FIGHTING POTATO WART

David De Koeyer and the AAFC team offer hope for reducing the threat

LOTS OF OPTIONS. ONE DESTINATION.

Our products help you on your way to higher yield and superior quality.

Aim® EC herbicide – Tank-mix with Reglone® Desiccant for more complete vine kill, leading to better tuber quality.

Beleaf® 50SG insecticide – Reliable aphid control, unique anti-feeding action and low impact on many important beneficials*, with a short 7-day PHI.

Coragen® MaX insecticide – Residual control of ECB and CPB with a short 1-day PHI, in a new, highly concentrated formulation that covers more acres with less.

Cygon® 480-AG insecticide – Consistent, systemic control of leafhoppers, with a short 7-day PHI.

Exirel® insecticide – Systemic, residual control of sucking and chewing pests, including CPB, ECB, armyworms, flea beetles and aphids, with a short 7-day PHI.

Verimark® insecticide – Fast uptake for in-furrow control of CPB and potato flea beetle.

SPRING 2024

PotatoesInCanada.com

PESTS AND DISEASES

6 | Fighting potato wart

Research offers hope for substantially reducing threat posed by this devastating disease

By Carolyn King

FROM THE EDITOR

4 Appealing to a new generation By Derek Clouthier

RESEARCH

12 | New hope for late blight control Antioxidant selenium can help boost plant immunity

By Julienne Isaacs

RESEARCH

18 | Research on resistance to potato greening

Developing potato varieties with nongreening, low-glycoalkaloid tubers

By Carolyn King

RESEARCH

14 Poultry manure and potato early die By Jack Kazmierski

WEED MANAGEMENT

20 Left uncontrolled, weeds would cost P.E.I. producers millions: study By Julienne Isaacs

ON THE WEB

WATCH THE 2024 CANADIAN POTATO SUMMIT ON-DEMAND

CANADIAN POTATO SUMMIT

24 Canadian Potato Summit taps into industry By Potatoes in Canada

PESTS AND DISEASES

26 Beyond insecticide Courtesy of AAFC

If you missed the 2024 Canadian Potato Summit, or want to review some of the material presented by one of the four industry experts who spoke during this year’s event, the entire summit and each session is available for free online and on-demand. Visit potatoesincanada.com/summit to view the event.

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Potatoes in Canada. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

PHOTO COURTESY OF GEORGE BRINSON, NAG.

PHOTO COURTESY OF BOURLAYE FOFANA.

PHOTO COURTESY OF AAFC.

DEREK CLOUTHIER EDITOR

APPEALING TO A NEW GENERATION

One of the things that stood out to me during our Canadian Potato Summit this year was how much the industry has expanded in Western Canada over the last few years – particularly in Alberta and Manitoba.

Much of this expansion, at least in Alberta, is helped by McCain Foods making the largest global investment in the company’s history last year into its Coaldale, Alta., facility, doubling the location’s size and output.

The majority of the potatoes grown in Alberta and Manitoba are for processing purposes – making foods like fries and chips. In 2023, Alberta was the top potato producer in Canada, with an output of 32.063 million hundredweight of potatoes. Manitoba was second with 29.760 million CWT and P.E.I. third at 25.813 million CWT.

According to Canadian government statistics, 65 per cent of potatoes grown in Canada are utilized for processed foods, while 22 per cent are fresh and 13 per cent are seed.

Only two potato-growing provinces allocate a higher percentage of their tubers for fresh consumption – B.C. at 83.6 per cent (none of B.C.’s potatoes are used for processed products) and Quebec at 45.5 per cent fresh and 41 per cent processed.

I bring this up because one of the other issues that stood out to me during the Canadian Potato Summit was how the industry should be marketing itself to younger generations, like Gen Z and Millennials, who generally tend to be more health-conscious than other generations when it comes to food choices.

Though everyone loves a good helping of French fries or a bag of chips, fresh potatoes are an essential, versatile and affordable food choice for Canadian families, but sometimes gets neglected by younger consumers.

But that does not need to be the case. Mashed, roasted, boiled or sautéed, potatoes perfectly accompany various cultural dishes, from Greek, Indian and Chinese to English and Canadian.

Getting the message out about the various ways potatoes can be healthily prepared is something the industry should prioritize as the Traditional and Baby Boomer generations – which grew up with potatoes being a staple on their plates – are no longer the primary potential consumers of potatoes.

There are also new tools at our disposal to help prepare some of our beloved potato dishes. Take air fryers, for example; they provide a quicker and much healthier way to enjoy things like French fries, home fries (or hashbrowns as some people call them) and even a whole roast potato.

Though we don’t have any cooking tips in this year’s issue of Potatoes in Canada, we do have the latest in research that is aimed at helping growers produce the best and healthiest crop. Our features touch upon such topics as the latest advancements in the fight against potato wart, developing varieties with resistance to potato greening and how selenium could be used to control late blight.

We also summarize the 2024 Canadian Potato Summit, which, if you missed this year, you can check out potatoesincanada.com and watch all of the presentations on-demand.

PESTS AND DISEASES

FIGHTING POTATO WART VIA GENOMICS AND MOLECULAR TOOLS

Research offers hope for substantially reducing threat posed by devastating disease.

by Carolyn King

Potato wart is a yield-limiting, soil-borne disease that disfigures infected tubers, making them unmarketable. On top of that, the pathogen is really difficult to eradicate once it enters a field. Along with strict phytosanitary measures, Canada is tackling this threat through both potato breeding and potato wart research. And both research efforts are tapping into the power of genomics and molecular tools to speed advances.

Potato wart basics

“Potato wart is caused by a fungus called Synchytrium endobioticum. The fungus infects potatoes and causes cauliflowerlike formations and warty growths on the tubers,” explains Hai Nguyen, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at the Ottawa Research and Development Centre (ORDC). His current research focuses on molecular and genomic studies of the potato wart pathogen and other related fungi.

Nguyen notes that Synchytrium endobioticum needs a host potato plant in order to grow and complete its life cycle. Inside its host, the fungus forms resting spores, which are released into the soil as the diseased plant dies and decays. The resting spores can remain infectious for decades, waiting for cool, moist conditions and another potato plant so they can start their next infection cycle.

Potato wart is a regulated pest in many countries, including Canada and the United States. It is not a threat to food safety or human health, but it can have very damaging impacts on potato production and exports.

