TOP CROP MANAGER

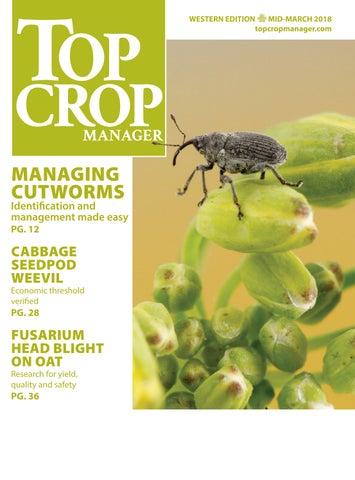

MANAGING CUTWORMS

Identification and management made easy

PG. 12

CABBAGE SEEDPOD WEEVIL

Economic threshold verified PG. 28

FUSARIUM HEAD BLIGHT ON OAT

Research for yield, quality and safety

PG. 36

Identification and management made easy

PG. 12

CABBAGE SEEDPOD WEEVIL

Economic threshold verified PG. 28

Research for yield, quality and safety

PG. 36

6 | Monitoring multiple pests

Food bait traps successfully attract both male and female cutworm moths, but not bees.

By Donna Fleury

| Understand temperature inversions Avoiding inversions is the key to avoiding spray drift.

By Bruce Barker

22 | The process of pulses

Understanding inoculation and nitrogen fixation of legume crops.

By Ross McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag

VIDEO: BLACKLEG IN CANOLA

The Canola Council of Canada has released an educational video highlighting blackleg in canola and the management tools available to producers. The video helps producers understand how blackleg has evolved resistance to the common genes used in breeding, and also explains the current situation and best management practices to avoid the disease. Visit topcropmanager.com/agronomy/canola

Readers will find numerous references

JANNEN BELBECK | ASSOCIATE EDITOR

While putting his issue together, I was reminded just how intricate (and complicated) disease is. Let’s look at Fusarium head blight (FHB) and its many forms as an example. Our story on page 36 covers the status of the disease in oats and how researchers at the University of Saskatchewan are surveying for FHB in Saskatchewan oat crops. According to the researchers, F. poae is often the most commonly detected species, followed by either F. graminearum or F. avenaceum. Other species detected in recent years include F. culmorum, F. sporotrichioides and F. equiseti. That’s a lot of variants for one disease.

Breeding crops for disease resistance takes time, money and a lot of testing to ensure safety and sustainability. Plant breeding is so multifaceted and can be challenging to understand, even for some in the agriculture industry. But the topic gets a lot of negative attention outside the agricultural sector – mostly due to fear mongering and incorrect assumptions that plant breeders inject toxins into crops, creating “frankenfoods,” and labelling genetically modified food as dangerous to human health. This is untrue, and the scientific and agricultural communities go to great strides to bust these myths. Various media continue to communicate the truth of a complicated situation. A new Canadian-made film Before the Plate, which is expected to premiere this summer, attempts to close the information gap between urban consumers and farming in Canada, including both conventional and organic farming practices.

What many anti-GMO activists fail to understand is that breeding is an amazing tool to make our crops healthier (by adding enriched vitamins), safer (by making them resistant to diseases and eliminating mycotoxins) and less likely to fail (by making them more tolerant to drought. The introduction of traits, whether through cross-breeding, transgenesis or genome editing, gives added insurance so growers can avoid the worries of pests and diseases. Humans have selected for crop traits for thousands of years, and countless studies have proven genetically-modified crops to be safe and effective. Perhaps part of the issue is that GMOs are not all the same and there’s confusion on what’s considered “GMO.” For instance, the Non-GMO Project – a non-profit organization – doesn’t consider crops bred through mutagenesis (a process that creates random mutations in a gene through the use of mutagens like radioactivity) to be genetically modified, yet denounces other biotech tools like CRISPR.

Despite the leaps and bounds made in the technology of breeding, growers still need other tools to fight off foes (at least for right now). Whether that involves trapping strategies, registration of new effective pesticides, or utilizing scouting techniques like referring to economic thresholds for spraying, Top Crop Manager will continue to share the latest research so you’re ahead of the curve – whether it’s in pest, weed, or disease management, or discussing the newest technologies in plant breeding. If there are any specific questions or topics you’d like us to address, you can always reach us at topcrop@annexweb.com.

Ted Markle • tmarkle@annexbusinessmedia.com

PRESIDENT & CEO Mike Fredericks Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

CIRCULATION email: rthava@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 416.442.5600 ext. 3555 Fax: 416.510.6875 or 416.442.2191 Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues Feb, Mar, Mid-Mar, Apr, June, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $47.50 Cdn. plus tax Top Crop Manager East – 7 issues Feb, Mar, Apr, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $47.50 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes

Food bait traps successfully attract both male and female cutworm moths, but not bees.

by Donna Fleury

Cutworms are a complex of several pest species that affect multiple crops grown in Canada. A few species can cause economic damage in cereal and oilseed field crops. Researchers are working to find efficient monitoring tools that can determine distribution of cutworms and alert growers to impending outbreaks, while excluding bee pollinators.

“Early research in the ’70s and ’80s focused on identifying sex pheromones for cutworm pests, and subsequently developed traps to monitor these species using sex pheromone cues,” explains Maya Evenden, professor and head of the Evenden lab at the University of Alberta. “However, these traps attracted moths from great distances, so [they] weren’t that good at reflecting local population densities. These moths tend to be quite large and are good fliers, so they could be travelling for quite a distance. Except for bertha army worms, these tools so far haven’t been successful enough to be adopted for monitoring cutworms.”

Researchers started looking for other monitoring tools for cutworms and explored synthetic food bait traps as a potential option. These traps are baited with mixtures of fermented sugars known to attract the noctuidae family of moths that cutworms belong to. These types of traps had not really been evaluated for use in wheat, barley or canola cropping systems where cutworms can be a problem. Evenden has conducted a number of different projects focusing on strategies to monitor multiple cutworm pests.

“One of the key differences with food bait attractants is both male and female moths are attracted to the traps, compared to only males in the pheromone trapping system,” Evenden says. “Having a better understanding of females is important because

TOP: Green Unitraps baited with feeding attractant lures to monitor cutworm and other noctuid moths in Wainwright, Alta.

INSET: Project trap landscape near Wainwright, Alta.

The work you’re most proud of happens before sunrise.

Like getting your daughter to 7am hockey practice. At SeedMaster, we understand farmers because we are farmers. See what we’re proud of at SeedMaster.ca

they are laying the eggs. The fermented sugar attractants also don’t provide long distance cues like pheromone attractants, so we expected to be able to attract moths closer in vicinity to the food bait traps, gaining a better understanding of local population densities. We conducted various field trials using these trapping systems, and noticed in the pheromone trapping there was also a lot of by-catch of bees, particularly bumblebees. This can be problematic depending on the timing of trap placement – for example, in early spring there are lots of flying queens, which can be at risk.”

Evenden initiated a three-year project in 2015 to research food bait traps as an alternative to species-specific pheromone traps for monitoring multiple species of cutworm in wheat and canola systems. A second objective was to determine if food bait traps could be an alternative to reduce bee by-catch in the monitoring programs.

“Cutworms are tricky, as some species overwinter as eggs, others as larvae, so they are damaging the crop at different times. This also means that moths are flying at different times. Therefore, in the study, one particular species was targeted – the redback cutworm. For this species traps were set out later in the season from mid-to-late July and through to September to monitor the cutworm moth. The late trapping period also helped to avoid the bees,” Evenden says.

“We have completed three field seasons of research on food bait traps and cutworms, and two field seasons including bees. Our preliminary results show that we have been able to catch a number of cutworm moths in the food bait traps. However,

the challenge is we are catching both pest and non-pest species. Therefore, these traps will provide a good monitoring tool for understanding the community of cutworms in canola and wheat, but doesn’t seem to be as useful for estimating specific economic pest populations.”

Evenden adds that the findings are very positive and show that food bait traps do attract pest cutworm species and attract both

male and female moths. The food bait traps also trap fewer moths than the pheromone-based traps, which better reflects what is happening locally. The challenge remains that these traps also attract species that are less of a concern for monitoring programs. Although the field work is complete, some additional lab trials are underway to assess the female moths. The question is, if females are mated, do they still respond to the food bait traps? If they are no longer responsive once they are mated, then populations could be underestimated at a particularly important stage of when they are about to lay eggs.

