TOP CROP MANAGER

ASSESSING STARTER FERTILIZER FOR PULSES

Does applying more compensate for low fertile soils?

PG. 4

BREEDING FOR RESISTANCE

Aphanomyces research update

PG. 6

LENTIL MARKET OUTLOOK

More diversity on the horizon

PG. 12

Does applying more compensate for low fertile soils?

PG. 4

Aphanomyces research update

PG. 6

More diversity on the horizon

PG. 12

Get a more complete and faster burnoff when adding Aim® EC herbicide to your glyphosate. This unique Group 14 chemistry delivers fast-acting control of your toughest weeds. Aim® EC herbicide also provides the ultimate flexibility, allowing you to tank mix with your partner of choice before planting virtually any major crop. Fire up your pre-seed burnoff with Aim® EC herbicide.

Ace Resistant Weeds by mixing Aim® EC with Express® brands and/or Command® 360 ME – receive up to $5.50/ac back.

JANUARY 2020 • TOP CROP MANAGER WEST

FERTILITY AND NUTRIENTS

4 Assessing starter fertilizer for pulses

by Bruce Barker

PESTS AND DISEASES

6 Aphanomyces in lentil: breeding for resistance

by Julienne Isaacs

WEED MANAGEMENT

10 Herbicide-resistant kochia tumbling across the Prairies

by Bruce Barker

MARKETS

12 Lentil market outlook: keeping an eye on India by Julienne Issacs

Top Crop Manager thanks FMC Canada for sponsoring this special edition.

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

Despite their small footprint (in both physical size and acres grown), lentils pack a big punch for producers and consumers alike. They’re a nitrogen-fixing crop that can perform well in rotation to help improve soil health. And, along with other pulses and legumes, lentils are a great source of protein, fibre and other key nutrients (and thanks to some creative recipe developers and food bloggers, they can be included in almost any recipe – lentil-banana muffins, anyone?).

The little crop that could has been recognized for its other merits, too –even overseas. A recent article in the Globe and Mail interviewed Dr. Judit Smits, a veterinary medicine professor at the University of Calgary. Smits and her husband, Dr. Albert Vandenberg, a plant sciences professor at the University of Saskatchewan, are part of a Canadian team of researchers using lentils grown in Saskatchewan to help combat arsenic poisoning in humans. The research began when Smits found she could treat animals suffering from selenium poisoning with safe forms of arsenic, and wondered if the detoxification method could be reversed. Selenium is abundant in the soil where lentils – the same ones that Vandenberg was studying in Saskatchewan – grow. The couple, along with postdoctoral fellow Regina Krohn, studied the effects on mice before trialling their research in Bangladesh in 2015 and 2016. High levels of arsenic are found in the country’s drinking water – and coincidentally, lentils are a popular food. Four hundred Bangladeshis were provided with Saskatchewan-grown lentils to eat, and the researchers found the trial participants had an increased body mass index and lower incidences of asthma and allergies after eating the lentils. But perhaps most notable, according to Smits in the Globe and Mail article, was that higher levels of arsenic were found in urine samples, meaning the lentils were helping to flush out the toxin before it was absorbed.

MANAGER

Published as part of Top Crop Manager, January 2020, by: Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. PO Box 530, 105 Donly Drive South, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 Canada Tel: (519) 429-3966 Fax: (519) 429-3094

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE Stefanie Croley

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Stephanie Gordon

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Alex Barnard

WESTERN FIELD EDITOR Bruce Barker

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Michelle Allison

VP PRODUCTION/GROUP PUBLISHER Diane Kleer

Canada’s original technical crop production magazine, The Western edition of Top Crop Manager, is published nine times a year. To be sure of your copies, either mail, fax or e-mail your name and full postal address to Top Crop Manager, or subscribe at topcropmanager.com. There is no charge for qualified readers.

We have a long way to go before saving the world with lentils, but the Canadian research and advancements made so far are a great start. Like any crop, lentil production comes with its own set of challenges: herbicideresistant kochia and aphanomyces root rot are two that you’ll read about in these pages. What’s more, market outlook and trade issues are a current concern for Canadian producers – and a particularly big concern at that, as Canada is the world’s leading exporter of lentils (and one of three largest producers of the crop, alongside India and Turkey). But as you’ll see in this special edition, the future of Canadian lentil production is bright, with thanks to work being done by scientists and industry in our own backyards.

