TOP CROP MANAGER

Big help from a small grass PG. 12

WHEAT MIDGE CONTROL

A parasitic wasp may be the answer PG. 24

PREDICTING SCLEROTINIA

A new fast, effective test holds promise PG. 36

Big help from a small grass PG. 12

A parasitic wasp may be the answer PG. 24

A new fast, effective test holds promise PG. 36

Smart farmers read the fineprint:

For a canola crop you can be proud of, order your seed pre-treated with JumpStart inoculant to discover increased root growth and leaf area, and higher yield potential*. JumpStart. Quicker start, stronger finish. Over 20 million acres** can’t be wrong. is available on canola varieties from

*155 independent large-plot trials in Canada between 1994 and 2012 showed an average yield increase of 6%. Individual results may vary, and performance may vary from location to location and from year to year. This result may not be an indicator of results you may obtain as local growing, soil and weather conditions may vary. Growers should evaluate data from multiple locations and years whenever possible.

**Calculation based on net sales of JumpStart from 1997–2014. JumpStart ® is a trademark of Novozymes Biologicals Limited. Used under license.

6 | What is new in canola?

Top Crop Manager’s annual review of new hybrids. By Bruce Barker

14 New sources of clubroot resistance

By Carolyn King

36 Quickly predicting sclerotinia is closer to reality

By Madeleine Baerg

52 Determining important yield factors in canola

By Bruce Barker

PLANT BREEDING

12 Big help from a small grass?

By Carolyn King

PESTS AND DISEASES

24 Wheat midge predator control

By Madeleine Baerg

28 | Breeding for FHB resistance

Although FHB resistance is improving, it is not enough to control the disease.

By Donna Fleury

WEED MANAGEMENT

40 The Iowa pest resistance experience By Bruce Barker

FERTILITY AND NUTRIENTS

56 Comparing mid-row vs. in-row P placement By Bruce Barker

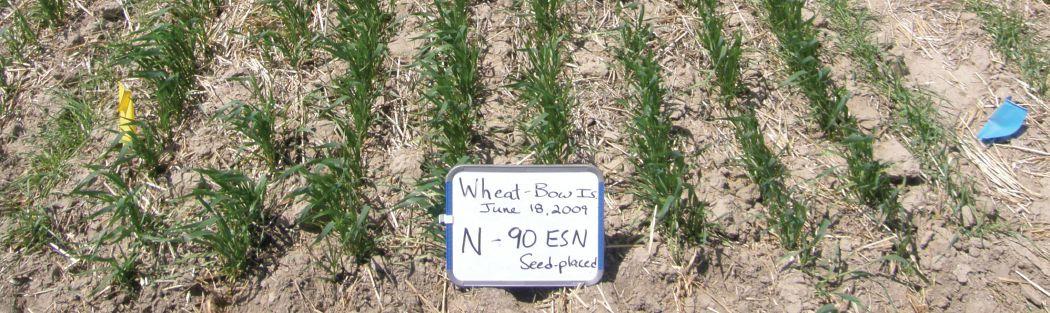

62 Determining safe rates of seed-placed fertilizer

By Ross H. McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag.

FLAX

60 Grow flax after wheat By Bruce Barker

CORRECTION

46 | Camelina Agronomy 101 Nebraska experience provides background for Western Canada growers.

By Bruce Barker

CROP MANAGEMENT

20 Agronomic management of soft and CPS wheat

By Ross H. McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag.

34 Straight combining canola evaluation By Donna Fleury

50 Wide row spacing can cut canola yield By Bruce Barker

FROM THE EDITOR

4 Sustainable agriculture: Is it working?

By Janet Kanters

October 2014 issue of TopCropManager , page 8: AAC Ryley is available from SeCan.

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

JANET KANTERS | EDITOR

The view towards sustainable agriculture in Canada today is that, well, everyone is contributing to it in some form or other: effectively managing soil and water resources, practising good crop rotation strategies, handling pesticide and fertilizer needs responsibly, improving animal welfare, to name just a few.

But if we’re doing so well, why are so many voices around the world still denouncing major agriculture practices as unsustainable? News stories, websites, Twitter and the like – people and organizations continue to cite the overuse of pesticides and herbicides, the overabundance of genetically modified organisms, the state of livestock housing systems, etc., as promoting unsustainable agriculture.

Increased public awareness of where our food comes from coupled with mass communication technology certainly contributes to this increase in negativity. But as we all know from watching A&W commercials and W5 episodes, some of the issues the public focuses on are simplistic and misguided, yet it continues to put even more pressure on the agri-food system to clean up its act.

In Canada, farm product production has greatly increased and intensified, and we have produced significant surpluses for export at steady or improving quality standards. Our practices have not caused starvation nor mass illness. Indeed, many farmers see themselves as stewards of the land, helping to solve the ever-increasing problem of nutrition deficiencies and the need for safe, reliable food in other countries as well as our own. Yet, concern about the future of the agri-food system continues.

The George Morris Centre recently released an interesting four-part series on sustainable agriculture entitled: Four Fallacies of Agricultural Sustainability, and Why They Matter. In it, they state that a gap has emerged in our understanding of how agri-food production systems develop and evolve, and how this relates to sustainability overall. “The purpose of this paper is to help develop the case for a more holistic and coherent view of agri-food sustainability as a process,” states senior research associate Al Mussell. You can access the four-part series here: www.georgemorris.org.

In late September, FAO director-general José Graziano da Silva addressed the issue of sustainable agriculture in his opening remarks to the 24th session of the Committee on Agriculture (COAG), held in Rome. He said policy makers should support a broad array of approaches to overhauling global food systems, making them healthier and more sustainable while acknowledging that “we cannot rely on an input intensive model to increase production and that the solutions of the past have shown their limits.” Calling for a “paradigm shift,” he said that today’s main challenges are to lower the use of agricultural inputs, especially water and chemicals, in order to put agriculture, forestry and fisheries on a more sustainable and productive long-term path.

Graziano da Silvo went on to say that options such as agro-ecology and climate-smart agriculture should be explored, and so should biotechnology and the use of genetically modified organisms, noting that food production needs to grow by 60 per cent by 2050 to meet the expected demand from an anticipated population of nine billion people. “We need to explore these alternatives using an inclusive approach based on science and evidences, not on ideologies,” as well as to “respect local characteristics and context,” he said.

While his words certainly resonate, the road to sustainable agriculture isn’t simply a matter of “if you build it, they will come.” Indeed, agriculture is fluid, always changing, as the seasons change, as the technologies change, as the farmers themselves change. We should learn to keep that in mind as we continue to strive toward sustainable agriculture at all levels.

As a farmer, you have a lot of decisions to make. The DEKALB® brand team is here to empower you with expert advice, agronomic insight and local data. With every important decision you face on your farm, we’re behind you. And we’re ready to help you turn great seed potential into actual in-field performance. DEKALB canola... Empowering Your Performance.

by Bruce Barker

Top Crop Manager has assembled a list of new varieties and hybrids that are being introduced in commercial quantities for the 2015 growing season. The respective seed companies provide the information, and growers are encouraged to look at third party trials, such as the Canola Council of Canada’s Canola Performance Trials, for further performance and agronomic information. Talk to local seed suppliers to see how new varieties also performed in local trials.