“Another student is focusing specifically on the bees in the project,” Evenden says. “The results so far are very interesting, and have shown that for some reason bees are attracted to the moth pheromone traps but not the synthetic food bait traps. In the project, we placed both pheromone and food bait traps in the field along with a neutral control trap that did not contain any test compound. There was little bee catch in the unbaited traps

and no bees in the food bait traps, although some bees were captured in the pheromone traps. Yellow jacket wasps however, are attracted to the fermented sugar bait.”

“Cutworms are tricky as some species overwinter as eggs, others as larvae, so they are damaging the crop at

The results, bees seem to be attracted to the moth pheromones for some reason but not the trap. “We have ramped up our investigation of bee by-catch in the prairie-wide bertha army worm pheromone trap monitoring program,” Evenden explains. “We have collected landscape and other data for the past two summers and are now analyzing the data trying to determine if trap placement in the landscape may make them more or less attractive to bumble bees, and timing of placement. We are trying to add those landscape and other variables to model trapping strategies that would reduce the by-catch of bees.”

Overall the findings are good news for industry. Food bait

different times.”

traps do help contribute to the knowledge of what cutworm species are where, providing a community monitoring analysis. “The benefits of the food bait traps are that they do attract both male and female moths and provide a better understanding of population densities over short distances.

The bonus is these traps do not attract bees, which is a very important finding. We want to expand the research with food bait traps to try it on other moth pests to see if the attractant works as well as it does with cutworm moths.” Final project results are projected to be available in 2018.

by Donna Fleury

Cutworms are present across the Prairies, and in some years some species of cutworms can reach levels that are of economic concern in field crops. The focus of a five-year project conducted across the Prairies resulted in the development of better identification tools, a better understanding of cutworm biology and their natural enemies, and a management guide to improve cutworm monitoring and control in different crops.

Led by Kevin Floate, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta., this multi-faceted five-year project was initiated in 2012 with funding from the Canola Council of Canada and completed in 2016. A primary outcome of the project was the release of a field guide in 2017 providing identification and management of 21 cutworm pest species in the Prairies, called Cutworm Pests of Crops on the Canadian Prairies: Identification and Management Field Guide. The project included researchers with AAFC (Beaverlodge, Lacombe and Lethbridge, Alta., and Saskatoon), the University of Alberta, the University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge College and provincial entomologists from Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

“Cutworm species can be difficult to identify visually, even for experts,” Floate explains. “One of our objectives was to develop accurate and rapid methods of identification, which are required to maximize control methods during cutworm outbreaks. We were successful in developing a multiplex PCR [polymerase chain reaction] molecular tool to detect and identify five key cutworm species, whether it is an egg, larva, pupa, or moth. The simple test compares the DNA of an unknown species and if it matches the DNA of any of the five key species, then the test result is positive. The protocol for this quick and easy test has been published and is now available for use by diagnostic labs.”

Cutworms are really a pest complex, consisting of a group of

many different species that pose different risks to different crops at different times of the year. One of the key differences is in how species overwinter or arrive on the Prairies. Some species overwinter as larvae, and will begin feeding immediately in the spring on crops, for example winter wheat. Other species overwinter as eggs, hatch the following spring and then start feeding on young plants. There are also some species that don’t overwinter in Canada, but are blown up from the southern U.S. on air currents.

It is difficult to predict the arrival and numbers of these species, which arrive in the Prairies as a moth, lay their eggs and hatch in the fields later in the season. Some species have one generation per year, while others can produce two or three generations per year. As well, some species will have a preference for broadleaf crops, others prefer cereal crops, but this is not a hard and fast rule and cutworms will eat what is available.

“Management begins with field scouting early in the spring when emerging crops are vulnerable to cutworm damage,” Floate says. “Newly germinated seedlings and small plants are most at risk, as cutworms can cut off and kill the entire plant. As plants get larger, cutworms may only nip off a leaf, leaving the plant to survive and continue to grow. One of the challenges in scouting cutworms is different species have different feeding habits. There are above-ground, soil surface and below-ground feeders, so scouting requires being aware of the different types and looking for various clues. Cutworms tend to be most active later into the evening when conditions are cooler and relative humidity is higher. Depending on the crop and larval stage, a cutworm species may exhibit more than one type of feeding behavior.”

Start monitoring fields in the spring when conditions begin

ABOVE: Both images show larvae of a parasitoid wasp emerging from a cutworm.

“One of the challenges in scouting cutworms is different species have different feeding habits. There are above-ground, soil surface and below-ground feeders, so scouting requires being aware of the different types and looking for various clues.”

warming up. Field patches that appear to be thinning or becoming bare, particularly in silty soils or soils at the top of rolling hills may be a particular risk. In those areas, carefully dig around in the top 2.5 to five centimetres (one to two inches) of soil around the base of severed plants within gap rows or around the base of healthy plants at the end of these gaps. Also search the soil at the base of healthy plants in the middle of bare patches. Newly hatched larvae are very tiny and will actively feed until they reach up to an inch in size. Once caterpillars mature and are generally larger than an inch in size, they tend to be mostly done feeding as they prepare to pupate.

“Economic thresholds have been developed for the many of the cutworm species and are outlined in the field guide,” Floate says. “If scouting reveals that economic thresholds have been exceeded and cutworms are still actively feeding, then producers will need to make a decision about whether or not to implement a chemical control option. Cutworm damage usually occurs in patches within a field, so if producers decide to spray, target the affected area and a margin of about 10 metres surrounding the damaged areas. Areas of visible damage have already been attacked and cutworm larvae will be moving away into adjacent areas of the field onto new plants. Spraying an entire field is usually unnecessary. Targeted spraying of damaged areas and surrounding margins is a good strategy for managing populations, reducing costs and equipment wear and tear, but most importantly for protecting natural enemies.”

One interesting finding is there are many species of beneficial insects already in the field working to control cutworms. Spraying an entire field can wipe out beneficial insects such as parasitic wasps or predacious beetles. Floate notes that although beneficial insects will probably not stop a cutworm outbreak in time to save the crop, a healthy population may reduce the duration or size of an outbreak or keep numbers below economic thresholds. A chemical control option may still be

needed to stop a cutworm outbreak, but applying chemicals only where needed in the field can leave beneficials to continue providing natural control.

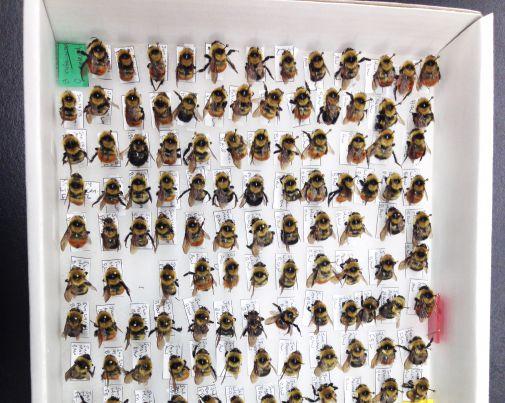

“To better understand the biology

and species of parasitoids and levels of parasitism, we collected hundreds of cutworm specimens from all three prairie provinces over three years,” Floate says. “We reared these cutworms indoors until they either became adult moths or parasites emerged from the larvae. We identified at least three species of flies and at least 13 fairly common species of parasitic wasps, each species producing from one to a few hundred parasites from each cutworm.

Continued on page 21

YOU INVEST IN A BIN TO PROTECT YOUR PRODUCT FROM THE ELEMENTS, BUT WHAT IS GUARDING YOUR GRAIN FROM SPOILAGE ON THE INSIDE?

Grain Guard has an established catalog of aeration and conditioning equipment to assist you in managing your grain storage. With more than 100,000 fans in operation Grain Guard remains the leader in aeration design.

by Bruce Barker

It’s 5 a.m. on a calm, sunny morning in June. Perfect time to spray? Not so fast. A temperature inversion is likely, which could result in small spray droplets remaining suspended in the air and moving off-target.

“I think it is a safe assumption to say that a temperature inversion on the Prairies will occur every night from one hour before sunset to one hour after sunrise unless there is cloud cover or wind,” says Tom Wolf, a sprayer technology specialist with Agrimetrix Research and Training in Saskatoon, who can also be found at sprayers101.com and also on Twitter @Nozzle_Guy.

Most farmers have directly observed the signs of an inversion. Dust or smoke may rise slowly and hang in the air, often slowly drifting away at the same level, or strong odours or distant sounds that aren’t normally observed are also indicative of an inversion.

