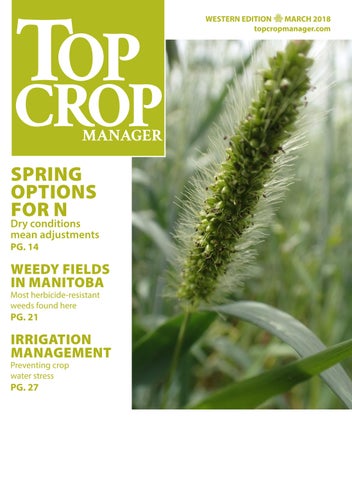

TOP CROP MANAGER

SPRING OPTIONS FOR N

Dry conditions

mean adjustments

PG. 14

WEEDY FIELDS IN MANITOBA

Most herbicide-resistant weeds found here

PG. 21

IRRIGATION MANAGEMENT

Preventing crop water stress

PG. 27

Dry conditions

mean adjustments

PG. 14

Most herbicide-resistant weeds found here

PG. 21

Preventing crop water stress

PG. 27

| Spring N application tips Adjustments may be required for the Prairies. By Bruce Barker

Herbicide resistant weed monitoring

survey highlighted increased resistance in grass weeds versus broadleafed weeds.

Julienne Issacs

| Improving management strategies

to basics to ensure healthy crops.

Ross McKenzie, PhD, P.

JANNEN BELBECK | ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Dealing with weeds? Of course you are. And thanks to the ever-evolving nature of weeds, what you dealt with in 2017 might not help you with what could happen in 2018. Of course lessons are learned, but as a producer, your goal should always be to learn more, stay informed and be diligent – otherwise your crop yields (and your bottom line) suffer.

That’s why Top Crop Manager strives to provide our readers with the latest research and commentary from industry experts in the field, and our annual weed management-focused edition is no different. The pages this issue are filled with articles on integrated weed management, weed management systems, plus coverage of weed surveys readers like you have completed.

We have a fun infographic on page 44 highlighting some of the responses from our first-ever herbicide use survey. The editorial team from Top Crop Manager worked hard to develop the survey, and sought to find out information related to the following topics: weed conditions and resistance; the important factors in weed management decisions; weeds targeted and herbicide groups applied; and the practices used to manage weeds. Nearly 500 of you across Canada completed the survey and helped give us a glimpse at what the state of herbicide resistance is like in the country today.

With regards to weed management specifically, one of my favourite stories this issue has to be our opening story on page 6. Ross McKenzie takes readers through a list of integrated weed management techniques, and includes everything from crop rotations, to seed sources, to tillage. But first, he stresses the important fact that even the chemical companies themselves have begun to push within the last couple of years: “Rotating herbicides based on modes of action is necessary to prevent or delay development of herbicide-resistant weeds. For each herbicide used, be sure to pay attention to the mode of action (herbicide group number).”

Although citing it as “unpopular opinion,” one of our Twitter followers mentioned that although herbicides are a dominant tool for weed control, does focusing on herbicide resistance make us “forget” about all the other traits that make weeds successful? And maybe the focus of weed control is changing – there may be more tools in the toolkit than we actually realize. For example, within the realm of breeding and genetics of crop varieties, are there ways we can harness the power of weeds?

Digging through this issue, I think readers will be surprised and inspired to find a number of strategies that can be implemented to manage weeds. We’re happy to continue providing growers and agronomists with this exciting news.

Lastly, I’d like to extend a warm “welcome back” to editor Stefanie Croley, as she returns from maternity leave to resume her role as editor with Top Crop Manager. Together, we hope you have a wonderful spring season.

2018, VOL. 44, NO. 3

ASSOCIATE

Jannen Belbeck • 888.599.2228 ext 211 C - 226.931.5608 jbelbeck@annexweb.com

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jennifer Paige • 1 888 599 2228 ext 277 C - 416-305-4840 jpaige@annexweb.com WESTERN FIELD EDITOR Bruce Barker • 403.949.0070 bruce@haywirecreative.ca

ACCOUNT MANAGER Danielle Labrie • 888.599.2228 ext 245 C – 226.931.0375 dlabrie@annexweb.com NATIONAL ACCOUNT MANAGER Michelle Allison • 1.204.596.8710 mallison@annexweb.com ACCOUNT COORDINATOR Alice Chen • 416.510.5217 achen@annexbusinessmedia.com

MEDIA DESIGNER Brooke Shaw

CIRCULATION MANAGER Urszula Grzyb • 416-442-5600 ext. 3537 ugrzyb@annexbusinessmedia.com

VP PRODUCTION/GROUP PUBLISHER Diane Kleer • 519.403.8816 dkleer@annexbusinessmedia.com COO Ted Markle • tmarkle@annexbusinessmedia.com

PRESIDENT & CEO Mike Fredericks Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

CIRCULATION

email: rthava@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 416.442.5600 ext. 3555 Fax: 416.510.6875 or 416.442.2191 Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues Feb, Mar, Mid-Mar, Apr, June, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $47.50 Cdn. plus tax Top Crop Manager East – 7 issues Feb, Mar, Apr, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $47.50 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada –

NO ONE CARES MORE ABOUT PRESERVING THE LAND THAN THE PEOPLE WHOSE LIVELIHOODS DEPEND UPON IT.

As the world’s population continues to grow, so does the demand for more efficient and effective farming practices. At Koch Agronomic Services, we’re focused on providing real solutions that maximize plant performance and minimize environmental impact. Like AGROTAIN® nitrogen stabilizer. It protects your nitrogen and your yield potential. A smart solution for today – and tomorrow. To learn more, visit agrotain.com.

Herbicides are just one of many tools growers can turn to for effective weed control.

byRoss McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag.

Herbicides have become very important for weed control. However, frequent and repeated use of the same herbicide groups has gradually resulted in development of herbicide-resistant weeds to the point that resistance has become a very serious problem for many Prairie farmers. When herbicide resistance is a relatively minor problem, growers tend to pay less attention to managing it than they should. Once resistance starts affecting a major weed or a major herbicide used on the farm, then growers pay more attention to the herbicide group number on the label.

For each herbicide used on your farm, be sure you are aware of and understand the mode of action. This is the way an herbicide controls susceptible plants. Specifically, it is how the plant processes are affected by the herbicide – which biological process or enzyme in the plant the herbicide interrupts, and how this affects normal plant growth and development. In some cases, the mode of action may be a general description of the injury symptoms observed on susceptible plants. Each mode of action has a unique herbicide group number.

Simply rotating herbicide active ingredients is not enough to prevent the development of herbicide-resistant weeds. Rotating herbicides based on modes of action is necessary to prevent or delay development of herbicide-resistant weeds. For each herbicide used, be sure to pay attention to the mode of action (herbicide group number). See table 1 on page 10 for examples in Groups 1 and 2.

Rotating herbicide active ingredients means more than just rotating herbicide brands. Products with different names, or from different companies, may have the same mode of action and herbicide group number. Growers must take great care to ensure that changing from one herbicide manufacturer to another doesn’t result in a continued application of herbicides with the same mode of action.

As I mentioned, each mode of action has a different herbicide group number. Different herbicides with the same chemical group number may not control the same weeds. Products may have a combination of herbicide chemistries or registered tank-mix combinations that allow them to control additional weeds, but if the group number is the same, the basic herbicide chemistry is the same and repeated frequent use will result in increased risk for developing herbicide resistance.

Each provincial department of agriculture provides detailed information on herbicide group classification by mode of action, which lists the herbicide groups (chemical family), active ingredients and the herbicide product names in which the active ingredients are found. The information is available on department websites and crop protection publications. For more information on herbicide

ABOVE: For each field, identify which weeds are present and the relative populations of each weed.

group numbers and herbicide rotation, contact your provincial crop specialist or ag information centre. Herbicide companies and private agronomists are also excellent sources of planning information.

In Western Canada, growers who have consistently used best integrated weed management practices have fewer herbicide-resistant weed issues on their farms. What these farmers are doing differently to avoid the development of weed resistance versus other farmers, is that most are using a combination of integrated weed management to try to combine chemical, cultural, mechanical, biological or other practices in a proactive cropping system to enhance long-term sustainable crop production.

Here are some key integrated practices to review:

Identify all weeds present on your farm. For each field, assess which weeds are present and their relative populations. Determine the biology and life cycle of each weed (e.g. annual, biennial or perennial).

