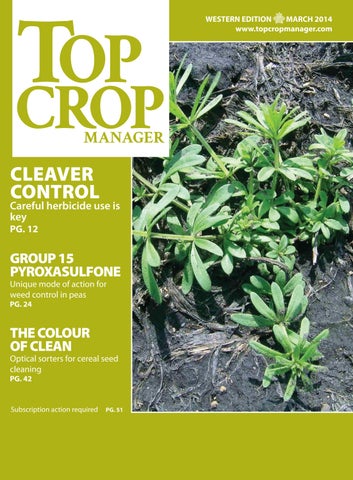

TOP CROP MANAGER

CLEAVER CONTROL

Careful herbicide use is key

Unique mode of action for weed control in peas

PG. 24

THE COLOUR OF CLEAN

Optical sorters for cereal seed cleaning

PG. 42

Careful herbicide use is key

Unique mode of action for weed control in peas

PG. 24

Optical sorters for cereal seed cleaning

PG. 42

18 | A new weed threat on Manitoba’s doorstep glyphosate-resistant waterhemp is moving north along the red river Valley.

Carolyn King

30 | Slow-release ESN for sunflowers eSn can replace a second top dress application

Donna Fleury

48 | Adding longevity to soil health a new study shows that growing potatoes in rotation without conservation management practices dramatically reduces yields long-term.

Julienne Isaacs

Tile drainage comes to central

Donna Fleury

The colour of clean

one woman’s flower is another man’s weed

Janet Kanters

Janet Kanters | eDItOr

From a young age, I’ve been fascinated by plants. Well, maybe I should rephrase that – I’m fascinated by seeds. Seeds, that when you put them into soil, grow into plants. Usually without fail. a miracle really.

From the time I could walk, I would follow my parents around our property, “helping” them plant the vegetable garden, the flowers and the bulbs. My Dad was the big gardener in our family –with my folks being Dutch, I guess it was meant to be – and I learned early on about the importance of weed control. He told me often that weeds compete for the beneficial plant’s resources – food and water – that come from the soil. growing up, I believed his strict attention to weed control was simply a make-work project for us kids. But over the past 20 years as an agriculture journalist, I’ve come to realize Dad was right all along.

Today, no weed is safe from my Dutch hoe, or from the odd spritz of herbicide. But the business of weed control is hard work. and I’m continually learning new things. For example, that toadflax (Linaria vulgaris)and Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) are classified as noxious weeds here in alberta. Whoops! Thanks to a city friend, the Himalayan Balsam plants are covering one side of my home. They are very pretty, but when their seedpods “burst” in late summer, the seeds shoot out 40 feet or more. The upside is the flower… er, weed… is easy to control when young, before seedpods ripen. over the past two years, I’ve simply pulled the plants out of the ground and burned them in the burning barrel.

Toadflax has been a little harder to control. I won’t take the blame for it being in one of my flowerbeds: it was the people who lived on this property before me who planted it. nonetheless, it has proven to be a real tough weed to get rid of. pulling it up just doesn’t work that well. and I hesitate to use herbicides because of surrounding shrubbery and other flower species. But, with consistent weeding, I’m winning this battle as well.

Farmers in Western Canada know all too well the challenges of weed control. Indeed, herbicide resistance is increasing across Canada, with group 2 herbicide resistance becoming very common. according to Breanne Tidemann, a graduate student at the University of alberta, recent research from agriculture and agri-Food Canada estimates that 29 per cent of annually cropped land in Canada is occupied by herbicide resistant weeds. Tidemann’s work at the U of a is featured in a story about researchers who are testing a new mode of action that could provide another weed management tool for growers. Tidemann is working with researchers at the University of alberta, agriculture and agri-Food Canada in Saskatchewan and the University of Saskatchewan who are leading various research trials with pyroxasulfone and weed control in crops such as pulses and winter wheat. read more about this exciting discovery on page 24. also in this issue, we feature several stories on weeds and weed control, including a new weed threat in Manitoba (page 18), controlling cleavers (page 12) and a list of new herbicide products for prairie growers (page 16). This issue also includes our annual Weed Control guide, which lists herbicide products and tank-mix ratings for grassy, broadleaf and perennial weeds, and volunteer crops. This year, we’ve included two new crops – corn and soybeans. With steadily climbing acres in both those crops on the prairies, we hope you’ll find these new sections helpful when choosing your weed control plan for 2014. as for me, I will continue to do my own research on noxious weeds, and the threat they pose to the canola and wheat fields that border my property. and I will do everything I can to eradicate them from my flowerbeds. In the meantime, I’ve started some new flower and vegetable seeds indoors. It’s wonderful to see the first small shoots of green poking above the soil, all the while the snow continuing to swirl outside. Soon enough, we’ll all be outdoors tilling the earth, ready for a new growing season.

MARCH 2014, vol. 40, no. 5 EDIToR Janet Kanters • 403.499.9754 jkanters@annexweb.com WESTERn FIElD EDIToR Bruce Barker • 403.949.0070 bruce@haywirecreative.ca DIGITAl EDIToR – AgAnnex Lianne Appleby • 226-971-2133 lappleby@annexweb.com

EASTERn SAlES MAnAGER Steve McCabe • 519.400.0332 smccabe@annexweb.com

mfredericks@annexweb.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710 RETuRn unDElIvERAblE CAnADIAn ADDRESSES To CIRCulATIon DEPT. P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 subscribe@topcropmanager.com Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

CIRCulATIon e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SubSCRIPTIon RATES

Top Crop Manager West 9 issues February, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, october, november, December 1 Year $45 Cdn plus tax

Top Crop Manager East 7 issues February, March, April, September, october, november, December 1 Year $45 Cdn plus tax

Potatoes in Canada 4 issues Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter 1 Year $16.00 Cdn plus tax

All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry-

www.topcropmanager.com

It’s rare to find a herbicide you can count on for long-lasting stopping power that’s also safe on wheat. The advanced safener technology in EVEREST® 2.0 makes it super selective for best-in-class crop safety. Safe on wheat, it’s also relentless on weeds, giving you Flush-after-flush ™ control of green foxtail, wild oats and other resistant weeds. And a wide window for application means you can apply at your earliest convenience. It’s time you upgraded your weed control program to the next generation: EVEREST 2.0. To learn more, visit everest2-0.ca.

Diverse crop rotations significantly reduce wild oat, herbicide inputs and resistance risk.

by Donna Fleury

In cropping systems across the prairies, wild oat control and concerns of herbicide resistance continue to challenge many growers. Current annual cropping systems are increasing the selection pressure for wild oat resistance, which is rapidly expanding across the prairies. In alberta alone, more than 50 per cent of all wild oat populations have at least group 1 resistance and some have other herbicide resistance as well.

In 2010, Dr. neil Harker, research scientist with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) at Lacombe, alta., initiated a five-year project to evaluate management strategies to reduce selection pressure for wild oat resistance to herbicides. “The objective was to look at cropping systems and cultural management methods that could reduce our reliance on wild oat herbicides,” explains Harker. “Similar to previous studies, we included cultural practices such as higher seeding rates and silaging to prevent wild oat from going to seed. However, in this study we added a new strategy of including different crop life cycles to determine if diverse crop rotations would influence wild oat production, wild oat seed bank, soil microbes, crop yield and crop quality.”

previous studies included only summer annual crops such as barley, wheat, canola and peas. Wild oat is also a summer annual weed, so continually growing summer annual crops favours wild oat growth. In this study, researchers added different crops including alfalfa (perennial) and winter annual crops such as winter wheat, winter triticale and fall rye. In the years these latter crops were grown, no herbicides were used for wild oat control. The project was conducted at eight sites across Canada, including Lacombe, Lethbridge and edmonton, alta.; Scott and Saskatoon, Sask.; Winnipeg, Man.; new Liskeard, ont.; and normandin, Que.

at the start of the project in 2010, wild oat populations were established in canola in all locations. natural wild oat populations were supplemented to ensure adequate, uniform wild oat populations for the study. Crops included canola, alfalfa, early-cut barley silage, winter triticale, fall rye, peas, winter wheat and wheat in various rotations (see

ABOVE: Alfalfa in rotation provided the same level of wild oat control as an annual crop with herbicide control.

We know the value of cold weather germination. We have to. It’s Canada.

Creating a seed treatment that can withstand this country’s unpredictable elements was no accident. Like you and your operation, Insure™ Cereal was built in Canada. Of course increased emergence in cool germination conditions is just one of this innovative seed treatment’s advantages. It also delivers more emerged seedlings, a more consistent plant stand, increased root biomass and larger shoot systems. They’re all part of the unique bene ts* we call AgCelence®. And Insure Cereal is the only cereal seed treatment that has them. For details, visit agsolutions.ca/insure or call AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273).

*AgCelence bene ts refer to products that contain the active ingredient pyraclostrobin. Always read and follow label directions.

AgSolutions is

Table 1). Seeding rates in cereals were usually double the normal rate. Wild oat herbicides rates were 0, 50 or 100 per cent, while broadleaf weeds were treated with full herbicide rates. Wild oat density and biomass, crop density, yields, and biomass were collected each year.

“For the alfalfa, early silage and winter annual crops treatments, no wild oat herbicides were used for the three years from 2011 through 2013,” explains Harker. “For those three years, there is essentially zero selection pressure for wild oat herbicides. all of the experiments will continue through to the end of the 2014 crop year, with canola being grown in every location to provide a good comparison of what has happened over the five years of the study. So although we don’t have final results yet, the preliminary findings are very encouraging.”

preliminary results show that most plots with alfalfa, or silage and winter annual crops – and no wild oat herbicides – had wild oat biomass similar to the canola-wheat check rotation with 100 per cent wild oat herbicide every year. at the end of 2014, the final data collection will be completed including a wild oat seed bank determination to see whether or not the levels have changed over the five years of the study.

“We expect the final results to be similar to the preliminary findings and are encouraged to see that the results from some diverse rotations in integrated systems without wild oat herbicides can be as effective at managing wild oat as a typical summer annual canola-wheat rotation with full herbicide-rate regimes,” says Harker. “The results will provide growers with options to reduce herbicide expenditures, reduce selection pressure for weed resistance, and to grow canola in more sustainable rotations.”

