WATER, WATER EVERYWHERE

Optimizing water-use efficiency in Alberta’s irrigated potatoes

Next-gen potato protection is here. Miravis® Duo is a clear level up on foliar fungicides, offering improved early blight control and extended, broad-spectrum disease protection. So now, you can take potato quality from 8-bit pixelated—to crisp, clear HD. No cheat codes required.

AND DISEASES

6 | Breeding resistance to Colorado Potato Beetle

Potato breeding innovations are speeding up breeding efforts.

By Julienne Isaacs

Stefanie Croley

Funding and new research bring optimism for better water-use efficiency.

By Trevor Bacque

18 | Golden opportunity for the adventurous

Growing spuds in the north is not for the faint of heart.

By Madeleine Baerg

Julienne Isaacs

Alex Barnard

Trevor Bacque

THE WEB

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

SHARE YOUR STORY

In the absence of live events this past year, virtual platforms have become an important way to keep a pulse on what’s happening beyond our own four walls (or fields). A webinar or web conference doesn’t replace the human connection we feel at an in-person conference or trade show, but it’s darn close – and if you were one of the nearly 350 growers, scientists or industry members who registered for our inaugural Canadian Potato Summit, I’m sure you’ll agree.

We at Potatoes in Canada created the Canadian Potato Summit in an effort to share research, hold important conversations and bring the industry together, if only virtually. On Feb. 3, attendees of the Summit were treated to research updates on Potato Early Dying, a potato breeding report from the University of Guelph, and a lively discussion featuring four members of the United Potato Growers of Canada.

I had the pleasure of hosting the event, and while all of our speakers were engaging and relevant, the final panel of the afternoon stuck with me for several days after. With panellists from different provinces and sectors of the industry, the discussion shed light on some of the challenges that growers have faced in the last year – the pandemic, of course, being the largest, with weather a close second. But there was a recurring message that seemed to resonate with each of the panellists and the audience alike: everyone in the industry has a role to play in telling the story of Canadian potato production. It’s easy to keep your head down and do your job, assuming that consumers know all about your efforts. But as Terence Hochstein of the Potato Growers of Alberta noted, Canadian growers produce world-class, safe food, and now more than ever, it’s important to bring that message to the forefront.

I know what you’re thinking. It’s a great point, but it’s easier said than done. So, start small. Join your provincial association and attend a meeting. Get on Twitter and share photos of your farm and operation. Chat with someone in a grocery store (from a safe distance, of course) when you see them comparing different varieties. Know that your role and reach within the industry extends beyond your fields.

In case you missed it, we recap some of the event’s highlights on page 14 – but you can also visit potatoesincanada.com/summit to register and watch a recording of the live presentations. And for another virtual learning opportunity this spring, you can also register for the upcoming Ontario Potato Webinar Series, to be held March 4 and hosted by the Ontario Potato Board, at potatoesincanada.com/webinars.

Best of luck for the coming season.

Your crop is your masterpiece.

We just bring the tools. The unmistakable red formula of Emesto® Silver fungicide seed treatment protects your potato seed-pieces from seed and soil-borne diseases. With two modes of action against fusarium, it even safeguards against current resistant strains. And what insecticide you choose to combine it with is completely up to you – because when it comes to art, the artist always knows best.

BREEDING RESISTANCE TO COLORADO POTATO BEETLE

Potato breeding innovations are speeding up breeding efforts.

by Julienne Isaacs

Whenever children visit Agriculture and AgriFood Canada’s Fredericton Research Station to glimpse potato research scientist and breeder Helen Tai’s program, she always asks them, “Do you have any wild relatives?”

After the inevitable “Yes!” Tai’s rejoinder – “Well, potatoes have hundreds!” – summons a vision of a long table lined with jostling spuds.

What it actually means in practical terms is that potato breeders like Tai have a wealth of resources from which to draw as they develop new and better varieties.

At the top of the list is Colorado Potato Beetle (CPB) resistance. The insect pest is widespread in every potato-growing region, and in Canada it is the industry’s top pest. But overreliance on chemical insecticides has the negative result of selecting for insecticideresistant populations of CPB, further compounding the problem.

“A key thing we have to remember about the beetle is that it’s dynamic and adaptable,” Tai says. “Even if we come up with one strategy for resistance we always need to have more strategies to

integrate. We’re always on the lookout for diversifying the genetic variation so that we have more sources of beetle resistance.”

One promising source is the large pool of wild relatives in the Solanaceae family.

More than 30 years ago, AAFC’s research program obtained germplasm from more than 200 wild relatives of potato, Tai says.

Over the years, this material has slowly been integrated into the breeding program. Some of these species naturally exude a beetlerepelling chemical in the leaves; Tai’s work has involved breeding this quality into new varieties.

Diploid potatoes

Many of the wild species are diploid potatoes, meaning they have two homologous copies of each chromosome, versus tetraploid potatoes, which have four homologous copies of each chromosome.

ABOVE: Helen Tai says it’s advantageous to look at diploid breeding for CPB resistance so we can regularly introduce into our breeding lines different sources of beetle resistance, to keep ahead of the beetle’s adaptation to resistance.

Breeding tetraploid potatoes is a long and complicated process due to the sheer number of potential combinations in the progeny, Tai explains. “As a breeder, you have a low capability of predicting what will happen in the crosses of a tetraploid.”

Breeding diploid potatoes, on the other hand, is a far more efficient process. Diploid potatoes can be outbred, by crossing two parents with different genomes, but there is another option, Tai says: inbreeding diploid potatoes to make their progeny more genetically homogeneous – and predictable.

“For us, it’s advantageous to look at diploid breeding for CPB resistance so we can regularly introduce into our breeding lines different sources of beetle resistance, to keep ahead of the beetle’s adaptation to resistance,” she explains.

This isn’t as simple as it might seem. To combine all the qualities required by the industry into a new potato variety – yield, processing quality, colour, and drought, disease and insect pest resistance – wild genetic information has to be combined with modern genetics from tetraploid potatoes.

