TOP CROP MANAGER

NEW PULSE VARIETIES FOR 2016

Plant breeders bring improved varieties to market

PG. 22

IMAP IN PULSES

New technology allows enhanced breeding

PG. 66

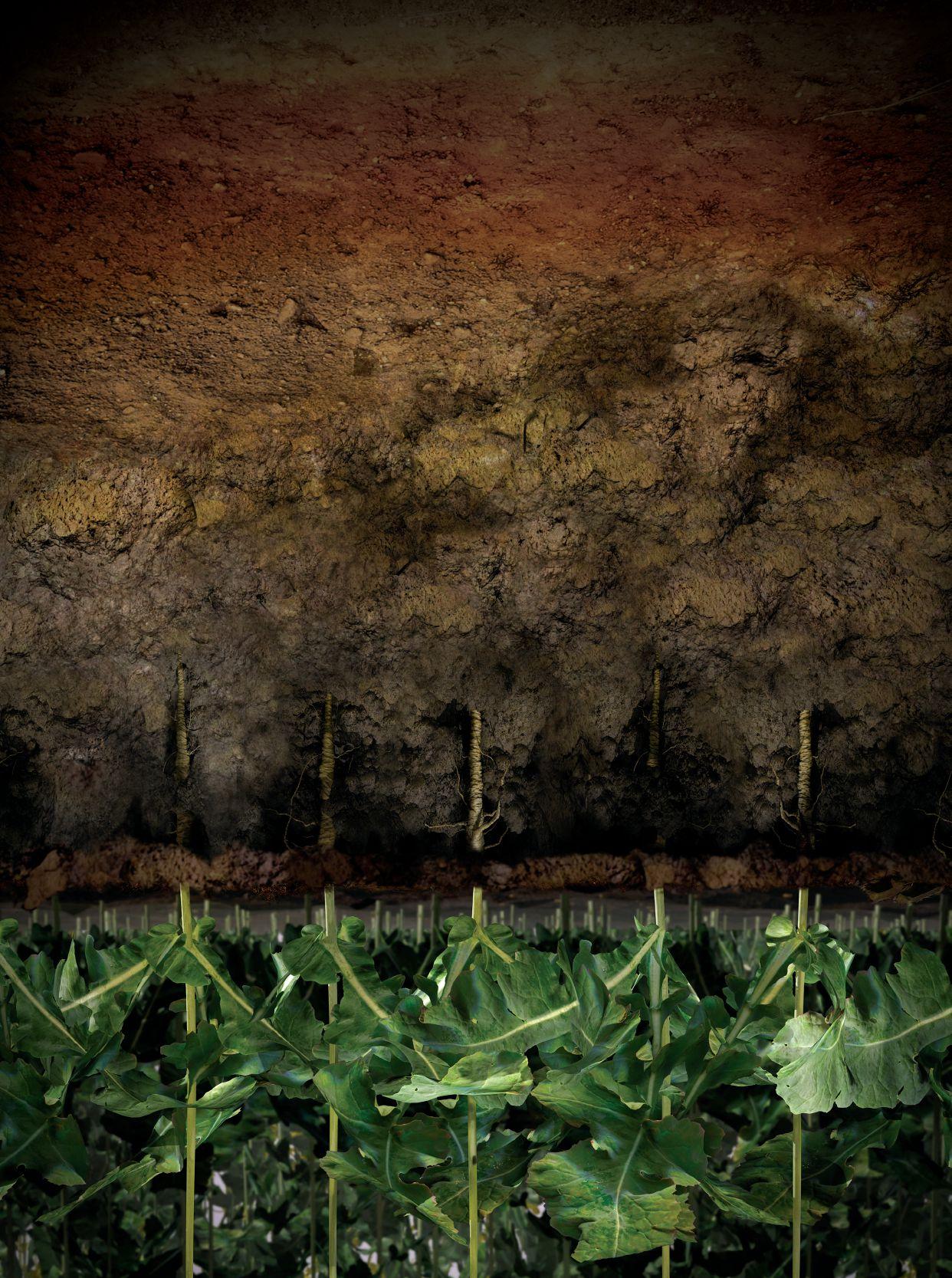

ROOT ROT AND FABA

Seed treatments can manage root disease

PG. 72

Plant breeders bring improved varieties to market

PG. 22

New technology allows enhanced breeding

PG. 66

Seed treatments can manage root disease

PG. 72

TIGER XP™ sets a new industry standard for performance. With a unique composition of sulphur bentonite and a proprietary activator, TIGER XP provides higher sulphate availability that addresses early season sulphate deficiencies and provides crops more sulphate throughout the growing season. With added dust suppressant coating for improved safety and handling, TIGER XP is optimized to outperform traditional sulphur products. Learn more at Tigersul.com

6 | Economics of short rotation legume forages

Forages in rotation provide higher net cropping system returns.

Donna Fleury

on soil and weather conditions.

Bruce Barker

Simulating hail damage to assess hail-rescue products for crops.

Carolyn King

Barker

22 New pulse varieties for 2016 By Bruce Barker

iMap technology in pulses By Julienne Isaacs

Toward healthier oats By Carolyn King FERTILITY

8 Developing phosphorus recommendations By Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P.Ag. 40 Determining plant available phosphorus By Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P.Ag. 42 Developing K recommendations By Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P.Ag.

84 Broadcast urea losses can be high By Bruce Barker

MACHINERY

62 2016 Canadian Truck King Challenge By Howard J Elmer

PRECISION FARMING

64 Managing yield data By Dale Steele, P.Ag.

SOYBEANS

81 What are the best soybean rotations? By Carolyn King

RESEARCH

80 Spotlight on fababean By Julienne Isaacs

PESTS AND DISEASES

28 Another root rot By Carolyn King

PULSES

20 The Goldilocks of pea production By Bruce Barker

48 Rotational-nitrogen credits in pulses By Bruce Barker CANOLA

52 Seed treatments improve emergence, yield By Bruce Barker

67 Reconciling canola seeding rate and seed size By Bruce Barker

JANET

Unless you’ve been under a rock over the latter part of 2015, you’ll have heard 2016 is the International Year of Pulses. Which means pulse crops such as lentils, beans, peas and chickpeas take centre stage this year throughout Canada and beyond.

Throughout the year, governments, organizations, non-governmental organizations and all other relevant stakeholders will work hard to heighten public awareness of the nutritional benefits of pulses as part of sustainable food production aimed towards food security and nutrition.

But what does IYOP 2016 mean to Canadian pulse growers? According to Pulse Canada, this is an unprecedented opportunity for Canadian pulse growers to showcase one of our major crops to national and international customers.

Canada is the world’s largest producer and exporter of dry peas and lentils, with 77 per cent of pulses grown here being exported to more than 150 countries around the world each year. Indeed, in 2014, Canadian pulse exports were valued at over $3 billion, with our biggest export markets being India, China and Turkey. Pulses are Canada’s fifth largest crop, after wheat, canola, corn and barley.

The International Year of Pulses, or IYOP, will focus activities this year on a few key areas of importance to producers. These include production and environmental sustainability; market access and sustainability; and health, nutrition and food innovation.

“IYOP will draw attention to important global issues related to pulses being grown here in Canada, which will ensure that we can sustain the growth of the industry and keep pulses competitive at the farm gate,” notes Pulse Canada.

Top Crop Manager salutes IYOP and Canadian pulse producers. And as in years past, we are proud to present our annual February issue, which focuses on pulse crops.

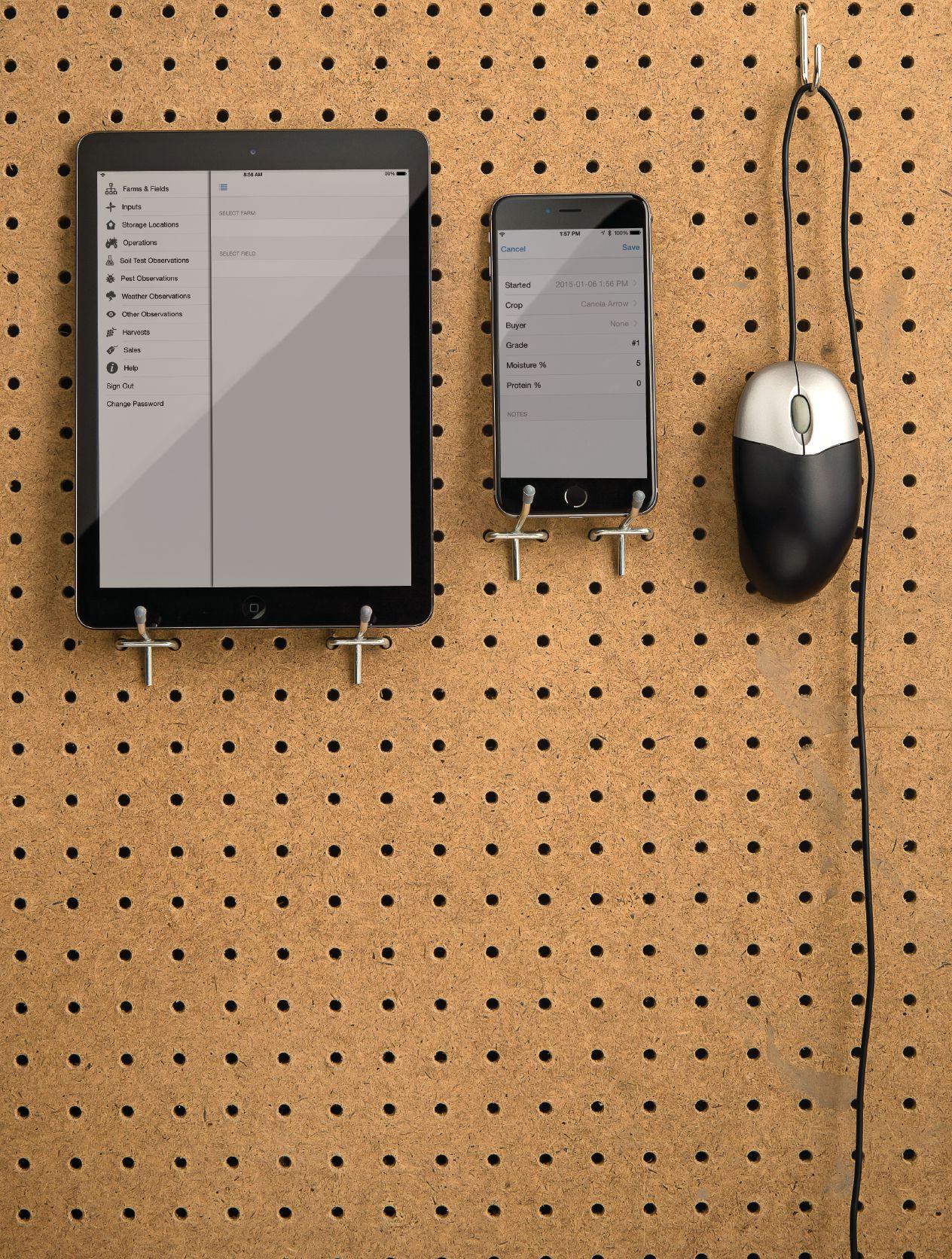

In this issue, we include stories that touch on pulse breeding, including new iMAP technology being studied at the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre. This technology has revolutionized pulse breeding in Canada, with growers the primary beneficiaries due to quicker delivery of improved cultivars. See more on page 66.

We also have stories that provide new information on some tough diseases, including a new root rot pathogen in pulse. Aphanomyces euteiches loves peas, lentils and waterlogged soils. Researchers are working diligently to provide new crop management tools to deal with this pest. See more on this topic on page 28.

