TOP CROP MANAGER

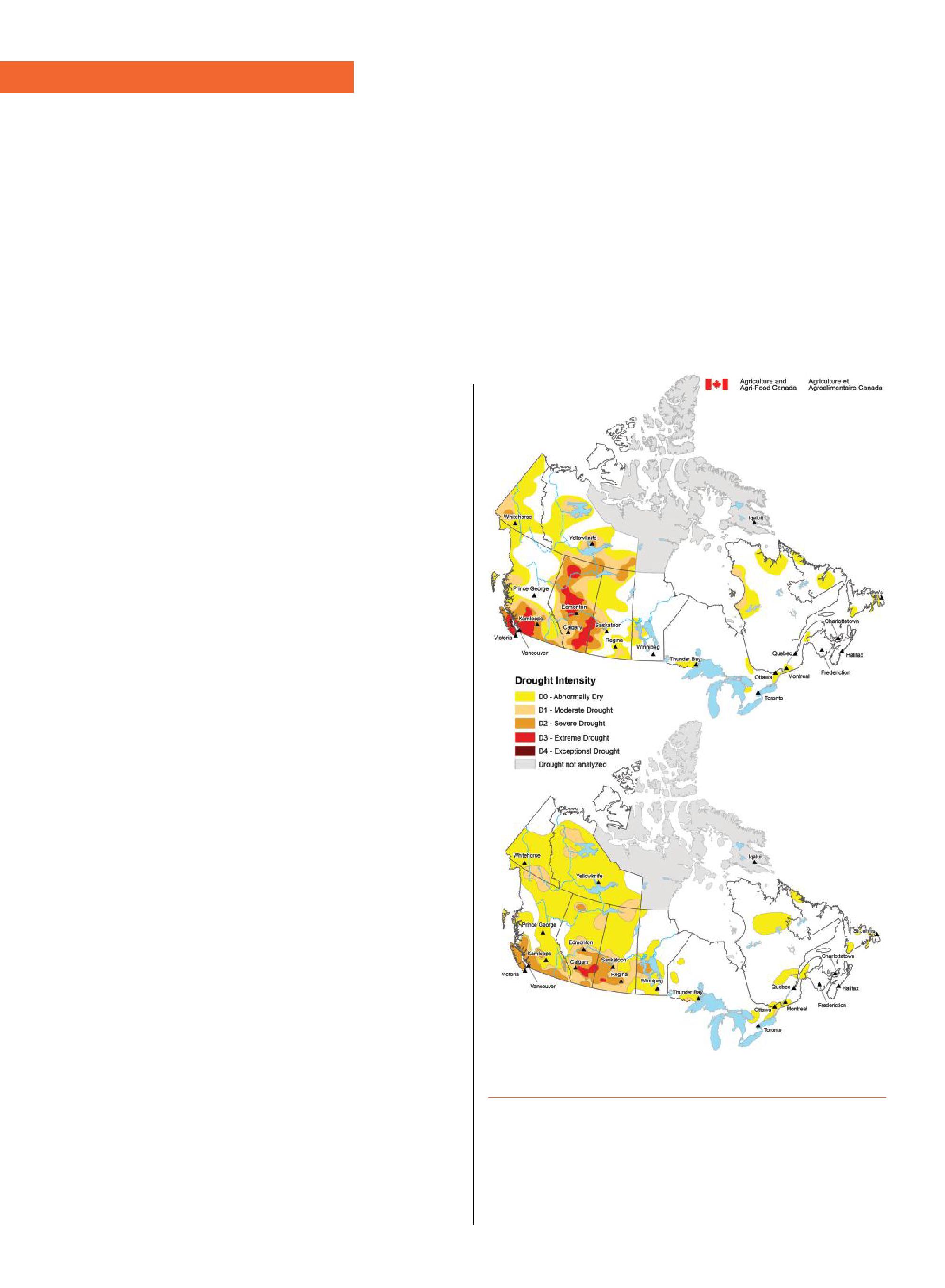

OUR PRAIRIE WEATHER

Understanding the effects of climate change

PG. 10

POLLEN BEETLE

A warming climate could mean a new pest threat PG. 23

HERBICIDE LAYERING

A new approach in the fight against herbicide resistance PG. 28

Understanding the effects of climate change

PG. 10

A warming climate could mean a new pest threat PG. 23

A new approach in the fight against herbicide resistance PG. 28

Think fast. Heat® LQ herbicide delivers quick, complete crop and weed dry down for a faster, easier harvest and cleaner fields next year. It can be applied on canola, dry beans, field peas, soybeans and sunflowers, and new for 2016, it’s supported for use on red lentils1. Tank-mixed with glyphosate, Heat LQ also lets you straight cut canola for improved harvesting and storability. Visit agsolutions.ca/HeatLQ or contact AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273) today.

8 | Getting to know cutworms

New publication to summarize historical and current research on cutworms.

By Bruce Barker

14 | CTF Alberta research update

Controlled Traffic Farming Alberta project in its sixth year. By

Bruce Barker

PAGES 17-22:

In this issue of Top Crop Manager, we feature three presentations from the 2016 Herbicide Resistance Summit, held March 2 in Saskatoon. Additional presentations from the 2016 Herbicide Resistance Summit will be included in Top Crop’s weekly e-news from June 8 to July 6. Subscribe to our weekly e-news and receive additional presentations automatically each week –agannex.com/e-newsletter-subscription

30 | Verticillium survey released Verticillium longisporum found across canola growing regions in Canada. By

Donna Fleury

JANET KANTERS | EDITOR

I’m constantly amazed by the scientific mind. To be fair, I think everyone on Earth is capable of thinking great things and inventing new and better ways of doing things. But this really takes the cake: add sunlight to a particular nitrogen molecule and out comes ammonia, the main ingredient of fertilizer used around the world.

The eco-friendly method of producing ammonia is described in a new study led by the Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Golden and involving the University of Colorado Boulder (CU-Boulder). The researchers hope the discovery may help enhance global agricultural activities while decreasing the dependence of farmers on fossil fuels, says CU-Boulder assistant professor Gordana Dukovic, a study co-author.

The researchers discovered that light energy can be used to change dinitrogen (N2), a molecule made of two nitrogen atoms, to ammonia (NH3), a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen.

Traditionally there have been two main ways to transform nitrogen, the most common gas in Earth’s atmosphere, for use by living organisms. One is a biological process that occurs when atmospheric nitrogen is “fixed” by bacteria found in the roots of some plants like legumes and then converted to ammonia by an enzyme called nitrogenase.

The second, called the Haber-Bosch process, is an industrial method developed a century ago that changes N2 to ammonia in a complex chain of events requiring high temperatures and pressures. The Haber-Bosch process requires the significant use of fossil fuels, resulting in a corresponding hike in greenhouse gas emissions.

As part of the study the team showed that nanocrystals of the compound cadmium sulfide can be used to harvest light, which then energizes electrons enough to trigger the transition of N2 into ammonia.

“The key was to combine semiconductor nanocrystals that absorb light with nitrogenase, nature’s catalyst that converts nitrogen to ammonia,” said Dukovic, with the department of chemistry and biochemistry. “By integrating nanoscience and biochemistry, we have created a new, more sustainable method for this age-old reaction.”

NREL research scientist Katherine Brown added that using light harvesting to drive difficult catalytic reactions has the potential to create new, more efficient chemical and fuel production technologies. “This new ammonia-producing process is the first example of how light energy can be directly coupled to enzymatic N2 reduction, meaning sunlight or artificial light can power the reaction.”

The new research is expected to inspire alternative concepts for meeting the demand for ammonia as a fertilizer, but in a more energy efficient and sustainable manner with a lower impact on the environment than current commercial processes, Dukovic explains.

Sounds like a win-win all around.

dkleer@annexweb.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

CIRCULATION

email: rthava@annexbizmedia.com Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3555 Fax: 416-510-5170

Mail: 80 Valleybrook Drive, Toronto, ON M3B 2S9

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues February, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East – 7 issues February, March, April, September, October, November and December – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada – 2 issues Spring and Summer – 1 Year $16.50 Cdn. plus tax

by Bruce Barker

Over 100 years of insight into wheat cropping systems at Lethbridge, Alta., provides a treasure-trove of data for researchers with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). First cultivated in 1910, a long-term cropping study was initiated in 1911 to look at the impacts of crop rotations on soil productivity, wheat yield and profitability.

In 2014, research scientist Elwin Smith at AAFC in Lethbridge took a snapshot of the last 42 years of the long-term plots to assess profitability and risk of wheat rotations. One of the benefits of the long-term plots is they can reveal changes in soil productivity over time due to production practices. An example was how the fallowwheat rotation without nitrogen (N) fertilizer was initially the highest yielding and most profitable, but eventually yields declined because the soil was “mined” of nitrogen fertility.

“Unfertilized soil could no longer provide adequate nitrogen for wheat production after fallow,” Smith says in his Canadian Journal of Plant Science article. “The decline in the N supplying ability of the fallow occurred over many years and would not have been observed without this study having run for several decades.”

Smith set up his review of the long-term plots to determine the impact of crop rotation and fertility management on spring wheat yield, if yield changed over the 42 years, and the profitability and risk levels of the crop rotations. The plots were originally established in 1911 with continuous wheat (W), fallow-wheat (FW) and fallow-wheat-oats (FWO) rotation until 1923, and then a fallowwheat-wheat (FWW) replacing the FWO rotation from 1924 to present.

The soil is typical of the semi-arid region and is an Orthic Dark Brown Chernozem. The treatment plots are large at 0.6 ha (1.5 acre). While the plots are unreplicated, they are representative of the area’s landscape and variability, and the long duration of the study provides extensive replication over time.

In 1967, the plots were split into two to accommodate an N treatment of unfertilized and 45 kg N/ha (50 lb N/ac). In 1972, the subplots were split in half again to accommodate a phosphorus (P) treatment of unfertilized and 20 kg P/ha (40 lb P2O5/ac). Nitrogen was broadcast applied at seeding and P placed in the seedrow. The P rate was reduced to 10 kg P/ha (20 lb P2O5/ac) in 2010 because the rate of removal was less than applied P, resulting in a build-up of P to 50 to 80 ppm. Unfertilized P plots were still testing 10 to 20 ppm. From 1972 to 1985, fallow plots received P fertilizer, but since 1986, only the cropped plots were fertilized.

