TOP CROP MANAGER

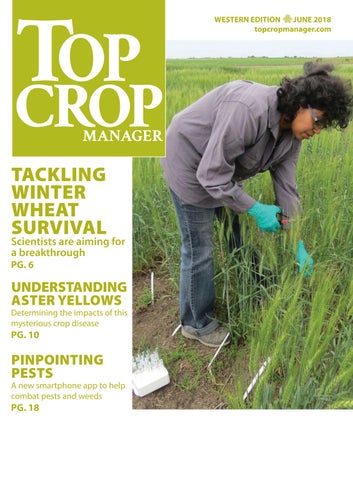

TACKLING WINTER WHEAT SURVIVAL

Scientists are aiming for a breakthrough PG. 6

UNDERSTANDING ASTER YELLOWS

Determiningtheimpactsofthis mysteriouscropdisease PG. 10

PINPOINTING PESTS

Anewsmartphoneapptohelp combatpestsandweeds PG. 18

Scientists are aiming for a breakthrough PG. 6

UNDERSTANDING ASTER YELLOWS

Determiningtheimpactsofthis mysteriouscropdisease PG. 10

Anewsmartphoneapptohelp combatpestsandweeds PG. 18

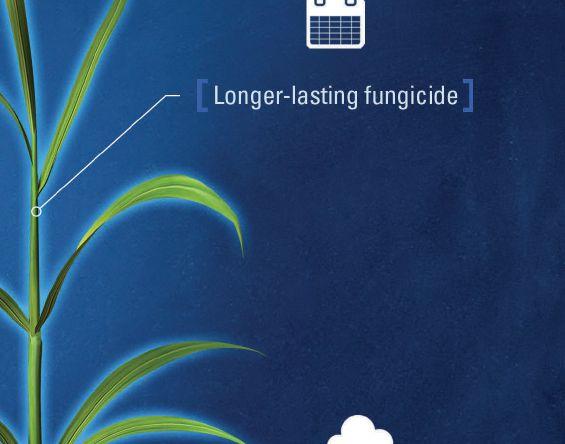

At BASF, we’re committed to providing our customers with the most advanced agronomic solutions. Cotegra ™ fungicide delivers best-in-class sclerotinia management in canola, and Caramba ® fungicide is recognized as the most trusted protection against fusarium head blight in cereals. And as part of our continuing goal to help increase growers’ profitability, we’re introducing an incredible offer.

To find out how you can take your crop potential to new heights, see your local retail, contact your BASF Sales Representative or call AgSolutions Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273). For full terms and conditions, visit agsolutions.ca/Growforit

6 | Aiming for a breakthrough Tackling the complex and critical issue of winter survival in winter wheat.

By Carolyn King

Nitrogen balance in century-old wheat experiments Unknown nitrogen inputs help balance nitrogen removals.

By Bruce Barker

| Pinpointing pests

A new smartphone app can help identify weeds and insects.

by Mark Halsall

The emergence and status of herbicide resistance in Europe and its management

Presented by Josef Soukup at Top Crop Manager’s 2018 Herbicide Resistance

The state of herbicide resistance in Western Canada

Bruce Barker

Presented by Hugh Beckie at Top Crop Manager’s 2018 Herbicide Resistance Summit

STEFANIE CROLEY | EDITOR

While most producers are wrapping up planting this spring, the Top Crop Manager team has soil on the mind. We’ve spent much of the very long winter and even shorter spring season planning our 2019 Soil Management and Sustainability Summit (to be held Feb. 26, 2019 in Saskatoon, and March 11, 2019 in Ottawa – check out www.topcropsummit.com for more details).

When we plan our annual research summits, we spend a lot of time working on the marketing and promotion of the event – not only because we want to convey what attendees and participants can expect from the event, but also because the words we choose play an important role in the content we provide. In agriculture, buzzwords like management and sustainability are thrown out in regular conversation, and it is no coincidence those two words are part of the name of the 2019 Summit. Healthy soil is a key component to a successful crop, and with research, products, education and resources readily accessible, it can be something Canadian producers may take for granted.

Canadian farmers play an important role in contributing to the global food chain, but most are fortunate enough to be able to rely on other sources besides their own crop to put food on the table. But for families who do look to their own crops to feed their families, a poor crop year can have devastating consequences. I was reminded of this recently when I came across an article about a project happening in Ethiopia, where conservation agriculture practices have become life changing. The Scaling-up Conservation Agriculture in East Africa program of the Canadian Foodgrains Bank is halfway through a five-year term that aims to have 50,000 farmers practicing conservation agriculture after five years. Through the program, which comprises 11 projects across Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania, families who struggle to grow enough to support themselves are being trained in conservation agriculture methods to increase the fertility of their soil and improve their yields. In one example, farmers in Ethiopia practicing conservation agriculture yielded an average of 925 kilograms of faba beans per hectare. Those using conventional methods saw an average yield of 750 kilograms – a nearly 25 per cent difference. Another farmer reported yielding more than 200 kilograms of maize in an area where he once had next to no yield because of drought.

Of course, there are critics and skeptics to the suggested conservation ag techniques, but the success stories are quickly spreading from one farm to the next. By the end of last year, more than 21,000 farmers had adopted the practices, and the program is on track to hit its target.

It’s easy to take for granted the luxuries, no matter how big or small, we have access to in Canada – I’ll be the first to admit this from where I sit in my climate-controlled office with an abundance of resources at my fingertips. Reading about how these farmers developed new appreciation for their soil gave me a refreshing and inspiring perspective, and as we continue to prepare for the 2019 Soil Management and Sustainability Summit, and all future projects, I’ll be thinking of those who are working hard to make the best use of what they have – in Canada and beyond.

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Crop Manager West – 9 issues

Mar, Mid-Mar, Apr, June, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $47.50 Cdn. plus tax

Crop Manager East – 7 issues Feb, Mar, Apr, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $47.50 Cdn. plus tax Potatoes in Canada – 1 issue Spring – 1 Year $17.00 Cdn. plus tax All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com • Tel: 800 668 2374

Tackling the complex and critical issue of winter survival in winter wheat.

by Carolyn King

Better winter field survival is a central goal of Prairie winter wheat breeders. However, over the last few decades, making gains in this trait has been very challenging. So a team of researchers is deciphering the genomics of winter survival to further advance the development of varieties that survive and produce good yields no matter what the winter weather is like.

“Norstar is still the gold standard for winter hardiness in winter wheat varieties. It was developed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at Lethbridge back in 1977,” notes Ravindra Chibbar, a professor in the University of Saskatchewan’s department of plant sciences, who is leading this research. “When we started this project, we said if we can develop winter wheat plants that exceed the winter field survival of Norstar then we will consider that we have made a contribution.”

Chibbar identifies two possible reasons why advances in winter field survival have been so difficult. “One is that there may not be enough genetic diversity in the winter wheat germplasm available in Canada. The second factor could be: have we looked at winter survival carefully?”

TOP: Research technician Swarna Ranasinghe collects samples from the plots for lab analysis.

BOTTOM: Research technician Ray Hankie (driving) with Dr. Monica Båga and Dr. Manu Gangola, who are selecting appropriate seed envelopes so the hundreds of lines are seeded as per the plan.

Your local agronomy experts

Richardson Pioneer is committed to working with you at every stage of growth.

At Richardson Pioneer, our CropWatchTM agronomy team has professional agronomists in the field across the Prairies. Our local and regional agronomists work one-on-one with our farm customers to provide product knowledge, crop planning and recommendations tailor-made to each farm.

We’re here to help you make the most of your crop throughout the growing season.

To learn more, visit your local Richardson Pioneer Ag Business Centre or richardson.ca/cropwatch.

Chibbar and his project team are working on this second factor by delving into the genetics and genomics of winter field survival. “Most of the work [done by previous researchers] was related to increasing low temperature tolerance to improve winter field survival. Our hypothesis is that low temperature tolerance is just one of the several factors responsible for winter field survival and that how the plant develops is also equally important. In other words, winter field survival – and the successful production of a winter cereal crop – depends upon increased low temperature tolerance combined with certain developmental traits of the plant,” explains Chibbar, who is a Canada Research Chair in Molecular Biology for Crop Quality.

