TOP CROP MANAGER

KOCHIA CONTROL IN SUNFLOWER

Kochia, biennial wormwood can impact yield PG. 52

WILD OAT CONTROL

Diverse rotations are necessary PG 8

FENCEROW FARMING

Yield benefits justify the effort PG. 12

Kochia, biennial wormwood can impact yield PG. 52

Diverse rotations are necessary PG 8

Yield benefits justify the effort PG. 12

20 | Mapping variability

An on-farm study looks at soil sensor data for identifying variable rate management zones. By

Carolyn King

58 | Herbicide registrations, label updates Expanded herbicide choices in 2016.

Ken Sapsford

| Pulse rotations providing ongoing N benefits

Improving the accuracy of estimating nitrogen credits and benefits from pulses.

Donna Fleury

Fencerow farming

Economic case for winter wheat

Rolling soybeans

Be an AgSafe family

for

Readers

numerous

Janet Kanters | eDItOr

Be an AgSafe Family is a new three-year campaign launched by the Canadian Agricultural Safety Association (CASA) and the Canadian Federation of Agriculture (CFA). This year, the campaign will focus on “keeping kids safe,” a very timely goal in light of the fact children continue to suffer accidents on family farms.

Be an AgSafe Family is part of this year’s Canadian Agricultural Safety Week, which runs from March 13 to 19. Organizers say focusing on kids during this year’s Ag Safety Week is a no-brainer. According to the most recent agricultural fatal injury surveillance program (Canadian Agricultural Injury Reporting) from CASA, an average of 13 children die every year as a result of agricultural incidents in Canada. And while they say the number of child deaths on farms appears to be decreasing slightly, that number is still too high.

CAIR, which tracks agricultural-related deaths, said there were 2,317 fatalities related to agriculture between 1992 and 2012. Of those, 272 were children under the age of 15: 123 infants and toddlers between the ages of one and four, 86 between the ages of five and nine, and 63 children between the ages of 10 and 14 years old. Another 102 people between 15 and 19 were killed in agricultural incidents during the same stretch.

Meanwhile, the rate of agriculture deaths for kids under 15 across the country fell by an average of 0.8 per cent annually between 1990 and 2015. CAIR does not consider this statistically significant. However, agricultural activities are becoming safer for those over 15. The fatality rate for people working in agriculture between the ages of 15 and 59 dropped by an average of 1.1 per cent per year, CAIR said, determining this statistically significant.

Almost half of all agricultural fatalities in Canada (46 per cent) were due to three machine-related causes: machine rollovers, machine runovers and machine entanglements (total of 1,062 fatalities). Machine rollovers and machine runovers accounted for 20 per cent and 18 per cent of deaths respectively, with machine entanglements accounting for eight per cent.

The death rate for runovers is high in children in particular. Sixty-one per cent of child deaths (66 deaths, between ages of one and four) between 1990 and 2012 involved runovers in which the child was a bystander. Another 39 per cent (26 deaths) involved the child as a passenger.

Most child deaths on the farm are male, and most are the children of the farm owner or operator. Runovers aren’t the only hazard: many die by drowning, by machine rollover, by animal-related incidents, and/or being caught in or under an object, or being struck by a non-machine object.

Close to half of child deaths on farms occur close to the farm house, for instance, in the farm yard, driveway, barn or sheds. Basically, where children live and play. With farm equipment in and around the farm house and barns/sheds, it makes a child’s “playground” dangerous.

But that doesn’t have to be the case. All farm parents know the inherent dangers on the farm, and certainly make their children aware of these potential dangers. But we were all kids once – which means we sometimes “forgot” what mom or dad said, or we were so caught up in our play or task that we lost our focus on our surroundings, even if only for a moment. And it only takes a moment for an accident to occur.

Farm parents are certainly doing all they can to ensure their farm is safe for themselves, their children and anyone visiting or working on the farm. Canadian Agriculture Safety Week is just another reminder to continue to be vigilant when working on the farm, to ensure it remains a safe and happy place for everyone.

MEDIA DESIGnER Gerry Wiebe CIRCulATIon MAnAGER Carol nixon • 450-458-0461 cnixon@annexweb.com vP PRoDuCTIon/GRouP PuBlISHER Diane Kleer • 519-403-8816 dkleer@annexweb.com DIRECToR oF Soul/Coo Sue Fredericks

PuBlICATIon MAIl AGREEMEnT #40065710 Printed in Canada ISSn 1717-452X

CIRCulATIon email: rhtava@annexbizmedia.com Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3555 Fax: 416-510-5170

Mail: 80 valleybrook Drive, Toronto, on M3B 2S9

SuBSCRIPTIon RATES

Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues February, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, october, november and December – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East – 7 issues February, March, April, September, october, november and

Long-term research studies are few and far between in Canada, but their value to Canadian agriculture is incalculable.

by Julienne Isaacs

According to Don Flaten, a professor in the department of soil science at the University of Manitoba (U of M), when new research data from one of U of M’s long-term studies is published, word quickly spreads to his colleagues around the world. “Before long, they’re calling to say, ‘Don, why didn’t you tell us about this data sooner?’” he says.

Data from long-term research studies becomes exponentially valuable over time, but such studies are becoming rarer – particularly when they operate at the systems level, analyzing a variety of qualities in the agricultural system, and their interactions, over time.

“Studies like these are always under pressure because they consume resources,” says Martin Entz, a professor in the U of M’s plant sciences department, and head of Glenlea Research Station’s 24-year long-term organic and conventional cropping study. “When times get tough, they’re on the chopping block.”

Flaten says universities are especially challenged to maintain long-term trials. He leads the National Centre for Livestock and the Environment’s (NCLE’s) long-term manure and crop management field laboratory at Glenlea. “Our study has no permanent technical support,” he says. “It relies on year-to-year funding from granting agencies. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) support for long-term studies is vital.”

The project also relies on local industry partnerships with the Manitoba Pork Council and the Dairy Farmers of Manitoba, and a variety of national and provincial grants.

Glenlea is home to several long-term systems-level research studies, including Entz’ study, which began in 1992, and is Canada’s oldest evaluation of organic cropping systems. But Entz says

TOP: Glenlea Research Station at the University of Manitoba is home to several long-term systems-level research studies.

INSET: Flaten calls long-term systems-level studies “goldmines” of data for agricultural research.

there are even older studies across Canada, such as AAFC’s longterm crop rotation study based at Indian Head Research Farm, which has been running since 1958. Lethbridge is also home to a very simple rotation study (not systems-based) that has been running since 1911.

“These studies are national treasures, producing amazing results that we’d never expect,” Entz says.

According to Christine Rawluk, NCLE’s research development coordinator, long-term systems-level research studies are important because systems are incredibly complex and change over time. “If you make a decision based on a short-term study, you don’t know if the change you’re implementing has true benefits or negative consequences in the long-term,” she says. “Time is a really important part of the system itself.”

Systems are vulnerable to a wide range of factors, such as weather and soil variability, and management practices.

NCLE’s manure and crop management study analyzes the effects of different types of manure fertilizer on soil nutrients over time. “One year or even three years doesn’t give you the whole picture, particularly with nitrogen, because the yields don’t start showing an effect from solid manures before five years or more,” Rawluk says. “So if we were to look at it for just one growing season, we wouldn’t have an accurate sense of how organic reserves of soil nitrogen are becoming available over repeated years.”

Flaten says farmers take a long-term approach to farming by applying specific management practices over extended periods, so it only makes sense to analyze practices in the long-term at the research level. These studies can account for the impact of shortterm practices in the long term. “And sometimes there are results you don’t understand, which challenges us to realize there’s more to systems than we know,” he says.

Entz says his long-term study has paid off in spades. “One of

the things we’ve discovered is that the more ecological farming systems that use fewer external inputs over time, with small adjustments to management, have become very productive and economically and biologically efficient. We’d never have discovered that if we’d only done that for five years,” he says.

The Glenlea studies have a highly practical element. Researchers actively encourage involvement from industry groups and producers so they can influence the studies from the ground up.

NCLE’s studies aim to encourage partnerships between crop and livestock producers. “We’re looking for opportunities to capitalize on the integration of livestock and cropland,” Rawluk says. “Whether it’s a mixed operation or a situation where your neighbour has annual crops where you’re applying your manure, we’re looking for opportunities for collaboration at the farm level.”

