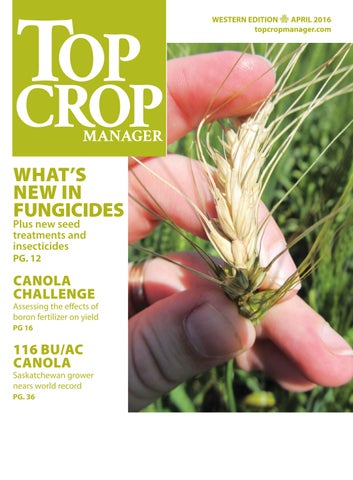

TOP CROP MANAGER

WHAT’S NEW IN FUNGICIDES

Plus new seed treatments and insecticides

PG. 12

CANOLA CHALLENGE

Assessing the effects of boron fertilizer on yield

PG 16

116 BU/AC CANOLA

Saskatchewan grower nears world record

PG. 36

Plus new seed treatments and insecticides

PG. 12

Assessing the effects of boron fertilizer on yield

PG 16

Saskatchewan grower nears world record

PG. 36

5 | Use caution with foliar fungicides Early foliar fungicide applications on durum not worthwhile.

By Bruce Barker

8 | Early sclerotinia forecasting Pilot project tests sclerotia-depot method across Western Canada.

By Donna Fleury

18 | Drought, deluge, drought, deluge… Weathering the storm of very variable weather on the Prairies.

By Carolyn King

JANET KANTERS | EDITOR

Crop diseases, a major cause of famine, have always been diagnosed by visual inspection, though scientists today also use microscopes and DNA sequencing. But the first line of defense is still the keen eyes of farmers around the world, many of whom do not have access to advanced diagnostics and treatment advice.

To address this problem, scientists from Penn State University and EPFL, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Switzerland, are releasing 50,000 open-access images of infected and healthy crops. These images will allow machine-learning experts to develop algorithms that automatically diagnose a crop disease. The tool then will be put into the hands of farmers – in the form of a smartphone app.

The entire world depends on a stable food supply. Global population is predicted to reach nine billion by 2050, and the need for food security is becoming increasingly urgent. Meanwhile, crop diseases continue to plague humanity, causing mass starvations. The challenge, then, is to grow enough food while ensuring that we don’t lose it to pests and diseases.

The Irish potato famine alone (1845-1847) killed over a million people when the water mould Phytophthora infestans caused a blight that decimated the country’s crop. Today, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that crop disease annually reduce potential yields by as much as 40 per cent.

Marcel Salathé, associate professor at EPFL and formerly a faculty member at Penn State, and David Hughes, assistant professor of entomology and biology at Penn State, are now fortifying the first line of defense against crop disease by exploiting smartphones. The scientists are releasing an open-source database containing 50,000 images of infected and diseased plants.

The idea behind releasing the open-source image database is to provide software developers with the “raw materials” to build machine-learning algorithms, according to Salathé. He explained that machine learning is a computational way of detecting patterns in a given data set to make inferences in another, similar data set.

What Salathé and Hughes want to do is to apply these techniques that were developed by computer scientists to the problem of recognizing and diagnosing crop diseases. Algorithms with sufficient accuracy will be incorporated into smartphone apps, allowing farmers to snap pictures of their infected crops and get instant diagnosis and treatment advice.

For the two scientists, this is a natural evolution of their website, PlantVillage (plantvillage.org), one of the world’s largest free libraries of science-based knowledge on plant diseases. It covers 154 types of crops and over 1,800 diseases – and it is still growing. “In addition to being a library, PlantVillage is a network of experts who help people around the world find solutions to their problems,” Salathé says. “Our goal is to let the smartphone do most of the diagnosis, so that human experts can focus on the unusual and difficult cases.”

The smartphone app is the next progression in this evolution, utilizing the imaging capabilities and connectedness of smartphones to automate the recognition of plant diseases. The bottleneck in the process is training algorithms to recognize diseased and healthy crops. Despite how affordable and accessible digital photography has become, finding enough publicly available images of crop diseases to train algorithms has been impossible until now.

“This is a truly exciting venture,” Hughes says in a news release. “The Internet and mobile platforms have transformed many aspects of human society. Through these online competitions and crowdsourcing, we want to transform that cornerstone of human societies - how we grow food.”

dkleer@annexweb.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

CIRCULATION

email: rhtava@annexbizmedia.com Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3555 Fax: 416-510-5170

Mail: 80 Valleybrook Drive, Toronto, ON M3B 2S9

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues February, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East – 7 issues February, March, April, September, October, November and December – 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada – 2 issues Spring and Summer – 1 Year $16.50 Cdn. plus tax All

by Bruce Barker

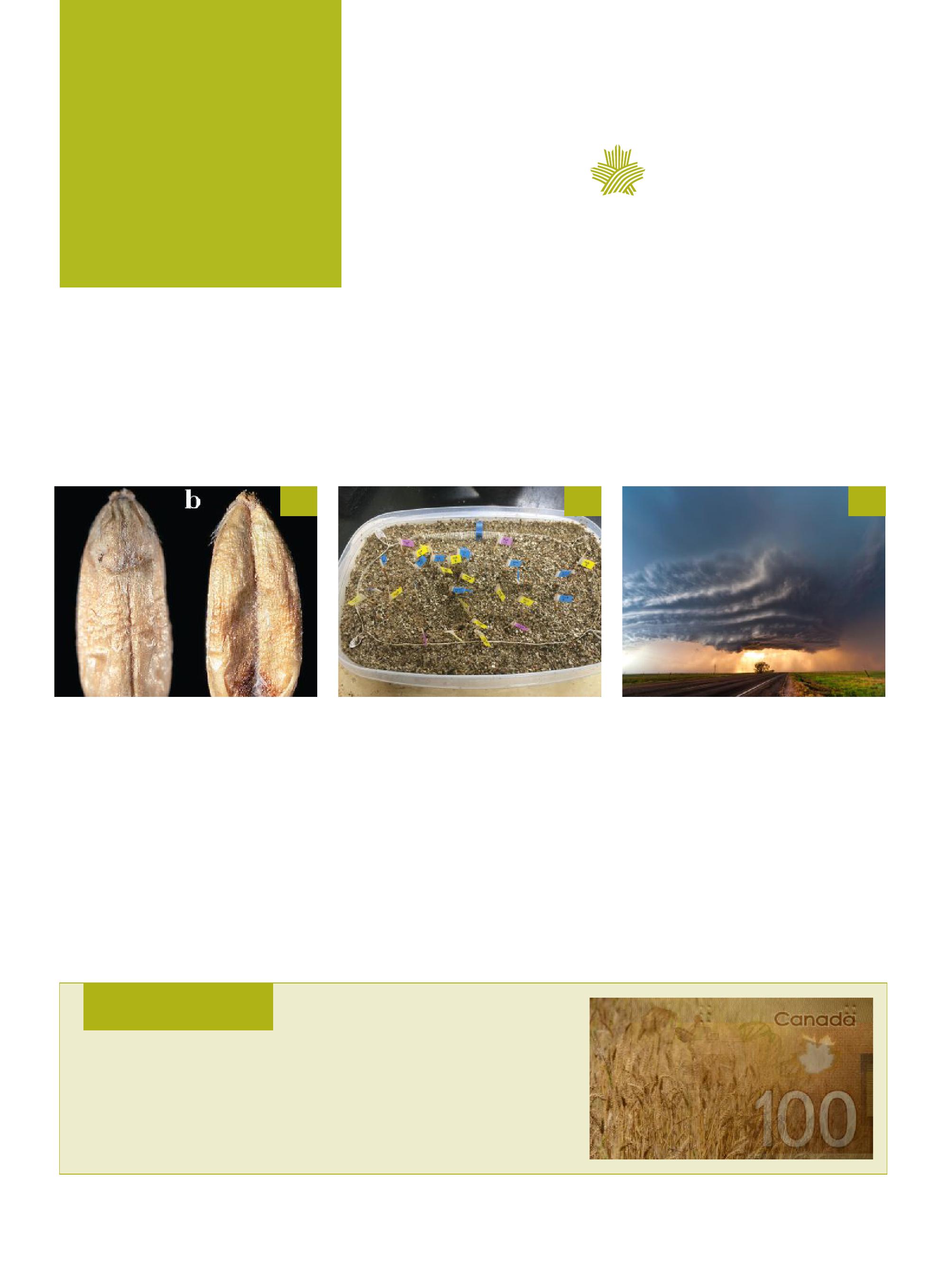

In Saskatchewan, provincial guidelines recommend spraying fungicides on durum wheat at the flag leaf stage for leaf spots and the flowering stage for Fusarium head blight (FHB), if warranted. But others are also recommending fungicide applications at earlier growth stages on a preventative basis. Yet little evidence existed, until recently, on whether this was a viable practice.

However tempting it is to throw some fungicide in with a herbicide application to save on application costs, Myriam Fernandez cautions it doesn’t help prevent disease and can even negatively impact quality.

“Our results suggest that under variable environmental conditions in Saskatchewan, not always conducive to the development of high disease levels in wheat, early preventative fungicide application on durum wheat should not be recommended as a strategy to improve productivity, even when followed by a second application,” Fernandez says.