Through more than a decade of research, Chibbar and his colleagues have developed evidence to show that their hypothesis has a scientific basis. “It is well known that most of the genes controlling low temperature tolerance and vernalization [a plant’s requirement to experience cool temperatures before reproductive growth can occur] in wheat are located on chromosome 5A,” he says. “But we published a paper in 2009 where we showed that regions on other chromosomes also contribute to winter survival.”

In the current five-year project, the researchers are focusing on three key developmental traits: prostrate growth habit, final leaf number, and first internode length. They are working to identify the combination of genes contributing to superior winter survival through these three traits and improved low temperature tolerance. They are also developing DNA markers so breeders will be able to screen their breeding materials for the genes of interest and their combinations.

Chibbar’s project team includes his colleague Monica Båga, a genomics expert in the same department, as well as winter wheat breeder Robert Graf, fall rye breeder Jamie Larsen, and molecular biologist André Laroche, who are all with Agriculture and AgriFood Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge. Project funding comes from the Saskatchewan Winter Cereals Development Commission, Winter Cereals Manitoba Inc., Alberta Wheat Commission and Western Grains Research Foundation, with matching funds from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

The University of Saskatchewan has funded some equipment purchases, AAFC has provided support for internships, and Chibbar receives funding as a Canada Research Chair.

Although winter wheat is the project’s primary focus, the researchers are also working with fall rye. Chibbar explains, “Some rye cultivars are more cold hardy than winter wheat, so it is a good model for a very cold hardy cereal. Although when rye is crossed with wheat to get triticale, it never has the cold hardiness of the rye parent, we can use comparative genomics to determine what makes rye more winter-hardy than wheat. Additionally rye can be used to confirm some of the new hypotheses that we have developed using winter wheat. Our ultimate objective is to duplicate in winter wheat what we have found in rye.”

In one component of the project, Båga is making winter wheat recombinant inbred lines. Such lines are very useful for mapping traits of interest in a plant’s genome because the set of inbred lines captures almost all the genetic diversity available in the original cross between the two parents. Each line is developed by singleseed selections from individual plants for several generations; the plants in different lines are essentially genetically identical to each other with minute changes.

Chibbar says, “The strategy we are taking is to make recombinant inbred lines where there are minute changes in the chromosomal regions of interest. With the help of molecular markers, we analyze the lines to precisely identify the genetic changes in individual lines. The final stage is to determine which of those changes improve winter survival.”

So the research team has been conducting field trials with these recombinant inbred lines, other winter wheat lines and cultivars, and fall rye lines and cultivars for the past four years at Saskatoon, Lethbridge and Vauxhall, to assess winter survival. As well, they are growing the more promising lines in field plots to collect data on grain yield and quality.

The team has already evaluated hundreds of winter wheat and fall rye lines. “Identifying which lines have the best winter survival depends on how severe the weather is, which we can’t control,” he notes. To reliably identify the best lines, they need data from

at least three severe winters. They’ve had two such winters in previous years, allowing them to identify some promising lines that have performed equal to or better than Norstar. They are hoping the winter of 2017-18 has provided the conditions needed to confirm their findings.

As well, the researchers are collecting data on the three developmental traits in the different lines in the field and greenhouse. For the lines that have shown strong winter survival in the field trials, the team will be using a programmable freezing chamber to determine the LT50 temperature – the temperature at which 50 per cent of the plants die from the cold. “LT50 is a precise measure of low temperature tolerance; therefore it can also help in understanding the contribution of low temperature tolerance to winter field survival.”

The researchers are continually working to more precisely locate the regions on the winter wheat genome related to improved winter survival and to refine the markers associated with these locations. The team also includes a graduate student, Hirbod Bahrani, who is genotyping the fall rye materials, identifying genomic regions related to rye’s winter survival, and working on markers associated with those regions.

According to Chibbar, the results from this research could help Prairie crop growers in several ways.

“Winter wheat’s yield potential is about 20 to 30 per cent higher than spring wheat’s. However, at present, producers cannot consistently achieve that higher potential because winter survival

is not consistent. If we can develop varieties that are highly winter hardy, then producers can achieve higher yields,” he says.

The researchers also believe the acres seeded to winter cereals will likely increase as the portion of the Prairies suited to winter cereal production spreads northward, if the climate warms as predicted. As well, since climate patterns are expected to become more erratic in the future, the Prairies will likely have more frequent and more intense freeze-thaw cycles with warm spells that remove the insulating snow cover followed by bitter cold spells that stress the plants. “If we can increase the crop’s cold hardiness, then it should also be able to better withstand these freeze-thaw cycles,” he explains.

Chibbar also points out that winter wheat and other winter cereals are some of the most environmentally friendly crops. “Winter cereals are able to use the very early spring moisture from snowmelt. As well, they tend to require fewer inputs [of herbicides and fungicides]. They grow fast and outcompete the weeds. And the winter crops mature earlier than spring cereals, so they sometimes avoid diseases like Fusarium head blight. Added advantages are that winter cereals prevent soil erosion in the fall and early spring, and provide spring cover for ground-nesting birds,” he says.

“So for producers, growing winter wheat is a win-win situation [economically and environmentally] – if they can consistently produce the crop. Therefore the project’s main goal is to increase cold hardiness and combine that with selected developmental traits to increase winter survival and stabilize yield to develop a ‘climate change-resilient’ winter wheat.”

It’s the little things that make a big difference.

Recycle your containers, grain bags and other ag plastics. Lead the way for the next generation. cleanfarms.ca

Researchers are just beginning to shed light on the impacts of this mysterious crop disease.

by Julienne Isaacs

Few common diseases of field crops in Western Canada are as little understood as aster yellows, a systemic plant disease that impacts cereals and oilseed crops and can have devastating – but hard-to-predict – impacts on yield in bad years.

The disease is caused by the aster yellows phytoplasma (AYP), a bacterium-like parasitic organism that is vectored by aster leafhoppers (Macrosteles quadrilineatus) thought to travel north on jetstreams from continuous cropping systems in the United States.

Symptoms of AYP can be detected in many Western Canadian field crops most years at levels that aren’t economically damaging, but conditions that characterize a “bad” aster yellows year are harder to pinpoint.

According to Tyler Wist, an Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research scientist in field crop entomology based in Saskatoon, the disease seems to run on a cycle – every five to eight years producers will see heavy impacts on yield. In 2012 – the latest aster yellows year – a range of five to 64 per cent of plants were infected per field.

That year, canola producers saw impacts on this scale, Wist says, but producers also noticed problems with wheat. They called the phenomenon a “phantom yield loss” because they didn’t at the time know what had caused it, but the culprit, according to Wist, was most likely aster yellows infection.

Along with colleagues Pierre Hucl, a plant breeder at the University of Saskatchewan, and Chrystel Olivier, an AAFC research scientist, Wist recently wrapped up a three-year project looking at aster yellows in spring wheat. The project sought to document symptoms of the disease in wheat cultivars, compare cultivar susceptibility and estimate disease incidence.

The team compared about 25 wheat lines out in the field, Wist says, but most of them did not exhibit much symptom expression when infected with aster yellows; most wheat seems to be fairly resistant, with durum showing slightly more susceptibility.

Hucl says out of the three years of the study, there was heavy

ABOVE: Aster leafhoppers are tiny in comparison to the plants they feed on.

infestation in only one year, but even under those conditions the differences weren’t that great between common wheats and durum.

To boot, most of the symptoms of aster yellows infection in wheat noted by the researchers are also symptoms of other diseases or common crop problems. “We didn’t see any symptoms that we could conclusively say were due to aster yellows,” he says.

In other words, the study did not yield much in terms of recommendations for producers, Hucl says, but the data adds to researchers’ longer-term understanding of how the disease works.

Symptoms of aster yellows infection in wheat, when they do occur, can include plant death, stunting of plants, a reduced number of tillers, bleaching of the tillers and heads, twisting of awns and premature yellowing.

The aster yellows in cereals project followed on the heels of work completed in 2016 by Olivier identifying aster yellows symptoms in canola and camelina.

Brassicas are more susceptible than cereals to aster yellows, and symptoms in these crops are more obvious – and bizarre. In oilseeds, the disease attacks the growing regions of the plant and turns floral parts green. “Things that aren’t leaves start looking like leaves,” Wist, who also worked on Olivier’s project, explains. “There are effects on the seeds too – one symptom is that they tend to sprout inside the pods.”

