TOP CROP MANAGER

INTERCROP MIX HELPS YIELDS

Growers see revenue boosts PG. 12

DEALING WITH ERODED KNOLLS

How to bring these areas back to health PG. 10

MINIMAL TILLAGE OK SOMETIMES

Soil quality and yields not affected PG. 18

Growers see revenue boosts PG. 12

How to bring these areas back to health PG. 10

Soil quality and yields not affected PG. 18

12 | Intercropping expands crop mix

The practice can provide higher yields and revenue than monocrops.

By Donna Fleury

20 | Switching it up

Consider canola seed size when calculating seeding rates. By

Bruce Barker

28 | Evaluating shelterbelts

Incentives and resources are needed to keep trees in the ground.

By Julienne Isaacs

Reclaiming and managing eroded knolls

Ross H. McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag

Understanding soil organic matter

Forages need fertilizer, too

Ross H. McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag

18 Getting out of a rut

SOYBEANS 26 Finding the sweet spot for seeding soybeans By Bruce Barker

SUCCESSION PLANNING: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

Whether you’re at the beginning of the succession planning process, in the midst of transitioning, or are about to complete the process, there are different elements to keep in mind. We caught up with Terry Betker, president and chief executive officer of the management consulting firm Backswath Management Inc., for advice at all stages of the process. familyfarmsuccession.ca

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and

the pages of

Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration

and consult with provincial recommendations and

labels for complete instructions.

BRANDI COWEN | EDITOR

This year’s “Canada 150” celebrations, marking 150 years since Confederation on July 1, 1867, have prompted reflection about the past, present and future of our country. Efforts to tell “the story of Canada” have led mainstream media to re-visit the feats of Canadians whose names usually appear in close proximity to the word “iconic,” including Bell (inventor of the telephone), Agnes Macphail (the first woman elected to the House of Com mons), Lester B. Pearson (the former prime minister who introduced universal health care and established the country’s reputation as a peace-keeping nation), Marc Garneau (the first Canadian in space) and Terry Fox (whose cross-country Marathon of Hope raised funds for cancer research), to name a few.

But then a funny thing happened and stories about lesser-known but no less influential Canadians started circulating – including a fair few from the agriculture sector.

Avid bakers learned they have David Fife to thank for establishing Red Fife wheat in Canada. Fife discovered the variety offered resistance to the rust that was costing many Ontario farmers their crops in the 1840s, plus excellent milling qualities that to this day make it a choice pick in specialty baking. It’s also a genetic relative to many earlier-maturing varieties of the wheat grown today.

Calgary Stampede fans discovered they owe a debt of gratitude to local ranchers Patrick Burns, Alfred E. Cross, George Lane and A.J. McLean for financing the inaugural Stampede in 1912. Today, visitors to the “Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth” spend an estimated $345 million at local hotels, restaurants and other businesses.

Oenophiles with a taste for home-grown vintages were reminded to thank Donald Ziraldo of Inniskillin Wines on Ontario’s Niagara Peninsula and Anthony von Mandl of Mission Hill Family Estate Winery in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley for pioneering the Canadian wine industry. According to the Canadian Vintner’s Association, wine tourism alone accounted for $1.5 billion in economic activity in 2015 (the last year for which this data is available).

The spotlight on Canadian achievements in agriculture may dim somewhat, now that the coun try’s milestone birthday bash is over. However, with exhibits like “Canola! Seeds of Innovation” now open at the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum in Ottawa and “Canola: A Story of Canadian Innovation,” travelling across the country to share the story of the “made in Canada” crop that now contributes more than $19 billion to the national economy each year, it seems the industry is far from finished celebrating our own iconic Canadians.

And with good reason: There are so many hard-working people in our sector, doing ground breaking, future-shaping work. Appreciating that work requires that we reflect on the past, present and future of our industry on an ongoing basis.

In that spirit, Top Crop Manager has partnered with our sister publications –Fruit & Vegetable, Manure Manager and Potatoes in Canada – to bring you Ag 150: The Past, Present and Future of Agriculture (ag150.ca). From Sept. 18 to 22, we’ll be delivering a daily e-newsletter straight to your inbox, looking back at some of the milestones that have shaped agriculture in Canada, and giving readers a glimpse of how new technology could shape the future. Sign up for Top Crop Manager’s e-newsletter at topcropmanager.com/subscribe to ensure you don’t miss out on this celebration of Canadian agriculture.

Here’s to the next 150 years of great Canadians and their great achievements.

Yield responses are common.

by Bruce Barker

Though often abused and neglected, mixed forage stands can respond to fertilization. Still, some growers are hesitant to apply fertilizer to meet fertility needs, perhaps because forage yields tend to decline over time or because lack of spring rainfall can limit yield responses.

“In my opinion, farmers and ranchers are often missing out on potential increases in forage yields and increased net returns by not optimally fertilizing their forage crops,” says Tom Jensen, a director in the International Plant Nutrition Institute’s North American program, who works out of Calgary.

Forage crops export far more nutrients off the field than grain crops because the majority of above ground growth is removed as hay. Annual grain crops typically recycle nutrients found in the straw and roots back onto the field, only exporting the nutrients found in the harvested grain.

Information compiled by Fertilizer Canada, for example, shows a three tonne per acre (6.7 tonne per hectare) grass hay crop removes around 100 pounds of nitrogen (N) per acre, 30 pounds of phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5), 130 pounds of potassium oxide (K2O) and 12 pounds of sulphur (S).

Saskatchewan Agriculture’s provincial forage crop specialist, Terry Kowalchuk, says farmers should soil test in the late fall or early spring to get an understanding of the levels of nutrients in the field. He says care should be taken to ensure the samples are representative of the majority of the field (i.e. mid slope positions) and if there are noticeable differences in soil texture or management from one part of the field to another, they should be

tested separately. Growers should sample at depths of zero to six and six to 24 inches. When soil testing, the percentage and species of legume in the stand should be indicated in order to obtain a more effective fertilizer recommendation.

“The shallower depth gives a good idea of nutrient levels (especially P and K) near the surface while the zero to six combined with the deeper depth increment will provide a sense of N and S levels at depth,” Kowalchuk says.

Jensen recently conducted a research trial on a ranch near Invermere, B.C., on a 50 per cent alfalfa and mixed grass stand where the ranch manager did not feel he was getting an economic return on applied fertilizer. The field was normally managed for a hay cut at the end of June, then allowed to regrow for grazing in the late summer and early fall. Applied fertilizer was 75 pounds per acre (lb/ac) of N, 60 lb/ac of P2O5, 100 lb/ac of K2O, 30 lb/ac of S, and one lb/ac of boron (B) for a total cost of $34.50 per acre.

Jensen reports the addition of fertilizer increased the yield to 4.5 tonnes per acre (t/ac) compared to 2.9 t/ac where no fertilizer was applied. Hay yield was increased by 1.6 t/ac and the local value of hay was $80 per tonne. The net return was $93.20 per acre, or $2.70 for every dollar invested in fertilizer – an excellent amount of realized profit, Jensen says.

Nitrogen fertilizer strategies depend on the proportion of legumes in the hay stand. Kowalchuk says N fertilizer will suppress N fixation since the plants and soil organisms will preferentially

ABOVE: Hay crops will respond to a fertilizer program, given the right environmental conditions.

Source: Fertilizer Canada.

*Legumes obtain most of the N from the air if root nodule bacteria are actively fixing N.

access the most readily available form of N. This typically means the rhizobium will reduce fixing nitrogen if fertilizer N is readily available.

“The age of the stand also makes a difference in how efficient alfalfa is at fixing nitrogen. Stands up to five years will fix about 70 to 80 per cent of their N requirements, but as the stand ages beyond five years, this can drop below 50 per cent,” Kowalchuk says. “So supplementation with N for older stands will provide a greater response and have less impact on N fixation than it will for younger stands.”

Generally, research has found that if a mixed stand contains more than 50 per cent legume in the stand, there will be little yield response to applied N fertilizer. Additionally, N fertilizer stimulates grass production, which can out-compete legumes in the stand and reduce the longevity of the alfalfa in the mixed forage stand.