And still on the subject of crop management, a recent study looked at the optimum agronomic package for pea production. The objective of the experiment was to determine which individual agronomic inputs contribute most to field pea seed yield, which combination produces the highest seed yield and economic return, and how plant population, leaf and stem disease, crop maturity, grain yield and quality are affected by input interactions. Read what researchers found on page 24.

On March 2, Top Crop Manager magazine presents the 2016 Herbicide Resistance Summit in Saskatoon. With this Summit, we hope to facilitate a more unified understanding of herbicide resistance issues across Canada and around the world, and to increase awareness that everyone engaged with agriculture has a role in managing herbicide resistance. While huge strides have been made to understand and deal with herbicide resistance, challenges remain. We hope to have some answers for Herbicide Resistance Summit participants come March 2. For more information or to register for the conference, visit weedsummit.ca.

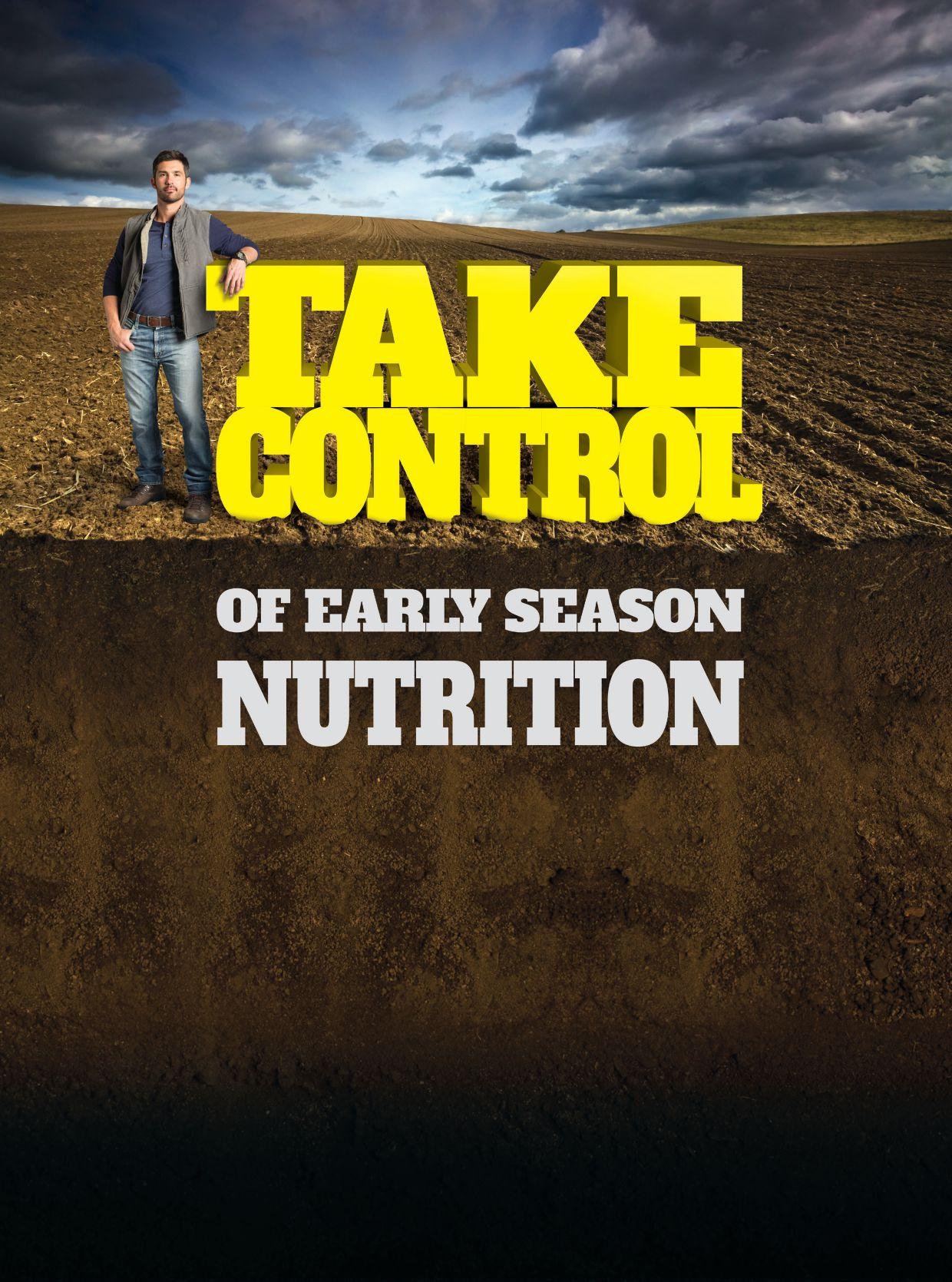

2S9 SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Crop Manager West – 9 issues February, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Brandt is celebrating $1billion in annual revenue and we’re thanking our customers by offering special rebates throughout the year. Visit thanksabillion.ca for details.

Designed for maximum capacity and speed, the Brandt 7500 HP GrainVac helps you operate at peak efficiency. With input from producers like you, we’ve refined our GrainVacs to include many innovative features only available from Brandt. With fewer moving parts, and premium build quality this GrainVac delivers unrivaled reliability and durability. That’s Powerful Value. Delivered.

Forages in rotation provide higher net cropping system returns.

by Donna Fleury

Including legume forages in short rotation in cropping systems can provide advantages and benefits for both crop and beef producers. Research shows that adding legume forages into an annual cropping rotation can be a viable option, providing high quality feed, good yields and reasonable levels of residual soil nitrogen (N) two years after legumes are taken out of a cropping system, providing an alternative way to build soil N. Overall, net returns after four years were higher for those rotations that included forages as compared to standard annual crop rotations.

Over four years from 2010 to 2014, different rotations were compared at four locations across Saskatchewan, including Swift Current, Lanigan, Saskatoon and Melfort. The objective of this collaborative study undertaken by the Western Beef Development Centre (WBDC) and three Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) research stations was to determine the amount of residual N from a two-year crop of alfalfa or red clover in a four-year rotation with wheat and canola. The rotations included: alfalfa-alfalfa-wheat-canola; red clover-red clover-wheat-canola; barley-pea-wheat-canola; and a control barley-flax-wheat-canola. The legume forages were terminated at the end of year two, followed by Unity wheat grown on all treatments in 2012, and Liberty Link (L130) canola on all treatments in 2013, with no additional N fertilizer applied to either crop.

“Overall, the economic analysis showed higher cumulative net returns from the rotations that included two years of legume forages, although the economics varied by location and soil zone,” explains Kathy Larson, beef economist with WBDC in Humboldt, Sask. “The Swift Current site suffered from drought conditions during the four-year project, which impacted the results. As well, the alfalfa rotations resulted in higher net returns for Melfort and Swift Current, while red clover yielded better returns at the Lanigan and Saskatoon sites, emphasizing how different legumes respond to different soil zones and climate

conditions across the province.”

In the economic analysis, average crop year prices were used. For 2010, forage was valued at just under $86/MT and barley at $152/MT. In 2011 forage was valued at just under $70/MT, peas at $8.49/bu and flax at $525/MT. For 2012, wheat was valued at $280/MT and canola at $428/MT in 2013. The stored N for use by subsequent crops (wheat and canola) was measured and valued using urea prices reported by the Alberta Farm Input Price Survey from 2009 to 2013, which averaged $0.58/lb, and was calculated as the Nitrogen Fertilizer Equivalent (NFE) value. In year one, the net returns on the legume forages were negative largely due to the establishment costs and typically lower harvest yields. However, after the second year, both alfalfa and red clover were very competitive with positive net returns and after four years, higher net returns than other rotations.

“In the second year, we were able to take multiple cuts on the forage crops without worrying about leaving any carryover, because the forage crops were terminated at the end of year two and seeded to wheat in year three,” says Larson. “The forage legumes provided revenues that exceeded the control rotation at all sites, except Melfort, which experienced exceptional yields on flax.” The flax yield at Melfort was 3456 kg/ha or 55 bu/ac, nearly double the five-year average yield (28.6 bu/ac) in the surrounding rural municipality. If flax yield had been in line with the five-year average, the alfalfa-alfalfa-wheat-canola rotation would have had the highest cumulative net returns at Melfort.

Overall, the cumulative average net returns for all sites after two years was $346/ha on alfalfa, $236/ha on red clover and

PRECISION APPLICATORS - Variable Rate capabilities and ISO compatibility are standard on our wide range of models.

LOWEST COST-IN-USE - Maximize productivity with wide flat spread patterns that minimize overlap and reduce fuel use.

OPTION RICH - Models available for fertilizer/lime,

or truck mount options available.

Phosphorus is deficient in about 80 per cent of Prairie soils.

by Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P.Ag.

Phosphorus (P), essential for optimum crop production, is deficient in about 80 per cent of Prairie soils. Soils deficient in P cause slower plant growth, delayed crop maturity and reduced yield. Fortunately, P deficiencies can be corrected with phosphate fertilizer. (Table 1 on page 10 shows the approximate amounts of phosphate (P2O5) uptake by various crops.)

Plant-available soil phosphorus is taken up from soil by plant roots. While soil testing can estimate plant-available soil P, they cannot predict with 100 per cent accuracy when crops will respond to added P fertilizer. The frequency of crop response is strongly influenced by environmental conditions, particularly soil temperature and moisture. For example, at research sites in Alberta, the observed response to P fertilizer, particularly with wheat, barley and canola, tended to be greater with wetter, cooler spring soil conditions. Generally, farmers can expect greater crop response to P fertilizer in a year with wetter and/or cooler spring conditions than in a spring with warmer, drier conditions.

It is important to note soil P levels have increased in some fields over

the years as a result of repeated annual commercial fertilizer P application or frequent livestock manure application. But, many farmers have been cutting back on P fertilizer application, causing soils to gradually become more deficient in soil P.

A province-wide Alberta research project was conducted with wheat, barley and canola, and found that 81 per cent of wheat sites, 90 per cent of barley sites and 72 per cent of canola sites responded to added phosphate fertilizer.

To optimize P fertilizer application, soil testing is the place to start. Make sure soil sampling is done properly (see Soil sampling and testing – doing it right in the September 2015 issue of Top Crop Manager) and the correct P soil test method is used (see Determining plant available phosphorus in this issue on page 40).

ABOVE: Wheat response to P fertilizer on an upper slope position in a variable rate fertilizer research study. Strip on the left side had no P fertilizer and strip on the right had 25 kg/ha of seedplaced phosphate.

Wheat (40

Barley (80 bu/ac)

Total

Seed 30 - 37

Total Uptake 40 - 49 Canola (35 bu/ac)

Total

Total

Source: Ross McKenzie.

Across the Prairies, response to P fertilizer has been correlated to the amount of soil P extracted from the soil. Soil test P correlation work has been with the 0 to 6 inch sampling depth. Ensure to sample the 0 to 6 inch depth separately from deeper depth samples to accurately determine P fertilizer requirements. Table 2 provides a guide for soil P levels for the modified Kelowna method. Generally, cereal and oilseed crops grown on soils with a very low or low P level have a high probability of response to P fertilizer, often in the range of 90 per cent.