When the weather cooperates, getting rid of weeds with a pre-seed burndown is one of the best crop production strategies. Young weeds are easier to control at this stage, and the emerging crop will compete better for sunlight, water and nutrients. And ultimately, crops have a stronger start that leads to better yields at the end of the season.

Early weed removal is also a benefit to in-crop spraying and reduces the risk of out-growing their window of application for other herbicides. Weeds that get away and reach maturity can produce hundreds and even thousands of seeds that can create future challenges in any field.

But how you remove weeds is just as important as why. Herbicide weed resistance is a growing reality, and resistance management must be a critical part of every weed control strategy, regardless of when you spray.

Weeds are smart and quick to adapt to herbicides with repeated use. If you’re using a single mode of action for weed control, weeds can develop resistance after as few as five applications. That’s why it’s critical to use a multiple mode of action defense strategy. It’s impossible to prevent weeds from developing resistance, but it can definitely be slowed down using a sound herbicide management strategy.

Nufarm Agriculture Inc. leads the industry with pre-seed burndown solutions that deliver effective weed control options with multiple modes of action as part of a solid herbicide resistance management strategy.

In canola, CONQUER® delivers faster, complete control in a pre-seed burndown than glyphosate alone. CONQUER contains two active ingredients (Group 6, 14) with two modes of action. And in a tank mix with glyphosate, you’ll be getting three modes of action to tackle tough weeds like kochia, cleavers, and volunteer canola including glyphosate and Group 2-herbicide tolerant biotypes.

Chickweed

Cleavers

Dandelion (spring germinated)

Flixweed

Horsetail

Kochia

Lamb’s-quarters

Plus many more.

Redroot pigweed

Smartweed

Stickweed

Shepard’s purse

Tansy mustard

Volunteer canola (including glyphosate-tolerant)

Please consult the label for more information.

• eliminates weed competition for emerging crops

• provides ideal time to control small weeds and fall-germinated winter annuals

• can help reduce weed seed production

• reduces the risk of spraying when weeds are out of their ideal window of application

• always use herbicides with multiple modes of action for resistance management

CONQUER® is the only multiple mode of action pre-seed burndown product that battles resistant weeds and all types of volunteer canola, Group 2-resistant cleavers and kochia – as well as other hard to kill weeds. Plus, it helps prevent the spread of Group 9 resistance. Before seeding, add CONQUER to your glyphosate and double up on your weed fighting capabilities.

WHY JUST CONTROL WEEDS, WHEN YOU CAN CONQUER THEM.

Editor’s note: On page 6 of the March 2018 edition of Top Crop Manager West, we published a story entitled “Integrated weed management” by Ross McKenzie. Accompanying the story was a chart comparing Group 1 and Group 2 herbicide chemical families, active ingredients, and examples of herbicides. In this chart, Outlook herbicide was incorrectly listed as a Group 2 herbicide, when it is in fact a Group 15 herbicide. The chart below has been updated based on information from the 2018 Alberta Blue Book, and the full chart can be found on the Alberta Agriculture website. We apologize for the error.

Table 1. Group 1 and 2 herbicide chemical families, active ingredients, and examples of herbicides.

Herbicide Group Classification by Mode of Action

Chemical family Active ingredients Found in*

GROUP 1 Inhibitors of acetyl CoA carboxylaseACCase. These chemicals block an enzyme called ACCase. This enzyme helps the formation of lipids in the roots of grass plants. Without lipids, susceptible weeds die.

Aryloxyphenoxy propionate (Fop)

Cyclohexanediones (Dim)

clodinafop propargyl Bullwhip, Cadillac, Cougar, Foothills SG, Harmony Grass 240 EC, Horizon SG, Ladder, MPower Aurora, NextStep SG, Signal, Signal FSU, Traxos fenoxaprop-p-ethyl Bengal, Cordon, MPower Hellcat, Puma Advance, Puma Super, Tundra, Vigil, WildCat quizalofop-p-ethyl Assure II, IPCO Contender, Yuma

clethodim Antler 240 EC, Arrow 240 EC, Centurion, Patron, Select, Shadow RTM

sethoxydim Poast Ultra, Odyssey Ultra/Odyssey Ultra NXT tralkoxydim Bison, Liquid Achieve, Marengo, Nufarm Tralkoxydim Phenylpyrazolin (Den) pinoxaden Axial, Axial iPak, Axial Xtreme, Broadband, Traxos, Traxos Two

GROUP 2 ALS/AHAS inhibitors. These chemicals block the normal function of an enzyme called acetolactate (ALS) actohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS). This enzyme is essential in amino acid (protein) synthesis. Without proteins, plants starve to death.

Imidazolinones

AC 299, 263, 120 AS Altitude FX imazamethabenz Assert 300, Avert imazamox Ares, Altitude FX2, Salute, Solo/Solo ADV, Viper imazamox + imazethapyr Odyssey/Odyssey NXT, Odyssey Ultra/Odyssey Ultra NXT imazapyr Arsenal, Ares, Salute imazethapyr Gladiator, Multistar, MPOWER Kamikaze, Nu-Image Herbicide, Phantom, Pursuit

Sulfonylaminocarbonyltriazolinones flucarbazone sodium Everest, Inferno Duo

Sulfonylureas chlorsulfuron Telar, Truvist ethametsulfuron methyl Muster halosulfuron Permit

metsulfuron-methyl Accurate, Ally Toss-N-Go, Escort, Express Pro, Nuance Pro, Reclaim/Reclaim II, Travallas nicosulfuron Accent rimsulfuron Prism, Titus Pro

thifensulfuron-methyl Barricade II, Boost, Broadside, Deploy, Nimble, Predicade, Refine SG, Retain, Travallas, Triton C tribenuron-methyl Barricade II, Boost, Broadside, Deploy, Express FX, Express Pack, Express Pro, Express SG, FirstStep Complete, Inferno Duo, Inferno WDG, KoAct, Luxxur, MPower R, MPower X, Nimble, Nuance, Nuance Pro, Predicade, Refine SG, Refine M, Retain, Signal FSU, Triton C, Triton K triflusulfuron methyl UpBeet

Pyrazole halosulfuron Permit

florasulam

Triazolpyramidines

Benchmark, Blitz, Broadband, Cirpreme, First Pass, Frontline XL, Frontline 2,4-D, Hotshot, Korrex II, Outshine, Paradigm, PrePass, PrePass Flex, Priority, Spectrum, Spitfire, Stellar/Stellar XL, Topline pyroxsulam Simplicity/Simplicity GoDRI, Tandem Triazolones thiencarbazone-methyl Luxxur, Predicade, Varro, Velocity m3

Source: Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/prm6487 *A herbicide may appear in more than one group if it contains more than one active ingredient

Have herbicide-resistant weeds been identified in any of your fields? If so, determine the group number of the resistance and note all herbicide products with that group number to ensure use is restricted.

Assess the herbicides at risk on your farm

For each field, determine the number of applications of each herbicide group in the past 10 years (or more, if you have good field records). Identify any herbicides that have been frequently, or over-used on your farm. Are any of theses herbicides in the moderate- or highrisk groups for developing resistance (Groups 1, 2, 3, or 8)?

Develop a plan to avoid applications of frequently and over-used herbicides in the future.

Use at least a four-year crop rotation including cereal, oilseed and pulse crops to disrupt weed growth and life cycles. More diverse rotations also allow a wider range of herbicide groups to be used for weed control.

Using both winter wheat and spring wheat (or other winter crops) with different life cycles in a diverse crop rotation helps disrupt the life cycles of weeds and therefore can aid in weed control. Keep in mind that winter annual weeds can become a greater problem if the frequency of winter crops in the rotation increases.

Long-term crop rotations that include annual crops and perennial forage crops in the rotation are ideal. Forages are excellent for competing with weeds and interrupting weed

life cycles. Forage crops are also very beneficial to improve soil quality and build soil organic matter. Ideally, continuous cropping is best for effective weed competition.

Ensuring seed is meticulously cleaned is very important to prevent importing new weed species onto your farm.

Using certified seed is a very good practice to consider, but be aware of the types of weed seeds in the certified seed. Check the certificate of analysis, which shows any weed seeds present.

Using high-quality seed is also important. Test your seed for germination and vigour – plump seed is often more vigorous and competitive.

Seed each crop as early as is reasonable to give the crop a head-start over weeds.

