beneficial microbial communities. The potential advantages include improved crop health, reduced fertilizer inputs, enhanced crop quality, and increased yields.

“We’re looking at the plant as it really exists, which is a plant-microbe consortium. And it’s that biological system that is healthy or unhealthy, or robust or fragile,” explains Dr. Sean Hemmingsen, research officer with the National Research Council Canada (NRC) in Saskatoon, Sask.

Hemmingsen is leading the project, which is one of six initiated by the Canadian Wheat Alliance. Partners in this alliance are the NRC, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), the University of Saskatchewan (U of S), and the Province of Saskatchewan. They have made an 11-year commitment, starting in 2013, to support and advance research that will improve the profitability of Canadian wheat producers.

Hemmingsen’s project, called Beneficial Biotic Interactions, involves a team of researchers from the NRC, AAFC and the U of S. Together they bring expertise in molecular biology, DNA sequencing, computational biology, biomathematics, microbial ecology, wheat genetics, wheat pathogens, beneficial wheat

microbes and wheat production systems to the project.

Hemmingsen’s own interest in microbial communities has its roots in his post-doctoral research in the 1980s. “I was studying what we thought was a novel plant protein that was doing something a little bizarre in plants. My research led me to learn that in fact we were dealing with a universal protein that was performing a universal function that is essential for virtually all cell types.

“The function of the protein is to chaperone protein folding – in other words, to allow protein folding to occur in the cell without problems happening.” Proteins need to fold into the correct threedimensional form to be able to properly carry out their functions.

The chaperoning role gives Hemmingsen’s protein its name: chaperonin-60. Just as a traditional chaperone accompanies young people to make sure nothing improper happens, chaperonin-60 and other such “molecular chaperones” make sure that nothing improper happens during protein folding or the assembly of other large molecules.

As part of his research, Hemmingsen designed PCR primers for the chaperonin-60 gene. PCR primers are used to “amplify,’ or clone, a specific portion of DNA. His primers are able to amplify a particular region of the chaperonin-60 gene from any kind of DNA, whether that DNA is from a bacterium, alga, fungus, plant or animal.

It turns out that these primers are extremely useful for distinguishing between different microbial species. For example, instead of sequencing the full genomes of all the microbes in a

ABOVE: Although we can’t see the microbial community associated with these wheat plants, that community is critical to the crop’s success.

soil sample, researchers use the primers to target that region, using it as a DNA marker or “DNA barcode,” and they sequence that marker in every organism in the soil sample to identify the different species.

Since 1999, Hemmingsen and his colleague Dr. Janet Hill have been developing and improving microbial detection and identification methods using chaperonin-60, in combination with the NRC’s expertise in high-throughput DNA sequencing. High-throughput sequencing is key because microbial communities can have huge numbers of micro-organisms and a wide diversity of species. For instance, a single soil sample might have thousands of micro-organisms.

Hemmingsen and Hill have been using these methods in collaborative studies with experts in other disciplines. They have found that the characteristics of microbial communities within humans, animals and plants have significant effects on human, animal and plant health, respectively.

“Molecular methods that we’ve developed based on DNA sequences give us a way of looking at the microbial communities, understanding what is present, and understanding what kinds of activities the things that are present are doing at a molecular level,” says Hemmingsen.

He emphasizes that microbial communities have to be understood and managed on an ecological basis. “It’s not just the presence or absence of a particular organism. It is all the different organisms that are present and their complex interrelationships that matter. You can have a field that has a particular pathogen in it, but you can happily plant a crop there because the microbial community is such that the pathogen never gets a serious chance to harm the plants. But under different conditions, the pathogen would devastate the plants.”

Fortunately, DNA-related technologies are advancing by leaps and bounds. In particular, the power of these technologies, including the ability to analyze the data, has skyrocketed. At the same time, sequencing costs have plummeted. This combination is allowing the project’s researchers to study and understand wheat-associated microbial communities at a whole new level.

The wheat-microbe project involves three components: technology enhancement; three field studies; and, a feasibility study.

The technology enhancement component includes several activities. For instance, the researchers are figuring out how to best use the available and newly emerging DNA sequencing technologies to drive down the cost per sample for the microbial community analysis. They are also comparing chaperonin-60 with other universal markers. Some types of universal markers work better than others for certain types of organisms, so using several markers will ensure the researchers haven’t missed any groups of organisms. As well, using several markers means the project’s results will be comparable to the results from many other studies.

In the three field studies, the researchers are looking for patterns and trends in the microbial communities under different field conditions, and trying to figure out which micro-organisms and groups of micro-organisms might be acting in a beneficial or harmful way in a given circumstance.

One of the three field studies is led by Dr. Myriam Fernandez, a plant pathologist with AAFC. Her study aims to determine

how practices like herbicide application, tillage and crop rotation affect a wheat crop’s yield, quality, disease levels and so on, and how that relates to the characteristics of the microbial communities living in the soil or within the plant.

Hemmingsen explains that other studies have shown that agricultural practices can affect plant-microbe relationships. For example, tillage interferes with fungal-plant interactions, and agrochemicals influence the soil microbial ecology in various ways. Fernandez’s study will help clarify just how wheat growers can adjust their practices to get the full benefits of the microbial community for their crop.

Dr. Curtis Pozniak, a wheat breeder at the U of S, is leading the second field study. He has picked 10 elite wheat cultivars as representatives of the genetic range of modern wheat varieties. He’s applying just enough fertilizer to get the crop established, but nothing more. The idea is to assess the cultivars’ relative ability to interact with soil microbes to acquire nutrients.

“Most people have heard of the relationship between Rhizobium bacteria and leguminous plants, like peas, [where the bacteria provide nitrogen to the plant]. But such [nutrient-supplying] relationships are far more widespread than many people might be aware of,” says Hemmingsen. “They are give-and-take relationships. The plant puts a lot of the energy into fixing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into organic carbon, and it spends a lot of that carbon keeping the bacteria and fungi that are beneficial to it, happy. In return, those bacteria and fungi provide the plant with a serious amount of its nutrients.”

By understanding the role of microbial interactions in wheat production, this project could help farmers manage those interactions to improve crop yield and quality.

