TOP CROP MANAGER

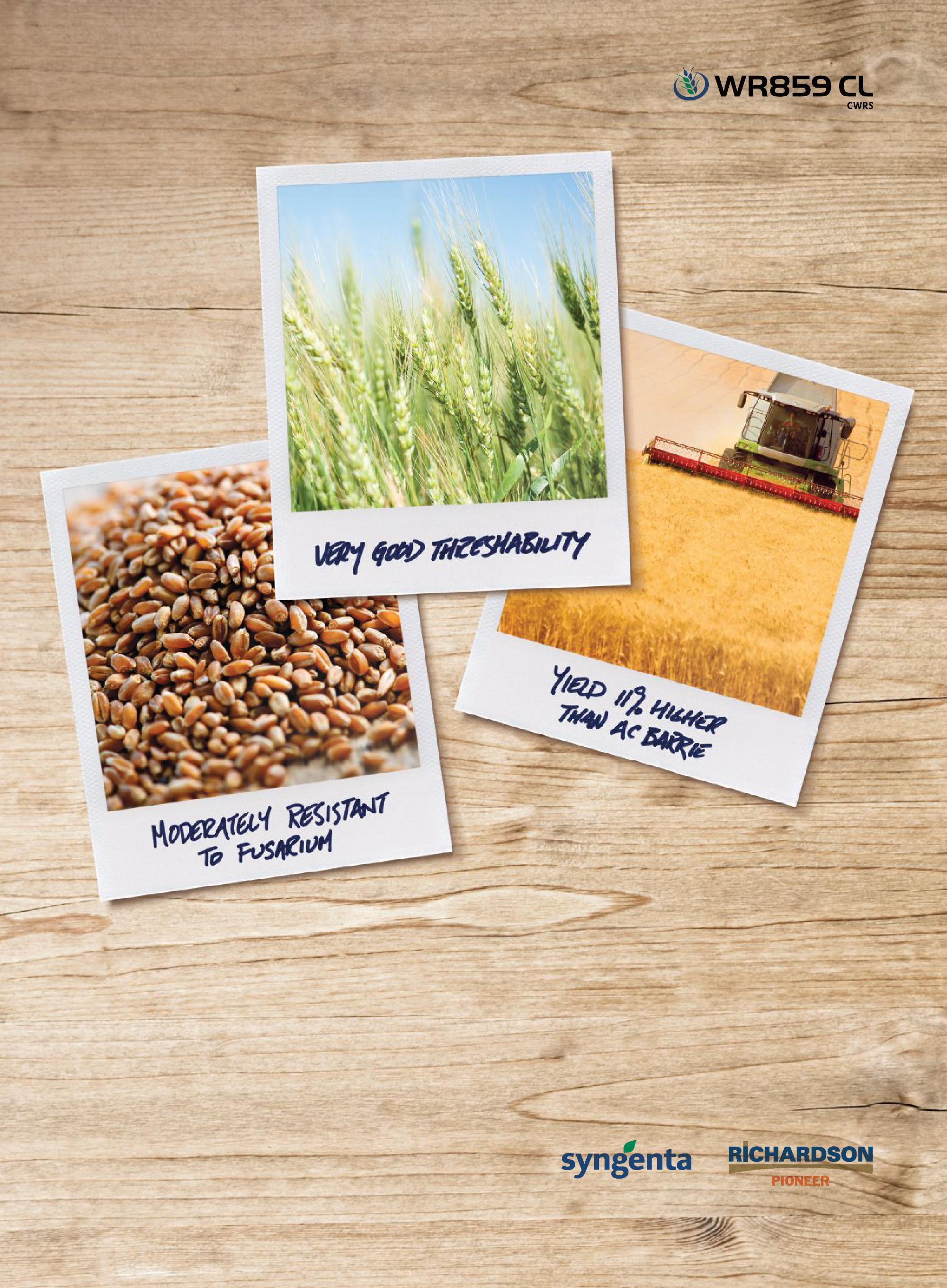

Cereal seed from Syngenta helps growers harvest opportunities wherever they are. We’ve been breeding wheat in Canada for four decades, setting unprecedented standards for yield, quality and sustainability. The world depends on Canadian grain, and Canadian growers count on Syngenta.

By Bruce Barker PLANT BREEDING

10 | 38 new varieties in 39 years Lacombe breeding program has gone from the kernel of an idea to a highly productive program.

By Carolyn King

PLANT BREEDING

52 What is new in Canola?

By Bruce Barker

CROP MANAGEMENT

6 Feed the crop and not the weeds

By Carolyn King

FLAX

18 eco-friendly phone case with flax fibre and shive

By Carolyn King

SPECIAL CROP

56 Higher-yielding varieties with improved quality

By Carolyn King

FIBRE CROPS

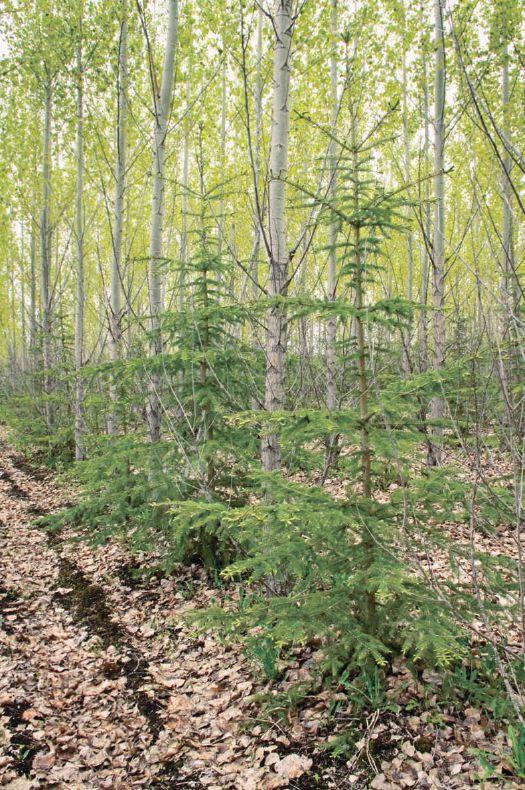

60 Making the business case for growing trees

By Tony Kryzanowski

26 | Cropping system affects root and crown rots

Integrated approach helps reduce disease pressure.

By Carolyn King

MARKETS AND MARKETING

22 another marketing option for canola growers

By Carolyn King

STORAGE

32 Management tips for safe grain storage By John Dietz

BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

36 Diversification for success By John Dietz

63 Caution on the road to retirement riches

By John Dietz

ISSUES AND ENVIRONMENT

44 getting a little more help from farmers’ many-legged friends

By Carolyn King

38 | Measuring harvest loss in canola Losses can be surprisingly high.

CANOLA

68 Tight canola rotations impacting yield By Bruce Barker

76 Innovative methods for managing flea beetles in canola

By Juliana J. Soroka and Bill Elliott, AAFC

MACHINERY

48 Don’t mix tall farm equipment and power lines

By John Dietz

THE GRAIN GUARDIAN

72 Increase effectiveness and efficiency

FROM THE FIELD EDITOR

4 Is the bloom coming off canola? By Bruce Barker

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

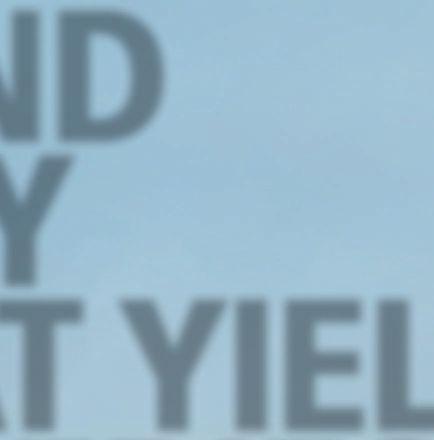

The year started off so promising. a record 21 million acres seeded to canola, up 2.4 million over 2011, and a sixth consecutive record for canola acres. The spring weather was relatively conducive for seeding and early crop growth, and then July came along. Sclerotinia stem root, blackleg, aster yellows, and heat stress kept chinking away at the yield potential. a final straw was the massive windstorm that blew through the prairies, taking swathed canola along with it.

In the end, Statistics Canada estimated in September that actual canola production would be down 8.1 percent, despite a 12.8 percent higher seeded acreage. average canola yield dropped to 28.2 bushels per acre, the lowest since 2007, and more on par with yields in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This despite the impressive advancement in canola genetics over the last 12 years.

This disappointing production would be easy enough to write off to bad weather conditions, and it was most certainly a major culprit, but word coming back from across the prairies also points to emerging disease problems. Blackleg is back and the disease has mutated to overcome resistant genes in some areas. Sclerotinia was an issue in traditionally drier areas that have not had problems in the past. a ster yellows were widespread.

Tighter rotations bring increased disease pressure, and as this issue’s article on tight canola rotations shows, tight rotations come at the expense of yield. o f course, all crops compete for acres based on profit potential, and after years of marginal economics for many crops, growing more of the most profitable crop is hard to resist. Whether canola becomes a victim of its own success remains to be seen, but as the old saying goes, “There’s no cure for high prices like high prices.”

But if canola prices do stay high, pushing for increased canola acres again in 2013, the question becomes, ‘are high prices for canola enough to overcome the agronomic risk of tight rotations?’ That will be the question debated by many farmers over the coming months.

Diane Kleer, Vp production/group publisher, annex Business Media is pleased to announce the appointment of Janet Kanters as editor for Top Crop Manager West.

Janet is a national award-winning writer with over 20 years of professional experience as a journalist, editor, photographer, communications and public relations professional. She was the western field editor for Top Crop Manager West between 1996 and 2005. She brings to this position an in-depth knowledge of provincial, national and international agriculture.

