by Brett Ruffell

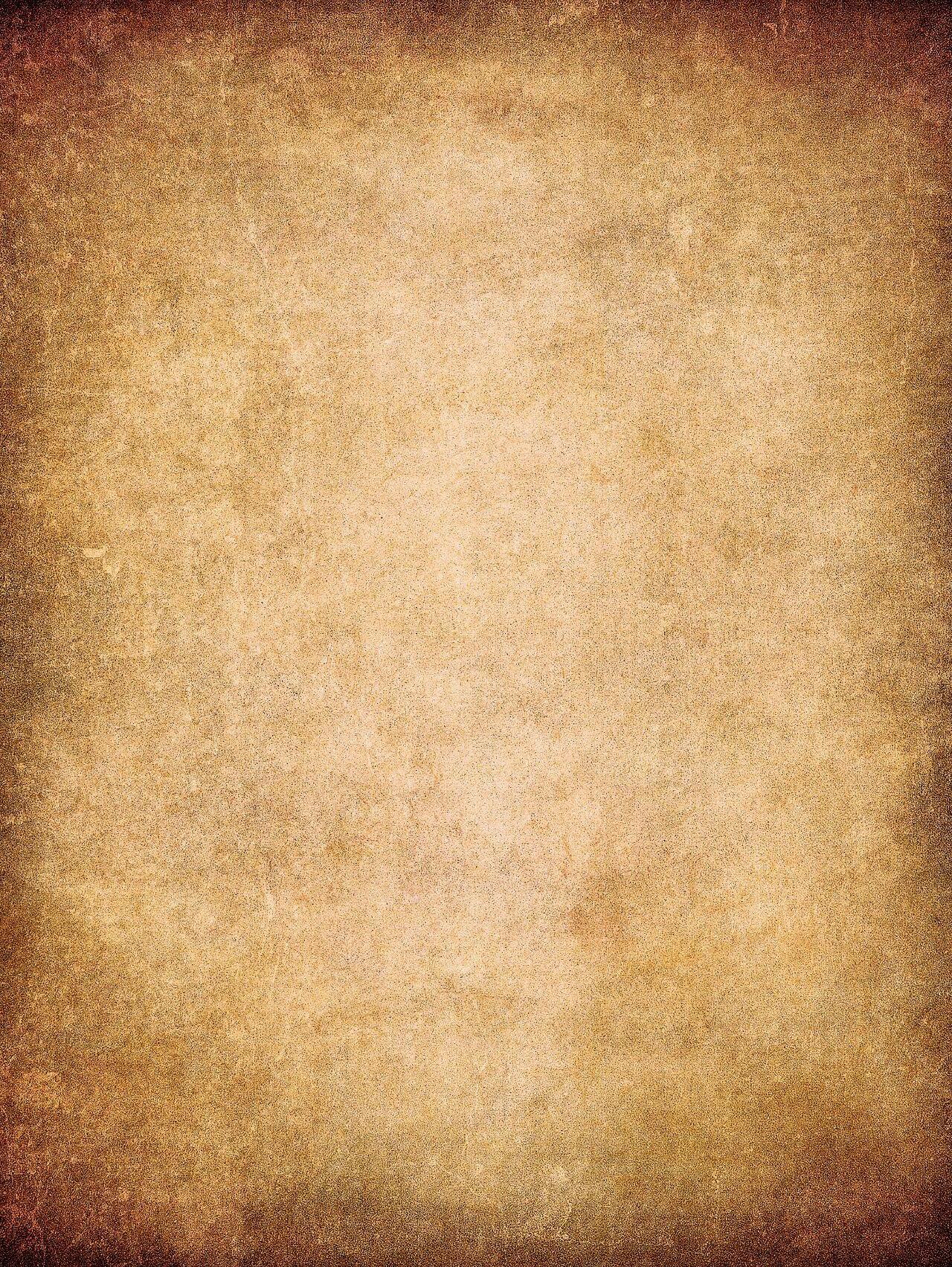

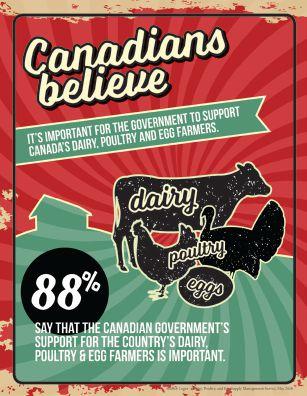

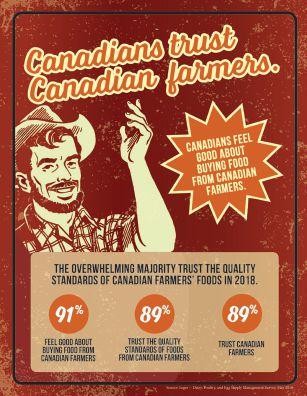

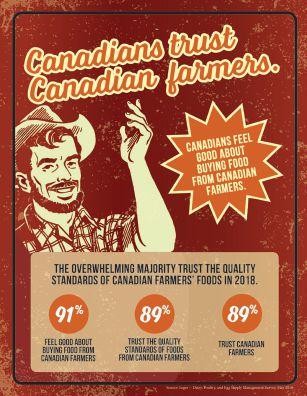

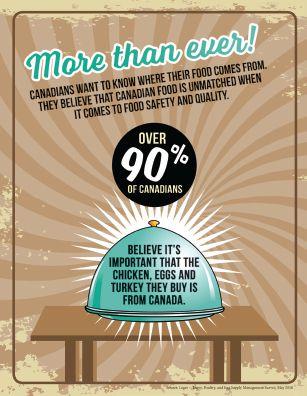

In a recent column, I shared one agvocate’s call to arms. As a refresher, dairy farmer Andrew Campbell has been speaking at poultry events from coast to coast urging producers in supply managed sectors to raise awareness about the value of the system.

Campbell says there’s great power in individual advocacy efforts, and emphasizes that even one-on-one conversations with people around town about the benefits of supply management are valuable. To that end, he advises producers to stay current on the latest evidence.

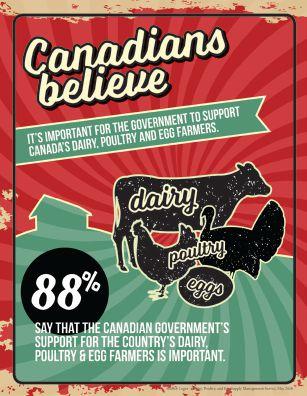

New research out of Laval University provides fodder for those conversations. Economists first set out to analyze the economic impact of agriculture. Using 2015 data from Statistics Canada, they analyzed six segments: eggs, chicken, diary, hogs, beef and oilseeds and grains.

They found the sectors together contributed over $8.7 billion to Canada’s GDP that year. That activity generated $1 billion in tax revenues. Then, they delved deeper into the data, separating supply managed and non-supply managed sectors.

They found that chicken, eggs and dairy only accounted for 20 per cent of farm receipts. However, the sectors were responsible for 25 per cent of total investments, 30

per cent of total jobs created and 28 per cent of total GDP generated by farm investments. In short, supply managed sectors punch above their weight.

In the second part of their research, the Laval economists took things a step further. They conducted interviews in three rural towns in Quebec – one where supply managed farmers were dominant, another where there was more of a mix and a third community with no supply managed producers.

They spoke to virtually every small business owner, farmers and even mayors.

“We were wondering about people’s perceptions regarding agriculture and supply management.”

“We were wondering about people’s perceptions regarding agriculture and supply management in terms of economic impact,” explains Laval’s Maurice Doyon, an agricultural economist.

The quick answer is they see supply management as vitally important. For one, it adds stability to local economies. The researchers talked to retailers who provide inputs for farmers. They said when other sectors are struggling, supply managed farm -

ers were always there to pick up the slack.

“So, although for a few years I will not sell any tractors to hog or grain farmers, I will still sell some to supply managed farmers, which keeps me in business,” Doyon says. “It keeps the infrastructure so when the other sectors pick up things aren’t dismantled.”

They also talked to retailers about indirect benefits of supply management. For instance, a restaurant owner said the system was a boon for her business. “She says it’s not that the farmers are all eating at my place,” Doyon says. “It’s all the activity around the farm that’s generating most of my business.”

Also of note, a hog farmer said he envied the income stability supply managed farmers enjoy because it makes it easier to invest. The producer said he had to sit on a pile of cash to prepare for bad times, as many go bankrupt during downturns due to cashflow problems. “The supply managed guys know they have regular income so they can plan and invest better,” he told the researchers.

