TOP CROP MANAGER

POST HARVEST

WEED CONTROL

Reduce spring workload PG. 6

SALINITY SOLUTIONS

Providing practical tools

PG. 14

APPLYING NITROGEN IN FALL

Know the pros and cons

PG. 26

Reduce spring workload PG. 6

SALINITY SOLUTIONS

Providing practical tools

PG. 14

APPLYING NITROGEN IN FALL

Know the pros and cons

PG. 26

8 | Improving winter wheat production Enhancing stand establishment can improve overwinter survival. By Bruce Barker

MANAGEMENT

Reduce your spring workload

AND DISEASES

Improving sclerotinia forecasting

Donna Fleury

Field management to reduce blackleg risk

Donna Fleury

32 | Crop nutrition problems can become pest problems

Deficiency of a single nutrient can impair healthy plant growth. By Dr. Rob Mikkelsen

Fall application of nitrogen fertilizer

zinc nutrition needs under irrigation

Reducing establishment costs of AC Saltlander

Bruce Barker

38 | In-crop corn fungicide – does it pay? Producers should weigh all their options. By John

Dietz

Short rotation legume forages can provide an N benefit

Donna Fleury

The rise of the drone

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check

and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

JANET KANTERS | EDITOR

It was a busy summer of field tours and crops walks, and at almost every one I attended this year, there was a presentation about UAVs, or unmanned aerial vehicles.

Also known as drones, UAVs are coming within the range of affordability for many farmers and other agriculture industry folks, and so it’s not uncommon to see them flying above a crop at any given time.

The use of drones is certainly not a new concept – various militaries worldwide have been using them since the early 1900s. Today, drones/UAVs are used in various other capacities, including monitoring and inspecting pipelines, acrobatic footage in filmmaking, search and rescue operations, and counting wildlife, to name only a few.

The value of aerial imagery in agriculture is the focus of several research projects in Canada. One example: Dr. Chris Neeser, weed scientist with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development, conducted experiments this summer to determine whether UAVs can help identify weed problems in crops. Working with Jan Zalud of Calgary-based JZAerial, Neeser hopes to develop a formula on how to acquire and process field imagery captured by UAVs and then determine how accurate, useful and economical it is in identifying weed issues.

But spotting weeds is not the only use of UAVs –according to Zalud, other uses include collecting data on things such as hail or drought damage, field traffic patterns, moisture levels and possible crop damage from herbicide spray drift. Indeed, it appears UAVs fit quite nicely into the overall precision agriculture area of farming.

But will UAVs replace boots in the field? Personal field scouting is one of the most important tools farmers use throughout spring, summer and fall, and to think that UAVs can better the personal touch is reaching. But there’s no doubt that UAVs are increasing in popularity – and affordability – and are here to stay. Let’s hope the cost of using UAVs is offset by the savings realized from the data collected.

Last December, the U.S.-based Agri Media Council – a committee of ABM (association of business information and media companies), conducted a media channel study, polling farm and ranch owners, operators and managers, on their use and engagement with traditional and digital media in the agriculture industry.

The findings, at least to me, aren’t that surprising – the study found that 97 per cent of the respondents continue to use agriculture magazines and newspapers, making print media the number one resource for information.

The study stated: “While we can see clear changes in the usage of some digital channels, the use of traditional channels has not been sacrificed. Even when results are analyzed based on age, the use of traditional channels such as print, television and radio are as important as ever.”

So gush all you want over the latest tablet or smartphone app – for in-depth, technical stories on crop production, it’s hard to beat the solid and technical information you can glean from print media, especially in Top Crop Manager

And speaking of solid information, this issue of Top Crop Manager is chock-full of stories on pests and diseases, fertility and nutrients and crop management issues. Let us know what you think of this issue – email or call me directly (contact information to the right), and follow us on Twitter @TopCropMag.

CIRCULATION email: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Crop Manager West - 9 issuesFebruary, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, September, October, November and December1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada 4 issues Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter 1 Year $16.00 Cdn plus tax

All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of

Your crops will eat this stuff up.

ESN® SMART NITROGEN® has a unique controlled-release technology that provides season long nourishment to your crops, typically with a single application. The polymer coating reduces the risk of nitrogen loss to the environment, and allows you to apply ESN at up to three times the seed-safe rate of urea. Best of all, it improves crop quality and yield. Get the facts from your retailer, or visit SmartNitrogen.com

Post-harvest weed control makes sense.

by Bruce Barker

While harvest always takes priority in the fall, in some years the combine is put away early, and an open fall provides the opportunity to control weeds before spring. And post-harvest weed control can be even better than a spring, pre-seed burndown.

“We went through a cycle when glyphosate came down in price and many farmers just used a spring glyphosate burn-off because it was so cheap. But we’ve found that narrow-leaved hawk’s beard and dandelion control in the spring isn’t very good. With some of the residual herbicides now on the market, post-harvest winter annual and dandelion control is a very good option,” says Ken Sapsford, research assistant at the University of Saskatchewan.

Sapsford did dandelion weed control research in the mid-2000s and compared spring applications of glyphosate alone or PrePass to fall applications of glyphosate, PrePass, or 2,4-D. He says there are two optimum times to hit dandelion: pre-seed and post-harvest. He found that fall applications were the best for dandelion control, and that fall applications of PrePass or 2,4-D also provided residual control of dandelion seedlings in the spring.

“In-crop control isn’t very good because the crop closes canopy and

the dandelion goes dormant until the fall until the canopy opens up after harvest,” he explains.

Post-harvest weed control benefits well proven

Clark Brenzil, provincial weed control specialist with Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, says that research on fall weed control goes back in time. A research study conducted by C.H. Anderson at the Swift Current Canada Department of Agriculture research station in 1967 showed the benefits of controlling winter annual stinkweed and flixweed. Anderson’s report stated: “This study has demonstrated that a late autumn application of 2,4-D ester is effective in controlling stinkweed and flixweed. Late fall tillage is also effective… The proven effectiveness of late autumn sprays has provided prairie farm operators with another technique to control winter annual weeds without exposing the soil to possible wind erosion.”