Ortho phosphate, the form of P taken up by plants, is highly reactive with certain soil elements. Generally, soil P is slightly more available to plants in a pH range of 6.0 to 7.8. At higher pH levels (>7.8), calcium is more reactive with phosphate, creating forms that have slightly lower availability to plants. Magnesium acts in the same manner, forming less available magnesium phosphate compounds. In more acidic soils, aluminum and some other elements will increase in solubility and tie up soil P. This reaction limits the availability of inorganic P to plants at soil pH levels <5.5. Generally, I am far more concerned about P tie-up at low soil pH than higher soil pH. Normally, I do not adjust P fertilizer recommendations based only on soil pH when the range is between 5.5 and 8.0.

recommendations

Phosphate fertilizer recommendations for various crops are provided on the Alberta,

Saskatchewan and Manitoba departments of agriculture websites. Tables 3 (below) and 4 (page 12) are examples for spring wheat in Alberta. To determine the recommended rate of P, simply look at the soil test level in Table 3 and match it with the soil zone of your farm. For example, if you are growing wheat in the Thin Black soil zone and your soil test level is 35 lb P/ac, the recommended phosphate rate would be 30, 35 or 40 lb P2O5/ac, depending if seedbed moisture conditions are dry, moist or wet, respectively. Normally, I would use the moist to wet values for the recommendation.

From Table 4, a farmer could expect a 90 per cent probability of at least a 2 bu/ac yield increase and expect a 70 per cent probability of a 5 bu/ac yield increase. These probabilities are based on a number of years of field research. This information is also available for barley and canola on a probability basis, and P recommendations are provided for a number of other crops in Alberta Agriculture’s Agdex.

Phosphate fertilizer placement

Most field research has shown that placement of P fertilizer with or near the seed is best for most annual crops; therefore phosphate recommendations are typically based on P placement with or near the seed. However, care is needed not to exceed the safe seed-placed rate for each crop grown (see Table 5, page 12).

For cereal crops grown on soils that are medium to low in available P, seed-placed phosphate at recommended rates is equal to or better than banding near the seed and far superior to broadcast and incorporation.

For canola grown on soils very low to medium in available P, rates up to 15 to

Table 3. Phosphate fertilizer recommendations for spring wheat on a medium to fine textured soil based on the modified Kelowna soil test method.

* Seedbed soil moisture conditions at seeding D = 25%; M = 50%; W = 75% of field capacity.

Note: Recommendations are given for each soil zone at three soil moisture condition levels at the time of seeding.

Source: Alberta Agriculture Agdex 542-3 Phosphate fertilizer application in crop production.

{ And how its benefits go well beyond the seed. }

The first truly systemic pulse seed treatment with Xemium® , for broad-spectrum disease control

Increased seedling vigour both above and below ground

Enhanced ability to manage environmental stresses

More consistent and increased emergence, including under cold conditions

To find out what Insure® Pulse fungicide seed treatment and the benefits1 of AgCelence® can do for your lentils, field peas, chickpeas, dry beans, faba beans and flax, visit agsolutions.ca/insurepulse or contact AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273).

1 AgCelence benefits refer to products that contain the active ingredient pyraclostrobin. Always read and follow label directions.

AgSolutions,

Table 4. Approximate probability of a greater than 2 bu/ac and 5 bu/ac wheat response to phosphate fertilizer when following phosphate fertilizer recommendations

Source: Alberta Agriculture Agdex 542-3 Phosphate fertilizer application in crop production.

Canola 15 25 20

Pea 25 15 20

Note: Recommended safe rates vary among Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba departments of Agriculture.

Source: Provincial Agriculture publications.

20 lb/ac P2O5 can be seed-placed using a seedbed utilization of 10 per cent. Higher P rates should be either side- or mid-row banded at the time of seeding or banded prior to seeding. Seed-placed or banded fertilizer P on soils high in available P at rates up to 15 lb/ac of P2O5 may result in a crop response 30 to 50 per cent of the time, depending on soil zone and environmental conditions.

Phosphate fertilizer does not have nearly as strong a beneficial effect on pulse crops as these crops are fairly efficient at taking up soil P. Alberta research suggests pea is most responsive to P fertilizer when soil P levels are less than 30 lb P/ac (modified Kelowna method). Above this level, there is a relatively low chance P fertilizer will increase yield.

When soil test P levels are medium to high, an annual maintenance application of phosphate fertilizer should be considered to meet crop requirements and replenish soil P that is removed.

Canola has a relatively high demand for soil P. It is a non mycorrhizal crop and uses different means to aid in soil P uptake, leaving soil P more depleted compared to cereal or pulse crops. As a result, cereals and other crops that follow canola tend to be more responsive to P fertilizer. Often I suggest adding an additional 10 lb/ac of phosphate over and above the P recommendation for cereal or pulse crops, when following a good yielding canola crop.

For optimum annual crop production, an adequate supply of P close to the seed during the first six weeks of growth is best. Most annual crops take up the majority of their P requirements in the first 40 days after emergence. Placement of P in or near the seedrow with cereal and oilseed crops has traditionally been the best method used for P fertilization across the Prairies. Preplant banding of P with nitrogen has been found to be a good alternative method of application under certain conditions. However, under conditions of low to medium soil P coupled with low soil temperatures, “starter” P in the seed row is frequently very beneficial for annual crops. Finally, be cautious not to exceed the safe seed-placed fertilizer rate for each crop.

$7/ha for the barley-pea rotation. Due to the exceptionally high flax yields at Melfort, the cumulative average net return for the barleyflax rotation was $297/ha. The four-year cumulative net returns were highest for the forage legume-forage legume-grain-oilseed rotations in Saskatoon ($1435/ha), Lanigan ($1147/ha), and Swift Current ($482/ha). The cumulative net return for alfalfa-alfalfawheat-canola in Melfort ($2012/ha) exceeded the other forage legume rotations at the other locations; however, the control rotation (grain-oilseed-grain-oilseed) at Melfort had the highest cumulative net returns ($2650/ha), largely due to the exceptional flax yield.

“With the exception of Swift Current, the wheat and canola yields from the plots that grew alfalfa and red clover for two years outyielded the control rotation by 40 per cent on average,” Larson explains. “The amount of nitrogen fixed by the legumes varied by soil zone and climatic conditions with no NFE benefit measurable at the Swift Current site (except with the alfalfa-alfalfa-

wheat-canola in year four) due to drought stress.”

The NFE values for alfalfa ranged from $43/ha in Swift Current to a high of $460/ha in Melfort, while the NFE for red clover rotations were higher at Saskatoon ($239/ha) and Lanigan ($300/ha). These differences clearly illustrate that environment and soil zone can impact the amount of nitrogen fixed by the legumes. Taking four-year cumulative net returns and NFE values together, the alfalfa rotation was the highest at Melfort ($2558/ha) and Swift Current ($613/ha); however, the red clover rotation was higher at Saskatoon ($1764/ha) and Lanigan ($1577/ha). (See Fig. 1.)

“Overall, the project results show that including short rotation legumes can provide residual soil N for uptake by subsequent annual crops and the net returns are competitive with a typical rotation like the control (barley-flax-wheat-canola),” explains Larson. “The soil zone and climatic conditions have an impact on the yield and the legume’s ability to fix nitrogen.”

by Bruce Barker

ESN controlled release nitrogen (N) from Agrium is well proven in the U.S. Over 1000 site years of research have very well documented where ESN can be profitable, specifically on soils with risk of leaching, volatilization or denitrification losses due to excess moisture. Research is only beginning to identify where ESN fertilizer on corn makes sense in Western Canada.

“In Western Canada, corn growers most always put all their nitrogen on upfront as urea in some type of preseed – fall or spring –or side-banding application at seeding. Whether ESN is a good fit needs to be looked at on a case-by-case basis,” says Ray Dowbenko, agronomist with Agrium at Calgary. “If there is high loss potential, a split application of urea N or using ESN makes sense.

High yielding corn has high N fertility needs in the middle to later part of the growing season. Research by soil fertility specialist John Heard with Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Development (MAFRD) showed the maximum rate of N uptake in corn is 1.8 to 1.9 lbs N/ac per day between V8-VT and R1-R5 growth stages.

Unlike other small grains like wheat and canola, which have significant N needs right out of the starting gate and a shorter maturity, N uptake in corn is delayed to the V4 stage of growth, with increasing and large demands later in the growing season. That means N can be sitting in the soil for a longer period of time and at greater risk of loss.

From 2005 to 2007, Heard conducted one of the only Manitoba studies in a three-year research trial on ESN (44-0-0) compared to urea (46-0-0) at Carman and Reinland. ESN and urea at rates of 0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 lbs N/ac were compared with one additional treatment of 100 lbs N in a 50:50 mix of urea/ESN. All treatments were broadcast incorporated prior to, or shortly following, corn seeding. A fall treatment of 100 lbs N was broadcast and incorporated in the fall of 2005 for the 2006 Carman site.

“Fall applied is done by many Manitoba corn growers because they do not wish to work the soil in the spring and want to seed directly into a firm, moist seedbed. The single year we tried this [Carman in 2006] it was a very dry spring, and fall N worked well since there were probably minimal losses,” Heard explains.

The Carman soil is a well-drained Neuenberg loam soil. At Reinland, it is a Hochfeld fine sandy loam in 2005, Neuenberg fine sandy loam in 2006, and Edenburg clay loam in 2007. Significant rainfall fell early in 2005 and 2007, while 2006 was drier.

Heard reported: “There was no yield advantage to controlled

release N (ESN) compared to urea fertilizer. Springtime rainfall was insufficient to cause yield-limiting losses of applied urea. Benefits to controlled release N would be limited to situations when nitrogen losses are higher than observed in the study.”

In years when early spring conditions have higher rainfall, especially on well-drained soils, the potential for loss is higher, and a case for ESN or other controlled release N products could show a benefit over urea.

Research shows value of ESN

Dowbenko says ESN has the best fit where most of the N is applied

in advance of crop demand, and winter and spring is generally characterized by excess moisture. If the soil is sandy and subject to leaching, the benefit may be even greater.

The rate of N release for ESN is governed by soil temperature, which also influences corn growth. The rate that water and N move through the ESN polymer coating is slow in cold soils and increases as the soils warm up. This may help match N release with corn growth. Typically, about eight to 15 per cent of N is released in the first 10 days, 40 to 60 per cent in the first month and 85 to 90 per cent within 60 days.