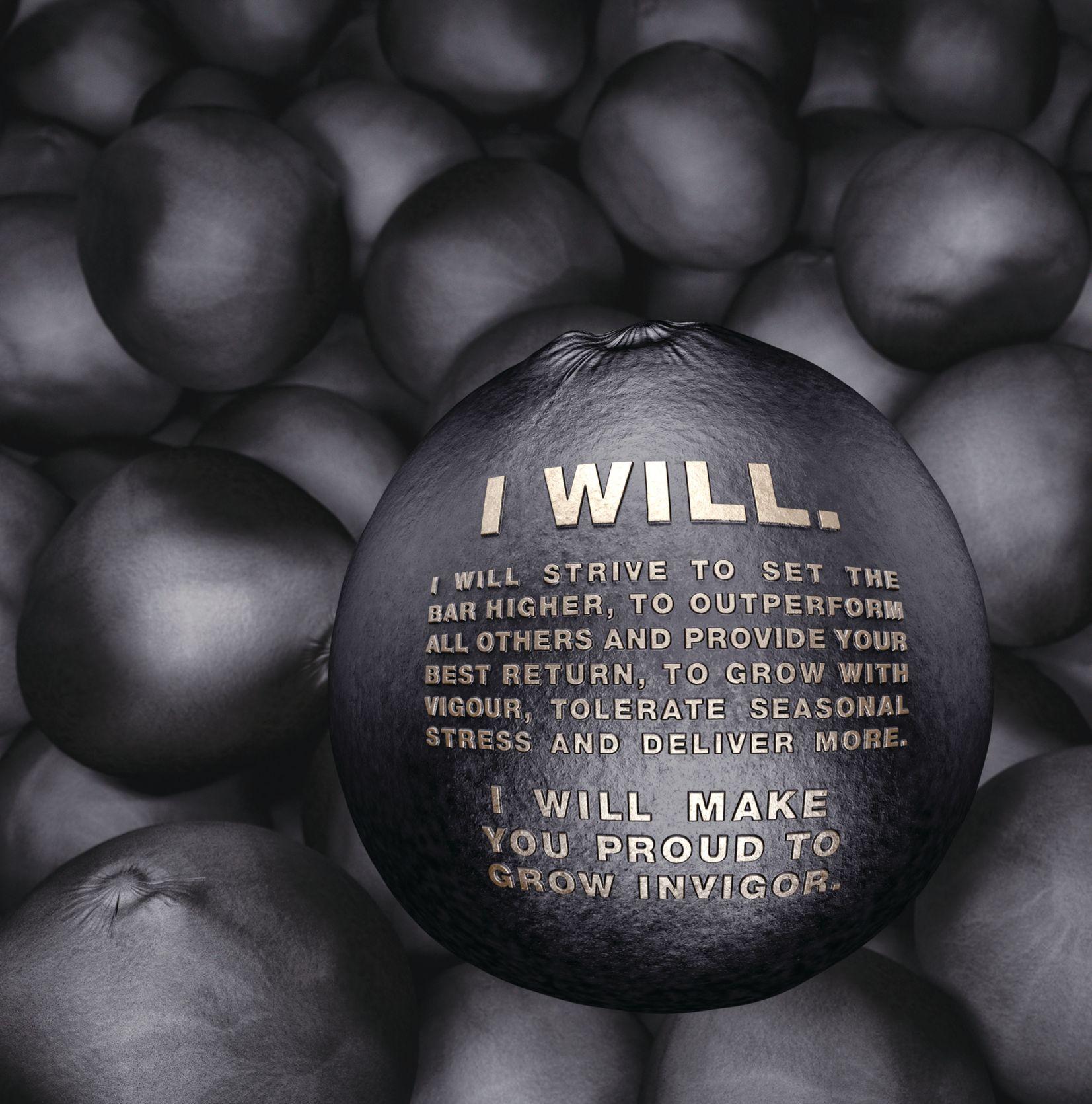

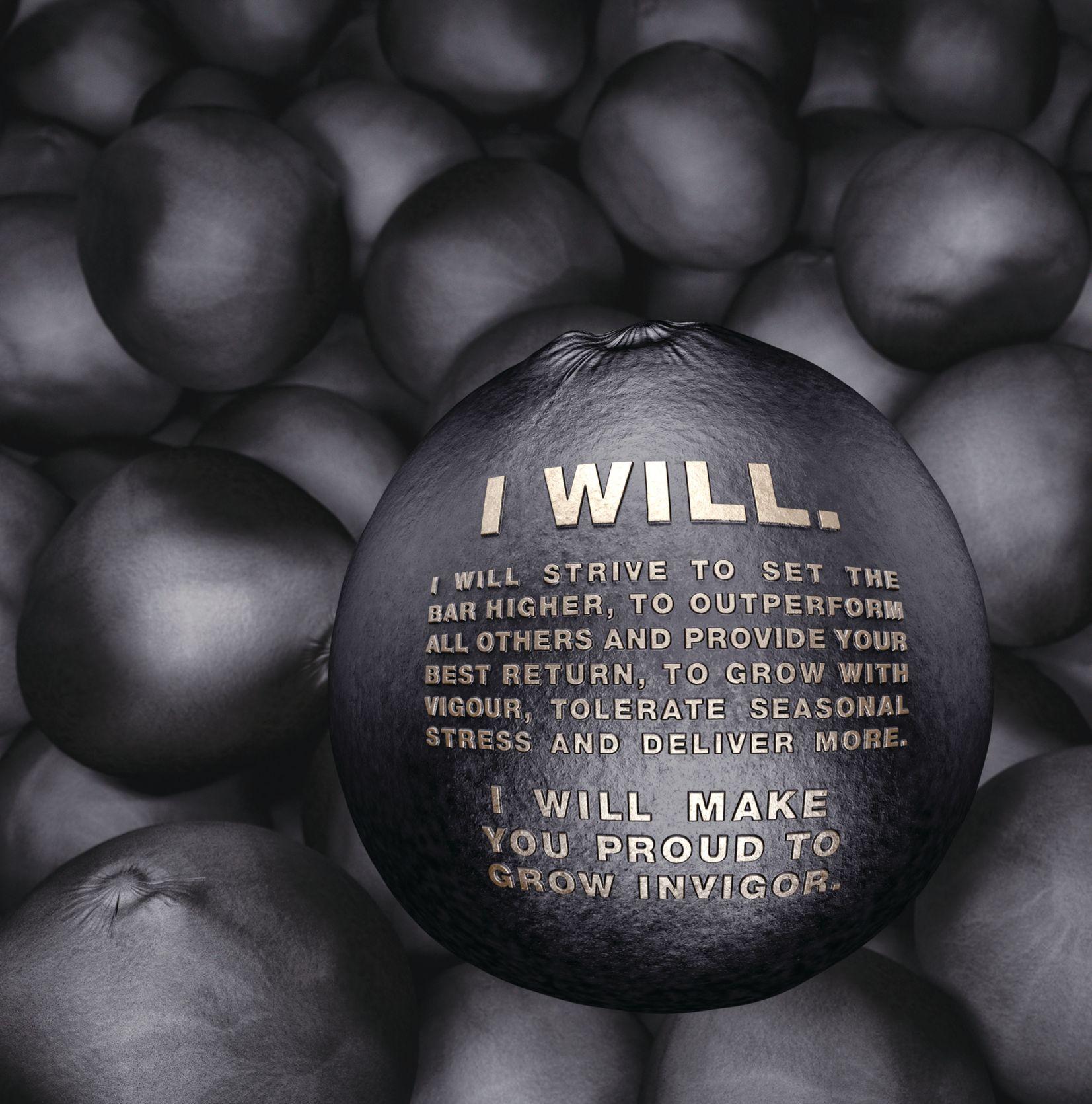

InVigor L140P, with patented pod shatter reduction technology, offers growers excellent yield protection with greater harvest flexibility. In the 2013 Bayer Demonstration Strip Trials, straight cut InVigor L140P showed a seven per cent yield advantage over InVigor 5440 at normal swath timing.

InVigor L160S is your first line of defense against sclerotinia with its innovative sclerotinia tolerant trait technology – without sacrificing yield. This hybrid combines excellent standability, enhanced blackleg resistance and all the benefits of the LibertyLink system.

BrettYoung

6064

nuity Roundup Ready portfolio. Superior standability and harvest results make it a top end performer. It is 0.7 days earlier than our 6060 RR. It is rated R for blackleg and came through the co-op trials with the equivalent of a 138 per cent index over 6060 RR’s 134 per cent. 6064 RR is available from BrettYoung retailers in 2015.

BrettYoung will open a new seed coating and treating facility in the fall of 2014. Located in Winnipeg, the facility features the latest equipment and process technologies to effectively apply treatments, nutrients and polymer coatings to their seed products. The plant will be fully computer controlled and automated from seed storage through to packaging, for high throughput yet precise control of the treatment process. The building, equipment and processes have also been designed to meet the latest standards for safe pesticide storage and application.

Cargill

New Victory V-Class V22-1 hybrid is a Genuity Roundup Ready canola hybrid that achieves yields of 110 per cent of Victory v2045 or 97 per cent of the new co-op checks 5440 and 45H29. R rating,

ABOVE: Companies continue to expand and improve hybrid canola choices with improved disease packages, shatter resistant canola and improved oil traits.

By Andrea Hilderman

Saskatchewan-based Input Capital is the first company to offer streaming financing to farmers – providing working capital for new and growing farms. With almost $110 million available to invest in farm businesses, Input Capital is successfully addressing a major challenge in any business.

Input Capital grew out of the experiences of its principals with Assiniboia Farmland Limited Partnership. “We had been renting land to farmers; many at the beginning of their careers,” explained Gord Nystuen, vice-president of market development for Input Capital. “They were expanding their farming operations and in working with them, we realized how hard it was to get enough working capital to operate the land to its full potential.”

From these observations, and pilot projects conducted since 2009, Input Capital was created in 2012. “We found a way to access financing from public investors right across Canada,” says Nystuen. “Investors find primary agriculture very alluring and we continue to raise capital as we enter our third year of operations.”

“When farms have enough cash on the balance sheet, farm managers can make business decisions that will improve margins,” explains Nystuen. “If inputs are purchased with cash, farmers can get better prices. For example, buying fertilizer and canola seed in fall can be substantially cheaper than in the new year.” Insufficient cash reserves mean trade-offs have to be made. Selling grain to pay bills as opposed to marketing in an orderly fashion with a deliberate strategy creates inefficiencies.

“Our goal is to put the farmer in the driving seat,” says Nystuen. “Working from the strongest negotiating position possible, working capital will enable him to formulate and

execute a strategy to optimize returns for the farm based on his analysis of the markets, prices and weather.”

Input Capital has developed a contract that provides farmers in their program with working capital without taking an ownership position in the farm or farm assets. “We invest for a share of the production, a specified number of tonnes of canola over a six year term,” says Nystuen. “Farmers are committed to deliver a specific number of tonnes, not a specific dollar value of product and our investors, not farmers, assume the price risk.”

“We meet with growers on their farm and evaluate if the farm is viable. We look at their equipment, business strategy and farmland assets,” says Nystuen. “We become a partner. The success of our business depends on the success of our relationship with the farmer. We don’t walk away once the paperwork is signed.”

Input Capital raised $65 million in equity capital in 2013 and has canola-streaming contracts in place with about 21 growers to date, entering its third year of operation. “We have raised another $40 million in equity,” says Nystuen. “And we are starting to realize returns from canola sales. We are looking to partner with more growers this fall and into 2015.”

Over the last five years, Input Capital has worked along side Darin. “Eventually, (he) won’t need us… and that’s how we measure success,” says Nystuen.

Input Capital has representatives in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The goal is to find more qualified farmers and continuing growing farms and growing relationships for the future. Learn more about Input Capital at www.inputcapital.com. The company’s shares trade on the TSX Venture Exchange under the symbol “INP”. Look for Input Capital at trade shows this fall and winter.

Darin Pedersen farms 4,800 acres with his wife Sheri and daughters Brooke (16) and Kristie (10). Two older daughters, Megan and Ashley, live and work off-farm. The Pedersen’s own 12 quarters and rent the balance of their all grain operation north of Nokomis, Saskatchewan. As well as traditional financing for land and equipment, the Pedersen’s have been using streaming financing with Input Capital for the last five years, having been part of the pilot in the years prior to the company forming in 2012.

“I actually met Gord Nystuen at Input Capital through a mutual friend at Pound-Maker,” says Darin Pedersen. “That chance meeting led to our sitting down together and my getting involved in the pilot financing program with Input Capital. There’s a substantial amount of stress involved with a traditional operating line of credit from a financial institution. The financing I get from Input Capital is a better fit and I’d encourage any farmer needing operating capital to investigate what Input Capital offers. Streaming financing may sound complex, however, it’s about paying for capital with production.”

“Input Capital wants to partner with the farmer in a very real and meaningful way,” says Gord Nystuen, vice president of marketing at Input Capital. “That means we encourage our clients to work with professionals like agronomists to up their game, and we stay involved after all the ink on the contract is dried. We are on the farm, at the kitchen table or in the fields, throughout the season understanding their challenges and opportunities.”

2010 was not a kind year to the Pedersen’s. “It was a disaster,” adds Pedersen. “Gord knew we couldn’t meet our commitments to them because we just didn’t have the crop. But we were able to work it out and they made sure we had the resources to produce a crop the following year.”

The mandate of Input Capital is to have farmers succeed. “We

don’t want farmers to have to skimp on inputs,” says Nystuen. “By being able to farm in the smartest agronomic and sustainable way possible, we are creating value for our investors and creating wealth for farmers. Eventually, Darin won’t need us anymore – and that’s how we measure success in the end.”

“Streaming financing may sound complex, however, it’s about paying for capital with production,” says Pedersen

While Darin and his wife are likely to accumulate sufficient financial strength to not require Input Capital in time, he sees a role for this sort of streaming financing when his daughter Brooke is ready to take over the farm. “No successor could go to the bank today and hope to borrow the kind of money required to buy the farm and operate it efficiently and grow it,” says Pedersen. “When my daughter comes back to farm with her agronomy degree and her off-farm experiences in the business, we are expecting Input Capital will be an important part of her success.”

V22-1 has a unique multi-genic, blackleg resistance package providing strong, durable protection against a wide range of blackleg races, and also has R rating for Fusarium wilt. V22-1 is available as part of the 2015 Cargill Specialty Canola Program that delivers higher yields, higher returns in a simple program.

Cargill is also growing its presence in Clavet, Sask. Construction is underway at the canola crushing facility for a state-of-the-art refinery, creating a major hub of food-oil processing and distribution. It will have the capacity to refine one billion pounds annually, making it the largest Cargill refinery in North America. The products that the refinery will produce will include Refined Commodity Canola Oil, Refined Specialty Canola Oil and Refined Blended Oil. These products will be used in foodservice or in food applications.

The company says the decision to add the refinery was driven by customers’ needs. Cargill is investing in new solutions and assets that meet market demands and other business goals that strengthen the food value chain, and Cargill believes they can be the best partner for these customers.

Monsanto Canada continues to work on registration for TruFlex Roundup Ready canola – the company’s next generation canola trait. When commercially available, it will maximize yield potential for farmers while providing unprecedented weed control and significantly increased application flexibility, all with excellent crop safety.