Doyon proposes an ‘elevator pitch’ poultry producers could share: “The stability associated with revenue from supply management enables producers to make regular investments, which in turn allows communities to keep local infrastructure vital to agriculture and other sectors intact.”

canadianpoultrymag.com

Editor Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

National Account Manager

Catherine Connolly cconnolly@annexbusinessmedia.com 888-599-2228 ext 231 Cell: 289-921-6520

Account Manager

Wendy Serrao wserrao@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-6842

Account Coordinator Alice Chen achen@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5217

Media Designer Brooke Shaw

Circulation Manager

Anita Madden amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-442-5600 ext 3596

VP Production/Group Publisher Diane Kleer dkleer@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO Scott Jamieson

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Circulation email: rthava@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3555

Fax: 416-510-6875 or 416-442-2191

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Subscription Rates

Canada – 1 Year $32.50 (plus applicable taxes)

USA – 1 Year $70.50 USD Foreign – 1 Year $79.50 USD

GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above. Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2019 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664.3811

Fax: (519) 664.3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

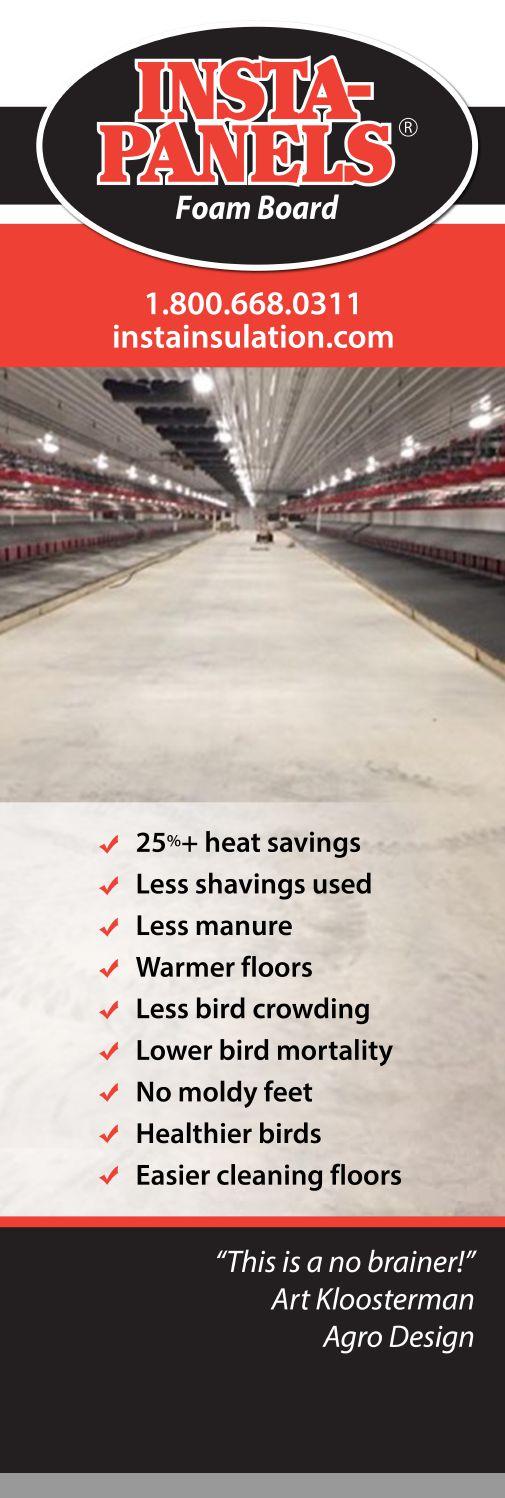

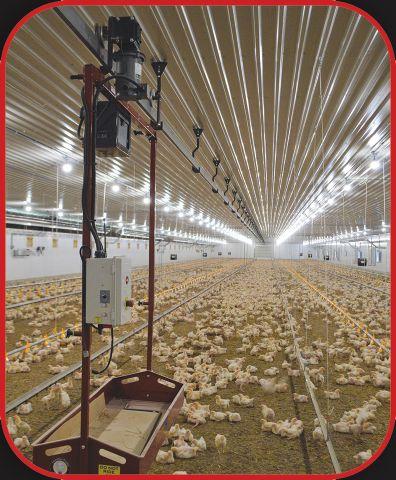

Lubing Conveyors are the safest ride for your eggs from nest to packer

The Lubing name has become one of the most trusted names in the industry because of our exceptional quality, reliability, performance and trouble-free operation.

Custom Configurations - Lubing Breeder Conveyors can be configured to work with any imaginable requirements; any necessary curves, heights and distances.

System Specifications - Available in 14-in and 20-in widths.

System Benefits - Eliminates manual labor of egg collection and reduces egg damage.

Fast Installation - Components ship completely preassembled for easy, quick installation.

Superior Service Life - With more than 40 years developing conveyor products, Lubing conveyors have an established reputation for longest lasting product life in the market

Les Equipments Avipor

Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263.6222

Fax: (450) 263.9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963.4795

Fax: (780) 963.5034

With market outlook indicators pointing toward partnerships to ensure growth, Exceldor and Granny’s cooperatives are combining their operations and members in a historic alliance. The main objective is to create a large cooperative that will be a leader in the poultry sector in Canada with operations in Quebec, Ontario and Manitoba, while keeping its ownership in the hands of producers committed to serving their customers well from coast to coast.

Canada and Ontario are supporting a project that will build and strengthen the capacity for the chicken industry to manage chickens in emergency situations. The governments committed up to $350,873 in cost-share funding to the Chicken Farmers of Ontario, working alongside the Ontario Broiler Hatching Egg and Chicken Commission and the Association of Ontario Chicken Processors. The money will go towards developing a third-party service that ensures chickens are handled in a humane manner during circumstances such as a disease outbreak or barn damage from fire or extreme weather.

Tim Hortons is testing a fake omelette — made with mung bean protein isolate — in two regions in southern Ontario. If it’s a hit, the product will join the Beyond Meat plant-based burger and breakfast sausage already on the menu at Tim Hortons and A&Ws across Canada. The fast food chains are meeting a growing demand for plant-based proteins from Canadians who’ve cut out or cut back their meat consumption

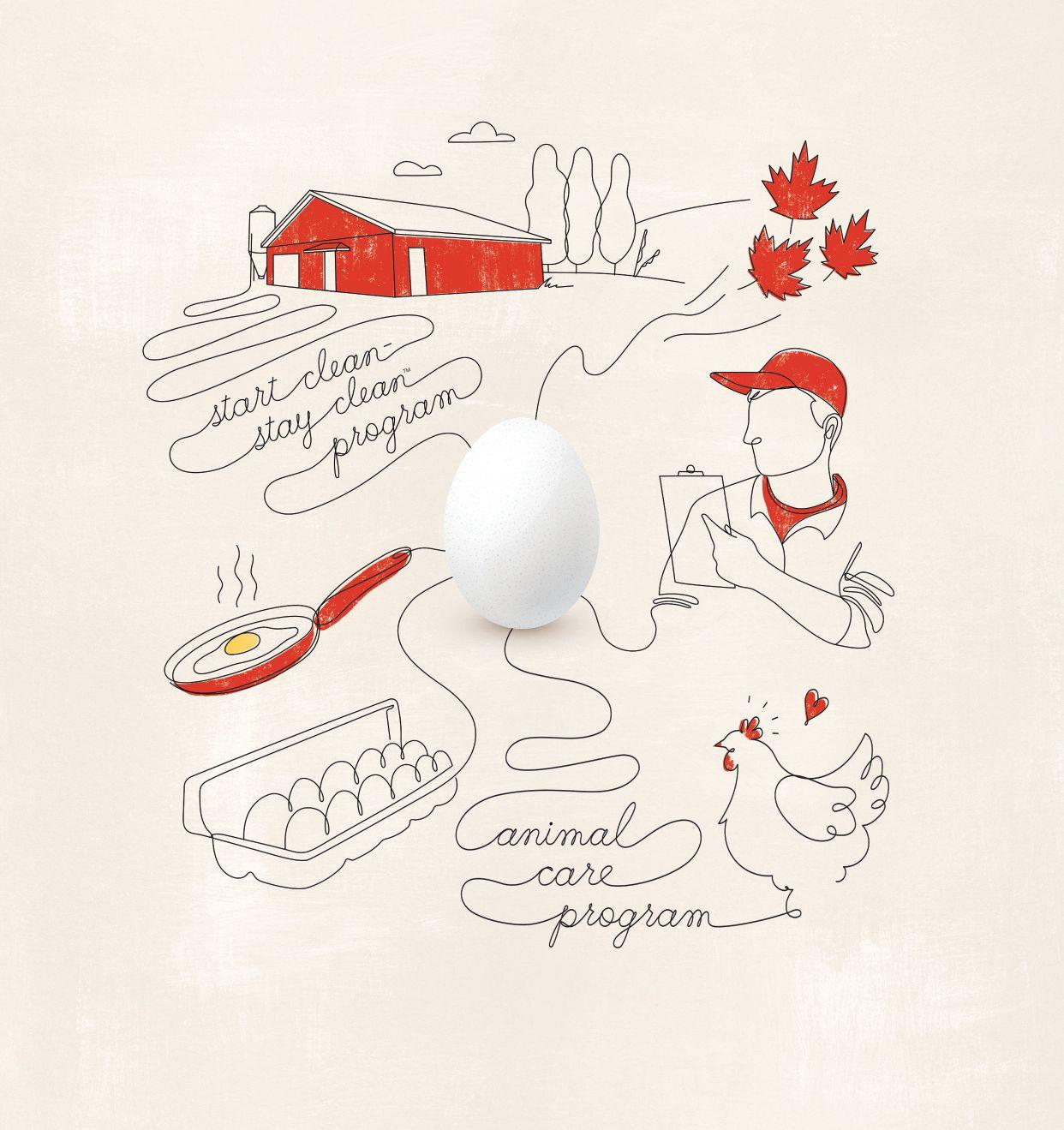

years is how long the standards set out under the EQA program have already been in place for all commercially produced Canadian eggs.