The agronomic practices were similar to local production practices. New wheat varieties were adopted as better varieties came

ABOVE: A fertilized fallow-wheat-wheat rotation would be preferred by farmers with moderated risk tolerance.

along. Tillage was kept to a minimum and used to incorporate preemergent wild oat herbicide, but seldom used in fallow over the last 10 years. No post-harvest tillage took place.

As would be expected, there were a wide range of rainfall and yields over the 42 years. The average annual growing season precipitation was 176.5 millimetres (mm) (seven inches) with a range from a low of 52.4 mm (two inches) in the drought year of 1985, to 338.1 mm (13.3 inches) in 2002.

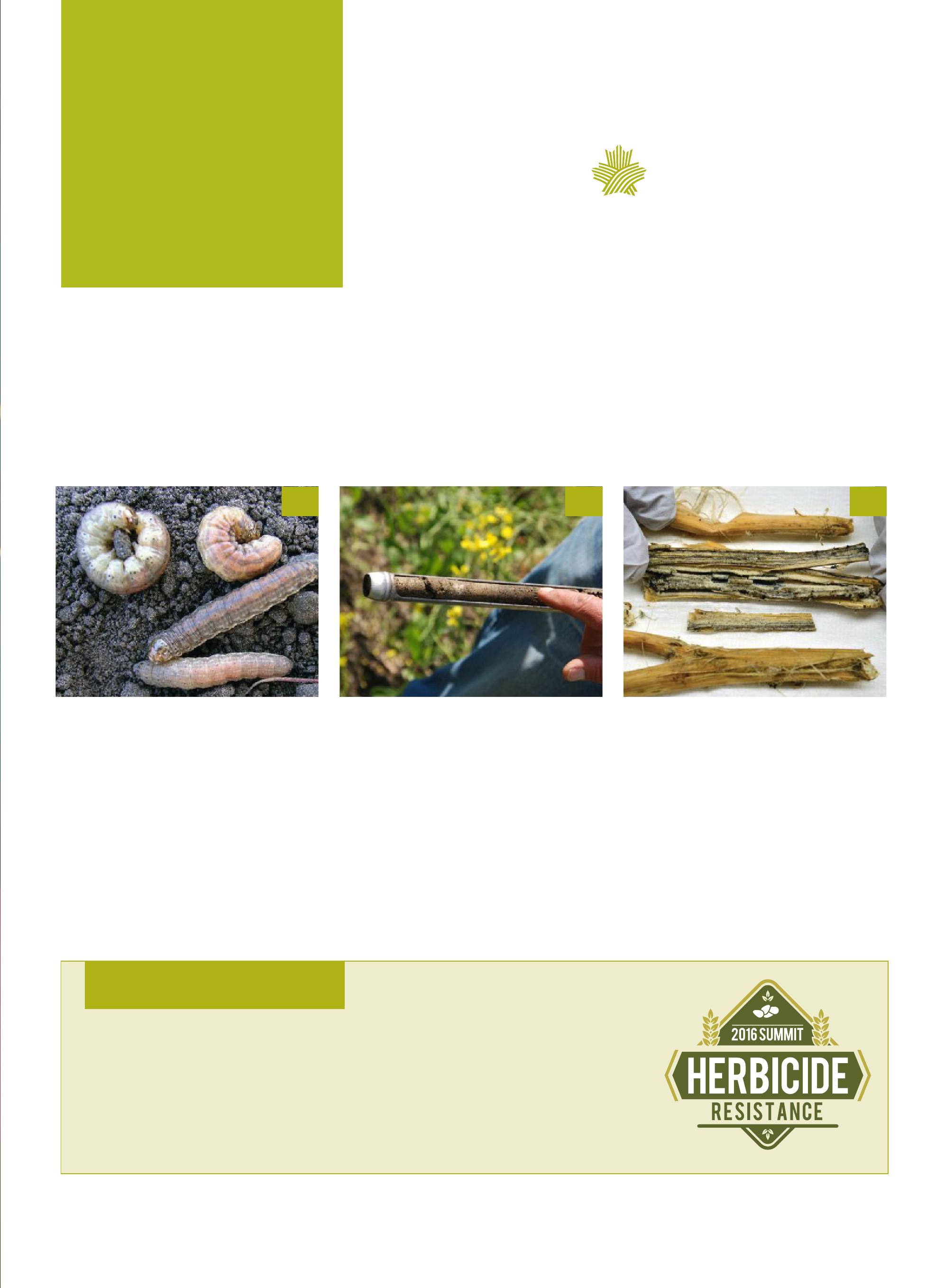

Smith analyzed the yield data for all 42 years, and also split the data into the first and last 21 years. The impact of rotation and fertility on yield and profitability was determined.

Smith found that crop rotation, N and P treatments significantly impacted wheat yield when divided into the two 21-year periods. In the first 21 years, wheat yield responded to P fertilizer, likely because the soil was deficient in P from the first 61 years of cropping

Probability

Probability

without P fertilizer. In the second 21-year period, P response was only observed if N fertilizer was applied.

W(N45P20) (a) All years

FW(N0P0)

FW(N45P0)

FW(N45P20)

FWW(N45P20)

W(N45P20) (b) First 21 years

FW(N0P0)

FW(N0P20)

FW(N45P20)

FWW(N45P20)

W(N45P20) (c) Last 21 years

FW(N45P0)

FWW(N45P0)

FW(N45P20)

FWW(N45P20)

In the last 21 years, 30 per cent of the time (0.7 Probability axis), producers could expect net return of at least: $437/ha for W(N45P20), $254/ha for FW(N45P0), $288/ha for FW(N45P20), $235/ha for FWW(N45P0), and $306/ha for FWW(N45P20).

Source: Smith et al. Yield and profitability of fallow and fertilizer inputs in longterm wheat rotation plots at Lethbridge, Alberta. Can. J. Plant Sci. 95: 579-587. Probability

In the first 21-year period, N fertilizer provided a yield response for the wheat grown on wheat stubble phase, but did not after the fallow phase. However, in the second 21-year period, yield was responsive to N in all crop sequences, including wheat planted on fallow. The increases were large, with wheat yield 0.571 tonne/ha (8.5 bu/ac) higher for the FW phase and 0.473 tonne/ha (seven bu/ac) for the wheat grown on fallow in the FWW rotation compared to the same rotations without N fertilizer. Mineralization of N under fallow was not adequate to meet crop needs in the second 21-year period.

Using average real prices for wheat and fertilizer over the 42-year period, Smith set out to look at which rotations and fertility treatments were most profitable. First looking at the entire 42-year period, crop rotations that utilized either N45 (N at 45 kg/ha) or N45 and P20 (P at 20 kg/ha) had the highest net returns at $177 to $210 per ha ($71 to $85 per acre). The systems without N (W(N0P0), W(N0P20), FWW(N0P0) and FWW(N0P20)) had the lowest average net return of less than $100 per ha ($40 per acre).

For the first 21-year period, average net return was highest for FW without fertilizer (FW(N0P0)), followed by FW with P fertilizer (FW(N0P20)) and then FW with N and P fertilizer (FW(N45P20)). However, because the soil ran out of N fertility in the second 21year period, the net returns changed. The continuous W rotation had the highest potential net return, and the FW rotations the lowest potential. In the last 21-year period, rotations with N and P fertilizer were more profitable; W(N45P20) was the most profitable ($118/ac), followed by FWW(N45P20) ($99/ac) and FW(N45P20) ($95/ac). (See Fig. 1.)

Smith also assessed the cropping systems for risk by looking at the average return and the variability of return over the years. He says in the first 21 years, the wheat fallow system without added fertilizer was the most profitable and would have been preferred by farmers because of the low risk and lower cost of production. But in the last 21 years, when the fallow soils had run out of adequate N fertility, the fully fertilized systems were more profitable and less risky.

The most profitable system in the second 21-year period, on average, was fertilized continuous wheat, but Smith says it also had the most risk because of the impact of low yield or prices over the years. Net return can be negative in years with low yield and/or low prices, but it will also be higher in years with high yield and prices.

For wheat farmers willing to tolerate moderate risk, the fertilized FWW rotation was preferable. It gave up some revenue potential because of the year of fallow, but reduced yield variability.

A fertilized FW rotation may be preferred by very risk-adverse producers as yields and net returns are more stable, but of the three fertilized systems, profitability was lower over the longer term.

Other research has also been conducted on crop rotations in the semi-arid Prairie region. While in the long-term trials at Lethbridge

Brandt is celebrating $1billion in annual revenue and we’re thanking our customers by offering special rebates throughout the year. Visit thanksabillion.ca for details.

We made the 2045LP GrainBelt Brandt’s fastest, most efficient Field GrainBelt yet. It is capable of moving an impressive 12,000 bushels per hour at truck loading height with just 35 horsepower. Whether you’re loading trucks, air carts, or railcars you can count on Brandt’s 2045LP to gently handle your seed investment while maximizing your productivity. Built on Brandt’s years of grain handling experience, the new 2045LP is the ultimate in productivity. That’s Powerful Value. Delivered.

Brandt’s EZTRAK tensioning and tracking system keeps your belt aligned and properly tensioned at all times.

Brandt’s low profile hopper easily fits under hopper bottom bins and center bin unload systems so you can use it anywhere.

Brandt’s fastest and most efficient Field GrainBelt, the 2045LP moves 12,000 bu/hr using only 35 horsepower.

by Bruce Barker

ACanola Agronomic Research Program (CARP) project on cutworms is entering the final stages of completion, resulting in an information book that will be ready later this year. The Cutworm Booklet will help producers identify and control cutworm species, and give them a better understanding of the role of natural enemies in the control of the various cutworm species.

“The booklet will provide a greater depth of information than is generally available to farmers and agronomists,” Kevin Floate, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Lethbridge, Alta., says.