Review the seeding rates you use for each crop. Consider shifting to a slightly higher seeding rate to increase crop competition with weeds. Also consider using seeding equipment with a seedrow spacing as narrow as is reasonable to be more competitive with weeds.

Seed each crop as shallow as is reasonable for rapid germination and emergence.

Place fertilizer with seed or near seed at safe rates to give crops easy access to nutrients and promote healthy, vigorous plant growth.

Zero tillage will minimize weed seed incorporation into soil, which is a good aid to assist with cultural weed control.

In situations where considerable weed pressure occurs, tillage may be appropriate for weed control, but always keep in mind the importance of soil conservation!

Removal of weeds by hand may be useful for removing small weed patches or weeds that are hard to control.

Extensive research in Western Canada has shown yields of most crops are optimized when weeds are removed earlier with herbicides versus later.

This is critical: Rotating herbicide use must be done by herbicide group number. Simply rotating herbicides within the same group number is not herbicide rotation. Herbicides within the same group have the same mode of action. Therefore, herbicides must be rotated based on group number.

An herbicide mixture is more effective in delaying development of herbicide resistance when the less resistance-prone herbicide controls a similar spectrum of weeds as the more prone herbicide. Both herbicides should have similar persistence to control the same weed flushes, but the two mixed herbicides must have different modes of action.

Planting an herbicide-resistant crop like canola has become a common technique for

managing Group 1- and 2-resistant grassy and broadleaf weeds. Varieties with stacked traits provide a different mechanism for resistant weed control.

At harvest, consider using a chaff wagon to collect weed seeds blown out the back of the combine and prevent spreading weeds back onto the field.

These are just some of the practices to consider in order to improve integrated

weed management on your farm. Herbicides will continue to be the dominant method to control weeds, but keep in mind the importance of preventing new weeds from being imported onto your farm and the various cultural practices you can utilize for weed management. To keep herbicide resistance in check, Prairie farmers must use the highest possible level of integrated weed management. The challenge for our industry is to encourage all Prairie farmers to become very conscientious of using multiple control practices to manage weeds on their fields.

by Donna Fleury

Over the past several years, Neil Harker, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lacombe, Alta., has been investigating integrated weed management systems (IWM), with a focus on wild oat management and control. An early study, Test 42, compared ways of managing wild oat using crop rotation (barley-canola-barley-peas compared to continuous barley), lower herbicide rates, competitive crop cultivars and higher seeding rates. The results showed that diverse crop rotations provided better wild oat control, and required less herbicides if cultural controls such as competitive seeding rates and cultivars were included.

Test 43 followed, incorporating more diverse rotations with various annuals, perennials (alfalfa), winter annuals and early cut silage, comparing competitive seeding rates, with and without herbicides, for wild oat control. The study found that early cut barley silage, or two years of an increased seeding rate of cereals with no herbicide could control wild oat as good as or better than a canola-wheat rotation with 100 per cent herbicide rates.

“Building on Neil’s successful research results, we launched Test 44

in 2016 to look at multiple weed species and various harvest weed seed control methods as part of an integrated weed management system,” explains Breanne Tidemann, research scientist with AAFC. “We are expanding on Test 43, to determine if chaff collection integrated with other non-chemical weed control methods can provide broadleaf and grass control equivalent to typical 100 per cent herbicide application systems. Chaff collection is being added to simulate harvest weed seed control or moving those weeds out of the crop at the harvest timing.”

The project includes a large treatment list, comparing various diversified spring annuals (fababean/pea, wheat/barley, canola), winter cereals (winter wheat, winter triticale, fall rye), perennials (alfalfa) and early cut barley silage rotations using increased seeding rates (1.5 or 2 times recommended rates), with and without herbicides, and incorporating chaff collection. These rotations are being compared to a canola-wheat-canola rotation with 100 per cent herbicides or no herbicides and chaff collection.

“This is a large six-site study across Western Canada comparing

all of the same treatments,” Harker says. “The sites include Lacombe, Lethbridge and Beaverlodge in Alberta, Saskatoon and Scott in Saskatchewan, and the University of Manitoba. In 2016, all of the plots were seeded to wheat using increased seeding rates and no herbicides. The various rotation treatments were implemented in 2017 at the various locations, with two more years of rotations, followed by a final year of wheat across all of the plots to be able to analyze comparisons across all treatments for changes in weeds.”

“For the project, we have expanded the weed spectrum beyond wild oat to look at multiple weed species at the various locations,” Tidemann adds. “All sites include a common grass and broadleaf weed, wild oat and wild buckwheat, but then each site selected other problematic weeds to add to their study. For example, in Lacombe we have included cleavers, while Lethbridge has included kochia. There is some flexibility of weed spectrums to be most reflective of each of the six locations.”

Across all sites, chaff will be collected at harvest using the best method at each location, depending on equipment available. “The objective with chaff collection and removal from the plots is reducing the seed bank,” Tidemann says. “This could be accomplished through chaff collection or other harvest weed seed control methods such as the Harrington Seed Destructor, Seed Terminator or other options. We will be focusing on the changes in weed populations over the duration of the project. We are also going to be testing the chaff for feed quality to see if there are opportunities for feeding the different types of chaff to livestock.”

The overall goal of integrated weed management systems, such as Test 44, is the implementation of multiple tools to reduce herbicide inputs, environmental impact, and selection pressure for weed resistance.

“Although in the short-term the shorter canola-wheat rotations may seem to be more profitable, over the long-term diverse rotations and integrated crop management are necessary to reduce herbicide expenditures, reduce selection pressure for weed resistance, and to continue more sustainable cropping systems and rotations,” Harker says. “Implementing novel, integrated weed management systems can help mitigate herbicide resistance risk, extend the use of important weed control tools and maximize profitability.” Further research results will be available over the next few years.

“I think it was a great decision to use Zone Spray, it’s a very efficient way of applying fungicides and I’d recommend it to other farmers.”

- James Jackson, Grower, Jarvie, Alberta

Just because you can’t walk every acre, doesn’t mean you can’t be there for your farm. Using in-season satellite imagery, Zone Spray enables you to make a more informed decision on which parts of your field are best worth protecting. Once uploaded to your sprayer, Zone Spray maps control the sprayer’s nozzles automatically, turning sections on and off to selectively protect the highest production zones of your crop while optimizing your fungicide application.

Dry conditions going into winter in many parts of the Prairies may require adjustments to N application.

by Bruce Barker

Some Prairie farmers were fortunate enough to have good moisture conditions to band anhydrous ammonia or urea last fall to get a jump on spring seeding. But for the majority of farmers, dry conditions in many parts of the Prairies may mean adjustments to nitrogen (N) applications.

“A couple [of] good snowfalls and/or an early spring rain would do a lot towards replenishing the subsoil moisture before seeding,” says Saskatchewan Agriculture’s provincial soils specialist Ken Panchuk.

1. Make adjustments to yield targets

Should dry soil moisture conditions persist into the spring, Panchuk says farmers need to re-assess their yield targets and adjust their N application rates based on soil test information. Growers who have been pulling off 70-bushel CWRS wheat crops under the good growing conditions of most of the last decade might want to target a lower yield. Generally a wheat crop takes up about two pounds of N per bushel. Dropping a yield target down to 50 bushels could mean reducing N rates.

2. Band still better than broadcast

Generally, spring banding of N, either pre-plant or at time of seeding, produces the highest yields. Alberta research found that spring banding is always equal or better than fall banding and up to 20 per cent more effective under dry soil conditions.

Research in Saskatchewan has shown relatively little difference in agronomic performance of nitrogen fertilizer applied as liquidUAN, anhydrous ammonia or urea at seeding in mid-row or sideband configurations.

“The best strategy is banding fertilizer into the soil. That has become the gold standard in zero-till,” Panchuk says.

All forms of N work well in spring pre-plant banding. Anhydrous ammonia (NH3) should be banded deep enough to prevent application losses, usually about three-to-four inches below the soil surface. However, under strong drying conditions pre-plant banding may potentially delay seedling emergence by disrupting and drying the seedbed.

3. Side-band or mid-row band at seeding

One-pass direct seeding system is the most common practice in Western Canada. Side-band N at seeding often allows application of the entire fertilizer blend in a one-pass operation. However,

Achieving adequate seed and fertilizer separation is critical in dry soils.

information from Manitoba Agriculture indicates that placement of fertilizer one-inch beside and one-inch below the seed may not be sufficient for crop safety. Recommendations for crop safety are for a separation of at least two inches from the seedrow for dry or solution fertilizers and two-to-three inches for anhydrous ammonia.