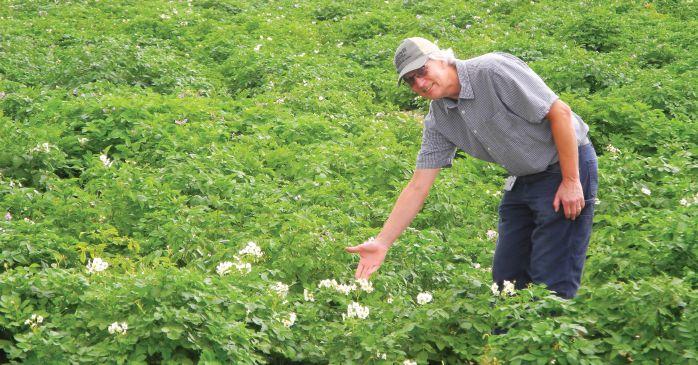

“Potato wart can cause severe yield reductions, which can make land unsuitable for potato production for a long period of time as the spores can remain dormant in a field for more than 40 years. Also, if potato wart is present, it can impact the trade [not only of potatoes but also] of other commodities associated with soil such as root crops or other plants that will be replanted,” explains David De Koeyer. He is a potato breeder and geneticist at AAFC’s Fredericton Research and Development Centre (FRDC).

“The fungus can be present but undetected in the soil for many years or even decades before visible signs are observed on the tubers. During that period

of time, a farm can unknowingly expose itself to the potato wart pathogen through the replanting of potatoes from infested fields to new locations, and there is a risk of moving the pest to other farms,” notes De Koeyer. Officials at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) add that replanting of infected potato tubers poses the highest risk for pathogen spread, while movement of infected soil and potato waste also pose a risk when mitigation measures are not in place to control the risk of pathogen spread.

“So, potato wart is difficult to detect, it is difficult to manage, and it has a lot of implications economically,” says De Koeyer.

PHOTO COURTESY OF GEORGE BRINSON, NORTHATLANTIC GLENS.

Integrated Coolant Distribution won’t save us from climate change.

Going carbon neutral is the ultimate safety feature.

Wildfire –Aug. 26, 2017 –

Photo by Mark Ralston.

Potato wart in Canada

The disease is thought to have originated in potatoes grown in the Andes of Peru and to have arrived in the United Kingdom around the 1880s and spread from there. Nguyen summarizes the history of potato wart in Canada, drawing mainly from a 1993 article by M.C. Hampson, a former AAFC research scientist.

Nguyen divides Canada’s potato wart history into three periods. “The first period covers the early 1900s to the 1950s. It begins with the introduction of potato wart into Newfoundland around 1900. The disease was thought to have come from seed potatoes from the United Kingdom. In 1909, an English botanist, who worked at the experimental farm in Ottawa, received diseased tubers from Newfoundland. He confirmed the disease was potato wart. He then helped to work on legislation to prevent entry of potato wart into mainland Canada from Newfoundland and other countries where the pest was reported. He also made a bulletin and distributed it to increase awareness of the disease.”

Over the next few decades, the disease spread in Newfoundland. By the 1920s, wart-resistant potato varieties were being imported from England for use in Newfoundland. However, by the 1940s, new races, or ‘pathotypes,’ of potato wart emerged, overcoming the resistance genes in those varieties.

Nguyen sees the second period as starting after Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949 and ending in the 1990s. During that period, Canadian scientists conducted surveys to determine potato wart’s distribution, confirming that it was widespread in Newfoundland primarily in home gardens. They also experimented with different control measures such as chemical eradication, but no eradication methods were successful.

De Koeyer notes that, starting in the 1950s, AAFC worked on developing potato varieties with resistance to the potato wart pathotypes in Newfoundland. From the late 1950s up until 1998, these breeding activities took place at the St. John’s Research and Development Centre. The St. John’s RDC established an infested field location at its Avondale sub-station in Newfoundland for evaluating wart resistance levels in the breeding lines.

According to Nguyen, the third period

starts when potato wart was first detected in Prince Edward Island (P.E.I.) in 2000. As the CFIA website explains, this detection resulted in the closure of the U.S.–Canada border for all fresh P.E.I. potatoes, including seed and table stock, for six months. At that time, the Potato Wart Domestic Long Term Management Plan was also put in place. The Plan outlines the mandatory minimum survey, testing and surveillance activities required to mitigate the risk of spread of potato wart outside of the restricted areas in P.E.I. In addition, in 2021, CFIA enhanced its National Surveillance Program with additional soil samples taken in every seed potato-producing region of Canada. The Canadian surveys have not detected the disease beyond Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) and P.E.I.

“This post-2000 period also marks the development of molecular technologies and genomics to help us deal with the disease. Those technologies just didn’t exist in the first two periods,” says Nguyen. He is one of the AAFC researchers working together with CFIA scientists and with collaborators in the Netherlands on potato wart genomic/ molecular research.

As of 1998, FRDC has taken on the task of breeding wart-resistant potato cultivars. However, the evaluations of breeding lines for wart resistance levels are still done at the Avondale sub-station, under a memorandum of understanding between AAFC and CFIA, ensuring the safe containment of diseased materials.

Over the years, AAFC has released several wart-resistant potato varieties suited to the needs and preferences in NL. And these days, it is stepping up its efforts to breed resistant varieties of market interest for P.E.I. as well.

Resistance breeding for P.E.I.

Synchytrium endobioticum pathotypes are identified using a standardized set of potato lines, referred to as differential hosts. Based on the symptoms expressed by each of the lines when inoculated with a particular isolate of the pathogen, that isolate can be identified as a specific pathotype.

“Currently in the world, over 40 pathotypes of the potato wart pathogen have been discovered. In Canada, only three have been found,” says De Koeyer. Pathotypes 2, 6 and 8 have been found in NL while only pathotypes 6 and 8 have been detected in P.E.I.

He notes, “CFIA approves resistant varieties for use in restricted fields in P.E.I. as part of the Potato Wart Domestic Long Term Management Plan. At present, five varieties – Althea, Frontier Russet, Goldrush, HiLite Russet and Prospect – are the only ones on that approved list for the wart pathotypes in P.E.I. Some other varieties are currently being assessed for resistance.”

According to De Koeyer, breeding potatoes for wart resistance comes with many challenges. One fundamental challenge is the complexity of potato genetics. “It takes a big effort to incorporate wart resistance into a potato that also has all of the other traits needed by [growers and processors]. The companies have standards that need to be met, and consumers have standards for what they want to eat,” he says.

In addition, identifying wart-resistant potato varieties is a time-consuming process involving multiple rounds of testing and requiring trained staff. And, since potato wart is a regulated pest, resistance testing has to be done either in Newfoundland where the disease is endemic or in a very

Hai Nguyen, whose research includes molecular and genomic studies of the potato wart pathogen. PHOTO COURTESY

highly contained laboratory.

As well, the potato wart pathotype composition in P.E.I. needs to be monitored to ensure that the resistance screening efforts are working with the relevant pathotypes. The low levels of pathogen infestation on P.E.I. also pose a scientific challenge for confirming the pathotypes present in some cases.

