TOP CROP MANAGER

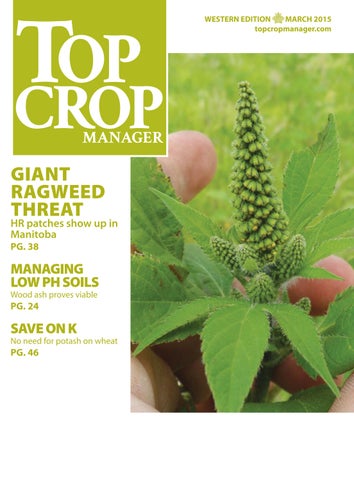

GIANT RAGWEED THREAT

HR patches show up in Manitoba PG. 38

MANAGING

LOW PH SOILS

Wood ash proves viable PG. 24

SAVE ON K

No need for potash on wheat PG. 46

HR patches show up in Manitoba PG. 38

Wood ash proves viable PG. 24

SAVE ON K

No need for potash on wheat PG. 46

Herbicide registrations and label

choices to help target weed challenges and manage herbicide resistance.

approach reduces wild oat and disease pressure.

Low pH soils impact cropping systems

low pH soils with wood ash or lime applications.

JANET KANTERS | EDITOR

If this issue of Top Crop Manager is any indication, we are losing the battle for weed control in Western Canada.

I dislike being the doomsayer in the room, but the statistics speak for themselves. According to the online International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds* (as of Feb. 12, 2015), there are currently 447 unique cases of herbicide resistant weeds globally, with 244 species. Weeds have evolved resistance to 22 of the 25 known herbicide sites of action and to 156 different herbicides. Herbicide resistant weeds have been reported in 85 crops in 66 countries.

In Western Canada, herbicide resistance continues unabated. For its part, Top Crop Manager has featured stories on herbicide resistance for over 20 years now. According to a story we published in March 1993 – “Herbicide resistance: an expanding problem” – by that time in Western Canada, researchers and provincial agricultural advisory staff had been pushing the message of herbicide resistance for about two years. There’s no doubt that researchers and farmers were talking about it much earlier than that.

Today, if you visit topcropmanager.com and enter “herbicide resistance” into the search bar, you will discover 570 stories that include that phrase. Other agricultural publications across the country and, indeed, around the world, also report regularly on herbicide resistance and the havoc it is wreaking. So it’s apparent herbicide resistance has finally gotten the notice it deserves – better late than never I guess.

In this issue of Top Crop Manager, we feature a story on herbicide resistant wild oat. Wild oat is, to date, the most tenacious of the herbicide resistant weeds out there. According to Hugh Beckie, a foremost herbicide resistance specialist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Saskatoon, the weed accounts for over three-quarters of the herbicide resistance cases on the Prairies. “If you don’t have resistant wild oats, you’re in a minority on the Prairies right now,” Beckie says. A truly sobering thought. Read the story on page 50.

Our story on page 10 – “A case study in Group 1 herbicide resistance” – delves deeper into Group 1 resistance of wild oat, which was first discovered in 1984 in Saskatchewan and has steadily grown over the last 30 years.

In this issue, we also talk about other weeds on the Prairies. For instance, volunteer canola is moving up the charts as a pest of note. In our story on page 40, Christian Willenborg, assistant professor with the department of plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan, says volunteer canola creates a lot of risk and negative issues, even in a canola crop itself. He stresses that good rotations of both crops and herbicides are needed for effective control of this pest.

On page 18, we look at Canada thistle, a weed that has consistently ranked in the top five weeds in the Canadian Prairies. One of the take-homes from that story is the need to manage thistle consistently, not every second or third year in rotation because the plant can grow back from its extensive root system if it hasn’t been killed completely. “Even after four years, Canada thistle populations can start to rebound if control measures stop,” AAFC crop management agronomist Bill May says.

We also feature our annual look at new herbicides available in Western Canada. See that story on page 16.

Several other weed management stories are featured in this issue, along with the Weed Control Guide 2015, our annual listing of herbicide products for most crops grown on the Prairies.

With good management practices, our ongoing weed problems – and herbicide resistance issues – can be beat. It may take some time, but with attention to detail and with researchers continuing their studies of the problem, we can meet weeds head-on and win the battle.

* Heap, I. The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds.

Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

email: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Crop Manager West - 9 issuesFebruary, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, September, October, November and December1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada 2 issues Spring and Summer 1 Year $16.00 Cdn plus tax

All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industryrelated groups whose products and services we believe may be

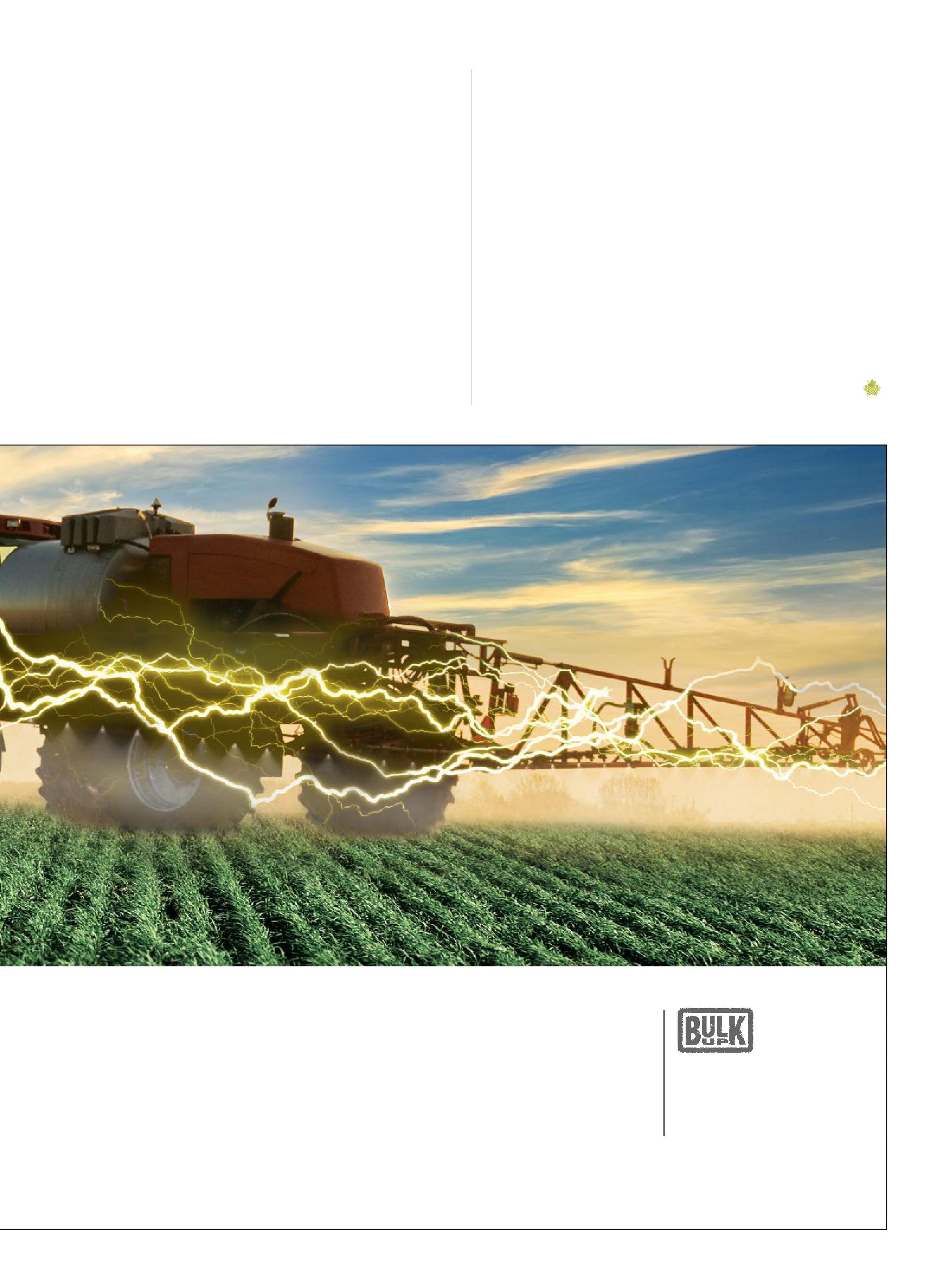

A powerful

combination. *Heat® WG is also an eligible product.

*The Roundup Transorb® HC, HEAT and DISTINCT offer off-invoice discount acres will be calculated using the following

acres), one case of Distinct® = 80 acres (jug of Distinct® = 40 acres), Roundup Transorb® HC 0.67L =

mixtures: The applicable labelling for each product must be in the possession of the user at the time of application. Follow applicable use instructions, including application

Monsanto has not tested all tank mix product formulations for compatibility or performance other than specifically listed by

Roundup Transorb® is a registered trade-mark of Monsanto Technology LLC, Monsanto Canada, Inc. licensee. AgSolutions® and DISTINCT are registered trade-marks of BASF

all used with permission by BASF Canada Inc. MERGE® is a registered trade-mark of BASF Canada Inc. © 2014 Monsanto Canada, Inc. and BASF Canada Inc. Hit weeds where it hurts this season. Monsanto and BASF are once again partnering to promote the use of multiple modes of action and herbicide best practices with a great offer. Save $0.50 per acre on Roundup Transorb® HC when you buy matching acres of Heat® LQ or Distinct® herbicides.* For complete offer details, see your retailer or visit powerfulcombination.ca

Protecting glyphosate herbicide technologies for the future.

by Donna Fleury

Herbicide resistant weeds are continuing to increase in number of species and area across Canada. Glyphosate resistant weeds (Group 9) are increasing their spread, as many growers rely on glyphosate for weed control in Roundup Ready soybean, corn and canola crops, and as a pre-seed or pre-harvest burndown.

According to Peter Sikkema, a professor of field crop weed management at the University of Guelph, Ridgetown Campus, in Ontario, glyphosate-resistant weeds are increasing both in terms the number of fields or counties infested and in the number of species resistant to glyphosate. “In December 2014, another glyphosate-resistant weed was added to the list, bringing the total of glyphosate-resistant weeds to four in Ontario and five in Canada,” he says.

