TOP CROP MANAGER

FRESH LOOK AT WHEAT

Researchers are looking at wheat’s nutritional benefits

PG. 6

DIRECT

SEEDING INTO TALL STUBBLE

Increase yield and water

PG.13

KNOW YOUR ENEMY

Using genomics to fight rust

PG.48

Researchers are looking at wheat’s nutritional benefits

PG. 6

SEEDING INTO TALL STUBBLE

Increase yield and water

PG.13

KNOW YOUR ENEMY

Using genomics to fight rust

PG.48

Carolyn King

Carolyn King

BRUCE

This issue of Top Crop Manager has a special focus on plant breeding and genetics in light of the important role it plays in developing higher-yielding, more nutritious wheat, and in highlighting the nutritional benefits to consumers. In 2012, we are focusing mostly on wheat, in recognition of the valuable part it plays in feeding the world. In 2011, the global population surpassed seven billion, and 20 percent of calories consumed globally come from wheat. A recent United Nations report predicts that food production will have to increase by 45 percent by 2030, and wheat will have to provide a significant portion of that increased production.

In Canada, wheat contributes about $4 billion annually to the Canadian agricultural industry, and another $7 billion in value-added processing of wheat. Clearly, wheat is an important crop to Canadians and the growing world population.

But all is not good in the land of wheat. Recent low-carb diet books have thrown down the challenge for wheat breeders, and the claims in these books give me a pain in my wheat belly. Among the contentious claims is that wheat has been so dramatically changed by plant breeders that it is the cause of everything from diabetes to heart disease to immunological and neurological disorders to the world’s growing obesity. In response, leading Canadian researchers and plant breeders like Dr. Ron DePauw and his colleagues have looked into the nutritional composition of wheat going back to the 1800s in major landraces, including Red Fife. Their verdict is found in our feature story written by Carolyn King on page 6 of this issue.

The researchers aren’t stopping there. They are looking at how wheat breeding can go further and improve the nutritional components of wheat without dramatically affecting other breeding objectives of yield and agronomic functionality.

DePauw, who is featured on the cover, also played a major role in bringing you the poster of the Genealogy of Canada Western Red Spring wheat that is found in this issue. He not only helps maintain the genealogy, along with plant breeder Richard Cuthbert, but also has contributed to the development of 47 wheat cultivars and six triticale cultivars since his career began in the mid-1960s as a graduate student. Top Crop Manager first brought this poster to you in last year’s October issue, and we are pleased to bring you the updated version for 2012, reflecting new variety registrations.

The challenge for Canadian wheat going forward, though, is investment in research and development. In the mid-1960s, global wheat production was less than 400 million tonnes and the theoretical maximum yield was around 15 tonnes per hectare. That yield has been surpassed in some countries, and now researchers are targeting 20 tonnes per hectare.

How can we get there? Will Canadian wheat farmers be able to keep up with global competition? Australia is investing $80 million in wheat development, but Canada is only investing around $15 to $20 million per year. Certainly growing demand for wheat will help funnel additional dollars into wheat research but more will be needed. A good start is the Saskatchewan government’s recent announcement of $10 million in new funding over five years for wheat research.

Whether wheat will once again reign as king in crop production on the Prairies remains to be seen. What is clear, though, is that research will drive the crop forward, both in developing higheryielding, more nutritious wheat and in highlighting the nutritional benefits to consumers who may be misinformed by fad diets.

Personally, I won’t be giving up my wife’s whole-wheat banana chocolate muffins in the morning anytime soon.

OCTOBER 2012, VOL. 38, NO. 11

GROUP PUBLISHER Diane Kleer dkleer@annexweb.com

WESTERN FIELD EDITOR bruce@haywirecreative.ca

WESTERN SALES MANAGER kyaworsky@annexweb.com

EASTERN SALES MANAGER smccabe@annexweb.com

SALES ASSISTANT achen@annexweb.com

MEDIA DESIGNER Katerina Maevska

PRESIDENT Michael Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com

RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT. e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com

Printed in Canada

CIRCULATION e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com

SUBSCRIPTION

-

-

March, Mid-March, April, June, October, November and December -

March, April, September, October, November and December

The all-new Steiger ® Rowtrac™ Series is built on four equal-sized, independent, oscillating tracks and a narrower suspension system straight from the factory. Four tracks mean you get proven Case IH Quadtrac® technology, giving you the most horsepower available when tackling row crop applications — resulting in more productivity. The Steiger Rowtrac Series, with the Efficient Power of our exclusive SCR engine technology, puts you at the forefront of farming innovation. Visit your local dealer or go to caseih.com/4isgreaterthan2

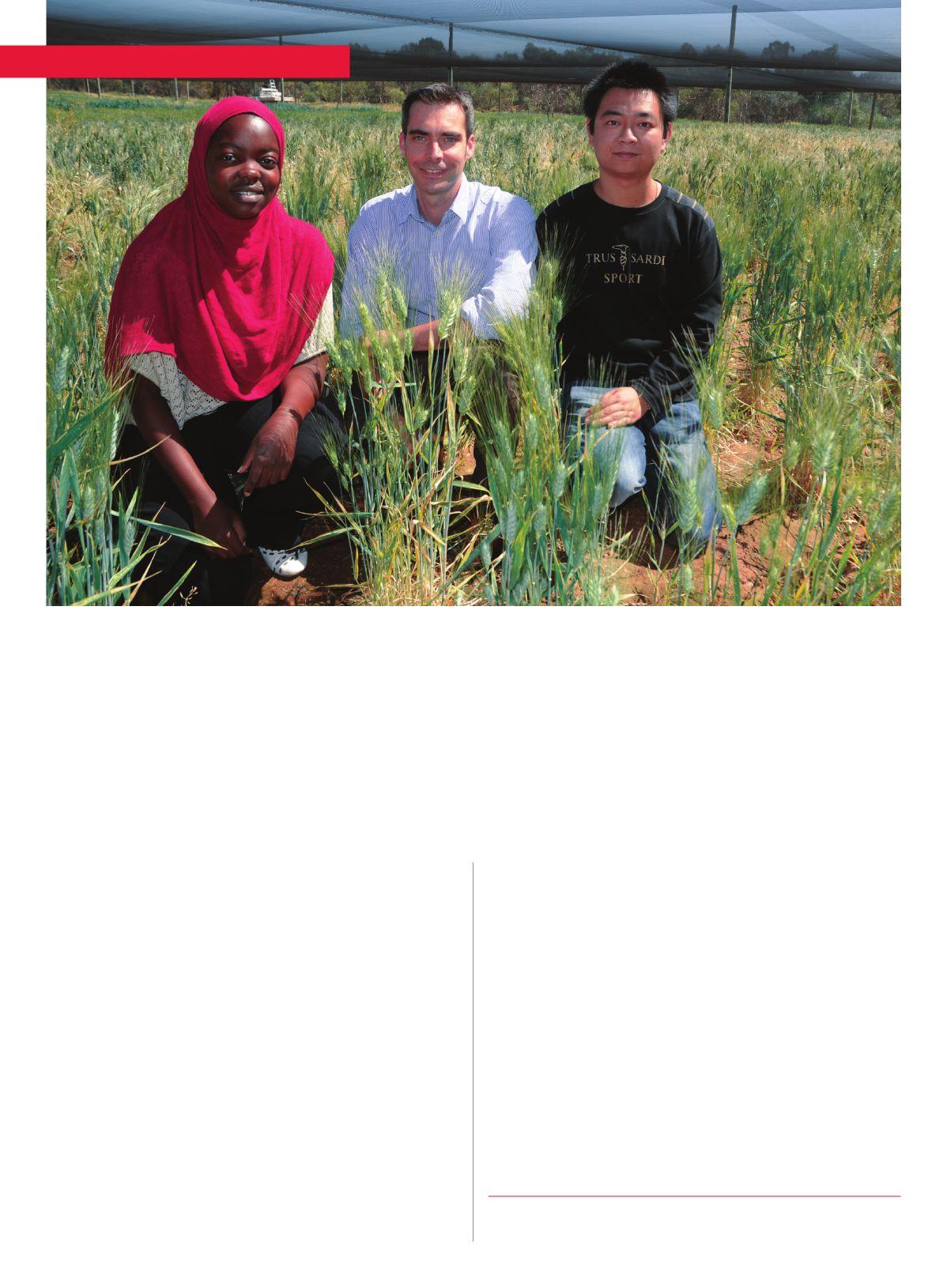

In light of recent fad diet books, researchers are looking at wheat’s nutritional benefits.

by Carolyn King

Wheat is such a common part of Canadian diets that sometimes we take it for granted. However, with some recent popular books advocating low-carb or no-wheat diets, public attention is being drawn to wheat for a closer look. Is eating wheat good or bad for us? Has breeding caused negative changes in wheat’s health effects? Scientific evidence shows wheat actually has a lot going for it, but that doesn’t mean we can’t try to make it even better as a nutritious food with a key role in feeding the world’s growing population.

Thousands of years of selecting better wheats

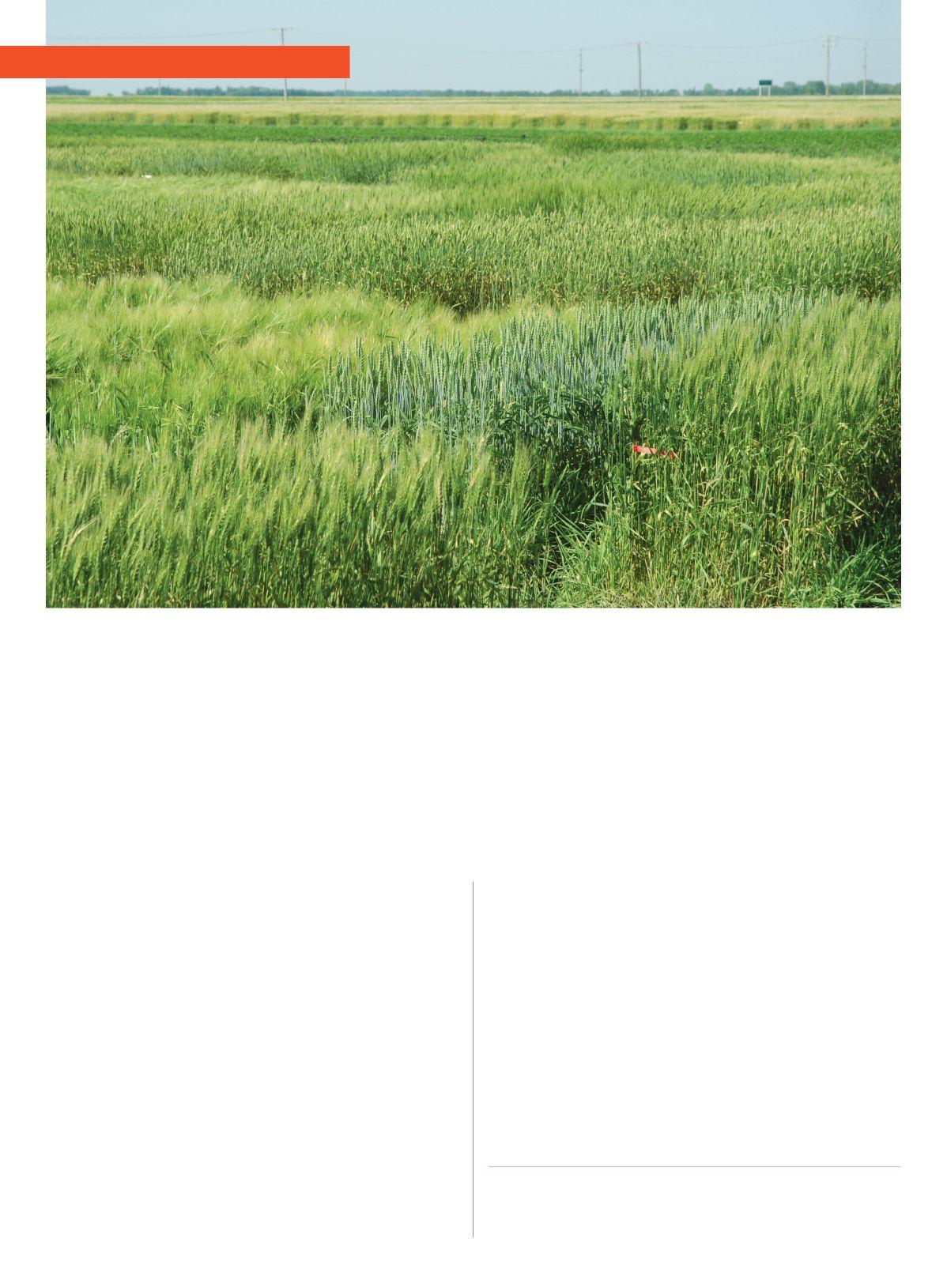

one of the criticisms aimed at wheat in a recent diet book is that breeders have made changes in wheat varieties over the last 50 years that are “drastic” and “bad.” To address that viewpoint, Dr. ron Depauw, a wheat breeder with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC), looks at the history of wheat.

Wheat’s origins reach back to the very beginnings of agriculture around 12,000 years ago. at that time, in a part of the Middle east

called the Fertile Crescent, humans started to go from just gathering seeds of wild grasses for food, to cultivating and domesticating them –planting and harvesting the seeds, and selecting seeds with preferred characteristics to plant for their next crop.