However, the challenge is that few growers are willing to include more diverse rotations in their cropping systems. They have to weigh the short-term gain of a canola-wheat rotation, for example, with the long-term delay in herbicide resistance of more diverse rotations. growing dominantly summer annual crops over and over again puts pressure on summer annual weeds, which are more likely to become resistant to whatever herbicide is being used. adding diversity to the system can help reduce the selection pressure for herbicide resistance and delay the development of resistance.

Table 1. Rotation treatments for the experiment. Some rotations were duplicated with varying crop seeding (1x or 2x) and/or herbicide rates (0%, 50% or 100%).

LL Canola Barley LL Canola Barley

LL Canola Barley Peas Wheat

LL Canola Early Silage Early Silage Winter Wheat RR Canola

LL Canola Early Silage Early Silage Wheat

LL Canola Early Silage Winter wheat Winter Triticale

Canola

Canola

LL Canola Early Silage Winter wheat Barley RR Canola

LL Canola Early Silage Winter Triticale Early Sialage

Canola

LL Canola Fall Rye Peas Winter Triticale RR Canola

LL Canola Early Silage Peas Winter Triticale RR Canola

LL Canola Alfalfa Alfalfa Alfalfa RR Canola

LL Canola Chem fallow Fall Rye Chem fallow RR Canola

Source: Harker, AAFC.

Harker emphasizes that growers and industry need to think about other management options to reduce selection pressure now as the risk of herbicide resistance increases. “along with wild oat herbicide resistance, other concerns such as kochia resistance to glyphosate in the west and three other glyphosate-resistant weeds in the east, need to be addressed. We must act now to delay the selection of

sate resistance in a species that threatens Canadian agriculture even more than kochia – wild oat.”

For more on weed management, visit the agronomy section at www.topcropmanager.com.

10-section automatic overlap control that saves money by eliminating double seed and fertilizer application.

Gentle metering and distribution that lets me reduce seeding rates while maintaining target plant populations.

Hydraulic, ground-following openers that give me uniform seed and fertilizer placement, excellent emergence, strong growth and even maturity.

Stress-free, in-cab automatic calibration that’s based on actual product usage thanks to weigh cells on each tank and a user-friendly monitor.

Knowledgeable support staff who can trouble-shoot remotely via my in-cab monitor while I am in the field.

To apply granular fertilizer at rates of up to 400 lbs/acre on my 100’ drill with no plugging.

Variable rate capability for up to five products at one time.

A ruggedly reliable system that can seed thousands of acres with no breakdowns and minimal maintenance.

A light-pulling drill with a lift-kit that seeds through muddy fields without getting stuck.

“Zone Command saves me about $57,000 per year or 5% of my input costs on dry years and probably twice that in wet years. I wouldn’t farm without it.”

SeedMaster gives me all of this in one seeding system with advanced technologies that make money for my farm –like Auto Zone Command™, Auto Calibration™, the UltraPro Canola Meter™, the Nova Smart Cart™, and SafeSeed Individual Row Metering™

SeedMaster’s cost savings and efficiencies are the new normal on my farm.

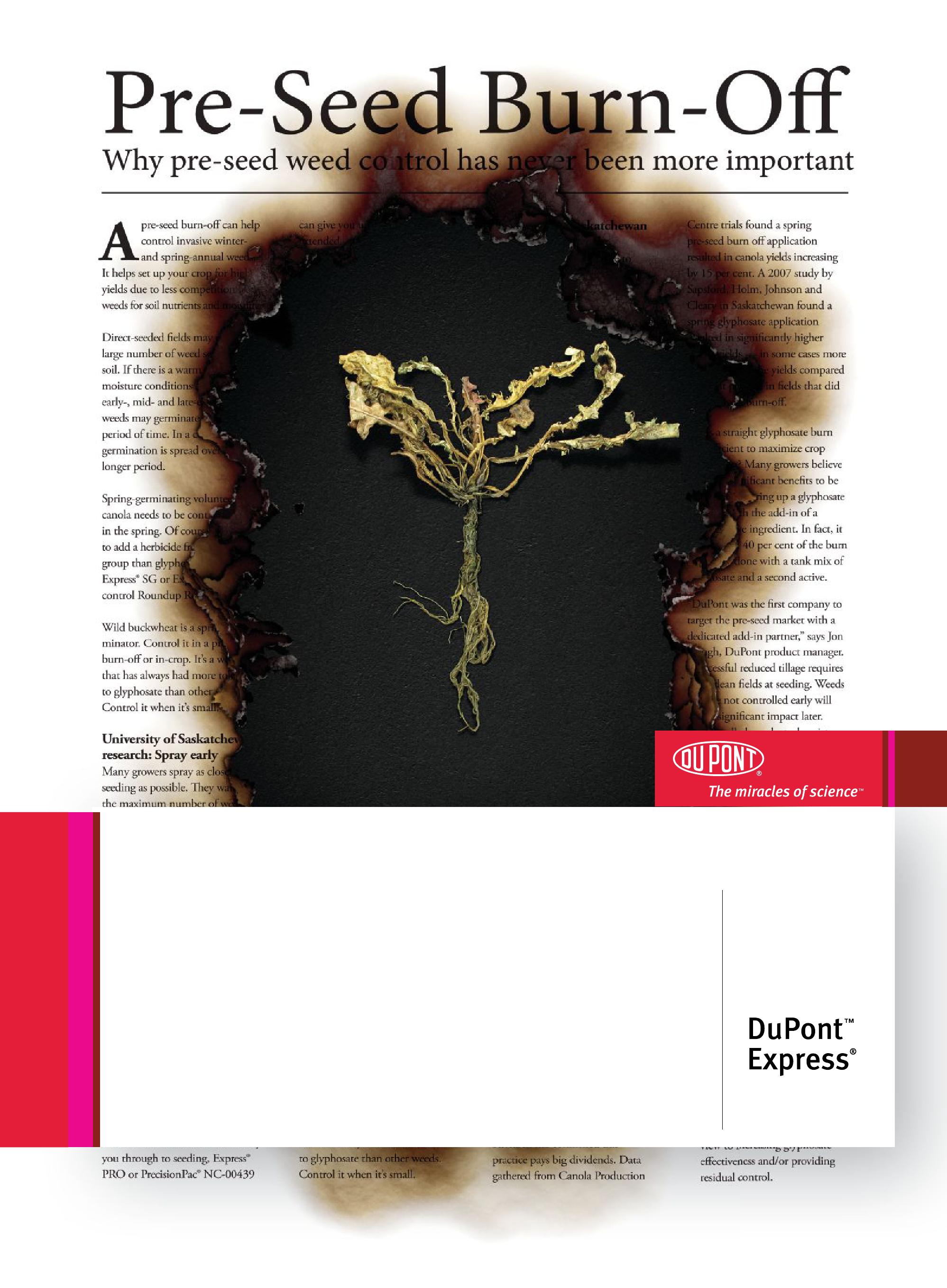

Crank up the rate all you want, glyphosate alone still misses a number of hard-to-kill weeds like narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard, ixweed, stinkweed, dandelion and volunteer canola. With hotter-than-hot systemic activity, DuPont™ Express® herbicides don’t just control weeds, they smoke them from the inside out, getting right to the root of your toughest weed challenges with performance that glyphosate alone can’t match. It’s no wonder Express® goes down with glyphosate more than any other brand in Western Canada!

Visit expressvideo.dupont.ca to see Express® in action – torching tough weeds like dandelion and volunteer canola right down to the roots, so they can’t grow back.

Express® brand herbicides. is is going to be hot.

Questions? Ask your retailer, call 1-800-667-3925 or visit express.dupont.ca

rairie farmers depend on glyphosate for agronomic practices such as pre-seed, chemfallow and post-harvest herbicide applications. Recent years, however, have seen an increase in documented cases of weed resistance, with glyphosate a key concern. What can growers do?

Weeds become resistant when they’ve had too much of a good thing. Practices that work well one year become less e ective over time, if there’s no break in routine.

For example, glyphosate alone will not control glyphosate-resistant kochia and may increase the risk of glyphosate resistance occurring in other weed species. Faced with Roundup Ready® volunteers and hardto-kill weeds not controlled by glyphosate alone, growers have found that adding in DuPont™ Express® brand herbicides helps control these weeds and manage the threat of resistance.

EFFECTIVE NON-CROP USE OF GROUP 2 HERBICIDES

Group 2 herbicides are a highly e ective tool to control weeds. Like other herbicide groups, they should be mixed with herbicides from other groups in the same spray to manage resistance.

For pre-seed weed control, DuPont scientists recommend a pre-seed burn-o treatment of Express® (Group 2) or PrecisionPac® NC-00439 or NC-0050 (Group 2) with glyphosate (Group 9). is is particularly e ective if the crop rotation includes a crop such as Roundup Ready® canola and weeds that are not e ectively controlled by glyphosate alone.

Because Group 2 and Group 9 herbicides have activity on many of the same weeds, growers get multiple modes of action working for them. In certain situations, adding a third mode of action such as dicamba, 2,4-D or MCPA (Group 4) may be advisable when there are weeds resistant to multiple groups.

Crop rotation and complementary weed control

A eld should have a rotation of at least three crop types. Consider also weed control methods such as higher seeding rates, planting clean seed, mowing out suspected resistant weed patches before they go to seed and using herbicides according to label directions.

Herbicides are categorized into 17 groups, based on how they target a weed. For example, Sulfonylurea (Group 2) herbicides control weeds by inhibiting an enzyme essential to their growth.

Express® brand herbicides signi cantly improve control of tough weeds such as narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard, ixweed, stinkweed, dandelion and volunteer canola, compared to glyphosate alone. is approach also helps proactively manage weed resistance.

DuPont Crop Protection is working with growers and retailers to protect the use of all the best crop protection tools available. As growers seek ways to manage weed resistance while maintaining pro table crop protection, DuPont is with you all the way.

“If at all possible, producers should use mixtures of herbicides that use multiple modes of action in the seeding year,” says Ken Sapsford, University of Saskatchewan. “It’s one further step to help stop resistance from developing.”