There’s another key benefit to Glenlea’s long-term systemslevel research studies: they actively encourage interdisciplinary conversations and cross-departmental collaboration, which counteracts a culture of specialization that has actually been counterproductive to agricultural research.

Long-term systems-level studies are designed to be sustainable, which means seeking input from experts across the university. “When considering parameters for the Glenlea study, we consulted with economists, soil scientists, entomologists,” Entz says.

“Specialization has become the norm, and agriculture is no different – we have specialists in particular areas of soil fertility, and in plant diseases,” he notes. “You’d be surprised how difficult it is for those specialists to talk to each other. But the farm system is not specialized – what happens in one part affects the other parts. That specialization has precipitated very specialized research. Everyone is solving a problem their own way. But at some point you have to put it all together.”

Flaten calls long-term systems-level studies “goldmines” of data for agricultural research. Entz agrees. “The systems-level approach to long-term studies is valuable because life works at the systems level,” he says.

We rethought every inch of the new Case IH 2000 series Early Riser ® planter with your productivity in mind. We applied Agronomic Design™ principles to make it simpler, faster, more durable and more productive. And we provided you with a bundle of industry firsts — from our rugged new row units that create the only flat-bottom seed trench to our state-of-the-art in-cab closing system — that give you even more control. The result is unmatched accuracy and emergence for a better plant stand and, ultimately, yield. Start rethinking productivity today at caseih.com/newearlyriser

by Donna Fleury

For growers in Western Canada, wild oat continues to be one of the most problematic weeds. Growers spend more money on wild oat herbicides than any other weed species and, together with increasing wild oat resistance to herbicides, implementing integrated weed management techniques to slow herbicide resistance is needed.

Today, researchers are helping growers find options to reduce herbicide inputs, environmental impact and selection pressure for weed resistance.

“Given the intense herbicide pressure, many wild oat populations are now resistant to several different herbicide modes of action in Western Canada,” explains Neil Harker, weed scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lacombe, Alta. “The most recent weed surveys show that over half of the cultivated fields in Alberta have Group 1 resistant wild oat. The level of resistance is increasing rapidly, with Group 1 resistant wild oat found in about 11 per cent of cultivated fields in 2001, rising to 30 per cent in 2007 and to over 50 per cent in 2015.

“There are also Group 2 resistant wild oat populations, Group

1 and Group 2 and at least one case of wild oat resistance to four modes of action,” Harker adds. “Implementing integrated crop management strategies now is key to slowing down herbicide resistance and extending the use of herbicide tools.”

Harker led a five-year no-till study initiated in 2010 at eight sites across Canada (Lacombe, Lethbridge, and Edmonton, Alta.; Scott and Saskatoon, Sask.; Winnipeg, Man.; New Liskeard, Ont.; and Normandin, Que.) to look at options for combining cultural weed management practices with minimal herbicide use to manage wild oat. Wild oat management was compared in diverse rotations that included winter cereals, chemical-fallow and alfalfa with more common summer annual crop rotations (canola, wheat, barley, peas). In addition, diverse rotation treatments were combined with other cultural practices that reduce wild oat populations, such as early-cut silage and higher than normal crop seeding rates, practices that were previously used before the current reliance on herbicide control.

ABOVE: Cut wild oat in barley silage at Lacombe, Alta.

Reach for Wolf Trax Copper DDP ®, the nutrient tool that is field-proven by wheat growers like you.

With our patented EvenCoat™ Technology, Copper DDP coats onto your N-P-K fertilizer blend, delivering blanket-like distribution across the field for easier root access. Plus our innovative PlantActiv™ Formulation ensures the copper is available when your wheat crop needs it most.

See how the right tool can boost your wheat crop and your bottom line. Have your dealer customize your fertilizer blend with Wolf Trax Copper DDP.

Copyright © 2016, All Rights Reserved - Compass Minerals Manitoba Inc. Wolf Trax and Design, DDP, EvenCoat and PlantActiv are trademarks of Compass Minerals Manitoba Inc.

Compass Minerals is the proud supplier of Wolf Trax Innovative Nutrients. Not all products are registered in all areas. Contact wolftrax@compassminerals.com for more information.

Product depicted is Wolf Trax Iron DDP coated onto urea fertilizer. Other DDP Nutrients may not appear exactly as shown.

46833-5 TCMW

Fig. 1. 2014 wild oat biomass (across site means of 4 sites) responses to crop life cycle, crop species, crop seeding rate, crop usage and herbicide rate combination effects.

C 50H Alf 0H Alf 0H Alf 0H C 100H

C 50H ChemF 2xFR 0H ChemF C 100H

C 50H 2xES 0H P 100H 2xWT 0H C 100H

C 50H 2xFR 0H P 100H 2xWT 0H C 100H

C 50H 2xES 0H 2xWT 0H 2xES 0H C 100H

C 50H 2xES 0H 2xWW 0H 2xES 0H C 100H

C 50H 2xES 0H 2xWW 0H 2xWT 0H C 100H

C 50H 2xES 0H 2xES 0H 2xW 0H C 100H

C 50H 2xES 0H 2xES 0H 2xWW 0H C 100H

C 50H 2xB 50H P 100H 2xW 50H C 100H

C 50H 2xB 0H P 100H 2xW 0H C 100H

C 50H 2xB 50H C 100H 2xB 50H C 100H

C 50H 2xB 0H C 100H 2xB 0H C 100H

C 100H W 100H C 100H W 100H C 100H 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

“2x” indicates doubled crop seeding rate. C = canola, Alf = alfalfa, ChemF = chemical fallow, FR = fall rye, ES = early-cut barley silage, P = field pea, WT = winter triticale, WW = winter wheat, W = wheat, and B = barley. Canola in 2010 and 2012 was glufosinateresistant. Canola in 2014 was glyphosate-resistant. Numbers preceding H (herbicide) indicate the % of recommended wild oat herbicide applied in a given year. Blue bars indicate values significantly greater than the 100% wild oat herbicide, canola-wheatcanola-wheat-canola treatment (red box). Treatments circled with an orange box are those without wild oat herbicides from 2011 to 2013 that are statistically similar to the bottom treatment (red box).

Source: Neil Harker, AAFC, 2015.

In year one, wild oat populations were established in canola at all locations. From 2011 to 2013, the trials included 14 treatments at each site; each treatment integrated different factors (crop species, crop life cycles, crop seeding dates and rates, harvesting dates and herbicide rates) over three growing seasons to influence wild oat demography. At the end of the 2013 growing season, the cumulative effects of these treatments were determined. Canola was seeded across all sites in 2014, with yield, seed oil and protein concentrations measured. The most popular crop rotation sequence on the Canadian Prairies, canolawheat in a full herbicide rate regime, was considered as the standard treatment to compare 2013 and 2014 data to all other treatments. Wild oat seed bank data were analyzed in the fall of 2014. These results were used to help researchers determine if some treatments in the project could provide wild oat management in the absence of intense selection pressure for herbicide resistance.

The study results showed that some diverse rotations in integrated systems without wild oat herbicides can be just as effective at managing wild oat as typical

summer annual canola-wheat rotations in full herbicide-rate regimes. Diverse rotations including early-cut barley silage with higher seeding rates of winter cereals and excluding wild oat herbicides for three years often led to similar wild oat plant density, aboveground wild oat biomass, wild oat seed density in the soil, and canola yield as a repeated canola-wheat rotation under a full wild oat herbicide rate regime.

Results were similar with perennial alfalfa without wild oat herbicides for three years, where wild oat populations were reduced to almost nothing. However, forgoing wild oat herbicides in only two of five years from exclusively summer annual crop rotations resulted in higher wild oat density, biomass and seed banks. Researchers concluded management systems that effectively combine diverse and optimal cultural practices against weeds and limit herbicide use can reduce selection pressure for weed resistance to herbicides and extend the lifespan of effective herbicide tools.

“The take-home from the results of our study is that diverse rotations are necessary for integrated weed management and will help growers reduce the selection pressure

for herbicide resistance,” Harker says. “We also showed in the weed seed bank study that several diverse rotations without wild oat herbicide treatments three years in a row were just as good as the canola-wheat and full herbicide rotations. Although concerns have been raised that after three years of no wild oat herbicide treatments the weed seed bank would increase, our results did not show that. Therefore, integrated crop and weed management systems work, but growers need to implement them well and implement them soon.”