AAFC is enhancing its wart-resistance breeding efforts for P.E.I. in a number of ways, including increasing its potato wart-related capacity in NL. “We’ve been rejuvenating our Avondale testing site by increasing the available research area to approximately five acres, providing dedicated equipment for plot management, storage facilities and fencing to keep the moose out and so on,” says De Koeyer.

“We’re also working with industry to look at a greater scope of varieties, especially those that are most important to P.E.I. And we’re looking at complementary or improved methods for testing breeding lines for resistance to potato wart such as using molecular markers linked to the resistance and indoor testing under controlled conditions. Indoor testing in Newfoundland will be initiated when renovations to the St. John’s RDC are completed.”

Wart resistance genes

“We are working to characterize the different sources of resistance in our potato germplasm pool. We’ve had a long history of working on potato wart so we’ve been using our historical data as well as molecular markers to look for resistance sources,” says De Koeyer.

CFARMS_potato_WST_PotatoesinCanada_7x6-625_v1.pdf 1 2024-02-07 9:46 AM

AAFC also works with a collaborative grower in Newfoundland who has a small, infested area where a few varieties can be screened. “The field is very heavily infested with potato wart so we get a good screening, but it is very small scale.”

“We have confirmed that we have multiple sources of wart resistance available in Canada. Some of them seem to be similar to those that have been previously reported in the scientific literature, but other sources are novel.”

He adds, “It is quite an endeavour to characterize new sources of resistance.” That work includes developing large populations of different potato lines, evaluating the resistance level of each genotype and

When recycling ag containers, every one counts

Great job recycling your empty pesticide and fertilizer jugs, drums and totes. Every one you recycle counts toward a more sustainable agricultural community and environment. Thank you.

2024 COLLECTION SITES OPEN APRIL 1.

Ask your ag retailer for an ag collection bag, fill it with rinsed, empty jugs and return jugs, drums and totes to a collection site for recycling. In Alberta and Manitoba, ask your ag retailer if it’s a jug recycling location. Details at cleanfarms.ca

NEW! Return empty seed, pesticide and inoculant bags for environmentally safe management.

info@cleanfarms.ca @cleanfarms

associating the resistance with variant forms of specific DNA sequences using genomic analysis. “So, there is certainly a lot more research to do. But it is promising in that we have different types of resistance sources in different market categories.”

AAFC is also working on markers for screening breeding materials for resistance genes. “We have markers from the literature and collaborations for testing the markers. Some of these markers are effective in varying degrees for the pathotypes we have in Canada, and we’re using those to screen for resistance genes in our breeding material and some Canadian varieties,” he says.

“This work is still at a preliminary stage, but it seems that the results from the marker data are not universally good at predicting resistance [in Canadian potato lineages].”

A marker is a sequence of DNA associated with a particular gene, but it may not actually be part of the gene. So sometimes a marker may predict the gene’s presence when the gene isn’t actually there. Developing more robust markers suited to Canadian potato germplasm was recommended by the International Advisory Panel on potato wart disease management in P.E.I. in their December 2022 report and is also a priority for AAFC research.

Improving pathotyping methods

In Canada, CFIA is responsible for determining the pathotypes of potato wart isolates because it has the biosecurity facilities, procedures and trained staff essential for this work. “At AAFC, once we build up our capacity at the St. John’s RDC, we hope to help Canada with this pathotyping work,” says Nguyen.

A molecular pathotyping system could be an alternative to the time-consuming, labour-intensive current pathotyping system, which relies on the plants’ phenotypical reactions – their physical responses – to the pathogen. “The currently used pathotyping system was conceived before all of the genomics and molecular tools we have now,” says Nguyen. “The idea of a molecular pathotyping system has been around for at least 10 years, but no one has been able to pull it off very successfully.”

Nguyen and his research group at ORDC have done some work towards developing a tool for molecular pathotyping. To develop it, they sequenced the whole genomes of potato wart isolates that have been pathotyped

traditionally. Then they used machine learning techniques to identify patterns across the whole genome associated with the different pathotypes, and they used those patterns to predict probable pathotypes in other isolates.

“This approach shows promise because it looks at the entire genome, and it doesn’t rely on any preconceptions about what genes or what areas of the genome are responsible for infection. So, it might work with our current phenotypic pathotyping system,” he says.

“However, I think this approach can also be modified to work with a gene-based pathotyping system.” He thinks the best option would be to transition to such a genebased system. “There have been conversations in the scientific community that we need to figure out a better pathotyping system, and that is what we’re working on now.”

Wart genomics and molecular tools

In recent years, AAFC, CFIA and their Dutch collaborators have made progress on various potato wart-related molecular tests. For example, they developed one of the first molecular tests for the pathogen, which can detect whether the pathogen is present in a sample. Then this research collaboration developed molecular tests that can detect quantities of the pathogen, based on the amount of its DNA in the sample. And most recently, they have created tests to help detect if resting spores remain viable.

Although these molecular tests are faster and easier than traditional methods like bioassays and microscopic examinations, Nguyen cautions that even these molecular

tests can sometimes give false positives and false negatives, and they also depend on good sampling techniques to give accurate results.

Over the past decade or so, AAFC, CFIA and their Dutch colleagues have also done quite a bit of work to characterize the genomes of different Synchytrium endobioticum isolates of different pathotypes and from different locations.

“This fungus is a challenging organism to sequence and work with because it needs a host to grow. So, there are problems with getting enough potato wart DNA and with the purity of the wart DNA for sequencing,” explains Nguyen. The initial stage of their research was mainly focused on dealing with these basic hurdles so they could have sufficient, pure Synchytrium endobioticum DNA to work with.

More recently, their progress has accelerated. For example, Nguyen was part of a team that sequenced and characterized the genomes of two Synchytrium endobioticum isolates, one from P.E.I., and the other from the Netherlands. In their 2019 paper, the researchers compared those genomes to the genomes of other related fungi. Their work shed new light on important aspects of Synchytrium endobioticum’s biology at the molecular level, including how it might cause infection.

Then, in a 2023 paper, the researchers sequenced and characterized many more isolates of the pathogen, including recent isolates from P.E.I. and an international collection of historical and recent isolates from the Netherlands and other countries. This work has increased scientific understanding of the pathogen’s diversity and its migration pathways.

David De Koeyer, AAFC potato breeder and geneticist. PHOTO COURTESY

“[As part of this research] we built a website where we are able to use the molecular variation to try to track and trace the different strains that we find,” notes Nguyen. Not only does this interactive web tool allow the team to share the data from this paper, but other researchers can also contribute to expanding this track-and-trace effort. (Although the tool includes regional locational information, it never refers to specific potato fields).

His current potato wart research focuses on further improving the genome data available for Canadian isolates by sequencing more Canadian samples, mainly isolates of pathotypes 6 and 8.

Such genomic data provides the foundation for development of more advanced molecular tools. “For instance, using the genome data, AAFC, CFIA and our Dutch collaborators have been working on a new molecular tool to enhance the capture of the pathogen’s DNA,” he explains.