Tai says there are various ways to do this. One is to use a haploid inducer line. A haploid is a cell with a single set of chromosomes. Crossing a tetraploid with a haploid inducer produces a diploid tetraploid that can be crossed with the wild species.

“This takes two crosses rather than a single cross,” Tai explains. “But now we have the materials necessary to move forward in breeding diploids. This requires inbreeding the lines.” Once you have inbred lines, you can cross them, and the crosses are predictable: alleles are fixed at all points of the genome. That predictability reduces the

length of the breeding process by half. Her program has released a new, CPBresistant variety called F14085; in Canada, new varieties have to be “adopted” by interested parties who then license (and name) the variety and release it to growers.

So far, neither CPB-resistant variety from Tai’s program has been adopted, but AAFC has partnered with Washington State University to do further tests with F14085.

Industry interest

Tai says the industry is slow in general to adopt new varieties for certain market classes, especially French fry processing, which is partly a function of the length of time it takes for new varieties to hit the market.

“Russet Burbank was developed 100 years ago and is still used in French fry processing. In order to shift processing away from that variety and toward varieties with CPB resistance and other traits, we need to find a better breeding process,” she says.

This also comes back to consumers, who have a specific idea of what French fries should look like, which narrows the criteria in terms of what types of potatoes can be released into the marketplace. Tai and her colleagues work hard at listening to industry representatives and grower groups about their current and future needs.

“We like to have a channel open with growers so they can understand what’s feasible on our side and what we’d like to see happen in terms of changing the breeding system to make it more responsive, and how we can incorporate more of what they’re interested in,” she says. “We want breeding programs to work better for growers.

“How do we foster new variety adop-

tion; how do we get more interest in adoption? This is a missing piece for us, and we need to discuss it with the community.”

Tracy Shinners-Carnelley is vicepresident for research and quality at Peak of the Market, an agricultural co-operative in southern Manitoba, and a representative on several national and provincial research councils. She says the arrival of CPBresistant varieties on the market will be hugely important for producers.

“History has shown us that CPBs have the ability to eventually develop resistance to whatever insecticide they’re exposed to –it’s just a matter of time,” she says. “In Canada we’re seeing resistance developing to the neonicotinoid class of chemistries.”

Roughly 20 years ago, when neonicotinoids (or neonics) were new, growers achieved “phenomenal” control of insect pests, and the chemical class changed the industry’s approach to control.

These days, growers are seeing “variable responses” to neonics and other classes of chemistry in southern Manitoba, ShinnersCarnelley says. “Insecticide resistance will always be a challenge even if newer chemistries are developed. That’s one reason we need genetic sources of resistance.”

The fate of neonics in Canada is also in doubt: Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency is currently re-evaluating use of this chemical class in agriculture, with a decision expected in early 2021.

“Whether we’re losing neonics or seeing performance decline through resistance, growers need other ways of managing beetles,” she says. “Beetles will always be a problem so it’s going to take an integrated approach to management. Hopefully the genetic component can come with it to offer a level of protection.”

Eight years ago, Peak of the Market started a project evaluating new potato varieties for the fresh market, which typically has greater flexibility in terms of introducing new varieties – although agronomic and quality standards are just as high. ShinnersCarnelley says growers are always interested in new varieties and will watch the development of CPB-resistant varieties closely.

“When it comes to management of CPB, they’re interested in anything that will help,” she says. “Obviously a variety with good beetle resistance has to have good market qualities, so it’s the challenge of getting both. It’ll take innovation in both varieties and chemistries to manage this going forward.”

Colorado potato beetle is widespread in every potato-growing region, and in Canada it is the industry’s top pest.

MORE SPUDS. LESS BUGS.

Maximize quality and yield with early-season insect control.

Getting potatoes off to a healthy start is critical to a successful finish. That’s where Titan® comes into play. It’s the seed-piece insecticide that delivers superior, longer-lasting control of major aboveground pests like aphids, Colorado potato beetles, flea beetles and leafhoppers. And in addition to providing the broadest spectrum of protection available, Titan also helps reduce wireworm damage. So go big. Go with Titan. To learn more, visit agsolutions.ca/horticulture or call AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273).

follow

directions.

WATER, WATER EVERYWHERE

Funding and new research bring optimism for better water-use efficiency.

by Trevor Bacque

One key reason potatoes in southern Alberta thrive is because of the region’s robust and expansive irrigation network. A total of 70 per cent of Canada’s irrigation infrastructure can be found in Alberta. Southern Alberta lays claim to about 80 per cent of the province’s irrigation network: about 566,000 hectares, all of which is inside the South Saskatchewan River Basin. Another 20 per cent, or 125,000 hectares, is found on private land.

Active since the late 1800s, the irrigation network of southern Alberta is one of the country’s major agricultural success stories.

In October 2020, the United Conservative Party announced a massive $815 million stimulus to southern Alberta’s irrigation districts through increased storage capacity, water use efficiency and water security, and offered the potential of bringing marginal land into production. It is also said to help create 8,000 permanent and temporary jobs as a result. At the announcement, the province’s Agriculture and Forestry Minister, Devin Dreeshen, spoke with enthusiasm about the news.

“This visionary investment in agriculture is made possible thanks to the partnership between Alberta’s government, the

[Canadian Infrastructure Bank] and irrigation districts,” he said.

A recent project by Lethbridge College, dubbed Towards Climate-Robust Irrigation Water Management for Potato Production, continues on to further help southern Alberta farmers. The research is funded through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership.

A key focus of the project is to determine if precision irrigation will drive water use efficiency as well as potato yield. One key participant on the project is Willemijn Appels, the Mueller Applied Research Chair in irrigation science at Lethbridge College.

She believes the province’s long-term outlook to help potato farmers will be of critical importance.

“The overarching idea is that we won’t get more water,” Appels says. “If you want to take the risk of growing more potatoes, you have to be quite sure that you have enough water throughout the summer to irrigate the potatoes.”

With better water storage and management upstream, it will

ABOVE: Recent funding from the United Conservative Party is set to improve the current irrigation infrastructure of Alberta, primarily in the southern area of the province.