The main reason there are glyphosate-resistant weeds is over-reliance or exclusive reliance on glyphosate for weed control by some producers. For glyphosate resistance to develop, there must be resistant biotypes in the field and there must be selection pressure, which is almost directly correlated with how frequently

glyphosate was applied. Therefore, it is important to implement weed management practices that limit the selection of additional glyphosate-resistant weeds.

In 2008, giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida) was the first glyphosate-resistant weed confirmed in Ontario, followed by Canada fleabane (Conyza Canadensis) in 2010, common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) in 2011 and most recently, waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) in 2014. In Western Canada, glyphosate-resistant kochia (Kochia scoparia) was first confirmed in 2012. In the U.S., there are 14 species resistant to glyphosate and 31 species worldwide. The complexity of the problem in Ontario is exacerbated by the fact there are biotypes of all four species that have multiple resistance to both the Group 2 and Group 9 herbicides.

“Farmers have told us by their purchasing decisions that they like the Roundup Ready technology and the corresponding use of glyphosate for weed control,” Sikkema says. “In 2014 in Ontario,

ABOVE: Glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane in corn.

Increase your yields by using Authority and removing weeds early Kochia and cleavers were put to rest by a group 14 mode of action with extended residual weed control. Lamb’s quarters, redroot pigweed, wild buckwheat and others met the same fate. Authority is registered in peas, flax, soybeans, chickpeas and sunflowers. www.fmccrop.ca

96 per cent of corn and 76 per cent of soybeans were seeded to Roundup Ready hybrids/cultivars. Therefore, it is incumbent on all of us to use this technology properly so that future farmers continue to realize those benefits.”

One of the most important strategies for managing the problem is to have a diversified crop rotation, which would help reduce the reliance on glyphosate. “Try to add a non-Roundup Ready crop to your rotation, and consider adding crops like spring cereals, winter wheat, dry bean, forages or vegetable crops,” Sikkema says. “In those crops, glyphosate is obviously not used for in-crop weed control, although it might be used for a burndown. Also, consider including crops with alternative herbicide resistant traits such as Liberty Link,

and in the near future, Enlist or Roundup Ready Xtend.”

Within every crop in the rotation, consider using more than one mode of action on every acre every year. This will protect that technology for a longer period of time. If you are growing corn or soybean, using a two-pass weed control program is the best way to manage weeds in those crops. Sikkema explains a two-pass weed control system means applying a soil-applied residual herbicide in the spring, followed by a post-emergent in-crop herbicide.

“Our data shows there are very good reasons to do this and the benefits are twofold. In addition to reducing the selection intensity for glyphosate-resistant weeds, our research shows it also maximizes yield.

The weed control and the net returns from a two-pass system are equivalent to a glyphosate only program,” he says.

Although not applicable to every farm operation, another thing farmers should consider, especially in Ontario, is including tillage at strategic points in their crop rotation. This is especially applicable to those species that are winter annuals or ones that emerge really early in the spring.

“One of the biggest problem glyphosate-resistant weeds in Ontario is Canada fleabane, which produces lots of seed –up to one million seeds per plant – that moves by wind and has an extended emergence pattern,” Sikkema says. “A timely tillage operation early in the spring is one practice that can help control emerged Canada fleabane. In contrast, for other glyphosate-resistant weeds like common ragweed or waterhemp, no matter how much tillage you do, it won’t help because they emerge after the last tillage operation is complete.”

Excellent crop management is important to improve the competitiveness of the crop and help reduce the selection pressure for herbicide resistance. Sikkema recommends seeding early in narrow rows and at high populations to improve crop competitiveness. “Seeding at the optimal seeding date and rate, [seeding] in narrow rows, using a balanced proper fertility program, and timely insect and disease control helps the crop outcompete weeds,” he says. “Increased crop competition makes it more difficult for weeds to emerge and complete their life cycle.”

There are several integrated weed management strategies farmers can use, and each individual farmer will have to tailor practices to their operation and determine which components will fit into their overall farming strategy. Farmers in other jurisdictions like Western Canada can learn from these Ontario lessons.

“Implementing good stewardship practices, including weed management practices that limit the selection of additional glyphosate-resistant weeds, will help ensure the usefulness of glyphosate and Roundup Ready crops for many years in the future,” Sikkema says. “The goal for all of us should be to protect and manage these technologies, and reduce the selection of herbicide-resistant weeds so these technologies continue to be of benefit to future farmers.”

Start this season with Wolf Trax Innovative Nutrients. Wolf Trax technologies deliver important nutrients to your crops more effectively, so they can access the nutrients earlier. With a better start, your crops can finish strong – and that’s a better use of your fertilizer dollar. So stand up for your crops, and ask your retailer for field-proven Wolf Trax Innovative Nutrients.

How Group 1 wild oat resistance develops – with insight on how to prevent it.

by Bruce Barker

This story is about what not to do. A long-term cropping study shows how acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) inhibitors (Group 1) wild oat resistance can develop.

Group 1 resistance was first discovered in 1984 in Saskatchewan and has steadily grown over the last 30 years. The most recent surveys of herbicide-resistant weeds was conducted in Alberta in 2007, Manitoba in 2008 and Saskatchewan in 2009, covering 1000 randomly-selected, annually-cropped fields led by research scientist Hugh Beckie and his colleagues at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at the Saskatoon Research Station. Group 1-resistant wild oats were found on 44 per cent of fields where wild oats were sampled, up from 15 per cent from 2001–2003 baseline surveys.

“There isn’t any reason to doubt that the numbers aren’t continuing to grow,” Beckie says.

In an effort to better understand how Group 1 wild oat herbicide resistance develops, Beckie looked at a long-term crop rotation study that was established at the Scott, Sask. AAFC research

farm in 1995. Three different input types were used in three different levels of crop diversity. High-input systems used pesticides and fertilizers based on accepted agronomic recommendations. Reduced input systems used an integrated pest management and nutrient approach, supplemented by chemicals. The third system was an organic system based on non-chemical pest control and nutrient management.

The first six-year crop sequence cycle was conducted from 1995 to 2000, the second cycle from 2001 to 2006, and the third cycle from 2007 to 2012 (see Table 1).

In August 2012, wild oat seed density was measured and seed was collected for screening for Group 1 herbicide resistance. Over the winter, the seed was tested for Group 1 resistance with the Group 1 herbicides fenoxaprop (Puma) and sethoxydim (Poast). The results provide insight into how Group 1 resistance develops

ABOVE: Diversity in spring/fall crops, green manuring/cover crops and use of perennial crops can reduce herbicide selection pressure.

Designed for maximum capacity and speed, the Brandt 7500 HP GrainVac helps you operate at peak effciency. With input from producers like you, we’ve refined our GrainVacs to include many innovative features only available from Brandt. With fewer moving parts, and premium build quality this GrainVac delivers unrivaled reliability and durability. That’s Powerful Value. Delivered.

The patented feature takes the back work out of cleaning right to the bottom of the bin or pile.

This lightweight 8" nozzle adjusts air and grain mixture utilizing louvers and stainless steel adjusting bands to maximize grainflow and capacity.

Fill a 1,000 bushel Trailer in only 8-9 minutes thanks to Brandt’s patented Cone Separator technology which provides optimal separation of the grain from the air stream without any moving parts while maintaining maximum airspeed in all grains.

Utilizes two hydraulic cylinders that allow the auger to fold and unfold while positioned next to the bin.

Hardened steel and chrome plating maximizes grain flow and auger life.

Securely holds the GrainVac in position and provides a safe route for static electricity discharge. It’s sequenced to automatically fold and unfold with the auger.

and what growers can do to slow the development of resistance.

Beckie says the resistance level to fenoxaprop was greatest in the reduced input/diversified annual grain and high input/diversified annual grain systems. The diversified annual grain (DAG) cropping systems had the most Group 1 herbicide treatments with 10 applications in the high input system and seven in the

Table 1. Description of nine alternative cropping systems in a long-term experiment at Scott, Sask.

DAG

DAP

Reduced

Canola-fall rye-pea-barley-flax-wheat

Barley-alfalfa-alfalfa-alfalfa-canola-wheat

LOW TF-canola-wheat-TF-wheat-wheat

DAG

DAP

Canola-fall rye-pea-barley-flax-wheat

Barley-alfalfa-alfalfa-alfalfa-canola-wheat

LOW CF-canola-wheat-GM-wheat-wheat

DAG

Organic

DAP

GM-wheat-pea-barley-GM-mustard

Barley-alfalfa-alfalfa-alfalfamustard-wheat

LOW GM-mustard-wheat-GM-wheat-wheat

x All cropping phases present each year. Fall rye was replaced by soft white spring wheat in the third cycle of the experiment.

Abbreviations: CF: chemical fallow; TF: tilled fallow; GM: green manure (lentil).

DAG: Diversified annual grain; DAP: Diversified annual perennial. Low: Wheat-fallow based system.

Source: Beckie et al. 2014.

Table 2. Number of ACC-inhibiting herbicide applications from 1995 to 2012 in seven alternative cropping systems in a longterm study at Scott, Sask., and wild oat population panicle density (measured in late summer 2012 in the spring wheat phase) and ACC-inhibitor resistance frequency.

Cropping system

Means within a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P<0.05) according to Fisher’s protected least significant difference (LSD) test. DAG: Diversified annual grain; DAP: Diversified annual perennial. Low: Wheat-fallow based system.

reduced DAG system over the 18-year period. These applications were mainly in cereals, barley and wheat, but also could have included the flax cropping years as well.

The reduced input/high diversity cropping system had the highest frequency of wild oat resistance at 60 per cent. The high input/ high diversity cropping system also had very high levels of wild oat resistance at 42 per cent. However, when a short-term perennial crop was included in both high and reduced input systems, the presence of wild oat resistance was dramatically lower. Organic systems did not have any wild oat resistance, which was expected because of the lack of herbicide selection pressure. (See Table 2.)

“We certainly know that including a perennial crop in the rotation will slow the development of resistance because herbicide use is reduced and seed production of annual weeds is suppressed,” Beckie explains. “The difficulty for farmers is with the integration and profitability of perennial crops.”

One interesting finding was that no wild oat resistance was found to sethoxydim. This active ingredient is also a Group 1 herbicide but in a different subgroup than fenoxaprop. Within Group 1, there are three chemical families commonly called the fops, dims and dens. Weed populations may evolve to be resistant to one subgroup but not another, but may also evolve to be resistant to all subgroups.