Mid-row banding with fertilizer placed every second seed row provides good to excellent crop safety, and disc or knife openers help reduce soil disturbance and maintain a residue cover on the surface.

4. Adjust seed-placed fertilizer rates

Should dry seedbed soil conditions persist, Panchuk cautions

Weeds don’t hesitate getting into your field. Neither should you.

Stay ahead of weeds with critical early-season control. Ensuring your crops begin weed-free contributes a lot to your yield and overall profit potential. Protect them right from the start with new Zidua™ SC herbicide. Registered for use in corn and soybeans, it provides residual activity to help manage susceptible germinating weed seedlings before or soon after they emerge from the soil. And thanks to its Group 15 chemistry, Zidua SC also helps manage the rising problem of tough, resistant weeds, including pigweed and waterhemp. Visit agsolutions.ca/ZiduaSC, and waste weeds, not time.

Always read and follow label directions.

farmers to cut back on seed-placed fertilizer because the focus should be on getting the crop to emerge quickly and more uniform. The maximum safe rates of seed-placed nitrogen and other fertilizers vary, depending on seedbed utilization of the opener, row spacing, crop, soil texture and moisture. The safe rate recommendations are based on good to excellent seedbed moisture conditions. Follow your provincial safe rates of fertilizer placed with the seed guidelines.

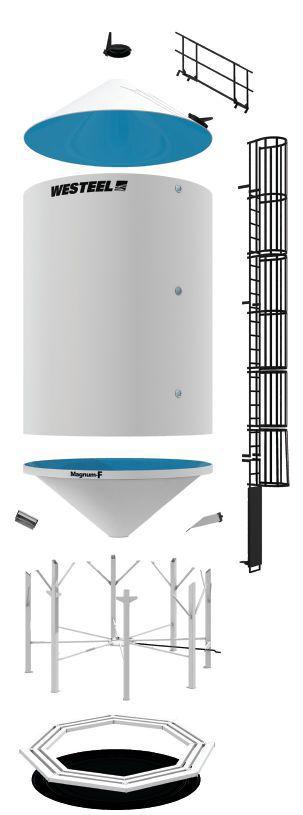

VENTED LID INTERIOR EPOXY COATING (on

INDUSTRIAL GRADE COATING FOR SUPERIOR FINISH PRESSED CONE SHEETS FOR OPTIMUM STRENGTH INSPECTION HATCH

RACK & PINION SLIDE GATE (Stainless Steel Components on Magnum-F™)

5. Surface broadcast applications are risky

Surface broadcast applicators can cover as much as 1,000 acres per day. However, the practice has risks. If the soil surface remains dry, the N could remain stranded above the crop’s rooting zone.

Additionally, surface broadcast urea-N is subject to the risk of volatilization.

Volatilization is the loss of N to the atmosphere as ammonia gas. Urea and urea fraction of UAN solution are subject to volatilization losses, and these losses

&

(on

(Varies

potentially increase with increasing air and soil temperature, increasing wind speed and duration, dropping humidity and light showers followed by rapid drying. Surface broadcasting when soil and air temperatures are cool and when about a half inch of rainfall is imminent reduces the potential volatilization losses.

6. Protect surface broadcast applications to reduce volatilization losses

To reduce the risk of volatilization, a urease inhibitor can be applied to urea or UAN. Urease inhibitors slow the conversion of urea to ammonia and ammonium. This provides a greater chance that rainfall will occur and move the N into the soil.

In studies by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research scientist Cindy Grant (and others) in Manitoba, found that Agrotain (a urease inhibitor) reduced ammonia emission from surface applications. Ammonia losses were higher with urea than UAN because only a portion of the N in the UAN is in the form of urea that is susceptible to volatilization. Grant’s research also found that while urease inhibitors were relatively consistent in reducing volatilization losses, yield benefits were not consistent. Her research showed that benefits are greatest under no-till where surface residues can increase volatilization and immobilization losses.

Immobilization of N can be high when a portion of the surface broadcast nitrogen in direct contact with crop residues is used by soil microbes to decompose the surface layer of residue, tying up the nitrogen, making it temporarily unavailable to the crop. Panchuk says some of the immobilized N will become available (mineralized) later in the growing season, some over the next few years and a portion will remain a component of the soil organic matter complexes for many years. Banding N into the soil minimizes N contact with crop residues for a period of time thus greatly reducing the immobilization risk especially during peak crop demand for N.

At the University of Manitoba, soil scientist Mario Tenuta revisited nitrogen efficiency guidelines from 2014 through 2016 to see if spring banding into the soil was still the most efficient option given the enhanced efficiency fertilizers available today. Urea

a Although spring and fall banded nitrogen were equally effective in research trials, fall banding may be more practical under farm conditions. The extra tillage associated with spring banding in a separate operation from one pass direct seeding may dry the seedbed and reduce yields.

b In research trials conducted in the higher rainfall areas, spring broadcast nitrogen was well incorporated and seeding and packing completed within a short period of time. Under farm conditions, shallow incorporation or loss of seedbed moisture resulting from deeper incorporation may cause spring broadcast and incorporation method to be somewhat less effective than shown here.

Source: Alberta Fertilizer Guide.

was surface broadcast in the fall or spring at 70 and 100 per cent of recommended N. Urea was also applied with Agrotain and as SuperU. Spring application also included shallow-banded one inch deep, and deep-banded three inches deep.

Spring-applied shallow- or deep-banded produced three-to-five bushels per acre higher yield than spring-applied surface broadcast N. Fall surface application of granular urea and enhanced efficiency fertilizer products with urease and nitrification inhibitor at 100 per

cent of provincial recommendation rates had 13 bushels per acre lower yield than spring surface applications of the products.

Tenuta reported that fall subsurface banding of granular urea improves yields compared to surface application, and is much less efficient than spring application. While the enhanced efficiency fertilizers did reduce N2O and NH3 loses, there was no benefit to yield in this ongoing study.

As a risk management tool, applying a portion of N requirements in a side or midrow-band at seeding followed up with a postemergent N application is an option. For example, in trials from 2004 through 2006 at Indian Head, Sask., research scientist Guy Lafond found that a minimum of 67 per cent of target N rate should be applied at seeding of canola. If favourable rainfall occurs after seeding, the balance could be applied as a dribble band of liquid UAN or injected with coulters between the seedrow. The second application should be made within the three-to-four weeks after crop emergence to match the peak uptake period for nitrogen.

Adding a urease inhibitor to UAN and timing the dribble band application with forecast rain will help reduce N volatilization losses. Broadcast urea treated with a urease inhibitor is another option, providing the crop is not too far advanced.

“Seeding equipment flexibility plus several options for managing N needs are available to farmers to best match the seeding conditions going into the spring,” Panchuk says. “Hopefully we get some good snowfalls and/or early spring rain to help reduce some of the risk.”

Do you know how much water your soils can hold?

by Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P. Ag

This is important information for irrigation farmers to decide when to irrigate, but it’s equally important for dryland farmers to understand their soil moisture conditions when deciding on crop input requirements.

The amount of water the soil can retain depends on the texture of the soil. Soil texture refers to the proportion of different sized mineral particles in soil. The soil particles sizes are:

Sand - 2.0 to 0.05 mm in size

Silt - 0.05 to 0.002 mm in size

Clay - <0.002 mm in size

Sand particles are the largest, silt is medium-sized and clay particles are the smallest. The relative proportions of sand, silt, and clay particles affect the pore sizes in soil, which affect the ability to hold and retain water. The proportions of sand, silt and clay determine classes of soil texture, shown on page 20.

Soils with higher amounts of clay have a greater abundance of small pores, and can retain more water than sandy soils that have larger sized pores. In sandy soils with larger pores, water is pulled downward and freely drained from soil by gravity.

Texture can be determined in the laboratory using mechanical analysis or can be estimated by wetting soil and kneading it between the thumb and forefinger using the hand-feel method.

Typically, soil texture can be divided into three main groups: course, medium and fine. Fine textured soils are: clay, silty clay, clay loam and sandy clay. Medium textured soils are: silty loam, sandy clay loam, and loam. Coarse textured soils are: sandy loam, loamy sand and sand. A loam textured soil typically has about 40 per cent of sand, 40 per cent of silt, and 20 per cent of clay.