“There’s never been, in 50 years, this much investment going forward in the irrigation sector. It’s needed. The province needed it . . . It’s not going to happen overnight. It’s going to take 10 [to] 15 years for all this to fall into place.”

likely give farmers more options to better utilize variable rate irrigation (VRI), something Appels is currently studying with her team of current students and recent graduates. With the VRI technology attached to

a pivot, which can cost up to $100,000, a farmer can control every single sprinkler and determine how much water is going to come out of each one. The main issue, however, is how beneficial VRI could be in southern Alberta potato fields.

“It is really difficult to know: what is the benefit of variable rate irrigation?” Appels says. “We don’t completely know where that baseline is.”

As potatoes are very sensitive to water availability, Appels and her team are currently working with five area farmers to help better inform her research. She and her team study topography, relative soil moisture content and other variables.

Appels’ research wraps up in two-years’ time, by which point she hopes to be able to show potato farmers in southern Alberta her research in the form of a flow chart. The intention is to help farmers assess if VRI or site-specific irrigation management would benefit them given the topography,

In 2021, recycle every jug

Our recycling program makes it easier for Canadian farmers to be responsible stewards of their land for present and future generations. By taking empty containers (jugs, drums and totes) to nearby collection sites, farmers proudly contribute to a sustainable community and environment. When recycling jugs, every one counts.

Terence Hochstein, executive director of the Alberta Potato Growers, believes that expansion of irrigated acres and general long-term improvements to the infrastructure will be a net benefit for potato farmers.

soil types and equipment of their fields.

“I would also like to be able to make a regional assessment that looks at where in southern Alberta would make the most sense to start investing in VRI or spatiallydistributed water management.”

One key piece of the province’s latest funding announcement is the creation of more storage through reservoirs. With most snowpack melt occurring in the months of May and June, the warmest and driest months are July and August. To

compound matters, Alberta’s watershed agreements means that half of the water that flows through southern Alberta’s irrigation districts must be sent east into Saskatchewan and Manitoba. It’s a good thing at the wrong time.

“The idea is that by holding onto it higher up in the watershed, that will improve the water security of farmers downstream,” she explains, adding that the additional conversion of open canals to pipelines will also be a large benefit for the region’s farmers.

Her assessment of water storage is in lock-step with how Terence Hochstein, executive director of Alberta Potato Growers, views the situation, as well.

“By improving efficiencies, we can utilize that water better and not contribute to the flooding out of downtown Winnipeg,” he says. “It is a problem we can’t control. It is coming whether you’re ready or not in the spring. It happens over a short period of time. If we are able to produce more offstream storage, we can capture that and use it in July and August and still reach our share agreement.

“There is never going to be more

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE POTATO GROWERS OF ALBERTA.

Irrigation in Alberta is set to receive a big long-term boost thanks to a recent $815 million stimulus from Alberta’s provincial government.

Willemijn Appels, the Mueller Applied Research Chair in irrigation science at Lethbridge College. Her team will determine the best use of water for potato irrigation for maximum efficiency and the true potential of variable rate irrigation.

water in the South Saskatchewan [River]. Depending on your position on climate change, there may be less.”

Hochstein says 145 potato farmers in Alberta look after approximately 60,000 acres of the crop, with many situated in the south, and the idea of expansion is ultimately a good thing.

“There’s never been, in 50 years, this much investment going forward in the irrigation sector,” he says. “It’s needed. The province needed it. There are some 40 specialty crops grown in southern Alberta. It’s good news for everybody. It’s not going to happen overnight. It’s going to take 10 [to] 15 years for all this to fall into place.”

Hochstein believes the upgrades will be focused on a handful of specific districts, including the Taber Irrigation District, the Lethbridge North Irrigation District and the Eastern Irrigation District.

According to Hochstein, this could ultimately help drive yields and give farmers a longer crop rotation for potatoes, which is currently once every three-to-five years in fields. With additional acres potentially coming into play, it could push that frame out to as many as one-in-seven and substantially expand farmers’ rotations.

“It’s been proven in the past that the longer your rotation, the higher your yield,” he says. “The longer the rotation, the better for land and grower. It gives opportunities to grow other crops, too.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF ROB OLSON.

PREPARING FOR THE COMING SEASON

The Canadian Potato Summit armed producers with the tools and information needed to kick off a successful growing season.

by Alex Barnard

On Feb. 3, nearly 350 people joined the inaugural Canadian Potato Summit, a virtual event covering the latest in potato research and industry updates.

The Summit was developed by Potatoes in Canada to fill the gap left by cancelled potato industry events due to the COVID-19 pandemic. BASF Canada Agricultural Solutions, Eco +, Farm Credit Canada and Syngenta were gold sponsors for the Summit; Bayer CropScience and Tolsma USA provided silver sponsorships, and NutriAg was the Summit’s bronze sponsor. The Summit was also supported by Ontario Creates.

The latest on CanPEDNet

Dr. Mario Tenuta and Dr. Dmytro Yevtushenko kicked off the Summit with an update on the activities of the Canadian Potato Early Dying Network (commonly referenced as CanPEDNet), formed in 2019. Tenuta, the project’s lead researcher and professor of applied soil ecology at the University of Manitoba, and Yevtushenko, research chair in potato science and associate professor at the University of Lethbridge, are two of the 16 researchers involved in the nationwide CanPEDNet.

Potato Early Dying (PED) complex causes premature plant senescence – in other words, the plant fails to reach maturity and eventually dies. This can have a significant yield impact. It’s also a very difficult disease to manage, as it is caused by a complex of pathogens and no potato cultivars currently registered in Canada are fully resistant or tolerant to PED.

Verticillium dahliae, a soilborne fungus, is the main pathogenic cause of PED; V. albo-atrum can also cause PED. The severity of V. dahliae infections is amplified when combined with the root lesion nematode Pratylenchus penetrans. On the Prairies, P. penetrans has not been found, but 30 per cent of fields contain P. neglectus instead.

From trials of new commercially available PED control products, Yevtushenko indicated that, while some lowered levels of Verticillium spp. or P. penetrans following application, soil pathogen levels often recovered later in the growing season. Soil treatments could significantly improve yield, but this is dependent on pathogen levels in the soil. Yevtushenko also highlighted the importance of soil testing to understand what pathogens are present and in what quantity.