Janet will be working from her home in Strathmore, aB. P • 403.499.9754

E • jkanters@annexweb.com

WeSTerN

meDIA DeSIGNer Katerina maevska vP ProDucTIoN/GrouP PublISher Diane Kleer dkleer@annexweb.com

PreSIDeNT michael Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710 reTurN uNDelIverAble cANADIAN ADDreSSeS To cIrculATIoN DePT. P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Printed in canada ISSN 1717-452X cIrculATIoN e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 211 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SubScrIPTIoN rATeS Top crop manager West - 8 issuesFebruary, march, mid-march, April, June, october, November and December1 Year - $44.25 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, march, April, September, october, November and December 1 Year - $44.25 Cdn. plus tax

Specialty edition - Potatoes in canada - February1 Year - $8.57

Case IH Advanced Farming Systems is dedicated to helping producers be ready. AFS delivers an integrated, less complex precision farming solution, built right in to our equipment using a single display across machines. Built on open architecture, AFS can interface with your existing equipment, no matter what color it is. And our specialists in the field, AFS Support Center engineers and AFS Academy trainers, are there to help you maximize your operation’s potential and keep you rolling 24/7/365. Visit an AFS Certified Dealer or go to caseih.com/AFS to learn more.

by Carolyn King

Fertilizer management strategies can be designed with both the crop and the weeds in mind. Through fertilizer timing and placement, you can inhibit weed growth, reduce dependence on herbicides, and reduce weed populations over time, while increasing crop yield and quality. That’s what research studies on the Canadian prairies over the past decade show.

Many of those studies have been led by Dr. Bob Blackshaw, a weed scientist with a griculture and a gri-Food Canada (aaFC) at Lethbridge, often working with other aaFC researchers for an integrated look at fertilizer-weed-crop interactions.

Blackshaw explains that his initial studies looked at whether weeds even responded to increased fertility. “In some cases there was the perception that weeds are scavengers of nutrients and don’t require a high nutrient load, so fertilizer wouldn’t make much of a difference. That may be true for some weeds in non-agricultural areas, but many of the weeds growing with our crops have either adapted to respond to fertilizer or they are there in the first place because they do respond to increased fertility.”

He conducted greenhouse experiments to assess the response of various weed species to some of the major nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus. “We found a general trend that most species responded positively to those nutrients, and one of the surprises was that some of them responded more than the crops, such as wheat or canola.”

His next step was to carry out several field studies to see how fertilizer placement and timing could be used to help the crop and discourage the weeds.

Apply fertilizer close to when the crop needs it

The fertilizer timing studies compared nitrogen applications

in o ctober and at planting in May, for a spring wheat crop in a zero-till system at Lethbridge. The results showed that, for general weed management, it is usually better to apply nitrogen fertilizer at the time of seeding than in the previous fall. The spring-applied fertilizer treatments tended to have less weed growth and better crop yields.

“We’ve shown that fall fertilizer application can increase the germination of weeds by breaking weed seed dormancy. as well, if your field has winter annual weeds that are germinating in the fall and surviving the winter, then they will be taking up some of that nitrogen,” says Blackshaw. In addition, nitrogen is subject to losses due to leaching, volatilization and denitrification, and a fall application puts it at risk of being lost for a longer period before the crop has a chance to use it.

He notes, “There may be less application of fertilizers in

ABOVE & INSET: Greenhouse experiments to evaluate weed species’ response to phosphorus applications of 0, 10, 20, 30, 40 and 60 kg/ha found differing patterns. For instance, hairy nightshade tended to grow more and more with each increase in phosphorus, while kochia’s growth tended to plateau around 30 kg/ha.

25, 50, 75, 100

the fall than there used to be, but farmers are still interested in it for time management. If they can apply nitrogen in the fall, then it’s one less task to do in the spring. also, in the seeding operation, the first thing farmers have to stop their drill for is to fill their fertilizer tank, not their seed tank. and they don’t want to stop because they have large farms and many acres to cover. [The risk of higher nitrogen losses with a fall application] may be acceptable to them because of the other advantages they see in fall applications.

“But when they factor in all those things to decide on fertilizer timing, they are probably not thinking about weeds at all. Weed management is one more piece of information to consider in that decision.”

In Blackshaw’s fertilizer placement studies, he compared broadcasting on the soil surface, banding three to four inches below the surface and placing fertilizer in the seed row. In comparison to broadcasting, banding reduced the competitive ability of some weed species, especially shallower-rooted species, and it gave the crop seedlings early access to the nutrients.

“Those fertilizer placement studies show that if we could put the fertilizer near to where the crop seed was germinating and emerging – but not too close to the crop seed because that can sometimes cause injury [when higher nitrogen rates are used] – then that gave an advantage to the crop,” explains Blackshaw.

The advantage of banding in comparison to broadcasting is especially true for zero-till systems. He says, “In the zero-till situation, the

weed seeds remain on the soil surface. If we put the fertilizer three or four inches deep in the soil, away from where those weed seeds are geminating, that gives the crop a head start in being able to access those nutrients.”

Blackshaw’s research also shows that some weed species with a high response to fertilizer become increasingly competitive as the fertilizer rate increases, and their growth can be at the expense of crops like wheat, which is only moderately responsive to nitrogen and phosphorus.

The studies also showed that, for a high-nutrient-response weed species, placing the nutrient away from the weed’s germinating seeds can be especially effective in reducing weed growth.

examples of weeds with a high response to nitrogen include redroot pigweed, wild mustard, and lamb’s quarters. examples of weed species that are very responsive to phosphorus include round-leaved mallow and hairy nightshade.

Blackshaw suggests several ways farmers could use such information about weed species response to nutrients. “The first one is to just be aware that some weed species may really like a certain nutrient, and those species could be a greater problem if you apply that nutrient. Then you can do a better job of monitoring those fields and planning your control measures. one example in southern alberta is the

Pioneer® brand D-Series canola hybrids are bred to deliver outstanding performance. D3153 delivers high yield with exceptional standability and harvestability. D3152 adds the Pioneer Protector® Clubroot trait for protection from this devastating disease. And new D3154S has the Pioneer Protector® Sclerotinia trait for built-in protection.

D-Series canola hybrids are available exclusively from select independent and Co-op retailers and are backed with service from DuPont Canada.

Purchases of D-Series canola hybrids will qualify you for the 2013 DuPont™ FarmCare® Connect Grower Program. Terms and Conditions apply.

Lacombe breeding program has gone from the kernel of an idea to a highly productive program.

by Carolyn King

The backing of producers and peter Lougheed provided a great start for alberta’s feed grain breeding program in 1973. now almost four decades later, the program has registered 28 barley varieties, nine triticales and a winter wheat. and it continues to work on making these crops even better for growers and end-users.

Dr. Jim Helm has led the breeding program from the very beginning and guided the development of the facilities, bringing together scientific and technical staff while working with growers to set breeding priorities. along the way, he’s received such prestigious awards as Life Time Membership awards from the Canadian Seed growers association and the alberta Seed growers association in 1998, alberta Science and Technology award in 2001, alberta agriculture Hall of Fame in 2002, alberta Centennial Medal in 2005, and Distinguished agronomist award from the Canadian Society of agronomy in 2012.

Helm’s vision and drive to provide practical benefits for

producers have been crucial to the breeding program’s success.

It all started in 1972 when pork producers persuaded premier peter Lougheed and agriculture Minister Dr. Hugh Horner to create a feed barley breeding program. Helm, a young plant breeder, was hired to head alberta agriculture’s new Feed grain Development program in 1973. He came with over 5000 lines of germplasm from all around the world -- winter and spring barley, winter and spring wheat, and triticale.

The breeding program was initially based at the University of alberta until alberta agriculture purchased land for a research farm near Lacombe. “When we moved to Lacombe in 1977 to start

TOP: Field Crop Development Centre the staff in June 2012, with Helm (in the centre, with the white beard)

INSET: Helm (far right) with Alberta’s Agriculture Minister Verlyn Olson and Deputy Minister John Knapp in July 2012

building the Field Crop Development Centre [FCDC], it was just land that we had bought. We built it from nothing,” notes Helm.

“o ur first planter, our first tractor, our first truck and trailer -- all of that was money put up by livestock producers, primarily the hog producers. Without producer support, we would have never made it. In fact, I think the odds the g overnment had at the time were that we would be lucky to last three years!”

He adds, “I told producers that as long as they continued to support me, I would be here to work for them. and they have supported me and the program over the years, not just with money but politically also.” Currently groups like the alberta Beef producers and alberta Barley Commission are providing support for the program.

The Field Crop Development Centre has come a long way since 1977. Today it is a world-class research centre that includes the research farm, laboratory and cold seed storage facilities in downtown Lacombe, and plant growth facilities at the James H. Helm Cereal research Centre. and while barley breeding programs at many other research centres in western Canada have been discontinued or in decline since the 1980s, the FCDC has increased its breeding staff.

“It took phenomenal effort and foresight to create the Field Crop Development Centre, the breeding program, the facilities. It was Jim’s vision; he was the driving force behind it. What a solid foundation he has laid for us!” says Dr. pat Juskiw, the FCDC’s two-row barley breeder. She notes, “Without Jim, I wouldn’t be here; Dr. Joseph nyachiro, [six-row and hulless barley breeder], Mazan aljarrah [triticale and winter wheat breeder], Dr. Mary Lou Swift [feed quality scientist], our biotech group, our pathology group – none of us would be here if it wasn’t for Jim.”

Helm emphasizes, “ none of this would have been possible without the help of a fantastic team, some who have been with me for over 30 years.” Some of those people include: Dave Dyson, who was invaluable in developing the facility and the program team; the late Dr. Donald Salmon, who was instrumental in advancing triticale; Bill Stewart, lead barley technician who ran the barley breeding program; the late Manuel Cortez, germplasm development scientist; and Stan Hand in research Farm o perations.

Feed grains, especially barley and triticale, have remained the primary focus of the breeding program, but the program now also includes barley breeding for malting and food uses. a significant step forward for barley breeding came in 1993 with the signing of the alberta/Canada Barley Development a greement to develop new barley cultivars for alberta and the peace river region of British Columbia. The agreement is currently between a griculture and a gri-Food Canada (aaFC), alberta a griculture and rural Development (aarD), the alberta Barley Commission and the alberta Crop Industry Development Fund. In terms of research roles, aarD’s FCDC is responsible for variety development and genetic resources, while aaFC focuses on plant pathology, agronomy and field testing.

This agreement isn’t the only area of collaboration for the FCDC. Both Helm and Juskiw emphasize that the breeding program is part of a national effort. The FCDC also works closely

The Field Crop Development Centre’s breeding program emphasizes high-yielding varieties that do well across a range of soil and climate conditions.

with the two other western Canada barley breeding programs, one at the Crop Development Centre at Saskatoon and the other at aaFC’s Brandon research Centre. and it collaborates with a triticale breeding program at aaFC’s Lethbridge research Centre. The breeders test and screen each other’s breeding lines, share germplasm, and exchange ideas and information.