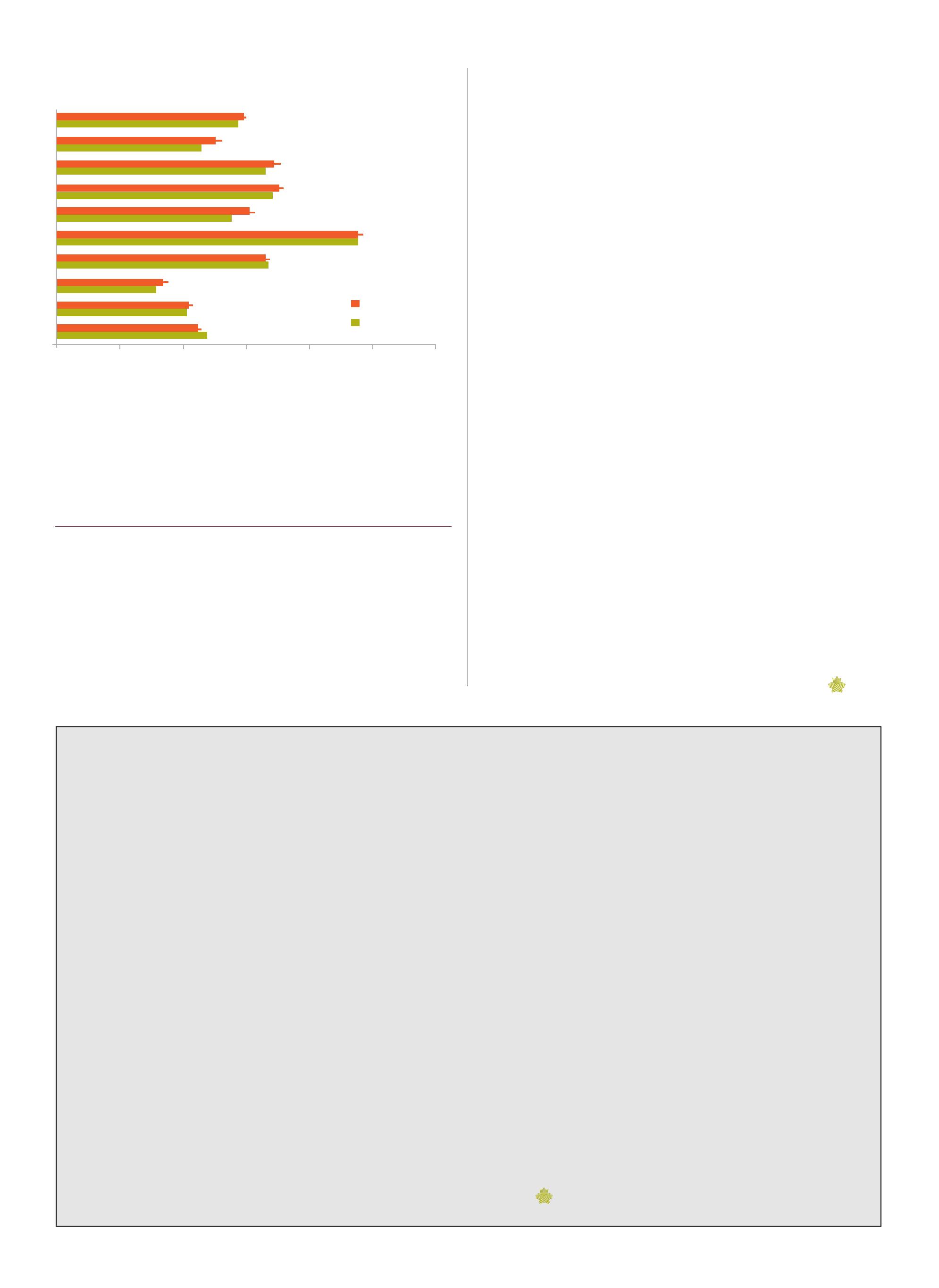

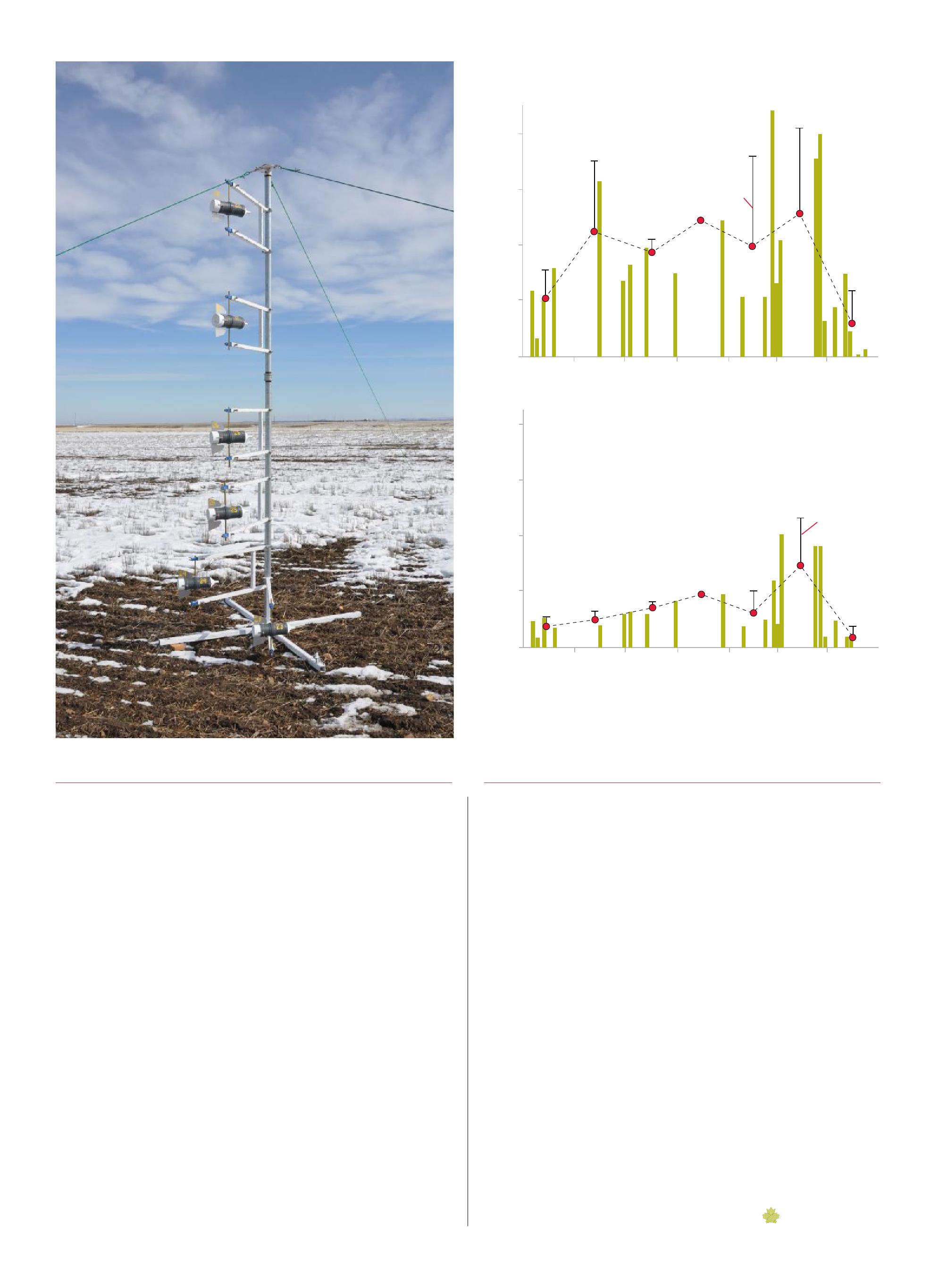

“In the U.S. we have over 1000 site years of data. We’ve seen a 19 bushel per acre better yield with ESN compared to a split application of urea at seeding and UAN side-dressed,” Dowbenko says. “In many comparisons, there are large yield advantages with ESN in the U.S.” (See Fig. 1.)

In Canada, few studies have looked at ESN performance under cool and humid climatic conditions. A three-year study led by Bernard Gagnon with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) on a clay soil near Quebec City compared the effect of ESN, a nitrification inhibitor N, dry urea, and UAN on corn yield. Urea, ESN and the nitrification inhibitor N were pre-plant broadcast and incorporated, and the UAN was applied as 30 lbs N pre-plant broadcast and the remainder of 120 lbs N side-banded at the six leaf stage of corn.

In the wet years of 2008 and 2009, ESN produced the highest yields, followed by the nitrogen-inhibited N (see Fig. 2, page 16). At the 150 lbs N rate, ESN gave a 10.3-bushel higher yield

1. Distribution of corn yield response to ESN

Compilation of all comparisons of pre-plant ESN with pre-plant conventional N sources at the same N rate.

Source: Agrium.

than urea, and three bushels more than UAN. In the drier 2010 cropping year, there was no difference between ESN, urea or the nitrogen-inhibited N.

An economic analysis by Gagnon revealed that ESN gave comparable net returns at equivalent N rate as UAN in wet years. Results indicated both the PCU and UAN treatments outperformed urea by approximately $38/ac in 2008 and $106/ac in 2009. The researchers concluded that controlled-release urea would be an additional option for farmers instead of side-dress UAN for fertilizing corn grown in Eastern Canada.

SJ3-VR and SJ7-VR StreamJet tips feature a unique variable orifice design to boost your productivity in the field. It’s like having 5 tip sizes in one.

• Support a wide range of rates including variable-rate, prescription map application with a single tip

• Simple design has no moving parts for long-term accurate and reliable operation

• Solid stream pattern directs fertilizer to the root zone and minimizes leaf coverage to prevent crop damage and yield loss

Response of corn grain yield to four fertilizer urea forms (dry urea, PCU polymercoated urea, NIU nitrification inhibitor, UAN) in 2009 on a clay soil.

Source: Gagnon et al. Can. J. Soil Sci. (2012) 92: 341-351.

More western Canadian research underway

In Manitoba, AAFC agronomist Curtis Cavers is researching ESN on corn. In 2014 and 2015, he had research sites located at Elm Creek (loamy fine sand), Carman (loamy very fine sandy) and Portage la Prairie (clay loam).

In 2014, Cavers had 10 treatments with a zero N check, N rates for urea/ESN of 60, 120 and 180 lbs N per acre broadcast and incorporate pre-plant; urea broadcast/incorporate pre-plant at 120 lbs N; UAN banded at stage V6-V8 at 60, 120, and 180 lbs N; urea broadcast at V6-V8 at 120 lbs N; and Agrotain-treated urea broadcast at V6-V8 at 120 lbs N. In 2015, he added in two more treatments that corn producers say they might use: urea broadcast immediately after seeding with no incorporation; and a dribbleband UAN at V6.

“We know these two additional treatments might not be the ideal choice for application, but sometimes producers might have to do it because of weather conditions,” Cavers says.

Once the three years of trials are completed, Cavers hopes to see some trends in which ESN best fits for corn growers in Manitoba. Based on what he has seen so far, he thinks ESN might have

a fit where soil and weather conditions are sub-optimal, such as heavy rain during the growing season and sandier soils.

“That’s part of the reason we are doing the research over three years, to get variable rainfall patterns on the different soil types and see the impact on the various fertilization methods,” Cavers explains. “Producers may not always have the best conditions to seed under, so we wanted to look at many different treatments over the three years.”

Dowbenko says while the research on the benefits of ESN is clear in the U.S. and Eastern Canada, the cooler soils and more variable rainfall patterns mean more work like Cavers’s is needed in Western Canada. With expanding corn acreage in Western Canada, Agrium, too, is embarking on ESN research on corn.

“With shorter season corn that matures earlier, we need to find out if ESN with controlled release is as important to match corn growth rates as in the U.S. with a longer growing season and higher yield potential,” Dowbenko says.

For now, Dowbenko refers growers to a matrix developed based on U.S. data, which shows the yield benefit of using ESN under various soil and precipitation expectations (see Table 1). If farmers grow corn in a heavy rainfall area or under irrigation, and with lower organic matter soils, ESN might make sense.

Currently, ESN is priced at approximately $0.20 lbs N more than urea. At a 120 lbs N/ac fertilizer rate, that means an additional $24 per acre cost. With corn prices around $4.30 per bushel, ESN corn yields would have to be 5.5 bushels per acre higher than if fertilized with urea.

Based on what he has seen, Heard sums up best where ESN could be of benefit in Manitoba. “My extension message is if it is a wet year or soil prone to wetness we might experience losses, especially to fall applied N. ESN would be expected to prevent that loss, leading to higher yield. In years that are normal or dry, N losses are insufficient to cause yield differences,” Heard explains. “It is up to the grower to assess their level of risk – they know the field, whether it is well drained or not – and then they can fertilize accordingly.”

Looking beyond just yield, Dowbenko says ESN offers some other benefits corn growers may consider. It gives flexibility in the application window, and could replace a V6 top dress with N application at seeding or even a fall ESN application under certain conditions. This flexibility could help offset some of the additional cost of ESN. ESN can also provide environmental benefits by reducing N loss to the environment.

Table 1. Yield benefit of using ESN under various soil and precipitation expectations

Expectations are based on 80% of N coming in the form of ESN.

Greater precipitation = 6 to 8 inches of combined rainfall in May and June (which the majority of the corn belt receives).

Higher organic matter represents more than 3% to 4%.

Areas with not enough data are based on theoretical expectations.

Source: Agrium

Take a stand against resistance. Arm yourself with the revolutionary residual broadleaf control of Authority – the only Group 14 pre-emergent herbicide. It’s your secret weapon for cleaner fields and higher yields.