Many years ago, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) researcher Lorraine Bailey in Brandon, Man., developed guidelines for fertilizing mixed stands. If the forage stand has 75 per cent or more grass, it would be managed as a pure grass stand and the emphasis would be on N fertility. At more than 75 per cent legumes, the forage would be managed as a pure legume stand with an emphasis on P, K and S.

Using Bailey’s approach for a mixed stand, the N fertilizer rate would be estimated at the N rate for a pure grass stand minus the per cent legume proportion multiplied by the N rate. For example, for a mixed stand with 60 per cent legume, if a soil test recommended 80 pounds per acre N for a pure grass stand, the formula would be: 80 pounds – (60 per cent legume x 80 pounds). So, 80 pounds – 48 pounds = 32 pounds N per acre recommended. This assumes the legumes in the forage stand are healthy and actively fixing nitrogen.

Kowalchuk adds that environmental conditions play a large role in how effective plants are at fixing their own N. Generally, if the soil test shows very low amounts of N, there is no harm in adding fertilizer to a stand with higher levels of legumes.

“The amount usually comes down to what a producer is willing to spend. In most cases P is more of a concern in mixed forage stands, and by adding monamonium phosphate fertilizer, you will also be adding some N into the system, although probably not enough to suppress fixation,” Kowalchuk says.

Guidelines for fertilizing mixed stands

Annual applications of N can be conducted with top-dressed urea (46-0-0) or dribble banding urea-ammonium-nitrate liquid N (UAN; 28-0-0). Both forms of N are subject to gaseous ammonia losses of N (volatilization) to the atmosphere if rain is not received within one or two days of application. UAN is less subject to volatilization since one-half of the N is in the ammonium nitrate form. However, UAN should only be applied as a dribble band because spray applications are much more vulnerable to loss due to increased contact with surface residues.

Urease inhibitors such as Agrotain can be used with urea and UAN; this can reduce volatile losses from the urea portion for up to 14 days or more. Research conducted in the early to mid-2000s by Rigas Karamanos, then with Western Co-op Fertilizers and now with Koch Agronomic Services, compared urea plus Agrotain versus ammonium nitrate fertilizer on a mixed bromegrass and alfalfa stand. Ammonium nitrate is not subject to volatilization losses, but is no longer available in Western Canada. The study across three nitrogen rates found there was no significant difference in yield between the two treatments, indicating that urea plus Agrotain is a suitable replacement for ammonia nitrate fertilizer.

ESN fertilizer from Agrium is another option that can be used to limit N losses. ESN is a controlled release fertilizer that releases over the growing season. Ray Dowbenko, an agronomist with

I will wake the rooster and be the one who decides when it’s time to quit. I will succeed by working with whatever Mother Nature provides, adapting and innovating to reach my maximum potential. I will actively pursue perfection.

With careful management – and time – farmers can return these areas to profitable crop production.

by Ross McKenzie, PhD, P.Ag.

Much of our Prairie landscape has gently rolling to hummocky topography. The parent geological material on which these soils formed is often glacial till that remained after the glaciers retreated 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. Thousands of years of soil formation and development on hill tops and upper slope areas resulted in thinner topsoil – primarily due to limited moisture for native vegetation growth. Thicker topsoil developed in mid-slope and lowerslope position areas and at the base of hill slopes.

The variation in topsoil thickness is greatest where slopes sharply diverged from knolls to depressions. Landscape topography influenced moisture penetration into soil, native vegetation growth, soil biological activity and various soil forming processes. Prior to cultivated agriculture, native vegetation cover usually prevented significant soil erosion from hilltops.

As the Prairie landscape was converted from native grassland to cultivation, topsoil on knolls was gradually lost. In the early years of cultivation across the Prairies, wheat-fallow was a common cropping system. Summerfallow, coupled with frequent cultivation

of unprotected soil, left topsoil vulnerable to erosion. Tillage and water erosion was a major factor in soil loss from knolls.

Tillage moved a tremendous amount of soil on cultivated landscapes and the effects were greatest in hilly landscapes, accentuating the erosion of knolls. The greatest amount of soil was usually moved when cultivating in the downslope direction versus in the upslope direction. The amount of soil moved by tillage is a function of slope gradient. Tillage erosion was often a major cause for severe soil loss on upper slope landscape positions and knolls. Many years of cultivation of knolls and leaving the soil bare has left them very susceptible to wind and water erosion.

Eroded soils lose clay- and silt-sized particles, as well as soil organic matter. The organic matter is mostly humus, made up of very stable

ABOVE: The variation in topsoil thickness is greatest where slopes sharply diverge from knolls to depressions.

carbon compounds. Organic matter takes hundreds to thousands of years to accumulate in the soil and is the glue that holds the soil mineral particles together to give surface soil a good granular or crumb-type structure. (See “Understanding soil organic matter” on page 22 for more information.)

Soil organic matter is the storehouse of organic nutrients; organic matter loss means significant loss of nutrients in organic form. For example, the loss of one inch of topsoil per acre is about 170 tons/acre. If the soil organic matter content is about four per cent, with about five per cent organic nitrogen (N) content, this would work out to about 640 pounds per acre (lb/ac) of actual N lost. Almost all N in soil is stored in organic matter. When erosion degrades the surface soil there are many physical, chemical and biological consequences.

Physical characteristics of eroded soil include:

• Degradation of the granular structure

• Reduced water-holding ability due to loss of organic matter and clays from surface soil

• Reduction of oil water infiltration rate, causing increased surface water runoff and increased water erosion

• Reduction of stored water due to increased water runoff

• Crusting of the surface soil

• Compaction of exposed subsoil

• Stony soil surface

Chemical and biological characteristics of eroded soil include:

• Reduction of active fraction of organic matter. (Active fraction includes living and decaying material, insects, worms and other soil micro-organisms.)

• Loss of biologically active portion needed for nutrient cycling

• Reduction of fertility levels

• Higher pH (about 8 or more) with free lime

• Higher N losses from urea or anhydrous ammonia due to alkaline pH

Yield reduction on eroded knolls is often in the range of 40 per cent to complete loss in dry years. The reduction in farm income can be quite significant depending on the percentage of land that is made up of eroded knolls.

The first thing to do is an assessment. Start by soil sampling and testing typical knolls

to determine the soil nutrient deficiencies and other concerns, such as low organic matter or high soil pH. When taking the soil samples, carefully check to determine if there is a hard pan from tillage or if the subsoil is compacted. The subsoil of knolls is sometimes naturally compacted due to glacial deposition.

If the surface of the knolls is stony, removal of stones is often necessary. If the soil is compacted, consider using some form of vertical tillage or subsoiling to reduce the density of the soil. If this is

necessary, it is best done in the fall when soils are dry to ensure good fracturing of the dense soil. Then, turn your attention to improving soil fertility. The best approach is to apply livestock manure or compost. For example, apply about 30 tonnes per acre of feedlot manure to improve soil fertility. This will also help to improve the organic matter and physical quality of the soil.

If manure or compost is not available, apply commercial fertilizer to aid in

The practice can provide higher yields and revenue than monocrops.

by Donna Fleury

Afew growers in Saskatchewan are adopting intercropping systems as a way to improve yields and revenue over monocropping. Researchers at the South East Research Farm (SERF) in Redvers, Sask., are helping growers address some of their intercropping questions through small plot research and replicated trials, including demonstrations and evaluations of the potential of various crop combinations. The results so far from research trials and commercial grower field efforts have been positive and interest continues to grow, with estimates of about 20,000 acres of intercrops in the province last year.

SERF research manager Lana Shaw initiated intercropping research projects with flax and chickpeas at Redvers in 2013. The results to date show good, reliable yields of both flax and chickpea have been achieved compared to monocrops, and often the combined yields of flax and chickpea are higher overall than when either crop is grown on its own. The intercrop provides structural support to the chickpea plants and improved harvestability.

Now new trials are underway to help determine the best flax seeding rates and compare mixed versus alternate seeded rows.

“We have expanded the mix of crops and are evaluating different pulses and oilseeds in combination and as monocrops for comparison,” Shaw explains. “In 2016, one trial compared a yellow mustard [Sinapis alba] monocrop with intercrops of yellow pea, maple pea and three types of lentil. A second trial compared a B. carinata monocrop with two types of dry bean, maple pea, fababean and large green lentil. Each crop was grown as a monocrop and then in the various combinations, with a total of 14 different treatments. No fungicide applications were included.”

