TOP CROP MANAGER

NEW LABELLING O N ITS WAY

Another tool to fight blackleg in canola PG. 10

ANCIENT VERSUS MODERN WHEAT

Have wheat gluten proteins changed? PG. 15

PRE-HARVEST

GLYPHOSATE ON OATS

Following label directions is key PG. 24

Another tool to fight blackleg in canola PG. 10

Have wheat gluten proteins changed? PG. 15

PRE-HARVEST

Following label directions is key PG. 24

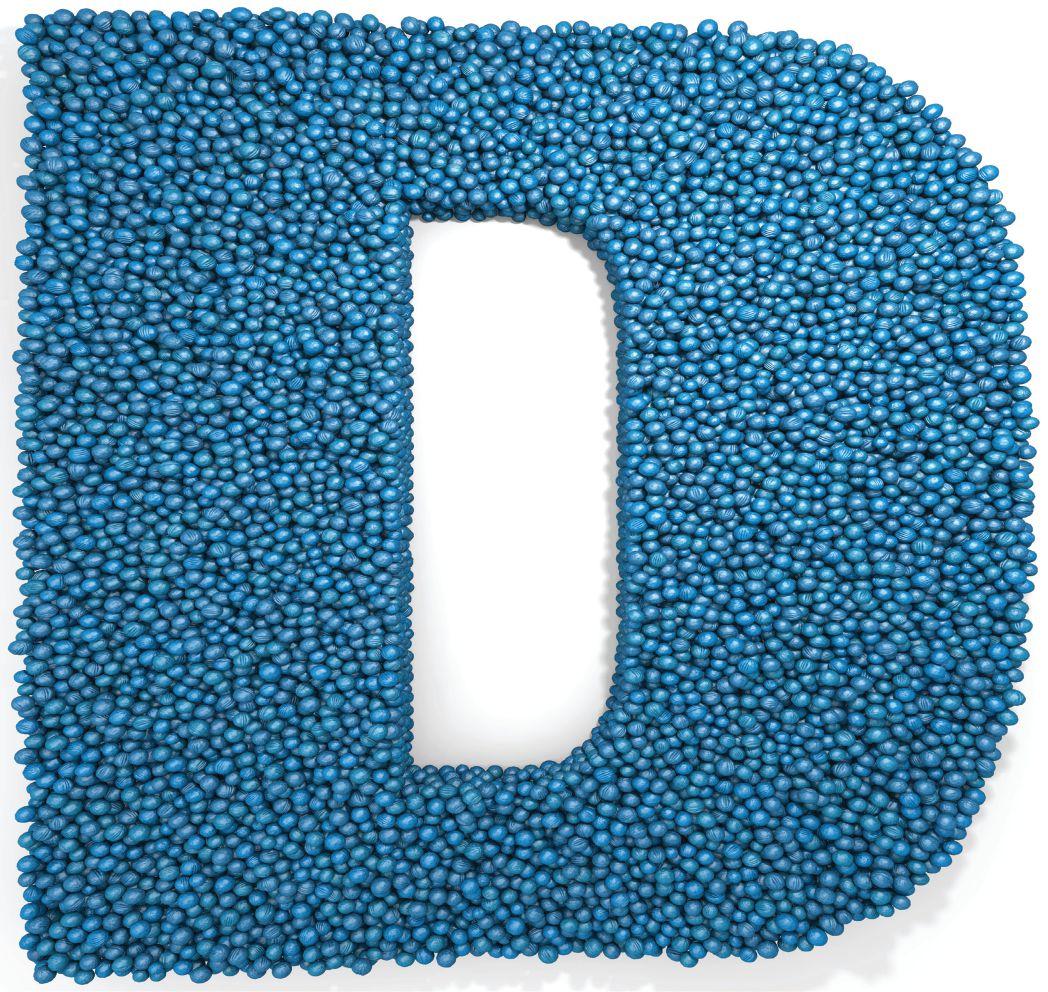

Through our patented Fusion® technology, only MicroEssentials® combines all three dimensions of smarter crop nutrition: uniform nutrient distribution, increased nutrient uptake and season-long sulphur availability. When you look closer at other fertilizers, you’ll see they fall a little flat. Ask for MicroEssentials by name, and trust the only one with over 12 years of proven results.

New cultivar labelling system will help canola growers.

By Carolyn King

By Carolyn King

| Pre-harvest glyphosate on milling oats

Glyphosate doesn’t appear to have adverse effects on quality.

By Donna Fleury

Ross H. McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag.

There’s

Readers

BRANDI COWEN | EDITOR

It’s been almost 15 years since the Human Genome Project was declared complete. The publicly funded research project was established in 1990, kicking off an international effort to identify and map all of the DNA sequences in the human genome by 2005. In the days after the announcement hit the headlines in April 2003, there were some long faces in my high school biology class. For a generation of budding scientists, the news represented a closing door – the end of a high profile, international effort they would never get to be a part of. (In the minds of cynical teenagers who “understood how the world worked,” that 15-year timeline was definitely going to stretch another 10 years or more, owing to government involvement in the project.)

But, as numerous headlines in recent years have proven, science never stops presenting new mysteries for inquiring minds to puzzle out. (And, thanks to social media, I can report a handful of my former classmates are building careers doing exactly that.)

In April, a global team of researchers finished sequencing the barley genome. “It makes it much easier for researchers working with barley to be focused on attainable objectives, ranging from new variety development through breeding to mechanistic studies of genes,” said Timothy Close, a professor of genetics at the University of California – Riverside, in a press release. He noted the team’s findings might also prove useful for researchers studying other cereal crops, including rice, wheat, rye, maize, millet, sorghum and oats.

That news came a little more than a year after the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium announced it had unraveled the mysteries of roughly 90 per cent of the bread wheat genome. The research was co-led by Curtis Pozniak, a plant scientist with the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre, and relied on advanced software, computer programming and bioinformatics tools to map the genome. In a press release issued at the time, Pozniak noted the discovery would “provide wheat researchers with an exciting new resource to identify the most influential genes for wheat adaptation, stress response, pest resistance and improved yield.” The full genome, which is reportedly five times the size of the human genome, could be complete by early 2018.

Other crop genomes that have been sequenced in recent years include canola, soybean, common bean, sunflower and more than 90 lines of chickpeas.

Many of these projects have involved international efforts, with research teams from several countries pooling resources to address shared problems. That’s certainly the case with the clubroot genome sequencing project, led by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Hossein Borhan in collaboration with peers in England and Poland. (Watch for more on this in a future issue of Top Crop Manager). But the important work of solving shared problems isn’t just conducted in the lab. There’s a role for farmers too – a fact proven by the success of the University of Manitoba’s Participatory Plant Breeding Program, which invites farmers to collaborate with plant scientists and breeders in the development of new crop varieties (see page 32).

I encourage you to keep this spirit of collaboration in mind as you gear up for another busy winter of meetings, conferences and trade shows. What problems did you encounter this growing season and how might you – and your fellow farmers – benefit by working together to solve them?

I look forward to hearing your ideas when we cross paths at those meetings, conferences and trade shows in the months ahead.

CIRCULATION email: rthava@annexbizmedia.com Tel: 416.442.5600 ext 3555 Fax: 416.510.5170

Mail: 80 Valleybrook Drive, Toronto, ON M3B 2S9

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues Feb, Mar, Mid-Mar, Apr, June, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East – 7 issues Feb, Mar, Apr, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax Potatoes in Canada – 1 issue Spring – 1 Year $16.50 Cdn. plus tax All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbizmedia.com • Tel: 800 668 2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be

I will approach harvest with flexibility and confidence, knowing that my yield potential is protected.

Take advantage of InVigor® patented Pod Shatter Reduction hybrids. InVigor L140P, early maturing InVigor L233P and NEW InVigor L255PC with the added benefit of clubroot resistance.*

Advanced technologies harvest new sources of FHB resistance from old-fashioned cultivars.

by Carolyn King

The record-high levels of Fusarium head blight (FHB) on the Prairies in 2014 and 2016 underline how crucial it is to have more wheat varieties with improved resistance to this major disease. Breeding for FHB resistance is notoriously difficult, in part because many different genes are involved. So researchers are applying diverse approaches to obtain new resistance genes. Some researchers in Saskatchewan are using advanced technologies to tap into the variability in traditional wheat varieties that were grown and selected by farmers over many generations.