Diverse rotations and integrated crop and weed management continue to be important strategies not only for wild oat control and reducing selection pressure for herbicide resistance but also for other weed and disease problems. For example, Group 1-resistant green foxtail is widespread, as are many Group 2-resistant broadleaf weeds, including cleavers and kochia. Glyphosate resistant kochia has also recently been identified in Western Canada, the first glyphosate resistant weed to be found there. Disease issues such as blackleg and clubroot are also increasing, particularly in shorter canola rotation systems.

“The results from this project and others, such as work we did in comparing canola rotations and the impacts on diseases like blackleg and pests such as root maggots, show that longer and more diverse rotations were associated with greater canola yields and decreased blackleg disease and root maggot damage,” Harker adds. “Although in the short term the shorter canola-wheat rotations may seem to be more profitable, over the long term diverse rotations and integrated crop management are necessary to reduce herbicide expenditures, reduce selection pressure for weed resistance and to grow canola in more sustainable rotations.”

If growers continue to rely on shorter rotations, the costs of controlling increasing disease problems and herbicide resistant weeds are expected to increase substantially, reducing overall profitability and increasing the risk of losing herbicide tools. With increasing resistance issues in Western Canada and elsewhere, such as in Australia where one biotype of rigid ryegrass resists seven modes of action, it is time for growers to act proactively to keep herbicide control and costs manageable over the long term and reduce selection pressure and herbicide resistance.

In addition to providing an exceptional yield increase, Prosaro® fungicide protects the high quality of your cereals and helps ensure a better grade.

With two powerful actives, Prosaro provides long-lasting preventative and curative activity, resulting in superior protection against fusarium head blight, effective DON reduction and unmatched leaf disease control.

With Prosaro you’ll never have to settle for second best again.

Fencerow farming makes intuitive sense, but do resulting yield benefits justify the intense effort?

by Madeleine Baerg

Morrin, Alberta farmer and certified crop advisor

Steve Larocque’s journey into extreme precision agriculture was made possible by a dose of chance, an eye for potential, and a willingness to step into the unknown, followed by a whole lot of brainbendingly intense mental energy. The results, preliminary yields suggest, may change the way top farmers use controlled traffic farming (CTF).

“We chanced on what I call fencerow farming almost by accident, which I guess is the way most really cool, innovative things are discovered,” Larocque says. “Now that we’re seven years in, I really believe it is the future of controlled traffic farming for top farmers, at least for those who are as anal or type A as me.”

Back when Larocque first jumped into CTF, his initial challenge was to figure out how to adjust his equipment to manage residue while staying on CTF tramlines. While most people seed right between previous rows, Larocque found that ground hard and dry, especially in low moisture years. Instead, he offset his hitch by just two inches, allowing his shanks to seed right

alongside the previous year’s stubble where the soil is comparatively softer and moister. While this seed placement is unusual, Larocque’s wouldn’t be much of a story if his efforts had ended there. But, about the same time, he started thinking more and more about something that at first glance seems entirely unrelated: old fence lines.

Over decades, fence lines catch drifting soil, building up a four, five, even 10 foot wide raised area that boasts a substantially deeper A horizon (top soil strata) compared to the rest of the field. Long after the fence line is removed, the built up area offers a better growing medium with richer, more deeply placed nutrients and a greater amount of beneficial biological activity.

Like many farmers, Larocque noticed time and again that his yield monitor spiked as his combine heaved up and over the headlands of long-gone fence lines. There had to be a way, he figured, of mimicking that fence line effect along every row of his

TOP: Wheat beside canola stubble.

INSET: Fababean plant showing the root biomass Larocque is trying to achieve in his fencerow farming system.

A NEW WORLD DEMANDS NEW HOLLAND.

field to achieve a yield jump in each and every plant. Not one to watch and wait for others to innovate, Larocque converted his farm into a large-scale “fencerow farming” experiment.

Since he was already placing seeds close to old stubble to capture maximum moisture, Larocque began seeding in a four year placement rotation (ie: row A in year 1, two inches left of row A in year 2, two inches right of row A in year 3, back on top of row A in year 4). This seed placement resulted in a six inch wide “fencerow” every 12 inches throughout the field.

Intensive soil testing suggests Larocque’s fencerow seeding method is generating a host of benefits. The consistent location of the stubble row builds up and concentrates organic matter like mini fencerows. In dry years, the highest soil moisture content is found inside the previous year’s root ball and can spell the difference between weak and strong emergence. Equally importantly, Larocque says, fencerow farming allows him to improve the availability of nutrients through row loading.

“If you seed across your stubble or even between rows, you dilute your mobile nutrients. You’ll accumulate them over time but never in high concentration. What we are trying to do is create a biological zone that is super loaded with as much nutrient as possible – macros, micros, biologicals, even fungicides and pesticides – anything that can support the plant in furrow,” Larocque says. “We keep all of the nutrients within the same furrows, maximizing availability to the crop, decreasing nutrient immobilization, and super loading the biosphere to support tons of biological activity.”

“We’ve been using fertilizer in the same way for 40 years. We’re seeing yield improvements because we have better varieties than we used to, but we’re not seeing yield improvements from how we actually use fertilizer. There are ways of using the same inputs we’ve always used but using them with much more efficiency,” he adds.

With six seasons of fencerow farming under his belt, Larocque says it is still too early to prove with yield data the single most important question about fencerow farming: whether it actually produces sufficient financial benefit to justify the required RTK technology’s $35,000 price tag, and the admittedly intense mental effort.

“We believe that it absolutely will prove itself, but we haven’t put in enough years yet. And we still have some fine-tuning to

do to tighten up our furrows so we only cover 25 per cent of our land with furrows, not 50 per cent as we do now. All indications show that we’re on the right track. But it takes at least six years to change things substantially enough in the soil’s structure, biological health and nutrient availability to be really noticeable, and we’re only on year seven,” he says.

While Larocque’s preliminary results look good, the results of long-time fencerow farmer Dean Glenney offer even more promise. Glenney has been quietly growing corn in southern Ontario according to fencerow farming principles for more than 20 years. Larocque hopes to soon achieve comparable results to his fencerow farming predecessor.

“Glenney is pulling 300 bu/ac corn while everyone else around is pulling 170 bu/ac corn on the same rainfall. That gets a guy like me excited,” Larocque says. “It may take a decade to see the results but once we’re there, we hope to achieve what Dean Glenney has in Ontario with the same technique.”

Larocque is convinced today’s generally accepted concept of controlled traffic farming just barely scratches the surface of precision agriculture’s benefits. While he admits his precision-to-a-whole-new-level farming technique might sound extreme, he firmly believes the results from his farm will pave the way for top farmers.

“There’s no question: what I call fencerow farming is the future for the top 10 or maybe 20 per cent of Alberta farmers,” Larocque says.

In fact, the greatest deterrent to greater

uptake is not the technology itself but rather the culture and expectations surrounding Canadian farming, he says.

“Until the pain of staying the same is more than the pain of change, people will continue to do the same thing over and over, and watch from the sidelines. Why would you change when things are working OK – not working amazingly, but working OK?” Larocque says. “You see much greater adoption of innovation in places like Australia or South America because they don’t have back stops like crop insurance there. Guys have to be really sharp or they get knocked out of the business.”

Fencerow farming does take an added level of management, admits Larocque. For him, though, the mental exercise required to create, analyze, fine tune and problem solve a workable fencerow farming system into existence in his fields makes farming “a lot more fun.”

To farmers who might be nervous about jumping into this intense form of farming, he says: “Half the battle is just getting your head wrapped around it. You absolutely can do it, and you can do it on larger scale. You don’t flip the switch and start fencerow farming, you just baby-step into it. Once you put in the up-front time to get started, controlled traffic farming makes your life easier because you know exactly where to go. And if you can get bigger returns for the same amount of crop inputs? That’s what we need to prove to get people on board.”

for more on new crop management, visit topcropmanager.com.

I still get up early the way my grandfather used to. As a farmer I’ve always had to find new and smarter ways of getting the job done, to work the land regardless of the weather or the economy.

Today, I’ve got access to precision tools and in-field expertise that allow me to grow my crops with much greater confidence. Data and soil testing and satellite imagery can tell me exactly where I should apply crop protection and nutrition products so I maximize yield. At the end of the day, it’s my job to adapt and try new things – to be a smart grower.