Beyond identifying symptoms, Olivier’s project also helped pinpoint conditions that are ideal for aster yellows infection in canola: three or four leafhoppers, which need to be carrying AYP, must feed on a single plant for up to 10 hours to transmit enough phytoplasms to infect the plant. Young plants are more likely to be infected, and the problem is exacerbated by wet conditions.

Because symptoms and conditions conducive to the disease are less obvious for wheat, researchers are looking for ways to render aster yellows less of a “phantom.” One method is to analyze the movements – and alternate hosts – of aster leafhoppers, Wist says.

Leafhoppers do not move very far once they have found a good place to feed, and their patchy feeding in canola leads to similarly spotty distribution of aster yellows symptomatic plants in fields. Though symptoms are more obvious in brassicas, aster leafhoppers don’t reproduce in canola but in cereals: thus, Wist says, higher

populations of the insect can be found in canola near cereals.

A new project funded through SaskCanola will look at alternate hosts for aster yellows, including weeds, he says. “Down in the States they’ve shown that perennial weeds can be the reservoir for aster yellows. Up here, if they start feeding on a weed that has aster yellows and aster yellows has come back up from the root, you can get aster yellows moving into the crop plants.”

Another project funded by Western Grains Research Foundation set to begin this

INTERIOR EPOXY COATING (on Magnum-F™ )

INDUSTRIAL GRADE COATING FOR SUPERIOR FINISH

PRESSED CONE SHEETS FOR OPTIMUM STRENGTH INSPECTION HATCH

RACK & PINION SLIDE GATE (Stainless Steel Components on Magnum-F™)

year will attempt to understand source populations and leafhopper dispersal.

Understanding alternate hosts can help producers get a sense of a potential aster yellows problem, Wist says, particularly if they find leafhoppers in ditches near crops early in the season.

But as spraying for aster leafhoppers is not recommended by researchers, the best control is to plant resistant varieties – and to keep an ear to the ground as new research projects turn up new information about aster yellows.

CUSTOMER DRIVEN SMOOTHWALL SOLUTIONS 888.WESTEEL (937.8335) | info@westeel.com westeel.com

6" SIGHT GLASS

LADDER & OPTIONAL WELDED SAFETY CAGE POKE HOLE (on Magnum-F™ )

HEAVY-DUTY CONSTRUCTED FOUNDATION (Varies Depending on Model)

CUSTOM OPTIONS AVAILABLE

New recommendations suggest spring wheat planting dates could be earlier.

by Julienne Isaacs

According to a new study out of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Lethbridge Research and Development Centre, most spring wheat could go in the ground earlier than traditional planting date recommendations would suggest.

Research scientist Brian Beres initiated the study in 2015 to compare differences between spring wheat cultivars and coldtolerant spring wheat cultivars when planted into a range of soil temperatures in one experiment, and to assess the response of cold tolerant wheat lines to changes in agronomic management in a second experiment.

It was inspired, says Beres, by a trip to Montana in late March. From the road, he could see producers prepping for seeding and even some seed drills already in motion.

“I thought, ‘This is what we should be doing – pushing our systems and asking when the soil is ready to take the seed on, rather than thinking about a date,’ ” he says.

Most producers are used to planting based on dates, says Beres, but researchers aren’t any better. “Most publications give prescriptive dates when summarizing a seeding date study. That gives you a snapshot of when the study was conducted, but you can’t predict from one year to the next what May 10 is going to be like,” he says.

Crop insurance providers also lean heavily on dates as a measure of whether or not fields should be insured.

“The old myth was that if you got in too early that seed would just sit there and rot,” says Beres.

Beres’ study, which was funded by Alberta Innovates, Alberta Wheat Commission and the Western Grains Research Foundation, set out to look at whether the team could couple alternative genetics – meaning wheat lines more tolerant to cold soils – with alternative planting practices, using soil temperature as the trigger for planting rather than a date.

What they found was that though most recommendations cite a soil temperature of 10 C to be optimal for seed growth, both the cold-tolerant wheat lines and regular CWRS spring wheats performed well when planted in soils as cold as 2 C in the top five centimetres of soil.

In fact, Beres’ team saw a yield drag when wheat was planted closer to so-called “optimal timings” of 6 C to 10 C.

Study setup and results

The study was set up at four sites over three years – Edmonton and Lethbridge, Alta., Swift Current, Sask., and Fort St. John, B.C. The conventional check variety used in the study was AC Stettler and Conquer VB in Lethbridge.

Seeding was performed at six soil temperatures – 0 C, 2 C, 4 C, 6 C, 8 C and 10 C.

Preliminary results to the first part of Beres’ experiment indicate that seeding very early did not result in yield losses, but seeding

between soil temperatures of two and six degrees resulted in the most stable yields.

The second part of Beres’ experiment, evaluating cold tolerant line response to agronomic management, compared seeding times based on soil temperature triggers – at 0 to 2.5 C, 5 C, 7.5 C and 10 C – as well as varying seeding rates (200 and 400 seeds per square metre) and depths (2.5 and five centimetres).

Preliminary results from the second experiment suggest that seeding early did not result in yield losses, and in fact sometimes resulted in a yield advantage. In addition, the higher seeding rate at earlier planting dates increased yield potential.

In both experiments, cold-tolerant lines did not outperform conventional lines.

Beres says early planting has many benefits. The most obvious is that producers can get on their fields earlier, which is a plus as farm sizes continue to increase.

But it also acknowledges the reality that the climate is changing. Farmers have received Beres’ research positively at grower meetings, and they say planting is possible earlier than it was generations ago. “You could find general agreement that the climate is changing and it’s changing in a way that’s going to force us to adapt our practices,” says Beres. “While this strategy won’t work every year in every location of the Prairies, it is a step in that direction.”

A second phase of the project is underway, funded by the Alberta

Wheat Commission and led by PhD student Graham Collier under co-supervision by Beres and the University of Alberta’s Dean Spaner, that will look at other agronomic factors to the early planting system, including fall-applied residual herbicides for early season weed management, nitrogen sources and application timings, and the identification of conventional varieties suited to ultra-early planting.

Collier will identify genes that perform equally well or better at early seeding as conventional seeding dates, which could be used in future breeding programs.

Results from this second phase should be available in 2020.

But Beres says there’s no need to wait for a cold tolerance trait to apply his research. “The registered cultivars as represented by AC Stettler indicate that you can go ahead and plant early with minimal risk even with what’s available today,” he says.

Producers who choose to plant early should use a dual fungicide/ insecticide seed treatment to help protect seed from abiotic stress.

“You need that package where you’re using soil temperature as a trigger point but your system includes a good seed lot packaged with a good fungicide/insecticide seed treatment and planted at optimum seeding rates,” Beres says.

Unknown nitrogen inputs help balance nitrogen removals.

by Bruce Barker

Times change and so do cropping practices, but centuryold cropping system experiments continue to give back, thanks to the foresight of researchers who established and maintained the plots for more than 100 years. A recent analysis of nitrogen (N) inputs and removals found a surprising result in a long-term study in Lethbridge, Alta. Nitrogen removal in three different wheat rotations could not be solely attributed to N fertilizer or mineralization.

“Calculating N budgets offers invaluable clues about whether systems are losing or gaining N, the possible routes of any losses, and the practices that might best improve efficiency,” says Rezvan Karimi, an Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) researcher in Lethbridge.

Karimi and colleagues dug into long-term wheat rotations at AAFC Lethbridge on a site established in 1911 on recently broken land. The experiment includes three cropping systems of continuous wheat (W), fallow-wheat-wheat (FWW), and fallowwheat (FW).

No fertilizer was applied to any of the plots until 1967, when an N fertilizer treatment (45 kilograms of N per hectare as ammonium nitrate) was first applied to a strip running the length of each plot. Beginning in 1972, a phosphorus (P) fertilizer treatment (20 kilograms of P per hectare as triple super phosphate, 0-45-0) was similarly applied in strips to each plot. Phosphate was applied with the seed in the seedrow and ammonium nitrate was broadcast.