In late July, Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) announced the start of a new partnership with McDonald’s Canada.

It begins with the launch of the Egg Quality Assurance (EQA) certification mark on McDonald’s advertisements this summer for the freshly cracked Canada Grade A large egg in their limited-time Egg BLT McMuffin sandwich.

The McDonald’s advertisements will be the first time that most Canadians see the new EQA certification mark, with it appearing on television, print and digital channels until the beginning of September.

third-party audits.

“We are pleased that McDonald’s Canada is displaying our EQA mark on their McMuffin sandwiches, showcasing their pride in Canadian eggs and the farmers that produce them.”

“We are committed to industry leading certification, and working with other leaders is at the core of our sourcing strategy,” says Rob Dick, supply chain officer, McDonald’s Canada.

“Our goal is to benefit Canadian consumers and food producers, and working with EFC accomplishes exactly that,” he continues.

McDonald’s advertisements with the new EQA certification mark will appear on television, print and digital channels and run until the beginning of September.

“The EQA program is the culmination of decades of work building world-class standards in the Canadian egg industry,” says Roger Pelissero, third-generation egg farmer and EFC’s chair.

“Those standards are upheld through our national programs that include inspections and

All EQA certified eggs have met the highest standards of EFC’s national Start Clean-Stay Clean and Animal Care Programs.

The national organization’s goal with the program is to differentiate Canadian eggs by assuring consumers of those eggs’ quality, safety and humane-certified production practices.

April Sexsmith has served as general manager at Egg Farmers of New Brunswick for close to 30 years. Before that, she worked on several other marketing boards in a mix of supply managed industries and non-supply managed sectors. She then did a short stint with the provincial government working at the department of education before finding her true calling in the egg industry. With Sexsmith set to retire later this year, we asked her five questions.

You moved between several industries before landing in your current role. What is it about the egg industry that kept you interested for nearly 30 years? What has kept me here is the diversity. My job has changed so much over 29 years. There’s never been a time to step back and say, “Gee, I wish I had a few more challenges on my plate.” We’re one of the most dynamic industries. The Canadian egg industry always has a challenge and always meets that challenge head on. Really, our house is in good working order.

Describe the biggest challenges you’ve encountered in your role. The biggest challenges have been around trade. For instance, when we lost our first protection, our article 22, and had to move to tariffs. And then we saw our market continually eroded as we entered into more trade deals. Sustaining your industry when that happens is the biggest challenge.

What is your proudest achievement from your time working in the egg industry?

I wouldn’t be able to list just one. My proudest moments are anything new I’ve been able to

achieve side by side with the board. Take strategic planning, for example. Bringing the board into the strategic planning process, setting our vision and direction and continuing to do that is a proud moment. Also, setting up the new entrant program. And getting all our regulations and policies and structure in place so we can operate under a fair and equitable structure has been a defining moment. Just being able to represent New Brunswick at the national committee level is a proud moment as well. Any time I can be out there talking about our industry, how great our province and our producers are – I do that with a lot of pride.

Any advice for your successor?

My key piece of advice would be to always put your industry first, whether that’s in the decisions you make or the proposals you put forward. And as one of my directors likes to say, make sure you’re doing the right things for the right reasons.

Any post-retirement plans?

My first plans are just to see how it feels not to work for a while. I’ve never had a break other than on vacations. My husband and I love to travel and hope to do more of that. My husband’s in the education system. We’re actively looking for schools we can volunteer in to help struggling students. And I’d like to rediscover some hobbies that I had to let go of due to time constraints. I’ll continue to follow the egg industry, like I have with the others. I’m anxious to see what happens to the industry and where it goes. Of course, I’ll be its biggest supporter, out there buying my 18 pack of eggs.

April Sexsmith is general manager of Egg Farmers of New Brunwsick.

SEPTEMBER

SEPTEMBER 4

PIC Golf Tournament, Baden, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

SEPTEMBER 10-12

Canada’s Outdoor Farm Show, Woodstock, Ont. outdoorfarmshow.com

SEPTEMBER 22-26

IEC Global Leadership Conference, Denmark internationalegg.com

SEPTEMBER 23

PIC Science in the Pub, Guelph, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

OCTOBER 2018

OCTOBER 1-3

Poultry Service Industry Workshop, Banff, Alta. poultryworkshop.com

OCTOBER 9-10

Alberta Livestock Expo, Lethbridge, Alta. albertalivestockexpo.com

OCTOBER 24

PIC Annual Meeting, Guelph, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

OCTOBER 27-29

AWC EAST 2019, Niagara Falls, Ont. advancingwomenconference.ca/ awca

NOVEMBER

NOVEMBER 4-6

Poultry Tech Summit, Atlanta, Ga. wattglobalmedia.com/poultrytechsummit

As Canadian egg farmers transition their flocks from conventional cages to more spacious “furnished” cages, University of Guelph researchers have conducted a first-ever study on factors contributing to feather pecking in this new housing system and ways to prevent it.

The study revealed that 22 per cent of the birds in the new cages exhibited moderate or severe feather damage that was likely due to feather pecking.

Published in the journal Animals, the study found that several factors contributed to feather pecking, including genetics, lack of access to a scratching or foraging area and midnight feedings.

“This study is the first in Canada – and possibly North America – to look at this issue in furnished cages, and we hope it will inform farmers about the factors involved so that they can understand the problem and develop action plans to prevent it,” says Alexandra Harlander from the Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare, who co-authored the study with post-doctoral researcher Nienke van Staaveren.

Feather pecking is destructive nipping at another hen’s feathers and occurs in all forms of housing, from conventional cages, to free-run facilities, to free-range farms.

It is one of the significant challenges facing egg farmers, Harlander says. “No farmer wants to see this.”

It’s not clear what causes feather pecking; the best theory is that it is a form of redirected foraging behaviour, van Staaveren says.

“But even in housing systems where there is a lot of substrate to peck at, it can still occur. So it’s tricky to control and something we are still trying to understand,” the researcher says.

Pecking leads to a loss of feather cover, which makes it difficult for birds to maintain their temperature and navigate their environment. What’s more, once a bird has been singled out for pecking, it becomes a target for further pecking.

One of the goals of the study was to provide feather-pecking management guidance to farmers who are transitioning to alternative housing systems to meet the Egg Farmers of Canada’s call for alternative hen housing systems by 2036.

For this study, the research team sent questionnaires to egg farmers across Canada who housed their chickens in furnished cages. They asked the farmers to score the feather cover of 50 of their birds on a three-point scale, to estimate the prevalence of feather damage.

Of the 26 flocks, approximately one-in-five birds in the furnished cages exhibited moderate or severe feather damage. The factors that had the most influence on feather damage were older flock age, brown-feathered birds, midnight feedings and lack of a scratch substrate.

Van Staaveren says brown birds are likely more susceptible to pecking because the stronger contrast in colour when they are pecked and drop feathers attracts further pecking.

Another key factor was midnight feedings.

Farmers may turn on lights at night to wake the hens and encourage feeding so they take in more calcium to increase eggshell quality and laying productivity.

The study found midnight feeding was linked to more pecking, likely because awake chickens find easy pecking targets in inactive birds.

Chicken Farmers of Ontario (CFO) is pleased to launch the application process for its second Ontario Chicken Innovation Award, part of the organization’s commitment to help bring new, innovative Ontario chicken products to the plates of consumers. This year, CFO has millions of kilograms of chicken available for successful applicants. Applications are available at chickeninnovation.ca, and will be accepted until September 13, 2019.

Hy-Line International recently celebrated the completion of its newest research farm surrounded by federal, state and local dignitaries at a ribbon cutting ceremony. Named after the company’s founder, Henry A. Wallace, the state-of-the-art facility is located stateside in central Iowa. The addition of the new research farm increases the population of research birds from which to identify the top performing individuals to populate the next generation.

Alltech has appointed a new chief scientific officer. Ronan Power has assumed the role following the retirement of Karl Dawson in June. Power joined the Alltech team in 1991. As chief scientific officer, he will oversee more than 100 researchers worldwide, more than 20 research alliances spread over 12 countries, and four bioscience centers, located in the United States, China, the Netherlands and Ireland.

By Gbenga Alade

Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC)’s antimicrobial use reduction strategy is well thought out and ideally paced. This is evidence of the strong leadership that continues to elevate the importance of responsible use of antibiotics in animal agriculture. This is despite reports surmising that more than half (59 per cent) of antimicrobials used in broiler chickens were in classes not used in human medicine, such as ionophores and chemical coccidiostats used to prevent coccidiosis.

The CFC strategy is a three-step process towards the elimination of preventive use of all antibiotics considered important in human medicine. The first and second steps are already completed with the elimination of preventive use of Category I (those most critical to human health) and Category II antibiotics in 2014 and 2018 respectively.

Thankfully, it is well-recognized that the therapeutic use of antibiotics, under the guidance of a veterinarian, must always be an option to prevent potential adverse animal health and welfare outcomes. We must continue to strike a disciplined and educated balance between human health considerations and the welfare of the birds in our care.