ESN® SMART NITROGEN® is an important tool on my farm – it’s a controlled-release nitrogen. Its unique technology means that it adapts to growing conditions and releases nitrogen when my plant needs it. I’m not held hostage waiting for the perfect weather because ESN does the work for me. Plants get the nitrogen they need, when they need it most, boosting my yields and minimizing N loss to the environment. Bigger yields and improved nitrogen use efficiency makes sense for my bottom line and for the air, water and soil we rely on to make a living.

The tools we use in farming will always evolve, but the purpose behind our work hasn’t changed in a hundred years. I respect the land and work hard to grow quality food the same as my grandfather and my dad. I’m proud to make a living off the land.

Populations now in all three Prairie provinces.

by Donna Fleury

Glyphosate-resistant kochia is spreading across Western Canada, and researchers warn that growers should be diligent when planning crop and herbicide rotations to manage for glyphosate resistance.

One of the most widely used herbicides in the world, glyphosate is a key herbicide for weed control in Western Canada. It is used for growing glyphosate-resistant canola, corn, soybean and sugar beet, for weed control in chemical fallow, and for preseeding, pre- and post-harvest weed control in no-till cropping systems. Frequent glyphosate use has selected for glyphosateresistant (GR) weeds, which currently total 32 weed species in several countries, including Canada.

Kochia (Kochia scoparia) became the first GR weed confirmed in Western Canada in 2011 in Alberta. To determine if and where the weed is spreading, researchers from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) conducted post-harvest field surveys in 2013 across 342 sites (one population per site) in southern and central regions of Saskatchewan and 283 sites in Manitoba to determine the distribution and abundance of GR kochia. Populations were also sampled in field border areas and

other areas such as roadsides and ditches, railway rights-of-way and oil well sites. Mature plants were collected, viable seeds threshed and seedlings tested for resistance. The seedlings were screened for resistance by spraying with a discriminating glyphosate dose of 900 g ae/ha (2X label rate) under greenhouse conditions.

“The results from the screening trials confirmed 17 GR kochia populations in nine municipalities in west-central or central Saskatchewan, but only two GR populations from different municipalities in the Red River Valley of Manitoba,” says Hugh Beckie, weed scientist with AAFC in Saskatoon. “In Saskatchewan, taken together with previously confirmed populations, GR kochia is now present in a total of 14 municipalities.

“The Saskatchewan survey results showed the majority of GR kochia populations originated in chemical-fallow fields [10 of 17], although some populations were found in cropped fields [wheat, lentil, GR canola] and non-cropped areas [oil well site, roadside ditch],” he adds. “However, in Manitoba, the two

ABOVE: GR kochia in southern Alberta in 2011.

populations occurred in fields cropped to GR corn and soybean. During these surveys, it was common to see other kochia populations suspected to be GR in fields adjacent to the survey-targeted field, suggesting seed spread via tumbleweed movement or by farm equipment.”

The frequency of glyphosate resistance in confirmed populations varied from 12 to 96 per cent. Differences may be due to the time since glyphosate resistance was selected or introduced (either via seed or pollen), the amount of glyphosate selection that occurred in that population over time, or recent treatments that removed susceptible individuals from the population.

“We also confirmed the first GR kochia in lentil and GR canola in one municipality near Moose Jaw, which is spatially isolated from the cluster of municipalities in west-central Saskatchewan,” Beckie notes. “This field was cropped to lentil with glyphosate applied preseeding and preharvest, which is a

common practice in the areas. However, we can’t rule out that the GR kochia may have migrated from adjacent land.”

The impact of this GR weed biotype on both economics and agronomics is compounded because of consistent multiple resistance to Group 2 (ALS inhibitor) herbicides. Beckie says most Prairie kochia populations are ALS inhibitor resistant.

“Our finding of the first GR kochia in lentil is concerning, as currently there are no in-crop herbicides available to control GR plus ALS inhibitor-resistant kochia in lentil. There are also no in-crop herbicide options to control this multiple-resistant biotype in canola, other than growing a glufosinate-resistant canola cultivar.” Similar to the Saskatchewan GR kochia populations, both Manitoba populations were ALS inhibitor-resistant.

Researchers also assessed the effectiveness of alternative herbicides on populations of this multiple-resistant biotype in greenhouse studies. The study confirmed that all GR kochia

in Saskatchewan was susceptible to dicamba, an increasingly important auxinic herbicide used for control of this multipleresistant biotype. Dicamba-resistant kochia has not been identified previously in Western Canada, but has been reported in the Midwestern U.S. Worldwide, the incidence of multipleresistant weed biotypes is increasing at an alarming rate.

Although kochia was the first of several species predicted to be at risk for glyphosate resistance in Western Canada, other abundant species selected during preseeding or in-crop/ fallow applications are also at risk, including wild oat, green foxtail, cleavers and wild buckwheat. Like kochia, these weeds have already been selected for resistance to herbicides with different sites of action used in-crop. Beckie estimates the cost of herbicide-resistant weeds at $1.1 billion to $1.5 billion per year on the Prairies. The cost is from a combination of related factors, including added herbicide cost due to increased tank-

mixing required, added overall weed management (cost of tillage or crop rotation, for example) and lost yield due to increased weed competition.

“We expect GR kochia to rapidly spread across the Prairies, similar to ALS inhibitor-resistant populations, and are watching with concern the increasing incidence of multiple-resistant weed biotypes,” Beckie says. “In the future, more diverse crop rotations and better cover crops where fallow is practiced would lessen selection pressure for GR and multiple-resistant populations. Across the Prairies, multiple-resistant weeds will continue to challenge growers, especially when one of those sites of action is glyphosate.”

for more on weed management, visit topcropmanager.com.

• Ultimate broadleaf weed control performance in wheat and barley

• Extreme productivity and convenience in the conditions you’ve got

An

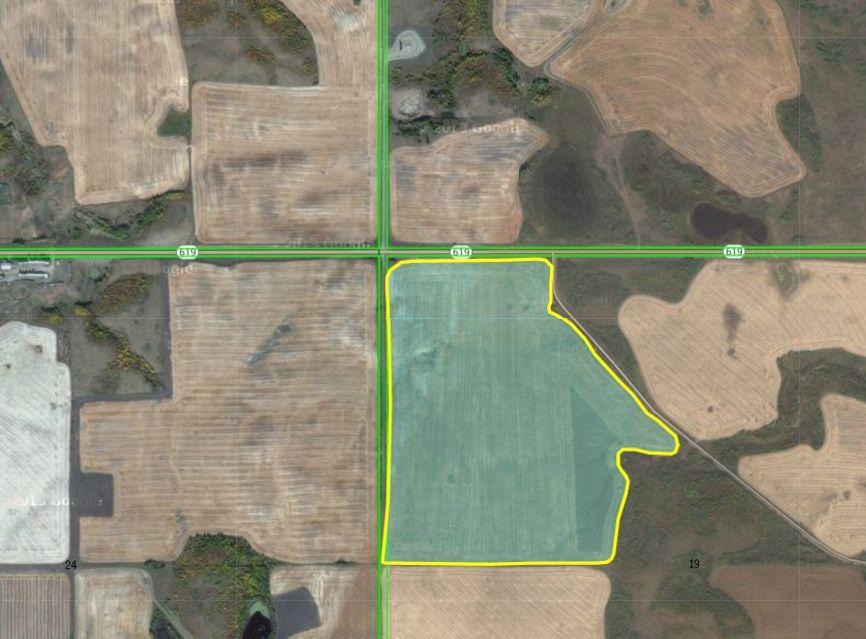

by Carolyn King

Variable rate nitrogen applications have the potential to save money and improve crop yields. But what is the best way to come up with variable rate management zones that provide economic benefits to the farmer? Could soil sensor maps be a practical data source for identifying meaningful management zones? Those are some of the questions Alberta researchers are answering through a major on-farm precision agriculture study.

The idea for this study was sparked a few years ago when Ken Coles, general manager of Farming Smarter, saw some electrical conductivity (EC) sensors at a precision agriculture conference. He was intrigued by the possibility of using these sensors as an alternative to grid soil sampling for mapping in-field soil variability. “The idea is that we can’t do grid soil sampling to the level of accuracy needed to manage variable rate inputs effectively, plus soil sampling is expensive. So if we can run a soil sensor over a field and get the same or better information, then maybe there is value in it,” he says.