Fernandez is a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at the Swift Current Research and Development Centre. Between 2004 and 2006, she led a study investigating single and double applications of foliar triazole fungicides at various growth stages, and the impact on FHB, deoxynivalenol (DON) concentration, dark kernel discoloration and grain traits in durum wheat. A second study was led by research scientist Bill May at AAFC’s Indian Head Research Farm between 2001 to 2003, which looked at the impact of single and double fungicide applications at flag leaf emergence and flowering stage on disease control and yield and quality of durum. Both studies were recently published in the Canadian Journal of Plant Science.

In Fernandez’s research, plots were established at the South East Research Farm in southeast Saskatchewan, and the trial ran for three years. The previous crop was canola in each year. AC Avonlea durum

was seeded using a no-till plot drill. Standard agronomic practices were used.

Folicur was applied at the recommended rate in all years. Six fungicide treatments were conducted:

• unsprayed;

• at stem elongation (GS 31);

• when flag leaf was half emerged (GS 41);

• at early to mid-anthesis (flowering) (GS 62-65);

• at stem elongation and mid-anthesis;

• at flag leaf emergence and anthesis.

Leaf spotting disease, FHB incidence, Fusarium kernel infection, DON concentration, grain yield and quality parameters were measured. Percentage leaf spotting severity on the flag leaves was evaluated in 2004 and 2005, but not in 2006 because of poor disease development.

Fernandez says that in most cases, a fungicide application at stem elongation was not effective in reducing Fusarium diseases, nor in improving yield and grain characteristics. She explains that none of the early, single applications were consistently different from the unsprayed control. Fungicide application at flag leaf emergence was more effective in reducing disease levels later in the growing season or improving grain characteristics than an early application at stem elongation. An application at the flowering stage resulted in the most consistent reduction in Fusarium levels, leaf spotting and improvement in kernel size.

This is consistent with fungicide application timing for FHB control. Saskatchewan Agriculture recommends fungicide application when at least 75 per cent of the wheat heads on the main stem are

ABOVE: Amber durum: a = sound; b = moderate symptoms of Fusarium damaged kernels (FDK); c = severe symptoms of FDK.

fully emerged to when 50 per cent of the heads on the main stem are in flower.

The double fungicide applications at either stem elongation/flag leaf emergence and anthesis were no more effective than a single fungicide application at flowering, and would have resulted in increased fungicide and application costs.

None of the fungicide treatments resulted in a significant grain yield increase. “We can conclude that fungicide application, single or double, might be profitable only in the presence of higher disease pressure levels, with more suitable growing conditions for disease development and plant growth,” Fernandez says.

Grain downgrading might result from early and frequent fungicide application

The early fungicide applications also had a negative impact on dark kernel discoloration, a key quality parameter for durum wheat with tolerances for total smudge and black point at five per cent in No. 1 Canadian Western Amber Durum (CWAD) and 10 per cent for No. 2 CWAD. The discoloration would have resulted in downgrading for the early application treatments.

Fernandez says the results also indicated potential for a consequent increase in kernel discoloration like black point and red smudge after early fungicide treatment, which was associated with greater kernel size. This effect has also been reported with other fungicides from other wheat growing regions of the world.

The 2001-2003 study conducted in southeast Saskatchewan and southwest Manitoba led by May at Indian Head looked at the impact of single and double fungicide applications at flag leaf emergence and flowering stage on Fusariumdamaged kernels and other kernel diseases, leaf spotting, and resultant grain yield

and quality of durum wheat.

Disease levels averaged over all site years were high enough to result in an 8.5 per cent yield increase from the application of fungicides. However, application at either flag leaf elongation or flowering stage also increased black point by 49 per cent, from 0.38 per cent to 0.56 per cent, and red smudge by 17 per cent, from 0.54 per cent to 0.63 per cent. In addition, double fungicide application further increased red smudge to 0.85 per cent, a 57 per cent increase compared to no fungicides being applied.

Effective August 2015, the Canadian Grain Commission changed the grading factors for CWAD. Red smudge is no longer a separate grading factor, but is still included under “smudge.” The maximum allowable level of smudge in CWAD is now 0.50 per cent for grade No. 1, and one per cent for grade No. 2 and grade No. 3. Prior to 2015, the tolerance level for red smudge in CWAD No. 1 was 0.30 per cent. In May’s research, the percentage smudge would have resulted in a downgrade to No. 2 CWAD.

May says two theories have been put forward to explain the association of red smudge and fungicides. The first is that an early fungicide treatment could result in an increase in kernel size that would facilitate the opening of the protective husk (glume), making it easier for fungi to penetrate and infect the grain. An alternative explanation is that the fungicide might alter the microbiological community on the spikes before or during kernel development, modifying the fungal interactions in that environment. More research is required under western Canadian conditions to determine the exact cause.

For foliar leaf disease control, Fernandez says the recommendation is still to apply a fungicide at the flag leaf stage, based on the level of disease infestation.

This research found little benefit to applying fungicides for leaf spot diseases because the crop was not heavily infected. In other areas more conducive to disease, or years with high disease pressure, fungicide application at the flag leaf, or heading stage for leaf spotting disease could be profitable. The research also shows that current fungicide timing recommendations for FHB control at head emergence to 50 per cent flowering are still valid.

Fernandez cautions when applying any fungicide at any growth stage the potential development of fungicide resistance in wheat pathogens should always be considered, and unnecessary fungicide application may increase the risk of resistance developing.

May says faced with the recommendation of early fungicide application as a preventative measure regardless of disease pressure, farmers need to consider that early and frequent fungicide applications to durum wheat might reduce grain quality and result in downgrading and potential profit loss.

“I would expect that a fungicide application for control of FHB in durum wheat would provide a yield increase much more often than it would improve the grade of the harvested crop.” May says.

Strip away the paint, ignore the logos and take a look inside any rotary combine. You’ll find the single rotor technology we introduced over 35 years ago. But unless it has more bells and whistles with fewer belts and chains, it’s not a Case IH Axial-Flow ® combine. You’ll get more quality grain in the tank while reducing your maintenance. And our SCR-only engine design provides more power while using less fuel. Which is why the Axial-Flow rotor is at the heart of our harvesting expertise. Learn more at caseih.com/heartbeat

by Donna Fleury

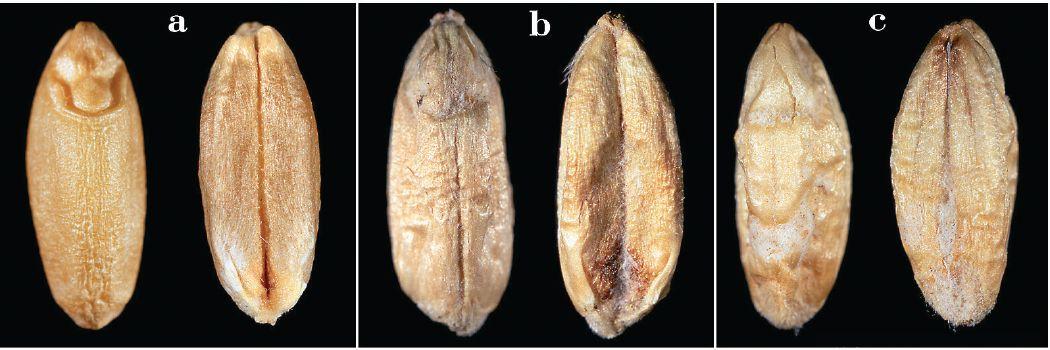

Apilot project to improve sclerotinia risk assessment in canola was launched in 2014 using a sclerotiadepot method, which was developed by Lone Buchwaldt and successfully used in Denmark for many years. Buchwaldt, now a researcher with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Saskatoon, set out to evaluate the usefulness of this method in Canada.

“We initiated this pilot project on a small scale in Saskatchewan to find out if extension specialists and growers were interested in helping with forecasting of sclerotia germination in commercial fields,” Buchwaldt explains. “Our objective was to evaluate the usefulness of this method in Western Canada in combination with the existing ‘sclerotinia stem rot checklist’ available from the Canola Council of Canada. This checklist is composed of six risk factors, one of which is the presence of apothecia.”

(An interactive version of the checklist can be found on SaskCanola’s website www.saskcanola.com; go to “Research,” select “Sclerotinia risk assessment” and select “Stem rot checklist.”)

A “depot” consists of sclerotia, inserted in small pockets made of

white nylon mesh. “Visiting a depot buried in a commercial canola field is a convenient way to check if conditions are right for sclerotia germination in the surrounding fields,” Buchwaldt explains. She emphasizes it is important to use the checklist to determine the level of risk for each individual field. It is particularly important to note previous problems with sclerotinia and how often canola and other susceptible crops have been grown, since sclerotinia can be maintained by most non-cereal crops, many weed species and volunteer canola.

Sclerotia for the project have been collected from infected canola stems in different fields in Saskatchewan and sorted by size, so only the largest ones are used. “Sclerotia in nature are subjected to variable temperatures and wetness, so the sclerotia we used in 2014 were placed in the soil outside from October to April. However, this did not give us enough time to test their viability before they were sent to our volunteers in May,” Buchwaldt notes.

This step has been changed so now sclerotia receive several

ABOVE: Test of sclerotia germination in a depot under optimal conditions in a growth chamber. Each flag marks the first appearance of apothecia from the 50 buried sclerotia.

More power to you.

Wind speed, pressure gauge, optimal nozzle settings, check. All systems are go and it’s time to take down the toughest weeds in your wheat eld, whether they’re resistant or not.