These types of nutrient-supplying plant-microbe relationships allow a farmer to reduce chemical fertilizer inputs. They also offer environmental benefits because they reduce the risk of nutrient losses to the water and the air.

However, for many decades, elite wheat cultivars have been bred to perform well when given the nutrients they need in the chemical form that they can use directly. Hemmingsen says, “So we’re asking the question: are any of the cultivars better at fending for themselves because they have retained the ability to work well with the [nutrient-supplying] bacteria and fungi in the soil?”

Dr. Bobbi Helgason, a soil molecular microbiologist with AAFC, is leading the third field study. This study is taking place at the site of a fertilizer trial that has been running for over 100 years at AAFC’s Lethbridge Research Centre. That long-term trial includes fields that have had only nitrogen fertilizer, only phosphate fertilizer, or only nitrogen plus phosphate fertilizer during all those years.

At this unique site, Helgason is examining the effects of those longterm fertilizer treatments on the microbial communities in the soil and within the wheat plant, and evaluating how any differences in the microbial communities relate to wheat performance.

NRC scientist Dr. Shawna MacKinnon is heading the feasibility study in the project. She is exploring the possibility of applying single-celled algae to agricultural fields and assessing how such applications affect wheat crops.

Hemmingsen explains that agricultural areas near the ocean have a long history of applying kelp, multicellular algal seaweed, as a soil amendment. “Researchers have found that these algal seaweed amendments have various benefits to the plants. To a certain extent they are acting as fertilizers, but they are also affecting some plant hormone activities and in some cases producing a disease-suppressive effect.”

MacKinnon’s study is related to an NRC program to investigate the potential for carbon capture by single-celled algae. The idea of that program is to create useful biomass while reducing greenhouse gas emissions from carbon sources like the oil industry or livestock manure. “Knowing that the algal carbon capture program was being developed, Dr. MacKinnon wondered if any of the algae tested in that program might have the same kind of beneficial characteristics as seaweed,” says Hemmingsen.

Two other key team members in the wheat-microbe project are Matthew Links, a computational biologist and biomathematician, and Dr. Tim Dumonceaux, who has expertise in microbial communities and molecular methods. They are both with AAFC.

By deepening our understanding of the role of microbial interactions in wheat production, the project’s results will help farmers manage those interactions to improve crop yield and quality, increase the crop’s ability to withstand stresses like disease, and decrease fertilizer inputs.

In the bigger picture, Hemmingsen sees even greater promise ahead for such studies. “I think if we could leap 20 years forward and look back to now, we’d be looking at the beginning of a really productive time in agricultural research, where we are really starting to come to grips with the potential that can be gained from understanding and managing the plant-microbe biological system.”

For more on plant breeding, visit www.topcropmanager.com.

Integrating biocontrol agents with pest management strategies.

by Donna Fleury

Researchers are working with growers to find ways to integrate biocontrol agents into their pest management strategies for dealing with pests such as cereal leaf beetle, lygus bugs and wheat stem sawfly. In cereal crops there aren’t too many perennial insect pests, and the ones that are a problem are often difficult to control with foliar insecticides, so biocontrol agents may offer an alternative option.

Indeed, beneficial insects, such as parasitoid wasps, can play a key role in integrated pest management strategies and provide growers with long-term economical and environmentally friendly options.

“Although we are working on biological control for several crop insects in Western Canada, the one that we currently have the most data on and are promoting most intensively is a beneficial wasp biocontrol agent for cereal leaf beetle,” explains Héctor Cárcamo, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta. “Cereal leaf beetle is a pest of most cereal crops as well as cultivated and non-cultivated grasses. This pest is also a major concern and trade irritant for hay exports to the U.S., where several jurisdictions have restrictions on hay products that have not been fumigated or sterilized in some form against cereal leaf beetle.”

The cereal leaf beetle, first identified in southern Alberta in 2005, is now found in different parts of Western Canada. The highest populations are still in southern Alberta, near Coaldale and east. Although growers have reported seeing a lot of stripping of leaves on cereal crops, so far the pest levels have not reached threshold levels that make spraying necessary. The cereal leaf beetles are possibly being transported in hay and are appearing in areas where they weren’t located before, such as the Swan River Valley in Manitoba, southwest Manitoba, Edmonton, Lacombe and Olds, Alberta, and in southeast Saskatchewan.

“The good news is that the parasitoid wasp has been very effective at reducing the numbers of cereal leaf beetles and it has followed the expansion of the beetle across Western Canada,” says Cárcamo. “The Tetrastichus julis wasp is small, but very efficient, and if there are cereal leaf beetle larvae in the area, they will find them. We’re not sure how far they fly, but they are able to travel at least hundreds of metres, as they are quite good at following the larvae in areas where the beetle has invaded.”

T. julis overwinters as pupae in the soil, emerging in the spring or early summer, so it is important for growers to reduce tillage