“I was a little surprised to see that the wild oats weren’t resistant to both fenoxaprop and sethoxydim. We looked at the target site mutation and it only conferred resistance to the fops,” Beckie explains, adding the explanation may be as simple as that HoeGrass (diclofop-methyl) had been used as far back as 1976, and that the fop selection pressure had a longer history on the wild oat population at the site.

“In a case like this, a farmer can be lucky in that only the fops had developed resistance and he still has the dims and dens left to use,” Beckie says. “I advise farmers that if they have suspected fop resistance and they still want to use a Group 1 herbicide, try the other classes in the group. It is a short term strategy but may work for a while.”

Beckie also says the research shows that just including a diversified annual cropping rotation isn’t enough to head off herbicide resistance, because it may not have enough herbicide diversity. He explains that based on grower surveys from 2006 through 2010, Group 1 herbicides were applied to 100 per cent of flax acres, 86 per cent of barley, 76 per cent of wheat, 44 per cent of lentil and 24 per cent of pea.

Good herbicide resistance management includes not only herbicide rotation but also “real” crop diversity and herbicide use reduction through the use of perennial crops or cover/green manure crops.

“We need to be careful when we define cropping diversity. In Western Canada we mostly have annual spring seeded, cool-season crops. Even with this diversity it helps, but it isn’t really cropping diversity. What we need is some diversity between springand fall-seeded crops, green manure/cover crop versus chemical fallowing if possible, and using perennial crops. Those types of diverse rotations help reduce selection pressure,” Beckie says. “Perennial cereal crops would make a big dent in herbicide resistant management if or when they are commercialized.”

Source: Beckie et al. 2014. For

Too much or too little water can affect the quality and yield of your crop. And when the decisions you make on your farm impact this natural resource, what matters most is how you use it. Whether you farm from the cloud or the field, know you have the control and precision to make each drop count.

Introducing the Irrigate-IQ™ precision irrigation solution from Trimble. See it at www.trimble.com/agriculture. For the field. For the yield. For the life of your farm.

Research shows a high seeding rate is not a valid herbicide resistance solution.

by Madeleine Baerg

New research from the University of Wisconsin-Madison refutes the widely held belief that growers should employ a high soybean seeding rate in order to counter herbicide resistance.

Because a higher plant density generally results in a thicker crop canopy, it might seem intuitive that seeding heavily will improve weed control and reduce the likelihood of weeds overcoming herbicides. In fact, this supposition forms the basis of the integrated weed control advice given by many agronomists and crop researchers.

According to Vince Davis, an assistant professor of cropping systems and a weed science extension specialist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and co-lead on this research, within that logic is a vital flaw. Specifically, herbicide resistance does not develop at a stage in the season when crops are big enough to impact weeds competitively. Therefore, Davis argues, seeding rate cannot positively or negatively impact herbicide resistance development at all.

“We have long known that extra crop plants are helpful for overall weed control throughout the season because they compete with weeds. However, how do extra plants help specifically with resistance management?” he says. “I’m a bit of a lone ranger on this. Ultimately, there are a lot of people who will say we should continue to preach high seeding rates for weed control. I don’t disagree with that thinking, but we have to think of how herbicides work and when resistance develops, and then make seeding decisions based on economics.”

Given that the price of soybean seed has increased by more than 200 per cent in less than two decades, producers need to be very sure of what increased seeding can and cannot achieve, since farm profitability can be hugely impacted by seeding rate. Herbicide resistance develops at the moment that weeds face selection pressure from a herbicide. In other words, herbicide resistance develops at the time of herbicide application. If the moment of resistance development occurs when a pre-emergent herbicide is applied, the crop will be in seed form, so will have no competitive effect on weeds. If, instead, the moment of resistance development occurs when a post-emergent herbicide is applied, the crop will have emerged but is too small to place any significant competition pressure on weeds. Therefore, while a heavy crop canopy later in the season will decrease weed biomass, it will not stop resistance development because that resistance will already have developed many weeks before.

“To reduce selection pressure that could result in weeds overcoming a herbicide, you have to decrease the number of weeds exposed to that herbicide. When someone says growers should use more seed as a resistance management tactic, to me that means those extra plants have to have an effect on the amount and size of

weeds exposed to the herbicide, which isn’t possible when the crop plants are tiny,” Davis says.

Davis’ research instead suggests another tactic for battling resistance. The reality is that growers have few options to solve any herbicide failures after a post emergent herbicide application. Therefore, producers should opt to counter resistance as early as possible with a herbicide applied at the pre-emergence timing.

“We sometimes take criticism when we say we need to use more pre-emergence herbicides to protect us from herbicide resistance at post emergence. Some people will say that we’re just advising them to use another chemical to prevent chemical resistance. But, when you use a herbicide at the pre-emergence timing, you have time to react to failures by implementing a post-emergence mop-up. You have a greater window to make better choices to fix failures. If you only opt

for a single application at the post-emergence timing, you don’t necessarily have the opportunity to solve resistance issues,” he explains.

To study the impact of seeding rates when used with and without pre-emergent herbicide, Davis and co-researcher Shawn Conley planted field trials in Wisconsin in 2012 and 2013. The plots were planted at five different seeding rates, half of the plots were treated with a residual pre-emergent herbicide, and then all plots were treated post-emergently with either conventional herbicides or conventional herbicides and glyphosate.

During the course of this research, Davis and Conley used digital analysis technology to be able to quantitatively analyze the amount of cover soybean plants achieved using various herbicide management practices. The finding that surprised the researchers most was that applying herbicide at pre-emergent timing produced an increase in soybean canopy development.

“What we are saying is that using a pre-emergent herbicide is not only the better chemical means to prevent chemical resistance, we also get more canopy development, so we are getting more cultural

weed control. This finding was really not expected. Even at lower seeding rates, we saw a better canopy development,” Davis says.

With proper resistance-management focused weed control in place, producers should make a seeding rate decision based on good agronomics and solid economics.

“At the end of the day, the economics of seeding rate should be determined by those relationships you’d expect under a weed-free environment. Growers should make their rate decisions based on their yield expectations for their geography and not necessarily on the expectation of additional weed control,” Davis says.

“I don’t necessarily disagree with the conventional thinking that encourages using extra seeds for weed control,” he says. “If we go back 15 or 18 years, it was really economical to do that because soybean seeds were so much cheaper. But today, a lot of people with a lot of experience still have the mindset that you can ignore the economics of soybean seeding rate. What has changed over the last decade or so is the cost of soybeans. It’s not an economic decision that should be ignored anymore.”

Expanded choices to help target weed challenges and manage herbicide resistance.

by Bruce Barker

New herbicide product registrations and label updates continue to bring more choice to farmers managing weed infestations and herbicide resistance. All product information is provided by the manufacturers.

Heat LQ: saflufenacil (Group 14) — A new, easy-to-use liquid formulation for preseed, pre-emergence and chemfallow applications.

Korrex: florasulam (Group 2) and dicamba (Group 4) — A preseed herbicide designed for mixing with all glyphosate formulations, offering SoilActive technology weed control and multiple modes of action on kochia to manage risk of glyphosate resistance. Registered preseed prior to planting wheat, barley or oats.

PrePass FLEX: florasulam (Group 2) — A preseed product for cereal crops with the flexibility to be tank-mixed with any glyphosate formulation. Ideal for farmers who purchase multiple types of glyphosate or who have already purchased their glyphosate supply, it provides SoilActive control of several broadleaf weeds for 21 days, including volunteer canola.

Odyssey Ultra: imazamox and imazethapyr (Group 2) and sethoxydim (Group 1) — Combines two different herbicide groups for early-season-flushing broadleaf weed control and superior grass control from Poast Ultra (sethoxydim). Registered in field pea, soybean, Clearfield canola and Clearfield lentil.

Salute: imazamox and imazapyr (Group 2) and clopyralid (Group 4) — A highly effective single pass herbicide combination for use in Clearfield canola. It provides excellent control of wild oats, wild buckwheat, lamb’s-quarters, cleavers and several other key broadleaf weeds in addition to systemic control of Canada thistle.

Paradigm: arylex (Group 4) and florasulam (Group 2) — Delivers high performance broadleaf weed control in wheat, durum, barley and winter wheat over a wide range of climatic conditions, weed species, and weed and crop stages with Multi Mode of Action control built in for superior resistance management. Paradigm is an ultra concentrated dry formulation utilizing new GoDRI Rapid Dispersion Technology, a dry formulation that works like a liquid.

Pixxaro: arylex and fluroxypyr and MCPA Ester 600 (Group 4) — Delivers high-performance broadleaf weed control in wheat, durum, barley and winter wheat over a wide range of climatic conditions, weed species, and weed and crop stages. Consists entirely of Group 4 mode of action, and controls many common broadleaf weeds including kochia, with complete grass tank-mix flexibility.

Rush M: fluroxypyr and MCPA ester (Group 4) — Registered for use on spring wheat, durum wheat and barley, controlling a wide spectrum of broadleaf weeds including chickweed, cleavers, kochia, hemp-nettle, volunteer flax and wild buckwheat. It is ideal for cleaning up herbicide-tolerant canola volunteers, and excels at controlling Group 2-resistant weeds that are now common on the Prairies, including kochia, common chickweed, cleavers, spiny sow-thistle and wild mustard.

Outshine: florasulam (Group 2), fluroxypyr (Group 4) and MCPA ester (Group 4) — Registered on spring and durum wheat and barley, providing broad-spectrum weed control from three active ingredients and two modes of action. Works on tough broadleaf weeds such as cleavers, chickweed, hemp-nettle, kochia and wild buckwheat.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 22

ABOVE: New herbicides and label updates are helping farmers cope with weed resistance.

Even though it looks the same, it’s not. Volunteer canola can provide a host for dangerous diseases, steal nutrients and limit the yield performance of your crop. But moving forward, this doesn’t need to be a problem.

Pardner® herbicide is now registered as a pre-seed, tank-mix partner with Roundup® WeatherMAX® herbicide and other similar glyphosate technologies for control of all volunteer canola, even if they’re tolerant to other herbicide groups.

For more information, visit BayerCropScience.ca/Pardner

by Donna Fleury

Aproblem perennial weed in many cropping systems, Canada thistle, has consistently ranked in the top five weeds in the Canadian Prairies in relative abundance.

To optimize perennial broadleaf weed control, herbicide selection and use must be co-ordinated with crop rotations and cropping practices over the long term.

