Pest

Flea

Economic

Conserving

Budgeting

Soybeans

Pest

Flea

Economic

Conserving

Budgeting

Soybeans

by Kaitlin Berger

I’ve always felt an equal mixture of intrigue and annoyance over insects. Growing up on a pig farm, there was an endless war happening between my family and the house flies that would encroach the boundaries of the kitchen and dining room. Their presence would be met by sticky traps, fly swatters, fly spray and – at one point – a fly gun. Some summers, the frustration was so great, you really had to watch you weren’t in the line of fire if someone picked up the fly swatter. But my disdain for house flies was equally matched by my fascination for the insects you’d find in the soybean, corn and wheat fields surrounding our farmhouse.

In fact, one year, my mom set out to teach me about bugs. She got me a fancy insect collection box, some pins and showed me how to make a jar that would both kill and preserve what I captured in my butterfly net. It was a gruesome exercise, but extremely educational. And it was, perhaps, my first glimpse into the power of insects to both add to the health of a crop or damage it.

Cabbage seedpod weevil was found in high numbers last year...

While my insect collection is long gone now, I’m still keeping an ear to the ground on which insects are causing some buzz on the Prairies each year. According to a 2025 survey in canola growing areas of southern and central Alberta, completed by the Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation Plant and Bee Health Surveillance Section staff, cabbage seedpod weevil was found in high numbers last year – above economic levels as far north as Red Deer County – so it’s something to continue to scout for in 2026 in south and central Alberta, as well as southwestern Saskatchewan.

In this issue, you’ll also find some helpful updates on both beneficial insects and insect pests. On page 22, there’s some tips for preserving beneficials. On page 12, you’ll read how understanding economic thresholds and beneficial insects can help minimize losses from cereal and pea aphids. You’ll also learn how soybean gall midge is creeping closer to Canada – on page 6. How much do insect pests cost Prairie farmers? Top Crop Manager columnist and field editor, Bruce Barker, dives into some estimates on page 26.

When it comes to managing these insect friends and foes in the field, the more information, the better. Same goes for fly swatters – the more the better – unless you’re in the line of fire.

Editor KAITLIN BERGER (403) 470-4432 kberger@annexbusinessmedia.com

Western Field Editor BRUCE BARKER (403) 949-0070 bruce@haywirecreative.ca

National Account Manager QUINTON MOOREHEAD (204) 720-1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

National Account Manager REENA UPPAL (437) 922-7359 ruppal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Account Coordinator JULIE MONTGOMERY (416) 510-5163 jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher MICHELLE BERTHOLET (204) 596-8710 mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Coordinator LAYLA SAMEL (416) 510-5187 lsamel@annexbusinessmedia.com

Team Lead/Media Designer BROOKE SHAW

CEO SCOTT JAMIESON sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

@TopCropMag

@topcropmanager

@TopCropManager

It’s time to turn the page on the past and welcome in a new era. One where growing better quality, higher-yielding cereals isn’t just an end goal—it’s a given. Miravis® Era fungicide brings together the power of ADEPIDYN® and the timetested effectiveness of prothioconazole to provide the pinnacle of protection against Fusarium head blight.

A golden era for your cereals? Explore yield results.

To learn more about Miravis® Era fungicide, visit Syngenta.ca, contact our Customer Interaction Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682), or follow @SyngentaCanada on Social Media.

Always read and follow label directions. Miravis®, the Alliance Frame, the Purpose Icon and the Syngenta logo are trademarks of a Syngenta Group Company. © 2026 Syngenta

The new pest has been confirmed in southern North Dakota.

BY BRUCE BARKER

There are a lot of unknowns surrounding the soybean gall midge (Resseliella maxima). It has been identified in the United States Midwest, and is known to occur in Iowa, Missouri, Minnesota, Nebraska, Kansas, North Dakota and South Dakota. Whether it makes its way to Canada, and whether it can survive and cause damage to soybeans, is unclear.

“To my knowledge, there have been no sightings or reports of soybean gall midge in Canada, or the Prairie provinces,” says Meghan Vankosky, an entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Saskatoon, Sask. “Researchers in the U.S. think that it was present for nearly a decade before they were able to identify it, so there is a chance it is here and we do not know about it. This is one reason we highlighted this insect as a potential threat to Canadian agriculture; it is known to occur close by and is difficult to detect.”

Soybean gall midge was first discovered in Nebraska, Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota in 2018 when it was determined that it was a new species infesting soybean fields. Since then, it has expanded its range in all directions, and is mostly found in these states near the Red River. It was confirmed in Sargent Township in southern North Dakota in 2022. Since its discovery, it has been found in at least 140 counties in the United States.

Soybean gall midge larvae overwinter in the soil. In early spring, the insect pupates and emerges as adult flies. The tiny adult flies are about 5 millimetres (mm) long with grey or black-coloured bodies and black legs with white or yellow-coloured stripes. They live three

ABOVE Wilting damage caused by the soybean gall midge.

to five days. The adults are difficult to find and identify.

Soon after emerging, the female adult flies lay eggs in natural openings or wounds on lower stems and bases of soybean plants around the V2 or V3 growth stage. Once the eggs hatch, the tiny larvae, which resemble maggots, feed on stem tissue interrupting the flow of nutrients and water. Young larvae are clear to white, and turn bright orange at maturity. Once mature, the larvae fall to the ground and pupate in the soil. In the midwestern U.S., three generations have been observed during the growing season.

Symptoms of feeding damage first show up as dark, discoloured areas near the larval feeding site. Because the flow of nutrients and water is interrupted, stems can become withered and weak. The stem may break off at the base of the plant. High infestation levels can result in the plant wilting and dying.

Infestations often show up at the borders of fields close to where soybean was planted the previous year.

The adults are weak fliers, and feeding damage decreases further into the field. In research in Nebraska, up to 100 per cent yield loss was observed in the outer 50 feet (15 metres) of affected soybean fields.

Currently, there are no recommended management practices to control the pest.

It is probably wishful thinking, but soybean gall midge might not survive Canadian Prairie winters. Canadian winters are too severe for some other invasive pests that die off in the fall and re-invade in the spring.

“It is possible that it could overwinter on the Prairies; maybe in more humid areas such as southern Manitoba where the climate is more similar to the Midwest, but we do not know for sure,” says Vankosky. “Hopefully new research from the U.S. will help us to better understand the risk of its establishment in Canada.”

Another unknown is whether the pest

could go through three generations on the Prairies, as it has done in the U.S. Midwest. “I think this would depend on the weather. The life cycle of soybean gall midge seems to be similar to that of swede midge and canola flower midge, where multiple generations are possible, depending on how warm it is and how long the growing season is. More research is needed to know for sure, though,” says Vankosky.

But even if it can’t go through multiple generations in one growing season, the first generation is the one that most likely causes the damage. Research at the Eastern Nebraska Research, Extension and Education Center found that later infestations at the full flower stage (R2) did not significantly impact soybean yields if the plants were not previously infested.