The research involves a technique called eco-TILLING. The name comes from TILLING, or Targeted Induced Local Lesions IN Genomes. TILLING relies on chemical methods to induce mutations in a plant population, then uses various advanced technologies to find and use desirable gene variants in the mutated population. Eco-TILLING relies on naturally-occurring mutations, not induced mutations, but it uses the same advanced technologies to find and use helpful natural gene variants.

“We have a collection of about 1,000 wheat landraces and varieties from all over the world. Landraces are varieties that were often grown many years ago by farmers. They may not be great in many characteristics, but they might have a lot of hidden variability that we can find and use. Eco-TILLING is finding that variability and using it,” explains Patricia Vrinten, a researcher with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) in Saskatoon who is leading this study.

Instead of looking for active FHB resistance genes, Vrinten and her team are looking for inactive variants of FHB susceptibility genes. An inactive susceptibility gene causes a plant to have reduced susceptibility, which means the plant will have better resistance – at least in some plant species.

But in wheat, having just one inactive susceptibility gene isn’t

ABOVE: Researchers in Saskatchewan are looking at wheat lines from all over the world to find inactive variants of genes for susceptibility to Fusarium head blight.

RANCONA® PINNACLE combines two powerful fungicides that provide both contact and systemic activity, with RANCONA micro-dispersion technology for superior adhesion and coverage. And when more active ingredient ends up on your seed and not your equipment, you’ll see improved seed emergence, healthier seedlings, and higher yields. To learn more, talk to your Arysta LifeScience representative or visit rancona.com.

enough to create a plant with better FHB resistance. That’s because bread wheat has what’s called a hexaploid genome. It contains three complete genomes, called the A, B and D genomes, and each gene has three copies, one in each genome.

“So if we have a susceptibility gene but only one copy is inactive, it won’t give us an inactive susceptibility phenotype. That is, if we grow the wheat plant in the field, we wouldn’t be able to see that it has this inactive susceptibility gene because the other two genes that are causing more susceptibility are still there. So the inactive susceptibility is hidden until we find it in all three genes,” Vrinten says.

“But the probability of identifying a wheat line with inactive variants in all three genes by chance is extremely low, so we are unlikely to identify this source

of resistance by screening wheat lines for FHB resistance,” she adds. “Therefore we have to find lines with inactive variants in individual genes. Then we cross them using traditional crossing methods to combine all three genes in one plant and bring this hidden source of resistance into view.”

Vrinten’s group begins the process by identifying genes that could possibly increase susceptibility to FHB through various technical methods, such as gene expression studies followed by gene silencing methods, or through reviews of the literature.

“Some genes that cause an increase in susceptibility have been identified in barley or in Arabidopsis [a cousin of canola] or may even have been identified in wheat by us or our collaborators,” she

notes. Plants like barley and Arabidopsis are easier to use for this type of work because they are diploids – they have only a single genome – so they need only one copy of a particular inactive susceptibility gene for their phenotypes to have increased FHB resistance.

Once Vrinten’s group identifies possible susceptibility genes in these crops, they can use the eco-TILLING approach to look for inactive variants of those same genes in their collection of wheat landraces and varieties. “Once we know what the gene is, we use PCR [polymerase chain reaction] and sequencing facilities to look for these variants,” she says, “NRC has very excellent facilities for sequencing and bioinformatics that help us a lot with this part of the work.”

These technologies to find the variants involve developing molecular markers. The resulting markers also allow the researchers to more efficiently produce plants containing combinations of one, two or three copies of the gene variant of interest.

Then they look at the phenotypes of these combinations to evaluate their resistance to FHB. Evaluating FHB resistance requires that the plants be grown to maturity, which takes time –especially since some of the landraces are very slow maturing.

Vrinten and her group have developed methods to speed up that testing. “Through a combination of tissue culture methods and plant growth conditions, we have managed to get the generation time down considerably so that in the growth chamber we can go through a generation in as little as two to two and a half months.”

Although it’s much more work to deal with three copies of a gene instead of just one, wheat’s hexaploid genome also allows Vrinten’s team to make more nuanced changes than could be made in a diploid plant like barley. For instance, let’s say a particular susceptibility gene is inactive in barley, causing increased FHB resistance. Because that gene is inactive, it also causes a problem for the barley plant; maybe the plant is a little too short or it doesn’t flower properly. But in wheat, perhaps if two copies of this gene are inactive and one is active, then that might provide additional FHB resistance while overriding the associated problem.

“So in wheat you are actually getting a range of effects instead of the positive/negative effect that you get in diploid crops,” Vrinten explains.

Another important advantage to their approach is that the markers they develop will also enable wheat breeders to more easily move the desired gene variants into elite wheat lines.

A further benefit of this research is that the NRC has developed significant expertise in eco-TILLING, which can now be used for research to advance other important crop traits.

Vrinten and her team have already looked at a large number of candidate genes. “We have two that we already feel are very good; the parents are quite susceptible but when all three genes are combined, the line is quite resistant. We have a couple that we have already eliminated. And most of them we want to get more data on, or in some cases we might be missing one gene that we still want to combine.”

As part of their work, they have been conducting growth cabinet testing to assess the FHB resistance levels.

This research is ongoing. Vrinten notes, “We will be looking at additional genes as the literature evolves and as our collaborators come up with more information [on possible candidate genes].”

Vrinten and her group are collaborating on this research with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre, as well as many other people at the NRC. The NRC is the main funder for the project, and Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund is supporting the work on rapid germplasm development and rapid testing.

For more on plant breeding, visit topcropmanager.com.

KNOW. GROW.

A new cultivar labelling system provides another tool to help canola growers fight this disease.

by Carolyn King

Blackleg levels on the Prairies have been going up, but research information on blackleg races and cultivar resistance, plus a new cultivar labelling system and a new diagnostic test, can help bring those disease levels back down.

Blackleg is caused by two fungal pathogens. Leptosphaeria maculans, the main concern, is highly virulent; Leptosphaeria biglobosa is weakly virulent. The disease starts with spores infecting canola cotyledons (the first leaves to appear from a germinating seed). The infection develops and spreads, eventually causing cankers at the base of the stem. Blackleg can result in serious yield loss in susceptible varieties.

On the Prairies, the disease was first detected in the mid-1970s. It became a very serious concern in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Then resistant varieties were introduced, which greatly decreased disease levels. The levels remained low from about 2000 to about 2010, but have been creeping up ever since.

Agronomy specialist Justine Cornelsen, the blackleg lead for the Canola Council of Canada (CCC), emphasizes that blackleg is still at fairly low levels in most of the Prairies. “Currently, the average blackleg incidence – the number of plants in a field that are infected – is around 15 per cent on the Prairies, with the 10year average being under 10 per cent for the three provinces. And for blackleg severity, the averages are usually around one [on a scale where zero is no disease and five is dead from disease]. Only the odd producer or the odd field has struggles with this disease.”

Two main factors are likely causing the recent rise in blackleg. “We are seeing tightened rotations with canola every second year. But for blackleg management, we need about a four-year rotation to let the stubble break down and get rid of the fungus,” Cornelsen says.

“Another factor is that the pathogen is overcoming the resistance available in canola varieties. We have the same resistance package in a lot of our varieties, and because we have used that resistance package over and over again, the pathogen has slowly altered to overcome that resistance.”

Two types of blackleg resistance are used in canola varieties. One is called qualitative or major gene resistance. The other is called non-race-specific, quantitative, or minor gene resistance. The resistance breakdown on the Prairies is associated with major gene resistance.