CONTINUED ON PAGE 13

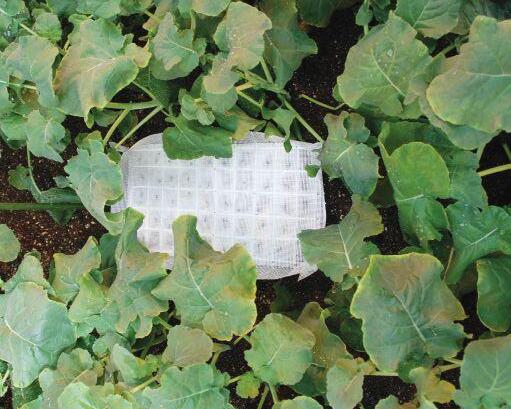

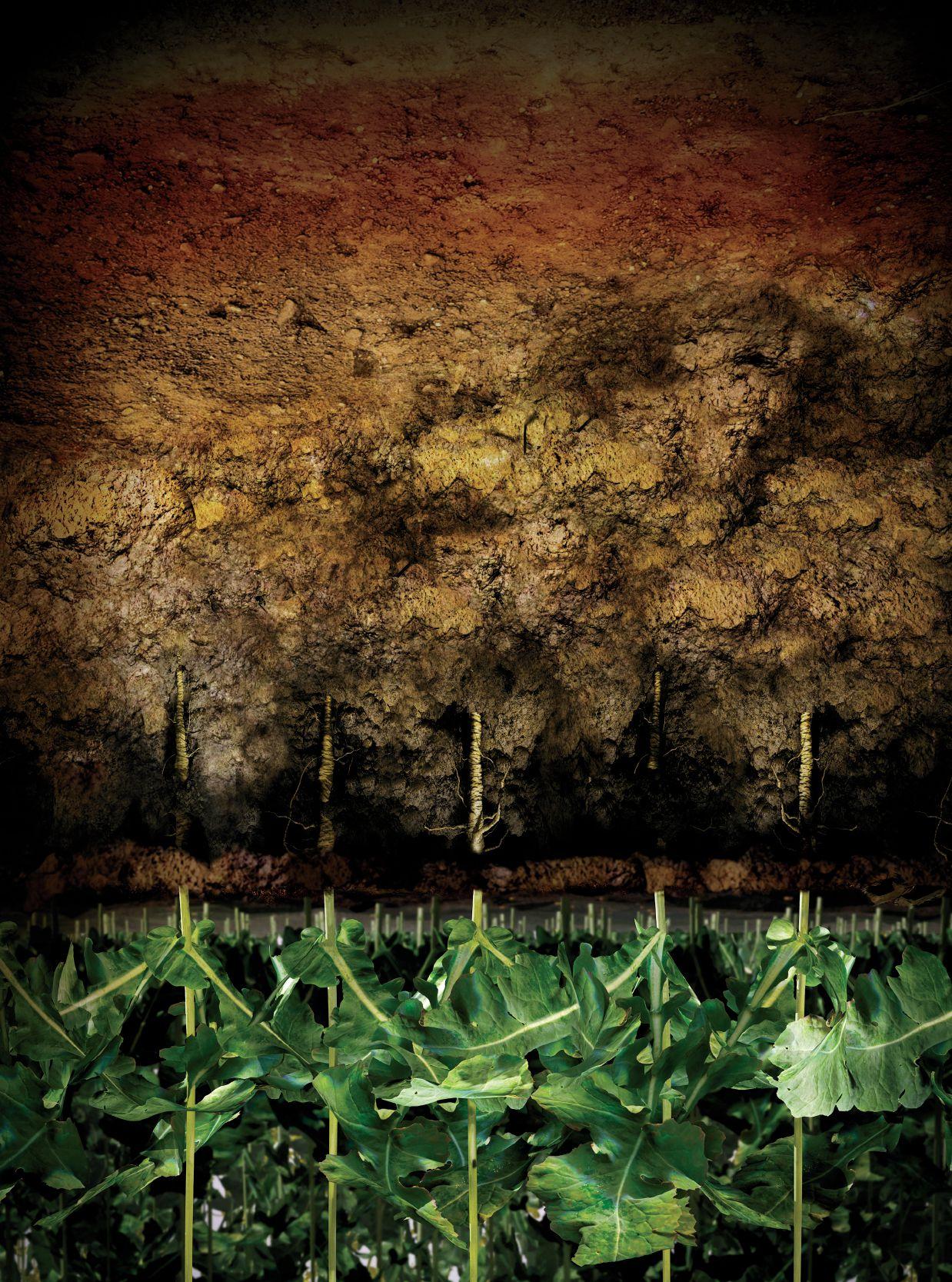

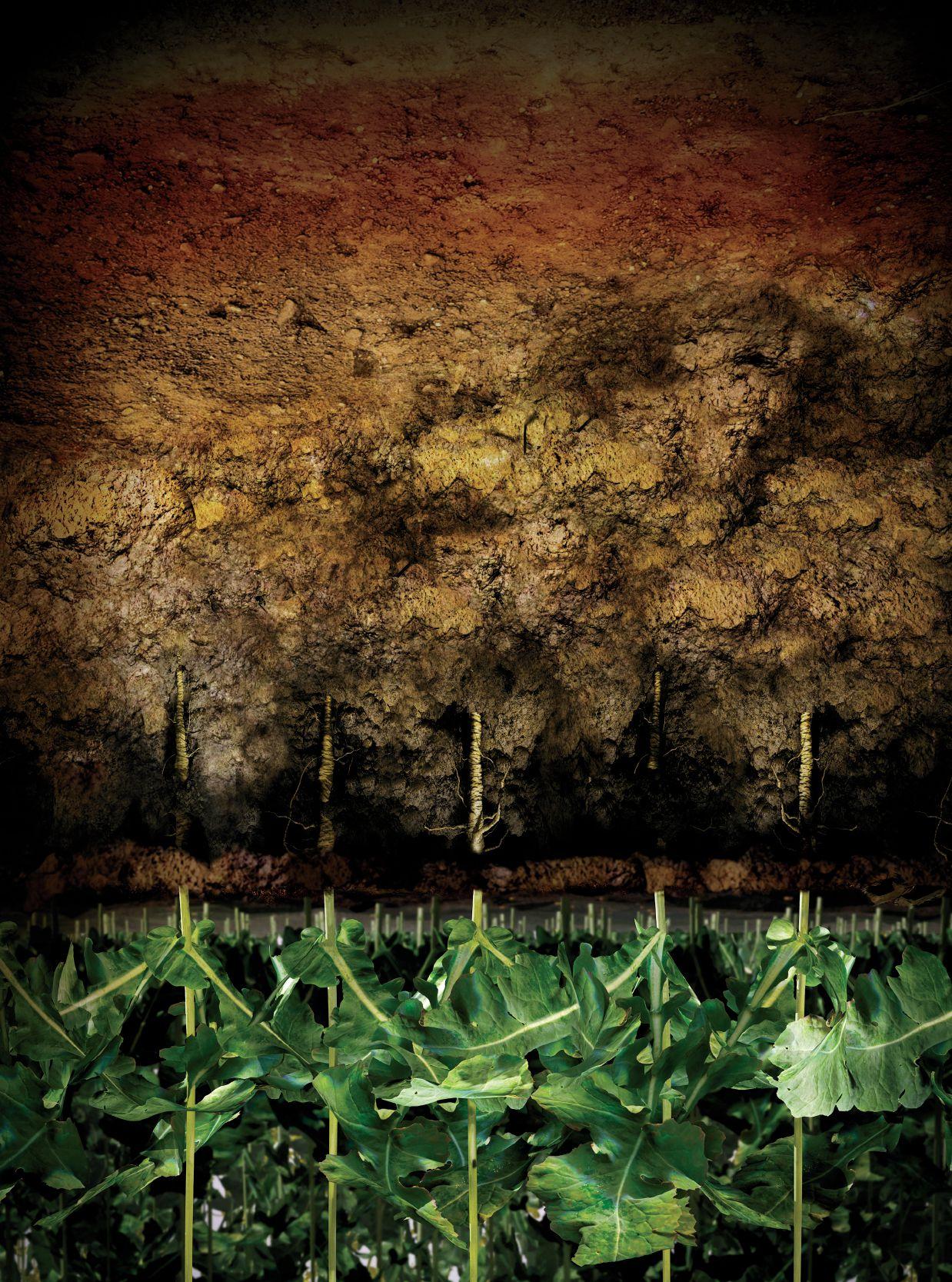

TOP: Post-harvest weed control can benefit later seeded crops. INSET: A post-harvest weed control application makes the most sense on fields where later seeded cereal crops will be planted.

Overlap happens on every farm, every year – wasting valuable inputs. SeedMaster’s Auto Zone Command™ overlap control technology helps eliminate overlap – saving SeedMaster customers millions of dollars since it was introduced in 2011.

Auto Zone Command is smart, proven technology – included at no additional cost on all SeedMaster metering systems. Contact your closest dealer and find out how Auto Zone Command can save you THOUSANDS every year on your farm!

Enhancing stand establishment can improve overwinter survival.

by Bruce Barker

If you didn’t like the winter of 2013-14, just imagine what a winter wheat plant felt like. For winter wheat, having a strong, healthy, disease-free plant established in the fall is critical to over-winter survival, which directly translates into higher yields. To help assess the affect of crop inputs on stand establishment, over-winter survival and yield, research scientist Brian Beres at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Lethbridge, Alta., led a multi-site-year research trial to see if stand establishment and overwinter survival could be improved.

“We were hearing conflicting reports about the effects of seed treatments on crop health and over-winter survival and wanted to find out if there were any impacts,” says Beres. “Growers will continue to grow spring wheat if they have a ‘train wreck’ but when that happens to a new winter wheat grower, he may never try it again. So in order to expand the acreage of winter wheat, we need to develop best practices for stand establishment.”

With funding from AAFC’s Developing Innovative Agri-Products Program, Duck’s Unlimited Canada, Alberta Wheat Commission, Saskatchewan Winter Cereals Development Commission, Winter Cereals Manitoba, and in-kind support from Bayer CropScience, Beres initiated two studies looking at seed and foliar fungicide treatments’ impact on stand establishment.

The first study included 20 sites established over the course of two growing seasons (2010-2011 and 2011-2012) at Lethbridge (irrigated; rainfed clay loam and silty clay sites), Medicine Hat, Beaverlodge and Lacombe, Alta.; Scott, Melfort, Canora, and Indian Head, Sask.; and Brandon, Man. Four seed treatments and a fall foliar application (see Table 1) were compared to untreated checks. The foliar fungicide was applied at the three- to four-leaf stage in mid-October.

Beres says that spring plant stand was not affected by the treatments, even though the stand with seed and/or fall foliar applications looked visibly thicker and greener. He says the fall foliar application produced a spring plant stand that was clean of powdery mildew on the lower

leaves, and was more vigorous in colour and appeared to have a better plant stand. Grain yield was improved with Raxil 250 and Raxil WW seed treatments. Foliar application increased yield slightly. Where stripe rust was present in three of the 17 site-years, yield was improved significantly with the fall foliar application.

“But even in those sites without rust, the foliar application seemed to elicit a physiological response that improved the look of the crop and over-winter survival,” says Beres. “While there isn’t a specific pathological explanation for the foliar fungicide response, there is likely a buffer against a stress response in the plant.”

When Beres plotted the results looking at the variability of the treatment against the grain yield, the highest yields with the lowest variability all included a seed treatment plus the fall foliar application. Whether using a foliar application makes sense from an economic perspective was another matter. The highest return was with a Raxil WW seed treatment. Including a fall foliar application along with the Raxil WW reduced the economic return due to the additional fungicide and sprayer application costs.

“For some reason, using a foliar fungicide provided a more stable yield. It didn’t necessarily provide a higher economic yield, but there is something there. When we flesh out the data in more detail for manuscript preparation perhaps we’ll have a better idea,” says Beres. (See Table 2.)

Beres acknowledges that with varieties resistant to stripe rust, stripe rust shouldn’t be an issue since the adult gene resistance means the maturing plant can overcome the stripe rust as the crop grows into maturity. Based on this limited data, growers might want to consider a fall foliar application if stripe rust is present in the fall, or at the very least, consider some test strips.

ABOVE: Fig. 1. Weak agronomic system of low sowing density and light seed with no seed treatment (left photo) or with dual fungicide/insecticide (Raxil WW) (right photo).

Product Active ingredients

Seed Treatments

Loose smut, common bunt or stinking smut; seed rot and pre-emergent damping-off caused by seed- and soil-borne Fusarium spp.

Allegience Metalxyl Seed rots and seedling blights caused by Pythium spp.

Stress Shield Imidicloprid Wireworm

Raxil WW Tebuconazole, metalxyl and imidicloprid

Source:

Loose smut, common bunt or stinking smut; seed rot and pre-emergent damping-off caused by seed- and soil-borne Fusarium spp.; seedling blight caused by seed-borne Fusarium spp.; damping-off caused by Pythium spp.; seed-borne Septoria nodorum, and wireworms.

Foliar fungicide

Root and crown rot caused by seed- and soil-borne Fusarium spp.; common root rot caused by seed and soilborne Cochliobolus sativus

Root and crown rot caused by seed- and soil-borne Fusarium spp.; common root rot caused by seed and soilborne Cochliobolus sativus; seed rot and pre-emergent damping-off caused by seed- and soil-borne C. sativus; seedling blight caused by seed-borne C. sativus

*Prices based on final Farmer Payments reported by the Canadian Wheat Board http://cwb.ca/_uploads/ documents/1112payments/2011-12_tonnes.pdf

**Addition of fall-applied foliar prothioconazole (Proline) at sites with stripe rust further improved net returns to those reported above Source: Beres, AAFC.

In a second trial that paralleled the first, Beres built on the seed treatments by integrating seeding rate and seed vigour at the same 20 site-years. He used two seeding rates of 200 and 400 seeds per metre square (approximately 1 bushel and 2 bushels per acre seeding rate), three seed sizes to approximate seed vigour (light, un-sized and heavy seed), and a Raxil WW (dual fungicide/insecticide) seed treatment. Consequently, he ended up with a range of agronomic systems from weak (low seed rate, small/thin seed, no seed protection) to superior (high seed rate, heavy/plump seed, dual seed treatment).