@TopCropMag

/topcropmanager

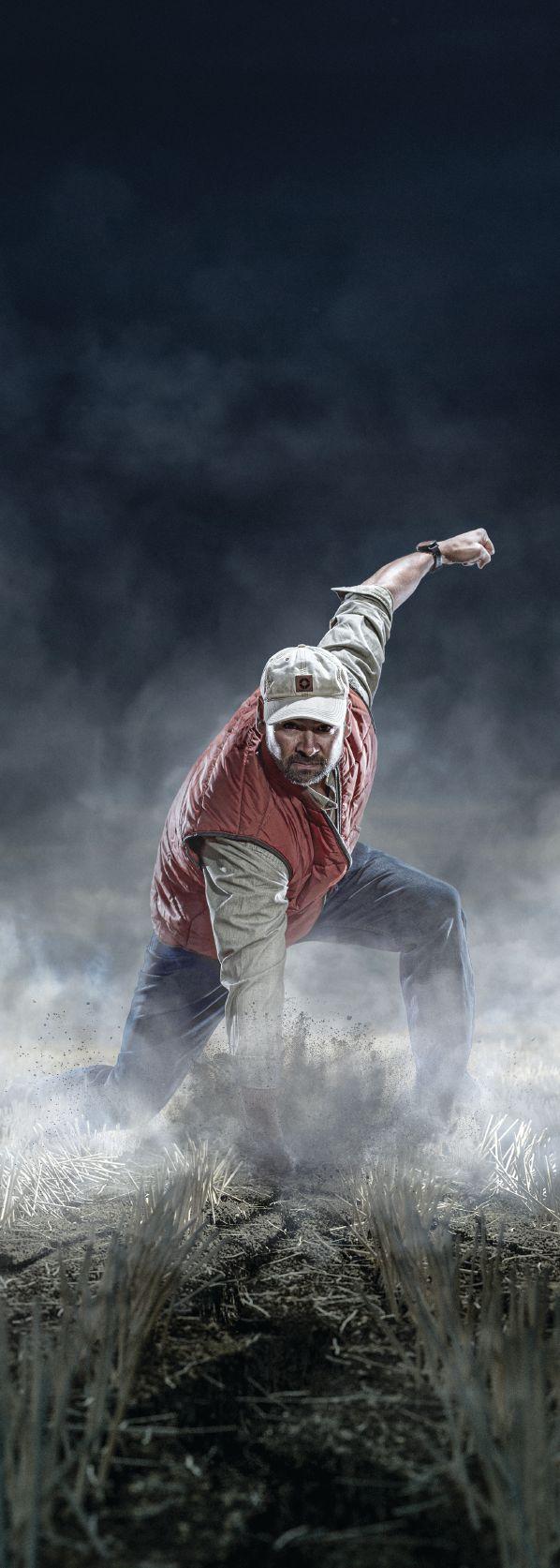

ON THE COVER:

Lentils have been grown in Canada since the 1970s, and now the country is one of the world’s top producers. Photo courtesy of Ti Zhang.

Does applying more help compensate for low fertile soils?

by Bruce Barker

On low fertility soils, growers often wonder if starter fertilizer would provide a benefit to pulse crops. Research at the University of Saskatchewan’s soil science department looked into crop safety and the response of pulse crops to starter nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and sulfur (S) fertilizers. Generally, there was little crop response to starter fertilizer.

“Safe seedrow rates for phosphorus and potash have been established for pulses, but tolerance and response to starter blends containing a higher analysis of N along with phosphorus and sulfur was not known,” says Jeff Schoenau, professor of soil fertility at the University of Saskatchewan. “We wanted to look at some of the common starter blends and products to see if there would be a crop response.”

Schoenau, along with colleague Tom King, supervised the research conducted by Harshini Galpottage Dona for her master of science thesis. Galpottage Dona conducted both greenhouse and field trials.

In the greenhouse trial, she collected soil from a loamy textured Brown Chernozem field in southern Saskatchewan. Soybean, green pea, fababean, black bean, small red lentil and desi

chickpea were seeded into the soil with a simulated 15 per cent seedbed utilization (1.5-inch opener on 10-inch row spacing) and grown for 30 days under greenhouse conditions.

Four starter N rates of zero, 10, 20 and 30 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare (kg N/ha) were applied for seven different fertilizer blends/products: monoammonium phosphate (MAP; 11-52-0) alone, MAP plus urea (28-26-0), MAP plus AS (16-260-12), and four composite granular fertilizers including MES-15 (13-33-0-15), Koch 12-45-0-05, Simplot 16-20-0-13, and Anuvia Symtrx 16-20-0-12.

The amount of nutrients applied varied by product/blend. For example, a 10 kg/ha N rate applied as MAP (11-52-0) would have resulted in 47.3 kg P2O5/ha also being applied with the seed. Conversely, the same 10 kg N rate in a blend of urea and MAP (28-260) would have resulted in only 9.3 kg P2O5/ha applied.

Overall, the six legume crops showed the following relative

Continued on page 14

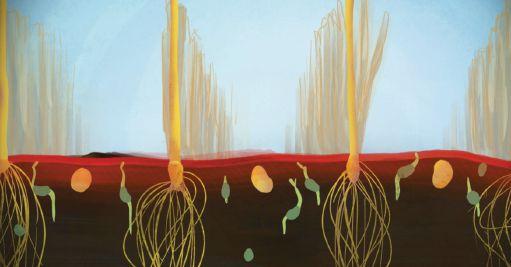

ABOVE: A 10 kg N/ha starter blend in the seedrow was sufficient for fababean, pea, lentil and chickpea.

You can spray Focus herbicide early knowing your crop is protected by a soil-based barrier waiting to be activated.