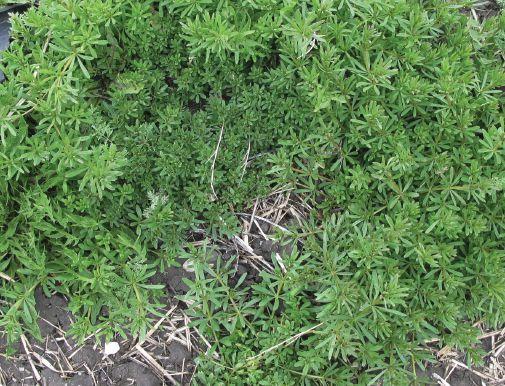

Cleaver populations are on the rise across the Prairies, but management is possible with judicious use of herbicides.

by Julienne Isaacs

Cleavers is an annual or winter annual weed that reproduces through seed. While the weed is native to temperate regions around the world and affects most field crops, it has become more of a problem in Canada’s prairie regions over the last few years.

according to Chris neeser, a weed specialist with the pest surveillance branch of alberta agriculture and rural Development, cleavers is becoming increasingly troublesome in cereals and canola largely because of the trend toward zero-till. Traditionally rooted out with cultivators, the trailing weed is now enabled to develop populations that germinate in the fall and overwinter in a vegetative state, resuming growth early in the spring.

“What we have as a result is, increasingly, cleavers that have a competitive advantage over crops that germinate in the spring. Those cleavers that are more advanced are more likely to survive herbicide applications,” says neeser.

Cleavers can cause problems at almost every stage of crop development. early on, winter annual cleavers are competitive with field crop seedlings; later, cleavers causes significant crop losses. Cleavers can get tangled up in harvesters. also, cleavers seed is similar in size and shape to canola seed, and once canola seed has been contaminated with cleavers seed it’s virtually impossible to separate.

In 2010, Canada’s annual weed survey, which is done in sequence province by province, took place in alberta. among the top 20 weed species affecting dryland crops, ranked according to frequency, uniformity and density, cleavers placed third, after wild buckwheat and wild oats. although these are the newest statistics for alberta, neeser says growers have been reporting increased numbers of cleavers since 2010, likely because of humid weather conditions. “If we have a moist spring and then sufficient rainfall through the summer and fall, there’s a good chance that cleavers will be doing well,” says neeser.

In 2012’s weed survey of canola fields in Saskatchewan’s aspen parkland ecoregion, cleavers ranked fourth in relative abundance, after green foxtail, wild buckwheat and wild oats.

according to nasir Shaikh, a provincial weed specialist with Manitoba agriculture, Food and rural Development (MaFrD), the cleavers situation is worsening eastwards from southern Saskatchewan. “The situation is bad on the western side of the province right now. We don’t have much incidence of cleavers in the red river Valley or on the eastern side. But it is moving eastwards, so it’s a matter of time,” he says.

A flowering stem with immature seeds. A single cleavers plant can produce 3,500 seeds.

Management strategies

according to Shaikh, a key management approach is to tackle cleavers early in the season, when growers are buying seed. growers planting canola should be especially vigilant.

“The biggest concern I have regarding cleavers is that it can contaminate canola seed, and this can reduce the quality of the produce, the seed and the grain,” he says. “It’s very difficult to separate canola seed from cleavers. The best way to prevent this is to use the best

quality seed, certified or pedigreed seed, with almost zero per cent cleavers.”

growers should plant where possible in well-drained fields, as cleavers prefers damp, moist conditions. prior to planting, a pre-seed burndown will take care of the overwintering cleavers, says Shaikh.

neeser’s message concerns herbicide resistance. With group 2 resistance noted in all three prairie provinces, growers’ chief concern should be avoiding the emergence of resistant cleavers populations.

“We have quite a bit of aLS (group 2) resistance in alberta. In 2007, 17 per cent of the sample of cleavers that was surveyed was resistant to group 2 class herbicides,” he says.

He strongly emphasizes the importance of rotating herbicides between crops, and avoiding use of the same group from one crop to the next. It’s crucial that growers pay attention to the active ingredients in their herbicides.

Secondly, but no less importantly, neeser recommends using herbicide mixes that include more than one herbicide group, and preferably multiple groups.

neeser says growers should ensure that group 2 canola, such as

roundup ready canola, is not planted year after year. “given that so much roundup is used already, you have to use it carefully. Don’t always just use roundup ready canola. If you do use it, make sure that in your subsequent crops, roundup ready canola isn’t the mainstay of your weed control. That’s important,” he says.

In general, crop rotation is a strong option for growers facing cleavers problems. For growers who have a market for them, perennial crops such as alfalfa are excellent options for getting rid of cleavers, says neeser. “Cleaver seed doesn’t live that long in the soil – three years is pretty much the maximum. If you need to clean up a field, planting alfalfa, or any type of forage crop, is an excellent option.

But the best management strategy, neeser claims, is to ensure resistant populations are not given the opportunity to gain a foothold. “In our systems, herbicides are the number 1 and often the only tool for managing weeds in a targeted manner. So the concern is to avoid the emergence of resistant populations.”

For more on weed management, visit the agronomy section at www.topcropmanager.com.

Too much or too little water can affect the quality and yield of your crop. And when the decisions you make on your farm impact this natural resource, what matters most is how you use it. Whether you farm from the cloud or the field, know you have the control and precision to make each drop count. Introducing the Irrigate-IQ™ precision irrigation solution from Trimble. See it at www.trimble.com/agriculture. For the field. For the yield. For the life of your farm.

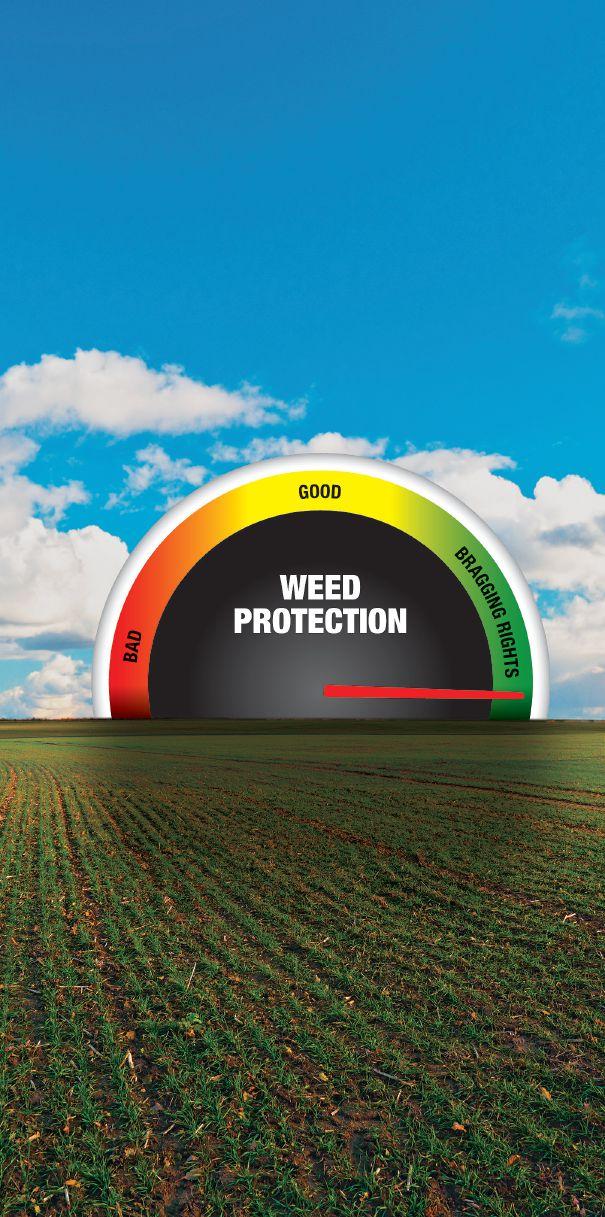

A few new herbicides and label updates to help target weed challenges.

by Bruce Barker

New herbicide product registrations and label updates continue to bring more choice to farmers managing weed infestations and herbicide resistance. product information is provided by the manufacturers.

Burndown herbicides

Priority: florasulam (group 2) – priority mixed with glyphosate controls a wide range of hard-to-kill broadleaf and grassy weeds. When used in combination with glyphosate, priority may be applied pre-seed or post-harvest prior to seeding wheat (spring, winter and durum), barley and oats. priority is also registered for use with glyphosate in chemfallow.

Grassy and broadleaf weed herbicides

Focus: carfentrazone (group 14) + pyroxasulfone (group 15) –registered in both corn and soybeans, Focus is a co-pack of two distinct new modes of action. Focus controls major broadleaf and grassy weeds and is powered by the new active ingredient pyroxasulfone, which has unique characteristics providing extended residual weed control well into the season.

Grassy weed herbicides

Bengal WB: fenoxaprop (group 1) – Bengal WB controls wild oats, barnyard grass and foxtail (green and yellow) in spring wheat, durum and barley with nearly 30 broadleaf tank-mix partners.

Broadleaf weed herbicides

Topline: florasulam (group 2) and MCpa ester (group 4) –

TopLine controls a wide spectrum of broadleaf weeds in wheat, barley and oat crops. For best results, TopLine should be applied when weeds are in the one- to four-leaf stage and the cereal crop is in the two- to six-leaf stage.

Rush 24: fluroxypyr and 2,4-D ester (group 4) – rush 24 controls a wide spectrum of broadleaf weeds in spring wheat, durum wheat and barley. With two group 4 active ingredients, rush 24 controls tough broadleaf weeds such as cleavers, kochia and wild buckwheat, including group 2 resistant biotypes.

Ares: imazamox + imazapyr (group 2) – addition of roundleaved mallow and russian thistle control to the label.

Assure II: quizalofop p-ethyl (group 1) – now registered for use in sunflower and yellow and brown mustard, and also for the control of Downy Brome.

Frontline XL: florasulam (group 2) + MCpa (group 4) – Minor use registration application for control of labelled weeds in seedling or established timothy at the two- to six-leaf stage.

OcTTain XL: fluroxypyr + 2,4-D (group 4) – Dry beans, potatoes, sugar beets and sunflowers were added as safe to recrop the year following an application of ocTTain. also registered by air with a recommended water volume of three to five gallons per acre.