“all of the variations in the natural world around us are the result of natural mutations. Mutations with an advantage for people are the ones that people select and perpetuate,” explains Depauw. “The domestication of wheat is based on some key natural mutations followed by selection by humans.”

The first key mutation made harvesting easier. “In these wild grasses, the ripe spike broke apart and the seeds fell to the ground, so people had to stoop over and pick up the seeds. Then somebody noticed a type where the spike did not break apart, which made collecting the seeds much easier,” says Depauw. a second mutation allowed the chaff to

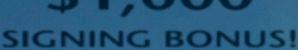

ABOVE: Wheat breeding plots, AAFC’s Cereal Research Centre: Modern wheat breeding techniques rely on the same natural processes in a wheat plant that have created variation in wheats over thousands of years.

come off the seeds more easily, so it was easier for people to get at the edible part of the seed. He notes another crucial change: “Several of these grasses intermated and doubled their set of chromosomes spontaneously to produce a new species of grass which is now known as wheat.”

over the centuries, as people moved from the Fertile Crescent into europe, asia, africa and beyond, they took wheat with them. They grew it in these new areas and continued to select seeds with preferred traits.

“There was no such thing as pure strains at that time; people were growing mixed populations that we call landraces. With this genetic diversity from one plant to another in the landraces, you can have natural hybridization [mating of two distinctly different lines],” he notes. “In wheat, male and female parts are in the same flower. When the male fertilizes the female, the fertilized ovule develops into a wheat kernel. From time to time under natural stresses, the male does not develop, so the female can be fertilized by pollen from another wheat plant. But it could be a plant with quite different characteristics, so the resulting seed is a natural hybrid. The offspring recombines the genes of its parents, and you get natural variation. and, if humans see an advantage in the variation, they select it.”

This approach to improving wheat – waiting for natural changes and then using selection – continued over thousands of years. Then, beginning around the early 1900s, people started to become more efficient at improving wheat and other crops, as their understanding of the principles of inheritance grew, and as breeding techniques advanced.

“Improvements in wheat are more rapid now because we are able to target hybridization and to use more sophisticated selection techniques. But just because you target a mating, doesn’t mean it’s evil, nor

does it mean you’re making something inferior,” states Depauw.

He emphasizes, “The techniques for breeding wheat are the same as those for other crops. To make a new fruit or vegetable or wheat or legume variety, you mate a male with a female, each of which has some attributes that you want. From the offspring, you choose the ones with the best attributes.”

This more targeted varietal development has been a key element in the success of Canadian wheat production. Depauw gives an example: “a hundred years ago, the wheats being grown in Canada were susceptible to some races of stem rust. This disease can cause up to about a 90 percent crop loss. people at the time had to learn a lot about the stem rust pathogen and about wheat, and then figure out how they could control stem rust using natural genetic variation of wheat.”

Breeders crossed Marquis, a high-yielding variety that possessed good milling and baking properties, with other wheats that had some rust resistance, and eventually they created Thatcher. over time, the stem rust pathogen evolved to overcome Thatcher’s resistance gene, so breeders developed other wheat varieties with different resistance genes. “We have been fighting stem rust for about a century, and we have been able to stay ahead of it since about 1954, when that last major epidemic occurred in Canada,” notes Depauw.

These days, plant pathologists watch the stem rust pathogen for new virulent mutations, so breeders can try to keep a step ahead of the pathogen. For instance, the Ug99 strain of stem rust and its variants have evolved to overcome some key resistance genes used in about 80 percent of the wheat varieties globally. Breeders in Canada and around

the world are working on lines with Ug99 resistance.

Modern breeding techniques are crucial for fighting such diseases.

“Waiting for nature to produce a wheat mutation with resistance to this pathogen could take hundreds and hundreds of years, and in the meantime people would be going hungry,” says Depauw. Wheat plays a huge part in feeding the world, and widespread losses of wheat crops would be devastating, resulting in hunger and famine.

other examples of advances through Canadian wheat breeding include resistance to the latest strains of various diseases, resistance to wheat stem sawfly, resistance to orange wheat blossom midge, better water-use and nitrogen-use efficiency, better qualities for various food uses, and tolerance for conditions such as drought, frost and wet weather before harvest.

a recent diet book has suggested that wheat varieties developed in the last 50 years may not be safe. In Canada, new varieties of wheat and most other agricultural crops are registered through the Canadian

Food Inspection agency’s variety registration system. Before a variety is registered, it is tested to make sure it meets current standards for agronomy, disease resistance and quality. The registration system ensures that health and safety requirements are met, and helps maintain and improve grain quality standards. For instance, plants with novel traits go through an extensive review to check the plant’s safety for the environment and human health.

and there are other checks on the safety and quality of Canadian wheat. “The Canadian grain Commission is responsible for grading grain, which includes safety. For example, we test wheat for diseases such as ergot and fusarium that pose potential health hazards. and we establish tolerances to ensure that anything going into the milling industry is well within any safety levels that would be required,” says Dr. nancy edwards.

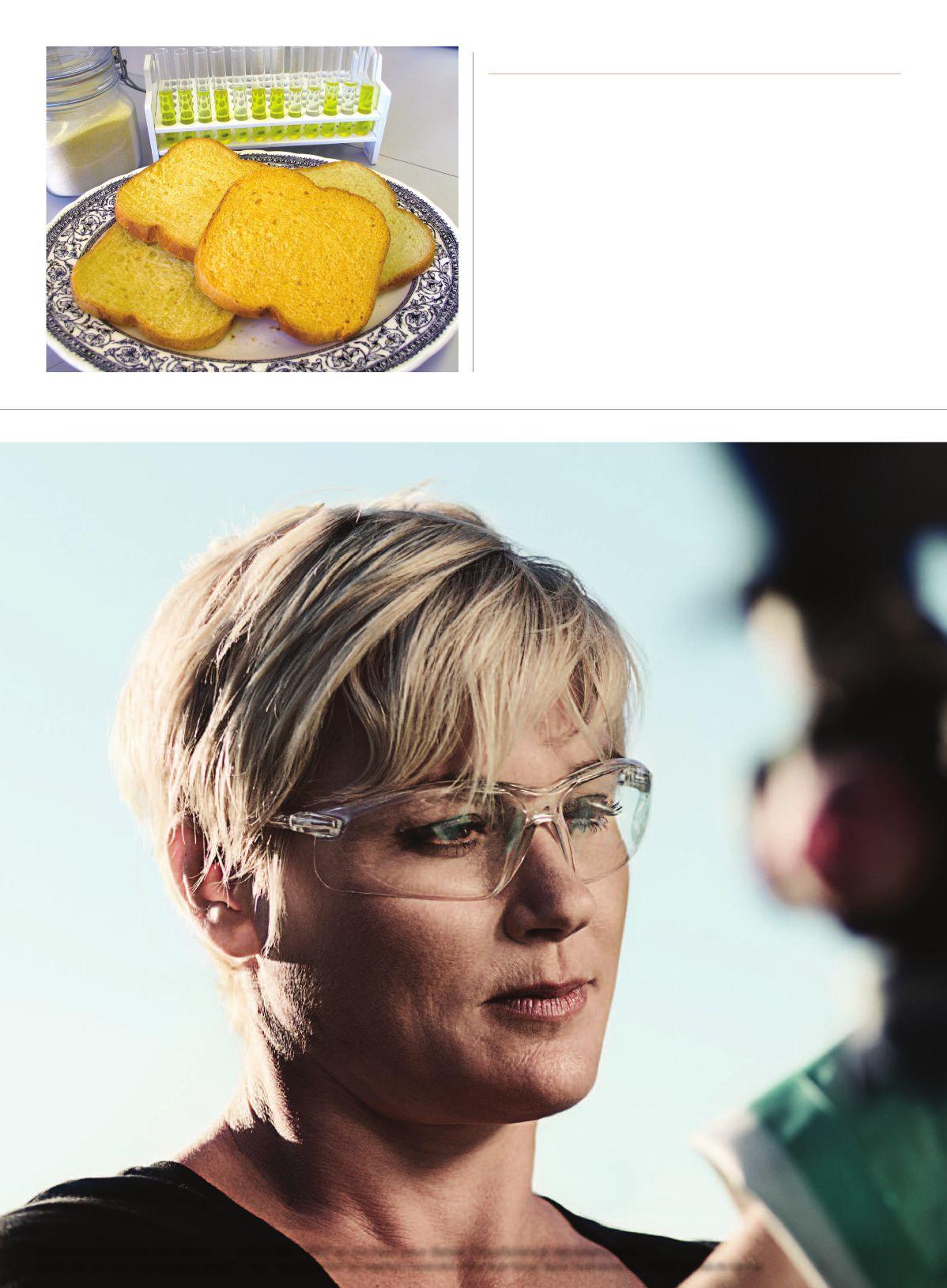

edwards is the program manager of the Canadian grain Commission’s Bread Wheat research program. This program studies how Ca-

nadian wheat flours behave in response to processing conditions in the baking industry. For instance, the program’s researchers investigate factors affecting wheat-processing quality, evaluate the quality of advanced breeder lines and provide guidance to breeders.

In response to a popular diet book’s claims that wheat consumption is linked to a wide range of health problems, Dr. nancy ames emphasizes, “Having scientific evidence before making these kinds of statements is crucial. But if there is scientific evidence to support some of these claims about wheat, then we should address those for Canadian wheat varieties, testing our wheats to see if we find anything like that.” as a food scientist with aaFC in Winnipeg, ames says, “I work on grains because I believe them to be nutritious. Whole grains and grains

InVigor® growers are no different from other growers. They don’t get up earlier, work harder or longer than their neighbours.

For the most part, they also look the same. Except for their remarkable composure when faced with adverse conditions.

Nothing outperforms InVigor.

in general have provided our society with energy, macronutrients and micronutrients important to our survival. Wheat is a really good example of that. It is one of the most widely consumed food products in the world, and it has a very important role to play in the future for feeding the world’s growing population.”

She highlights some examples of results from scientific studies that show health benefits of wheat, especially wheat fibre. “Studies have shown wheat bran fibre consumption is associated with increased satiety, weight control and insulin sensitivity, so that really suggests a positive effect of wheat on obesity and metabolic disease. For instance, in clinical trials some types of fibres have been shown to increase satiety, making you feel fuller faster, so you tend not to eat as much. arabinoxylan is one of the fibres in wheat, and it’s been shown to reduce glycemic response [which helps with problems like diabetes]. and a recent

study found that increasing intake of whole grains, including wheat, is associated with lower [fat tissue levels] in adults.”

although there have been many studies demonstrating health benefits from wheat and from specific bioactive compounds in wheat, ames says people often aren’t aware of these benefits. She adds, “Maybe as a scientific community, we need to start teaching people about those nutritional benefits.”

one issue that people are sometimes concerned about is gluten and whether changes in wheat gluten in recent decades are causing such problems as an increasing incidence of celiac disease (a condition triggered by gluten consumption). gluten is a type of protein in wheat and some other cereals. It gives dough elasticity so it’s important for things like making bread.

