TOP CROP MANAGER

LEAF DISEASE IN OAT

Studying integrated disease management

PG. 12

FOLIAR

FUNGICIDES

New registrations and updates

PG. 33

SOIL FUMIGATION

Controlling clubroot severity in localized areas

PG. 40

Studying integrated disease management

PG. 12

New registrations and updates

PG. 33

Controlling clubroot severity in localized areas

PG. 40

Timing doesn’t get more crucial than at harvest. That’s why you’ll appreciate the rapid action of new Heat® LQ herbicide. Registered for use in field peas, soybeans, dry beans, sunflowers and canola, it’s the only harvest aid that gives you a faster crop dry down plus exceptional broadleaf weed control, including perennials. Heat LQ also enables straight-cutting canola for a faster, more efficient harvest. So get time on your side this season. Visit agsolutions.ca/HeatLQPreharvest or contact AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273) today.

Always read and follow label directions.

PESTS AND DISEASES

6 | Pasmo, lodging and fungicides

Two yield-limiting problems in flax sometimes have a shared solution.

By Carolyn King

PESTS AND DISEASES

20 The barberry connection with stem rust

By Carolyn King

33 Foliar fungicide and seed treatment update

By Bruce Barker

50 New insecticide registrations and label updates

By Bruce Barker

12 | Managing leaf disease in oats

Integrated disease management of crown rust and leaf spotting diseases.

By Donna Fleury

PESTS AND DISEASES

36 | Goss’s wilt on the Prairies

An update on its spread and efforts to manage this troublesome corn disease.

By Carolyn King

CEREALS

26 Resisting leaf spots and root rots in wheat

By Carolyn King

48 FHB a challenge for durum growers

By Donna Fleury CANOLA

40 Soil fumigation to manage clubroot

By Donna Fleury

CROP MANAGEMENT

16 Measuring sustainability By Carolyn King

45 In-crop nitrogen fertilizer applications By Ross H. McKenzie, PhD, P. Ag.

FROM THE EDITOR

4 Viruses, and bacteria and fungi, oh my! By Janet Kanters

CORRECTION: In the March 2015 issue of TopCropManager , we inadvertently mixed up some words when explaining charged soil particles. On page 44, after the subhead Nitrogen and nitrates, the paragraph should read: Nitrogen (N) in various fertilizers and livestock manure is converted by soil microbes to nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N), the primary form of N that plants take up. Nitrate is negatively charged and is not held by negatively charged soil particles. Therefore, higher levels of nitrate in soil coupled with excess rainfall or irrigation can result in leaching of nitrate through the soil root zone and into groundwater.

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

JANET KANTERS | EDITOR

As I write this, I am surrounded by popular accoutrements used to combat the common cold. Perhaps “combat” is not the correct word – I already have the cold, and rather than combatting it, I am simply easing the virus symptoms. And while indeed soothing, the warm mist humidifier, the cup of hot tea, the tissues, cough syrup and pain relievers, sadly, do nothing to stave off the cold virus in the first place.

It is no secret viral diseases are the bane of human existence. Smallpox, polio, influenza, hepatitis, measles and other viruses have, over millennia, caused untold suffering and death in human populations the world over. Bacterial diseases, such as pneumonia, Lyme disease, cholera and tuberculosis, to name just a few, can also cause deadly outbreaks among humans. And, fungal diseases cause a litany of woes as well, from fungal infections of the skin (think Athlete’s foot), nails and eyes, to more serious infections such as allergic fungal sinusitis and candida infections.

Viral, bacterial and fungal diseases also cause many important plant diseases, and are responsible for huge losses in crop production and quality in all parts of the world. While most plant diseases – around 85 per cent – are caused by fungal or fungal-like organisms, other serious diseases of food and feed crops are caused by viral and bacterial organisms. And just like a medical doctor, a farmer must know how to assess the plant’s infection to determine its ailment and appropriate treatment.

A sign of plant disease is physical evidence of the pathogen. For example, fungal fruiting bodies are a sign of disease. When you look at powdery mildew on a pea leaf, you’re actually looking at the parasitic fungal disease organism itself (Erysiphe pisi).

A symptom of plant disease is a visible effect of disease on the plant, such as a change in colour or shape of the plant as it responds to the pathogen. Leaf wilting is a typical symptom of verticillium wilt (Verticillium longisporum) in canola. Bacterial blight (Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea) symptoms on soybean include red or black lesions with a yellow halo and a shiny centre on the leaves of infected plants.

In humans, there are various medicines and treatments we can take to stave off viral, bacterial and fungal infections, and there are also treatments designed to lessen the severity of these diseases.

The same holds true in the plant world. While disease risk and development depend on the interaction of the host, the environment and the pathogen, evaluating those three factors in each field is essential for effective treatment decisions.

In this issue of Top Crop Manager, we feature several stories on fungal diseases in crops, including leaf spot in wheat, oats and durum, crown rust in oats, Fusarium head blight in durum and pasmo in flax. Also in this issue of the magazine, we feature our annual Fungicide Guide, which lists – in chart format – fungicides currently registered for diseases in cereals, oilseeds, pulses, potatoes and specialty crops.

A great addition to this year’s Fungicide Guide is information gleaned from well-known plant pathologists Kelly Turkington with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and Randy Kutcher with the University of Saskatchewan, who provided us with in-depth information on how fungicides actually work, and tips on how you can make the most of your fungicide applications.

Although we can’t foresee and quite often can’t stop the march of plant diseases, as we head into another cropping season, we can certainly be prepared to face those diseases head-on to ensure our crops remain healthy and profitable from seeding to harvest.

VOL. 41, NO. 7

Fredericks

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710 RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT. P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 subscribe@topcropmanager.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

CIRCULATION email: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES Top Crop Manager West - 9 issuesFebruary, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, September, October, November and December1 Year - $45.00 Cdn.

Case IH introduced agriculture to the benefits of having four tracks nearly 20 years ago. And we’ve been the ones perfecting track technology ever since. Our legendary Steiger ® Quadtrac® and Rowtrac™ series tractors feature four, independent oscillating tracks on an exclusive five-axle design. It’s an agronomic design that provides you with better traction, superior flotation, reduced compaction and a great overall ride. So if you’re looking to maximize productivity and performance in even the toughest conditions, look no further than the tested and proven track leaders at Case IH. See the difference for yourself at your local Case IH dealer or online at caseih.com/steiger

Two

yield-limiting problems in flax sometimes have a shared solution.

by Carolyn King

Afew years ago, Cecil Vera, a biologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Melfort, Sask., was running one of the trials in a major flax project. He happened to notice that, in one particular year, lodging was dramatically reduced in his plots where a fungicide had been applied. That intriguing observation led him to start studying the relationship between lodging and pasmo, and the role of fungicide applications in dealing with both problems. Lodging and pasmo are both serious issues in flax. Vera’s research shows when lodging occurs, it causes seed yield reductions averaging 32 per cent in flax, compared to 16 per cent in wheat. Disease surveys show pasmo is the most common flax disease on the Prairies – in some years, pasmo has been found in 100 per cent of surveyed flax fields in Saskatchewan. Pasmo incidence (proportion of plants infected) and severity (degree of infection on affected plants) vary quite a bit from year to year and place to place, depending on weather. Field observations suggest typical yield reductions from severe infestations tend to be around 10 to 20 per

cent or more.

Pasmo and lodging are sometimes seen in association with each other, but Vera says there is some debate around the exact relationship between the two problems. “Some scientists, particularly plant breeders, believe lodging may cause plants to become infected with pasmo as they fall closer to the ground, which is a possibility. However, I believe it’s the other way around [that pasmo promotes lodging].”

He adds, “It could be both ways. I see pasmo and lodging as complex phenomena, with many factors involved, and sometimes, when not all the factors are present, these two events may not take place or, if they do, their expression may be less evident.”

Pasmo is caused by the fungus Septoria linicola, and is favoured by wet conditions, including rain and high humidity. The patho -

ABOVE: Researchers are assessing the effects of fungicides on lodging, pasmo, crop maturity, seed yield, seed weight and test weight of flax.

gen overwinters as little black bodies (pycnidia) on flax residues or as spores on flax seeds. Although infested seed can cause the disease, pasmo infestations usually start from infected residues. In the spring, the pycnidia release spores that infect the foliage.