“Major gene resistance can be quite effective if used properly because it stops the infection right at the spot of entrance,”

ABOVE: A cross-section of the base of a blackleg-infected canola stem shows blackened tissue from the infection.

explains Gary Peng, a research scientist with Agriculture and AgriFood Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon. “In this type of resistance, the blackleg pathogen-host interaction seems to be a very classical example of a gene-for-gene interaction. That means for a major resistance gene to work, the corresponding avirulent gene also needs to be at high levels in the pathogen population.” For instance, the major resistance gene Rlm3 is only effective against the pathogen carrying the avirulence gene Avrlm3 (abbreviated to Av3).

Blackleg race dynamics

“About 14 major resistance genes have been identified. To use them

effectively, we need to know which races are in the pathogen population,” says Peng, who is leading a project to monitor Prairie blackleg races.

It is a continuation of studies in 2007, led by Randy Kutcher who is now at the University of Saskatchewan, and in 20102011, led by Dilantha Fernando from the University of Manitoba.

Peng’s project runs from 2012 to 2017 and is funded by Alberta Canola, SaskCanola, Manitoba Canola Growers and the Western Grains Research Foundation. He has recently been granted funding for five more years of monitoring starting in 2017.

His current project uses two methods of collecting race data across the Prairies. One method is to take samples randomly from commercial canola fields. The other method involves collecting samples from Westar trap plots; this canola cultivar doesn’t carry any major resistance genes, so the race data are less likely to be skewed by the cultivar’s resistance. Peng is finding the two methods produce similar results, so he will likely just use one of the methods in the future.

In 2015, Peng and his research team also monitored blackleg races at 10 co-op trial sites where canola varieties are tested for blackleg resistance. He explains that race information for those sites could be helpful in analyzing varietal resistance performance. Also, the co-op sites are very useful for tracking race trends because their locations and field sizes are more stable than the trap plot sites. The team will revisit the co-op sites, tentatively in 2018, to see how the races have changed since 2015.

To determine which avirulent races are present in the samples, Peng’s team tests the fungal isolates against a set of differential Brassica lines, some of which were developed by his colleague Hossein Borhan. The lines carry different resistance genes; for example, if the differential line has Rlm1 and has a resistant reaction to an isolate, then that isolate may carry Av1

The project’s results indicate the Prairie blackleg population is very diverse. Up to 90 races have been identified.

One clear trend over time is that Av3 has decreased significantly. Peng says, “Av3 was in about 40 per cent of the pathogen population in 2007. Now Av3 is very difficult to detect across the Prairies.”

He explains, “When the pathogen

population changes, often the driver is the R gene we use in our varieties. In working with Dilantha Fernando’s lab at the University of Manitoba and in our own work, we found that most commercial canola varieties or breeding lines we looked at carried Rlm1 or Rlm3 or both. That is probably why the corresponding avirulent genes have become so low in the pathogen population.” For instance, Rlm3 was first deployed in the early 1990s. Over time, through ongoing selection pressure on the pathogen, Av3 gradually changed to

a virulent type.

“Another trend is that Av7 has been increasing over the last five or six years, and it is now at a high level across Western Canada,” Peng says. “Av6, Av4 and Av2 are at moderate to high frequencies.”

Beyond major gene resistance

So, the major resistance genes currently in most canola varieties are no longer very effective, and yet we do not have a severe blackleg epidemic on the Prairies. “We see blackleg everywhere, but severely damaged

Too much early-season nitrogen (N) encourages lodging, depletes soil moisture and leaves less N for seed production. ESN technology controls N release, reducing N loss and increasing N efficiency. Additionally, it significantly reduces N loss to the environment.

ESN technology and increased yield

When compared with similar N treatments of urea or UAN, using 50-75% of N with ESN technology has shown an average of 8-10% increase in canola yield. This data is derived from a number of independent research studies conducted at various locations in Western Canada.

Unmatched seed safety

Applied at rates up to three times higher than conventional N fertilizers, ESN won’t harm growing seedlings (following safe rate guidelines and recommended percentages of ESN).

Wider application window

ESN provides a wider application window in both the spring and the fall, allowing you to apply fertilizer on your schedule.

Convenient to use and apply

ESN is compatible with no-till operations and is easy to blend. It will not set-up in storage and therefore has a longer shelf life.

Environmentally responsible ESN significantly reduces N loss, providing substantial benefits to the environment.

Minimize N Loss. Maximize Yield. Learn more at SmartNitrogen.com

fields are still quite isolated cases,” Peng says. “The disease is a little more noticeable in southern and southeastern Manitoba. In some other areas, high blackleg levels are more related to back-to-backto-back canola rotations. And some severely damaged fields are related to hail damage or more severe root rot and root maggot damage and sometimes flea beetle damage on the cotyledons.”

Those facts suggest several things to Peng. One is that, in addition to major gene resistance, many cultivars have non-racespecific resistance. Two, this non-specific resistance seems to have been the backbone of blackleg resistance on the Prairies for the last few years. And three, this non-specific resistance may not be as effective when the plants have some physical damage or when inoculum levels are really high due to continuous canola.

In another project, Peng is taking a closer look at non-racespecific resistance. This three-year project, now in its second year, is supported through the grower-funded Canola Agronomic Research Program.

One objective of the project is to characterize the non-racespecific resistance in Prairie cultivars. “We are mostly looking at commercial varieties that carry the Rlm1 and Rlm3 genes but in different backgrounds because we are not sure if non-racespecific resistance is caused by a multi-gene background or by an interaction between the two major resistance genes that may not be a gene-for-gene interaction but still has some effect on the pathogen,” Peng explains.

Another objective is to examine the effects of environmental stress, especially high temperature stress, on the level of nonspecific resistance in different canola varieties. Peng notes, “In Australia they think stress conditions in the later growing stages, like hot and dry conditions, really exacerbate infection development. In those conditions, they thought their quantitative resistance alone would be insufficient.”

A key part of the project is to examine the molecular mechanisms of non-race-specific resistance, to see if they differ

“If we talk about what we’re doing, people will understand how their food is grown and why we grow it the way we do.”

between varieties and how the mechanisms compare to major gene resistance.

Peng and his team are finding non-race-specific resistance in many of the resistant varieties appears to slow the pathogen’s spread. “After it infects the cotyledon tissue, the pathogen seems to move much more slowly than in a susceptible variety. Often it may not reach the stem through the infected cotyledon petioles before the whole cotyledon drops off,” he says.

Peng thinks this mechanism of resistance could be quite important on the Prairies. “Cotyledon infection is important in Western Canada mainly because we have a much shorter growing season, 90 to 100 days to maturity, versus other jurisdictions where they have 180 to 300 days for a canola or rapeseed crop. So in Western Canada, if the infection doesn’t get going on the cotyledons, then it is very difficult for the infection to develop into the stem from the true leaves later on [because there is not enough time].”

A recently approved seed labelling system can help growers with blackleg problems when selecting their canola varieties.

“In Canada, we have talked about a labelling system [for resistance genes] for five or six years. But recently we started to see a little more push. Blackleg levels are starting to rise, which is moving the disease to the top of producers’ minds. Also, we’ve got new yield data that shows the actual loss associated with the disease, which helps show how much blackleg is actually hurting Canadian producers. And blackleg is a trade concern. All those

Table 1: New Canadian blackleg resistance gene labelling system for canola varieties

Resistance groups for major blackleg resistance genes Blackleg race

Resistance A Rlm1 or LepR3

Resistance B Rlm2

Resistance C Rlm3

Resistance D LepR1

Resistance E1 Rlm4

Resistance E2 Rlm7

Resistance F Rlm9

Resistance G RlmS

Resistance H LepR2 X Unknown

Adopted in the WCC/RCC Procedures Manual in February 2017.

factors are bringing awareness to the whole canola value chain in Canada that we need to minimize blackleg in our production areas,” Cornelsen explains.

“So our blackleg steering group, which is comprised of researchers, seed companies, growers, [provincial extension staff and others], helped to form a labelling system based on what

we currently know about the Canadian situation. We based our system on systems used elsewhere in the world; it’s very similar to the Australian system. We produced several different models and they were voted on at the Western Canadian Canola/Rapeseed Recommending Committee [WCC/RRC] pathology meeting [in February 2017].”