Tenuta discussed several Network projects. One involves a survey of Verticillium spp. and root lesion nematode species and population levels, and how they relate to PED and yield. Another project is examining the effects of other soilborne pathogens associated with PED, including Fusarium spp., Pythium ultimum (a cause of root rot),

and Rhizoctonia solani (cause of black scurf and stem canker).

Difficulties created by the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the research activities of CanPEDNet. Tenuta hopes that the 2021 growing season will allow the team to resume research trials on a more substantial level.

Tenuta also emphasized that, while no varieties are fully PEDresistant or tolerant, different potato cultivars have different levels of susceptibility. As the late tuber bulking stage is when potatoes are most susceptible, Tenuta said, “The earlier you harvest your potatoes, the less you will see of a yield suppression.”

Potato breeding update

Vanessa Currie, a potato researcher in the University of Guelph’s plant agriculture department, presented on the potato breeding activities taking place at the university. The University of Guelph’s potato breeding program is responsible for development of the Yukon Gold potato, thanks largely to the efforts of Gary Johnston.

The pandemic also affected research activities at the University of Guelph. Currie said research was suspended at the university in March and April; after that, researchers were required to request special permission with a detailed plan for safe working conditions in order to conduct research in 2020. While the Potato Research Program did secure permission, their activities were reduced.

Part of Currie’s presentation was dedicated to early generation selections. She emphasized that the selection process is stringent

ABOVE: A screenshot from the United Potato Growers of Canada industry update panel, featuring the four industry representatives and Stefanie Croley, editorial director, agriculture (left).

A FERTILE HISTORY

Yara’s specialized products give Canadian potato growers a competitive edge.

From bone meal to high-tech coating technology, crop nutrition evolved during the 20th century. Innovation by fertilizer suppliers continues into the new millennium as research and knowledge about fertility advances. Canada’s highly competitive and nutrient-consuming potato production industry relies on the powerful support of companies investing in its success.

Meeting industry standards for consistent tuber size and quality keeps growers fine-tuning their production practices from inputs to harvest management. The key to success lies in ensuring the health of the potato crop begins with planting into healthy soil and using a fertility program that is well-considered. Along with soil tests and precision application, determining the best fertility program is often done with the assistance of soil nutrition specialists and crop advisors.

Celebrating 75 years in 2021, Yara North America has decades of experience meeting the fertility needs of Canadian soils, while offering one of the most comprehensive lists of potato fertilizer product options for producers in all growing areas of the country. Yara Canada’s team of crop advisors works closely with retailers to help potato producers succeed.

“We have about 18 team members across Canada who work strictly on crop nutrition,” explains Bill Dunbar, the company’s vice president of sales and marketing. “We take our global knowledge and bring it to the local level with the help of retailers. We are big believers in on-farm field-scale trials. This helps us tailor our

fertilizer products to growers’ needs.”

In addition to the main nutrient needed by every crop, Yara’s TopPotato solution includes a recommendation of other nutrients based on specific needs, such calcium, magnesium, boron, copper, manganese, zinc and molybdenum. These micronutrients are combined with nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and sulphur to create the correct nutritional mix for successful potato production. Crop nutrition experts use specific insights to help build a solution unique to a grower’s crop, ensuring the necessary nutrients are delivered effectively and efficiently.

“The TopPotato program is a crop solution for potato growers to help them get higher yields and grow better quality potatoes,” Dunbar adds. The company employs more than two dozen researchers to work on crop nutrition, and they, in turn, collaborate with colleagues at universities to ensure cutting edge recommendations make it quickly to potato producers. According to Dunbar, the company develops its crop production solutions using its own products as well as those of other fertilizer organizations.

Yara’s commitment to the success of

Canadian potato production is rooted in a history of providing fertility products to this country. For 75 years, a milestone the company is celebrating in 2021, this Norwegian fertilizer provider has positioned itself as a reliable supplier in the North American market.

“We do try to capture a lot of the international knowledge we have and bring it to the Canadian market,” Dunbar explains. “We are also working on technology to minimize our carbon emissions at our manufacturing facilities, and we are considering how fertilizer is moved to reduce our carbon footprint.”

Dunbar is proud of Yara’s continuing commitment to building a sustainable, food-secure future. “We follow 4R nutrition stewardship, and we ensure our products work with current technology,” he says. “Yara has brought many new, innovative products, such as micronutrient coating technology, to the market in an industry that is not known for its innovation.” He adds that many of the products designed specifically for potatoes are combined with nitrogen and sulphur to ensure potato crops do not suffer these two common deficiencies.

Packaged in dry and liquid formulations, products listed under the TopPotato banner are one ingredient in a recipe for success when combined with proven varieties, successful weed and pest control choices, diligent crop rotation, tillage that minimizes erosion and compaction, and responsible water management. For example, YaraVita PROCOTE products provide boron, zinc or manganese as liquid suspension coatings evenly covering each fertilizer granule. In addition, the company developed foliar sprays to give mid-season fertility boosts. Yara is known for its YaraLiva Calcium Nitrate fertilizers sold in dry and liquid formulation. These products are highly soluble and provide nitrate and calcium nutrition to crops.

In any season, where more than 250 farm-scale trials of its products are tested, Yara is able to fine-tune the formulations to make them even more useful in the many varied potato-growing areas in Canada. Yara’s products are tested on real farm applications in Eastern and Western Canada and Dunbar says, by working directly with producers, Yara’s field representatives learn what is successful and what is not, allowing the company to tweak a product to better meet growers’ requirements.

After more than 100 years globally, seven-and-a-half decades of experience in the North America fertilizer business and 25 years directly connected to the Canadian market, Yara has identified the unique needs of Canadian potato production across the country. The company works diligently to develop the products and offer advice on application to ensure its products help potato producers succeed.

LEFT: Yara is celebrating 75 years of meeting the fertilizer needs of the potato industry.