“The initial symptoms are little brown flecks on the leaves. About late August, the stem will start to get a mottled appearance, with green or yellow healthy tissue and then dark brown patches where the fungus is infecting the stem,” Randy Kutcher, a plant pathologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, says.

Pasmo can cause defoliation, shrivelled seeds and boll drop, and severe infections can cause the plant to die. Pasmo can also predispose a plant to lodging because the infection weakens the stem. On the other hand, a lodged flax crop can trap moisture around the plants, providing ideal conditions for the disease.

Vera thinks the stronger association between lodging and yield losses in flax, as compared to wheat, could be because pasmo is playing a part in the yield losses attributed to lodging.

To examine the association between pasmo, lodging and flax seed yield, Vera conducted a four-year project, from 2009 to 2012, at Melfort. The treatments included Headline EC (pyraclostrobin) application versus no fungicide application; and five nitrogen fertilizer rates (0, 33, 66, 100 and 133 per cent of the recommended rate).

Vera found that Headline application reduced pasmo severity and increased yield in the three years when pasmo occurred in the plots (2010, 2011 and 2012). The fungicide also prevented or reduced lodging in the two years when lodging occurred (2010 and 2012).

Headline’s effect on lodging was especially clear in 2010. Interestingly, although lodging was more severe in 2010, pasmo levels were lower that year, compared to 2012. According to Vera, these results indicate pasmo is just one of the causal factors involved in lodging. For example, he thinks unusually wet conditions in 2010 may have contributed to the more severe lodging. That year, the growing season was very rainy, and the field with the flax plots had

a lot of water accumulation at certain times.

The project’s results also showed both the severity of pasmo and the amount of lodging increased as nitrogen fertilizer rates increased.

Vera is now leading a three-year project, which started in 2014, to answer some of the questions sparked by his initial study. So the project is taking a deeper look at the association between lodging and pasmo, and the effects of fungicides.

Vera is working with Kutcher, Ramona Mohr, an agronomist with AAFC in Brandon, and Jan Slaski, a plant physiologist with Alberta Innovates – Technology Futures (AITF) in Vegreville. The sites are at Melfort and Saskatoon, Sask., Brandon, Man. and Vegreville, Alta.

The researchers are assessing the effects of fungicides on lodging, pasmo, crop maturity, and seed yield, weight, test weight, oil content and protein content of CDC Bethune flax. In particular, they would like to determine if the fungicide’s effect on lodging, as shown in Vera’s initial project, was because of Headline’s particular mode of action or if other types of fungicides might also provide similar benefits. Vera notes, “Farmers have observed that Headline may result in higher yields even in the absence of disease, which may indicate Headline has other properties, not just fungicidal properties, that are affecting yield.”

So the researchers are comparing three fungicide products: Headline EC (pyraclostrobin, Group 11), Xemium (fluxapyroxad, Group 7), and Priaxor (a combination of pyraclostrobin and fluxapyroxad). Until recently, Headline was the only fungicide registered to control pasmo in flax on the Prairies. However, Priaxor was registered in 2014 and is available in Western Canada for the 2015 growing season for use on flax, as well as canola, pulses, corn and soybeans.

The researchers are also comparing three fungicide timing options: “early,” which is the recommended application time at about seven days after flower initiation; “late,” which is about seven days after the early application time; and early plus late.

Wind speed, pressure gauge, optimal nozzle settings, check. All systems are go and it’s time to take down the toughest weeds in your wheat eld, whether they’re resistant or not. With three different modes of action in a single solution, Velocity m3 herbicide provides you with exceptional activity on over 29 different tough-to-control grassy and broadleaf weeds.

For more information, please visit: BayerCropScience.ca/Velocitym3

In addition, the project includes a proactive study on fungicide resistance in the pasmo pathogen. The researchers are collecting samples of plant tissues with the disease from the project’s four sites each year. Starting this spring, Trisha Islam, Kutcher’s new graduate student, will be culturing genetically uniform isolates from the samples. Then she’ll test the isolates to determine their sensitivity to different concentrations of Headline and Xemium.

“In Western Canada, with so little fungicide being applied 20 years ago or even 10 years ago, fungicide resistance wasn’t as big a concern. But we know from Europe and other countries that fungicide resistance is quite common,” Kutcher explains. “[With fungicide use increasing on the Prairies,] we need to start looking at the issue.

“I don’t expect we’ll find fungicide resistance at this point, although it is possible,” he adds. “What we want to do is set a baseline so we know the normal level of sensitivity of the pathogen to these fungicides right now. Then in the future, if farmers start to find the products are no longer working the way they used to, we’ll be able to determine if it is because the pathogen has become insensitive

to the fungicide.”

Headline’s active ingredient belongs to the QoI, or strobilurin, family of fungicide chemicals. QoI resistance is found in strains of various pathogens in various countries; some Canadian examples include the pathogen that causes ascochyta blight in chickpea, the apple scab pathogen, and the pathogen that causes early blight in potatoes.

“Headline is very effective on a lot of different diseases in a lot of crops. That tends to increase the risk of resistance if a grower is using that one product repeatedly on many crops and diseases,” Kutcher notes.

“[Fungicide application on flax] is becoming quite routine for some growers, especially because the last few years have been pretty wet, particularly in June and July. So pasmo, for many growers, has been above what was typically seen 10 or 15 years ago.”

The first year of the project produced some interesting preliminary results. “In general, fungicide application decreased disease infection and increased seed yield, seed weight, test weight and oil

content, but delayed maturity of flax at some locations,” Vera says. None of the three application times was clearly superior to the others. He explains, “This means that dual early plus late application may not always be superior to a single (early or late) application. Disease infection was low to medium at most sites and absent at Vegreville, and conditions favourable to the expression of lodging were also lacking at all sites, which prevented the opportunity to study the association of pasmo and lodging in 2014.”

Vera’s studies and other research point to several practices that help in dealing with pasmo and lodging.

“The use of a fungicide, such as Headline EC, has been shown to control disease and, in some cases, severe lodging in flax. Headline has also been observed to increase seed yield, even in the absence of disease. Other products, such as Xemium and Priaxor, may prove to be as effective,” he says.

Previous research by Slaski and Vera has shown that early seeding

(mid-May) helps prevent lodging, perhaps because early seeded flax produces shorter and more robust plants. This research also showed that flax seeding rates greater than the recommended 40 pounds per acre (45 kilograms per hectare) increased the severity of lodging.

“Farmers in North Dakota have been advised not to over-fertilize flax,” Vera notes. His own research shows high nitrogen rates are associated with increased lodging and pasmo, which both reduce yields.

To reduce the risk of fungicide resistance, growers can use the same types of strategies that are used to reduce the risk of herbicide resistance. Kutcher says, “Growers should try to use all of the [integrated pest management] practices they can to prevent crop disease, not just rely on fungicides. And when they use fungicides, they should try to rotate fungicides from different groups when available, or use products with more than one active. If they use the same family of fungicides over and over, they will select for resistant strains of the pathogen.”

Top-performing annual broadleaf weed control + superior resistance management.

• Excellent weed control performance in oats, wheat and barley

• Controls cleavers, buckwheat, chickweed, hemp-nettle, kochia, more

• Two modes of action, three actives, overlapping control

• Get all the benefits of Stellar in your oats too Go to the new dowagro.ca or call 1.800.667.3852.

Integrated disease management of crown rust and leaf spotting diseases.

by Donna Fleury

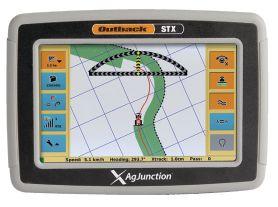

According to Randy Kutcher, associate professor of cereal and flax pathology at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S), crown rust, which is essentially leaf rust, is the biggest issue with growing oats in Saskatchewan. “Although crown rust is not a problem every year, nor is it even that widespread, there are a lot of alternate hosts around for Puccinia coronata to complete its lifecycle, and this makes the disease a potential problem,” he notes. “Along the South Saskatchewan River valley and even around the university campus, the buckthorn shrub that serves as an alternate host is very prevalent. Leaf spot diseases, caused by the pathogens Pyrenophora avenae, Cochliobolus sativus and Septoria avenae, so far seem to be more of a problem for Manitoba growers.”