Odyssey WDG: imazamox + imazethapyr (group 2) – Minor use addition for the control of labelled weeds in fababeans.

ABOVE: New herbicide registrations may help better manage herbicide resistance.

Prestige XC: fluroxypyr + clopyralid + MCpa (group 4) – Winter wheat and oats are now registered crops with control of labelled broadleaved weeds. now registered for aerial application at three to five gallons per acre water volume.

Roundup WeatherMax + Pardner: glyphosate (group 9) + bromoxynil (group 6) – new tank-mix registration for roundup WeatherMax + pardner preseed canola. This is for additional control of volunteer canola (all types) prior to the planting of canola (all types).

Simplicity: pyroxsulam (group 2) –application timing on wheat now from three-leaf stage to just before flag leaf. addition of corn spurry, cow cockle, shepherd’s purse and stinkweed as controlled weeds and suppression of Canada thistle and russian thistle. also registered by air with a recommended water volume of three to five gallons per acre. addition of potato and sunflowers to safely recrop 10 months after applications. now registered as rainfast within two hours after application.

Poast Ultra: sethoxydim (group 1) –a minor use for the control of labelled weeds in fenugreek and grapes.

Viper ADV: imazamox (group 2) + bentazon (group 6) – amendment of the Viper aDV label to include suppression of group 2 resistant biotypes of kochia. Succulent peas added to label as registered crop.

pending registration and based on the data submitted by Bayer CropScience, the weeds below will be added to the following product’s labels:

Velocity m3: thiencarbazone (group 2) + pyrasulfotole (group 27) and bromoxynil (group 6)

Tundra: fenoxaprop (group 1) + pyrasulfotole (group 27) and bromoxynil (group 6)

Infinity pyrasulfotole (group 27) + bromoxynil (group 6)

• Stork’s-bill (one- to eight-leaf stage, only with the addition of 2,4-D)

• giant ragweed suppression (one- to six-leaf stage, with aMS)

• Canada fleabane (up to 10 cm in height/diameter, with aMS)

• narrow-leaved Hawk’s beard (up to 10 cm in height, prior to bolting)

“We’re

Glyphosate-resistant waterhemp is moving north along the Red River Valley.

by Carolyn King

According to weed specialists, it’s likely just a matter of time before glyphosate-resistant waterhemp arrives in the province of Manitoba.

Before the 1980s, waterhemp seems to have been a fairly uncommon annual weed in crops in the U.S. Midwest. Then in the mid to late 1980s and 1990s, the weed became a growing concern. one of the reasons for that was waterhemp’s ability to develop herbicide resistance. For instance, in the 1990s waterhemp biotypes with resistance to group 2 or group 5 herbicides became increasingly common in the Midwest.

“In my own experience, waterhemp was a relatively unknown weed in north Dakota until we got the roundup ready crops and the overuse of roundup,” says Dr. rich Zollinger, extension specialist in weed control at north Dakota State University (nDSU). That management change led to the development of glyphosate-resistant waterhemp.

Waterhemp’s ability to continually overcome our control measures provides a great example of Zollinger’s motto: “Mother nature always wins. no matter what we do, Mother nature will find a way to upset our most glorious plans.”

Waterhemp is now such a problem in eastern north Dakota, particularly along the red river, that nDSU named waterhemp its Weed of the Year in 2012. nDSU gave 16 reasons why waterhemp has become so troublesome. Some of the reasons relate to the weed’s biology, and some relate to management practices.

TOP AND ABOVE: Glyphosate-resistant waterhemp is a troublesome weed in eastern North Dakota, and it is spreading north toward Manitoba along the Red River (top). One difference between waterhemp and redroot pigweed, the weed shown here, is that redroot pigweed stems have hairs, while waterhemp stems have little to no hair (above).

Zollinger highlights a few of the reasons. “The seed is small and light, so it can be transported very easily through water flow, especially flooding. The plant has a very long germination period. It can emerge with the main weed flushes in the spring, and emergence can continue all the way into august [so two post-emergent herbicide applications may be needed to control it].”

Waterhemp also takes advantage of any opening in the canopy. If there is a drowned-out area or a skip with the planter, it thrives in that kind of a situation. “In waterhemp, one plant is male and the other is female, and the female plants can produce easily over a million seeds per plant. In Iowa, a waterhemp plant was documented to produce almost five million seeds,” notes Zollinger.

“But probably the most important factor is that waterhemp has become resistant to several different herbicide modes of action including group 2 [amino acid inhibitors]. We just discovered group 4 resistance, which are growth regulators; group 5, the triazines; and of course glyphosate, group 9. Some states have waterhemp populations that are resistant to group 14, the ppo inhibitors, or group 27, the HppD inhibitors. and there’s multiple resistance in some states: for instance, some populations are resistant to group 2 and group 9 and group 14 or 27.”

Waterhemp’s adaptability to different weed control tactics comes from its wide genetic base. The weed relies on cross-pollination, rather than self-pollination, so there is always a mixing of genetic material. given its huge seed production, there’s a good chance the population will include at least a few individual plants that are resistant to the current control measures. as well, waterhemp’s pollen spreads by the wind, so pollen from resistant plants can easily spread resistance genes to new areas.

In addition, waterhemp and several other weed species in the same genus, Amaranthus, are able to interbreed, which can be another way to spread genetic adaptions to different conditions. Waterhemp itself used to be considered two species – Amaranthus

tuberculatus and Amaranthus rudis – but frequent hybridization between these two has led many weed scientists to consider them as one species. Some other Amaranthus weeds in Manitoba include redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus) and green pigweed (Amaranthus powellii).

Some of the other reasons for the rise of waterhemp in north Dakota include overreliance on glyphosate alone, mistaken identification of the different Amaranthus species and the resulting ineffective herbicide selection, failure to make timely herbicide applications to control small plants, mistaking herbicide resistance for herbicide application problems, and failure to remove early infestations of herbicide-resistant plants.

“So far waterhemp has not been reported as a major weed anywhere in Manitoba, although we know the weed may occur in a few spots in the province,” says Dr. nasir Shaikh, provincial weed specialist with Manitoba agriculture, Food and rural Development (MaFrD).

“However, glyphosate-resistant waterhemp will show up in Manitoba eventually; it’s just a matter of time.”

Data on the spread of glyphosate-resistant waterhemp show that it’s moving north toward the Manitoba border. Dr. Jeff Stachler of nDSU and the University of Minnesota has produced a series of maps tracking the yearly spread of glyphosate-resistant weeds in north Dakota and Minnesota. Those maps show that glyphosate-resistant waterhemp was first confirmed in 2007 in a county on the Minnesota river, a tributary of the red river. Since then, confirmed and highly

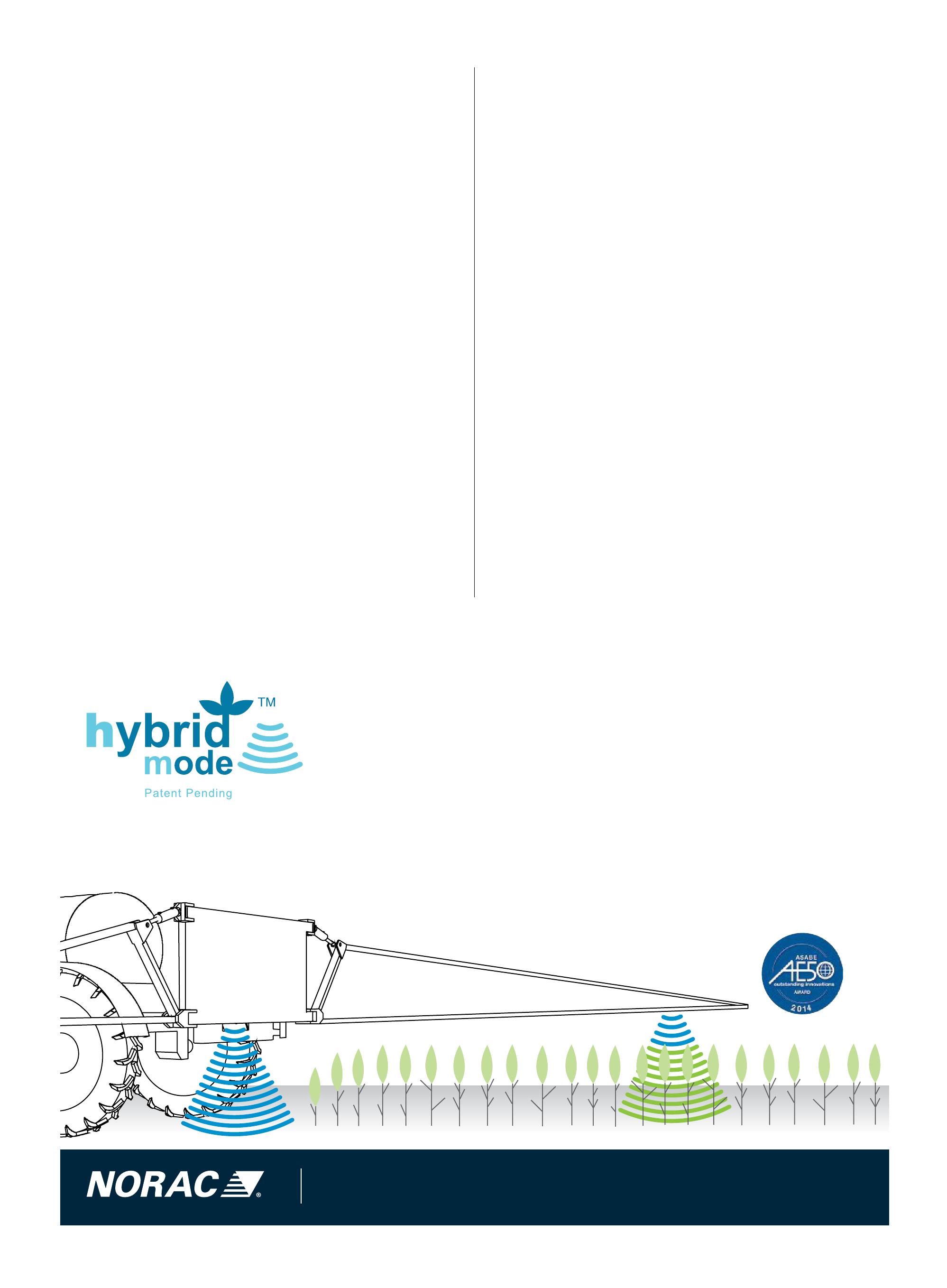

We aren’t surprised to hear words like impressive and dependable when people talk about NORAC’s award winning Hybrid Mode™.