“The real strength of our breeding program has been the introduction of new germplasm for improved yields, disease resistance, and so on,” says Juskiw. For instance, Helm worked closely with Dr. Hugo Vivar at ICar Da – CIMMYT in Mexico, and introduced Vivar’s high quality, disease-resistant barley germplasm into Canadian breeding programs, leading to the release of varieties like Seebe and Vivar. Twenty-two of the twenty-eight barley varieties developed by the FCDC have this international germplasm as a base.

The FCDC’s breeding program has always emphasized development of high-yielding varieties that do well across a diverse range of soil and climate conditions. The varieties released over the years also have a range of additional traits such as early maturity, strong straw, feed value, and resistance to diseases like smut, scald and net blotch.

Juskiw has seen some changes within the overall breeding objectives over the years. o ne example is disease resistance. “Disease resistance has always been a high priority, but the diseases have changed. We didn’t even talk about diseases like fusarium head blight and stripe rust 20 years ago because they weren’t here. But now they are prevalent, so they are in our breeding objectives.”

For Darcy Kirtzinger, policy and research Coordinator for the alberta Barley Commission, one of the program’s key aspects is that it develops varieties to meet the needs of both growers and end-users. “Through Jim’s leadership over the years, he knows everyone in the industry, and he understands the requirements of the different end-uses – feeding, malting, human food and different niche markets, like shochu. and he has constantly been in touch with alberta farmers through the Barley Commission to ask: is this the direction you want me to be going

While every farmer dreams of amazing yields, not all realize the fertilizer they use is responsible for up to 40 percent of yield. So it makes sense to use the most advanced fertilizer available. Choose MicroEssentials®, with FusionTM technology. Every granule offers perfect distribution of nutrients for uniform coverage, and improved nutrient uptake. For more information, visit MicroEssentials.com, or contact your Richardson Pioneer Ag Business Centre.

in? He’s got committees within the breeding program that take input from all the different groups and then he incorporates that into the program objectives.”

Selection of breeding material has been advanced through the use of near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy ( nIr S), a tool to rapidly measure feed and malt quality. Helm has been at the forefront of the use of nIr S in agriculture, pioneering its use in breeding programs and in feed testing, and working to develop accurate calibrations of the technology for different quality traits.

nIr S uses near-infrared light to scan a whole grain sample. The data from the scan is related to data from traditional evaluation techniques, like chemistry tests or feeding trials, to predict quality characteristics. although nIr S requires careful calibration, it offers a lot of advantages over those traditional techniques.

“p lant breeding, in a way, is like playing roulette – the more numbers you cover, the better your chances are that you’re going to win. Using nIr S for quality analysis instead of going through the very expensive and long process of using wet labs for everything gives us a better chance of finding those lines that will be the winners,” says Helm. “Without nIr S, you could take a maximum of about 2000 lines a year through a lab for malt quality because you have to malt each sample and then run it through all of the quality analyses. With nIr S, we’re evaluating over 40,000 lines a year in our program.”

The varieties released by FCDC and the other barley breeding programs have provided many benefits, including contributing to the upward yield trend. For instance, in 1973 in alberta, barley yielded an average of 39.0 bushels per acre. In 2011, it yielded 67.0 bushels per acre.

according to Helm, several studies have assessed the economic impacts of the FCDC’s breeding program. For instance, a study in 2002 found an internal rate of return of nearly 30% on the investment in FCDC’s feed barley development program from 1973 to 2001. another study estimated that the program’s impact to farmers was over $5 billion in 2005, and the benefits have likely grown since then. The rest of the barley value chain – from crop input suppliers, to the trucking, feeding, processing, and retailing sectors – also gains economic benefits from varietal improvements.

o ne small example of the program’s benefits comes from Mastin Seeds in Sundre, alberta. Mastin Seeds is the distributor for Sundre barley, a variety bred by the FCDC and registered in 2006. This smooth-awned, six-row barley has high grain and silage yields, strong straw, good kernel plumpness and scald resistance. Sundre barley was the first variety that Bob Mastin bid on when he became a seed distributor, and its success helped get his business off to a good beginning.

“That little variety has done more for me than I could ever imagine. It looked good when I applied for it, and it has turned out to be even better,” says Bob Mastin. not only has Sundre barley been very popular in western Canada, but he says the russians have found that it performs very well in their conditions and it is now a registered variety in russia. Sundre barley also appears to have good potential for the Japanese barley tea market.

Mastin currently distributes varieties from various breeding programs, including several other FCDC varieties. He notes, “I’m impressed with the quality of the people at the Field Crop Development Centre, the quality of the breeding, and what they have in the pipeline for the future. It’s a world-class breeding institution.”

Breeding programs need to set their breeding objectives to suit the conditions that will exist in about 10 or 20 years because it takes many years to develop a variety. Trying to predict the future is a big challenge, especially these days.

Plant breeding, in a way, is like playing roulette – the more numbers you cover, the better your chances are that you’re going to win.

“I think the real challenge ahead for the program is to adjust to what the market changes will be. The Canadian Wheat Board is not a single desk any more. How will that change things? are we going to see more feed wheat, or is barley still going to have a role there? Will triticale still have a place, especially for the work we’re doing in swath grazing?” asks Juskiw.

“and what will happen in the livestock industry? It’s really challenging right now with the drought in the U.S. What about biofuel production? Biofuel was very strong at the beginning of this century, but now people saying biofuels are taking away from food production and asking if that is viable in a world that will soon have 9 billion people. and where is our climate taking us? How do we best respond to extreme weather conditions? How long will our growing season be in 20 years?”

The Barley Commission’s Kirtzinger notes, “We really don’t know the impact of the open market just yet on barley. Certainly a lot of world forces are at play affecting the volatility of grain prices. I don’t know how that will play out in terms of the future for barley here. We’ve seen some declines in barley acreage over the last five years in western Canada, and whether or not farmers will see enough incentive to grow more barley or to grow other grains at the expense of barley, it’s too early to tell.”

From Helm’s perspective, one of the biggest challenges ahead for all crop production is that very few young people are going into crop breeding in Canada and worldwide. “I know of crop breeding positions that have been open for two years, internationally, and they can’t find people.… everything has gone to the biotech side of things, and nobody has been training practical plant breeders, people to be in the field and look at it from the viewpoint that the farmer will look at it down the road.”

However Helm sees some intriguing prospects ahead as well. “When I started, we were way ahead of the medical field in terms of genetics and understanding things like disease resistance. now the medical field has moved way ahead of us. Some of their advances will relate to other living things like plants. I think we could learn a lot from each other if people in the medical field and people in the plant field would start talking to each other. That’s where I think there is huge potential: getting young, smart and interested people working on the molecular biology behind disease resistance in crops.”

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 8

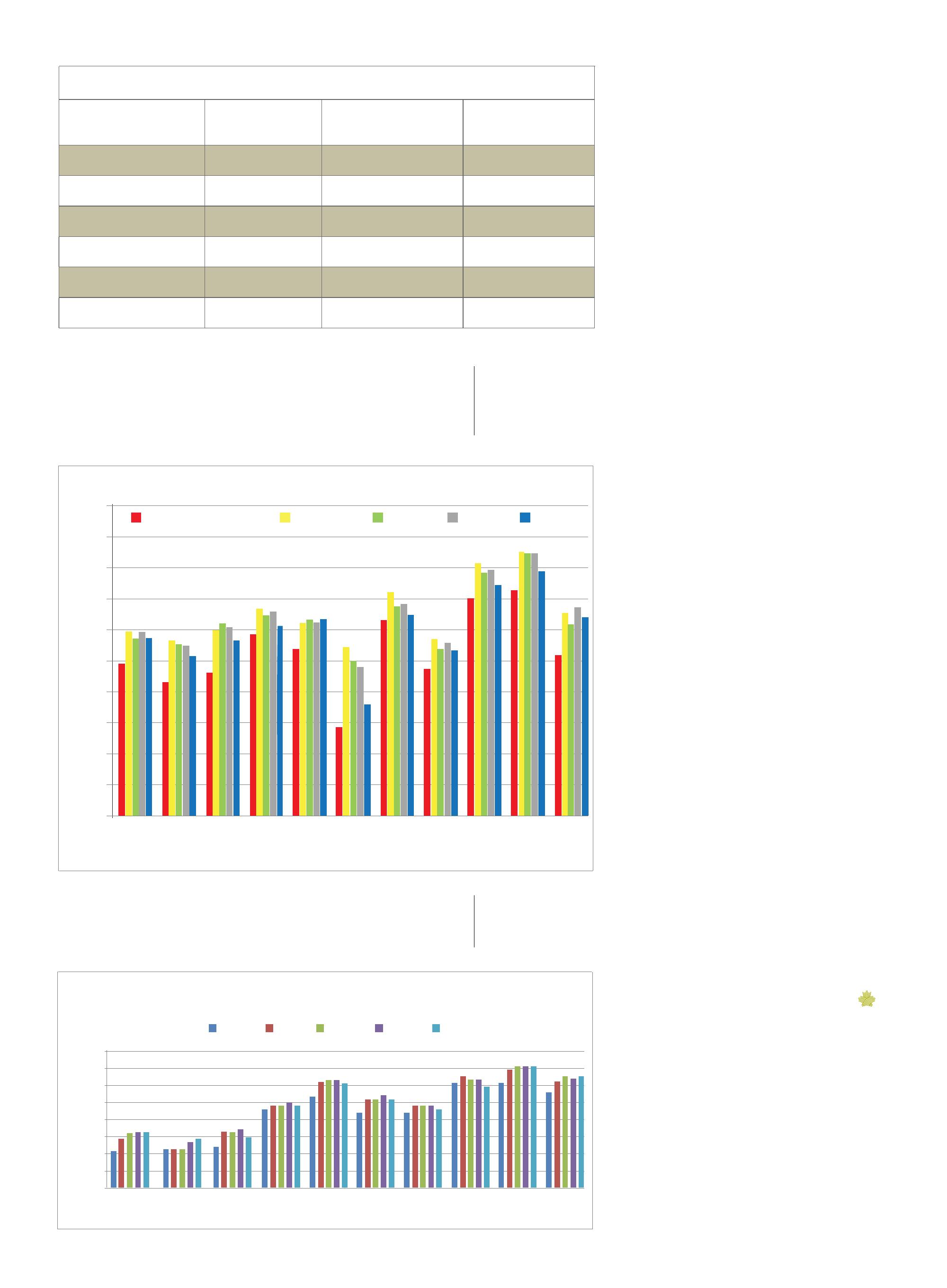

Weed seedbank at end of 4-yr study – N placement

After four years of nitrogen applications, the weed seedbank is much larger for surface broadcasting than for the subsurface placement options.

spreading of manure from the feedlot industry. Manure is reasonably high in nutrients but it’s especially high in phosphorus. When manure is spread, some of these species that respond highly to phosphorus have a tendency to take off in those fields.”