TruFlex Roundup Ready canola will enable a farmer to apply Roundup WeatherMAX herbicide in-crop at 1.33 L/ac for a single application or 0.67 L/ac for two applications – twice the rate of current technologies. This will provide more effective and consistent control of both annual weeds and tough-to-control perennials, and control over a much wider spectrum of weeds including yellow foxtail, biennial wormwood and common milkweed. The application window for applying Roundup WeatherMAX herbicide will extend past the six-leaf stage all the way to the first flower – approximately 10 to 14 days longer than current technology.

Nexera 2020 CL is a Clearfield hybrid with a yield potential of 108 per cent of the commodity Clearfield check. With Nexera’s strongest disease package yet, this variety has an R rating for clubroot, blackleg and Fusarium wilt. Nexera 2020 CL has a high profit potential and is a top performer in standability and ease of harvest. Available at your local Nexera retailer.

New for the 2015 season, Dow AgroSciences is offering the opportunity to grow Nexera canola without a production contract. The Nexera Flexibility Agreement will allow growers to obtain Nexera canola seed contract-free with the marketing flexibility to sell the canola as a commodity product, or if demand exists, sell to one of five contracting companies for the Omega-9 premium. Visit healthierprofits.ca or contact your Dow AgroSciences sales representative for more information.

45S56 is a Roundup Ready canola hybrid that contains the built-in Pioneer Protector sclerotinia resistant trait with a yield potential of 99 per cent of Pioneer hybrid 45S54 in 73 large-scale Proving Ground trials across Western Canada in 2013. It has an MR rating for blackleg and R for Fusarium wilt. 45S56 has great yield potential and very good standability. Available from all DuPont Pioneer

sales representatives across Western Canada.

45H33 is a Roundup Ready hybrid that contains the built-in Pioneer Protector clubroot resistant trait with a yield potential of 101 per cent of Pioneer hybrid 45H29 in 56 large-scale Proving Ground trials across Western Canada in 2013. It has an R rating for Blackleg and Fusarium wilt. 45H33 has excellent early growth and yield potential. Available from all DuPont Pioneer sales representatives across Western Canada.

45H76 is a Clearfield canola hybrid with a yield potential of 102 per cent of Pioneer hybrid 45H73 in 27 large-scale Proving Ground trials across Western Canada in 2013. It has an R rating for blackleg and Fusarium wilt. 45H33 has excellent early growth and yield potential. Available from all DuPont Pioneer sales representatives across Western Canada.

43E03 is a Roundup Ready canola hybrid with a yield potential of 104 per cent of Pioneer hybrid 43E02 in 39 large-scale Proving Ground trials across Western Canada in 2013. It has an MR rating for blackleg and an R rating for Fusarium wilt. 43E03 is a very early maturity hybrid with excellent yield potential. Available from all DuPont Pioneer sales representatives across Western Canada.

D3155C is a D-Series Roundup Ready hybrid that contains the built-in Pioneer Protector clubroot resistant trait with a yield potential of 103 per cent of average of the industry checks in DuPont Pioneer research trials from 2012 and 2013. It has an R rating for blackleg and Fusarium wilt. D3155C has excellent early growth and yield potential. Available at select independent and co-op retails across Western Canada.

PV 531 G is a new, earlier maturing Genuity Roundup Ready canola hybrid. PV 531 G offers competitive yields, world-class standability and an R rating for blackleg. Available through Proven Seed at CPS retail locations.

PV 532 G is a new, early maturing Genuity Roundup Ready hybrid with competitive yields, excellent standability and an R rating for blackleg. Available through Proven Seed at CPS retail locations.

Since 2007, our Research and Development team has been working to improve our Classic Rocket design; resulting in an innovative, stronger and even more reliable rocket. We are pleased to introduce The Next Generation Rocket.

Hopper bottom bins without aeration? It’s not too late to dry your grain!

The revolutionary Retro Rocket is the only do-it-yourself rocket system that allows you to retrofit existing hopper bottom and smoothwalled bins with farm proven Grain Guard aeration.

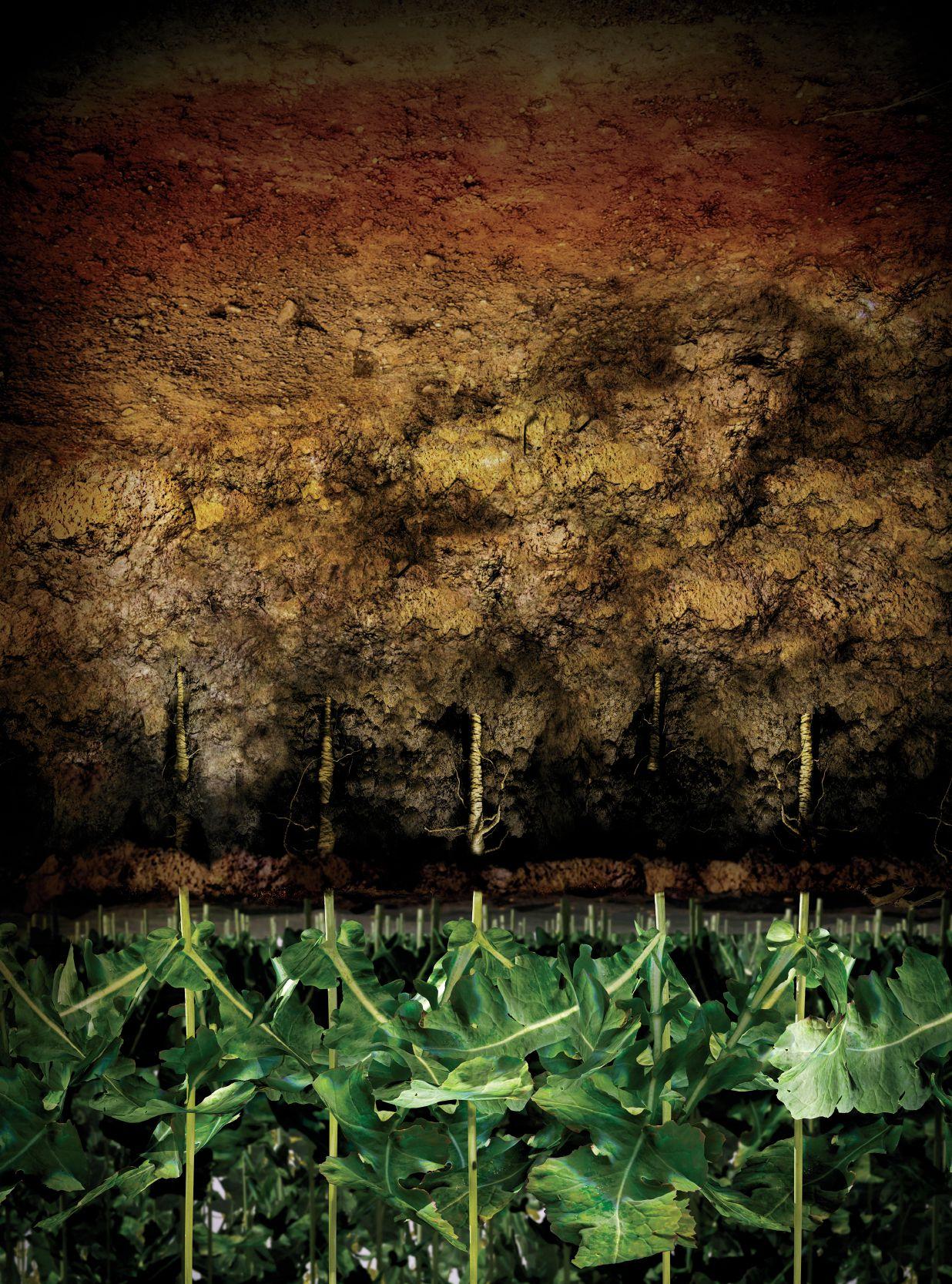

The quest for clubroot resistance goes to an unusual source.

by Carolyn King

Sometimes you have to look in unusual places to find what you need. Dr. Tagnon Missihoun, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Saskatchewan, has taken that idea to heart in a new project. He is leading a team of researchers to hunt for genes that could confer more durable, broader-spectrum clubroot resistance on canola. And they’re looking in a grass.

Canola growers with clubroot-infested fields recognize just how crucial resistant varieties are for managing this serious disease. But Plasmodiophora brassicae, the soil-borne pathogen that causes clubroot, is known to be able to eventually erode such resistance. So researchers are seeking additional resistance genes to make it tougher for the pathogen to evolve to overcome the resistance.

“The number of clubroot resistance genes currently available to breeders is limited, and genetic and strain variation is present in the clubroot pathogen population of Western Canada. Thus we think it’s important to identify novel genes that can confer durable clubroot resistance given that the strain composition of the pathogen population can shift rapidly in response to selection pressure imposed by resistant host cultivars,” explains Missihoun.

As the pathogen’s name suggests, species in the Brassicaceae family – such as canola, mustard, cabbage and stinkweed – are hosts to Plasmodiophora brassicae. Some resistance genes have already been found among canola’s relatives.

But Missihoun is using a non-host species. “Non-host resistance is the most durable, broad-spectrum resistance employed by a plant,” he explains.

“Currently, most of the identified clubroot resistance genes have been isolated from host plant tissues, and can protect plants against only some pathotypes [strains] of Plasmodiophora brassicae In contrast, non-host resistance can potentially confer resistance to susceptible plants against a wider range of, if not all, pathotypes because of the natural resistance that the non-host plant has to Plasmodiophora brassicae.”

According to Missihoun, the strategy of going to non-host plants to find resistance genes “has long been established and scientifically proven to be effective in controlling pathogen attacks in a wide range of susceptible host plants.” For example, one study found genes for resistance to a rice bacterial blight pathogen in tobacco, a non-host for that pathogen.

Missihoun’s project will be the first study to look in a non-host species for clubroot resistance genes to use in canola.

Missihoun is working in Dr. Peta Bonham-Smith’s lab and will be collaborating on this interdisciplinary project with Dr. Simeon Kotchoni from Rutgers University and Dr. Yangdou Wei from the

The study is showing that Brachypodium distachyon is not a clubroot host. When infected with the pathogen (I), the roots don’t get galls, just like the non-infected controls (C). So this grass species could be a source of durable, broad-spectrum clubroot resistance for canola.

University of Saskatchewan. The project is funded by Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund and the Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission (SaskCanola).

Missihoun decided to use a grass species for this project because the majority of non-hosts of the clubroot pathogen identified so far are grasses, such as wheat and winter rye.

He hopes to use Brachypodium distachyon as the project’s grass species. This annual grass is used by the scientific community as a “model species” in research on temperate grasses for several reasons. It is a small plant with a short life cycle, so it’s easy to use in lab and greenhouse studies. It has a small genome that has been

source of clubroot resistance genes for canola.

sequenced, which is very useful in gene-related research. And it is related to the major cereal crop species such as wheat, barley, oat, corn and rice.

So the project’s first objective is to determine whether or not Brachypodium distachyon is a non-host of the clubroot pathogen. If it turns out that Brachypodium distachyon is a clubroot host, then the researchers will use perennial ryegrass, which is a known non-host to the pathogen. Unfortunately, the perennial ryegrass genome is not yet fully sequenced, but there are techniques to overcome this drawback.

To figure out if Brachypodium distachyon is a host or not, the researchers will infect the plant roots with the clubroot pathogen and then monitor plant growth, flowering and seed production. Then they will examine the roots for the presence of clubroot galls (swellings), and will compare the tissues of the infected plants to tissues of plants that were not exposed to the pathogen.