“The technique, called ‘target enrichment’, is particularly useful in environmental samples where there is also DNA from other organisms and where there may not be a lot of DNA from the pathogen either. In a nutshell, the tool

allows you to characterize the pathogen’s full genome even though there is a low amount of DNA or the DNA is very low quality.”

He notes, “This tool could be helpful one day, for example, in enabling us to characterize the pathotypes even in samples with low amounts of the pathogen and perhaps [identifying the pathotype faster] and at a lower cost.”

Nguyen says this new tool is just one example of a whole suite of molecular tools that could be developed. “No tool is a silver bullet, but having more tools gives us more options.”

More research, more hope

Nguyen and De Koeyer both emphasize that potato wart is a challenging issue, but advances in genomics and molecular tools offer exciting possibilities in the battle against the disease.

“Resistant potato varieties aren’t a silver bullet, but they do play an important role in the management of this disease. They have proven very effective in other countries,” says De Koeyer.

“I feel that DNA markers and genomics technology will make development of varieties with durable wart resistance even more

efficient and effective. I think it will be important to put together multiple resistance genes to make a variety’s resistance more durable.”

Similarly, potato wart genomic studies have the potential to provide further help in managing the disease. “We hope that with more genomic data and more genomic insights into concepts like the differences between the pathotypes, we can understand more about the essential pathways and essential genes in the pathogen’s infection process or its general life cycle. From there, we could look at different strategies to detect it from a different angle such as its biochemistry,” Nguyen says.

“And, if we know something about the genes involved in carrying out its life cycle, maybe we can find something that could disrupt its life cycle. Such methods might only suppress the pathogen, but if you have a multipronged strategy, then you might be able to suppress it enough that the risk is virtually next to zero.”

Although there is much research still to be done, there is also the growing hope of substantially curbing the threat of potato wart in the years ahead.

SELENIUM: NEW HOPE FOR LATE BLIGHT CONTROL

Antioxidant can help boost plant immunity.

by Julienne Isaacs

Aplant immunity booster called selenium might be a “shot in the arm” for Canadian potato producers hoping to mitigate the effects of late blight.

Selenium is a mineral that is naturally present in soils. In high doses, it’s toxic, but in low doses, it’s an essential trace element for humans and animals.

Some soils are richer in selenium than others. Atlantic Canadian soils, for example, are low in selenium, says Bourlaye Fofana, a research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Charlottetown Research and Development Centre. Across Canada, there’s a kind of “gradation” of selenium in soils from east to west, with richer soils in B.C. and diminished selenium in the Maritime provinces.

Fofana works in plant physiology and genetics in potatoes and flax. “Everything I do is related to crop quality and improvement,” he says.

When Fofana first arrived at AAFC Charlottetown in 2008,

he began to look at how soil mineral composition affected crop nutritional quality. What would happen, he asked, if he added a selenium treatment to seeds including flax, wheat, soybean and potato before planting? Would it boost the selenium content of the crop? And would that selenium be bioavailable to people eating the crop products?

When Fofana and his colleagues’ results were positive, the research continued. “We wanted to address how selenium would counteract bacteria contributing to potato seed decay,” says Fofana. “So, we were trying at that time to apply selenium solution on seed tubers in-furrow in hopes that bacteria would be reduced.”

But the researchers did not see a significant difference between seed-treated and non-treated for seed germination.

The researchers opted to repeat the experiment in the

ABOVE: Bourlaye Fofana is a research scientist at the Charlottetown Research and Development Centre.

greenhouse. Again, they didn’t find tangible significant differences in germination.

They then decided to follow this experiment with a study on late blight by looking at the effects of selenium applied as seed treatment before planting and as a foliar application after late blight inoculation, or as a foliar application only. “We found that foliar application alone was as effective as combining seed treatment and foliar application,” says Fofana.

“The data suggest that [selenium] acts as an inducer of plant defenses, while also inhibiting fungal growth,” writes Fofana and his colleagues in their publication on the results of the selenium and late blight study.

Study design and results

Fofana conducted the study in the winters of 2016 and 2017 in greenhouses at the Harrington Research Farm on P.E.I.

They used four potato varieties in the study: Superior, a whiteskinned potato, Russian Blue, a purple variety, and two diploid potato lines. Soil was sterilized before planting. Liquid formulations of selenium were applied as foliar applications before and after plants were injected with late blight, says Fofana.

In one section of the experiment, seed tubers were treated with selenium as seed treatment and plants were later sprayed with selenium foliar application before and after late blight inoculation to the plants; in another experiment, only the foliar treatment was assessed for its effectiveness as a standalone treatment.

Both seed- and foliar-treated plants showed reduced incidence and severity of disease, says Fofana, and leaves and tubers had elevated levels of selenium. The onset of the disease was also delayed. In the foliar experiment, the results were similarly promising – leaves and tubers were richer in selenium, and disease incidence was lower.

“We show for the first time that selenium treatment, using a combination of seed tuber and foliar selenium treatments or foliar selenium treatment alone, contributed to reduced late blight severity in potatoes,” the researchers concluded.

In addition, Fofana and his colleagues have conducted in vitro experiments in the lab, where they inoculated petri dishes containing different concentrations of selenium with pathogens including late blight (Phytophthora infestans), Fusarium graminearum, and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. In those experiments, selenium directly inhibited the mycelial growth of these field and post-harvest plant pathogens in Petri dishes containing 10 ppm selenium, says Fofana.

Fofana says more data is needed. It’s difficult to gather field research data on P.E.I. – there are restrictions on the release of late blight pathogens due to the large number of commercial potato operations in the region.

Studies should focus on the use of selenium as a preventative measure against naturally occurring late blight, the authors note.

Fofana says there are other questions that need to be addressed –for example, timing of application. Fofana is working with the P.E.I. Certified Organic Producers Co-operative to assess the viability of selenium for use against potato diseases in organic systems.

Selenium is available commercially as sodium selenate or sodium selenite and is cheap, says Fofana. He says producers should follow weather forecasts for rainfall and spray selenium solution to ensure maximum effectiveness against late blight like any other pesticides.

Fofana and his colleagues were looking at ways of fortifying the selenium content in crops grown in selenium-poor soils on Prince Edward Island when they made an intriguing discovery: when added to potatoes as a seed or foliar treatment, the mineral helped potatoes ward off plant diseases.

POULTRY MANURE AND POTATO EARLY DIE

Poultry litter could be key to controlling the disease that reduces potato crop yield.

by Jack Kazmierski

Potato early die complex (PED) has been a problem in North America for many years, devastating potato crops and reducing yield. “It’s caused by a soil-borne fungus, known as Verticillium dahlia,” explains Dr. Marisol Quintanilla, a nematologist working on a solution at Michigan State University.