FMCcrop.ca

Resistant or not, powerful Infinity ® herbicide provides you with the ability to take out the toughest broadleaf weeds in your cereals. With its unique Group 27 mode of action, Infinity helps ensure the profitability of your farm today and for years to come.

Managing herbicide resistance is everyone’s fight. Spray Responsibly.

Not too hot, too cold, too wet or too dry.

by Bruce Barker

What are the key environmental parameters that impact pea yield? On the surface, the easy answer is temperature and moisture. Get them right and you get a top-yielding crop.

But what is the right combination? That’s what Rosalind Bueckert, a professor in the plant sciences department at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) wanted to find out in an effort to better understand pea growth habits and to help improve pea breeding at the U of S Crop Development Centre (CDC).

“Pea cultivars are heat-sensitive so our goal was to investigate how weather impacted growth and yield for a dryland and an irrigated location,” explains Bueckert, who published the research in the Canadian Journal of Plant Science in 2015. “We explored relationships between days to maturity, days spent in reproductive growth – flowering to maturity – yield and various weather factors.”

Research in other countries had identified that high yield was related to early flowering, a large number of reproductive nodes and soil moisture availability during flowering. The longer the plant remained in the reproductive growth period, the higher the yield. Research had found that high daily maximum temperatures (31 C to > 34 C) during flowering for at least two to four days reduced yield due to abortion of buds and flowers, aborted young seed and potentially smaller seed. In Canada, though, the relationship between daily high temperatures, precipitation, and yield had not been explored.

Bueckert, along with colleagues Stacey Wagenhoffer and Tom Warkentin at CDC and Garry Hnatowich at Saskatchewan Irrigation Diversification Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at Outlook, Sask., utilized the nine years of Co-op variety registration trials at the dryland Saskatoon site and the irrigated Outlook site to look at environmental effects on yield. They measured days to flowering when 50 per cent of the plants in a plot had an open flower, days to maturity, disease rating and seed size. The nine years covered the range of weather patterns with some hot and dry, warm, or cool and wet.

Check varieties in each year were utilized and represented current popular varieties. For example, in 2009 the five varieties were Eclipse, Cutlass, CDC Striker, CDC Cooper and CDC Golden. Peas were grown using recommended production practices. At Saskatoon, pea was not sprayed with a fungicide except in 2005 and 2009 when disease pressure was observed. At Outlook, pea was sprayed every year with a fungicide at flowering followed by a second application 10 to 14 days later.

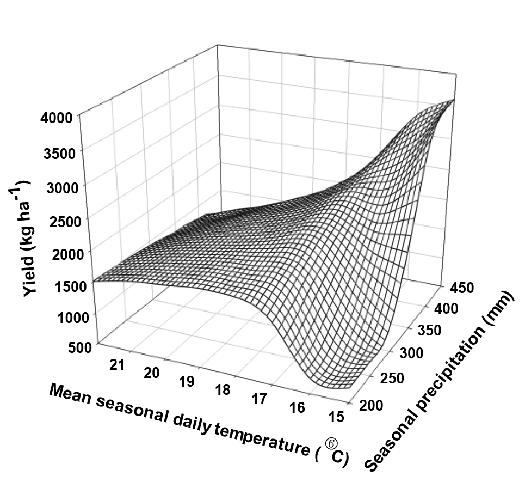

Fig. 1. Pea yield response surface as fitted by a quadratic regression model for mean seasonal daily temperature, seasonal cumulative precipitation (which would include irrigation) and the number of hot days (above 28 C).

Note: 1 bu/ac = 67.2 kg/ha. To convert kg/ha to bu/ac divide by 67 for field pea. 1000 kg/ha is about 15 bu/ac.

The data set has 1555 total combinations of temperature, precipitation and days above 28 C for a range typical of Saskatchewan, and includes a further 2 C increase in the range of mean seasonal daily temperature.

Source: Bueckert et al. Effect of heat and precipitation on pea yield and reproductive performance in the field. Can. J. Plant Sci. (2015) 95: 629-639.

Bueckert says the length of reproductive growth was an important factor in yield, and that heat stress or lack of moisture caused flower and reproductive node abortion. Conversely, the longer the pea spent in the reproductive growth phase, the higher the yield.

“Pea was sensitive to heat but heat units did not satisfactorily describe growth and yield in all environments,” reports Bueckert. “Strong relationships were observed between crop growth and mean maximum daily temperature experienced during reproductive growth, and between crop growth and mean minimum temperature.”

CONTINUED ON PAGE 23

K-Row 23 ® (0-0-23-8S) is an efficient, chloride-free source of soluble potassium and sulfur developed for starter and in-furrow (pop-up) fertilizer applications. It is effective, easy to blend and seed-safe when applied at recommended rates.

K-Row 23 contains 2.6 pounds of potassium (K 2 O) and 1.0 pound of sulfur in each gallon.

by Bruce Barker

Here’s a look at new pulse varieties available as Certified seed in 2016 and beyond. This information comes from pulse crop plant breeders, seed companies and Saskatchewan Pulse Growers.

FP Genetics has a new yellow pea for commercial growers to seed in 2016. Also, at the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre (CDC), plant breeder Tom Warkentin and his team are bringing several new varieties to market in 2016-2017 and beyond.

Yellow: New Abarth yellow pea from FP Genetics provides growers with competitive yield, good disease resistance and larger seed size. Abarth has medium maturity with very good resistance to powdery mildew, and fair resistance to mycosphaerella blight and Fusarium wilt. It has good lodging resistance with best in class standability for ease of harvesting.

Breeder seed of CDC Inca has strong yield potential in southern Saskatchewan and was first released to seed growers in 2015. It has good lodging resistance, medium seed size, round seed shape, medium protein content and good cooking quality. Certified seed of CDC Inca should first become available in 2018.

Green: Breeder seed of CDC Greenwater was first released to seed growers in 2014. It has strong yield potential and good lodging resistance. CDC Greenwater has medium seed size and round seed shape. Certified seed of CDC Greenwater should first become available in 2017.

Maple: CDC Blazer (3012-1LT) is a new maple pea variety with a lighter seed coat colour. It has higher yield than the other maple peas, similar to CDC Meadow, and seed size similar to CDC Rocket. Certified seed of CDC 3012-1LT will become available in 2018.

The CDC is the only lentil breeding institution in Canada, and is led by Bert Vandenberg.

Extra small red: CDC Roxy (3959-6) is a new variety that was released to seed growers in 2014. It has plump seed and is consistently higher yielding than CDC Maxim (103 per cent). It is not imidazolinone tolerant. Seed supply for this variety will be limited but it is one to watch for and should be commercially available by 2018.

New Abarth yellow pea from FP Genetics provides growers with competitive yield.

Small red: CDC Cherie is a newer variety released in 2012 and is not imidazolinone tolerant, but it is high yielding (109 per cent of CDC Maxim). Commercial seed of CDC Cherie may be available for 2016 in limited supply.

CDC Impulse (IBC 479) is higher yielding, especially in the south (108 per cent of CDC Maxim), with slightly larger seed than CDC Maxim, as well as a bit taller and a bit later. It is imidazolinone tolerant.

CDC Proclaim (IBC 550) is another higher yielding small red that is imidazolinone tolerant.

CDC Redmoon (3646-4) is a new variety similar to CDC Maxim with thicker seed and higher yields and is not imidazolinone tolerant.

CDC Impulse and CDC Proclaim were released to seed

growers in 2014 and CDC Redmoon in 2015 so Certified seed won’t be available for a few years.

Large green: CDC Greenstar is a newer large green lentil that has high yield potential but is not imidazolinone tolerant. Seed supply may be limited for CDC Greenstar for 2016.

Small green: CDC Kermit (3592-13) released in 2014 has seed similar to CDC Viceroy, better lodging, and yield is much higher than CDC Viceroy and CDC Maxim so far. Not imidazolinone tolerant. Limited seed may be available in 2017.

Plant breeder Bunyamin Tar’an at the CDC says the major objectives of the chickpea breeding program are high yield potential with acceptable seed quality characteristics, reduced production risk through improved resistance to ascochyta blight and early maturity, and plant characteristics for better crop management.

Kabuli: CDC Palmer is a new variety released in 2014 and Certified seed may be available in limited amounts by 2016. CDC Palmer is a high yielding kabuli chickpea cultivar with medium large (9-10 mm) seed size. The seed of CDC Palmer is a light cream-beige colour with typical ram-head kabuli seed shape. It is earlier maturing than CDC Orion and moderately resistant to ascochyta blight. CDC Palmer is well adapted to all current chickpea growing regions of Brown and Dark Brown soil zones of southern Saskatchewan and southeastern Alberta.

Desi: CDC Consul is a relatively new high yielding desi chickpea, and is an alternative to the production of small kabuli chickpea types. It has good resistance to ascochyta blight. CDC Consul is suited to all current chickpea growing regions of Brown (Area 1) and Dark Brown (Area 2) soil zones of southern Saskatchewan and southeastern Alberta.

Public dry bean plant breeding programs are at the CDC, Agriculture

and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Lethbridge and Morden Research Centres, and the University of Guelph. Parthiba Balasubramanian at AAFC Lethbridge focuses on developing cultivars of various dry bean market classes for irrigated production under both wide row (60 cm or higher) and narrow row (30 cm or less) spacing.

At CDC, Kirstin Bett is breeding dry bean for short season environments. The main breeding objectives include early maturity, improved pod clearance and high yield combined with market acceptability within market classes.

In addition to the publicly developed varieties at CDC and AAFC, private plant breeding companies, including GenTec Seeds, Seminis Vegetable Seeds, Globe Seeds and Rogers Brothers have also developed dry bean varieties suitable for Saskatchewan.

AAC Tundra, developed at AAFC Lethbridge, is a high-yielding, early-maturing great northern bean with an upright, indeterminate bush growth habit with long vines (Type IIb). It entered the commercial market in 2015. AAC Tundra has a large seed size and improved field resistance to white mould compared with the check cultivar AC Polaris. AAC Tundra is suitable for irrigated wide row production in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

AAC Burdett, developed at AAFC Lethbridge, is an earlymaturing pinto bean cultivar with an upright, indeterminate bush growth habit, lodging resistance, white mould avoidance and high yield potential. AAC Burdett, registered in 2014, is suitable for irrigated production in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

AAC Whitehorse, developed at AAFC Lethbridge, is a highyielding, early-maturing great northern bean cultivar with an upright, indeterminate bush growth habit, large seed size and partial field resistance to white mould. AAC Whitehorse, registered in 2014, is suitable for irrigated wide row production in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

AAC Black Diamond 2, developed at AAFC Lethbridge, is a high-yielding black bean cultivar with an upright, indeterminate bush growth habit, lodging resistance, shiny black seed coat and improved resistance to seed-borne common bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. phaseoli. AAC Black Diamond 2, registered in 2014, is suitable for irrigated production in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 20

The researchers found that when the mean maximum temperature was greater than 25.5 C at the dryland site, the number of days in reproductive growth was reduced to less than 35 days. More than 20 days above 28 C meant less time in the reproductive phase and lower yield for dryland pea.

“The threshold maximum temperature for yield reduction in the field was closer to 28 C than 32 C from [other] published studies, and above the 17.5 C mean seasonal daily temperature,” Bueckert explains.

At Outlook, irrigation helped to buffer the effect of heat, and the pea remained in reproductive growth for 35 to 40 days in a wider temperature range of 24.5 C to 27 C.

To put those temperatures into perspective, average climate data shows that from June to August, Saskatoon experiences

11.5 days above 30 C and Outlook 12.3 days.