Plasmodiophora brassicae may be able to cause an initial stage of infection in non-hosts. The pathogen lives in the soil as tiny resting spores, which germinate to release zoospores. The zoospores swim through the soil water to a plant’s root hairs and penetrate the cell walls. In this first stage of infection, the spores form structures called plasmodia inside the root hair cells. The plasmodia release secondary zoospores that penetrate the root cells and form secondary plasmodia. It is this second stage that leads to gall formation and serious yield losses.

“Previous studies on other non-host grasses found the clubroot pathogen is able to infect the grass roots until the second stage of its development where further pathogen development is blocked by an unknown defence mechanism of the grasses,” explains Missihoun.

“This mechanism prevents the disease in the non-host and seems to be what is missing in canola and other species susceptible to clubroot. The identification of pathogen proteins that are

recognized by non-host plants is critical to better understand that non-host resistance mechanism. Particular attention will therefore be given to finding the genes functioning in this unknown mechanism in Brachypodium.”

The project’s second objective will be to identify the majority of genes involved in clubroot resistance in the non-host species. The researchers will compare the infected and non-infected Brachypodium plants at the genetic level to see which particular genes were expressed in response to the pathogen’s infection.

And the third objective will be to determine the ability of the identified genes to confer clubroot resistance to canola in the laboratory. This may involve inserting the genes into canola, or it could be that some of the genes are present in canola but need to be expressed differently. The researchers will test canola plants with the resistance genes to see how they respond to the clubroot pathogen.

Missihoun’s project is an intriguing approach to developing durable, broad-spectrum clubroot resistance for the years ahead.

For now, canola growers can take steps to help sustain the resistance in the current clubroot-resistant varieties. The Canola Council of Canada advises growers who are growing resistant varieties in clubroot-infested fields to: rotate their crops, rotate resistant cultivars, thoroughly scout the field at the end of the season for evidence of resistance breaking down, control canola volunteers and weed hosts of the pathogen, and use equipment sanitation practices to prevent the spread of the disease.

For more on clubroot, visit www.topcropmanager.com.

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. Commercialized products have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from this product can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their grain handler or product purchaser to confirm their buying position for this product. Excellence Through Stewardship® is a registered trademark of Excellence Through Stewardship.

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Roundup Ready® crops contain genes that confer tolerance to glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides. Roundup® brand agricultural herbicides will kill crops that are not tolerant to glyphosate. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for canola contains the active ingredients difenoconazole, metalaxyl (M and S isomers), fludioxonil, and thiamethoxam. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for soybeans (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin and metalaxyl. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for soybeans (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually registered products, which together contain the active ingredients fluxapyroxad, pyraclostrobin, metalaxyl and imidacloprid. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn (fungicides only) is a combination of three separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin and ipconazole. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn (fungicides and insecticide) is a combination of four separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, and clothianidin. Acceleron® seed treatment technology for corn with Poncho®/VoTivo™ (fungicides, insecticide and nematicide) is a combination of five separate individually-registered products, which together contain the active ingredients metalaxyl, trifloxystrobin, ipconazole, clothianidin and Bacillus firmus strain I-5821. Acceleron®, Acceleron and Design®, DEKALB and Design®, DEKALB®, Genuity and Design®, Genuity®, RIB Complete and Design®, RIB Complete®, Roundup Ready 2 Technology and Design®, Roundup Ready 2 Yield®, Roundup Ready®, Roundup Transorb®, Roundup WeatherMAX®, Roundup®, SmartStax and Design®, SmartStax®, Transorb®, VT Double PRO® and VT Triple PRO® are trademarks of Monsanto Technology LLC. Used under license. LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. Herculex® is a registered trademark of Dow AgroSciences LLC. Used under license. Poncho® and Votivo™ are trademarks of Bayer. Used under license. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

Developing durable, broad-spectrum resistance with the help of canola’s cousins.

by Carolyn King

Clubroot-resistant varieties are the key weapon for fighting this devastating disease in Prairie canola crops. However, experience in other countries shows the pathogen can evolve to overcome such resistance. The Canola Council of Canada’s announcement in April 2014 of the possible erosion of some forms of clubroot resistance in current canola varieties is a stark reminder that it can happen here, too.

Researchers in Saskatchewan are at work identifying additional resistance genes in canola’s cousins and transferring those genes into canola germplasm. Additional resistance genes can help in two ways: breeders can create cultivars with different resistance genes so growers can rotate between these different cultivars; and breeders can also pyramid the genes – put several different resistance genes together in the same cultivar. Both strategies make it harder for the pathogen to overcome the resistance. Also, the additional genes could protect against additional pathotypes, or strains, of the clubroot pathogen. The result will be more durable and broader-spectrum resistance to the pathogen.

Clubroot is caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae. This soilborne pathogen causes irregular swellings (galls) on plant roots. The galls hinder the movement of water and nutrients into the top parts of the plant. Up to 100 per cent yield loss has occurred when susceptible canola cultivars were grown in clubroot-infested fields in Alberta.

In Prairie canola, clubroot was first found in a handful of fields in the Edmonton area in 2003. By 2013, surveys had confirmed

a total of 1,482 infested fields in the province. The pathogen has also been found in Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

As the pathogen’s name suggests, Plasmodiophora brassicae affects canola and other species in the same family – Brassicaceae – including field crops like mustard, vegetables like cabbage, and weeds such as stinkweed.

One place to look for new sources of clubroot resistance is among these relatives of canola. That’s what Dr. Fengqun Yu, Dr. Gary Peng, Dr. Kevin Falk and several other researchers at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon have been working on, through a number of interrelated studies.

AAFC has provided the lion’s share of the funding for this work, but many other agencies have also given financial support. Some of these are the Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission (SaskCanola), Canola Council of Canada, Western Grains Research Foundation, Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund, Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund, Alberta Canola Producers Commission, and seed companies.

“Canola’s scientific name is Brassica napus. The sources of clubroot resistance in Brassica napus are very limited,” explains Yu. She says the resistance genes in the clubroot-resistant canola cultivars currently grown in Canada are from limited sources and many might have a connection with a single source: a European winter canola cultivar called Mendel.

ABOVE: In these first-generation crosses between clubroot-resistant Brassica vegetables and a canola line, some offspring are clubroot-susceptible (left), so they have swellings on the roots, and some are clubroot-resistant (right).

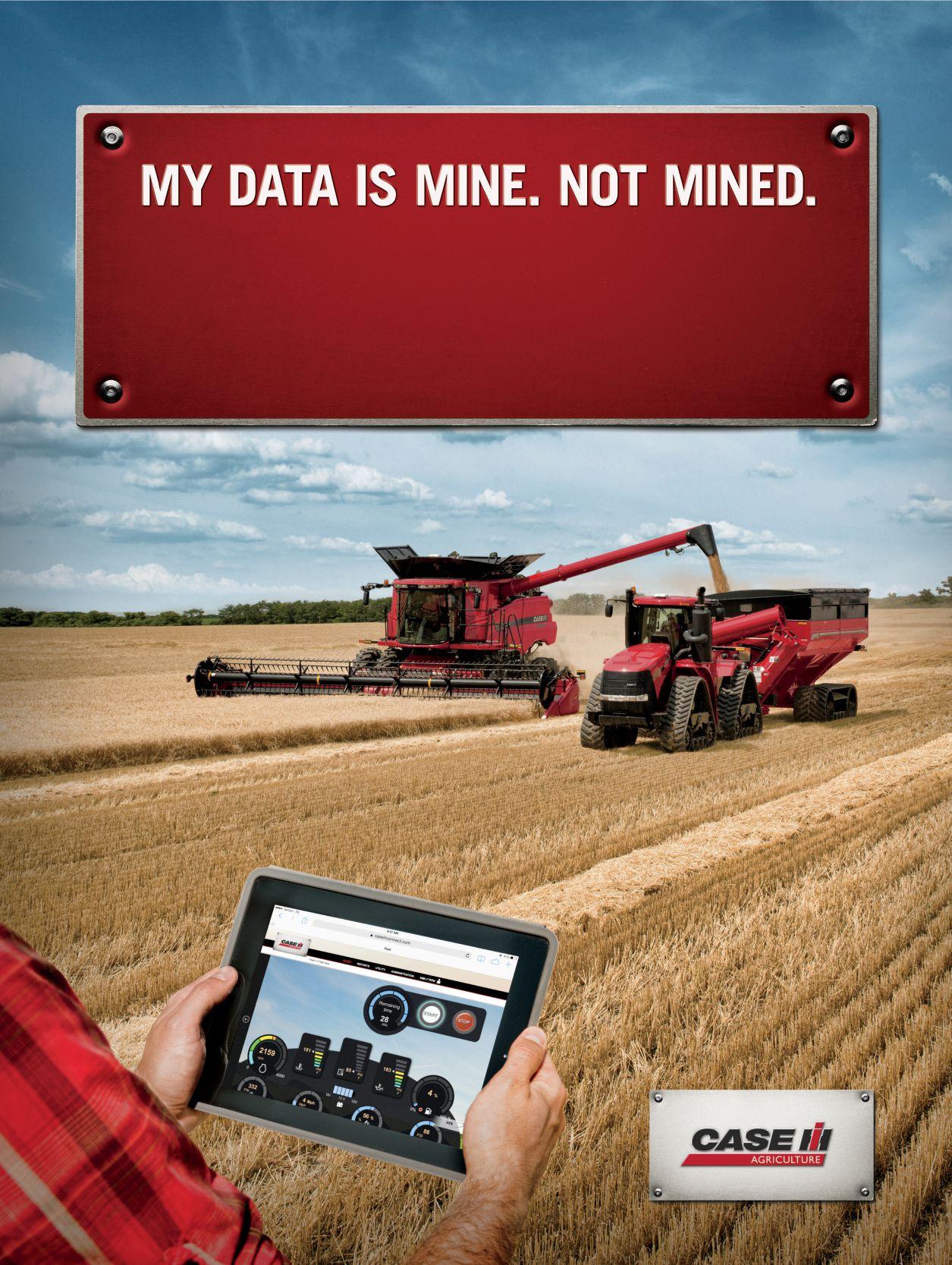

Introducing AFS Connect.™ The only advanced farm management system that guards your data as closely as you. It’s simple. When you buy a combine, a tractor or a piece of land, it’s yours. So when you buy a farm management system that gives you one easy dashboard to track and manage every piece of equipment on your farm, the data should be yours — yours alone. See how AFS Connect gives you total control over your data at caseih.com/afsconnect.

So the AAFC researchers are tapping into the genetic resources of six closely related Brassica species (see diagram). Three of these are “diploids,” and three are “amphidiploids.” A diploid has two copies of each chromosome. An amphidiploid has two diploid chromosome sets, one from each parental species.

The genomes of the three diploids are referred to as AA, BB and CC. The AA genome is in Brassica rapa, which includes various subspecies such as Chinese cabbage and bok choy. Brassica nigra (black mustard) has the BB genome. And the CC genome is in Brassica oleracea, which has several subspecies such as cabbage, cauliflower and broccoli.

Brassica napus is an amphidiploid of Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea, so it’s AACC. Brassica carinata (carinata or Ethiopian mustard) is BBCC, and Brassica juncea (brown mustard) is AABB.