The resistance genes are placed in groups identified by a letter (see Table 1). “Right now we have roughly 10 major gene resistance groups based on the actual resistance genes we found in varieties/ breeding lines a few years ago. A few of the resistance groups aren’t in Canadian varieties yet, but they are used in other breeding programs and we hope to have them in our varieties eventually,” Cornelsen says.

In the new system, the variety’s resistance group is paired with its blackleg resistance rating of resistant (R), moderately resistant (MR), moderately susceptible (MS) or susceptible (S). Peng advises, “With the new labelling, the first category to look at is the overall performance rating based on field trials, that R, MR, MS or S rating, and then look at the type of resistance gene involved.”

Resistance gene labelling is voluntary for the seed companies. “Several seed companies are quite interested in resistance gene labelling and hope to have their labels out within a year,” Cornelsen says. At least one company, Dekalb, is using this new labelling system in its 2018 seed guide.

A newly developed diagnostic test will make the labelling system even more helpful.

“Hossein Borhan’s group recently developed a rapid test for blackleg races. They have sent out the markers and a protocol to diagnostic labs that want to evaluate it and see if they will offer it in their labs. Hopefully by next year they’ll be able to provide the service to producers,” Cornelsen says. “So producers will be able to collect stubble from their fields, send it to a lab and find out which blackleg races are in their field. Of course, the pathogen is very diverse so producers will have several races within a field. But hopefully they will be able to match a resistant canola variety to the top race in their field.”

“The canola varieties we have now are fantastic and work really well,” Cornelsen notes. “The resistance gene labelling is an added dimension, enabling growers to change up the genetics that they are deploying. It will really help to tighten up resistance stewardship for the long run.”

“However, this labelling system will not solve all the problems for those few producers who have a tighter rotation and are struggling with managing the disease,” she adds. “Producers still really need to scout for the disease and know what they are looking for; blackleg can be easily mistaken for other diseases. And they need to extend the rotation. Any extension gives another year of breakdown to get rid of some of that stubble.”

According to Peng, another thing that could help keep a lid on blackleg levels is improved monitoring of the pathogen’s races. “Right now we can only do big picture monitoring for the Prairies. Although we’re developing more efficient techniques, at this point we can only test a maximum of about 600 isolates over a year.”

Better race information would help in deploying major gene resistance more effectively. “For example, right now if Rlm7 is incorporated into our varieties, it would quickly suppress the disease level quite effectively,” Peng says. “And if we can stabilize or reduce blackleg levels and reduce seed contamination and dockage, then that might be a very positive image to our export customers concerned about the introduction of the disease.”

Continued work on non-specific resistance is also important. “The major R genes will be eroded eventually, or even fairly quickly, because of the selection pressure on the pathogen population. From our monitoring data, we know that for pretty much every known major resistance gene, we have at least one race already in Western Canada that can overcome it right away. So it is just a matter of time before any of those major genes is eroded after extensive use,” Peng explains. “It will be important to keep our good non-specific resistance materials in our breeding efforts, while introducing some new major genes into this background. That will make the resistance in our varieties more robust.”

by Carolyn King

Some diet books have claimed modern wheat breeding has produced changes in wheat varieties that are causing harmful effects to human health. But University of Saskatchewan researchers have already determined that some key nutritional characteristics in wheat have actually changed very little from the varieties grown 150 years ago to today’s varieties. Now these researchers are teaming up with a University of Alberta colleague to delve into another important aspect of this issue: Have wheat gluten proteins changed over time?

“We are trying to see if there is any science behind the claims,” explains Ravindra Chibbar, a professor at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) who is leading this research.

His studies so far involve nutritional analyses of grain samples from 37 hard red spring wheat varieties dating from the 1860s through 2007. These varieties are part of an ongoing field experiment to measure the rate of improvement in Prairie wheat varieties over time. The experiment started in 1989 and involves replicated trials in central Saskatchewan. U of S professor Pierre Hucl leads this experiment, and he has selected representative varieties for each decade since 1860. The oldest of the 37 varieties is Red Fife, a wellknown Canadian heritage wheat.

In 2015, Hucl and Chibbar published some results from their analyses of the agronomic, processing and nutritional characteristics of these varieties. They found that traits like grain yield, kernel weight and several milling and baking quality characteristics improved from the heritage wheats to the modern varieties, but the total protein concentrations changed very little.

Since 2015, Chibbar and his research team have been conducting detailed studies of the starch and mineral characteristics of the grain from those same 37 varieties. They have completed the lab work and are now analyzing the data and preparing a manuscript for a peerreviewed scientific publication.

They examined starch granule size, structure and digestibility because these factors relate to some of the negative claims made about wheat consumption and weight gain. Chibbar explains that starch digestibility is a very important factor in weight gain and obesity. “The calories stored in starch are released when starch is digested in the gastrointestinal tract. In calorie-deficient regions of the world, grain starch and protein need to be more digestible so people can extract all the benefits from the food to meet their daily requirements. In calorie-excess regions, lower starch digestibility [would help overweight and obese people to manage their weight].”

He adds that starch digestibility is also the concept behind the glycemic index, where lower digestibility means a lower glycemic index.

Chibbar notes that each wheat variety has its own specific starch characteristics, so the data vary from variety to variety. However, based on his preliminary data analysis, the trend lines for these characteristics show little change over time.

The trend line for total starch concentration shows a slight increase from 57.8 to 61.5 per cent over the past 150 years. He says, “This increase was expected because starch increases when we increase the grain yield and we have made significant grain yield increases since 1860.”

To assess changes in starch digestibility, Chibbar’s group determined the concentrations of the two major components of starch: amylose and amylopectin. “We are still analyzing the data, but we see a slight increase in the amylose concentration, from 25.5 to 27.5 per cent. This is a good thing from our viewpoint because amylose, a long glucan polymer, is hard to digest; therefore an

increase in amylose concentration can reduce starch digestibility. In contrast, some diet books have said that amylopectin, which is easy to digest, has significantly increased in modern wheat varieties. But we have not found that in the hard red spring wheat varieties in our study.”

Chibbar’s group determined the concentrations of calcium, iron, zinc, selenium and manganese in the grain samples using the VESPERS (Very Sensitive Elemental and Structural Probe Employing Radiation from Synchrotron)

at the Canadian Light Source synchrotron at the U of S. The mineral concentrations differ from one variety to the next, but the only statistically significant trend from the heritage to the modern varieties is a slight decrease in the calcium concentration.

Chibbar is now analyzing the data to see if there is a dilution effect on the mineral concentrations. “This theory of dilution is that, because starch has increased in modern wheat varieties due to grain yield increases, the minerals become diluted. On the other hand, a study in the United States comparing

soft wheats with hard wheats found that this dilution theory only held true in soft wheats because soft wheats have more starch and less protein than hard wheats.”

The iron concentration has a slight decreasing trend that is not statistically significant. As a side note, Chibbar points out that his study is analyzing the meal from the grain samples, whereas all white flour sold in Canada must be fortified with certain nutrients, including iron. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s website states: “The mandatory enrichment of white flour with B vitamins, iron and folic acid is a cornerstone of Canada’s fortification program aimed at helping to prevent nutrient deficiencies and maintain or improve the nutritional quality of the food supply.” Under these requirements, Canadian white flour must contain 4.4 milligrams of iron per 100 grams of flour.

When water is added to wheat flour, certain proteins interact with each other to form gluten. Gluten gives wheat dough its elasticity and plasticity, which enhance the quality of baked goods. Also, gluten extracted from wheat, referred to as “vital gluten,” is added to other food products to improve their characteristics.

Gluten is of particular interest to Chibbar because it can have health impacts in some individuals. For people who are genetically predisposed to celiac disease, gluten consumption triggers an immune reaction in the small intestine. As well, wheat consumption in some people is associated with non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

FARM MANAGEMENT. DATA MANAGEMENT. VARIABLE RATE TECHNOLOGY. SUPPORT.

Put your farm to work with Echelon, today’s highest-performing precision agriculture solution that’s designed to identify and form your ultimate farm strategy. It’s the simple way to accomplish more in efficiency, productivity and profitability.