In a recent two-year research project led by Kutcher, oat disease surveys were conducted in Saskatchewan, along with field experiments at Saskatoon and Melfort. The objective of the research was to determine the effect of conventional fungicides and oat cultivars that vary in resistance to crown rust and leaf spot and to crown rust severity. Researchers also wanted to determine the effects on oat yield and quality.

“In the disease surveys, crown rust was the primary pathogen present at Saskatoon, and disease was severe in field plots and neighbouring fields,” Kutcher explains. “In 2012, natural levels of crown rust were high even in other trials and nearby breeder’s plots.

In areas along the South Saskatchewan River and in a radius of about 30 miles around Saskatoon, crown rust has been a problem for oat growers in recent years. “However, in 2014, once you got out of the city east towards Humboldt, for example, there was little crown rust,” he adds. “The growers along the river are at a higher risk, which is likely because of the prevalence of the alternate host and the fact the pathogen overwinters quite easily and spreads very early in the season.”

In disease surveys at Melfort, crown rust was not observed. Leaf spot severity was low in Saskatoon, but low to moderate in Melfort.

In the field trials at Saskatoon and Melfort in 2013 and 2014, the first experiment compared three oat varieties: AC Morgan (crown rust susceptible), CDC Dancer (intermediate) and CDC Morrison (resistant); and three fungicide treatments: check (unsprayed), propiconazole and pyraclostrobin (Headline). The plots at Saskatoon were inoculated with a mixture of crown rust races to ensure a high risk of infection, while plots at Melfort were not inoculated.

Severe crown rust occurred at Saskatoon in 2013, with an average severity of 93 per cent (damage to 93 per cent of the flag leaf at the soft dough stage of the crop) on the crown rust susceptible cultivar AC Morgan (unsprayed check). Propiconazole and pyraclostrobin reduced crown rust severity of AC Morgan to 46 and 70 per cent, respectively. Overall, the results showed the fungicide reduced severity of crown rust and increased yield and quality of oat at Saskatoon for the susceptible variety (AC Morgan) and somewhat for the moderately susceptible variety (CDC Dancer). The crown rust resistant variety (CDC Morrison) did not benefit from fungicide.

You might think that when nitrogen fertilizer is in the ground, it’s safe. New research suggests you need to think again. When shallow banding unprotected urea less than two inches deep, researchers found that nitrogen loss due to ammonia volatilization can be even greater than unprotected broadcast urea. Protect your nitrogen while maintaining the operational efficiencies of side banding or mid-row banding at seeding by using AGROTAIN® DRI-MAXX nitrogen stabilizer. Whether you choose to band or broadcast, you’ll be confident that you’re protecting your nitrogen investment, your yield potential and your return on investment.

Ask your retailer to protect your urea today with AGROTAIN® DRI-MAXX nitrogen stabilizer.

agrotain.com/getthedirt

Leaf spot severity was low, but reduced by fungicide application at Melfort; little increase in yield or quality was detected. There was little difference between AC Morgan and CDC Morrison for leaf spot symptoms, but CDC Dancer appeared to suffer slightly more than the other varieties. There was no impact of fungicide on beta-glucan content at either location, although there were differences among varieties at both locations.

“In Saskatoon, we did see improved disease control with the use of fungicides because of the high level of crown rust,” Kutcher notes. “However, at Melfort, with little disease we didn’t see any benefit of spraying with a fungicide. These results are similar to what we saw several years ago in Melfort, where disease levels were rarely a concern.”

In terms of crop yield, both fungicides increased yield of AC Morgan compared with the unsprayed check. However, yields of CDC Dancer and CDC Morrison were not increased with the use of either fungicide.

“Many growers choose to grow AC Morgan, which is a standout variety in terms of yield if you don’t have any disease issues,” Kutcher says. “However, selecting a resistant variety like CDC Morrison may be a good strategy in areas where crown rust is a problem and growers don’t want to use a fungicide. CDC Morrison is not only resistant to crown rust, it also has at least 50 to 60 per cent higher beta glucan than AC Morgan or other popular varieties. In our tests, the beta glucan levels of AC Morgan were four to 4.5 per cent, while CDC Morrison was seven per cent or higher. Should a premium become available for beta glucan, growers may want to consider growing a variety like CDC Morrison regardless of disease issues.”

A second experiment was conducted to determine the effect of the product Actigard on disease severity, oat yield and quality. The product has no direct activity against target pathogens, but induces

systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in the plant.

Actigard was applied at two rates, 8.75 g ai/ha and 26.25 g ai/ ha, and at three crop growth stages: seedling, boot and heading, on varieties CDC Dancer and CDC Morrison, with an unsprayed check for each variety. The results of four site years of trials didn’t show any effect on crown rust or leaf spot disease severity or any other of the factors measured. There were no positive or negative effects from using the product.

“We are planning to repeat the fungicide by variety trials again in 2015 at both Saskatoon and Melfort, which will provide us with six site years of data,” Kutcher says. “The results so far are consistent. So for growers using a susceptible variety, they should probably apply a fungicide as soon as they see crown rust.

“However, by growing a resistant variety, you probably don’t have to spray at all. So far, CDC Morrison, a resistant variety, is standing up very well to crown rust. In a year with no disease, this variety may yield up to 10 per cent less, however if you have crown rust, then yields can double without having to apply a fungicide,” he adds.

Another related U of S project was funded at the end of 2014 and is focusing on leaf spot disease in oat. Led by Aaron Beattie and Tajinder Grewal, researchers will be collecting isolates of Pyrenophora avenae, Cochliobolus sativus and Septoria avenae, and screening germplasm to try to breed for oat resistance to leaf spots.

“Although it’s not a big problem yet in Saskatchewan, we expect it to be more of an issue in the future,” Kutcher says. “Watch for more information from both of these projects over the next couple of years.” For more on leaf diseases, visit topcropmanager.com.

Tough broadleaves and flushing grassy weeds have met their match. No burndown product is more ruthless against problem weeds in spring wheat than new INFERNO™ DUO. Two active ingredients working together with glyphosate get hard-to-kill weeds like dandelion, hawk’s beard, foxtail barley and Roundup Ready® canola, while giving you longer-lasting residual control of grassy weeds like green foxtail and up to two weeks for wild oats. INFERNO DUO. It takes burndown to the next level.

INFERNO DUO is now eligible for AIR MILES® reward miles through the Arysta LifeScience Rewards Program in Western Canada.

Go to www.arystalifesciencerewards.ca for program details and learn how you can earn 100 bonus AIR MILES® reward miles.

by Carolyn King

As the demand for sustainably produced foods increases, crop growers will be asked more often to participate in programs that measure the sustainability of their production systems. Canadian initiatives are underway to help ensure these programs work for the marketplace and for growers.

For growers, potential benefits from participating in sustainability measurement programs include maintaining market access, maintaining public trust in agriculture and further enhancing the sustainability of their operations. One concern is the need to do extra paperwork for no extra dollars, when participating in these programs becomes simply a matter of doing business. A related concern is, given the many different programs nationally and internationally, growers might have to meet different requirements for different crops and different markets. Another worry is some programs might have unrealistic requirements for production practices.

According to Karla Bergstrom, policy analyst with the Alberta

Canola Producers Commission (ACPC), market access is a key issue. “Two-thirds of the world’s food production is being purchased by multinational companies such as Nestle, PepsiCo, General Mills, Kellogg’s, Unilever and others. They are all working on sustainability platforms and they are looking at having their entire supply chains having sustainability standards in place. Some are working towards verifying their sustainable sourcing by 2016 or 2020,” she says. “Agricultural producers are one of largest suppliers within their supply chains, so these companies need to have their producers on board if they are going with sustainable sourcing.”

Mark Brock, co-chair of the Canadian Roundtable for Sustainable Crops and chairman of Grain Farmers of Ontario, adds: “Initially there might be potential for a low-level premium, but in the long term, participating in some form of sustainability program

ABOVE: Grain Farmers of Ontario is working with the Round Table on Responsible Soy’s certification system.

is going to be a matter of maintaining existing markets, especially with the European Union.”

Bergstrom points to the value of participating in such programs as a way for growers to improve transparency and maintain the public’s trust. “Farmers are very highly trusted individuals within our society, but some of their farming practices are becoming more scrutinized by consumers,” she says.