John Gavloski, an entomologist with Manitoba Agriculture, adds that even though the insect hasn’t been confirmed on the Prairies, growers and agronomists should still be on the lookout for it. “It is still good for those scouting soybeans to

be aware of what soybean gall midge larvae look like, as well as the lesions they can cause at the base of the plant,” says Gavloski. “If soybean gall midge is suspected, they should contact their provincial entomologist, so samples can be collected, and the identification verified.”

Vankosky says that AAFC entomologists are also interested in receiving photos and samples of suspected soybean gall midge. She says there are resources in the U.S. like the Soybean Gall Midge Alert Network and the iNaturalist page that Prairie farmers can use to follow what is happening with this insect.

Gavloski says farmers and agronomists scouting for soybean gall midge should also be aware of a similar looking gall midge. “There is another gall midge that can be present on soybeans called the white mold gall midge (Karshomyia caulicola). It looks similar to soybean gall midge, but feeds on white mold fungus growing on the plant, is not a pest of soybeans, and occurs in Manitoba,” says Gavloski.

is a tool to help estimate nitrogen fertilizer rates.

BY LEEANN MINOGUE

Deciding how much nitrogen (N) to apply next season involves math, economics and a crystal ball. Miles Dyck, soil science professor at the University of Alberta, has raised some eyebrows by saying farmers can base their fertilizer budgets on average yields, rather than optimistic, best-case yields.

Dyck started looking into this after a call from his collaborator, Linda Gorim, assistant professor and Western Grains Research Foundation (WGRF) chair in cropping systems at the University of Alberta. Gorim heard farmers were looking for guidance on how to adjust their fertilizer rates for the next growing season after Alberta’s 2021 drought.

While Dyck and Gorim knew the answer – that the crop takes up less N in dry years and more is left over the next year, so growers wouldn’t need to apply much – they didn’t have hard data. “We wanted concrete examples

that we could show producers,” says Dyck. They considered field research, but it would be difficult to plan. “It always rains when you don’t want it to.”

Then Dyck remembered the Alberta Farm Fertilizer Information and Recommendations (AFFIRM) model developed by Len Kryzanowski and Symon Mezbahuddin at the Alberta Ministry of Agriculture. AFFIRM is an online application for estimating fertilizer rates. It’s built on a province-wide data set, including plot-scale experiments done by Alberta Agriculture in the early 2000s. The most recent version includes results from recent studies of controlled-release fertilizers (CRFs), as well as release of nutrients from manure.

Dyck realized they could extract more information about N rates from AFFIRM’s existing database. “I thought maybe this is something we can do virtually, rather than doing a really expensive field experiment where a lot can go wrong.” Dyck and Gorim’s graduate

The emulsi able concentrate formulation of Varro® FX mixes quickly and thoroughly so you can get in your wheat elds sooner. Varro FX controls your toughest weeds including Group 1-resistant wild oats and other grass weeds.

See if Varro FX is a t for your farm at ExpertControl.ca

Higher flea beetle pressure – and highest yield – comes with earlier seeding.

BY BRUCE BARKER

When it comes to flea beetles, canola growers are continually looking for that Goldilocks’ moment when it comes to seeding rate and date. Seed too early and seed treatment effectiveness may decline and be overwhelmed by flea beetles. Seed too late and yield is left on the table even though canola will rapidly germinate and potentially outgrow flea beetle infestations. A demonstration project at four Agriculture Applied Research Management (Agri-ARM) sites in Saskatchewan looked into the effect of canola seeding date and rate on flea beetle pressure, yield and quality.

“The project was identified as high priority by SaskCanola board of directors,” says Brianne McInnes, operations manager at the Northeast Agriculture Research Foundation (NARF) at Melfort, Sask.

The Agriculture Demonstration of Practices and Technologies (ADOPT) project funded by SaskCanola was conducted in 2024 at four Agri-ARM sites including NARF in Melfort, Wheatland Conservation Area (WCA) in Swift Current, Western Applied Research Corporation

ABOVE In this ADOPT project, the highest yield came with earlier to typical seeding dates despite higher flea beetle pressure.

(WARC) in Scott and Irrigation Saskatchewan (ISask) in Outlook, Sask. The Outlook site was irrigated. Five seeding dates were compared with the actual seeding date varying by location and environmental conditions. These included ultra early (last week of April to first week of May), early (first two weeks of May), typical (mid- to late-May), late (very end of May to first week of June) and very late (early to mid-June). Typically, each seeding date was about 10 days later than the previous one.

At the three dryland sites, the two seeding rates were four seeds/ft2 (40 seeds/m2) and eight seeds/ft2 (80 seeds/m2) with an expectation of 50 per cent seedling mortality. At the irrigated Outlook site, the 1X rate was 10 seeds/ft2 (100 seeds/ft2) and the 2X rate was 20 seeds/ft2 (200 seeds/m2).

Typical crop management was conducted regarding weed, insect and disease control, and fertility programs. Canola seed was treated for flea beetle control. Flea beetle damage was evaluated on 20 plants in two locations per plot when the second leaf was visible, but not

unfolded. Growing season conditions in 2024 saw a cool and wet spring followed by a hot and dry summer.

Ultra early seeding dates had the longest days to emergence, with days to emergence becoming shorter with later seeding dates. For example, at Swift Current and Melfort, days to emergence for ultra early seeding was over 20 days, with a steady decline to 10 to 11 days for the latest seeding date.

Plant stand establishment averaged 6.8 plants/ft2 at Melfort, 5.4 plants/ft2 at Swift Current and 7.6 plants/ ft2 at Scott. Post-harvest stubble counts at Outlook averaged 13.2 plants/ft2. Seeding date significantly affected plant density, but was inconsistent across sites, indicating that environmental conditions at each site were more important than seeding date. Generally, though, ultra early seeding had consistently lower plant stands, likely because of seeding into cooler soils. As expected, increasing seeding rate increased plant stand densities.

Flea beetle damage averaged 16 per cent at Melfort, 17 per cent at Swift Current and 13 per cent at Scott. Outlook did not have any flea beetle feeding damage. Flea beetle feeding tended to be higher for earlier seeding dates, with declining damage for later seeding dates.

The highest flea beetle damage at Melfort was for the early and typical (May 6 and 15) seeding dates. Ultra early seeding (April 25) at Swift Current had significantly greater flea beetle pressure than seeding late (May 22) and very late (May 30). This ultra early seeding date with 35 per cent defoliation at Swift Current was the only site to surpass the economic threshold of 25 per cent defoliation. The Scott location continued the trend with ultra early (May 5) and early (May 14) seeding dates having the highest defoliation.

In other research by Tyler Wist with AAFC Saskatoon, seeding early was more advantageous when crucifer flea beetles were more prevalent because they emerged later in May. However, striped flea beetles have become more prevalent and appear two weeks earlier. McInnes says earlier spring snow melts and warmer spring temperatures could likely make the flea beetles active earlier in the spring than they used to be.