Yu explains the reasons for seeking resistance genes in these Brassica species: “The first reason is that some of these diploid species, like Chinese cabbage, bok choy and cabbage, show very high levels of clubroot resistance against all pathotypes of the pathogen found in Canada.

“Secondly, transferring economically important traits from the diploid species B. rapa into canola is a well-established approach.” Yu herself has transferred three blackleg resistance genes from B. rapa into canola.

Peng and Falk led a study to screen close to 1,000 lines from the six species for clubroot resistance. They found 35 lines with resistance to pathotype 3 of the pathogen. Clubroot pathotypes are currently identified based on their ability to cause disease in a standardized set of hosts. In Alberta, the pathotypes include 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8. Pathotype 3, a very virulent type, is the most common

pathotype in canola crops in the province.

Out of the 35 lines, the researchers decided to begin by working with eight very promising lines, most of which are B. rapa or B. oleracea. All eight have resistance against all five pathotypes.

Yu and several post-doctoral fellows are identifying resistance genes in these eight lines. In seven lines, they have found a single resistance gene, and in one line they have found two.

In all eight lines, they determined that clubroot resistance was a dominant trait. Yu explains, “Dominant resistance is very important for hybrid production. With dominant resistance, the hybrids just need resistance from one parent line. With recessive resistance, both parent lines would have to have the resistance gene.”

The researchers are also mapping the location of these genes within the chromosomes. To do this, they are using two methods that involve molecular markers. So far, they have mapped three of the genes: Rpb1 and Rpb2, which are both on the third chromosome in B. rapa; and Rpb3, on the eighth chromosome in B. rapa

“For two of these genes, the markers are available already for breeders to use in marker-assisted selection. And for a third gene, the marker could be available within one year,” notes Yu.

The markers are being used in another component of this research: “introgressing” the resistance genes into canola germplasm. For example, to introgress resistance genes from B. rapa into B. napus, the researchers would cross a resistant B. rapa line with a B. napus breeding line and then identify the resistant offspring using the markers. Then they would backcross the resistant offspring with the B. napus line, identify the resistant offspring, and so on, to eventually develop germplasm very similar to the B. napus parent but with the resistance gene.

Rpb1, Rpb2 and Rpb3 are being introgressed into canola. A fourth clubroot resistance gene, Rpb4, identified in B. nigra, is being introgressed into B. carinata and B. juncea

Yet another aspect of this research involves “resynthesizing” the amphidiploid species as a way to pyramid resistance genes. For instance, the researchers could cross a resistant B. rapa line and a resistant B. oleracea line to create a resynthesized B. napus line with resistance genes from each parent. They are resynthesizing B. napus, B. carinata and B. juncea and making good progress.

The results of all this work could soon contribute to new clubroot-resistant canola varieties.

“We are not in variety development; instead we develop clubroot-resistant canola germplasm that can be transferred to the seed companies,” explains Peng. “So far, we have transferred two sources of resistance to [a private company’s germplasm, under a collaborative agreement with that company], and we have transferred two resistance genes into our own breeding lines.” AAFC’s clubroot-resistant germplasm will be available to seed companies on a call-for-proposal basis.

In the meantime, Peng advises growers to do as much as they can to protect the resistance in the current clubroot-resistant canola varieties.

“Resistance is the cornerstone of clubroot management in Western Canada. Whenever possible, crop rotation and potentially cultivar rotation need to be kept in mind. Otherwise, eventually, the resistance will be eroded with the change in the pathogen population.”

Excellent advances have been made to increase yield potential and disease resistance.

by Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P. Ag.

Soft white spring wheat (SWSW) and Canadian Prairie spring wheat (CPSW) production is increasing in the Parkland regions of Western Canada in the Thin Black, Black and Dark Gray soil zones.

SWSW has been traditionally grown under irrigation in southern Alberta for end uses in pastry flour markets. In the past, production of CPSW went primarily to the Canadian Wheat Board and domestic feed markets. In recent years, production of both wheat types has increased and has gone to processing into a variety of products including ethanol. These two wheat types have excellent yield potential. Both have excellent potential for production of ethanol as they generally have the highest starch contents of the various cereal crops grown on the Canadian Prairies.

Excellent advances have been made to increase yield potential and disease resistance of SWSW and CPS wheat by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and prairie universities.

These wheat types can be grown successfully across the Parkland region of the Prairies with the appropriate fertilizer and agronom-

ic management. Success with these wheat types offers producers across the Prairies the option of including a uniquely different cereal crop in their crop rotation for domestic ethanol and other markets.

Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development conducted a fouryear research study with SWSW and CPSW in the Dark Brown, Thin Black, Black and Gray soil areas of Alberta to examine seeding agronomy and nitrogen fertilizer requirements. SWSW and CPS wheat were grown successfully at all locations each year, and yields were generally very good to excellent at all sites. Results showed that SWSW and CPS wheat can be grown successfully in the Prairie and Parkland region of southern and central Prairies.

Nitrogen fertilizer response

Both wheat types were very responsive to nitrogen (N) fertilizer in each soil zone, in each year. Increasing N fertilizer rates signifi-

ABOVE: CPS wheat seeding rate treatments of 100 versus 400 seeds/sq metre on a Gray soil at Barrhead.

Table 1.

Source: Adapted from Alberta Agriculture Agdex 112/10-2

cantly increased grain yield and improved grain quality of SWSW and CPSW across all sites and years. However, the magnitude of N fertilizer response varied widely among site years depending on the soil test N level, soil organic matter content and effective growing season precipitation. Maximum grain yields were generally high.

In 2010, CPSW yield at four of five sites was at 100 bu/ac or higher, and for SWSW, was over 90 bu/ac. Generally, CPSW was slightly higher yielding than SWSW at the same locations. The unfertilized grain yields ranged from 30 to 60 bu/ac for SWSW and ranged from 40 to 70 bu/ac for CPSW, depending on the soil test N level and soil organic matter content.

The economically optimum N rate was approximately 100 lb N/ ac based on the average yield response to N fertilization across all

Table 2. Optimum seeding rate range for soft wheat and CPS wheat in each soil zone.

Soil region

Source: Adapted from Alberta Agriculture Agdex 112/10-2

sites, but optimum rate ranged from 30 to more than 145 lb N/ac, depending on the site. Yield was strongly correlated with growing season precipitation, but was not necessarily well related to soil test N level.

From the results of this study, N fertilizer rates for SWSW and CPSW should be based on the range in expected growing season precipitation for a given location, with less emphasis on soil test N. Table 1 provides the recommended rates of N fertilizer based on the assumption of four inches (100 mm) of stored soil moisture at the time of planting plus increasing rates of precipitation at low, medium and high soil test N levels. This table can be used for estimating N fertilizer recommendations for both SWSW and CPSW.

Results showed that N fertilization increased kernel weight and

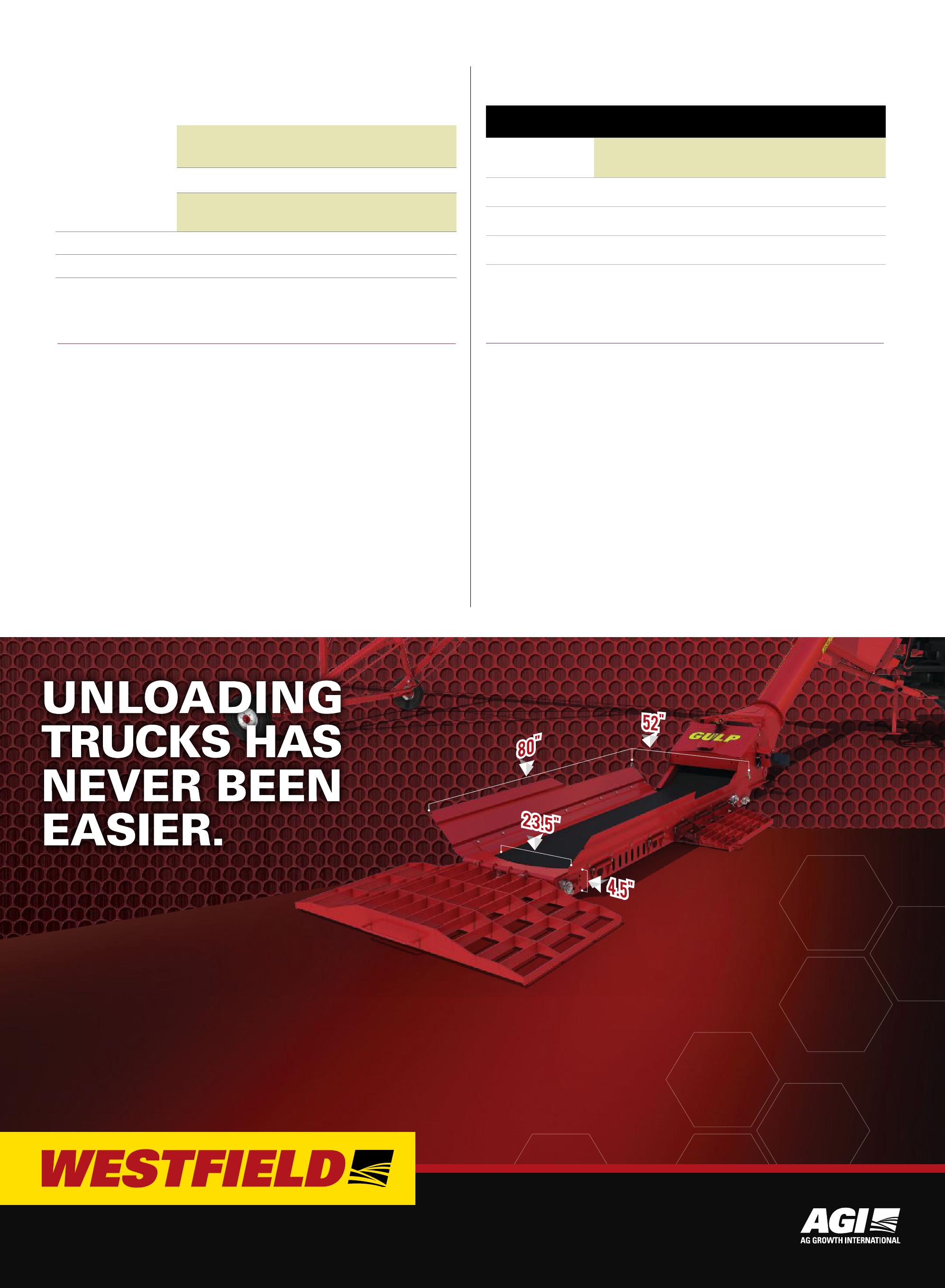

The GULP Drive Over Hopper is the most efficient grain auger accessory on your farm. Through quick and easy equipment deployment and the lowest profile drive over with the largest catchment capacity the GULP saves you time on every truck load.

• Transports with your auger, no disconnecting necessary

• Lowest profile 4.5" drive over height, works with any truck

• Large 52" x 80" catchment area

protein concentration. Added N had either little effect or resulted in a very slight decline in starch concentration, but the slight decline was small compared to the considerable grain yield benefit from increased N fertilizer. Generally, CPS wheat had a slightly higher starch content than SWSW. Therefore, N fertilizer rates suitable for optimum grain production were also suitable for optimum starch production.