GOLDEN OPPORTUNITY FOR THE ADVENTUROUS

Growing spuds in the north is not for the faint of heart.

by Madeleine Baerg

In 2004, Steve and Bonnie Mackenzie-Grieve thought they were ready to slow down a little. Their two southern Alberta businesses – a potato storage insulation company and a fish farm wholesale business – were thriving, but not allowing time for the exploring, innovating and hands-in-the-dirt farming they dreamed of. So, they passed the businesses on to their son, Rob, packed their bags and headed north. Far north.

Seventeen years later, it’s clear that part of the MackenzieGrieves’ plan worked out: as Canada’s most northern commercial potato producer, the couple is adventuring and old-fashioned pioneering on a daily basis. The part of the plan about slowing down, however? That hasn’t worked out at all.

“We came up here as a sort of semi-retirement, but we’re busier now than we ever were in southern Alberta,” Steve MackenzieGrieve admits with a laugh. “But we’re different busy: now we’re busy on a farm instead of travelling all over the province. We’re

doing what we want to be doing.”

The Mackenzie-Grieves run Yukon Grain Farm, the Yukon Territories’ largest and most productive farm business. Located just a few minutes from Whitehorse, Yukon Grain Farm includes between 200 and 300 acres of grain that is processed into livestock feed on-farm, six acres of carrots, and two to three acres each of parsnips, cabbages, and several other vegetables. The farm is also home to 24 acres of potatoes: the most lucrative of all the acres and what Mackenzie-Grieve calls the base of their operation.

There are upsides to farming in the Yukon. The summer sun shines 19 hours a day. “You can almost see plants growing,” he says. “You go out there one day and they’re ankle height; the next day

TOP: Yukon Grain Farm’s success is thanks to its committed and enthusiastic staff team, say owners Steve and Bonnie Mackenzie-Grieve (both in red and black plaid).

More than 19 hours of daylight during the Yukon’s summer days allow some varieties of potatoes to achieve skin set despite a window of just 50 days from emergence to top-kill.

they’re knee height. It’s incredible.” And there are far fewer insect pests and crop disease issues, both because of how isolated fields are and the winter’s sustained cold.

That said, the Mackenzie-Grieves have to contend with a wide variety of challenges unique to farming in the Yukon.

“I think it’s fair to say that in almost all ways, it’s more difficult trying to grow food up here,” he says.

Every crop input has to be shipped north at great cost: think $8,000 per B-train truckload. Equipment is impossible to come by

With the Fresh Box you can - even at high ambient temperatures - refresh the air in your storage to the correct CO2 value, with minimal cooling or ventilation. The result: a constant storage temperature with a controlled CO2 level and therefore better frying color quality.

www.tolsmausa.com

locally: they had to ship in a custom-built one-row potato harvester from Belgium and a second-hand cup planter from Alberta. Equipment repair is even less accessible, unless you’re willing to pay for a repairman to fly up from British Columbia or Alberta.

Many crops – in fact, most crops – can’t successfully reach maturity in the Yukon’s ultra-short growing season.

“With beans, it’s highly unlikely they’ll ever mature. Peas are kind of a crapshoot. Some years they’ll do OK. This summer, they reached six feet, but they never matured because the spring was cold and the summer never really got warm. But you have to grow them. You need something else in rotation, because if you grow grain on grain on grain, you’ll end up with a field full of foxtail and wild oats,” Mackenzie-Grieve says.

The small size of the Yukon’s agriculture industry also brings challenges. The Yukon is home to only about 150 farms, of which only a small portion are producing at any kind of commercial level. As of 2017 – the most recent year for which statistics are available – the Yukon’s farms generated combined returns of about $4.3 million. The industry’s small size means there is no industry infrastructure.

“The toughest thing is we have to do it all ourselves: grow it, store it, process it, market it, and that’s for every crop we produce,” Mackenzie-Grieve says.

There’s also no industry infrastructure for exporting, which means all crops grown in the Yukon must be sold exclusively to the roughly 40,000 people who live in the Yukon.

“We are very limited by our market. Our market is so small that

Level up your foliar fungicide game with Miravis® Duo and protect the yield and quality of your crop.

To learn more about Miravis® Duo fungicide, visit Syngenta.ca/Miravis-Duo

Fresh Box

you have to do a bunch of things – you have to diversify into multiple crops – to make a farm work. The first step is figuring out what you can grow; the second step is figuring out what you can sell,” Mackenzie-Grieve says.

Perhaps most challengingly, the small size of the industry means front-runners like the Mackenzie-Grieve family need to figure everything out themselves. Successfully producing potatoes has been a very, very steep learning curve, he says.

He admits he started all wrong. They brought potato seed from the south, so carried in scab and various pests. “We should have started from scratch or gotten some really high-generation seed,” he says. “It’s taken us a long time to get on top of those issues.”

They tried a lot – a lot, he says emphatically – of varieties. Most were a disaster.

“Most varieties don’t work here due to size or skin set. You can’t harvest a potato that’s not ready. That’s where we’ve learned some hard lessons,” he says.

“Yield is very secondary to skin set. We can even do with a smaller variety: they just have to be able to get to a harvestable condition fast enough.”

Consider the math: the earliest they can get in to plant is the third week of May. They hope for emergence by the second or third week of June, but often don’t see potato plants popping up until nearly the end of that month. Top kill has to happen the first week of August – only about 50 days from emergence – so harvest can happen the first week of September.

“It all needs to work out exactly right or they’re not going to get skin set. When it works, they’re beautiful: the skins are so nice and clean and soft. They’re an easy potato to sell if you can get skin set,” he says. “But it doesn’t always work.”

They’ve had the most luck with Sylvana. Though they might not

be the best for consistency of shape, they have been the most successful variety for skin set, customers like their taste, and he likes their disease package.

Unfortunately, not everyone shares Mackenzie-Grieve’s enthusiasm: Sylvana was just discontinued as a production variety in 2020.

“We have some of our own seed saved, but not that much,” he says. “Now that they’ve quit reproducing them, we’ll have to find a new variety.”

That will be challenging, since getting seed to the Yukon is expensive and inconsistent, and few sellers want to waste time with the small quantities he needs for trialling.