Karimi’s research objective was to assess the long-term effect of management practices on soil N content, grain yield, and N budget. Karimi says the study is unique in that it allowed them to estimate N losses or gains during a century of agricultural production, spanning virtually the entire time from initial cultivation of the soil to the present day.

Moldboard plow and disc implements were used in the early years, and replaced by the wide blade cultivator in 1939 when stubble mulch practices were adopted, says Karimi. In recent decades, tillage has been progressively reduced but has been used in some years for seedbed preparation and herbicide incorporation. All straw above the cutting height was removed from the plots during stoking of sheaves until 1943 when combine harvesters were first used.

Karimi says the original scientists had remarkable foresight

Long-term rotation yields, presented as five-year moving averages, in unfertilized subplots of the historical ABC rotations from 1912 to 2014*.

*Rotation designations are as follows: W, continuous wheat; FW, fallow-wheat; FWW, fallow-wheat-wheat. Rotation yield refers to the average yield across all phases of the rotation, including the zero yield during the fallow phase. The fallowwheat-wheat system was fallow-wheat-oat until 1923.

Source: Karimi et al., 2017.

and collected and archived soil samples in 1910, just prior to or shortly after the initial breaking of the sod. Since that time, soil samples have been collected and archived roughly every 10 years.

In 2015, the total N and organic C concentrations of archived samples was analyzed, spanning a complete century from 1910 to 2011, to ensure consistency of analytical techniques. These analyses allowed the researchers to look at changes in N fertility and organic matter over the past 100 years.

Rotation grain yields, without added fertilizer, were virtually identical among systems from 1911 to 2014. Plot yields after fallow were almost two times greater than after wheat, largely because moisture and soil nitrate accumulated during the fallow year, so that the yield response to fallow offset the loss of yield during the fallow year. This resulted in rotation yields (average of cropped and fallow phases) that were minimally affected by fallowing.

Despite appreciable year-to-year variability, grain yield in unfertilized subplots showed a general increasing trend over the first eight decades of the experiment, likely because of improvements in weed control, crop varieties, and other cultural advances. In the last 20 years, yields have generally declined, partly because of problems with weed control and unusual precipitation patterns in selected years. However the evidence also points to growing N deficiency in these unfertilized plots because of a decline in organic matter and lack of N mineralization, Karimi says.

Conversely, yield response to N increased over time, especially under continuous cropping and when P fertilizer was also applied.

The N balance was calculated for two time periods: 1911-1966 and 1967-2014, corresponding to the time before and after inception of N fertilizer treatments and roughly 50-year segments. Changes in soil N were calculated for the surface 0 to 15 centimetres, the layer of soil most prominently affected by cropping.

For the first half-century (1911-1967), N removal was approximately equivalent to the loss of soil N in the surface 15

centimetres; the net removals were almost exactly balanced by losses of soil organic N. In effect, an amount of N roughly equivalent to mineralized N was absorbed and removed by the growing crops.

The N balance for the post-1967 time period, however, tells a somewhat different story, Karimi says. By this time, the soil organic matter had more or less reached a steady state, so there was now no appreciable net contribution from mineralization of organic N. During this second time period, removals of N in grain exceeded N fertilizer inputs by approximately 20 to 30 kilograms of N per hectare per year. The origins of this unaccountable N remain uncertain, but are likely from outside sources, perhaps partly from atmospheric ammonia (NH3), Karimi says.

Karimi says the outside source relevant to this study may be the intensive livestock operations that were located upwind of this experiment. Measurements of NH3 deposition in southern Alberta, prompted in part by the N imbalance in these long-term plots, show large fluxes of NH3 emitted from beef feedlots, and significant deposition of this NH3 downwind of these sources.

“Most likely, the apparent non-fertilizer N input into these long-term systems reflect multiple sources, including precipitation and dry deposition. Regardless of their origin, our study indicates that the N balance of a cropping system cannot be considered in isolation of N dynamics in surrounding ecosystems,” Karimi says.

Karimi also noted that over the last half century, cumulative recoveries of N fertilizer in harvested grain ranged from 11 per cent for fallow-wheat to 40 per cent for continuous wheat without P fertilizer and 58 per cent in continuous wheat with P fertilizer. She says the other 40 per cent of N unaccounted for does not appear to be accumulating in soil organic pools in the top 15 cm, based on their soil analysis. Karimi says 60 per cent recovery is typical of other Canadian studies with nearoptimal nutrient amendment rates.

“This study demonstrated the importance of long-term experiments, despite some shortcomings, in evaluating the N balance of cropping systems, and indicated the potential significance of nonfertilizer N inputs from outside sources in such ecosystems,” Karimi says.

by Bruce Barker

It has been a roller coaster ride for winter wheat over the last 40 years. Seeded-acreage of 1.25 million acres in 1985 was followed with acreages in the low 100,000s during the 1990s, followed by another peak of 1,370 million acres in 2008 dropping to 410,000 acres in 2017. Where does winter wheat go from here?

“The advantages of growing winter wheat are still pretty much the same,” says Brian Fowler, a professor in the department of plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan. “The biggest problem is getting winter wheat into the rotation.”

Fowler is a longtime winter wheat plant breeder and proponent. He says that while winter wheat genetics have overcome many of the earlier challenges of disease resistance and winter hardiness, seeded acreage has been a moving target, partially related to projected net returns and partially due to seeding logistics.

“The whole agricultural profile has changed. Farms are bigger and the growing season is getting longer. Farmers are growing later maturing spring crops that yield higher, so they don’t have as much flexibility to take time out of harvest to seed winter wheat,” Fowler says. “And those higher-yielding spring wheat crops have lower protein which starts to put them in competition with winter wheat.”

Paul Thoroughgood, an agrologist with Ducks Unlimited, agrees that seeding winter wheat in early fall can be a challenge. He says it takes another level of management to seed while there may be crop left to harvest. Another change at the farm level is that growers now use the same tractor to pull grain carts as they use to pull the air drill to seed a winter wheat crop. That adds an additional layer of logistics.

“I still contend that the first time you get winter wheat into the rotation is the hardest. After that, you are harvesting some of your acres in August, and that takes pressure off the rest of the harvest,” he says.

Thoroughgood offers another interesting perspective on winter wheat attitudes. If a durum wheat grower has a crop failure, because of something like Fusarium head blight that devastated the crop in 2016, they will still grow it again. But if they have a bad experience with winter wheat, first time growers are less likely to try it again. He cautions growers who have some winterkill in 2018 to recognize that it was an unusually tough winter. “I think a lot of concern people have regarding winter kill, overall, is misunderstood,” Thoroughgood says. “That is

ABOVE: Winter wheat has had ups and downs in production over the last 40 years.

probably an unnecessary concern except in rare years.”

Certainly, economics is a driving force behind the decision to grow winter wheat. Thoroughgood keeps a projected average profit per acre comparison of spring, CPS, winter wheat and durum wheat based on provincial crop planning guides. These government guides use estimated costs and returns as the basis for crop planning. While yields, commodity prices and expenses vary, Thoroughgood says that winter wheat has performed well against the other wheat varieties. Over the long term, winter wheat has generally provided a higher net return than the other wheat classes.

However, Thoroughgood cautions that farmers need to look carefully at the planning guide numbers and use their own projected revenue and expenses. For example, the commodity price used for winter wheat varies across the three Prairie planning guides from $4.59 in Saskatchewan to $4.85 in Manitoba. He says farmers should look to local markets and go beyond just their local elevator to see if they can get better prices. He says in early spring 2018, a local ethanol plant was contracting for $5 per bushel. On a 70-bushel winter wheat crop, an extra 50 cents per bushel adds up quickly – $35 per acre more.

A crystal ball also helps. With a large amount of medium protein grain in the western Canadian market from the 2017 spring wheat harvest, winter wheat prices have been discounted in the milling market.

“One major problem is market access. Prices south of the border are higher. We used to blame the Canadian Wheat Board for only marketing high-protein wheat, but that doesn’t seem to have changed with today’s grain marketers,” Fowler says. “There is a large established market for a wide range of quality types that could be tapped into if a competitive winter wheat production system could be put in place in

Canada.”

Thoroughgood says Canadian winter wheat growers along the U.S. border have been shipping grain south to take advantage of those higher prices. He isn’t sure whether the grain buyers there are discounting winter wheat less than in Canada, or if they are better at capturing the lower protein wheat markets. The low Canadian dollar has also helped with growers shipping to the U.S.