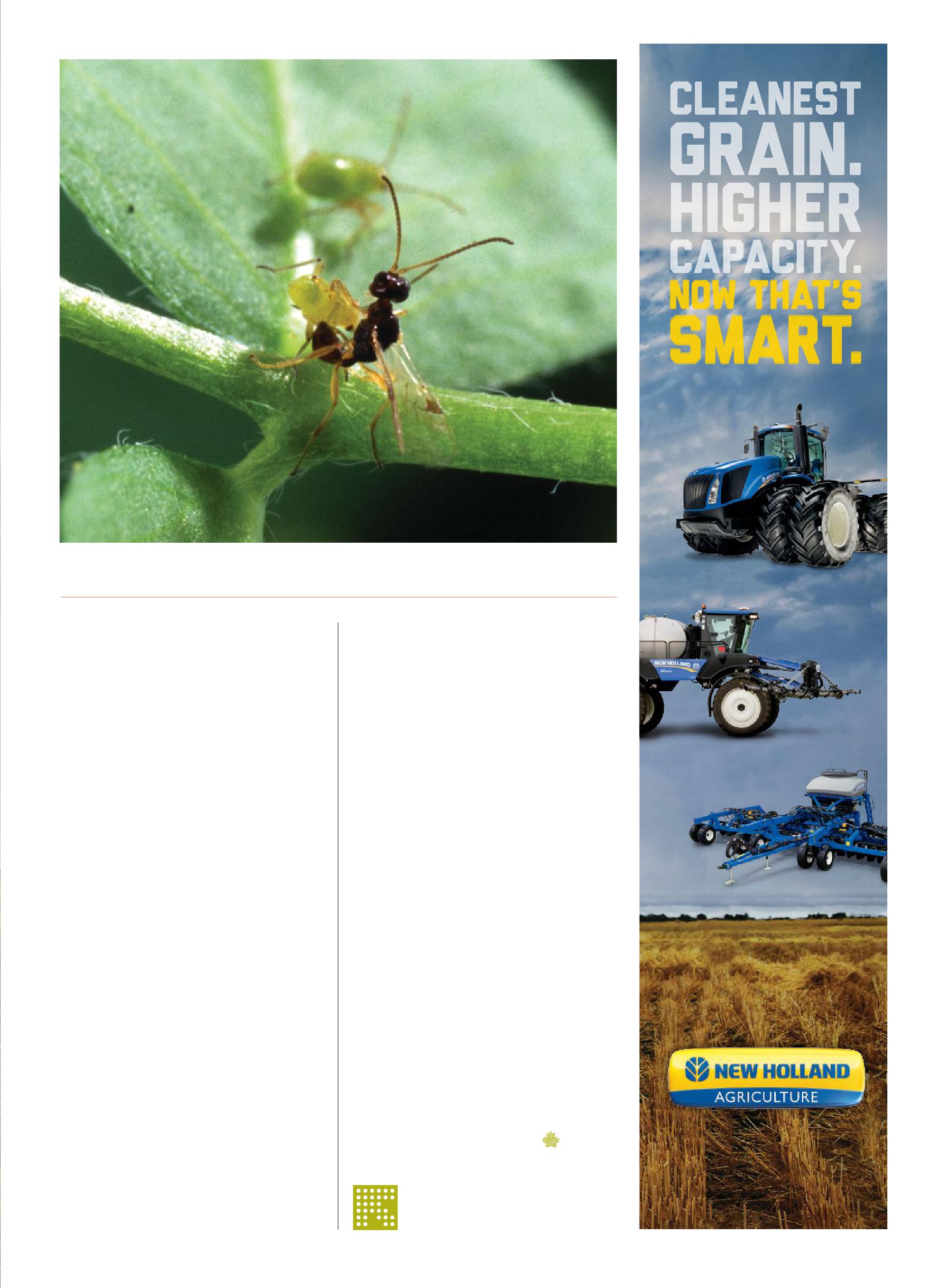

Tetrastichus julis beneficial wasp attacking cereal leaf beetle larva.

and not spray with an insecticide. The T. julis wasp kills the beetle by boring into the beetle larvae. The wasp lays about five eggs, which hatch in the larvae and devour the beetle. This beneficial wasp only attacks the cereal leaf beetle and does not pose a risk to other insects or humans. In areas where T. julis is well established, beetle populations can be reduced between 40 to 90 per cent, and yield losses can be prevented without using insecticides.

Cárcamo and his team continue to evaluate cereal leaf beetle larvae in new areas as the beetle expands its range, and if no parasitoids are present, then they relocate T. julis adults to those locations to become established and provide control. T. julis are reared in a lab in Lethbridge or collected from the field. In July 2014, T. julis adult wasps were sent to Lacombe and Edmonton,

and to locations in Saskatchewan and Manitoba

“We are also doing a study of landscape effects on the introduction of the beneficial wasps, and have a graduate student at the University of Manitoba who is assessing the populations of the parasitoids in about 30 fields in southern Alberta,” adds Cárcamo. “This information will help us develop a better understanding of the populations of both the cereal leaf beetle and the T. julis, as well as developing better recommendations.”

Cárcamo has developed a factsheet with information about cereal leaf beetle and biological control with T. julis

In another project, researchers are trying to determine which biocontrol agents could be effective for control of lygus bugs, which are a pest in crops such as oilseeds, pulses and legumes. “We don’t currently have an effective biocontrol agent for lygus, but we are evaluating what native parasitoids we have on lygus,” explains Cárcamo. “We have identified a few native parasitic wasp species, Peristenus sp, that kill the lygus in the nymphal stage; however, they are not very abundant and attack lygus at low density. Therefore, we are conducting an environmental study with an exotic wasp introduced from Europe into the U.S. for control in alfalfa. We are testing this species, Peristenus digoneutis, to see if it can control lygus in Alberta and to determine if there are any potential negative effects on our native beneficial species.”

The introduced P. digoneutis wasp has spread naturally from the U.S. to Ontario and Quebec, but so far has not been found in Western Canada. Cárcamo is testing the P. digoneutis wasp in the

Bracon cephi, another beneficial parasitic wasp species for potential biocontrol of insect crop pests.

Lethbridge quarantine facility to determine if it will be effective. Although he is not sure if it will get established in the drier prairie climate, it is worth evaluating.

“We have a graduate student at the University of Lethbridge who is doing competition studies to compare this exotic wasp with our native wasp,” notes Cárcamo. “However, we are finding it difficult to rear the native wasp and increase the population to high enough levels for the study.”

The LEMKEN RUBIN is the only compact disc with:

■ Individual 24” notched blades

■ Two rows of rebound harrows

■ Preset spring protection for individual discs

Knock down your stubble in just one pass with the LEMKEN RUBIN compact disc. The RUBIN’s full-surface cultivation and optimal soil-trash mixing will work in all kinds of residue and smooth out ruts so your fields are cleaned-up and reconsolidated after a single high-speed pass.

Call your dealer to try a LEMKEN RUBIN and see how Blue works!