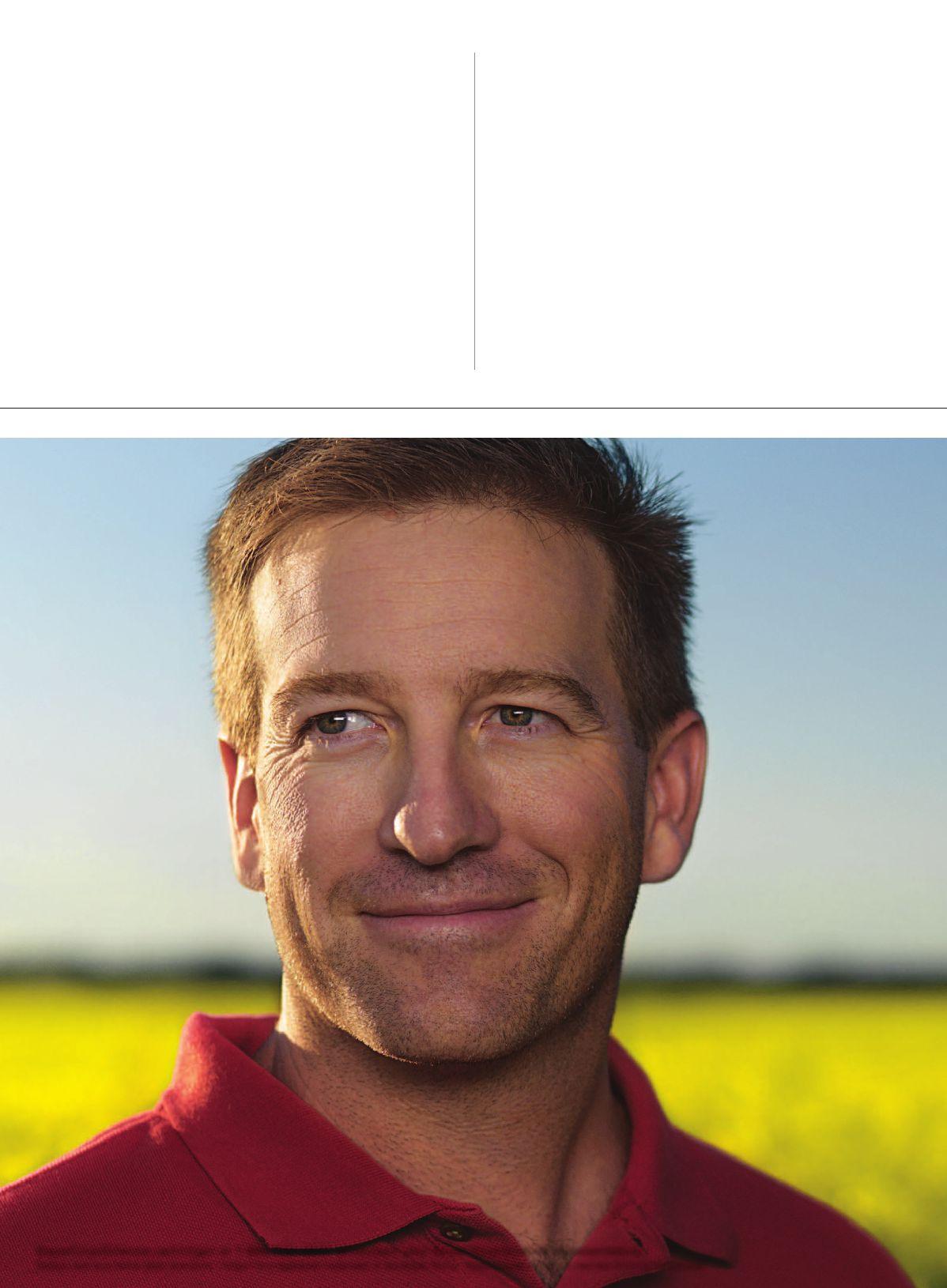

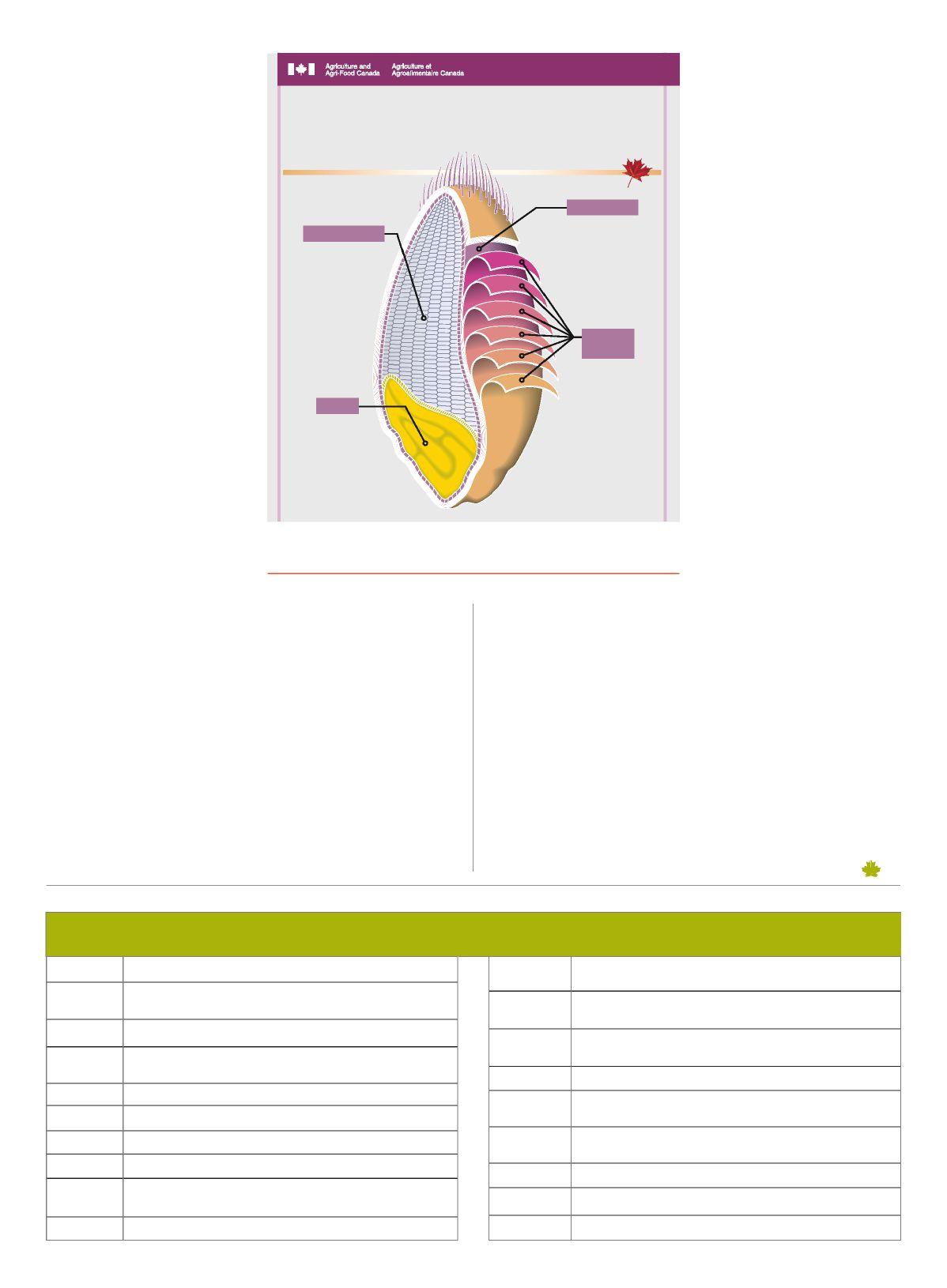

To determine whether this concern might apply to Canadian wheats, Depauw and Dr. odean Lukow from aaFC’s Cereal research Centre investigated gluten properties in Canadian western red spring (CWrS)

wheats. They examined two gluten proteins – glutenins and gliadins –in landraces from the 1800s and in various cultivars developed over the years since 1900.

“We showed that the functionality [the milling and baking quality] in CWrS wheats came from red Fife [a major landrace in the 1800s]. Canadian wheats have been able to maintain that functionality all the way through to contemporary times, even though we have used many different wheat strains with different [types of glutenin and gliadin components],” says Depauw. So in CWrS wheats, gluten characteristics haven’t changed all that much because breeders have continually selected for maintaining the milling and baking quality of our wheats, and maintaining gluten characteristics helps to maintain that quality.

Milling and baking quality has been a key objective of Canadian wheat-breeding programs for many years, along with increasing wheat yield, reducing plant disease and minimizing crop inputs. ames would like to see nutrition improvements added to that list of

She is a wife, mother, business partner, advisor and confidant. She wears all these hats and more, ensuring everyone is taken care of and that the business runs smoothly.

InVigor® needs Liberty® the same way. Liberty herbicide is the backbone of the LibertyLink® system and together they’re powerful partners.

breeding objectives.

“If we could identify some places where we can improve wheat’s nutritional components without dramatically affecting the other breeding objectives, it would be an opportunity to improve the profile of wheat as a nutritional grain,” she says.

ames has been working on this possibility with aaFC wheat breeders and researchers, including Depauw, Dr. gavin Humphreys, Dr. Stephen Fox and Dr. Mark Jordan. They have been screening wheat germplasm for lines with higher levels of nutritional components, such as betaine, lutein (which helps maintain eye health), some of the plant sterols, and arabinoxylan. Identifying this type of genetic variation will give breeders a starting place for enhancing wheat’s existing nutritional attributes.

Many of wheat’s nutritional components are concentrated in the outer layers of the kernel. So a key aspect of capturing wheat’s goodness is to encourage more people to choose whole-wheat options. ames notes, “Whole wheat products are widely available these days, but we need to focus more on how to make those whole-wheat products more acceptable to consumers. For instance, are there some varieties that taste better than others? probably there are. Those are things we can move forward on, while making sure to maintain the milling and baking quality, grain yield and so on.”

“Some people are saying negative changes have occurred [in the nutritive value and quality of wheat] over the years, but they are saying this without any evidence,” notes Depauw. To see if any negative changes have occurred in Canadian wheats, he has teamed up with edwards and ames in a project called red Fife and Descendants. He

Dr. Nancy Ames / Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada / Richardson Centre for Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals wheat

Primary attributes

ladoga early maturity

hard Red Calcutta early maturity

Red Fife milling and baking quality

marquis early maturity, wide adaptation and milling and baking quality

thatcher Resistance to stem rust added to marquis

neepawa Resistance to stem rust added to thatcher

Katepwa Resistance to stem rust added to neepawa

Columbus Preharvest sprouting resistance added to neepawa

laura Lr34 (a specific leaf rust resistance gene) leaf rust resistance, water- and nitrogen-use efficiency

CDC teal early maturity, lr34 leaf rust resistance

says, “This project will provide the first documented evidence to show if such changes actually have occurred.”

Examples of food products made from wheat

Their study involves 20 important wheats from over a century of Canadian wheat production. Depauw notes, “all of the wheat grown in Canada originates from landraces. We’ve included the two key landraces, red Fife and Hard red Calcutta, as well as a third one called Ladoga.” over the years, breeders have added various attributes, such as resistance to diseases and insect pests, to the descendants of these three landraces (see table).

The wheats are being grown at Indian Head and Swift Current. Depauw will examine their agronomic characteristics, ames will analyze their nutritional characteristics, and edwards will analyze their milling and baking properties.

edwards already has some initial results from her part of the study. “We’re looking at everything from the protein content and quality through to the milling and baking quality. We’ve started the milling analysis and we are seeing some improvement in the milling properties of the varieties since red Fife, Hard red Calcutta and Ladoga.”

She adds, “Sometimes in the popular press, people say some of these old varieties work much better than the newer ones, but that’s not necessarily the case. our quality data show red Fife was quite a good variety, but we have definitely made improvements since that time in terms of milling and baking performance.”

good science relies on continually evaluating where you’ve come from and where you’re going. red Fife and Descendants will provide objective information on how far we’ve come with Canadian wheat and could possibly help point to some great future directions.