Winter wheat seed that included a dual (fungicide + insecticide) treatment improved plant stand, winter survival and yield. The positive effect of seed treatment for yield was significant only for the lowest seeding rate. However, a plot of mean grain yield vs. the coefficient of variation indicated that seed treatments generally produced higher, more stable yields. The worst approach was to use poor, untreated seed with a low seeding rate.

“The seed treatment helped overcome some issues like poorer vigour seed and lower seeding rate, but I wouldn’t want growers to look at the results and say I can skimp on seeding rates if I use a seed treatment. When you look at photos of the plots, I think they tell the whole story. Sound agronomic practices along with seed treatments can give you the best stand establishment and over-winter survival,”

explains Beres. “With winter wheat, that is what you are aiming for. I think a seed treatment such as Raxil WW is needed for stability and is good insurance, but I wouldn’t recommend it just to compensate for poor agronomic practices.”

Beres goes on to explain that the two trials were implemented using other recommended management practices such as seeding at the appropriate time of the location, seeding into standing stubble with a no-till drill, and taking care of pre- and post-seed weed control. “If you are pushing any of those recommendations, then I think it is even more important to use an integrated approach that includes Raxil WW.”

Summing up, Beres says that using an integrated approach to winter wheat stand establishment has been shown to increase yield and yield stability. Combining a dual fungicide/insecticide treatment along with high seeding rates and vigorous seed can pay off. A fall foliar application has reduced disease loads on plots with and without stripe rust infections in the fall, although the economics of applying a foliar fungicide are tight.

“I think using a dual seed treatment with high seeding rates makes a lot of sense. For the foliar application, I think if stripe rust is present, there may be a case for a foliar application, but there is still lots to answer regarding how much of a benefit it is,” says Beres.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 6

Brenzil also notes that 20 years later, in the mid-1980s, Ken Kirkland, a researcher at the Scott Experimental Farm, did some work on the timing of 2,4-D applications for the control of stinkweed and flixweed. He found that applications made in late fall and early spring were the most effective, whereas applications in early fall missed some late germinating plants, and in late spring the winter annual plants were too big to be controlled effectively.

“With respect to winter annual broadleaves, the application of a phenoxy herbicide (2,4-D; MCPA) late in the fall, which mimics the plant’s own hormones, provides a signal to the plant to continue to grow when it should be entering dormancy for the winter, thereby reducing its cold tolerance and forcing it to expend energy resources that it will need for winter survival,” says Brenzil.

Additional research conducted by Sapsford on pre-seed burndown timing provides guidance on which fields may benefit the most from post-harvest weed control. He found that early pre-seed control of winter annuals with a glyphosate application in the spring gave the best weed control and highest yield, even when seeding was delayed for several weeks. But if the pre-seed burndown was delayed until late May, the late seeded crop had a statistically lower yield – winter annuals caused the yield loss. The research was conducted in years in which soil moisture was relatively good, showing that yield isn’t always strictly relative to moisture and that competition for other resources – nutrients and sunlight – can also have an impact.

“If you are delaying your spring pre-seed burndown on later-seeded cereal fields, you could be losing yield. A fall application with products that have residual control would be a good strategy, because they control those winter annuals in the fall and have some residual activity in the spring,” explains Sapsford. “You’ll know the winter annuals won’t be there in the spring, so you’ve helped to eliminate that weed competition.”

Sapsford says the fall application doesn’t necessarily eliminate the spring burndown on later seeded crops because spring germinating volunteer crops, wild oats and green foxtail will still need to be controlled prior to seed-

ing, but those can be easily done with a spring burnoff just prior to seeding those later crops.

In addition to 2,4-D and PrePass (florasulam + glyphosate), glyphosate + Express Pro, is also labeled for extended weed control with a post-harvest application.

Glyphosate + Express SG does not have a re-cropping restriction. It is a good choice for pulse, oilseed and special crops for fall weed control.

Mostly, cereal crops can be grown after any post-harvest herbicide application. Cereals have very good tolerance to 2,4-D. Research at the University of Saskatchewan also found that the lowest rates of 2,4-D can be used in the fall before planting beans, peas, lentils and chickpeas the following spring. Flax and canola should not be planted after a fall 2,4-D application. Wheat and barley can be grown after Express Pro, and wheat, barley and oats can be grown after PrePass XC.

Pulse, oilseeds and specialty crops are more sensitive to fall-applied herbicides, and growers should check labels for re-cropping restrictions.

Another approach in some farming systems is the original soil residual herbicides that can be used in the fall prior to many crops: Avadex (triallate), trifluralin (Treflan et al,) and Edge (ethalfluralin). They still have a fit for broad-spectrum weed control when applied in the fall.

Given the choices in herbicides and cropping restrictions, a post-harvest weed control application makes the most sense on fields where later seeded cereal crops will be planted. In these crops, the weed control recipe includes a post-harvest herbicide application with residual control of dandelions and winter annuals, followed up with a late-spring, preseed burndown just prior to seeding later in the spring. This approach can clean up tough weeds in the fall, reduce weed growth in the spring, take pressure off the timing of early season burndown applications and set the crop up for a weed-free start. Just remember to check the label for any cropping restrictions.

See our pull-out chart ‘Herbicides registered for post-harvest weed control’ in this issue.

by Carolyn King

Soil salinity is surprisingly common on the Canadian Prairies, with some estimates indicating about 30 per cent of Prairie agricultural land is either saline or at risk of becoming saline. A key weapon in the battle against this yield-liming soil condition is the Salinity Tolerance Testing Facility.

Since it opened in 1988, this Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) facility has been providing practical results for Prairie farmers – from evaluating the salt tolerance of a wide range of crops, to improving crop recommendations for saline soils, to selecting salt-tolerant breeding lines for better grain and forage varieties.

Salts occur naturally in many of the geologic materials on the Prairies, because, about 100 million years ago, oceans covered much of the region and left behind marine salts. Surface and ground waters can dissolve, carry and deposit those salts. A combination of factors, such as precipitation amounts and subsurface water flow patterns, can cause salts to accumulate in certain areas. High salt concentrations in the root zone hinder the uptake of water and nutrients by plant roots, reducing crop yields.

Severely saline areas have white salt crusts on the soil surface most of the time, with yield reductions of 25 per cent or more. Although moderately to slightly saline areas don’t usually have

these salty crusts, crop yields can still be significantly reduced. The degree of impact on a specific crop variety will depend on its salt tolerance.

“The Salinity Tolerance Testing Facility was the original idea of Dr. Harold Steppuhn, a hydrologist who has now retired,” says Ken Wall, a senior technician who worked with Steppuhn for about 30 years at AAFC’s Semiarid Prairie Agricultural Research Centre (SPARC) at Swift Current, Sask., where the testing facility is located.

“Dr. Steppuhn’s objective was to design and fabricate a worldclass salt tolerance testing facility primarily for Canadian crops because, historically, many of our crop salinity tolerance recommendations for Canadian agriculture had been extrapolated from studies at the United States Salinity Laboratory in Riverside, California.” Differences in climate, bedrock chemistry, soil characteristics, crop choices and other factors mean that crop responses in salt-affected Prairie lands can differ from those in the United States.

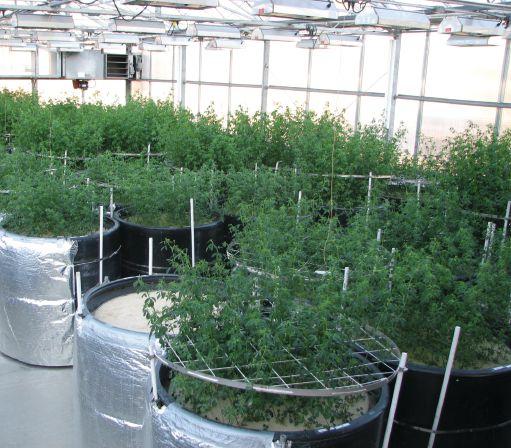

“With the completion of our facility, it became one of only two such facilities in North America. And there are only one or two ABOVE: Camelina and canola are grown under different salinity concentrations in the large grow tanks at AAFC’s facility to assess their salinity tolerance.

other ones in the rest of the world. So it’s really a unique facility,” says Wall.

The facility is capable of testing crops at three growth stages: germinating seeds in a growth chamber; seedlings in a screening facility capable of testing hundreds of genetic lines simultaneously; and mature plants in large sand grow-tanks. The temperature-controlled facility is designed to precisely control root-zone moisture, nutrient and salt levels.

The accurate control of salt concentrations makes the facility vital for salinity tolerance research. That’s because such control is almost impossible under field conditions.

“Salinity tolerance testing in a field environment can be complicated by variable soil profile conditions, such as texture and available moisture, nutrients and salt content in the soil. Under extreme conditions, salinity levels in western Canadian soils can vary from slight to very severe within a few metres, making replicated field trials very difficult,” explains Wall. “The level of root-zone salinity also varies with time and changes in the weather. Root-zone salt concentrations increase or decrease in response to the infiltration of water from rainfall or snowmelt and to the loss of soil water by evaporation. So when you do testing in the field, it’s really difficult to know exactly what the plants are facing at any given time.”

The Salinity Tolerance Testing Facility has achieved many valuable results for producers over the past 26 years. For instance, one of the first tasks of Steppuhn, Wall and others at the facility was to start measuring the salinity tolerance of Prairie crops to provide

crop recommendations. Over the years, they have tested many grain crops, such as several classes of wheat including durum and barley, and canola, field pea and several mustards, as well as forage crops, such as alfalfa and various wheatgrasses, and new crops such as camelina.

One of the surprising findings from this work is that canola has fairly good salinity tolerance – better than wheat’s tolerance and similar to barley’s (see Table 1). “Compared to barley, canola is a little trickier to establish in saline areas because it is seeded shallower and there is [more fluctuation in salt content] in the top 0.5 to 0.75 inches of the soil profile. With barley you can seed it down to about 1.5 inches, so it’s insulated from some of the salts moving up and down at the surface. But once you get canola established, it is just as tolerant as barley,” notes Wall.