Hybrid Mode™ reduces the need for the operator to take manual control of the boom while spraying lodged, thin or uneven crops.

What you may be surprised to hear is that our Hybrid Mode™ advanced crop spraying feature is exclusive to NORAC Spray Height Control Systems.

suspected occurrences of this biotype have multiplied, spreading along the Minnesota river and then the red river. as of 2013, the biotype had spread as far north as Traill County, about 200 kilometres south of the Manitoba border.

Shaikh and his Manitoba colleagues collaborate with Stachler, Zollinger and other weed specialists in the U.S. and Canada to share information on the latest weed issues. Shaikh notes, “We are definitely keeping an eye out for weeds that may move from south of the border into Manitoba, especially through waterways, via the red river Valley or even the Souris river.”

The spread of glyphosate-resistant weeds is a key issue. “over the last couple of decades, many growers have moved toward minimum or zero tillage, and they have been using glyphosate year after year after year. especially with a species like waterhemp, which has a very wide genetic base and can produce from 200,000 to 5 million seeds per plant, there’s so much genetic diversity that it is very easy for it to develop resistance when the same herbicide is used again and again,” says Shaikh.

He is also concerned about the potential for the spread of herbicide resistance through crosses between waterhemp and its Amaranthus relatives. “redroot pigweed, which is a close cousin of waterhemp, is a major weed in Manitoba. Unfortunately we have group 2-resistant redroot pigweed in Manitoba and this biotype has been spreading somewhat over the last few years.” as well, Manitoba has group 2-resistant green pigweed (also called powell amaranth).

For now, Shaikh advises Manitoba growers to be on the lookout for waterhemp. It can be hard to distinguish waterhemp from its pigweed cousins, especially at the seedling stage. But, as Zollinger notes, there are good online sources for accurate identification of the various species in this family.

“Identification is the first step in successful weed control. Waterhemp leaves are more shiny and waxy than redroot pigweed [and powell amaranth] leaves, which are more of a dull green colour. redroot pigweed has more of an ovate-shaped leaf, while waterhemp has more of a narrow, elongated leaf. also, waterhemp stems have little to no hair compared to redroot pigweed and powell amaranth,” says Zollinger.

“and of course if anybody is overusing roundup, then that would be an environment where glyphosate-resistant waterhemp would come through quite quickly.”

Shaikh reminds growers to take steps to

reduce the risk of herbicide-resistant weeds developing on their own farms. “once a weed develops resistance, it’s like the horse is already out of the barn; you can’t use that herbicide chemistry anymore. Integrated weed management is the key [to preventing and managing herbicide resistance]. It includes practices like rotating crops, rotating herbicide modes of action, and using non-herbicide methods of weed control – mechanical, cultural and agronomic methods.”

He adds, “The biggest plus we have in Manitoba is a lot of diversity of crops. That really helps us to have a more diverse crop rotation and a better herbicide rotation compared to south of the border.”

Zollinger also recommends scouting about one or two weeks after each herbicide application to check for resistant weeds. If most of the weeds in the field are dead but a few individual plants have survived, then those individuals may be resistant to the herbicide. resistance needs to be confirmed through lab testing to make sure the plant’s survival is not just due to something like a sprayer skip.

If you find plants that you suspect may be herbicide-resistant, Zollinger suggests erring on the side of caution: kill or remove the plants before they set seed.

With a single plant releasing perhaps a million seeds, a serious infestation could develop very rapidly if glyphosate-resistant waterhemp plants are left unchecked.

For more on weed management, visit the agronomy section at www.topcropmanager.com.

Reclaiming high productivity land and improving crop yields with tile drainage.

by Donna Fleury

Unusually wet conditions over the past few years in central alberta have convinced some growers to add underground tile drainage to their cropping systems.

Craig Shaw of Durango Farms at Lacombe, alta., has experienced extremely wet soil conditions over the past few years, losing yield and productivity on some of his best land.

“Some of our best land with high organic soils tends to be in the lower areas,” says Shaw. “Those areas are where we used to get the big bushels and high returns from our crops, but over the past three years the yield data shows those areas are now producing the lowest yields on the farm. We realized that with very high land values in our area combined with high rental costs and inputs, there are substantial costs involved and all of the land needs to be producing at the highest level.”

Shaw partnered with a neighbouring potato grower to purchase an ag Leader Tile plow system in the winter of 2012. The initial investment for the plow, monitors and controls was about $50,000, with some additional investment in more gpS components, different boots and tile. “our system is based on an rTK gpS system, which has been a major improvement over laser systems,” says Shaw. “The gpS program marks all of the tiles, so if we need to go in and make another connection or change something, we know where everything is.”

Unlike areas such as the red river Valley in Manitoba where tile drainage is typically installed across an entire field in a grid system, Shaw has targeted specific areas in his fields. These tend to be low-lying areas that stay too wet much of the time. “We decided to start with some very wet areas after seeding in the spring of 2013 to get some tile in the ground and optimize the installation system,” explains Shaw. “We also had some fields in silage as well as some severely hail damaged fields, so we installed more tile during the summer and through to the end of november when the snow finally made us stop.”

Installation starts with taking the plow in survey mode across the area where the tile will run. at the end of the line, the plow is set on install mode and installs the tile along the survey line calculating the grade as it goes along. During installation, the plow always starts and moves from low ground to high ground. Shaw uses six-inch tile for the main line and four-inch for most of the rest of the tiling, installed about 36 to 40 inches deep. He also adds a fabric sock to help prevent the slots on the tile from plugging up in sandier soil. The four-inch tile costs $0.50 per foot and the sock adds $0.15 per foot, for a total of $0.65 per foot; costs for six-inch are slightly more. The

Shaw hopes to bring his saturated land back into production.

plow does leave a small soil crown, which will naturally settle back in most soils, but in heavier clay soils, it may need to be smoothed down before seeding.

“The grade is one of the most important aspects, with a minimum of one foot in 1,000 or a .01 per cent grade,” explains Shaw. “The more grade the better, which is reflected in how quickly the water can be dissipated from the field. We were amazed to see that when we were installing the tile, by the time we got to the top of the field the water was already running out of the outlet. The system is

gravity fed, which is why grade is so important.”

Shaw is very proactive in managing outflow, and makes sure the water runs out where it naturally flows so it isn’t negatively impacting anyone else. The water removed from the field has been filtered in the soil and is very good quality.

Shaw believes the payback on the tile drainage installation will be fairly fast. “We could see that underground tile drainage would be a substantial investment, but we could also see a number of positive returns including the ability to farm our fields corner to corner,” says Shaw. “We expect to be able to get into our fields in a more timely fashion, up to at least a week earlier in the spring than before. We should also be able to seed the entire field at once, rather than waiting for the low-lying areas to dry enough so we can get back in and seed. When we have to go around wet areas, seed and fertilizer inputs are often double, lodging issues are a problem, so we expect to see a multiplier effect with the inputs.”

Shaw has installed tile drainage on most of the land he owns and on some rented land. “We like to have rental agreements in place for at least four or five years, with some cost sharing of the tile and initial installation, which will pay back in terms of higher net returns. I think we are going to see a large amount of tile drainage installations in the corridor in central alberta over the next few years. This area seems to be getting wetter over time and combined with high land prices, high rental costs and input costs, tiling has been a great investment on our farm.”

For more on soil and water management, visit the agronomy section at www.topcropmanager.com.

• The AI3070 utilizes a unique, patent-pending design optimized specifically for fungicide application

• The 30° forward tilted spray penetrates dense crop canopies, while 70° backward tilted spray maximizes coverage of the seed head for excellent disease control

• Air induction technology produces larger droplets to reduce drift

“ The AI3070 increased overall deposit amounts and uniformity compared to the industry standard single and twin fan nozzles.”

TOM WOLF, RESEARCH SCIENTIST AT AGRICULTURE AND AGRI-FOOD CANADA

Pyroxasulfone offers unique mode of action for weed control in peas.

by Donna Fleury

Herbicide resistance is increasing across Canada, with group 2 herbicide resistance becoming very common. For crops such as peas, this can be problematic because of the dominant use of group 2 herbicides. researchers are testing a new mode of action that could provide another weed management tool for growers.

“recent research from agriculture and agri-Food Canada estimates that 29 per cent of annually cropped land in Canada is occupied by herbicide resistant weeds,” says Breanne Tidemann, a graduate student at the University of alberta.

Indeed, the group 2 or aLS inhibitor products are the most common group that weeds are evolving resistance to, which is a particular problem for a crop such as peas that are mostly limited to aLS herbicides for weed control.

“We are evaluating a new herbicide, pyroxasulfone, which has been

tested in australia on peas and shown good tolerance,” says Tidemann. “pyroxasulfone is a group 15 herbicide and a relatively unique mode of action in the Canadian prairies, which could really help our growers with weed control and in particular herbicide resistant weeds in peas.”

Tidemann is working with researchers at the University of alberta, agriculture and agri-Food Canada in Saskatchewan and the University of Saskatchewan who are leading various research trials with pyroxasulfone and weed control in crops such as pulses and winter wheat.

pyroxasulfone is a soil-applied herbicide that can be used in the fall or in the spring pre-seeding or pre-emergence. pyroxasulfone is

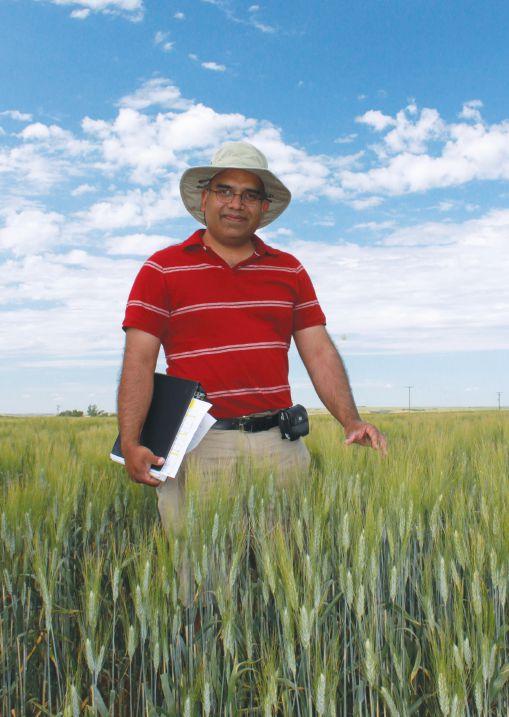

TOP: Green foxtail treated with pyroxasulfone.