Quintanilla explains that the fungus is able to infect potatoes on its own. However, when it gets help from a microscopic roundworm known as the Pratylenchus penetrans nematode, the infection can spread more rapidly. “The fungus doesn’t need the nematode in order to infect the plant,” she adds, “but the nematode helps because it burrows into the plant, makes a

wound, and introduces the pathogen into the plant.”

The fungus that causes PED seems to do well in cooler weather and in climates where the soil is moist. It’s a problem in the northern parts of the U.S. and Canada. “This includes Michigan, Idaho, Oregon, Washington and a lot of the states in the Pacific Northwest,” adds Abigail Palmisano, a graduate student who works with Quintanilla at Michigan State University. “These are the areas that get a lot of rain.”

When PED hits potato crops, Palmisano says that up to 50 per cent of the yield could be lost.

The infection causes wilting and yellowing in the lower parts of the leaves,

Palmisano adds, and stunts the growth of the infected plant. “And if you open a potato plant,” she says, “you’ll usually see a ring in the stem. It’s a brown discoloration of the vascular system, which is also visible in the potato tuber.”

An infected potato is still safe to eat, which means that an infected crop doesn’t have to be destroyed. The potatoes can still be harvested and sold. The problem is that the yield can be greatly reduced, which impacts the bottom line of North American producers. “The potato is an important plant for the economy,” adds Quintanilla.

ABOVE: The full lab team at Michigan State University.

PHOTO COURTESY OF LUISA PARRADO.

looking for six women making a difference in Canadian agriculture. Whether actively farming, providing agronomy or animal health services, or leading research, marketing or sales teams, we want to honour women who are driving Canada’s agriculture industry.

“So, if the yield is cut by 50 per cent, that’s a big deal.”

One of the challenges with PED, according to Palmisano, is the fact that the fungus is especially hearty. “It can live in the soil for up to 20 years, and the potato field can be fine,” she explains. “It can be sitting in wait before infecting the plants, and farmers won’t know until it’s too late. Some growers will mistake [the infection] for early maturation.”

New research

Quintanilla and her team recently received a $750,000 grant from the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture to develop and evaluate sustainable methods of managing PED. One of Quintanilla’s graduate students, Luisa Parrado, helped write this grant.

As a nematologist, Quintanilla and her team will be using the grant to fund studies designed to find ways to deal with Pratylenchus penetrans, which is the specific nematode that is instrumental in the spread of Verticillium dahlia, the fungus that causes PED.

“This grant goes a little bit deeper,” Quintanilla adds, “because we found that

some manures and manure compost had a significant effect on Pratylenchus penetrans We wrote a publication on this and we wanted to understand why this is working.”

Their goal is to find out if compost formulas can be tweaked to make them more effective at controlling nematodes.

“We found that the poultry manure blend that we were using from Morgan Composting, [a company in Michigan], was really effective at suppressing root lesions,” Palmisano adds. “We also prepared a compost blend and found that it improved the yield and reduced the incidence of tuber vascular discoloration.”

The team discovered a combination of compost and more traditional chemical herbicides and fungicides helped reduce the population of nematodes. “However, none of the treatments were able to change the population, incidence or severity of the Verticillium dahlia fungus,” Palmisano adds.

Poultry manure is key

So far, research seems to be pointing at poultry manure as an especially effective ingredient in the composts that were most successful at controlling PED. “We found that

the lowest number of Pratylenchus penetrans (nematode) within the roots and soil was from the chicken manure application,” Palmisano explains. “It also boosted the number of beneficial microbes in the soil, so we’re thinking that the treatment is killing the nematodes but also boosting the soil quality and the plants’ vitality.”

Quintanilla has a theory as to why poultry manure is most effective. “We compared the different sources of manures that we evaluated. One was dairy manure, one was poultry manure, and one was a combination of dairy, poultry and wood ash. We found that effectiveness is correlated with the level of acetic acid and butyric acid, and that chicken manure and ash had higher levels of these compounds.”

Chicken manure also had an effect on the vascular discoloration in potatoes. “So even though the fungi was still growing in the stems, there was a significant reduction in the amount of potatoes that were discoloured. The chicken manure was suppressing the speed of the growth of the fungi.”

The fungi was still there, she notes, but it would seem that chicken manure helped reduce the fungal growth, thereby preventing it from getting to the potato. “We don’t know how this is happening,” Quintanilla admits, “so we’re still looking at it. It’s a tough nut to crack.”

The secret sauce

Based on research done so far, it would seem that PED might be best controlled by the specific combination of dairy manure, chicken manure and wood ash found in a compost blend sold by Morgan Composting. Quintanilla says she shared her insights with the company owner years ago, and that he based his formula on her recommendations, which included her advice to add chicken manure in the mix.

In theory, producers could make their own blend of dairy and chicken manure, mixed with wood ash in order to combat PED, but there’s no guarantee it will work as well as Morgan Composting’s blend.

“In order to make a general statement like, ‘Chicken manure compost is effective at reducing root lesion nematode and potato early die,’ we need to be able to test compost from other companies,” says Quintanilla. “When we test other products, we will be able to make a more generalized statement that will have a more national impact.”

Example of discolouration caused by PED in a potato stem.

PHOTO

OF LUISA PARRADO.

Brought to you by DOES THE FUTURE OF AGRICULTURE SEEM GREY TO YOU?

Agriculture in the Classroom is cultivating curiosity by providing hands- on, immersive learning experiences to educate and engage students. The next generation of farmers, policy-makers, and innovators is in the classroom today. Together, we can inspire young people to drive our industry forward.

Change the future at aitc- canada.ca

RESEARCH ON RESISTANCE TO POTATO GREENING

Developing potato varieties with non-greening, low-glycoalkaloid tubers.

by Carolyn King

Bourlaye Fofana points out that greening of potato tubers has implications for tuber quality, marketability, food safety and food waste. So, he is working to develop elite potato varieties that are resistant to potato greening. Such varieties could benefit everyone from potato growers to consumers.

A brief look at the issue

“Potato greening is when the skin of the potato becomes green or darker, depending on the color of the tuber. When the tubers are white, they become green as a leaf. But when they are red, they become darker,” says Fofana, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Charlottetown.

Potato greening, also called tuber greening or potato sunburn, is caused by exposure of a tuber to light – either artificial light or sunlight. Fofana explains that this greening is the result of the synthesis of chlorophyll in the tuber and, at the same time, the formation of compounds called glycoalkaloids.

Glycoalkaloids occur naturally in potatoes and some other species of the potato/nightshade family. According to Health Canada’s website, “Glycoalkaloids are toxic to humans if consumed in high concentrations. Canadians are rarely exposed to levels of glycoalkaloids that cause serious health effects. However,

PHOTO COURTESY OF AAFC.