Despite the challenges of farming in the Yukon, there’s nowhere he’d rather be.

He loves growing for an appreciative audience.

“It’s a very different game up here. When you’re farming in the south, it’s all about production and cost. You grow, you sell, it’s gone and that’s it. Here, we are very connected to the people who actually consume the food we grow. We get lots of feedback. The rest of the farming industry has kind of lost that. Our customers are really, really excited to be supporting local.”

He loves working with the farm’s half-dozen year-round staff, despite the fact that finding anyone with agricultural knowledge in the Yukon is very difficult.

“An ag background is good, but motivation is better,” he says. “The reason our farm works is because our farm staff love growing stuff and being part of this team.”

And, Mackenzie-Grieve truly, deeply loves the Yukon itself.

“Yes, it can be very challenging up here. It is worth it? Absolutely,” he says. “If I could do it all over again, I just wish I’d come up here 20 years earlier.”

Farming in the Yukon presents many challenges, but growers are connected to consumers in a unique way.

HERE’S SOMETHING FOR WIREWORMS TO CHEW ON.

The new potato insecticide that eliminates wireworms.

Always read and follow label directions.

This is bound to make wireworms take pause. Permanently. New Cimegra® insecticide eliminates wireworms, which in turn reduces resident populations in season. Using a new, unique mode of action with lasting residual activity, it delivers great results fast. In fact, wireworms don’t even have to ingest Cimegra – it works on contact. So why let these troublesome little pests take a huge bite of your potato profits? Go to agsolutions.ca/horticulture to learn more.

POTATO VARIETY TRIALS

New varieties are in the pipeline – with a fresh focus on industry requirements.

by Julienne Isaacs

Potato variety development takes a long time. In Canada, it typically takes six years before seedlings from crosses made at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s breeding program in Fredericton and Lethbridge make it to national variety trials, and two to four – or more – years after that before candidates complete agronomic trials around the country.

Here’s how it starts: AAFC’s potato breeder David De Koeyer plans a crossing block with approximately 100 parents each year and technicians make 200 to 300 crosses between two parents. Every year, 60,000 seedlings are grown in the greenhouses to produce tubers for planting at breeding stations in New Brunswick and Alberta. Selection begins at harvest and only the best progeny advance for further evaluation the next year, explains Erica Fava, the potato breeding program biologist at AAFC Fredericton who works closely with De Koeyer.

Once the breeding cycle reaches its fifth or sixth year, the remaining selections are sent to P.E.I., New Brunswick, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia to measure regional performance.

The University of Guelph’s potato research program, which collaborates closely with AAFC on field trials, receives material earlier

in the cycle – from the third year; this year, an industry collaborator in Manitoba also received third-year material.

Traditionally, the potato research station in Fredericton has released between 10 and 15 new selections per year, which were then offered to industry bids for private field performance and quality evaluation trials.

But Fava says AAFC has adopted a new model for potato variety development that takes industry feedback into consideration from the very beginning and streamlines the process.

“We really have come to realize that we don’t know it all and we need industry to tell us what is important to them and what they think will be important 10 to 15 years from now,” she says.

“In the past, we put out about 15 selections each year. We’re not doing that anymore. We’re breeding to more defined targets and putting out the highest quality selections. We get industry input as to what they’re liking and that feedback informs the next decisions,” she explains. “With each year, with all the improvements

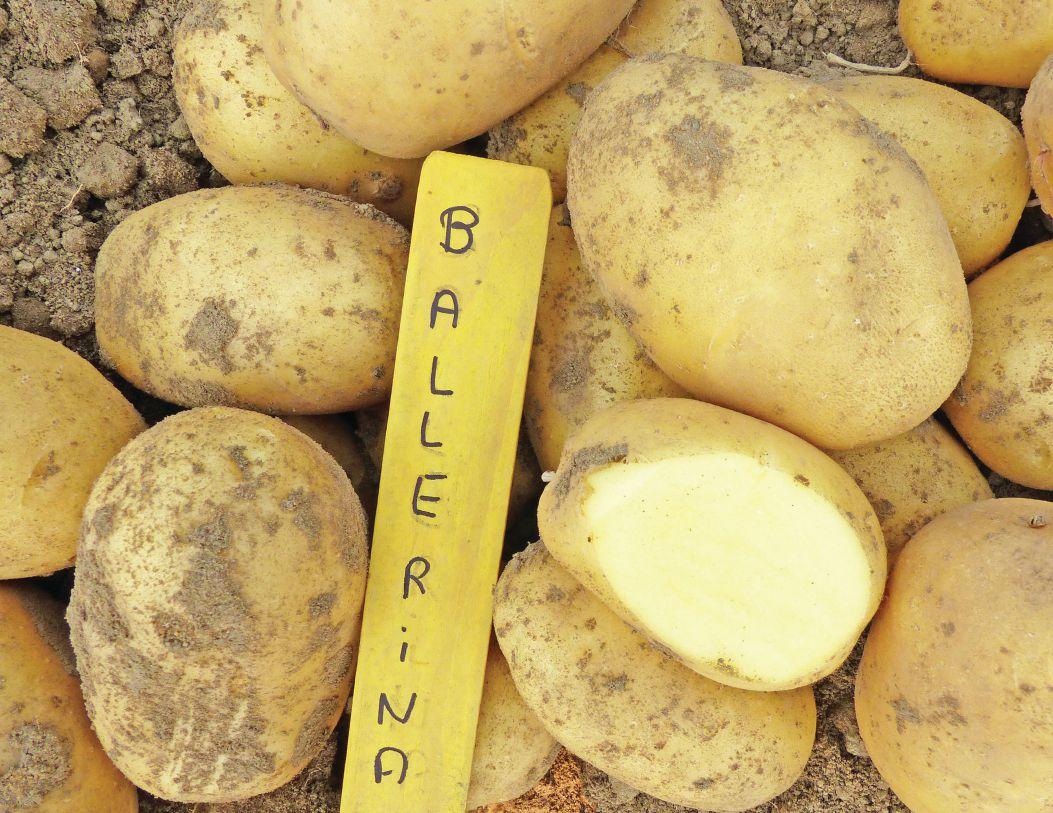

ABOVE: Ballerina has high yield, high tolerance to common scab and it did not show second growth in 2020, a hot summer in Ontario.