AC barrie Fusarium resistance, water- and nitrogen-use efficiency

AC elsa Lr34 leaf rust resistance, water- and nitrogen-use efficiency

mcKenzie Lr21 leaf rust resistance, water- and nitrogen-use efficiency

superb semi dwarf, water- and nitrogen-use efficiency

lillian Resistance to wheat stem sawfly and resistance to leaf and yellow rust

97b64-F9A3 lr21 leaf rust resistance, resistance to orange wheat blossom midge

5603hR lr21 leaf rust resistance, fusarium resistance

Carberry semi dwarf, fusarium, leaf rust and yellow rust resistance

CDC Kernen Fusarium resistance, water- and nitrogen-use efficiency

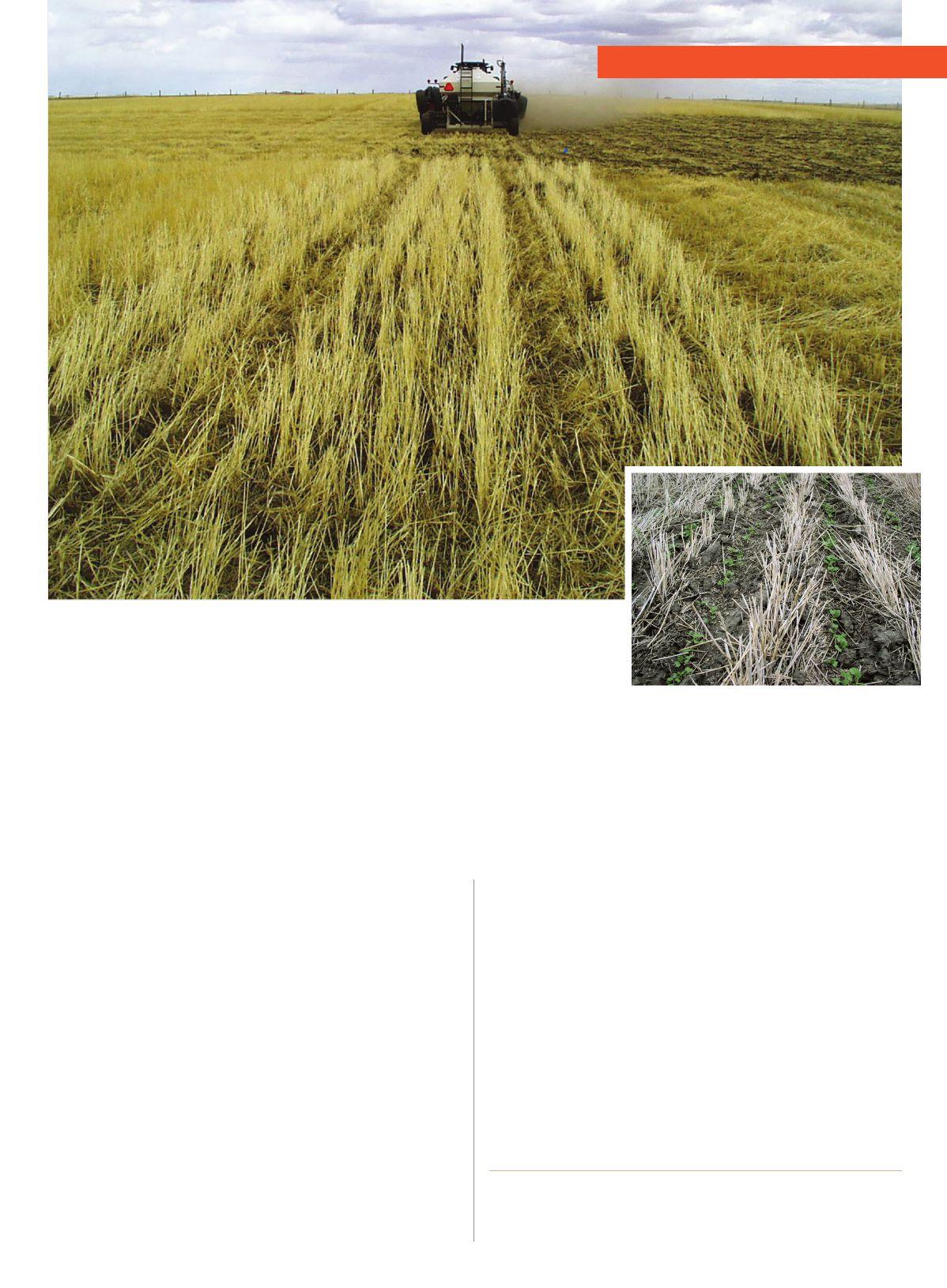

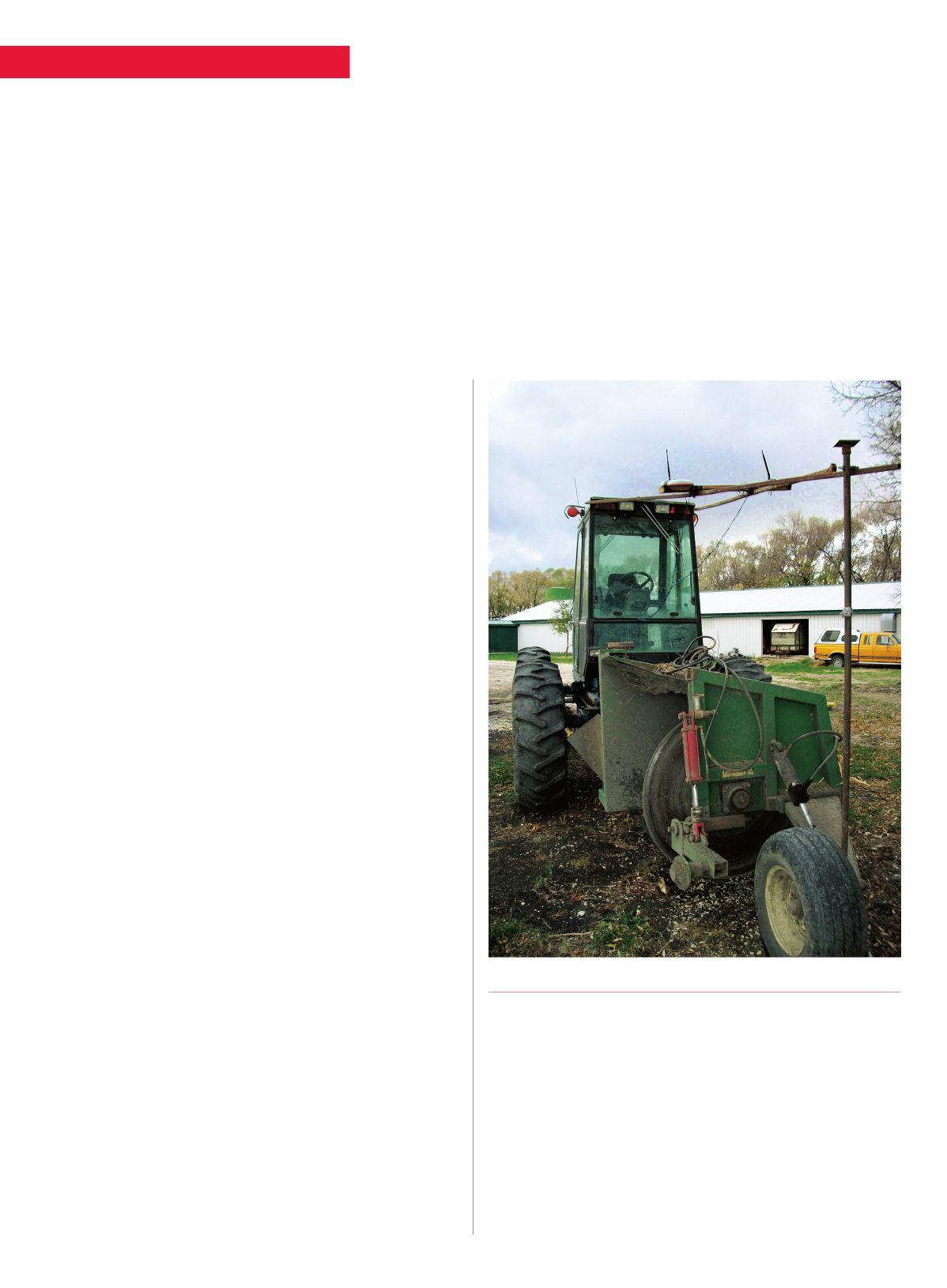

Increasing stubble height can increase yield and water use efficiency of cereal, canola and pulse crops.

by Donna Fleury

Low disturbance direct seeding systems have many advantages, including agronomic, economic and environmental.

However, determining the optimal stubble height for maximizing yields and water use efficiency in direct seeding systems depends on several factors. researchers at the agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) research Centre in Swift Current, Saskatchewan, have been working on the microclimate impacts of various stubble heights over the past few years.

“over the years, our research focused on direct seeding cereal, canola and pulse crops into cereal stubble,” explains Dr. Herb Cutforth, research scientist with aaFC in Swift Current. “We compared various stubble heights and measured several microclimate parameters to determine their impact on yield, water use efficiency and other factors. overall our results showed that the taller the stubble, the greater the yield and water use efficiency. Dr. Brian McConkey and I have continued this study looking at canola stubble and so far are seeing similar effects as with cereal stubble.”

For the study, research trials were set up in the fall leaving all of the

cereal stubble at the same height, so spring soil moisture conditions would be similar across the plots. In the spring, just before seeding, the stubble was reduced to various heights. The stubble heights included no stubble or cultivated (0 centimetres), short stubble (6 inches, or 15 centimetres), tall stubble (12 inches, or 30 centimetres) and extra tall stubble (>18 inches, or >45 centimetres). Several climate parameters were measured throughout the growing season, including soil temperature, wind speed, evaporation, air and plant temperatures.

“The results showed that the taller the stubble, the better the microclimate conditions and the higher the yields,” explains Cutforth. “averaged across the four years of each study, yields were 12 to 15 percent higher on extra tall stubble as compared to cultivated stubble. In some years, the yields were even higher, with the highest yields consistently from the extra tall stubble trials. The yield advantages were similar for

TOP: Seeding into tall stubble requires careful selection of seeding equipment.

INSET: Tall stubble creates a better microclimate that reduces stress on seedlings.

all crops, although pulses don’t seem to be quite as responsive” although water use efficiency was better under taller stubble conditions, the actual crop water use was the same and did not depend on the height of the stubble. “We have found similar results from other research projects on crop water use, but the important difference in this study is the improvement in water use efficiency as stubble height increased,” says Cutforth. “Microclimate conditions are better under taller stubble heights, with the reduction in wind speed one of the most important factors. Wind speeds were reduced by 70 percent at 15 centimetres above the soil surface in the extra tall stubble. This reduction in wind speed was a major factor for the increased water use efficiency with the increase in stubble height.”

as stubble height increased, the reduction of wind speed and solar energy near the soil surface contributed to the reduction of water evaporation. “We measured water evaporation using mini-lysimeters placed in the stubble and level with the soil surface,” explains Cutforth. “Water evaporation from the soil surface decreased as stubble height increased. Compared to cultivated stubble, tall stubble reduced evaporative water losses from the mini-lysimeters by more than 25 percent during the seedling stage, as well as at the maximum crop height stage.” These results implied that reducing the evaporation losses from the soil surface increased the amount of water available for transpiration by the crop and contributed to improved water use efficiency.

“although taller stubble reduces the wind speed near the soil surface, it also reduces the movement of the plants,” says Cutforth. “For plants, movement is another stress, and by reducing the movement, plants can divert more energy into seed production instead of strengthening

the stem to withstand the wind. a balance of stem strength and seed production is important, but this reduction in movement is another reason we think yields are increased under taller stubble heights.”

Cutforth and McConkey have continued this research, and over the past three years have direct seeded crops into canola stubble at various heights. “We are seeing similar effects as with cereal stubble, with the taller stubble having more advantages,” says Cutforth. “However, canola stubble is very brittle in the spring and breaks off much easier than cereal stubble, which is much more flexible and will often come back a bit after seeding. Comparing canola and cereal stubble with similar stand densities before seeding, we estimate that after seeding the stand density for canola stubble is only about 30 to 40 percent of the stand density for the cereal stubble. However, we are still seeing the benefits of taller canola stubble. In 2012, we plan to try the Smart Hitch technology to seed in between stubble rows and see how it works for cereal and canola stubble of various heights.”

overall, the research shows that increasing stubble height to at least 18-plus inches, or 45 centimetres, has a beneficial effect on yield and water use efficiency of cereal, canola and pulse crops. Cutforth notes that some growers are using stripper headers at harvest and are leaving stubble as high as 70 to 90 centimetres in height. “Taller stubble heights are fairly easy to do with most harvest equipment; however, growers are reminded they can have a lot of problems in the spring if they haven’t planned ahead for seeding,” says Cutforth. “good residue management and proper opener selection to ensure good seed-soil contact are necessary to the success of direct seeding into standing stubble.”

“Every day I get to walk outside and see what we’re building. We can see our future when we step out our front door.”

– Jason Rider, Ontario

Canadian agriculture is a modern, vibrant and diverse industry, filled with forward-thinking people who love what they do. But for our industry to reach its full potential this has to be better understood by the general public and, most importantly, by our industry itself.

The story of Canadian agriculture is one of success, promise, challenge and determination. And the greatest storytellers are the 2.2 million Canadians who live it every day.

Be proud. Champion our industry.

Share your story, hear others and learn more at AgricultureMoreThanEver.ca

Call your crusher or retailer to make today’s most profitable hybrid canola decision. Field-to-field, growers are booking Nexera canola Roundup Ready® and Clearfield® hybrids. With leading agronomic performance and profitability, only Nexera canola hybrids help meet growing demand for heart-healthy Omega-9 Oils. To see the 2012 Field Trial results go to healthierprofits.ca.

by

Improving wheat will require a collaborative effort.

by Lorne McClinton

Wheat acreage has been dropping across north america as producers shift to corn, soybeans, canola and other more profitable crops. This trend will continue unless breeders find ways to boost yield and improve agronomic performance. While acreage is dropping, demand is rising.

rod Merryweather, the outgoing north american oilseeds business operations manager with Bayer, says global wheat demand is forecast to rise by 17 percent whereas supply will rise by only 10 percent. Canada should be able to remain a strong competitor on the world wheat market, Merryweather says, as we have the third lowest cost of production in the world (after russia and the Ukraine). However, it would be a mistake to sit back and rest on our laurels while facing heavy competition from breeders around the world.

“Canada is falling behind in wheat breeding research,” says garth patterson, executive director of the Western grains research Foundation. “australia is investing up to $80 million a year in wheat variety development and Canada is averaging around $20 million a year [WgrF and aaFC]. We conclude from these numbers that we are under-investing in wheat.”

Investment dollars are driven by profits, and private industry has

found it much more lucrative to invest in corn, soybeans and oilseeds. patterson says that US wheat breeding programs received about $50 million dollars of funding annually whereas over $680 million is invested in corn and $340 million is spent on soybeans. Canola breeding programs in Canada receive $80 million in funding, four times the money that’s spent on wheat.

Investment dollars are driven by profits, and private industry has found it much more lucrative to invest in corn, soybeans and oilseeds. patterson says that US wheat breeding programs received about $50 million dollars of funding annually whereas over $680 million is invested in corn and $340 million is spent on soybeans. Canola breeding programs in Canada receive $80 million in funding, four times the money that’s spent on wheat.

This trend is driven partly by changes in consumption patterns globally, says patterson. United nations Food and agriculture organization statistics show that global demand for vegetable oils, meat and dairy products is growing at much higher rates than is wheat demand.

ABOVE: Canada needs to put a renewed collaborative effort into wheat breeding programs to remain competitive.

Pod for pod, Cargill Specialty Canola will make you more money. Cargill

Choose Cargill Specialty Canola for premier, high-yielding hybrids — from VICTORY® and InVigor ® Health — that generate unparalleled profits. And enjoy the convenience of a simple program that saves you time and hassle. Want the proof? Go to cargillspecialtycanola.com.

® The Cargill logo, VICTORY and VICTORY Hybrid Canola logo are registered trademarks of Cargill Incorporated, used under license.

InVigor® is a registered trademark of the Bayer Group.

Genuity®, Genuity and Design®, Genuity Icons, Roundup Ready®, and Roundup® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC, used under license. Always follow grain marketing and all other stewardship practices and pesticide label directions. Details of these requirements can be found in the Trait Stewardship Responsibilities Notice to Farmers printed in this publication. ©2012 Cargill, Incorporated. All rights reserved.

www.victorycanola.com www.cargill.com

However, producers in Western Canada still have to be able to grow cereals, oilseeds and pulse crops at a profit in order to have a sustainable crop rotation.