He notes, “a second option is that, if you know you have that weed in your field, then you could think about the best way to disadvantage it in terms of the nutrient. That might involve how or when you apply your fertilizer.”

another possibility, if you’re dealing with high-nitrogen-response weeds, is to grow a legume crop, such as peas or lentils. “The legume crop would fix its own nitrogen, so it would be getting nitrogen. and you wouldn’t be applying any nitrogen fertilizer in that case, so the weeds wouldn’t be able to get the nitrogen,” explains Blackshaw.

“It was very consistent in all of our studies with nitrogen and phosphorus that the big advantage is if you do the practice for several years in a row,” says Blackshaw. “Maybe you saw only a small effect in the first year, but it was more in the second year, more in the third year, more in the fourth year.”

That is, if your fertilizer practices disadvantage a weed species in one year, then those weeds will be smaller and produce much less seed, so there will be less weed seed to germinate in subsequent years. If you continue to disadvantage that weed species year after year, you can have a significant effect on the weed seedbank.

He adds, “Many of these non-chemical weed control methods [such as fertilizer management practices, crop rotations and higher seeding rates] do not have as big an effect on weeds as herbicides, and their real power is sometimes not evident until several years after you switch to that practice.”

by Carolyn King

In the old fairy tale, rumpelstiltskin spins flax straw into gold. o n the Canadian prairies, o pen Mind Developments is transforming flax straw into eco-friendly i p hone cases. This innovative idea could blossom into a much bigger opportunity for the Saskatoon-based company, and help augment efforts to grow the flax fibre industry in the province.

Flax’s tough, durable straw can be a residue management challenge for oilseed flax growers. The straw is slow to break down and the long fibres can get tangled around field implements. In the past, growers usually burned the straw. Fortunately there are other options these days, including some opportunities to sell the straw.

Developing value-added opportunities to use flax straw offers economic, environmental and societal benefits, explains Linda Braun, executive director of the Saskatchewan Flax Development Commission, or SaskFlax. “If we look at the economics from a producer’s point of view, complete plant utilization adds increased net returns per acre for his flax crop. a second economic reason is that new farmers are hesitant to grow flax because dealing with the straw can be a challenge. When the process becomes more profitable, farmers become more interested and are willing to adapt some of their harvest practices to realize the value of that straw.

“From an environmental perspective, we’re seeing around the globe a very growing trend to use biological, biodegradable, renewable products, from natural fibres in the plastics industry to textiles to the auto industry. Flax fibre is both strong and light so, for example, the auto industry is interested because using it in car parts makes the vehicle lighter, which helps increase gas mileage ratings. By incorporating those fibres, the auto industry uses something renewable and also decreases pollution.”

From a societal viewpoint, Braun says developing the flax fibre industry in Saskatchewan would increase job opportunities in businesses along the value chain, ranging from custom baling and transport, to primary processing companies, to secondary processors, like o pen Mind.

o pen Mind president Jeremy Lang came up with idea for the phone cases: “I have a bachelor of science in agriculture from the University of Saskatchewan, and I’ve always thought flax fibre was neat and I thought it was a shame that the straw often gets burned in the fields. I also knew that bioplastics are made from biopolymers, which are made from plants, while conventional plastic is derived from crude oil. But currently, biopolymer products aren’t typically made to be tough; they are made into single-use items like utensils.

“So my idea was, instead of burning the flax straw, to add it to biopolymers to add strength to them and to give them a unique appearance.”

Lang was able to get some funding assistance from the Canadian a gricultural adaptation program and the Saskatchewan a gri-Value Initiative for a feasibility study and a business plan for his unique concept. He has developed a proprietary formula for mixing flax fibre and shive (the non-fibre part of the flax stem) with biopolymers to create a distinctive-looking, ecofriendly bioplastic, with the trademarked name Flaxstic.

To make Flaxstic, o pen Mind uses flax straw grown in Manitoba and Saskatchewan and processed by Biolin research in

Saskatchewan and Schweitzer-Mauduit Canada in Manitoba. The biopolymers come from the United States. according to Lang, “The biopolymers are made from annually renewable, non-food source plants. They have a smaller carbon footprint than conventional plastics.”

The case for the i p hone 4 and 4S is o pen Mind’s first product made from Flaxstic. “I wanted to start with a very simple product that could showcase the technology, to prove that it can be done. The i p hone 4 cases are simple, and they require only a small amount of the biopolymer, which is our big cost. and ip hones are purchased by a demographic that we reach very easily with online marketing,” explains Lang.

o pen Mind markets its phone case under the product name pela. Lang says, “The Spanish word ‘pela’ loosely translates as ‘peel’, so the phone case is like an apple peel, or a natural peel or cover for your apple product. and like an apple peel, it biodegrades and goes back to the earth. and our logo for pela is a crosssection of a flax seed capsule, a pentagon shape with 10 seeds in it.”

o pen Mind’s first version of the pela case came out in September 2011. It was a hard, form-fitting case. Since then,

the company has been working with different biopolymer manufacturers to improve the biopolymer to meet o pen Mind’s specific needs.

So now o pen Mind has a new, improved case. “In September 2012, we’re launching a new pela case for the i p hone 4 and the i p hone 5. It is a soft case, almost like a rubber. It’s a better designed, more protective case, and it’s backyard compostable. We’re pretty excited about that,” says Lang.

So far, the phone cases have been available online (pelacase.com) and in SaskTel corporate stores in Saskatchewan. Lang is working with distributors in Vancouver and Toronto to get the product into more stores when the new case is released.

Lang sees the potential to use Flaxstic for a lot more than phone cases.

“My plan is to promote using Flaxstic to distinguish bioplastic in the marketplace and help separate it in the recycling stream. So any eco-friendly, biodegradable, compostable bioplastic would have a natural flax shive in it to give a special look,” he explains.

“Separating bioplastic from regular plastic in recycling facilities is impor-

tant because bioplastic needs to be treated differently than regular plastic, so a product made from biopolymers can’t get mixed in with regular plastic. There has been a lot of money spent on trying to figure out an easy way to separate it in the recycling stream, like using nearinfrared technology. g iving bioplastic a distinctive appearance would help to separate it.”

Lang adds, “That special look is also how we’re trying to stand out in the marketplace. There are a couple of other eco-friendly i p hone 4 cases made from biopolymers, but they look just like regular plastic. o ur idea is, if it’s going to be eco-friendly, then it should look ecofriendly, so people rethink plastic and help to promote the use of more sustainable plastic and products.”

This fall, o pen Mind will be increasing its efforts to market Flaxstic to other industries, like companies that manufacture shampoo or detergent containers, sandals, consumer electronics and pet products. Lang says, “We’ll be able to manufacture other people’s products with Flaxstic or license the formula to other industries.”

“We use Jeremy Lang’s i p hone cases as speaker gifts for a lot of our events,” notes SaskFlax’s Braun. “It’s Saskatchewan-made, it’s easy to take home if you’re flying, it reminds you of innovation, and it’s a great example of what you can do with flax straw.”

She believes Saskatchewan has the potential to lead the agricultural fibres industry in Canada. “We grow the most flax, and we have the potential to increase net returns to growers. We have the potential to develop successful primary processing facilities, and there’s a whole host of value-added businesses coming forth, like o pen Mind Developments, naturally advanced Technologies, which has a technology for using flax and hemp straw to produce fibres, and advance Fibrenomics, which is looking at setting up a plant early in 2013 to use natural fibres in building products like insulation.”

Through a number of initiatives, SaskFlax is working on developing the feedstock portion of the flax straw value chain. Braun highlights some examples.

Flax shive, the non-fibre part of the flax stem, can be used for things like mulch, animal bedding, and filler in plastics and bioplastics.

For instance, the producer group has undertaken research to determine the percentage of fibre in various flax varieties. Braun explains, “For example, if you live in an area in southeast Saskatchewan where we currently have buyers for flax straw, you could grow varieties with a higher fibre content in the straw. If you’re in an area where there is no po -

tential to sell the straw, then to make life easier with your chopping equipment, you could plant varieties with very low fibre.”

another example is SaskFlax’s effort over about the past 10 years to develop flax fibre and shive standards under a STM International, a globally recognized voluntary standards organization.

SaskFlax has developed standardized terminology and standard testing procedures for things like fibre colour and fineness. “The development of these standards will help secondary manufacturers understand what our flax fibres can do, and then we can give them specific fibres for specific tasks. …It will help the value-added players understand how flax can fit into their product development,” explains Braun.

The producer group is also working with a Quebec manufacturing company. This project involves testing ways to manage flax straw so the fibre can be used for clothing, a high-end opportunity that requires ‘retting’ in the field by the grower. retting involves having the straw come in contact with the soil so soil microbes will slightly decompose the straw, causing the fibre to start separating from the shive. SaskFlax is comparing various treatments to prepare the straw for retting. Then the retted straw from the treatments will be sent for processing and the resulting fibres will go to Quebec where some spinners and fabric makers will test them to see if the fibres might meet their needs.

These types of initiatives and the efforts of innovative entrepreneurs like Lang are all part of advancing the flax straw value chain and providing flax growers with more opportunities for complete plant utilization.

5525 CL is a yield-leading variety in all canola production systems, delivering outstanding net returns while you retain complete marketing flexibility. Head-to-head in the 2011 Canola Performance Trials mid-season zone, 5525 CL out-yielded Nexera® 2012 by an average of 8 bu/ac1. The result: $50.361 per acre more in farmers’ pockets even after specialty oil premiums. With the freedom to market 5525 CL anywhere, and high net returns, 5525 CL crushes the competition.

In the end, it all comes down to performance and BrettYoung brings a new standard of excellence to the field.

CWB offers a canola pool for the second largest crop in western Canada.

by Carolyn King

Although the Canadian Wheat Board – now known as CWB – has lost its monopoly for marketing wheat and barley with the recent Marketing Freedom for Farmers act, CWB has gained the freedom to market any crop. So on august 23, 2012, it announced its first canola pool.