“We want our farmers to be able to continue operating with minimal restrictions and regulations. So the concept of sustainability needs to be a priority for farmers to make sure they are maintaining public trust. Because they are good stewards of the land, they are doing a number of things right, and because the farming population is so much smaller than the consumer population, we need to make sure that message is conveyed so farmers can continue to produce the high quality, safe food they have been producing for a long time.”

Brock notes the Canadian crop industry already has many of the pieces in place to meet the standards in various programs for social, environmental and economic sustainability. “For us, social sustainability isn’t too hard to accomplish because we have things like minimum wage standards, health and safety standards, and so on. With environmental sustainability, we’re pretty close to checking all the boxes too. We have to make sure [the program requirements] don’t put us economically at risk as producers, so that is something we keep in mind during discussions around these programs.”

One concern for crop growers is who decides what these programs require, the validity of them and what is really involved from a producer’s standpoint. “That is why organizations like Grain Farmers of Ontario and the Canadian Roundtable for Sustainable Crops are taking a proactive approach,” Brock says. “We want to be engaged with these companies and importers so we can have some influence on what they deem as a worthy sustainability program that they feel comfortable taking back to their consumers, so the program won’t be horribly onerous for our producers.”

Sustainability measurement is a key

The initiative to develop the Canadian Field Print Calculator is another effort that shares its findings through the CRSC. The calculator is an Excel-based tool to measure the environmental footprint of crop operations. Rather than providing a certification system for individual growers, it calculates regional indicators.

Pulse Canada is managing the development of the calculator and other projects of the Canadian Field Print Initiative, which has a membership that includes producer groups, crop input associations, crop consultant agencies, retail associations, conservation agencies and companies like General Mills Inc. The members are working with Serecon, a consulting firm.

According to Denis Tremorin, director of sustainability at Pulse Canada, the calculator emulates work in the U.S. called Field to Market. “ Our contact with General Mills is the chair of that organization, which includes crop input providers, fertilizer associations, food companies, retailers, restaurant chains. They have a Fieldprint Calculator and they’ve created an indicators report, like we have. They started in 2009, and we started in 2011.” Tremorin has made presentations to Field to Market about the Canadian initiative, and some of the other agencies involved in the U.S. group have expressed an interest in also being a part of the Canadian initiative.

The initial version of the Canadian Field Print Calculator, created in 2012, is for pea, oat, spring wheat and canola crops grown in Western Canada; pilot testing over the last two years has helped refine the tool and build data for regional comparisons.

“We are currently creating our 2.0 version of the calculator. We’re including lentils, durum wheat, winter wheat, flax and soybeans in the west, and we’re expanding into Ontario for corn, soy and wheat,” Tremorin notes. Eventually the initiative aims to have a national calculator.

According to Tremorin, the calculator has two key purposes. One is to provide data on sustainability indicators requested by the marketplace including: greenhouse gas emissions, soil erosion, energy use, land use efficiency (related to crop yield) and soil organic carbon levels. The initiative is now developing a water quality metric for Ontario.

The other purpose is to provide data to help growers improve their on-farm efficiency. “As a group of people working on this calculator, we can’t ensure a premium [for growers who use the calculator]; that is up to the market to decide,” he says. “But we can develop a tool that shows value for the grower.” So the calculator compares the grower’s data with aggregated data from other farms (see diagram), and it expresses the grower’s own data in useful ways, like breaking down the energy use data by operation to show which operations use the most fuel.

The calculator asks growers to provide each field’s legal land location (which the calculator uses to determine soil and climate information), crop yield, fertilizer rates and fuel use in all equipment operations, such as seeding, tilling, spraying and harvesting.

“We’re trying to get the information in a way that is as easy as possible for the grower,” Tremorin says. “And we’re giving alternatives so if the grower doesn’t have the information there’s a good backup source of information. For instance, if you don’t know your fuel use, you can provide the horsepower of your unit and the amount of hours you spent in the field, and then the tool calculates the fuel use.”

As well, the initiative is working with companies like Farmers Edge and Agri-Trend to integrate the calculator into their software. Tremorin explains, “For example, over half of the data that our tool asks for is already being supplied within the system that Farmers Edge uses with farms. If we integrate the calculator into their system, a grower working with that company wouldn’t have to input the information twice.”

For growers with concerns that data from the calculator might be used to force them to follow particular farming practices, Tremorin explains the calculator preserves the privacy of participating growers through two approaches.

First of all, the calculator provides the marketplace with the aggregated data of many growers, not the data of individual growers. He explains that companies like General Mills want two types of data. “They want the averaged data – so, wheat from this region has an average of this number. And they want the distribution of the data – so how are the best performing producers different from the average or below-average producers, and why? That information allows the companies to make decisions on how they want to act within the supply chain.”

In addition, the calculator is outcome-focused, not practice-based. Tremorin says, “I think everybody in the supply chain can agree we want to continually move towards a system that is more efficient and more productive. That aligns with the goals of this calculator.”

Growers who want to use the calculator can access it at fieldprint.ca.

focus of the Canadian Roundtable for Sustainable Crops (CRSC). Formed in 2014, this multi-stakeholder initiative includes commodity groups, agricultural input associations, and companies like Cargill and McDonald’s.

According to Brock, the CRSC has a two-pronged approach to sustainability metrics. “One approach is to do some research and fact finding to identify the gaps right now in some of these programs that we’ve been looking at from a Canadian standpoint, gathering ideas around regional differences, and seeing what more work needs to be done. The other approach is to communicate [about sustainable crop production] (a) to farmers, (b) to the value chain, and (c) to retailers, exporters and importers who are looking to source sustainably grown products.”

Part of the challenge for the CRSC, and for individual crop commodity groups, is evaluating the many different sustainability programs, which range from certification of individual growers to determining sustainability indicators on a regional basis.

“It seems lie every quarter there’s a new sustainability program popping up that someone is working on,” Brock says. “Long

term, it would be nice if we can get to a Canadian branding of sustainability, and maybe a single program – for instance, if 85 per cent of the needs for a sustainability program could be met with a base program, and perhaps a few additional paperwork items for different crops to address some specific needs. I’m not sure if we can achieve that [given the many different crops and the regional differences across Canada], but it would be good to work towards something like that.”

The CRSC provides a forum for sharing results of activities across the country to assess, develop and implement sustainability platforms. Various efforts are underway already. For instance, a multiagency initiative is developing the Canadian Field Print Calculator; Alberta grower groups are assessing five platforms in the Alberta Crop Sustainability Pilot Project; the Canadian canola industry uses the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification system for canola going into the European biodiesel market; and Grain Farmers of Ontario is leading the Canadian version of the Round Table on Responsible Soy’s certification system because of a European market for sustainably grown soybeans. In addition, the CRSC, the Canadian Roundtable for Sustainable Beef and other stakeholders have a joint pilot project to develop an approach for identifying sustainably grown feed barley for use in sustainably grown beef production.

“The purpose of the Alberta Crop Sustainability Pilot Project is to get a really good understanding of the readiness of our producers to incorporate some of these sustainability standards,” Bergstrom says. “Are we ready now? Are there areas that we need to improve on? And how do our farmers rank internationally?”

The Alberta Wheat Commission and Alberta Barley initiated the project, and they brought the Alberta Pulse Growers Commission and ACPC on board. The four commissions are working on the project with Control Union, an international certifying auditor.

They are comparing four international platforms as well as the Canadian Field Print Calculator. “Each platform has slightly different questions and asks for different things. That helps us get a good scope of all of the different types of questions producers could be asked to provide information for,” she notes. “The questions relate to environmental, social, food safety, farm safety and ethical choices on their farms.”

About 50 members from the four commissions, including many directors, are taking part. “For example, all 12 of the Alberta Canola Producers Commission’s directors are taking part,” Bergstrom says. “We wanted to have our directors involved so they can discuss how the whole process went and whether there is an ability to influence some of the policy around these sustainability measures.”

Currently, the participants are completing the necessary paperwork and Control Union’s auditors will be visiting their farms for the certification needed in the international programs. Then the commissions will discuss the results, report their findings to their members and the CRSC, and consider their next steps.

Who says you can’t be in two places at once? With the wide window of application and flexible rate options of Folicur® EW fungicide, it means you simply have more time to work with. Folicur EW continues to provide exceptional value for cereal growers who want long-lasting protection from a broad spectrum of diseases, including fusarium head blight and the most dangerous leaf diseases.