Inversions develop in a 24-hour cycle due to the differences of warming and cooling of the air near the soil surface. As nighttime sets in, the soil cools. The air near the soil surface becomes colder

and denser than the air above it. This is a temperature inversion –essentially preventing air from mixing. As long as skies remain clear, the soil surface temperature continues to cool the air near it as the night progresses. The height of the inversion grows as the surface air cools, and can reach upwards of 100 metres. Maximum inversion intensity and height will occur shortly before the sun begins to heat the soil surface in the morning.

In the early morning without cloud cover, the sun’s solar radiation warms the soil, which in turn warms the air near the soil surface. As the surface air warms, the warm air rises and is subsequently displaced by cooler air that sinks to the ground. This sets up what’s called a thermal turbulence cycle, where warm air is moving upwards and the inversion begins to break up.

ABOVE: Evening inversions pose a greater risk for spray drift than morning inversions because droplets have longer to move off-target.

By late morning, mixing and air turbulence between the warmer air and the cooler air often causes light, but gusty, variable-direction winds near the surface. The formation of late-morning or afternoon cumulus clouds indicates that this convection cycle is occurring. This condition helps mix adjacent air layers, diluting the dust, smoke, or drift they contain. The opportunity to spray will depend on how turbulent the winds are. By mid-afternoon, as the wind rises, the wind turbulence mixes warm and cool air near the ground to equalize the air temperatures.

The risk of spraying during an inversion is that small spray droplets do not disperse and dilute to harmless levels with moderate winds. Rather, air trapped by an inversion may flow downhill or move with very light breeze and carry the small droplets, which remain very concentrated, off-target to other crops where drift damage may occur.

Cloud cover can prevent inversions from forming. Generally, greater cloud

cover causes slower surface cooling and slower inversion formation in the late afternoon or evening. When skies are completely overcast, the surface will cool very slowing and inversion formation is unlikely. This is why nighttime temperatures are usually warmer under cloudy conditions than clear skies.

The intensity of an inversion can be measured by comparing the air temperature at two different heights above the soil surface. Subtract the air temperature measured at six to 12 inches above the soil surface from the air temperature at eight to 10 feet. If that number is positive, the

“If we talk about what we’re doing, people will understand how their food is grown and why we grow it the way we do.”

Diagram of an inversion’s temperature profile, height, intensity, density stratification and its air motion near the surface

Temperature begins decreasing with increasing height (lapses)

Temperature increases with increasing height within inversion

Warmest air temperature and lowest density

Air ow throughout the inversion is the only horizontal (laminar ow)

Lowest air temperature and greatest density NO VERTICAL MOTION

atmosphere is inverted. The greater the difference in temperature, the more intense the inversion is.

Wolf says measuring the air temperature differences can be difficult with conventional thermometers because the temperature differences over short distances are small, often only one degree or less. North Dakota State University (NDSU) has published a guide that says other observations can provide an indication of a temperature inversion:

• Large temperature swings between daytime and the previous night

• Calm (e.g. less than three km/h wind) and clear conditions when the sun is low

• Intense high-pressure systems (usually associated with clear skies) and low humidity where you intend to spray

• Dew or frost indicating cooler air near the ground (fog may be too late).

• Smoke or dust hanging in the air or moving laterally

• Odours travelling large distances and seeming more intense

• Daytime cumulus clouds collapse toward the evening

• Overnight cloud cover is 25 per cent or less

Avoid spraying in inversions

Even with low drift nozzles, spraying is not recommended during an inversion. Low-drift nozzles still produce some fine droplets less than 200 microns in diameter. While larger droplets with greater velocity will hit the target quickly, fine droplets remain suspended and move with low wind speeds and float for long distances. The high humidity conditions associated with clear nights prevent these droplets from evaporating.

Early morning shortly after sunrise when skies are clear and wind is low is usually one of the worst times to spray. Under these conditions, waiting until solar radiation starts to heat up the ground will weaken the inversion. A thermal turbulence cycle will develop, and once the inversion is broken, spraying can begin, as long as winds do not become too strong to cause drift of larger spray droplets.

“A good rule of thumb for inversions is to wait a couple hours after sunrise before spraying to allow the inversion cap to disperse,” Wolf says.

Information from NDSU indicates that evening inversions pose a greater risk for spray drift than morning inversions because evening inversions are very persistent and can remain until shortly after sunrise if skies remain clear, providing a longer time frame for spray droplets to move off-target. Only windy or cloudy conditions will disrupt the inversion.

In its comprehensive document on temperature inversions, NDSU reports that low wind speeds three-to-four hours before sunset under clear sky conditions may appear to be ideal conditions for pesticide application, but these conditions can be deceiving, and are actually ideal for rapid inversion formation.

For a comprehensive look at temperature inversions, refer to NDSU Extension’s factsheet, “Air Temperature Inversions” ( ag.ndsu.edu/publications/crops/air-temperature-inversions-causescharacteristics-and-potential-effects-on-pesticide-spray-drift)

Sprayers101.com also has a large amount of information on how to select sprayer nozzles to minimize spray drift while maximizing pesticide effectiveness.

You’ve identified volunteer canola as a weed. Now it’s time to deal with it.

For control of all volunteer canola, tank mix Pardner® herbicide with your pre-season application of glyphosate. Make Pardner your first choice.

by Bruce Barker

Amidge by any other name is still a midge – but it’s not swede midge. That’s the finding of scientists with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), University of Guelph and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Swede midge had been confirmed by CFIA in 2007, but what had previously been thought of as the swede midge in northeast Saskatchewan since 2007, and in research projects by AAFC starting in 2012, has been confirmed to be a new species of midge.

“We were doing some emergence cage studies in 2016 to help determine the life cycle of swede midge on the Prairies and found that we were catching hundreds of adult midges in the cage trap, but no males were captured on the pheromone traps. Pheromones are very, very species specific, so I wondered if there was something wrong with the pheromone,” says Boyd Mori, a research scientist with AAFC in Saskatoon.

Boyd subsequently sent the pheromone traps to the University of Guelph. Researchers there found the pheromone traps were capturing hundreds of swede midge within days. “That made us suspect that something else was going on.”

In earlier research by AAFC’s Julie Soroka and Lars Andreassen, which included a distribution survey, life cycle assessment and screening for biological control, they found some key differences between Saskatchewan and Ontario populations of midge.

“By 2016, we were starting to question if the Saskatchewan midge was swede midge,” Mori says.

Swede midge is part of the gall midge family Cecidomyiidae that has more than 6,000 described species. In agriculture, wheat midge, Hessian fly and swede midge are pests that have caused economic damage in Canada. The swede midge is part of the Contarinia species, and is named Contarinia nasturtii. Swede midge was first identified in North America in Ontario in 2001, and has since spread throughout Eastern Canada and much of the northeastern U.S. seaboard as well as Ohio, Michigan, and Minnesota.

Following up on the pheromone issue, Mori also collected larvae of the midge from infested flower buds, and reared them to adults. He sent the adults to Jamie Heal at the University of Guelph for identification. Heal noticed some very small differences between the Saskatchewan and Ontario adult midges. Adult midges from Saskatchewan were also sent to Brad Sinclair with CFIA in Ottawa who also observed differences and was confident that the midges were not swede midge. Subsequent DNA sequencing confirmed that the Saskatchewan midge was not

Dried, old flower galls.

swede midge.

“Only 91 per cent of the DNA sequence had similarity between swede midge and the new midge. Geneticists say you need between 98 and 100 per cent similarity to be considered the same species,” Mori says.

For now, Mori is calling the new species the “canola flower midge.” Sinclair is working on the species description and a name will hopefully soon be established. This is the first confirmation of this midge species anywhere in the world.

Source: Mori, AAFC

What is known about the unknown midge

Soroka’s earlier research on what was thought to be swede midge but was the “canola flower midge” provided some insight into this new midge species. She established that it has one to two life cycles per year. This is important, because in Ontario where the swede midge has up to five lifecycles, the swede midge has time to build populations to damaging levels in one growing season, and the pest can attack several different stages of crop growth.

In Saskatchewan, the only place eggs were found was in the developing flower buds. The eggs hatch inside the flower bud and have three larval instars. The larvae cause bottle-like galls to develop at the flower stage instead of pods. If the bottle-like gall is cut open, larvae may be found inside.

Two parasitoid wasps were also found that attack the “canola flower midge.” One is an Inostemma sp. and the other a Gastrancistrus sp.