“Crop rotation is a three- or four-legged stool,” patterson says. “We need oilseeds, cereals, pulses and other special crops all to be profitable for producers; otherwise, we get skews in the rotation that can affect our long-term sustainability. I think we need to increase investments in wheat breeding to $80 to 100 million annually. probably the only way to do this is through public, producer, private partnerships.” exactly how such a future would work is still being worked out. patterson says the partnerships have to be structured in such a way that all parties are winners. If past performances are anything to go by, there is reason for optimism.

about 50 percent of the genetic progress in wheat internationally is due to germplasm exchange, says Curtis pozniak with the Crop Development Centre at the University of Saskatchewan. Canada has put a tremendous amount of effort into breeding high-quality wheat for bread, pasta and cookies, and co-operation among local and international breeders has been key to successful releases of new varieties. although institutions have dominated wheat breeding for over a century, Merryweather says private companies such as Bayer CropScience are becoming interested too. Developing and marketing oilseed traits and varieties have been very profitable activities for Bayer and the company is hoping it can duplicate this success by developing them with cereals too. That’s why the company is preparing to invest billions of dollars in the coming years to set up a wheat-breeding program. The company now has breeding stations in the United States, australia and the european Union, and hopes to have a new

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. This product has been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from this product can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for this product. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready® crops contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate. Genuity and Design®, Genuity Icons, Genuity®, Roundup Ready®, and Roundup® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC. Used under license.

one soon in Saskatoon.

Collaboration and synergies between government and universities have been key elements of past plant breeding successes, says gilles Saindon, director general of agriculture and agri-Food Canada’s (aaFC) Science Centres Directorate. However, in the last 15 to 20 years, there have been more and more interaction and synergies within the private sector. aaFC brings a lot of infrastructure to the table, with major breeding facilities in Swift Current, Winnipeg, Lethbridge and ottawa. It also has made strategic investments, like the just completed level three bio-containment facilities at Morden, Manitoba, and a second one being developed jointly with the Canadian Food Inspection agency in ottawa.

“We all have to also look for ways to work together and collaborate to enhance both wheat quality and yields to be competitive in the marketplace on a long-term basis,” Merryweather says. “That means that public and private breeders have to work together to develop the pool of research that will be needed to produce competitive varieties and hopefully someday hybrids too.”

Bayer started its wheat project about two years ago and the company now has a number of agreements in place to develop cereal technology. For example, it has agreements with australian growers organizations to collaborate with them on their research projects to develop and introduce traits into the global marketplace.

“You need a wheat breeding program to have the foundation to introduce traits and features into wheat,” Merryweather says. “We believe developing traits are going to deliver tremendous value to wheat. They’ll increase yields and improve nitrogen use efficiency and drought stress tolerance.”

part of the newfound excitement for developing new wheat varieties lies in the availability of new breeding tools. Canada has become part of an international effort to sequence the wheat genome. It’s believed that once researchers know all the genes that are found in wheat they will be able to decipher which genes or groups of genes are responsible for producing the traits breeders are targeting for selection. once the project has reached that stage, it should be straightforward to establish marker-assisted breeding programs.

“The wheat genome is quite large; there’s 21 chromosomes that we need to tackle,” says pozniak. “Canadian researchers are focusing their efforts on chromosome 6D. We chose that chromosome because there are a number of unused quality traits that reside on that chromosome as well as disease-resistant genes that are unique to Canadian germplasm, and we’re interested in sequencing those to see how they work.”

“germplasm development and maintenance is and will remain a core function of the research branch,” Saindon says.

Disease resistance and quality is something that researchers at aaFC have to keep an eye on because there’s always a new bug or a new strain that comes in, explains Saindon. partnership will be critical because wheat germplasm development is so complicated that it requires a lot of multidisciplinary teams, from an alliance of private, public and private science providers.

If public and private wheat breeders are successful at duplicating the rapid ongoing performance improvements found in canola production, it will have a major impact on wheat seed production, Merryweather says. a local seed production processing system will be needed to meet the volume that is required for cereals. In addition, seed production acreage will have to increase by 600 percent to meet the increased demand.

Canada has a great wheat quality control because it’s responsive.

by John Dietz

Some things will change, but prairie farmers can expect the grading structure to remain in place for controlling wheat quality in 2013 and onwards, says randy Dennis, chief grain inspector for Canada for the Canadian grain Commission (CgC).

Canada’s quality control – through regulation, inspection and grading – already is very good and customers are very confident in purchasing Canadian grains, oilseeds and pulses, according to the chief inspector.

“The systems we have in place now – for grading – will not change in the short term; however, we are prepared to adapt to industry needs,” says Dennis. “The end use functionality of #1 CW red Spring wheat or amber Durum or a particular class of barley is not changing because the Wheat Board has changed. The way that varieties are developed and the way we grade grain which is ultimately being processed are also not changing because of the Wheat Board.”

However, an internal review is underway. Some structural changes will be made in committees that make recommendation for changes to the grading and inspection system. Initial recommendations are expected in mid- october.

The chief inspector activated a mechanism for this through a review of the subcommittee composition of the Western Standards Committee (WSC) about a month before the Marketing Freedom act took effect.

The Canada grain act describes the composition of the WSC. There are about 25 members, which include the chief inspector, chief commissioner, grain research Laboratory director, the Canadian Wheat Board, plus producer organizations, grain handlers and other industry stakeholders.

as well, about 10 years ago four subcommittees were created (wheat, barley and other cereal grains, oilseeds and pulses) to serve the WSC. each one has a CgC scientist, CgC inspector and industry specialists.

“We have Wheat Board members on both our wheat and barley subcommittees. We are reviewing these positions and all others, to make sure we’ve got the right composition,” says Dennis.

The review notification, posted by the chief inspector to the members of all four subcommittees and the organizations they represent,

The Canadian Grain Commission assesses how new durum lines will perform when used to make spaghetti. Results are shared with the Prairie Grain Development Committee to determine if a new variety should be recommended for registration.

was meant to inform them that the CgC was conducting a review of the subcommittees to “make sure” the right organizations are represented at the subcommittee tables.

This will also be a time to review more than CWB membership. In the past few years, grain industry amalgamations have taken place, associations have developed and even products have changed. The

status of these, too, is up for review.

The subcommittees meet in mid- october and March and send recommendations to the WSC. In turn, the WSC meets in early november and april. The purpose of the subcommittees is to make recommendations to the grain Commission for changes they want. Usually, those are in the form of suggested changes to grading specifications and requests for scientific studies.

During the review process for the Marketing Freedom act, the CgC also heard requests for other types of changes.

“We certainly heard from some organizations and companies that the varietal development process is too cumbersome, takes too long to get varieties developed and registered for Canadian producers. That has certainly been discussed in the grain industry,” Dennis says.

The CgC itself is entertaining ideas for changes as well, the chief inspector says, but these would require changes to the CgC act.

earlier this year, the CgC sent an engagement letter to all industry and producer stakeholders, asking for their feedback on possible changes to the Canada grain act.

as an example, the act imposes a fee to grain companies when they ship grain from a primary elevator to their own terminal elevator. They must pay to have it officially inspected and weighed at the terminal, even though it’s their own grain.

“The industry has changed significantly, and this is a cost to the industry that is not necessary anymore,” Dennis says. “Most stakeholders we heard from supported this elimination.”

another issue, internally, is that the fees the CgC charges for service are written into the CgC act and frozen. They last changed in the 1990s. Twice in the past five years, government-proposed changes to the CgC act have failed passage.

In the big international perspective, as a major grain producer and exporter, the chief inspector says, “Canada has the best system in the world. I say that for several reasons. one, we’re very open in what we do and, we directly involve all elements of the industry in the system that sets the standards.”

“Two, we have a very sound grading system in place (and) backed up by the prairie grade Development Committee’s broad reg-

istration process.” any country that exports wheat or other grains needs some quality control, and it needs to work for their particular needs. In Canada, the needs of overseas markets play a major role but those are balanced against uniquely Canadian needs.

“We try to understand, when Canadian grain is used overseas, how it’s used. We get some of that intelligence when meeting with customers at home and abroad and through exporters, CIgI, the Wheat Board and other organizations,” says Dennis.

“We also try to take into account all aspects of the industry – whether it’s a particular grading factor or a technology we’re considering – such as modification of a grading factor, or changing the percentage allowance for a factor such as sprouted wheat.

“We truly take that to heart when changes are brought forward and deliberations take place. That’s very important, and something we’re quite proud of,” he says.

Land Pride Pasture Aerators aide in conservation tillage and pasture renovations. The heavy-duty tines are designed with a twist to lift while fracturing the compacted soil sideways.

This allows the soil to soak up run off water faster, allows fertilizer to penetrate deeper into the ground, and increases oxygen supply to the plant roots. Get Dirt Work Done...with Land Pride’s Pasture Aerators.

Over 250 Products s to Fit Your r Lifest yle…

Sclerotinia is an expensive disease, costing Western Canada canola growers millions of dollars of lost revenue each year.

Now there’s a revolutionary way to limit these losses: Pioneer Protector® Sclerotinia Resistance* – the first and only sclerotinia resistant trait on the market. It puts your first line of defense against this costly disease right in the seed, to help protect your yield potential through to harvest.

Control sclerotinia from the ground up. With Pioneer Protector Sclerotinia Resistance. www.pioneer.com

An old-world gene giving modern varieties a better ability to cope with too much salt.

by John Dietz

Ageneration from now, or maybe sooner, prairie grain producers are likely to be planting wheat, corn, soybeans, canola, and perhaps other crops with salt-tolerant characteristics, while looking back at March 2012 as historic for the introduction of the first salt-tolerant durum wheat – in australia.

It won’t be a genetically modified crop in the case of wheat and durum at least, because the gene making it possible was in the ancestral gene pool. It already existed, waiting to be discovered. and, growers may be seeing other new crop traits using other genes that were unknown to 20th-century breeding programs.

“It was some pretty big thinking about 15 years ago by our collaborators at CSI ro – r ana Munns and richard James – that started this work,” says Dr. Matthew g illiham of the University of adelaide and the arC Centre for p lant e nergy Biology. “a s a result, we have shown a 25 percent yield increase with this line of durum.”

g illiham is senior author on a paper published in nature

Biotechnology in March 2012 announcing the development of salt-tolerant durum wheat that is ready for commercial farming.

“a s well, we have proven that salinity tolerance can be improved in cereals in general by improving the ability to exclude salts from the shoots,” he says. “If similar gains can be made in other plant varieties, it will go a long way to reducing the threat of a global food crisis by 2050.”

Salinity affects more than 20 percent of the world’s agricultural land. Western Canada is not immune. according to a griculture Canada, nine percent of prairie farmland in 2006 was at moderate to very high risk of salinity. (Thanks to improved farming practices during the previous 25 years, the quantity of land at risk of salinity was nearly cut in half.)

Four salts dominate in prairie soils: ions of calcium, magne -

VT 500 G canola takes maximum nitrogen rates without lodging. This unique trait allows farmers to maximize fertility with confidence. Get the yield you’re looking for and swath it faster with VT 500 G.

sium, sodium and sulphate. The salt tolerance gene now effective in the new durum counteracts the sodium ion in particular. Durum is one of the more sensitive crops. At a low level, salinity is likely to trigger up to a 50 percent yield loss in such crops as beans, peas, corn, soybeans, sunflowers, clovers and timothy. At a moderate level, salinity can trigger 50 percent losses in canola, flax, oats, wheat, rye, barley, bromegrass, alfalfa, sweet clover and trefoil, according to a Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives publication.

What’s more, salinity levels are often patchy within fields. They can vary with the topography, groundwater levels, moisture conditions and other factors. This particular salt-tolerance gene, however, counteracts only the toxicity aspect of high-so-

Our eventual aim is to pyramid tolerance to the salt stress together with this osmotic tolerance

dium conditions that slash crop production in Australia.

“There’s much more than just toxicity to salt,” Gilliham says. “There’s also the osmotic component associated with drought, and we have not solved that. That’s what we want to work on now, if we get more funding.”

As soils dry during a drought, natural salt concentrations increase. When the level of salt in soil nutrient solution exceeds that in adjacent plant tissue, the plants find it difficult to extract water from the soil. Gradually, the plant, or crop, will dehydrate. The two processes, salt toxicity and osmotic stress, can occur together and combined have an even more dramatic effect on yield.

The Australian group has begun searching for other ancestral gene traits that might counteract the effect of both salt toxicity and osmotic stress. According to Gilliham, both his group and his collaborators at CSIRO have promising leads for this in current breeding programs.

“Our eventual aim is to pyramid tolerance to the salt stress together with this osmotic tolerance so we can improve yield even further under saline soil conditions. That result will be gold,” he says.

The search for genetic “gold” is measured in years and decades.

BIt’s been two decades since Rana Munns at CSIRO first found one line of wheat that performed much better in saline soil than any other line. However, it took until this year, aided by significant technological developments, to discover the reason it performed so much better. Gilliham’s group found that the durum contained an ancestral salt-tolerant gene (TmHKT1;5-A) from the first domesticated grain-bearing grasses in central Turkey, Triticum monococcum, dating back about 5,000 years.

The function of this gene, they discovered, is to transport and store within the root structure most of the salt that the plant encounters.

Through the process of domestication and breeding selection – for improved yield in ideal conditions – somehow this gene was lost from the genome of modern wheat. It means that when modern wheat takes up salt from the soil it accumulates salt in the shoots, stems and leaves. When concentrated in shoot tissue, salts shut down plant metabolism. Munns’ group used conventional plant breeding to import that salt-tolerance gene into a modern durum. They proved its effectiveness, saw yield increases immediately without any setbacks to other characteristics, and showed that, in soil without a salinity issue, the gene did not depress yield.