■ Individual maintenancefree double ball bearings

■ 19 models ranging from 8 to 40 feet

■ Tandem packing and depth rollers

Manitoba

Agcon Equipment Winnipeg (855) 222-9216

Ag West Equipment Ltd. Portage la Prairie (204) 857-5130 Neepawa (204) 476-5378

Avonlea Farm Sales Domain (204) 736-2893

Greenland Equipment Ltd. Carman (204) 745-2054

Nykolaishen Farm Equipment Swan River (204) 734-3466

Reit-Syd Equipment Ltd. Dauphin (204) 638-6443 (877) 638-9610

Saskatchewan

All West Sales Partnership Rosetown (306) 882-2024

GlenMor Equipment LP Prince Albert (306) 764-2325

Lazar Equipment Ltd. Meadow Lake (306) 236-5222

Nykolaishen

(403) 782-6873

Deer (403) 346-1815 Millet (780) 387-4747 Westlock (780) 349-3113 Dawson Creek (250) 719-7470

There are also beneficial wasps that can control wheat stem sawfly. The parasitoid wasp, Bracon cephi, is being found in higher numbers in southern Alberta. Other work being led by AAFC researchers at other research stations in Canada is focused on trying to find a biocontrol agent for cabbage seedpod weevil, but so far they have not identified any species that are considered effective or safe to use. They continue to look for other species of parasitoid wasps that may prove to be suitable.

“Our main recommendation for growers is to avoid spraying insecticides in order to encourage the survivorship of beneficial wasps and other biocontrol agents,” explains Cárcamo. “Other beneficials, such as ladybird beetles, have been found to feed on cereal leaf beetle eggs and other pests, so improving their chances of survival is important. In cereals, if wheat midge is a serious problem, then insecticides should only be sprayed early before the crop has headed out. Once the crop has headed out, the midge has already laid eggs and it is too late for control. As well, the beneficial wasps are more active at this time.”

In the few situations where cereal leaf beetle may reach threshold levels, growers should leave an untreated refuge area, such as near a pond or coulees, and hope that

the parasitoid will survive there. Where wheat stem sawfly is a problem, growers are recommended to leave stubble as high as they can to allow the beneficial wasp to overwinter and have enhanced survivorship.

These research projects show that insecticides can be integrated with biocontrol agents. Where possible, growers should avoid spraying insecticides at all, but if necessary, then they can follow a few simple recommendations to try to enhance the survivorship of the beneficial insects.

“Sometimes when growers see insect pests they may think they have a serious problem. But in most cases, by spraying an insecticide when the pest is not at threshold they are probably just doing a disservice in the long run,” says Cárcamo.

“If they can avoid using insecticides, they can improve the conditions for beneficial insects and protect their yield at the same time. Beneficial insects can play a key role in integrated pest management strategies and provide growers with a long-term economical and environmentally friendly option for dealing with pests.”

The fungi-based bioherbicide naturally counters many of agriculture’s key broadleaf weeds.

by Madeleine Baerg

Twenty years after realising they might be onto something, a small team of Saskatoon-based scientists is working towards clearing the final regulatory hurdles to gain approval for Canada’s first-ever prairie cropland bioherbicide. Designed to counter some of agriculture’s toughest broadleaf weeds, including Canada thistle, dandelion and wild mustard, the breakthrough product is safe, effective and – most noteworthy – derived from an entirely natural fungus. The bioherbicide represents a major step towards diversifying Canadian agriculture’s weed management options.

“It’s a really good product. But just as importantly, we’ve made major steps to advance the field of bioherbicides, which opens the door for others to advance the field further,” says team lead Dr. Karen Bailey, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). “Industry, farmers and the research community will herald this as a big win, absolutely.”

The next-best thing to no weeds in a field is weeds that emerge from the ground a sickly, photobleached white, doomed even