INSET: Breanne Tidemann is working with other researchers to assess the potential of pyroxasulfone.

currently registered for use on field corn and soybeans in Canada.

“one study initiated in 2011 compared pyroxasulfone rate and timing at five sites in alberta and Saskatchewan with a wide range of soil types and organic matter levels,” explains Tidemann. “pyroxasulfone is a soil-applied herbicide and, as a result, can be affected by organic matter levels, soil moisture and other factors. The sites we selected ranged from 2.9 per cent to 10.6 per cent organic matter. We also compared two timings of application, a post-harvest application in the fall prior to the pea crop and pre-seeding, the more typical timing of this product.” The rates included 0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 300 and 400 g ai/ha of pyroxasulfone and an application of Viper as an industry standard.

The results from this study, recently published online ahead of print in Weed Technology, showed that both fall and spring applications were effective, and there were no consistent differences in timing. However, organic matter and soil moisture did have an impact on the effectiveness of the herbicide at different rates and with different weeds. With wild oat, efficacy started at lower rates, but results were variable, with around 80 per cent control the average top level achieved. Cleavers could be controlled 100 per cent, with rates depending on location and organic matter.

The study also showed the higher the organic matter, the higher the rates of pyroxasulfone required, sometimes higher than what might be feasible. “With rates up to 200 g ai/ha, we did not see any pea crop injury, except in the spring of 2011 at the Scott and Kernan sites where they experienced 200 per cent of normal rainfall,” says Tidemann. “The rates considered effective at edmonton resulted in crop injury at the Scott and Kernan locations in that spring. It seems that at higher soil moisture levels the herbicide is more active.” overall the best weed control was at the lowest organic matter sites of Scott and Kernan. For those sites an application rate of between 100 and 150 g ai/ha is expected to be adequate, however rates will vary depending on location and organic matter levels.

another field trial compared two soil-applied herbicides in combination, pyroxasulfone and sulfentrazone (authority), a group 14 herbicide, and their effectiveness on cleavers and wild oat at four sites in

2011 and repeated in edmonton and Scott in 2012. The trial compared five rates of pyroxasulfone (0, 80, 100, 150, 200 g ai/ha), four rates of sulfentrazone (0, 105, 140, 280 g ai/ha) and all combinations of the two herbicides.

“We wanted to determine the effectiveness and interaction of the herbicides at the various rates,” explains Tidemann. “We wanted to know if the combination provided better than expected control or synergy, or if the control was worse than expected because they antagonize each other, or if the two products were additive. The results show that the interaction of the two products seems to be additive and the benefit from the combination is a broader spectrum of weed control and management, and prevention of herbicide resistant weeds. Location, soil and environmental conditions also seem to have an impact on the effectiveness.”

a further study was initiated in the greenhouse to more closely examine the interactions of this herbicide combination. Various soil factors such as organic matter levels and soil moisture were compared. results indicated that organic matter levels do have an impact on the rate for effectiveness. Tidemann is in the process of completing the final write up of these studies and expects to complete her thesis this spring.

So far, the studies indicate that pyroxasulfone has the potential to control weeds such as wild oat, cleavers and kochia, depending on the location and environmental factors. other weeds such as green foxtail, downy and Japanese brome, are being studied in other trials, and seem to show good control. “FMC Corporation expects to have registration for pyroxasulfone products for spring and winter wheat approved by the end of 2014,” says Tidemann. “registration for a combination product with sulfentrazone for peas is also expected in 2015. If registered, pyroxasulfone products will provide another alternative tool for reducing the risk of herbicide resistance and managing group 2 resistant weeds.”

For more on seed/chemical, visit www.topcropmanager.com.

Designed for maximum capacity and speed, the Brandt 7500 HP GrainVac helps you operate at peak effciency. With input from producers like you, we’ve refined our GrainVacs to include many innovative features only available from Brandt. With fewer moving parts, and premium build quality this GrainVac delivers unrivaled reliability and durability. That’s Powerful Value. Delivered.

The patented feature takes the back work out of cleaning right to the bottom of the bin or pile.

This lightweight 8" nozzle adjusts air and grain mixture utilizing louvers and stainless steel adjusting bands to maximize grainflow and capacity.

Fill a 1,000 bushel Trailer in only 8-9 minutes thanks to Brandt’s patented Cone Separator technology which provides optimal separation of the grain from the air stream without any moving parts while maintaining maximum airspeed in all grains.

Utilizes two hydraulic cylinders that allow the auger to fold and unfold while positioned next to the bin.

Hardened steel and chrome plating maximizes grain flow and auger life.

Securely holds the GrainVac in position and provides a safe route for static electricity discharge. It’s sequenced to automatically fold and unfold with the auger.

by Bruce Barker

atiny little wasp is turning out to be a farmer’s best friend. researchers with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) discovered the parasitoid wasp, Tetrastichus julis, shortly after the cereal leaf beetle was found in Western Canada. The wasp, with help from its friends at aaFC, is helping to keep the cereal leaf beetle, Oulema melanopus, from reaching economically damaging levels.

“This is a bad news good news story. The bad news is that we now have cereal leaf beetle in Western Canada. The good news is that we have a beneficial insect that is quite capable of taking it out,” says Héctor Cárcamo, research scientist at the aaFC Lethbridge research Centre.

Cereal leaf beetle has been in Western Canada since 2002, first appearing in British Columbia, and was discovered on the prairies in 2005 at Lethbridge, alta. In 2006 it was found in southwest Sask.; and around Swan river, Manitoba in 2009. Subsequently, new populations have been found near edmonton, red Deer and olds, alta.; Moosomin and Langenburg, Sask.; and in fields near Brandon, Holland, Treherne, Killarney and pilot Mound, Man.

“The distances between the populations mean the cereal leaf beetle is likely moving in hay being transported, as it can’t move those distances on its own,” says Cárcamo.

The cereal leaf beetle has potential to be an economically damaging pest, and attacks many wild and cultivated grasses. The insect prefers wheat, oat, barley, rye, timothy, fescue, grain sorghum and corn. economic loss is mostly caused by the larvae, which strip the leaves, resulting in loss of photosynthetic activity.

Larval feeding leads to significant losses in crop yield quantity and quality due to reduced photosynthetic activity. Cárcamo says most crop damage is caused by the late larval instars with the fourth instar alone responsible for about 70 per cent of all damage. Feeding at the flag leaf stage is most damaging to crop yield. adult feeding is characterized by uniform longitudinal incisions. Wheat crops are most prone to the attack by both larvae and adults.

In alberta, T. julis was discovered in local larval populations of cereal leaf beetle, and no introductions of the parasitic wasp were required. Surveys have since determined that T. julis is expanding its range in southern alberta in synchronization with the cereal leaf beetle.

The adult female wasp lays four to six eggs into a cereal leaf beetle larva. It overwinters in the larval stage within the pupal cell of its host at a soil depth of three to five centimetres. overwintered females parasitize mostly early developing beetle larvae at the beginning of the season. The parasitized host larva dies after pupation. parasitization is high in spring with a peak in mid-May to June. However, the second generation of adults also parasitizes late-maturing host larvae.

at Creston, B.C., surveys determined that parasitism was as high as 90 per cent. Levels of parasitism in southern alberta have increased since 2007, and Cárcamo says that parasitism is now around 40 per cent.

Cárcamo heads up aaFC’s T. julis biological control program, and he is giving the wasp a helping hand in controlling the cereal leaf beetle in an effort to keep the beetle from reaching economically damaging levels. The control program consists of rearing T. julis in a combination of laboratory and field nurseries, and releasing the wasp in fields where the cereal leaf

MAIN: The cereal leaf beetle strips tissue from plant leaves.

beetle has been identified. The parasitoids are reared in a protected field area with deliberate cereal leaf beetle infestations to support parasitoid growth under natural conditions. as new populations of cereal leaf beetle are identified, adult wasps or cocoons (depending on the time of year) are released into the field.

The new populations of cereal leaf beetle in Manitoba seemed to lack T. julis populations; so southern alberta populations were relocated in an effort to establish the wasp. relocations were conducted in 2009 and 2010 in the Swan river region where the cereal leaf beetle was established. In 2011, surveys found that approximately 22 per cent of cereal leaf beetle larvae collected were parasitized by T. julis, indicating the wasp is established in the Swan river Valley. The parasitic wasp has also been relocated to other regions in central alberta and southern Manitoba where the cereal leaf beetle has become established.

“We are lucky we have a parasitoid that can control the cereal leaf beetle. We don’t expect the beetle will reach outbreak levels thanks to T. julis,” says Cárcamo.

research has also been conducted locally on non-target beetles to see if they are at risk from T. julis parasitism. With the help of a visiting graduate student, Vincent Hervet, and his research team, Cárcamo found that none of the closely related non-target beetles were parasitized. This indicates that T. julis is quite host-specific to the cereal leaf beetle and poses little threat to local biodiversity.

Under aaFC’s pesticide risk reduction program, the T. julis biological control program was extended in 2013 for three years, ending March 31, 2016. This project aims to continue the earlier relocation efforts to introduce the parasitoid T. julis in cereal production areas where the cereal leaf beetle is most prevalent, but the parasitoid is not yet recorded. The work will include surveying the target areas to assess presence of T. julis in cereal crops as well as mass rearing and releasing the parasitoid in areas where it is needed. The project also includes the use of landscape ecology techniques to identify landscape attributes conducive to successful establishment and long-term conservation of the parasitoid. The resulting information will be contained in beneficial management practices recommended for adoption by growers aiming to maximize the efficacy of biological control of cereal leaf beetle in their crops.