With three different modes of action in a single solution, Velocity m3 herbicide provides you with exceptional activity on over 29 different tough-to-control grassy and broadleaf weeds.

cycles of cold/wet treatments indoors, which allows enough time for a germination test in a growth chamber. “We know from the tests that the sclerotia are viable, because there was between 50 and 75 per cent germination success of the sclerotia used in 2015, as well as for those that will be used in the upcoming 2016 growing season.”

Buchwaldt says an excessive amount of rain in the spring of 2014 meant many depots were lost due to flooding, and warm dry conditions during flowering prevented sclerotia germination in other depots. In 2015, dry weather conditions leading up to and during canola flowering across much of Western Canada meant zero germination was reported, except in the Benito area (by Duck Mountain

National Park) where six to eight per cent germination was reported. “The reports from volunteers typically included comments about drought conditions resulting in poor plant stands,” Buchwaldt notes. “Therefore it isn’t surprising we didn’t see germination.”

Canola disease surveys coordinated by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture indicate the majority of canola crops have some incidence of sclerotinia every year. However, Buchwaldt stresses yield is only affected when the main stem is completely colonized by sclerotinia, causing the typical whitish lesions with new sclerotia forming inside the stem. In 2014 and 2015 there were only a few records of fields with severe stem infection.

“Nevertheless, the surveys tell us that growers need to monitor weather conditions every year and use available forecasting tools to assess whether to apply a fungicide,” Buchwaldt says. “As a rule, the threshold for economical fungicide application is 15 per cent infected stems or higher. However, fungicides have to be applied before symptoms appear and that is why risk assessment is so important.”

In 2014, a total of 67 depots were established in Saskatchewan, managed by 37 volunteers. The project expanded in 2015 to 140 depots across Western Canada, with 67, 65 and eight depots in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, respectively.

The project is gearing up for the 2016 season, with 180 sclerotia-depots available for distribution.

“The sclerotia have undergone the necessary cold/wet treatment and are viable,” Buchwaldt says. “We welcome returning and new volunteers from across Western Canada and are hoping to see a greater number from Manitoba this year.”

Volunteers will receive depots by mail in early spring. Once the canola plants have germinated, the depots can be placed between the rows in the selected canola fields. Marking the depots with a stake helps in finding them during the growing season. Also, marking each germinating sclerotia with a toothpick makes counting easier.

Volunteers are asked to monitor the

depots once per week during the vegetative growth stage and one or two times per week during flowering, particularly if apothecia are forming. Per cent sclerotia germination is submitted to a website using a cell phone or computer. Anyone interested in becoming a volunteer can email sclerotia.depot@agr.gc.ca.

During the growing season, the AAFC team in Saskatoon regularly updates the maps, making real-time sclerotia germination data available across Western Canada. The data are available until the end of flowering through SaskCanola’s website. The pilot project will finish with the growing season in 2017. Buchwaldt hopes that at that time, other people will be interested in taking over the sclerotia-depot idea.

Same superior control. New GoDRI™ formulation.

• The #1 graminicide brand used in wheat

• High performing on a wide range of weeds

• Superior wild oat control + bonus broadleaf control

• No re-cropping restrictions, wide application window

• Convenient GoDRI formulation for fast, easy mixing and handling

Go to the new dowagro.ca or call 1.800.667.3852.

review of new registrations and label updates for 2016.

by Ken Sapsford

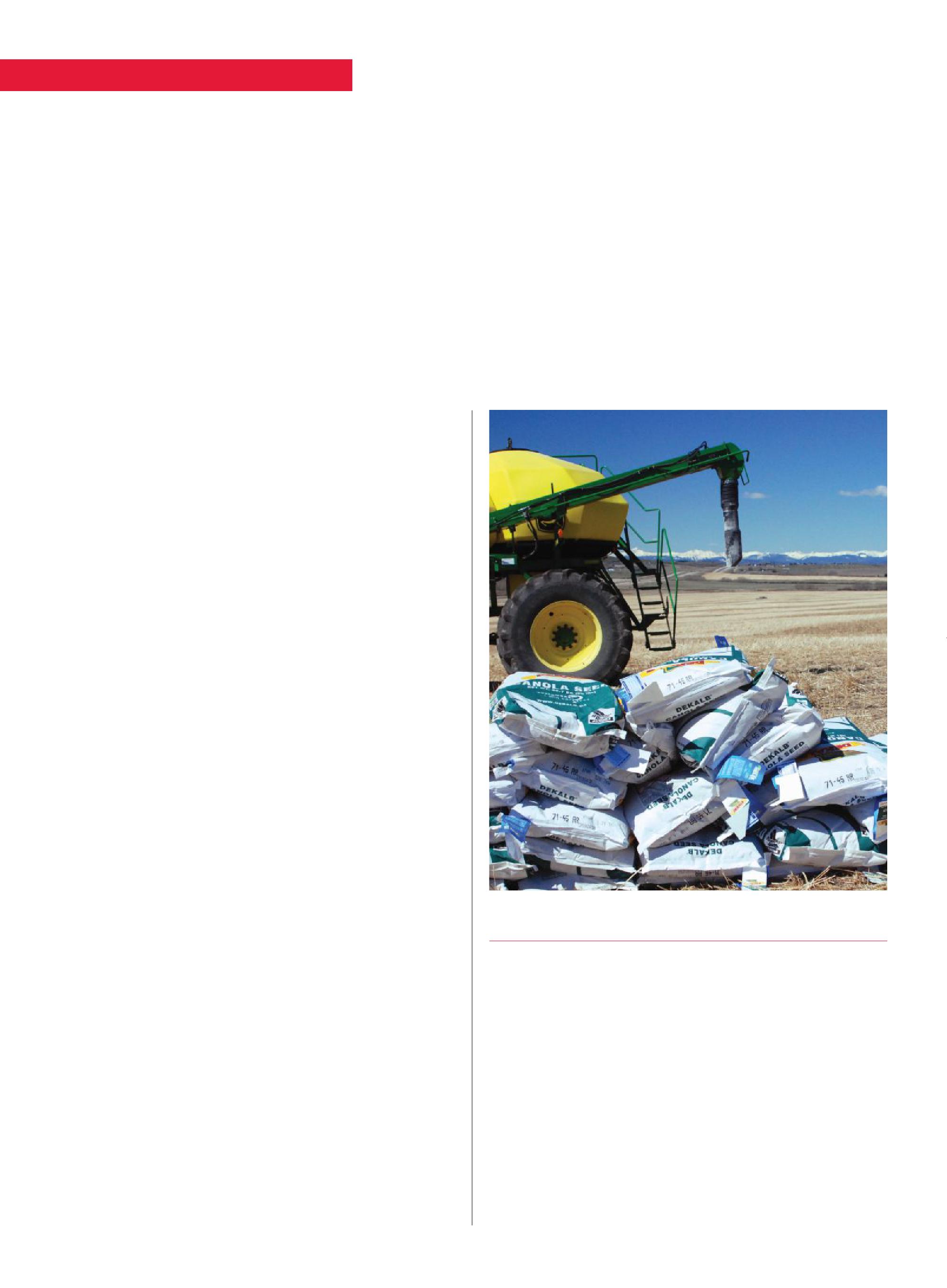

Alook at the new seed treatments, foliar fungicides, insecticides and label updates for 2016, with product information provided by the manufacturers.

Seed treatments

Apron Maxx with Intego: [fludioxonil (Group 4) metalaxyl-m (Group 12) and ethaboxam (Group 22)]. A new seed treatment copack solution for peas, lentils and chickpeas that offers control of seedand soil-borne diseases caused by Fusarium, Pythium and Rhizoctonia, along with suppression of Aphanomyces root rot and root rot caused by phytophthora

Consensus L seed treatment: [indole-3-butyric acid, salicylic acid, chitosan]. A unique pulse seed treatment designed to promote early germination and quicker root development; for use on lentils, peas and soybeans. This product may be applied by commercial seed treaters as a water-based slurry through standard slurry or mist-type commercial seed treatment equipment.

Deflect: [tebuconazole (Group 3) and metalaxyl (Group 4)]. A multiple mode of action fungicide. It controls certain seed-, seedlingand soil-borne diseases of wheat, barley and oats, including loose smut, seedling blight caused by seed-borne Fusarium spp. and damping-off caused by Pythium spp.

Insure Pulse: [metalaxyl (Group 4), xemium (Group 7) and pyraclostrobin (Group 11)]. For multiple mode of action, broad spectrum control of key seed- and soil-borne diseases. With the active ingredient xemium and its unique mobility characteristics, Insure Pulse is the first truly systemic pulse fungicide seed treatment to be offered to western Canadian pulse and flax growers. Insure Pulse also offers AgCelence benefits for more consistent and increased germination and emergence, including under cold conditions, enhanced seedling vigour above and below ground, and an enhanced ability to manage exposure to environmental stresses. Insure Pulse is available in a ready to use formulation.

Rancona Pinnacle: [ipconazole (Group 3) and metalaxyl (Group 4)]. A new seed treatment that combines two different modes of action for contact and systemic activity for broad spectrum disease control in wheat, barley, oat, rye and triticale. This unique combination of ipconazole and metalaxyl fungicides control both seed- and soil-borne diseases such as Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Pythium, Cochliobolus, smuts, and bunts, improving stand establishment while protecting the yield potential of the crop.

Sombrero: [imidacloprid (Group 4)]. A highly effective seed

ABOVE: New seed treatments are providing more options for seedling disease control.

treatment insecticide providing broad spectrum control of above and below ground pests. As the plant grows, systemic action transports Sombrero throughout the developing stem and leaves, ensuring lasting insect control, giving the crop the defense to grow to its potential. Registered for on-farm use in wheat (spring, winter and durum), barley, oats and soybeans, and by commercial treaters in canola, mustard and corn.