Some of the plots were seeded with a SeedMaster in mixed rows in the same row, but an inch apart. For example, pulses were put down the fertilizer shank and seeded about 1.5 inches deep, while the oilseeds were put down the seed shank and seeded about threequarters of an inch deep. In 2016, the mustard trials were seeded with a smaller seeder that placed the seed in the same row and depth. This year, there is a mix of large SeedMaster intercrop trials and small cone seeder trials. Shaw is trying to scale up the trials now that they have shown some promise, since the SeedMaster plots are much larger. The new mustard-pulse intercrop trial seeded this year is a SeedMaster trial.

Monocrop mustard plots were seeded at six pounds per acre (lb/ ac) and intercrops were seeded at a half rate or three lb/ac, while pulses were seeded at a three-quarters seeding rate. Shaw explains, “We are trying to get a strong pulse crop and have the mustard in a supporting role. One of the strategies is to try and pick a winner in the intercrop and tailor the fertilizer and seeding rates to favour one crop, with the other crop in more of a supporting role. Sometimes the mix includes a higher value crop and a lower value crop together, so the goal is to end up with more of the higher value crop and targeting agronomics for that crop.”

Results from the 2016 growing season showed the most valuable and high-yielding intercrops were B. carinata with fababean

and maple pea, but all intercrops resulted in increased revenue compared to the monocrops. Although the lentil intercrops were less impressive in terms of yield, the total intercrop yield and value with lentil was higher than in the monocrops. The mustard yields were not very high in either the monocrop or the intercrop, however, there is a positive message: mustard is tolerating large amounts of peas or fababeans in the intercrop and performed as well or better than the monocrops. These results suggest there are a large number of potential intercrops that should be evaluated further for productivity and agronomic benefits. Intercrops may reduce risk from excess moisture, including high root and foliar disease pressure in lentil, which was a big problem in the southwest and west central areas of Saskatchewan in 2016. Lentils also have a developing problem with weed control; intercrops would likely lessen the impact of herbicide-resistant weeds and tough perennial weeds.

“These trials have shown positive results in terms of both increased yields and increased revenue and are helping us to prioritize the next research strategies,” Shaw says. “Producers are already trying mustard-pulse intercrops in their fields and they need research results to answer questions on things like seeding rates, variety selection, fertilizer rates, inoculants, disease pressure and weed competition. We are working to continue our research efforts to help growers answer these and other questions.”

This year, Shaw added new trials, including a few unfunded trials alongside other research work, in an effort to help growers find answers. “We seeded fababeans with canola using four different rates of canola and so far the plots are looking very good,” she says. “The seeding timing was a bit of an issue. We ended up seeding fababeancanola intercrop at the same time as the other fababean trials, which was quite early – on May 3 – into quite cold soils. Growers would likely plan to go a few days later than that. Although the timing was early for canola and emergence rates were fair, it was when we could fit the seeding in. Sometimes you have to make some compromises on agronomy to get everything done on time.”

Following up on another suggestion from spring commodity group meetings, Shaw is trialling an intercrop of conventional soybean with flax. Conventional soybean varieties are not often grown because of the lack of a weed control package, however, the markets for those types of soybeans are higher-value ones. The soybean and flax trials include a few different seeding rate combinations

and the yield results will be compared after harvest.

One of the challenges with intercropping and harvest planning is trying to match up varieties of the different crops in the mix with similar maturity timing. For example, with a mustard intercrop, it is better to select either a later maturing pea or a lentil variety that typically takes longer to mature. It can be a risk if one of the crops takes longer than expected and the other crop is ripe. Peas, for example, can sit for a while in the field or the crop can be swathed or desiccated at the timing for canola harvest. There is some risk of shattering with canola. Mustard also has some shattering risk, although yellow mustard is less prone. The key is to time the harvest to get as much crop in as possible at the quality targeted. Some crops may require drying if one intercrop has to be taken off a bit early to maximize the other ones.

“Although we are starting to have some reliable research results and there is lots of good advice out there, there is still a lot of trial and error left,” Shaw notes. “Growers still need to go ahead and pick an intercrop that seems reasonable and adjust from experience as they are going. Some growers like the challenge and are not afraid to try and keep working on their system. For others it can be an obstacle, as we don’t yet have specific crop mixes and agronomic practices for particular areas. For now, start small with a 40- or 80-acre field and select crops and varieties recommended for your area and build from there. We need to continue with larger research trials to help assess the opportunities for various intercrops and the best agronomic strategies.”

Shaw also welcomes growers to get together with a few others and contact her to set up a customized tour of the SERF trials.

For Derek Axten of Axten Farms in Minton, Sask., intercropping is now a priority across almost 6,000 acres of no-till land, mostly in the dry Brown soil zone. Axten and his wife, Tannis, were recently named the 2017 Outstanding Young Farmers (OYF) for the Saskatchewan region.

In 2009, Axten ended up with an intercrop by accident after seeding lentils into brown mustard stubble on 640 acres. This resulted in an unintended intercrop – and a good harvest with good yields from both crops. This success started Axten down the road of intercropping, which he has now implemented on most of his farm.

“Our farm is unique, with about two-thirds at our home near Minton in the dry Brown soil zone and the one-third near [the] Milestone/Lang area in the heavy clay Regina plains,” Axten explains. “In 2011, we seeded our first intercrop of peas and canola on a couple of quarters, which worked really well, and we have expanded from there. We have relied on growers like Colin Rosengren, a leader in intercropping since 2004, and researchers like Lana Shaw at SERF to help answer questions and discuss ideas. We have continued with brassica and pulses, and in 2014 added 1,400 acres of flax and chickpea intercrops as well. We have reduced our input use and have not used any fungicides, except for one late season pass last year in 2016 on the Kabuli chickpea fields (compared to three or four passes on neighbouring fields), after one of the wettest seasons on record with almost double the rainfall we usually get [totalling more than 16 inches at Minton]. The chickpeas yielded very well and achieved high seed quality.”

Axten is convinced intercropping works, and for the last two years, he has intercropped all of his broadleaf crops – he sees no

reason not to. Climate is a factor. In 2015 it was very dry, but intercrop yields were still 10 to 20 per cent higher than in monocrop fields kept for comparison. In 2016, the growing season was the wettest in recent memory and 2017 has so far been quite dry again, so building resiliency in their farming system is a priority.

“Overall, intercrop yields have never been lower than monocrops and, on average, yields and revenue are higher on the intercrops. Diversity is important and in 2017 [our] intercrops include lentils-flax, mustard-maple peas, sunflowers-hairy vetch, chickpeas-flax, canola-chickling vetch, and canola-winter peas. We will continue to implement intercrops for everything except the cereals, where we have seeded with clover as a companion crop to improve soil and keep cover growing on the land until winter for carbon capture and sunlight harvest.”

All of the crops in Axten’s fields are seeded as mixed rows except flax and chickpea, which are seeded in alternating rows in 20-inch spacing. This helps delay canopy closure and allows for more air movement later into the season. At Minton, the brassica intercrop is typically mustard-lentil because of the drier conditions and weed spectrum, while canola-specialty peas (maple, forage and other high-value pea varieties) are grown at Milestone. The intercrops help the pulses trellis and keep off the ground, improving harvest, yield and crop quality without fertilizer inputs. Seeding rates for brassicas are half the monocrop rates, with canola at 2.4 lb/ac and yellow mustard at five lb/ac, while pulses are seeded at two-thirds the recommended rates. Axten will sometimes seed a full rate of lentils in the mix as the high-value crop.

“I have tried a lot of different varieties and combinations in intercrops and never had a disaster because of maturity differences,” he says. “Although sometimes you may have to wait a bit longer, we’ve always been able to harvest using a combination of straight cutting, swathing and desiccation where required. Some growers are worried about harvest and combine settings, but we haven’t had any real challenges with machinery settings. Initially, separating the two intercrops can be a logistical challenge, but it is no longer a concern. We also found that if both crops are dry in their own right, they will store well together. Last year we stored flax and chickpea well into January until we had time to separate them.”