“Neither of these parasitoids have been found on swede midge in Ontario,” Mori says.

In 2017, a distribution survey was conducted in Alberta, Saskatchewan and the Swan River area of Manitoba. Approximately 100 fields were surveyed with 100 racemes per field assessed for signs of damage or damage with larvae present. Results showed that the “canola flower midge” is widespread across the northern grain belt of Alberta and Saskatchewan and northwest Manitoba. Scott Meers and Shelley Barkley of Alberta Agriculture and Forestry collected the Alberta data.

“Any damage observed was very low so it is currently unknown if this midge can develop into a pest of canola,” Mori says.

Collaborators to the current research project at the University of Greenwich in the U.K. have identified the pheromone produced by the female “canola flower midge.” Field-testing will occur in 2018 and 2019 to confirm its effectiveness, and this will help establish the distribution of the midge across the Prairies.

Moving forward, Mori and colleague Meghan Vankosky at AAFC Saskatoon are continuing to research the new midge. Their projects include identifying the distribution of both midge species on the Prairies; determining the life cycle of the “canola flower midge” and its potential impact on yield; looking for biological control agents for both species; and confirming the pheromone trapping for the new species.

“If anyone would like to assist in the field surveys for the midge species, they can email me and we can see if we can get the traps and lures used for the survey,” Mori says. (Reach him at boyd.mori@canada.ca)

Continued from page 13

One of the species, a common Eurasian and North African parasitoid, was unknown in Canada or North America until we identified it in 2013. Overall, we estimated that in the samples collected, about 20 per cent parasitism or more was common, which can be a very important component of cutworm population management. Therefore, being patient and letting this army of beneficial insects do their job is a good practice.”

The project also assessed cutworm outbreak cycles and the factors influencing population levels.

“There are always small cutworm outbreaks across the Prairies or local outbreaks in most years,” Floate adds. “However, in some years there may be a lot of outbreaks causing cutworm damage over a large geographic area. What seems to be the underlying factor of a cutworm cycle, which typically occurs every five to seven years, is the weather pattern. For cutworm eggs or larvae to successfully overwinter depends on what the winter conditions are like. A cold harsh winter with little snow cover will tend to kill overwintering eggs or larvae and reduce numbers. However, a cold winter with lots of snow will improve survival. A wet spring can

On the left are early cutworm larvae and on the right are the larvae of a cranefly.

result in higher levels of disease pathogens attacking cutworms. So a series of two or three favorable winters and optimal spring conditions can keep ramping up cutworm numbers and create a peak cutworm cycle, while unfavorable winter and spring conditions can terminate that cycle.”

The results of the various aspects of the project formed the development of the Cutworm Pests of Crops on the Canadian Prairie: Identification and Management Field Guide. The guide provides detailed information on each of the important economic cutworm species, with additional sections on general biology, history of outbreaks, scouting techniques, the important role that natural enemies play and a list of additional information sources. Although the guide focuses on Prairie cutworm pests, the guide will be useful for other areas where these species also occur. The field guide is available online here: publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/aac-aafc/A59-422017-eng.pdf

NEW! Paradigm™ is the most powerful pre-seed tank mix ahead of wheat and barley. It gets the weeds you see and the weeds you don’t, including Group 2 resistant cleavers and hemp-nettle, in tough spring or fall conditions. Pre-seed or post-harvest, it’s GO time. Go to LeaveNothingBehind.ca. ® TM Trademark of The Dow Chemical Company (“Dow”) or an affiliated company of Dow. | 0218-57781-2

Legume crops are unique in that they can fix much of their own nitrogen (N) requirements from the air to reduce or eliminate the need for N fertilizer. Legume crops include, alfalfa, clover, soybean, dry pea, bean, lentil, fababean and chickpea.

BY Ross McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag.

Legume crops form a relationship with living bacteria called rhizobium. Rhizobia bacteria live in association with legume plant roots to convert N from the air into useable N for the plant.

The atmosphere contains about 79 per cent nitrogen gas. Atmospheric nitrogen gas (N2) exists as two N atoms with very stable bonds that are not easily broken. As a result, N2 is relatively unreactive and not available for uptake by most plants, except for legumes.

Lentil on right and winter wheat seeded in lentil stubble in long-term rotation plots at Bow Island, Alta.

Biological N fixation transforms atmospheric N2 gas into plant available N forms by N-fixing bacteria. These bacteria are a broad group of singlecelled organisms capable of fixing N by producing nitrogenase, an enzyme that catalyzes the reaction that breaks the strongly bonded N2 gas into ammonia-N (NH3). Nitrogen fixing bacteria can occur as free-living microbes in soil, or as bacteria that live in association with legume plant roots. The N-fixing rhizobia bacteria that live in association with plant roots form nodules on legume roots.

The protective environment of the nodule is ideal for the rhizobia and the nitrogenase enzyme. Legume plants provide carbohydrates to sustain the bacteria. In return, the rhizobia bacteria provide ammonia-N to the plant, which is rapidly assimilated into organic N compounds. The relationship between the N-fixing bacteria and the plants is symbiotic, meaning both the legume plant and the rhizobia bacteria benefit from the mutual association.

Healthy soil contains vast populations of bacteria. Each legume plant requires specific rhizobia bacteria for the symbiotic relationship to form root nodules. For example, the rhizobia bacteria that form symbiosis with pea, lentil and fababean will not form symbiosis with other legumes. Most prairie soils lack the specific rhizobia needed for effective legume nodulation. This means legume seed must be properly inoculated with the correct specific rhizobia bacteria (Table 1).

Rhizobia can live freely in soil for several years, without a legume host plant. When free-living in soil, they survive on dead or decaying organic matter. Introduced rhizobia that survive in soil often gradually lose the ability to fix higher levels of N. As a result, for effective N-fixation to take place, legume crops should always be inoculated.

The ability of rhizobia bacteria to infect plant roots is very unique and complex. Plant roots must differentiate between numerous micro-organisms and beneficial rhizobia bacteria. For rhizobia infection of legume plant roots to occur, there are unique multi-step interactions or communications that take place between the legume roots and rhizobia.

The process is very complex, but simply explained, plant root hairs release specific substances called flavonoids, which are used to attract specific rhizobia. Each legume type secretes a different type of flavonoid, therefore only certain rhizobia respond to specific flavonoids. The rhizobia bacterial use flagella, a tail-like structure, to move in the soil solution toward the plant root hairs secreting the specific flavonoid. Movement is limited to a couple of millimetres in the soil. When a plant root is encountered, rhizobia attach to the surface of the root.

Inoculation of specific rhizobia on the legume seed results in nodules clustered near the vicinity of seed placement. When legumes are inoculated with rhizobia bacteria, placement on or very near the seed is essential to ensure contact between the inoculant and legume root hairs.

The root rhizosphere is the zone of soil immediately adjacent to the plant root, that is influenced by root activity. Roots take up nutrients like phosphorus and potassium from this zone. Roots also release nutrient rich exudates into the rhizosphere, which are an excellent source of nutrients for soil microbes including rhizobia bacteria. The abundant nutrition in the rhizosphere promotes rapid multiplication of the bacteria.

Small colonies of bacteria become anchored near the tip of the growing root hairs. The tip of a root hair curls around the rhizobia colony which becomes entrapped by the tip of the root hair. A deformation of the root hair occurs and a nodule develops, which contains the N fixing bacteria.

The plant provides carbohydrate and nutrients to the rhizobia,

and in return the rhizobia provide useable N to the plant. There is increasing evidence that the symbiotic relationship between the plant and rhizobia is controlled to restrict too many nodules from forming on root hairs, to optimize the amount of carbohydrate provided by the plant to the rhizobia, and in turn, optimize N provided to the plant for growth.

An inoculant contains live bacteria that is placed on the seed surface or very near the seed. When purchasing inoculant, always check to ensure it is the correct rhizobium species for the crop being grown and check the expiry date on the inoculant container. After purchasing inoculant, make sure it is stored in a cool, dark environment to maintain the viability of the live bacteria in the inoculant. Always apply the inoculant according to the manufacturer specifications to ensure correct application and rates. Never mix inoculant with

Inoculants provide legume crops with a specific type of bacteria, known as rhizobia, which form a symbiotic relationship with the plant. It’s a win-win situation that provides the plant with the nitrogen it requires to grow and the bacteria with a safe place to live and the sugars they require for growth.