“We also discovered that hybrid canola has more tolerance than conventional canola, and that camelina, although drought-tolerant, is significantly less salt-tolerant than canola.”

A major achievement through research at the facility was Steppuhn’s pivotal work on crop yield response to root-zone salinity. According to Wall, the common thinking back in the 1980s was that soil salinity didn’t really affect a crop’s yield until the salt concentration reached a certain critical level, and then yield declined in a linear fashion as the salt concentration increased above that critical level.

“For several years, we tried to get that response in the different crops we were testing, and we just didn’t find it…. [In fact,] we noticed, even at very slight levels of salinity, there is an effect on yield almost immediately with many of the annual crops that we

Table 1. Examples of Salinity Tolerance Indices from work at AAFC’s Salinity Tolerance Testing Facility

*The higher the value, the greater the crop’s salinity tolerance. Source: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada 2013 in Prairie Soils and Crops Journal (http://www.prairiesoilsandcrops.ca/articles/ volume-6-5-screen.pdf)

grow across the Prairies,” says Wall. “Ultimately Dr. Steppuhn discovered that a curvilinear function more accurately described crop response to salinity. This led him to rework many of the results from the U.S. Salinity Lab and to publish two papers that have become the standard in salinity research.”

The Salinity Tolerance Indices calculated with Steppuhn’s equation provide a more accurate assessment of a crop’s salt tolerance. So farmers have a better tool to use when choosing crops suited to the salt levels on their own land.

In recent years, work at the facility has increasingly involved testing of breeding lines to help in developing salt-tolerant varieties. “One example is some recent research with Dr. Surya Acharya, a plant breeder at [AAFC’s] Lethbridge Research Centre. We developed an alfalfa population with superior tolerance through several mass selections and outcrosses with salinity-tolerant selections conducted in the salt lab. As a result of this collaboration, the alfalfa variety Bridgeview was released in 2011,” says Wall. “Also, another new release from Dr. Acharya, called Kehoe, and several American [dormant-type] alfalfa varieties have been tested for salt tolerance in the facility prior to their release in Canada.”

Another important example is the development of AC Saltlander. Wall explains that this salt-tolerant green wheatgrass variety was developed from seed of a natural hybrid originally from Turkey. “Dr. Steppuhn obtained the seed from the Agricultural Research Station at Logan, Utah. We did selections for resistance to rootzone salinity, winter hardiness, uniform plant colour, vegetative vigour, leafiness, seed set and freedom from plant pests. All these tests were conducted at the Salinity Tolerance Testing lab. And in 2006 AC Saltlander was released,” he notes.

“It is one of the most salt-tolerant grasses available, giving producers another valuable tool in economically utilizing some of these salt-affected lands. AC Saltlander is really starting to take off, as farmers are discovering just how salt-tolerant it actually is.”

Selecting salt-tolerant breeding materials is the facility’s main mandate for the future. “Rather than the plant physiology of salin-

ity, the facility will be more focused on germplasm improvements and better varieties. And with the [DNA] marker technologies that are coming along in plant breeding, it is really going to open up use of that facility so we can make much better selections for salinity tolerance. So the facility will support the work of our breeders and genomic scientists going forward,” says Dr. Paul McCaughey, AAFC’s director of research, development and technology transfer in Saskatchewan.

McCaughey gives a couple of examples of current projects at the facility, which are related to new Prairie crops for semiarid conditions. “One is Camelina sativa, commonly known as camelina. It is an oilseed crop and it is being targeted for industrial purposes. Camelina will probably end up being grown on some more marginal soils, some of which could be affected by salinity.

“The other one is an industrial mustard crop called Brassica carinata; it’s often called Ethiopian mustard. We are likely to see this crop grown in the southern parts of Saskatchewan, outside of the canola-growing areas. It’s going to have many of the advantages that canola has, but it is more tolerant of drier conditions. It will also end up being exposed to saline soils.”

Testing at the facility to evaluate many different lines of these two crops will enable breeders to include salt tolerance along with other agronomic and quality traits, and eventually create improved varieties of camelina and Brassica carinata that are even better suited to tough growing conditions on the Prairies.

For more than two decades, work at the Salinity Tolerance Testing Facility has provided practical results for Prairie producers with salt-affected lands. The facility’s increased focus on development of salt-tolerant varieties is aimed at continuing to provide valuable benefits.

Wall emphasizes the importance of this varietal development work, given the millions of hectares of Prairie agricultural land that are prone to saline conditions. For instance, he says an estimated 10 million hectares have slightly to moderately saline soils or are at risk of becoming saline. “If you can increase the salt-tolerance of crops like camelina, wheat or canola, to increase the yields in slightly to moderately saline areas even by four per cent, it’s easy to see the economic advantage that would have for Prairie growers.”

Rethink Your Phos

Providing your crop with an early supply of phosphorus is not as simple as applying a standard rate of P2O5 every year. Take control of the phosphorus, zinc and other nutrients that your crops need for a strong start with a new fertility tool, Nu-Trax™ P+.

Plants crave phosphorus early. Scientific research shows that plants have an insatiable appetite for phosphorus early in the season with rapid uptake occurring at this stage.

Satisfying your crops early phosphorus hunger sets the stage for a more fibrous root system that is better able to access the nutrition it needs later in the growth cycle. But two main challenges make it difficult for young plant roots to find and access that phosphorous:

1. Phosphorus is relatively immobile in soil, so plant roots need to grow to the P.

2. Phosphorus is easily tied up in soil. About 80% of traditional P fertilizers become unavailable to plants in the year of application.

“In cold and wet soil, which is common seeding conditions for Canadian farmers, root growth slows,” explains Mark Goodwin, director of research and product development for Compass Minerals. “This makes accessing P and other essential nutrients even more difficult for young seedlings.”

Provide

Nu-Trax P+ is a new fertilizer that can help you deliver the phosphorus, zinc and other nutrients your crops need for optimal early-season growth. Nu-Trax P+ brings together three patented technologies.

1. With the CropStart™ Nutrient Package, young plants get the right, scientifically-derived ratio of nutrients needed for a healthy start: phosphorus, zinc, manganese and nitrogen.

2. Featuring proprietary EvenCoat™ Technology, Nu-Trax P+ is easily coated onto dry fertilizer.

“Piggy-backing the Nu-Trax P+ nutrients on every fertilizer granule creates a consistent blend, allows for blanketlike distribution in the field and provides more points of interception for your crop,” says Goodwin. “Now seedlings can access the nutrients they need sooner, especially in cool, wet soil conditions.”

3. The unique PlantActiv™ Formulation is chemically and physically designed for better micronutrient availability, so nutrients get into plants quickly. Formulated as a fine powder, Nu-Trax P+ particle size is ideal for plant uptake.

Rethink Your Phos

Take control of your crop’s early-season nutrition. Just 2 pounds per acre of Nu-Trax P+ fertilizer puts you in charge of delivering the nutrition your crops need for a strong start!

Field trials show the benefits of better early-season nutrition.

“Trial results show an increase in plant emergence and seedling size,” says Goodwin. “Plants are more vigorous with longer, more developed root systems. The early-season growth translated to higher yields in these wheat fields.”

Location

Taber, AB

Application

2 lb/ac Nu-Trax P+

Results

• 59% larger seedlings

• +7 bu/ac yield

Location Vauxhall, AB Application

• +4 bu/ac yield Control Control

2 lb/ac Nu-Trax P+

Results

• 12% larger seedlings

Including short rotation forages captures N benefits and increases yields for subsequent grain crops.

by Donna Fleury

Crop rotations that include legume forages in rotation provide economic and environmental benefits to subsequent crops. Previous research and producer experience has found improved nitrogen (N) benefits, increased yields and other rotational benefits in these cropping systems. Producers also benefit from including forages in rotation to break pest, disease and weed cycles and other cropping problems.

In a recent project, researchers were interested in finding out if short-rotation legume forages (three or four years) could provide crop producers with an alternative cash crop such as hay or silage, and provide residual N benefits to subsequent cereal crops. This residual N could significantly reduce N fertilizer requirements and save producers money. Researchers wanted to determine the economic returns and measure the N benefits being realized from these rotations.

A four-year project was initiated in 2010 in Saskatchewan at four locations: Swift Current, Lanigan, Saskatoon and Melfort. “The objective of this project was to determine the amount of residual N from a two-year crop of alfalfa or red clover in a four-year rotation,” explains Dr. Paul Jefferson, vice president operations at the Western Beef Development Centre (WBDC) in Humboldt, Sask. The rotations included alfalfa-alfalfa-wheat-canola, red clover-red clover-wheat-canola, barley-pea-wheat-canola and a control barley-flax-wheat-canola.

The four rotations were seeded in 2010 in replicated plots at each of the four locations. The annual crops were harvested for grain, and perennial forages were harvested in the seeding year for hay yield and again in 2011 for hay and then terminated with herbicides. In 2011, a pea crop was included in the barley-pea-wheat-canola rotation to provide a comparison of a rotation that included an annual legume crop. In 2012, wheat was grown on all treatments, followed by Liberty Link (L130) canola on all treatments in 2013. The crop yield and N content of the wheat in 2012 and canola in 2013 were measured.

“No N fertilizer was applied to any of the four rotations in any years, except for some subplots in canola in 2013,” explains Jefferson. “We set up N subplots in 2012 in wheat and 2013 in canola at each location to calculate the N response for comparison. The subplots included treatments of zero, 40, 80, 120 and 160 kg of N per hectare. From these subplots, we used a regression analysis to calculate a response to N, which was then used to estimate an N fertilizer equivalent.”

The project results showed some very positive responses in terms

Third cut legume hay crop just prior to harvest in September 2011, alfalfa on the left and red clover plots on the right.

of yield and N fertilizer equivalents at most locations. The yield results for wheat at the Lanigan site in 2012 for all four rotations were 38 bu/ac after alfalfa, 43 bu/ac after red clover, 31 bu/ac after peas and 27 bu/ac after flax. For canola in 2013, the yield results were 32 bu/ac for alfalfa, 40 bu/ac for red clover, 30 bu/ac for pea and 25 bu/ ac for the control, which had no legumes or N fertilizer.