“Clearly, mean daily maximum temperatures exceeding 25 C were associated with shortened reproductive phases of less than 35 days at both Saskatoon and Outlook,” Bueckert says.

On the Prairies, late-maturing varieties take about 94 days to mature, with medium maturity varieties around 90 days and the earliest at 86 days. Yet the normal frost-free period for Outlook is 123 days and 117 days for Saskatoon. Bueckert says plant breeders could lengthen maturity in pea by at least seven days without frost risk. If plant breeders could get the pea to flower earlier and longer (more indeterminate growth), yield potential could be increased.

Pea input study investigates optimum agronomic package.

by Bruce Barker

Farmers often wonder how to get the best bang for their buck with pea inputs. Seed, seed treatments, inoculants and foliar fungicide packages can quickly add up so they have to pay off.

Inspired by a canola input study conducted by research scientist Stu Brandt, formerly of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at Scott, Sask., the Western Applied Research Corporation (WARC) spearheaded a study at five sites in Saskatchewan and Manitoba to look at the optimum agronomic package for pea production.

“Many growers are managing pea inputs for high yield, but there wasn’t much research into which ones contributed the most or if the inputs had an additive effect on yield,” says Jessica Weber, WARC general manager.

The Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, and Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers provided funding for the trial. The objective of the experiment was to determine which individual agronomic inputs contribute most to field pea seed yield, which combination produces the highest seed yield and economic return, and how plant population, leaf and stem disease, crop maturity, grain yield and quality are affect-

ed by input interactions. Field trials were conducted in 2012-2014 at the Agri-ARM sites located at Scott, Swift Current, Melfort and Indian Head, Sask., with a fifth site at Minto, Man. added in 2014. Due to excess moisture in 2013, the trial at Melfort was terminated; data was collected from 12 site years.

The five inputs studied were:

• Seeding rate – 60 seeds/m2 vs. 120 seeds/m2 (roughly 1.8 bu/ac vs. 3.8 bu/ac)

• Seed treatment – no seed treatment vs. Apron Maxx

• Inoculant – liquid vs. granular (at recommended rates of each)

• Starter fertilizer – none vs. 34 lbs actual nitrogen (N) sidebanded

• Foliar fungicide – none vs. a two pass system (Headline EC and Priaxor DS)

The low input package was called the “empty” package and the high input package included all inputs at the highest level. Each input was tested individually and then in additive combinations of two, three, four and all five as the “full” package.

ABOVE: High seeding rates are the foundation of a profitable pea crop.

Source: WARC.

Weber says the researchers found a split in yield at the different sites around 45 bu/ac. Melfort, Scott and Minto sites had higher yields, while Swift Current and Indian Head had lower yields. The data was analyzed on the basis of high or low yield potential.

At the low yielding sites – the cause wasn’t identified if it was because of root rots, moisture stress or other factors – there was a consistent advantage to seeding at the higher rate. Inoculant type did not provide a difference in yield or economic return. Foliar fungicide application in lower yielding sites depends on growing season conditions if they favoured disease development. The higher seeding rate at the low yield sites still provided a $44 per acre economic return.

“Using a seeding rate that helps establish a good plant stand was very important on the low yielding sites,” Weber says.

effect with inputs at high yield sites

At the high yield sites, the higher seeding rate plus granular inoculant Table 1. Net revenue comparing treatments

plus double foliar fungicide application consistently produced higher yield and better economic returns. The biggest yield responses came from higher seeding rates and foliar fungicide application. Weber says the results were additive, meaning that yield increased when each additional input was included in the treatment.

Looking at the economic analysis in further detail, WARC ran net revenue comparing the treatments at the high and low yielding sites.

“These three inputs of high seeding rate, granular inoculant and foliar fungicide application provided an economic gain of $72 per acre over the empty package at the high yielding sites,” Weber says. (See Table 1.)

Given that higher seeding rates provided the basis for higher yield and increased net returns at both high and low yielding sites, Weber says establishing a good plant stand should be at the foundation of any pea crop. In this research, plant density was increased from an average of 56 plants per square metre at the low seeding rate to 102 plants per square metre with high seeding rates at the high yielding sites. At the low yielding sites, plant populations increased from an average of 52 plants per square metre at the low

seeding rate to 89 plants per square metre with high seeding rates.

On the low end, this range of densities is outside the traditionally recommended plant density. Current recommendations for pea growers are a target of 75 to 80 plants per square metre.

Interestingly, seed treatment for seedling diseases, which usually result in a better plant stand, did not produce a consistent yield improvement. This finding was unexplained and warrants further investigation.

“The results show that you should ensure your seeding rate is high enough to establish a good plant population,” Weber says.

WARC’s final summary report “recommends all farmers use seeding rates to target the recommended plant population to maximize yield potential. Under situations where the farmer targets relatively high yields, we recommend also using a granular inoculant to ensure nodulation and nitrogen fixation to provide sufficient levels of nitrogen to the crop. If the crop develops a thick canopy and/or disease develops, adding a foliar fungicide will protect and maintain the yield potential of the crop.”

The full report is available at westernappliedresearch.com

• Spray when you want with new PixxaroTM or ParadigmTM

• Two revolutionary Group 4 herbicides with ArylexTM Active

• Ultimate broadleaf weed control performance in wheat and barley

• Extreme productivity and convenience in the conditions you’ve got Go to the new dowagro.ca or call 1-800-667-3852.

This one is especially tough to manage.

by Carolyn King

There’s another root rot pathogen in the neighbourhood. It’s called Aphanomyces euteiches. It loves peas, lentils and waterlogged soils. And it’s tough to deal with because its resting spores can survive in the soil for many years. Although Aphanomyces has been present in Manitoba since the late 1970s, researchers only recently identified it in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Now they are at work on some new strategies for managing it.

Aphanomyces euteiches is an oomycete, or water mould, which is a fungus-like organism. It produces one generation in a season. “The oospores are the primary inoculum left behind in the soil or decaying host tissue. They are thick-walled, very resistant resting structures. Reports in the literature indicate they can survive in the soil from five to upwards of 20 years, depending on weather conditions,” explains Syama Chatterton, a plant pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta.

“A susceptible host plant releases root exudates and signals into the soil. Oospores respond to those signals and germinate. Through a complicated germination process, they eventually produce zoo -

spores, which are single cells with two flagella that help them swim.” They swim in soil water films to the host root and attach themselves to it.

“Then they produce hyphae, the fungal strands that penetrate into the root, and very rapidly begin colonizing it.” They break down the root tissues, feeding on the nutrients. Once they have used up all the nutrients in the root, they form oospores.

The whole life cycle can be completed in about three weeks if temperature and moisture conditions are ideal. Infection can occur at any stage of the host’s development, with the timing depending on the environmental conditions.

Soggy, warm conditions are ideal for infection. “Aphanomyces often occurs in a complex with other root rot pathogens, like Fusarium, Pythium and Rhizoctonia. They all like moist conditions, but