Intercrops will continue to be a main priority in Axten’s system, with flax and lentils likely taking over more of the brassica-pulse component. Axten is happy to talk to other growers who have questions and encourages those interested to also connect with SERF and tour the plots, or get in touch with other growers, such as Rosengren. The key to success is to do the research upfront. “You can save yourself a lot of pain by spending a half a day with Lana at the SERF plots, which often raises and answers questions you maybe hadn’t thought of ahead of time. There are about eight growers I know of implementing intercrops and we are encouraging more growers to consider intercrops. For our farm, no-till, intercrops, companion crops and cover crops, as well as controlled traffic farming and grazing, have reduced synthetic inputs, increased water retention and built up organic matter. We are seeing improved yields [and] soil improvements and building diversity and resiliency into our farm for the long term.”

“If

Mix what you want, seed what you want with the freedom of Aim.

Get a more complete burn down that lets you seed almost anything. Tank mix Aim with your choice of products, so you can use what you’re used to with superior results and no fear of cropping restrictions.

CANOLA | LENTILS | WHEAT BARLEY | & MORE FMCcrop.ca

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 7

Agrium in Calgary, says research has shown that spring broadcast application of only ESN is not recommended, as N-release is not fast enough for the forage crop’s immediate spring growth requirements. However, a spring application in a blend with urea or ammonium sulphate works well. The urea or ammonium sulphate supplies N to the first cut of hay and ESN supplies N for the second cut. An additional option is an early fall broadcast of ESN that will release soon enough to supply the spring N demand.

Ammonium sulphate is another N source in forage production, when economically available. Westco forage research in the foothills of Alberta found it to be equally effective as ammonium nitrate. Ammonium sulphate also has the additional benefit of supplying sulphur to the crop.

Recommendations for the addition of P, K and S should follow soil test guidelines. Information from Alberta Agriculture indicates annual applications of P2O5 fertilizer is reasonably effective, and if P is limiting production, annual maintenance rates of 20 to 40 pounds P2O5 per acre will help meet crop removal needs. Broadcast application of P is effective. At Swift Current, Bailey reported alfalfa could produce a dense mat of fine root hairs near the soil surface, capable of utilizing surface-applied P.

A four-year study by Westco with annual P fertilizer applications found that each successive P application produced higher yields – by year four, mixed forage yield was 50 per cent higher.

“I like early spring for P fertilizer application. There is usually good moisture available and if the soils are cold, the added P can help boost early shoot development,” Kowalchuk says.

On fields testing deficient in K – a phenomenon most likely to occur on sandy soils – an application of 50 pounds K2O per acre may produce a yield response. However, leave check strips to help determine if K fertilizer application is beneficial.

Sulphur is mobile in the soil and can be subject to leaching, especially on sandy soils. Alfalfa has high sulfur needs, so ensure good sulphur fertility in mixed stands. Follow soil test recommendations for sulphur application rates. In addition to S, ammonium sulphate 20-0-0-(24) has a stable form of N that can also supplement the crop when broadcasting to forage crops. The sulphate is readily available in the year of application.

Depending on the soil test recommendation, Kowalchuk says producers may need to consult with their supplier to get a blend that is suitable for their particular stand. The response to fertilizer will depend largely on moisture and growing conditions after application.

Kowalchuk adds that if producers are unsure whether they want to use fertilizer for rejuvenation, they can try it on test strips to get a sense of what sort of yield response they might get relative to the cost.

Alternatively, they can look at direct seeding more legumes into their existing stand to boost production.

“No matter what method is chosen, if you get a dry summer like we are experiencing in 2017, the chances of success are diminished,” Kowalchuk says.

GLOBAL EFFORTS TO PREVENT HERBICIDE RESISTANCE

Mark Peterson • Herbicide Resistance Action Committee

HERBICIDE USE IN CANADA: RESULTS FROM TOP CROP MANAGER’S INAUGURAL SURVEY

Gerald Bramm • Bramm Research

Sponsored by

MANAGING RESISTANCE WITH SPRAYER APPLICATION TECHNOLOGY

Tom Wolf • Agrimetrix Research & Training

HARVEST WEED SEED CONTROL IN THE CANADIAN CONTEXT

Breanne Tidemann • Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

NON-CHEMICAL WEED CONTROL METHODS

Steve Shirtliffe • University of Saskatchewan

CONTROLLING GLYPHOSATERESISTANT WEEDS: AN ONTARIO PERSPECTIVE

Peter Sikkema • University of GuelphRidgetown

The harvest of 2016 left many fields deeply rutted from combines and grain carts running over wet land. Many farmers had little choice but to till those direct-seeded fields in an attempt to fill in the ruts and smooth out the ground. But where it was once heresy to till a long-term no-till field, a few tillage passes won’t necessarily result in disastrous consequences.

by Bruce Barker

Farmers aren’t likely to undo what they have built up with no-till with a tillage pass or two if they have to cultivate to get rid of ruts,” says Jeff Schoenau, a soil scientist with the University of Saskatchewan. “The only caveat is that our research was conducted on small plots. If the tillage is conducted on the entire field and reduces soil aggregation and residue cover to the point that soil erosion could occur, then there could be some degradation of the soil.”

Schoenau was involved in a research study conducted in the mid-2000s that compared four tillage treatments that were imposed on no-till fields (longer than 10 years) at Rosthern (Black soil), Tisdale (Gray soil) and Central Butte (Brown soil), Sask. The minimum-till treatment was a single cultivation with a chisel plow, with sweeps in the spring prior to seeding. Conventional tillage was a fall and spring cultivation. A maximum tillage treatment included a fall and spring cultivation plus a spring tandem discing. These tillage treatments were compared to the standard no-till control treatment.

Total and particulate soil organic carbon, soil pH, and soil aggregation were not affected by the tillage operations. Tillage decreased the bulk density in the five- to 10-centimetre (cm) soil depth, but did not significantly affect soil water content (measured at zero to 10 cm) or spring soil temperature (measured at zero to five cm).

Schoenau says one concern when tillage is eliminated is that phosphorous (P) becomes stratified in the top layer of the soil and may be stranded in dry growing seasons. This research found tillage did reduce the stratification and redistribute P in the tillage zone, but there was no effect on P uptake by the plants.

Yield was not affected in the three years following tillage, except at Tisdale in the first year after tillage. Schoenau says at the time of tillage, the Tisdale plots had heavy straw that was incorporated into the soil. This resulted in immobilization of nitrogen (N) as soil microbes used soil N to help break down the high-carbon cereal straw. The effect did not last past the first year.

“When high carbon residue like wheat straw is incorporated into the soil, you will typically see [a] reduced supply of available nitrogen because of immobilization,” Schoenau says.

Other research at the University of Alberta also supports the notion that occasional tillage is not detrimental to crop yield, soil properties or organic carbon. Miles Dyck of the University of Alberta’s agriculture, life and environmental sciences department and chair of the Breton Plots Management Team, looked at imposing short-

term tillage on long-term no-till plots at the Breton and Ellerslie long-term cropping plots.

Plots were cultivated with various tillage treatments in the fall and spring for four years with straw management (straw removed and straw retained) and N fertilizer rates of zero, 50 and 100 kilograms of N per hectare (kg N/ha) in straw-retained plots and zero kg N/ha in straw-removed plots. Soil properties, N and P fertility, nutrient uptake and crop yield were measured.

“From what we observed, if you have been in no-till for 20 or 30 years and you go through a tillage cycle, the soil is resilient enough to be able to avoid degradation,” Dyck says.

In his studies, he found that two or three years of tillage had no effect on total organic carbon, total organic nitrogen and nitrogen mineralization in the soil. But at one site, light fraction organic carbon and light fraction N increased in the 7.5 to 15 cm soil depth, indicating the potential for carbon and N losses if tillage continued.

When looking at four years of tillage, plant yield, N uptake and P uptake tended to be greater with tillage compared to no-till but were only significant in a few cases at Ellerslie – results that could possibly be explained by greater N availability as organic matter was broken down. However, in the long term, if tillage continued and organic matter declined, N availability would eventually decline as well, resulting in lower yields.

“The benefits of the tillage to remove ruts and get the land back into production will likely offset any negative aspects of soil disturbance and mineralization of organic carbon,” Dyck says.

Schoenau notes more recent research he has been involved in supports the idea that tillage isn’t necessarily harmful in the short term. The first year of a vertical tillage trial in 2016 found no effect on yield under wet conditions, though the vertical tillage did tend to reduce the air permeability in the surface soil. The trial is continuing this year.