The N fertilizer equivalency was calculated for alfalfa, red clover and pea at the Lanigan site in 2012 for wheat and in 2013 for canola,

two years after these legumes were included in rotation. The fertilizer equivalency in wheat in 2012 was 92 lbs of per acre after alfalfa, 153 lbs of N per acre after red clover, and 149 lbs of N per acre after peas. For canola in 2013, the fertilizer equivalency was 40 lbs of N per acre for alfalfa, 70 lbs of N per acre for red clover and 25 lbs of N per acre for pea. The yield and N benefits were similar at Saskatoon, while the Melfort trials showed slightly higher yields and fertilizer equivalency measures.

“Strong drought conditions in 2012 at the Swift Current site impacted the N response in wheat in 2012, followed by little response in canola in 2013 except for the alfalfa rotation,” says Jefferson. “The results were consistent with earlier work we did in the early 2000s at Swift Current on perennial alfalfa-grass mixtures that were removed and planted to barley. The N benefit in the second year after removal was usually stronger than in the first year, which we determined to be related to water limitations. Therefore, the Brown soil zone may be limited in the use of these rotations because of dry soils or dry conditions in the first year after removing forages.”

The legume forages grown in the first two years of rotation produced high yielding, good quality hay harvests. At the Lanigan site, a seedling year harvest was done in 2010, and in 2011 three cuts were harvested on each plot yielding a total annual harvest of four tonnes per acre with very good quality at 70 per cent total digestible nutrients (TDN). These high-quality hay crops are suitable as an additional component of a wintering ration for a cow-calf operation or backgrounding calves and yearlings.

“We were very pleased with these results; however we are still working on the economics, which will be completed over the next few months in 2014,” says Jefferson. “We are also waiting for some lab analysis results from fall samples for plant N concentrations and soil N analysis. This work is being completed by Dr. Jeff Schoenau’s lab at the University of Saskatchewan. Once we receive the results, our beef economist Kathy Larson will complete the economic analysis so we will be able to put some numbers to the results and the benefits we know are there.”

Producers already recognize the benefits of forages in rotations, but don’t necessarily know how big the benefit is for N. There are examples of local area beef producers renting land from neighbouring crop growers to grow short rotation legume forages for two or three years for hay or silage, and then returning the land back to the

neighbour for annual crops. Part of the rental agreement includes a value of the N benefits derived from the forages and returned to the crop growers.

“Our research results are promising and indicate that short rotation legume forages can be a viable option, providing high quality feed, good yields and reasonable levels of residual N two years after legumes in the system,” says Jefferson. “Crop producers can get two years of annual crops after legume forages with either zero or minimal additional N fertilizer, which is a definite advantage at current fertilizer prices. Beef producers can get high quality hay for wintering cattle or backgrounding calves and yearlings from the two years of forages.

“We are looking forward to results of the economic analysis, which will provide some of those numbers needed to measure the N benefits being realized from these rotations,” he adds. “The results could help expand this community-wide integrated system of neighbouring crop and beef producers each taking advantage of and benefiting from these short rotation legume forage systems.”

The project was carried out with the Western Beef Development Centre at Lanigan in collaboration with the Wheatland Conservation Area at Swift Current, the Northeast Agriculture Research Foundation at Melfort and with Dr. Bruce Coulman, at AAFC in Saskatoon. Project funding support was provided through the Agriculture Development Fund, Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture.

WELCOME TO NEW

FLEXIBILITY, PROFITABILITY.

Make it NexeraTM and make more, NOW in more ways than one.

• Get healthier premiums, profits, demand for Omega-9 oils

• Healthier agronomics, profit to your potential either way

• New for 2015, the Nexera canola Flexibility Agreement TM

• Grow Nexera WITH OR WITHOUT a delivery contract

Researchers and volunteers test sclerotia-depot method for improving early disease forecasting.

by Donna Fleury

Anew, four-year pilot project launched in Western Canada will help improve disease forecasting and management of sclerotinia stem rot in canola. Developed in Denmark several years ago by Dr. Lone Buchwaldt, currently a researcher with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon, Sask., the sclerotia-depot method will be tested for the first time in Canada in the 2014 growing season.

“The sclerotia-depot method was used successfully in Denmark for many years and proved to be very reliable for forecasting sclerotia germination,” explains Buchwaldt. “We want to evaluate the usefulness of this method in Canada, either as a stand-alone risk assessment tool or in combination with the existing sclerotinia stem rot checklist available from the Canola Council of Canada. The project will continue to the end of 2017 and will be tested across Western Canada.”

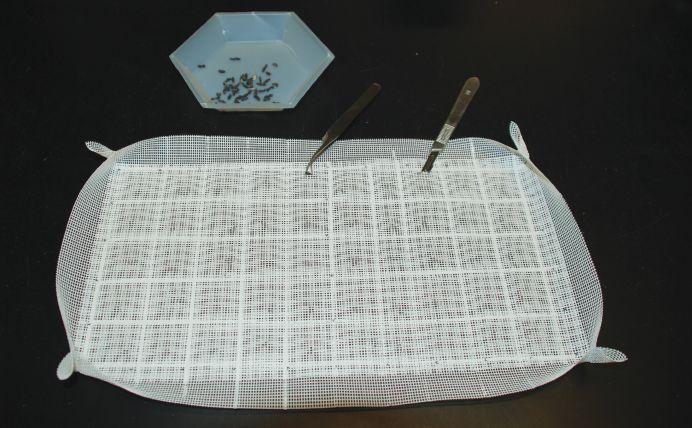

For the 2014 growing season, a total of 37 volunteers have established 67 sclerotia-depots in Saskatchewan. A depot is made from two layers of nylon mesh heat-sealed together to produce 50 compartments of 5 x 10 rows. Each compartment contains a sclerotium, which is a resting body of the fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum that can germinate with spore-bearing apothecia under the right

The next generation of Canadian agricultural leaders is growing, and CABEF is proud to support them. Congratulations to these six exceptional students who have won $2,500 CABEF scholarships. Based on their applications, the future of the agriculture industry is in great hands.

Six more $2,500 scholarships will be awarded to grade 12 students in April 2015.

weather conditions. These spores typically colonize petals lodged on the plant, causing stem rot in canola. The depots were put into the ground for overwintering in the fall, and in the spring they were placed in selected canola fields where they are now being monitored. Sclerotia-depots are managed by volunteers primarily involved with extension work in the public or private sectors and a number of canola growers. They monitor the depots and report per cent sclerotia germination via the Internet using a mobile device or personal computer.

“We ask volunteers to go out once a week before the canola crop begins to bloom to observe and submit per cent sclerotia germination,” explains Buchwaldt. “Once the crop begins to bloom, we ask volunteers to go out every two or three days, particularly if apothecia are forming. The sclerotia will germinate with spore-bearing apothecia once the canola canopy shades the soil surface and only under cool, wet weather conditions. If apothecia begin to form, we need to have as up-to-date reports as possible. Our staff at AAFC are updating the data daily during the week, so that real time sclerotia germination data is available across the province.”

The data from all sclerotia-depots are available from June to July, or as long as canola is flowering, through SaskCanola’s website www.saskcanola.com (go to the Research page and select Sclerotinia risk assessment) and is shown on the per cent sclerotia germination map. The timing and rate of sclerotia germination in a depot

is assumed to be correlated with natural sclerotia germination in the surrounding canola fields. Since weather conditions vary over short distances, a 10-kilometre (six mile) radius from a depot is tentatively set as a cut-off for this correlation.

The sclerotia germination data can be used with the sclerotinia stem rot checklist to calculate the risk at a field-specific level and make decisions as to whether or not a fungicide application is warranted. A new, interactive sclerotinia stem rot checklist is available on the SaskCanola website and is a modified version of the original checklist with the regional risk for apothecia development modified to per cent sclerotia germination in a local sclerotia-depot.

“This last question on the checklist relates to apothecia germination, and can be difficult to determine,” explains Buchwaldt. “The sclerotia-depot method should result in a more accurate number for the risk calculation. The total risk point for the six risk factors on the checklist is calculated automatically, with 40 risk points, as suggested in the original checklist, still the recommended threshold for applying a fungicide. We encourage growers to continue using the checklist along with the depot tool for the best overall assessment for their fields.”

As part of the evaluation of the sclerotia-depot method, Buchwaldt will be collecting data from fungicide trials and demonstration sites. Sclerotinia severity and yield data from sprayed and un-sprayed areas will be used to compare the relationship between yield loss and per cent infected plants, as well as the actual yield gain from a fungicide application. “We would like to

improve the economic threshold estimate and will be developing another interactive calculator that will help growers determine a specific economic threshold based on factors such as per cent infection, cost of fungicide and application and the price of canola,” adds Buchwaldt. “All of these tools together should improve early forecasting and risk assessment, and the recommended threshold for applying a fungicide.”

Buchwaldt is seeking volunteers from across Western Canada to manage a depot in canola for the 2015 growing season. “We ask volunteers to contact us as soon as possible, as we would like to make arrangements to have all of the depots sent out and in place by October before frost. We are also asking volunteers if they can provide data from nearby sclerotinia fungicide trials as well.”

For more information about volunteering contact: sclerotia.depot@agr.gc.ca.

One additional aspect of the research project is a collaboration between AAFC and Weather INnovations Consulting LP (WIN), a private company involved in weather-based modelling of disease risk in various crops and decision support systems. “WIN has established weather data stations across Canada, with about 300 stations in Saskatchewan for example,” says Buchwaldt. “We will pick the stations closest to the sclerotia-depots and model the relationship between the weather data and the sclerotia germination data.”

With the data collected over the next three growing seasons, the objective is to develop a predictive computer model for the germination stage of the pathogen lifecycle. The model will be tested against actual field data to confirm the accuracy.

Buchwaldt adds they also plan to test another model developed in Germany that can predict infection hours. “Once the spores have landed on the plant or petals, the model uses climate data to determine whether or not the conditions are right for infection of the stem by sclerotinia spores. We hope by the end of the project to have better prediction capability for growers for sclerotinia in canola. The combination of real-time sclerotia-depot data and computer forecasting tools should help growers make more accurate risk assessments and better economic decisions for fungicide application.”

For more on disease management, visit www.topcropmanager.com.