Chicken farmers are working alongside veterinarians to administer antibiotics in animals for three main reasons. Firstly, to treat an illness that has been diagnosed. Secondly, to control the spread of illness in a flock. And lastly, for the prevention of an imminent illness in a flock at risk of exposure.

I understand that the reduction of antibiotics can potentially introduce

challenges, which Ontario’s farmers have recently met with mettle. Some of the challenges that have been reportedly associated with reduction or elimination of antimicrobial use include increasing disease burden, especially necrotic enteritis and coccidiosis, as well as an increased feed cost associated with alternative products required in cases where antibiotics are eliminated or reduced.

ment of the birds. That includes, but is not limited to, paying close attention to water and feed consumption, the barn environment and optimum biosecurity that will potentially reduce challenges brought on by disease-causing organisms.

As farmers, doing all that we can to lessen the potential impact of antimicrobial resistance makes the journey worthwhile.

As always, with challenges we also look for opportunities to rethink how we have previously practised raising broiler chickens. We can learn a lot from jurisdictions that are further ahead in the antimicrobial reduction journey and from farmers within Ontario that have experienced positive production in the reduced antimicrobial environment.

Two common factors and messages emanate from these groups: It is achievable and the right thing to do; and there is no single solution that will replace the antibiotics that are eliminated.

Farmers and industry partners that have experienced success in a reduced antibiotic environment stress the importance of paying keen attention and taking care of every little detail that involves manage -

In addition, practices such as optimizing downtime and reducing bird density have been shown to be good tools in a reduced antibiotic environment. A holistic approach that leverages development of a flock health plan and working closely with a veterinarian to ensure early detection and treatment of a flock illness will go a long way to ensure success.

Farmers are not left to bear the burden alone. Government and industry stakeholders, including the research community, are driven to look for solutions by targeting meaningful work that will benefit farms and birds in this reduced antibiotic environment.

We cannot lose sight of the fact that this is all about public health. As farmers, doing all that we can to lessen the potential impact of antimicrobial resistance makes the journey worthwhile.

For references, see the online version of this article at canadianpoultrymag.com.

By The Canadian Poultry Research Council

Marie-Claude Bibeau, Canada’s minister of agriculture and agrifood, officially announced a five-year $8.24 million investment in the Canadian poultry industry in May at the University of Montreal in St-Hyacinthe, Que. The funding is under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, AgriScience Clusters Program and is in addition to an investment of $3.78 million from industry and other levels of government.

CPRC’s chair, Helen-Anne Hudson, and research coordinator, Caroline Wilson, as well as representatives from all poultry sectors, were present. During her speech, Bibeau declared: ‘’Our government is committed to helping Canada’s poultry sector maintain consumer trust and stay on the cutting edge by finding new and innovative solutions to challenges faced by the industry. This funding will play an important part in ensuring that the sector is able to continue to grow sustainably and do more to meet high consumer demand.”

“Funding for the third poultry science cluster allows the poultry industry to conduct research projects that reflect the priorities of the industry and Canadian consumers.”

After the announcement the minister, journalists and industry representatives visited the laboratory of Martine Boulianne, where two of the funded research projects are being conducted. These undertakings aim to develop an in ovo vaccine against Clostridium perfringens and vaccine strategies to protect broiler chickens against necrotic enteritis.

CPRC will coordinate and administer research funding and reporting of 19 research projects, five of which are led by AAFC researchers. The projects reflect

the priorities of the industry, governments and Canadian society. A total of 74 individual researchers will be involved in projects across Canada with input from global scientists.

The 19 research projects encompass four research themes. Almost half of the projects are investigating antimicrobial stewardship in poultry production, which includes research in vaccine development and antimicrobial alternatives.

The poultry health and welfare themed projects include research that will identify developmental determinants of successful behavioural adaptation, the impact of stocking density on performance and welfare of turkey hens and the optimal dietary phosphorus and calcium levels in pullets and laying hens to maximise bird health and performance. Within the food safety theme, researchers are looking at the development of vaccines to reduce Campylobacter colonization in chickens, mitigation of Campylobacter jejuni strains within the broiler production continuum, bacterio -

phage intervention during processing to control Campylobacter and Salmonella contamination.

The fourth theme is comprised of research focusing on sustainability of the Canadian poultry production system. These projects include: Evaluating control strategies to reduce emissions of particulate matter, ammonia and greenhouse gases from poultry operations; assessment of infectious bronchitis virus on egg production and fertility of chickens; and methods to enhance development and maintenance of a functional intestinal tract in poultry.

Hudson welcomed the announcement. “Funding for the third poultry science cluster allows the poultry industry to conduct research projects that reflect the priorities of the industry and Canadian consumers.

“Canadian poultry farmers are constantly evolving their production practices. As part of the cluster, funding will also be used for knowledge and technology transfer to farmers and other poultry value chain members such as input suppliers, processors and the retail component of the industry.”

By Tom Inglis

Tom Inglis is managing partner and founder of Poultry Health Services, which provides diagnostic and flock health consulting for producers and allied industry. Please send questions for the Ask the Vet column to poultry@annexweb.com.

Low uniformity and delayed growth in a flock can have many causes and contributing factors. Are these problems in your barn? Are they recurrent in specific barns despite changing feed or breed?

There are a number of non-infectious potential causes of poor uniformity and delayed growth that exist, including faulty poultry genetics, management and nutrition to name a few.

One of the most important causes in recent years is a disease syndrome known as runting-stunting syndrome (RSS). In this article, we explain what RSS is and describe some contributing factors as well as some practical control strategies producers can implement in the field.

Recognized since the late 1970s, this syndrome has had many names besides RSS, such as brittle bone, helicopter-wing, malabsorption and pale-bird syndrome. All of the many names of this disease are highly descriptive. “Runting-stunting”, for instance, is formed by “runt”, which in poultry refers to the smallest animal in the barn, and “stunting”, which is an impairment of the expected growth of an animal.

Sick chicks show diarrhea, feathering problems, low weight, elevated feed conversion and depression. Because of the watery droppings, the litter quickly becomes damp and birds may be observed to be dirty in the abdominal area.

Upon necropsy, these affected birds have small livers with enlarged gallbladders, and they have

gas-filled dilated intestines with thin walls. It is generally recognized that RSS is caused by co-infections of multiple viruses – such as rotavirus, astroviruses and reovirus – that can be vertically or horizontally transmitted.

characteristics of RSS was observed in the challenged groups. In this case, a Cluster 1.1 ARV, highly similar to the 1733 vaccine strain (a strain causing RSS-like clinical signs), was isolated from the negative controls.

Recognized since the late 1970s, runting-stunting syndrome has had many other names, including brittle bone, helicopter-wing, malabsorption and pale-bird syndrome.

Researchers have yet to study the influence of recent emerging variant Avian Reoviruses (ARV) on RSS. These emergent ARVs have been linked primarily to viral arthritis (VA); however, VA-affected flocks are routinely found light in weight and, in some RSS field cases, viruses with 100 per cent identity can be found in the intestine and tendon (Cluster 3).

In an unpublished study conducted at the University of Calgary-Careem’s lab, with a Cluster 5 ARV obtained from a case of VA and inoculated in broilers chickens at day of age, a syndrome with

This Cluster 1.1 ARV was also isolated from the affected birds along with the challenge virus. It is likely that this virus was vertically transmitted and interacted with the Cluster 5 ARV to produce RSS-like clinical signs (e.g., low weight, depression) along with sudden death (See Figure 1).

Duodenum microphotographs show a severe villous atrophy in some birds from the challenged groups. Damage to the gut will contribute to poor nutrient absorption and other factors, leading to delayed growth and poor flock uniformity. Reproduction of the

observations with the isolated virus will be attempted in future experiments.

Multiple viruses have been obtained from birds affected with RSS, including rotaviruses, astroviruses and reoviruses, which can be horizontally and vertically transmitted. Although a few characteristics of RSS have been replicated with some reoviruses and astroviruses under experimental conditions, the consensus is that the disease is caused by a combined viral infection rather than a single virus infection. All bacterial candidates for RSS have failed to reproduce the disease. Usually it occurs sporadically, with increasing severity in a particular barn.

A diligent cleaning and disinfection process is crucial to diminish the economic impact of the disease.

There is no treatment for this disease. Producers can limit

economic losses with good management practices (e.g., proper brooding temperatures) and by culling the affected birds, which will not recover from the disease.

As the disease can be reproduced with contaminated litter obtained from affected farms, it is clear that the litter is infectious and will cause the disease in future placements.

Removing or treating builtup litter, treating affected houses during downtime with heat and providing more downtime will decrease the severity of the condition in the next production cycle.

In short, a diligent cleaning and disinfection process is crucial to diminish the economic impact of the disease. Otherwise, it is highly likely that the disease will affect your next flock.

For references, view the online version of this article at canadianpoultrymag.com.

This article was written by the veterinarians of Poultry Health Services Ltd. Poultry Health Services is a private veterinary practice providing diagnostics for Alberta poultry producers as members of the Poultry Health Centre of Excellence (PHCE). Please call 1-888-950-2252 if you have a mortality problem or want help making a submission.