In a sub-soiling trial looking at alleviating wheel traffic induced compaction on Chernozemic and Solonetzic soils, Schoenau says there was no yield effect on the Chernozemic soils. However, there was a significant yield benefit on the Solonetzic soils that had also experienced wheel traffic.

These studies also align with a strategic tillage study conducted by Byron Irvine at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in 1999. He found soil aggregate size was reduced by tillage but there was little or no impact on soil carbon, nitrogen, bulk density, potentially mineralizable nitrogen or any other soil property measured. In the years after tillage, aggregate size began to return to the pre-tillage size.

Irvine reported strategic tillage did not have long-term negative impacts on yields or weed pressure, noting, “Tillage could be used in the sub-humid Black soil zone to control difficult weeds or level a rough field without long-term negative impacts on crop yields, disease or soil quality.”

For more on tillage, visit topcropmanager.com.

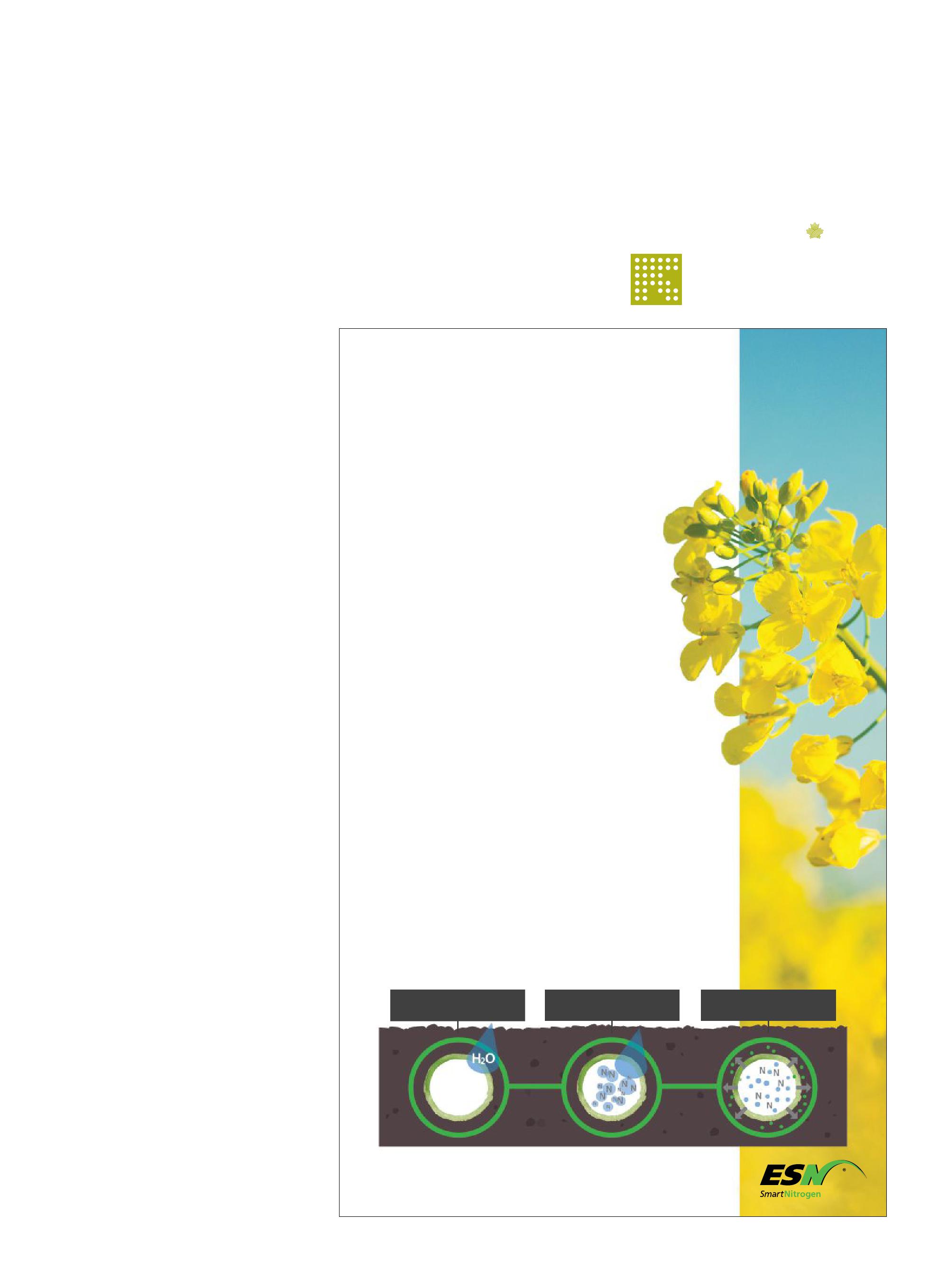

Too much early-season nitrogen (N) encourages lodging, depletes soil moisture and leaves less N for seed production. ESN technology controls N release, reducing N loss and increasing N efficiency. Additionally, it significantly reduces N loss to the environment.

ESN technology and increased yield

When compared with similar N treatments of urea or UAN, using 50-75% of N with ESN technology has shown an average of 8-10% increase in canola yield. This data is derived from a number of independent research studies conducted at various locations in Western Canada.

Unmatched seed safety

Applied at rates up to three times higher than conventional N fertilizers, ESN won’t harm growing seedlings (following safe rate guidelines and recommended percentages of ESN).

Wider application window

ESN provides a wider application window in both the spring and the fall, allowing you to apply fertilizer on your schedule.

Convenient to use and apply ESN is compatible with no-till operations and is easy to blend. It will not set-up in storage and therefore has a longer shelf life.

Environmentally responsible ESN significantly reduces N loss, providing substantial benefits to the environment.

Minimize N Loss. Maximize Yield. Learn more at SmartNitrogen.com

Gone are the days when canola growers dialled in a standard five pounds per acre seeding rate – or at least they should be. Today, with wide variations in seed size from three to six grams per 1,000 seeds or more, one size no longer fits all. Also, considering that many growers are cutting seeding rates to save on seed costs, hitting the Canola Council of Canada’s (CCC) recommended target plant stand may not be possible.

by Bruce Barker

Ian Epp, a CCC agronomist, says the long-term recommendation has been seven to 10 plants per square foot, but that recommendation is changing.

“In light of more recent research that looked specifically at current hybrids under modern planting conditions, we have somewhat reduced our plant stand recommendation, but more importantly, we have moved to a risk-based system, which helps farmers understand the risks and management challenges with various plant stands and the wide variety of planting conditions across Western Canada,” Epp says.

He explains that to help farmers better understand many of the important factors that influence plant stands, the CCC launched an online target plant density calculator (available at canolacalculator.ca) that goes through some of the major factors that need to be considered when deciding on a seeding rate. Those factors include early season frost risk, weed competition, in-season insect damage and growing season length.

Given the wide variation in seed size, the CCC also recommends farmers use its seeding rate calculator (found on the same website) to calculate seeding rate based on seed size. For example, if seed weighs six grams per 1,000 seeds and a grower targets five plants per square metre with a 60 per cent estimated seed survival rate, the seeding rate would be 4.8 pounds per acre. But, if the 1,000 seed weight is three grams, the seeding rate would drop to 2.4 pounds per acre to achieve the same target plant stand of five plants per square metre.

Recent surveys have shown that one-half of western Canadian canola growers have plant stands of less than 40 plants per square metre. This indicates that growers should put a renewed focus on choosing a seeding rate that focuses on target plant density.

Research by Neil Harker, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lacombe, Alta., highlights the importance of considering seed size when calculating seeding rates. Speaking at the ScienceO-Rama event hosted by the Alberta Canola Producers Commission earlier this year, Harker summarized two recently conducted research studies.

In 2013, direct-seeded experiments were conducted at nine locations in Western Canada. Four canola seed sizes (1,000-seed weights ranging from 3.96 to 5.7 grams) and one un-sized treatment (4.4 grams on average) were seeded at rates of 7.5 and 15 plants per square foot. Across all sites, seed size had no effect on emergence, yield or seed quality. Higher seeding rates resulted in higher canola emergence and increased early crop biomass, 1,000-seed weights and seed oil content. The higher rates also reduced days to the start of flowering and days to crop maturity.

“In this study, we didn’t find a compelling reason to go with a higher seeding rate,” Harker says.