ABOVE: Bourlaye Fofana.

there are occasional reports of shortterm adverse symptoms….” Examples of those symptoms include a bitter taste, a burning sensation in the mouth, and nausea. More severe symptoms can occur with higher doses.

Health Canada has set a maximum level of 20 milligrams of glycoalkaloids per 100 grams of potato tuber. The greening and the glycoalkaloids occur mainly in and just below the peel, so the green area should be peeled or cut away. Since greening is associated with high glycoalkaloid levels, it impacts the marketability of potatoes.

“Having tubers go green is a significant loss in marketable yield to the producer. Potatoes that go green in the field because they are sticking out of the hill usually have to be culled right away, reducing marketable yield. A small amount of green on one end of the tuber may result in the whole tuber being culled, depending on the end use,” says Ryan Barrett, research and agronomy specialist with the P.E.I. Potato Board.

“The key factors [for potato growers] to reduce greening are ensuring enough of a hill with enough soil to cover the daughter tubers, lowering planting depth for varieties that normally set high in the hill, and keeping lights off in storages.”

However, Barrett notes, “One of the largest risks of greening is at grocery retail, where potatoes often go green if they have been sitting on the shelf too long under lights, especially if sold loose or in poly bags. This represents losses to the retailers

and a negative experience with potatoes for the consumer, who then may be more suspicious about buying fresh potatoes in the future.”

Fofana gives examples of retail practices to reduce greening such as selling potatoes in paper bags and using lower light intensities in the area where potatoes are displayed in a grocery store.

Toward greening-resistant varieties

“To my knowledge, there is currently no potato variety that is resistant to greening,” says Fofana. He adds that greening can be less noticeable on the skins of some types of potatoes, like russet and red potatoes, so they might give the impression of being more tolerant to greening than they actually are.

Fofana started his work on mutant potatoes for low-glycoalkaloid levels about a decade ago. He notes this research is a team effort, including people from AAFC who have different areas of expertise, such as potato genomics, molecular physiology, bioinformatics and breeding. As well, this research involves not only lab work but also greenhouse and field testing to evaluate the different potato lines.

In the first phase of this work, Fofana and his team used a technique called chemical mutagenesis. This resulted in a large collection of mutant potato clones.

“We looked at this mutant population to see if we could identify some potato lines with low glycoalkaloids to use in the breeding program. From that, we looked for

potential potato lines that may be tolerant to greening and are being used as models for gene editing,” says Fofana.

The purpose of this greening research is to use gene editing to put the non-greening trait in some popular potato varieties. The resulting non-greening varieties could also be made available for use by other potato breeders who want to include the nongreening trait in their breeding programs.

“Since the green colour comes from chlorophyll in the tuber’s skin and since plants need chlorophyll in the leaves to grow, the challenging thing in this research is how to identify the key genes which are involved in the greening of the tuber but not in the leaf,” he notes.

Fofana emphasizes that non-greening cultivars would benefit the whole value chain. “Currently, food waste losses due to greening – including losses at the farm gate and losses in storage, grocery stores and home kitchens – can be quite substantial, sometimes up to 15 per cent. Preventing potato greening would save money for everyone including the grower, processor, retailer and consumer. And it would also protect food safety and reduce food waste.”

“Varieties that are resistant to greening would be revolutionary for the fresh/table industry,” says Barrett.

Fofana adds, “We know that not only potato growers but also the potato industry are really expecting positive results from this research, and we are working hard to make that happen.”

LEFT UNCONTROLLED, WEEDS WOULD COST P.E.I. PRODUCERS MILLIONS: STUDY

What is the potential impact of uncontrolled weeds on potato yields?

by Julienne Isaacs

It’s an academic question – no potato producer would risk failing to control weeds that might affect productivity. But it’s an essential question because it provides a baseline understanding of the threat posed by weed pressure.

It’s also the topic of a research paper published in March 2023 by a team of Canadian and U.S. weed scientists. Titled “Potential potato yield loss from weed interference in the United States and Canada,” the paper compiles data from studies conducted between 2000 and 2018 to assess the impact of weed interference on yield.

According to Andrew McKenzie-Gopsill, a research scientist and weed specialist based at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s

Charlottetown Research and Development Centre, even though weeds “are always there, they are not always front-of-mind for producers.”

McKenzie-Gopsill is part of the Canadian Weed Science Society, which is in turn a member of the Weed Science Society of America

ABOVE: Andrew McKenzie-Gopsill and his team at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Charlottetown Research and Development Centre have been looking at the threat of weed impact on potato crops. Whether it’s “crop topping” or the vine crusher, McKenzie-Gopsill says limiting weed seeds in the seedbank is key to minimizing weed pressure.

PHOTOS

(WSSA). The WSSA’s Weed Loss Committee is systematically examining the impacts of uncontrolled weeds across crop types, he says. Along with weed scientists Peter Sikkema and Nadir Soltani at the University of Guelph, McKenzie-Gopsill helped gather data for the review on potato weed research.

“We’re trying to determine the impact [of weeds]. It gives us a good justification [for] and shows us the importance of weed management,” says McKenzie-Gopsill.

Further, the authors of the paper write, the research underscores the importance of integrated potato weed management in research programs in Canada and the U.S.

Study design and results

Researchers and extension specialists in both countries were contacted to provide data on yield loss due to weed interference, says McKenzie-Gopsill.

To qualify for the study, experiments had to include a weed-free control with greater than 95 per cent weed control, to demonstrate maximum productivity in a weed-free environment, as well as a “weedy” control where no weed control methods were applied.

“Potential yield loss for each state and province was calculated as a percentage of yield lost for each individual study, which was averaged within each year, and then averaged across the period for which data was available,” the authors of the study write.

Regional potato production data and commodity prices for the years of the study were collected from USDA and AAFC reports; the estimated potato yield loss due to weeds was then multiplied by the mean potato price from 2000 to 2018 to find the potential monetary loss in each region.

Canadian data was limited to Prince Edward Island, from studies conducted between 2000 and 2006, as well as 2018.

The study found that potential potato yield loss from weed interference on P.E.I. was estimated at 26 per cent, which translates to a potential monetary loss of US$13 million.

In the United States, the picture was even bleaker. “Nationally, in the United States, if no weed management tactics were implemented in potato there would be an estimated potato yield loss of 45 per cent, an annual yield loss of 9.1 billion kg and a farm-gate loss of US$465 million,” the authors of the paper write.

“We’re trying to determine the impact [of weeds]. It gives us a good justification [for] and shows us the importance of weed management.”

New weed management tactics

In Canada, herbicide-resistant weeds are a major concern when it comes to thinking about weed control in potato. McKenzieGopsill says research completed in 2018 and 2019 found that 50 per cent of surveyed fields on P.E.I. have metribuzin resistant weed populations. His research team is continuously reviewing newer data, and their findings are consistent with that 50 per cent figure, he says.