ABOVE: The amount of water the soil can retain depends on the structure of the soil.

You’ve identified volunteer canola as a weed. Now it’s time to deal with it.

For control of all volunteer canola, tank mix Pardner® herbicide with your pre-season application of glyphosate. Make Pardner your first choice.

Table 1. Approximate available water of various textured soils.

To estimate the water holding capacity of a soil, the soil texture must be known.

A soil is at saturation point when all soil pores are filled with water after a saturating rain. Normally, within a day or two, gravity will pull away free water out of the soil profile and the remaining soil water content is then referred to as field capacity (FC).

Permanent wilting point (PWP) occurs when plants have extracted water to the level that cause plants to wilt and die. The soil water that is between field capacity and wilting point is called plant available water (PAW), which is the amount of water that plants can utilize. There is still a fair amount of water remaining in soil below permanent wilting point but the water is completely unavailable to plants. The figure above shows the relative differences of FC, PWP and PAW for clay loam (fine textured soil), loam (medium textured soil) and loamy sand (course textured soil) soil types.

Table 1 shows the approximate amount of plant available water different textured soils can hold. The values in table one are for soil textural classes in Alberta, which are applicable to the Prairies.

About 40 per cent of the plant available water in soil can be extracted by most crops, without incurring any waterlimiting stress that would affect crop yield

or quality. After about 40 to 50 per cent of the available water is used, it gradually becomes increasingly difficult for plants to extract water.

For irrigation farmers a critical term to understand is allowable depletion (AD), which is the per cent of water that can be removed from soil without significantly affecting crop yield or inducing crop water stress. This water is referred to as the readily available water (RAW). The AD of a soil is the per cent of water that can be removed from a soil between irrigation events without significantly stressing a crop or affecting crop yield or quality. The AD for most crops is about 40 per cent but is less for more sensitive crop such as potato and bean.

The total amount of water available to a crop depends on the water-holding capacity of a soil (table 1) and the effective root zone depth for each crop. The AD will vary with soil type, crop type, stage of crop growth and effective rooting depth of the crop. Allowable depletion is usually determined and expressed in mm per depth of soil. Effective rooting depth and irrigation water management is explained in more detail in “Managing your strategy” on page 27 of this issue.

When a crop is in a moisture deficit condition during vegetative growth, the first effect is a reduction in the growth rate

Source: Alberta Agriculture, 2004.

of leaves and stems. When soil moisture availability is limited, cell expansion and division within the plant slows down. The effect is that plants reduce the production of enzymes and proteins needed for growth.

As soil moisture deficiency increases, plant roots cannot take up enough water to meet transpiration needs. Crops respond by closing stomata. Plant leaves become less rigid and leaves exhibit wilting during mid-day heat. As air temperatures cool and solar radiation decreases later in the day and into the evening, plants recover from wilting as stomata open to meet transpiration needs.

When cereal crops begin wilting at mid-day, older leaves and tillers are gradually aborted, and stem elongation is reduced. When oilseed crops begin wilting, plants respond by abortion of older leaves, reduced stem elongation, reduced branching and flowers are aborted, which in turn reduce crop yield potential.

If soil moisture deficit becomes more advanced, wilting becomes more prolonged each day until plants reach a condition where recovery overnight does not occur, and plants completely senesce and die, which is the soil moisture permanent wilting point. For more on soil and water, visit

The 2016 herbicide resistant weed survey found incidences of herbicide resistant weeds in 68 per cent of fields.

by Julienne Isaacs

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC)’s 2016 herbicide resistant weed survey in Manitoba highlighted increased resistance in grass weeds versus broad-leaf weeds in the province, according to AAFC resistance specialist Hugh Beckie.

Sixty-eight per cent of Manitoba fields had herbicide resistant weeds in 2016, compared with 48 per cent in 2008 and 32 per cent in 2002.

Manitoba has always led the Prairie provinces in terms of frequency of herbicide resistant weeds, Beckie says, even though Saskatchewan is close behind. The 2014/2015 survey in Saskatchewan noted 57 per cent of fields contained herbicide resistant weeds – and the difference between the provinces is getting tighter.

“That gap is closing,” Beckie says.

The herbicide resistant weed survey is a subset of the larger AAFC general weed survey, led by Saskatoon research station biologist Julia Leeson, which is conducted in each of the Prairie provinces roughly every five to ten years.

In 2016, a total of 659 randomly chosen fields in all of Manitoba’s major cropping zones were included in the province’s general weed survey, 151 of which were included in the herbicide resistance survey.

Beckie says there were a few surprises when it came to top

weed rankings in the general weed survey.

Green foxtail was still in the top weed from 2002, but wild oat, which had been second in 2002, was bumped to fourth place, replaced by wild buckwheat. Barnyard grass, fourth in 2002, took third place in the overall rankings.

Yellow foxtail was the biggest surprise. The weed, a cousin of green foxtail, had the greatest increase in ranked position, from 32nd place in 2002 to 6th place in 2016. “Part of it may be due to resistance because it’s escaping herbicide control,” Beckie says.

Overall, producers with herbicide resistant weeds rely more on herbicide application at all application windows, according to Beckie. But these producers also have greater adoption of scouting prior to herbicide application, tank mixing herbicides, and growing weed competitive crops.

science at the University of Manitoba, says there are other possible herbicide resistant weeds on the horizon for Manitoba. Glyphosate resistant kochia has been in Manitoba since 2013, and as of last year it was found in at least five municipalities.

In terms of herbicide resistance, this survey was the first to document resistance in yellow foxtail and barnyard grass.

Rob Gulden, a weed scientist in the department of plant

Glyphosate resistant waterhemp and glyphosate resistant Canada fleabane are not yet confirmed in the province but could come north via floodwater from North Dakota. “Not sure how

fast things will move, but there’s some evidence that suggests that these weeds have moved with overland flooding of smaller tributaries to the Red River,” he says.

Management

Most concerning of the Manitoba survey results is the incidence of multiple resistance in wild oat, says Beckie. Group 1 plus Group 2 herbicide resistance in wild oat has been found in 42 per cent of fields in Manitoba; in Saskatchewan this number is still only at 25 per cent.

“The incidence of multiple resistance is getting worse,” he says. “This presents the biggest challenge to producers in terms of management, especially in cereal crops.”

In the 2016 survey, Manitoba producers were also asked to rank their top 20 management practices in terms of which they feel are most effective in managing weeds.

Options include scouting multiple times per season, tank mixing herbicides, crop rotation, tillage and growing competitive

crops.

The practice that stands out the most, says Beckie, is tillage: Manitoba producers rely on tillage to manage herbicide resistant weeds, in sharp contrast to Saskatchewan producers, who don’t.

Overall, producers with herbicide resistant weeds rely more on herbicide application at all application windows, according to Beckie. But these producers also have greater adoption of scouting prior to herbicide application, tank mixing herbicides, and growing weed competitive crops.

The latter method is a key management strategy. “It’s the foundation of good agronomy and it goes a long way in preserving herbicide longevity,” Gulden says.

Producers should also focus on rotating herbicide groups, tank mixing herbicide active ingredients, and of course rotating crops.

“The other thing we’re learning with controlling wild oats is that we want to reduce seed production, and again, a good herbicide program and a competitive crop reduce weed seed production.”

Do you know how much water your pivot irrigation system is applying?

Growers can avoid costly mistakes by ensuring they have a thorough understanding of the irrigation process and system.

BY Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P. Ag.

Pivot irrigation is by far the most common method of irrigating crops in Western Canada. Over 80 per cent of the 1.7 million acres of Alberta’s irrigated land uses pivot systems. Low pressure pivots with drop tubes and spray nozzles have become the most common form of pivot irrigation due to water application and energy efficiency. In Alberta, low pressure pivots irrigate about 74 per cent and high-pressure pivots with impact nozzles irrigate about eight per cent of land.

A costly mistake irrigation farmers can make is not applying enough water to keep up with crop water requirements. Under-irrigating crops results in reduced yield potential. To accurately manage pivot irrigation, it is important to know to how much water your pivot is actually applying.

A common length of pivot is about 1,310 feet (ft) (400 metres), with an end volume gun covering another 50 ft, to irrigate about 133 acres of a 160-acre quarter section. These are commonly referred to as quarter section pivots. It is important to recognize that pivots are not 100 per cent efficient in applying water.