Elatus: [azoxystrobin (Group 11) and aenzovindiflupyr - trade name Solatenol - (Group 7)]. A new dual mode of action fungicide for use on pulse crops, including chickpeas, field peas and lentils. Elatus provides excellent preventative activity on major pulse diseases, such as ascochyta blight, anthracnose and mycosphaerella blight. Elatus offers one

convenient, targeted rate across all pulse crops, with one case treating up to 40 acres by ground or aerial application.

Evito: [fluoxastrobin (Group 11)]. A new foliar fungicide applied to wheat, barley, potato, corn and soybean. Evito is a systemic, strobilurin fungicide that enters the plant quickly providing reliable disease protection against major leaf diseases. Evito, combined with its excellent disease control, low use rate and concentrated formulation, provides the grower with an efficient and effective fungicide for foliar application.

Exempla: [difenoconazole (Group 3) and azoxystrobin (Group 11)]. A new dual mode of action fungicide for use on canola. Exempla provides preventative and curative activity on sclerotinia stem rot, alternaria black spot and blackleg. Exempla is available in a convenient, pre-mix formulation and features a single use rate for sclerotinia, along with flexible application timing from 20 to 50 per cent flowering.

Lance AG: [boscalid (Group 7) with pyraclostrobin (Group 11)]. Delivers enhanced performance including control of sclerotinia and other late season diseases in canola, pulses and alfalfa for seed production. Research shows Lance AG also delivers the unique AgCelence benefits, including enhancing the plant’s ability to better manage minor stress during the critical flowering period, often resulting in reduced flower blasting, increased photosynthesis and increased yield potential.

Orondis Ultra: [mandipropamid (Group 40) and oxathiapiprolin (Group U15)]. A new fungicide that provides an unprecedented 21 days of preventative, residual late blight (Phytophthora infestans) control in potatoes. Orondis Ultra features the new active ingredient, oxathiapiprolin, which penetrates the leaf surface and moves within the plant to protect existing and new growth. In addition to potatoes, Orondis Ultra can be used on

various vegetable crops to control oomycete diseases.

Quash: [metconazole (Group 3)]. A flexible fungicide for use on canola, chickpea, dry bean, field pea, lentil, potato and sunflower. It provides effective overall plant protection by quickly moving through the cuticle of the plant and by providing residual activity. It delivers protection from sclerotinia in canola, as well as several diseases in pulse crops. Quash is now registered for excellent control of sclerotinia in canola over a full rate range from 56 to 85 g/ac, giving growers and agronomists the opportunity to tailor their level of application to the level of risk in their fields.

Topnotch: [azoxystrobin (Group 11) and propiconazole (Group 3)]. A new xylem mobile fungicide that provides preventative and curative protection from a broad spectrum of diseases, including rusts, tan spot, septoria, scald and net blotch. Registered for use in wheat, barley, oats, rye and triticale. Topnotch is tank-mixable with numerous herbicides and insecticides.

Prosaro 250 EC: [prothioconazole (Group 3) and tebuconazole (Group 3)]. Now registered for use on oat to control crown rust, stem rust, stagonospora leaf blotch and black stem.

Voliam Xpress [lambda-cyhalothrin (Group 3) and chlorantraniliprole (Group 28)]. An insecticide for use on canola, Voliam Xpress delivers fast knock down of pests followed by residual control in order to control pests at varying lifecycles. Voliam Xpress can be applied by ground or air when insect pests begin to build, but before they reach economically damaging levels.

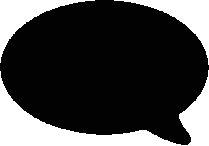

TeeJet tips: precise herbicide application to wipe out weeds & boost yields.

Believe it or not, there’s a simple trick to protecting your canola yield before sclerotinia even becomes a problem – and you don’t have to be a magician.

Based 100% in science, easy-to-use Proline® fungicide proactively protects your pro ts and continues to be the number one choice for canola growers looking for effective sclerotinia protection.

For more information, visit cropscience.bayer.ca/Proline

Results show no consistent boron response.

by Bruce Barker

The Ultimate Canola Challenge (UCC) 3.0 ran in 2015 to further assess the effects of boron fertilizer on canola yield across the Prairies. Despite approximately 20 to 25 per cent of canola growers using boron (B) in their fertility program in canola, Murray Hartman, provincial oilseed specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry (AAF) at Lacombe says UCC and other research trials do not find a case for routinely applying boron on the Prairies.

“Going back to 2013 with the Ultimate Canola Challenge, there were some inconsistent results with boron, so instead of carrying on the challenge with all the treatments, we decided to focus on boron in 2015,” Hartman says. He reported on the UCC findings at the Alberta Agronomy Update in Red Deer, Alta., in January 2015.

The original UCC conducted by the Canola Council of Canada (CCC) ran in 2013 and 2014 and compared 12 different treatments against a best management practice (BMP) approach developed by Hartman and Neil Harker, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), both at Lacombe, Alta. The products tested in those years were picked by Hartman, Harker and CCC agronomists, based on the number of inquiries they received about the products and their own personal interest, and included extra nitrogen (N) fertilizer at seeding or in-crop, seed primers, biostimulant, boron, foliar stress relievers and CO2 fertilizer.

The UCC research in 2013-14 was conducted successfully at nine sites in Alberta and three sites in Saskatchewan; there were a few sites that were rejected due to weather or other issues.

The results from the original UCC found that of 13 products and practices tested, only one provided a significant response compared to the BMP check. Applying N at 75 per cent of the recommended rate resulted in a significantly lower yield.

Hartman says given the lack of response to the treatments in the original UCC, the team didn’t feel it was worthwhile to carry the same trials forward in 2015. Rather, because significant acres continue to be treated with boron, they decided to focus the UCC in 2015 on boron in both small plots and farmer field trials.

Small plot trials were conducted at AAFC Beaverlodge and Lacombe (trial lost to hail), Alta., Portage la Prairie, Man. and Scott, Sask. Large field strip trials were conducted at Innisfail and Penhold, Alta., Medstead, Nipawin and Fairlight, Sask., and Rapid City, Man. Treatments for small plots included no boron check, Boron (Nexus) at five per cent flowering at 1 L/ac, MicroBolt B (Alpine) at the four to six leaf stage at 0.75 L/ac, SuperB (Omex) at five per cent flowering at a rate of 1.0 L/ac, and Boron (Nexus) with fungicide at 30 per cent bloom at 1.0 L/ac. Large plots compared the producer’s choice of foliar boron to a check, except for the Medstead site, which involved a soil-applied boron treatment. Large field strip replications ranged from one to five.

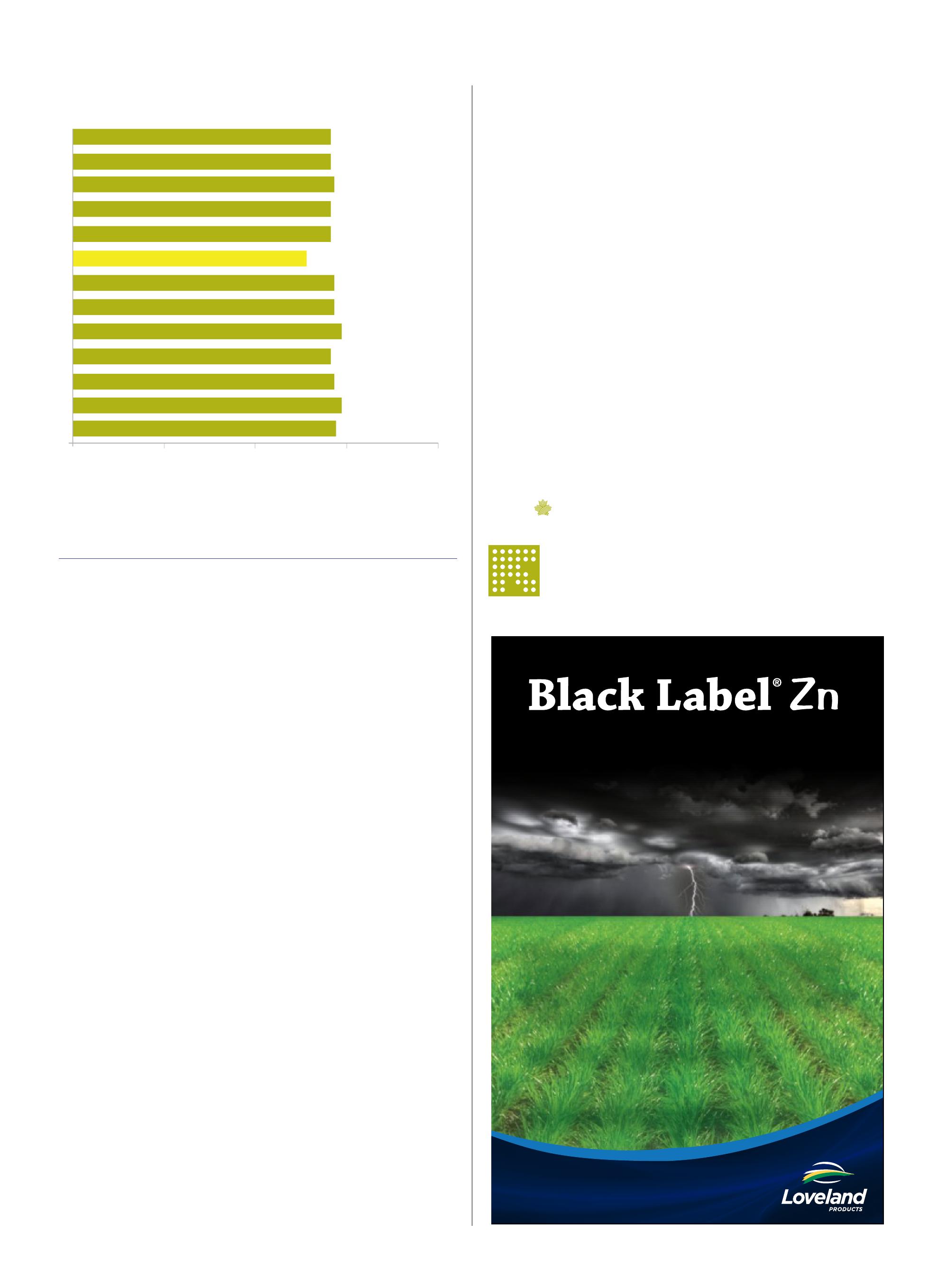

“In the 2015 small plots, we found no statistical yield difference from the check treatment at any site or overall,” Hartman notes.