But it’s not just resistance that can create problems for producers. Pre-emergent herbicides are activated with moisture; in a very dry year, potatoes must be cultivated to incorporate herbicides into the soil, where they can be activated by residual soil moisture, or irrigated.

A large component of McKenzieGopsill’s work at AAFC Charlottetown is focused on sustainable integrated weed management in potato.

His program focuses on seedbank management techniques aimed at keeping weed seeds in the seedbank to a minimum.

One technique, used in-season, is “croptopping,” which encompasses any weed control technique applied above the crop. For example, a wick bar or “weed wiper,” basically a sponge soaked in herbicide, might be pulled over the field where it deposits the herbicide on weeds rising above the potato canopy; alternatively, this can be done with a mower or electric weed zapper.

McKenzie-Gopsill and his colleagues have also experimented with a suite of techniques known as “harvest weed seed control,” or HWSC, including harvest weed seed destruction using a weed seed crusher mounted on a combine.

They’ve also worked extensively on cover crop species and management as a weed control tactic.

“If you have annual cover crops, you can mow a couple of times per season and interrupt that [weed] lifecycle. Conversely, you have grasses that are tolerant of mowing – if you have some of these annual cover crops, we do quite a bit of tillage; there will be soil prep at the start of the season, [when the cover crop] is terminated and then tilled,” says McKenzie-Gopsill.

The research is ongoing, but McKenzieGopsill says it’s helpful to think about weed control in potato from the standpoint of minimizing weed seeds in the seedbank.

“Anything we can do to limit the seeds that are viable and return to the seedbank minimizes weed pressure in potato,” he says.

McKenzie-Gopsill says limiting weed seeds in the seedbank by using tools like the vine crusher is key to minimizing weed pressure.

An update on the 2023-24 crop season in Canada, as well as updates on the U.S. and European crops

Victoria Stamper, United Potato Growers of Canada

ON-DEMAND SESSIONS NOW AVAILABLE

Herbicide Injury in potatoes

Andy Robinson, North Dakota/ Minnesota extension

PRESENTING SPONSOR

Overview of AAFC’s potato breeding program and development of research outputs targeting AAFC’s four missions

David De Koeyer, AAFC National Potato Breeding Program

Insights into the 2024 potato market

Mark Phillips, P.E.I. Potato Board

SILVER SPONSOR

CANADIAN POTATO SUMMIT TAPS INTO INDUSTRY

Speakers address market, breeding and herbicide damage at fourth annual event.

by Potatoes in Canada

Potatoes in Canada held its fourth annual Canadian Potato Summit virtually Jan. 18, providing market insights and a glimpse into the latest industry research.

Victoria Stamper, general manager of the United Potato Growers of Canada, kicked off the event with an update on the 202324 crop season in Canada and a review of the U.S. and European markets. She pointed out that over the last 20 years, yields in Canada have steadily climbed despite a slight decrease in planted acreage since 2003. This has resulted in an overall increase in production, surpassing previous levels.

“This is mostly due to a number of different factors, but partly due to the constant increase in yield throughout the years,” says Stamper, highlighting that in 2023, yields in Canada reached 332 cwt/acre.

In Canada, there were 395,389 planted acres, 385,368 harvested and a production increase of 3.7 per cent last year compared to 2022. The largest increase was seen in B.C. at 33.8 per cent, followed by Saskatchewan at 22.8 per cent and Alberta at 19.6 per cent.

The steepest declines were in New Brunswick (down 12.5 per cent) and Quebec (down 10.3 per cent), mostly due to high levels of rain in the eastern region.

Alberta and Manitoba have seen the largest increase in planted acreage over the last five years.

“We expect these figures to continue to rise over the next couple of years with the planned expansion of the McCain facility in Coaldale, Alberta, as well as other developments in processing throughout North America,” says Stamper.

Comparing 20 years of potato production in Canada between the west and east, Stamper shows how western provinces like Alberta and Manitoba are surpassing P.E.I.

“They are mostly focusing on the processing sector, particularly Alberta, which stems from the continued global demand for frozen fries, which doesn’t seem to be decreasing at the moment or anytime soon,” she says.

For the processing sector, it is estimated that approximately 197,000 acres were planted in 2023 for frozen fries and around 43,200 acres for potato chips.

Potato breeding

Potato breeder and geneticist with the AAFC’s national potato breeding program, David De Koeyer, says the work he has been doing with his team helps to develop new knowledge and enabling tools for crop development, including new breeding techniques.

De Koeyer says the AAFC has been working to update its breeding pipeline, so the breeding process is now initiated by hybridization to generate botanical seed, which is then grown in a greenhouse. Seeds are evaluated and multiplied in year two, with preliminary trials in years three and four and the implementation of DNA markers. National trials take place in years five and six of the breeding process.

“Once a good selection is identified, these selections go into industry trials and eventually are released as varieties and into the seed system,” says De Koeyer.

As a result of De Koeyer and his team’s work at the AAFC, several varieties have been recently released in Canada, the U.S., and worldwide, including most recently AAC Garnet and AAC Red Fox, as well as AAC Mulberry this year.

Herbicide injury

Joining the summit from the U.S., Andy Robinson, extension

potato agronomist at North Dakota State University and the University of Minnesota, says the number of herbicide injury problems in potatoes appears to be growing, but questions whether that could simply be because it is noticed more often.

“Either way, the reality is there are some problems from time to time; it’s not widespread, but when a grower does have a problem, it’s a big deal,” he says. “As a result of herbicide issues, we can have poor emergence and disrupted plant growth, and ultimately, that’s going to affect your yield as well as your tuber quality.”

There are a number of reasons herbicide injury can be a problem, including reduced stand, slow canopy closure, damaged leaves, malformed tubers, reduced yield and quality and unacceptable compounds.

Herbicide injury happens when a grower’s soil or plants are exposed in some way, making it difficult to determine the source of an injury when it is found and not knowing what to do if there is a positive confirmation of injury due to herbicide.

“There are certain techniques you can use when it’s in the soil, like trying to look for patterns,” says Robinson. “Usually, a soil-borne herbicide or residue is going to be throughout the whole field.”

In addition to soil carryover, the primary ways crops get exposed to herbicides are by seed contamination, particle drift, contamination of spraying equipment, volatilization and misapplication.

Other issues can also mimic herbicide injury, causing the leaves of the plant to appear to have suffered from herbicide. These issues include drought stress, causing reduced growth, fertility stress, resulting in discoloured leaves, potato virus Y and phosphorous acid.

Tuber cracking can also be a sign of herbicide damage, but can also be caused by environmental stress, nutritional imbalance, disease or genetics.