Focus herbicide helps protect your lentil crop in two ways:

• When added to glyphosate, it can speed up the control of emerged weeds

• It creates a soil-based barrier for extended weed control of emerging weeds

Rachel Evans, technical sales manager for FMC, says that one of the main questions she gets is, “how does Focus work?”.

Rain pushes the product from the soil surface down into the soil pore space, the spaces between soil particles. It’s in between those particles that soil moisture sits, waiting to be drawn in by weeds as they germinate. “From there it’s a solution of water and Focus herbicide that is drawn up into germinating weeds,” says Evans.

And, you don’t need to worry about the product sitting and waiting to do its job. Since Focus herbicide is very stable, it doesn’t breakdown quickly with sunlight or turn into a gas and dissipate. It doesn’t bind to crop residue on the soil surface either, so you can maintain that important ground cover and leave the soil undisturbed.

Hope for resistance traits in wild relatives.

by Julienne Isaacs

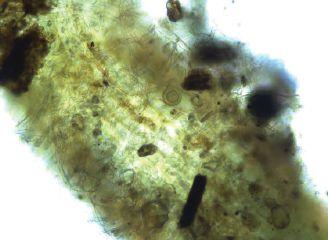

Aphanomyces root rot is caused by a soilborne pathogen, Aphanomyces euteiches , that is hard to detect and whose presence in a field is difficult to predict.

But the effects of this tricky pathogen on lentil can be severe, and management is difficult due to the pathogen’s ability to survive in fields for long periods without host plants. A. euteiches was confirmed in the Prairies only a few years ago, but it has likely been here longer, according to Sabine Banniza, a professor of plant pathology at the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre (CDC).

She says producers in some areas of the Prairies have long struggled with root rot in their pulse crops without being able to pinpoint the exact source of the problem, but it’s possible aphanomyces has been present in Western Canada for many years.

“Identification of this pathogen from infected roots is not easy compared to other pathogens,” Banniza says. “There’s at least one other fungal pathogen that looks similar, so to confirm

that it is aphanomyces root rot you have to use a molecular test.”

With the CDC’s Tom Warkentin and Bert Vandenberg, Banniza just completed a project on aphanomyces root rot (ARR) in lentil and pea.

Funded by Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, the project’s goals were to identify pathotypes of western Canadian isolates of the pathogen, screen lentil and pea lines from around the world to find sources of ARR resistance, and finally to create a breeding platform to develop new varieties of pea and lentil with ARR resistance.

Because ARR has been a recognized pathogen of pea in fields in the Pacific Northwest and in France for several decades, and of lentil since 2010, Banniza’s team worked with French and U.S. researchers to screen pea and lentil germplasm for resistance.

They found that Canadian field isolates of the ARR pathogen

ABOVE: Healthy lentil roots (left) and roots affected by root rot (right).

were far more virulent than U.S. isolates; as a result, lentil germplasm identified as having good partial resistance in the U.S. was susceptible to the disease when exposed to Saskatchewan’s more harmful isolates, Banniza says.

“Because we have, over the last two decades, worked with wild lentil species and found a fair amount of resistance to other diseases, we decided to systematically screen lentil’s wild relatives for resistance to ARR,” she explains.

One species of wild lentil in particular stands out, Banniza says, and it’s this species that will likely take a starring role when it comes time to make crosses.

Saskatchewan’s Agricultural Development Fund has funded the next stage of the research, which will see Banniza’s team developing molecular markers for screening lentil lines. Markers have already been developed for pea by French collaborators, but they don’t yet exist for lentil, she says.

They’ll screen germplasm not only for ARR resistance but for Fusarium resistance. Fusarium infection often occurs in tandem with ARR, and according to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada pathologist Syama Chatterton, the most severe symptoms and crop yellowing show up when both diseases are present.

But the development of new lentil lines with improved disease resistance is a long time from realization, Banniza says. It might be another decade before these lines are in the field.

While the CDC’s lentil breeding program is the only one of its kind in Canada, other research is ongoing that will help producers with management.

Chatterton began conducting ARR surveys five years ago. A major part of her program involves determining the threshold inoculum dose in the soil that changes its status from “healthy” to “diseased.” In time, Chatterton’s team hopes

to develop a soil risk analysis tool to help speed diagnosis. They’re also doing field trials – primarily with pea – assessing the effectiveness of seed treatments and a range of agronomic practices in controlling ARR in the field.

Chatterton says severity in the field varies dramatically year-to-year, largely depending on moisture levels. ARR has less of an impact in dry years. In 2017, a fairly dry year in Saskatchewan, disease incidence sat at about 26 per cent. But in 2016, incidence was at 60 per cent.

“When we look at disease severity, we rate on a scale of one to seven, with seven being dead. We would say we’re reaching an economic threshold of severity when we’re above a three,” she says. “On average across the Prairies, the disease severity for lentils is between around two to three in dry years, and in the wet years the average disease severity is higher at three to four.”