The results are clear with average yield increases* of: 10.8% in canola / 5.9% in wheat / 6.4% in barley Learn more at echelonag.ca. Available exclusively from CPS. BRING

Some research studies have found an increased occurrence of celiac disease in the last half of the 20th century. The reasons for this increase are unknown. Various possible contributing factors have been suggested, such as increasing amounts of vital gluten in our diets, increased per capita wheat consumption, changes in wheat genetics and changes in agronomic practices, such as nitrogen fertilizer practices.

Some diet books have suggested the increase in celiac disease is due to an increase in gluten in wheat varieties in recent decades. But Chibbar’s findings show the total protein concentration in the study’s hard red spring wheats has increased by only about one per cent in 100 years.

However, he wondered, “Have there been changes in the types of wheat proteins?” To answer this question, Chibbar

and Hucl are collaborating with Dr. Leo Dieleman, a gastroenterologist at the University of Alberta. Funding for this new project is from Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund, the Western Grains Research Foundation and the Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission.

The first stage in this project will be to see how the severity of celiac disease relates to the many different kinds of gluten protein fragments (peptides) in wheat. The researchers will be determining which specific peptides evoke a celiac-related response using serum samples from celiac patients.

The University of Alberta’s Centre of Excellence for Gastrointestinal Inflammation and Immunity Research collects serum samples from its celiac patients. Once Dieleman and Chibbar have the necessary ethics approvals in place, they will have access to samples from this serum collection. Dieleman’s research team will identify five or six patients for each of three categories of celiac disease: severe, moderate or mild. Then they’ll provide those patients’ serum samples to Chibbar for testing with the wheat gluten peptides.

After Chibbar’s team has identified the celiac-disease-causing peptides, the next step will be to determine if the amounts of these peptides have changed from the heritage to modern varieties in Hucl’s set of 37 varieties. If it turns out that these peptides have not increased, then that would help refute the claim that changes in modern wheat varieties are somehow responsible for the increasing incidence of celiac disease. On the other hand, if these peptides have increased, then that trend could potentially be reversed through targeted breeding, and that might be very helpful in the prevention of celiac disease.

In another component of the project, Chibbar’s group will determine the amount of these disease-causing peptides in current western Canadian wheat varieties. They will be comparing 100 varieties that include all Canadian market classes of wheat.

In addition, the project is looking even further into the past than the 1860s. The researchers will assess the amount of the celiac-disease-causing peptides in five varieties of three ancient wheats – emmer, spelt and einkorn – and in canaryseed. Canaryseed does not cause an immune response in celiac patients, so the researchers are using it as a check for comparison.

Chibbar and his colleagues have also applied for additional funding to identify the wheat genes that play a part in the occurrence of the celiac-disease-causing peptides and then use genome editing technologies to reduce the amount of these gluten fragments in wheat.

The long-term goal of this research is to develop wheat varieties that have minimal or no celiac-disease-causing proteins but retain all the great end-use properties.

Chibbar believes nutrition and health objectives will play a part in wheat breeding

objectives. “The upcoming trend is to reshape agriculture for health and nutrition. This concept was put forward in 2012 by the International Food Policy Research Institute. And with evolving technologies – such as being able to analyze minerals in very small quantities like we did with the Canadian Light Source, and techniques to look at proteins as we will be using in our new project – and with evolving knowledge in genomics and other areas, I think there is good potential that those nutritional and health objectives can be achieved.”

YOU INVEST IN A BIN TO PROTECT YOUR PRODUCT FROM THE ELEMENTS, BUT WHAT IS GUARDING YOUR GRAIN FROM SPOILAGE ON THE INSIDE?

Grain Guard has an established catalog of aeration and conditioning equipment to assist you in managing your grain storage. With more than 100,000 fans in operation Grain Guard remains the leader in aeration design.

STATE OF HERBICIDE RESISTANCE IN CANADA

Hugh Beckie • Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada/University of Alberta

Sponsored by

HERBICIDE USE IN CANADA: RESULTS FROM TOP CROP MANAGER’S INAUGURAL SURVEY

Gerald Bramm • Bramm Research

Sponsored by

EVOLUTION OF RESISTANCE: AMARANTH SPECIES AND GROUP 14 HERBICIDES

Franck Dayan • Colorado State University

GLOBAL EFFORTS TO PREVENT HERBICIDE RESISTANCE

Mark Peterson • Herbicide Resistance Action Committee

Steve Shirtliffe • University of Saskatchewan CONTROLLING GLYPHOSATE-RESISTANT WEEDS: AN ONTARIO PERSPECTIVE

Peter Sikkema • University of Guelph - Ridgetown

HARVEST WEED SEED CONTROL IN THE CANADIAN CONTEXT

Breanne Tidemann • Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

MANAGING RESISTANCE WITH SPRAYER APPLICATION TECHNOLOGY

Tom Wolf • Agrimetrix Research & Training

Sponsored by NON-CHEMICAL WEED CONTROL METHODS

Somewhere in the pattern of what is considered predictable about farming – the yearly routine of planting, fertilizing, spraying and harvesting – the seed and traits industries continue to demand growers update their educations to meet constantly changing requirements.

With each new growing season, there are more canola, corn and soybean hybrids in the fields and on the horizon. These hybrids embody traits and innovations that are intended to provide greater protection, reduce a grower’s risk and add value to the bottom line.

The agriculture industry is constantly working, innovating and creating to ensure product demand can be met when farmers call for it. But the onus is on producers to make decisions to ensure the best results.

This kind of forward thinking reflects our philosophy at Top Crop Manager. With a wealth of new technologies emerging, we do our best to help you make smart decisions to prepare for the coming year, and we are happy to provide you with our 2017 Traits and Stewardship Guide for Western Canada.

Besides being a resource, the guide is an annual reflection of how the industry continues to change. Our goal is to ensure our readers are aware of research being done now that will potentially change the way they farm. By highlighting new technologies, we strive to help producers stay ahead of the curve and we’re proud to be able to give early adopters the information they need to plan ahead.

The information herein is intended to assist in making decisions going forward, but for a better idea of what will work for you, we recommend you talk with your seed dealer for more information.

BRANDI COWEN | EDITOR JANNEN BELBECK | ASSISTANT EDITOR

Genuity Roundup Ready Canola RT73

BrettYoung, Canterra Seeds, Dekalb, Nexera, Pioneer, Proven Seed, Red River, SeCan, Victory

TruFlex Canola MON 88302 Monsanto

InVigor HCN28

CPS, FCL, Cargill, Richardson, UFA, Independents through InterAg

Roundup Ready Original 40-3-2 Pioneer

Roundup Ready 2 Yield MON 89788

LibertyLink A2704 -12

Country Farm Seeds, Croplan, Dekalb, Elite, Dow Seeds, Maizex Seeds, NorthStar, Pioneer, Pride Seeds, Semences Prograin, SeCan, ProSeeds Yes

Country Farm, Croplan, Elite Seeds, Northstar Genetics, Pride Seeds, Pioneer Yes

Plenish high oleic soybeans Pioneer No

Enlist

DAS-68416-4+ MON 89788 Dow Seeds

Enlist E3 DAS-44406-6 Dow Seeds

Roundup Ready 2 Xtend MON 87708 + MON 89788

Croplan, Dekalb, Elite, Legends Seeds, Maizex Seeds, NorthStar Genetics, Pioneer, Pride Seeds, Pro Seeds, Semences Prograin, SeCan, Syngenta, Thunder Seeds Yes

Vistive Gold MON 89788 Monsanto

HT3 Monsanto

SDA Omega-3 soybeans Pending Monsanto

Soybean Cyst Nematode Resistance Pending Monsanto

Next-Generation Multiple Mode Herbicide Tolerance Pending Pioneer

Increased Oil & Improved Feed Efficiency Pending Pioneer

Balance GT Pending (FG72)

Balance GT/LL Pending (FG72 + A5547-127) TBD

Roundup Ready Corn 2 NK603

VT Double PRO RIB Complete MON 89034 + NK603

AgroSciences SmartStax

SmartStax Refuge Advanced

XTRA with Roundup Ready Corn

88017 + MON 89034 + TC1507 + DAS-59122-7

88017 + MON 89034 + TC1507 + DAS-59122-7

Croplan, Dekalb, Dow Seeds, Elite, Legend Seeds, Maizex Seeds, Northstar Genetics, Pickseed, Pioneer, Pride Seeds, Proven Seed, Thunder Seeds

Croplan, Dekalb, Elite, Legend Seeds, Maizex Seeds, Northstar Genetics, Pickseed, Pride Seeds, Proven Seed, Thunder Seeds

+ DAS-59122-7

Agrisure 3122 E-Z Refuge

PowerCore

Enlist SmartStax

+ Bt11 + TC1507

+ MIR604 + Bt11 + TC1507 +

+TC1507 + NK603 + DAS40278-9 + DAS59122-7

+ MON 88017 + MON 89034 + TC1507 + DAS-59122-7

& Glufosinatetolerant Corn Pending

Drought Tolerance II Corn Pending

Harvest quality of milling oats is very important, and growers sometimes utilize harvest aids such as pre-harvest glyphosate. A properly timed application can help growers control perennial weeds and improve crop harvestability, while meeting maximum residue limit (MRL) requirements. However, some buyers have placed restrictions on the use of pre-harvest glyphosate on oats they purchase.