Lewis Baarda, GIS analyst with Farming Smarter, compares the two approaches. He explains that a grid soil sampling system with one sample every five acres would provide 32 data points for a quarter section, and the lab analysis for nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and sulphur would cost about $1,600. An EC sensor

service could produce an EC map of a quarter section with about 50,000 data points for a cost of about $880. EC data tend to be good at predicting soil texture and soil moisture content.

But Coles wanted to do more than compare EC sensor maps and grid soil sampling maps for creating management zones; he wanted to evaluate if those zones were actually meaningful and useful for variable rate management. He says, “Creating management zones based on soil information and then creating a prescription map is not that hard. The challenging part is verifying whether your variable rate management is actually paying for itself. That is really what I wanted to do with this study.”

Coles also wanted to do the study as on-farm research, which added another level of variability. He notes, “Just finding the right co-operators to work with is challenging, and even when we have the right people, we still have human error issues or lack of priority issues. So, not only are we going into a complex environment where we have no control over the variables, but we are literally studying variability and we also have human and equipment and scale variability.”

Starting in 2012, he teamed up with Baarda and Muhammad

ABOVE: The researchers hooked together the Veris MSP3 and EM38-MK2, pulling the two soil sensors across each field at the same time to compare the data.

TIGER XP™ sets a new industry standard for performance. With a unique composition of sulphur bentonite and a proprietary activator, TIGER XP provides higher sulphate availability that addresses early season sulphate deficiencies and provides crops more sulphate throughout the growing season. With added dust suppressant coating for improved safety and handling, TIGER XP is optimized to outperform traditional sulphur products. Learn more at Tigersul.com

(Adil) Akbar, precision agriculture specialist and research director with Farming Smarter, to conduct the study on 10 farm fields. The fields are located in southern Alberta, the Drumheller area and the Peace Region (in co-operation with the Smoky Applied Research and Demonstration Association).

Because of the study’s complex objectives, quite a few steps were required in the data collection and analyses for each field, including: conducting soil sensor mapping and grid soil sampling; determining how strongly the EC maps matched up with the soil sample data, yield maps and other data sources; delineating field zones based on these different data sources; conducting a nitrogen fertilizer rate/yield response trial; determining which zone map best predicted yield variability across the field; and determining which zone map provided the best basis for variable rate nitrogen applications.

With funding from Alberta’s Agricultural Initiatives Program, Farming Smarter was able to purchase two EC sensors: the EM38-MK2 and the Veris MSP3. The researchers hooked together the two sensors and pulled them across each field, using Farming Smarter’s onboard RTX-DGPS sensor for georeferencing and elevation recording.

“The EM38 has been around for a long time; they used to use it to map salinity and it’s quite effective for that,” Coles says. The EM38 does not require direct contact with the soil to take EC readings. It is pulled over the field’s surface and takes measurements every few seconds. It can measure EC at depths of 0.75 and 1.5 metres at the same time.

The

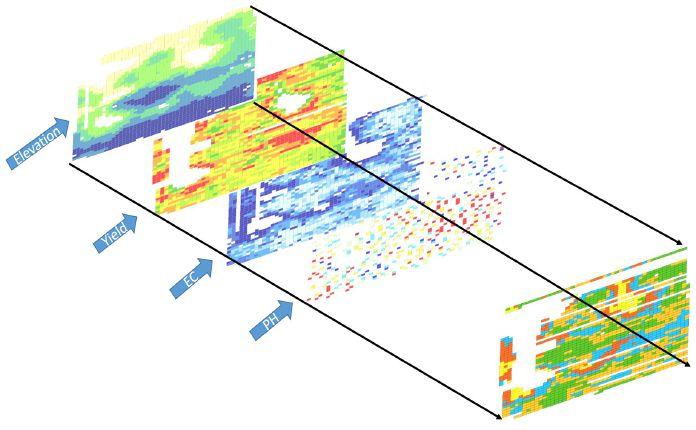

study compared several data layers, including electrical conductivity (EC) data from soil sensors, for understanding in-field variability.

The Veris organic matter sensor measures the soil’s optical reflectance, basically how dark or light the soil is, and those reflectance data are converted to organic matter content by Veris. The pH sensor directly measures soil pH using an on-the-go chemical test, taking a soil sample, testing it and then taking the next sample, while the Veris moves across the field. The pH and organic matter sensors provide fewer data points per field than the 50,000 points generated by the EC sensors.

Soil sampling followed a five-acre grid, with 32 samples for each 160-acre field. The samples were analyzed for nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, sulphur, organic matter, pH, EC, moisture content and texture.

The co-operators provided yield data collected by their on-combine yield monitors. Baarda notes, “Although the standard practice is to use at least three

The research team scanned each field twice with the two EC sensors, usually in the spring and the fall

The Veris MSP3 is a mobile sensor platform with three sensors: EC, pH and organic matter. Its EC sensor requires soil contact so it has coulters that maintain soil contact as the equipment is pulled across the field. Like the EM38, this sensor measures EC at both 0.75 and 1.5 metres deep.

The research team scanned each field twice with the two EC sensors, usually in the spring and the fall.

to five years of yield maps to define productivity zones, in most cases it was a challenge to gather even three years with good spatial coverage.”

Coles adds, “Finding good yield map data is really difficult. There are many reasons for that. One reason is that people don’t save the data; they don’t take the time to transfer it to their computer. Another reason may be that they have two or

three combines on the field at the same time, which makes it challenging to stitch the data together. Or it could be they didn’t calibrate it properly.”

For each field, the researchers created zone maps using five different data sources: EC sensor data; historical yield data from the co-operator; grid soil sample data; a visual depiction of the field’s main terrain features; and a composite of yield and EC sensor data. This composite method was included because an objective procedure called principal component analysis identified EC and yield as the two variables, among all the data collected, that best accounted for spatial variability in the 10 fields.

At each field, they conducted a replicated, randomized nitrogen fertilizer rate/ yield response trial. The nitrogen fertilizer was applied at seeding. The specific nitrogen rates used in each trial depended in part on what the cooperating farmer wanted to do; usually fewer than five rates were used. The researchers measured the variations in grain yield response and determined the nitrogen rate/yield response curves.

Next, they laid each zone map over the yield response results and determined which of the five zone delineation methods worked best for predicting in-field yield variations and for predicting zones for variable rate nitrogen applications.

As you can probably imagine, the study involved huge amounts of data that required

You need something more than seed genetics alone to protect your canola from blackleg.

With tightened canola rotations and sole reliance on R-rated genetics for control, blackleg is on the rise across Western Canada. Your best defence is an integrated approach that includes Priaxor ® fungicide. Tank mixed with your in-crop herbicide, Priaxor uses the unique mobility of Xemium® and the proven benefits1 of AgCelence ®. Together they deliver more consistent and continuous control of blackleg and larger, healthier plants for increased yield potential2. For more information, visit agsolutions.ca/priaxor or call AgSolutions ® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273).

1AgCelence benefits refer to products that contain the active ingredient pyraclostrobin. 2All comparisons are to untreated unless otherwise stated. Always read and follow label directions.

AgSolutions is a registered trade-mark of BASF Corporation; AgCelence, PRIAXOR, and XEMIUM are registered trade-marks of BASF SE; all used with permission by BASF Canada Inc. PRIAXOR fungicide should be used in a preventative disease control program. © 2016 BASF Canada Inc.

complex analysis. Akbar, Baarda and Coles are currently finalizing the study’s report, and they hope to also publish some scientific papers.

In terms of the performance of the EC sensors, Baarda says, “Our EC data from the Veris and the EM38 were highly consistent with each other. Also, the spring EC map was always highly consistent with the fall EC map. We could almost take one EC layer and say that’s what the EC map is [for the field] because those patterns don’t change over time and they don’t change between the sensors.” The researchers also found that the EM38 was easier and less costly to use than the Veris for mapping EC.

Overall, the EC sensor data tended to be strongly correlated with the soil sample data for sand and clay content and soil moisture content, although the strength of the correlations varied from field to field. So, EC sensor maps can give farmers a better understanding of the soil variability in their fields.

However, the EC sensor maps didn’t necessarily predict the spatial patterns in some of the other soil sample data, like nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), sulphur (S), pH and organic matter. According to Baarda, scale issues could be a factor in the weakness of some of these correlations.