Currently, there’s only one seed treatment registered in Canada against aphanomyces in lentil – Ethaboxam (Group 22), trade name Intego Solo, but it’s only registered as early-season suppression, and Chatterton says it won’t be effective in heavily infested fields.

The most effective management tool against ARR is rotation. Chatterton says producers with ARR issues should rotate those fields away from susceptible pulses (pea and lentil) for at least six to eight years.

There’s little data on how long exactly the inoculum can thrive in a field. Chatterton points to one paper published in the 1990s that claimed the half-life of resting spores was about a year. “The researchers did some calculations to find that it would take about six to eight years

to reduce resting spores below threshold levels,” she says.

Her team is two years into a study looking at the effect of alternate pulse crops on inoculum levels in the soil. It’s too early to make conclusive statements, but so far they haven’t seen those crops support aphanomyces growth.

Chatterton says producers should keep track of disease incidence and severity by field.

“Farmers need to be aware of how their crop did the last time they planted peas or lentils, keeping track of small yellow patches and noticing low spots where the disease usually starts. That can be difficult to keep track of, and that’s why we want to move toward a soil risk analysis system so we can take some of the guesswork out of root rot risk,” she says.

Growing lentils isn’t often much like caring for Holsteins but both cash crop and dairy farms thrive under a long-term plan.

“Take care of your cows and they’ll take care of you,” Kevin Krahn’s dad used to say when Kevin and his wife Sherry took over the family’s purebred dairy operation in 1988. Now they grow peas, lentils, durum, some barley and canola. The wisdom from Kevin’s dad transferred into cash cropping after they sold the cows.

“I think the same thing applies to the land,” says Krahn from his farm near Swift Current. “We try to make decisions based on the long-term health of each field just like we did with the cows.”

Krahn, Sherry and hired man work on the operation. They do the majority of scouting themselves, although they hire an agronomist for advice on fertilizer rates and on which weed control and fungicide products to use.

The variability in weather patterns will always be the hardest component to manage in farming. The last two springs have been drier on Krahn’s farm. “We had some rain that came just in time this past year,” he says. “In 2018 we were very dry, in 2017 we were a little dry and in 2016 we were extremely wet.”

Through all the years – wet, dry and “normal” – his attitude has stayed the same. Krahn says he will continue to do what’s best for each piece of land. He might seed a little more spring wheat or seed a new pulse crop as an experiment but otherwise he sticks to the long-term plan.

“I’m kind of set in my ways,” Krahn says with a chuckle. “I do what’s best for the dirt, not what’s a fad. That’s not going to change. I could give you the rotation on 80 per cent of our farm for the next three years.”

The one area that Krahn is willing to experiment is in technology. They recently upgraded their sprayer and he tested out a new combine with significantly more automated features than his current combine.

For Krahn, taking care of the land means sticking with

his crop and chemical rotation. “We don’t really ever plant according to where we feel the markets are going,” he says. “We stick to the plan. It’s not just for the sake of managing pests but also to keep a diverse chemical rotation as well.”

Some tougher, less predictable weather years make it tempting to drop lentils from the rotation. And weed control options are limited when growing large green conventional lentils, says Krahn. He says their main weed pressures are wild oats, kochia, wild buckwheat and narrow-leaved hawk’s beard.

Four years ago, Krahn started using Focus® herbicide from FMC.

“It’s more reliable in different weather patterns,” he says. “But the main reason we like Focus is its ability to control weeds.”

“Lentils are a poor competitor when it comes to weeds,” says Rachel Evans, technical sales manager at FMC. “There needs to be a whole farm weed management strategy if lentils are in the rotation.”

For instance, part of the weed control strategy could include increasing seeding rates. Research by Dr. Steve Shirtliffe at the University of Saskatchewan showed that higher seeding rates up to 240 plants per square metre reduced weed populations and increased yield.

“Increasing seeding rates means you’ll have a more competitive crop and have more plants competing with weeds for resources,” says Evans. “And, you’ll also get better performance out of your herbicide.”

Resistant weeds, such as Group 1- and Group 2-resistant wild oats, are limiting the number of effective weed control products in a grower’s rotation. Evans says that Focus herbicide, made up of Groups 14 and 15, provides alternative modes of action to hit those problematic weeds.

Jesse Entz is from the B Creek Farming colony near Swift Current. Kochia is one of the biggest problem weeds the colony faces in lentils. They use Focus herbicide to suppress wild oats, which are becoming a problem as Group 1 resistance grows. “But the biggest reason we use it is for kochia,” he says. “There wasn’t much we could do for kochia in lentils before Focus.”

“The first year we put some down early on about 500

acres,” says Entz. They usually grow in the neighbourhood of 3,400 acres of lentils. “It was ready and activated when we needed the control in the spring.”

The colony had a lot of lentils flooded out in 2019. But even with the rain they still saw good weed control. Part of keeping a long-term plan involves spreading out weed control risk.

For instance, an early application allows Entz to sleep at night knowing his herbicide is already down even before seeding. He can concentrate on seeding and count on Focus herbicide and the protective layer it forms to protect his crop.