BY Donna Fleury

Christian Willenborg, associate professor with the College of Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of Saskatchewan, initiated a small study in 2015 to collect some initial research data and find a way to lend science to the decision-making process. “We were surprised at the announcement that some milling quality oats would not be accepted if treated with glyphosate, and frankly, this didn’t sit well with me. But there was no science on this and so we immediately established a one-season ‘look-see’ trial in 2015 at two locations near Saskatoon to compare different harvest systems and their effects on quality of milling oats,” he says. “We compared two different oat cultivars: CDC Dancer, a medium maturity cultivar, and AC Pinnacle, a later maturing cultivar. The oats were managed using typical agronomy practices, including a seeding rate of 300 seeds per square metre (seeds/m2) targeting 250 plants per square metre (plants/m2) and fertilized for a target yield of 150 bushels per acre.”

The second factor was a comparison of three different harvest systems, including swathing at the optimum timing of 35 per cent moisture, direct combined (at approximately nine per cent seed moisture content alone and direct combined with a pre-harvest glyphosate application. The pre-harvest glyphosate was applied according to label requirements at 30 per cent seed moisture content using the recommended label rate. The project compared various harvest quality parameters, as well as functional quality characteristics and residue testing across the different treatments.

Through funding from the Prairie Oat Growers Association and the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund, the initial 2015 trial has been expanded into a fully funded, much larger three-year project that will involve several additional experiments.

“We gained some very good insights in the initial trial, but these very preliminary results will be compared again in this larger expanded trial over the next three years. Until we get the final results at the end of 2018, these early one-season informational highlights have to be considered very preliminary,” Willenborg says.

The 2015 preliminary results showed that, as expected, cultivar had an impact on all of the quality parameters, such as yield, plump kernels, 1,000 kernel weight and test weight. However, there was no cultivar by harvest system interaction – the effects of the harvest system were consistent regardless of which cultivar was planted.

“The harvest system did have an impact on several of the quality parameters, however the preliminary results did not show any negative effects of a pre-harvest glyphosate application,” Willenborg explains. “In terms of yield, swathing resulted in a 15 to 18 per cent yield reduction compared to direct harvest, however some of that reduction may be a function of our plot harvesting equipment, and this may be different with field-scale grower systems. The direct harvested plots, with and without a pre-harvest glyphosate treatment, had virtually

equal yield. Swathing produced the highest test weight, with direct harvest plus pre-harvest glyphosate equal to the swathing treatment; direct harvest with no glyphosate had a significant lower test weight.”

The swathing treatment also produced the highest percentage of thin kernels, with direct harvest and no glyphosate intermediate and the lowest percentage of thin kernels with direct harvest plus glyphosate treatment. On the other hand, the percentage of plump kernels was the same in both direct harvest treatments, but slightly lower for the swathing treatment. Overall, the pre-harvest glyphosate reduced the percentage of thin

kernels in the sample, which is a benefit for growers.

“For the initial and longer term project, we partnered with Dr. Nancy Ames at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada to compare the functional aspects of the oat cultivars under the different treatments,” Willenborg says. “Her preliminary functional test results were similar to the seed quality results, with no major impacts on functional quality among the treatments. For the glyphosate testing, we partnered with Dr. Sheryl Tittlemier at the Canadian Grain Commission to develop a glyphosate residue test for oat. Her initial test results from the 2015 treatments showed that the

direct harvest plus pre-harvest glyphosate treatment did have very small levels of residues at four [parts per million], which is well below the MRL threshold levels in North America. We will continue to use this test for the larger project.”

The expanded three-year study will include the same harvest treatments, with some additional trials assessing seeding rate and stand uniformity. Stand uniformity is related to the question of whether or not additional tillers in the stand may be a factor with potential glyphosate issues. The three harvest treatments will also be compared at a range of different moisture contents,

Continued on page 31

Fall-apply Valtera ™ or NEW Fierce ® and they’ll re - ignite with spring moisture. Each product is effective for 6-8 weeks after re-ignition, eliminating weeds before they ever have a chance to grow. Simple application through field sprayers removes the hassle of granular application saving time now and during seeding.

Ask

Valtera provides extended residual protection, safely eliminating the most troublesome broadleaf weeds in pulses, soybeans and spring wheat. Fierce provides elevated performance when applied before soybeans and spring wheat. The synergistic activity of Group 14 and 15 provides uncompromising elimination of broadleaf and grassy weeds.

As problems with Fusarium head blight (FHB) continue to increase on the Prairies, so does the need to deal with Fusarium-infested grain and screenings. Preliminary results from a Saskatchewan study are pointing to a possible way to extract value from these wastes while potentially reducing the risk of spreading the disease.

BY Carolyn King

FHB is a difficult to control fungal disease that affects cereal crops. It reduces crop yield and grade, but its most serious impact is the pathogen’s ability to produce mycotoxins that limit the grain’s use for food and livestock feed. Several Fusarium species can cause the disease; the most common one is Fusarium graminearum. Its mycotoxins include deoxynivalenol (DON), the most common mycotoxin associated with FHB.

“The traditional use for Fusarium-damaged grain is to clean it and then, if possible, blend it with uncontaminated grain for animal feed. Although the limits for Fusarium levels in feed are set, there is some nervousness within the livestock industry that if livestock are continually at that maximum level for years and years, there could be some long-term detrimental effects to animal health. So the livestock industry has been pushing for another disposal option to minimize the risk of damage to the animals,” explains Joy Agnew with the Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute (PAMI), who led this research.

“At present, if the mycotoxin content of the grain or the screenings is too high to be blended for feed, then usually the material is dumped in the bush, a slough, or a hole in a field. But there is a potential risk of spreading Fusarium with dumping.”

She notes the amount of Fusarium-damaged grain has increased substantially in the last few years, adding: “The Canadian Grain Commission [CGC] estimates that a third of all red spring wheat was downgraded due to Fusarium damage in 2014.” And Fusarium levels were even worse in 2016, with downgrading of nearly half of the red spring wheat samples in the CGC’s harvest sample program.

As a result, it is increasingly important to find alternatives to dumping and feed blending.

“A lot of research is being done on preventing Fusarium head blight, but not much is being done on how you can extract value from heavily damaged grain and screenings if your crop gets the disease,” Agnew says. Finding ways to add value to these infested materials would help producers deal with some of the economic impacts of FHB, such as extra fungicide costs, poorer yields, higher seed cleaning costs, lower prices for the grain and limited marketing opportunities.

So Agnew initiated a project to evaluate various disposal options to determine their potential for extracting value from the Fusarium-infested materials and for minimizing the spread of FHB. Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund, under the federal-provincial-territorial Growing Forward 2 program, funded the project. The CGC provided in-kind services.

Agnew and her research team reviewed the literature on seed cleaning options and surveyed Saskatchewan seed cleaners about current practices. They discovered none of the seed-cleaning technologies currently used in Saskatchewan are ideal for dealing with Fusarium-infested grain.