“We’re comparing about 30 data points from soil sampling to about 50,000 from the EC sensors. The [weaker] relationships can get obscured because of the different scales of the datasets. So, even though we don’t see a relationship to N, P, K and S, we can’t necessarily say that those macronutrients don’t correlate to EC. But we get a sense that they probably don’t correlate as strongly as we’d need to make a management response to them.” So the EC sensor maps are not a reliable way to directly estimate variable nutrient rates.

The study also showed grain yield could not be predicted directly from just the EC sensor maps. The correlations with yield were weak or did not exist. Various factors might have contributed to these poor correlations, including the challenges in obtaining good yield data.

Another key finding was the surprising amount of year-to-year variation in the yield patterns. “I think people have a sense that yield patterns are more static than they actually are. Some parts of those spatial patterns are consistent, but

statistically those patterns change more than I would have thought,” Baarda says. “So it’s important to have at least three to five years of yield data; the more years you have, the more it helps to balance out the outlier years.”

The strength of the correlations among the various other data layers – such as elevation, yield, soil nutrients, soil texture, the pH sensor and the organic matter sensor – also varied from field to field.

Because of the field-to-field differences, the different zone delineation techniques

had different levels of success depending on the field.

For predicting yield potential, the composite method – pairing up yield and EC sensor data – was the best of the five methods for delineating zones. “In 100 per cent of the instances, the composite method was the most successful in differentiating within-field zones of different yield potentials. So the zones created by pairing EC and yield were meaningful: they predicted where we would have high and low productivity

based on the information we had before the growing season,” Baarda explains. “The other four delineation methods failed in differentiating any productivity zones in 20 to 30 per cent of the instances and had varying combinations of complete and/or partial success in the remaining instances.”

He adds, “Some of the composite method’s success is likely due to the use of multiple variables – hedging our bets so to speak. Some of its success also likely lies in the fact that we objectively identified yield and EC as key variables for zone delineation.”

None of the delineation methods were very successful in identifying zones that could be managed differently for nitrogen in ways that would benefit the farmers economically.

According to Coles, the next step in this research would be to add more layers of data to the analysis, such as remote sensing data from satellites and data from other in-field sensors.

“Our big message is there is no single data

layer that can be guaranteed to tell you what you need to know to variably manage inputs,” Baarda says. He emphasizes that zone management is a process – each field is unique and you have to be prepared to invest some time in understanding the field’s variability and figuring out what works best for that particular field.

If you’re interested in experimenting with variable rate applications, Coles recommends starting with just a few layers of data.

Baarda thinks an EC sensor map could be a good option for one of those layers. “Not only is EC mapping cheaper than grid soil sampling, but it has a longer ‘shelf life.’ In our experience, EC doesn’t tend to change over time, so a field could be mapped for EC once, and in most circumstances, that data would be relevant for a number of years.” Although the sensors don’t provide the data on nutrient levels that you can get from soil sample analysis, the sensor maps do indicate variations in other soil properties, especially soil texture.

In farming, the only thing that’s predictable is how unpredictable things can get; but when you use Raxil® PRO Shield seed treatment with Stress Shield®, you can expect superior disease and wireworm protection, as well as improved yield performance.

With three different fungicidal actives, you also receive full contact and systemic protection from the most dangerous seed- and soil-borne diseases, including Fusarium graminearum.

With Raxil PRO Shield, what you seed is what you get.

If you want to use your yield monitor data in identifying management zones, then try to ensure the reliability of that data. For instance, be sure to download the yield data from your combine and save it so you can accumulate as many years of data as possible. If you’re using two separate combines on the same field, then consider calibrating them in the same way. If you’re calculating the average yield pattern for a field based on several years of data, exclude any years where the data are skewed because of some external factor, like hail damage on half of the field.

And no matter what data layers you use and what zone delineation method you test, Coles suggests that your on-farm study design should include the steps needed to allow an objective evaluation of whether or not your approach is actually helping you economically.

Coles concludes, “There are lots of people doing variable rate agriculture but very few who are effectively testing and verifying the success.” He adds, “More academic work in this area is sorely needed.”

The study was funded by the Alberta Canola Producers Commission, Alberta Barley and Farming Smarter.

Increased early season growth and yield observed in trials.

by Bruce Barker

What does it take to grow a 200-bushel per acre oat crop? That’s what research manager Chris Holzapfel at the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation wondered when he saw that kind of yield in both commercial fields and small plots near Indian Head, Sask., in 2013.

“Oats are frequently considered relatively unresponsive to fertilizer applications and excellent scavengers of residual soil nutrients,” Holzapfel says. “But when yields are high, oats do require abundant nutrients, regardless of how they respond to fertilizer applications.”

Indeed, oats have a high nutrient requirement. A 100-bushel crop takes up 108 lbs of nitrogen (N), 44 lbs P2O5, 113 lbs K2O, and 18 lbs of sulphur (S). Nutrients removed from the field in the harvested seed are 77 lbs N, 28 lbs P2O5, 19 lbs K2O, and seven lbs of S.

In 2014 at Indian Head, Holzapfel looked at oat response to N, P and potassium (K) fertilizer with funding from the Agricultural Demonstration of Practices and Technologies (ADOPT) program.

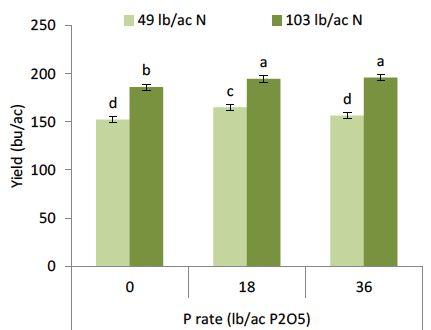

The treatments compared were 12 different combinations of applied rates of N, P and K fertilizer. The N rates were 49 and 103 lbs N per acre, the P rates were 0, 18, and 36 lbs P2O5 per acre, and the K rates were 0 and 27 lbs K2O per acre. Soil residual N and P at this location were low, while K was high.

Holzapfel says increasing N rates from 49 to 103 lbs N resulted in a 20 per cent yield increase but also resulted in significant reductions in both test weight and thousand kernel weights. He says P fertilization reduced the impact on quality to a certain extent and resulted in an average overall yield increase of four per cent, but no short-term agronomic benefits were detected when rates were increased from 18 to 36 lbs P2O5. (See Table 1, page 28.)

“We saw a massive early season response to phosphorus. There was a very noticeable improvement in vegetative growth, but at the higher rate, it didn’t translate into a yield benefit,” Holzapfel says.

ABOVE: Manage phosphorus in oats for long term fertility.

Go ahead. Paint a target on persistent wild oats and get rid of them for good with Axial herbicide. It targets the toughest grass weeds in your fields, especially wild oats, and eliminates them before they become a problem. When you’re on a mission to help your spring wheat and barley reach its full potential, choose Axial herbicide.

There were no statistically or agronomically significant benefits to K fertilization detected with respect to either lodging, yield or grain quality under these specific field conditions

Holzapfel had hoped to carry the research forward into 2015, but did not have funding to do so. However, other research at Indian Head, this by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) researcher Bill May, found similar results in a three-year study in 2003 through 2005. Phosphorus response was analyzed as part of a larger study on P and seeding rate to increase the competitiveness of tame oat on wild oat. Holzapfel was also part of the study.

“We didn’t see an interaction of phosphorus and seeding rate on wild oat. Seeding rate was more important than the addition of phosphorus on controlling wild oats in a crop of tame oat,” May says. “We did see a small yield response to phosphate fertilizer.” (See Table 2.)

These studies on P and K were consistent with another study conducted by Ramona Mohr with AAFC at Brandon, Man. Her three-year study was conducted from 2000 through 2003 and looked at varying rates of N, P and K fertilizer. Nitrogen was applied at 0, 35, 71, and 106 lbs N per acre. Phosphate rates were 0, 26 and 53 lbs P2O5 per acre. Potassium rates were 0 and 35 lbs. K2O per acre.