For more information, visit: BayerCropScience.ca/Folicur

Surveys are helping to determine the importance of these shrubs in the global threat of wheat stem rust.

by Carolyn King

Wheat stem rust is one of the most devastating diseases affecting wheat. A virulent strain is currently spreading from its origins in East Africa, posing a major threat to wheat production around the world. That threat level could ramp up even higher if the pathogen’s complicated life cycle includes a phase on barberry shrubs. So a Canadian researcher and his international colleagues are trying to get a better handle on this aspect of the disease.

Wheat stem rust is caused by the fungus Puccinia graminis tritici Under conditions that favour the disease, it can result in complete crop loss within a few weeks.

According to Tom Fetch, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) who specializes in cereal stem rust, the full life cycle of the fungus includes one phase on wheat and a second phase on barberry, the pathogen’s alternate host. “In the phase on wheat, there’s the red spore stage, which is mainly a summer stage,” he says. This stage produces urediniospores, which are able to directly infect wheat plants. These spores reproduce asexually, producing a new generation about every seven to 14 days. They can be carried by the wind for long distances.

“Then, in the pathogen’s full life cycle, the spore changes from a red spore to a black spore, or teliospore, to overwinter on wheat stubble. After overwintering, the teliospores produce spores that can infect barberry,” Fetch says.

Called basidiospores, these spores infect the barberry leaves, usually on the upper side. There the fungus produces structures called pycnia, and sexual reproduction occurs with cross-fertilization between two different mating types of pycnia. Then the fertilized fungus grows down through the barberry leaf. On the underside of the leaf, the fungus releases aeciospores, and those spores infect wheat.

The number of new strains (or races) that the fungus produces is related to whether or not it goes through the full life cycle. “New strains of wheat stem rust can develop in two main ways: asexual mutation and sexual recombination,” Fetch says.

Because the urediniospores are clones, one generation is usually the same as the next, but mutations can occur. “In areas of the world where stem rust is an issue, the [urediniospore] numbers get so high, with trillions and trillions of spores produced, that even if the mutation rate is pretty low you will get some new strains developing that way,” he notes.

“The sexual reproduction that occurs on barberry is a more

dangerous mechanism because genetic recombination commonly occurs.” So it has the potential to continually produce new strains of the pathogen.

“A particularly good illustration of this can be seen in North America after the barberry eradication programs. In the old virulence surveys [before eradication], it wasn’t uncommon to see 40 or 50 different strains of wheat stem rust in a year. Currently in North America, over the last decade we’ve had only one strain in about 95 per cent of all the isolates that we collect,” Fetch says.

“So the numbers of strains are much, much lower once you

Grain Guard’s new line of 4" wide corrugated grain bins are manufactured using state-of-theart technology and are available in diameters from 15' to 105' in flat bottom models, as well as 15' to 27' in hopper bottom models. With an established catalogue of aeration and conditioning equipment, high-quality grain storage bins are yet another solution provided by Grain Guard.

Our research and development team has put in countless hours working to improve our Classic Rocket design. Resulting in an innovative, stronger and even more reliable rocket; The Next Generation Rocket

The revolutionary Retro Rocket is the only do-it-yourself rocket system that allows you to retrofit existing hopper bottom and smooth-walled bins with farm proven Grain Guard aeration.

Grain Guard also offers turnkey construction packages on all flat bottom bin models. Trust the storage and conditioning experts to be your one-stop shop.

eliminate the barberry host, and that makes it a whole lot easier to breed for wheat stem rust resistance.”

Common barberry (Berberis vulgaris) was the barberry species that contributed to the wheat stem rust epidemics in the first half of the 20th century in North America. “Common barberry is a native species in central and western Asia and eastern Europe. When European settlers came to the New World, they brought barberry with them. It’s an attractive-looking shrub that has nice red leaves in the fall and produces big, bright red berries that can be used for jams, jellies and pies. The plant also has some medicinal properties. And the settlers used the stems to make brooms and so on,” Fetch says. “They didn’t realize that barberry was contributing to wheat stem rust until the late 1800s and early 1900s.”

As people became aware of a link between barberry and wheat stem rust, various jurisdictions in Canada and the U.S. began to pass laws to require removal of barberry. In the three Prairie provinces, barberry was declared a noxious weed in 1917. The U.S. brought in eradication laws in 1918, and in Canada in 1919 a

federal law prohibited barberry.

Fetch says, “Starting in about 1918, particularly in the Great Plains of the U.S. and the Prairies of Canada, they pulled out all of the common barberry plants they could find. Today in the Prairie region, it would be very difficult to find one.”

These eradication efforts not only reduced the amount of rust inoculum on the Prairies, but also allowed the development of stem rust-resistant wheat varieties because wheat breeders had fewer stem rust races to deal with. Through ongoing breeding work, including the development of wheat varieties with multiple genes for stem rust resistance, the disease is currently under control on the Prairies, with the last epidemics occurring from 1953 to 1955.

Today, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) regulates Berberis, Mahonia and Mahoberberis plants in the barberry family. Only stem rust-resistant varieties can be imported and sold here. Some populations of common barberry still remain in certain locations in Canada. The shrubs would have to be within at least 10 kilometres of a wheat field to be a concern because the basidiospores

tend to dry out and die within a few kilometres of their release from wheat stubble.

One of Fetch’s responsibilities is to conduct surveys in Canada to collect samples of rust species from wheat, barley and oat crops to identify the current races, watch for new ones and test their virulence. Rust researchers in other countries are also doing this type of work.

The spread of Ug99, a very virulent race of wheat stem rust, is a reminder of just how serious this disease can be. Ug99 was first detected in Uganda in 1999, when it overcame a wheat stem rust resistance gene commonly used by breeders around the world. Since then, the pathogen has mutated several more times to overcome other important resistance genes; there are now eight known variants. Many wheat varieties in Canada and around the world are vulnerable to Ug99 and its variants. This race has spread from Uganda into most of eastern Africa, over to Yemen and Iran, and as

far south as South Africa.

While Canadian wheat breeders work to develop Ug99-resistant varieties, Fetch is actively involved in watching for the spread of Ug99 into the Americas. A key way it could arrive is by wind dispersal.

“There are some wind patterns that can move the pathogen’s spores from southern Africa over to South America,” he notes. “So my concern a few years ago was to find out how likely this is, and if this is possible – and it appears to be at least possible – then it would be important to monitor for invasion of Ug99 under the natural movement of wind from across the Atlantic Ocean.”

So Fetch is collaborating with José Martinelli and Márcia Soares Chaves, research scientists in Rio Grande do Sul state in southern Brazil. They are working on various rust-related activities including establishing and monitoring sentinel plots in Brazil to determine which stem rust strains are present on wheat and to watch for Ug99. Stem rust surveys are also being conducted in Uruguay and Argentina.

Another aspect of Fetch’s research involves international collaborations to conduct barberry surveys. Along with common barberry, many other species of Berberis, Mahonia and Mahoberberis are found around the world; however, in many regions, their roles as alternate hosts for rust species are unknown.

“Part of my work is to make sure we have a worldwide scope on our research to look at where things can change. So we are trying to get a handle on where barberry is actually functioning as an alternate host because it is still a big question mark,” Fetch explains. “We’re trying to determine how important barberry is in generating new Puccinia races.”

In this work, he is collaborating with Yue Jin, a world expert on barberry infection with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Cereal Disease Laboratory. Jin has been collecting rust-infected barberry leaves from places like China, South America, central Asia and Africa, and he and his USDA colleague Les Szabo are determining which barberry species are alternate hosts for Puccinia species that infect cereal crops. It is complicated work because there are many different species of Puccinia, some that infect wheat and/or other cereal crops, and some that infect other grasses.

Fetch, Martinelli and Chaves have been surveying barberry species in Brazil for rust infections. “Initially, we are trying to determine if there is a functional barberry sexual cycle for wheat stem rust in South America. You can imagine a worst-case scenario – if Ug99 got to South America and there is a barberry alternate host for Ug99 to undergo sexual recombination and form other strains of Ug99,” Fetch says.