ABOVE: Boron response in canola “unlikely.”

Note: Yellow bar denotes statistically significant difference from BMP.

Source: Murray Hartman, AAF.

Similarly, in the large strip trials, overall there was no statistically significant difference. There was a slight trend towards higher yield at Rapid City (although not statistically different), but a significantly higher yield with boron at Nipawin where the crop was recovering from hail damage. The Nipawin site only had two replications and no measurements to confirm similar crop densities after the hail, and thus the results shouldn’t be viewed as conclusive.

“Overall in the three years of the Ultimate Canola Challenge, in small plots we saw two questionable statistical yield increases out of 20 and one statistical yield loss with boron. In large strip trials, we saw one statistical yield response and one strong trend out of five,” Hartman says. “That’s getting us close to convinced that boron is generally not a benefit.”

Hartman went one step further and looked at other independent research conducted on the Prairies. He did a meta-analysis of these research projects and the UCC results to find out if there was a common conclusion regarding the benefits of using boron in canola. The trials included those conducted by fertility researchers Rigas Karamanos, Sukhdev Malhi, Fran Walley and Stephen Vajdik, and other trials from the CCC, AAF and the Battle River Research Group. The foliar and soil applied treatments were compared separately to the check when both were tested in one trial, so there were more comparisons than actual site years.

The analysis found that out of almost 100 comparisons from more than 60 site years, about one-half gave an arithmetic yield increase, while the other one-half had a yield loss. This illustrates a normal distribution with no significant treatment effect.

“On average, over all these comparisons, there wasn’t even a one per cent yield increase from boron,” Hartman says. “Based on all the research, as a general recommendation I would have to say it is a ‘big unlikely’ that you would get a statistical yield response. We didn’t even see a statistical response in 25 per cent of

the trials, which I personally use to define an unlikely response. Statistically, there just was not a real, general response to boron.”

Hartman also looked at whether other factors like heat or hail might be a predictor of boron response. Overall, he couldn’t tease out the effect of hail on boron response due to inconsistency in very few trials. Hartman also looked at the number of July days with temperatures above 27 C at each trial site year, and found that it did not predict a boron response, either.

The argument could be made that perhaps there would be a more consistent response on soils typically thought to be most boron deficient – on sandy, acidic soils. However, Hartman says soil testing to determine boron fertility isn’t reliable. Published research by Karamanos et al showed poor correlation between the hot water extractable boron test and canola yield. Karamanos’ Canadian Journal of Plant Science article concluded “hot-water extractable B is not an effective diagnostic tool for determining the B status of western Canadian prairie soils.”

Overall, Hartman says the UCC trials did not support the routine use of boron in canola in Western Canada.

“I don’t really have anything else to say. This is what we found, and a response to boron is very unlikely for me,” Hartman concludes.

Weathering the storm of very variable weather on the Prairies.

by Carolyn King

In recent decades, Prairie producers have taken steps – such as using minimum tillage, improving water supplies for livestock, and storing extra feed – that enable them to survive short droughts. But the Prairie climate in the coming decades could include droughts that last five, 10 or more years, as well as extreme swings between really wet and really dry conditions. So Prairie people are starting to come together to plan and prepare for whatever the future might hold.

Many people on the Prairies have experienced dramatic shifts between extremely dry and extremely wet periods in the last few years. “For instance, from April to June in 2015, Regina had 43 millimetres of rain. Normally it would see about 147. Looking at the records that go back to the 1880s, it turns out to be the third driest such period in 120 years. But the previous April to June was the wettest on record for Regina. That is the kind of weather whiplash that farmers are dealing with. The weather has a Jekyll and Hyde personality,” David Phillips, senior climatologist with Environment Canada, says.

He adds, “Farmers build into their strategies dealing with things like too wet to seed and too dry to grow – those things happen when you’re in farming. But when you get back-to-back weather conditions you would expect to see only once in a career of 40 or 50 years of farming, how can you deal with that?”

University of Manitoba atmospheric scientist John Hanesiak and his colleagues have described other examples of such backand-forth weather extremes on the Prairies in a recent paper. Looking at the period from 2009 to 2011, they found that precipitation ranged “between record drought and unprecedented flooding.” In some instances, drought and very heavy rains occurred at the same time in different parts of the Prairies. And some locations experienced both weather extremes within those three years; for example, some southern Manitoba farmers had insurance claims for both flooding and drought in the 2009 growing season.

ABOVE: The Prairie weather can have a “Jekyll and Hyde personality.”

In addition to providing an exceptional yield increase, Prosaro® fungicide protects the high quality of your cereals and helps ensure a better grade.

With two powerful actives, Prosaro provides long-lasting preventative and curative activity, resulting in superior protection against fusarium head blight, effective DON reduction and unmatched leaf disease control.

With Prosaro you’ll never have to settle for second best again.

This type of wild variability is predicted to be part of the future climate. “We are expecting to see greater variability from year to year, going from droughts to really wet periods. Even the older climate models were telling us 10 or 15 years ago to expect that kind of a pattern,” Hanesiak says.

The current variability in the Prairie weather may be one indication that the predicted patterns in the atmosphere are starting to become a reality. “Recently some articles have suggested that we’re on the verge of seeing these things happening now, where the wave in the jet stream tends to meander a little more. That potentially could create a more stagnant pattern, where you get longer periods of drought and longer periods of wet, depending on where you are on that wave,” Hanesiak explains.

Studies of past climate patterns show that such weather extremes are not new to the Prairies. Research by Dave Sauchyn of the University of Regina has found that multi-year and multi-decade Prairie droughts have occurred during the past 1000 years.

“We tend to get caught off-guard [by extreme weather] and we use the excuse that ‘we couldn’t have anticipated it because it has never happened before.’ We’re implying that it has never happened in our lifetime because we all think in terms of our own situation,” Sauchyn says. “But if you get outside your own local experience and look at the longer records, you find that it has happened over and over again.”

Sauchyn has been sharing the results of his climate research with Prairie people who need the information, and he has been learning from them about their drought adaptation strategies. For example, in October 2015, Sauchyn and his research group met in

southwestern Saskatchewan with local people including farmers, ranchers and government officials.

“They told us that much of what they have already done over the decades, and especially the last few decades, is putting them in good shape because, in general, agricultural practices are more sustainable than they were in the past. That is reflected in less soil erosion and more resilient agricultural ecosystems. In general, if you maintain a healthy and resilient agro-ecosystem and take proper care of pastures, crops, soil and water, then agriculture will be less vulnerable to the impacts of climate change,” he says.

“But they also told us that individual farmers and ranchers can only do so much, especially if drought exceeds more than one or two years. They can store water for a couple of years. There is an extensive water storage and diversion infrastructure on the Prairies, especially in the drier parts, and it has been very effective in withstanding one- or two-year droughts. Beyond that, there is only so much water that can be stored. Similarly, feed can be stored for one or two years. But they tell us that after a couple of years of drought, the local options are pretty much exhausted.”

At that stage, people turn to their social capital. Sauchyn explains, “We’re all familiar with concepts like ‘fiscal capital,’ money, and ‘natural capital,’ ecosystem goods; there is also ‘social capital,’ maintaining good relations among neighbours. Especially when people are faced with climate extremes like flooding and drought, they rely very much on that social capital.”

He notes, “One of the most effective ways to adapt to a changing climate is to work collectively, with your neighbours within your watershed. Local organizations such as watershed stewardship groups are especially effective.”

A NEW WORLD DEMANDS NEW HOLLAND.

One example of a Prairie watershed agency working to prepare for climate variability is the Battle River Watershed Alliance (BRWA). The Battle River has its origins in east-central Alberta and flows into Saskatchewan where it joins the North Saskatchewan River. The BRWA is an Alberta group created in 2006 and it operates in the Alberta portion of the Battle River and Sounding Creek watersheds. The BRWA describes itself as “an inclusive, collaborative and consensus-based community partnership that is working to guide, support and deliver actions to sustain or improve the health of the Battle River watershed.”

BRWA research and stewardship coordinator Susanna Bruneau outlines how the Alliance is approaching climate variability. “At conferences, they talk about preparing for extremes, where you could get really wet events, like the flood in Calgary a couple of years ago, or a multi-year drought. We’ve been trying to work on things that can help in managing both those extremes, especially natural infrastructure like wetlands and riparian areas and even shelterbelts.” Those types of features can have benefits like reducing flood peaks, capturing water in case of drought, and protecting water quality.