The survey found the most common way for the province’s seed cleaners to remove Fusarium-damaged kernels from grain was to use a gravity sorter as part of a mobile cleaning unit. “A gravity sorter separates seeds based on seed density, but research shows this technology misses some Fusarium-damaged kernels and discards a lot of healthy kernels. However, it’s a low-cost, fairly high capacity method. That is why it is so

I will wake the rooster and be the one who decides when it’s time to quit. I will succeed by working with whatever Mother Nature provides, adapting and innovating to reach my maximum potential. I will actively pursue perfection.

COMMON DISPOSAL OPTIONS FOR FUSARIUM-DAMAGED KERNELS

Clean and blend

Traditional use is to clean and blend with uncontaminated grain for animal feed.

Dumping

If toxin levels are too high, grain can be dumped in bush, slough or in a hole.

Gravity sorter

Seeds are separated based on density. It’s a low-cost, fairly high-capacity method.

Burning

The most common method of disposal. Grain can be burned in a grain-burning stove or can be pelleted and burned.

Composting

This is a pretty standard method of disposing of organic waste and it is easy to incorporate on to the farm.

Anaerobic digestion

Preliminary work in Europe indicated digestion might deactivate the spores, breaking them down in an oxygen-free environment.

Near-infrared transmittance (NIT)

Sends light through individual kernels and measures the response to determine the chemical characteristics of the kernels.

widely employed,” Agnew says.

More sophisticated technologies like optical sorters or nearinfrared transmittance (NIT) equipment were not common in Saskatchewan when Agnew’s group conducted the survey in 2016, but since then, she has heard of several more custom grain cleaners who are now offering these technologies.

Agnew explains that optical sorters evaluate individual seeds and eject the ones that do not fall within a predetermined colour spectrum. However, Fusarium-damaged kernels vary in colour from whitish to black or pink, which complicates and slows the sorting process – especially if the grain is highly infested.

NIT involves sending light through individual kernels and measuring the response to determine the chemical characteristics of the kernels, such as protein content, starch content and hardness. Research shows this technology can remove Fusarium-damaged kernels because it can detect their lower protein content and the presence of DON. Agnew’s survey found NIT technology was not readily available to Saskatchewan farmers. However, some seed cleaners were interested in adding the technology to their mobile seed-cleaning units once NIT becomes more economical and has a higher capacity for sorting large amounts of grain.

Agnew expects the capacities of optical and NIT sorters will likely increase as these technologies advance. She notes a common approach at present is to first clean the grain with a gravity sorter and then use one of these other technologies to further sort the grain. However, this process increases the time and cost per bushel for cleaning the grain.

In 2016, Agnew conducted trials to assess three disposal technologies – burning, composting and anaerobic digestion –in terms of their potential to provide an economic return and their effectiveness in killing the fungus.

“We selected burning because, other than dumping, it is probably the most common way of disposing of Fusariuminfested grain. You can burn it in a grain-burning stove or

you can pellet it and then burn it in a pellet stove,” she explains.“We looked at anaerobic digestion because some preliminary work in Europe indicated that digestion might deactivate the Fusarium spores, breaking them down in an oxygen-free environment.

“And we looked at composting because it is a pretty standard method of disposing of organic waste and it is easy to incorporate on to the farm.”

Although the CGC has wellestablished methods for measuring Fusarium graminearum concentrations in grain, it doesn’t have such methods for measuring mycotoxins in ash, compost and digestate. So, for this project, the CGC developed and validated a specialized method for measuring DON concentrations in these materials as an indicator of the Fusarium level.

All the trials compared wheat samples with high versus low DON levels. In the burning trial, the two types of wheat samples were burned in a grainburning stove. The CGC analyzed the DON concentrations in the ash. Also, the Alberta Innovates lab in Vegreville assessed the total energy content in the wheat samples.

The anaerobic digestion trial involved 18 vessels, including: six vessels with a manure mixture that included high DON wheat; six vessels with a manure mixture that included low DON wheat; and six vessels with only a manure mixture. In three of the six vessels within

Richardson Pioneer is committed to working with you at every stage of

At Richardson Pioneer, we know choosing the right product is only part of your success. We’re here to help you increase your yields profitably with expert agronomic advice and fully integrated service. From crop planning to grain marketing, we’re truly invested in helping you grow your business.

each treatment, the liquid at the bottom of the vessel was recirculated periodically for better contact between the microbes and the substrate. In anaerobic digestion, bacteria convert the carbon in manure and other organic materials into biogas, so biogas production was monitored during the trial. The CGC determined the DON levels in the digestate.

The composting trial included six piles. Two piles had a 50/50 mixture by volume of cow manure and low DON wheat; two piles had a 50/50 mixture of cow manure and high DON wheat; and two control piles had only cow manure. The CGC analyzed the composted material for DON levels.

Agnew’s team also conducted a preliminary economic analysis of the different disposal options.

Based on the results from these trials, anaerobic digestion was the least promising option. It decreased the DON concentration in the digestate, but didn’t eliminate it. On top of that, very little biogas was produced and anaerobic digestion requires special equipment. Overall, this technology does not appear to be practical for farm disposal of Fusarium-infested grain.

In the burning trial, the temperature during burning was estimated to be between 150 C and 300 C. Burning reduced the concentration of DON in the ash but did not eliminate it. Agnew says, “So you can extract energy value from burning Fusarium-damaged grain, but you have to be careful about disposing of the ash because there is still potential for spreading the fungus in that ash.”

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. These products have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from these products can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for these products. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready 2 Xtend® soybeans contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate and dicamba. Agricultural herbicides containing glyphosate will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate, and those containing dicamba will kill crops that are not tolerant to dicamba. Contact your Monsanto dealer or call the Monsanto technical support line at 1-800-667-4944 for recommended Roundup Ready® Xtend Crop System weed control programs. Roundup Ready® technology contains genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, an active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Agricultural herbicides containing glyphosate will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate.

Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individuallyregistered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole and fluoxystrobin. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole, fluoxystrobin, and clothianidin. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for corn plus Poncho®/VOTiVO™ (fungicides, insecticide and nematicide) is a combination of five separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole, fluoxystrobin, clothianidin and Bacillus firmus strain I-1582. Acceleron® Seed Applied Solutions for corn plus DuPont™ Lumivia® Seed Treatment (fungicides plus an insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, prothioconazole, fluoxastrobin and chlorantraniliprole. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for soybeans (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin, metalaxyl and imidacloprid. Acceleron® seed applied solutions for soybeans (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin and metalaxyl. Visivio™ contains the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil, thiamethoxam, sedaxane and sulfoxaflor. Acceleron®, CellTech®, DEKALB and Design®, DEKALB®, Genuity®, JumpStart®, Monsanto BioAg and Design®, Optimize®, QuickRoots® Real Farm Rewards™, RIB Complete®, Roundup Ready 2 Xtend®, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready®, Roundup Transorb®, Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup Xtend®, Roundup®, SmartStax®, TagTeam®, Transorb®, VaporGrip® VT Double PRO®, VT Triple PRO® and XtendiMax® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC. Used under license. BlackHawk®, Conquer® and GoldWing® are registered trademarks of Nufarm Agriculture Inc. Valtera™ is a trademark of Valent U.S.A. Corporation. Fortenza® and Visivio™ are trademarks of a Syngenta group company. DuPont™ and Lumivia® are trademarks of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. Used under license. LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. Herculex® is a registered trademark of Dow AgroSciences LLC. Used under license. Poncho® and VOTiVO™ are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license.

concentration of DON mycotoxin in the ash was reduced but not eliminated.

Assuming the ash could be properly disposed of, the project’s economic analysis indicated that if highly damaged grain could be purchased for $1 to $3 per bushel, then burning the grain could be a cost-effective way of producing heat compared to traditional fuels.

Composting turned out to be the most promising option. All of the compost samples had undetectable levels of DON, which surprised the researchers. “Composting usually promotes fungal growth. Since Fusarium is a fungus, we hadn’t expected much of an effect,” Agnew says.