In late 2013, Sergio Bordignon, a Brazilian botanist, took the three researchers into the countryside to an area with many barberry bushes. “We started scouring the hillside looking at all these bushes, searching for rust infection. In one area that was in a low spot under some shade, the bushes were loaded with rust infection on the leaves. It was really exciting because as far as we knew it hadn’t been reported [that barberry in this region is acting as an alternate host for rust pathogens],” Fetch says.

The infected barberry plants are the species Berberis laurina. The researchers collected many leaf samples and examined the infections. Fortunately, the infections were not caused by Puccinia graminis or by Puccinia striiformis, which causes stripe rust.

The USDA Cereal Disease Laboratory is now working on identifying the rust species on the leaves. As well, Berberis laurina is being tested to see if it could act as an alternate host for cereal rust pathogens.

Fetch is hoping to expand the barberry surveys to other wheat-growing countries in South America. “For instance, there are barberry species in Uruguay and Argentina, but we don’t know whether or not those species have rust infection and, if they do, whether it is wheat stem rust or some other rust.”

Fetch summarizes, “So far, Ug99 has not come over to South America and we have not found a susceptible barberry that wheat stem rust can infect and have recombination on. That is good news for us in Canada.”

So, although the potential for widespread wheat stem rust epidemics in the Americas remains, wheat breeders still have some breathing room to develop resistant varieties.

Before you turn the ignition on another canola season, make sure the machines in your shed can get you from one destination to the next, and not just a stop or two along the way. John Deere equipment and services are a complete solution you can trust to get you from seeding, through application, and into harvest. Start your season off strong with a new 9R/9RT Series Tractor paired with precise air-seeding tools – combined they give you the power and productivity to set the stage for higher yields. Ensure your canola gets consistent application coverage, acre after acre, thanks to our impressive line of self-propelled sprayers. On the back end, get some of the best harvesting options in the business with a John Deere Windrower or S-Series Combine to pull as much revenue out of your feld as possible. Want to know the whole story? Visit Deere.ca/Ag for more information on the full John Deere suite of technology for high-performance canola production. Nothing Runs Like A Deere™.

by Carolyn King

Wheat growers now have great comparative data about which cultivars have the best resistance to the leaf spot complex and common root rot in Saskatchewan’s Brown soil zone. The data come from side-by-side trials at Swift Current to evaluate the disease responses of diverse cultivars of common wheat, durum, spelt and the khorasan wheat Kamut.

Although the study took place under organic conditions, the results are also useful for conventional and low-input production systems. No matter how wheat is grown, resistant cultivars are an important tool for dealing with these widespread and damaging diseases.

“I was interested in this research because of a gap in [disease resistance] information under organic and conventional systems, and because of an interest in assessing disease under organic conditions,” plant pathologist Myriam Fernandez — who led the three-year study — says.

“This study was the first of its kind in North America to provide

information on disease resistance and susceptibility in wheat cultivars under organic production. Most organic research on these diseases has been done in Europe on winter wheat,” Fernandez, who works with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at the Semiarid Prairie Agriculture Research Centre, notes.

However, even for conventional wheat production on the Prairies, such side-by-side varietal comparison data for these two diseases are not widely available. Fernandez explains, “We update the leaf spot ratings for wheat cultivars in Saskatchewan’s Varieties of Grain Crops publication every year. People who use that publication may think we grow all those cultivars together in the same field and the same year to assess relative reactions to these diseases, but there is no funding or other resources to do that. The data come from different years and different environments [so they are not as accurate as data from side-by-side comparisons]. We used to also provide common root rot ratings for that publication, but I had to stop this testing

ABOVE: The leaf spot complex is one of the most widespread wheat diseases on the Prairies.

Believe it or not, there’s a simple trick to protecting your canola yield before sclerotinia even becomes a problem –and you don’t have to be a magician. Based 100% in science, easy-to-use Proline® fungicide proactively protects your pro ts and continues to be the number one choice for canola growers looking for effective sclerotinia protection.

For more information, visit BayerCropScience.ca/Proline

[some years ago due to lack of funding].”

Varietal information on disease resistance is especially helpful for wheat growers who are looking for alternatives to chemical control of these fungal diseases. “Organic growers can’t use chemicals to control these diseases, and people who practice low-input agriculture would likely be reluctant to use chemical controls,” Fernandez notes.

“In conventional agriculture, it is relatively easy to control leaf spots with foliar fungicides, but chemical control of common root rot is not as easy,” Fernandez says. “A fungicidal seed treatment will protect the crop mostly from seedling blight, so it will help infected kernels to germinate, emerge and survive the first stages of growth. But root rot develops later on, and a seed treatment’s effect is not carried forward to later stages of plant growth.”

Growers have to rely on resistant cultivars and changes in agronomic practices, like crop rotation, to control common root rot.

As a result, both conventional and organic growers have to rely on resistant cultivars and changes in agronomic practices, like crop rotation, to control common root rot.

Fernandez explains that the leaf spot complex and common root rot can each have serious impacts on wheat yield and quality.

“The leaf spot complex is one of the most widespread wheat diseases on the Prairies and across Canada. It is called a ‘complex’ because several pathogens are responsible for it including: tan spot caused by Pyrenophora tritici-repentis; septoria leaf blotch complex caused by Phaeosphaeria nodorum, Mycosphaerella graminicola and Phaeosphaeria avenaria; and spot blotch caused by Cochliobolus sativus,” she says.

“Leaf spots can have a significant impact on yield when the flag leaf is moderately to severely infected. In addition, most of the pathogens that cause leaf spots can also infect the heads and kernels, causing problems like black-point and red smudge.

“For example, the pathogen that causes tan spot also causes red smudge, which is mostly a problem in durum. This pinkish discolouration of the kernels can cause serious economic losses because the tolerance for red smudge is very low in the top grades of durum, even though no harmful toxin is involved. Durum with 0.3 per cent red smudge is downgraded from No. 1 to No. 2.”

Common root rot and crown rot are found in most fields and most environments on the Prairies, where they are caused mainly by Cochliobolus sativus and various Fusarium species.

“Common root rot can cause a variety of problems in wheat,” Fernandez notes. “An infection at the seedling stage can cause seedling death and lack of germination and emergence, resulting in lower yields. In addition, a lot of the same Fusarium species that cause root and crown rot also cause Fusarium head blight [FHB]. In a dry year, they might not cause [FHB] but they can cause root rot and crown rot, likely at a higher level because of heat stress. So those pathogens infecting the roots and crowns will be there in the field as a reservoir, ready to cause [FHB] if wet conditions occur.”

In Saskatchewan, the main Fusarium pathogen causing FHB has been Fusarium avenaceum. This fungal species produces mycotoxins, although not deoxynivalenol (DON), which is produced by Fusarium graminearum, the predominant cause of FHB in most other regions.

Fusarium avenaceum is not only a problem in wheat. “This pathogen affects many other crops, including pulses, especially peas and also lentils, and oilseeds like canola and flax,” Fernandez says. “For example, when people practice a rotation of durum – which is more susceptible to Fusarium than common wheat – with peas, lentils or chickpeas, they increase the inoculum of Fusarium avenaceum in the field and then increase the chances of having FHB caused by this pathogen.”

According to Fernandez, Cochliobolus sativus appears to be increasing on the Prairies and in other regions of the world. She notes, “It causes root rot, crown rot, spot blotch on leaves and black-point, so it can infect the whole plant. It can also infect other crops, so crop rotation might not help to get rid of it; in fact, a rotation that also includes barley will cause the situation to get worse because barley is more susceptible than wheat to that pathogen.”

Common root rot can be more of a problem than the leaf spot complex. Not only is it harder to control with fungicides, but growers don’t always recognize that this disease is present in their wheat crop. Fernandez says, “People see the above-ground symptoms but they don’t necessarily realize [that the cause lies below-ground].”

Fernandez and her colleagues conducted the study from 2010 to 2012. It was funded by the former Canadian Wheat Board under its Organic Market Sector Development Initiative.

The 23 varieties in the study were chosen by an advisory council of organic producers, which was set up by Fernandez, and by the two organic wheat breeders involved in this study, Dr. Stephen Fox and Dr. Pierre Hucl. These varieties are the ones grown most often by organic wheat growers in the Brown soil zone of southwest Saskatchewan. The varieties include: 13 common wheat cultivars (AC Andrew, AC Barrie, AC Cadillac, AC Elsa, CDC Bounty, CDC Go, CDC Kernen, CDC Rama, Lillian, Red Fife, Stettler, Superb and Unity), six durum cultivars (AC Avonlea, CDC Verona, Enterprise, Kyle, Strongfield and Transcend), two spelt cultivars (CDC Origin and CDC Zorba), and Kamut.