She notes, “Another part of how we approach things is trying to have our systems – whether it’s our social support systems, agriculture systems or water infrastructure systems – made in a way that can be adaptive to whatever comes our way.” She explains that the BRWA recognizes the complexity and uncertainty in these systems so it works to continually learn from experience and adjust its plans and actions to more effectively deal with emerging realities. If the BRWA finds that an approach is not working, then it evaluates the approach, asks stakeholders what should be done differently, and modifies the approach to make it work better.

In a watershed-wide consultation process, local people identified drought planning as a top priority for the BRWA. So it developed drought guidelines and policies, which were released in 2012. These documents provide a framework to help agencies in the watershed when developing drought plans for their own area of responsibility. The guidelines relate to agriculture, social issues, natural areas, and water quantity and quality, and consider the social, economic and ecological impacts of drought.

“Beside each guideline is a column indicating who should and

Sauchyn and his research group meet with local Prairie producers to talk about drought trends and drought adaptation.

can act on that guideline. It may include anyone from landowners and producers to municipalities, to provincial or federal government agencies, to conservation groups, to private companies, as applicable. We give something for everybody to do. That’s because everybody is responsible, and everybody has a role to play in helping to make our watershed a drought-resistant or resilient place,” Bruneau explains.

She adds, “Drought affects everybody. Producers might be some of the first ones affected, but drought can have trickledown effects to everybody in the community and the broader economy.”

The BRWA’s drought guidelines cover both “drought adaptation,” preparation for future droughts, and “drought management,” responses during a drought. A few examples of the drought adaptation options for agriculture include: actions that research agencies could take, such as developing drought-tolerant crop varieties; actions that governments could take, such as monitoring water supplies, developing drought plans and policies and modifying crop insurance programs; and actions that producers could take, such as choosing crops adapted to drier conditions, developing drought farm plans, managing grazing rates, conserving wetlands and riparian areas and diversifying farm income. The drought management guidelines for agriculture include actions like implementing drought plans, and sharing drought monitoring information.

Although people in the Battle River watershed are aware of the need for drought planning and preparedness, it is a challenge for local agencies to direct their limited human and financial resources towards this task. Bruneau doesn’t know of any agencies in the watershed that are currently using the BRWA’s guidelines to develop their own drought plans, but she’s hoping that will change.

“Drought is part of the climate cycles here on the Prairies. Drought is going to happen, no matter what happens with climate change. There is a lot we can do to mitigate the impacts of drought if we plan and adapt before a drought happens,” Bruneau says.

“Drought is not like a flood or an earthquake; it’s not a sudden crisis where you have to deal with things in the heat of the moment. Drought is sly and it sneaks up on you. Unless you are paying attention you’ll get caught. But we have opportunities to prepare for drought, and when we see drought coming or just less than normal precipitation, there are things we can do.”

She adds, “Changing how we think about ourselves in relation to drought is an important part of dealing with drought. Rather than thinking about ourselves as victims of drought, we can think about drought as something that we can prepare for and that we have to change our actions in the light of drought.”

For more on environmental issues, visit topcropmanager.com.

Reach for Wolf Trax Copper DDP ®, the nutrient tool that is field-proven by wheat growers like you.

With our patented EvenCoat™ Technology, Copper DDP coats onto your N-P-K fertilizer blend, delivering blanket-like distribution across the field for easier root access. Plus our innovative PlantActiv™ Formulation ensures the copper is available when your wheat crop needs it most.

See how the right tool can boost your wheat crop and your bottom line. Have your dealer customize your fertilizer blend with Wolf Trax Copper DDP.

Copyright © 2016, All Rights Reserved - Compass Minerals Manitoba Inc. Wolf Trax and Design, DDP, EvenCoat and PlantActiv are trademarks of Compass Minerals Manitoba Inc.

Compass Minerals is the proud supplier of Wolf Trax Innovative Nutrients. Not all products are registered in all areas. Contact wolftrax@compassminerals.com for more information.

Product depicted is Wolf Trax Iron DDP coated onto urea fertilizer. Other DDP Nutrients may not appear exactly as shown.

46833-5 TCMW

into soil management effects and sustainability.

by Bruce Barker

In this era of focusing on short-term results, a long-term viewpoint is indeed, unique. But the long-term crop rotation study established in 1951 at Lethbridge, Alta. is a model for the long view, especially in biological systems where changes can take decades.

“We still maintain the long-term plots. We need to reapply for funding every three to five years for these studies, to purchase seed, fertilizer and pesticides,” Elwin Smith says. Smith is a bioeconomist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Lethbridge Research Centre.

Smith, along with colleagues Henry Janzen and Francis Larney, established a six-year bioassay study in 1995 that was imposed on the long-term Lethbridge plots to look at the impact of long-term rotations on soil quality, productivity, nitrogen (N) fertilizer effects on wheat yield and quality, and whether N fertilizer can overcome poor long-term rotations. The results were analyzed and published in the Canadian Journal of Plant Science in 2015.

The soil was an Orthic Dark Brown Chernozem clay loam with level and uniform topography, and calcareous subsoil. Seven rotations were established, reflecting crop rotations that were common in 1951. In 1985, several changes to the plots and rotations were made to add alternate crops being grown at the time and an additional N management component to maintain crop productivity. Thirteen rotations were included in the study from 1985 through 1994 (see Table 1).

From 1995 to 2000, all 116 plots were no-till seeded to spring wheat cultivar Katepwa. A preseed burnoff of glyphosate was applied to control weeds. In-crop weeds were controlled with appropriate herbicides. Phosphorus (P) fertilizer was applied with the seed to all plots as 0-45-0, at an average rate of 7.9

The rotation plots for each replicate were divided into two randomly assigned strips, one with zero N fertilizer (control) and one strip with N fertilizer applied at an average rate of 56 kg N/ha (49 lb N/ac).

The first two years of yield data were excluded from the bioassay analysis of total wheat yield because of confounding short-term effects of land use the year prior to the study.

Smith says the 1995 soil analysis indicated crop rotations with less frequent fallow and with N input had higher soil quality, as indicated by soil organic carbon (SOC) and light fraction carbon (LF-C) and N (LF-N). Organic matter was higher in long-term plots that had N added to the system or with lower fallow frequency. The higher organic matter also contributed to improved wheat yield. (See Fig. 1.)

“The presence of frequent fallow in crop rotations had a negative effect on total wheat yield, long-term productivity and grain N concentration, even with past and current application of N fertilizer,” Smith reports.

Treatments fertilized with N had a four-year total wheat yield approximately 30 per cent higher than unfertilized treatments. Without the application of N, total wheat yield was highest in the FWWHHH rotation, followed by plots that previously had native grass, and continuous wheat with previously added N. Smith says plots without N and high fallow frequency (FW, FWW) resulted in lower total yield regardless of N added in his study.

In Smith’s study, N fertilizer was unable to compensate for the lower productivity of fallow-based rotations that did not replenish N removed by the crop, or for rotations that were in fallow one-half of the time and had added N.

“The yield differences from this study demonstrated that previous N fertility management and crop rotation impacted current crop yield. Management practices that replenished N to the system had higher current yield, while rotations with fallow reduced current yield. The current application of N fertilizer could not overcome the yield disadvantage from previous systems with frequent fallow and no N fertilizer,” Smith says. “Producers need to recognize the importance of crop rotation and N fertility management on both long-term and current crop productivity.”

Source: Smith et al. Can. J. Soil Sci. (2015) 95: 177-186.

The Next Generation Rocket features a large smooth louvered surface that allows for cleaner unloading and increased airflow. The Next Generation Rocket Leg Design and Laser Cut Internal Ring provide a strong structure for stability during irregular grain flows.

HOPPER BOTTOM BINS WITHOUT AERATION? IT’S NOT TOO LATE TO DRY YOUR GRAIN!

The revolutionary Retro Rocket is the only do-it-yourself rocket system that allows you to retrofit existing hopper bottom and smoothwalled bins with farm proven Grain Guard aeration.

Targeted agronomy, optimum weather and a bit of luck.

by Bruce Barker

Devin Toews of Toews Family Enterprises at MacGregor, Man., won the DuPont Pioneer Yield Challenge Contest in 2015 with a bin-busting 200.8 bushels per acre.

So what does it take to grow a 200-bushel corn crop on the Prairies? “You can do so many things when it comes to growing the crop, but there is some luck in it, too,” Toews says.

The 1.24-acre plot picked for the yield contest was measured and weighed with a weigh wagon to confirm the yield. Toews had close company, with Don Toews at Winkler recording a 193.8 bushel corn yield and Everett Boyd at Boissevain growing a 186.9 bushel crop.

Toews says typical corn yield in the MacGregor area is 120 to 130 bushels per acre, on average, although depending on the year, yields can be higher. “Last year [2014], corn yields weren’t that good, but 2015 was a pretty good year,” he says.

Recipe for success

Toews’ corn crop was grown on sunflower stubble, and Pioneer hybrid 36D97 was seeded on May 4, 2015. The hybrid contains the Herculex 1 Insect Protection gene, which provides protection against European corn borer, southwestern corn borer, black cutworm, fall armyworm, western bean cutworm, lesser corn stalk borer, southern corn stalk borer and sugarcane borer; and suppresses corn earworm. The hybrid also carries the Liberty Link and Roundup Ready 2 herbicide resistant traits.