Mohr published the results in the Canadian Journal of Soil Science in 2007. She reported that “low to moderate N rates significantly increased yield, with optimum relative yield achieved with a plant-available N supply of approximately 90 lbs N per acre. Increasing N rate also increased lodging and reduced test weight, kernel weight and kernel plumpness, suggesting that optimal N management must balance yield improvement against reductions in grain quality.” Based on this and other studies, Manitoba provincial guidelines recommend a plant-available N supply (soil test nitrate-N in 0-24 in. plus fertilizer N) of 100 lb/ac for oat.

Source:

Phosphate fertilizer increased yield in two of six site-years, but had no overall effect on quality. Yield increases were observed at locations with dry, cool early-season conditions combined with low to moderate soil test P.

Application of potassium chloride fertilizer (KC1) resulted in small increases in yield (78 lbs/ac), kernel weight and kernel plumpness on moderate to high K soils, which were “not likely to provide a significant economic benefit.”

“The lack of consistent interactions among N, P and KCl suggests these nutrients may be managed individually,” Mohr says.

May says the P response in the studies is typical of most cereals. He quite often sees a vegetative response to P on the heavy clay soils typical of his area when conditions are dry and cool, which can translate into a yield response as well.

“I wouldn’t expect oat to be any different to other cereal crops. You can see early season vegetative response in some years, but not necessarily a yield response,” May says.

Holzapfel says the research has shown that oat response to phosphorus fertilizer application can be inconsistent, but maintaining P levels is important from a long-term soil quality perspective. The crop in his demonstration presumably removed over 44 lbs P2O5 per acre in the highest yielding treatments.

“When you are removing that level of phosphorus from the soil, you need to be replacing it or you will be drawing down the soil residual phosphorus reserves. You are fertilizing the soil as much as you are trying to feed the crop,” Holzapfel says.

by Donna Fleury

Field surveys across Western Canada are showing an increase in the presence of cleavers. Generally, the vast majority of populations have been identified in Saskatchewan; however in the 2010 weed survey in Alberta, cleavers ranked as the number three weed in canola and number one weed in pulses. Cleavers are difficult to control in many crops and can cause downgrading and reduced crop quality.

With funding from the Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission, Western Grains Research Foundation, Government of Saskatchewan Ag Development Fund, and multiple industry partners, researchers at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) have just concluded a two-year study to help growers in managing cleavers in canola. They characterized the emergence and genetic characteristics of cleavers populations in Western Canada, which were believed to be two species: Galium aparine and G. spurium Researchers also assessed the response of cleavers to potential new herbicides (in canola) such as quinclorac and clomazone, as well as their response to common canola herbicides such as glufosinate-ammonium and glyphosate to determine whether differences among populations existed.

In 2012 and 2013, field experiments were conducted at different locations in Saskatchewan, including Scott, Saskatoon and Rosthern (2014 only). Eight herbicide treatments were used in this experiment, including the herbicide standard for each canola system used alone and with the addition of quinclorac (tank-mix) and/or clomazone (preseed). At all sites, canola varieties (L130, 73-75 and 45H73), resistant to their respective herbicide system, were seeded into cereal stubble. Greenhouse dose-response experiments were also conducted to assess whether variability existed between populations in their response to herbicides.

“One of the most important findings from our research for management of cleavers in canola is that a portion of cleavers are emerging in both spring and fall, and that emergence timing of each of these fall and spring cohorts varied between years,” explains Christian Willenborg, assistant professor, department of plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan. “Historically, cleavers were considered an obligate winter annual and generally emerged in the fall. However, our research confirms what growers and agronomists have been seeing: cleavers have largely responded to our cropping systems and, along with a shifting climate, are now emerging in both fall and spring. These differences suggest growers will need to pay close attention to emergence timing of this weed to ensure the small window for control is not missed.”

Another important outcome was that researchers successfully developed a molecular marker that could differentiate and characterize the cleavers species in the field. It has long been believed cleavers populations in fields across Western Canada are a mixture of both species. However, molecular analyses showed all sampled populations were in fact identified as G. spurium, or false cleavers. Although no G. aparine was found in the collected samples, it does not mean there is none present in fields across the Prairies. Willenborg adds that for growers, knowing populations are primarily one species, G. spurium, which is also the species that possesses resistance to Group 2 herbicides, is important because resistance will spread more quickly if all plants within the population are the same species.

One of the key recommendations resulting from the study is that growers will have to have a well-planned strategy for managing cleavers at different times in the rotation. “We found that in canola, spring emerging cleavers seem to emerge right after the crop is planted, and are often too large for some in-crop herbicide products, particularly those with a narrower application window such as the two-whorl or two- to four-whorl stage,” Willenborg says. “In some cases, such as the last couple of years, growers were unable to make a fall application because of either inclement weather or the timing of harvest. This can cause problems the

following spring, as cleavers plants may be very large at this point and therefore difficult to control with pre-emergence herbicide applications. As well, some in-crop application timings have not been ideal because of the higher than usual moisture conditions.”

On the positive side, the results of the field study conducted over two years and at three sites showed that clomazone and quinclorac significantly reduced cleavers biomass and seed contamination and improved cleavers control in canola crops. The results consistently showed that applying clomazone prior to seeding (pre-plant) canola followed by an in-crop application of a herbicide standard provided acceptable control, usually greater than 85 to 90 per cent. The results also showed the tankmix of quinclorac with a herbicide standard applied in-crop brought control to at least 85 or 90 per cent, without a preseed clomozone application.

In fields where cleavers populations are a big problem, all three products could be used: preseed clomozone, and the incrop tankmix of quinclorac and herbicide standard. “In the study, using all three products provided the best results, often with an additional five per cent increase over the other combinations,” Willenborg explains. “However, growers have to assess whether or not the use of all three herbicides will pay for itself.” The results of the greenhouse dose-response experiments appeared to suggest cleavers populations responded similarly to glufosinateammonium, imazapyr+imazamox, and quinclorac, despite being from different locations in Western Canada. However, further testing and statistical analysis is needed to confirm this.

Both herbicides, although new to Western Canada for

SJ3-VR and SJ7-VR StreamJet tips feature a unique variable orifice design to boost your productivity in the field. It’s like having 5 tip sizes in one.

• Support a wide range of rates including variable-rate, prescription map application with a single tip

Simple design has no moving parts for long-term accurate and reliable operation

Solid stream pattern directs fertilizer to the root zone and minimizes leaf coverage to prevent crop damage and yield loss

cleavers control, are older technologies. Clomozone, which is not yet registered in Western Canada as of December 2015, is a Group 13 product that has been registered in Eastern Canada under the product name Command for several years. Quinclorac, a Group 4 product, is now registered, but growers are cautioned they cannot use quinclorac in canola until the industry addresses MRL (maximum residue limits) considerations in some markets. Registration and acceptance of these herbicides will significantly improve cleavers control in Western Canada.

To manage cleavers in canola, growers should start controlling cleavers in the year before growing canola in rotation, such as in cereals where good control options are available. There are some existing Group 4 products, along with two new products registered in 2015, Pixxaro and Paradigm. The active ingredient in these products, halauxifen-methyl branded as Arylex, also has activity on kochia and can be tank-mixed with a range of other products for control of broadleaf and grassy weeds.

“The most important recommendation is in addition to in-crop herbicide control strategies, the addition of a fall application is key to managing cleavers over the long-term,” Willenborg says. “Growers need to plan to control cleavers that emerge in the fall prior to growing canola. Glyphosate can be used for

control, but growers need to recognize the higher risk of developing herbicide resistance in cleavers, and therefore tankmixes and well-planned herbicide rotations are key. Avoiding tillage is also recommended as tillage can create situations that encourage germination and recruitment of cleavers seedlings.”

Although the addition of these new herbicide options will provide good options for canola growers when available, over the long term they are not a silver bullet. These herbicides, like all herbicide tools, will need to be carefully managed to reduce the risk of herbicide resistance. Cleavers resistance to Group 2 herbicides has already developed across Alberta and Saskatchewan, and cleavers rank second among weeds likely to develop glyphosate resistance in the Black soil zone.

“Our study showed that spring applied clomazone reduced the size and stage of cleavers found in-crop, and it is known that lower population numbers reduce the risk of developing herbicide resistance,” Willenborg adds. “Both clomazone and quinclorac, which can be tank-mixed with any of the in-crop herbicides, also provide alternative modes of action for control and by tank-mixing with herbicide standards, should delay the evolution of resistance to glyphosate and glufosinate.