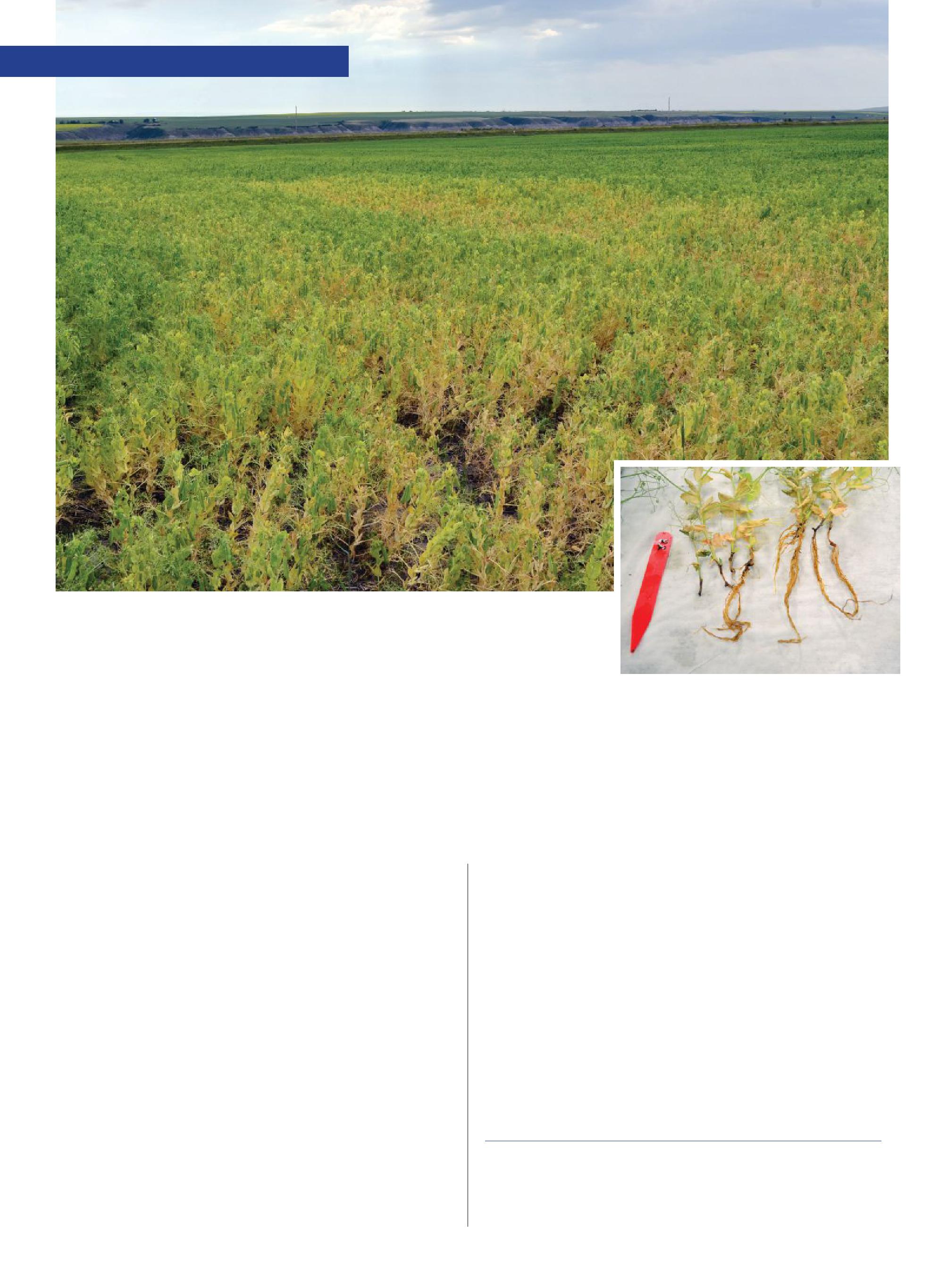

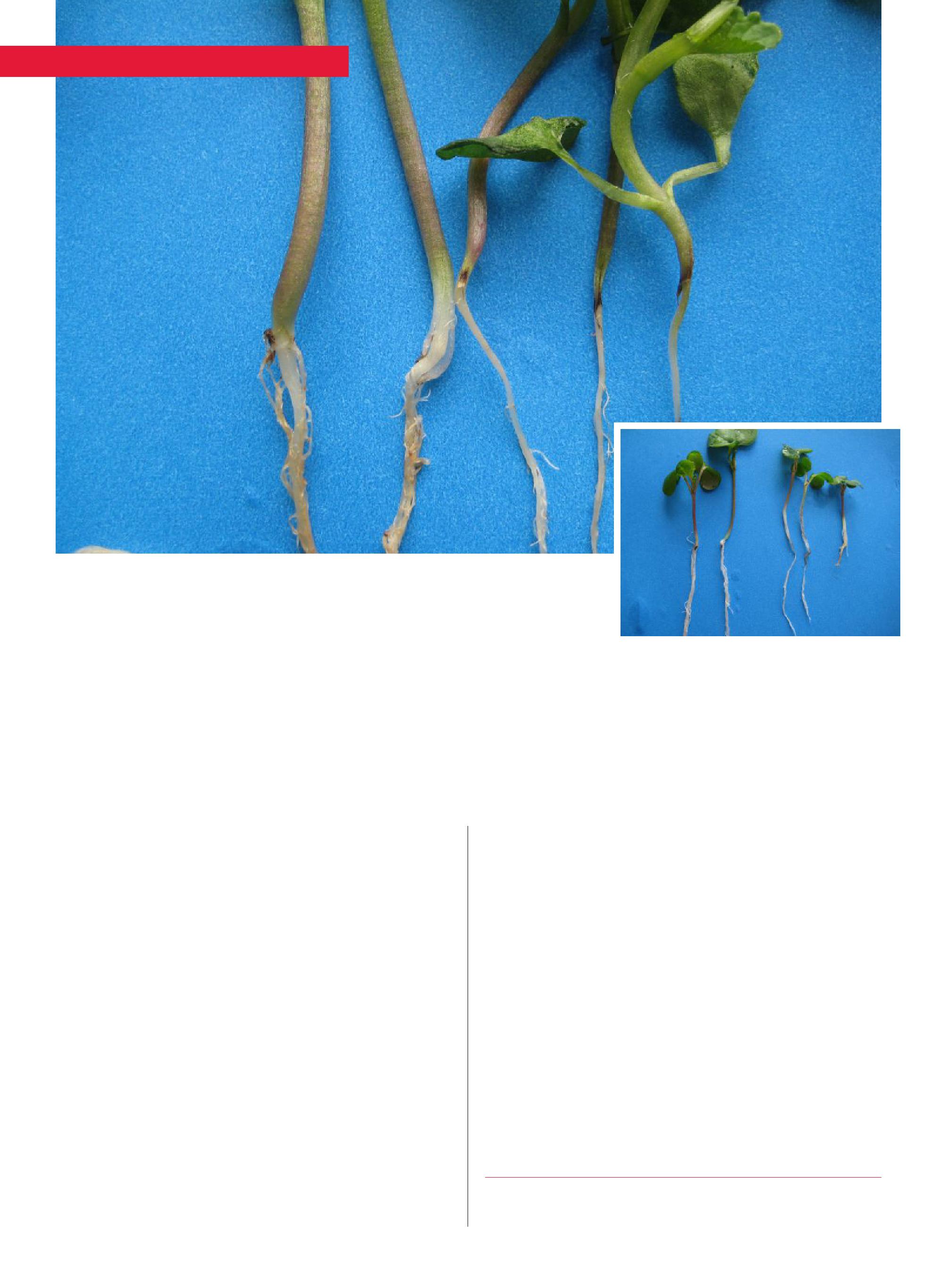

TOP: Patches of yellowing plants caused by Aphanomyces develop in the field 10 to 14 days after a significant rainfall event. INSET: Classical Aphanomyces root rot symptoms include honeybrown discoloration of the roots, constriction of the epicotyl, and complete decay of the roots in advanced stages.

Table 1. Conditions favouring infection by root rot pathogens

Aphanomyces 22 to 27

Fusarium 25 to 30 Moderate

Pythium 17 to 23 Wet

Rhizoctonia

Can damage at 18 but most aggressive at 24 to 30

Source: Faye Bouchard, Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture.

the oomycetes – Pythium and Aphanomyces – do even better with excess moisture,” says Faye Bouchard, provincial plant disease specialist with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture. On the Prairies, optimal soil temperatures for Aphanomyces infection (22 to 27 C) are typically reached by about July (see Table 1).

Chatterton has done Aphanomyces host range work with Sabine Banniza at the University of Saskatchewan. They have found that peas and lentils are both highly susceptible, whereas dry beans, fababeans, chickpeas and soybeans all have pretty good resistance. Alfalfa is somewhat susceptible, but some alfalfa cultivars are resistant. In 2015, Chatterton surveyed alfalfa crops grown on fields that have had peas in the rotation and found that the alfalfa roots were very healthy, suggesting that Aphanomyces is probably not a big concern for alfalfa.

“Aphanomyces has been around in Canada since the 1930s. But we just found it in Saskatchewan in 2012 in peas,” Bouchard notes. “Then we started doing more surveys for it, and Alberta started looking for it [and found it in 2013].” These surveys show the pathogen is fairly widespread in both provinces.

So why has Aphanomyces root rot suddenly become an issue? “My hypothesis comes down to three reasons that have all come together in a perfect storm,” Chatterton says.

“The first reason is that we’re reaching the point where most places in Alberta and Saskatchewan have had a good 25-year cropping history of either peas or lentils. So, if producers are using good rotational practices with a pea or lentil crop once in every four to five years, then some fields would have had a pea or lentil crop six to seven times, or more often if they have tighter rotations. If a field started with a low inoculum level…the amount of inoculum would gradually build up every time a susceptible host crop was planted because the oospores can survive for a long time. It would take about six to seven cropping cycles to reach a threshold level of inoculum where it is more widespread throughout the field and can cause visible damage,” she explains.

“The second reason is that we had several really wet springs in a row, and Aphanomyces is dependent on having saturated soils in order to infect. So you get increased infections because the environmental conditions are right, and the inoculum load in the soil increases quite quickly.”

And the third reason is a detection issue. “In previous root rot surveys, they were taking pieces of roots and plating them out on agar to determine the causal agent. But usually Fusarium over-grows Aphanomyces on the culture, so it can be really hard to confirm Apha-

Wide range of conditions

nomyces. I think it was Sabina Banniza who decided in 2012 to do a PCR test [which uses DNA markers specific to Aphanomyces euteiches]. That was the first time we were able to confirm Aphanomyces in [a Saskatchewan sample]. For our Alberta surveys in 2013 and onwards, we’ve expanded to using that PCR test. It has definitely improved detection of Aphanomyces.”

In Chatterton’s root rot surveys for 2013, 2014 and 2015, root rot was found in about 70 per cent of the surveyed fields each year, but disease severity varied greatly from year to year. The highest root rot levels occurred in 2014 because it was a particularly wet year. Chatterton says, “In 2014, we found that root rot was common and widespread throughout Alberta. The results from the PCR tests showed Aphanomyces was present in about 44 per cent of all fields in Alberta and in 60 per cent of fields that had root rot symptoms.”

The PCR analysis of the 2015 Alberta samples is not yet complete, but the field surveys showed root rot severity was definitely lower than in 2014, due to the very dry conditions in 2015.

The Alberta surveys also show that “Aphanomyces-positive fields are more common in the Black and Gray soil zones that are more typical of central Alberta. I think that is because they have had a pretty long history of pea production there, and those areas tend to be wetter than southern Alberta,” Chatterton notes. “In southern Alberta’s Brown soil zone in 2014, only about 18 per cent of the fields were positive.”

Although Saskatchewan didn’t do a formal root rot survey in 2015, the dry conditions in the spring and early summer likely reduced the amount of disease. Bouchard didn’t see as much root rot in the field, she didn’t get as many inquiries about it from growers, and fewer samples were submitted to the ministry’s Crop Protection Lab.

Trying to figure out which root rot pathogens you have in your field isn’t easy. Aboveground, they share the same symptoms, like poor emergence, wilting, yellowing and stunting. The belowground symptoms are usually a confusing mix caused by a complex of pathogens.

In the lab, if you infect plants with only Aphanomyces, the symptoms are distinctive. “The whole root system will have a honey-caramel discoloration. And the classical symptomology is that the epicotyl, which is the portion between the point of seed attachment and the green stem, becomes very tightly constricted and has that same honey-brown colour, which stops abruptly right at the green stem,” Chatterton explains. “Also, because the disease causes decay of the entire root cortex but not the vascular system, oftentimes if you pull up the plant from the soil, only the white vascular bundle is left and the rest of the roots are gone.”

Now in our 4th year, this two-day grain marketing conference will feature a current market outlook and interactive workshops for a fictional farm, complete with its own unique marketing challenges.

We will focus on advanced financial strategies, further education and standards for wheat basis and introduce a new tool for managing risk.

Register TODAY by calling 1-877-947-2549 (limited spaces available).

January 28-29 Saskatoon – Radisson Hotel, 405 Twentieth Street East

February 2-3 Red Deer – Sheraton Hotel, 3310 50th Avenue

February 11-12 Grande Prairie – Pomeroy Hotel, 11633 100th Street

February 23-24 Regina – Double Tree Hilton, 1975 Broad Street

March 1-2 Portage la Prairie – Canad Inns, 2401 Saskatchewan Avenue W

In the field, Fusarium species tend to colonize tissue that Aphanomyces has already started to infect, producing mixed symptoms. “The roots will look black and will be pruned away; Fusarium causes pruning of the roots. So you get an ugly mess of a black taproot and brown decaying lateral roots,” Chatterton says. “A good way to check for Fusarium is that it causes red colouring in the vascular system.”

When a root rot infection is advanced, it is especially difficult to figure out the original cause. “Not only are the roots rotting and the plant dying, but there could be multiple root rot pathogens as well as saprophytes, which are fungal organisms that live on the decaying and dead plant material,” Bouchard says.

She adds, “The other difficulty is that it is hard to separate out the damage that excess moisture causes to the crop, even without any pathogens present. Lentils and especially peas don’t like wet feet, when the plant is sitting in too much water. Those conditions alone will mean that the roots won’t develop as well and probably won’t form nodules as nicely, and the above-ground plant parts will probably be yellowing, stunting and wilting. But those wet conditions stress the plant, so if a pathogen is present, it will probably cause even more damage because of the stress.”

The best way to tell which root rot pathogens are present is to send samples to a diagnostic lab, such as Saskatchewan’s Crop Protection Lab, Discovery Seed Labs or BioVision Seed Labs.

Researchers in Alberta and Saskatchewan are tackling Aphanomyces from several angles. For example, at the University of Saskatchewan, they are working on developing resistant lines of peas and lentils.

To assess various Aphanomyces management practices in field peas, Chatterton initiated a large study in 2015. The study is taking place at Drumheller, Brooks, Taber, Lethbridge, Saskatoon, and two sites in the Red Deer-Lacombe area. Collaborating with Chatterton are Mike Harding and Robyne Bowness at Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, and Bruce Gossen at AAFC in Saskatoon. The Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund, Alberta Pulse Growers and AAFC, through the Growing Forward 2 Pulse Cluster, are funding the study.

At each site, the study is evaluating seed treatments, cultivar resistance and soil amendments. All sites are in producers’ fields. Six of the seven sites were selected because the fields had a high risk for Aphanomyces root rot; the Lethbridge site only had Fusarium root rot.

The seed treatment trials include different combinations of various products with activity against Fusarium, Pythium, Rhizoctonia and Aphanomyces. The seed treatment for Aphanomyces is ethaboxam (Intego Solo) – a new option that was given emergency use registration on field peas in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba in 2015.

The cultivar trials involve 20 pea cultivars, including some currently popular cultivars as well as some that are just about to be released.

The soil amendment trials are comparing three possibilities. “We searched the literature for any instance of something that might have some effect against Aphanomyces,” Chatterton explains. One treatment uses calcium, involving spent lime from the sugar beet industry; calcium has reduced zoospore production in greenhouse tests. Another treatment is Phostrol, a phosphite-based product, which has activity against oomycetes and provided some suppression of Aphanomyces in peas in the Pacific Northwest. The third treatment is the herbicide Edge (ethalfluralin), which showed Aphanomyces suppression in some preliminary work a few decades ago.