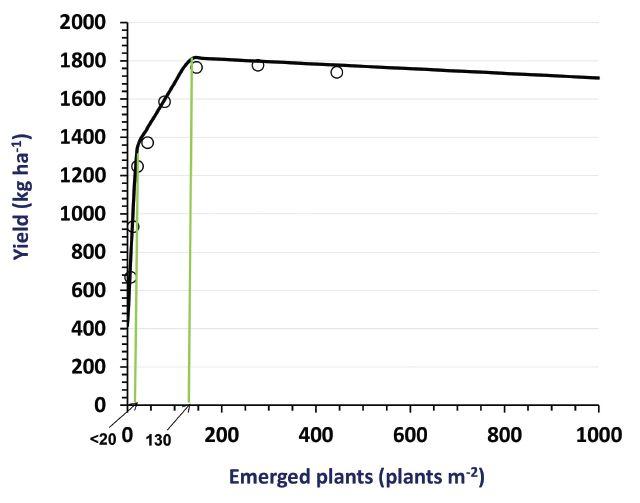

Both wheat types responded to increased seeding rates in each soil zone in each year. The average grain yield was about 15 bu/ ac (17 per cent) higher at 46 seed/ft2 (500 seeds/m2) versus at 9 seed/ft2 (100 seeds/ m2). Increasing the seeding rate was often beneficial to increasing grain yield.

Site years with lower growing season precipitation did not benefit from higher seeding rates, while site years with more than eight inches (200 mm) of precipitation consistently benefitted from higher seeding rates. In this study, the seeding rate for optimum yield for SWSW ranged from 28 to 37 seeds/ ft2 across all soil zones. For CPS wheat, the optimum seeding rates ranged from 26 to 32 seeds/ft2 in the Dark Brown soil zone to 33

to 42 seeds/ft2 in the Black soil zone. Table 2 provides the optimum seeding rate range for SWSW and CPS wheat in each soil zone. Protein and starch concentrations were unaffected by seeding rate, so management practices for optimum yield are also suitable for maximum starch productivity.

SWSW and CPS wheat are excellent for production in the Dark Brown, Thin Black, Black, and Dark Gray/Gray soil zones. Op timum N fertilizer rates for grain produc tion increased with growing season precip itation, but fertilizer N response was not strongly correlated with pre-seeding soil test N levels. Significant yield benefit from increasing seeding rates were observed and were most effective when more than eight inches (200 mm) of growing season precipi tation was received. But results were incon sistent at sites with less than eight inches of growing season precipitation. Starch concentrations were either unaffected or only slightly affected by seeding rate or N fertilizer rate. Agronomic practices that are optimum for SWSW and CPSW grain pro duction were also optimum for starch pro duction.

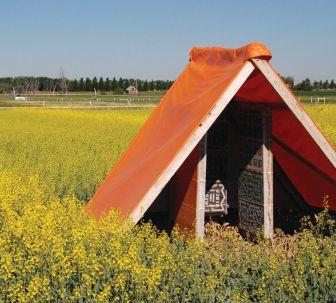

A small parasitic wasp may hold the answer.

by Madeleine Baerg

Since Canada’s first major outbreak of wheat midge in northeastern Saskatchewan in 1983, research scientists, agronomists and producers alike have been fighting to stay on top of the costly orange pest. As its range continues to expand – it moved into central Alberta a decade ago and into the Peace River region over just the past two years – ever more farmers are torn between the temptation to spray and the seeming agony of waiting. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research scientist, Dr. Owen Olfert, explains that when managed correctly and with patience, nature’s own wheat midge solution will play in producers’ favour.

Macroglenes penetrans is a small, black, parasitic wasp with a highly specific taste for wheat midge larvae and a life cycle that uniquely coincides with that of its host. The parasitic relationship takes a full year to complete: the wasps lay their eggs inside midge eggs; the wasp larvae hatch, grow and overwinter inside the midge larvae; the following spring the wasp larvae outgrow and kill their midge larvae hosts. A healthy population of these parasitic wasps will naturally control between 30 and 40 per cent, and under ideal, very-established conditions, as much as 80 to 90 per cent, of wheat midge.

While virtually every wheat producer is familiar with the parasitic insect and its valuable pest-management contribution, the difficulty for producers can be the delicate balancing act required to manage the pest while supporting the parasitoid.

“Bio-control remains one of the less common pest-management tools. Some producers find it challenging because it is not immediately effective (unlike a chemical pesticide application). But, I would say the enthusiasm is there. The level of control we’re getting speaks to producers recognizing that they will get some benefit if they just take care of the beneficials,” says Olfert.

“Wheat midge has been an issue in parts of the Prairies since the mid-1980s, so some producers have a long history of dealing with them. However, we continue to receive questions from producers in newly infested areas, especially about how long they have to wait before the parasitoid will arrive, and how they can help it get established.”

Macroglenes penetrans, itself an invasive species that likely tagged along when wheat midge entered Canada more than 100 years ago, typically follows one to two years behind the movement of wheat midge infestation. It can be a challenging wait, even for entomologists.

“In northern Alberta, the first year (after wheat midge infested), there were absolutely no parasitoids found. We were already beginning to discuss the option of rearing parasitoids in the south and in-

troducing them up there. In the second year, we discovered the parasitoids in low numbers, which is quite typical in what we’ve found in Saskatchewan previously,” says Olfert.

The very fact that Macroglenes penetrans exist on the Canadian Prairies is lucky chance.

“It’s not always the case that a parasitoid is found. In fact, it’s quite rare because quite often these alien invasive species show up without any of their natural enemies. Essentially, everything we developed after we first found Macroglenes penetrans was twofold: we wanted to control the pest but we really wanted to preserve this natural enemy,” says Olfert.

Wheat crops are only susceptible to wheat midge during the narrow window prior to flowering when the wheat head comes out of the boot. During this time, careful monitoring for the pest is vital

It’s the farm version of burning rubber. The convenient new liquid formulation of Heat® LQ provides faster mixing and tank cleanout. Tank mixed with glyphosate, it delivers control of broadleaf weeds that’s 3 to 5 times faster than glyphosate alone in pre-seed or pre-emerge applications. Plus the unique mode of action of Heat LQ controls both Group 2- and glyphosate-resistant broadleaf weeds in cereals and pulses. Visit agsolutions.ca/heatlq or contact AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273).

since midge populations can explode under the right environmental conditions. Of course, monitoring is easier said than done, since the only time adult midge can be easily counted in the crop canopy is near dark in warm and wind-still conditions. For this reason, Olfert and several colleagues are currently working to develop an online tool that provides geographically specific growing degree day calculations that would forecast wheat midge emergence. This, combined with provincially available forecast maps developed on the basis of the previous season’s larval cocoon counts, will go a long way towards helping producers make more informed spraying decisions.

“The economic threshold when yield is the primary consideration is one adult per four to five heads in several locations in the field. The threshold is a little lower – one adult per eight to 10 heads – when No. 1 grade wheat is typically expected. We don’t have a handle on the negative impact that incorrectly applied pesticides have on wheat midge’s natural enemy. But, if you’ve only got one adult in more than 10 wheat heads,

you certainly shouldn’t be spraying at all. Yes, you’ll get a little wheat midge activity, but leaving the midge and the parasitoid active means the parasitoid has free range all summer long to increase control and pull up its numbers,” says Olfert.

Recognizing the value of the parasitoid, all wheat midge-resistant cultivars are now sold with five to 10 per cent susceptible wheat so the parasitoid can survive on the midge population confined to the susceptible plants. Some producers choose to be even more proactive in order to support the development of a healthy parasitoid population.

“When we go to producer meetings in some areas that are newly infested, there are usually a few farmers that have one or two fields (in which) they are willing to risk yield just to make sure the parasitoid gets established. There are always some people who are thinking ahead. It’s a good technique, one we would recommend in areas where we are sure there are parasitoids but they are still in low numbers,” says Olfert.

While Olfert does not expect all producers to follow suit, he does recommend that all producers keep the parasitoid in mind when making any pest-management decisions. After all, working with nature is less expensive, more effective and better for the environment than jumping directly to the chemical option.

Although FHB resistance is improving in cereal varieties, resistance alone is not sufficient to control the disease.

by Donna Fleury

Across Western Canada, researchers have been working on Fusarium head blight (FHB) resistance improvements for wheat. Over the past few years, there have been some positive advances; however FHB is a very challenging disease to work with and the breeding effort is slow. Overall there is much work being done from many different groups, with significant resources and investment into improving FHB resistance in wheat.

“Fusarium is one of those diseases that are quite resource intensive to test for and to work with,” explains Dr. Anita Brule-Babel, professor, department of plant science at the University of Manitoba. “As a winter wheat breeder, I have several collaborative projects underway, including some with objectives to breed for FHB resistance. We have several graduate student projects in place, including mapping new FHB genes and the development of markers for wheat and barley. Through various collaborations, we are working with many researchers to try to identify and advance marker de -

velopment. Markers will help us to be able to combine multiple sources of resistance together to make varieties more resistant and also to facilitate and speed up the breeding process.”

Brule-Babel also runs a large FHB screening nursery for all the breeders in Western Canada at the Ian N. Morrison Research Farm in Carman, Man. The breeders send their material to the nursery for screening, special tests and co-operative registration testing, and they receive data in return, including data for variety registration documents. In 2013, 3500 winter wheat lines and about 16,000 spring wheat lines were tested in the nursery.

“We are seeing improvements in varieties in terms of resistance

TOP: After each FHB inoculation, a mist irrigation system is used to provide the required humidity for optimum disease infection at the FHB nursery. This system is run for 5-10 minutes every hour for 12 hours after each inoculation.

INSET: Fusarium head blight symptoms on susceptible check cultivars from left to right: AC Morse, AC Vista, CDC Teal.

that are being registered for both spring and winter wheat varieties,” says Brule-Babel. “Across the classes of wheat, the most progress has been in the red spring wheat class (CWRS), which is the biggest of the crops and has the most investment. There has been a significant improvement in this class.”

In 2014, 27 per cent of CWRS varieties listed in Seed Manitoba had a moderately resistant (MR) rating compared to six per cent in 2009. Seven out of 11 lines supported for registration in February 2014 in the CWRS class were MR to intermediate (I) in FHB reaction. Across all spring wheat classes over 17 per cent of varieties available in 2014 were MR compared to less than five per cent in 2009.”

Improvements in some of the newer classes, such as hard white wheat, are being made, but they are taking a bit longer. Amber durum continues to be one of the most difficult wheat types to breed FHB resistance because really good sources of resistance are difficult to find. Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan have identified resistance in a relative of durum, but it will take time to breed that resistance in, and regain the good qualities of, an amber durum.

“Although there are lots of breeding efforts underway, to date FHB resistance is not complete as compared to resistance for other diseases such as leaf or stem rust resistance,” explains Brule-Babel. “There are many FHB resistance genes with small effects, phenotyping is difficult and the host-pathogen interaction is not well understood. Another challenge is that FHB reaction must be evaluated on multiple plants from the population at the adult plant

wheat breeding lines that were tested for Fusarium

resistance. The short line on the right is highly susceptible, while the tall line to the left has few FHB symptoms.

stage, making controlled environment screening more difficult. As well, the interaction between resistance types complicates evaluation and selection.”