Gross irrigation water application is the amount of water put out by the irrigation system. The net irrigation water application is the amount of water that is actually stored in the soil after irrigation. If net water application is under estimated, it will cause under application of irrigation water, which could lead to reduced crop growth and yield.

Generally, a low-pressure pivot with drop tubes applies water at 80 to 85 per cent efficiency and a highpressure pivot with impact nozzles is about 75 per cent efficient, but these percentages can vary significantly. The level of water application efficiency varies with wind speed, air temperature and other factors like pivot operating speed.

When an irrigation system applies water, a portion of the water applied is lost through evaporation of spray water before reaching the soil, water evaporation from the soil surface and crop canopy, and also by surface runoff when the water application rate exceeds the infiltration rate of the soil. Efficiency is also

Table 1. Approximate gross water application in mm with a 133-acre pivot with an output ranging from 700 to 1200 U.S. gallons/minute and taking 24 to 96 hours to make a complete circle.

Hours to complete circle

SOURCE: R. H. McKenzie

affected depending on time of day when water is applied. Water application efficiency in hot windy weather at mid-day is much lower than application when air is calm and cool during night time conditions.

Table 1 shows the gross water application in millimetres (mm) for a 133-acre pivot with an output ranging from 700 to 1,200 U.S. gallons per minute (gal/min), when completing a full circle in 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours (one, two, three and four days).

Table 2 (page 26) shows the net water application in mm for a pivot with the same conditions, assuming a water application efficiency of 85 per cent. Note that using 85 per cent efficiency is a simplistic approach as evaporation losses vary with pivot speed and time of day of application.

When a pivot is initially purchased and set up, it is typically

nozzled for a specific water output. But, in some cases, the actual output may be less than expected if an under designed pump is used. Over time, as nozzles become worn, the water application rate can be affected. An accurate way to know the gross water application of a pivot is to have an in-line flow meter placed either at the pump site or at the pivot point.

Most farmers typically have quarter-section pivots that put out about 800 to 900 U.S. gal/min. If a 900 U.S. gal/min pivot makes a full circle in 24 hours, the gross water applied is 9.1 mm and the net application is 7.7 mm, assuming 85 per cent efficiency [from tables 1 and 2 (page 26)].

Most irrigated crops have an average peak water use in the range of seven to eight mm/day of water. But, peak water use for crops like corn and wheat can be up to 10 mm/day of water when daily

“If

Table 2. Approximate net water application in mm with a 133-acre pivot with an output ranging from 700 to 1,200 U.S. gallons/minute and taking 24 to 96 hours to make a complete circle, assuming an 85 per cent

SOURCE: R. H. McKenzie

Table 3. A 133-acre quarter section centre pivot with a gross water application of 900 U.S. gal/min with assumed water losses of four mm per application, results in reduced application efficiency when the pivot speed is increased and efficiency is increased when pivot speed is reduced to make a full circle.

SOURCE: Source: R. H. McKenzie

temperatures are over 30 C. This was common in southern Alberta in 2017. In mid-summer, when prolonged hot weather occurs, a 900 gal/min machine may not be able to keep up with daily crop water use. When reviewing the net water applied in table 2, the range of water applied ranged from 6.0 to 10.3 mm/day for pivots with outputs ranging from 700 to 1,200 gal/min.

Ideally, a pivot must be properly designed and nozzled to keep up with crop water requirements during peak times of water use. If a pivot system cannot keep up with peak crop water use requirements, crop growth and yield may suffer. For example, a 900 U.S. gal/min pivot making a circle in one day will apply about 7.7 mm of net water at 85 per cent efficiency. (Note: a pivot operating this fast often has a much lower water application efficiency). This application rate should be able to keep up with a crop use rate of seven mm/day. If the crop water use rate was 10 mm/day for one week, the crop would use 70 mm over seven days, but the net pivot output would be 54 mm over seven days. Over a period of several weeks of higher water use, the 900 U.S. gal/min pivot would gradually fall behind crop water use.

It is important to note that assuming that low pressure pivots are always 80 to 85 per cent is too simplistic. The operating speed can make a huge difference in efficiency. The percentage of water loss due to evaporation from the spray, and evaporation from the soil and crop canopy is increased, as the time to make a circle is increased. For example, in table 3, a 133acre quarter section centre pivot with a gross water application of 900 U.S. gal/min with an assumed water loss of four mm per application results in an application efficiency of 56 per cent when the pivot speed to make a full circle is one day. If the pivot speed is reduced to making a full circle in three days the efficiency is improved to 85 per cent. It is important to run pivots slow enough to reduce evaporation losses but quickly enough to minimize runoff losses.

To effectively manage pivot irrigation systems, it is critically important to develop a good understanding of the net water application for each pivot system on the farm, monitor your soil water content frequently, and do your best match water application with daily crop water use for best irrigation management.

An effective irrigation management strategy is to maintain soil moisture in the top 50 centimetres between field capacity and 60 per cent of field capacity. Let’s dig through the information growers should be aware of in order to develop the best strategy for their farms.

BY Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P. Ag.

The goal of irrigation scheduling is to ensure the crop is never under water-induced stress that would limit yield potential. It involves determining the correct amount of irrigation water to apply to a crop at the right times to achieve optimum yield.

Some of the important things you need to know include:

• The soil texture of fields to estimate the water holding capacity and amount of plant available water of each soil type in each field (see “Understanding water holding capacities” on page 18 in this issue)

• The allowable depletion of soil moisture that can be removed from each soil type before irrigation is required. Allowable depletion will vary with each crop

• Check soil moisture content of each field frequently throughout the season

• Know the daily water use of each crop at each growth stage

• Know the effective rooting depth of each crop

• Know the irrigation system gross and net water output to apply specific amounts of irrigation water (see “Making the most of your pivot irrigation” on page 24 in this issue).

To make irrigation management decisions, an irrigator must be able to measure soil moisture levels in each field, know the daily water use of each crop, and know the net water application of each irrigation system. With this knowledge, an irrigator can develop a practical scheduling plan for each field based on sound management information.

At the start of the growing season, an irrigation manager must ensure adequate water is available for seed germination for excellent emergence and early crop growth, by application of light, frequent water application.

This is possible with pivot irrigation systems, which apply rates as low as seven millimetres (mm) with a quarter section pivot in a 24-hour period. The advantage of pivot irrigation is the flexibility of applying irrigation water in varying amounts depending on water requirements. Water can be applied during early crop stages to promote vigorous growth and at the same time, apply additional water to increase available soil water reserves in the entire plant root zone to provide a reserve of water during peak crop water use later in the growing season.

The amount of water available to a crop depends on the water-holding capacity of a soil and the effective root zone depth for each crop. Allowable depletion (AD) is the amount of plant available water (PAW) that can be depleted or removed by a crop without experiencing water stress.

For most crops, allowable depletion is about 40 per cent of the available water. The AD will vary with soil type, crop type, stage of crop growth and effective rooting depth of the crop. Determining AD for the crop in each field is essential for effective on-farm irrigation scheduling program to meet crop water requirements.

The effective rooting depth of a crop is where most of plant roots are concentrated and extract water for plant uptake. For annual crops, rooting depth gradually increases during vegetative growth, and as plants shift from vegetative to reproductive growth, downward rooting ceases for most annual crops.

Hard-to-kill grassy weeds are no match for EVEREST ® 3.0. An advanced, easier-to-use formulation delivers superior Flush after flush™ control of wild oats and green foxtail. In addition, EVEREST 3.0 is now registered for use on yellow foxtail *, barnyard grass *, Japanese brome and key broadleaf weeds that can invade your wheat and rob your yields. You’ll still get best-in-class crop safety and unmatched application flexibility. Talk to your retailer or visit everest3-0.ca to learn more.

*Suppression alone; Control with tank-mix of INFERNO® WDG

For irrigation farmers, an effective irrigation management strategy is to build up soil moisture to near field capacity in the full 100 cm root zone in the spring and early summer, and maintain soil moisture in the top 50 cm between field capacity and 60 per cent of field capacity throughout the growing season.

Figure 1 (page 31) shows a generalized example for annual crop root development and depth of growth over a growing season. The effective rooting zone (ERZ) is the soil depth where plant roots take up their water.