We’re looking for six women making a difference to Canada’s agriculture industry. Whether actively farming, providing agronomy or animal health services to farm operations, or leading research, marketing or sales teams, we want to honour women who are driving the future of Canadian agriculture.

and to submit your nomination.

MARCH26,2021 MARCH 26, 2021

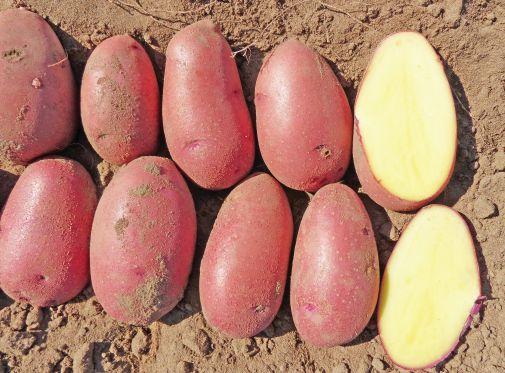

In its first year of evaluation in Ontario, Reveille Russet showed early maturity and fast emergence. It has tolerance to common scab and white flesh.

we’re making, better selections will become available.”

The material that’s currently in the pipeline, she says, will be used to try out and refine new breeding methods. But Fava says the biggest gains will be seen in a few years, when De Koeyer’s first crosses begin to be released and the program starts to use innovations such as genomic prediction methods.

The AAFC team hopes to collaborate more closely with private breeders for the fresh, chip and fry markets, but will focus roughly

70 per cent of its efforts on French fry selections, and the remaining 30 per cent on fresh and chip selections, Fava says.

“We were spread too thin trying to serve all the different markets,” she explains. Most of Canada’s private breeders work on development selections for the fresh market and chips, and AAFC can continue to contribute breeding material, techniques and information to those programs while focusing on fries.

“The reality is, the largest portion of Canadian acreage is dedicated

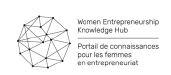

Merlot was developed in Germany and boasts an oval shape and red skin with medium to dark yellow flesh and shallow eyes.

The well-known Yukon Gold potato, bred by Gary Johnston through the University of Guelph’s potato research program in the 1960s.

to fries, and we need new varieties to be adopted that will allow growers and processors to make gains in environmental stewardship and food waste reduction,” Fava says.

AAFC’s collaborations aren’t confined to one part of the industry. Fava’s program works closely with research programs across the country, as well as end-user groups and growers, and tries to keep its finger on the pulse of where the industry is headed, so it can develop potatoes that will meet needs a decade – or three – into the future.

What makes the cut?

What qualities make the cut during the selection process?

Fava says basic agronomic qualities – such as yield and disease tolerance in a range of environments – have always been baseline requirements.

Drought tolerance is rising in importance, she adds. “We’re seeing more extreme weather events and the industry is saying they need varieties that perform well under drought.”

Growers are also looking for qualities that will make production more sustainable, so Fava’s program is incorporating new techniques developed by other AAFC science teams early in the breeding process to find parents that will have resistance to viruses like Potato Virus X and Potato Virus Y, as well as diseases like common scab and late blight.

In Ontario, University of Guelph researcher Vanessa Currie makes selections from the material Fava’s program sends based on how it performs in the region. Those that make the cut are flagged for Fava’s program so that they’ll continue trials in both provinces, even if they perform relatively poorly in the conditions of Atlantic Canada.

“One of the things you first look for is uniformity of size and shape,” Currie explains. “You want them to be free from obvious defects and blemishes like scab. They need to be attractive. You also want there to be an abundant yield. When we’re doing those early generation selections, those are some of the things we’re looking for.”

In subsequent trial years Currie and her team becomes even more critical: they look at yield, processing quality and storability. “We’ll also do culinary tests, measure specific gravity, make notes about internal and external defects, and look at maturity and disease

Think Different. Farm Better.

Protection zone

For corporate applications the logotype has a protection zone in which any other inscription or artwork is not allowed. The purpose of this zone is to give the brand easy recognition.

TIMAC AGRO fertilization program, we have increased production by 50% on Columba Yellows and 21% on Envol Whites

tolerance,” she says.

Currie says what the market demands in a potato is a “moving target,” but generally requirements are becoming more stringent over time.

“The potatoes people might see in the grocery store 25 years ago would not be acceptable today,” she says.

One example is creamers: 20 years ago, there was no market for small, round potatoes, but breeders now look for them during selections.

A significant emphasis in the selections process is finding potatoes that will supply the Canadian market during the early summer, when supply from the fall has been exhausted and the new crop hasn’t yet been harvested.

“There’s a period of about six weeks where potatoes are imported,” Currie says. “We’re trying to close that gap, and to do so there’s a two-pronged approach – finding potatoes that store as long as possible, and finding chipping potatoes that mature earlier and can be available by the middle of July.”

Eugenia Banks co-ordinates the Ontario Potato Board’s on-farm trials and has evaluated varieties for breeders across Canada and the U.S., as well as European breeders looking at Canadian distribution. She says that finding varieties that will grow well in different regions is key.

“Growers usually say they want to see how the varieties grow in their own backyard. I absolutely agree with them. I have seen varieties that perform very well in one area but have a poor performance in nearby areas,” she says.

The main factors that cause differences in performance, she says, include soil type and organic matter content, prevailing day/night temperatures, and rainfall or irrigation availability.

Banks says qualities that are prized in fresh market varieties include early maturity, an attractive appearance and flavour,

NEW AND PROMISING VARIETIES

Eugenia Banks, the on-farm trial co-ordinator for the Ontario Potato Board, has her eye on three new varieties that look promising for Ontario growing conditions.

Ballerina is a yellow-fleshed variety that has not previously been evaluated in Ontario. Ballerina performed well in Waterdown and Alliston-Beeton. Ballerina has high yield, high tolerance to common scab and it did not show second growth in 2020, a hot summer in Ontario. “It has even set, negligible culls, cooks well and is very tasty,” she says.