Managing weeds early also means more effective in-crop control, helping to avoid harvest challenges.

Research at the University of Saskatchewan found that lentils have a long critical weed-free period. The critical weed-free period is described as the stage of crop development where a yield loss of more than five per cent would occur if the crop were not weed free. In lentils, the crop needs to be weed free from the five-node stage right through to the 10-node stage.

“It’s quite a length of time, which shows you how uncompetitive lentils are,” says Evans. “It’s important to keep that critical weed-free period in mind as growers consider the timing of their herbicide applications and as they consider extended weed control products.”

Once again, planning and an eye on the long-term is key to growing a clean crop of lentils.

Having a long-term crop rotation plan and a strategy that incorporates tank-mixes and herbicide layering is a great way to manage herbicide resistance.

Hitting the same weeds at the same time using the same modes of action creates a pressure that can result in a change in weed population (where the population shifts to a majority of resistant individuals), or a change within weeds where they adapt and become resistant. Either way you’re training weeds to win.

Herbicide layering is the practice of using multiple herbicide groups and active ingredients at different application timings to control the same resistance-prone weeds. Using products with different modes of action is good and hitting weeds at different timings is even better.

For example, a pre-emergent product like Focus herbicide brings two modes of action – Group 14 and 15 to manage kochia. When combined with glyphosate, the Group 14 and Group 9 give you activity on any emerged, resistant kochia. Then, since kochia is a flushing weed, the group 15 portion provides activity on resistant kochia that’s germinating or about to emerge.

“[In herbicide layering], you are incorporating products at different timings that work on different weeds to achieve an overall higher level of weed control,” says Evans.

PRODUCT QUICK FACTS

Groups: 14 & 15

Rates: 33 or 40 acres per jug

Packaging: 4 x 4.5 L jugs per case

Activation: 15 to 25 mm (min 1/2 inch) of rainfall required Can be tank-mixed with glyphosate

Grassy weeds:

• Barnyard grass

• Downy brome

• Green foxtail

• Japanese brome

• Yellow foxtail

• Foxtail barley†

• Wild oats†

Broadleaf weeds:

• Cleavers

• Redroot pigweed

• Kochia†

• Lamb’s-quarters†

• Wild buckwheat†

• Wild mustard†

• Stinkweed†

Double and triple resistance is growing.

by Bruce Barker

The statistics on herbicide-resistant kochia are staggering. First Group 2, then Group 9, and finally Group 4 resistance was confirmed, along with double and triple resistance to those herbicide groups. Not only are the types of resistance increasing, but the percentage of the populations that are resistant to these herbicides is growing rapidly across the Prairies too.

“One of the projects that we are involved with, along with collaborators from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon, is the kochia weed resistance survey. The surveys give us the baseline numbers to see how herbicide resistance is growing,” says Charles Geddes, research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta. “When we look back at Group 2 resistance in the 1980s, within 20 years essentially all the populations became resistant. We’re seeing the same trend with Group 9 glyphosate resistance, and may also see it with Group 4 herbicides.”

The surveys are staggered by province every five years. For example, Alberta was surveyed in 2012, and more recently in 2017. Manitoba was surveyed in 2018 and Saskatchewan in 2019. Seed from approximately 300 populations are collected in a province after harvest and sent to AAFC. The collected seeds are grown in a greenhouse, and then screened for control by various herbicides.

The most recent results came out of the 2018 Manitoba survey where 297 populations were collected and screened. All populations were considered resistant to Group 2 herbicides, and, in addition, 59 per cent were resistant to Group 9 glyphosate. In the last Manitoba survey in 2013, only one per cent of populations were resistant to Group 9.

“That rapid growth is staggering, but we shouldn’t be too surprised. There was a similar trend in Alberta where glyphosate resistance went from five per cent in 2012 to 50 per cent of kochia populations in 2017,” Geddes says.

The 2018 Manitoba survey results for Group 4 dicamba resistance haven’t been released yet, but Geddes wouldn’t be surprised if a small percentage of the populations are confirmed Group 4 resistant. As more Roundup Ready Xtend soybeans (tolerant to glyphosate and dicamba) enter the market, this will put additional selection pressure on Group 4 dicamba resistance.

The 2012 Alberta survey found five per cent of kochia populations resistant to the combination of Group 2 herbicides and Group 9 glyphosate, and 100 per cent Group 2 resistance. Years later, the 2017 Alberta survey found 100 per cent Group 2 resistance, 50 per cent Group 9, and 18 per cent Group 4 dicamba resistant, and of

In-crop herbicide-resistant kochia control in lentil is extremely limited.

these, 10 per cent were three-way resistant. More kochia populations were becoming resistant to Group 2, 4 and 9 herbicides, or a combination of two, and a smaller percent were becoming triplethreats: resistant to all three. Saskatchewan’s 2019 survey results won’t be available until later 2020.