Researchers with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Indian Head, Sask. and the University of Saskatchewan conducted a four-year project to study the effect of herbicide timing and intensity on the control of Canada thistle in a cereal-oilseed-cereal-pulse rotation under a no-till management system. Trials were set up at Indian Head and Saskatoon from 2004 to 2008. The previous cropping system was low-input minimum tillage at all sites. The Canada thistle densities at Indian Head were 40 to 50 Canada thistle plants per square metre in an existing field, and densities at the other sites were slightly lower.

“The study was set up with six treatment combinations varying in intensity and timing of Canada thistle control with clopyralid

being applied in-crop, and glyphosate being applied pre-harvest, post-harvest or in-crop,” AAFC crop management agronomist Bill May says. The six treatment combinations were check (no perennial weed control), clopyralid high intensity, glyphosate high intensity, clopyralid + glyphosate high intensity, clopyralid + glyphosate medium intensity and glyphosate medium intensity. A preseed glyphosate application was included in all treatments.

The treatments were applied to a wheat-canola-barley-pea rotation with all four phases of the rotation grown each year. For the cereal crops in rotation, an in-crop application of Buctril M was used for the check and glyphosate medium and high intensity treatments, while Curtain M was used in cereals for the clopyralid high intensity and the two clopyralid combinations with glyphosate. An in-crop application of Odyssey was applied to the pea crop

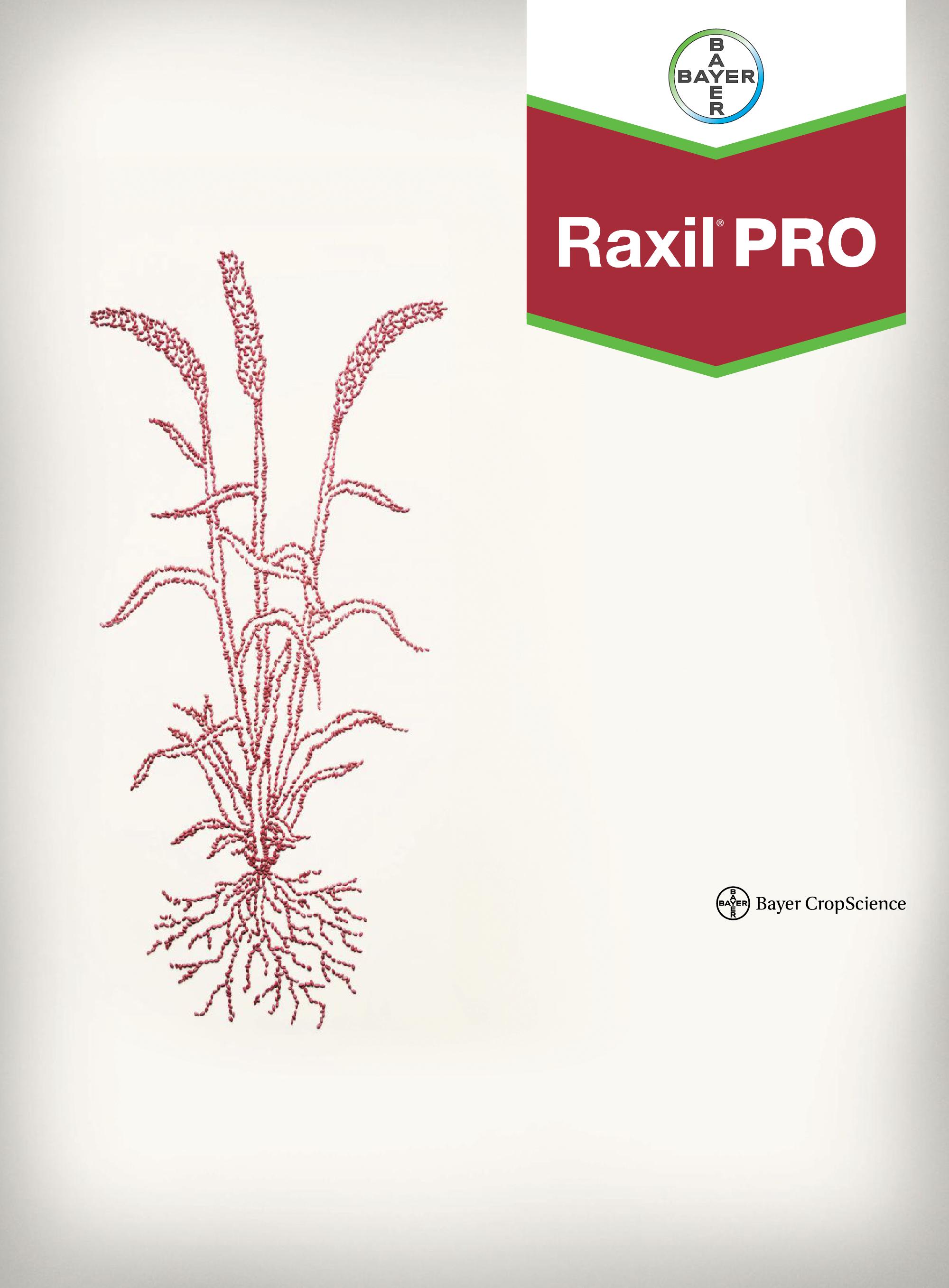

TOP: Glyphosate high intensity treatment in year four of the study at Indian Head.

INSET: Clopyralid + glyphosate high intensity treatment in year four of the study at Indian Head.

DISCOVER COMFORT, PRODUCTIVITY AND QUALITY FROM THE WORLD’S MOST POWERFUL COMBINE.

COMFORT. All-new Harvest Suite™ Ultra cab with 68 ft2 glass and acres of space for unsurpassed visibility and operating ergonomy. Smooth ride SmartTrax™ system with Terraglide™ suspension.

PRODUCTIVITY Largest ever 410 bu. grain tank, 4 bu./sec unloading speed, 34 ft. pivoting auger for greater unloading flexibility.

QUALITY. Unique Twin Rotor™ threshing system, 10% higher capacity with Twin Pitch technology, crop accelerating Dynamic Feed Roll™ for even higher throughput.

POWER. Mighty Cursor 16 ECOBlue™ HI-eSCR engines for Tier 4B compliance and 10% fuel savings. Up to 653 hp on the new CR10.90, the world’s most powerful combine.

www.newcr.newholland.com

in rotation. Roundup Ready canola received an in-crop application of glyphosate with all of the treatments, except the glyphosate high intensity treatment that included two in-crop glyphosate applications, and the clopyralid high intensity treatment that included an in-crop application of Eclipse.

The study results showed differences between the treatments in their control of Canada thistle and subsequent effect on grain yield. “Overall, the five treatments with some Canada thistle control increased the visual control of Canada thistle and reduced the density of Canada thistle compared to the check,” May explains. “Two treatment combinations, the glyphosate high intensity (pre- or post-harvest) alone or in combination with clopyralid (in-crop) were the most effective in reducing Canada thistle density and increased visual control of Canada thistle more than the other three treatment combinations. These two treatment combinations also had a higher yield in all four crops compared to the check. In addition, the clopyralid high intensity treatment combination increased grain yield compared to the check in three out of four crops.”

In the study, all four crops were grown in rotation every year. However, the results showed there was little difference in which crop was the first one in rotation. Averaged over the four years of the study, there was little difference in grain yield, Canada thistle control or Canada thistle density in any of the crop rotation combinations. This indicates that control of Canada thistle can be successfully initiated when any of these crops are grown.

“We used good agronomic practices in all of the treatments in the study, as well as the herbicide treatments,” May says. “Using proper fertilizer rates, earlier seeding dates, good timing of annual

weed control applications and good harvest management actually started to lower the counts of Canada thistle every year as we went along, even in the check treatment. Good management practices definitely helped us manage the Canada thistle, although it didn’t mean an automatic yield increase.”

May adds there can be an allelopathic effect of Canada thistle in the crop, so high density of the weed one year can affect a crop’s yield the next year. “As soon as you let off the control of Canada thistle or control was weak, then the Canada thistle started bouncing back fairly quickly,” he notes. “That’s the problem with trying to manage thistle every second or third year in rotation. If you don’t manage it consistently, then the populations sneak back up and take over. The plant can grow back from its extensive root system if it hasn’t been killed completely. Therefore, it takes at least two or three years of a concerted effort to get Canada thistle controlled. Even after four years, Canada thistle populations can start to rebound if control measures stop.”

The results from this study indicate that combinations of incrop and post-harvest applications of herbicides can be effectively used to control Canada thistle. The control can be successfully initiated in most crops in a rotation sequence, even when a weakly competitive crop like peas are being grown. A consistent approach over several years is required to gain effective control of Canada thistle.

INSURE YOUR REVENUE, NOT YOUR CROP.

With production cost insurance you take care of your crop, we’ll take care of your paycheque.

As the season matures and your needs change, you’re covered. No matter what you choose to seed or spray— you’re insured for everything you put in the ground.

Talk to your advisor soon for details.

Find an advisor near you I agrisksolutions.ca

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 16

Assure II: quizalofop (Group 1) — Registered for control of downy brome, a tough-to-kill weed that is rapidly expanding throughout the Prairies. Assure II controls tough grassy weeds such as foxtail barley, wild oats and volunteer cereals in canola, flax and pulse crops. Can be applied at any crop stage and has no re-cropping restrictions for the following year.

Authority: sulfentrazone (Group 14) — Registered for preplant/ pre-emergent weed control, and now registered prior to soybeans. Cleaver control has been added to the label. For additional weed control in field peas, a new tank-mix with imazethapyr (Group2) has been added to the label. Provides preplant/pre-emergence control of kochia, redroot pigweed, lamb’s-quarters and wild buckwheat, and provides suppression of cleavers in soybeans, field pea,

flax, chickpea and sunflower.

Authority Charge: sulfentrazone + carfentrazone (Group 14) — Now registered prior to soybeans; cleaver control has been added to the label. For preplant/pre-emergence control of kochia, redroot pigweed, lamb’s-quarters and wild buckwheat, and provides suppression of cleavers in soybeans, field pea, flax, chickpea and sunflower. For additional weed control in field peas, a new tank-mix with imazethapyr has been added to the label. Also, can be tankmixed with glyphosate for added burndown weed control.