The other side of the net revenue equation, cost of production, favours winter wheat. A wild oat herbicide is seldom required. Winter wheat usually matures before wheat midge infestations so insecticide isn’t usually required. In some years, winter wheat also matures prior to Fusarium head blight infection.

Again, the provincial crop planning guides take different approaches to estimating expenses per acre. Saskatchewan, for example, takes an all-in approach for weed control, with an estimated cost of $62.93 per acre, while Alberta and Manitoba come in at $13.72 and $13.83 respectively.

Setting aside the measurable economic returns, Fowler and Thoroughgood both say there are other benefits that aren’t easily measured economically. Ecological and conservation benefits are high on the list. Soil conservation benefits are hard to measure. Helping to manage herbicide resistance may be measurable but varies by the status of herbicide resistance on each farm. Earlier, more timely harvests are advantageous, but seeding during harvest is a drawback. Fewer disturbances for waterfowl and upland game birds are an important ecological benefit.

“Farmers don’t get paid for ecological benefits in Western Canada, but that might change at some point,” Fowler says.

A new smartphone app called Mobile-IPM is available to help farmers identify weeds and problem insects in their fields. A collaborative effort between university, government and industry partners, the app includes such functions as pest forecasting and pest identification.

BY Mark Halsall

These days, many farmers rely on fast, convenient access to information to help them make the best management decisions for their crops. Now there’s a new tool called Mobile Integrated Pest Management (Mobile-IPM) that’s designed to make the often-challenging process of identifying crop threats much easier.

The free smartphone app was released in March and is available on iTunes and Google Play. A desktop version of Mobile-IPM also will be released soon.

“I think it will be received quite well by agronomists and farmers,” says John Gavloski, an extension entomologist with Manitoba Agriculture, who has collaborated on the app since 2014.

“The promise it holds is that it can make production more economical,” he adds. “You can save a lot of money by making wise pest management decisions, and there’s much decision-making that can be done through using an app.”

Mobile-IPM was developed through a joint venture involving university and government partners, along with the Western Grains Research Foundation. Barbara Sharanowski, a former University of Manitoba professor who now teaches entomology at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, Fla, leads the $1-million project, which is wrapping up this year.

“It’s really been a huge collaborative effort,” says Sharanowski, who first came up with the idea for the app six years ago while working at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

“There is a real host of things that you can do with mobile technology that provides information for farmers,” she says. “Mobile-IPM is one more tool that people can use to help them make good pest management decisions for integrated pest management.”

Gavloski agrees: “Step one in integrated pest management is knowing what you’re dealing with, so it will help in that regard.”

Mobile-IPM features three interactive components: an identification tool for insects and weeds, a real-time pest monitoring and forecasting tool and a crop management tool.

The pest ID tool in Mobile-IPM currently enables growers to identify insects in their wheat and canola fields, although there is the potential to add more crops in the future. Growers can also use it to identify problem weeds in field crops.

The system is based on a question-andanswer model that takes the user through an identification process where they can input information about the appearance of the pest and other factors such as weather conditions and the type of crop damage.

Growers can also take a picture of the pest and compare it to pictures in the Mobile-IPM database, and if they need further assistance, the app provides links to local agronomists and entomologists who may be able to help.

Once the grower has confirmed the identity of an insect threat, the app has a guide to more information about how to manage the pest threat, including registered insecticide and herbicide listings and suggestions for cultural or biological control measures.

Mobile-IPM also provides economic thresholds for pests, which, as Gavloski points out, can be a great help in facilitating best practices for integrated pest management.

“By using economic thresholds, we can reduce unnecessary pesticide applications,” he says. “This reduces pesticide costs, and the reduced use of broadspectrum insecticides enables predators, parasitoids and pollinators to continue working in the field.”

The pest forecasting tool in Mobile-IPM offers real-time monitoring and forecasting and produces risks maps for potential insect outbreaks that are based on pest reports and data generated by growers, agronomists and provincial extension and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada staff.

The forecasting component of MobileIPM is currently focused on Bertha armyworm, one of the most destructive pests of canola in Western Canada. Each time Bertha armyworm counts are done by users, levels of the insect presence will be added to the Mobile-IPM database – enhancing the app’s ability to track and predict an outbreak of the bug as it develops.

The crop management tool in MobileIPM allows farmers to keep a history of pests in their fields and how they’ve dealt with them, so they can make better management decisions in the future based on what’s worked the best.

According to Sharanowski, growers can also track almost every activity that’s been done in field, including planting

and harvest dates, seeding rates, variety choices and crop rotation history. Information on crop storage and farm finances can also be recorded and tracked.

Mobile-IPM was developed with the help of numerous extension entomologists and plant pathologists in several provinces, but its forecasting component only pertains to Manitoba at the moment. In an effort to broaden the app’s potential usage, Sharanowski is currently seeking permissions from the Alberta and Saskatchewan governments to include their

ag data in the Mobile-IPM system.

Gavloski is hopeful that the other Prairie provinces will eventually participate in Mobile-IPM. “It will certainly become part of our extension messaging once it’s out,” he says. “We’re hoping that we can do a good job promoting it and showing its value to growers and agronomists, and then once we’ve done that hopefully more people will jump on board,” he says.

The Mobile-IPM app is available for download on Google Play and iTunes App Store and at mobile-ipm.com.

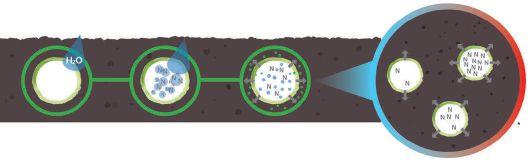

Too much early-season nitrogen (N) encourages lodging, depletes soil moisture and leaves less N for seed production. ESN technology controls N release, reducing N loss and increasing N efficiency. Additionally, it significantly reduces N loss to the environment.

ESN technology and increased yield

When compared with similar N treatments of urea or UAN, using 50-75% of N with ESN technology has shown an average of 8-10% increase in canola yield. This data is derived from a number of independent research studies conducted at various locations in Western Canada.

Unmatched seed safety

Applied at rates up to three times higher than conventional N fertilizers, ESN won’t harm growing seedlings (following safe rate guidelines and recommended percentages of ESN).

Wider application window

ESN provides a wider application window in both the spring and the fall, allowing you to apply fertilizer on your schedule.

Convenient to use and apply

ESN is compatible with no-till operations and is easy to blend. It will not set-up in storage and therefore has a longer shelf life.

Environmentally responsible ESN significantly reduces N loss, providing substantial benefits to the environment.

Minimize N Loss. Maximize Yield. Learn more at SmartNitrogen.com

Imagine getting a phone call from your canola crop, telling you there’s a sclerotinia problem in the field and help is required. That may sound a little far-fetched, but it may not be far off. A researcher in Alberta has developed a way to allow remote detection of sclerotinia detection to act as an early warning system.

BY Bruce Barker

Call Susie Li a dreamer, but the researcher at Alberta Innovates Technology Futures at Vegreville, Alta., has developed a way for a tiny nano-biosensor to monitor sclerotinia spore levels in canola and alert a grower with a telephone call. This may sound like science fiction, but Li has already proven that the concept works and is now verifying the technology in the greenhouse and canola fields, and moving the technology to a small device that can be easily applied in the field.

“The current method of forecasting for sclerotinia is with a checklist of questions in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and a risk assessment in Manitoba. But the checklists and risk assessments are not always reliable because of sudden weather changes,” Li says. “We wanted to develop a different way of predicting sclerotinia risk using technology that is available in other industries.”

Li’s solution is a combination of an in-field biosensor that can detect sclerotinia spores in real time that is linked to a signal transmission device that can call or text a cell phone. In order for the concept to work, the biosensor had to be able to specifically detect sclerotinia spores and correlate the number detected to the level that would cause the development of the disease.

“The biosensor technology is new but has been used in other areas. It was developed for applications in medicine, where it could detect DNA proteins and identify problems like diabetes,” Li says. The first part of the proof of concept was to be able to detect the spores through the development of an antibody specific to sclerotinia. An antibody recognizes the molecules used to produce a disease and blocks them in a way similar to antibodies used in influenza vaccinations. The antibody was placed on a nano-sensor and tested for sensitivity in the lab, where it detected sclerotinia spores down to levels as low as five spores.