Flea beetle defoliation also tended to be higher for the 1X seeding rate than the 2X rate. No significant interaction of seeding date and rate at any locations was observed.

Grain yield was typically highest with early seeding. At Swift Current and Scott, grain yield decreased linearly

There are still risks with seeding early, such as higher flea beetle pressure and risk of late spring frosts...

from ultra early seeding to very late seeding. At Swift Current, ultra-early (April 25) seeding yielded 19 bu/ac (1,088 kg/ha) decreasing to 3 bu/ac at the very late seeding date. Scott had similar declines, although not as drastic, yielding 60 bu/ac for the ultra early seeding date and declining to 30 bu/ac at the very late date.

At Melfort, yield was significantly higher at the typical (May 15) and late (May 27) seeding dates, yielding around 48 bu/ac (2,672 kg/ha). Ultra early, early and very late seeding dates were statistically similar yielding 29 to 33 bu/ac (1,637 to 1,877 kg/ha).

The highest yield at Outlook was the early (May 15) seeding date at 46 bu/ ac (2,588 kg/ha). This was statistically similar to the typical (May 27) seeding date at 40 bu/ac (2,265 kg/ha) but higher than the other seeding dates.

Even though earlier seeding dates tended to have higher flea beetle pressure, McInnes explains that feeding pressure was not high enough to cause economic loss. As a result, earlier seeding, in spite of higher flea beetle pressure, still yielded high at 50 per cent of the sites.

“Flea beetle pressure was usually higher for early dates, but rarely passed the economic threshold. Considering defoliation was usually below the threshold, the effect on yield was likely negligible,” says McInnes. “Therefore, the earlier dates having higher yields at some sites were likely due to environmental conditions and not differences in flea beetle pressure.”

Seeding rate only affected yield at Swift Current and Scott, where increasing seeding rate increased yield. Yield was increased by 1.5 bu/ac (84 kg/ha) at Swift Current, and by 3 bu/ac (170 kg/ha) at Scott. There were no significant interactions of seed date and rate for yield at any sites.

“There was likely no interaction between seed date and rate for yield, as plant stands for all treatments were usually at or well above four plants/ m². When plant stands fall below four plants/m² in canola, this is where yield usually declines,” says McInnes. “If there was an instance where seeding rate resulted in differences in plant stands at different dates, resulting in having a stand of less than four plants/m², or flea beetle pressure was beyond the economic threshold, there may have been a greater chance of an interaction occurring for yield.”

Overall, McInnes says the demonstration project found that seeding canola earlier at the end of April to early May does seem to be a viable option in most locations in Saskatchewan. However, yield was not always better as compared to a typical seeding date of mid- to late-May, depending on the locations and coinciding environmental conditions.

“There are still risks with seeding early, such as higher flea beetle pressure and risk of late spring frosts,” says McInnes. “However, in areas where hot and dry conditions persist in the spring and summer, seeding early seems to be the best option.”

Understand economic thresholds and beneficial insects.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Depending on the year and timing of invasion, cereal and pea aphids can cause significant damage to crops on the Prairies. Whether growers are managing them in cereals or pulse crops, understanding economic thresholds and the beneficial insects that can feed on them will help minimize losses.

“Aphids cause damage by tapping into the phloem, sucking the juices out of the plant. They can also vector viruses and drop honey dew all over the plant, which then leads to sooty mold growth,” says Tyler Wist, entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Saskatoon, Sask.

A significant factor in how much damage they can cause is their rapid population growth under the right conditions. All aphids are born female and give birth to live young that start feeding right away. Population growth can double in five to seven days. That was evident in research trials that Wist conducted in 2013 on canary seed.

Wist compared cereal aphid populations in open and closed cages. Open cages on August 15, 2013 had 39 aphids, and closed cages had 105 aphids. Fourteen days later, the open cages had 14,395 aphids, and the closed cages had 43,816. “That is a significant number of aphids in the open cages. Though, if you look at that, there’s about one-third less aphids in the open cages. Why?” asks Wist. “The door was open, right? And who can get in the front door? Beneficial insects.”

TOP Heavy aphid pressure can cause 100 per cent yield loss.

ABOVE Pea aphids feeding on lentil flowers.

Those high aphid populations impacted yield as well. Canary seed yielded 293 pounds per acre (330 kg/ha) in the closed cages where beneficial numbers were limited, compared to 659 lb/ac (740 kg/ha) in the open cages, and 2,136 lb/ac (2,400 kg/ha) in the rest of the field.

While cereal aphids are a complex of insects, the two main pests are the English grain aphid and the bird cherry-oat aphid. Both can cause damage in cereals. Wist says that economic threshold in cereals is 12 to 15 aphids per spike, although damage probably starts to occur around 10 per spike prior to soft dough stage. For canary seed, the nominal threshold was 10 to 20 aphids on 50 per cent of stems, but Wist and Bill May at AAFC Indian Head, Sask. revised thresholds to 10 to 15

aphids per stem after a Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture Development Fund (ADF) project. Malathion and dimethoate (Lagon/ Cygon) are registered for control.

Pea aphids can similarly explode in populations and cause yield loss approaching 100 per cent. Wist has seen populations so high that faba beans drop their flowers and their leaves shrivel, leaving just the stalks and little yield.

In Ningxing Zhou’s master’s research, co-supervised by Sean Prager at the University of Saskatchewan, they compared yield at four different pea aphid populations, with and without insecticidal control. Pea aphid densities per stem comparisons were less than 150, 151 to 300, 900 to 1,000, 1,000 to 1,500, and a maximum unlimited number. The untreated faba bean yield was essentially zero. When faba bean was sprayed with either Lambda-cyhalothrin (i.e. Silencer) or Lambda-cyhalothrin plus chlorantraniliprole (i.e. Voliam Express), yield was statistically similar at densities less than 300 aphids at around 1.67 to 1.79 tons per acre (3.75 to 4 tonnes/ha). But at over 1,000 aphids per stem, even when sprayed with an insecticide, yield collapsed to almost nothing.

This research by Zhou, Wist and Prager refined the economic threshold to 34 to 50 pea aphids counted on the main faba bean stem. This provides a lead time to control pea aphid populations before they can explode and cause economic damage.

According to the Saskatchewan Guide to Crop Protection 2025, there are several insecticides registered for pea aphid control on faba bean, including Carbine, Sivanto Prime, Matador, Silencer, Labamba, Zivata and Voliam Express.

Wist also conducted research on economic thresholds for pea aphids in lentil as part of Zhou’s master’s thesis. Using a similar approach with aphid densities as was done on faba bean, they found that high pea aphid densities could crash lentil yield. “You can actually see the differences in the field. Where we sprayed, the lentils are still green, and where we didn’t spray, the crop is brown,” says Wist.

From Zhou’s work, an economic threshold in lentils of about 30 to 40 per sweep was determined. This was similar to the nominal threshold that was previously used based on research from other geographic areas. “And so we proved the nominal threshold with science,” says Wist.