Axial BIA: pinoxaden (Group 1) — Label expansion includes use on winter wheat along with spring wheat and barley from the one leaf to flag leaf stage. A post-emergent herbicide for the control of grass weeds, including wild oats, green foxtail, yellow foxtail, barnyard grass, volunteer oats, volunteer canary seed and proso millet.

Distinct: dicamba (Group 4) and diflufenzopyr (Group 19) — Provides superior activity on tough-to-control broadleaf weeds, including kochia, dandelion and herbicide-resistant biotypes. Expanded into Western Canada for use on corn (two to six leaf stage), along with the addition of volunteer canola control in corn. In chemfallow, narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard and wild buckwheat added to the 100 g ai/ha rate. A new 200 g ai/ha rate registered for chemfallow/post-harvest weed control.

Everest 2.0: flucarbazone (Group 2) — Winter wheat has been added to the label. Can now be applied in fall or spring from the one leaf to jointing stage of winter wheat. For control of wild oats, green foxtail and some broadleaf weeds such as volunteer canola, stinkweed, redroot pigweed, wild mustard and shepherd’s purse.

Focus: pyroxasulfone (Group 15) and carfentrazone (Group 14) — Now registered for preplant/pre-emergence control of foxtails (green, yellow, giant), barnyard grass, Italian ryegrass and large crabgrass, plus redroot pigweed and common waterhemp in corn and soybeans. Can

be tank-mixed with glyphosate for added burndown, and tank-mixed with atrazine in corn for wide-spectrum weed control.

Inferno Duo: flucarbazone + tribenuron (Group 2) — When applied with glyphosate at 180 g ae per acre, now registered for control of foxtail barley up to 10 cm in height in spring wheat (not including durum). For foxtail barley greater than 10 cm, or for heavy infestations or stressed plants, mix with 360 g ae glyphosate per acre.

Valtera: flumioxazin (Group 14) — Now registered for use ahead of field peas (fall application before freeze-up) to control kochia and other labelled weeds. Provides exceptional pre-emergence control of tough weeds such as eastern black nightshade, pigweed and lamb’s-quarters, including those resistant to Group 2 and triazines with crop rotational flexibility.

Viper ADV imazamox (Group 2) and bentazon (Group 6) — Approved minor use for established alsike and red clover grown for seed. Controls a wide range of grassy and broadleaf weeds.

• 40 acre cases, 240 acre drums, 1,280 acre totes • Easy, tank mixable, crop safe, time for an

to the new dowagro.ca or

*91% of the 431 farmers surveyed across Western Canada said they were pleased with the results OcTTain delivered. Of the users surveyed: 47% were very satisfied, 44% were satisfied, 6% were neutral and only 3% were dissatisfied. Dow AgroSciences 2014 OcTTain Customer Satisfaction Survey.

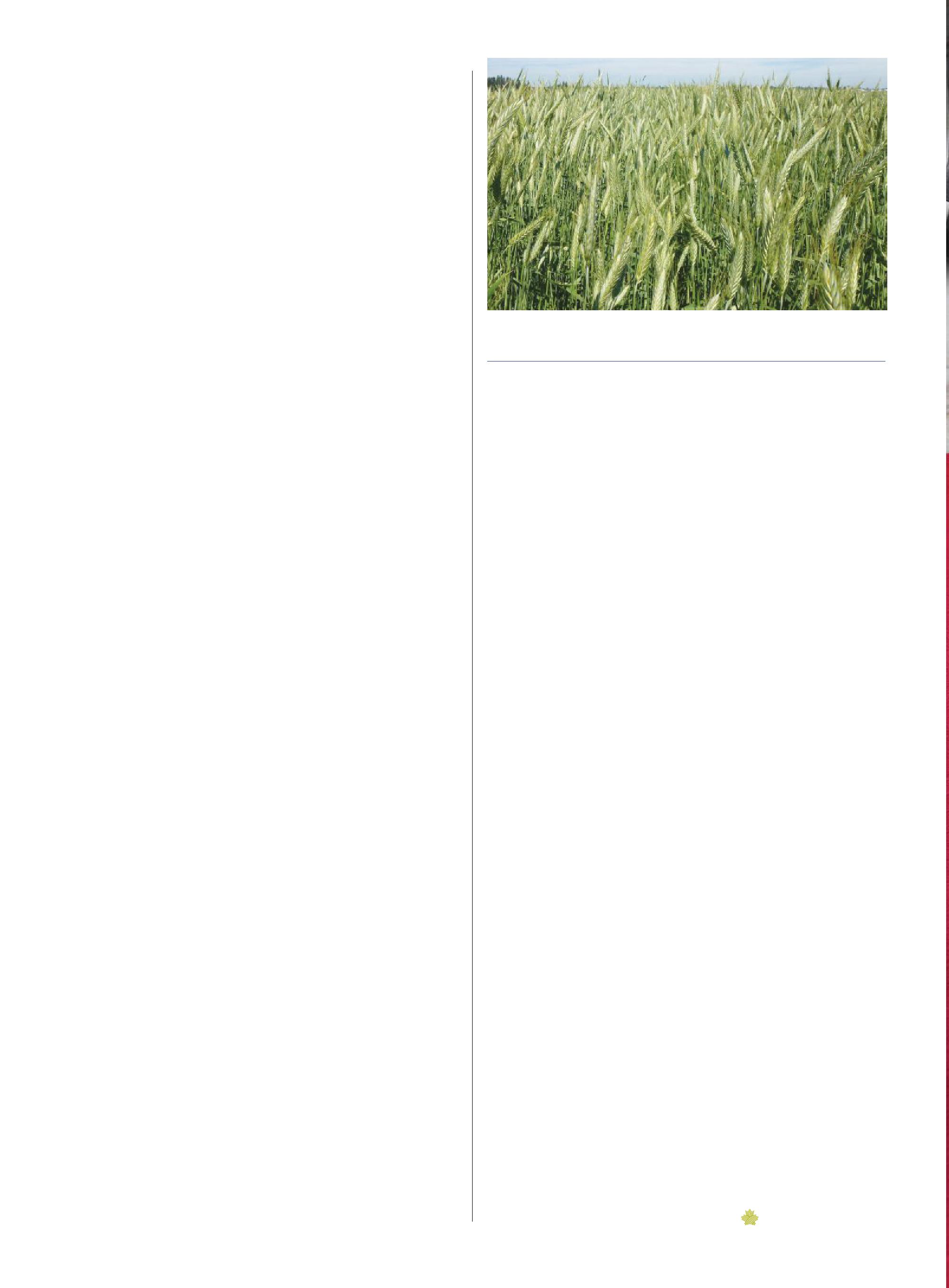

Improve low pH soils with wood ash or lime applications.

by Donna Fleury

In some crop production areas of Western Canada, soils with low pH can create challenges for growers, and impact yields and crop rotation options. For most crops, the ideal pH level is in the range of 6.2 to 6.8. Most nutrients are readily available at these levels, optimizing plant growth and improving crop competitiveness.

Acid soils are those having a pH of 6.5 or less. An estimated 6.3 million acres of soils in Western Canada have a pH of 6.0 or less and an additional 8.5 million acres have a pH of 6.1 to 6.5. According to Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development (AARD), over 90 per cent of sufficiently acid soils that reduce alfalfa growth occur in Alberta, including 1.35 million acres in the Peace River Region of Alberta and British Columbia.

When soil pH is less than 6.0, the growth of acid sensitive crops, such as alfalfa and sweet clover, is reduced. Barley is considered to be moderately sensitive, and growth is affected when pH is less than 5.8. Canola, wheat and corn are slightly more tolerant of soil acidity than barley to 5.5, while oats and the forage grasses, such

as timothy and creeping red fescue, are very tolerant and can be grown successfully at a soil pH of 5.0.

“In much of the area south and north of Edmonton and into the Peace Region, many of the soil tests indicate a soil pH of less than six, often getting down to between 5.3 and 5.6 and as low as 4.8 to five,” Dan Orchard, Canola Council of Canada agronomy specialist for north-central Alberta says. “Canola crops are fairly tolerant at these soil pH levels; however, crops like barley may be almost impossible to grow at a lower soil pH. As well, some fertilizers like anhydrous ammonia and elemental sulphur are a bit more acidic and can contribute to lowering the soil pH over the longer term.”

Growers can consider an application of agricultural lime or wood ash to raise the pH. “Although it is challenging to alter the pH, for example it may take seven or 10 or more tonnes of lime per