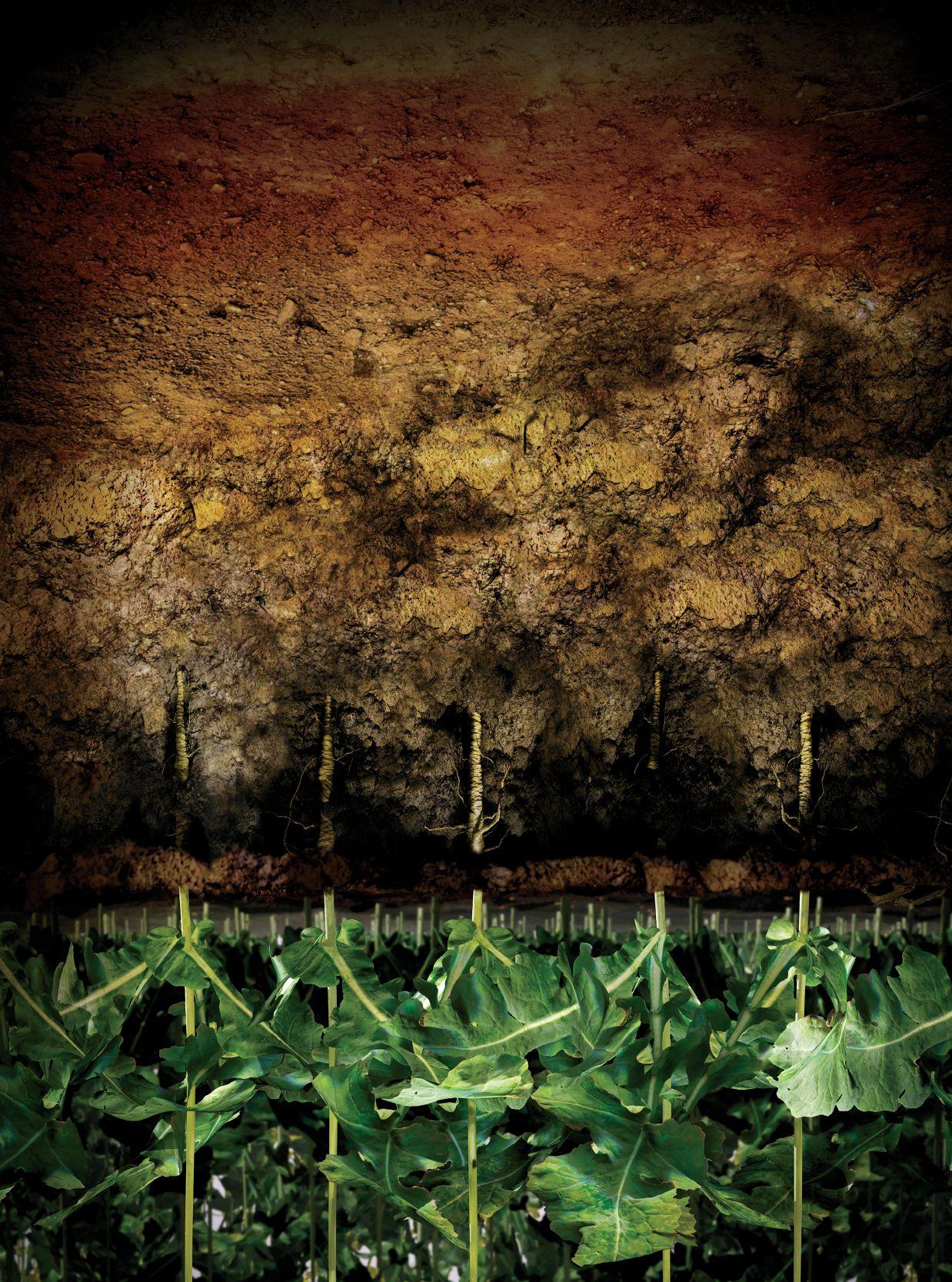

as they are just getting started. This is the magic of Phoma macrostoma. When isolated, concentrated, granulized and broadcast on fields for pre-emergent weed control, this naturally occurring fungus packs a two-part punch. First, it releases a phytotoxin that, when absorbed by germinating seedlings, destroys the seedling’s ability to feed themselves. Meanwhile, it infects the susceptible weed’s root structure, producing further phytotoxin from inside the plant. Phoma offers 50 to 80 per cent control of Canada thistle and 80 to 90 per cent (equal to conventional herbicide) control of dandelion and wild mustard.

From a safety perspective, Phoma is everything regulators and farmers want in a herbicide. It is extremely non-competitive in the soil, which means that if any other organism comes near it, its population drops sharply back to naturally occurring, virtually undetectable levels. It stays neatly in place: its effective radius

ABOVE: Test plot five weeks after broadcast application of granular Phoma macrostoma to soil.

is within five centimetres of where it was broadcast, so there is no concern with drift to neighbouring fields or waterways. It has a broad host range: it attacks many dicots (clovers, lentils, other broadleaf plants) but monocots (grasses, cereal crops) and all trees and shrubs are very resistant. Interestingly, alfalfa is susceptible in its year of establishment, but untouched if the Phoma is applied in subsequent years. And, regulatory approval is far simpler because Phoma already exists all across Canada (likely tagging along to Canada from the United Kingdom when Canada thistle was first brought in with animal hay by early pioneers).

Phoma’s application as a bioherbicide came to be through painstaking study, educated guesswork and serendipitous luck. Bailey and her team first decided to attack the problem of Canada thistle in the early 1990s. Their initial approach was to cast their nets widely: they asked agronomists and researchers across the country to send in any Canada thistle plants showing evidence of disease. The team then analyzed the sick looking plants to isolate which organisms were causing the symptoms.

Bailey isolated Phoma macrostoma as an agent of Canada thistle disease in 1994, but the research had, in fact, only begun. Though tests proved Phoma caused the plant to become diseased, when the fungus was isolated and sprayed onto the leaves of healthy plants, only partial results occurred, not nearly effective enough to suggest a real future as a bioherbicide.

But then luck stepped in, says Bailey. A dandelion growing alongside the test area flowered and, by complete accident, the seeds fell into a pot that held a plant that had been treated with the fungus. When the dandelion seeds sprouted in the pot, the emerging seedlings were white.

“That’s when we realised it had to be applied to the ground as a pre-emergent. It really was a chance occurrence - serendipity if you will - but it was the crucial step we otherwise would have missed,” she says.

The team then set about finding the most effective isolate of Phoma macrostoma and, by the early 2000s, had enough data to patent the effect of the organism. Since then, they have been working with industry partners to isolate and produce Phoma and to collect the multiple years of data on multiple crops required by regulators. They also continue to work on perfecting their product.

“Yes, it is naturally occurring, but what we are doing is maximizing what it produces for phytotoxin so we can reduce the level that needs to be applied to achieve effective results. Bioherbicides tend to be on the more expensive side, so we’re trying to maximize its effectiveness. Right now we’ve got costs reasonable for a turf grass situation, but we’re not quite there for agriculture. We’re working on different ways to grow it better, different formulations to help it disperse most effectively,” says Bailey.

While Phoma is best applied on pre-emergent seedlings, it can also provide effective control of more mature plants. However, to achieve control on older weeds, Phoma needs to be applied more than once and at higher quantities, a serious challenge to its cost effectiveness in a commercial application.

Phoma is currently registered for use in turf grass applications. Registration for feed and food use, the registration required to allow the bioherbicide to be used in prairie crops, is still three to four years away. The researchers intend to collect a final year of field data before submitting their findings to an 18- to 24-month long regulatory approval process.

If it gains final approval, Phoma will be the first of many bioherbicides developed for use in Canadian agriculture, says Bailey.

“Bioherbicides are pretty unique. Our group in Saskatoon is the only one in Canada and some of just a handful of researchers around the world looking at bioherbicides,” she says.

“We’d like bioherbicides to become a mainstream way of control. I don’t see them as better to conventional herbicides. But, they are another option and one that might suit some farmers’ needs. And, bioherbicides are usually a little better at fending off herbicide resistance due to multiple modes of action, compared with conventional herbicides which only have single modes of action, which may become increasingly important.”

Following final data collection, the next priority is to find a suitable industry partner to take the product to market. Bailey anticipates such a partner stepping in once the data collection phase is complete and the team is ready to move into the regulatory approval process.

Industry support for the product is strong. Certainly organic producers will be particularly enthusiastic should this product hit the market, as it may prove the long-awaited, all-natural solution to the growing and very challenging Canada thistle problem. That said, bioherbicide research is currently on the fringes of agricultural study, which means that research dollars can be harder to access than if the field of study were more conventional.

“The problem we have as researchers who work on bioherbicides is that we have to work in a very isolated manner. Most researchers working on conventional products can form clusters with industry to generate research dollars. But, because industry really isn’t involved at the early stages of bioherbicide development, it’s more of a struggle to find research dollars. We do get dollars from government and from producer groups; we are well supported. But I’m a researcher; we always need money.”

Certainly, other challenges lie ahead. However, most of the biggest steps en route to commercializing Phoma are now complete, a major accomplishment for the researchers and for Canadian agriculture as a whole.