The second study was conducted in 2014 and 2015 at 16 sites on the Prairies. “Small” canola seed (averaging 3.32 to 3.44 grams per 1,000) was compared to “large” canola seed (averaging 4.96 to 5.40 grams per 1,000) at five seeding rates: five, 7.5, 10, 12.5 or 15 seeds per square foot. This study found larger seed resulted in greater stand establishment than small seed. However, this did not translate into a yield benefit. Large seed tended to result in greater yield than smaller seed at all locations, but the differences were not significant. The results also showed the seeding rate and seed size interaction was significant. For large seed, yield did

not increase with an increase in seeding rate, but for small seed, yield increased with seeding rate. However, most of that significant yield increase occurred when moving from five to 7.5 seeds per square foot. Harker points out that at the lowest seeding rate of five seeds per square foot, the average yield of the larger seed was eight per cent (3.5 bushels per acre) higher than the small seed. Once the seeding rate was increased to 7.5 seeds or more, there was no difference in yield.

Large canola seeds increased crop density and crop biomass, but decreased plant mortality, days to start of flowering, days to end of flowering, days to maturity and per cent green seed. Seed size did not influence harvested seed weight, seed oil content or seed protein content.

Increasing seeding rates also increased crop density, plant mortality, crop biomass and seed oil content, but decreased days to start of flowering, days to end of flowering, days to maturity, per cent green seed and seed protein content.

Harker says the two studies point out the need to balance seed size and seeding rate when establishing canola. Larger seed and a higher seeding rate provide agronomic advantages such as better weed competition from a thicker plant stand. Additionally, earlier flowering and maturity can also provide other benefits, such as avoiding heat during seed set and missing fall frosts that can hurt seed quality.

“Getting a minimum plant stand of five plants per square foot

will help establish a crop with good yield potential. Our research data supports that. As you get close to that line, you may not lose yield but you can run into other risk factors such as green seed, frost or delayed maturity,” Harker says.

Steve Shirtliffe, a researcher at the University of Saskatchewan, conducted a meta-analysis of 35 previous canola seeding rate studies, which reinforces the need for a stand of at least five plants per square foot. He concluded that crops with fewer than five plants per square foot almost always experience a yield loss. His study emphasizes that farmers should manage their risk by considering all the factors in establishing a healthy, uniform plant stand.

“I would never recommend anything below five plants per square foot and, ideally, like to see six to seven plants per square foot,” Epp advises.

For more on seeding, visit topcropmanager.com.

Emergence, measured as plants per square foot or square metre, should be assessed at the two- to four-leaf stage in several different areas in a field.

The Canola Council of Canada (CCC) advises growers to choose one of the following approaches to count the number of canola plants in their fields:

• Count the number of plants in a one-metre length of row and calculate with row spacing to get the plant density. This approach is the most accurate, and tends to be used in research projects.

• Determine the number of plants in a 0.5-squaremetre hoop and multiply the total by two to determine the number of plants per square metre.

• Count the number of plants in a 0.25-squaremetre hoop and multiply the total by four to determine the number of plants per square metre.

The CCC recommends growers avoid using a onesquare-foot hoop or square to determine the number of plants per square foot, as that small an area will be less representative of the field, especially when canola is seeded on wider row spacings.

Soil organic matter is the cornerstone for good quality agricultural soils

by Ross McKenzie, PhD, P.Ag.

Organic matter (OM) in soil is the result of hundreds to several thousand years of microbial, plant and animal residue additions to the soil. Soil organic residues are constantly breaking down and are in various stages of decomposition. After years of soil formation and development, the OM level in soil reaches a steady state or equilibrium. The amounts and types of OM in a soil are strongly influenced by climatic factors, which, in turn, are dictated by the native vegetation growth that contributed to OM additions to soil. Landscape and geographic location also plays an important role in soil formation and OM additions to soil on upper, mid and lower slope positions.

Soils vary in organic matter content. Cultivated soils in the drier regions of the Prairies in the Brown soil zone typically have two to three per cent organic matter, while those in the Dark Brown soil zone have three to five per cent OM and those in the Black soil zone have six to 12 per cent OM. Cultivated soils in the Gray soil zone have one to three per cent organic matter.

Organic matter plays many important roles in soil and has many

positive effects on soil properties (both physical and chemical).

Much of the OM in soil exists as humus. This is the dark matter formed by soil microbes after the breakdown of plant residues and is chemically complex. Humus adheres to clay particles to bind soil minerals into a good granular structure. Humus is very stable and decays very slowly over hundreds of years. This is the material that gives soil its brown or black colour; the colour of the soil depends on the amount of humus in it. Soil OM is also made up of living biomass, which includes plant roots and soil microbes. This is the living part of soil. Soil microbes cycle and release carbon (C) and nutrients back to the soil for re-use by plants.

ABOVE: The column of water on the right has a suspended lump of soil from grassland and the column on the left has a lump of soil from the adjacent cultivated field. The soil from the cultivated field disintegrated rapidly while the lump from grassland soil remained intact three hours later. This simple demonstration shows the benefit of no tillage and increased soil organic matter to bind soil particles into good soil structure.

Soil OM is a major source of soil carbon. The terms soil organic matter and soil organic carbon are often used interchangeably. The C content of OM varies, but on the Prairies it is about 56 per cent. The following equation is used to estimate the total organic matter content of soil from soil organic C measurements:

Organic Matter =

% Organic Matter = % Organic Carbon x 1.78

Some soil testing labs determine soil organic C content to calculate an estimated percentage of soil organic matter. Soil OM plays a major role in the global carbon cycle and is a major sink and source of carbon.

and cropping system effects on soil organic matter

After Prairie soils were broken and developed for cultivated agriculture until the 1960s, the crop-fallow rotation system was widely used. Summerfallow was utilized to store valuable soil moisture and control weeds. But, over time, it was recognized that summerfallow in a crop rotation had very negative effects that caused soil quality and soil organic matter to slowly decline.

Summerfallow leaves the soil idle for a growing season. This results in increased soil moisture. Frequent tillage aerated the summerfallowed soil to stimulate microbial activity, resulting in accelerated soil organic matter breakdown and nutrient release. In the fallow year, there are no plants growing to contribute to the soil organic mater pool. Figure 1 shows the effect of the wheat-fallow rotation on four soil organic matter fractions over 100 years of cropping. The four organic matter fraction levels shown include: plant residue (one to five years to break down), active fraction (five to 20 years to break down), slow fraction (20 to 100 years to break down), and passive fraction (100 to more than 1,000 years to break down).

Using a crop-fallow rotation resulted in the decline of soil carbon by up to 50 per cent in Prairie soils over 50 to 100 years (Figure 1). The plant residue, active and slow carbon fractions were most affected, but the passive fraction (very stable organic matter) was relatively unaffected by cultivation. Soil organic nitrogen level declined by up to 60 per cent. This widely used cropping system relied on mineralization of nutrients stored in OM for crop nutrition. Summerfallow coupled with tillage also exposed soil to erosion by tillage, water and wind. Some of the worst wind erosion events on the Prairies occurred in

Figure 1. Effect of using a crop-fallow rotation on soil organic matter fractions over 100 years in a Prairie soil.

Source: Parton et al, 1983.

Figure 2. Impact of cropping system on soil organic C concentration in the top foot of soil (N fertilized treatments) (FW fallow-wheat; CW continuous wheat; GR grass; FCC fallow-wheat-wheat; FOW fallow-oilseed-wheat).

Source: Ross McKenzie.

the 1930s, when the crop-fallow system was commonly used. The crop-fallow system had very negative effects on soil quality after Prairie grasslands were broken and developed for annual crop production.

Fortunately, in the past 20 to 30 years, many Prairie farmers have shifted to continuous cropping, more diverse crop rotations, direct seeding of crops and have started using

adequate rates of fertilization. The interaction of these practices has been very positive, starting the process of increasing soil organic matter levels, which, in turn, is improving soil quality. This soil conservation system has had many benefits and the negative effects of summerfallow on OM levels are eliminated. Direct seeding ensures tillage is greatly reduced or eliminated to maintain a

protective cover of residues from previous crops on the soil surface. This greatly reduces water and wind erosion and conserves more soil moisture for future crops. Most important is the fact that plant residues are added to the soil every year and the rate of decay of organic materials is much slower with the elimination of summerfallow. By cropping the land every year, organic residues are produced every year to maintain and hopefully increase soil OM levels compared to the old wheatfallow system. Applying optimum rates of fertilizers ensures optimum crop yields and provides increased crop residue return to soil. Returning more residues to the soil can increase OM content. Eventually, wellmanaged soils will reach a new soil organic matter equilibrium or steady state level.