“We have been hearing for some time, even back over the last few years, that some groups of farmers were keen to see the Canadian Wheat Board get involved in canola. now that the market is open in terms of our freedom to be involved in other crops, we feel canola is a good choice,” explains Ian White, CWB president and Ceo.

“Canola is the second largest crop in western Canada. running canola pools is very similar to running our wheat and barley pools, which is something we are very used to, so we felt we could be effective. and we felt we had a good fit with a range of customers that we currently service for wheat that were quite prepared to talk to us about canola.”

CWB’s pool return outlook is $640/tonne ($10.77/bushel) for number 1 canola, and $627/tonne ($10.48/bushel) for number 2. The initial payments for farmers are: $475/tonne for number 1, and $462/per tonne for number 2.

“our initial payments with all our pools will be about 75% of what we see as the expected pool return at that time,” notes White.

The sign-up deadline for the canola pool is october 31, 2012, with a marketing period that runs to June 30, 2013. CWB doesn’t own any grain handling facilities; at present it has 42 farmer delivery points for canola, negotiated with parrish & Heimbecker and

some smaller independent companies, but it hopes to add more locations. (CWB has already reached handling agreements for wheat, durum and barley with all the western Canadian grain companies.)

With the recent legislative changes, farmers must negotiate directly with the grain handling companies regarding the company’s fees for things like freight and handling of CWB-contracted crops. (Farmers who have been marketing their own canola will be familiar with canola prices that are based on the futures market minus the company’s local basis. The basis typically includes costs for things like handling, transportation, storage, hedging and a profit margin for the company.)

David Wong, a grain and oilseed market specialist with alberta agriculture and rural Development, explains the pooling concept: “a pool tries to capture an average of the prices, so you don’t get superpremium prices but you don’t hit the lows either. and hopefully you’ll get a slightly higher return than the average price because whoever is administering the pool will be looking for a good price when they start moving the canola.”

White says, “The canola pool is another option for farmers in terms of risk management. rather than a farmer taking a cash price, and trying to pick the day to take the cash price, the pool offers the

Nodulator® XL inoculant drives your pea and lentil yields straight into the big leagues – for a championship Return on Investment.

When you inoculate with Nodulator ® XL, it unleashes a unique, more active strain of rhizobium for enhanced nitrogen-fixing within nodules and more vigorous plant growth. That means higher yields and a Return on Investment that crushes the competition.

Nodulator® XL is registered for both peas and lentils, with your choice of formulations: liquid, self-adhering peat or solid core granule. Want to go big? Grab the Nodulator® XL Q-Pak – a convenient 364 kg (800 lb.) soft-sided tote that’s perfect for larger operations.

opportunity to take a range of prices over time. Hopefully they will do as well as or better than they would if they followed the cash market.”

“I think anything that gives farmers an option is a good thing, including this canola pool,” says Brett Halstead, a Saskatchewan producer in the nokomis area and Board Chair of the Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission.

He adds, “Some people aren’t comfortable with doing the marketing or pricing. a canola pool allows them the option to have a group with some expertise do it, so they can concentrate more on production.”

CWB has over 75 years of experience in grain marketing, and it sells grain to over 70 countries. although canola is a new grain for CWB, it has been preparing for this opportunity. White says, “over the last couple of years, we had done some work on canola. We wanted to understand the relationship between prices being of-

fered to farmers and the futures markets. But that’s a very natural thing for us to do in terms of hedging wheat and barley, and we were able to decide that it was quite manageable.”

Starting in about June 2012, CWB began buying canola from handlers and processors and selling it. “We felt that would be a good way to start in the business. We saw opportunities to make canola sales and then investigated to see if there were opportunities to buy it to match those sales, and we found that there were. So we have traded some canola to some of our longstanding customers,” says White.

Wong notes, “Compared to a wheat pool, a canola pool should be much simpler to administer. Typically we only have two grades of canola, number 1, which is about 80% of alberta’s canola, and number 2, which is about 20%, barring those years when we have really bad fall weather. With the wheat pool, you can have up to four different grades and seven protein levels for

each of the top three grades.”

one of the challenges for CWB is to predict the degree of producer participation in the canola pool. “There is some level of unknown because it’s the first time a canola pool has been offered and it’s our first foray into the business,” notes White.

Wong says, “I guess one challenge with all the CWB pools, including the canola pool, is that we’re in a wait-and-see and learn-as-wego type of situation. We’re not sure how this will all settle out in the end, mainly because CWB has no grain handling facilities. also, if you sell canola directly to a handler or a processor, you know what price you’ll get right away, because you know what the futures price is and what the basis level is.”

Halstead isn’t sure how popular the canola pool will be. “In our area, we have three fairly competitive grain companies bidding for canola. one of them is parrish & Heimbecker, which is also [taking delivery of CWB canola]. everybody makes up their own mind. I’m

sure some will choose the canola pool. In other areas where people are more into producer cars, the pooling option may be bigger. and it depends on each individual producer’s cash needs too.”

producer cars – railway hopper cars that are loaded by farmers – have become increasingly popular in recent years as an alternative to using an elevator. The application procedures for a CWB producer car contract for canola are the same as those for wheat and durum. according to CWB’s website, “Due to the anticipated logistics of the canola pool, producer car opportunities may be limited in some time periods and circumstances.”

Looking ahead, White says, “Canola is a good first additional crop for CWB. We think we’ll be able to add value to farmers here and we hope to get good support from them. We also are looking at what are the next things that we as an organization should be doing in terms of marketing and we’ll assess those in terms of other crops as we go down the track. We’ll see how the canola pool goes first.”

by Carolyn King

By including both organic and non-organic systems in a recent study, prairie researchers have been able to add a few more pieces to the complicated puzzle of how to control root and crown rots in wheat.

root and crown rots of cereal crops have been increasing in the western prairies over the last decade. “For example in the last few years, and especially in 2012, there was a lot of root rot in the fields, particularly in durum wheat, because of the dry conditions. The pathogens are always there [in the soil], and the plant is always defending itself. But with dry conditions during plant development the plant is stressed, so the infection affects the plant and the symptoms show up above ground,” notes Dr. Myriam Fernandez, a plant pathologist with a griculture and a gri-Food Canada (aaFC) at Swift Current, Saskatchewan.

She led the study, which was published in a gronomy Journal in 2011. Her co-authors on the paper were Dan Ulrich, Stewart Brandt, Dr. robert Zenter, Dr. Hong Wang, Dr. g ordon Thomas and Dr. o wen o lfert, all from aaFC.

Wheat plants infected with root and crown rots have brown

to black roots and crowns. above-ground symptoms may include patchy emergence, stunted or dead seedlings, tillers with few seeds, dead tillers, and prematurely ripened spikes called whiteheads. Yield loss can be significant when the symptoms are severe.

Fernandez explains that root and crown rots in wheat can be caused by various fungal pathogens. o n the prairies, Cochliobolus sativus (also known as Bipolaris sorokiniana) and several species of Fusarium are the main causes.

root and crown rots, along with forming a widespread and damaging disease complex, were also of interest to Fernandez because of the link between Fusarium inoculum in the roots and crowns and the spread of fusarium head blight (FHB). FHB is a devastating disease that can produce toxins that limit the grain’s end use.

“o ne of the main Fusarium species we were seeing in the

Non-resistant 55% infection

Resistant 13% infection

Sclerotinia can be a costly disease for canola growers. Lost revenues exceeded an estimated $600 million in 2010, in a year when conditions were favourable for development of the disease. While the numbers are not all tallied yet, for many areas of the Prairies incidence of sclerotinia in 2012 was higher than we have seen in quite a few years.

Management approach

1. Crop rotation

2. Final plant population of 6–10 plants per square foot

3. Sclerotinia resistant hybrids

4. Foliar fungicide

In 2012 sclerotinia incidence was worse than 2010 and far worse than 2011. Southeast Saskatchewan experienced much higher incidence than the south-central parts of the province. Seeding date also had a huge effect on levels of incidence.”

Dave Vanthuyne, DuPont Pioneer agronomist for central and southern Saskatchewan

Pioneer Protector ® canola hybrids

45S54 45S52 46S53

Exclusively available from our Pioneer Hi-Bred sales representative

“As far as incidence and severity, 2012 has been the worst I have seen for sclerotinia since 2007. I saw ranges of incidence from less than 5% to as high as 60% in fields. Some of the fields were sprayed and still had levels in the 30% range.”

Doug Moisey, DuPont Pioneer agronomist for central and northern Alberta

Sclerotinia resistant hybrids

DuPont Pioneer, a leader in canola genetics, provides the first and only canola hybrids with built-in sclerotinia resistance on the market. The Pioneer Protector ® Sclerotinia Resistance trait is built right into the seed so the risk of sclerotinia infection is greatly reduced.

The Pioneer Protector® Sclerotinia Resistance* trait provides these benefits to growers:

Reduction in incidence

Greater than 50% reduction in sclerotinia incidence.

Peace of mind

Increased flexibility and insurance when timing fungicide applications.

Convenience

Sclerotinia protection is planted with the seed.

Season-long control

An in-plant trait that provides coverage regardless of weather patterns throughout the entire growing season.

roots and crowns was Fusarium avenaceum, which has been the most common Fusarium species on heads in Saskatchewan when we do our annual disease surveys,” says Fernandez. These surveys are a joint effort co-ordinated by Saskatchewan a griculture, with commercial fields across the province sampled by Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation staff.

She notes that Fusarium graminearum, the main pathogen responsible for FHB in areas where this disease occurs at high levels, can also infect roots and crowns of wheat. However, the Scott area is not prone to FHB and Fusarium graminearum was not found there by the researchers.

a gronomic practices are important for managing root and crown rots because current wheat varieties do not have good resistance to the disease complex. Fernandez and her colleagues had already done some research on the effects of crop rotation and tillage system in non-organic systems, mostly at Swift Current, which is in the Brown soil zone.

“We had already determined that using reduced tillage and having pulses in the rotation increased the amount of the Fusarium species in the roots and crowns, whereas the levels of Cochliobolus sativus, which is the main pathogen in root rot, decreased. also there was very little Fusarium infection, for example, with wheat after summerfallow, but there was a lot of Cochliobolus sativus,” she notes.