In lentil, foliar insecticides registered include Carbine, Movento, Sivanto Prime, Matador, Silencer, Labamba, Zivata and Voliam Express.

Environmental conditions also impact pea aphid populations. Wist compared pea aphid populations in 2020 to 2021. On July 29, 2020, pea aphid populations were around 650 per 10 sweeps. In 2021, populations were very low. The difference was the heat dome of 2021, when average temperatures were 30 C in July, compared to 22 C in 2020.

“They cooked. We had one aphid at the start of July. We had one aphid at the end of July, which is very unusual. When you crank up the temperature to 35 degrees, like Tyler Hartl did in his master’s thesis, some of the aphids will have offspring, but the population does not do very well,” says Wist.

Pea economic thresholds were previously conducted in the 1980s and were determined to be nine to 12 pea aphids per sweep at flowering. Wist says this research should be

RIGHT Faba beans will drop their flowers; leaves shrivel under high aphid pressure.

looked at again with newer varieties that may differ in their response to pea aphid.

“When you’re looking at about nine to 12 per sweep at the flowering stage of pea, it seems pretty low, especially when lentils seem to tolerate 30 to 40 per sweep,” says Wist. “But when you consider the doubling time of the population is five days, by the time you get up to about 300 aphids on a plant, it could be getting close to total loss.”

Scan the QR code to access the Cereal Aphid App:

For Apple iTunes enabled device

For Android operating enabled device

Wist says beneficial insects can play a large role in controlling cereal and pea aphids. Braconid parasitoids, golden-eyed lacewing adults, hover flies, soft-winged flower beetle and lady beetles are some of them.

“Based on whatever life stage the lady beetle adults are at, they can eat anywhere from 50 to 85 aphids a day,” says Wist.

Wist recommends the Cereal Aphid Manager app that is available on the Apple store and Google Play. It provides information on scouting for aphids and beneficial insects, and was released in March 2018. Another resource is a publication from AAFC – Field Crop and Forage Pests and their Natural Enemies in Western Canada - that has information on insect pests, life cycles, photo identification, scouting, economic thresholds and management options.

More than just another pre-seed It’s the first product in Western post seeding application. including Group 2, 4 and 9

pre-seed option, NEW Avireo™ herbicide is the rising star in burnoff innovation. Western Canada to combine Group 27 and Group 14 for pre-seed or up to 3 days

Count on Avireo™ herbicide to take down your toughest broadleaf weeds, resistant kochia, Group 2 and 4 resistant cleavers, volunteer canola and more.

More nitrogen fertilizer is not always better | CONTINUED FROM PAGE 8

student, Chunjing Zhu, went to work. The results suggest fertilizer N rates can be reduced by 20 to 30 lb N/ac for a growing season following a dry year.

Deciding how much N to apply is like building a budget. First, growers must determine what they need, and then subtract what they already have, and add the difference. The next step is setting a target yield to use with standard crop uptake tables for each crop to estimate how much N the plants need to get to the target. Estimating the N already in the soil is more difficult. Plant-available, inorganic N can be measured by a soil test, but there’s a big reservoir of organic N that isn’t available to plants until it gets mineralized by soil microbes. This organic N is soil organic matter, crop residue, manure or compost. Once it’s mineralized, it becomes inorganic and plant-available as ammonium or nitrate.

Organic N in the field can be measured, but it’s difficult to predict the mineralization rate. This varies by soil type and texture but is mainly driven by weather. Warm, moist weather in May and June increases mineralization, resulting in more plant-available N. A cold, dry spring means less mineralization and less plant-available N.

The AFFIRM model forecasts mineralization rates for optimal, intermediate or low moisture scenarios based on user input, and either measured soil organic matter levels or average soil organic matter levels by soil-climatic zone.

Target yield is another key variable. For dryland farmers, yield is usually limited by water. If they fertilize for a high yield and it doesn’t rain, they’ll have extra N in the field.

Fertilizing for a low yield could limit yield potential if the weather gets better.

“It’s okay to be a little bit conservative,” Dyck says. “Try and fertilize to get what you think is an average or a long-term average for your field. If you end up having really good growing conditions, mineralization will compensate.” This advice is backed by the N mineralization data built into the AFFIRM model. Mineralization also supplies some phosphorus (P) and sulphur (S), but AFFIRM only focusses on N, and assumes sufficient levels of P, potassium (K) and S.

Dyck suspects some farmers may be overapplying N by often fertilizing for optimal yields. “I think there’s maybe a little bit of FOMO going on, fear of missing out on a good yield. I don’t think that’s a great way to make decisions about something like fertilizer.” Changing fertilizer yield target from “build more bins” to “reported average” is a non-glamorous tip that may help growers save money. This is where detailed farm- or field-level records come in handy.

The counterargument to Dyck’s advice is to keep adding N and letting it build up in the soil for future use. “Yes, the soil will hold most, but not all of it,” Dyck says. “If you just keep going in that building cycle, leaching and denitrification losses will increase. It’s not an efficient way to go. That lost N isn’t increasing yields and is harming the environment. That’s a good case for not applying too much.”

These research activities were sponsored by RDAR project Identification of information required to reduce risks associated with post-drought fertilizer applications , and Linda Gorim’s WGRF chair in cropping systems.