As expected, there were differences in leaf spot resistance among the different species and cultivars. “Overall, for all cultivars, leaf spot severity was highest in 2010 and lowest in 2012. No cultivar had a consistently low level of leaf spot infection across all years,” Fernandez notes.

She summarizes the varietal results averaged over the three years. “For common wheat, the varieties most susceptible to leaf spot were AC Barrie, CDC Go, Superb and Unity. The ones with the lowest infection levels were AC Andrew, CDC Bounty and Lillian.”

Kyle was the most susceptible durum cultivar; there were no significant differences among the rest of the durum cultivars. Kamut’s response to leaf spot was similar to that for the common and durum wheats.

“For the two spelt cultivars, we found that CDC Zorba was the least susceptible. In fact, it was the least susceptible among all

Rocky Mountain Equipment has over 35 locations across the Canadian prairies to serve you. With the best people, products and services, you can depend on us to get what you need. Visit us at one of our CASE IH Dealerships today.

DEPENDABLE IS WHAT WE DO.

Delaro™ fungicide doesn’t take kindly to diseases like anthracnose, ascochyta and white mould threatening the yield potential of innocent pulse and soybean crops. Powerful, long-lasting disease control with exceptional yield protection, Delaro is setting a new standard in pulse and soybean crops.

review of new registrations and label updates for the 2015 growing season.

by Bruce Barker

Alook at the new seed treatments, foliar fungicides and label updates for 2015, with product information provided by the manufacturers.

Seed treatments

Vibrance Quattro seed treatment – Active ingredients: difenoconazole (Group 3), sedaxane (Group 4), metalaxyl-M (and S-isomer) (Group 7), fludioxonil (Group 12). Vibrance Quattro seed treatment is a novel seed care product that brings together four fungicide active ingredients to protect cereal crops against a wide range of seed- and soil-borne disease. For use on barley, oats, rye, triticale, winter wheat and spring wheat, Vibrance Quattro offers growers a convenient way to protect cereal seed and seedlings from seed rots caused by Fusarium, Pythium, Rhizoctonia, Penicllium and Aspergillus spp., as well as seedling blight, root rot and damping off. Its convenient, ready-to-apply formulation means Vibrance Quattro can be applied on-farm and does not require the use of a closed treating system.

Cruiser Vibrance Quattro seed treatment – Active ingredients: thiamethoxam (Group 4), difenoconazole (Group 3), sedaxane (Group 4), metalaxyl-M (and S-isomer) (Group 7), fludioxonil (Group 12). Cruiser Vibrance Quattro seed treatment is a complete seed care solution for western Canadian cereal growers, delivering control of a broad range of seed- and soil-borne diseases and insect pests. For use on barley, oats, rye, triticale, winter wheat and spring wheat, Cruiser Vibrance Quattro delivers Vigor Trigger and Rooting Power benefits for enhanced crop establishment, for a stronger, more vigorous cereal crop. Cruiser Vibrance Quattro may be applied by commercial seed treaters. It is also available in a convenient, pre-mix formulation that can be applied on-farm without the requirement of a closed system.

Helix Vibrance with Fortenza seed treatment – Active ingredients: cyantraniliprole (Group 28), thiamethoxam (Group 4), difenoconazole (Group 3), sedaxane (Group 4), metalaxyl-M (and S-isomer)

(Group 7), fludioxonil (Group 12). Helix Vibrance with Fortenza seed treatment is now available to canola growers who want to improve their insect control spectrum. Fortenza is a new seed-applied insecticide for early-season control of cutworm that contains the active ingredient cyantraniliprole – a different chemistry group from those found in many seed care products. The Helix Vibrance with Fortenza combination includes four fungicides and two insecticides, to help control a wide range of soil-borne diseases and insect pests, including cutworms, flea beetles, Rhizoctonia, Pythium and Fusarium. Fortenza is only available for purchase on pre-treated canola seed.

Delaro – Active ingredients: prothioconazole + trifloxystrobin (Groups 3 + 11). Delaro is a broad-spectrum fungicide for peas, lentils, chickpeas and soybeans to be released in Western Canada for the 2015 growing season. It delivers exceptional and long-lasting control of all major stem, pod and leaf diseases that challenge today’s pulse and soybean growers, including ascochyta, anthracnose, white and grey moulds, mycosphaerella blight, Asian soybean rust, frogeye leaf spot, brown spot and stem blight. It also provides suppression of charcoal rot in soybean. Delaro provides quick and long-lasting protection. Priaxor – Active ingredients: fluxapyroxad + pyraclostrobin (Groups 7 + 11). Combining the new active ingredient Xemium with the proven benefits of AgCelence, new Priaxor is a broad-spectrum, multiple mode-of-action fungicide for use on a wide range of crops. In addition to controlling key diseases such as blackleg in canola, anthracnose and ascochyta blight in lentils, and mycosphaerella blight and powdery mildew in field peas, Priaxor is also registered for use on chickpeas, fababeans, flax, soybeans, corn and more. Research shows

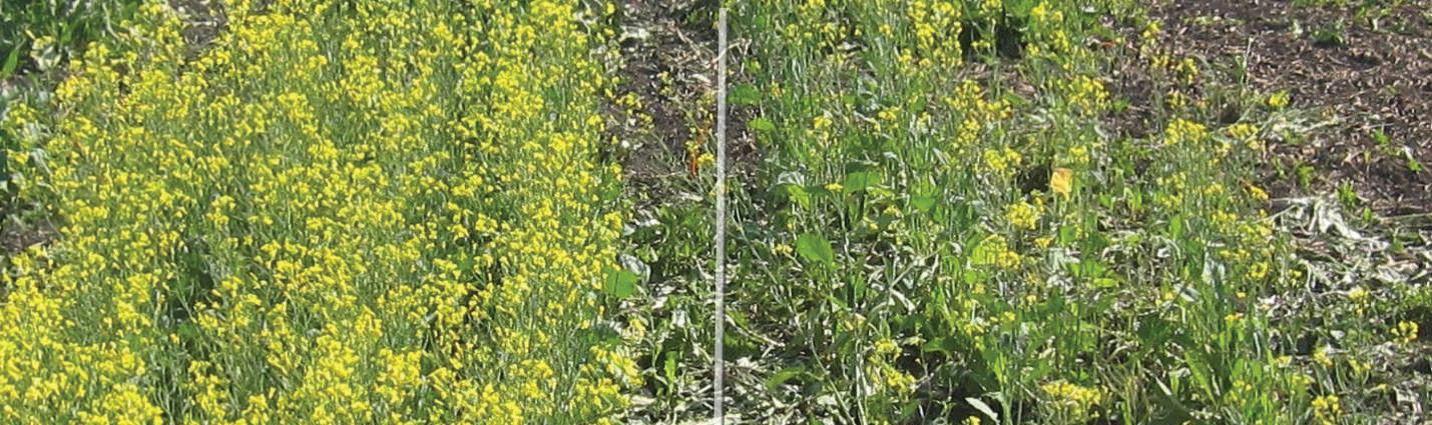

ABOVE: New fungicides and label updates are helping to control disease in lentils and many other crops.

the results Priaxor delivers include more consistent and continuous disease control, increased plant growth efficiency and better management of minor stress, all contributing to higher yield potential.

Acapela fungicide – Active ingredient: picoxystrobin Group 11. Acapela is now registered for control of stripe rust in cereal grains, net blotch in barley and anthracnose in lentils. Acapela fungicide is an advanced strobilurin fungicide for disease control in canola, cereals, corn, pulses (peas, lentils, chickpeas and dry beans) and soybeans. Acapela provides broad-spectrum disease control for key diseases like sclerotinia in canola; and leaf rust, powdery mildew, septoria leaf blotch, tan spot, mycosphaerella pinodes (peas), mycosphaerella blight and Asian soybean rust, and suppression of sclerotinia rot (white mould) in pulses and soybeans.