By Treena Hein

Avian influenza, especially in its highly pathogenic form, remains a serious threat to the poultry industry worldwide. By early June this year, the World Organization of Animal Health had reported detections of the disease in a whopping 25 countries, including Mexico but fortunately not the U.S. or Canada so far. The strategy for avian influenza virus (AIV) surveillance around the world, therefore, matters a great deal.

Wild birds, particularly waterfowl, are the natural reservoir for AIVs and spread them across the globe during migration. Current surveillance involves collecting samples from wild birds killed by hunters or that died due to natural causes. Live capture and release is very difficult.

The DNA/RNA in fecal swabs is tested for type of AI, to see what strains are where on the globe and if new strains have appeared. However, this strategy is both inefficient and ineffective, explains William Hsiao of the B.C. Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC), University of British Columbia (UBC) and Simon Fraser University.

Because wild birds usually do not suffer systemic infections from AI like commercial poultry do, Hsiao says surveillance involving random capture means that some or even many wild birds that carry the virus in its many forms could be missed. Testing larger numbers of wild birds is not feasible due to high costs, stress on the birds, ecological disruption and so on.

Testing wetland sediments where wild bird feces accumulates, however, could be a way to not only determine what strains of virus are present in wild birds each year but to also establish whether new strains have appeared – all before an outbreak in a commercial flock occurs.

So, in 2015, after the major AI outbreak in B.C., the provincial government sought a novel surveillance approach. About 240,000 poultry birds died or were destroyed to control that outbreak, and over 48 million were lost through outbreaks in the U.S. around the same time.

A team involving Hsiao and partners such as the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative (CWHC) did a pilot study to analyze wetland samples. The results were very promising, with a 24 per cent rate of virus detection compared to less than a one per cent rate of detection through wild bird swab sampling.

The project was supported by $2.5 million from partners such as Genome B.C., the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and the Sustainable Poultry Farming Group. The research is still going strong.

Hsiao is a co-lead investigator with Chelsea Himsworth of the B.C. ministry of agriculture and CWHC, Jane Pritchard of the B.C. ministry of agriculture, Natalie Prystajecky of BCCDC and UBC and Craig

Stephen of CWHC.

Reflecting on this surveillance strategy in comparison to wild bird sampling, Himsworth notes that in a given wetland sediment sample, the feces of potentially several birds can be present. This makes the chances of getting a viral RNA sample much higher.

“In the proof-of-concept study from 2015 to 2018, we found AIV RNA in 20 per cent of samples – and none was found in wild birds prior to the HPAI outbreak in 2014/2015 in B.C.,” she explains.

“We found huge numbers of viral subtypes and strains in the sediment samples. There were up to 16 different AIV subtypes in a single sample. In a bird sample, if you can get any viral material at all, you might get one subtype that that particular bird happens to be carrying.”

“It’s a fairly novel approach to doing population-level sampling,” notes Prystajecky, “and a strategy, combined with genomics technology, that can really compliment surveillance globally and locally. We are talking to research groups in Canada, the U.S. and Europe and they are very interested to know how things are progressing. A group at the Animal and Health Agency of the U.K. also wants to collaborate.”

In the pilot study, the team used sampling technology from a B.C. firm called Fusion Genomics. However, because the firm’s probes are proprietary and limit the ability to add new probes as new AIV variants emerge, the team has developed its own probes.

“We would like our method to be what’s called ‘open source’ or freely available in order to enable this type of surveillance to move forward globally,” Himsworth explains. “We estimate that in two years, we will be able to release a research manual for others around the world, covering from how to best sample to how to make the probes to how to best do data analysis.”

PhD student Kevin Kuchinski of UBC and BCCDC says the team’s new probe approach works similarly to probes they’ve used before – a DNA sequence is placed on the probe, which is then exposed to the sample. It may contain matching DNA that automatically attaches to the probe sequence, making the helical ladder structure of the DNA molecule complete.

“Harnessing the way DNA matches up is used in countless technologies around the world,” Kuchinski says. “We send the sequence we want to a probe manufacturer and it comes back within a week or two. We tested our probes on a small number of samples this spring, and detected several AI strains commonly found in North American wild birds, as expected. We will now test hundreds more sediment samples to make sure the technology scales well.”

The ability to detect new AI strains that may appear in future has also been worked into the new probe design. “Some parts of the influenza genome never change, and we’ve included these sequences in our probe panel,” Kuchinski explains. “So, if we are detecting a lot of match-up from those probes, but not detecting the crucial H or N genes, that’s a red flag that there is something new out there and it’s time to design more probes.”

24% is the avian influenza virus detection rate researchers achieved by analyzing wetland samples, compared to less than a one per cent rate through wild bird swab sampling.

Not only is the probe technology changing, but the group is also optimizing the way it collects wetland samples – and how it will recommend other groups around the world conduct sampling.

PhD student Michelle Coombe of UBC and the B.C. ministry of agriculture notes that the areas in a particular wetland where sediment samples could be taken is very numerous, and the number of wetlands even in a fairly small given region is vast, making the total sampling area extremely large.

“Where we sample is important, as collecting and analysis of samples takes time and costs money,” Coombe explains. “We want to get the most surveillance bang for our buck, so we need to find out if there are factors in

the environment that help predict if there is a larger amount of, or any, AIV RNA in the sediment at a particular site.

“Does the pH or chemical composition of the sediment/water matter much, or are observations of wild bird flocks our best

predictor? We are working on some mathematical models to help us determine this.”

Not only does the area where a sample is taken matter, but the type of sediment may also matter – that is, some sediments are better than others in terms of their willing-

Bird welfare and bird performance go hand in hand. Potable drinking water and dry friable litter promotes healthy birds and improve production results. Ziggity continually innovates with products and management tools to deliver on these critical needs.

ness to give up pieces of AI viral RNA.

“We still don’t know whether one type of sediment is better than another at doing this,” Coombe says. “We know that viral RNA can have an electrostatic charge and some of it sticks to sediment particles and some doesn’t. While sticking to sediment protects RNA from the degradation that it usually experiences from floating freely in water, getting it away from sediment particles is an issue.”

In the end, it could be that the abiotic factors are more important, and the number of birds at a particular site may not matter very much in terms of optimized sampling. “We just want to make the sampling process as efficient and effective as possible,” says Coombe.

D r i n kers eng i neere d for t he way birds drink.

Pi pe i nter i ors have virtually no obstruction for ef fec tive flushing and a smooth inner wa ll that inhibits biofilm formation

An d vi sit Ziggity.com/installation-videos/ for videos to help optimize your system installation.

The Poultry Watering Specialists

We focus on making dr inkers that discharge the right amount of wate r there by eliminating or minimizing spillage for friable litter and improved bird welfa re

S olenoid Re g ulator affords unattended high p ressure dr inker line flushing, an effective tool for preventin g biofilm and removing se diment.

Transparent Pi pe K it

A great monitoring tool for producers allowing them to see what is going on inside the drinker line so that adjustments can be made to p revent or remove biofilm.

Visit ziggity.com

© 2019 Ziggity Systems,

The fragility of RNA means that it’s always very likely fresh. “It seems that the virus doesn’t survive well year over year, based on preliminary data,” Himsworth explains. “The sediment, as it dries over the summer, goes through a self-sterilization. Birds come through in the spring on their migration and the wetlands then bake and dry up in the hot sun. The UV radiation is quite effective at destroying it.”

The scientists will also determine that a sample taken in the spring is not from last fall, which indicates if viruses in the sediment are a current reflection of viral strains circulating in wild ducks and, thus, how risky a particular season is with respect to potential transmission of AIV from wild birds into poultry.

“Our study will investigate this question,” she says, “by comparing the genetic relationship of AI viruses found in sediment to those found in wild ducks on the same wetlands and will observe if the viruses found in the sediment change, or don’t change.”

The study will continue for two more years. In addition to finalizing probe design and optimizing the sampling strategy, the team, through doing simultaneous sampling of sediment and wild birds, will continue to determine how good a mirror sediment is to what wild birds are actually carrying.

Sign up for our e-newsletter eggfarmers.ca/newsletter

Like us on Facebook Facebook.com/eggsoeufs

Follow us on Twitter @eggsoeufs

Follow us on LinkedIn LinkedIn.com/company/ egg-farmers-of-canada

Understanding how the gas is formed, its impacts and what can be done to manage it.

By Kayla Price

One of the biggest complaints surrounding the poultry barn – apart from flies – is the smell of the manure. The excessive amount of ammonia gas released from poultry manure not only contributes to this smell but can be harmful for both the birds in the barn and the workers who frequent the barn. Understanding how ammonia gas is formed, the major and minor impacts it can have on the bird and what can be done to manage this issue can be helpful for proper poultry management.

Protein is an essential component of poultry diets, as it is needed for the bird to gain and maintain body weight for the production of either meat or eggs. The building blocks of protein are amino acids, and proteins also contain nitrogen. Some of this nitrogen can be used by the bird and incorporated into tissues or eggs, but most of it must be excreted in the form of urine (the white part of bird droppings) or feces.

The nitrogen in the urine and feces is excreted in the forms of uric acid (around 80 per cent), ammonia (around 10 per cent) and urea (around 5 per cent). Once the uric acid and urea are excreted, they are converted to ammonia through microbial and enzymatic breakdown via the bacteria and enzymes found in the manure. The microbial and enzymatic breakdown process can only happen when the temperature, moisture, pH and nitrogen in the manure or litter fall within specific ranges and levels.