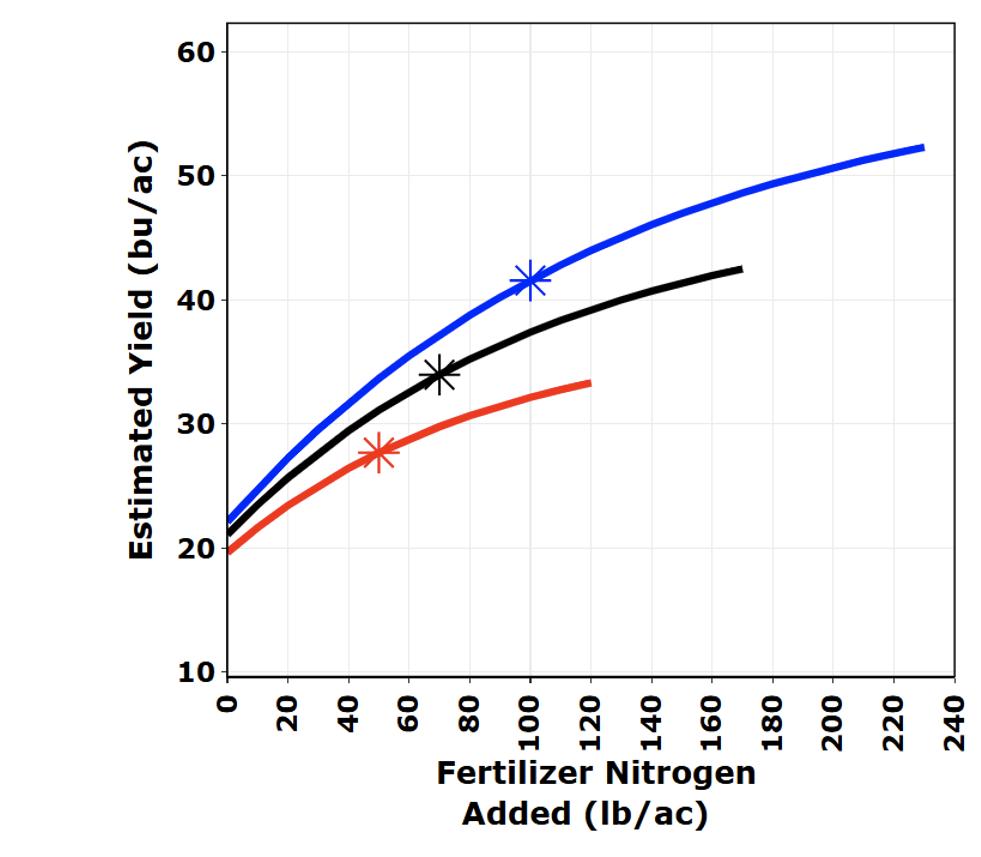

Alberta’s AFFIRM model can provide estimates for optimal N application rates. With a few input variables, the model produces yield response curves based on long-term data and research. AFFIRM accounts for available N in the soil based on soil test N, contributions from last year’s crop residues, and the expected rate of mineralization. It uses yield response curves calibrated with the Alberta database to estimate yield gains from each additional pound of fertilizer added. If soil test N isn’t available, it’s possible to estimate it using a partial N balance with last year’s fertilizer rates and crop yields.

While many farmers base fertilizer budgets on target yields, AFFIRM doesn’t even ask for that information. Instead, AFFIRM asks about fertilizer prices, and expected crop prices, and suggests a fertilizer rate that will optimize profits. This rate is shown as the asterisk on the yield curve.

Fertilizer Response Curve, Alberta’s Brown Soil Zone, Canola

Moisture Levels

Blue Line

Optimum (100 lb N/ac)

Black Line

Intermediate (70 lb N/ac)

Red Line

Low (50 lb N/ac)

For example, at the asterisk on the blue line, showing optimal moisture, applying 100 pounds of N results in an estimate of 42 bu/ac. With dry weather, 100 pounds of N yields 32 bu/ac. It’s easy to play with the mode to see different scenarios. For example, with higher expected canola prices, the asterisk will move to the right – and adding more fertilizer would increase profits.

AFFIRM lets growers set an expected return on their fertilizer investment. If they’re looking for an additional $1 in canola revenue for every extra dollar they spend on fertilizer, set the model’s Investment Ratio to one. For a $3 revenue increase for every extra dollar spent on fertilizer, set the Investment Ratio to three and expect to buy less fertilizer.

Manitoba farmers can use the Fertilizer Efficiency Calculator on the Manitoba government website. Saskatchewan farmers can look at Alberta and Manitoba models, and choose the closest soil type. “It wouldn’t be totally transferrable,” Dyck says, “but it’s definitely good information that farmers could access to support their fertilizer management decisions.”

Richard Gray

University of Saskatchewan

Optimizing crop research systems for long-term farm profitability

Marla Riekman

Manitoba Agriculture

Breaking ground: Strategies to reduce soil compaction

Mitchell Japp

Saskatchewan Barley

Development Commission

Rising to the Challenge: Innovations to manage lodging and sprouting in malt barley

Ken Wall

Federated Co-operatives LTD

Increasing productivity on fields affected by salinity

FEB 26, 2026

Saskatoon Inn & Conference Centre

Randy Kutcher

University of Saskatchewan

A gruesome twosome (stripe rust and bacterial leaf streak) of wheat

Dale Risula

Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture

Tackling root rot and other pathogens in pulses: Practical solutions for Prairie growers

Dr. Sean Prager

University of Saskatchewan

Dr. Shaun Sharpe

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Managing Herbicide Resistance: Kochia and emerging pigweed threats

The status of insect pests and insect transmitted pathogens in Saskatchewan crops with a focus on legumes

Dr. Jeff Schoenau

University of Saskatchewan

Enhancing the efficiency of nitrogen fertilizers

Dr. James Tansey

Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture

Cabbage seedpod weevil in Western Canada

THIS

Growing soybeans or lentils ahead of winter wheat could beat canola.

BY VANESSA FARNSWORTH

Western Canadian growers are often on the fence when it comes to adding winter wheat to their crop rotations, particularly if they don’t have canola stubble ready. A new study suggests that growing winter wheat immediately after soybeans or lentils has the potential to achieve superior grain yields and protein concentrations over canola.

“Canola is a priority crop for a lot of operations, given its historically higher cash value,” says Brian Beres, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge. “But the evolution of canola is such that a lot of the yield gains have been coming from adding growing degree day requirements, so you’re ending up with these later harvests that aren’t always an artifact of the environment.”

Beres led a series of field experiments conducted at Lethbridge, Alta., Saskatoon and Indian Head, Sask., and Brandon, Man. from 2018 to 2022 to better understand the impact seven different rotational crops (soybean, lentil, field peas, faba bean, canola, flax and oats) have on subsequent wheat crops grown in three, two-year rotational schemes: winter wheat-winter wheat, hard red spring wheat-winter wheat and winter wheat-hard red spring wheat.

“In this particular experiment, we thought, we know canola is the gold

standard, but a lot of things are happening on the Prairies when it comes to crop diversification or new crops. For example, there’s this westward march of soybean production,” Beres says. “So what’s the compatibility with something like that, and will those responses persist if we go back-to-back with wheat? Let’s test all these different crops that represent a range of species like cereals and lentils or pulses and canola, and let’s put up combinations of winter wheat and spring wheat to also see if there’s a differential response between growth habits.”

Researchers found that when soybeans and lentils were grown as preceding crops, they consistently outperformed canola when it came to winter wheat grain yield and protein concentration. In the second year following lentil and field peas rotations, winter wheat grain yields were similar to what was seen following canola, but with higher protein concentrations. These findings suggest that these alternate stubbles represent viable options for replacing canola. “That soybeans and lentils were the same or even superior to canola was a

TOP Oat plot at Lethbridge seeded on May 4, 2019. Left photo shows growth as of June 9, 2019 and right photo shows growth on July 26, 2019. Hard red spring wheat-winter wheat was a second factor.

bit of a surprise,” says Beres.

The study also found that soybean and faba bean stubbles in the hard red spring wheat–winter wheat system and field peas in the winter wheat–winter wheat system boosted wheat protein levels in the first wheat phase. Higher protein concentrations were also seen in the second year. In the final analysis, leguminous stubbles – especially lentils – resulted in superior in-season growth compared to canola, flax and oats. However, Beres notes that benefits from canola were more apparent in the second year of wheat, an indication that canola creates a break in the rotational scheme that translates into persistent benefits.