Bread wheat was less sensitive to salinity, but also responded when the Australians placed the same salt transport gene into an existing variety.

“It was a bit of a surprise,” Gilliham says. “This transport gene seems to complement a gene already present in bread wheat and increase the capacity of bread wheat to perform on salty soil. And, there appears to be no yield penalty, either on salty or non-salty soils.”

When it was satisfied that the genetics were proven for the salt-tolerance gene for wheat, CSIRO decided to release the gene for public use without a royalty.

Since that news broke in March, Gilliham says, the gene stock has been requested by plant breeders in countries all around the world including France, Ukraine, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and China.

“The seed is available now through CSIRO, for distribution under an MTA, so publicly funded agencies and labs can continue to develop locally adapted salt-tolerant wheat varieties.”

Now that the door has opened to the possibility of improving salt tolerance with existing genetic material, he says, there is a possibility for investigating salt-tolerance improvements for corn and for canola.

e cautious about applying to Western Canada any claim of large yield increases from the other side of the planet, says Dr. Brian Rossnagel, emeritus professor at the Crop Development Centre, Saskatoon.

“I have serious doubts,” Rossnagel says in relation to the claims for salt tolerance coming from Australia’s CSIRO. “I suspect that they’re going to find, when they get those types of materials into more realistic situations, they may still have a positive effect but it will be so small that it won’t be worth the effort.”

Rossnagel raises two concerns: the baseline for improved yields and the differences in kinds of salinity.

If the yield of normal crops in the salinity testing is extremely low, a 25 percent increase might be attractive in Africa but far below any economic threshold for Western Canada, he suggests.

Secondly, he says, “They deal with an entirely different set of salts. We don’t have to deal with that sodium issue (although) we do have salt-induced drought stress.”

Rossnagel adds: “There’s no free lunch out there. The lab work they’re doing is very good; hopefully they will come up with something that really does make a difference.”

by Carolyn King

The spread of fusarium head blight (FHB) is a serious concern for Prairie cereal growers. A team of researchers with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada recently investigated whether fungicidal seed treatments of Fusarium -infected seed might help improve crop performance and prevent or reduce the spread of this potentially devastating disease.

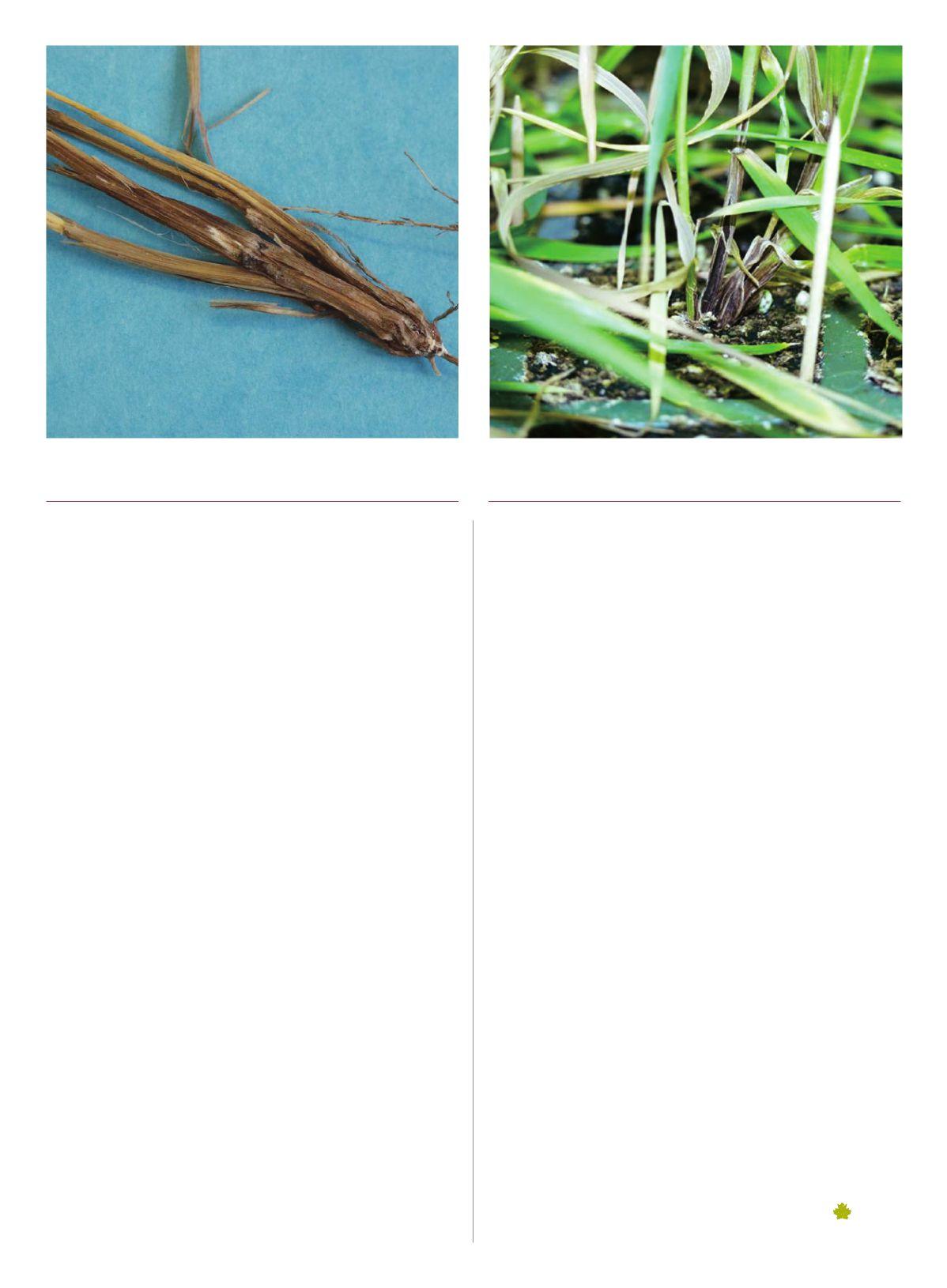

FHB is a difficult-to-control disease of cereal crops. It reduces grain yield and grade, and can produce toxins that limit the grain’s end-use. The fungal pathogen Fusarium graminearum is the major cause of FHB in Canada, but the disease can be caused by several other Fusarium species. The pathogens thrive in warm, moist conditions.

In Western Canada, FHB first appeared in Manitoba. In that province, localized outbreaks of FHB started in the mid-1980s and the first major outbreak occurred in 1993. Since then the disease has gradually spread westward, especially in years with above-average moisture.

“When FHB started to spread from Manitoba into Saskatchewan in the late 1990s to early 2000s, producers in affected areas were concerned about planting infected seed. F. graminearum -infection can reduce germination, plant emergence and yield. For cereal-growing areas of the western Prairies that were free of the most important FHB pathogen, there was also concern that infected seed brought into the region might help establish this pathogen. The infected plant tissue might result in crop residues on which reproductive structures of the pathogen can form in subsequent growing seasons,” explains Dr. Myriam Fernandez, a plant pathologist at Swift Current.

“At that time, we started to receive inquiries from producers asking about seed treatments to control the spread of FHB. We were also interested ourselves in determining the actual effectiveness of products in the market, and wanted to make sure that any recommendation we provided was accurate and reflected results obtained in actual field experiments, with appropriate controls, and so on.”

Fernandez worked on this research with Bill May, a cereal management agronomist, and Dr. Guy Lafond, a production system agronomist, both at Indian Head, and Dr. Kelly Turkington, a barley pathologist at Lacombe.

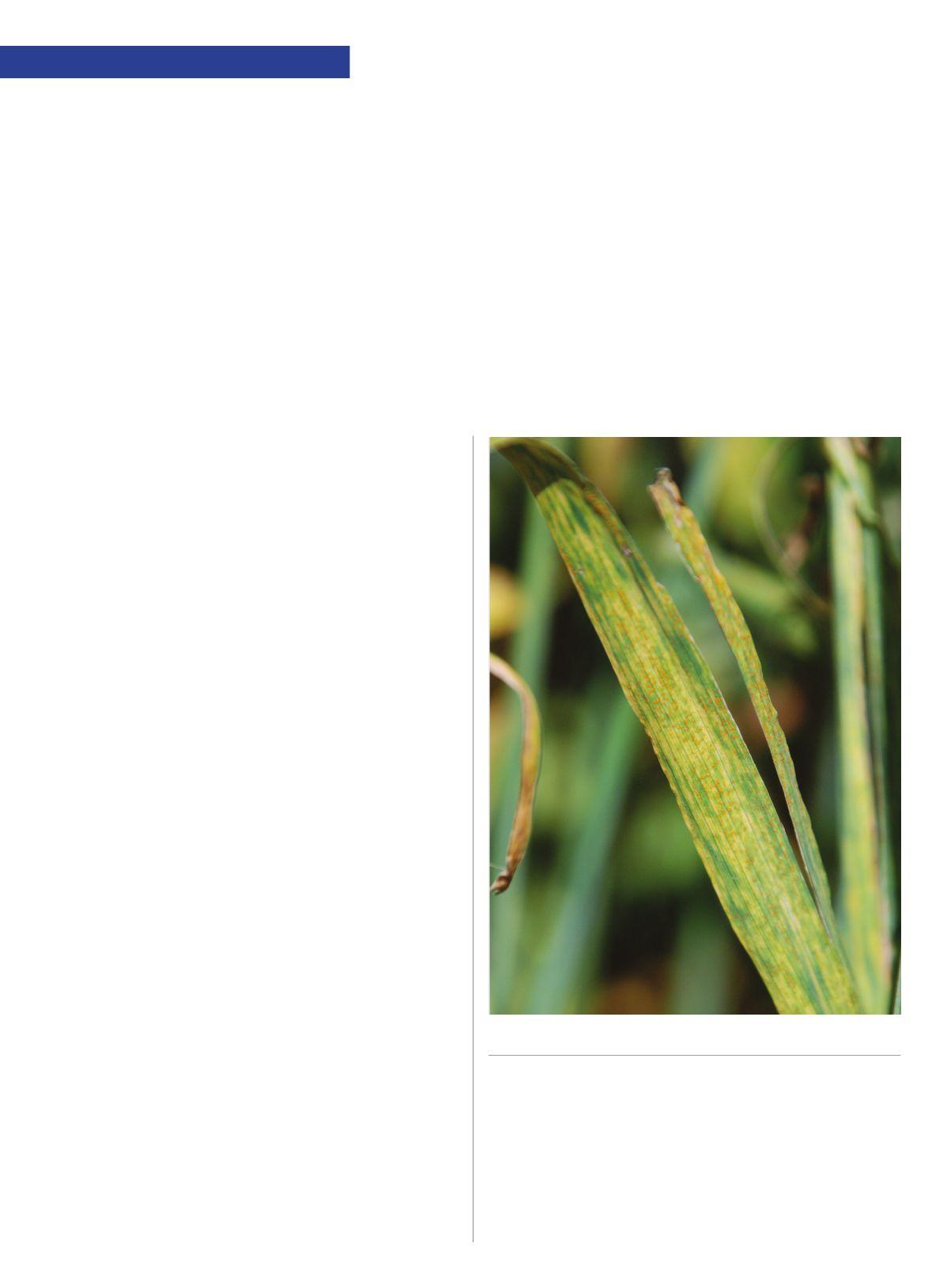

The Fusarium pathogen can cause diseases like root and crown rot in wheat seedlings.

The researchers’ study objectives were to determine the effectiveness of fungicidal seed treatments in preventing the growth and spread of Fusarium graminearum from infected seeds to seedlings, and to see if the seed treatments could improve emergence, development, yield and quality of crops grown from infected seedlots.

They carried out an initial greenhouse study and then conducted field trials involving common wheat, durum wheat and barley, the three crops most affected by FHB in Saskatchewan. The trials ran from 2003 to 2005 and were conducted at four sites in eastern Saskatchewan: Canora, Indian Head, Sintaluta and Redvers. The Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund provided funding for the study.

The seed treatments used in the study included all the currently registered fungicidal products and some experimental ones, as well as some combinations of products. Most of the infected seedlots had low levels (five to 10 percent) or moderate

Experience the complete picture with WR859 CL

You won’t miss a single detail when you choose WR859 CL. You’ll get higher protein, excellent yield and a very strong disease resistance package including the best rating for Fusarium head blight resistance available in a CWRS wheat variety. WR859 CL is only available at your Richardson Pioneer Ag Business Centre.

PIONEER® FOR THE SALE AND DISTRIBUTION OF SEED IS A REGISTERED TRADE-MARK OF PIONEER HI-BRED INTERNATIONAL, INC. AND IS USED UNDER LICENSE BY THE UNAFFILIATED COMPANY RICHARDSON PIONEER LIMITED.

Always read and follow label directions. The Syngenta logo is a trademark of a

levels (25 to 35 percent) of infection, but one seedlot had a high infection level (63 percent). Based on germination tests, seeding rates were adjusted to aim for a target plant density of 200 plants per square metre for all seedlots.

Unfortunately, none of the fungicidal treatments consistently improved crop performance or consistently reduced the growth and spread of the pathogen.