“However, in the mid 1990s, some cleavers populations in Alberta were identified as resistant to quinclorac,

which is Group 4, as well as some Group 2 products, so there are some multiple resistant populations that already exist in Western Canada. Although these resistant populations haven’t spread very much, the scale that quinclorac could be used in canola in the future could mean an increased selection pressure for this herbicide and this could result in the spread of these populations.”

Willenborg is building on this work with some new projects to address some other questions that impact management related to emergence timing and base temperatures. “A better understanding of both emergence timing of spring and fall cleavers, along with corresponding base temperatures, will help us to develop better models to more accurately predict emergence timing for growers,” he says.

“Another area we are looking at is as more growers move to straight cutting and the use of desiccants and harvest aids in harvesting canola, we need to have a better understanding of fall emergence timing of cleavers. Growers need to know what effect a pre-harvest application of desiccants or harvest aids might have on cleavers control and for reducing seed production. Moreover, a significant proportion of cleavers populations emerge in the fall and, therefore, management in the fall is key to the sustainable longterm management of cleavers in Western Canada.”

A cleaner, better way to handle the sprayer rinse is looking promising for Western Canada.

by John Dietz

Thank the Swedes for this idea: “biobeds” that promise to protect water quality for generations to come.

The concept represents a low cost, environmentally friendly way to deal with the rinse water flushed out of agricultural field sprayers.

According to Larry Braul, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada water quality engineer in Regina, the biobed is an organic filter for pesticides, using conventional low value material. The use of biobeds has become an accepted practice in Europe in the past 15 years.

Braul and Claudia Sheedy, research scientist with AAFC at Lethbridge, Alta., are co-leading the project to develop a biobed model to support Canadian farmers. Starting with one biobed at Outlook, Sask. in 2014, AAFC expanded the project in 2015 to sites at Simpson, Sask., and Grande Prairie and Vegreville, Alta. An additional biobed was constructed in fall of 2015 and will be monitored in 2016 at Lethbridge. “At the end of 2016, we expect to

have enough data to produce a construction, operation and maintenance manual for biobeds,” Braul notes.

Initial results promising

“The first year at Outlook, it was highly effective. It removed more than 98 per cent and up to 100 per cent of the pesticides it received. That was very positive, and the results we just got back for 2015 are very similar,” Braul says.

“Our climate is much colder than Europe and we have more intense rainfall events. We are working to address those issues with designs revised for the Prairies,” he adds.

In principle, a biobed is relatively inexpensive, easy to use and significantly accelerates the natural breakdown processes for

TOP: Researchers used polyethylene tanks meant for fish, at Simpson, Sask. Note the grass growth on top and the drip line. INSET: The biobeds at Outlook, Sask., with a passive solar collector in the background.

Nu-Trax P+™ with CropStart™ Technology puts you in charge of delivering the nutrition crops need for a strong start. And a strong start can lead to a better harvest.

It features an ideal blend of phosphorus, zinc and other nutrients essential for early season growth. With patented EvenCoat ™ Technology, Nu-Trax P+ is coated onto your dry fertilizer blends. And with blanket-like distribution across the field, it’s placed close to young plant roots where they can access the nutrients earlier, especially in cold and wet soils.

This spring, take control of your crop’s early season nutrition. Ask your retailer for Nu-Trax P+.

Rethink your phos

pesticides. The most challenging aspect at this point is in finding or developing an inexpensive method to easily collect the sprayer rinse water. On most farms when rinsing, the sprayer arms are fully extended while water is pumped through the system. As a result, a catch basin for that spray would need to be up to 120 feet long by about 20 feet wide and would need to drain the spray to a point where it can be collected.

The contained biobed for the rinse water uses a mixture of topsoil, compost and straw. It provides an ideal habitat for microbes to break down the pesticides carried in the rinse water, to the point they pose no threat to the environment.

In the project’s first year, Braul and Sheedy discovered the biobed at Outlook was still frozen a few inches below the surface in May, when they hoped to use it. It needed to be warmed to about 10 C, so that microbes could process the rinse water.

They resolved that issue for 2015. Braul says, “Microorganisms like warm conditions. In a new biobed, we put heat tape at the bottom. We can get them up to almost 30 C at the end of May, so they can really start breaking down the pesticides. With a little heat application at the right time, we are probably doubling the decomposition rate they’re getting in Europe.”

European research found that half and up to 90 per cent of pesticide contamination in groundwater could be traced to the places where sprayers were rinsed, Braul

says. Two factors go into that: there’s a concentration of pesticides in one place, and a lot of water washing it down. It’s too much for the microorganisms to process.

Often the topsoil is stripped off and replaced with gravel at the site where the farm sprayer is rinsed. This removes the organic matter that absorbs pesticides and allows the pesticide to leach through the soil zone. Often, it’s fairly close to the well that supplies the water.

“That’s the worst situation for managing the site,” Braul says. “It becomes quite a significant source of contamination. Instead, if we capture that rinsate, contain it and treat it, we can make a significant impact on the contamination problem.”

The Swedes were first to address the problem. They collected rinsate and applied it to the top of a simple hole in the ground filled with the biomix material. “The Swedes applied the rinsate to the top of the biomix and let it seep through into the ground. It was the standard for six or seven years. It was a heck of a lot better than putting it on gravel, because it absorbed a lot of the pesticide. Now, with more sensitive instruments, we know that model doesn’t remove all the pesticides,” Braul says.

Current practice is to build a contained biobed up to a metre deep. In the UK, that would be lined at the bottom with clay or plastic, and drained with weeping tile.

For their first project, Braul and Sheedy built a wood frame structure. On later projects they also used open polyethylene tanks meant for fish. Plans call for putting the biomix into big tote bags already used for stor-

ing granular fertilizer or pesticide. “Really, you can use anything as a container for the biomix,” Braul says.

The biomix material needs three basic components: topsoil (from a field is best, because it will already have microbes adapted to degrading pesticides); woodchips or straw (to provide the lignin for microbial food and structure); and, compost or peat (to provide the organic matter that absorbs the pesticides).

Among design variations tried in 2015, the most efficient was a two-cell system about a half-metre deep. Each cell has a sixinch layer of crushed rock at the bottom. A sump pump collects leachate from below the crushed rock in the first cell and pumps it to the surface of the second cell. “Two cells remove a much higher percentage of the pesticide than single cell biobeds,” Braul notes.

Although literature from the European experience suggests that nearly all the microbial activity happens in the top six inches of the biobed, most beds are one metre thick to provide additional absorption capacity. At the University of Regina, microbiologist Chris Yost is using DNA testing to determine the type and number of microbes at various depths. Yost hopes to determine the region of greatest microbial activity.

At Outlook, a two-cell biobed only a half-metre deep worked better than expected, Braul says. In practice, degradation of pesticides in the biomix can take three to six months, he adds.

There’s still a need to deal with the reasonably clean leachate coming from the bottom of the biomix, and a need for eventual disposal of the biomix itself. “Effluent has an extremely low level of remaining pesticide. We recommend spraying it on an area that has some organic matter and lots of microorganisms, and allow nature to do its work. One option is to put it into a tank and spray it someplace, or you can sprinkle it safely on grass or drip it along a row of trees. The little amount of remaining pesticide will be degraded in the topsoil,” he says.

Setting up a collection pad for the sprayer rinsate would be the biggest single cost. It can be constructed from heavy plastic but a concrete pad is ideal. “If you want to collect everything you rinse out, you have a fairly large concrete pad. Depending on where you are, it probably could cost $5,000 to $10,000. That’s a big challenge – but some inexpensive creative options are possible,” Braul says.

Brandt is celebrating $1billion in annual revenue and we’re thanking our customers by offering special rebates throughout the year. Visit thanksabillion.ca for details.

You can always count on the Brandt Contour Commander for just-right seedbed preparation. Designed for durability and ease-of-use, this heavy harrow is the ideal solution for no-till, min–till and conventional tillage farms. Whether breaking up and evenly distributing crop residue, warming up the soil in spring, or leveling and sealing, the Contour Commander has superior land following capabilities to ensure an ideal seed bed resulting in smooth, trouble free seeding. Take command of all field terrains with this versatile machine. That’s Powerful Value. Delivered.

The strong and efficient latch system moves effortlessly between field and transport position.

The U-Joint design allows the sections to contour over hilltops and into steep hollows.

Using a parallel link, consistent and even down pressure is delivered to every tine.