“Proving all of the biology and safety finding economical ways to grow it, manufacture it, and distribute it, there are many pieces to the puzzle,” she says. “But it has come together for us, perhaps against the odds.”

Growers can’t stop talking about its ushing weed control. ( Please accept our apologies. )

If you’ve been anywhere within earshot of a grower who’s used Ares™ herbicide for Clear eld® canola, you’ve already heard all about it. A lot. Because only Ares controls the toughest ushing weeds and keeps them from coming back. Which means you save time and money in the process. So try it for yourself. Once you see the result, we doubt you’ll be able to keep it to yourself. To nd out more visit agsolutions.ca/clear eldcanola or contact AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273).

Always read and follow label directions. AgSolutions

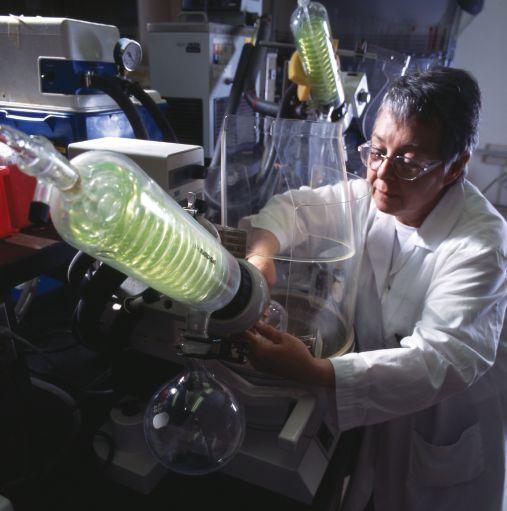

Nu-Trax™ P+ fertilizer puts you in charge of delivering the nutrition your crops need for a strong start.

Nu-Trax P+ features the right blend of phosphorus, zinc and other nutrients essential for early-season growth. And because Nu-Trax P+ coats onto your dry fertilizer you are placing these nutrients close to the rooting zone where young plants can easily access them, when they are needed most.

Takecontrolofyourcrop’searly-seasonnutritionwith Nu-Trax P+ and visit ReThinkYourPhos.com.

The short answer is yes – but complex challenges abound.

by Donna Fleury

Improving cold tolerance and winter hardiness of cereal crops for the Prairies continues to be a priority for plant breeders. Although advancements have been made over the years, breeders are still looking to solve this complex and challenging puzzle. The goal of developing super hardy winter wheat is attainable, but accomplishing it is not going to happen easily.

“The short answer is yes, developing super hardy winter wheat is possible,” says Dr. Brian Fowler, professor in the department of plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan. “We have evidence with winter rye, which is a very close relative and has genetic systems that are not much different from wheat. However, we continue to be challenged with trying to move cold hardiness genes from one species to another.”

Triticale is an example of a successful hybrid developed by crossing wheat and rye. Fowler explains that moving the genes to develop hybrids is not that difficult, except for traits such as cold hardiness. So far, the triticale hybrids developed always express the cold hardiness of the wheat parent, while the rye parent cold

hardiness genes remain completely suppressed. Breeders continue to look for tools and solutions to get the rye cold hardiness genes expressed in their selections.

“We have tried different approaches over the years using more conventional technology and have identified the major genes and their location,” explains Fowler. “The cold hardiness genes are located on the long arm of chromosome 5A in wheat and 5R in rye. We have tried various strategies including substituting the complete 5R chromosome into wheat, but have been unable to get the rye cold hardiness expression. The similarity of genetic systems suggests that the differences in the cold-hardiness potential of species is due to differences in gene regulation rather than the presence or absence of cold hardiness genes.”

The next step for breeders is to try to determine what is caus-

ABOVE: The winter survival of Puma rye (two plots that are very green) was superior to other less hardy cereals. Photo taken May 20, 2009.

ing the suppression of the rye cold hardiness gene. Researchers are assessing the gene expression in hybrids and studying the cold hardiness gene sequencing in both wheat and rye. They are hoping the comparisons will provide clues to the cold hardiness gene expression.

“Molecular technologies are advancing rapidly and are helping us to find some answers,” says Fowler. “However, wheat is complex because it is a hexaploid and has three genomes that are closely related, making it difficult for molecular sequencing programs to differentiate between the three genomes. There is still a lot of difficulty in this process and is not something that is going to happen easily.”

If breeders are successful in identifying the differences between cold hardiness of wheat and rye at the molecular level, then they may be able to focus on up-regulating certain genes in wheat and produce cold tolerance that way. “We are focusing on trying to learn more about cold hardiness within the wheat gene pool and to improve selection techniques so we will at least have better ways of maintaining maximum cold hardiness in the wheat breeding programs,” explains Fowler. “The ultimate solution would be to move cold hardiness genes into wheat from rye, or to tweak the cold hardiness in wheat to up-regulate the cold hardiness genes so wheat can respond better to low temperatures.”

Winter and spring wheat types have different strategies for acclimating to cold temperatures. Some of the very cold hardy winter varieties such as rye can start to cold acclimate once temperatures begin to fall below about 18 C, while hardy winter wheat starts at 15 C. Spring types also have an acclimation system that

responds to low and sudden drops in temperature, however they do not activate at as warm a temperature. For example, some tender spring barley types won’t begin to acclimate until temperatures fall below 5 C, which isn’t always quick enough to respond if early growing season frost occurs.

For breeders, the goal of producing superior wheat varieties with improved cold tolerance traits continues. Winter varieties with improved cold tolerance would extend the growing season, increase crop moisture utilization, improve crop competitiveness and increase yield potential. However, these crops have complex genetic systems, and improvement in cold tolerance still needs to be combined with other important agronomic attributes for growth and yield performance, disease resistance and quality.

“Breeders have been working on this challenge for many years, and although our understanding has increased and molecular technologies have improved considerably, we still don’t know what the best approach is,” says Fowler. “These new molecular technologies are quite complex and specialized, and the expertise is located in different places. We are working with other researchers at the University of Saskatchewan, the National Research Council, USDA, the University of Quebec and companies from Europe to advance our understanding of these complex systems. There is no silver bullet, but we expect over the long term to be able to achieve our goal of developing super winter hardy wheat varieties and other cereals such as barley.” For more on wheat breeding, visit www.topcropmanager.com.