Floate, along with colleague Jennifer Otani at AAFC Beaverlodge, is currently finalizing the booklet, funded by the CARP program. CARP is funded by the provincial grower organizations – Alberta Canola Producers Commission, SaskCanola and the Manitoba Canola Growers Association – in partnership with Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund.

Cutworms are generally present in most cropland every year, but occasionally will reach economically damaging levels. From 2007 through 2010, they were a serious insect pest in canola, and have been relatively common in the past few years. Floate says climate cycles are the likely cause of periods of outbreaks, which occur sporadically every five to 30 years. Successive dry years increase the potential for outbreaks of pale western cutworm, whereas successive wet years increase the potential for outbreaks of black cutworm.

Otani says current agronomic practices including continuous cropping and tillage may also be affecting cutworm incidence and distribution. She says tillage and summerfallow were historically used to reduce cutworm numbers by eliminating green vegetation for cutworm moths to lay their eggs on or near. However, continuous cropping and protecting the soil surface from erosion now out-

weighs the use of these practices to manage cutworms.

“Continuous cropping is advantageous to growers but it also provides cutworms and other herbivores with a continuous host plant. There are cutworms that prefer grasses and cereals whereas some prefer broadleaves. Yet again, some cutworm species include all these plants in their diet so, from larva to moth, continuously cropped land can offer preferred host plants for moths to lay their eggs on or near in the late summer and into the fall, and then the spring seeding offers new plants to feed upon,” Otani says.

Floate says three main species cause damage on the Prairies, including the pale western cutworm, redbacked cutworm and army cutworm. Other pest species include black army cutworm, glassy cutworm, black cutworm, darksided cutworm, dingy cutworm, bristly cutworm and armyworm. Understanding the lifecycles and feeding habits of the species can help farmers and agronomists with scouting techniques and control methods.

The larval stage causes damage, and information from the draft cutworm booklet describes the three general feeding habits. “Subterranean cutworms feed almost exclusively underground: larvae cut the main stem of young plants, but otherwise are not usually seen. The larvae of ‘above-ground’ cutworms will feed on foliage and older larvae may cut the main stem of young plants at or near the soil surface, normally feeding at night and hiding in the soil during the day. The larvae of ‘climbing’ cutworms climb up plants to feed on the foliage without necessarily damaging the main stem. These feeding differences affect the effectiveness of insecticide applications.”

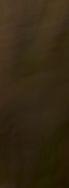

ABOVE LEFT TO RIGHT: The two insects on the left are cutworms; the two insects on the right are tipulid larvae. Ground beetle eating a bertha armyworm larva.

According to Otani, some cutworm species are relatively more subterranean during their larval development and are difficult to control using registered, foliar-applied insecticides, as they remain underground and are less likely to come into contact with the active ingredient. “In contrast, many species of cutworms will climb onto foliage at dusk to feed. These cutworms are sometimes referred to as ‘climbing cutworms’ and growers can target their scouting to early evening or sometimes early in the morning to estimate larval densities and compare to existing nominal thresholds that vary by crop,” she notes.

Nominal economic thresholds have been developed for cutworms, and are posted on Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Development’s website in the “Cutworms in Field Crops” section. For example, in canola, a suggested nominal threshold is 25 to 30 per cent stand reduction. In wheat, oats and barley, the nominal threshold for redbacked and army cutworms is five to six per square metre.

Floate says identifying cutworm species is possible for growers and agronomists, although it takes a certain level of expertise. He says the time of year, geographic region, and type of crop being damaged (cereal versus broadleaf) are indicators of what the species is likely to be, but do not provide absolute identification.

“Occasionally we see cases where the larvae of crane flies are misidentified as cutworms. Plus there are many non-pest species of cutworms that are generally present in low numbers, so proper identification is important,” Floate says.

The Cutworm Booklet will have a detailed chart of lifecycles for each cutworm pest species, showing when the damaging larval stage is present, type of feeding characteristic, species characteristics and larval photos. Good larval photos can also be found on the Manitoba Agriculture website.

Natural enemies of cutworms are important in controlling cutworm outbreaks. Floate says farmers and agronomists should implement practices to help these predators, pathogens and parasitoids. Recent surveys of cutworms recovered in south, central and northern Alberta from 2012 to 2014 identified parasitoidism to be

about 20 per cent. Pathogens can further add to this mortality rate.

“The key thing is to use insecticides only when required, and limit the use of insecticides to affected areas,” Floate says. “Maintaining a healthy population of natural enemies is akin to having an unpaid standing army on call ready and willing to feed on pest species when outbreaks arrive.”

Another way to help conserve natural enemies is to maintain field margins in an uncultivated state with a diversity of grass and flowering species. According to Floate, this provides the natural enemies with a place to overwinter, along with a ready food supply. Flowering plants provide adult parasitoids with a source of nectar that might not be present in the crop. Non-pest insects that feed on plants in the field margin provide predacious insects with a source of food when there are no pest insects in the crop.

The Cutworm Booklet is expected to be available online at the Canola Council of Canada website in late spring or summer.

For more on pests, visit topcropmanager.com.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 6

the continuous wheat rotation was the most profitable, agronomically it has some limitations, including the risk of building up disease, weeds with tolerance to herbicides for cereals, and insect pests.

Research at AAFC Swift Current by research scientist Yanti Gan shows how crop rotations have evolved since the Lethbridge long-term plots were established. He looked at including a pulse crop instead of a fallow in a FW rotation. Gan ran a three-year cropping sequence study, repeated for five cycles in Saskatchewan from 2005 to 2011. The cropping sequence included a cereal-pulse-cereal rotation with fertilizer, compared to a FW rotation.

Gan reported that, “in a three year cropping cycle, the

pulse system increased total grain production by 35.5 per cent, improved protein yield by 50.9 per cent, and enhanced fertilizer-N use efficiency by 33 per cent over the summerfallow system. Diversifying cropping systems with pulses can serve as an effective alternative to summerfallowing in rainfed dry areas.”

The cumulative findings of these and other crop rotation studies have helped farmers on the semi-arid Prairies in Saskatchewan include pulses in their rotations for several decades. In Alberta, the current high price for red lentils may convince more southern Alberta farmers to include a pulse in their crop rotation. Indeed lentil acreage has been on a slow rise in Alberta, with 220,000 acres grown in 2015.

Understanding the effects of climate on crop production can further aid farmers in making crop management decisions.

by Ross H. McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag.

Plants require a specific amount of heat and water to develop from one point in their life cycle to another. Unexpected events such as a late season spring frost, early fall frost, extended saturating rain and hail are just some of the weather factors farmers must frequently contend with.

So too weather influences the life cycle of many insects that can affect insect pressure and damage to crops. Weather also influences disease pressure and crop disease levels. The bottom line – weather has huge direct and indirect effects on crop growth, yield and quality.

As farmers and crop research scientists develop a better understanding of the effects of weather and climate on crop production, more informed crop management strategies can be developed. And as meteorologists improve their accuracy to predict weather, this will further aid farmers in making crop management decisions.

Farmers need to be familiar with and understand basic croprelated weather terms:

Weather is the short-term condition of the atmosphere at a specific place and time, such as temperature, dryness, sunshine, wind, rain, etc.

Climate is the average weather for many years or accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. It is the sum of all statistical weather information that helps describe a specific place or region.

Growing season is the period of time in a year when the climate is suitable for cultivated plants to experience growth. Growing season length is usually determined by the number of consecutive frost-free days.

Growing season precipitation is the total amount of rainfall received from planting to maturity.

Growing degree days (GDD) is a measure of accumulated heat used to predict crop growth stages. GDD are calculated by taking the average of the daily maximum and minimum temperatures and subtracting a base temperature using the formula:

ABOVE: Weather factors including moisture availability, temperature and solar radiation affect crop yield potential.

As we reach for higher yields and more efficient use of our resources, it’s important to go back to the basics. The three macronutrients – nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium – need to be adequately supplied throughout the growing season, but may not be available for various reasons. Micronutrients do play a role in plant health but without the “big three”, their impact is limited. YaraVita foliar macronutrients provide the plant an immediately available supply of those nutrients when they are limiting and time is of the essence. Add YaraVita to your fertility program and bridge the gap to higher yields.

Change in Growing Degree Days at Lethbridge from

Source: Dr. S. Kienzle, University of Lethbridge.

Source: Dr. S. Kienzle, University of Lethbridge.

Each degree that a day’s mean temperature is above a reference temperature is counted as one degree-day. Base temperature used is usually 0, 5 or 7 C depending on the crop.

Corn Heat Units (CHU) is also a measure of accumulated heat, using a more complex temperature formula than the formula used for GDD, and is used to determine the amount of heat needed by corn or soybean to reach maturity in Western Canada.

Frost injury occurs when ice forms inside plant tissue and damages plant cells. Frost injury can affect the entire plant or a specific part of plant tissue, which reduces yield or quality. Knowing the probability of frost occurrence in spring and fall is important. A light frost of 0 to -1.5 C will kill sensitive plants such as beans at emergence but has no effect on cereal crops at emergence. Moderate frost of -1.5 to -4.0 C has little effect on cereal crops at emergence but has a destructive effect on cereal or oilseed crops at flowering or grain filling.

Evapotranspiration is the combination of vaporization of water directly from the soil surface and release of water vapour by transpiration from vegetation, and is used to determine water use by crops on a daily and seasonal basis.

Solar radiation is the energy from the sun that provides light and heat required for seed germination, leaf expansion, growth of stems and shoots, flowering, fruiting and thermal conditions necessary for the physiological functions of the plant.

Probability is the prediction of the likelihood of an occurrence of a specific weather condition (e.g. probability of frost event).

Collectively, weather factors including moisture availability, temperature and solar radiation and many other factors affect crop yield potential. As weather factors vary from year to year, so does crop yield potential.

In recent years various media have reported on climate and how it is changing. A research study conducted by Stefan Kienzle and co-workers at the University of Lethbridge (U of L) examined all weather records in Alberta from 1950 to 2010 to determine if there were any significant climate change trends over the past 60 years. Their work showed that at Lethbridge, the growing season length increased from 193 to 214 days from 1950 to 2010, an increase of 21 days. At Edmonton and Grande Prairie the growing season increased by 11 and 22 days, respectively.