Figure 2 shows the change in soil organic carbon in a long-term crop rotation study in the Brown soil zone near Bow Island, Alta., after 24 years. I initiated the study in 1992 and ran the trials until 2013, when I retired. Plots seeded to permanent grass had the greatest increase in soil organic carbon, followed by continuous wheat treatments. The increases in organic carbon were modest but

significant. Much of the added OM in the soil is referred to as light fraction OM that mineralizes at moderate rates to release plant available nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), sulphur (S) and other nutrients for the growing crops.

There are many benefits to increasing soil OM. Organic matter improves soil’s physical structure by acting like a glue to bind soil mineral particles together into a good granular or crumb structure. This increases water infiltration rates, making it easier for water to penetrate into soil and, in turn, increase the amount of soil water stored for future crop growth. The improved granular structure makes soil more resistant to wind and water erosion (see photo on page 22). Soil organic matter acts a bit like a sponge to increase soil water holding capacity.

Organic matter is a very important storage reservoir for nutrients in organic form that are gradually released into inorganic form for plant uptake and micro-organism use. Organic matter is particularly important for storing N, as soil significant

amounts of N are normally only present in soil in OM. In healthy top soil, about half of all the P and most of the S is stored in organic form in soil OM.

Soil organic matter will increase the cation holding capacity (the ability to hold positively charged elements) of soil to bind and hold inorganic nutrients like potassium (K+), calcium (Ca++) and magnesium (Mg++) in the soil. Organic matter also helps to buffer soil against changes in soil pH.

Humus gives the soil a darker colour, which helps enhance absorption of the sun’s energy. Darker soils warm up a bit more quickly in spring, which in turn stimulates microbial activity. Warmer soils will stimulate more rapid crop germination and emergence.

In recent years, soil organic matter’s ability to absorb potential pollutants or toxins such as pesticides has been recognized. Soil organic matter provides a place where toxins are temporarily adsorbed and stored until micro-organisms can gradually degrade these materials over time.

Soil organic matter directly and indirectly influences many soil quality factors and agronomic factors to benefit crop production. Soil organic matter has tremendous positive benefits for soil physical qualities, such as structure and tilth for better root growth, water infiltration and water storage.

Get True Vertical Tillage With The Summers Supercoulter Coulter blades size residue, provide natural soil fracturing, and promote deep root growth.

Patented hydraulic hitch transfers weight between front and rear disk gangs. Super-Flex™ C-shank mounting minimizes rock damage.

Most important, soil organic matter serves as an excellent storehouse of slow-release nutrients to increase the fertility of the soil. Depending on the level of soil organic matter, and soil moisture and temperature during the growing season, soils can mineralize and release up to 80 pounds of N per acre during the growing season. Significant amounts of P and S can also be mineralized and contribute to crop nutrition.

In summary, organic matter contributes considerably to improved soil quality. To increase soil organic matter, farmers need to continuous crop, use diverse crop rotations, minimize or eliminate tillage, fertilize for optimum yield and return all crop residues. The interaction of these factors will help to maintain or even increase soil organic matter. Farmers should also consider using perennial forages in their crop rotations, as they are very effective for maintaining or building soil organic matter levels.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 11

improving soil fertility. For example, most eroded knolls are very deficient in phosphorus. Producers should consider banding about 100 to 150 pounds per acre of P2O5 into the knolls. If other non-mobile soil nutrients are deficient, such as potassium, consider supplemental addition of these nutrients as well. Once phosphorus and other nutrients are brought up to adequate levels, watch the knolls for nitrogen (N) deficiency. Soil tests will often indicate N levels are lower on knolls than the rest of the field, so be sure to fertilize adequately. When spring soil moisture conditions are very good on eroded knolls, consider applying 25 per cent or more N fertilizer on knolls versus the rest of the field to make up for the very low soil N and organic matter levels. Increased crop productivity from manure addition, or adequate rates of nitrogen, phosphorus and other fertilizers, if needed, will encourage increased plant growth, which in turn will add increased root biomass below ground and produce more above ground stubble, preventing future erosion.

To further prevent erosion, knolls should be seeded back to grass to add the most organic matter to the soil and build soil quality. However, most farmers find this is not practical with knolls scattered across the landscape, so continuous cropping and direct seeding to annual crops is extremely important. Keep protective residue on the soil surface at all times. Tillage should also be eliminated and knolls should not be summerfallowed. Straw and chaff should be chopped and returned to the soil, not baled.

Reclaiming eroded knolls involves extra work. But, with additional inputs, including manure and fertilizer, coupled with careful management, these investments will increase crop production on the knolls. Increased crop production will add additional organic matter to the soil to slowly build soil quality. Spending time and money wisely to improve eroded knolls will increase production and farm income and will build soil quality over time.

It’s time to lower the boom on your most serious weeds and combat resistance at the same time. As the only Group 10, Liberty® herbicide provides growers with a powerful tool to address the weed concerns of today and tomorrow.

Not too early, not too late.

by Bruce Barker

When is the “right” time to put soybeans into the ground? Research in Manitoba is moving beyond the recommendations borrowed from Ontario and south of the border to develop Prairie-specific guidelines.

“I would say that planting date is a case of balancing early versus late planting, and there are several factors to consider to determine when to plant,” says Cassandra Tkachuk, production specialist with Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers (MPSG).

Tkachuk says these factors include soil temperature, calendar date, the weather forecast following seeding, and personal risk – including frost risk for a specific area (number of frost-free days, calendar dates in which frost events are likely), the number of acres to be seeded to soybeans in relation to other crops (which may require earlier seeding than soybeans) and the timeline to complete seeding and harvest in general. “This allows the decision to become more personalized for the grower and for their specific location,” she says.

The original recommendation for soybean growers in Manitoba was to plant soybeans when the average soil temperature at seeding

depth was at least 10 C or higher. At this temperature, soybeans will emerge in about two weeks; if planted into cooler soils, they may take up to three weeks to emerge, putting them at risk for greater seedling mortality and insect and disease issues. If you wait until the soil temperature is 12 C to 15 C, soybeans may emerge within seven to 10 days.

In order to help refine recommendations, Tkachuk conducted two years of research at the University of Manitoba in 2014 and 2015 to look at how soil temperatures impact soybean yield, emergence and maturity at Carman (2014 to 2015), Melita (2014 to 2015) and Morden (2015). Planting was done at six different dates when soil temperatures of 6 C, 8 C, 10 C, 12 C, 14 C and 16 C at 10 a.m. were recorded for two consecutive days.

In analyzing soybean emergence, Tkachuk combined the soybean emergence data into cool (6 C to 12 C) and warm (14 C to 22 C) groups. Days to emergence from combined 2015 data, for example, found cool temperatures generally caused delayed soybean emergence

ABOVE: Once emerged, soybean plants are susceptible to frost damage at temperatures below -2 C.

Table 1. Relative yield (per cent average) and number of acres planted by seeding week in

Source: Manitoba Agricultural Services Corporation, 2008-2012.

and warm temperatures resulted in rapid emergence. She says the results show soil temperatures of at least 14 C at planting are ideal for soybean emergence.

However, when looking at yield, the two-year study found there was no soybean yield penalty from planting into low soil temperature plots. Tkachuk reports calendar date had a greater effect on soybean yield than soil temperature. In one case at Carman in 2015, seeding was delayed into June and resulted in a yield decline because of the late seeding date, not because of seeding into warm soils. Generally, yields at Carman were higher in 2014 and 2015 when planted into cooler soils, or on earlier calendar dates.

“My research, along with much of the literature, has indicated that planting in June can reduce yield. So, for the latter part of the planting period, I recommend that growers should aim to plant soybeans prior [to] the end of May, if possible. However, if there is a late spring, it is still acceptable to plant shorter season varieties in early June,” Tkachuk says.