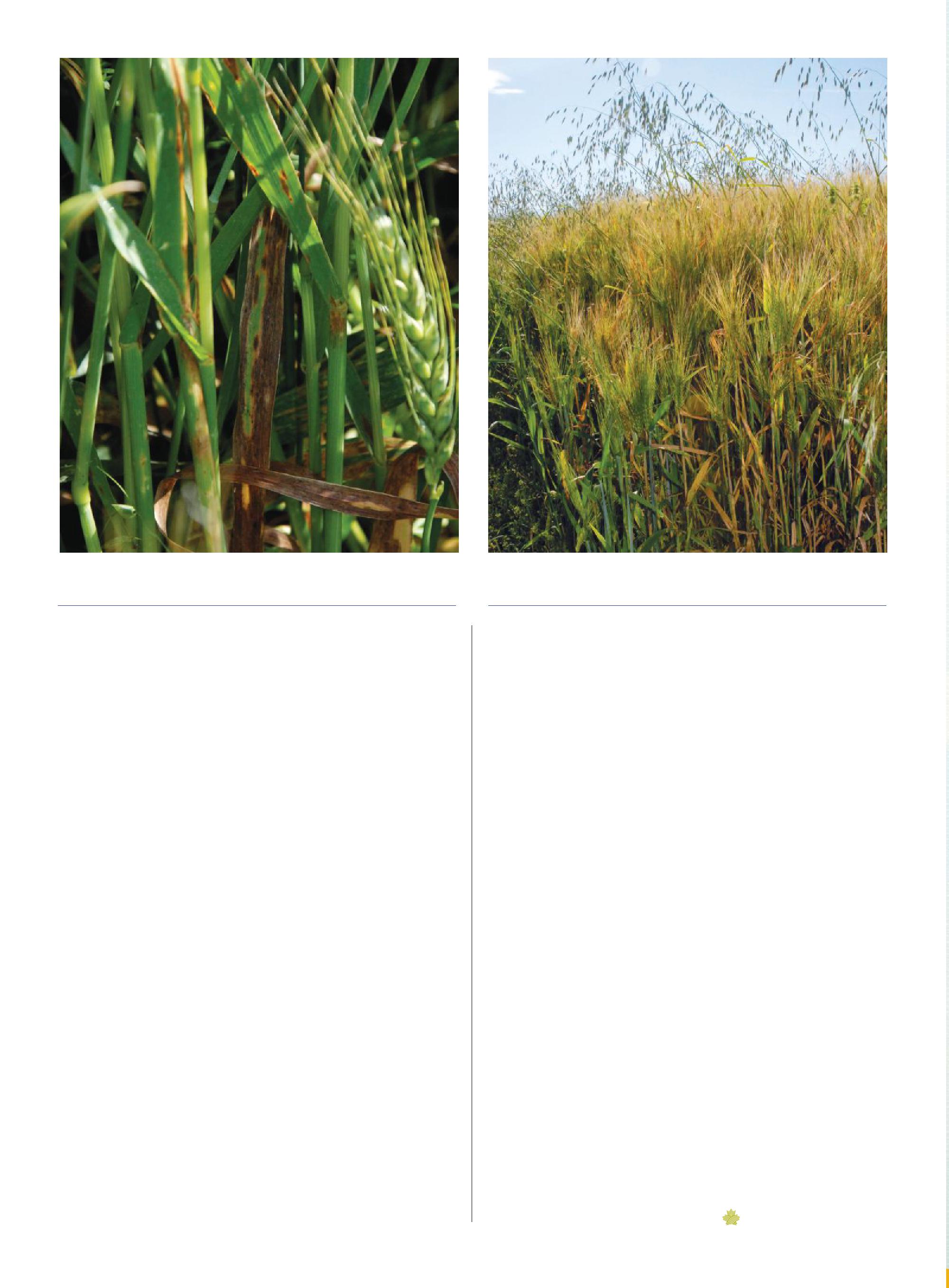

TOP: Barley growth is affected when pH is less than 5.8 and can benefit by increasing pH levels with wood ash.

INSET: Wood ash proved to be a viable product for raising pH levels.

The 24/7, all season nitrogen buffet.

ESN® SMART NITROGEN® is always there for your crops. One application will typically give your crops the N they need throughout the growing season. The polymer coating reduces the risk of nitrogen loss to the environment, and you can apply ESN at up to three times the seed-safe rate of urea. It improves crop quality and yield. Get the facts from your retailer, or visit SmartNitrogen.com.

acre to raise the pH one point depending on soil type, one application will last for years,” Orchard says. “Therefore, the cost can be amortized over several years and, once corrected, it will be a long time before it will need to be corrected again.”

John Heard, soil fertility extension specialist with Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Development (MAFRD) notes there are few areas in Manitoba with low soil pH. There are a few pockets mostly on the east side of the province, and a few other isolated locations. “In northwestern

Ontario, there have been many trials with wood ash applications, which proved to be very effective liming material and much cheaper than lime,” Heard says. “Similar research in an acid pocket of soil in northwestern Manitoba, just west of Dauphin, has shown wood ash to be effective in increasing productivity. Precision farming techniques, such as intensive soil sampling, has also identified acidic areas in well-drained sandy fields in the Carberry area. For soils that are closer to neutral, such as 6.5 pH, liming is not required and

may actually cause detrimental effects, such as on table potatoes where the bacteria that causes scab prefers higher soil pH.”

Along with improved crop production, there can be other reasons to increase soil pH. For some crops like soybeans, the crop may not require a higher pH, but the rhizobium bacteria that fix nitrogen need a higher pH for growth and survival. Soil pH can also affect the residual characteristics of some herbicides.

“For example, some of the Group 2 herbicides, such as Pursuit and Odyssey; their persistence in the soil is longer in acid soil,” Heard says. “Therefore, a proper soil pH and moisture conditions are required for the orderly breakdown of products to prevent carryover.”

Wood ash, the calcium carbonate-rich residue remaining from the combustion of bark, sawdust and yard waste for energy generation for forestry product operations, is an effective liming material on acid agricultural soils. Many of these forestry operations are in the northern Prairies, where a large percentage of highly acidic soils are located.

You’ll like that new tractor even more

Get pre-approved with FCC Equipment Financing and you’ll be ready when you see the right deal. Finance new or used equipment through more than 800 dealers across the country.

Call us at 1-800-510-6669 and get pre-approved today. fcc.ca/Equipment

Researchers with the University of Alberta and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) conducted several experiments in northwestern Alberta at Beaverlodge to determine the effects of wood ash and lime, applied at an equivalent calcium carbonate rate, on soil properties, nutrient availability and crop production from 2002 to 2005. A separate study investigated the effects on soil microbiological properties.

In the four-year study, barley, canola, and field pea were grown in rotation every year. The soil amendments were applied once in the first year on a clay loam soil with an initial pH of 4.9. Wood ash was applied at a calcium carbonate rate of 6.72 tonnes/ha and compared with an equivalent rate of agricultural lime, plus a control without lime or wood ash. Overall, the soil pH was increased by about two points to 6.8 on average.

“Wood ash proved to be a very good amendment and all of the crops in the trials benefitted from the higher pH levels,” Newton Lupwayi, research scientist with AAFC in Lethbridge, Alta., says. “In this study, wood ash was as effective as agricultural lime in increasing soil pH, available nutrients, soil aggregation and crop yields. Lime works very well too; however, it can

Table 1. Crop yields (averages from 2002 to 2005) following application of lime and wood ash at a calcium carbonate rate of 6.72 tonnes/ha in northeastern Alberta.

Crop/Treatment 4-yr

Source: Newton Lupwayi, AAFC Lethbridge.

be quite expensive. So for those growers with access to wood ash, such as those in northwestern Alberta, they can use that as an alternative to a lime application. Wood ash is quite dusty to apply, so if there was a way to convert ash to a granular product, it would be an advantage.”

Averaged over four years, the application of wood ash increased grain yields of barley, canola and pea by 49, 59 and 55 per cent, respectively, compared to a corresponding increase of 38, 31 and 49 per cent by agricultural lime (see Table 1).

“Wood ash has an advantage over agricultural lime in containing a significant amount of P and other nutrients,” Lupwayi explains. “The study also showed that wood ash also increased soil P availability more than lime, bringing soil pH to the optimum range for root growth and increasing P solubility.”

The effect of wood ash and lime application on pH and available phosphorus (P) was greatest in the 0- to 5-cm depth, less but still significant in the 5- to 10-cm depth, and not significant below 10 cm. Wood ash also significantly improved the soil microbiological properties, and after four years of application, the levels of microbial biomass carbon were still almost doubling in bulk soil.

“In acid soils, crops really struggle. So by improving the soil pH through an application of wood ash or lime, crop production, soil quality and soil microbes all improve,” Lupwayi says.

When tough broadleaf weeds invade your cereal crops, it’s no time for half-measures. You need action now. With a new and more concentrated formulation, DuPont™ Barricade® II herbicide leverages the strength of three active ingredients from 2 diferent groups (Group 2 and Group 4) to keep broadleaf weeds far away from your crop. Powered by Solumax® soluble granules, Barricade® II also delivers one-hour rainfastness and easier, more consistent sprayer cleanout. It’s no wonder

powered by Solumax® soluble granules, combining

Questions? Ask your retailer, call 1-800-667-3925 or

narrow-leaved hawk’s beard, kochia, cleavers, fixweed, lamb’s-quarters, cow cockle, volunteer canola

multiple modes of action from two groups – Group 2 and Group 4.

An ef ective, time-saving formulation. Barricade® II is powered by DuPont™ Solumax® soluble granules, combining the c

Patience is a virtue when growing soybeans.

by Anne Cote

La Coop fédérée crop specialist François Labrie visited Manitoba in November 2014 and he brought along some tips for prairie soybean growers.

Labrie says in order to maximize soybean yields, growers have to understand the physiology of soybeans in the field, emphasizing that patience is a virtue when growing the crop.

Labrie says there are eight opportunities during the growing season where a grower’s decisions will affect the crop yield and profits. The first decision is the choice of a seed variety. Labrie says price and yield statistics aren’t the only factors to be considered when buying seed. Field conditions and planting times are also factors. Labrie suggests buying a variety suited to the growing season, soil conditions and resistance to local diseases and fungus infections.

His advice to growers is to plant the variety they’ve purchased at the recommended planting date. “Keep your seeds for planting at their best date. If it’s too late for them, plant a different crop,” he notes, cautioning growers shouldn’t wait too long for the ground to dry before planting as waiting to seed will reduce yield.

“If the ground is suitable for seeding, then go. If soils are very wet during the optimum planting time, stay out of the field,” he says. That’s the time to decide on whether it’s worth planting a soybean crop in that location.

According to Labrie, soybeans respond to seasonal changes in daylight and don’t rely as heavily on heat days for reproduction as corn does. Soybeans switch from vegetative growth, or trifoliolate development, to reproductive growth on June 21, the day with the most daylight hours during the year. He notes the reproductive efficiency of soybeans is quite low compared to other crops with only half the flowers on a plant producing pods. The challenge for growers is to encourage the soybean plant to produce as many trifoliolates as possible before the summer solstice using optimum seed positioning, effective row spacings and planting at just the right time.

Labrie says research indicates the optimum time for planting soybeans in Eastern Canada is before May 15 and he suggests that farmers in Western Canada should plant before May 25. So growers should relax and get their corn, which relies on heat days for development, planted before the soybeans which develop according to the available daylight hours. In fact, he says, early planted soybean seeds simply sit in the ground. Nor does an early planting mean an equally early harvest. The gain in harvest time is only one day for each three days of early planting.

The goal is to get the seeds sprouting as quickly as possible. The first leaf, or unifoliolate, has just one job and that’s to get photosynthesis underway to foster the development of the first trifoliolate. That’s when the process of nitrogen fixing begins and the foundation for a good yield is established. Labrie says there should be a new trifoliolate every four days after the first one develops, and by June 21 each plant should have four to five trifoliolates.

Announcing an innovative partnership between Case IH and Precision Planting.® The technology that allows each Early Riser ® row unit to adapt to the distinct conditions of your field now comes to you in a distinctly different way. You can now get it installed, serviced and supported on the industry’s best planter right at an authorized Case IH/Precision Planting dealer. It helps you get more out of every planting season and improve the yield potential in every field. Learn more at your local Case IH dealer or online at caseih.com/planter

BE READY.