The U of L group looked at the total number of days per year with a maximum temperature of 25 C or more. At Lethbridge, the number of days increased from 54 to 61, an increase of seven days. At Edmonton and Grande Prairie, the number of days increased by 13 and eight days, respectively.

Heat wave periods were evaluated. They defined heat wave as when the average daily temperature is 5 C or more above average, for at least five consecutive days. At Lethbridge, heat wave days increased from 20 to 39, an increase of 19 days. At Edmonton and Grande Prairie, heat wave days increased by 21 and 20 days, respectively.

Kienzle’s research study has shown that the length of growing season and the number of days over 25 C have increased across most of Alberta. This is good news for Prairie farmers: more heat equals a longer growing season for crops, which in turn means crops are able to capture more radiant sun energy if seeded earlier, thus increasing crop yield potential. A longer

growing season also reduces the risk of early season frost injury at crop maturity, and it increases the potential to grow new crops that require a longer growing season.

The down side is that with a warmer growing season, the potential evapotranspiration of crops is also increased. This means that crops may require more water to produce the same yield due to increased transpiration. Fig. 2 shows examples of increased potential evapotranspiration at two southern Alberta locations at Pincher Creek and Taber.

A concern looking forward is the effect of climate on snow pack in the mountains and potential water availability for irrigation farmers and water flow in rivers in spring and summer. Fig. 3 shows the trend of snow pack in the Castle River region west of Pincher Creek. This is a tributary of the Oldman River and ultimately the South Saskatchewan River. If snow pack is gradually reduced each winter, this will reduce water available for irrigation across the Prairies.

Of greatest interest will be the trend for stored soil moisture

in spring and average growing season precipitation. If the growing season precipitation trend is upward in the future, that will be good news for Prairie farmers for increased crop yield potential. However, if the trend is reduced precipitation and increased heat waves, this will mean Prairie farmers will have to adapt to more water use efficient crops and crops with greater drought tolerance.

Careful observation of weather and climate trends in the future will become increasingly important for Prairie farmers and crop research scientists to adapt crops, crop rotations and crop management strategies to ensure optimum crop production.

The U of L group has developed an interactive Alberta map to show a number of weather variables and provide trend lines for each weather variable: albertaclimaterecords.com.

For more on weather, visit topcropmanager.com.

When your goal is fast, even crop emergence, trust Väderstad to help. With innovations like Patented Precision Openers and Wireless iCon™ Control, our Seed Hawk Seeding System places seed and fertilizer with unparalleled accuracy, in all soil conditions. Which gives you the greatest opportunity for higher yield.

Evolve your farm. Ask your equipment dealer about the Seed Hawk Seeding System, or visit SeedHawkSeeder.com

Evolve your farm.

by Bruce Barker

The Controlled Traffic Farming Alberta (CTFA) project entered its sixth year of fieldwork in 2016.

CTFA 2014-2017 is a joint project with the University of Alberta department of renewable resources and is funded primarily by the Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund (ACIDF). The Alberta Canola Producers Commission provided funding for 2014-15. Additional funding and help comes from Beyond Agronomy, Demeter Solutions, AgViser Crop Management, Paradigm Precision and their managing partner, the Agricultural Research and Extension Council of Alberta.

The project now has eight co-operator farms spread out over 1250 kilometres, giving it a wide range of soils and climatic conditions, including one irrigation farm. Their cropped acreage ranges from 670 to 8650 acres. The project started in 2011 with five cooperating farms.

“The co-operators have made significant investments and undertaken additional risk to implement CTF on their farms,” says Peter Gamache, project leader with CTFA. “Our co-operators are leading

the charge to see if controlled traffic really works on our Alberta soils.”

Controlled traffic farming (CTF) is a crop production system in which the crop zone (cropped area) and traffic lanes are distinctly and permanently separated. In practice it means that all implements have a particular span or multiple of it and all wheel tracks are confined to specific traffic lanes.

Essentially, permanent tramlines are established. This reduces field traffic down to about 12-17 per cent of the field, compared to a traditional, one-pass seeding system that covers about 50 per cent of a field each year. Gamache says research estimates 80 per cent or more of the damage caused by compaction is created on the first pass over the field, especially if soil moisture is near field capacity.

Gamache explains the move to larger and heavier equipment and random traffic has increased compaction, which may be a largely unrecognized problem in many Alberta fields. “Wheel track

ABOVE: Controlled traffic farming has the potential to improve soil structure.

damage often shows up with poor crop emergence and delayed crop maturity. Once you start looking, it is pretty common to see in-season compaction damage.”

A revised research protocol was set up in 2014. Random traffic was simulated on field-scale plots on a controlled traffic field at each co-operator location just prior to or just after seeding. A variety of equipment was used, ranging from four-wheel drive tractors with dual wheels and sprayers. The simulated random traffic resulted in greater than 50 per cent of the soil surface being tracked compared to about 15 to 20 per cent for the controlled traffic area.

Water infiltration rates have been monitored for five years. The CTF plots have shown consistently faster average infiltration rates of one inch of water compared to random traffic plots, although not always significant at 10 per cent probability. The heavy clay soils at Trochu and Morrin showed significant differences in favour of controlled traffic.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada is monitoring crop emergence and weed populations. Weed populations are counted each spring, prior to or just after in-crop spraying. Weed counts from 2012 through 2015 do not reveal any population shifts. No sites in 2015 showed a significant difference in crop emergence.

Kris Guenette with the University of Alberta’s department of renewable resources is conducting research on soil quality improvements with controlled traffic farming. His 2015 report indicates that when comparing the trafficked soil samples to the un-trafficked soil samples, it was generally observed that the bulk density decreased, the macro and mesoporosity increased, the microporosity decreased, and the unsaturated hydraulic conductivity increased. He says the presence of compaction caused by farm vehicle traffic has a pronounced effect on soil properties. The continuous application of compaction has contributed to alterations in soil properties, which can directly affect the overall quality of the soil. The S-index measurements in this study show that the absence of vehicle-induced compaction has positive effects on the soil quality.

Yield data was taken from the replicated field plots and collected from combine yield monitors and, in some cases, grain carts with scales. In 2015, the Trochu site CTF yield was significantly higher (P=10%), while the other sites showed no significant difference (P=10%).

Although most of the co-operators have not seen a trend towards improved yields with the CTF system, Gamache says the improvements in soil quality provide an indication that yields may improve over time. He says that given our climate and soil types, he is uncertain how long it may take to repair our soils after years of random traffic and high axle loads, especially in the subsoil horizons.

“There is evidence that soils take a long time to recover from compaction,” Gamache says.

A summary of 20 soil compaction experiments in North America and Europe by Pennsylvania State University indicates “…compaction due to axle loads of 10 to 12 tons reduced yields approximately 15 per cent in the first year, decreasing to three to five per cent 10 years after compaction.”

An economic analysis is being conducted by Dennis Dey, an independent agrologist. In 2015, he found differences in gross margins for CTF and random traffic acres are due to the differences in yields and could not be attributed to CTF systems except at the Trochu site. The range of net benefits to CTF (gross revenue less variable costs)

Peter Gamache, CTFA project lead, says based on experiences in Australia, Europe and Alberta, controlled traffic farming could provide benefits to Prairie farmers. The figures in brackets are from Australia. The CTFA project is working to quantify these potential benefits.

• Improve soil structure – reduce overall compaction

• Enhance soil rooting depth and exploration of soil profile

• Increase water infiltration (up to 15%)

• Increase soil water storage

• Increase moisture use efficiencies (up to 50%)

• Improve nutrient use efficiencies (up to 15%)

• Increase yields (10 to 15%)

• Reduce pesticide costs – targeted spraying

• Reduce fuel consumption (up to 10%)

• Improve trafficability of equipment

• Lower machinery investment

varies substantially by location.

Gamache says the CTF system is functioning well on each farm and is proving to be a resilient system. It has improved the timeliness and efficiency of operations, however it does require a very high level of management. He says there are challenges to implementing CTF and much to be learned. Careful, long-range planning is essential. Good residue management is a must, just as it is in no-till systems. Tramline repair will be needed in some cases. CTFA has purchased a tramline renovator to test in 2016.

Overall, Gamache says the co-operators are committed to carrying on the research, and most have converted their complete farm over to controlled traffic farming.

“The advantages of the system are proving to be valuable. The timeliness and efficiency of operations is a significant benefit. The ability to do accurate, reliable on-farm research is valuable. The precision of a CTF system opens up a whole new world of agronomic and economic opportunities such as in-crop nitrogen application, on-row fungicides and precision seed location,” Gamache concludes.

The complete 2015-2016 CTFA Project Report, including co-operator notes, can be found at controlledtrafficfarming.org. Check out the “Upcoming Events” section for CTF summer tours and events.

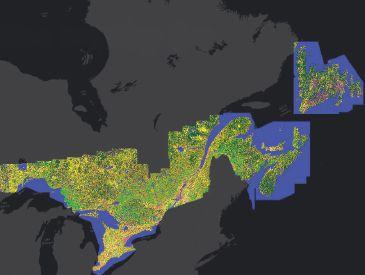

by Dale Steele, P.Ag., Precision Agronomist

Aparadigm is a set of concepts, practices or thought patterns that create a framework to define our way of looking at something. Your age will influence your paradigms as you transition from the optimism of youth to the caution of old age. If dad told you there was no future in farming, you were likely to believe him, but his ideas were formed by his own disappointments. The future is unknown but it is our paradigms that will influence our expectations; where one person may see a challenge, another will see an opportunity. Is the future bright or is it cloudy?

Our common experiences, beliefs and values create a dominant paradigm that is held across segments of society at a given time. The organic food debate is a good example of the different paradigms about food and the connection that people want to have with their food production. A commercial farm’s paradigm is to produce a safe and abundant food supply as efficiently as possible using the best available tools. The urban consumer has a paradigm that is centred on their experience with food. An organic shopper wants fresh food that is produced “naturally” to fit their food paradigm.

The beliefs within a paradigm can be difficult to define as we attempt to draw the lines between the different ideas. For example, how to define a chemical can be debated when different groups analyze the same data and see different trends and results based on their paradigms. This is why the GMO debate continues 20 years after GMO crops were introduced.