Without any further control, up to 50 to 80 per cent of the nitrogen in manure may be converted to ammonia. After this process, it is readily released into the air as a gas that can be detected by both birds and farm workers. Combined with water, gaseous ammonia can be associated with dust particles or moisture that come into contact with the mucus membranes of the body (e.g., eyes, respiratory tract, etc.).

Several factors can influence how ammonia is formed and released into the barn environment. The release of ammonia into the barn air can be impacted by the litter type, bird activity,

stocking density, manure handling, frequency of manure removal and ventilation rate. The main factors that influence how manure bacteria and enzymes break down nitrogen to form ammonia are the nitrogen content, temperature, moisture/humidity and pH. The nitrogen content of the manure can be influenced by the amount of protein and amino acids in the diet. If there is excess crude protein in the diet, or if the amino acid levels are not balanced, then the amount of nitrogen in the manure may increase. If the gastrointestinal tract is not properly functioning or digesting protein, then the level of nitrogen in the manure may increase. Often, in the poultry barn, the temperature, moisture or pH of

the manure/litter can play an important role in the degradation of manure nitrogen to ammonia and the release of this ammonia into the air. The bacteria that are crucial for the breakdown of manure nitrogen require an alkaline pH of around 8.5. Typically, however, the pH of excreted poultry manure or litter is around a pH of 7.5 to 8.5.

The impact that the manure or litter moisture will have on the release of ammonia is dependent on the housing system used. For example, in floor or aviary systems, litter moisture is the more important factor in the conversion to gaseous ammonia, but in cage or slat systems, manure moisture plays a bigger role.

Regardless of the system, when it comes to their impact on the ammonia level, the ambient temperature and moisture level of the manure or litter are related. An increase of 1 to 2°C can affect ammonia levels, and that impact can be multiplied when combined with different moisture levels.

Generally, manure microbes grow at an optimal temperature range of 34 to 37°C, but they may also be able to grow at temperatures outside of this range. Some studies have found a maximum ammonia release at different litter temperatures (18.3 to 40.6°C) and moisture levels (38.3 to 47.8 per cent) in broiler barns, with the highest releases being at the highest temperatures and moisture levels.

Similar results have also been seen with layer hen manure moisture; studies have found that hen manure moisture levels of 37 to 51 per cent resulted in maximum ammonia release.

The relative humidity level of the barn can also impact the moisture level of the litter or manure. Humidity levels of 45 to 75 per cent may increase the release of ammonia. All these factors must be taken into consideration, as the temperature, relative humidity, litter/manure moisture and pH levels must all fall within a range that maintains the welfare of the bird.

But it is important to note that those ranges may also be conducive to maximizing the release of ammonia. As such, it is crucial to strike a balance between maintaining a good environment while also attempting to minimize the release of ammonia.

The issue of ammonia levels and their impact on birds – as well as humans – has long been a popular topic of discussion. Different countries and certifying bodies have different limits defining what is acceptable.

In Canada, the highest acceptable limit for ammonia levels in the barn is 25 ppm. Some groups advise that safe exposure should fall under 10 ppm of ammonia, but this may be difficult to consistently maintain in a barn environment.

Various groups have suggested that 25 ppm of ammonia for eight to 10 hours should be the maximum exposure for humans, while others suggest that 35 ppm for 15 minutes is still acceptable, and still others suggest that 50 ppm for eight hours is within reason. Every group agrees, however, that exposure of at least 12 ppm in humans can impact lung function and that exposure to 300 ppm or more is considered an immediate threat to human life and health.

The results from poultry research studying how ammonia levels can impact production are varied. Some groups suggest that 25 ppm should be the maximum, whereas other groups suggest that exposing birds to 20 ppm for long periods of time could lead to issues like lowered immune protection and respiratory tract damage. Other research suggests that, when poultry can choose between environments featuring different ammonia levels, they choose environments with ammonia levels under 11 ppm.

When it comes to detecting ammonia, a human nose that has not been exposed to it may be able to perceive levels of 10 ppm or above. The minimum level of detection will increase, however, with prolonged or frequent exposure, as ammonia irritates the respiratory mucus membranes, causing chronic inflammation of the sinuses.

As such, for those who work in a barn environment, attempting to detect ammonia levels based on smell alone will not be effective. Ammonia detectors, which are easily accessible, are more sensitive and, thus, more accurate than the human nose.

Ammonia is toxic to animal cells. High levels of ammonia may lead to observable changes, such as snicking, difficulty breathing, irritation of the trachea (breathing tube), air sac inflammation, inflammation of the mucus membranes of the eye, or a combination of these symptoms.

Many other, less obvious changes can take place upon exposure to lower levels of ammonia. Studies have found that exposure to 20 to 25 ppm throughout production can result in increased sus-

ceptibility to secondary challenges (e.g., viral or bacterial), decreased feed efficiency and tissue damage. These changes have been noted in broilers exposed to ammonia levels that consistently fell between 20 to 30 ppm for 16 to 28 days.

Studies of turkeys have found that, among birds dealing an E. coli challenge, those that were exposed to ammonia levels between 10 to 40 ppm had more bacteria in their lungs than the birds that were not exposed to ammonia. In layers, it has been suggested that early exposure to ammonia could have a lasting effect and impact how pullets perform later as laying hens. Additionally, chronic exposure to high ammonia concentrations may impair egg production for layers.

At a microscopic and molecular level, researchers have found that exposure to ammonia can trigger changes within the animal. In rats, increased ammonia levels have been shown to reduce oxygen intake and lead to decreased energy efficiency. In these same rats, ammonia had a negative impact on the gastrointestinal lining, which reduced the survival of intestinal cells, thereby damaging the intestinal lining and impairing functions.

In human gastric cell lines, ammonia has been shown to accelerate cell death. In poultry, high-level exposure to ammonia for 20 days decreased the intestinal surface area (possibly impacting nutrient absorption), decreased the bird’s resistance to oxidative stress, altered the intestinal tract’s ability to break down nutrients and impacted immune organs.

In ducks, exposure to ammonia concentrations of 10 ppm or 75 ppm for 30 days impacted the abundance and diversity (i.e., the number of different microbial species) of caecal microbes. When both concentrations were presented to the different duck groups for 10 days, however, the higher concentration had a bigger impact on the caecal microbial communities.

Exposure to high concentrations of ammonia for even a short period of time may impact birds just as much as exposure to medium concentrations of ammonia for longer periods.

There are several strategies for decreasing ammonia in the barn. These strategies can be used individually or in combination and can help encourage good barn air quality. These strategies include ventilation and management of the barn and litter and manure.

Ventilation acts as an in-barn air quality control, removing ammonia from the barn and bringing in clean air. This method does not, however, reduce or inhibit the formation of ammonia. Nevertheless, maintaining appropriate ventilation during all seasons will help reduce the gaseous ammonia levels in the barn and keep the litter dry. Consult with a specialist to ensure that your barn has the necessary ventilation.

Good barn management can help remedy many situations. In the case of diminishing the formation of ammonia gas,

The Premium+® laying nest is the number one selling nest worldwide. It’s high nest acceptance, minimal amount of floor eggs and use of high quality materials are reasons why many farmers worldwide favour the Premium+® laying nest.

Maximum number of first class hatching eggs

Optimal hygienic conditions

Highest possible nest acceptance

Reduces the amount of floor eggs to a minimum

For more info contact our local dealers: Avipor | Meller Poultry Equipment | United Agri Central Agri Systems | LBJ Farm Equipment

proper barn management includes ensuring that the litter or manure is not wet. Several ways to keep litter from getting wet are: Fix leaky drinkers and sprinkler systems; choose the appropriate litter; maintain a suitable barn relative humidity for the age of the bird; reduce the potential for condensation; and properly heat and ventilate the barn.

The choice of litter may depend on what is available or easiest to use. Some litter types, such as long-cut straw, may not absorb moisture as well and, as such, may be more likely to get wetter faster than other litters. A barn’s potential for condensation can be determined by establishing how well the barn is insulated and knowing the temperature of the water entering the barn in the drinker lines and how the barn is heated and ventilated.

Strategies for managing the litter and manure can be separated into two main plans of action: managing the bird and

managing the manure once it is in the barn. The formation of ammonia in the manure and its subsequent release as a gas form can be traced back to increased nitrogen levels in the manure.

Fecal nitrogen levels can increase if the bird does not properly break down and absorb the protein in the feed. This can happen if the bird’s diet features too much complex protein, if the bird is sick or if its gastrointestinal tract is not functioning properly. These issues can be remedied or prevented by balancing the protein and amino acid levels in the diet, as nutritionists do, and by maintaining the bird’s gastrointestinal health.

Another method to help prevent the formation of gaseous ammonia from nitrogen within the feces is to use components such as saponins, which are found in certain Yucca schigidera trees. Saponins have several modes of action and play a role in binding

ammonia.