In the past, AAFC also tested kochia plants that were submitted by farmers and agronomists to test for suspected resistance. In 2020, Geddes will continue to offer this service for dicamba and fluroxypyr (Group 4) resistance. Saskatchewan Ministry of Agri-

culture’s Crop Protection Lab will begin screening kochia for glyphosate resistance, in addition to the testing offered by the Manitoba Pest Surveillance Initiative.

On-going research into solutions Geddes and his colleagues are working on several different projects to help manage the development of kochia herbicide resistance. One area that needs work is whether cross-resistance exists within the Group 4 synthetic auxins. Within Group 4, four families exist including benzoic acids, carboxylic acids, picolinic acid, and phenoxies. He says that one especially important active ingredient used as the foundation in many herbicides for kochia control in cereals is fluroxypyr (carboxylic acid).

“Fluroxypyr, in general, is very good for management of susceptible kochia but we have seen some cross-resistance to it and dicamba. But we’ve also seen resistance to one and not the other,” Geddes says. “We’re not sure what is going on with the crossresistance, or lack of, but it has something to do with the mechanism of resistance, which we need to better understand.”

Geddes says kochia management will increasingly rely on integrated weed management (IWM). Chemical control is part of IWM. The best practices for managing herbicide resistance are a frequent rotation of herbicide groups, plus applying tankmixes of two or more herbicide groups. This also includes herbicide layering of a pre-emergent and post-emergent herbicide from different groups.

The provincial guides to crop protection provide herbicide recommendations for non-resistant kochia control for pre-seed, in-crop, and post-harvest applications. Top Crop Manager magazine produces

an annual poster guide for herbicides to control resistant kochia including Group 2, 2+4, 2+9 and 2+4+9 resistant populations. The kochia poster is released alongside the March issue.

Other IWM practices include cultural weed management to help grow more competitive crops and patch management. Geddes is currently researching the interaction of row spacing, seeding density and crop rotation on glyphosate-resistant kochia control with typical kochia herbicides. Also included is a more diverse crop rotation of spring wheat-Clearfield lentilspring wheat-Liberty Link canola.

“The idea is to try to improve the crop’s competitive ability and to reduce the amount of seed returning to the seedbank,” Geddes says.

The majority of kochia seed only survive one to two years in the soil. Integrated weed management tries to capitalize on that by trying to achieve better kochia control to reduce the size of the seedbank.

Research by former Saskatoon AAFC research scientist Hugh Beckie found that the time for viable kochia seed to drop to 10 per cent viability in the soil was 235 days, and no difference was found between surface, 2.5 centimetre (cm) and 10 cm depths. However the challenge in trying to manage the seedbank is that one kochia plant can produce about 30,000 seeds per plant. Even if only one per cent of the seeds survive, 300 seeds may remain viable from that one plant after several years.

“We need to better understand the source of the viable seeds in the seedbank because there still seems to be some seeds that can survive and come back to haunt us,” Geddes says.

Patch management of kochia is also important. Controlling herbicide escapes by tillage or herbicide application, or other methods such as mowing, will help limit the spread. Geddes is looking at harvest timing to determine when kochia patches might have time to regrow and set seed after harvest. He is also looking at pre- and post-harvest applications of glyphosate plus saflufenacil (Group 14) to help manage patches and seed production after harvest.

“The results are quite preliminary, but it appears that if harvest is early with a winter cereal, or perhaps field pea or lentil, kochia has the resources to regrow and set seed. In that case a post-harvest application or other patch management strategy would be required,” Geddes says. “If harvest is moving into later September, control might not be needed.”

Geddes also adds a final caution for farmers using pre-seed burndown herbicides. With the increase of glyphosateresistant kochia, farmers have correctly looked to other herbicide groups for preseed control. The Group 14 herbicides, including carfentrazone (Aim), flumioxan (Valtera), saflufenacil (Heat) and sulfentrazone (Authority), generally work well on kochia, but Geddes sees many farmers relying on only those herbicides for preseed burndown.

“That’s risky, using only one mode of action. My advice is don’t rely on just a Group 14. That’s essentially doing the same thing we did with glyphosate. With continued selection pressure on Group 14 herbicides, I think that’s where we’ll see the next resistance problem if we don’t use multiple modes of action,” Geddes says.

Goals for more diversity in trade and end-use markets will keep pulses in the rotation.

by Julienne Issacs

India is the world’s largest producer of pulses, but Canada is the world’s top pulse exporter, with India its top pulse buyer. The two nations inevitably must perform a delicate dance when it comes to trade relations.

In the 2016-2017 crop year, that relationship took an unexpected turn. India began imposing trade restrictions – both tariffs and quantitative restrictions – on peas and lentils, and added technical requirements for methyl bromide fumigation of shipments prior to their arrival in India.

As a result, Canadian pulse exports to India decreased by more than 80 per cent during the 2017-2018 crop year, says Mac Ross, director of Market Access and Trade Policy for Pulse Canada.

“That’s reverberated throughout the entire value chain and that was the big change that we saw from the 2016-17 year to the 2018 crop year. In 2018-2019 we’ve seen an increase in exports of lentils back to India, but peas are nowhere near the levels we were at in the past,” he says. According to Statistics Canada, 737,000 metric tonnes of lentils were exported to India in 2018-2019.