“We thought this level was low enough for our design. The next thing we needed to know was how many spores are required to trigger a disease outbreak,” Li says.

In the greenhouse, various spore collection fluid samplers/traps were evaluated, and the Versa Trap from SKC Inc. was selected. Canola plants were grown in the growth chamber along with a jar of sand containing germinating sclerotia. Spores were collected in the trap and fluid transferred to the biosensor for spore detection. At the same time, the plants were monitored for the disease. Liquid samples from the spore trap were plated every 24 hours to identify disease development. Li was able to correlate that 10 sclerotia spores per millilitre collected in 24 hours in a 3.3-square-metre growth chamber started to cause leaf infection.

An additional step was to take the biosensor readings and convert them to an electronic signal transmission. Researchers at the University of Alberta accomplished this process using Bluetooth technology. The signal transmission process has already been established in the lab. When spores are detected, the level of spores detected influences the electrical conductivity on the biosensor. Higher conductivity results in a stronger signal sent over Bluetooth.

In 2016, Li started working on verifying the specificity and accuracy of the biosensor in the greenhouse and in canola fields over three years. She needs to know how big of an area one sensor can cover, the number required in a field, and how to make the technology work on an economic basis. “More work needs to be done to improve the sensitivity and lowering the detection limit. That is what we are working on right now,” Li says.

A tale of two years.

by Bruce Barker

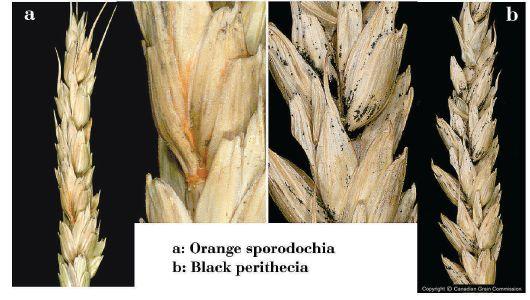

It was the best of times and the worst of times. The year of 2016 was certainly one of the worst of times for Fusarium head blight (FHB). High FHB incidence and severity was widespread across the Prairies, with durum wheat hit especially hard. By contrast, 2017 saw much lower levels of FHB across the Prairies. The difference?

“Dry and warm conditions really helped limit Fusarium head blight development across the Prairies in 2017,” says Kelly Turkington, an Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) pathologist in Lacombe, Alta.

Information from the Canadian Grain Commission’s annual harvest sample program illustrates the difference weather can make on FHB incidence and severity. Comparisons between 2016 and 2017 show greatly reduced FHB in 2017.

For comparisons of incidence and severity by provincial crop district going back to 2003, go to the Canadian Grain Commission website for more detailed data on red spring wheat and durum wheat samples. (http://www.grainscanada.gc.ca/str-rst/fusarium/ data/fdkmenu-en.htm)

The percentage of FDK is an important grading factor in wheat. In 2016, the average CWRS wheat sample submitted to the CGC would have graded a No. 3 in Manitoba and Saskatchewan and No. 2 in Alberta. Durum would have graded Sample in Saskatchewan and No. 3 in Alberta.

The difference in disease levels between 2016 and 2017 is a textbook example of the disease triangle. For a disease to develop, there needs to be a susceptible host, a favourable environment and sufficient quantities of a virulent pathogen, when combined can result in the development of a disease. In 2017, taking away the favourable environment resulted in greatly reduced FHB levels.

The one factor farmers can’t control is the weather. The exception is irrigated crops where limiting irrigation just prior to and

Source: Canadian Grain Commission.

during the heading period may help to lower FHB. For dryland production, pathologists recommend that farmers focus on the other two aspects of the disease triangle – susceptible host and the pathogen.

For wheat growers, selecting a variety with FHB-resistance is the first step in helping to manage the disease. CWRS wheat growers have a fair number of varieties available with a Moderately Resistant (MR) rating. A few MR varieties are available in the CPSR and CWSP wheat classes. In the CPSR class, AAC Tenacious VB is

rated as Resistant to FHB. Similarly in the CWRW winter wheat class, Emerson is rated as Resistant. In the other wheat classes, including durum, the best resistance rating is Intermediate, which can still offer some reduction in FHB under lower disease levels, and may help improve fungicide control.

The impact of selecting the best resistance package was illustrated in research done by AAFC and the University of Manitoba. Field trials were conducted under natural infection and artificial inoculation from 2012 to 2014 at seven sites across the Prairies. The researchers looked at four wheat varieties with different resistant ratings, and the impact of seed treatment and foliar fungicide application on FHB and yield.

In the research, Anita Brûlé-Babel and Zesong Ye of the University of Manitoba, and colleagues from AAFC including Rob Graf, Rob Mohr and Brian Beres found that under higher FHB pressure, Carberry CWRS and Emerson CWRW had superior FHB resistance with reduced FDK and DON levels and higher yield. Carberry is rated Moderately Resistant and Emerson is rated as Resistant. The susceptible varieties Harvest (moving to CNHR wheat class on August 1, 2018) and the CWSP variety CDC Falcon had higher levels of FDK and DON.

Additionally, winter wheat had overall higher yields with Emerson yielding the highest and most stable across environments. Winter wheat matures earlier than spring wheat, and may have grown past the infectious flowering stage when Fusarium infections occur.

Seed treatment alone did not reduce the impact of FHB. However, it did increase winter wheat stand establishment and overwinter survival. Test weight was higher for both winter wheat varieties, and seed treatment increased kernel weight in Emerson. While Fusarium-infected seed does not directly correlate to FHB, using good quality seed that has been treated with a seed treatment produces a uniform crop stand that helps with fungicide timing application.

Foliar fungicide application and crop rotation are factors that farmers can control to help manage the pathogen in the disease triangle. In Brûlé-Babel’s research, foliar fungicide application, with or without a seed treatment, generally produced higher yields with greater stability, especially with more susceptible varieties when FHB pressure was high.

In other University of Manitoba research in 2011, Brûlé-Babel says that foliar fungicide application was more effective in reducing FHB, FDK and DON levels with moderately resistant varieties, while the response to fungicide application in susceptible varieties was much less. She says that farmers should first spend money

on the best FHB-resistant varieties, even if they are going to spray a fungicide.

Crop rotation can also manage the FHB pathogen. The pathogen can survive on crop residues of corn and small-grain cereals such as wheat and barley.

“From a pathologist perspective, a two year canola/cereal rotation that is common on the Prairies is simply not long enough for decomposition of any crop residues that may be carrying residueborne diseases like cereal leaf spots and Fusarium head blight,” Turkington says. “It is simply not enough time.”

Crop rotation should have at least a two-year break in cereals and corn to help reduce pathogen survival. Additionally, avoid planting cereals adjacent to fields that had significant FHB infection in the previous year.

Projecting what FHB levels in 2018 goes back to the disease triangle. What happened in 2016 provides clues for how the disease may progress in 2018. For farmers in a two-year rotation of canolawheat, the 2018 FHB potential is serious. A wheat field that was heavily infected with FHB in 2016 will have a heavy pathogen load going into 2018. Seeding that field back to wheat or another susceptible cereal crop in 2018, even after a one-year break with canola or pulses, will have an elevated risk for FHB.

“The heavy disease load in 2016 will have survived on crop residue. So what happened in 2016 will give you an idea of what might potentially happen in 2018, if weather conditions favour Fusarium head blight,” Turkington says.

KWS DANIELLO HYBRID FALL RYE

N High Yielding

N Lowest Ergot Risk

N Very Good Lodging Resistance

N Suitable for dryland or irrigation

N Very High Falling Number for Milling Markets

GUTTINO HYBRID FALL RYE

N High Yielding

N Very Good Lodging Resistance

N Highest Falling Number for Milling Markets

AAC GATEWAY WINTER WHEAT

N Good Yield

N Excellent disease package

N High protein

N Excellent milling characteristics

Our members can supply all your seed needs

Presented by Josef Soukup, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, at the Herbicide Resistance Summit, Saskatoon, Feb. 27-28, 2018.