Then Fernandez got an opportunity to carry out a six-year study of root and crown rots in spring wheat as part of a longterm cropping systems experiment at aaFC’s Scott research Farm, in the Dark Brown soil zone. e stablished in the mid1990s, this experiment includes three input systems – an organic system, a reduced input system and a high input system – and three types of crop rotations.

Looking at the root and crown rot problem from an organic angle interested Fernandez for several reasons. “There had not been any similar studies in north america on the effect of organic systems on root and crown rot; the only studies we found were from e urope. We also found publications indicating that fusarium head blight was less common under organic systems than conventional systems, pointing to a very likely effect of an organic versus a non-organic system on Fusarium infections in roots and crowns.”

at Scott, the organic system involved intensive tillage and no chemical inputs. The reduced input system used reduced tillage with targeted fertilizer and weed control inputs. The high input system involved intensive tillage and recommended rates of fertilizers and pesticides. o riginally it was thought that the chemical inputs for the reduced and high input systems would be distinctly different from each other, but they turned out to be fairly similar, demonstrating that the tillage system was the key difference between the reduced and high input systems. The high input and organic systems had similar tillage levels.

The crop rotations included a low diversity rotation, a diversified rotation with annual grains, and a diversified rotation with annual grains and perennial forages. “However, we didn’t really find much of an effect of the crop diversity factor on root and crown rots,” says Fernandez. “The greatest effect was in terms of the input system.”

In particular, the researchers found the input system had

SALFORD equipment combines efficient operating speeds,multiple applications in one pass and durability to maximize your time in the field and help you cover more acres,fast. SALFORD equipment helps maximize yield potential through effective residue, soil moisture and seedbed management, improving seed to soil contact,germination, emergence and early plant growth.

equipment is

and manufactured to excel in a variety of field conditions, with models built to suit any size farming

quite a significant impact on the proportions of the different pathogens.

For Cochliobolus sativus, the organic system tended to have the highest levels of this pathogen, and the reduced tillage system tended to have the lowest levels.

For Fusarium, the impact of the input system depended on the species. The organic system had the lowest levels of Fusarium pathogens, particularly Fusarium avenaceum and Fusarium culmorum. However, it had the highest incidence of Fusarium equiseti, which is a weak pathogen. o ther studies have found that Fusarium equiseti competes with the more pathogenic Fusarium species.

The reduced tillage system had the highest levels of Fusarium avenaceum, and lower levels of Fusarium equiseti.

The high input system tended to have intermediate levels of the Fusarium pathogens, but low levels of Fusarium equiseti.

Fernandez notes, “It has been suggested by other people that, because of the higher microbial diversity in organic systems, there could be more competition, and that could result in an increase

of Fusarium equiseti. But we don’t know the mechanism by which the Fusarium pathogens are decreased in organic systems, whether it’s by direct competition or some other mechanism. We are in the process of looking into that.” potentially this new research might, in the long term, lead to identification of agronomic practices that would help increase levels of Fusarium equiseti in the soil and contribute to the control of important Fusarium pathogens.

The results from the study at Scott have also underlined previous findings that Cochliobolus sativus and Fusarium pathogens seem to thrive under somewhat opposite conditions. That is, when the Cochliobolus sativus levels are high, the levels of the Fusarium pathogens tend to be low, and vice versa. In fact, some earlier studies showed that some type of competition occurs between Fusarium pathogens and Cochliobolus sativus. So Fernandez is doing some field and greenhouse trials to try to pinpoint how the various Fusarium species and Cochliobolus sativus interact and affect each other.

The study at Scott has led to yet another spinoff – it has helped inspire Fernandez and other western Canadian researchers to initiate the first organic research program in the Brown soil zone of Saskatchewan. They are working closely with organic producers to make sure the studies are relevant.

Controlling root and crown rots isn’t easy, especially given the seesaw between Cochliobolus sativus and the Fusarium pathogens, with some agronomic practices decreasing one while increasing the other.

Fernandez sees the Fusarium pathogens as the greater problem. “a s I look at the spread of fusarium head blight, which was something real that happened this summer, I would be more concerned about Fusarium in roots and crowns than Cochliobolus sativus.” although Cochliobolus sativus can also cause blackpoint, that disease requires wet weather during kernel maturation to cause serious problems, and it does not produce toxins – unlike FHB.

PROTINUS® seed-applied fertilizer delivers a nutrient boost that gives you faster emergence, larger seedlings and bigger roots. And a stronger start means you can look forward to stronger results at harvest. Use the technology that’s light years ahead. Ask your retailer for PROTINUS or visit PROTINUS.org.

She adds, “In an area that is prone to fusarium head blight, you might not see FHB in a dry year, but you could still have Fusarium inoculum in the roots and crowns, which would be carried over from one year to the next. a nd it would be in the crop residues too – Fusarium species are very competitive in dead tissue, so right after harvest the fungus starts spreading throughout the residues.” a s a result, high levels of Fusarium species would be in the environment, ready and waiting for the warm, moist conditions that favour development of FHB.

a ccording to Fernandez, three key factors that tend to increase Fusariumcaused root and crown rots in a field are: using reduced tillage, growing durum in the rotation and growing pulses in the rotation. She notes that all crops, including oilseeds, are susceptible to the fungi that cause root and crown rots, but pulses are the most susceptible to Fusarium avenaceum. Durum is generally more susceptible than other wheats to root and crown rots.

Fernandez doesn’t advocate that reduced tillage producers go back to intensive tillage. But she suggests that if producers are facing high levels of root and crown rots, they might consider temporarily changing their rotation by switching from durum to some other crop and/or, by avoiding pulses, trying to reduce the levels of Fusarium avenaceum in the field.

Important tips that apply to most types of small grain storage.

by John Dietz

Fans blowing air through grain in storage may, or may not, be doing the work they need to do. engineers at the prairie agricultural Machinery Institute (paMI), Humboldt, Saskatchewan, took a fresh look at the whole process of conditioning grain in storage over the past few years, and came up with some fresh advice.

Joy agnew is project manager for ag research at paMI-Humboldt. The engineer recently completed a study that began in 2007 on conditioning stored grain on farms.

For starters, the shape of the top of the pile inside the bin does matter, agnew says. It affects the distribution of the air moving through the grain.

It’s a non-issue if the grain is dry and cool, but if the grain is too warm, too damp or too dry and needs conditioning, don’t pile it up and don’t fill the bin beyond the eave. It should be close to level before the air is turned on.

generally, air moving up from the bottom forms a slow-moving “drying front” inside the bin as it pushes moisture up and out.

“When it’s allowed to cone up, that will increase the amount of time required to get the drying front to move through,” she says.

“The bin that’s filled into the top cone has the most grain, the greatest depth and the smallest surface area to release air and moisture. above the eve, the hatch at the top is the only place for air to escape.”

The depth of the grain is important. paMI found extension documents stating fan horsepower requirements in terms of volume without reference to grain depth. That’s misleading because, in fact, static pressure determines the required fan size – and depth is the primary component in static pressure.

“Tons of guidelines show the fan size based on bin size,” agnew says. “In reality, fan size should be based on grain depth. Static pressure depends more on depth than volume.”

For example, she says, a three-horsepower fan usually can provide natural air drying for a 3,000-bushel bin that’s holding 10 feet of grain. However, it takes a five-horsepower fan to do the same job if the bin is narrower and an equal amount of grain is 15 feet deep.

a simple device called a manometer will measure the static pressure inside a bin as a fan pushes air through the pile.

“Static pressure is fairly simple to measure yourself,” agnew says. “You can purchase manometers from fan suppliers, or you can rig one yourself.”

Building a manometer requires a piece of flexible transparent quarter-inch tubing, duct tape, a short ruler and a board. The Saskatchewan Ministry of agriculture factsheet, Natural Grain Drying, has instructions on building your own manometer.

TOP: Aeration or natural air drying is dependent on properly sizing your fan and ducting.

ABOVE: The fan was only on 45 percent of the time, and that includes the three or four days when it ran almost continuously trying to rewet the grain at the bottom. Notice that the ambient air usually had the potential to dry between 10 a.m. and 10 p.m.

The pressurized end of the tube is attached in the transition duct inside, between the fan and the distribution system. The other end is mounted outside on the board, vertically, so that the whole tube, if you could see it in profile, would be U-shaped.

Then, without operating the fan, pour water into the open end of the tube so that the tube is sealed inside by the water. p ut a mark at the base level and do one-inch marks above that for about 10 inches.

partially fill the bin. Turn on the fan, and pressure will build inside the transition duct. The pressure pushes water up the manometer and is measured in inches of water column. Count the marks to read the static pressure.

“a s you’re filling the bin keep an eye on the manometer. If you know your fan puts out 2,000 cfm at five inches of water column, then you fill the bin until you get five inches of water column pressure. You’re guaranteed to have 2,000 cfm and you can determine the flow rate depending on the number of bushels in the bin,” she says.

There are two flow rates in use for similar purposes, which leads to a lot of confusion in discussions and documents, the engineer says.

aeration (cooling) can be achieved with an airflow rate of 0.1 to 0.2 cfm/bushel. If the air is cooler than the grain, the grain will cool. This is a slow process that’s fine if the grain is warm but dry.

natural air drying uses 10 to 20 times the fan power to actually dry the grain, at about 1 to 2 cfm/bushel.

However, the metric standard for aeration (1-2 L/s per m³) has the same numerical value as natural air drying (1 to 2 cfm/ bushel).

“people say aeration is one or two, but what are the units? When you don’t put the unit factors into a document, or discussion, you don’t know what they’re talking about,” she says.

The pa MI team also learned that many people don’t really know the difference between aeration and natural air drying.

The fundamental different is airflow rate. aerating only attempts to cool the grain to get it to a safe storage temperature. It can be done with a very low flow rate and little fan power. The only issue of concern is that the air outside is cooler than the grain.

natural air drying uses much more power and relies on capacity to dry as air moves through the grain. The issues are more complex, with moisture content replacing cooling as the main concern.

JOy agNeW, PaMi

“Moisture movement from grain to air is very slow when the air temperature is less than 10 degrees, so natural air drying is not recommended below 10 degrees,” a gnew says.

“adding heat to ambient air will increase its capacity to remove moisture and is an effective way to extend the drying season. In some years, conditions will not result in drying without a hot air system.”