The reason for India’s restrictions on imports, Ross says, is that India is aiming for self-sufficiency in pulse production as part of a

mandate to double farmers’ income by 2022. “India’s farmers represent a significant portion of its population and increasing farmers’ welfare is a top priority for the Indian government,” he says.

“In order to help raise domestic prices and increase pulse production, we have seen steady increases in the minimum support prices offered to Indian farmers and increases in restrictive import policy measures. They had two record years of pulse production moving into 2017, and that’s when they began to put these barriers on,” he says.

The situation is worst for peas: there’s a 50 per cent tariff and quantitative import restriction on peas. Lentils face a 33 per cent tariff but no quantitative restriction, Ross says.

But that’s not to say the lentil situation is straightforward. India recently added 26 weed species to its weed seed quarantine list without offering advance notification to export countries. This has resulted in “increased unpredictability” for lentil shipments clearing in India, he says.

ABOVE: Canada exported more than two million tonnes of lentils last year, with more than a quarter of the total volume going to India.

Despite this, Marlene Boersch, a partner at Winnipeg-based Mercantile Consulting Venture Inc., says Canada had a fairly good year in terms of lentil exports, with just over two million tonnes exported, and 550,000 tonnes – more than a quarter – of the total volume going to India.

Canada had been sitting on a very large carryout in 2017-2018, with an ending stock of around 650,000 tonnes in 2018. Ending stock is projected to be around 500,000 tonnes the end of 2019. The good year will further reduce that carryout and restore normal supply/demand, Boersch says.

After India, Canada’s top lentil buyers are Turkey, Bangladesh, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt, Boersch explains. She predicts that despite ongoing restrictions from India, Canada’s lentil exports will remain steady or increase.

Turkey and Australia are Canada’s top competitors in red lentil exports, followed by Eastern European nations; in green lentils, our top competitors are the U.S. and, increasingly, Russia and Kazakhstan. To some extent, Canada’s export volumes are influenced by how well the crop performs in these nations.

But overall, Boersch says lentils are a relatively safe bet. “Pulses and lentils have been a very good crop for all intents and purposes. In spite of the problems

with some protectionism in India, we’ve still had very good volumes traded over the last two years,” she says.

“We’ve had to work very hard to work down the excess production, and when you look at overall lentil production in the world, the overall production of lentils has reduced a little bit from that peak in 2016-17, so we’re getting much more into a balanced market,” she adds.

If India is short on pigeon pea and lentils this year, that market might open up a bit, Boersch says. From a longer-term perspective, she believes lentil will remain a “reasonably interesting” crop to grow.

The industry is also working hard to keep global doors open for Canadian lentils. With the Global Pulse Confederation, Pulse Canada has partnered with an Indian government agency to improve the relationship between India and pulse exporting nations.

“As India strives to meet its domestic policy goals of increased production and consumption of pulses, this partnership aims to ensure it is done in a predictable and transparent trading environment that allows pulse exporting countries like Canada to augment India’s domestic programs with imports when needed and allows growers in Canada to make the best planting and marketing decisions. That’s a

slower long-term process,” Ross says.

For example, there can be issues with clarity on how technical restrictions, such as acceptable weed seed levels, will be implemented.

Canada continues to work on smoothing trade restrictions on the technical side. “We feel we’ve more than demonstrated our ability to prepare shipments for export that meet their requirements and don’t require fumigation,” he says.

But Ross wants to underscore the fact that the health of Canada’s lentil market isn’t entirely dependent on our global customers.

“From a commodity association standpoint, market disruptions underscore the impact that a loss of market access in even one market can have on profitability of growers,” he says. “We need to diversify our end-use markets.”

Pulse Canada’s 25 by 2025 strategy aims to move 25 per cent of the country’s pulse production into new and diversified markets, including food, pet food and processing.

“There are bright prospects for Canadian pulses. We’re in the midst of a transition from relying on one or two markets to marketing Canadian pulses and pulse ingredients into new markets and applications that will have the greatest volume impact and focusing on the functional, nutritional and sustainability value Canadian pulses can provide over our competition,” Ross says.

On Dec. 18, 2019, new measures were announced by the Indian government’s Directorate General of Foreign Trade that represent an escalation of trade restrictions already put in place for peas.

The December bulletin indicated an amendment to the existing quantitative restriction policy for peas from all countries importing into India. The notification stated that peas imported into India under the current quantitative restriction would be subject to a minimum import price of about 200 rupees (approximately $3.56 CAD) per kilogram. In addition, all peas would have to be imported through the northeastern port of Kolkata.

“In layman’s terms what it is, is India continuing to demonstrate through restrictive import policies their strong mandate to impede the import of peas into India, their mandate to achieve self-sufficiency in pulse production, and their support for farmers through a number of different measures,” says Mac Ross, Pulse Canada’s director of market access and trade policy. “And as we’ve seen in the past with other policy measures implemented by India, it came without any prior notice to their trading partners.”