In the study’s first year, all the cultivars were susceptible to Aphanomyces root rot, as expected from previous greenhouse testing at the University of Saskatchewan.

“The seed treatments and soil amendments gave some promising results early in the season. By about five to six weeks, we could see some nice visual differences in root rot severity between some of the treatments,” Chatterton says. “But by the end of the growing season, the root rots were pretty similar across the board. Some treatments definitely yielded better than others, but we didn’t find any statistically significant differences between treatments.”

With only one year of data in an unusually dry year, it’s too soon to draw any conclusions. Also, Chatterton points to a key challenge with trying to do these types of field trials. “Because the distribution [of Aphanomyces] can be very patchy in fields, we had to choose sites with very high levels of Aphanomyces root rots. I think the inoculum load at some of these sites is too high, and at that level, disease management strategies often aren’t going to work. We could try to find sites that have a lower level of Aphanomyces, but then we won’t be certain that the inoculum has spread throughout the soil [so some plots might have different levels of inoculum].”

The researchers will be repeating the trials in 2016. Then, Chatterton hopes to get continued funding for several more years to determine how low the inoculum levels need to be for the practices to be effective.

In a project funded by the Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, Chatterton and Banniza are determining how much Aphanomyces inoculum is needed to cause different levels of the disease. “Right

now, you can submit samples to a lab to find out if Aphanomyces is present or absent, but the lab can’t determine if you have a low or high risk of getting Aphanomyces root rot,” Chatterton says.

“So we want to determine the amount of inoculum needed in the Brown, Dark Brown and Black soil zones to get low, medium or high disease levels. The idea is that interested testing labs could then offer a DNA quantification service for Aphanomyces and be able to use the DNA levels to determine if a field has a low, moderate or high level of Aphanomyces. That should help inform decisions on the length of time peas or lentils might need to be out of the rotation, or whether the grower could look at seed treatments or maybe a soil amendment treatment.”

At present, the best strategy is to submit plant or soil samples to a diagnostic lab to determine which root rots are causing problems in your fields, and if Aphanomyces is an issue, then use that information in your management decisions.

For fields that are highly infested with Aphanomyces, Bouchard and Chatterton advise waiting at least six years before planting peas or lentils again. Bouchard says, “Hopefully growers won’t have to do that on a permanent basis because there should be more options available as more research is done. One seed treatment, called Intego Solo, is available now, and there are potentially other treatment options coming down the pipeline. And hopefully we’ll get some resistant varieties.”

In the meantime, Chatterton suggests, “If you want to grow a pulse crop [on a field that is heavily infested with Aphanomyces], then fababeans are a really good option because they are really resistant to Aphanomyces.“

For fields with low to moderate Aphanomyces infestations, Chatterton recommends extending pea or lentil rotations from three or four years to perhaps five or six years. She adds, “Those are good fields for possibly using a seed treatment with activity against all the pathogens in the root rot complex, and that should help to boost your crop and keep it healthier.”

When your goal is fast, even crop emergence, trust Väderstad to help. With innovations like Patented Precision Openers and Wireless iCon™ Control, our Seed Hawk Seeding System places seed and fertilizer with unparalleled accuracy, in all soil conditions. Which gives you the greatest opportunity for higher yield.

Evolve your farm. Ask your equipment dealer about the Seed Hawk Seeding System, or visit SeedHawkSeeder.com Evolve your farm.

Leaving wheat stubble tall can produce higher yields – sometimes.

by Bruce Barker

Seeding canola into tall standing stubble doesn’t always produce higher yield, and carries some risk in some geographic locations, but under the right conditions, the practice can work.

Building on research conducted by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada scientists Herb Cutforth and Brian McConkey at Swift Current, Sask., University of Manitoba (U of M) graduate student Michael Cardillo expanded the research to look at tall stubble effects at 11 site-years across Western Canada.

“The climate is changing, and with increasing world population, we need to look at management practices that farmers can very easily implement that can help them produce more food,” Cardillo says. “Cutforth’s work at Swift Current showed that leaving stubble taller was very successful in improving the microclimate in tall stubble and producing higher yield under semi-arid conditions. We wanted to see if it would work for canola in a larger eco-climate across the Prairies.”

Cardillo’s research, conducted with Paul Bullock and Rob Gulden of the U of M, Aaron Glen of AAFC Brandon and Cutforth, included four locations in 2011 at Swan Lake, Man., Indian Head and Swift Current, Sask., and Grimshaw, Alta. In 2012, an additional three sites were added at Kenton, Man., and Falher and Lethbridge, Alta. The sites provided a broad range of eco-districts, climatic conditions and soil types.

Cereal stubble heights compared were 20 cm (7.9 in) and 50 cm (19.6 in). In some cases, the stubble was cut to height in the fall. In other cases, the stubble was left tall over winter, and then cut to the shorter height in the spring ahead of canola seeding. At

some sites, the tall stubble was flattened as a result of lodging from over-wintered snow, strong winds or mechanical damage during seeding. This created an additional factor to consider, and so the sites were further classified into whether the tall and short stubble treatments were intact or damaged.

“One of the risks farmers have to assess is whether the tall stubble might be flattened by snowfall, and how that will impact their ability to seed, and the potential for cooler, wetter spring soils,” Cardillo says.

The snowpack was assessed at Swan Lake and Indian Head in both 2011 and 2012 because the tall and short stubble was established in the fall. Overall, Cardillo says, as expected, the tall stubble had higher snow water equivalent than the short stubble.

“Historically, 30 per cent of precipitation falls as snowfall, so in a dry year, tall stubble can help recapture moisture loss coming into the spring,” Cardillo says.

In 2011 and 2012, growing season precipitation was above average at 10 of the 11 site-years, with generally wetter conditions earlier in the growing season and a gradual reduction in rainfall to below-average levels.

Canola emergence and plant populations were compared across intact and damaged sites for both tall and short stubble. Plant populations were greater in intact tall stubble than damaged tall

ABOVE: Intact stubble (left) produced significantly higher canola yields than damaged stubble (right).

and rewards.

Site-years where both the tall and short stubble remained intact for (a) emergence rate (%), (b) canola plant population, (c) biomass, and (d) yield. Note: Emergence rate includes 3 site-years with intact tall and short stubble all from the 2012 growing season; all others include 6 site-years with intact tall and short stubble from both 2011 and 2012. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. Capital letters indicate significant differences between treatments across all sites at P=0.05.

Source: Cardillo et al. 2015. Stubble management effects on canola performance across different climatic regions of Western Canada. Can. J. Plant Sci. 95: 149-159.

stubble. But for short stubble, the plant population was significantly higher in the damaged stubble. On the intact stubble sites, there was no significant difference in plant populations between tall and short stubble.

“The wet spring conditions provided good seedbed conditions in the intact stubble treatments, and resulted in good stand establishment at the intact stubble sites,” Cardillo says.

Canola yields were significantly higher in the intact stubble rather than the damaged stubble, for both tall and short treatments. Cardillo explains this is likely due to the soil warming and drying more quickly in the intact stubble than on the sites where the stubble was flattened on the ground. The tall intact stubble sites also had significantly higher yield than the short intact stubble treatments.

“There was enough moisture stress later in the growing season to provide an advantage to the tall stubble. The tall stubble provided a better microclimate with reduced evaporative water loss, which resulted in higher yield,” Cardillo explains. (See Fig. 1.)

Cardillo says results of the research show both the risk and rewards of leaving stubble tall prior to seeding canola the following spring. In areas with typically heavier snowpack and wetter spring conditions, tall stubble may be flattened in the spring, slowing soil warming and making seeding difficult. Short stubble may also be flattened and suffer lower yields as well, but with less straw to contend with short stubble may present fewer seeding challenges.

In areas where snowfall is lower and growing conditions drier, the potential for higher canola yields when seeded into tall stubble is well proven by Cutforth’s and Cardillo’s research. In these areas, tall stubble will usually remain standing overwinter, thus capturing more snow and providing a better microclimate, resulting in higher yield.

“Leaving stubble tall is a nice useful tool for farmers. But it isn’t written in stone. You don’t have to do it every year. It’s a judgment call. Farmers can assess soil moisture conditions at harvest and decide if they want to take the risk of leaving stubble high. And you don’t have to cut at 50 cm. Maybe there is less risk of lodging at 30 cm, or maybe a greater advantage at 60 cm. It is a potentially good management practice that has flexibil-

by Bruce Barker

In the short term, farmers have moved to a canola-wheat rotation as the most popular rotation on the Prairies. Driven by economics, this rotation has proven profitable – but at what cost?

Researchers at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) conducted research from 2008 to 2013 to determine the effect of canola rotation frequency on canola seed yield, quality and pest impacts. The results were published in the Canadian Journal of Plant Science

The objective of the study was to determine the effect of canola rotation frequency on canola pests (weeds, blackleg disease and root maggots), seed yield and quality in a six-year, all phases, rotation study at five sites in Western Canada. From 2008 to 2013, continuous canola and all rotation phases of wheat and canola or field pea, barley and canola were conducted at five Western Canada locations. LibertyLink and Roundup Ready canola were grown. Fertilizers, herbicides, and insecticides were applied as required. (See Table 1.)

The five sites were at Lacombe and Lethbridge, Alta., and Melfort, Scott and Swift Current, Sask. The crops were directseeded on no-till plots. Most fertilizer was side-banded 0.75 to 1.5 inches beside and 1.2 to 1.6 inches below the seed row with small amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus also placed with crop seeds. Seeding was performed with air seeders equipped with knife openers, and crops were seeded at optimal depths in nine to 11.8 inch rows.

In the research, AAFC research scientist Neil Harker did not observe any significant rotation frequency by canola cultivar interaction, so all yield data was averaged across variety, and herbicide

type. Yields were also averaged across location. An average of 3.5 to 6.4 bu/ac (200-360 kg/ha) increase was seen for each year that a wheat, barley or pea crop was added to the rotation.

“Canola yields were always improved by adding wheat or field pea followed by barley to the rotation,” cited Harker in the journal article. “These results are consistent with many other studies suggesting canola yield improvements with increased rotational diversity.”

Looking at the more diverse rotation of lentil-wheat-canolapea-barley-canola, the researchers did not find a yield advantage compared to a field pea-barley-canola rotation. Seed oil or protein concentration and oil quality were not impacted by rotation frequency (see Fig. 1).

The higher canola yields with more diverse rotations were attributed to decreasing blackleg severity and incidence, and decreasing root maggot damage.

Blackleg severity and incidence were both strongly influenced by canola rotation frequency with blackleg severity and incidence increasing as canola rotations tightened. Despite using canola rated as resistant in the study, blackleg disease was worse with short rotations. The authors believe it may reflect a breakdown in cultivar resistance or at least a gradual erosion of resistance over time. This is supported by other research that found changes in blackleg virulence with high disease severity in some cases, usually associated with shorter rotations.

Root maggot damage also increased as canola was grown more

ABOVE: Fig. 1. Canola yield response to rotation frequency Note: Means are averaged over glyphosate- and glufosinateresistant canola. Wheat was the rotational crop for a one-year rotation break; field peas and barley were the rotational crops for a two-year rotation break.

1-in-3

1-in-3

1-in-3

1-in-3 RR-phase 2 Pea

1-in-3

1-in-3

w Data from canola (C) plots proceeded by canola, wheat (W) or field pea (P) and barley (B) were collected at the completion of the following rotation sequences: C_C_C, C_W_C or P_B_C (2010); C_C_C_C, W_C_W_C or C_P_B_C (2011); C_C_C_C_C, C_W_C_W_C or B_C_P_B_C (2012); and C_C_C_C_C_C, W_C_W_C_W_C or P_B_C_P_B_C (2013).

Source: Harker et al. Can. J. Plant Sci. (2015) 95: 9-20.