As the roots grow through the soil, certain chemical signals are given off by the growing roots, which will trigger the bacteria that have been placed in the soil to infect the tiny root hairs that are being formed.

Through a complex chemical conversation, the root hair will engulf the bacteria, and eventually form a nodule, which is a bump on the root that contains a population of these bacteria in the middle.

This population of bacteria then brings in nitrogen gas from the air, creating the form of nitrogen the plant needs to grow. A win for the plant – and the farmer!

fertilizer as this often kills the bacteria.

There are three main types of inoculants:

Powdered – Fine peat containing rhizobia at a specific number per gram, applied directly to the seed. A sticker is usually needed to ensure rhizobia adhere to the seed coat.

Liquid – Contains the rhizobium in a buffered liquid, that is normally applied directly to the seed usually at the time of auguring and is held in place using a sticker. Some liquid inoculants are registered for use in a seed row application.

Granular – Small, peat-based or clay based granules contain the rhizobium in a protective environment; the granular product can be accurately metered into the seed row. A separate tank and meter is required on the seeder.

Depending on soil environmental conditions, it takes three-tofive weeks after seeding for bacteria to infect plant roots, form nodules and start fixing N. The effectiveness of the inoculation process can be assessed by simply digging up and examining the plant roots for the number, size, colour and distribution of the nodules.

Nodules on roots close to the original location of the inoculant that are red or pink inside indicate the bacteria are functioning and fixing N. Nodules are likely not fixing N when the inside appears white, grey or greenish. Nodules distributed through the root system may indicate that native soil bacteria have also infected the roots. These bacteria may not function effectively in fixing N to meet plant requirements.

When inoculant failure occurs, some possibilities to investigate include:

• Save a sample of inoculant to check for viability, in-case of inoculant failure.

• Was the correct rhizobium species used?

• Was the rhizobia viable? If not, was it due to poor storage?

• Low rate of inoculant used or poor retention of inoculant onto seed surface

• After seed was inoculated – was planting delayed? If so, the inoculant may not have survived on seed.

• If seed bed environmental conditions were warm and dry after planting, desiccation of rhizobia may occur while seed was in dry soil and rhizobia may not survive.

• If soils are cold or excessively wet after seeding, the rhizobia may not survive.

• Excessively high nitrate levels may inhibit root infection by rhizobia causing reduced nodulation.

• When plants are under stress from factors such as a lack of moisture or low soil fertility, the nodulation process may be affected.

• Some seed treatments can interfere with rhizobia survival. Was the seed treatment used approved for use with inoculants?

Legume plants that have limited nodulation will often have lower yield potential. A rescue, in-crop application of N fertilizer may be needed to ensure a reasonable crop yield.

Legume crops are great to include in a diverse crop rotation. To take advantage of the N-fixing ability of legumes, it is important to use the correct rhizobium bacteria and follow proper inoculation recommendations. The N-fixing benefits of a legume often persist for a year or two after the crop is grown – N is mineralized to benefit subsequent crops.

The demand for healthier (and more) food is motivating researchers around the world to find ways to improve agriculture practices to create more, healthier food in the most cost-effective way.

BY Trudy Kelly Forsythe

In Canada, the Global Institute for Food Security (GIFS) at the University of Saskatchewan conducts research into transformative innovations in agriculture in both the developed and the developing world. Apomixis is one of those transformative innovations their researchers are exploring to improve agriculture and help combat global hunger.

Apomixis is a natural plant reproduction system where flowering plants reproduce seeds asexually without pollination. The plants that grow from these seeds are genetically identical, or are clones, of their mother plant. There are about 250 plant species currently known to reproduce apomicticly, including dandelions, Kentucky bluegrass, raspberries and blackberries.

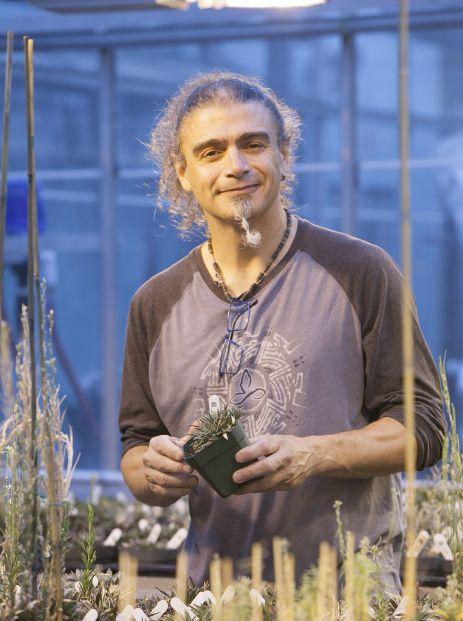

Tim Sharbel, an internationally renowned plant scientist from Montreal who is currently serving as GIFS’ research chair in seed biology, is a leader in apomixis research. Prior to moving to Saskatoon two years ago, he spent a decade at one of Europe’s largest biotech institutes, the Leibniz Institute for Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, working to identify genes associated with apomixis for agricultural improvement.

Dr. Timothy Sharbel, shown here surrounded by different genotypes of plants of the genus Boechera (rock cress), is working toward making crop plants asexual.

The ultimate goal of apomixis research is to make crop plants asexual. Working towards that, Sharbel and his team sample different individual plants from natural populations then analyse them using high-powered molecular genetic techniques. They do this to really drill down and understand what genes are expressed in sexual egg cells versus asexual egg cells.

“We look at the wild species and analyze them for individuals that produce through sex and through apomixis, then we try to identify the genes that lead to apomixis,” Sharbel says. “The plants look exactly the same; the difference really is in how these plants are producing their egg cells.”

There has been some success. Working with plants in the genus Boechera (rock cress), a wild Brassica and close relative of canola, Sharbel and his team have identified a couple of candidate genes that may underly apomixis, including one named Apollo.

“The idea would be that if we can identify the genes for apomixis in Boechera then we could apply them relatively quickly to Brassica,” Sharbel says. “We have transformed the Apollo gene into maize and Brassica, and in the next six months will see if it works to get proof of concept. We’re also working on Kentucky bluegrass and St. John’s wort trying to identify more candidate genes that we will try to transfer to crops to see if they induce apomixis.”

Apomixis research has many implications.

“Today’s agriculture is built on hybrid crop production,” Sharbel says. “Genetically distinct and inbred parental plants are crossed, and their first generation offspring exhibit hybrid vigour, having higher or better yield than their parents.”

However, in crops like pulses, breeders haven’t been able to exploit heterosis because crossings are very difficult. And for farmers who try to create their own seed from F1 hybrid seed, they lose the uniformity, or heterosity, of their crops, forcing them to buy seeds every year.

“The idea that we’re working on is that if you could take that F1 population and then simply turn sex off and turn on apomixis then those plants would reproduce clonally from then on,” Sharbel says.

The positive for the seed companies is that they could get new varieties to market more quickly.

“The whole process of creating a hybrid takes a lot of time and investment for companies, and they face many challenges like genetic incompatibilities between parental populations,” Sharbel says. “In the end, they get one size fits all variety, with associated yield increases.”

However, if breeders are able to turn sex on and off like a switch, one could use sex to create genetic variability, put all the seeds into selective regimes (wet, dry, hot, cold, etc.) and identify the plants that grow best in those conditions. At this point one would then turn sex off and go to seed increase immediately.

“It takes an eight- to 10-year plan to breeding now down to two to three years,” Sharbel says, explaining that apomixis is a tool that could lead to a fixation of heterozygosity, and hopefully heterosis, in crop plants.

“Hypothetically you could exploit, and give value to, more of the world’s biodiversity. Cross plant X with some distant species, let meiosis and sex mix things up for you, throw the seeds out in some selective regime, and that could be temperature or light or whatever you want, choose the best phenotype that grows out of that selective regime, turn off sex and go to seed increase right away,” Sharbel says. “We could quicken the pace of the generation of new hybrid plants and we could potentially produce unlimited numbers of hybrid crops.”

That means crops could be bred for specific niches, or anything breeders wanted. Or, more specifically, breeders could develop canola for southern Saskatchewan and for northern Saskatchewan. “Right now, the same seed goes to all,” Sharbel says.

The most significant implication of apomixis for Sharbel is the access to more biodiversity for crop improvement. “There are a lot of farmers in developing countries who are locally breeding for genetics that are really good for that local environment, but the farmer can’t integrate into a larger breeding program,” he says. “If they have a suitable characteristic and we can turn sex on and off, we can invite the farmer to licence this and integrate into a breeding program.”