Toews uses a strip tillage program to minimize tillage of stubble and apply fertilizer. He then seeds back into the fertilizer-banded strip till with a Case IH 1250 planter on 30 inch row spacing. The planter has a liquid system that is used to put on an Alpine liquid phosphate (P) starter fertilizer that is dribbled with the seed.

The strip-till unit he put together has both liquid and dry fertilizer, which gives him more flexibility with fertilizer blends. The liquid nitrogen (N) band is four to five inches deep and the granular

P and potassium (K) is six to seven inches deep. The strip-till unit is capable of three product variable rate. The applied fertilizer blend was approximately 130N-32P-60K-20S.

“As the plant develops it grows into the band and can use as much fertilizer as it needs,” Toews explains.

Toews has been using precision agriculture in decision-making, and uses it to assess varieties side by side. The planter has two tanks that can plant two varieties at a time.

“We see trends with varieties in wet or dry conditions. We analyze the yield maps and have chosen varieties that work best in our soils and conditions. This particular variety, 39D97, has done really well for several years,” Toews notes. “Along with variable rate striptill fertilizer we try to tune for the top potential of the crop. Another thing we find value in is on-farm trials. For the past few years we’ve been looking for things that can pay off. We want to make sure everything we do makes sense, from starter fertilizer to strip-till; it has been trials that help make those decisions.”

Toews sprays weeds as needed. Depending on the year, two to three applications of glyphosate are applied.

The crop was harvested on Nov. 9, 2015, at a moisture content of 21.5 per cent. The moisture content was factored into the yield results.

Information from Environment Canada shows the MacGregor area received 350 to 400 mm of precipitation between May 1 and Oct. 12, 2015. The area had approximately 2900 corn heat units in 2015.

“We had ideal timely rains which was about perfect for growing corn this year, other than a big snow storm on the May long weekend which set the crop back quite a bit, but it recovered better than we thought possible,” Toews says.

TOP: Toews’ customized strip-till fertilizer unit.

The use of UAVs to track airborne crop pathogens takes off.

By Carolyn King

Many crop growers know about the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, for activities like crop scouting. But UAVs are also a great tool for detecting and tracking airborne spores, bacteria and other microorganisms that cause crop disease.

The resulting information can have such practical applications as helping in on-farm disease management decisions, contributing to early warning systems for major diseases, evaluating the effectiveness of disease eradication efforts, and tracking down the sources of disease outbreaks.

“The field of aerobiology, which is the study of the flow of life in the atmosphere, has lacked appropriate tools to get after organisms that are flying high in the sky. UAVs have really become an important tool in that arena,” David Schmale, an associate professor at Virginia Tech, says.

According to Schmale, the use of UAVs in aerobiology got off the ground through the work of United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) plant pathologist Tim Gottwald back in the 1980s. Schmale notes, “Tim Gottwald stuck a little rotating spore trap underneath the wings of a biplane, along with some little insect nets that he could remotely swing open, and he started buzzing peach and pecan orchards. His work was the pioneering work to get unmanned systems to track the movement of plant pathogens and also insects in the atmosphere. So he is the godfather and the real motivation behind all that we do.”

The Schmale Laboratory has been working on the use of UAVs in aerobiology for over a decade, making important strides forward in both the technical aspects of how to conduct this type of research and in discoveries about plant pathogens and their transport tens to hundreds of metres above farm fields, across thousands of kilometres. Depending on their study objectives, they can sample the entire microbial community along the UAV’s sampling path or they can tailor the sampler to selectively collect certain species. They can sample at a single altitude or multiple altitudes to find out where and how the microbes are moving. And they can sample at different times of the day and the year to learn about the timing of pathogen transport and deposition.

A key early advance at the lab was their development of a fixedwing UAV (a UAV that looks like a little airplane) with its own onboard computer system. “Although technologies like autonomous systems are readily available today on most unmanned systems platforms, they were in their infancy about 10 years ago,” Schmale says.

“In this case, we had a small autopilot computer about the size of a cell phone that had been integrated into a UAV and allowed the

This is one of Schmale’s fixed-wing UAVs during a microbesampling mission at Virginia Tech’s Kentland Farm; the UAV is fitted with eight large Petri plates on the wings that open at altitude.

UAV to follow prescribed paths through the atmosphere at really tight altitudes. That was really an important milestone for us in terms of engineering.”

And this engineering advance enabled important discoveries about pathogen movement.

Some of those discoveries involve Fusarium pathogens. “The genus Fusarium contains some very nasty plant and animal pathogens, and many of them produce mycotoxins. We have a really good selective medium for Fusarium that we can take for a ride on one of our aircraft, and we’ve collected all sorts of different Fusarium

species,” Schmale explains.

“The first discovery was about a very important plant pathogen of wheat, barley and corn, Fusarium graminearum. We were able to show that isolates we had collected upwards of 40 to 300-odd metres above the surface of the earth were able to cause disease and produce mycotoxins.

“And one of the isolates produced a really unique toxin that we hadn’t discovered in any of our ground-based populations in Virginia. So this unique isolate was buzzing through the atmosphere over Virginia, perhaps from somewhere pretty far away, which was really exciting and had important implications for biosecurity efforts.”

These findings confirmed the long-distance spread of Fusarium graminearum spores and the potential for this type of transport to contribute to increased disease risk and to changes in Fusarium populations that could affect human health.

Surprisingly, the UAV samples from this research include many previously unknown Fusarium species. Schmale says, “One of the more striking aspects of that work is that about half of any given population that we’ve collected appears to represent new or understudied species. So, at least in terms of Fusarium, quite a bit remains to be discovered in the air. Many of these potentially new species could also be important pathogens that just haven’t yet been studied or uncovered in some agricultural system.”

A big part of the lab’s current work relates to the use of UAV sampling data to understand atmospheric dynamics and to help predict the regional-scale movement of airborne crop pathogens. One of Schmale’s engineering colleagues at Virginia Tech, Shane Ross, is modelling atmospheric features called Lagrangian coherent structures, or LCSs, which are like waves in the atmosphere. Schmale and Ross came up with the idea of using Fusarium sampling to track what the LCSs are doing as a way to confirm the modelling work. He notes, “We were the first to show that LCSs shuffle along Fusarium populations and modulate their movement over long distances in the atmosphere.”

The Schmale Lab is also studying the trajectories of airborne pathogens, seeking to identify their sources and destinations. As part of this, the researchers are doing release-recapture experiments, where they release identifiable spores in a field and find out where those spores land to determine pathogen movement patterns.

A new Canadian project will soon be using UAV sampling to monitor for fungicide resistance in Botrytis, an onion pathogen, in southern Quebec.

“We want to monitor if resistance is building up in the pathogen’s population in the region. We’ll use this information to provide the growers with information about which types of fungicide are no longer efficacious,” Bernard Panneton, who is leading the project, says. He is a research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s SaintJean-sur-Richelieu Research and Development Centre, a horticultural research facility that specializes in field vegetable crops.

“In our research centre, there is a huge expertise in using ground-based samplers to monitor diseases in horticultural fields. During the last three years we had a project using ground samplers, placed about one metre above the ground and on towers up to 10 metres high, to monitor how spores from fungal diseases are emitted from a field and dispersed over the area and eventually go higher in the air and move away. We found that even at 10 metres above the ground, we can collect quite large samples if you do the sampling at the right time and in the right way,” he says.

To monitor for fungicide resistance, the researchers need information on what is happening at a regional level, so they want samples from higher than 10 metres. “With spore sampling, the higher up you are, the further back you see – the spores come from a longer distance,” Panneton notes. Plus they will need to sample large volumes of air. “When you are at some distance above the ground, above 40 or 50 metres, the density of spores is pretty low. So you have to sample for a long time with an efficient sampler to collect some spores on your sampler.”

UAV sampling can meet these needs – a UAV sampler can sample a much larger volume of air than a ground-based sampler, and it can sample the air at specific altitudes high above the ground.

Panneton’s research team will be using an octocopter, a little helicopter-like UAV with eight rotors. It has a small onboard computer with GPS, so the researchers can upload its flight path. “This technology is getting fairly cheap, and it is a bit easier to use than a fixed-wing UAV. With the fixed-wing type, you need a place to take off and land. With the octocopter, you don’t need a landing strip. And the electric motors are fairly easy to service.”

The project’s first step will be to develop the necessary technologies to conduct the Botrytis sampling. For example, the little octocopter is limited in terms of how much weight it can carry, so the researchers will have to develop a lightweight sensor.

They’ll also need to develop a way to plan the UAV’s flight paths

Go ahead. Paint a target on persistent wild oats and get rid of them for good with Axial herbicide. It targets the toughest grass weeds in your fields, especially wild oats, and eliminates them before they become a problem. When you’re on a mission to help your spring wheat and barley reach its full potential, choose Axial herbicide.

to collect samples that will be representative of the region. Panneton says, “We will use a map showing where the onion fields are in the region plus forecasts of meteorological conditions to see where the wind is coming from. From this information, we will have to find a way to design a proper flight path so we increase the probability of collecting spores. We are hoping to detect fungicide resistance when the resistant proportion of the population is fairly low, about 10 per cent of the population. So we will need a fair amount of the spores to do that.”

Panneton plans to conduct the sampling in August when spore emission from the onion fields is at a maximum. “We think we can achieve a good sampling program with perhaps two flights at two different dates.”

The sky’s the limit

Looking ahead, Schmale and Panneton see intriguing possibilities for UAV sampling.