“We found that, compared to the untreated infected control, the combined seed treatments reduced root rot in plants derived from infected seeds, but no single fungicide reduced root rot consistently across site-years or crops. Similarly, although some fungicides appeared to be more effective than others, no product consistently reduced the occurrence and growth of Fusarium graminearum or other Fusarium pathogens,” Fernandez says.

“o ur observations from the field trials agreed with results from the controlled-environment study, thus confirming that treatment of F. graminearum -infected seed with fungicides will not likely prevent the spread of this pathogen.

“We also determined that, while currently registered seed treatments might be effective in improving seedling emergence in some infected seedlots and environments, they did not consistently improve the agronomic performance of F. graminearum -infected common wheat, durum wheat or barley seed in eastern Saskatchewan.”

adjusting the seeding rate based on germination tests did maintain grain yields for the crops grown from infected seedlots, except for the seedlot with the highest infection level. This indicates that, if a plant from an infected seed survives germination and emergence, it should grow and produce grain similar to plants from uninfected seeds.

Fernandez also points out, “Some of the seed treatments used in our study are registered for control of other diseases, such as loose smut and common bunt, but these diseases were not examined in our study.”

In the greenhouse experiments, Fusarium -infected seeds transmitted the pathogen to their seedlings.

Fernandez has several recommendations for growers who may be dealing with Fusarium -infected seed. She advises having the seeds analyzed at an accredited lab to identify which Fusarium species are infecting the seed.

“The main species to worry about is F. graminearum. other common FHB pathogens in Saskatchewan, such as F. avenaceum, are very common in our soils and in roots of a wide variety of field crops, and so seeds infected with this pathogen are not of concern, unless high infection levels might affect the performance of the crop.”

a s well, growers should have the lab determine the percent infection of the seeds. a germination test will also give a good indication of high infection levels.

Fernandez notes, “ g iven that the greatest risk of introducing F. graminearum into a field is by purchasing seed from an area and a year with high levels of FHB, a lab certificate with proper fungal identification should be requested in those situations.”

She adds, “It’s important to remember that the seed could be infected without showing any symptoms.”

Based on the study results, fungicidal seed treatments are not recommended as a best management practice to improve Fusarium -infected seedlots.

In areas where FHB has not occurred so far, the recommended practice is to avoid planting F. graminearum -infected seed.

In fields that have had FHB in the past, growers who choose to plant infected seed should increase their seeding rates to compensate for lower germination rates and lower seedling vigour.

Fernandez reminds growers in regions at risk of FHB development to use agronomic practices recommended for the reduction or control of this disease, most importantly to choose cereal varieties with some resistance (e.g., “good” or “Fair” for FHB in Saskatchewan agriculture’s Varieties of Grain Crops).

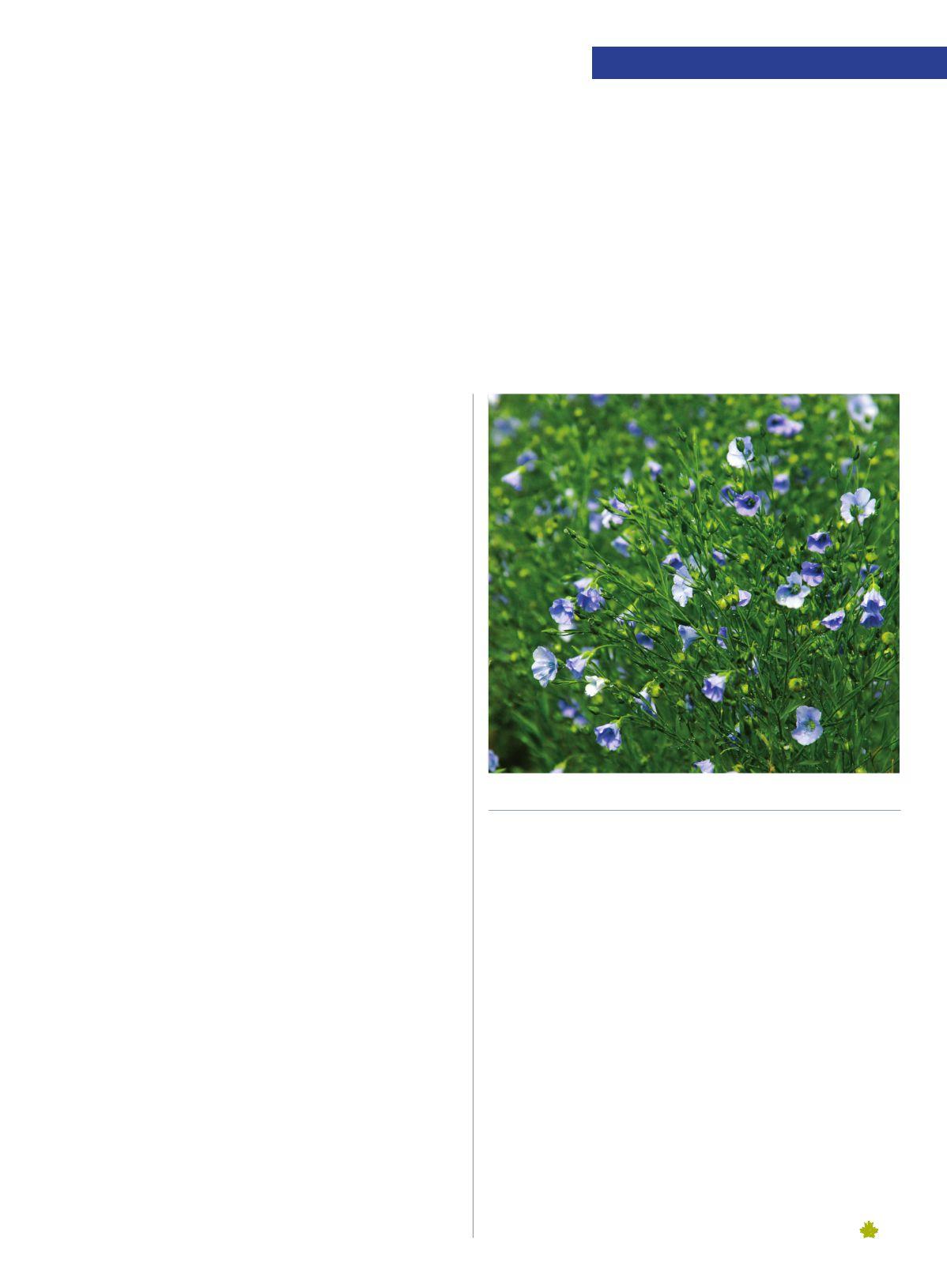

Finding new, high-value uses for Canadian flax that was ravaged by AC Triffid gene.

by Lorne McClinton

Canadian flax producers were dealt a devastating blow when european Union inspectors discovered that genes from aC Triffid, an unlicensed genetically modified flax variety, had contaminated a significant percentage of the country’s production. Flax production in Canada still hasn’t recovered from the blow to its reputation.

The aC Triffid issue cost Canada its position as the world’s pre-eminent linseed producer and supplier. Farmers in russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan have stepped in and ramped up their flax acres to meet the global shortfall. Because these countries have a lower cost of production and are much closer to end users, the Canadian industry will be challenged to recover the lost european Union market. producers, though, can take heart in the work of researchers who are busy developing new, high-value uses for Canadian flax. Most of the Canadian flax crop is grown for its oil content but much of the new research is focusing on innovative ways to utilize its fibres and shive. Jeremy Lang, with open Mind Developments (oMD), for example, has developed a way to use flax fibres and shive to create eco-friendly bio-plastics. The company’s first product to hit the marketplace is the peLa case, a hard, protective plastic case for the apple iphone 4S. oMD sells its case for $34.95 on its website (pelacase.com) and it’s also available in Saskatchewan at Sasktel Corporate stores.

Bio-plastic is typically weak and looks like conventional plastic, says Lang. His idea is to combine naturally strong flax fibre and shive with bio-plastic to create stronger eco-friendly products. The products have a unique look and don’t resemble regular plastics at all. Making plastics from renewable resources such as flax fibre and shive offers many potential benefits, says Lang. Conventional plastic is made from non-renewable fossil fuels and comprises large molecules that don’t break down naturally in the environment. Lang says that almost every piece of plastic that has ever been made still exists today. Bio-plastics, on the other hand, are made from annually renewable non-food source plants and can be manufactured to be biodegradable and compostable.

Flax fibres have long been used to manufacture high quality papers. Joe Hogue, straw purchase manager for SWM Canada, says his company buys 90,000 tons of flax straw from Manitoba, Saskatchewan and north Dakota producers every year. However, the company is busy developing new flax straw products as well that use it for, among other things, components in fibreboard panels, fillers for plastics, premium horse bedding and biofuels. It is also being used in

an erosion control project overlooking the panama Canal. other uses include reinforcing strengthening structural auto parts components.

High-value new uses for linseed oil are being investigated as well. Martin reaney, Chair of Lipid Quality and Utilization at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) in Saskatoon, says that peptides, chemically stable circular molecules produced as a byproduct of flax oil production, have a lot of potential.

peptides are used as catalysts in the production of drugs and medicines, light-emitting dyes for flat panel displays and light-accepting dyes for solar cells. reaney’s group has developed technology to recover 1.6 kilograms of peptides from every ton of flax oil. This means there is the potential to produce 600,000 kilograms of peptides from the Canadian flax crop annually. Because closely related molecules, such as cyclodextrin and crown ether, can be worth more than $10,000 per kilogram this could provide a very valuable new use for flax.

reaney cautions that, although the technology to extract these molecules from flax exists in the proof of concept stage, it might still be some time before it reaches the marketplace. Currently reaney has set up a U of S spinoff company, called prairie Tide Chemicals (pTC), to perfect, commercialize and promote the process.

by John Dietz

Minimize the time the fans are running.

by John Dietz

Drying stored grain in the fall often is more expensive than it needs to be, says Joy agnew, project manager for ag research at the prairie agricultural Machinery Institute (paMI), Humboldt, Saskatchewan.

There’s no easy remedy today for typical bins under 5,000 bushels, but it could be coming soon due to some research at Humboldt.

The ag engineer recently completed a four-year study on ways to automate fans for natural air drying systems. The study began in 2007. agnew became project manager in 2009 and carried the study to completion. The study revealed much more than expected.

“We thought we knew everything because there was so much work on natural air drying in the 1980s and 1990s, but we identified trends that we couldn’t discount. everything is so complex that there’s still no one solution,” she says.

a lot of the advice today in this sector of ag technology is based on anecdotes rather than science. For example, the advice to “never turn your fans off because it will form a crust that affects airflow,” is incorrect.

“There’s actually no scientific evidence showing that’s what hap-

pens,” she says.

natural air drying systems are common, but they’re not efficient as operated on most farms. grain at the bottom of a bin can become too dry, actually reducing the market value to the farm. The only hours that a fan is contributing to drying (or cooling) grain in storage is when the air it is blowing has the capacity to dry or cool the grain.

“Half the time, air conditions are not conducive to drying or cooling,” she says.

The option of going to manual control, shutting fans off when the air isn’t able to actively dry the grain, and turning them on when the air is able to dry (or cool) involves a lot of guesswork.

“Standard practice is to turn the fans on and let them run continuously until the top of the grain is dry,” she says. “Since the air is pulled up from the bottom of the bin, the grain at the bottom will be overdry when the grain at the top is dry.”

“The potential to dry depends on the conditions of the ambient air.

Sign your NexeraTM canola production contract for a minimum of 500 acres before November 29th, 2012 –and get a $1,000 signing bonus.

Call your nearest Richardson Pioneer Ag Business Centre to make today’s most profitable hybrid canola decision. Field-to-field, growers are booking Nexera canola Roundup Ready® and Clearfield® hybrids. With leading agronomic performance and profitability, only Nexera canola hybrids help meet growing demand for heart healthy Omega-9 Oils.

It’s common for the fan to be running without achieving any drying action. And, manually, there’s no easy way to determine the in-grain moisture content and whether or not the air will result in drying.”

The PAMI researchers set out to develop a control system that will automatically turn fans on and off. They believe it is possible to have a ‘set it and forget it’ system that will prevent overdrying and shrinkage in the grain while reducing energy costs and greenhouse gas emissions.

To achieve that, they developed a program that would predict when the ambient air will adversely affect the grain and then turn off the fan before that happens. They also wanted the program to estimate the moisture profile in the stored grain, to allow more precise control.

“For example, if the grain at the bottom is overdry and the grain at the top is at a safe-to-store condition, the fan can be turned on when

the air has potential to wet in an attempt to rewet the overdry grain at the bottom.”