Quilt foliar fungicide – Active ingredients: azoxystrobin (Group 11), propiconazole (Group 3). Quilt foliar fungicide is now labelled to control blackleg infections in canola. Quilt can be applied during the rosette stage between the second true leaf and bolting (two to six leaf) to control blackleg. This broad-spectrum fungicide combines the power of two active ingredients, and together they deliver both systemic and curative properties, as well as provide resistance management. Quilt is particularly effective at controlling disease such as blackleg because of its ability to move within the plant, not only protecting the points of contact, but new plant material as it grows.

Bravo ZN foliar fungicide – Active ingredient: chlorothalonil (Group M-5). Bravo ZN foliar fungicide is now registered for use on pulses, offering growers a new option to control damaging foliar diseases. Bravo ZN is a dependable, broad-spectrum, contact fungicide that includes the unique WeatherStik technology, a patented

surfactant from Syngenta, which maximizes the product’s rainfastness. Quadris Top foliar fungicide – Active ingredients: azoxystrobin (Group 11), difenoconazole (Group 3). Quadris Top foliar fungicide label has been expanded to help potato growers suppress white mould infections. Quadris Top contains two powerful active ingredients and provides highly effective protection against target diseases. And, because of translaminar and xylem-systemic movement, Quadris Top protects better than a contact fungicide.

Propulse foliar fungicide – Active ingredients: fluopyram (Group 7), prothioconzale (Group 3). Propulse fungicide is now registered on fababean and for control of anthracnose in dry beans. Propulse provides unparalleled disease control with best-in-class protection against the most serious dry bean diseases, including white mould (sclerotinia) and ascochyta. With two modes of action, Propulse combines the new fluopyram (Group 7) with the proven defense of prothioconazole (Group 3), offering exceptional yields and unparalleled disease protection.

Rampart – Active ingredient: Mono- and dipotassium salts of phosphorous acid (Group 33). The Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) has now approved foliar and aerial application of Rampart for the suppression of late blight and pink rot in potatoes. The label expansion also includes downy mildew suppression in blackberries.

Folicur and Prosaro foliar fungicide sequential application. The Folicur and Prosaro labels have been updated to allow application of Folicur at the flag leaf followed by Prosaro at head timing. This sequential application is important in areas conducive for high and extended disease pressure. The first application helps protect against common leaf diseases while the second application extends protection against leaf diseases and Fusarium head blight.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 30

cultivars in the study,” Fernandez says.

Again as expected, the study found differences in common root rot resistance among the wheat species and cultivars. She notes, “We already knew that durum wheat was more susceptible than common wheat to root rot, but we didn’t have any information on spelt wheat or Kamut. We found that spelt was the most susceptible to root rot, followed by durum wheat and Kamut, with common wheat having the lowest average severity.”

The root rot results varied quite a bit from year to year. In spelt, CDC Origin had greater root rot severity than CDC Zorba. On average, among the durum cultivars, AC Avonlea, Kyle and Transcend had the highest severity and CDC Verona had the lowest. For common wheat, AC Elsa, CDC Kernen and Red Fife tended to be the most susceptible, and Superb and Unity tended to be the least susceptible.

Unfortunately, the cultivars with better resistance to one of the diseases didn’t necessarily have better resistance to the other. “For most cultivars there was no agreement in their reactions to both common root rots and leaf spots,” Fernandez notes. “For example, the three common wheat cultivars with lower root rot severity were

also three of the cultivars with the highest severity of leaf spotting.”

The study’s results can help organic and conventional wheat growers in the Brown soil zone of southwest Saskatchewan when deciding which cultivars to grow. The weather in the region during the study was wetter than the long-term average, so the results apply best to such conditions.

Because of those wetter conditions, the results may also have some application to the moister parts of the Prairies. “You could possibly extrapolate the study results to other areas, but you would have to be careful because there could be different relative prevalence of the wheat pathogens in other environments and other soil types,” Fernandez says.

The study results could also help breeders to develop new wheat varieties with better disease resistance.

Fernandez recently published two papers on this study in the Canadian Journal of Plant Sciences (available online, open access). If funds and other needed resources become available, she would like to continue this research on varietal resistance to these two diseases to build a dataset that covers a wider range of environmental conditions and soil types.

DISCOVER COMFORT, PRODUCTIVITY AND QUALITY FROM THE WORLD’S MOST POWERFUL COMBINE.

COMFORT. All-new Harvest Suite™ Ultra cab with 68 ft2 glass and acres of space for unsurpassed visibility and operating ergonomy. Smooth ride SmartTrax™ system with Terraglide™ suspension.

PRODUCTIVITY Largest ever 410 bu. grain tank, 4 bu./sec unloading speed, 34 ft. pivoting auger for greater unloading flexibility.

QUALITY. Unique Twin Rotor™ threshing system, 10% higher capacity with Twin Pitch technology, crop accelerating Dynamic Feed Roll™ for even higher throughput.

POWER. Mighty Cursor 16 ECOBlue™ HI-eSCR engines for Tier 4B compliance and 10% fuel savings. Up to 653 hp on the new CR10.90, the world’s most powerful combine.

www.newcr.newholland.com

An update on its spread and efforts to manage this troublesome corn disease.

by Carolyn King

Goss’s wilt has been in Western Canada for only a few years, but plant pathologists, agronomists and breeders are already working to learn more about this corn disease and enhance management options for Prairie growers.

Goss’s wilt is caused by the bacterium Clavibacter michiganensis subspecies nebraskensis. “The bacteria overwinter on infected stubble, so the disease is a concern in fields with shorter corn rotations. But even in fields with longer rotations, it can be a problem because corn stubble is very mobile in the fall, blowing across the roadways and carrying the disease to new fields,” Holly Derksen, field crop pathologist with Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Development (MAFRD), says.

The disease usually occurs in a non-systemic form in which the pathogen infects the plant’s foliage. “The bacterium enters the plant through a wound from hail or wind or sand blasting,” Wilt Billing, DuPont Pioneer’s area agronomist for central and eastern Manitoba, explains. “The infection usually appears on the upper canopy at first. Then with high humidity and rain splash, the disease moves very rapidly throughout the plant, usually from the top down.”

The disease also has a systemic form where the bacteria infect the corn plant’s vascular tissues. However, Billing and Derksen have not seen the systemic form in commercial corn fields in Manitoba.

A relatively new disease, Goss’s wilt was first identified in Nebraska in 1969. In the 1970s and early 1980s, the disease spread through Nebraska and into some surrounding states. Then very little disease occurred until about 2006 when Goss’s wilt resurged and began spreading into new areas.

Billing notes, “Goss’s is continuing to expand. In the U.S. it has moved right across most of the Corn Belt as far south as Louisiana. It moved into the southwestern edge of Michigan, so it has moved east of the Mississippi River.”

In Western Canada, the disease was first found in Manitoba in 2009 and in Alberta in 2013.

DuPont Pioneer has been conducting Goss’s wilt surveys in Manitoba for several years, evaluating all commercially available hybrids (the surveys didn’t target other companies’ products, but if growers had products from multiple companies, then the other hybrids were also included in the surveys). “In Manitoba over the past five or six years, we’ve seen anything from an insignificant

infection which doesn’t have any yield loss all the way up to the most severe fields experiencing close to 50 to 60 per cent yield loss. So it can be very impactful,” Billing says. The severity of the disease depends on weather conditions, the amount of inoculum in the field and the susceptibility of the hybrid to Goss’s wilt.

Fortunately, late summer conditions in Manitoba in 2014 didn’t favour the disease. Billing says, “In 2014, we found the disease in many fields in mid to late July. However, we had a dry spell during late July to early August, so the disease was really limited in its impact.”

In 2014, Derksen and Morgan Cott from the Manitoba Corn

Take charge of your resistance concerns by making Liberty® herbicide a regular part of your canola rotation. As the only Group 10 in canola, Liberty combines powerful weed control with effective resistance management to help protect the future of your farm.

To learn more, visit: BayerCropScience.ca/Liberty

Growers Association (MCGA) conducted a survey for Goss’s wilt across Manitoba’s corn-growing region between September 19 and October 7. “In the past, the only surveys for Goss’s wilt in Manitoba were carried out by different companies,” Derksen says. “We wanted to conduct a third-party survey to get representation of all the corn acres.” This was their first Goss’s wilt survey; the plan is to do a provincial survey every year.