She notes, “Our hypothesis is that during the composting process, which heats the compost up to about 60 C to 70 C, it is wet heat and additional microbial activity is happening in the compost pile that somehow eliminates the DON.”

Agnew explains that the cost/benefit of composting strongly depends on the availability of space, a tractor and mixing materials such as manure. “If all of that is available, then composting could be a low-cost option for disposing of Fusariuminfested grain, depending on the availability of a market for the compost and depending on evidence proving that the Fusarium fungus [and not just the DON] is gone from the compost.”

The project’s results show promise for not only extracting value from heavily infested grain but also for minimizing the potential to spread FHB. If Agnew and her CGC colleagues are able to obtain funding to continue this research, the team plans to find a way to directly measure Fusarium levels in compost as part of the research.

“This study revealed some pretty interesting things,” Agnew concludes. “The Canadian Grain Commission was really interested in the results. They are pushing for additional work and to publish the initial results, so we are working with them on that. And the results may also be presented at the World Mycotoxin Forum in 2018 because of the interest in this issue and the fact that no one else has really seen this effect due to composting.”

Continued from page 25

from 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 per cent at the time of swathing, or direct harvest alone and direct harvest plus pre-harvest glyphosate.

Willenborg will also be investigating alternative cultural and herbicide combinations for managing perennial weeds in oat. The full analysis and final project results will be available in 2019, including seed quality and functional analysis.

“So far it doesn’t appear that glyphosate is having an adverse effect on oat seed quality or functionality, and if anything is showing a small quality benefit to having glyphosate applied prior to harvest,” Willenborg says. “The key is to follow the label directions for preharvest application and make sure the crop is at 30 per cent moisture or lower, which corresponds roughly to the hard dough stage of development. All of our research treatments have been completed according to the label, but once you get off label in terms of timing we don’t know what will happen with glyphosate residues.

“For example, in some of our earlier work with lentil, the results were fine as long as label directions were followed, but as soon as application got off label in terms of timing and at higher moisture content, [that’s] where problems with quality and MRLs showed up. We expect that may be similar to oat, which is often harvested late in the season, when growers are between a rock and a hard place, with frost or heavy rains threatening harvest.”

Although it can be a challenge to apply glyphosate at the proper timing, there can be serious consequences due to not adhering to the label timing. Always follow the label, and check with your grain buyer about the acceptance of all pre-harvest and other product use and MRLs for all crops, including oats.

It’s time to lower the boom on your most serious weeds and combat resistance at the same time. As the only Group 10, Liberty® herbicide provides growers with a powerful tool to address the weed concerns of today and tomorrow.

Plant breeding program allows farmers to select their ideal varieties.

by Julienne Isaacs

Not many farmers can say they’ve had a hand in earlystage selection of the very crops they’re growing in their fields, but the University of Manitoba’s Participatory Plant Breeding Program is making this possible for producers coast-to-coast.

The program’s goal is to allow farmers to have a direct hand in crop variety development. Collaborating with plant scientists and breeders, farmers are invited to plant new cultivars of wheat, oats and potatoes and make selections on their farms with the ultimate aim of developing varieties that are ideally suited to their unique needs and growing conditions.

The program was started in 2011 by instructor Gary Martens and technician Iris Vaisman in collaboration with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) wheat breeder Stephen Fox. Today the program is run by the University of Manitoba’s Martin Entz and coordinator Michelle Carkner. Funding comes from AAFC and the Bauta Family Initiative on Canadian Seed Security.

Entz and Carkner now do the wheat crosses themselves and offer oat crosses from Jennifer Mitchell Fetch at AAFC’s Brandon Research Centre. They also offer open-pollinated potato varieties developed by Duane Falk at the University of Guelph.

In its seven years of existence, the program has seen involvement from more than 100 producers across the country.

Entz and Carkner aim to visit most of the program’s farmers at least once during the growing season to talk to them about selections and the challenges.

This year, participating farmers planted a wide variety of wheat crosses with varying characteristics, such as a Unity/ Red Fife cross, an AAC Scotia/Norwell cross and a Carberry/AC Tradition cross. Oat crosses, mostly between numbered cultivars, had parentage with varying disease resistance, yield potential and oil content.

First, Carkner and Entz grow out wheat populations to the F3 generation. Then Carkner sends participants the lists of wheat and oat populations available for the coming season; the lists include information on parentage and agronomic characteristics. Producers make selections (with Carkner’s and Entz’s help, if required) and are sent enough seed for a 20 square metre plot (about 5,000 seeds) per variety. The producers can choose whether to grow out one or two varieties, or up to five or six, depending on their comfort level.

Farmers seed the plots by hand or using garden seeders. They’re provided with materials to guide them through the selection process based on their local needs. “If it’s disease or rust they’re concerned about, for example, we tell them when to go out and select for that. If they want something that is later maturing or early maturing, we tell them when to do that,” Carkner says.

Carkner and Entz try to schedule their site visits for key selection times. “We give them pointers and just encourage them, because a lot of times farmers don’t feel they have the confidence or observational skills, like breeders, to make selections,” Carkner says. “But we tell them, ‘You know what a good crop looks like. Whatever looks best to you on your land is what natural selection has selected.’ ”

Farmers select about 500 spikes or panicles and send them back to the University of Manitoba, where some are archived.

This year, Carkner increased seed for three farmers on the wheat side and two on the oat side. In the future, she hopes the program will shift its emphasis from breeding to increasing seed.

Carkner says the program has two main challenges. The first stems

from increasing seed: the University of Manitoba has the resources to increase seed for a good number of farmers, but shipping enough seed back to farmers for them to move from the garden seeder to the drill is a major enterprise.

The second challenge relates to registration.

“Farmers are thinking about their neighbours,” Carkner says. “They want their varieties registered so they can sell the seed and other farmers can benefit from their work, but you can sell it as grain but not seed. So the solution, under the current system, is to try to register the variety, but this takes an enormous amount of resources, time and money.”

Carkner and Entz currently offer the breeding lines to Brandon Research Centre and anyone else who wants to develop them. But they’re also open to working with farmers who want to pursue their own avenues to marketing.

Not all the farmers in the program are organic, but the program works particularly well for niche producers with markets for unregistered varieties.

Ian Cushon, who runs an organic grain and oilseed farm near

Oxbow, Sask., is a long-term member of the program. This year, he asked Carkner to scale up one wheat population so he can take it to the next level in his operation.

It’s an experiment, because until Cushon gets enough volume to grow out a significant amount of the seed, it’s hard to test it – both for quality baking characteristics and for market accessibility.

He is enthusiastic about being involved in the selection process. “These initial crosses are not 100 per cent homogenous – there’s some variability in the population,” he says. “As organic farmers, we want and select for varieties with certain attributes, and within those varieties there could be beneficial variations.”

The program takes some commitment during the busiest times of the season, Cushon says, but it doesn’t take much time because the plots are small. Producers need to be fairly knowledgeable about diseases and negative qualities to watch out for, but these are skills that farmers, for the most part, already have.

“This is the process farmers have gone through for thousands of years – they’ve looked for seeds to save for the next season. It’s good to have farmers involved in their own selection process.”

WELCOME TO THE EXCITING NEW WORLD OF PROVEN® SEED

Our new seed lineup changes everything. Proven performance in canola, cereals and forages. And now Proven in corn and soybeans. Proven by CPS retailers and agronomists, dedicated to providing leadership in yield, disease management, trials and advice — plus an all-new performance package that’s Proven, like never before. Available only at your CPS retail. We’re with you.

Midge-tolerance and improved yields are highlighted in these new cereal varieties.

by Top Crop Manager Staff

Cereal breeders continue to focus on improved yields, developing varieties that stand up to the pest and disease challenges producers face across the Prairies. Seed companies have supplied Top Crop Manager with the following information on new cereal varieties for 2018.

Growers are advised to check local performance trials to aid them with their variety selections.

AAC Cameron VB is a midge-tolerant wheat and offers very high yield, with resistance to orange wheat blossom midge. AAC Cameron VB is an awned variety with improved lodging tolerance and reduced DON accumulation. Available at Canterra Seeds retailers.