Proactive project aims to ensure Prairie oats remain safe, healthy and trusted.

by Carolyn King

Anew project will be filling some information gaps on problem fungi so Prairie oat growers and processors can continue to produce safe, healthy products. The project is targeting Fusarium and Penicillium fungi. Under certain conditions, these fungi can infect cereal grains and other products and may produce toxins, referred to as “mycotoxins.” And those mycotoxins can cause food and feed-safety issues.

The Canadian Grain Commission’s Dr. Sheryl Tittlemier, who is the lead researcher for the project, explains that Fusarium infections start in the field. Warm, moist conditions during flowering favour development of Fusarium head blight (FHB). Along with the potential for producing mycotoxins, FHB reduces grain yield, grade and quality.

Several species of Fusarium can cause FHB in cereals. According to Tittlemier, the two major species of concern for oats on the Prairies are Fusarium poae and Fusarium graminearum; as well, Fusarium avenaceum is found occasionally. Fusarium poae produces various mycotoxins, such as nivalenol. Fusarium graminearum’s mycotoxins include deoxynivalenol (DON), the most common mycotoxin associated with FHB. Fusarium avenaceum produces several mycotoxins, which are just beginning to be studied by scientists.

In Canada, Penicillium verrucosum is the fungal species of concern in the production of a mycotoxin called ochratoxin A (OTA). Infection by this fungus and production of OTA occur during grain storage if temperature and moisture levels are too high. Affected kernels cannot be detected by the human eye or optical scanners.

According to Tittlemier, it is not yet clear whether Fusarium and Penicillium fungi might be less or more of a concern in oats than in other cereals. And it’s also not clear whether the occurrence of these fungi on the Prairies might be increasing or decreasing over time.

“We see variations from year to year, which is not surprising because there are a lot of factors involved in the infection and mycotoxin production. But when we look at our long-term monitoring data, it’s really hard to discern whether there is an overall trend,” notes Tittlemier, who is a research scientist and

A new study aims to help ensure that Prairie oat growers and processors can continue to produce safe, healthy products.

the program manager for trace organic and trace element analysis at the Grain Research Laboratory of the Canadian Grain Commission (CGC).

She thinks the reason these fungi are becoming more of a concern could be because of the increased regulatory activities regarding their mycotoxins. “Health Canada in recent years has proposed guidelines for ochratoxin A in cereals including oats.

Operate

Cover

sample preparation to clean grain samples for analysis of mycotoxins and fungal biomass.

And internationally, with the Codex Alimentarius [a collection of international food standards, guidelines and codes of practice], there is discussion about establishing new tolerances for DON in various cereals. So I think this is bringing these two mycotoxins into people’s minds.”

The importance of this issue to the whole oat industry is

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. Commercialized products have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from this product can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for this product. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready® crops contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for canola contains the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil, and thiamethoxam. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for soybeans (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin and metalaxyl. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for soybeans (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin, metalaxyl and imidacloprid. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin and ipconazole. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, and clothianidin. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn with Poncho®/VoTivo™ (fungicides, insecticide and nematicide) is a combination of five separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, clothianidin and Bacillus firmus strain I-5821. Acceleron®, Acceleron and Design®, DEKALB and Design®, DEKALB®, Genuity and Design®, Genuity®, RIB Complete and Design®, RIB Complete®, Roundup Ready 2 Technology and Design®, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready®, Roundup Transorb®, Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup®, SmartStax and Design®, SmartStax®, Transorb®, VT Double PRO® and VT Triple PRO® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC. Used under license. LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. Herculex® is a registered trademark of Dow AgroSciences LLC. Used under license. Poncho® and Votivo™ are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

shown by the diverse participants in the project. Tittlemier says, “The project is bringing together the Prairie Oat Growers Association with their support, the support of the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, the elevators and the mills that are providing us with samples, and the Canadian Grain Commission. And within the CGC, there’s my research group, the microbiology research group, and the milling research group, and inspectors are helping us with obtaining samples and the logistics of the samples. I think it’s going to benefit the project that we have all these players coming in from different aspects of the oat industry.”

The Prairie Oat Growers Association (POGA) is administering the three-year project, as well as co-funding the project with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture’s Agriculture Development Fund.

“This project is an important step in ensuring that Canadian oat producers can continue to provide safe and healthy products that are trusted around the world,” says Shelanne Wiles Longley, POGA’s interim executive director.

“We’re starting to see increasingly rigorous testing of oats and oat products, especially in Europe. So it’s really important, more so now than ever, to be proactive in this area,” notes Longley. “For example there is a proposed trade agreement between the European Union and Canada, and that market is likely going to require testing for mycotoxins in oats and other products.”

She adds, “If ever a problem arose with mycotoxins, it could drastically limit the export market and the uses of oats, which could then have drastic effects on oat producers.”

“This project is going to fill some knowledge gaps, giving us a better handle on what is the current situation about where we find the fungi, where we find the mycotoxins, and what happens to them when we process the oats,” says Tittlemier.

The project has two main parts. One part involves disease surveillance, to see if there are any patterns in where and when the fungi and their mycotoxins occur. The other part will exam -

ine processing effects on the fungi and their mycotoxins.

To carry out the first part, the researchers will receive oat samples from elevators across the Prairies in the summers of 2014, 2015 and 2016. In addition, they’ll be getting weekly samples over the three years from elevators that consistently handle oats throughout the year and from a mill that takes deliveries throughout the year. The researchers will analyze these samples to see if there are differences from region to region, from summer to summer, and/or from week to week within the year.

“Knowing the [disease occurrence] situation and providing that information to oat growers and grain handlers can help them to be proactive to prevent problems. For instance, if certain regions have more disease pressure, then they may have to take extra management steps, perhaps through agronomic practices, or maybe the grain elevators need to be more aware of proper testing to make sure they’re not running into issues with high levels of mycotoxins in deliveries,” explains Tittlemier.

mycotoxins in the various product streams,” says Tittlemier.