Fall application of nitrogen (N) fertilizer can range from very effective to very disappointing.

by Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P. Ag.

The effectiveness of fall fertilizer applications depends on a number of factors, including the form of nitrogen (N) fertilizer used, how the fertilizer is applied and, most important, the environmental conditions after application including soil moisture and temperature.

Fertilizer nitrogen basics

The four most common nitrogen fertilizers used in Western Canada are urea 46-0-0 [CO(NH2)2], anhydrous ammonia 82-0-0 [NH3], liquid N 28-0-0 which contains half urea and half ammonium nitrate [ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3-)], and ESN 45-0-0 [Environmentally Smart Nitrogen – slow release urea with a polymer coated granules]. When urea and anhydrous ammonia are banded into warm, moist soil, both convert to ammonium [NH4+]. Ammonium is positively charged and is relatively immobile in soil and will not leach under wet conditions. In warm, moist soil, specific bacteria will convert ammonium to nitrate over a two- to three-week period. This process is called nitrification. Nitrate is negatively charged, is mobile in soil and

will leach with excess precipitation, particularly in sandy soils.

Banding ammonia or urea creates an environment near the band that slows the activity of bacteria that convert ammonium to nitrate, delaying nitrification. When urea or anhydrous ammonia are banded in late fall after the soils have cooled and micro-organism activity has slowed, most of the fertilizer N remains in the ammonium form over winter until the soil warms up in the spring. Over the winter and in the early spring, when soils are cold, the ammonium form is relatively stable and won’t leach.

However, if urea or anhydrous ammonia fertilizers are banded in early fall when soils are still warm and moist, much of the ammonium can potentially be converted to nitrate before freeze-up. Excess precipitation in late fall or spring could then cause the nitrate to leach below the crop root zone or be lost due to a process called denitrification. The denitrification process occurs after N fertilizer has converted to

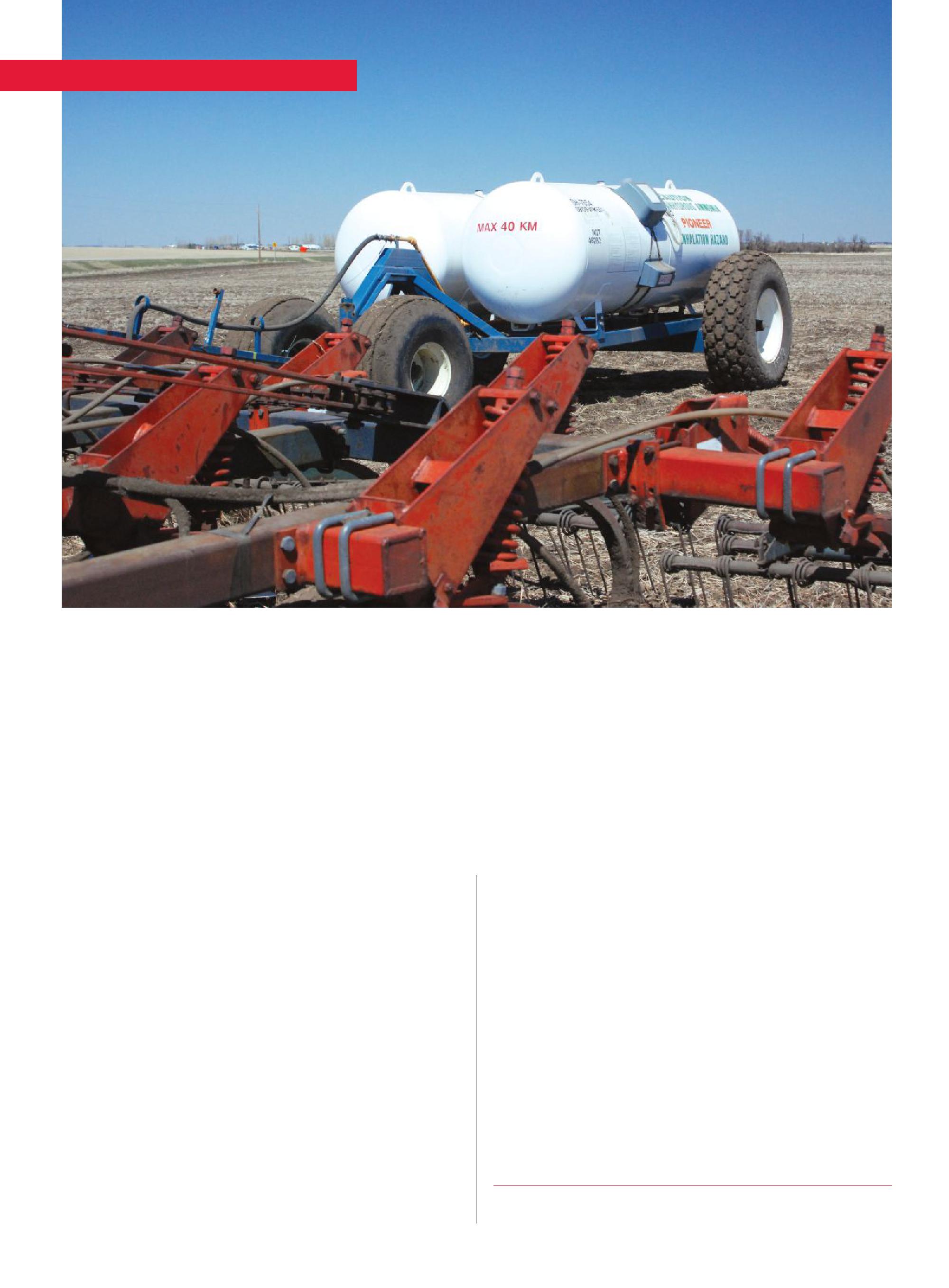

ABOVE: Fall banding of anhydrous ammonia can be effective, under certain conditions.

The New 9R/9RT Series Tractors are ready for anything

Power and effciency are what defnes the new 9R/9RT Series. Start with a new 620-engine hp model and a 10-engine horsepower increase across all models. Then add the FT4 engine technology, and regardless of which of the 16 models you choose, you have plenty of get-up-and-go with less fuid consumption. The new industry-exclusive HydraCushion Suspension, available on wheeled models, helps mitigate power hop and road lope. The 9 family also has the new CommandView™ III Cab which has more space, visibility, and convenience than the our previous cab. It also features the new CommandARM™ and CommandCenter Display designed to improve effciency and give real-time insight into daily operations and machine performance. We’re still not done. The new e18™ Transmission, increased hydraulic capacity (up to 115 gpm), and an LED lighting package add to the list of impressive features. Visit your John Deere dealer today and sit behind the wheel of the new 9R/9RT Series because Nothing Runs Like A Deere™ .

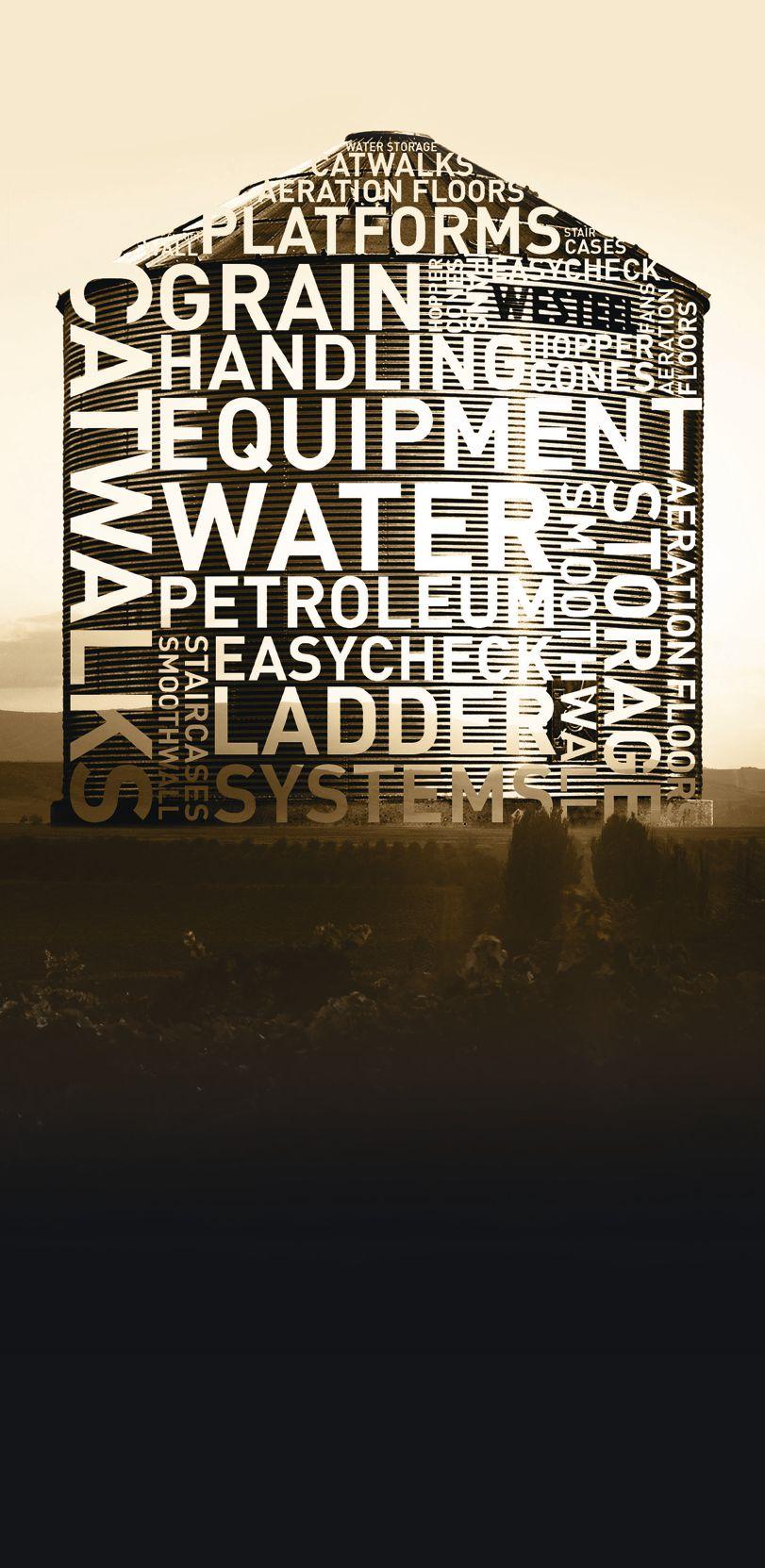

Table 1. Fall-applied N as a per cent of spring broadcast and incorporated N

Dry: Well-drained soils that are seldom saturated during spring thaw.