This, he says, gives power to farmer, levels the playing field and gives value to the world’s biodiversity by enabling it to be incorporated into crops. “It would completely change agricultural practices.”

Mix what you want, seed what you want with the freedom of Aim.

Get a more complete burn down that lets you seed almost anything. Tank mix Aim with your choice of products, so you can use what you’re used to with superior results and no fear of cropping restrictions.

| LENTILS | WHEAT | BARLEY & MORE | FMCcrop.ca | 1-833-362-7722 GROUP 14

New study verifies economic threshold levels for the canola pest.

by Julienne Isaacs

Cabbage seedpod weevil is an invasive insect pest of canola. Originally found in Europe, the insect proliferated in the United States and was first confirmed in Alberta in the mid-1990s.

According to Scott Meers, Alberta’s provincial entomologist, the insect’s range has increased in recent years. The pest is typically found south of Highway 1 in Alberta and some parts of southern Saskatchewan. Two years ago, however, it expanded its range north all the way to Edmonton, Meers says. Last year (2017) saw a retraction in range to south of Red Deer, with the Calgary to Medicine Hat line taking the worst hit – its typical range.

Spraying for cabbage seedpod weevil is certainly advisable when pest populations reach economic thresholds, but Meers says it’s a mistake to spray too early.

“The cabbage seedpod weevil migrates into canola when it flowers,” Meers says. “If you spray too early you may have to spray a second time because the weevils may still be coming in.”

Weevils begin laying eggs when pods have grown in size to three-quarters of an inch, to an inch. This means there’s generally

about five days between first flowering and pods developing to the point where weevils can lay eggs on them, and this is the window during which producers should be spraying. “Things happen quickly,” Meers says.

But spraying isn’t always necessary – or cost effective. Some industry researchers have seen agronomists and producers push the economic threshold level down to two or even 1.5 weevils per sweep during scouting. But a new study by Agriculture and AgriFood Canada research scientist Héctor Cárcamo suggests the bar should be higher.

The study, which Meers also participated in, was conducted over four years from 2010 to 2014 in southern Alberta throughout the cabbage seedpod weevil region. The team sampled 71 commercial

ABOVE: Cabbage seedpod weevils are typically found south of Highway 1 in Alberta and some parts of southern Saskatchewan.

EverGol® Energy seed treatment fungicide provides soybeans with protection against the most important seed and soil-borne diseases caused by rhizoctonia, fusarium, pythium, botrytis and phomopsis. It provides quicker emergence, healthier plants and higher yields for your soybeans. Create the complete package of protection by combining the power of EverGol Energy with Allegiance® seed treatment fungicide for early season phytophthora, and Stress Shield® seed treatment insecticide for superior insect protection to help your soybeans thrive during critical early development stages.

Learn more at cropscience.bayer.ca/EverGolEnergy

fields in the area using sweep nets, sweeping 10 times in 16 areas within each field; they also collected yield data in order to relate insect catches to yield and update economic injury levels.

“The previous nominal threshold was three to four weevils per sweep, but some people were using lower numbers, such as two to three weevils per sweep,” Cárcamo says.

The threshold recommended based on this new research is 25 to 40 weevils per 10 sweeps, or 2.5 to four weevils per sweep.

But field sampling is often less than thorough, which can create an inaccurate picture of insect population levels in a given field. According to Cárcamo, insect populations are higher at the edges of a field, so sampling should be done at a minimum of four points inside a field. If producers only have time to sample the edges, they should use a threshold of four weevils per sweep, because insect populations will be closer to two weevils per sweep in the middle of the field.

Cárcamo says the study revealed other interesting findings. Fields that were planted earlier accumulated more weevils, he says,

meaning that delaying planting to, say, the middle of May resulted in lower weevil numbers overall.

Another finding from the southern Alberta study shows fields that were planted early had weevils at early flowering, but at the pod stage they didn’t have many Lygus bugs – another insect pest of canola. Cárcamo says there’s a myth that an insecticide spray at early flowering can “clean the field” to deter future Lygus bugs, but this is not an effective strategy: Early-planted fields generally do not get high Lygus infestations. In other words, producers are not seeing much benefit to spraying early when weevils are below threshold and they spray to attempt to prevent future Lygus issues.

In general, encouraging producers to spray only when absolutely necessary is a priority for the research community.

Cárcamo has issued a proposal under the new agriculture funding framework to look at the viability of a biological control

for cabbage seedpod weevil – specifically, a parasitoid wasp that is a natural predator of the insect pest. The wasp has been used successfully in Quebec, he says, but researchers will need to assess its suitability for Western Canada.

Meers says that although researchers must tread carefully when it comes to introducing a new insect to a region, it’s exciting to imagine an overall decrease in spraying for cabbage seedpod weevil.

“Every year (with 2017 being an exception) most of the early canola is sprayed, and there’s just a standing recommendation to spray,” he says. “It would be nice to have some other tools in the toolbox.”

Research confirms DNA of Verticillium longisporum for the first reported farm in North America.

by Donna Fleury

The fungal disease Verticillium longisporum was first detected in Canada in a canola field on a farm in Manitoba in 2014. The results of a subsequent national survey led by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) and released in 2016, detected the presence of the pathogen V. longisporum in varying levels in six provinces in Canada: British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec. To date, the pathogen doesn’t appear to be causing serious production or yield concerns, however, researchers and the industry are monitoring and learning as much as they can about this pathogen.

Researchers at the soil ecology lab at the University of Manitoba took an in-depth look at the pathogen at the location of the first report in Canada (and in North America) to learn more about the pathogen and its distribution. Led by Mario Tenuta, professor of applied soil ecology with graduate student Abhishek Agarwal, the project has provided some interesting preliminary results.

“The objectives of this project were to determine the dispersal

and distribution of the pathogen on the farm where the disease was first discovered on canola,” Tenuta explains. “We also wanted to determine the V. longisporum lineage to better understand the pathogenicity and disease causing ability of this disease in canola in Canada. This soilborne fungal pathogen causes the disease Verticillium stripe in rapeseed in Europe, and could potentially be quite virulent on canola.”

A series of Google Earth images of the farm from 2002 to 2014 were used to identify areas of the farm that were cropped differently in any given year. Sub-fields with a unique cropping history were identified and soil samples taken from each area.

“The farm has a history of supporting a number of variety trials and other projects, so we wanted to understand how the pathogen arrived on the farm and whether it was dispersed across the farm or not,” Tenuta says. “The farm was divided into 58 unique fields for soil sampling, with a total of 191 samples

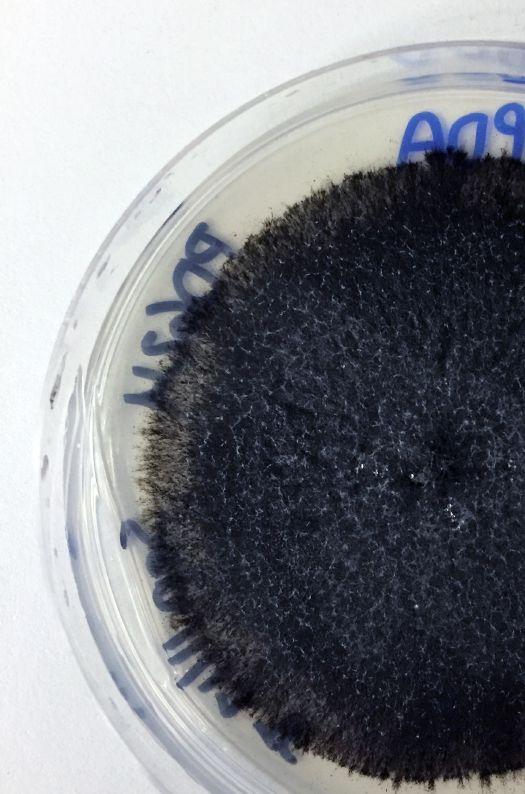

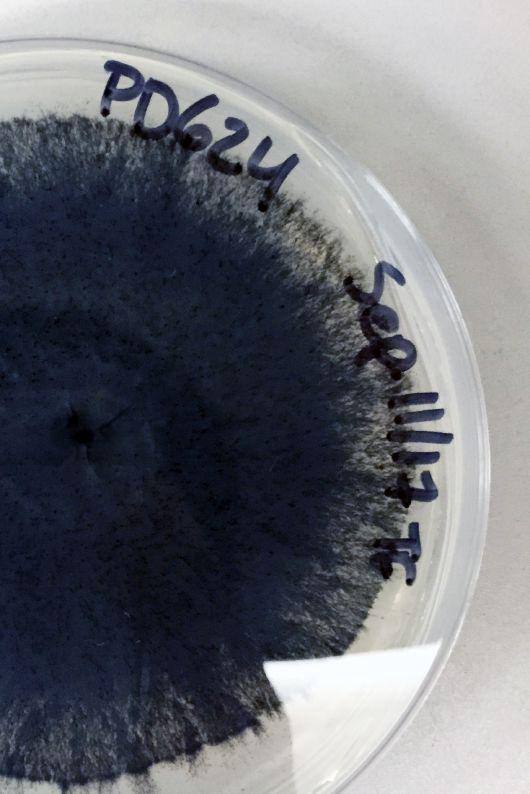

ABOVE: Lab culture of V. longisporum pathogen collected from research plots.