Tkachuk also found late spring frosts had an impact on soybean stand establishment. A late spring frost at Morden in 2015 caused plant mortality to the first four temperature treatments (6 C, 8 C, 10 C and 12 C) because these plots had already emerged when the frost occurred. She says there should be a balance between soil temperature and planting date. Even if soil temperatures are warm early in May, the risk of late spring frosts should be balanced against getting the crop into the ground too early.

Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers is now recommending growers balance soil temperature, calendar date and the 24-hour weather forecast. It recommends that soil temperature should be at 10 C at 10 a.m. for at least two consecutive days before planting soybeans. But in addition to soil temperature, calendar date should also be considered.

Additionally, MPSG advises growers to look at the short-term forecast after planting. If the soil temperature drops below 8 C, or a cold rainfall occurs that drops the soil temperature, a chilling injury may occur to the seed or seedlings. Damage to cell membranes can occur if the seed takes up cold soil moisture.

“If there is a risk of cold/freezing air temperatures, it might be better to wait a day or two to seed soybeans. Rain should also be considered, where cold, wet conditions can increase the risk of chilling injury during imbibition,” Tkachuk says.

Information from Manitoba crop insurance data shows that in most areas of the province, the optimum planting date has been the second or third week of May, with yield potential remaining at 100 per cent up until third week of May.

The crop insurance data essentially indicates planting too early can increase the risk of damage from late spring frosts. Once emerged, soybean plants are susceptible to frost damage at temperatures below -2 C.

“And the personal risk factor is also important here. If a grower still has a lot of acres to put in the ground, it is likely best to start planting, even if conditions are not ‘ideal.’ Although my research did not compare which of these factors is the most important to consider for planting, it was likely that calendar date had a stronger influence on yield than soil temperature at planting,” Tkachuk says.

The bottom line is that growers need to balance soil temperature, calendar date and the weather forecast following seeding, along with their risk tolerance to spring or fall frosts, seedbed conditions and seeding and harvest windows.

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. These products have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from these products can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for these products. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready 2 Xtend® soybeans contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate and dicamba. Agricultural herbicides containing glyphosate will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate, and those containing dicamba will kill crops that are not tolerant to dicamba. Contact your Monsanto dealer or call the Monsanto technical support line at 1-800-667-4944 for recommended Roundup Ready® Xtend Crop System weed control programs. Roundup Ready® technology contains genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, an active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Agricultural herbicides containing glyphosate will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate.

Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individuallyregistered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole and fluoxystrobin. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole, fluoxystrobin, and clothianidin. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn plus Poncho®/VOTiVO™ (fungicides, insecticide and nematicide) is a combination of five separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole, fluoxystrobin, clothianidin and Bacillus firmus strain I-1582. Acceleron® Seed Applied Solutions for corn plus DuPont™ Lumivia® Seed Treatment (fungicides plus an insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole, fluoxastrobin and chlorantraniliprole. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for soybeans (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin, metalaxyl and imidacloprid. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for soybeans (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin and metalaxyl. Visivio™ contains the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil, thiamethoxam, sedaxane and sulfoxaflor. Acceleron®, CellTech®, DEKALB and Design®, DEKALB®, Genuity®, JumpStart®, Monsanto BioAg and Design®, Optimize®, QuickRoots® Real Farm Rewards™, RIB Complete®, Roundup Ready 2 Xtend®, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready®, Roundup Transorb®, Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup Xtend®, Roundup®, SmartStax®, TagTeam®, Transorb®, VaporGrip® VT Double PRO®, VT Triple PRO® and XtendiMax® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC. Used under license. BlackHawk®, Conquer® and GoldWing® are registered trademarks of Nufarm Agriculture Inc. Valtera™ is a trademark of Valent U.S.A. Corporation. Fortenza® and Visivio™ are trademarks of a Syngenta group company. DuPont™ and Lumivia® are trademarks of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. Used under license. LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. Herculex® is a registered trademark of Dow AgroSciences LLC. Used under license. Poncho® and VOTiVO™ are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license.

Incentives and resources are needed to keep trees in the ground.

by Julienne Isaacs

After the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Centre kicked off its shelterbelt program in 1903, the Indian Head Research Station sent out more than one billion free trees to western Canadian producers.

The stream of free trees slowed to a trickle, then dried up completely in 2012 and 2013 when the Harper Government dismantled the program.

But the trees could be coming back – if their carbon sequestration potential is recognized under a carbon tax credit scheme, says Colin Laroque, a professor in the University of Saskatchewan’s department of soil science. Saskatchewan has so far resisted signing on to the federal government’s carbon tax credit program, but Laroque believes it’s inevitable.

And the carbon storage potential of shelterbelt trees is very real. Laroque and his team have just wrapped up a multi-year Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Program-funded project looking at the above and below-ground carbon storage potential of shelterbelts, broken down by tree species in Saskatchewan. The project has been renewed for a second phase that began this spring.

The first part of the project involved determining how many shelterbelt trees still exist in Saskatchewan, and getting a sense of producer perceptions of their value.

Using satellite imagery, the team discovered 51,000 kilometres of shelterbelts still stood in the province as of 2015.

“We started asking people how much they value shelterbelts,” Laroque says. “We had databases saying that in 1942, 100 spruce were sent to a specific location, and we’d use Google Earth and find the line of trees still there. We would then drive to the location to see how the trees were doing. For 65 or 70 years they’d been growing, and we could measure their carbon storage potential.”

Laroque says the first part of the project established the

carbon sequestration value of six different species of trees commonly used in Saskatchewan shelterbelts: hybrid poplar, Manitoba maple, Scots pine, white spruce, green ash and caragana).

“Now we want to know how often and how many people are pulling out trees. Every year a tree grows you sequester carbon. But every year people also pull them out,” he says.

In 2013, then-masters student Janell Rempel conducted a producer perceptions survey, the results of which were published earlier this year in the Canadian Journal of Soil Science.

The survey found most producers did not recognize the economic or environmental benefits of shelterbelts, as they are not compensated for the work involved in planting and maintaining them. Perceptions differed, however, based on the type and location of the trees. Shelterbelts in open fields were viewed more negatively than shelterbelts around farmyards and farm buildings.

One key finding was that large-scale producers believed shelterbelts are outmoded. “Many of the producers in Saskatchewan are also shifting from shelterbelt agroforestry systems to the use of other technologies for large-scale agriculture operations, such as zero-till and chemical fallow, indicating that field shelterbelts were no longer the preferred best management practice for some producers,” Rempel concluded in the article.

“Quite a few people aren’t aware of the broader landscape benefits, but even if they are aware, it’s hard to expect someone to bear that cost on their own without an incentive,” says Rempel, who now works as an area marketing representative for Richardson Pioneer.

ABOVE: A multi-row shelterbelt on an operation west of Saskatoon, with species including Siberian elm, green ash, Manitoba maple and caragana, in 1950, 1972 and 2011.

DO YOU RECYCLE YOUR PESTICIDE CONTAINERS? DO YOU RECYCLE YOUR PESTICIDE CONTAINERS?

There’s too much plastic waste making its way into our landfills, and the only way to address the problem is to go back to the basics: reduce, reuse, and recycle

Plastic is a key material in the world economy that can be found in virtually everything these days. Worldwide, 322 million metric tons of plastic were produced in 2015, and by 2050, that number could be four times higher.

Canada’s agricultural community uses a great deal of plastic. It can be found in bale wrap, greenhouse film, tubing and pipes, pesticide containers, grain bags, silage bags, twine, nursery containers and more. While plastic has become an essential part of modern agriculture, what to do with the material when it’s no longer useful is an ongoing challenge.

Historically, discarded agricultural waste has ended up in landfills or been burned or buried, sometimes on farm property. Landfills are difficult to site and expensive to manage and plastic buried in a landfill does not decompose, thus filling up valuable space. Burn barrels and other backyard incineration methods are also problematic because they can release harmful emissions in addition to wasting valuable resources.

Alternatively, recycled plastic can be reused to produce new products using fewer natural resources in the manufacturing process, eliminating emissions and saving landfills.

To help growers better manage their farm waste, CleanFARMS has partnered with agri-retailers and municipalities across the country. We work with more than 1,000 collection sites to make our programs accessible to growers in every region. The strong demand for CleanFARMS programs demonstrates the commitment of the entire agricultural industry to protecting our environment and preserving our resources for future generations.