ABOVE Canola & Mustard - this chart illustrates the effect of grain depth on static pressure. If you want to achieve 1 cfm/bushel, you need to run at seven inches for a depth of 15 feet and only three inches for a depth of 10 feet. Depending on fan size and type (size) of canola, grain depths of 8.5 to 12 feet will result in sufficient airflow rates for NAD.

Soon after they began farming about 10 years ago, the old model wasn’t working; they developed a new one.

by John Dietz

Like two plus two, the logic adds up when it comes to sustainable farming. Something had to change when andrew and Tanis De ruyck committed to becoming the next generation to own and farm six quarters in south-central Manitoba.

That was about 10 years ago. Last year, 2011, they were selected as Manitoba’s o utstanding Young Farmers. They were still on the land first farmed by andrew’s great grandfather back in the 1940s, making a go of it, raising two children, working beside andrew’s parents and getting along with andrew’s three non-farming sisters.

r ather than taking off-farm jobs, rather than trying some novel idea to mine more money from the acres, rather than going deeply into debt to finance their way out of a problem, the couple did a little two-plus-two analysis.

They saw strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWo T). The SWo T analysis was a little technique an-

drew had learned through his five years as a Farm Credit Corporation advisor.

For their situation, the analysis pointed to offering service as farm management consultants.

andrew and Tanis met while they were studying toward agriculture degrees at the University of Manitoba. He was two years ahead of her. Tanis had grown up in the town of Dauphin. after being married and having their first child, they decided to make the move to the farm and raise their family.

The De ruyck farm is between p ilot Mound and Mariapolis on rolling, good quality farmland. a s a boy, andrew knew it as

TOP: The cows are gone and new machinery is paying for itself. INSET: Andrew, Tanis, Ben and Paige DeRuyck are carrying on the multi-generational farm started by Andrew’s great grandfather.

a mixed farm with about 900 cultivated acres and 40 cows. one day, he hoped, he would farm and raise a family there.

“When I was 18, or whatever, I didn’t think I could really afford to farm. I didn’t have any idea of the financial requirements, but it just didn’t seem feasible at all,” he says.

andrew got his ag degree in 1995, and began the first of four off-farm jobs over the next six years. He worked in product development with two chemical companies, then moved on to the FCC and later the CIBC.

He and Tanis started full-time farming with his folks in 2001. By then, the “hobby” herd had grown to include about 275 head and a small feedlot for finishing steers. nearly the entire farm was in a corn-canola-and-alfalfa rotation.

“I started buying my first cows as an income tax write-off. Those first couple years after university, I was paying about $2 tax on every five dollars I earned, so there was nothing left to invest. The first year was pretty tough – I didn’t get the refund I was expecting. I got my refund the next year, bought more cows, and it started to snowball,” he says.

The De ruyck farm transition was rolling along very well by May 2003, he recalls. Tanis had taken over the accounting; she was home full time with the family. Cattle prices were high. They sold 100 steers – their first big shipment.

“I was lucky,” he says. “My first crop of steers got slaughtered the day that BS e hit. The killing plant confirmed they’d been killed that morning. Shortly after, there were animals being shipped back home.”

It would be years before cattle prices would recover. The Deruyck farm enterprise, supporting two families, no longer was viable.

andrew fell back onto his financial training at the FCC.

“FCC had a really good training program and gave me a lot of knowledge about financial management. I started looking at ways to apply that, and got contracts with Canadian Farm Business advisory Services (CFBa S) program and Farm Debt Mediation Services,” he says.

In the crisis time that summer, he and Tanis analyzed their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Their strengths were in education and the financial training andrew had received. The farming operation was a weakness, at that time. It had enough working capital, but the timing for expansion was wrong for them.

“I had to find something that would make some money without a lot of investment. That’s why I used my education instead of my financial resources. I started the consulting business, got some contracts with the government and started private consulting.”

private consulting was soon a flourishing business for the cattleman. He became a go-to guy for farms in the region that were in a financial corner for taxes, cash flow, risk management, financial management, farm expansions, retirement and succession planning.

De ruyck and a brother-in-law with FCC background, Mark Sloane, partnered in a 2009 joint venture, right Choice Management Consulting. Both De ruyck and Sloane love sharing their passion, real-life experiences and knowledge with their clients. Their experience and expertise has proven invaluable

for a wide variety of clients from around Western Canada. They provide mediation services as well as farm management advice. along the way, andrew recalls, they had discovered a “market” or niche for someone to mediate for farm families internally as well as between families and creditors. They found a similar need for mediation between rural boards of directors and their business managers.

“Consulting fits our skills and really adds value to the farm. We made a conscious decision to be diversified in that way,” he says.

Doing financial consulting was not a “natural” for De ruyck. He was not fond of math or numbers in the classroom. He describes it as a learned skill that developed after he began working with farmers at FCC.

“I didn’t learn it at university. I didn’t learn it from a book. at FCC, I started noticing my top clients knew their numbers. They were doing their cash flows. That really helped me to determine the value of it, and once I realized the value, I started paying more attention at home, on my own farm. o nce that happens that’s what makes a consultant exceptional,” he says.

It’s good to go through a SWo T analysis for any farm, but particularly if the farm is under financial stress, he says.

Many diversification ideas are high-risk ventures – and not at all suited – for more than a small number of farms. He’s learned, diversification must “revolve around your individual strengths and opportunities” to be successful.

By grasping the consulting strength, opportunities emerged to make the De ruyck farm in this generation more sustainable than ever.

The farm has grown to 1,400 acres of grains and oilseeds. There’s different machinery in the sheds, each item paying for itself with either farmed or custom farmed acres. The cows are gone. The peaceful succession to new farm ownership is well underway. and there’s a new generation, Ben and paige, learning the ropes of integrated family farming.

Losses can be surprisingly high.

by Bruce Barker

It is a fact of life that there is some harvest loss of canola seed during harvest. What may not be known, though, is how high those losses really are. research conducted by robert gulden when he was at the University of Saskatchewan in the early 2000s found that average yield losses of 5.9 percent were observed, with a range of 3.3 to 9.9 percent.

gulden, who is now at the University of Manitoba, is updating that research in a prairie-wide study of canola harvest losses. The third year of trials is being completed in the fall of 2012, and final results of the study will then be released.

Jim Bessel, former Canola Council of Canada agronomist, has spent a lot of time looking at harvest losses in canola. He worked with Les Hill at the prairie agriculture Machinery Institute at Humboldt, Saskatchewan, to develop ways to measure actual harvest losses. Bessel says harvest losses can be minimized by using proper combine settings.

“It takes a change in mindset. There is a productivity-to-efficiency ratio that farmers look at. How fast can you go and still have

By

acceptable losses,” says Bessel.

The first step, though, is to measure actual loss. Forget the combine monitor, because it doesn’t measure actual loss, and only tells you when losses are rising or falling – unless it is calibrated with actual harvest loss out the back of the combine. The only accurate way to measure loss is to spend some time actually measuring the loss by getting a little dirty.

Hill’s approach uses a drop pan of some sort to measure actual loss. He prefers a large metal pan that matches the full width of a combine’s discharge area that attaches to the bottom of the combine and can be released with the pull of a lever. agriTrac equipment in Westlock, alberta, has also developed a full-width pan that attaches by magnet to the belly of the combine. To release the pan, the combine operator unplugs the magnet cord from its power source. The

TOP: No matter the colour of the combine, canola harvest losses can average six percent.

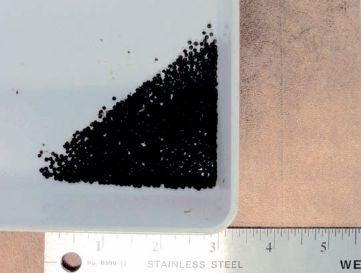

INSET: Four toonies’ worth of canola seed in the corner of a onefoot-square catch pan equals a loss of one bushel per acre.

SHARE INFORMATION ACROSS THE ENTIRE FARM

• Share guidance lines and coverage maps from vehicle to vehicle.

• Exchange prescription maps, guidance lines, coverage maps, drainage designs, soil sampling/scouting jobs, and yield data between the office and field.

• Access real-time movement of your vehicles, engine performance data, vehicle alerts, and vehicle breadcrumb trails.

• FREE! Use the Connected Farm app on your smartphone to map field boundaries, flag points of interest, and enter scouting information.

• FREE! View and analyze your collected mapping and scouting data from the online viewer.

Call your crusher or retailer to make today’s most profitable hybrid canola decision. Field-to-field, growers are booking Nexera canola Roundup Ready® and Clearfield® hybrids. With leading agronomic performance and profitability, only Nexera canola hybrids help meet growing demand for heart-healthy Omega-9 Oils. To see the 2012 Field Trial results go to healthierprofits.ca.

full-width pan is useful because it assesses losses across the entire discharge width. a stick pan can also be made by attaching a broom handle to a pan with deep sides. another approach is to simply throw a deepsided pan under the combine discharge. a one-foot-square pan works best with the conversion charts that Hill has developed.