They have been shown to reduce blood urea and blood ammonium ions, reduce excessive nitrogen breakdown in the ceca and bind ammonia so it stays in the manure instead of being released as gas. When saponins are used in the feed from the time the birds are placed to the time the birds leave the barn, it is possible to increase the nitrogen levels of the manure without increasing the release of ammonia to the air.

Another method to help reduce the release of ammonia into the air is to manage the manure in the barn. Acidifying agents can be used to lower the pH of the litter (below its usual 7.5 to 8.5), which will help slow down and decrease the activity of the microbes that break down the nutrients in the manure to release ammonia.

Another option is to use odour- and moisture-absorbents in the litter or manure. These absorbents, which are usually clay-based, act to either slow down the microbial activity or lower the moisture content of the litter. Saponins can also be used as a spray over manure to help bind ammonia that has been released and reduce the odour.

There may also be microbial and urease enzyme inhibitors that can be used to prevent the action of the microbes and enzymes in the manure that help to release ammonia.

All of these strategies, however, can be negatively affected by litter and manure accumulation, litter and manure moisture, bird type, barn temperature, disease challenges or a combination of these factors.

Managing ammonia release from manure and ammonia gas in the barn is important for poultry production. The creation of ammonia gas and its removal are complex topics but with a combination strategy of good ventilation, good barn management and reducing ammonia gas formation, this issue can be successfully overcome any time of the year.

The outlook is bright for this Canadian high-tech outbreak containment system – and its sister platform for flock health management.

By Treena Hein

It’s been five years since a revolutionary new made-in-Ontario biosecurity system called Be Seen Be Safe (BSBS) debuted. It was joined by its feisty sidekick – an early-warning livestock heath system app called Farm Health Monitor (FHM).

Now, the people behind these programs are using lessons they learned from poultry and pork farmers around the world to develop more powerful versions of the technology. The upgrades are set to be released this fall.

Inventor Tim Nelson first envisioned BSBS as a way to contain outbreaks and prevent them from turning into industry disasters, recording all visitors to a farm and analyzing the data in an emergency. With co-founder Joel Sotomayor, Nelson trialed BSBS in the Ontario poultry sector first, where he learned many lessons.

As a quick review, BSBS automatically gathers information on the traffic to and from farms within the system. It involves mapping the geographical boundaries of farms with a GPS technology called geo-fencing. Once it’s live, anytime a system-ready vehicle or device crosses that boundary, the BSBS software platform logs the entry, greets the visitor with a message

and notifies the farmer.

Information on all visits to a particular farm is stored for one year before being expunged. Farmers can access their online visitor logbook at any time using a secure personal login. Each farm and visitor are given system IDs and their actual identities are only accessed by authorized system administrators in an emergency outbreak situation.

In the case of an outbreak on a system farm, the program immediately analyzes the data, sets up quarantines and identified other potentially infected farms. It also sends out ongoing updates and biosecurity

guidance. However, everyone who visits the system farms, including veterinarians, feed and pullet deliverers, salespeople and so on, must be onboard.

The system first relied on a cellphone app to alert it as to when a device, person or vehicle enters or exits a farm. “Although we’ve found the cellphone app to work perfectly here in Canada on all three of the major global smartphone platforms, there have been some issues in Spain and the U.S.,” Nelson notes.

“We’re not sure if it’s a cellular coverage issue, a smartphone issue or something else, but we’ve decided that we’re going to

go another route for gathering farm exit and entry data. We’ve found a very economical new method to collect this information, involving a sensor on the farm property and a small dedicated device that will be carried by people or in the vehicle.”

This, however, does not solve another issue that BSBS has come up against in the past, including in Ontario – the fact that everyone who regularly visits farms must part of the system for it to be effective. “After working with many commodity associations, it’s become clear that they simply don’t have the authority to make sure everyone is taking part,” Nelson explains.

“We, therefore, are now working with major companies and it’s going very well. Companies can completely enforce a rule that anyone entering company properties must be on board, and that is crucial for the system to work effectively.”

Since the many pilot projects and installations of BSBS and FHM began several years ago, Nelson and Sotomayor have learned a great deal from farmers, veterinarians and others in the ag industry about how they might make both systems much more useful.

“We designed BSBS as a way to contain outbreaks, and FHM as an early warning system for identifying possible disease issues,” Nelson explains. “After much research and analysis, we’ve modified the design of both systems so that they provide much more, and can also work together.”

FHM originally was an app which allowed farmers and veterinarians to report on symptoms they observed in their birds or livestock, using word descriptions and also through uploading pictures or even short videos from their barns. The system detects if similar information is being reported from two or more farms within a given area and then sends out a blanket warning across the region, alerting farmers and vets to check their animals carefully and report

THE IMPACT OF STRESS:

• Nutrients are re-allocated from growth toward minimizing the effects of stress

• Performance can be negatively impacted HOW CHROMIUM

as needed.

“After speaking to many poultry, swine and dairy farmers, we understood that they wanted something that would do much more than let them report on symptoms and be alerted if the same things are being seen nearby,” Nelson says.

“They want a comprehensive tool to better manage the health of their flocks. They want to be able to do a barn check on a daily basis and record any symptoms, any changes in feed consumption, water consumption, keep track of what samples we take and send to the lab for analysis, test results and so on.”

While a lot of farmers keep excellent production records, Nelson notes that they don’t tend to keep flock health records in the same way – making it difficult, when faced with anomalies, to get to the bottom of the irregularity and solve it right away. “It’s not efficient to have to call up the vet

and ask for the details of what happened a few months ago,” he says. “Now, FHM keeps those records of past health issues and you can keep a record of all your mitigation efforts as well. And you can also do barn-to-barn comparisons and flock comparisons in the same barn over time.”

The upgrade was supported through a prestigious Eureka grant, and also involves integration of the BSBS and FHM systems.

This fall, BSBS and FHM will be available separately or as an integrated package. (Note that BSBS requires a ‘network administration team’ to identify any farms where an outbreak has officially occurred, thereby triggering its outbreak containment function.)

If the systems are integrated, BSBS is able to access FHM reports on symptoms and analyze other data, helping the farmer

and veterinarian build a story, as Nelson describes it, about the flock health issue and take appropriate action sooner. “Say there’s a certain symptom you have in your birds,” he says. “The system will look at whether there has been a drop in feed intake or water intake yesterday or over the last few days. Also, things like were any visitors to the farm in the days just before that? So, it builds a picture for better decision-making. And it now includes wind direction and speed data, as well as reported sightings of sick or dead wild birds and wild bird movement – important during spring and fall migration.”

Nelson adds that with these major upgrades, he and Sotomayor have recognized the importance of managing production-limiting diseases and not just outbreak management. “Over time, production-limiting diseases cost producers a lot more than catastrophic outbreaks,” he notes.

laying performance.

You’re in the business of raising healthy birds. Cumberland ventilation is engineered with fresh thinking and customized for your operation. So, you can be confident in the well-being of your environment and your flock.

Cumberland’s highest performing fan features a springloaded butterfly door with a magnetic locking mechanism for a complete seal. The flush-mount design makes it easy to retrofit over wall openings from 57.5” to 63”.

Find your local expert at cumberlandpoultry.com and customize your new or retrofit ventilation solution.

By Treena Hein

Two major developments on the egg production front are making the transition to alternative layer housing interesting.

Firstly, numerous Canadian food companies have made headlines in recent years by pledging to source only cage-free eggs – in most cases, by 2025. However, sources tell Canadian Poultry that some of those companies have since privately backed out of these commitments. A few have reportedly opted to source eggs from hens in enriched colony housing instead, perhaps driven by availability and cost considerations.

Canadian Poultry checked in with the major restaurants and retailers that have publicly declared their intentions to go cage-free. Few responded to multiple requests for comment and none would go on record as having changed their plans for layer housing. However, those companies that did respond – McDonald’s, Subway

and Loblaw – reconfirmed their cage-free commitments.

The grocer took it a step further. “Loblaw Companies is committed to transitioning all shell eggs sold in our stores to cage-free by the end of 2025,” the company said in an emailed statement. “We are also happy to report that as of January 2019, our PC shell eggs are free-run.”

One company that might be mistakenly described as having backtracked on a pledge is A&W Canada. In 2016, when companies were announcing cage-free by 2025 commitments, the fast-food restaurant issued a press release that got a lot of traction. It was widely interpreted by mainstream media as the company vowing to go cage-free within two years.

In actual fact, it was only committing to supporting research to find a cage-free housing solution that better suited its specific needs. Today, the company proudly states on its website that it still sources eggs from hens in enriched colony housing, explaining that there still aren’t enough cage-free eggs available to meet its demand and that furnished cages are a healthy, humane alternative.

The second development sure to affect Canadian egg producers’ transition away from conventional cages was revealed at Egg Farmers of Ontario’s AGM in March. At that event, chair Scott Graham made an exciting announcement that will affect egg farmers nationwide.

“Since the cost of production that determines egg prices is based on cost surveys for the predominant conventional system, we needed to develop transitional pricing to ensure fair compensation to egg farmers that are retooling, and to send the correct price signals to those making decisions about layer housing on their farms,” he said.

“A national committee to deal with that issue has settled on a differential of 11 cents and this will be the net price difference in the farm price for eggs produced in enriched housing across Canada beginning this September.”