NO ONE CARES MORE ABOUT PRESERVING THE LAND THAN THE PEOPLE WHOSE LIVELIHOODS DEPEND UPON IT.

As the world’s population continues to grow, so does the demand for more efficient and effective farming practices. At Koch Agronomic Services, we’re focused on providing real solutions that maximize plant performance and minimize environmental impact. Like AGROTAIN® nitrogen stabilizer. It protects your nitrogen and your yield potential. A smart solution for today – and tomorrow. To learn more, visit agrotain.com.

analyzed. The analysis was completed using a method we had developed in our lab for quantifying V. longisporum in the plant, and in the soil-based on DNA using a real PCR method. We are in the process of publishing the method to be available for any lab to use.”

The results showed that out of the 191 samples examined, 128 samples, or about two-thirds, were considered positive for the pathogen. Although generally the pathogen levels were low in most locations, a few locations had very high concentrations, including the first location it had been detected. “This information tells us that the fungus moves around and is easily dispersed in the soil, which falls in line with the CFIA survey that discovered the fungus distributed across much of the canola

growing areas in Canada,” Tenuta says. “We also compared the cropping history of the various fields, but we were unable to find any kind of relationship between cropping history and the level of pathogen in the soil. For example, one site had not had canola since 2003, but still tested positive for the pathogen.”

A second part of the project focused on the genetics of the fungus isolate from the farm to try and identify where it originated. V. longisporum is a hybrid fungus, with three possible hybrids identified so far globally. Tenuta explains that V. longisporum is a diploid hybrid of either of two species of V. dahlia (parental lines D2 or D3) and also either of two other unknown species (A1 or D1). The known lineages globally are A1/D1, A1/ D2 and A1/D3, with A1/D1 known to be

the most virulent on canola and the one that has been found in the European Union to be most pathogenic of rapeseed. The analysis confirms that the pathogen at the Manitoba farm is A1/D1, which warrants further examination of the pathogenicity and disease causing ability of this pathogen.

Tenuta adds that so far, there doesn’t appear to be any yield decline or loss at the farm where the pathogen was discovered. “After the discovery, the farm was under quarantine for two cropping seasons and has since developed a strict biosecurity program that controls the movement of visitors, vehicles and equipment on the farm. Visitors can only park at one place, and only designated farm vehicles are allowed to travel between fields. Similar to clubroot disease management, minimizing soil movement, sanitizing and cleaning equipment before it is moved and other practices to prevent the further spread of the V. longisporum pathogen are being followed.”

The project is nearing completion, with the analysis and final results available in the next few months. Overall, the results suggest that V. longisporum can be expected to easily disperse within and between canola fields and studies to determine yield impacts should be done. The study also confirmed that the hybrid present for this first reported farm of Verticillium stripe of canola in North America is that which is most aggressive on the crop, A1/D1.

“With the potential pathogenicity of this pathogen, conducting a more thorough examination of this pathogen in the different growing areas and verifying whether or not it is a potentially damaging disease is important,” Tenuta says. “Studies could be conducted to see if the levels of the pathogen can be built up in soil, and if under high levels can develop disease and yield loss. If yield loss does occur, then an assessment of the current genetic material of canola, and whether or not there are differences in disease resistance would be important. Therefore, if a problem does development, we may have canola lines in place that could help reduce any potential losses. We now have better knowledge and ability to understand this pathogen, and will work with industry on any next steps.”

There’s nothing quite like knowing the worst weeds in your wheat fields have met with a fitting end. Following an application of Luxxur ™ herbicide, you can have peace of mind that your wild oats and toughest broadleaf perennials have gotten exactly what they deserve.

SPRAY WITH CONFIDENCE.

Fusarium head blight research for yield, quality and safety of Prairie oats.

by Carolyn King

Although oats are less susceptible than other cereals to Fusarium head blight (FHB), this disease can impact oat yield and quality when conditions strongly favour the disease – as they did on the Prairies in 2016. So, researchers are working to better understand FHB in oat, to develop oat varieties with even stronger FHB resistance, and to help ensure the grain remains safe for humans and livestock.

FHB in oats presents some intriguing challenges for researchers. Oat breeder Jennifer Mitchell Fetch calls FHB a “sly foe” because the symptoms in oats aren’t usually easy to see, making disease levels hard to evaluate in the field. Another complexity is that several different Fusarium species can cause FHB in Prairie oat fields. Furthermore, these species have the potential to produce fungal toxins, and these mycotoxins differ from species to species.

Researchers conduct annual surveys to track FHB in commercial oat crops on the eastern Prairies. The surveys started in 2002 in Manitoba and in 2004 in Saskatchewan. Since 2014, the Manitoba surveys have been led by Xiben Wang, a cereal pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Morden, Man. His team looks for visual symptoms of FHB, such as orange-pink or other discolouration of the oat spikelets in randomly selected oat fields, and analyzes oat samples from these fields using such techniques as qPCR (quantitative polymerase chain reaction) to identify and quantify the different Fusarium species.

“We find that FHB is pretty common in the surveyed oat fields,” Wang says. For instance, Fusarium infection was detected in all of the 49 fields surveyed in 2015 and all of the 43 fields surveyed in 2016.

He notes, “Fusarium poae is the most common species, followed by Fusarium graminearum and then Fusarium sporotrichioides in third place.” Other detected species include F. avenaceum and F. equiseti

Usually more than one Fusarium species occurs in an oat field. “For example, in our 2016 survey, we found roughly more than 50 per cent of fields were infected with more than three Fusarium species. About 30 per cent were infected with two, and only about 10 to 15 per cent of fields were infected with a single Fusarium species.”

University of Saskatchewan researchers are currently leading the annual surveys for FHB in Saskatchewan oat crops. Fusarium is commonly detected in the surveyed fields. For example, Fusariuminfected kernels were found in 22 out of 31 oat fields in 2015, and 18 out of 30 fields in 2016. F. poae is usually the most commonly detected species, followed by either F. graminearum or F. avenaceum

Other species detected in recent years include F. culmorum, F. sporotrichioides and F. equiseti.

Surveying along the grain handling chain

Sheryl Tittlemier, a research scientist at the Canadian Grain Commission (CGC), is studying Fusarium species in oats as part of a larger project on several problem fungi in western Canadian oats. Her project has two components. The first is disease surveillance (determining the presence of the different fungal species and their mycotoxins), and the second is assessing how processing affects the presence of the mycotoxins and the fungal species in the grain. For the disease surveillance work, Tittlemier and her collaborators

are analyzing oat samples obtained from 2014 to 2017. The samples are from three types of sources along the grain handling chain. “One source is the CGC’s Harvest Sample Program; these samples are voluntarily submitted by producers in the envelopes that are sent out every harvest. We’re also getting samples from some processing facilities; these samples represent weekly composites of oat deliveries to a facility. And then we’re getting samples from some grain handling companies; these samples are also composites and represent the oats being loaded onto a train for shipment,” says Tittlemier, who is head of the Trace Organics and Trace Elements Analysis section of the CGC’s Grain Research Laboratory. The number of samples ranged from about 114 in 2014 to more than 170 in 2017. Tittlemier’s team is analyzing the 2017 samples now.

“The predominant fungal species that we’ve been seeing are Alternaria species, which can be associated with mildew or various leaf diseases. Next are the Fusarium species,” Tittlemier says. “Fusarium poae is the most predominant Fusarium species that we’ve seen, followed by Fusarium graminearum. Fusarium avenaceum is less frequently detected.”