Medium: Well- to moderately-drained soils that are occasionally saturated during spring thaw for short periods.

Wet: Poorly- to moderately-drained soils that are saturated for extended periods during spring thaw. Irrigated: Well-drained soils in southern Alberta that are seldom saturated during spring thaw.

Source: Adapted from Alberta Agriculture Agdex: 541-1.

nitrate, the soils are warm and soil conditions become saturated after snow melt in spring or due to heavy precipitation events and soils. Soil nitrate-N is lost when microorganisms in anaerobic conditions (saturated soil without oxygen) convert nitrate N to nitrous oxides which is a gaseous form of N that is lost to the atmosphere.

Research has shown that denitrification can occur in virtually all western-Canadian agricultural soils. Denitrification is caused by many different types of soil bacteria that use the process to obtain oxygen from nitrate, when oxygen is in short supply in very wet soils.

All soil types and regions of the prairies are susceptible to losses of fall-applied N fertilizer. However, the risk of N loss is typically highest in regions with moister climates, causing soils to be more frequently saturated with water, such as the Black and Gray soil zones. Denitrification is usually lowest in regions that tend to be drier, such as the Brown and Dark Brown soil zones.

Nitrogen losses in drier regions are usually low, and, therefore, fall-banded N is usually as equally effective as spring-banded N (see Table 1). However, N losses can still be high even in low-risk regions, after heavy precipitation events. Each fall, farmers must look at their specific environment conditions on their farms to weigh the risks versus benefits of fall fertilizer application. In cases where spring banding causes a significant loss of seedbed moisture, fall banded N can produce a higher yield than spring banded N. Nitrogen fertilizer applied in the fall can be very effective on well-drained land, but can be totally ineffective in poorly drained soils and low-relief soils that tend to be wet for extending periods during the spring. Even during drier springs, localized lower areas in fields that are wet are subject to denitrification. It is important to remember that fall application always puts your fertilizer N at risk. Assess the level of risk first at the regional level based on typical long-term environment conditions and then based on specific, very local field conditions each fall.

Some general rules of thumb to consider:

• Spring banding can be the more effective method of application, and fall broadcast the least effective when soils are wet for longer periods in the spring or if land is moderately rolling with numerous low areas that stay wet for prolonged periods.

• Late fall-banded N can be as effective as spring-banded N, if there is no extended period of saturated soil conditions in the spring.

• Fall-banded N can be more effective than spring-banded when springtime seedbed moisture is limited, and spring banding would dry out the seedbed.

General tips to consider before fall banding N:

• When soils are poorly drained and tend to be saturated with water for extended periods in the spring, then fall application is generally not a good option. However, if saturated soil conditions are normally not a problem, fall banding can be an effective N application method.

• Generally under lower-risk conditions, such as in the Brown and Dark Brown soil zones, anhydrous ammonia (82-0-0) and urea (46-0-0) perform equally well when properly fall banded. However, if soils tend to be alkaline (soil pH >7.5), losses through ammonia volatilization can occur if the bands are too shallow or the soil is dry and cloddy.

• Apply a conservative N fertilizer rate of about 75 per cent of the crop requirement in the fall. This reduced fall rate is a hedge against potential over-winter losses, low spring moisture or lower crop prices in the following spring. If conditions look favourable in the spring, additional N can be applied at seeding.

• Avoid the use of the nitrate-containing fertilizer products for fall application such as 28-0-0, as the nitrate is subject to both denitrification and leaching losses under wet conditions in late fall or spring conditions.

• Apply N as late as possible in fall after the soil temperature has dropped below 5 to 7 C and the nitrification process has slowed down.

• It is best to band and not broadcast/incorporate N fertilizer. Banding restricts the contact between soil and fertilizer, concentrating the band delays nitrification. Consequently, over-winter N losses are lower with banded than with broadcast/incorporate N.

Fall fertilization shifts the workload from the hectic spring to the fall. This can increase spring seeding operation efficiency by applying the majority of N fertilizer in fall, and fertilizer handling in spring is reduced at seeding.

Nitrogen fertilizer prices tend to be lower in the fall than in the spring, providing an economic advantage with fall versus spring fertilization. Generally, soils also tend to be drier in the fall than in the spring, reducing potential for soil compaction problems.

It is always wise to get several opinions from experts in your region, including your fertilizer dealer, industry agronomist and government agronomist, to consider all the pros and cons of fertilizing in the fall before you make a final decision

Grain Guard’s new line of 4" wide corrugated grain bins are manufactured using state-of-the-art technology and are available in diameters from 15' to 105' in flat bottom models, as well as 15' to 27' in hopper bottom models. With an established catalogue of aeration and conditioning equipment, high-quality grain storage bins are yet another solution provided by Grain Guard.

Grain Guard also offers turnkey construction packages on all flat bottom bin models. Trust the storage and conditioning experts to be your one-stop shop.

Syngenta now offers two canola seed hybrids. When you buy them, you know you’re getting quality seed that lives up to your high expectations. And, because they’re from Syngenta, you know you’re getting a whole lot more.

Deficiency of a single nutrient can impair healthy plant growth.

by Dr. Rob Mikkelsen

We are familiar with the concept of preventative medicine, where health problems are avoided by good practices instead of curing sickness after they occur. This same concept applies to damage caused to crops by plant diseases and pests when adequate and balanced nutrition is lacking.

Each nutrient in plants has unique and specific functions that operate in an intricate balance of physiological reactions. A deficiency of a single nutrient will result in stress that impairs healthy plant growth. Until the symptoms of deficiency stress become visible, the hidden roles of proper nutrition in maintaining plant health are too frequently overlooked.

New scientific studies are again confirming what farmers have known for many years about the link between plant health and nutrition. Healthy plants can generally withstand stress and attack better than plants that are already in poor condition. For example, recent work with corn has demonstrated the link between

an adequate potassium (K) supply and increased leaf thickness, stronger epidermal cells, and decreased leaf concentrations of sugars and amino acids. All of these factors lower the attractiveness of plants for pests, such a spider mites.

The link between adequate K and soybean aphids has also been recently reconfirmed. Research shows that K-deficient soybeans tend to transport more nitrogen-rich amino acids in the phloem, making them a favored target of stem-sucking aphids.

The link between plant nutrition and disease control generally falls into one of these categories where proper fertilization can: Reduce pathogen activity: Proper mineral nutrition can slow or inhibit the germination and growth of a variety of plant pathogens in soil and in plant cells.

Modify the soil environment: The selection of a nitrogen

ABOVE: Crop nutrition can help compensate for foliar disease damage.

(N) source can temporarily modify the rhizosphere pH during critical periods between germination and seedling establishment. Likewise, the addition of elemental sulphur (S) is a common practice to acidify the root zone of some crops for disease control.

Increase plant resistance: Healthy plant tissues are less susceptible to infection. Proper nutrition can stimulate the production of physical and chemical defenses to cope with pathogens.

Increase tolerance to disease: Adequate nutrition can help plants compensate for disease damage and to sustain a high level of natural compounds that inhibit pathogen growth within plant tissue.

Facilitate disease escape: Plants that are adequately fertilized with boron (B) and zinc (Zn) have been shown to have fewer fungal spores that break dormancy on the roots, compared to deficient plants. A healthy photosynthetic capacity also allows for a quick growth response to a pathogen invasion.

Compensate for disease damage: An adequate supply of plant nutrients is closely linked with vigorous root growth and photosynthetic activity. These healthy plants can better tolerate increased disease burdens than plants stressed by nutrient deficiency.

Nutritional and environmental stresses often trigger greater pest and disease damage to crops. While proper fertilization does not eliminate the risk of pests and diseases, it provides an important degree of protection from many yield-robbing factors.

Effective disease and pest management through proper plant nutrition improves crop quality and contributes to provide a safe, abundant, and nutritious food supply.

Dr. Rob Mikkelsen is Director, Western North America, International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI). Reprinted with permission from IPNI Plant Nutrition Today.

Lower seeding rates and using seeding mixtures show potential.

by Bruce Barker

AC Saltlander green wheatgrass has been enthusiastically received because of its salinity tolerance, which is equal to tall wheatgrass. With the potential to compete with foxtail barley at all salinity levels, AC Saltlander can reduce herbicide costs and provide good forage yields on saline soils measuring into the severe range.

But while AC Saltlander can produce good forage yields, seed yields are generally low. As a result, seed prices for AC Saltlander are generally double the price of slender wheatgrass, crested wheatgrass and smooth bromegrass – although these varieties have lower salinity tolerance.

“The high cost of seed can be a barrier for farmers wanting to establish AC Saltlander on their saline soils. Salinity isn’t going away, and with all the rainfall in recent years it may even be getting worse,” says Ken Wall, a technician at the Semiarid Prairie Agriculture Research Centre (SPARC) at Swift Current, Sask.

Wall was part of two research trials that studied the effect of seeding rates and seeding mixtures on stand establishment and yield, in the hope that the establishment costs of AC Saltlander could be reduced. The current recommended seeding rate for AC Saltlander is 10 lbs/ac.

In the first test on severely saline soil, AC Saltlander was sown in a mixture with Revenue slender wheatgrass. The site received a pre-seed application of glyphosate, and was cultivated and harrow-packed. A disc-drill forage plot-seeder with six discs spaced 12 inches apart was used to seed each plot. The plots were seeded on May 12, 2009, and received an application of Pardner herbicide at 0.4 L per acre on June 30, 2009.

There were three seed mixture treatments:

• Seeding mixture #1: AC Saltlander green wheatgrass was seeded in alternate rows with Revenue slender wheatgrass at rates of 5.5 lbs/ac, and 3.6 lbs/ac respectively.