A paradigm shift occurs when our views change in response to the accumulation of theories or evidence. Consider that farmers once had a reverence for worked ground and the smell of the earth following the plow. But over time, our paradigms shifted to value minimum tillage for the benefits it provided.

Precision agriculture contains a paradigm shift in how we approach farming. Each of us can look at farm fields and have different

perspectives and judgments as to the merits of what we see. My farmland has rolling hills and a range of soil organic matter that produces a range of yield results from the uniform crop input applications. To me, it always seemed odd to apply the same rate of fertilizer to good areas and poor areas of the field, but my older equipment wasn’t capable of varying the rates automatically.

I remember looking at the combine yield monitor for the first time and seeing the near-infrared (NIR) images of crop vegetation, which reinforced what I knew about my fields and their natural variability. But now with precision agriculture, I had a framework to do something about it. I could see the layers of data to better understand crop variability across the fields and could take action to manage it.

Many of the components of precision agriculture, which monitor and measure the soils, vegetation, water and yields, are now in place. The equipment is capable and there are precision agronomists and technicians ready to meet the farmer demand for precision agriculture services. Crop inputs are used across millions of acres and we generally understand how they work and are expected to perform. But when a farmer is facing a stressed crop, he doesn’t care what the normal or average results are on millions of acres. He wants to understand his unique field situation.

Research and product development strive to identify regional differences in product performance, potential crop injury and rotational carry-over for specific soils. We know that landscape and soils determine the variability of the vegetation and that specific weather will affect the crop in predictable ways. How we look at fields will determine what you can see. When you ride a horse across a field, drive

ABOVE: Growing a great crop is more complicated than filing the annual farm taxes, but most farms readily hire an accountant before they hire an agronomist.

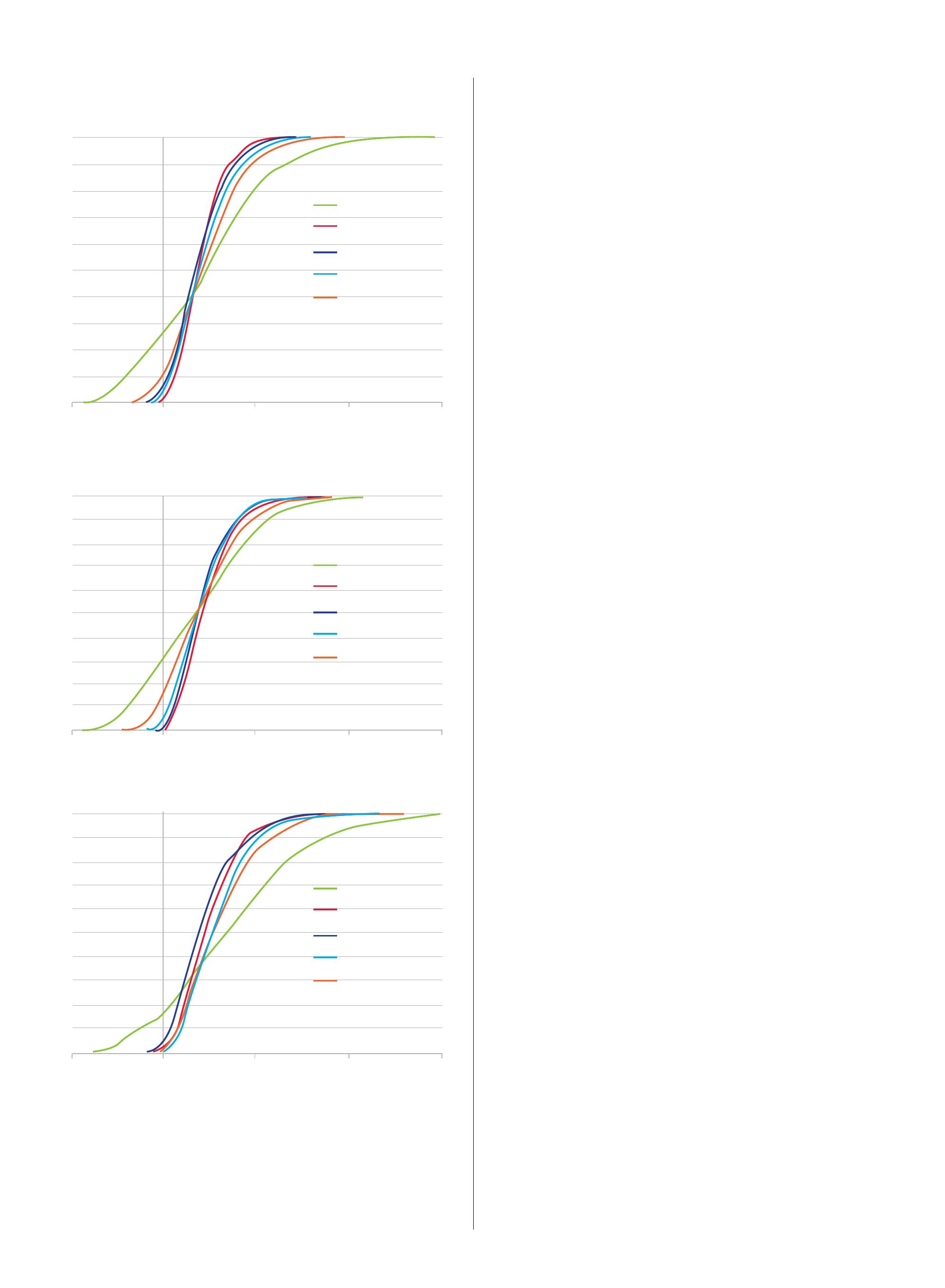

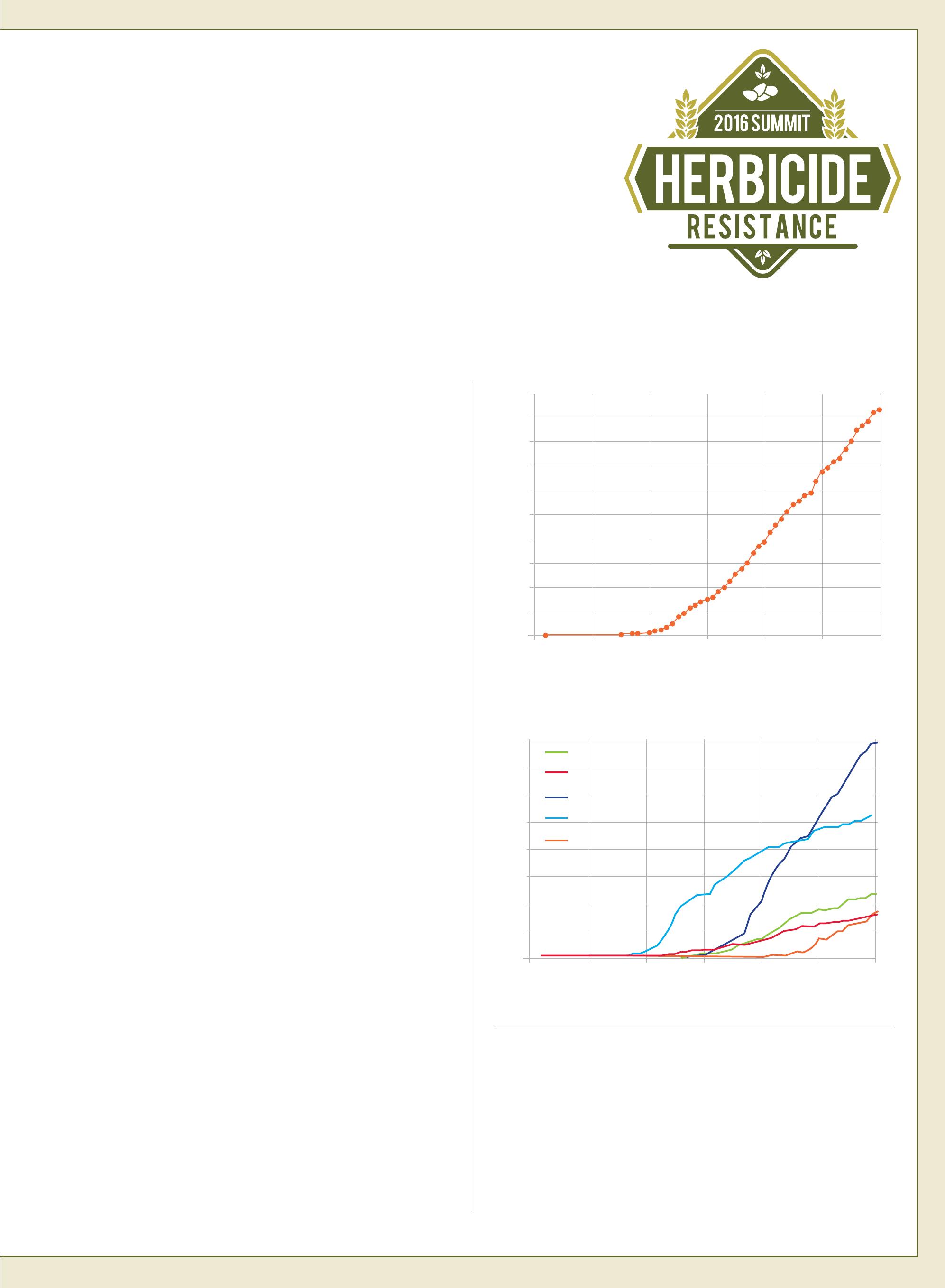

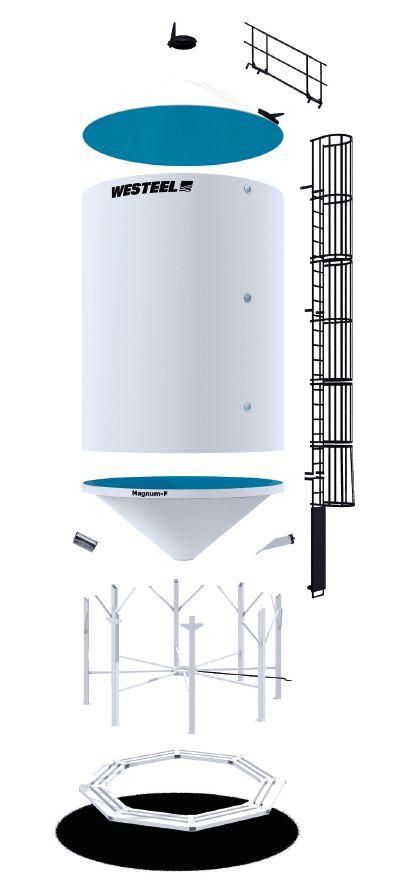

Presented by Ian Heap, Director of the International Survey of Herbicide-Resistant Weeds, Corvallis, Oregon, U.S.