Cárcamo says that if farmers or their crop scout find high numbers of cereal leaf beetle in the field, they should get in touch with their provincial entomologists or aaFC Lethbridge to assess the need for the establishment of a T. julis biological control program.

“We can send you some material to get your own colony of parasitoids established on your own field,” says Cárcamo.

a final message for farmers and crop scouts is that the sprayer needs to be left in the yard. Insecticides applied to control cereal leaf beetles are also lethal to T. julis and counterproductive for the sustainable long-term management of this pest.

“We recommend that you do not spray for cereal leaf beetle because the parasitoids will take care of it. This is one case where a biological control program is successfully holding the pest below economically damaging levels, and we need to help ensure that widespread chemical control is not required,” cautions Cárcamo.

ESN can replace a second top dress application.

by Donna Fleury

Protecting nitrogen (n) fertilizer until plants are ready to use it is important for reducing potential n losses and maximizing yields. For crops such as corn or sunflowers that take up much of their nitrogen after the first few weeks of growth, using a controlled release product like eSn at seeding can replace a second top dress application and improve seed safety.

“We have completed a lot of research on corn in the U.S. and have shown that growers can make one application of eSn at seeding that provides for slow release of n and eliminates the need to go in and top dress later in the growing season,” explains ray Dowbenko, agronomist with agrium. “although we have done little formal research on smaller acreage crops like sunflower, we know that sunflower is similar to corn in terms of timing of n uptake, but not total n requirements. Therefore, we may be able to use corn as a proxy for crops like sunflower to consider timing of n requirements and the best strategy for application. Sunflower is also very sensitive to fertilizer, which may make the

use of a controlled release or polymer coated product a strategy for improving seed safety.”

eSn is a controlled release n fertilizer that reduces n exposure to potential losses such as runoff, leaching and denitrification (loss of n gases to the atmosphere). eSn also improves environmental safety and reduces gas emissions from denitrification and ammonia volatilization. eSn protects against leaching loss on sandier soil and protects against denitrification on heavier ground. Studies verify eSn reduces n loss compared with conventional n fertilizers and provides a consistent nutrient supply and plant growth. eSn improves n-use efficiency, reduces the number of fertilizer applications and provides for greater seed safety.

as is the case with any crop production input, growers need to determine the need and fit of a controlled release product for

ABOVE: With similar nitrogen uptake to corn, ESN could be used with sunflower in a similar way.

Source: Agrium.

their operation. eSn may not have a fit for every grower, but it can provide benefits such as yield stability particularly where n losses are a risk.

“We started research on eSn in 1999, so we have almost decades of work in Canada and the U.S. in a series of different crops,” says Dowbenko. “The product is still providing the same positive results as it always did, yield stability, protection of n losses that result in yield increases, increase in seed safety and protein levels. For growers that have a reason to use eSn and see some type of value for the situation they plan to use it in, then eSn will do exactly what it is supposed to do: improve agronomics and environmental safety.”

the need for ESN growers should start by thinking about the land they farm, the type of soils and situation they have, and identify places where there is a high potential of value of using eSn. Dowbenko has developed a table as a guide for any crop, with corn as an example to help in making decisions (see Table 1). growers need to assess the level of soil organic matter in their field, drainage class and the level of early season and growing season precipitation, and then match the right fertilizer product to their system.

“If soils have low organic matter and are coarse textured and there is a potential of high rainfall, then under these conditions there is a high n loss potential and protecting n has a high bene -

fit,” explains Dowbenko. “However, under similar conditions but where soil organic matter is high, then there is still a high potential for loss, but because of the high soil organic matter there is also a high potential for n mineralization. So although the product protects against n loss, the soil may mineralize enough n to make up for the losses and you might not see a yield difference. Therefore, it is very important that growers understand the reason they want to use a product such as eSn; otherwise, they might find it didn’t work as they expected, either because they didn’t need the product in the first place or they used it for other reasons such as one application instead of split, or seed safety, and not just an increase in yield.”

The other factor is that different forms of fertilizer are released and perform differently in the soil. With eSn, about 8 to 15 per cent n is released in the first 10 days, about 40 to 60 per cent in the first month and about 85 to 90 per cent is released within 60 days. on the other hand, urea mostly dissolves within hours of application and ammonium formation can be complete in two to four days (environment dependent). after that, ammonium converts to nitrate over a couple of weeks (environment dependent); ammonium nitrogen is stable in the soil, but the nitrate form can be susceptible to loss. Understanding crop needs and timing of n uptake are important when making n fertilizer application decisions (see Fig. 1).

eSn also provides for seed safety because the coating acts as

Source: Heard, J., and Hay, D. Nutrient Content, Uptake Pattern and Carbon: Nitrogen Ratios of Prairie Crops.

Topcon’s new X14 Console proves that mini can be mighty, delivering powerful technical performance at an economical price. Start smart, then customize with features that grow with you. For convenience and ease-of-use at an attractive price, learn more about the X14 and your nearest Topcon dealer at www.Topconpa.com/x14.

a physical barrier between the seed and fertilizer. This can be a big benefit for crops like sunflowers and other crops where seed safety is a concern.

“growers may choose to use a blend of eSn with their conventional fertilizer or all eSn, depending on the level of seed safety they need,” says Dowbenko. “To determine seed safety, growers can use their provincial fertilizer guidelines for n requirements for their crops and then depending on the percentage of eSn in their fertilizer blend, can improve seed safety by as much as three times. In a blend with eSn, seed safety is increased by 1.5 to 2 times, while using 100 per cent eSn, seed safety is increased by three times. This may have a good fit, for example, for growers who have single shoot openers and don’t want to change to midor side-row banding equipment. They can often put down their full n requirements in the seed row in one pass by using eSn. For cereal growers, eSn provides for protein benefits and some growers are using eSn as part of a fertilizer blend in their wheat program.”

The recommended rate for eSn is at the same rate as a conventional n fertilizer program. potato and corn growers, for example, use 100 per cent eSn and sunflower growers should be able to use a similar program. In some situations, eSn can be applied as a split application and for some crops such as sunflower, fall application is also an option. growers need to look at their production economics on their operation and also fine-tune the percentage and rate with their local conditions and experience.

Under the right circumstances, there can be yield increases with eSn. “In Canada, we typically see a higher yield benefit on canola than cereals, with increases in canola yield of eight to 10 per cent on average, and wheat and barley six per cent on average. Cereals are determinant and set one head and fill, while canola is indeterminant and can keep flowering and setting on pods. So having n available later in the growing season is a benefit to the late pods that are still filling. We have also done some research to determine if late n causes problems with maturity or with green seed in canola, but no negative effects were shown in any studies.”

Dowbenko works all over the world, with programs in China, europe and South america, and the results of how the product performs in all of these locations are the same as in the U.S. and the northern great plains.

“We have lots of research with consistent results over many years to show that eSn works and does what it is supposed to do under the right conditions,” says Dowbenko. “although we don’t have all of the answers for all of the crops such as sunflowers, the guidelines we have developed for crops such as corn may be able to provide the information growers need to make decisions on their land and with their crops. Benefits such as protecting n applications, increasing efficiency, seed safety and environmental protection may be reasons enough, beyond just a yield benefit.”

For more on fertility, visit the agronomy section at www.topcropmanager.com.

The Stress Shield® component of Raxil® PRO Shield provides superior emergence, increased vigour and a healthier plant that’s better able to withstand unforeseen seasonal stresses.

This NEW formulation combines three different fungicide actives, including NEW prothioconazole, for complete systemic and contact protection from the most serious seed- and soil-borne diseases.

To learn more about Raxil PRO Shield, visit BayerCropScience.ca/Raxil

by Bruce Barker

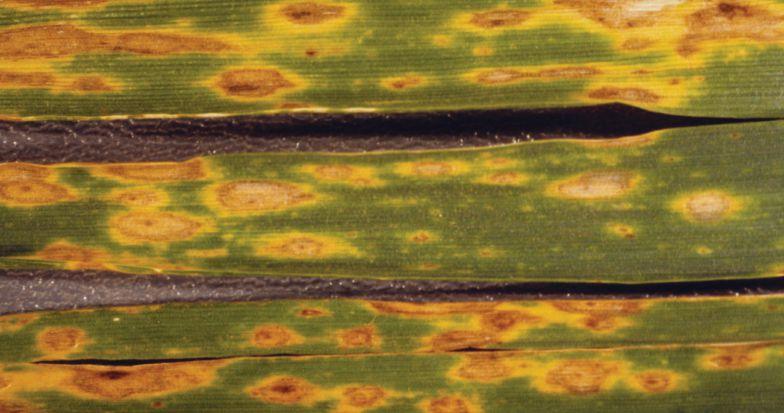

Physiological leaf spots have been common in the pacific northwest of the United States for many years, and have been frequently identified on the northern great plains of the United States and Canada. Most frequently seen on winter wheat, the phenomenon can also been seen in other cereals. It is presumed to result from an unknown metabolic process and can reflect a genetic weakness in a plant.

“physiological leaf spotting was a bit of an issue in 2012 in winter wheat but it can affect other cereals as well,” says Michael Harding, a research scientist in plant pathology with alberta agriculture and rural Development (arD).

physiological leaf spotting doesn’t always present symptoms in the same way. The incidence of physiological leaf spotting can vary among cereal types, varieties, crop management practices and seasons.

“From what I’ve seen, there could be a genetic component to the susceptibility of a variety to physiological leaf spot. Some varieties may be more prone to it,” says plant pathologist Kelly Turk-

ington at agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) at Lacombe, alta. “Some research has shown that chloride deficiency may also be a trigger for physiological leaf spots.”

CDC Kestrel winter wheat appears to be more susceptible, as does CDC Falcon. research by richard engel at Montana State University confirmed that winter wheat varieties differ greatly in their susceptibility to physiological leaf spotting.

Sun damage to the upper leaves may be a cause. other stresses on the plant, such as cool, cloudy and wet conditions followed by sunny conditions, could be a trigger. Some cereal crops develop yellow flecking, and in some crops there is a brown spotting or reddish brown spotting.

“It is not always clear what the symptom is going to look like, but what we do know is that in most cases, there is an environ-

CONTINUED ON PAGE 40

ABOVE: Chloride deficiency can be corrected using chloride fertilization.