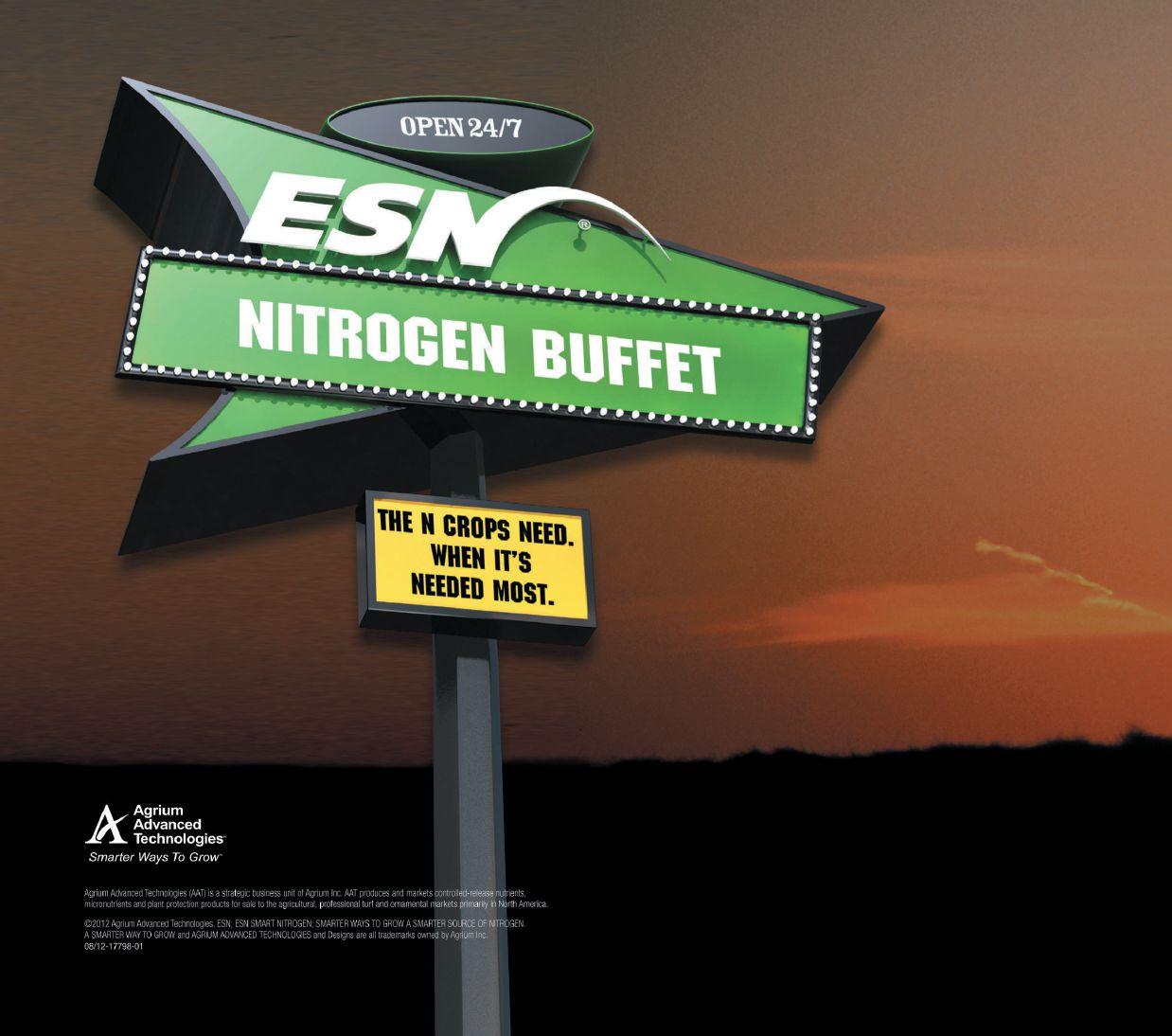

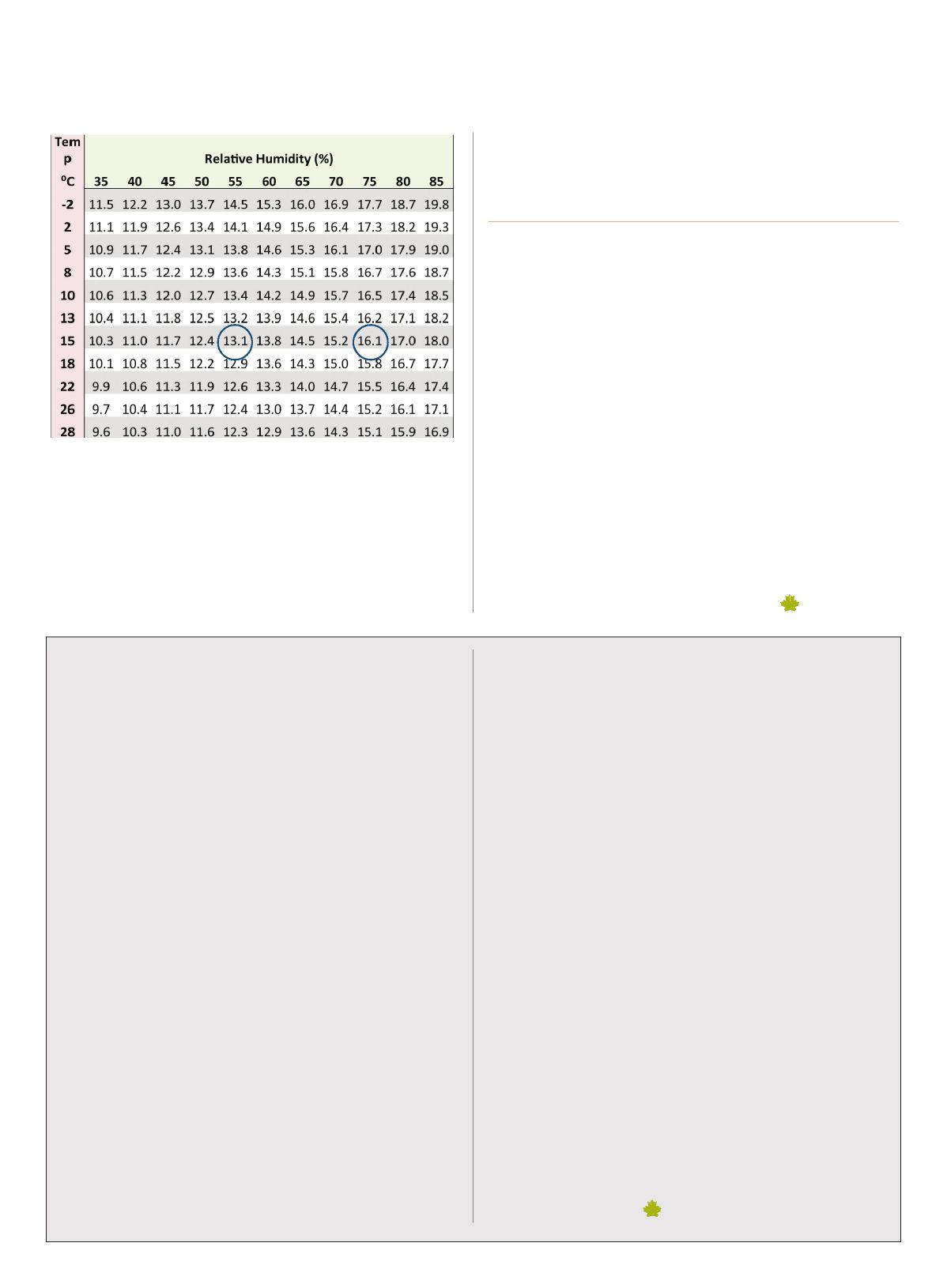

The PAMI team tested several formulas that attempt to define when ambient (natural) air is able to achieve drying, and found one that worked very well. Using this formula, they were able to develop “equilibrium moisture content” tables for canola, wheat and other grains.

At a given air temperature and humidity, moisture will move from the grain to the air or reverse and go into the grain. At equilibrium, the humidity in air in the voids between the grain kernels is equal to the moisture content of the grain.

For example: If you run air at 50 percent humidity and five degrees through canola, eventually the canola will reach a steady 8.1 percent moisture content – regardless of where it started – but in the same conditions, wheat will reach an equilibrium moisture at 13.1 percent moisture. (See the table.) The relationship is quite different due to the

This chart tells you which air conditions will have the “potential to dry”. It shows you the EMC of air for canola at a variety of temps and RH’s. It basically says that if you run air at 50% RH and 5 degrees through grain for a length of time, the grain will eventually equilibrate to 8.1% moisture content (whether the grain started at 6% or 11%...the grain will become 8.1%)

differences in oil and starch content.

“Drying capacity of air at a given temperature/humidity depends on the grain,” agnew says.

Finally, during fall 2011, the driest harvest in 10 years, the team ran full-scale trials with 2,200 bushels of wheat that arrived at 15.8 percent moisture. They used a three-horsepower fan and sensors to monitor moisture at three levels in the bin and put that into a data logger-controller for the fan.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 56

Tree fibre is becoming a potential cash crop.

by Tony Kryzanowski

Western Canadian farmers have grown up believing that trees are for shelterbelts or for bulldozing into windrows and burning because they occupy areas on farmland that could be planted into a cash crop. But times are changing.

With the arrival of the potential sale of carbon offsets, the willingness of forest industries to pay farmers to grow fast growing trees, governments wanting to improve their image by looking for ways to reduce their carbon footprint, and growth in the area of using woody biomass to produce bioenergy and bioproducts, growing trees for profit on good farmland has income potential under the right circumstances.

Short rotation woody crops can be used to produce electricity, wood pellets, heat, oriented strandboard panels for sheathing in building construction, pulp and paper, pharmaceuticals, chemicals like methanol, bio-plastics, and bio-fluids for use in industries such as oil.

and it’s not even that hard to do anymore because of support

organizations like the Canadian Wood Fibre Centre (CWFC). The CWFC, a division of FpInnovations, Canada’s forest product research institute, has accumulated a large database of knowledge over the past decade related to the planting, maintenance, and harvesting of short rotation woody crops.

So what type of cash crop is short-rotation woody biomass? The crop offers essentially two crop options when it comes to shortrotation woody biomass. The first is high-yield afforestation and the second is concentrated woody biomass.

High-yield afforestation is planting hybrid poplar or aspen on

TOP: A tree planter inserts a hybrid poplar cutting on land within visual range of the Al-Pac pulp mill near Boyle, Alberta.

INSET: Derek Sidders, CWFC regional co-ordinator for the Prairies, stands in a short-rotation willow plantation that exhibits only a few years of growth.

out how yours add up at clearfield.ca/canola

We’re not asking you to switch everything. But you do owe it to yourself to use the Clearfield Production System on some of your canola acres. In fact, we challenge you to compare it to your current system side-by-side. Because Clearfield may outperform what you’re using now in terms of profitability – by $25 more per acre according to field trials. With that in mind, this may not be much of a challenge for us at all.

non-forested lands at 1,600 stems per hectare, with yield objectives of more than 13.6 cubic metres of average biomass volume grown per hectare per year, calculated over the entire life of the plantation. The plantation grows on a 12- to 30-year rotation cycle.

Concentrated woody biomass is high-density planting of 14,000 to 20,000 stems per hectare of willow and hybrid poplar with yield objectives of six to 12 oven-dry tonnes ( o DT) per hectare per year. These are grown in parallel beds with threeto four-year harvest cycles and five to seven coppice cycles per root system.

“We have people that are using trees as an alternative cropping strategy,” says Tim Keddy, CWFC wood fibre development specialist. “What often happens when you are farming large areas is that everybody has a small piece that is not profitable to farm, and that’s where they establish a short-rotation woody crop. We recommend high-quality land because this is an expensive operation to establish and there is a fair amount of risk in dealing with a commodity of this type. The best land is the most profitable.”

The number of hectares needed as a starting point varies in each circumstance depending on the targeted end use for the raw material. CWFC can help businesses and landowners establish a minimum for each particular case.

In addition to selling large volumes of woody biomass, selling cuttings from existing trees to help other landowners establish plantations is another potential income stream for the landowner as part of the crop rotation.

So the question for landowners is where to market their product? Here are some options.

Landowners could market their products through custom growing agreements with forestry operations like a pulp and paper mill, an oriented strandboard plant, a bioenergy plant, or a bioproduct conversion facility such as a methanol plant. This typically applies to landowners within about a 160-kilometre radius of a plant, but that can vary depending on the value of the commodity being produced. alberta-pacific Forest Industries (al-pac) is a pulp mill operator near Boyle, alberta. It started its poplar plantation program in 1993 on both al-pac-owned land and leased land from area landowners. The company’s goal was to lease and plant an average of 1200 hectares each year over a 20 year period for a total of 25,000 hectares. about 10,000 hectares of leased land has been planted with hybrid poplar trees since the program began.

Last year the Manitoba government provided an additional $1.23 million to plant an extra one million trees.

Landowners can also plant short-rotation woody crops with the goal of selling carbon offsets. There are several carbon offset marketing agencies throughout north america. Carbon offset brokers work with landowners to market their offsets. also, large carbon emitters in alberta have the option of purchasing carbon offsets from landowners or paying a penalty to a pooled fund depending on how much carbon they emit above an established provincial benchmark. Derek Sidders, CWFC regional co-ordinator for the prairies, says the key to profiting on this market is to validate the amount of carbon offsetting that a short-rotation woody crop will generate over its lifetime.

CWFC has partnered with carbon sequestration experts at the Canadian Forest Service to develop models that will accurately predict how much carbon short-rotation woody crops planted on specific land bases, with specific soil types, under various growing conditions and with various management techniques throughout Canada will sequester above and below ground during the approximately 20-year growth cycle of that crop.

Landowners may also choose to become involved in government programs like the Manitoba government’s Trees for Tomorrow program, which is part of the province’s plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Launched in 2008, last year the Manitoba government provided an additional $1.23 million to plant an extra one million trees. as part of the program, the Trees for Tomorrow program could provide free seedlings, site preparation and tending of young trees, depending on the parcel of land and on the plan developed for the parcel.