The first resistant population identified in Europe was a pigweed resistant to atrazine in Austria in 1973. Later on through the 1980s and 1990s, many weed species developed resistant to PSII inhibitors (Group 5), mostly to atrazine. More recently, there has been a dramatic increase in resistance to ACCase (Group 1) and ALS (Group 2) inhibitors in grasses since 1990. Resistance to ALS herbicides has been confirmed since 2000 in broadleaved weeds like mayweed and wild poppy. Resistance to glyphosate (Group 9) has also developed in permanent crops like orchards and vineyards in the Mediterranean since 2000. Glyphosate resistance is the major problem in the Mediterranean.

The most important crops affected by resistance are cereals. For Europe, the weedy grasses – blackgrass, silky bent grass, wild oats, Italian ryegrass, and brome species – are the problems. The area affected is about 10 million hectares. Compared to Canada, with roughly 15 million hectares affected by resistance, the area is very comparable, but we have twice the area of arable land.

Some smaller areas are affected by resistance in broadleaved crops, such as sugar beets and vegetables. The area is less than one million hectares. In other summer crops, there are different weed problems, again, grasses – barnyardgrass and Johnson’s grass – in corn and also in sugar beet.

The most important weed in cereals for Europe is blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides), especially in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. It affects the crop once established in the fall, and is very competitive at tillering, overwinter, and in the spring. High infestation can result in 80 per cent yield loss. In United Kingdom and France, about 80 per cent of populations are resistant. In Germany, about 50 per cent of populations are resistant, usually to ACCase inhibitors but also ALS inhibitors. There is also resistance against the newer products like mesosulfuron (Group 2) and pyroxsulam (Group 2). Farmers must now once again include soil active herbicides, such as prosulfocarb (Group 8) and flufenacet (Group 15) that are applied in the fall.

Status of resistant species in Europe

Cropping system Resistant speciesModes

Cereals (>10 Mio ha affected)

Blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides)

Silky bent grass (Apera spica venti)

Wild oats (Avena fatua, A. sterilis)

Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum)

Brome spp. (Bromus sterilis, B. diandrus)

Wild poppy (Papaver rhoeas)

Mayweed (Tripleurospermum perforatum)

Chickweed (Stellaria media)

Cornflower (Centarea cyanus)

Corn, sugar beets, vegetables (<1 Mio ha affected)

Barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli)

Johnson´s grass (Sorghum halapense)

Redroot pigweed, lamb‘s-quarters, black nightshade … (Amaranthus retroflexus, Chenopodium album, Solanum nigrum)

Mediterranean vineyards and orchards

(~ 0,1 Mio ha affected)

Rice (including Turkey)

(~ 0,1 Mio ha affected)

Fleabane spp. (Conyza canadensis, C. bonariensis, C. sumatrensis)

Ryegrass (Lolium rigidum, L. perenne)

Barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli)

Red rice (Oryza sativa var. sylvatica)

Rice sedge (Cyperus difformis)

Managing resistance isn’t about using less glyphosate; it’s about using herbicides effectively. Here’s how:

Mixtures work best. Tank mixes have been shown to be more effective than alternating single-mode applications (AKA rotating herbicides) when it comes to managing herbicide resistance.1

Tank mix at least once per growing season. Add another effective mode of action to the tank with glyphosate. 31

Take advantage of pre-seed options. It’s your easiest opportunity to include a tank mix in your herbicide program.

Group 1 and 2 herbicides are considered high risk, as many weed species are resistant to these herbicides. Using them can put more pressure on glyphosate to control tough weeds such as kochia, wild oats and cleavers Don’t rely solely on glyphosate or any one mode of action to control them.

Grow three or more different crops in your rotation. It can help break cycles of disease, insects and weeds and give you more herbicide options.

Weeds outsmart habits, not systems. Herbicide-tolerant crops don’t cause resistance. The way we use them can. Visit MonsantoCMS.ca for more resistance insight and chemistry recommendations.

1 Beckie and Reboud, 2009. Selecting for Weed Resistance: Herbicide Rotation and Mixture. Weed Technology, 23: 363-370

2 AgData 2015, Glyphosate BPI Report

46% of glyphosate is used at preseed. Of those applications, 69% is applied alone2, which puts farmers at risk for selecting for resistance.

Resistant species in Europe and Canada – a comparison

Weed Canada Europe

Wild oat No. 1 in Canada, often multiple resistance

Green foxtail

Very frequent multiple resistance

Kochia Very important multiple resistance

Canada fleabane

Very important multiple resistance

Common weed but manageable, rarely resistant

Locally, hard to control

Rare weed, not on agricultural land

Only in permanent crops, non-agricultural land

Wild buckwheatTroublesome, resistantFrequent, no major problem

Cleavers Increasing, resistanceFrequent, but no major problem

BlackgrassVery rare No. 1 in Europe, frequent resistance

Silky bent grassExotic, very rareIncreasing range and resistance

Barren bromeVery rare on arable landSpreading, evolving resistance

Wild poppyVery rare Evolving resistance

Silky bent grass is in Central and Northwestern Europe. Resistance to ALS is the most frequent with some ACCase resistance occurring. Fortunately, our soil herbicides like flufenacet, prosulfocarb, and chlorotoluron (Group 7) are effective on these resistant populations. One population in Czech Republic in 2017 was confirmed to be resistant to three modes of action, ALS, ACCase and PSII herbicides.

Ryegrass is a typical problem of the ocean climate – United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Usually, it is the Lolium multiflorum – Italian ryegrass. L. perenne occurs in the southern part of Europe. It is competitive and very prone to mutations and metabolic resistance, resulting in quick selection for ALS and ACCase resistance.

Wild oat is not as frequent in Europe because we usually grow winter crops. It is usually found in southern part of Europe, not Avena fatua but Avena sterilis and Avena ludoviciana. It quite frequently has resistance to ALS and ACC inhibitors. The problem is that triallate is not allowed in Europe, and alternative modes of action that can be used against these resistant biotypes are not available.

Brome species is a quite new issue in Europe, but it is spreading very quickly. A few resistant populations to ALS have been found in United Kingdom and in Spain. Brome species are also exhibiting a decreasing sensitivity to glyphosate because farmers use glyphosate in burndown control. It is not considered resistant, but the sensitivity is lower and lower.

In some Western European countries, ALS resistant mayweed (Tripleurospermum perforatum) has been found. It is a very difficult weed in cereals and oilseed rape.

Wild poppy is already resistant to ALS inhibitors, but some populations were also found to be resistant to synthetic auxins (Group 4). This resistance to synthetic auxins is a problem because many products used in spraying are a combination of ALS inhibitors – usually florasulam with 2,4-D or other auxins.

Less important resistant species in cereals are chickweed and cornflower. Few populations of chickweed have resistance to ALS inhibitors and rarely PSII and auxins. Cornflower is a very competitive

weed on sandy soils in Poland and Germany and is tolerant to ALS inhibitors in some areas.

There are several factors driving resistance in small grain cereals. Winter cropping is a big problem because the period between crops when weeds can be controlled is very short. A typical crop rotation is winter wheat followed by winter barley and then winter oilseed rape. Oilseed rape stays on the field for 11 to 12 months. There is only one week or two weeks for weed control between the crops. This is a challenge for perennial weed control and control of different resistant weeds that survive in-crop treatments. Usually, resistant winter annual grasses survive an herbicide application, shed seeds and immediately emerge in the subsequent crop.

The reliance on ALS and ACCase inhibitors is also a problem. We have too many ALS inhibitors used in weed control, and are about half of the all compounds used.

Our farms are also growing larger, and we are using more reduced tillage. Minimum tillage favours almost all the grasses. The combination of a narrow crop rotation and minimum soil tillage is now regarded as a multiplicator of the risk, especially from the point of view of the occurrence of winter grasses.

Corn is grown for grain and silage production. Overall, resistant weeds in corn are not an issue in Europe. Barnyard grass resistant to ALS herbicides occurs mainly in Italy, Spain and Hungary. Johnson’s grass, which is a perennial, has also developed resistance to ALS inhibitors. Farmers successfully use cycloxydim-tolerant (Group 1) corn varieties to control ALS-resistant grasses, since resistance against ACCase inhibitors has not yet developed.