Every year, cereal crops emerging from untreated seed fall prey to a host of disease and insect pests. Fusarium, pythium and wireworms cause significant damages, and along with other common pests, severely reduce plant stands and yield potential. 2015 will be an especially challenging year as diseases such as fusarium graminearum are rampant on seed samples.

Wheat growers in Western Canada have a new option to protect their investment with the introduction of NipsIt™ Suite seed treatment from Nufarm Agriculture Inc.

“NipsIt expands our portfolio to provide more resources and crop production solutions to help growers produce healthier, higher yielding crops,” says Roger Rotariu, Marketing Manager with Nufarm Agriculture Inc. “NipsIt complements our portfolio of weed control solutions and delivers the best active ingredients to control the most important disease and insect pests in Canada.”

Introduced in late 2014, NipsIt delivers complete seed and seedling protection with distinct advantages over competitive seed treatment products. The all-in-one fungicide and insecticide formulation provides increased plant stands and enhanced plant growth for more consistent yields. Registered for wheat in Canada, with barley registration imminent, NipsIt contains Lock Tight™ Technology to make it easier to apply, and enhances seed flow consistency and minimizes dust off.

NipsIt delivers the best actives to control the most pests in a great formulation. Three active ingredients – Group 4 insecticide (clothianidin), Group 4 fungicide (metconazole) and Group 3 fungicide (metalaxyl) – deliver broad-spectrum protection from the most common early insect and disease problems. “Growers will get great seed and seedling fusarium control and excellent wireworm protection, and they can expect the same growth enhancement effect from NipsIt as any other seed treatment insecticide available,” says Rotariu.

NipsIt is available through seed company partners, seed plants, as well as through all retail distribution channels for on-farm treatment. “We’re asking farmers to give their seed the best possible chance for success with effective seed treatment,” says Rotariu. “And with NipsIt, growers aren’t tied to specific herbicide purchases for a better price. I encourage growers to put NipsIt to the test alongside any other seed treatment this season. Just try it and let the results speak for themselves.”

For more information on new NipsIt Suite seed treatment, visit Nufarm.ca.

Always read and follow label directions. NIpsIt™ is a trademark of Nufarm Agriculture Inc.

Getting the seeds in the ground at the optimum time is just one part of the seeding decision. The number of seeds required per acre is another. Again, Labrie suggests that input costs should be the guiding factor. His calculations from research trials on the economics of seeding rates show that a planting rate of 182,200 seeds per acre (450,000 seeds per hectare) produced income of $676.11 per acre. With soy selling at $9.24 per bushel and seed costs of $57 per 140,000 seeds, increasing the seeding rate to 222,700 seeds per acre only increased income by $8.10 per acre while cost of the extra seeds was roughly $17.

Labrie says that when projected yields don’t support higher input costs, increasing the amount of seed per acre isn’t a viable

option for the grower. He says a more cost effective method of increasing yields and decreasing weeds, which compete for soil nutrients and require herbicide applications, is proper placement of the soybean seeds in the field.

Because the natural canopy created by well-spaced soybean plants deters weed growth, Labrie advocates spacing rows 15 inches apart. He says crop trials indicate 15-inch rows form an effective canopy 15 days later than seven- or eight-inch rows, but 25 days sooner than a 30-inch row. Thirty-inch rows provide less protection for soil and allow late emerging weeds to fill in. Rows spaced 15 inches apart reduce weed growth, promote soybean trifoliolate growth through better light efficiency and reduce the incidence of mould because they provide more space for air

movement between the plants than seven-inch rows.

Labrie says twin row planting, two rows eight inches apart with a 22-inch row between each set of eight-inch rows, produce higher yields, enough to pay for the custom seeding costs. And, he adds, navigating the field to apply insecticides or fungicides is much easier with 22-inch rows than it is with either seven- or 15-inch rows.

Planting seeds too close together within 30-inch rows won’t improve yields either, according to Labrie. It only increases the opportunity for white mould to develop in the crop. And he has some advice about seed placement within any row: “I would say up to 15 inches for spacing at one inch deep.”

Research plays a major role in the development of soybean crops in North America. Labrie, who has been a corn and soybean specialist since 2010, developing the Elite line of soybean seeds, says his job is to provide knowledge and support to the coop

network sales representative. His work includes finding ways “to increase corn and soybean yield through fertilization, seeding date, seeding rate, crop protection and the use of cover crops.”

Soybeans have their genetic origins in Asia, and through the process of natural selection have developed and adapted to North American climate zones. Developing plant genetics is a long process and soybeans take longer to develop than some other crops. Labrie says, “It takes at least eight years to develop a new soybean variety.” And yield increases within varieties take even longer. He says it took 87 years to attain an increase of .38 bushels per acre while corn yields have been increasing at 1.5 per cent annually.

“The soybean yield will increase, but it’s a long process,” he says.

For more on soybean agronomy, visit www.topcropmanager.com. Varro® herbicide for wheat. Freedom from Group 1 herbicide resistance. Freedom to select your preferred broadleaf partner. Freedom to re-crop back to sensitive crops like lentils.

To learn more about Varro, visit: BayerCropScience.ca/Varro

Researchers assess efficacy, rates and timing of pyroxasulfone for herbicide-resistant weeds in field pea.

by Donna Fleury

Growers will soon have access to a new weed management tool for field pea and other crops. Pyroxasulfone is a new molecule that provides broad-spectrum control of many grass and broadleaf weeds when soil-applied pre-plant or pre-emergence. This new mode of action is a Group 15 herbicide, with activity on some of the common resistant weed biotypes in Canada such as wild oat and cleavers, both Group 2-resistant weeds.

“Researchers at the at the University of Alberta, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatchewan and the University of Saskatchewan have been leading various research trials with pyroxasulfone and weed control in crops such as pulses and winter wheat,” Breanne Tidemann, a PhD candidate at the University of Alberta, explains. “In two of our recently completed projects, we were evaluating the efficacy, timing and use rates of pyroxasulfone and combinations for herbicide resistant weeds in field pea.”

Pyroxasulfone is a soil-applied herbicide and as a result can be affected by organic matter levels, soil moisture and other soil

factors. Pyroxasulfone is a relatively unique mode of action in the Canadian Prairies, “which could really help our growers with weed control and in particular herbicide resistant weeds in peas,” Tidemann notes.

One study was initiated in the fall of 2011 at five sites in Alberta and Saskatchewan with a wide range of soil types and organic matter levels. The objectives of the study were to evaluate the potential of pyroxasulfone to control acetolactate synthase (ALS) inhibitor-resistant weeds in field pea, and determine the effect of soil organic matter content on the efficacy of pyroxasulfone on cleavers and wild oat or on the tolerance of field pea. Researchers also compared the efficacy of fall and spring application to determine which application timing provided the greatest weed control and least crop injury.

In the study, pyroxasulfone was applied in split-plot trials at five locations including Scott, Kernen and Melfort, Sask., and Ellerslie

ABOVE: Pyroxasulfone symptoms on wild oat at Scott, Sask.

Tough broadleaves and flushing grassy weeds have met their match. No burndown product is more ruthless against problem weeds in spring wheat than new INFERNO™ DUO. Two active ingredients working together with glyphosate get hard-to-kill weeds like dandelion, hawk’s beard, foxtail barley and Roundup Ready® canola, while giving you longer-lasting residual control of grassy weeds like green foxtail and up to two weeks for wild oats. INFERNO DUO. It takes burndown to the next level.

INFERNO DUO is now eligible for AIR MILES® reward miles through the Arysta LifeScience Rewards Program in Western Canada.

Go to www.arystalifesciencerewards.ca for program details and learn how you can earn 100 bonus AIR MILES® reward miles.

1. Wild oat ED50 values at each trial location and application timing, (fit to a linear model [y1⁄4mxþb]) against soil organic matter at the respective locations

Source: Tidemann et al.: Pyroxasulfone in field pea. Weed Technology 28, April–June 2014.

and Kinsella, Alta., ranging in soil organic matter (OM) content from 2.9 to 10.6 per cent. Fall and PRE spring applications were made at each site comparing rates of 0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 300 and 400 g ai/ha of pyroxasulfone and an application of Viper as an industry standard.

“The study did not find any consistent differences in timing; both fall and spring applications were effective,” Tidemann says. “However, both weed efficacy of pyroxasulfone and pea crop tolerance were affected by trial location, particularly the soil organic matter content and soil moisture. With wild oat, efficacy started at lower rates, but results were variable, with around 80 per cent control achieved at the average top level. Cleavers could be controlled 100 per cent, with rates depending on location and organic matter.”

At Kernen and Scott, significant yield reductions and pea injury occurred at 150 and 100 g ai/ha and higher. However, this was a result of these sites receiving about 200 per cent of their normal moisture. Low organic matter and high precipitation levels at these locations caused higher than normal herbicide activity under these conditions, and injury is not expected under more normal growing conditions. No injury has been observed in other sites or trials with this product. Overall, the research showed that pyroxasulfone may allow control of ALS inhibitor-resistant false cleavers and wild oat. However, locations with high soil organic matter (>~seven per cent) will require higher rates than those with low organic matter for similar control levels.

In a second study, using both greenhouse and field trials, researchers examined the efficacy of pyroxasulfone and sulfentrazone (a Group 14 herbicide) tank-mix combinations, and the impact of soil organic matter content. Field trials were conducted over six site-years in 2011 and 2012 across Western Canada to examine the interaction of pyroxasulfone and sulfentrazone when co- applied for control of false cleavers and wild oat in field pea. This interaction was further investigated in the greenhouse for these two weed

species, plus barley and canola. In a separate experiment, the effect of OM content on pyroxasulfone and sulfentrazone efficacy was examined using three soils with 2.8, 5.5 and 12.3 per cent OM content, respectively.

“The results showed that the efficacy of pyroxasulfone and sulfentrazone combinations was additive under both field and greenhouse conditions,” Tidemann says. “With different weed spectrums, a co-application of these two products can broaden the spectrum of weeds controlled in field pea. Again, higher OM content generally required higher rates of herbicide to achieve similar efficacy for all tested species.”

Pyroxasulfone and sulfentrazone can be combined to aid in herbicide resistance management and broaden the weed spectrum compared with each product used alone, although rate selection may be OM dependent. Use of these herbicides adds infrequently used modes of action to crop rotations and can aid in proactive or reactive management of herbicide-resistant weeds. However, integrated weed management and responsible use of these herbicides is necessary to maintain their effectiveness in Western Canada.