“We knew from our previous study that field peas, for example, could provide similar winter wheat yields as canola, which is counter-intuitive since an advantage of a crop like canola is it’s cut fairly high, and so you get this great snow trapping effect from the tall and sturdy stubble. Following that logic, if you don’t have much stubble residue, it’s a train wreck in the making,” says Beres. “But, if you think of field peas, the stubble residue isn’t great, but for some reason it’s providing benefits so that winter wheat survival isn’t affected, and it produces similar or even higher yields than canola. Lentils were not a whole lot different.”The study goes on to report that yields were higher in winter wheat than spring wheat in both years following rotational crops, suggesting that may be a sign that winter wheat responds better to preceding rotational crops than spring wheat and may also help improve the resiliency of cropping systems due to increased diversity.

Another notable finding was that winter wheat tended to perform better than hard red spring wheat in monoculture cereal systems, especially in the second year following rotational crops when both wheat types had reduced yields, something investigators say confirms winter wheat’s value in cereal phases in Western Canada.

“The upside of this study is that it reinforces that there are a lot of options in regard to where winter wheat can fit in your operation. It can jump in behind just about everything and do quite well,” Beres says, adding that proper sequencing of crops is still essential for success.

Beres also notes that growers who add winter wheat to their cropping systems can expect to see intangible benefits amplified by the synergies that

develop when multiple rotational crops are grown. Those benefits include greater, more stable yields, fewer diseases and weeds, less reliance on herbicides and better resilience to multiple environmental stresses than what’s typically seen in monocultures. Growing leguminous crops can also build healthier soils and improve fertility, both of which foster more sustainable, productive cropping systems and better wheat performance. The increase in biological nitrogen fixation also reduces the need for synthetic nitrogen fertilizers.

In part, because it’s competitive, winter wheat can be a lower input option. It tends to break with the life cycles of many insect, disease and weeds that have synchronized around a host with a spring growth habit. This can translate into reduced pesticide use and minimized risk from insects such as wheat stem sawfly.

“There are all these intangibles that we go on about such as improved water use in spring, earlier harvests, spreading out workloads, and people’s eyes begin to glaze over, but once they try winter wheat and see how it pencils out and how they harvested early and had cash flowing in much earlier - that’s when they really realize [what we mean]. And with experience, growers can consistently reap the benefits winter wheat can offer –particularly if the current spring wheat phase is lagging because of increased pest pressure.”

Does this mean more growers in Western Canada should consider adding winter wheat to their systems? While Beres says canola won’t be replaced anytime soon as the centre of many operations, every operation is unique; it really depends on where your farm is located.

“If you think of the Brown soil zone of the southern Prairies, there’s very little motivation to adopt canola these days,” says Beres. “And what we’ve shown is that if canola isn’t part of your operation because of environment or some other reason, some of these other crops can be your gold standard because they kept pace with canola and, in some cases, even beat it. So, the big takeaway here is that we no longer have to strictly anoint canola as the gold standard ahead of winter wheat.”

Case IH introduced the Steiger 785 Quadtrac in 2025. The new model brings increased horsepower (hp) – up 10 per cent over the Steiger 715 Quadtrac – with 853 peak hp and 40 per cent torque rise.

It maintains easy maneuverability and offers an optional heavy-duty suspended undercarriage for a smoother ride, better traction and reduced soil compaction.

“We understand the demands of farming are only increasing. The Steiger 785 Quadtrac is a workhorse designed to meet those demands with power and productivity,” says Ken Lehmann, customer segmentation lead at Case IH, in a media release. “With long days in the field, the boost in horsepower and torque allows farmers to do more in a day.”

With the new model, growers can access automation-driven features through subscription-free precision technology. It also works with Connectivity Included, a 3-year/2,000-hour warranty and a simplified SCR-only emission system.

Orders for the new 785 model began in September with deliveries scheduled for 2026.

John Deere’s new Operations Center PRO Service is a digital tool to help equipment owners improve the process of maintaining and repairing agricultural equipment. The tool can work with both connected and non-connected machines across John Deere’s agriculture portfolio and includes the ability to install software when

replacing electronic components or controllers.

The tool is based on foundational capabilities, including operator’s manuals, active and stored diagnostic trouble codes, secure software updates, JDLink information and warranty information. This comes with the purchase of John Deere equipment – at no additional cost.

However, the new service provides additional benefits, including machine health insights and diagnostic trouble codes, PIN-specific machine content, software reprogramming for John Deere controllers, diagnostic readings and recordings, interactive diagnostic tests and calibrations – available through an annual license starting at $195 USD per machine.

Denver Caldwell, vice president of aftermarket and customer support says the tool affirms John Deere’s support for customer self-repair. With a John Deere equipment owner’s permission, independent providers can also use Operations Center PRO service with the equipment owner’s permission.

“Our message to our customers is clear,” says Caldwell. “Whether you want the support of your professionally trained and trusted John Deere dealer to work with another local service provider, or to fix your machine yourself, we’ve created additional capabilities for you to choose the option that best fits your needs.”

AgWest Ltd., an agricultural equipment dealer with a network of locations serving Prairie farmers, broke ground on two new dealership buildings in Russell and Brandon, Man. The development is designed to provide farmers with expanded parts storage and increased service capacity.

“This is a big step forward for our team, our customers, and our community,” says Anthony Chwaluk, branch manager at AgWest Russell. “Having a full-service facility here means faster turnaround times, more support on the ground, and new opportunities for local employment. We’re excited to see these buildings taking shape.”

Originally construction was planned for completion in early 2025 but, with the delay, completion is now expected for 2026.

“Farmers in this area deserve a dealership that’s built to keep up with them,” adds Mark Neustaedter, account manager at AgWest Brandon. “This new building is going to give us the space, tools and team environment we need to serve them even better, and to grow alongside them.”

Lumiscend™ LUXE from Corteva Agriscience sets a new standard in cereal fungicide seed treatments, delivering powerful early-season protection with four active ingredients, including Inpyrfluxam for proven Fusarium and Rhizoctonia control.

Early seed- and soil-borne infections occur before crop emergence and can quietly limit yield long before symptoms appear. Seed treatment is a critical investment to protect cereals at the start of the season.

Know your seed, field, and conditions before you plant:

• Seed quality and vigour – Start with the highest quality cereal seed and protect your investment with seed applied technologies, like a seed treatment.

• Variety disease resistance ratings – Knowing the seed and seedling disease resistance levels of each cereal variety will inform the appropriate seed treatment.

• Field history – Understand the disease levels, pest pressures and prior crop rotations to determine the right seed treatment for each field.

• Weather, soil conditions and seeding practices –Seeding into cool and wet soil can increase the risk of infection by seed- and soil-borne diseases.

Seed treatment delivers protection exactly where it’s needed – at germination. Lumiscend™ LUXE targets key cereal pathogens, including Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, smuts, bunts, and Pythium, preventing infection before it compromises crop establishment.

Early disease pressure can result in damping-off, thin or uneven stands, reduced plant vigour, stunting, and uneven maturity. By protecting seedlings from the start, Lumiscend™ LUXE supports faster, more even emergence and stronger early-season growth.

The real cost of early-season disease often appears at harvest with reduced yield, compromised grain quality, and inefficient fertilizer use. By preserving plant health from day one, Lumiscend™ LUXE helps protect both yield and crop quality through the entire season.