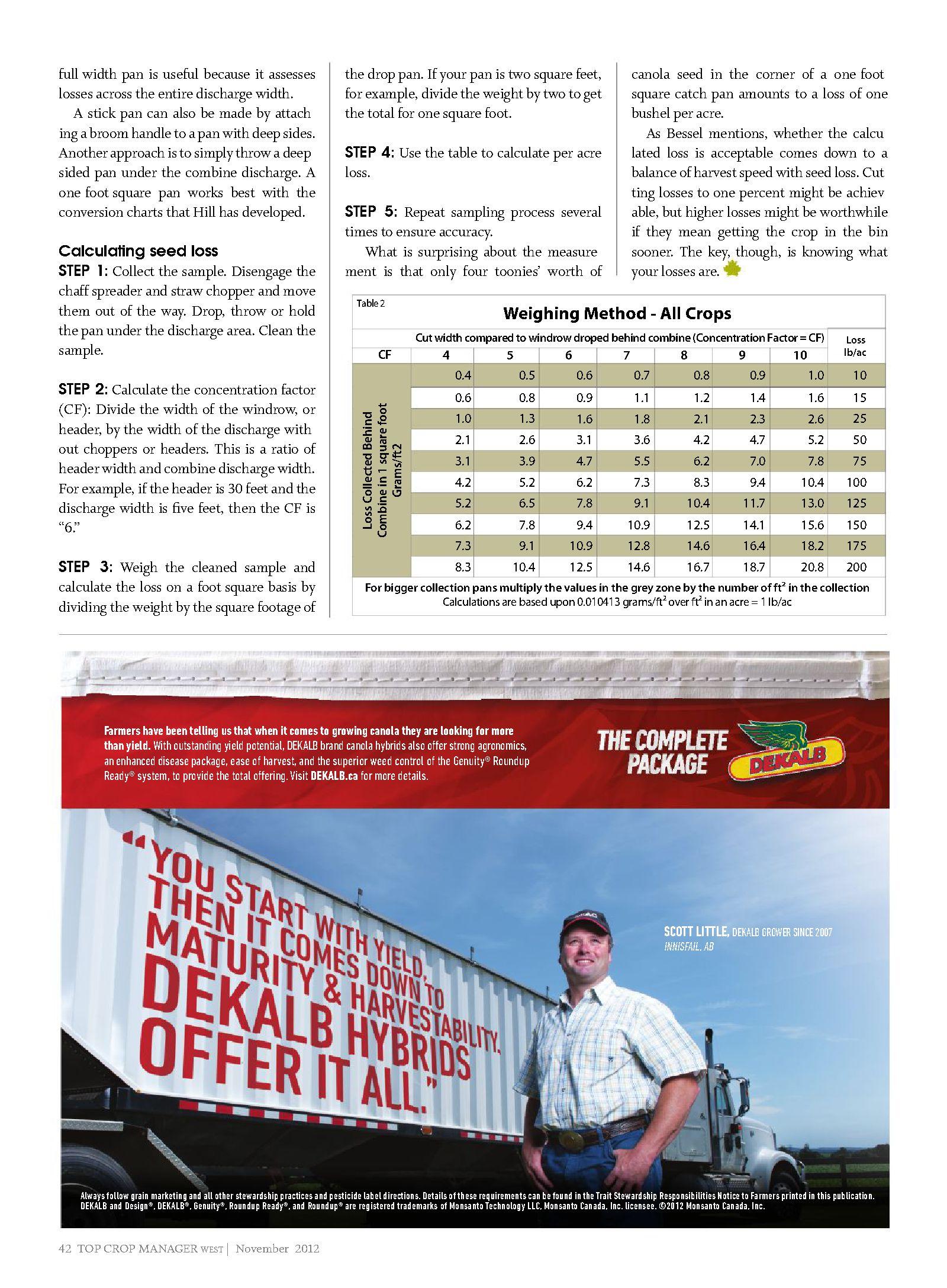

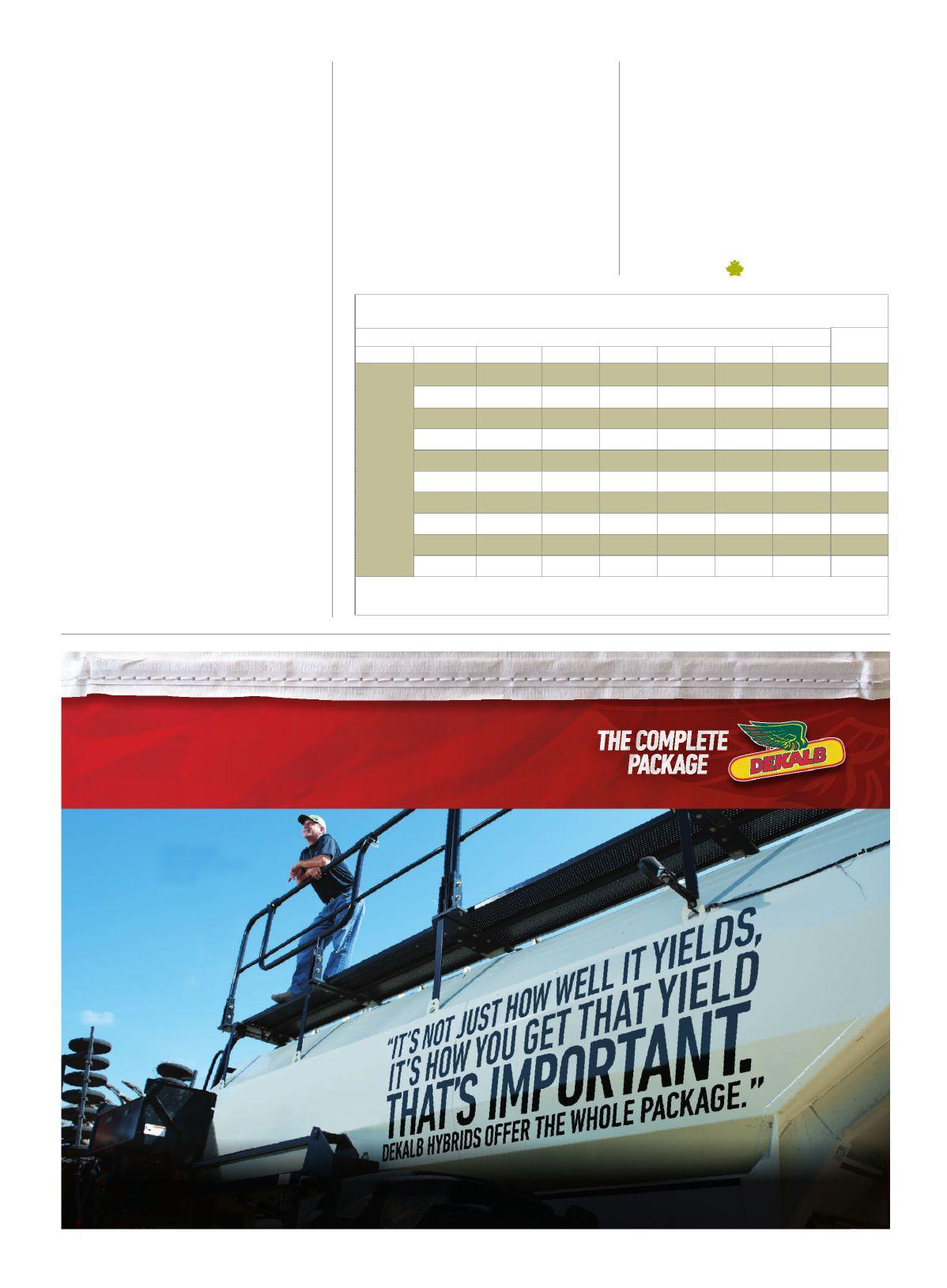

STEP 1: Collect the sample. Disengage the chaff spreader and straw chopper and move them out of the way. Drop, throw or hold the pan under the discharge area. Clean the sample.

STEP 2: Calculate the concentration factor (CF): Divide the width of the windrow, or header, by the width of the discharge without choppers or headers. This is a ratio of header width and combine discharge width. For example, if the header is 30 feet and the discharge width is five feet, then the CF is “6.”

STEP 3: Weigh the cleaned sample and calculate the loss on a foot-square basis by dividing the weight by the square footage of

the drop pan. If your pan is two square feet, for example, divide the weight by two to get the total for one square foot.

STEP 4: Use the table to calculate per-acre loss.

STEP 5: repeat sampling process several times to ensure accuracy.

What is surprising about the measurement is that only four toonies’ worth of

canola seed in the corner of a one-footsquare catch pan amounts to a loss of one bushel per acre.

as Bessel mentions, whether the calculated loss is acceptable comes down to a balance of harvest speed with seed loss. Cutting losses to one percent might be achievable, but higher losses might be worthwhile if they mean getting the crop in the bin sooner. The key, though, is knowing what your losses are.

The top canola varieties are now available from your local UFA. Talk to us today and we’ll help you make the best selections for your operation. So you can grow with confidence all season long.

Because a whole lot can grow from one good decision.

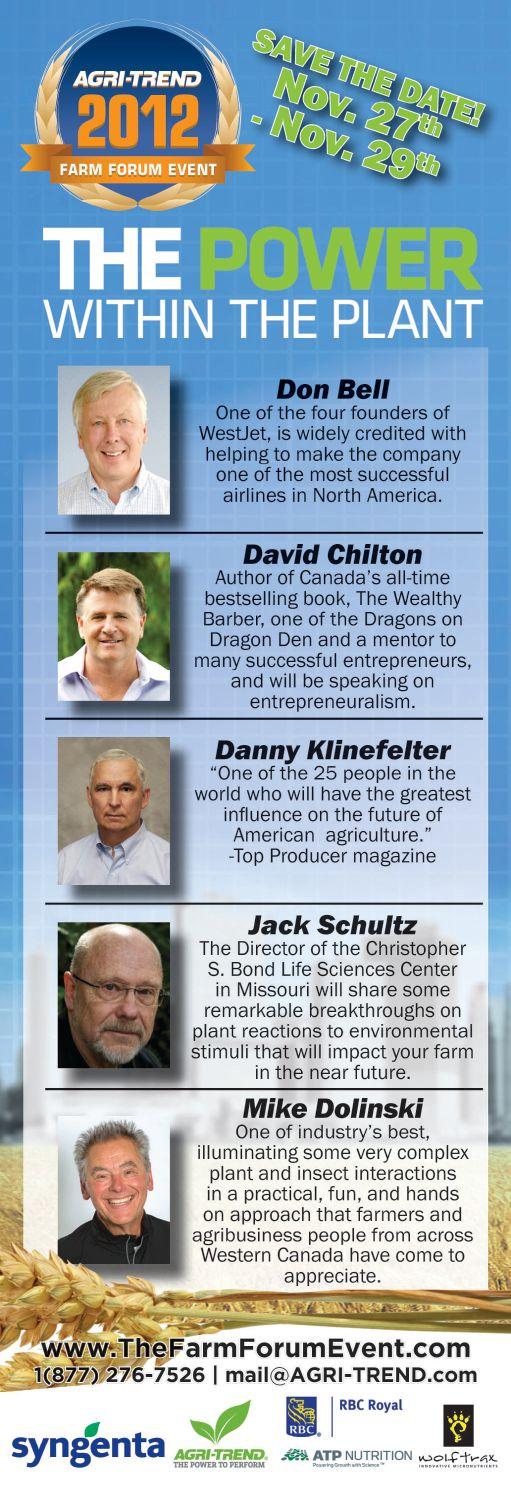

FarmTech 2013 features an outstanding line-up of speakers delivering more than 60 concurrent sessions covering the latest in technology, environment, agronomy and farm business management. The Agricultural Showcase is home to the most innovative companies displaying their products and services along with special events and networking opportunities.