She notes, “Generally – and we see this with wheat as well – we tend to see Fusarium more in the eastern part of the Prairies. But we also see differences from year-to-year due to different growing conditions.”

The oat samples are analyzed for more than 20 different mycotoxins. Each Fusarium species produces various toxins, including deoxynivalenol (DON), nivalenol and zearalenone. DON, which is mainly produced by F. graminearum, is the most well-known Fusarium toxin; safe limits have been established for DON in food and feed.

“Overall, the mycotoxin concentrations are quite low, a lot lower than we’ve seen with wheat,” Tittlemier says. “The pattern of mycotoxins is consistent with the pattern of the fungal species. For instance, the mycotoxins associated with Fusarium avenaceum are found more often in those areas of central Saskatchewan where Fusarium avenaceum is more common.”

When the sample analysis is completed, Tittlemier and her team will analyze all the data, looking at the trends over the years and the geographical patterns, to create a complete picture of their findings.

The findings from the project’s processing component differ somewhat

from the results of previous research by Mitchell Fetch in the early 2000s. Mitchell Fetch says, “We found that dehulling –removing the hull from the oats – removed at least half of the DON. Then, when we steamed them and kilned them, like a miller would do before flaking the oats or grinding them into flour, the DON disappeared below any detectable level with the technology we had at that time.”

Tittlemier’s original approach was to conduct the processing analysis in 2015, examining the effects of the different

processing steps from dehulling, to heating, to milling. However, the 2015 oat samples had very low mycotoxin concentrations to begin with, and after dehulling, no mycotoxins could be detected on the oats. So, the team couldn’t proceed with the other processing steps.

With the much higher FHB presence on the Prairies in 2016, Tittlemier decided to see if they could evaluate the effects of the later processing steps using some 2016 samples. “However, we still found that the bulk of mycotoxins were removed during

The easy way to manage your farm.

Analyze your data. Plan your strategy. Then track your performance. AgExpert Field gives you the details you need to know to make the best business decisions.

It’s all new. And seriously easy to use. Get it now and see.

fcc.ca/AgExpertField

hulling; for example, about 90 per cent of the DON concentration was removed in the hull,” she says.

Tittlemier’s project is funded by the Prairie Oat Growers Association (POGA) and the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture through the Canada-Saskatchewan Growing Forward 2 bilateral agreement. The project is also supported by the CGC, and involves the Grain Research Lab’s microbiology and milling research groups, along with Tittlemier’s section. She also notes, “Without producers sending in samples to the Harvest Sample Program, and the processing facilities and the grain handling companies that have been supplying us with samples, we wouldn’t be able to do this work.”

One of the objectives in the oat breeding program lead by Mitchell Fetch is to develop lines that are less susceptible to Fusarium infection. Ideally, she would like to develop varieties that are immune to FHB and don’t produce any Fusarium toxins. “I’m not sure that will be possible because we have not found anything yet that is completely immune to Fusarium head blight, but hope is always there,” says Mitchell Fetch, a research scientist with AAFC at Brandon.

To screen for FHB resistance, Mitchell Fetch’s research group grows the early generation lines in a Fusarium oat nursery, which is run by Wang. He says, “We use corn infected with different Fusarium graminearum isolates including both 3-ADON and 15-ADON chemotypes [the two main types of F. graminearum on the Prairies]. In this nursery, we are also assessing FHB resistance in the lines that are in the western co-op trials and some of the commercial varieties available on the market.”

Fusarium symptoms are very hard to use for assessing disease levels in oats, so the researchers currently rate the lines based on the DON levels in the grain, which are determined using ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) tests. However, the Fusarium nursery and the ELISA testing are expensive and labour intensive. “We are trying to see whether we could do some greenhouse test looking at seedling resistance, and also if we could do some Petri plate tests looking at the reactions of the plants to different Fusarium species and then seeing whether we can correlate the reactions to the plants’ resistance,” Wang says.

In recent years, Mitchell Fetch has developed several varieties with superior FHB resistance. These are currently rated as ‘moderately resistant’ because Mitchell Fetch and Wang hope to develop varieties with even better resistance. Examples include Stride and Leggett, both developed by Mitchell Fetch, and OT3087, a not-yet-named variety developed by Aaron Beattie at the University of Saskatchewan.

Wang is conducting several studies to better understand FHB in oats. Some of this research involves characterising the disease complex in oats. “From our field surveys, we find the FHB complex affecting oat is much more diverse than FHB on wheat,” Wang notes. “It is quite common to find more than one Fusarium species infecting a single oat plant.” So, his team is working on identifying which species are found together, determining the plant’s mechanism for resisting each species, studying the ability of each species to produce toxins in oats, and exploring if the different species are interacting with each other in ways that might affect the disease’s impacts in oats.

He adds that, at present, not much is known about F. poae, F. sporotrichioides and F. avenaceum and their impact, virulence and toxigenic potential in oats, even though F. poae in particular is common in Prairie oat fields.

The Fusarium infection process is another area of interest for Wang. “At present, we are using wheat and Fusarium graminearum as a model system to study the mechanism of some other Fusarium species infecting oat, for example F. poae. And we have been looking at the similarities and differences between infection of wheat by Fusarium graminearum and oat by Fusarium graminearum, for example.”

Wang is also starting to look into the genetics of FHB resistance in oat. He explains that the resistant and susceptible oat lines identified through the disease nursery work can be used to develop ‘mapping populations.’ By crossing resistant and susceptible lines, researchers can create populations of plants with different levels of FHB resistance, and these populations can be used in mapping the regions of the oat genome that play a role in FHB resistance.

A few years ago, Mitchell Fetch crossed adapted Prairie oat lines with lines from Norway that were reported to be more resistant to FHB in Norway’s growing conditions. From those crosses, she created inbred lines that she hopes can be used in studies to increase understanding of Fusarium infection and toxin production in oats.

Wang’s studies on Fusarium in oats are funded by AAFC, and POGA, partly through POGA’s funding for Mitchell Fetch’s oat breeding program. Summing up the current situation, Wang says “oat growers should be aware that FHB is pretty common [especially in the eastern Prairies in recent years], but there is no reason to panic. We have pretty good resistance in the majority of our commercial lines, and FHB severity in oat is relatively low compared to the levels in wheat and barley. And even if FHB infection should become an issue in oat, research shows dehulling gets rid of most of the toxins.”

What should oat growers do when conditions favour FHB? “In a high disease pressure year, you can definitely see the disease in oats. In those years, your management practices would be similar to practices for managing Fusarium in the other cereals,” says Holly Derksen, field crop pathologist with Manitoba Agriculture. These practices include applying a fungicide at anthesis, choosing oat varieties with good FHB resistance, and using a crop rotation in which cereals are followed by broadleafs.

Derksen notes that crop rotation is especially important when Fusarium inoculum levels are high. “We had a good example of that in 2017. It was a much drier year than 2016, but inoculum levels were high because we had so much disease in 2016. Because of those high inoculum levels, we saw more Fusarium disease in 2017 than we necessarily expected, especially in small plots like our variety trials that don’t receive a fungicide.”

Another recommendation from Derksen is to get your oat seed tested if you are saving seed from a growing season with high disease pressure. “Because Fusarium is not as easy to see in oats, you might assume you don’t have the disease. But if you are saving that seed and you don’t normally use a seed treatment for oats, then you might have problem with germination,” she explains.

“If you have Fusarium in your other cereal crops, then it may be in your oats as well. So, get the oat seed tested to find out whether you have a Fusarium issue. After the 2016 year, I saw oat seedlots with as high as 20 per cent Fusarium infection. If you don’t normally treat your oat seed with a seed treatment, you may want to consider it in that type of situation.”

Richardson is committed to ensuring reliable and efficient services for our customers.

From increasing storage capacity to adding high-speed fertilizer blenders across our Richardson Pioneer network, we continue to invest in our facilities to enhance our operations and serve our customers. We are committed to operating the most efficient, fully integrated network of high throughput grain elevators and port terminals to move your grains and oilseeds from the Prairies to markets around the world.

Being truly invested is at the heart of everything we do. To learn more, visit richardson.ca

It’s time to get territorial. Strike early, hard and fast against your toughest broadleaf weeds.

Lethal to cleavers up to 9 whorls and kochia up to 15 centimeters, Infinity ® FX is changing the landscape of cereal weed control.