While egg farmers in Ontario have already been receiving a 10-cents/doz. premium for enriched production since January 2017, this change is expected to make a significant difference in provinces that currently lack such a payment.

Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) explains

that as the industry transitions to alternative housing systems in line with market requirements, EFC, egg boards and industry have been collaborating to assess the cost to produce eggs. They firstly looked to account for the additional cost of producing eggs in enriched colony housing systems. In the future, the stakeholders plan to conduct a broader analysis for other production systems.

Canadian Poultry asked two major Canadian egg firms to weigh in on these recent developments – that is, how decisions on alternative housing are being affected by food company commitments, the impending national price differential and so on. Egg producer and processor LH Gray and Sons referred us to the Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council (CPEPC).

However, national egg producer and processor Burnbrae Farms did weigh in. Burnbrae is the sole provider of eggs to McDonald’s Canada, which has publicly committed to sourcing only free-run eggs by 2025. “Our customers who have committed to buying free-run eggs have stuck with that commitment and understood about the premium at the outset,” says Ian McFall, Burnbrae’s vice-president of foodservice and industrial sales.

At the retail level, McFall reports that eggs from free-run systems are not moving as well as expected. “Consumers are certainly interested in these eggs, but not as much as anticipated,” he notes. “We haven’t had any retail customers renege on their free-run commitments due to slow sales, but in general they are not making longterm commitments either.”

He adds that, “Due to the less-than-enthusiastic acceptance of free-run by Canadian consumers, at this time, most producers are retooling into enriched colony systems. At Burnbrae Farms, we are making production decisions based on demand.”

When Canadian Poultry asked CPEPC for comments from its grader and processor members, Margo Ladouceur, manager of egg sectors, explained that each of them looks at sales, forecasts what they need and makes arrangements with producers to meet those needs. That said, there are more non-conventional eggs available to CPEPC members than they have orders for.

EFC CEO Tim Lambert says his organization is watching global trends “with great interest”, as what’s happening in various other countries offers lessons for Canada. “However, unlike other countries, our transition is coordinated, systematic and looks to produce what the market demands,” he notes.

“At this time, most producers are retooling into enriched colony systems.”

“Promoting and maintaining a range of production types and egg varieties is a core focus for our industry. Central to this approach is a balanced portfolio of production methods that maintain a nimble and responsive industry and upholds consumer choice, while minimizing surpluses and shortfalls.”

Egg farmers, he adds, are choosing what type of housing to convert to based on market requirements and also their unique needs. For instance, the size and location of their farm as well as the potential need to buy new land and build new barns.

Lambert notes that, as of January 2019, the vast majority (71 per cent) of Canadian eggs are still being produced in conventional cage systems. About 14 per cent are from hens housed in enriched colony systems and 14 per cent from hens in specialty housing, which EFC defines as free-range, free-run and organic.

“This represents a slight shift towards both enriched colony housing and specialty housing since the transition [away from conventional cage housing by 2036] was announced in 2016,” he says. Lambert adds that, based on data from global research firm Nielsen, only seven per cent of Canadian retail egg demand is for eggs from hens in specialty housing.

At the retail level (putting aside organic eggs, and eggs enriched with omega fatty acid and vitamin D), free-run are the most expensive eggs. Online research with major Canadian grocery chains shows the cost of a dozen large, white, free-run eggs

It’s time to celebrate the care that goes into every Canadian egg.

The new Egg Quality Assurance (EQA) program shows your customers, right on the carton, that their eggs are produced by Canadian farmers dedicated to delivering a top-quality product that meets national food safety and animal care standards.

Visit eggquality.ca and add the EQA symbol to your cartons today!

ranges from $4.49 to $6.00, enriched colony (they are branded as ‘nest laid’ or ‘colony coop’) from $4.09 to $5.00 and conventional (battery cage eggs) from $2.00 to $2.49.

Canadian Poultry asked EFC if there is now, or will there be, a national strategy put in place to ensure that all Canadian consumers are able to buy the much cheaper (conventional cage) eggs right up to 2036. Will there be stores in certain regions of Canada that will no longer have cage eggs because the eggs in that area all happen to be produced on farms where hens are housed in alternative housing?

“The systematic and coordinated approach to transition the industry away from conventional housing is driven by customer demand and the market,” Lambert says. “This is will help ensure continued access to the eggs that consumers want and count on at affordable prices.”

He also weighed in on a strategy other countries have used to prevent egg consumption from declining due to higher prices, as more expensive alternative housing egg volumes increase while cheaper conventional egg volumes decrease. This strategy involves increasing the price of conventional cage eggs slowly – a few cents per year – so that consumers get used to higher egg prices. Lambert started by saying that egg consumption in Canada is presently increasing. “In 2018 alone, the retail sales of table eggs increased by six per cent,” he notes. “By using the market as the guide, the approach is to match the supply of eggs with demand. It is also important to keep in mind that the retailer sets the price of eggs based on what the market can bear. The biggest determinant of how much consumers pay for eggs is where and when we shop.”

CPEPC’s Ladouceur gave the processor’s view of this strategy. “it comes back to what we’ve stated before -- graders will be working with farmers and egg boards to meet the commitments on hen housing (including the phasing out of conventional housing by 2036),” she says. “They will also work with customers to ensure they have the supply of eggs they need to meet customer demand.”

Canadian researchers just a few years away from commercializing a solution for poultry producers.

By Jane Robinson

The global poultry industry takes an estimated $6 billion hit every year from necrotic enteritis (NE). Intestinal damage caused by this condition means birds don’t grow well, and current prevention and treatment approaches centre around antibiotics, which are under increasing scrutiny.

“There is a real need globally for an effective necrotic enteritis vaccine,” says John Prescott, professor emeritus with the University of Guelph’s Department of Pathobiology who spent many years working on a vaccine. “We want to prevent necrotic enteritis with ways other than antibiotics and that’s where vaccines come in.”

Canadian researchers have been focused on the pathogen that causes NE – Clostridium perfringens, which is a highly specialized bacterium that adapts to the chicken intestine. They hope to use the bacteria to develop an effective vaccine to protect birds.

Prescott and Joshua Gong, a senior research scientist with Agriculture and AgriFood Canada, have worked together to understand how C. perfringens develops in hopes of finding effective protection options. They worked on different parts of the pathogen and, ultimately, collaborated on the most promising prospect for an effective NE vaccine for poultry producers. A commercial vaccine could be expected available in as little as three years.

Gene manipulation falls short Prescott and his team set out to develop a new oral live bacterial vaccine for NE. He looked for strains of C. perfringens that they

could weaken by knocking out key genes. By deleting the selected genes, they hoped to manipulate the pathogen to deliver the desired balance of expressing the antigens that birds would need to develop immunity to the bacterium, without causing any NE damage. In vaccinology terms, a live attenuated vaccine.

The advantage of this approach would be that the vaccine would be inexpensive to produce, easily delivered in water, safe and be effective because it would grow where immunity was needed.

But what they learned in the lab was that they could produce some immunity to NE in chickens using the modified live organism as a vaccine, but it wasn’t going to be an industry solution. “We would have loved to have discovered a strain of the NE-causing bacteria that was effective in preventing NE…but we didn’t,” Prescott says.

“We worked really hard to target specific genes in the bacterium that are important for making the organism grow in the bird’s intestine that could cause immunity and not disease. We didn’t produce any strains of C. perfringens that could produce any significant immune protection for birds against NE without causing any damage.”

Around the same time, Joshua Gong and his associate Dion Lepp were looking at the NE vaccine potential of an appendage (pilus) on the surface of C. perfringens at AAFC’s Guelph Research and Development Centre. “John and I had worked together to understand how C. perfringens developed NE, and then we worked on different parts of the

bacterium in the search for an NE vaccine,” Gong says.

“In my lab, we were looking at pili, which often attach to the gut of the host to initiate disease, as a route to developing an NE vaccine,” Gong says. This approach has yielded exciting results and a promising prospect for a commercial NE vaccine for Canadian poultry producers.

“We discovered two pilus (Latin for hair) proteins on the pathogen that produced the best antibody response in a vaccine to protect birds against NE,” says Gong, who

“We are about three years away from a commercially available vaccine for poultry producers.”

stresses that Prescott contributed significantly to the development of the pilus vaccine. “We are now patenting these two pilus proteins that hold the best prospect for an effective NE vaccine.”

Gong and Lepp are talking to vaccine companies to collaborate on developing this vaccine to the next step towards commercialization, including exploring the route of administration that is the most feasible.

“I would expect we are about three years away from a commercially available vaccine for poultry producers that will offer effective protection against necrotic enteritis,” says Gong, adding he’s hopeful Canada could be the first market.

This research was part of the Poultry Science Cluster 2, which was supported by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada as part of Growing Forward 2, a federal-provincial-territorial initiative. Prescott’s work was also supported by the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, and Gong’s research was also funded by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

A roundup of the latest research reveals interesting findings.

By Melanie Epp

Across the country, researchers are evaluating lighting systems for their potential to improve growth, reproductive efficiency, health and welfare. Here are some of their most interesting observations.

Poultry are more sensitive to light wavelengths than humans. They can even sense ultraviolent (UV) light. While research is being done in UV lighting, much is still focused on monochromatic lighting, which is now possible with LED lights.