Other researchers have characterized five types of resistance to FHB. Type I, which is resistance to initial infection, and Type II, which is resistance to spread within the spike, are the most understood. “We have a pretty good handle on these two types of resistance and that gets us part of the way. However, on the market side,

Grow the world class BrettYoung Genuity® Roundup Ready® varieties on your farm this season – you will not be disappointed. We select each variety to meet the performance needs of Western Canadian growers. Our priority is helping you grow.

grain is graded by Fusarium damaged kernels (FDK), but customers are interested in the DON toxin levels. The most economically important forms of resistance (i.e. DON) are the most difficult to evaluate and are not well understood. Under some conditions there may be a low correlation between visual symptoms and DON, and FDK does not always predict DON.”

In general, the different types of resistance should be linked, so if there is less FHB infection, then there should also be less DON. However, Brule-Babel has recently found a couple of lines that symptoms-wise were identical, but one line had 22 ppm DON while the second line had 1.5 ppm DON. “This is a massive difference in DON levels, so we are looking at the next stage of DON resistance to address this question. For example, we are trying to determine whether we can get wheat to metabolize and degrade DON so it doesn’t accumulate in the seed. This is not an easy thing to work with, but we are trying to move efforts forward in this area. Researcher Lily Tamburi-Illincic at the University of Guelph

recently released a new line rated MR but with considerably lower DON than other lines rated as MR. So some advancements are being made to address this challenge.”

Fungicide-resistance interaction affects DON

In another project, a graduate student is looking at the differences in the response of MR and susceptible lines and the efficacy of fungicides of different genotypes. It was found that when there is a high risk of an epidemic, growers should have already grown a more resistant variety to make the fungicide application work.

“We’ve found in some cases, depending on the level of epidemic and genotype, that an application of fungicide to a susceptible variety may actually increase DON levels,” explains Brule-Babel. “We suspect that although it seems the number of lighter, highly infected kernels are reduced, actually the combine is retaining more of the heavier kernels that are still heavily infected with Fusarium. However, when growers use a MR to intermediate variety and ap -

We’re used to other varieties bowing down to us

It’s no secret that Proven® Seed offers high-yielding canola varieties that stand tall for ease of harvest. In fact, Proven Seed offers superior genetics from the best canola-breeding programs in Western Canada to ensure first-rate results for growers. Talk to your CPS retailer to select the best Proven Seed canola variety for your farm. Book your 2015 seed now and save. Learn more at provenseed.ca

ply fungicides, this doesn’t happen to the same extent.”

Therefore, when using fungicides, growers need to make sure they already have some good genetics to support that fungicide or they won’t get the results they want. Fungicides don’t do the job completely nor does the resistance do the job completely, but together they improve things considerably.

“Growers also need to pay attention to disease forecasts and risk maps to understand the risk of infection,” says Brule-Babel. “There are good forecasting programs such as the FHB risk models in Manitoba and DONcast model in Ontario. If the conditions at flowering aren’t right for Fusarium infection, then growers don’t necessarily need to be worrying about a fungicide application.”

FHB requires a multi-pronged management strategy that includes using fungicides when needed, but to also work with the whole toolbox of alternatives to reduce the risk of selection pressure for resistance to fungicides. Like herbicides and insecticides, it is well known that overuse of fungicides can lead to the risk of selection for resistance. Therefore, growers should also use different modes of action if they are applying fungicides year after year. Rotation is always a good idea for diseases, but this may not be the answer for FHB as there are a lot of other unknowns and inoculum can move around between fields. The FHB pathogens are necrotrophs that live on dead tissue and aren’t that selective, so even canola or other crop stubble can host the pathogens.

“As we advance our FHB resistance breeding efforts, we are continuing to apply new tools to our work,” says Brule-Babel. “Some of the new molecular tools are very exciting, they are cheaper and

faster and we can do more with them. We are always struggling with our breeding programs to find the balance between resources available for molecular tools and the phenotyping in the field. The tools help advance our efforts, however the results still have to be proven in the field. We expect to see continued advancements in FHB resistance for all classes of spring and winter wheat and other cereals such as barley in the future.”

For canola growers, making the right fertilizer decisions can be a difficult task. The Mosaic Companysponsored research on seed safety and yield provides important information to assist in those decisions.

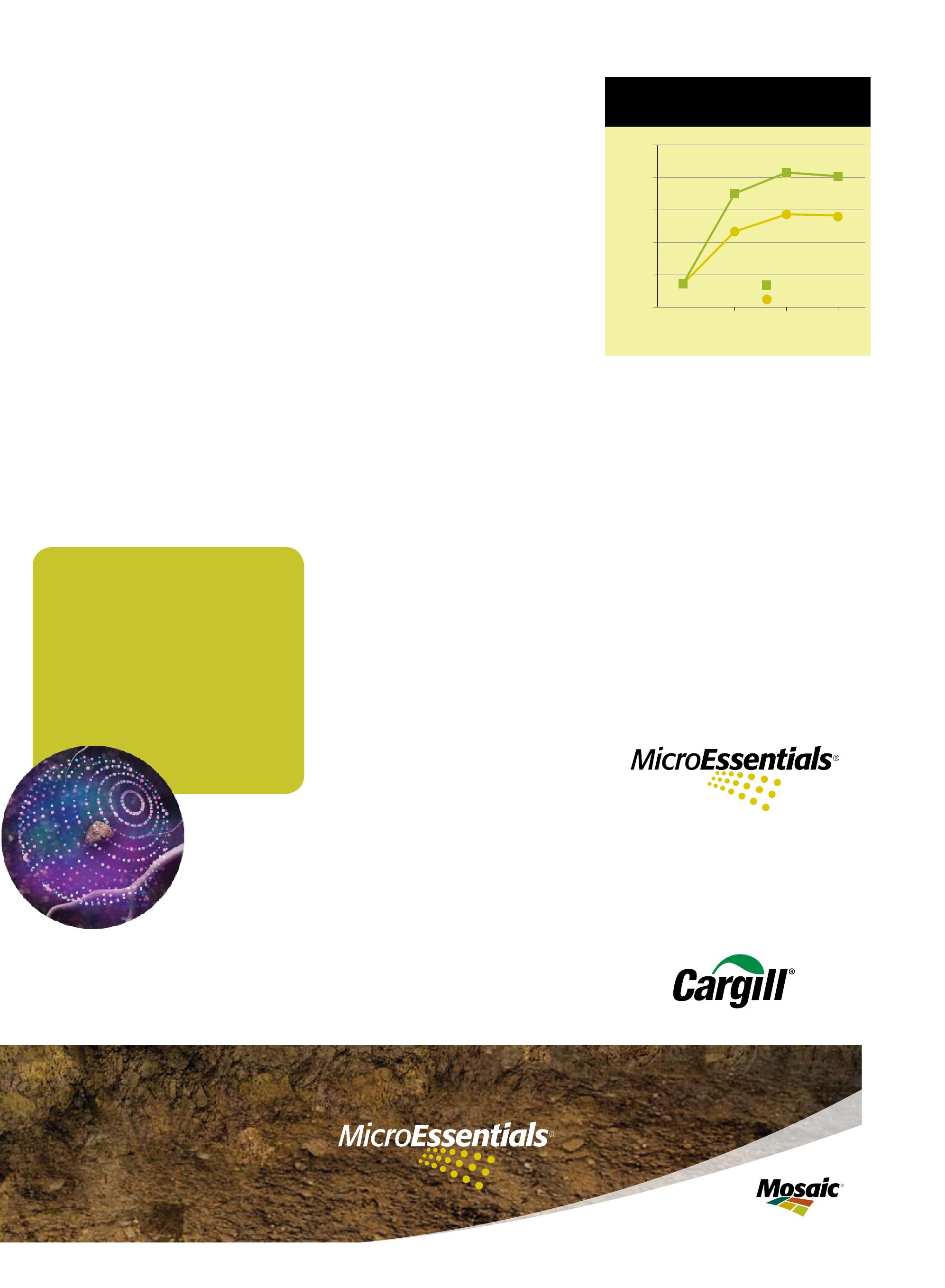

In those studies, The Mosaic Company evaluated the yield response of MicroEssentials ® S15 TM (13-33-0-15S) compared to MAP + ammonium sulphate (AS) blend (11-52-0 + 21-0-0-24S) in canola at different P2 O 5 rates when applied with the seed.

At the same time, assessments were drawn to evaluate the potential for MAP + AS fertilizer to cause seedling damage compared to MicroEssentials S15.

Research demonstrates that MicroEssentials S15 not only provides a better return on investment than AS, but also gives growers application rate versatility with less potential for seedling injury.

Development of modern seed genetics that contain new postemergence herbicide technology, combined with innovative reduced-tillage seeding equipment, have

transformed crop production practices over the past 15 years in Western Canada. The yield benefits of reduced-tillage systems for conserving soil moisture have resulted in the majority of farmers converting to banded applications of fertilizer with a reduced-tillage air seeder for many crops, to maximize yield and increase time efficiency in the spring.

However, placing traditional MAP + AS fertilizer blends in close proximity to the seed in a banded application can result in seedling injury and limited yield because of reduced stands.

With higher seed costs, one of the important advantages of MicroEssentials S15 is that it has a lower total nitrogen rate compared to an equivalent MAP + AS fertilizer blend, allowing farmers to safely apply MicroEssentials S15 over a wide range of application rates with less potential for seedling injury.

In the yield response and plant population study, all nutrients were balanced across treatments, with fertilizer applied at the same time as the seed. MicroEssentials S15 outperformed MAP + AS by 3.0 bu/ac across all locations when applied at a 33-lb P2 O 5 rate, and showed higher yield at all P2 O 5 rates.

Every plant needs balanced crop nutrition to reach its full potential. The innovative Fusion® technology behind MicroEssentials ensures uniform nutrient distribution across the field. By including nitrogen, phosphorus and sulphur in one granule, distribution is even, allowing every plant to receive the correct amount of each nutrient.

With its patented Fusion ® technology, MicroEssentials ® S15™ combines vital nutrients into one uniquely formulated, nutritionally balanced granule supplying even distribution and balanced fertility across the field.

Because each MicroEssentials granule is nutritionally balanced, uniform distribution is easily achieved — plant roots have more sites that can be reached with the key nutrients for optimal growth. The proven

formula delivers vital nutrients in a ratio best suited to the health and productivity of each and every plant, resulting in higher yields and higher profitability.

In the early growth stages, young seedlings must receive the proper amount of phosphorus to reach their full potential. Without it, root growth suffers, making it harder for plants to take up other key nutrients. The unique chemistry of MicroEssentials is formulated to increase the efficiency of nutrient uptake in young plants.

The innovative chemical composition of MicroEssentials creates an acid zone around each granule. By lowering the pH, MicroEssentials promotes the formation of di-hydrogen orthophosphate, which plants prefer.

To reach optimum yield goals, today’s canola growers recognize that crops need additional sulphur.

Early in the growing season, MicroEssentials’ sulphate sulphur provides young plants the balanced crop nutrition needed for optimum growth. However, plants dependent on fertilizer containing sulphate sulphur alone are vulnerable to the yield-robbing impact of leaching. MicroEssentials solves this problem by delivering season-long availability through its uniquely formulated combination of 50 percent sulphate sulphur (for immediate availability to the plant) and 50 percent elemental sulphur (for

Yield response comparing MicroEssentials S15 to MAP + AS blend*

availability throughout the growing season, after oxidation).

MicroEssentials increases both your yield and your bottom line. Research suggests that up to 60 percent of yield depends on providing adequate balanced crop nutrition. Contact your local Cargill agronomist or sales representative for more information on MicroEssentials.