Typically, roots are more concentrated in the upper half of the root zone. As a result, plants usually extract the majority of their water requirements from the upper half of the effective root zone, where there is a greater abundance of roots and water is easily accessed. Also, in the upper half of the root zone, soil temperature is warmer, soil organic matter levels are higher, soil biological activity is greater, plant available nutrient levels are higher and soil aeration is more favorable, all of which provide desirable conditions for more abundant plant root development.

Figure 1 also shows that about 40 per cent of crop water is taken up from the upper 25 per cent of the root zone and about 30 per cent of water comes from the second quarter of the root zone for a total of 70 per cent of a plant’s water requirements. In the third and fourth quarters of the root zone, only 20 and 10 per cent of water is taken up, respectively, for a total of 30 per cent of plant water requirements.

For most annual crops growing in soil with good moisture, about 70 per cent of crop water requirement is taken up from the upper half of the ERZ. For irrigation farmers, a very good irrigation management practice is to ensure good soil water

is maintained in the upper half to the ERZ throughout the growing season to prevent crop water stress.

For cereal and oilseed crops, the effective rooting depth is typically about 100 centimetres (cm) under favourable soil and environmental conditions, but take up about 70 per cent of their water requirements in the top 50 cm of the root zone. For irrigation farmers, an effective irrigation management strategy is to build up soil moisture to near field capacity in the full 100 cm root zone in the spring and early summer, and maintain soil moisture in the top 50 cm between field capacity and 60 per cent of field capacity throughout the growing season.

Crop water use is referred to as “evapotranspiration” (ET). ET is the combination of water evaporation from soil, and water used by plants for growth

2. Approximate daily water use for wheat (bottom) and canola (top), when soil moisture is adequate throughout the growing season. Daily water use can vary considerably due to crop cultivar, plant density and environmental conditions. (Source: R.H. McKenzie and S.A. Woods, 2011. Alberta Agriculture Adgex 100/561-1)

and transpiration. Transpiration refers to the water lost to the atmosphere through the stomata, which are small pores mostly on the underside of plant leaves, as the plants release water vapour to avoid heat stress.

The average amounts of water use are provided in figure 2 for wheat and canola (developed from research in southern Alberta). Crop water use will vary slightly in different regions due to varying crop,

soil and climatic condition differences. Water use can be quite variable depending on conditions such as temperature, humidity, solar radiation, day length, soil moisture level and wind. Daily water use can be over 10 mm per day for a number of crops when weather is very hot and windy.

Irrigation farmers in southern Alberta can access the Alberta Agriculture site: http://agriculture.alberta.ca/acis/imcin/ irricast.jsp and select the weather station nearest their farm to enter their crop information to find out the actual daily water use for each of their crops.

Pivot systems are designed to apply light, frequent amounts of irrigation water. Pivots are not designed to apply a large amount of water at one time. An important point for pivot irrigation farm managers is to know the gross and net water output of each pivot irrigation system on their farm. If net water application is over or under estimated, the results could return in over or under application of irrigation water which could lead to reduced crop growth and yield.

For pivot irrigation, scheduling decisions should be based on crop water use on a daily basis and keeping soil moisture between field capacity and safe depletion point. Water management of pivot irrigation is typically for the upper half of the root zone. This means application of light and frequent water application is required to match the water use of a crop.

The ability to rapidly and accurately measure soil moisture is critical for irrigation and dryland farmers. Knowing soil moisture level relative to field capacity and wilting point is necessary to determine the amount of water in soil. There are a number of different tools that can be used to measure soil moisture.

For most farmers, the simplest and easiest way is using the hand-feel method. This procedure uses a Dutch soil auger or soil probe to take soil samples from specific depths in the plant root zone and feel the soil to estimate the soil water content. Different soil textures have a unique feel with specific characteristics relative to the soil water content. With experience, a farmer can reasonably estimate a soil’s moisture content.

Spring side-banded P and strip tillage work.

by Bruce Barker

Corn is a heavy user of phosphorus (P) and is sensitive to zinc (Zn) deficiencies. In northern corn growing areas typical of the Canadian Prairies, early season cold soils may limit P availability, especially on soils with high residue cover. Additionally, corn following canola, which does not host arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), might also have early season P and Zn deficiencies.

University of Manitoba M.Sc. graduate, Magda Rogalsky, looked at how sideband P and Zn fertilizer and tillage would impact corn growth parameters, maturity and yield as part of her graduate studies. Research was conducted in 2015 and 2016 at two separate sites each year near Carman and Portage la Prairie, Manitoba.

A crop rotation study looked at the effect of growing corn on either canola stubble or soybean stubble to see if the non-AMF canola stubble would impact yield, and whether P and Zn starter

fertilizer could compensate. Four starter fertilizer treatments were compared to a non-fertilized P control and were sidebanded in the spring two inches beside and one inch below the seed.

Fertilizer treatments: all treatments side-banded in the spring (2” beside and 1” below seed).

No P control

27 lbs. P2O5 per acre (/ac) + 6.7 lbs. S (suphur)/acre

54 lbs. P2O5 /ac + 13.4 lbs. S/acre

27 lbs. P2O5 /ac + 6.7 lbs. S + 0.67 lbs. Zn/acre

54 lbs. P2O5 /ac + 13.4 lbs. S + 1.34 lbs. Zn/acre

ABOVE: In northern corn growing areas typical of the Canadian Praries, early season cold soils may limit P availability.

Soil test-P values ranged from very low [6 parts per million (ppm) Olsen-P] at Stephenfield in 2015, low at Carman (9 ppm) in 2016, and high (19 ppm) at Carman in 2015. Manitoba Agriculture fertilizer recommendations are 40 lbs/ac. P2O5 for low P-test levels, 30 lbs. P2O5 for medium, 15 lbs/ac. for high (15 ppm), and 10 lbs. P2O5 for high soil tests.

At two of three test sites, Zn levels were adequate; however, Stephenfield in 2015 had marginal levels.

Comparing AMF colonization at the V4 stage for corn, Rogalsky found no difference in the percentage of AMF colonizing roots between canola and soybean stubble treatments. However, growing corn after canola on the unfertilized control resulted in consistently lower early season biomass, lower plant tissue P concentrations and lower P and Zn uptake. She says this may indicate that the AMF activity levels were lower on canola stubble, earlier in the growing season.

The addition of starter fertilizer helped to compensate for lower P and Zn uptake on canola stubble, and was also beneficial on soybean stubble. Starter fertilizer on both canola and

soybean stubble increased early season growth, plant height, P concentration, and uptake of P and Zn in plant tissue, relative to the unfertilized control.

The early season plant growth response and greater nutrient uptake with starter fertilizer further accelerated silking by two to seven days and reduced grain moisture at harvest. At two out of three sites, the corn matured more quickly, with a greater maturity response to starter fertilizer with corn grown on canola stubble.

The combined effect of positive early and mid-season responses appear to have helped the crop realize more of its yield potential by the end of the growing season, and the grain yield increased by 12.2 bushels per acre [770 kilograms per hectare (kg/ha)] with the application of the high rate of MAP fertilizer.

Starter fertilization that included Zn did not result in a corn grain yield increase when compared to the unfertilized control. However, there was no yield difference between the MAP and MicroEssentials SZ (MESZn) starter fertilizer treatments. Lack of response to Zn in the trial was most likely due to the study sites being predominantly

located on soils that were not deficient in zinc.

“Contrary to our hypothesis, previous cropping of canola did not restrict arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonization of corn relative to that observed in corn after soybean,” Rogalsky says.

“The negative influence of a preceding canola crop on early season growth and mid season development of corn can be managed with starter fertilization, to provide adequate P to the corn crop and maintain successful production.”

Another part of the study compared starter fertilizer treatments under strip tillage and conventional tillage seeding systems. Under strip tillage, there is a concern that cooler early season temperatures may limit P uptake, which may lead to development of P deficiency symptoms at the early stages of development due to reduced root growth and P uptake. Conversely, Rogalsky says that high levels of soil disturbance with conventional tillage can also harm AMF quantity and colonization, which may reduce

early season P uptake. She looked at both tillage and starter fertilizer effects.

In 2015 and 2016, corn was seeded into cereal stubble (crop residue left on the field) at Carman and Portage La Prairie. In the previous fall, four fertilizer treatments and an unfertilized control were applied to both conventional and strip tillage treatments. Fall applications utilized a Yetter strip-till applicator to deep band (mono-ammonium phosphate; MAP) at four-to-five inches deep. Spring P applications of MAP were side-banded two inches beside and one inch below the seed.