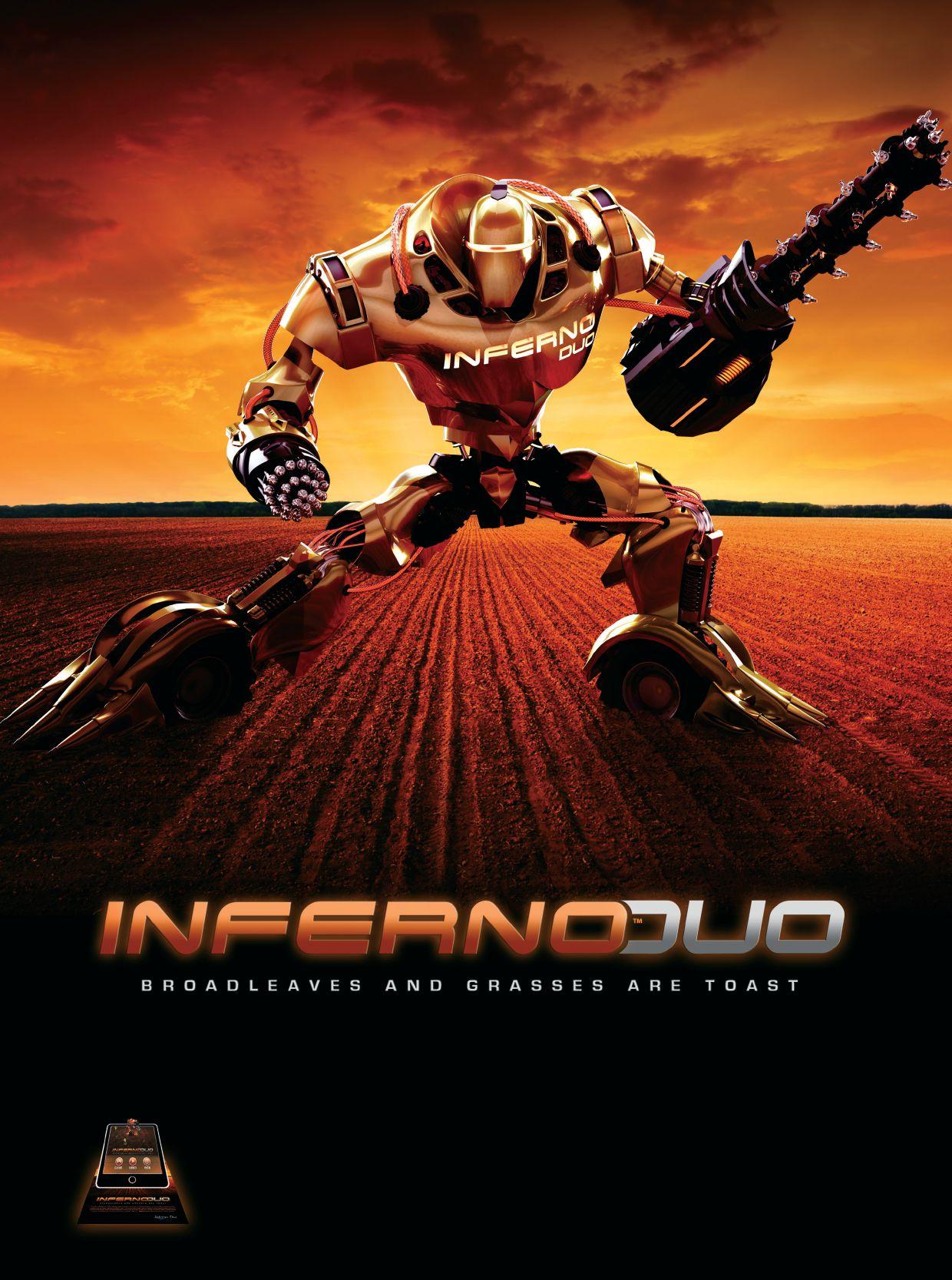

Tough broadleaves and flushing grassy weeds have met their match. No burndown product is more ruthless against problem weeds in spring wheat than new INFERNO™ DUO. Two active ingredients working together with glyphosate get hard-to-kill weeds like dandelion, hawk’s beard, foxtail barley and Roundup Ready® canola, while giving you longer lasting residual control of grassy weeds like green foxtail and up to two weeks for wild oats. INFERNO DUO. It takes burndown to the next level.

BRING THIS AD TO LIFE!

HOLD YOUR TABLET / MOBILE DEVICE OVER THIS AD AND WATCH INFERNO DUO DESTROY WEEDS LIVE! DOWNLOAD THE APP AT infernoduoalive.ca

Research is continuing to provide a greater understanding of how to best manage fields.

by ross H. McKenzie phD, p ag.; retired agronomy research Scientist

In the February 2014 issue of Top Crop Manager, the various processes to determine soil management zones were discussed. The purpose of identifying soil management zones is to compare the similarities and differences in soil and topography so that each “unique zone” can receive the right fertilizer, at the right rates, with the right placement and the right time (4 r’s), based on specific soil conditions.

after each zone is soil sampled, soil test results for each management zone must be carefully reviewed. Make sure the soil test report makes sense. are soil test levels for plant-available nitrate nitrogen (no3-n), phosphorus (p), potassium (K) and sulphate-sulphur (So4-S) clearly shown? are the soil test methods shown? (For example the Modified Kelowna method for soil test p is the standard in alberta and the olson method is the standard in Saskatchewan and Manitoba; all soil test correlation field research has been done with these methods in each province.) are the soil sample depths clearly shown? are the analytical results clearly shown in pounds per acre or parts per million (ppm)? Make sure you clearly understand the reports so results can be interpreted correctly. Most labs will provide general fertilizer recommendations; so a good place to start is to review their suggested fertilizer recommendations but the final fertilizer decisions fall to you; that’s your job in conjunction with your agronomic advisor.

review soil organic matter (oM) level, soil pH and electrical conductivity (eC) for each zone. Do the results make sense? For example, is soil oM higher in lower slope positions, and lower in upper slopes and eroded knolls? review soil test n, p, K and S results. Which nutrients are adequate, marginal or deficient in each zone? often p, K and S will be lower in upper slope positions as well as soil oM level. Soil pH is often higher in upper slope positions. Some labs will provide a bar graph to indicate if the level of each nutrient is adequate or deficient. But it is also a good idea to review the information from your provincial department

of agriculture website to determine when p, K, S or micronutrient levels are adequate, marginal or low. For example, alberta farmers should review the following alberta agriculture publications:

• phosphorus fertilizer application in crop production. agdex 5423. http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/agdex920

• potassium fertilizer application in crop production. agdex 542-9. http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/agdex917

• Sulphur fertilizer application in crop production. agdex 542-10. http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/agdex3526

• Micronutrient requirements of crops. agdex 531-1. http://www1. agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/agdex713

Using publications such as these can be very useful to decide which nutrients are deficient or adequate. In the alberta publications, fertilizer recommendation tables are provided to assist in deciding what rate of fertilizer should be added when soil test levels are deficient or marginal. Information is also provided on fertilizer placement and timing of application. It is important to note these recommendations are science-based from research conducted by university, federal and provincial scientists over a number of years, and is your best source of unbiased, reliable information.

Determining n fertilizer rates is not an exact science and is a challenge. nitrogen fertilizer response is function of a number of factors:

• Soil test nitrate nitrogen

• nitrogen mineralize potential of the soil, which is affected by soil organic matter level and soil management (mineralization poten-

ABOVE: Variable rate fertilizer research is continuing to provide a greater understanding of how to best manage fields.

tial refers to the ability of the soil to release plant available nutrients from soil organic matter)

• Stored soil moisture at time of seeding

• precipitation and temperature during the growing season

as a general rule, when soil test n is low, the potential crop response to n fertilizer will be high if soil mineralization potential is low and/ or precipitation amount in the growing season is high. Conversely, when soil n level is higher, crop response to n fertilizer will be lower when soil mineralization potential is higher and/or when growing season precipitation is lower. agronomists vary in their approaches to making fertilizer recommendations for different management zones. Some might suggest using higher fertilizer rates for management zones that are more productive, and recommend less fertilizer for less productive soil management zones. However, for each soil management zone, a number of soil factors should need to be taken into account. For example:

Lower topographic slope positions often have high soil organic matter with greater nutrient mineralization potential. These soils tend to be more fertile, and during the growing season lower slope position soils will often have higher amounts of plant available nutrients. Therefore, depending on soil test levels, it may be reasonable to slightly reduce fertilizer rates on lower slope soils.

Upper slope position soils will usually have lower soil organic with lower mineralization potential, particularly if erosion has occurred in the past. These soils tend to be less fertile. During the growing season, upper slope position soils will often have lower levels of plant available nutrients and, therefore, tend to produce lower yielding crops. However, depending on soil test levels, it may be reasonable to increase fertilizer rates on upper slope soils to improve soil fertility and crop yield potential. Using this plan in the longer term can lead to increased soil fertility, increased soil organic matter and improved crop yield potential.

alberta agriculture and rural Development (arD) has been conducting a Variable rate Fertilizer research Study to evaluate crop response to a number of different rates and types of fertilizers on soils with different slope positions. research is being conducted in the Dark Brown, Thin Black and Black soil zones. This study has shown very good n fertilizer response at all slope positions. often crop response to p and S fertilizer is greater on mid and upper slope positions due to lower soil test levels. Lower crop yield response to p fertilizer occurred on lower slope soils due

to higher levels of plant available p. Further, results have clearly shown that as soil salinity (shown as eC or electrical conductivity on a soil test report) levels in soil increase, fertilizer rates should be reduced accordingly.

To assist with developing n fertilizer recommendations, a program called alberta Farm Fertilizer Information recommendation Manager (aFFIrM) is very useful. It can be downloaded at no cost from the arD website. Information that is entered into the program includes the soil zone of the farm, crop to be grown, soil test results, estimated

cost of each fertilizer, expected crop value at harvest and expected moisture conditions. The program will use the most recent crop yield response information, will provide expected yield response to n fertilizer at three different moisture levels and will provide the economics of increased n fertilizer rates. This is a useful program to help plan optimum fertilizer rates.