The researchers are already working on sample testing procedures. She notes, “In our labs we’re using validated testing methods, so we’re confident with the tools we have. But there are challenges with oats. For example, oats have a higher fat content than other cereal grains, so a test that you use for wheat may not work for oats in the same way.”

Another testing challenge, especially for Penicillium and ochratoxin A, is how to obtain representative samples. That’s because the contamination tends to occur in only a small pocket within the grain mass. Tittlemier explains, “You need to ensure the sample that you’re testing in the lab is representative of the bin or the truckload or the railcar or what have you. So you have to do the sampling properly to make sure you’re not missing that little pocket of contamination.”

Processes like dehulling, steaming, kilning and milling could affect the presence of the fungi and their mycotoxins, depending on where on the seed the problem occurs.

For the other part of the project, the researchers will assess the effects on the levels of the fungi and their mycotoxins of sample processing methods for testing and of commercial processing techniques.

“We’ll work with the milling group at the Grain Research Laboratory and look at how processing of oats – whether it is for sample preparation or commercial processing with dehulling, steaming, kilning and so on – might affect the fungi and

Processes like dehulling, steaming, kilning and milling could affect the presence of the fungi and their mycotoxins, depending on where on the seed the problem occurs. Tittlemier says, “We know for wheat that some mycotoxins occur on the outer seed coatings. And from some preliminary tests we know that if you dehull oats, the mycotoxin concentrations can be greatly reduced. However, some other mycotoxins with different chemistries might actually make their way into the kernel.”

Information from this part of the project could help testing facilities ensure accurate, precise results. It could also help oat processors to have a better understanding of the effects of different processing methods. And it could help food safety regulators, too. Tittlemier explains, “Whether it’s Health Canada or international groups, when they go to set maximum limits or guidelines for oats, they can take into account these steps that could reduce exposures, so they can set relevant limits.”

by Bruce Barker

There was a time when a wheat/fallow rotation was common on the Prairies, but that practice has caught up to us. Farmers in the Brown and Dark Brown soil zones are paying for the sins of our ancestors. Little did our ancestors, and the “experts” of that era, know they were mining the soil and that summerfallowing would eventually deplete Prairie soil of its organic matter and nitrogen fertility.

“The short answer is that we have mined our soils of organic matter, and if you are growing crops on summerfallow, you now have to apply nitrogen fertilizer,” says Rigas Karamanos, of Koch Fertilizer Canada at Calgary, Alta.

Back when Prairie soils were undergoing conversion to cropland, they were considered to be some of the most fertile and rich in organic matter soils in the world, with organic matter content as high as 16 per cent. By the late 1930s and early 1940s, organic matter had already begun to decline. In 1993, Karamanos, then at the Saskatchewan Soil Test Laboratory, found that soil tests showed a 25 to 75 per cent decline in average soil organic matter levels compared to 1945 levels. And with those declining organic matter levels came a dramatic reduction in mineralizable N in the Dark Brown and Brown soil zones, impacting nitrogen (N) fertility on crops grown on summerfallow.

Today, most soil test labs take N mineralization and immobilization into account when providing fertilizer recommendations. How-

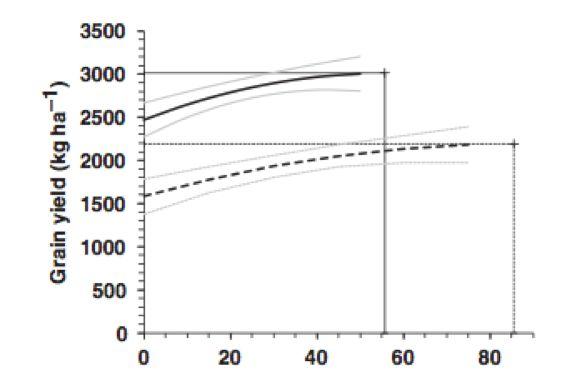

ever, crops grown on summerfallow may be under-fertilized because of the depleted organic matter levels in the soils. To test this theory, Karamanos looked at research results found in the Westco database in a three-year trial in Saskatchewan and Alberta from 2003 to 2005. While the trials are 10 years old, Karamanos says the results are still valid today. He published the research in the Canadian Journal of Plant Science in November 2012.

“We knew that crops grown on fallow were responding to nitrogen, but didn’t have much information on the most efficient nitrogen fertilizer rates, on these depleted soils” says Karamanos. “Being able to look at the trials gave us a good indication of the nitrogen response rates on fallow.”

The objectives of this study were to determine yield, quality, N use, and water and N use efficiency of canola and wheat grown on fallow with different rates of N fertilizer. There were six sites initially established – three in Alberta and three in Saskatchewan. The Saskatchewan sites were maintained throughout the three years, but the Alberta sites were reduced to two in the third year and relocated to two different locations. The sites varied from sandy loam to heavy clay soils and ranged in organic matter content from 1.1 to 3.2 per cent.

ABOVE: Summerfallow acres yield the best with the addition of nitrogen fertilizer.

Take charge of resistance by making Liberty® herbicide a regular part of your canola rotation. As the only Group 10 in canola, powerful Liberty continues to effectively manage all herbicide resistance concerns for Canadian growers. Unlock the yield potential of your InVigor hybrids with the exceptional weed control of Liberty.

Karamanos, R. E., Selles, F., James, D. C. and Stevenson, F. C. 2012. Nitrogen management of fallow crops in Canadian prairie soils. Can. J. Plant Sci. 92: 1389-1401.

Two wheat varieties, AC Superb and AC Eatonia, were sown, and Liberty Link InVigor canola hybrids were grown (InVigor 2573 and Invigor 2733). Six N fertilization treatments were applied, as follows: 0, 9, 18, 27, 36 and 45 lb N/ac (0, 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 kg N/ha) for wheat, and 0, 14, 27, 40, 54, 68 lb N/ac (0, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 75 kg N/ha) for canola. Nitrogen treatments were side-banded at seeding one inch to the side and one inch below the seed with a Stealth opener. All trials received a blanket application of seedplaced P2O5 as triple super phosphate (0-45-0) at a rate of 27 lb/ac (30 kg/ha), and K2O and S as potassium sulphate (0-0-51-17) at a rate of 45 and 15 lb/ac (51 and 17 kg/ha), respectively. All treatments were replicated four times.