In Czech Republic, some PS II inhibitors, such as terbuthylazine, are used in corn, although atrazine was banned few years ago. Terbuthylazine is a very cheap solution, but a recent survey found many PSII resistant populations of redroot pigweed. Interestingly, after

many years of use of ALS inhibitors and other mode of actions, these PSII resistant populations still occur.

Europe doesn’t grow glyphosate-tolerant crops, so it is used on arable land as between crop applications and as a pre-harvest application. In Czech Republic, glyphosate accounts for about 17 per cent of the total consumption of pesticides, which is not as high as in America. There is no glyphosate-resistance on arable land.

However, some resistance has been identified in permanent crops in Mediterranean, where citrus, olive, and grapevine are grown. Farmers rely only on glyphosate. The most important species are fleabanes – Canadian and Sumatran fleabane.

Factors regarded as glyphosate resistance drivers in permanent crops are very dense populations of a single species prone to resistance development; limited number of registered herbicides and a reliance on glyphosate; too late applications; unfavourable conditions for applications; and ignorance of non-chemical methods. Some alternative solutions must be implemented in orchards and in permanent crops to be able to control the weeds in the future.

Many glyphosate-resistant populations also occur on non-agricultural land, which can be an issue. These populations can spread on agriculture land. One weed, Asiatic dayflower (Commelina communis), which is very naturally tolerant to glyphosate and can survive 32 litres per hectare, was also found on railways.

On the other hand, glyphosate is very important because it diversifies the choice of mode of action to control ALS- and ACCase-

resistant weeds on arable land.

Introduction of glyphosate-tolerant crops is not expected in the near future. Glyphosate is recently under big political pressure by NGOs and different political streams. It is an issue from the regulatory point of view. Glyphosate received a renewal for the next five years, but we do not know what will happen after that five years. We expect very strong limitations on glyphosate use in coming years.

In Europe we have very similar networks for resistance monitoring, scouting, and mapping. Within the European Weed Research Society, the Weed Mapping working group and Herbicide Resistance working group operate. They communicate the resistance problem amongst scientists, industry, and governmental bodies. There is also a European Herbicide Resistance Action Committee (EHRAC; www.ehrac.org).

Legislation is used for the authorization and sustainable use of the pesticides. There are many regulations and directives. Some directives focus on placing of the plant protection products on the market, and other on the sustainable use of these products by farmers.

The European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization develop standards for testing of plant protection products and evaluating resistance risk. The standard describes how the risk of the resistance to plant protection products can be assessed and how they can be managed after the regulation of the product and placing of the market.

There are two types of the risk: inherent risks and agronomic risks. Both are considered in the registration process. The applicant and registration body first evaluate the inherent risk of the product. This is the risk assessment stage, and if there is no risk or the risk is small, the registrant establishes the baseline sensitivity, registers their product, and then follows the monitoring risk after the registration. If there is an inherent risk, there must be some resistance risk management proposed, and it is placed on the label.

There are very important directives for the sustainable use of the pesticides, and individual countries have to create national action plans for reduction of the risk and impacts of the pesticides on human health and on the environment. These should ensure appropriate training of farmers, testing of the application equipment, and implement the methods of integrated pest management. Some general principles of integrated managements are well known, such as prevention and suppression of harmful organisms and monitoring. Some rules are for decision-making, such as which measures are more appropriate. The pesticides should be applied as specific as possible so that it doesn’t affect the non-target organisms. Where the risk of the resistance against the plant protection measure is known and where the level of harmful organisms requires repeated applications, available anti-resistance strategies should be applied.

All countries develop national action plans. For example, rules for application of pesticides, measures to protect aquatic environments, reduction of the risk, and integrated pest management.

Some countries developed additional measures, like a pesticide tax, which is sometimes a problem for the farmers because this is a disadvantage to have a tax at the national level. The second problem is that it can be controversial and counter-productive because a mode of action, which is prone to resistance, such as ALS inhibitors, has lower taxes than other products that are not so prone to resistance.

European farmers get many supports and many payments, but they must fulfill basic standards concerning the impact on the environment. They should maintain good agriculture and environmental conditions. They receive direct payments. They receive, additionally, green payments that promote practices that are beneficial for the environment and for climate. There are also some agri-environment measures where payments are made to farmers who subscribe to measures related to the preservation of the environment and maintaining the countryside.

Very important for farmers now are the payments for “greening,” which is quite high, with 30 per cent of direct payments since 2015. Greening means farms have to diversify crop rotations. Farms up to 30 hectares have to grow at least two crops. Bigger farms must have at least three crops. To get the subsidy, all farms must keep five per cent of the farm with an ecological focus that uses some direct measure like fallow land, field margins, hedges and trees or buffer trips. Or they can grow catch crops or legumes. A problem starting in 2018 is that pesticides may not be applied to the ecological focus area. Also, permanent grassland cannot be ploughed or converted anymore.

The patterns leading to the development of herbicide resistance are the same everywhere. Factors leading to the resistance:

• Simplification of crop rotations.

• Prevalence of one crop type – in our case, winter crops.

Winter cropping is a big problem because the period between crops when weeds can be controlled is very short.

• Increase of population densities of weed species associated with crops creates higher probability of the development of the resistance.

• Species with high fecundity, long distance dispersion, and dense offspring are more prone to the development of the resistance.

• Overuse of the same mode of action like ALS inhibitors and ACCase inhibitors.

• Non-chemical methods are hardly applicable or not reliable fully. It is difficult to combine chemical and non-chemical methods.

• Environmental regulations can be sometimes counterproductive

• What is good for environment and for human health is not necessarily good from the point of view of the development of the resistance.

For the outlook on further management of herbicide resistance, everybody recommends more diverse management strategies. They are necessary and may prolong the effectiveness of herbicides, but crop diversity is decreasing everywhere, at the global level, at the local level, and according to market demands. Thus it is very hard to include new crops in crop rotations. Prices are set at the global level, and farmers may not create a sufficient margin for prevention of the herbicide resistance. They have to prefer cheaper short practices or tactics before the long-term strategies.

Resistance is also an environmental and social issue. I think public attention should contribute to the problem and support research institution networks, and transfer of knowledge. Acceptable regulations can help, but over-regulations can be often counterproductive. Farm management shouldn’t be a subject of regulation because it’s burdening, embarrassing, and sometimes costly, and the effect is not clear. Science can contribute to solving the problem. Farmers must look for latest knowledge in professional journals, fact sheets, and advisors and make scientifically based decisions. However, “thousands of small hammers” of traditional farming practices can help. We must learn from nature and field history and prepare efficient local recommendations.

Technological advance can help deliver new solutions to overcome the problems in the longer term because we will have new strains, new formulations, more precise application technique, equipment for strategic tillage, and harvest weed management. New tools will also support the remote detection of resistance and provide a decision support system. I am optimistic for the future, and think resistance won’t necessarily have to impact yields and production.

Presented by Hugh Beckie, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Saskatoon, at the Herbicide Resistance Summit, Saskatoon, Feb. 27-28, 2018.

The big story in 2017 was that canola surpassed wheat as the number one crop, and the most common rotation in Western Canada is canola-wheat, which certainly has implications for resistance management.

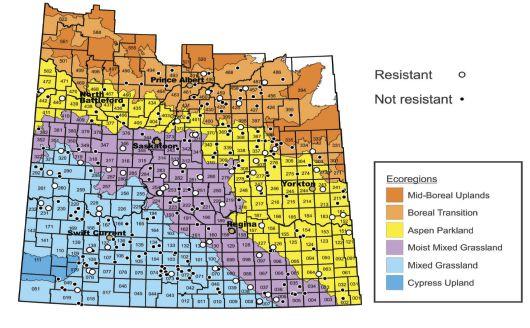

In terms of unique resistant weed cases for Canada, 76 have been identified. Manitoba has seen a big jump and now has 30 cases. Saskatchewan has 22 and Alberta 23 cases.

I’ve been doing surveys since the first one in Saskatchewan in 1995 and since 2001 they’ve been random surveys. It takes three years to do a round because we do Alberta then Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. We’ve gone from 10.9 million acres with herbicide resistance in the first survey to 24.4 million acres in the second round from 2007 through 2009 and I would estimate we will clearly reach 38 to 40 million acres in the last survey completed in 2017. With 70 million cultivated acres in western Canada, over half the acres have herbicide resistant weeds.

The Saskatchewan situation