Resistance is futile. Herbicide resistance is quite predictable. There is nothing mysterious about herbicide resistance. It is a simple, naturally occurring evolutionary response to selection pressure by a mortality agent, which in our case would be a herbicide.

Heap runs the International Survey of Herbicide-Resistant Weeds, weedscience.org, which has been online for 21 years. Scientists around the world upload documented cases of new herbicide-resistant cases. A unique case is classified as a unique species by the site of action (mode of action). For example, a case from Manitoba that has wild oat resistant to Groups 1, 2, 8, 14 and 15 would represent five unique cases.

As of April 4, there are 467 unique cases (species x site of action) of herbicide-resistant weeds globally, with 249 species (144 dicots and 105 monocots). Weeds have evolved resistance to 22 of the 25 known herbicide sites of action and to 160 different herbicides. Herbicideresistant weeds have been reported in 86 crops in 66 countries.

Globally, there are over 1.4 million fields with confirmed herbicide resistance and approximately 11 new biotypes are discovered every year. Chronologically, the number of cases is on a steep increase. (See Fig. 1.)

The year 1946 saw the introduction of the first modern herbicides – synthetic auxins – which revolutionized weed control in cereal production. The first appearance of a well-documented case of herbicide resistance occurred in 1970. (In hindsight, there were actually several other cases, including one in Canada: wild carrot with 2,4-D resistance.) This first well-documented case was common groundsel from Olympia, Wash., where they were applying triazine (Group 5) between nursery plots. The resistance was of no economic consequence, but prompted researchers in Europe and North America to go looking in corn where triazine herbicides were relied upon for weed control, and indeed they found atrazine- and triazine-resistant weeds in the cornfields of North America and Europe.

Resistance is the inherited ability of a plant to survive and reproduce following exposure to a dose of herbicide normally lethal to the wild type.

There are two prerequisites for resistance evolution. First, there must be individual genes conferring resistance present in the population. There must be at least one resistant plant out there. Second, selection pressure must be exerted on those resistant individuals. Both of these factors must be present or resistance will not occur.

The original frequency of resistant individuals can vary enormously and is dependent on the herbicide as well as the weed. For some

ACCase Inhibitors (1)

Synthetic Auxins (4)

ALS Inhibitors (2)

PSII Inhibitors (5,6,7)

Note:

EPSP Synthase Inhibitors (9)

Inhibitors

Global Increase in Unique Cases

Number Resistant Species for Several Herbicide Sites of Action (WSSA Codes)

ACCase Inhibitors (1)

Synthetic Auxins (4)

ALS Inhibitors (2)

PSII Inhibitors (5,6,7)

EPSP Synthase Inhibitors (9)

Note: PSII Inhibitors Combined

Source: Ian Heap, WeedScience.org, 2016

Group 2 herbicides and kochia, the original frequency may have been as high as one in 100,000 individuals; for Group 9 (glyphosate) and kochia, it may have been as low as one in 100 million. Therefore, all efforts must be focused on reducing selection pressure on resistant individuals that might be present.

Herbicides do not create resistance. If individuals of the resistant biotype are present and we repeatedly use an herbicide to which they are resistant, then we select for that biotype and the numbers build up. Herbicides have just helped select out the resistant individuals (while

Source: Ian Heap, WeedScience.org, 2016

controlling the susceptible ones). Resistance is detected when a high proportion – usually greater than 30 per cent – of the population is resistant to the herbicide.

Weed seeds in the soil are often greater than 100 million seeds per hectare, and weed seedling populations are often greater than one million seeds per hectare. Scientific estimates suggest that depending on the herbicide group, there may be one resistant individual in 100,000 to one in 100 million. (See Fig. 2.)

• ALS inhibitors – 1 in 100,000

• ACCase inhibitors – 1 in 1,000,000

• Many groups – 1 in 10,000,000

• Auxins and glyphosate – 1 in 100,000,000

North America is leading the way with the number of cases. Western Europe, Asia, Australia and South America are all following the same trend lines. Eastern Europe is likely underreported. We know there are a lot more cases than are being reported. If we look in Asia, one thing I like to point out is that some countries are really on the rise in herbicide-resistant weeds. China, for many years, didn’t have very many herbicide-resistant weeds and they’ve had a sharp uptick in herbicide-resistant weeds recently. That’s because they have had a migration of people to the cities and they don’t have enough labour to control weeds by hand.

Wheat has the greatest number of herbicide-resistant cases, followed by corn, soybean, rice and cotton.

Factors influencing the evolution of resistance include:

1. Initial resistance gene frequency (for the particular weed/site of action combination).

2. Selection pressure (frequency and efficacy of herbicide use).

3. Number of individuals treated over time. Resistance is a numbers game. The more individuals you treat, the higher likelihood you’ll select for resistance.

4. Residual activity of the herbicide.

5. Genetic basis of resistance (degree of dominance of the resistance trait and the breeding system of the weed).

6. Fitness of the resistance trait.

7. Weed seed production. Weeds that produce more seed are more likely to become resistant.

8. Seed dispersal mechanisms. Weeds such as horseweed spread very quickly.

9. Seed longevity in the soil.

The reason there is so much Group 2 ALS resistance is related to the number of herbicides in that Group and the area treated, and the high numbers of which can result in resistance. There are 56 registered ALS herbicides, more than any other herbicide group, and they are used on a greater area than any other herbicide group. Group 2 herbicides (as well as Group 1 and Group 6 herbicides) are particularly prone to target site resistance (genetic mutations to the target enzyme that prevents the herbicide from binding and inactivating the enzyme).

North American, South American and, to some extent, Australian herbicide resistance research is focusing on glyphosate resistance. While overreliance of glyphosate in Roundup Ready crops is the main driver of glyphosate resistance, it is not the only cause, and only accounts for about one-half of resistant cases. The others are in orchards, vineyards and on fallow land.

Glyphosate-resistant crops were rapidly adopted in North and South America because they simplified weed control. Glyphosateresistant crops saved corn/soybean farmers from ALS inhibitor (Group 2), ACCase inhibitor (Group 1) and triazine (Group 5) resistant weeds. But simply relying upon glyphosate alone to control these resistant weeds was a recipe for disaster.

The first case of glyphosate resistance was in 1996, and there are now 34 cases of glyphosate resistance worldwide. (See Fig. 3.) This is with a herbicide that is generally not prone to resistance because there are not a lot of mutations at its site of action. But just through sheer amount of usage of glyphosate, resistance develops, and it is increasing at quite a rapid rate.

Seven weed species (horseweed, Palmer amaranth, sourgrass, tall waterhemp, giant ragweed, Johnsongrass and rigid ryegrass) account for about 99 per cent of the reported area infested with glyphosateresistant weeds.

The greatest economic impact is probably Palmer amaranth in the southern United States. Farmers are now using up to seven herbicide applications plus hand hoeing at a cost of up to $360 per hectare. Horseweed covers the largest area but is easily controlled with other herbicides. Glyphosate-resistant kochia is one that Western Canada should be worried about.

The biggest resistance challenges:

1. Multiple resistance – starting to get resistance to two or four or even 11 different sites of action, it is very difficult to control weeds.

2. Non-target site resistance – less predictable, very hard to identify.

3. Decline in herbicide discovery – haven’t seen the introduction of a new mode of action for over 30 years.

4. Overreliance on a few herbicide-resistant crops.

5. Farmers not adopting management strategies. Many have no experience in conventional weed control methods.

Any consistent practice to control weeds year after year will result in directed evolution towards survival. In a rice paddy in the Philippines, hand-weeding barnyard grass eventually selected for barnyard grass plants that looked like rice plants. The barnyard grass was resistant to hand weeding because it looked identical to a rice plant at the time of hand weeding.

The solution is to vary weed control practices and destabilize evolution. The whole message for herbicide resistance management is to be completely inconsistent with all your weed control practices.

Presented by Hugh Beckie, Research Scientist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Saskatoon.

Since 1975 the increase in herbicide-resistant weed cases has been fairly consistent, similar to global trends. In Western Canada, there have been about one and a half new, unique cases every year since 1975 when the ACCase or Group 1 Hoe-Grass herbicide came onto the market. In 2016, there are just over 60 cases, and Canada is number three globally in terms of the number of cases. (See Fig. 1.)

Breaking it down by province, the number of cases between Eastern Canada and Western Canada is quite similar. Ontario has 35 unique cases of herbicide resistance, Alberta 23, 20 in Saskatchewan and 22 in Manitoba. British Columbia has one and Quebec has three cases.

We’ve done herbicide-resistant surveys since the mid-1990s, and we were one of the first regional areas that conducted a regular systematic survey. Since the baseline survey that we did in the early 2000s, we documented that just under 50 per cent of all the cultivated land on the Prairies had resistant biotypes. The 2007 through 2009 survey estimated 24.4 million affected acres (see Table 1, p. 20).

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) is currently conducting a new round of surveys. Saskatchewan is completed and we’re planning to do Manitoba in 2016. I would expect the numbers will be around 38 million acres of weed infestation with resistance. The estimated cost is about $1.1 to $1.5 billion a year in terms of increased herbicide use and decreased yield.

A breakdown of the types of resistant biotypes shows 75 per cent of resistance is in wild oat, which is our most important weed species. There are also a number of Group 2 (ALS) resistant broadleaves. We expect those numbers to be quite a bit higher when the latest round of weed surveys are completed.