Panneton is excited by the ability of UAVs to work at different

altitudes and scales. “I think there is a future for a multi-scale approach where first you look at a larger region to get an understanding of the overall pathogen situation. If you see that something is happening and it seems to be coming from a particular area, then you can fly right there and take a point sample to confirm your hypothesis. And this approach can also work for weed [pollen], insect pests and other things we can find in the air.”

On-the-go pathogen reporting is another potentially important possibility. The Schmale Laboratory has been experimenting with a portable biosensor to do this. “We were interested in being able to collect and analyze a sample in the atmosphere while the drone was flying and to communicate that analysis down to a ground control station, which is essentially a computer on the ground that is talking with the aircraft while it’s flying,” Schmale notes.

Unfortunately, the sensor they’re using costs about $30,000 so it’s not a practical option for most agricultural uses at present. “However, those sensor technologies will continue to decrease

in size and hopefully cost,” he says. “For the future, it opens up many exciting applications like being able to do source tracking while you’re in the air, so essentially sniffing out the plume of an agent, and continuing to follow the concentration gradient until you find the source of that agent.”

Another potential application of UAV sampling is for on-farm disease monitoring. Schmale says, “Imagine you’re a potato grower with thousands of acres of potatoes and you are really worried about a particular pathogen that might be blowing into your potato fields from somewhere else. UAV sampling can do something that a ground sampler can’t do – it can sample a very, very large volume of air. So you can essentially sniff over your entire farm, collect a very large volume of air and determine whether or not a disease agent is there.”

At the Schmale Laboratory, the latest UAV research ventures are heading in a new direction: bioprecipitation. “Some of our recently funded work is focused on a rather narrow group of microorganisms [called microbial ice nucleators]. Some of these

microbes reside in clouds, while others live on leaf surfaces and in the soil and become airborne. They express interesting proteins that allow water to freeze at higher temperatures and have been associated with global precipitation events,” Schmale explains.

“The idea that a microorganism can be determining whether or not it is going to rain, hail or snow is pretty exciting.” His research on these microbes could eventually lead to improved precipitation predictions, and perhaps even contribute to approaches to weather modification. For instance, some researchers are proposing the idea of planting crops that are hosts to these microbes as a way to increase precipitation in arid areas. “Potentially we could do things on our land surface to change the weather, which is an interesting concept and likely to be very important in the coming decades.”

For more on crop pest monitoring, visit topcropmanager.com.

Remote sensing and imagery guide to satellites and UAVs/drones.

by Dale Steele, P.Ag., Precision Agronomist

Henry Ford once said, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

Imagine the vision Henry Ford had for the automobile industry as he built the factories and components in 1908 that would become the vehicle assembly platform for the 20 th century. Early automobiles were indeed “found on road dead” as the punchline of an old joke goes, and farmers would have been a segment of society that wanted to keep their horses. But the assembly line brought together the components and processes to create the future vehicles that people didn’t know they wanted.

At the time, few people understood how to build an assembly line for automobiles. Today, few people understand the technical components of precision agriculture. Some people view precision agriculture as driving straighter with bigger or faster equipment, while others envision farms with driverless tractors and swarms of robots tending each plant.

Agriculture is undergoing a period of technology convergence, and precision agriculture is the virtual assembly line of new tools and processes to enable more efficient operations and measurable results. Initially there were distinct segments, each providing services to agriculture such as manufacturing (equipment, seed, fertilizer, herbicide/fungicide), crop input retail, record keeping, grain merchants and consulting services. In the early days of tractors, there were hundreds of small manufacturers that consolidated into the dominant brands.

The ongoing growth and mergers of companies has resulted in farm service providers that participate in numerous segments to provide a bundle of interrelated services beyond their core businesses. Competition is a wonderful motivator that is currently directing billions of dollars into agriculture, and specifically precision agriculture, to disrupt the status quo. New alliances

ABOVE: You can now stand in any field on the planet and hold a tremendous amount of site-specific field data in your hands.

and partnerships are forming as companies strive to share development costs and secure channel access to reach farmers. Now there are over 100 companies offering precision agriculture services, ranging from tech startups to Fortune 500 companies, all striving to create the virtual assembly line for precision agriculture.

The platforms produced from this convergence are the apps, websites and cloud storage facilities that can utilize all the information and data collected by any sensor, device or equipment. Our imagination leaps to futuristic tools of The Jetsons or Star Trek, depending on your generation, but today’s technology is confusing because technology adoption takes time.

Progress tends to be a series of challenges that are overcome by a series of small innovations and new ideas. Equipment sensors can collect “as applied” and yield data, and alert the operator to hundreds of possible equipment fault codes. There are about 1100 active satellites orbiting the Earth and the remote sensing satellites gather massive amounts of data that is valuable for agriculture. Improved cellular and Internet services have enabled data to be sent to powerful cloud computer servers with specialized software that are available to rent at a fraction of the cost of buying your own computers. You can now stand in any field on the planet and hold a tremendous amount of site-specific field data in your hands.

that are connected with sensors and switches. Instead of wasting human time to record farm actions like when you seeded, changed rates and crop inputs, identified crop pests and updated field records, yield and moisture by area, the loads hauled and bins managed… what if the data was collected automatically by your tools?

That information alone is just a record of what you did. But aggregated over years and compared to thousands of farms, it will display patterns and management choices that are the most valuable. History has examples of countries and societies that forgot how to farm. Perhaps the adoption of reduced tillage practices would not have taken decades if better data was available? Benchmarking the actions and results to validate best practices is an old concept, but aggregated data can make it a powerful tool again as we discuss climate change and environmental stewardship.

The assembly line continues to be the most efficient method to produce most of the products in the world today. Imagine what we can produce with precision agriculture once we figure out how to operate its virtual assembly line efficiently.

Your smartphone or tablet may enable your great leap forward, but first you need to learn to navigate the platforms, websites and apps, just like you learned how to drive. I encourage you to try out the numerous websites and apps to see the features and options available.

The ultimate precision agriculture platform hasn’t been created yet, as companies are still gathering the parts and building the assembly platforms. More fieldwork is required to determine the correct stacking sequence for the data layers and how many years and layers of data are required. How many in-season images, soil tests or weather stations are required to collect sufficient data is still being debated. New products and services are being developed, but unlike the Model T, precision agriculture can tailor the service levels or products to each specific farm. Prices, features and options will vary just like your vehicle choices today.

Technology convergence has the potential to fill the needs of many stakeholders because the resulting software platform doesn’t cost much to operate and deliver through the Internet. It is difficult to determine what the most popular precision agriculture platform will look like in 2020 and who will own it, but farmers will have the most advanced tools to monitor their operations, their crops and the environment. Farmers will continue to rely on their experiences to make decisions every day and the measurement tools will be better.

Imagine if the “Internet of Things” was actually functioning on your farm to catalogue every action performed. The Internet of Things (IoT) is the network of devices, equipment and buildings

Developing fertilizer management zones for variable rate fertilizer application.

by Ross H. McKenzie PhD, P.Ag.

The objective of variable rate fertilizer (VRF) application is to optimize fertilizer inputs for different soil areas within a field to achieve optimum crop production. Fertilizer rates and types are changed according to a preset prescription field map that is developed based on various types of mapping information.

Working with your agronomist, decide what the most important soil factors are that need to be delineated in your fields to identify site-specific management zones that have lower, medium and higher crop production potential. Some of the variable soil chemical factors include per cent soil organic matter levels, variation in soil pH, variation in EC (electrical conductivity, a measure of soil salinity), and SAR (sodium adsorption ratio, a measure of sodium in the soil). Some of the variable physical factors include variation of depth of topsoil, depth to subsoil, soil texture, soil water holding capacity, high water table areas or wet depressional areas.

Crop yield maps: Yield maps are generated when crop yield and geographic position data are recorded with your combine at harvest, and show high, medium and low yielding areas within each field. Yield differences are not always related with variable soil factors; they can result from variable disease, insect pressure or wet areas within a field. Yield maps may vary considerably from year to year, but combining yield maps over a period of years can be helpful to identify similarities.

Topography maps: Topography is often strongly related to soil differences and the effects of how variable soils have developed on variable landscapes. For example, hilltops and upper slope positions generally have lower soil organic matter, a thin layer of topsoil, shallow depth to subsoil and higher soil pH. Delineating upper, mid, lower and depressional slope positions are an excellent way to identify soil crop management zones. One of the best programs to generate a very good topography map was developed by Bob MacMillan (retired from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada), called LandMapR. Fig. 1 shows a topography map developed from elevation data collected at harvest from a field near Lethbridge, Alta. The topography map very nicely delineates upper, mid and lower slope positions, which can be closely related to uniquely different soil areas.

Drone and satellite imagery maps: Near infrared (NIR) imagery by satellites or drones is used to assess plant growth during the growing season. Differences in reflectance from the crop canopy may be related to higher or lower relative biomass differences, which may be associated with higher or lower crop yield potential. Variability in weed, disease and insect pressure that are not related to soil variation can confound interpretation of imagery information. To successfully develop soil/crop zone maps, imagery from a number of good crop

Topographic map of a field near Lethbridge, generated from elevation data using LandMapR.

production years must be collectively utilized to identify areas within a field with consistently higher versus lower productivity. It is important to determine if the differences in biomass are related to differences in soil types and soil fertility, or other crop production factors. Fig. 2 shows an example of a soil/crop zone map developed from satellite imagery.