• Seeding mixture #2: AC Saltlander green wheatgrass was mixed

together with Revenue slender wheatgrass within rows and seeded at rates of 5.5 lbs/ac and 3.6 lbs/ac, respectively.

• Seeding mixture #3: AC Saltlander green wheatgrass was mixed together with Revenue slender wheatgrass within rows and seeded at the full rates of 10.6 lbs/ac and 7.3 lbs/ac, respectively. These rates would be applied if each crop were seeded as a monoculture.

Wall explains that slender wheatgrass was used in the mixture because of good salinity tolerance, rapid establishment, good forage quality and low-cost, readily available seed.

“Slender wheatgrass is a bunch grass that is relatively short lived, especially under saline conditions. AC Saltlander has a creeping root system. We thought that if we planted them in a mixture, the slender wheat grass could provide good forage yield and weed competition for a couple years, while the AC Saltlander would eventually grow to fill in the stand,” explains Wall.

Ideal growing conditions in 2009 resulted in excellent stand establishment. The plots were not harvested in the year of establishment, and three subsequent harvests were conducted in 2011, 2012 and 2013. In 2013, subplots were hand-harvested in each plot. Foxtail barley and the green wheatgrass biomasses were separated, oven dried and weighed.

No significant differences in forage yield were recorded among the treatments in each growing year. With the very good stand establishment, the grasses competed very well with foxtail barley, and virtually no foxtail barley was present in the plots.

“In this test, we were able to reduce the establishment costs by cutting AC Saltlander seeding rates in half and replacing it with the lower cost slender wheatgrass,” says Wall. “By the end of 2012, due to the high level of salinity and competition from the green wheatgrass, all the slender wheatgrass had died out.”

ABOVE: Stand establishment comparing four seeding rates.

In the second test on severely saline soil, a seeding rate trial was conducted using seeding rates of 2.5, 5, 10 and 15 lbs/ac of AC Saltlander seed. The plots had a pre-seed glyphosate burndown, and were cultivated and harrow-packed. The plots were seeded with a plot-seeder with six discs on 12-inch row spacing. The plot was seeded on June 16, 2011. The plots received an application of 2,4-D at 0.38 L per acre on June 1, 2012, to control kochia.

During the establishment year, Wall says the growing conditions favoured kochia and foxtail barley growth, and resulted in significant competition with the emerging AC Saltlander. Plots were harvested in 2012 and 2013.

In 2012, no significant differences in forage yield were observed between the seeding rates. Kochia had been eliminated from the plots, but significant levels of foxtail barley were observed.

In 2013, the 2.5 lbs/ac seeding rate had significantly lower forage yield and significantly higher foxtail barley biomass. There were no significant differences among the 5, 10 and 15 lbs/ac seeding rate for AC Saltlander forage yield or foxtail barley biomass.

“Our big worry was that reduced seeding rates would come at a cost of increased foxtail barley. Except for the 2.5 pound rate, that didn’t happen,” says Wall. (See Fig 1.)

These results will be supplemented with an additional harvest in 2014, but the preliminary results indicate that it may be possible to reduce the seeding rate of AC Saltlander green wheatgrass to about five lbs/ac without affecting yields and allowing increased competition from foxtail barley on this severely saline site.

Researchers at Swift Current hope to conduct other research on AC Saltlander establishment practices to help make the wheatgrass even more accessible to farmers. They would like to see if zero-till with air seeders on nine-, 10- or 12-inch row spacing could be successfully done and at what seeding rate. Another approach would be to use a Valmar granular applicator with seed incorporation done with a rotary harrow. Since most saline sites are very wet in the spring, they would also like to research the success of fall dormant seeding.

“AC Saltlander has lots of potential, and if we can figure out ways to reduce stand establishment costs, and find ways to establish it without special seeding equipment, AC Saltlander definitely has potential to be a crop farmers can use to combat salinity,” says Wall.

Because “Good Enough” Isn’t Good Enough.

We don’t have to build each product stronger and heavier than it needs to be. We don’t have to offer everything in multiple configurations and sizes to meet farmers’ unique needs. And we don’t have to test each new design for hundreds of hours, and thousands of acres, before going to market. But if we didn’t...it just wouldn’t be a Summers.

A five-year study will determine the impact of cropping practices on blackleg pathogens and resistance.

by Donna Fleury

For many years, blackleg disease on the Prairies was managed fairly successfully through the use of disease resistant varieties and an extended rotation of three or four years between canola crops. However, since about 2009, researchers and agronomists have been seeing changes in the pathogen Leptosphaeria maculans that causes blackleg in canola and getting reports of more disease problems.

“We began receiving more reports of higher levels of disease and damage including fields with resistant cultivars/lines in southern Manitoba and northeastern Alberta, with some reports from adjacent areas in southeastern and northwestern Saskatchewan starting in 2009 and 2010,” explains Dr. Gary Peng, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon, Sask. “We have initiated several research projects since 2011 and are continuing our efforts to try to determine the reasons for some of these spikes, which can be quite complex.”

In 2013, a new, five-year project was initiated across the Prairies to look at the blackleg resistance strategy in relation to management practices in the field. Peng is collaborating with project lead Dr. Dilantha Fernando from the University of Manitoba and Ralph Lange with Alberta Innovates to work with about 25 farms in each province to help understand different management practices and the impact on blackleg pathogens and resistance in canola. This information will help understand what interactions and effects are playing a role in the maintenance/breakdown of resistance.

“With the three of us covering different provinces, we will be able to pool our information and have a bigger picture of blackleg resistance and the Prairie situation,” says Peng. “This project is very much a continuation of the research we have been conducting on pathogen race typing and population structure. The core of this project is to track the population of the pathogen and determine what is changing or what has changed in relation to the different farm operations. We also want to determine the potential linkage of that population change to the disease level we are seeing on those farms.”

In each province, 25 farms with different management practices were selected through collaboration with several retail outlets and field agronomists. For each farm, one quarter or half section fields of canola will be monitored each year of the project. Researchers will be following the canola crop over the time of the project and collect data from each of the fields every year including crop sequence, crop inputs and other practices. Researchers will also be

Blackleg/basal canker symptoms by harvest time.

estimating the overall disease severity in the canola crop, either at harvest or shortly after, as well as taking stubble samples from each field and analyzing the pathogen race composition in the lab.

“We are selecting several groups of fields in a five- to 10-kilometre region where the pathogen race composition may not vary that much, but with a range of fields and management practices in terms of shorter and longer rotations,” explains Peng. “Some growers use very short rotations, such as back-to-back or a oneyear break, while others may have up to a three- to four-year break in between. Most growers rotate the varieties they use each year to help reduce the risk of resistance breakdown.” The project will help provide information useful to the development of management strategies on a regional basis.

Peng adds that, so far, the severely damaged fields being reported are still fairly isolated cases. Researchers are interested in understanding why those fields are much more severely damaged than neighbouring fields – sometimes the same cultivar is only two or three kilometres away. About 95 per cent of those severely damaged fields have been short rotation fields, either back-to-back canola or only one-year break in between. The short rotation has allowed for accumulation of the inoculum in those fields, which appears to make a difference.

“There is a good opportunity for growers to be proactive in monitoring blackleg and assessing the risk,” says Peng. “During harvest, at the end of the day, pull about 100 stubble stem samples from across the field, clip the stubble sample at the root section and look at the overall blackleg incidence. This is a good way to project the risk for the next season. If growers are seeing an increasing trend of the disease then it is a sign they should make some changes to their management. If the disease incidence is staying below five per cent, then it is probably still a good sign of a healthy crop.”

Peng has also been conducting research over the past four years on fungicides for control of blackleg. Based on the results to date, a widespread use of fungicides, even at the early crop stage, would not be useful in terms of yield benefit. “In most cases our resistant varieties are still standing pretty good and the severe damage seems to happen in fairly isolated cases. Based on the level of damage we are seeing on a regional basis, the overall disease severity is too low for fungicides to be really beneficial in terms of yield improvement. Although there clearly is a reduction in disease severity, the

impact on the seed yield is so low that there isn’t a lot of benefit from the investment into a fungicide application.”

Another consideration is that most of the registered fungicides are very similar in modes of action, being the strobilurin type, which are easy for a pathogen to develop resistance to. One older alternative, Tilt, is no longer very effective. “Therefore, if growers routinely use fungicides as a preventative measure or for any other physiological benefit, by the time we really need fungicides we may not have highly effective products due to potential fungicide resistance in the pathogen population,” says Peng. “Therefore, we discourage widespread use of fungicides and they should be considered as the absolute last resort to control the disease. In situations where there are widespread problems with a virulent pathogen race and conditions are expected to get bad for the season, then putting on a fungicide treatment early in the season would be warranted, otherwise it is generally not necessary.”

As the information from this five-year project currently underway is collected and analyzed, researchers expect to have a better understanding of the changes in the pathogen population and the impacts from different farm operations and practices. By the end of the project, researchers hope to be able to demonstrate some of the good practices that may help reduce the risk of blackleg resistance across the Prairies.

For more on crop disease management, visit www.topcropmanager.com.

MAXIMUM TILLAGE AND MINIMUM PASSES!

Now you can achieve both with the new RUBIN 12. The heavy frame and massive 29-inch serrated discs aggressively and intensively mix of all types of residue evenly throughout the soil, to leave the ideal amount on the surface.

Manage heavy stubble or tear up hayland and pasture in just one rapid pass with the new LEMKEN RUBIN 12 and experience Blue Performance!

The new LEMKEN RUBIN 12 is the only compact-disc with:

■ Symmetrically arranged 29” discs

■ Heavy-duty construction for primary tillage

■ A working depth of 4” to 8”

Manitoba

■ 100% hydraulic depth control

■ Multiple reconsolidation options

■ Superior residue incorporation

Agcon Equipment Winnipeg (855) 222-9216

Ag West Equipment Ltd. Portage la Prairie (204) 857-5130 Neepawa (204) 476-5378

Avonlea Farm Sales Domain (204) 736-2893

Greenland Equipment Ltd. Carman (204) 745-2054

Nykolaishen Farm Equipment Swan River (204) 734-3466

Reit-Syd Equipment Ltd. Dauphin (204) 638-6443 (877) 638-9610

Saskatchewan