Registration for field pea and other crops by 2016

Pyroxasulfone was registered in Canada for use in field corn and soybeans in 2014, and other crops including field peas are expected to be added to the list fairly soon.

“The registered product for corn and soybeans is available as Focus herbicide, which is a co-pack of Pyroxasulfone 85 WG and Aim EC, a Group 14 product,” Mitch Long, product development manager with FMC of Canada in Saskatoon, Sask. explains. “Focus, which can be applied pre-plant or pre-emergence alone or in a tank mix with glyphosate, provides grassy and broadleaf weed activity. Focus and glyphosate can be applied prior to planting or within three days of planting to control any emerged weeds and to set up the crop for residual control with pyroxasulfone.”

The product is applied to the soil surface and does require onehalf inch of moisture to move the product into the soil for control. It does have activity on some of the common resistant weed biotypes in Canada, such as wild oats and cleavers, Group 2 resistance and for Group 9 glyphosate resistance.

FMC conducted large-scale field trials in Canada in 2014 on corn and soybeans, with positive results. “For growers, the real advantage is the setup treatment with the burnoff and the residual activity of pyroxasulfone, which provides a weed-free environment for germination and establishment of corn or soybeans,” Long notes. “Depending on the rate used, the residual control can last up to eight weeks or longer, and then an in-crop herbicide application can be made if needed. The fact that the pyroxasulfone can be applied with a burnoff treatment in the spring saves labour and provides early weed control. If spring rains delay in-crop application, there is already some weed control in place.”

FMC has also applied for registration of pyroxasulfone products in spring and winter wheat and lentils, which are expected to be approved for the 2016 growing season. Durum wheat will not be included. “We are submitting the product for registration in field peas, flax and chickpeas, and expect approval for the 2017 growing season,” Long says. “This product will be a pre-formulated mix of Pyroxasulfone 85 WG and Authority. This new mode of action Group 14 and 15 herbicide brings to growers a new set of weed management tools for crop management.”

The Rocky Mountain Equipment AG Optimization Specialist (AOS) Team understands equipment performance, technology and precision AG because they are specialists. More than any other retailer, RME treats precision agriculture, equipment performance and technology as a specialized discipline.

This is sophisticated equipment; delivering the best possible advice, training and support demands support and service specialists who receive superior and ongoing training. Visit one of our 32 AG dealerships across Western Canada and talk to the AOS team about your precision AG solution needs.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN EQUIPMENT DEPENDABLE IS WHAT WE DO.

An unlikely weed in an unexpected location.

by Donna Fleury

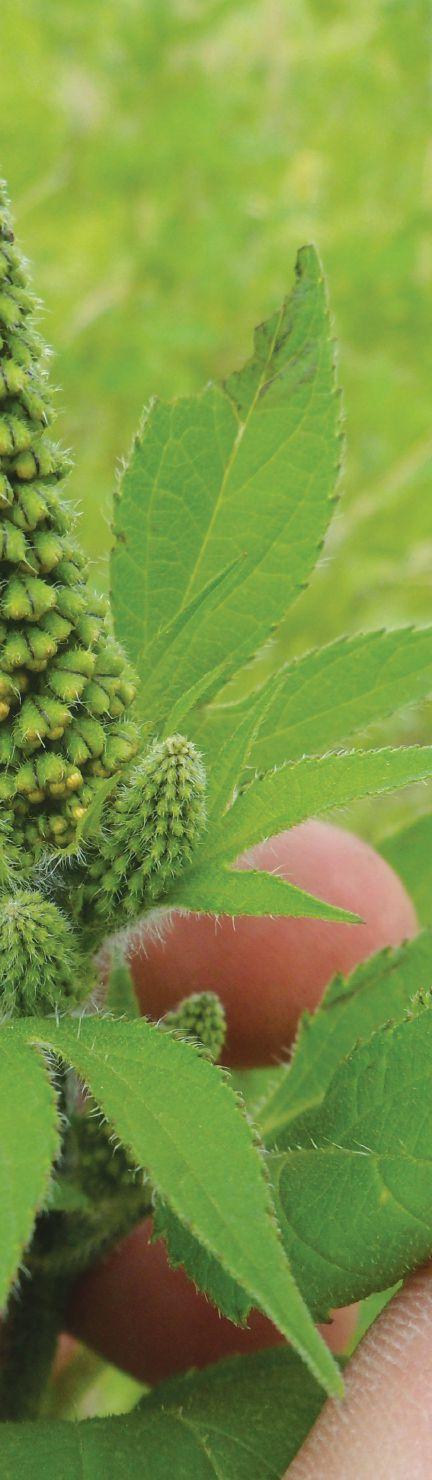

Aweed more common to warmer climates in the United States and a few places in southern Ontario and Quebec — giant ragweed — made an unorthodox appearance in southwestern Manitoba in 2012. A few random metre-high plants showed up in research plots — a very unexpected sight.

“We were surprised to even find giant ragweed this far west in Manitoba,” Scott Chalmers, diversification specialist with Manitoba Agriculture Food and Rural Development (MAFRD) says. “Giant ragweed can occasionally be found in southeastern Manitoba along ditches around Morris or Steinbach, but this far into the southwest region is unexpected. This weed has primarily been a problem in the southern U.S. but has moved into places like North Dakota along the Red River. We expect this Manitoba population may have come from seeds that had floated north [from the States] during the 2011 flood along the Souris River.””

Giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida) is an annual plant in the aster family and native to many places across North America. Giant ragweed reproduces from seed, is wind pollinated and can grow up to six metres under the right conditions, although two to three metres is more typical. In many places in the U.S., giant ragweed has become a super weed resistant to glyphosate. And in 2008, giant ragweed was the first glyphosate-resistant weed confirmed in Ontario. Its smaller relative, common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), is a widespread, annual weed across North America, and herbicide resistant populations have also been reported, including glyphosate resistance in Ontario in 2011.

“The first patch of giant ragweed showed up in 2012 randomly in one of our plots, and was also found within the rest of the field locally,” Chalmers explains. “In 2013, Melita [Manitoba] experienced another minor flood along the Souris River and many acres in the valley were not planted. We found even more plants in the same field, but generally there were, on average, a couple plants per acre. We conducted glyphosate tolerance tests in the field (in vivo) on the few plants that were growing there, comparing different application rates.”

Overall, the glyphosate treatments did inflict severe damage on the plants, although in some plants, the seed-containing raceme did appear to survive while all leaves had browned off. One plant required a second application using a tank mix for full control.

“In 2014, we continued to monitor the population in our plots as well as a larger patch discovered further upstream,” Chalmers says. “About two weeks after the producer sprayed the patch with glyphosate, we noticed that quite a few of the plants stayed green. We worked with the producer to closely monitor the patch and discovered common ragweed as well. This patch had two bad weeds in the same place at the same time, both notorious for glyphosate resistance. There was considerable variation in the control of both common and giant ragweed plants, ranging from completely dead to completely

<LEFT: Variations of common (left) and giant (right) ragweeds response to a glyphosate application. Green variants may suggest there are some tolerance levels, which may suggest some resistance.

alive and all sizes as well. This is characteristic of glyphosate resistance, so we took seed samples from dead plants and those that survived for testing from both species.”

Chalmers is working with University of Manitoba weed scientist Rob Gulden, who has sent the seeds to Ontario for resistance testing.

“With the recent flooding and excess moisture, we are getting cycles of weeds and weed seed banks that we don’t normally have to deal with,” Chalmers explains. “In North Dakota, common crop rotations of winter wheat, corn and soybeans may encourage weeds like giant ragweed, which can easily spread by seed through flooding events. As climate change potentially increases our temperatures to more what North Dakota has, these types of weed issues may creep north along with these crops. With cropping practices, increased precipitation, climate change and flooding concerns, it is almost like a perfect storm of pressure for weed problems like giant ragweed. So far our colder climate and more diverse crop rotations in Manitoba have reduced the risk of larger populations of giant ragweed spreading quickly.”

Giant ragweed has a large seed, similar in size to a wheat kernel. The seeds have two main strategies for reproduction. Seeds that remain on the soil surface can germinate within a few weeks in the same year or in the following spring. Seeds that get buried in the soil typically remain dormant for a year and germinate the next. Seeds can remain viable for several years.

“These strategies may be a product of glyphosate resistance in ragweeds adapting to current agricultural practices,” Chalmers says. “Those seeds that germinate early are banking on a continuous rotation of glyphosate-tolerant crops, whereas those that skip a year or two might be banking on wheat (for example) that would have herbicides that would have controlled or suppressed the glyphosate-resistant ragweeds.”

Producers in western Manitoba are encouraged to maintain fields with a diverse crop and herbicide rotation. Many other weed species exist in Manitoba with various levels of resistance to other herbicides such as Group 1 or 2 herbicides, some with multiple forms of resistance. Tank mixes of different chemical groups are a more effective way than increasing rates of a single chemical. Hand pulling small patches of suspected resistance is always the best control option. Use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) could prove beneficial in identifying these smaller patches, reducing overuse of herbicides.

“We will continue to monitor the river flats where there are more plants than usual including giant ragweed,” Chalmers says. “I think giant ragweed will be a slow advancing problem in our area because we tend to grow many other crops with a broad mix of herbicides and are not as reliant on just soybeans, corn and winter wheat. However, we are also concerned about the potential of glyphosate-resistant kochia that is well suited to our area and may also have moved into our area as a result of the flooding.

“Everyone is encouraged to be vigilant and monitor weed patches closely so any resistance concerns can be managed quickly and reduce the risk of widespread problems,” he adds. “Weeds like giant ragweed and others are likely here to stay.”

Managing volunteer canola is an increasing priority for producers.

by Donna Fleury

Volunteer canola is becoming a bigger weed management challenge for canola growers, particularly where high frequency rotations are in place. Recent weed surveys in Saskatchewan show volunteer canola has moved up on the list of most common weeds, from the low 30s in the 1980s to number 14 and higher today.

“Volunteer canola can be problematic for canola growers even though we don’t always think of it as a true weed,” Christian Willenborg, assistant professor with the department of plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan says. “Volunteer canola creates a lot of risk and negative issues, even in a canola crop itself.”