Group 1 resistance in wild oat is everywhere. From 2007 to 2011, there were 600 cases; but just over the last three crop years, we’ve had about 360 more cases. Growers are now submitting samples to find out which Group 1 herbicide still works on a field. They are at the stage that some of the Group 1 chemistries have failed, and they want to know if there is a chemistry in the Group that may still be effective. (See Fig. 2.)

Becoming more problematic is Group 1 and Group 2 resistance. We estimated about 20 per cent of land across the Prairies has this multiple resistant biotype. This really reduces herbicide options. In 2012 through 2014 there were 89 new cases reported.

Back in the 1990s we had a population from Manitoba with multiple resistances to Groups 1, 2, 8 and 25 – ACCase, ALS, triallate (Avadex) and flamprop (Mataven). We determined that it was metabolic resistance.

Our most problematic broadleaf weed is cleavers, but it could be tied with kochia. Based on submission of samples, 38 new cases of

1. Increase in unique resistant weed cases in Canada

Source: Ian Heap, WeedScience.org, 2016.

Fig. 2. Group 1 resistant wild oat

circle is number of cases. Source: Beckie, AAFC.

Group 2 resistant cleavers were reported in the last three crop years, similar to 2007 to 2011. It is all across the Prairies.

There is also Group 2 resistant wild mustard. In the Rosetown area almost every lentil field has Group 2 resistant wild mustard. Lentils are non-competitive so Group 2 resistance has a significant impact on pulse crop production. Some growers have to go out of pulses just to clean up their fields to get back into pulses. We need to find a way to diversify herbicide chemistry in the future, if possible.

In Western Canada, kochia is the only weed confirmed with glyphosate resistance (Group 9). Today, we estimate just over 100

Table 1. Estimated field area on the Canadian Prairies (acres) impacted by herbicide-resistant weeds 2007-2009

Group 1 + 8 wild oat 495,848

Group 2 + 8 wild oat 31,109

Group 1 + 2 + 8 wild oat 331,628

Group 1 green foxtail 2,420,830

Group 2 Persian darnel 94,563

Group 2 broadleaves 3,397,232

Source: AAFC.

cases in Western Canada, but again this is based on 2012-2013 surveys. It will be interesting to see how fast it spreads from the original areas. It has been found in lentil and canola fields in addition to chemfallow.

We did a study at the AAFC research farm at Scott, Sask., with the help of Eric Johnson, and also at Lethbridge, Alta., with Bob Blackshaw. At each site, 12 kochia tumbleweeds were fitted with GPS collars and let loose in the wind. Seed drop and distance travelled were measured. The amount of seed drop increased as the distance increased up to one kilometre. At the maximum distance, there was about 80 to 90 per cent seed dropped. That is about 100,000 seeds dropped by each tumbleweed. As the speed of the tumbleweed increased, more seeds were dropped as well.

Kochia is also an out-crossing weed, so its resistance can move with pollen. In a pollen movement study in Saskatoon, we found a sharp drop-off in pollen movement with distance. There was about 7.5 per cent out-crossing on average, very close to the glyphosate resistant kochia, but out-crossing still occurred at 96 metres. If we had measured out to 200 or 300 meters, I think we would have picked up some level of out-crossing at a low frequency. There was a strong directional influence that was well correlated with the wind direction.

Herbicide-resistant canola crops with Roundup Ready and Liberty Link systems have become a basis for weed management in Western Canada to manage Group 1 and Group 2 resistance in grass and broadleaf weeds. Today, varieties with glyphosate and glufosinate stacked traits are now available. Generally, I’m in favour of stacked trait crops

There isn’t a magic bullet coming to help deal with herbicide resistance.

because it gives growers another tool to manage their weeds. Of course, the devil’s in the details in terms of stewardship, but we have to give growers all the tools they need to manage resistance.

The Roundup Ready2 Xtend soybean system with glyphosate and dicamba (Group 4) stacked traits is now available in Western Canada. There is also the Enlist soybean system with glyphosate and 2,4-D (Group 4) but it’s not yet commercialized. These stacked systems are relying on the Group 4 synthetic auxins to a large extent to control resistant weeds.

Looking at Ian Heap’s weedscience.org website, out of the 32 biotypes with Group 4 resistance, there are 27 broadleaf weed resistance cases and five grass species resistant to quinclorac. The aster and mustard families account for 40 per cent of the broadleaf weed cases. They seem to be predisposed in terms of herbicide resistance. Inheritance is usually by a single dominant gene, which is the risk factor for rapid resistance evolution. We have various classes of synthetic auxins and cross-resistance among the classes is generally unpredictable, so we almost have to test every class for resistance.

Our latest confirmed case of resistance was found in late 2015 in southern Saskatchewan. The wheat field had Group 2 ALS and Group 4 synthetic auxin resistant kochia. The field had kochia everywhere. This population wasn’t only resistant to dicamba but also fluroxypyr, which is a key active used in various crops. We didn’t suspect glyphosate resistance but there is glyphosate resistance in kochia very close by; so given what we know of kochia gene dispersal, we will soon find three-way or four-way kochia resistance. This Group 2+4 biotype has been found in the northern United States for a number of years so it really shouldn’t be a surprise that we found it.

I can’t say enough about monitoring. We really have to keep our eyes open, and I also appreciate growers and industry submitting samples for testing because the field surveys miss a lot of the early cases. Certainly wild oat, cleavers and green foxtail are at risk of glyphosate resistance, so again that’s where monitoring and early detection comes into play.

I found through our surveys that growers who consistently implement best (integrated) weed management practices tend to have less resistance. We have to look into the human element of resistance management. How do we get growers, or push growers, to implement what we talk about regularly? I think the science of resistance management is mature, we just need growers to take the next step with academics and industry.

Presented by Neil Harker, Weed Scientist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lacombe, Alta.

We’ve put incredible selection pressure on wild oats for resistance. It’s our driver weed. It’s a weed that makes most of our herbicide decisions. In 2006 over $12 an acre on average was spent in Western Canada on wild oat herbicides, about $500 million annually. That’s more than double any other weed species as a weed target.

I am struck by how fast wild oat resistance occurred. Hugh Beckie’s three surveys in 2001 to 2007 to 2011 showed Group 1 resistance went from 11 per cent of our fields to 39 per cent to well over 50 per cent of our fields in Alberta. That’s very rapid and is indeed cause for concern.

Dale Fedoruk, an agronomist in central Alberta, illustrated the problems with herbicide resistance. He gave me some data on wild oat resistance from wild oat patches that had been treated with herbicides. The samples were tested for three Group 1 herbicides and three Group 2 herbicides. He also has crop rotation and herbicide application history.

Field 3 had 11 years of field history. Eight of the 11 years had a Group 1 herbicide applied. Ten of the 11 years have a Group 1 or a Group 2. In 2014 the field received both Groups 1 and 2. In 2010 there was some Fortress (Group 3 and 8). In 2009 it had glyphosate in Roundup Ready canola.

Resistant testing on the wild oat seeds from Field 3 found very high levels of resistant seeds with all of the Group 1 or 2 herbicides screened. None of the major Group 1 or 2 herbicide chemistries would be effective on these wild oat patches in wheat. That’s fairly sobering to think about because we always talk about resistance as something that’s coming. This isn’t the only field that’s like this so essentially we are losing a lot of herbicide tools.

What this means in wheat is that there are no post-emergent wild oat herbicides that would be effective. He still has soil-applied Avadex (triallate Group 8). However, in Alberta, John O’Donovan confirmed 34 sites with triallate resistant wild oats from 1990 to 1993. These fields had an average of 17 years of Avadex. O’Donovan has been back to some of these sites recently, and if Avadex hasn’t been used since, he thinks that there’s probably two to three years of susceptibility to Avadex before resistance builds back up.

There are integrated production practices that lower selection pressure for resistance. Crop and canopy health is important for weed competition, and is even possible in so-called weakly competitive crops like peas. Seed shallow for canola to get a good crop stand. You may not need to do a second in-crop herbicide application with a competitive canola crop.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Lacombe did a study in central Alberta where a lot of barley silage is grown continuously.

Note: 2005 (3-site means after 5 years).

Source: AAFC.

Three-year rotation of all Seebe barley, three different barley varieties, a rotation with triticale and a rotation with an oat variety were compared. The trial showed biomass of wild oats could be reduced simply by having a more diverse rotation, and this rotation wasn’t very diverse at all.

Some of the Prairie rotations can look pretty good. Wheat-canolapea sounds good but these rotations are all just summer annual crops. Wild oat and many other problem weeds are summer annuals so unless we do something different and introduce a silage crop or introduce a winter wheat, we’re really just telling these weeds they can just continue as normal. They have no trouble adapting or thriving in those systems.

Although barley silage is a summer annual crop, it adds diversity because it is cut earlier than a crop harvested for seed. Winter cereals are even better. They start growth in the fall, and by the time the wild oat is ready to emerge in the spring many growers don’t even need a wild oat herbicide. This takes away wild oat selection pressure with herbicides for an entire year. Doing the same thing over and over whether it’s winter cereals or summer annuals is not going to get us where we want to be. We need to rotate and mix things up. Perennial forages do that pretty well because they compete very well and before wild oat gets a chance to set seed, you cut them off.

Another integrated weed management trial at Lacombe compared continuous barley versus a barley-canola-barley-pea rotation, as well as short versus tall barley cultivars and normal versus 2X

seeding rates and different herbicide rates. Cumulative effects of these treatments in year five were measured. (See Fig. 1.)

The integrated practices provide additive benefits. Using tall versus short varieties reduced wild oat biomass. Doubling seeding rate reduced wild oat biomass. Using both tall varieties and double seeding rates provided a further reduction. Putting those practices in a crop rotation led to even further reductions. By doing one thing right, you can get a two to three times reduction in wild oat biomass. Do two things right and you get a six to eight times reduction, and doing all three together gives a 19-fold reduction in wild oat biomass.

But the problem with that rotation is that it uses all summer annual crops so it’s not really diverse. Another study put some real diverse rotations to the test. This was done at three sites in Alberta, two in Saskatchewan, and one in each of Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec.