“When we’re showing herbicide injury from a lot of different types of herbicides, most of the time, you’re going to cause some kind of stress to that plant, which is going to affect the tuber, and so you’re going to get tuber cracking and malformations of the tuber,” says Robinson. “It just disrupts the growth. The only time you may not see it so much is if the rate [of the herbicide] is extremely low or if it happens very late in the season when the growth of that plant is almost finished.

“Cracking is a symptom, but it’s a symptom of multiple things, so you just have to be careful.”

Looking forward

Wrapping up the summit was Mark Phillips, a marketing specialist with the P.E.I. Potato Board, who, in addition to addressing production numbers from across the country, looked at how the industry can encourage younger generations to consume potatoes like their parents and grandparents have.

Looking back to 2011, when Stats Canada stopped tracking consumption data for potatoes, Phillips says there was concern over a decrease in fresh potato consumption.

Overall in Canada, 63 per cent of households purchase potatoes, second only to bananas and apples. Sixty-seven per cent of females eat potatoes, while 59 per cent of males are consumers. Household penetration is also much higher in the eastern part of the country than the west.

“If you look at the 65-plus age group, 76 per cent of them are eating potatoes, and it just kind of slowly declines as people get younger,” says Phillips. “It’s one thing we really

need to keep in mind, that as the population continues to age, we’re going to lose valuable consumers we’ve had for years, and it doesn’t seem like the younger population is going to pick up where we left off.”

Accumulating stats from various sources, Phillips says younger people are moving away from eating potatoes because of more adventurous meal options, the convenience of those varying meal choices, urban living (people in cities eat out more often), misinformation about the nutrition of potatoes, diet trends, sustainability concerns and some of the unhealthy ways potatoes are offered, such as fries and chips.

“[Gen Z] are more interested in their food, where it comes from, how it will impact their health and the planet and how it aligns with their values,” says Phillips. “They have headstrong values and they stick to them. They have growing purchasing power and as that older generation ages out of the marketplace, they are going to take their place and we need to meet them in the marketplace.”

Don’t forget to view the full presentations from the Canadian Potato Summit at potatoesincanada.com.

Content Solutions

PESTS AND DISEASES

BEYOND INSECTICIDE

DR. CHRISTINE NORONHA. COURTESY OF AAFC

How wireworm behaviour gives clues to managing their population.

Wireworms are a common potato plant predator, living in soil and feeding on roots. They are notoriously difficult to control, and populations are increasing in farm fields across Canada causing major economic losses to farmers each year.

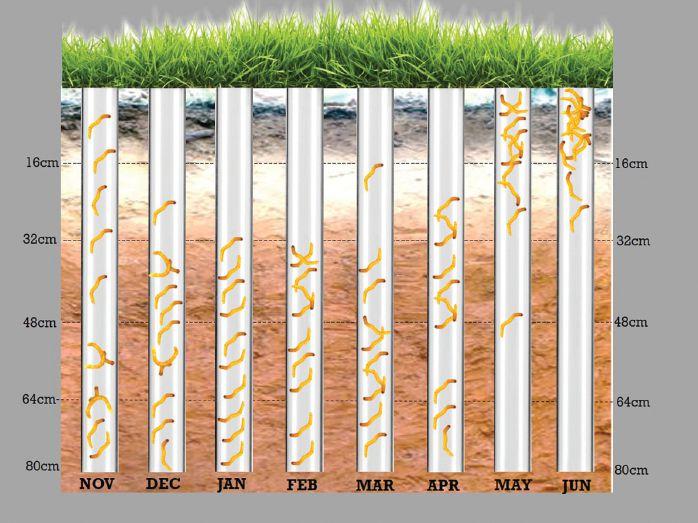

Dr. Christine Noronha, a Charlottetown-based Entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), wants to make wireworms squirm and even scram. For years, Noronha has been studying the behaviours of wireworms to see how they move around in soil and burrow in the winter. Knowing these key behaviours have helped her team develop management strategies for farmers to reduce populations feeding on potato crops, beyond just spraying insecticide.

“Many insecticides we’ve studied are inefficient at controlling wireworm populations to reduce damage to potatoes, and farmers have requested more alternative management strategies that help suppress these pests,” says Noronha.

These strategies include spring plowing, the use of rotational crops and finding the optimal timing of insecticide application and baiting. Noronha recommends not planting in a field that was in continuous sod for many years. Buckwheat or brown mustard can act as a bio-fumigant, so planting these crops at least one or two seasons prior to planting potatoes will reduce wireworm populations. These crops can be mowed, incorporated into the soil, or harvested – all options will provide wireworm control. If harvested, they can be used as a secondary cash crop for farmers.

Noronha has also investigated how wireworms move in search of food sources and how deep they travel into the soil for warmth in the winter. This work, which took place at the AAFC Harrington

Research Farm on Prince Edward Island, utilized underground vertical tubes filled with soil. She discovered that wireworms could travel long distances in search of potato roots and pinpointed how wireworms move throughout the year, including when they resurface, which is precisely the right time to monitor the population in the field. Noronha recommends that the best time to bait for wireworms is in May and June, and from mid-September to mid-October. These periods are when the wireworms are most actively foraging for food.

In a recently concluded study to see how wireworms survive under sub-zero temperatures, Noronha placed wireworms in a freezing chamber at the Charlottetown Research and Development Centre. As it turns out, wireworms are resilient little pests. On average, they can survive temperatures from -7 to -12 degrees Celsius.

One wireworm even survived up to -20 degrees Celsius. Typically, soil temperatures on Prince Edward Island do not dip below -7 degrees Celsius, and that’s in a very cold winter. Even worse, wireworms spend the winter protected deep in the soil and can live without food for months. With winter temperatures on the rise, Noronha expects wireworm populations to remain high, so the more management tools available to farmers, the better. In winter, many Canadians dream of milder temperatures. However, potato producers just might welcome colder weather if it means more successful wireworm control.

To help farmers in the fight against wireworms, Noronha and her team will be launching a series of presentation videos on different topics related to wireworm management including their behaviours, trapping, control methods and more.

Wireworm movement in the winter.

PHOTO COURTESY OF AAFC.

There’s nothing abstract about innovation

At Bayer, innovation like this AI image, drives us forward. New Emesto ® Complete seed-piece treatment offers fungicide and insecticide protection in one convenient package. It delivers excellent control of fusarium tuber rot and seed-borne rhizoctonia along with strong insect control from a new and improved formulation of clothianidin, ensuring your potato crop is protected from the start. With new Velum ® Rise fungicide/nematicide you benefit from excellent control of soil-borne black scurf, stem and stolon canker caused by Rhizoctonia solani, helping you maximize your marketable yield potential. Help make sure your potatoes can be picture perfect.

PRODUCTS

ALWAYS INNOVATING ALWAYS EVOLVING ALWAYS FINDING

A BETTER WAY

FCC is proud to offer financing and knowledge to people with one eye on today and another on tomorrow.

People like you.