To learn more, get your head in the dirt at MicroEssentials.com.

genetic differences in seed losses due to pod drop and pod shattering.

by Donna Fleury

As more canola growers look to straight combining as an option, researchers are working to help understand the opportunities and risks. Although straight combining canola can save time and money and result in improved seed quality, harvest timing is critical. Cultivar selection, timing of harvest and weather conditions influence the relative shattering resistance and pod drop losses of canola.

The Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF) in Saskatchewan started a four-year study in 2011, with funding from SaskCanola (Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission), to evaluate the relative resistance to pod shatter and pod drop of high-yielding Brassica napus hybrids.

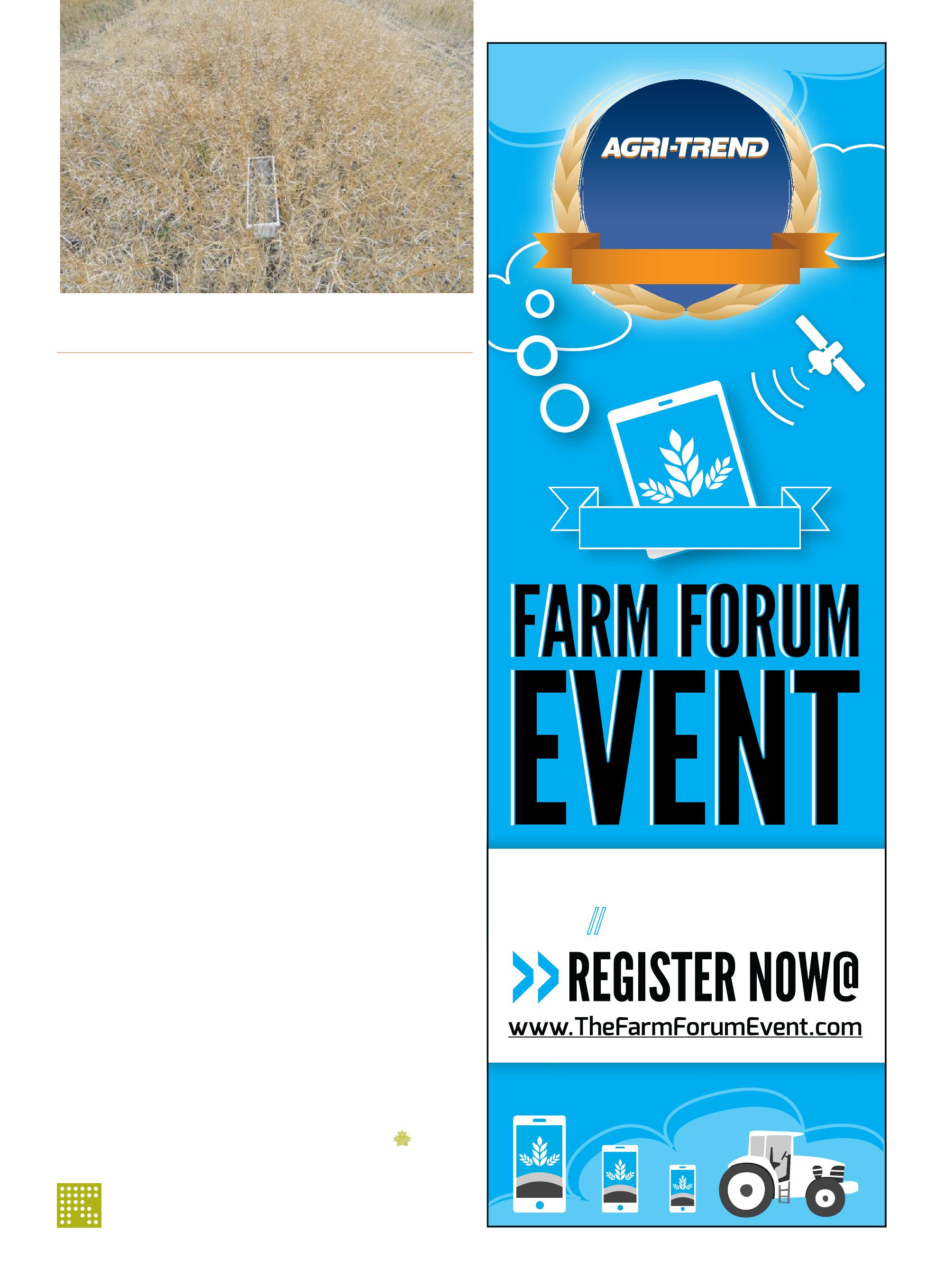

“We set up trials at four sites including Indian Head, Melfort, Scott and Swift Current and evaluated several modern B. napus hybrids to identify cultivars that may be particularly well suited for straight combining,” says Chris Holzapfel, IHARF research manager. “We compared two harvest dates, one at the optimal harvest timing and the final harvest completed three to four weeks later.

We also wanted to quantify the environmental seed loss contributions from pod drop versus pod shattering under a wide range of environmental conditions.”

Over the four years of the study, as new cultivars with improved shattering resistance became available, they were added to the trials, with a total of 16 hybrids evaluated over the study period. A seeding rate of 115 viable seeds/m2 was used in all trials and all plots were direct seeded into standing cereal stubble. Recommended fertilizer rates and herbicides for specific herbicide resistance systems were applied. At each site the plots were designed to be large enough to ensure there was enough for two separate passes to be completed at the two distinct harvest dates. The first harvest date (T1) was targeted at, or slightly before, the optimal harvest stage (seed dried to 10-12 per cent moisture content with two per cent or less green seed). The second harvest date (T2) was targeted

ABOVE: Four weeks past the optimal harvest date, this variety had very little shattering on Oct. 15, 2013.

at three to four weeks past the optimal stage.

“The results from across the trials were as we expected – the observed yield losses due to pod drop and pod shatter generally increased as harvest was postponed past the optimal crop stage,” explains Holzapfel. “However, the extent to which these losses increased varied dramatically depending on the specific conditions encountered. In years where shattering losses were low, such as 2013, all of the cultivars evaluated performed pretty well. However, in years where conditions were challenging, such as the severe wind events in 2012 and higher than usual sclerotinia incidence, all of the cultivars were impacted and there were severe losses in all treatments. Substantial losses in all cultivars occurred when severe conditions were encountered and the opposite was generally true under more favourable conditions.”

Overall, the total losses averaged across all sites with straight combining were typically less than five per cent for all hybrids. Provided that combining was not excessively delayed, this is unlikely to have much impact on yield relative to swathing. For the second harvest date or delayed harvest, the actual losses were extremely variable. Depending on the hybrid and sites evaluated, the average total losses could exceed 10 per cent and, under extreme conditions, some individual cultivars sometimes exceeded 30 per cent total losses. While yield losses due to pod drop were typically negligible with early harvest, these losses frequently exceeded those due to pod shatter when harvest was delayed by three to four weeks. Pod drop appears to be a factor of increasing importance as straight combining is delayed.

“While genetic differences in resistance to environmental seed losses do exist, all of the hybrids evaluated could be straight combined successfully, provided that harvest is completed in a reasonably timely manner, disease pressure is low and extreme weather is not encountered during the critical crop stages,” says Holzapfel. “The differences amongst hybrids were typically much smaller than the differences observed between harvest dates or from one site to the next, and the observed differences were not always consistent from year-to-year or site-to-site.

“Therefore, other factors such as overall yield potential, days to maturity, standability and herbicide system are likely at least, if not more, important to consider when choosing a canola hybrid with the intention of straight-combining,” he adds.

The trials continued through the 2014 growing season at all four locations, and researchers expect to see similar results. For more on harvesting canola, visit www.topcropmanager.com.

Researchers develop a fast and effective test for disease inoculum.

by Madeleine Baerg

As the crop’s first flowers start to bloom in as many as 20 million acres of canola next summer, Canadian farmers will yet again face an impossible decision.

Some farmers will opt to fight sclerotinia stem rot, canola’s most common and costly disease, with an expensive, time consuming, and quite possibly unnecessary fungicide application. Others will choose to save input dollars by skipping a preventative fungicide application, thereby risking as much as 50 per cent of their canola crop’s ultimate yield if the crop becomes infected with sclerotinia.

Either way, the farmers’ decisions will be made mostly blindly: calculations based on experience, gut feel and prediction. This is because, unlike almost every other disease, sclerotinia needs to be controlled before it is visible, before science can reliably detect its presence or forecast its damage in a crop. But that frustrating reality may change in the near future.

University of Alberta PhD candidate, Barbara Ziesman, is currently developing a DNA-based canola petal test that will reliably identify sclerotinia inoculum on canola flower petals in as little as six hours. Unlike the current sclerotinia culture test, which takes four to five days to identify sclerotinia’s presence in a crop, the DNA-based test will provide results quickly enough that a producer has time to control an infected crop with fungicide.

“The DNA-based test allows us to see a spike in inoculum much faster than a traditional plate test. By giving us these quick results, a farmer will be able to make better control decisions,” explains Ziesman. “The information provided is more than the per cent petal infestation estimates that the traditional plate test provides. Because the DNA test identifies how much inoculum is present on each petal, if a farmer were to test several times in a growing season, they’d be able to apply fungicide when the inoculum is at its highest.”

In addition to faster results, the test also offers the added benefit of greater accuracy. Unlike a culture test in which a technician identifies sclerotinia by its physical characteristics, the DNA test is entirely machine controlled, reducing the possibility of human error.

Already, Ziesman has achieved the first major hurdle: developing the process to isolate sclerotinia DNA and amplify these genes to calculable levels in petal samples.

“The test itself is validated: it is sensitive, specific and reliable,” she says.

That said, a quick and effective petal test is only the first component of a reliable forecasting method. Currently, Ziesman is working on developing an outline for the second, less easily defined and far more challenging component of forecasting: combining petal test results with the many external factors that influence disease development.

“What we’re seeing right now is that there is a relationship between how much sclerotinia DNA is identified and the risk of developing a specific level of disease. The challenge is that so many conditions and factors influence the actual development of the dis-

Bright golden yellow as far as the eye can see. Now that’s the mark of a truly successful canola crop. But when you plant with seeds treated with DuPont™ Lumiderm™ insecticide seed treatment, you’ll see the benefits of flea beetle and cutworm protection long before the first hints of yellow begin to grace your fields. That’s because Lumiderm™ helps get your crop off to a better start. And a better start means a better harvest.

Ask your seed retailer or local representative to include Lumiderm™ on your 2015 canola seed order and realize a better start. Visit lumiderm.dupont.ca.

DuPont™ Lumiderm™ is a DuPont™ Lumigen™ seed sense product.

ease,” she says. “Though we’ll never be able to predict with certainty exactly how much disease will develop in any given field, what we are working to develop now are risk level thresholds. To be useful as a risk assessment tool for growers, sclerotinia risk thresholds have to take multiple factors into consideration, because multiple factors will affect the actual disease development.”

For example, the thresholds may need to quantitatively or qualitatively consider everything from crop characteristics like density, seeding rate, crop height and yield potential, to environmental conditions including precipitation, humidity and temperature.

Ziesman and a team of collaborators have collected petal samples from the Edmonton region and analyzed them in relation to growing conditions in the same area for the past four years.

In 2011, Ziesman noted a discernable trend in the percentage of petals that tested positive for disease in the test fields versus disease development. However, because the year’s growing conditions were not ideal for disease development, the results were not substantial enough to be considered statistically significant.