Ross explains that Pulse Canada is working with the Global Pulse Confederation to ensure that while India aims to meet their domestic objectives, they do so in a transparent and predictable trading environment.

At the time of publishing, India hadn’t released any more details.

In response, actions are being taken at home and abroad. Pulse Canada scheduled to meet with the Canadian federal government in January to discuss the most recent requirements. Pulse Canada will also be joining the Global Pulse Confederation on a trip to India in February to get some clarity and ensure that transparency and predictability are elements that are included in India’s policy moving forward.

Growers can turn to their provincial pulse organizations for the latest updates on these new restrictions. As stated in the full article, Ross says growers are well aware of the significant reduction Canada has seen in pea exports to India since late 2017, and the focus now is on diversification.

Provincial pulse organizations

• Alberta Pulse Growers: albertapulse.com

• Saskatchewan Pulse Growers: saskpulse.com

• Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers : manitobapulse.ca

Continued from page 4

ABOVE: Study results show a starter rate of 10 kg N/ha placed in the seedrow should maximize early-season growth in lentil.

sensitivities to crop injury from starter fertilizer placed in the seed row, from most sensitive to least: lentil > pea > chickpea > soybean > black bean > fababean. Lentil, pea and chickpea could generally only tolerate the 10 kg N/ha rates while soybean and black bean could tolerate 10 to 20 kg N/ha.

Fababean emergence appeared relatively unaffected by all three rates of N (10, 20 and 30 kg N/ha) and showed least sensitivity to seedrow fertilizer. In a separate trial, a zero tannin fababean variety had some sensitivity to the 20 and 30 kg N/ha rates of fertilizer application with reduced emergence compared to greater tolerance of higher rates of N in a tannin fababean variety.

“The greenhouse trials come with a caution that the soils were warm with good moisture. There wasn’t a lot of trash and they were low in available nitrogen,” Schoenau says. “Under field conditions, safe seedrow fertilizer rates might be lower.”

The ammonium phosphate sulfate fertilizer products also tended to produce less injury than the equivalent analysis blends when applied at a given N rate.

Soybean and black bean were most responsive to starter fertilizer with increased 30-day biomass production and nutrient uptake. Pea, fababean, lentil and chickpea early season biomass and nutrient uptake did not respond very much to the starter fertilizer applications, and there would be no benefit realized from going above 10 kg N/ha on this soil from any of the fertilizer products or blends.

“For most pulse crops, large amounts of nitrogen really are not necessary as

long as inoculation produces good nodulation and nitrogen fixation. The exception may be dry bean because we really don’t have a good inoculant for that crop,” Schoenau says.

Galpottage Dona also conducted several field trials. In 2018 she compared four rates of a starter blend applied in the seedrow with lentil and soybean with 15 per cent seedbed utilization. A blend of urea (46-00) and MAP (11-52-0) with an analysis of 28-26-0 was applied at a rate that supplied 0, 10, 20 and 30 kg N and P2O5/ha.

Consistent with the controlled environment study, 10 kg of N and 10 kg of P2O5/ ha as seed-row placed urea-MAP blend (28-26-0) was sufficient to maximize yield, N fixation and P uptake, but did not significantly reduce emergence, stand count or biological nitrogen fixation.

Another field-scale soybean experiment was conducted near the site where soil was collected for the controlled environment study. A 75:25 blend urea and monoammonium phosphate fertilizer (37-13-0) was applied that produced rates of zero, 17, 34 and 51 kg N/ha and zero, 6, 12 and 18 kg P2O5/ha. A paired row sideband configuration separated the fertilizer from the seed, and was used to limit the potential injury to soybean from the higher rates of N fertilizer.

In this study, poor nodulation was observed throughout the growing season due to drought conditions, which would have limited N fixation. As a result, the highest rate of N (54 kg N/ha) produced the highest soybean yield even though the plant stand was reduced at the high N rate.

Schoenau says that based on the re -

Lentil, pea and chickpea could generally only tolerate the 10kg N/ha rates while soybean and black bean could tolerate 10 to 20 kg N/ha.

sults of Galpottage Dona’s trials, 10 kg N/ha rate of a starter blend placed in the seedrow should be sufficient to maximize fababean, pea, lentil and chickpea early season growth. Higher rates of 20 to 30 kg N/ha in a starter blend may be desirable for black bean and soybean, especially under very low fertility and good moisture conditions.

“Maybe under some conditions with very low soil fertility, there might be a benefit to go with higher rate, but placement separate from the seed row would be the best option for higher rates,” Schoenau says.

Cereals? Canola? Honestly, you’d die of boredom. Lentils, on the other hand, are the jigsaw puzzle of prairie crops, a season-long agronomic challenge that only a rare breed of farmer has the skill and nerve to pull off. We get it, and we want to help. With two modes of action from Groups 14 and 15, Focus® herbicide delivers extended control of key grassy and broadleaf weeds. The kind of powerful, sustained weed control you’ve always wanted is here. Save on Focus® herbicide with FMC Grower CashBack.