Lumiscend™ LUXE provides broad-spectrum protection against both seed- and soil-borne diseases with four powerful actives:

• Inpyrfluxam (Group 7)

• Ipconazole (Group 3)

• Difenoconazole (Group 3)

• Mefenoxam (Group 4)

Easy to choose and easy to apply, Lumiscend™ LUXE combines four active ingredients in an all-in-one formulation optimized for smooth application and fast drying.

When paired with Lumivia™ CPL, it delivers a premium cereal seed treatment solution that combines outstanding disease protection with insect control to provide exceptional early-season performance.

Conserving beneficial insects while managing pests.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Friends and foes. Insects fall into these two categories on the Canadian Prairies. It is well known that beneficial insects can help to prevent outbreaks, but there is so much more to learn about them.

“As we’ve shifted from grasslands to crops on the prairies, we’ve changed the plant communities, and therefore the resources and interactions in insect communities, and have introduced new players, by accident or on purpose. We literally supply acres and acres of healthy, highly nutritious sources of their (pests’) favourite foods, which is the perfect recipe for them to thrive and multiply and be pests in the first place,” says Haley Catton, entomologist at Agriculture and AgriFood Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta. “An abundance of food (crops) boost the pests, which boost the next trophic level (beneficials) that eat the pests, whether the crops and pests and beneficials are native or not.”

From the perspective of insect pest control, Catton says there are two main beneficial insect categories: predators and parasitoids. These beneficial insects provide ecosystem services to agricultural production. “They kill pests. They scare pests, so they can change the feeding behavior of pests, for example, making pests fall off leaves, or interrupt their feeding patterns. And they also cycle nutrients, so they’re eating and pooping,” says Catton.

Predators are the meat eaters of the beneficial world. Lady beetles, ground beetles, rove beetles and spiders hunt down and eat insect pests. Adult parasitoids are generally vegetarians, but they lay eggs in pests, and the hatched larvae are the meat-eaters, eating the pest, usually from the inside out.

Parasitoids attack insect pests like aphids, cutworms, wheat midge, wheat stem sawfly, cereal leaf beetle, cabbage maggot, diamondback moth, lygus bug, alfalfa weevil and bertha armyworm. Parasitoids are often hard for the untrained eye to detect even when they’re making a big impact – their small size and internal

damage to pests mean their value can fly under the radar.

The diversity of beneficials on the Prairies is very high. There are over 200 species of ground beetles and over 300 species of spiders. Rove beetles (Staphylinids) are even more numerous, and parasitoid wasps have the most diversity, and many of them are undiscovered.

ABOVE Lady beetle larvae are an important predator of aphids.

“The really interesting thing about entomology is we’re constantly finding new species, because you don’t find them unless you look for them. Even when you find something, you may not know what it is, and maybe even the taxonomists don’t know what it is. So there’s a lot going on around us that we are not even aware of,” says Catton.

Catton cites a few studies that looked at biodiversity in southern Alberta. One study at Vauxhall, Alta. found 62 species of carabid beetles over four years in the mid-2000s. Another study found more than 37 carabid species in Lethbridge plots over two years in the late 2000s. Catton’s own study from 2017 to 2019 found 82 carabid species in southern Alberta wheat fields from 2017 to 2019. “That’s a lot of different species of predators running around along the ground that we don’t even notice, eating things like cutworms or grasshopper eggs,” says Catton.

The value of beneficials in controlling insect pests is difficult to estimate, although many research studies globally have tried, and efforts are continuing. There are many interacting variables that are hard to quantify, says Catton. Field studies are logistically difficult, and a prevented problem or a disappearing problem often goes unnoticed.

Catton gives a couple examples of the value of beneficial insects. The first is with the cereal leaf beetle and its parasitoid Tetrastichus julis. The parasitoid is an introduced specialist to the Prairies that only attacks

Each year, CABEF helps students to pursue rewarding agri-food careers through seven $2,500 scholarships. We’re looking for the future leaders who will help this industry meet tomorrow’s challenges.

Do you know someone who needs to fund their future in agri-food? Tell a student today.

Scholarship application deadline is April 30, 2026

Want to help support the next generation of agri-food leaders? Become a “Champion of CABEF.” This program allows your organization to directly sponsor a deserving student. Contact CABEF at info@cabef.org.

cereal leaf beetle. Follow-up monitoring was conducted by Catton and Hector Carcamo, another entomologist with AAFC Lethbridge, from 2009 to 2021. Cereal leaf beetle larvae were collected and dissected to see if the parasitoid was inside. Parasitism ranged from very low to as high as 92 per cent.

“These parasitoids are silently devastating these populations of cereal leaf beetles, and the follow-up monitoring was limited because cereal leaf beetle were hard to find,” says Catton. “That’s a biocontrol success, but it’s also hard to prove unless we had control sites where the parasitoids didn’t exist and then we could compare pest populations.”

The second example is the economic value of the parasitoid Macroglenes penetrans, which is a critical parasitoid of wheat midge. Studies in the 1990s found that the parasitoid kept wheat midge below economic threshold on 38.3 million acres (15.5 million hectares) in Saskatchewan. It was estimated to save $248 million in insecticides, not including time, fuel and other environmental benefits such as the preservation of other beneficial insects and pollinators.

PRESERVING BENEFICIAL INSECTS

The first step to helping maintain populations of beneficial insects is to avoid hurting them. Since insecticides kill beneficials and population recovery is unknown, Catton emphasizes that

Prepare for spring and a more productive growing season! Discover inspirational networking opportunities with industry leaders and access innovative ag products to improve the way you work now. Enjoy fun events and live entertainment.

Canada’s Farm Show, Regina, SK presented by Bunge brings global insights to local farming, delivering an unmissable experience.

scouting and economic thresholds should be used to guide insecticidal application.

In a 2021 Alberta survey of farmers and agronomists, 80 per cent scouted for insect pests and, of those, more than 80 per cent used economic thresholds to guide insecticide application. That’s good news for maintaining beneficial insects.

Economic thresholds for the Prairies can be found from many sources including AAFC’s Field Crop and Forage Pests and their Natural Enemies in Western Canada, provincial agricultural websites, the Western Committee on Crop Pests (WCCP) and provincial guides to crop protection.

Some insecticides are also “softer” on beneficial insects. Alberta’s Crop Protection Guide rates toxicity of insecticides to honeybees. Insecticides are rated as highly toxic, moderately toxic and relatively non-toxic.

Another toxicity resource comes from the partnership of Cesar Australia, the University of Melbourne, and the Grains Research & Development Corporate (GRDC) in Australia. They have developed a program called AgPest that provides information on pests and beneficial insects, as well as pesticide resistance.