It compared canola-wheat-canola-wheat to more diverse rotations. The typical canola-barley and canola-barley-pea-wheat rotations were included as treatments. More diverse rotations included early-cut silage and winter wheat along with canola and spring wheat. Herbicides were either applied at full rate or not applied. Seeding rates were 1x or 2x normal rates. The rotations ran for five years from 2010 through 2014.

Five of six treatments with no wild oat selection pressure in

three of five years did as well (wild oat emergence) as canolawheat-canola-wheat with full herbicide regime. Similar results for wild oat biomass were observed, where five of the diverse treatments did as well as putting on tremendous selection pressure with wild oat herbicides on the more conventional canola-wheat rotation.

Canola yield was measured in the fifth year. Canola-wheatcanola-wheat with full herbicide throughout the five years was one of the lowest yielding, probably because of low crop diversity and too much canola in the rotation.

In this study some of the wild oat seedbank numbers with treatments not using herbicides did increase, but there were four treatments with zero wild oat herbicides three years in a row where it was not significantly greater than the canola-wheat-canola-wheat rotation with full herbicide applications.

Overall, combining 2x seeding rates of early cut silage with 2x seeding rates of winter cereals and excluding wild oat herbicides for three to five years often led to similar wild oat density, above ground wild oat biomass, wild oat seed density, wild oat seedbanks and canola yield compared to a repeated canola-wheat rotation under a full wild oat herbicide regime.

Wild oat was also similarly managed after three years of perennial alfalfa without wild oat herbicides.

A cautionary conclusion in the study was that forgoing wild oat herbicides in only two of five years in exclusively summer annual crop rotations resulted in higher wild oat density, biomass and seedbanks. But where there was a winter cereal and high seeding rates, we were able to manage wild oat effectively.

In summary, some herbicides are being overused. Weed resistance continues to increase at a rapid pace and many popular wild oat herbicides are already less useful than they were a few years ago. In some cases you could say all of the popular in-crop herbicides are not available anymore for wild oats. Few or no new herbicide modes of action are being registered. Low diversity rotations are dominant and that’s the biggest reason for the situation we have. Herbicide-resistant canola did give us a reprieve but if we overuse that system we’ll also get resistance from different groups.

Economics is why people say they do what they do. So far weed resistance has not driven much integrated weed management adoption in Western Canada – that could change. In Australia, how many guys wanted to pull a chaff cart? Zero. How many do pull a chaff cart? Quite a few. How many want to burn their stubble? Zero. How many do in Western Australia? Fifty per cent of growers burn their stubble.

In terms of herbicide resistance, some fields are in serious trouble with more trouble on the horizon. We still have time to act. Those with vision will make some sacrifices now to preserve precious herbicide tools that are a relatively non-renewable resource.

Additional presentations from the 2016 Herbicide Resistance Summit will be included in Top Crop’s weekly e-news from June 8 to July 6. Subscribe to our weekly e-news, and receive additional presentations automatically each week.

Sign up today – agannex.com/e-newsletter-subscription

Pollen beetles could become a serious problem for Prairie canola growers.

by Carolyn King

The pollen beetle may look like a cute little bug, but it’s one of Alberta’s “most unwanted” pests. “It is one of those pests that we don’t have now but could have a fairly major impact on the canola industry,” says Scott Meers, insect management specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry.

In Europe, this beetle species (Brassicogethes viridescens) can cause serious yield losses in spring-planted canola crops. The adult beetles feed on canola pollen and buds, and the larvae feed inside the buds and open flowers, destroying the ability of the flowers to produce seeds.

So far in Canada, the pest is found only in the Maritimes and Quebec, but climate models show it could survive and even thrive in canola-growing regions across the country.

The good news is that researchers in Eastern Canada are already tackling the pollen beetle problem. “We’re actively working on this problem, and our goal is to try to have the tools ready to manage the pest before it becomes a crisis in Canada,” says Peter Mason, an entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Ottawa.

The adult pollen beetle is about the size of a flea beetle and is black with a metallic greenish tint. It was first recorded in Canada in the 1940s in Nova Scotia. In a study in the mid-1990s, scientists found numerous pollen beetles in patches of wild radish (a cousin of canola) in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. By 2001, the pest had spread into Quebec as far west as Saint-Hyacinthe.

In P.E.I., the beetle’s recent population levels appear to be linked to the amount of canola grown there. “A few years ago, canola production started increasing on the Island and we started to see more beetles. But canola production has really gone down now, and although we still have quite a few pollen beetles, the populations are not overly high,” says Christine Noronha, an entomologist with AAFC at Charlottetown.

When the beetle populations were very high, Noronha observed serious damage on infested canola crops. She adds, “One of the crops that can be grown to reduce wireworm populations is mustard, which belongs to the same family as canola. Because of the wireworm problems that we have, we might see an increase in pollen beetle populations because of increased mustard acres.”

In Quebec, other factors in addition to the number of canola acres may be playing an important role in the beetle’s population levels. According to Statistics Canada, the area seeded to canola in Quebec has fluctuated up and down over the past 10 years, ranging from 15,200 to 48,200 acres, with 29,700 acres in 2015. However, only recently has the beetle’s population surged.

“We began to see the pollen beetle in high numbers only in the last two or three years. Before that, it was just a species that we observed,” notes Geneviève Labrie, an entomologist with the Centre de recherche sur les grains Inc. (CÉROM). She suspects this recent population increase might be associated with warming climatic conditions that favour the beetle.

Her research shows the beetle is most common in the Bas SaintLaurent area, a region in eastern Quebec along the St. Lawrence River. This is the third-most important canola production area in the province. Labrie says, “About 2011, the pollen beetle appeared for the first time in that area, and now there’s a huge population. Between 2012 and 2015, we observed a 58 per cent increase in population in that area.”

The pollen beetle is also in the Saguenay–Lac Saint-Jean canolagrowing region, which lies about 200 kilometres north of Quebec City. However, the pest is not yet in Abitibi–Temiscamingue, the province’s most important canola production area. Labrie notes, “The beetle could cause big problems if it arrives there.” Abitibi–Temiscamingue is in northwestern Quebec and is adjacent to Ontario’s Temiskaming area, another region where canola is grown.

TOP: The pollen beetle larvae feed inside the canola bud.

Westward spread

Mason led a study published in 2003 that modelled the beetle’s potential distribution across Canada. Using long-term average weather data from 1961 to 1990, the model showed that Canada’s canola-growing regions have suitable to very favourable conditions for the beetle.

“Under present climate conditions, there is great potential for the beetle to move west into canola-growing regions in Ontario as well as the Prairies and, of course, that is what we really fear,” Mason says.

AAFC’s Owen Olfert and Ross Weiss have evaluated the effects of a range of possible future climate scenarios on the pollen beetle’s potential distribution and abundance. The modelling results indicate that if Canada’s climate were a few degrees warmer, then conditions would be further improved for the beetle in many areas, including much of the Prairies.

Given that the beetle could survive in Ontario and the Prairies, how might it get there? Mason says the possibility of storm events carrying the beetles westward is

remote because our weather events generally move from the west to the east. He thinks the most likely pathway would be human-assisted transfer, with the beetles hitchhiking on plant materials being carried on trucks or trains.

At present, the beetles don’t seem to be migrating into new areas very quickly under their own power, possibly because Eastern Canada doesn’t have the large expanses of canola production that are common in parts of the Prairies.

(Stainless Steel Components on Magnum-F™) 6" SIGHT GLASS POKE HOLE (on Magnum-F™ )

Mason notes, “The beetles have the potential to disperse on other species of brassica that they might feed on or if canola areas are kind of connected. For example, at the present time not much canola is grown from Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu in southern Quebec through to south of Peterborough in Ontario. So there is really no way that the beetle can move from canola crop to canola crop.”

Other brassica species include weeds like wild radish, stinkweed, shepherd’s purse and wild mustard, and crops like mustard, broccoli and Brussels sprouts. Labrie notes that a four-year survey on wild brassica plants along roads in western Quebec and southeast of Ottawa in June and July did not find any pollen beetles on the wild plants. Noronha is planning to examine the role of other brassicas in the beetle’s life cycle and population patterns in P.E.I.

Noronha and Labrie are studying the beetle’s life cycle and how it relates to canola growth stages in P.E.I. and Quebec. “The adults come out of hibernation early in the spring and feed on the pollen of different plants, but the larva can only survive on brassicas. The adults come into the canola crop only when they are ready to lay their eggs,” Noronha explains. “[In P.E.I.], the arrival of the pollen beetle in the canola crop is usually synchronized with the time when the flower buds are just forming on canola. Once the adults come into the canola crop, they will stay there and start feeding.”

The females lay their eggs in the flower buds, usually about two to three eggs per bud. After hatching, the larvae feed in the bud. Noronha says, “The larvae are really tiny. They have two larval stages, or instars, compared to some insects that can usually have four or more instars. So the [pollen beetle] larvae have quite a fast development.”

The mature larvae fall to the ground and then pupate in the soil. They emerge as adults later in the summer and feed on the pollen

of various plant species until they go into hibernation for the winter.

In Quebec, the beetles arrive in the canola crop a little later than in P.E.I. Labrie says, “Fortunately, in Quebec at present, the pollen beetle’s life cycle is not synchronized with the sensitive stage of canola [which is during stem elongation as the buds appear]. The canola plants are very sensitive to pollen beetles at that stage because the beetle puts the eggs inside the bud, and the larva will feed inside the bud and there will be no flowers at all.”

Instead, the beetles tend to arrive in Quebec canola fields between 10 and 30 per cent flowering. At that crop stage, a lot of pollen beetles would be needed to cause significant yield losses. However, Labrie worries that warming climatic conditions might enable the beetle to adjust its life cycle so that it would arrive in canola fields right at the sensitive crop stage, with the potential for very significant crop damage.

Noronha and one of her graduate students have been examining the effect of temperature on the timing of the insect’s life cycle.

“We’re trying to develop a degree-day model to see when the beetles emerge from hibernation and when they come into the canola crop, and whether that is related to temperature. We got some really good results [in 2014]. We did it again last year, but it was a strange year –we still had snow on the ground into May and June. So we’re going to do it again in 2016 to make sure our degree-day model is correct.”