Fertilizer treatments: Treatments deep-banded in the fall and side-banded in the spring.

No P control

27 lbs P2O5/ac Deep Band 4 - 5” deep MAP fall

54 lbs. P2O5 /ac Deep Band 4 - 5” deep MAP fall

27 lbs. P2O5 /ac Sideband 2” beside + 1” below MAP spring

54 lbs. P2O5 /ac Sideband 2” beside + 1” below MAP spring

Soil test levels showed P fertility was low at two sites and

medium at two sites.

Comparing the results of starter P, spring side-banded P often outperformed fall deep banding. Spring side-banded P treatments increased early season biomass, early season P concentrations in plant tissue and P uptake at V4, relative to the unfertilized control. Starter fertilizer also reduced days to silking and reduced grain moisture at harvest. Corn response to fall deep-banded P was not as consistent for early-, mid- and late-season measurements. Spring side-banded P increased grain yield by five per cent (7.3 bu/ac) over the fall deep band and no P fertilizer control for

both strip-till and conventional tillage.

“Averaged over all site-years, spring side banded P out-yielded the control and both fall deep banded P treatments,” Rogalsky says.

Comparing strip till against conventional tillage, there was no effect on early, mid- and late-season measurements. Corn planted in strip tillage yielded the same as corn planted in conventional tillage, and had similar maturity.

Rogalsky explains that strip till could provide economic savings with lower fuel and labour costs over conventional tillage where a fall and spring tillage is typically conducted prior to seeding corn.

“Strip till in combination with starter fertilizer, appears to be a viable conservation tillage alternative to conventional tillage in Manitoba, where cold and wet soils at planting are a risk to timely planting and vigorous early season growth,” he concludes.

Aggressive pigweed species has been devastating to U.S. growers.

by Bruce Barker

Grows more than two inches per day. Produces over one million seeds per plant. Grows 10 feet tall. Resistant to at least four different herbicide groups in the U.S. No wonder 200 American weed scientists in 2017 ranked Palmer amaranth the most troublesome weed in broadleaf crops, fruits and vegetables. While Palmer amaranth has not yet crossed the 49 th parallel, given the rapid spread in the U.S., it is likely just a matter of time.

“I do think that it is possible that Palmer amaranth will appear in Ontario agricultural fields, but, I will never predict when – it could be next year or decades in the future,” says Peter Sikkema, professor of weed management at the University of Guelph Ridgetown campus.

Palmer amaranth was first identified in southeastern U.S. cotton fields in 2005. Today, Palmer amaranth is found in nearly every part of the U.S. except for the northwest and extreme northeast. The states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota and Wyoming have so far avoided the creeping invasion.

“I am convinced southern Ontario will soon have glyphosateresistant Palmer amaranth,” says Jason Norsworthy, professor and endowed chair of weed science at the University of Arkansas.

In North Dakota, weed scientists have been proactive in providing farmers with information on Palmer amaranth, naming it weed of the year in both 2014 and 2015.

“I think the genetic diversity of Palmer amaranth will allow it to ‘survive’ in North Dakota and Canada. Our climate may not favour the two-to-three inches growth per day as in the south but it can survive,” says Richard Zollinger, extension specialist and professor of weed control at North Dakota State University.

Palmer amaranth is thought to have spread in the U.S. in multiple ways. It was introduced into Michigan with cotton seed used in dairy rations that contained Palmer amaranth seed. The weed

was subsequently spread with manure. Other mechanisms may include custom combines carrying seed, movement of contaminated seed, hay or forage, transport by ducks and other waterfowl, as well as water flow.

Water flow may pose the greatest risk for Manitoba farmers in the Red River Valley. Palmer amaranth seed is light and floats on water. Flooding of the Red River may eventually move the weed up through North Dakota and into Manitoba.

Several traits make Palmer amaranth a real threat for farmers. Yield loss has been measured at 78 per cent in soybean and 91 per cent in corn in the U.S.

Sikkema says in Canada, yield loss will depend on several factors including relative time of crop and Palmer amaranth emergence, Palmer amaranth density, adaptation to Canadian environmental conditions, and environmental conditions in each growing season.

“Using glyphosate-resistant waterhemp as an example [a related amaranthus species], the yield losses due Palmer amaranth interference will vary from less than 10 per cent to greater than 75 per cent in both corn and soybean,” Sikkema says.

Fast growth and prolific seed production are important, but because the weed has both male and female plants, it reproduces by cross-pollination. This means the weed has wide genetic diversity and may help contribute to its adaptation to new areas.

Additionally, that wide genetic diversity means herbicide-resistant populations can be quickly selected with frequent herbicide use. In the U.S., Palmer amaranth quickly developed glypho -

ABOVE: A couple identifying features of Palmer amaranth.

Cotyledons Small, narrow and pointed Small, narrow and pointed Rounded at tip and differential size

Leaves Narrow and shiny with short petioles

Source: NDSU

sate resistance, primarily because of tight rotations of Roundup Ready crops. Now, Palmer amaranth has developed stacked resistance to ALS resistance (Group 2), DNA resistance (Group 3), glyphosate resistance (Group 9) and PPO resistance (Group 14). Some farmers are now resorting to hand-weeding.

“I challenge anyone to come up with an effective herbicide program that I could place in that field and successfully grow a Roundup Ready or conventional soybean crop – because it’s not possible,” Norsworthy says.

The prolific seed production also makes the weed a threat, and patch management is key if a population is introduced into a field. In February of 2008, Norsworthy established 20,000 glyphosateresistant Palmer amaranth seeds in a one square metre circle to represent the surviving seed of a single Palmer amaranth female plant. That fall, Palmer amaranth was located as far as 400 feet downslope, believed to have moved downhill with rainwater. In 2009, it infested 12-to-31 per cent of the total field area. In 2010,

Ovate/round and dull green with short petioles

Ovate/round with long petioles with spike at the tip.

infestations reached greater than 95 per cent of the total field area and the crop was abandoned due to the high weed competition.

For Canadian farmers who do not yet have Palmer amaranth, scouting will be key in helping to slow the spread if the weed does move North. However, weed identification is difficult at the seedling stage, since it is similar to waterhemp and redroot pigweed.

North Dakota State University has a dedicated webpage on Palmer amaranth, with photos and links to other State University sites.

If identified, weed scientists agree that zero tolerance should be the goal, with patch management using tillage, herbicides, and hand weeding as key to helping stop the weed from gaining a foothold in a field. Pesticides alone won’t be sufficient, especially if Roundup Ready crops are grown in tight rotations.

“Diversity, diversity, diversity in your long-term integrated crop and weed management programs will be essential,” Sikkema says.

Manage fertilizer inputs to optimize crop production and ensure soil quality is maintained.

by Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P. Ag

Fertilizer is a costly input needed to optimize crop production. Understanding how fertilizer reacts in soil is important to optimize use and efficiency to grow high yielding crops. It is also important for farmers to understand the short and long-term effects fertilizers can have on soil chemical and biological properties.

The salt content of a fertilizer is a critical factor in placement of fertilizer in the seed row. “Salt effect” or “fertilizer burn” occurs when fertilizer is located with or near a germinating seed resulting in injury or death of the seedling. Injury is caused when the concentration of salts in the fertilizer is greater than the concentration of salts within the plant cells, resulting in higher osmotic pressure in the soil versus the seedling. This causes water to move out of the seedling cells and into the soil. Often the salt effect results in the eventual death of the plant

tissue and seedling. When water moves out of plant cells, the tissue desiccates, the seedling dies and roots become blackened. The term “fertilizer burn” comes from the visual appearance of blackened seed and roots. Fertilizer types vary in their salt level or salt index (SI). Products with a lower SI value are less likely to cause salt injury. Products such as ammonium sulphate (21-00-24) or potassium chloride (0-0-60) have higher SI levels (20.9 and 11.5, respectively), versus mono-ammonium phosphate (1152-0) of 5.95.

“Toxicity effect” occurs when urea (NH2)2CO granules are near a germinating seed and convert to ammonia (NH3). When soil moisture conditions are good, hydrogen (H+) ions from water will attach to ammonia to convert to ammonium (NH4+) to eliminate the toxicity effect. But when soil moisture conditions