The partnership looked at the effect of pesticides on beneficial organisms. It was a petri dish lab experiment that measured insecticidal effects on 15 beneficial species from 10 predatory and parasitic insect and arachnid groups 24 to 72 hours after exposure. The researchers found that the lethal effects got worse over time. Some insecticides were consistently broad-spectrum, such as chlorpyrifos, methomyl (Lannate) and dimethoate (Cygon/Lagon). Others like chlorantraniliprole (i.e. Coragen MaX) were consistently more selective and softer on the beneficial insects. They also found that toxicity varied with species within insect groups. Out of the research, a chemical toxicity table that rates insecticides for their level of toxicity on various beneficial insects was developed – and is available on the AgPest website. “The table is conceptually relevant to Canadian Prairies, but it’s not a direct overlap. We might need to develop our own,” says Catton.

According to Catton, researchers have developed the SNAP acronym as a way to help beneficials: shelter, nectar, alternative prey/hosts and pollen. By providing these resources, beneficials will be better able to maintain healthy populations in the field. Flowering plants and weeds, shelterbelts, crops with extra-floral nectaries (EFNs) such as sunflowers all help to nurture beneficial insects. Following economic thresholds to avoid unnecessary insecticide application leaves pest/prey remaining in a field for the beneficials to feed on. This food availability is important to ensure the beneficials hang around and are there to prevent the next pest outbreak.

A Prairie example of SNAP comes from American research on the parasitoid of wheat stem sawfly. Sugar from floral resources and aphid honeydew increased the longevity and egg load of Bracon cephi and B. lissogaster. A cross-border collaboration

RIGHT The Diolcogastergenus prey on diamondback moth larvae.

MIDDLE Cotesia vanessae erupting from cabbage looper.

FAR RIGHT Carabus nemoraliskilling bertha armyworm.

found that leaving tall wheat stubble over the winter increased over-winter survival of the parasitoids.

Catton says there is a real knowledge gap for Prairie-specific research related to beneficial insects. She says there are barriers to adopting beneficial management practices in general, such as lack of demonstrated costs and revenues, labour, time management and awareness.

farmers and agronomists could make truly informed decisions.”

“Ideally, we’d be able to tell

farmers what beneficial services they will lose with broad-spectrum insecticide application, and for how long. But we do not know how long beneficial populations take to recover after insecticide application. That would depend on immigration from non-sprayed habitat, reproduction rate, insecticide residues, pest/food availability, etcetera,” says Catton. “Losing the beneficials really is a hidden cost in terms of severity and length of time. If we had that information,

25_014908_Top_Crop_Western_Edition_FEB_CN Mod: December 9, 2025 8:39 AM Print: 01/05/26 page 1 v2.5

The two main Canadian information sources on beneficial insects are Field Heroes’ Pests and Predators Field Guide and AAFC’s Field Crop and Forage Pests and their Natural Enemies in Western Canada. “I think we could use our current tools better, and we can develop new tools that are more surgical like tweezers so that insecticidal sledgehammers aren’t even appealing anymore,” says Catton.

by Bruce Barker, P.Ag | CanadianAgronomist.ca

Every year, insect pests cause substantial economic losses on the Prairies, but there is no estimate of the total economic cost from insect damage. A review was conducted by Vivek Srivastava, Tyler Wist and Hector Carcamo with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) to develop a new way of estimating insect pest costs based on provincial pest reports, and to provide recommendations on how to standardize pest reports in order to help prioritize research funding.

The researchers explain that there are gaps in estimating the economic costs of insect pests, and in determining which insect pests are the most damaging - and there are several reasons.Thresholds and surveys are lacking for key pests and there is no repository of acreages impacted or record of the land area where a control action was taken along with costs. There is also no repository of estimated efficiency of control actions or records of resulting values of the grain and quality losses.

To develop an economic impact estimate of the main crop pests, the researchers summarized pest status reports from 2015 to 2024, that are presented annually to the Western Committee on Crop Pests (WCCP) and are filed at the Western Forum on Pest Management website.Over the 10 years, four insects were seen as the most damaging: flea beetle, grasshoppers, cutworms and lygus bugs. Other insect pests were wireworms, pea aphids, wheat midge and more.

From these reports, the researchers developed an estimated total economic impact. While not perfect, the researchers estimated the number of acres/ hectares treated with an insecticidal seed or foliar treatment, the cost of insecticide treatment, yield loss and value of crop loss. When combined, these provided an estimate of the total economic impact in an “average” year. The estimated number of acres affected and treated was based on general descriptions presented in the reports by provincial government entomologists.

In addition to these insect pests chewing through Prairie farmers’ pockets, other minor pests including cereal aphids, leafhoppers, root maggots, alfalfa weevil, cereal leaf beetle and diamondback moth also cause economic loss conservatively estimated at $1 million. Taking these additional pests into consideration, the annual economic impact is estimated to be over $204 million in an “average” year.

Cost estimate calculations for each insect pest, based on an “average” year Insect Pest

Lygus bug

Lygus bug

stem sawfly

Pea leaf weevil

Accurate estimates would require multiple data inputs, many of which are not available. Yield loss estimates are missing for some key insect pests. Accurate acreage affected by pests is not known. Other variables that require further refinement and verification include how much land was sprayed to control the insect pest, how effective the spray intervention was, the opportunity cost of controlling the pest, and yield losses from the insect pest. Development of resistance to insecticides further complicates these calculations.

Conversely, in some cases, pests at low population levels can actually stimulate yield such as canola that branches out in response to defoliation. This value would need to be incorporated into the estimates.

Another cost that is difficult to estimate is the environmental non-target impact of controlling the insect pest. This could include the impact on natural enemies, pollinators, soil engineers and detritivores.

A very large variable in estimating economic losses is the role that the environment plays in insect pest pressure and crop development. Climate projections suggest that some insect pest species may move further north. For example, a warming climate could increase conditions favourable for wheat midge infestations or grasshopper infestations could become more severe if hot, dry conditions develop more often. High-resolution weather and ecological data is required to capture these environmental influences on pest impacts.

The researchers recommend that a centralized, high-resolution pest data repository be developed. Economic thresholds need to be updated or developed so that farmers can make effective pest control decisions. Advanced technologies such as machine learning and predictive modelling could further enhance pest monitoring and risk forecasting.

Bruce Barker divides his time between CanadianAgronomist.ca and as Western Field Editor for Top CropManager. CanadianAgronomist.ca translates research into agronomic knowledge that agronomists and farmers can use to grow better crops. Read the full research insight at CanadianAgronomist.ca.

PrecisionPac® herbicides are made to order. Fast, convenient and field ready. No waste, no guesswork — just precision weed control made for your farm.

Ask your local retailer about customizable PrecisionPac® herbicides.

Early-season broadleaf weeds beware, Huskie PRE is here

Canada’s rst Group 27 cereal pre-burn herbicide o ers fast, reliable control of broadleaf weeds like lamb’s-quarters, cleavers, wild buckwheat and kochia, including those resistant to groups 2, 4, 5, 9 and 14. Enhancing permissible tank-mix partners like Roundup Transorb® HC herbicide, Huskie ® PRE is equipped to manage the toughest early-season weed challenges in cereal production.