Reveille Russet is a russet developed in Texas. In its first year of evaluation in Ontario it showed early maturity and fast emergence. It has tolerance to common scab and white flesh. No hollow heart or second growth was detected. The variety is promising for the Ontario fresh market.

Merlot was developed in Germany and boasts an oval shape and red skin with medium to dark yellow flesh and shallow eyes. The variety, which is in its second year of evaluation in Ontario, should be grown in scab-free soil. It can be harvested early, before reaching maturity, for the baby potato gourmet market. Banks says it has excellent culinary traits and is very tasty.

AAC Burcadie is a long selection with tan skin, pink eyes and cream flesh. Erica Fava, potato breeding program biologist at AAFC Fredericton, says Sinonies Enterprise Inc. has the world license to this dual-purpose (French fry and fresh market) variety, and they are taking it to West Africa for commercialization.

Sinonies Enterprises Inc. also has the North American and world licenses for the fresh market variety AAC Africadie. It is a round selection with smooth red skin and cream flesh. It had high yields across all of the national potato variety trial sites, is resistant to PVY and has some resistance to Verticillium albo-atrum.

Fava says Parkland Potato Varieties Ltd. is in the process of naming an exciting new fresh market variety provisionally called AR2018-11. The company is excited to have this high-yielding, red creamer variety in their portfolio. It has a very uniform round shape with red skin and cream flesh. It matures early and has moderate resistance to common scab.

Parkland is also in the process of naming AR2018-15, another fresh market variety. This round, purple-skinned and -fleshed variety is the first purple variety in their collection. It is a high yielding, mid-season variety with a uniform size and shape. Preliminary studies have also shown moderate resistance to foliar late blight and common scab, Fava says.

shallow eye depth and dry matter comparable to Yukon Gold.

French fry processors look for potatoes that are long and blocky, high dry matter for a crisp texture after frying, low reducing sugars for light fries, and long dormancy.

“Growers usually say they want to see how the varieties grow in their own backyard. I absolutely agree with them. I have seen varieties that perform very well in one area but have a poor performance in nearby areas.”

Chip processors look for round tubers with high dry matter, low reducing sugars, long dormancy and no sticky stolons, so tubers can come off the vine easily when dug, Banks says.

She says new varieties can be gamechangers that shift the market. But she cautions that growers interested in trying new varieties should start small to ensure the variety is a good fit for their growing region and farm.

“Start small with any new variety –there are always surprises when scaling up,” she says.

The project is funded through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership (the Partnership), a five-year federal-provincialterritorial initiative.

If you can’t handle the stress, get out of farming.

talk to someone who can help

It’s time to start changing the way we talk about farmers and farming. To recognize that just like anyone else, sometimes we might need a little help dealing with issues like stress, anxiety, and depression. That’s why the Do More Agriculture Foundation is here, ready to provide access to mental health resources like counselling, training and education, tailored specifically to the needs of Canadian farmers and their families.

DIVERSIFIED PRODUCTION

Organic spuds still niche, valuable for those who decide to grow the delicate crop.

by Trevor Bacque

Organic food consumption and production continue to surge. Consumers are hungry for more organic offerings of their favourite foods. In 2020, Canadians spent $6.9 billion on organic foods, a 3.2 per cent capture of the total market sales in Canada, according to data from the Canadian Organic Trade Association. That number is also up from $5.4 billion in 2017.

Other consumer preference research has indicated that the younger the buyer, the more likely the demand for organic is, which may represent a market for organic potato growers in Canada. And while the idea is relatively new for many, there are farmers out there already taking advantage of the niche marketing opportunity.

Items to consider

Wayne Rempel, CEO of Kroeker Farms in Winkler, Man., has seen a dramatic rise in demand for organic potatoes since the farm branched out into diversified production. They began with 20 acres of organic potatoes in 2002, and that number has steadily risen to 1,000 acres today. But it hasn’t been easy.

“Several times we almost quit growing organics,” he says. “We couldn’t find the right varieties, quality was hard to achieve and we started thinking it’s going to be a lot more work and cost more to grow, so hopefully we get a premium.”

get into growing organic potatoes to do their homework and truly understand all angles of the specified

MIDDLE: While organic potato growing may not be for every farmer, some say there are market premiums to be found.

TOP: Wayne Kroeker, CEO of Kroeker Farms in Winkler, Man., cautions farmers who may want to

production.

While the value proposition for growing organic wasn’t what it was today, Rempel kept at it. He offers potential organic potato farmers a few items to consider based on his own experiences. Currently, Manitoba does not offer a reasonable organic crop insurance program, which he believes is the greatest impediment to increased organic production in the province. There is also a constant threat of blight which could wipe out his entire crop overnight. In addition to weed issues, Rempel’s spuds are a prime target for the Colorado Potato Beetle, a deadly pest with few available chemistries to control it due to tight restrictions from the Pest Management Regulatory Agency.

He explains, as well, that to get into organic production, your fields must be fallow and free from chemicals and fertilizers for three years, so farmers should be prepared for that.

“You have to produce something,” he says. “Sometimes we’ve decided not to produce and still have to manage weeds.”

Specific equipment for organic-only crops should be discussed, too. In addition, rotational crops will be grown on that field for three to four years after the potatoes themselves have been harvested, and the right equipment is needed to manage those crops. It is unique equipment not used or needed in conventional production of the same crop, Rempel says.

Nonetheless, the margins Kroeker Farms hits at times makes up for all the headaches and sleepless nights managing organic potatoes.

“On years when potato prices are relatively low, we make a significant premium because organic is fairly stable,” he says.

The yields at Kroeker Farms are typically pencilled in the year before at 65 per cent and the finance department plans from there. He says others go as high at 75 to 80 per cent.

Still, at a hypothetical 65 to 75 per cent, there is a positive margin to be made, and Rempel believes consumer demand is only going to increase.

“More and more, people are interested in organics in every aspect of their diets,” he says. “They want all the same products you can get in conventional. When we first got into it, people said it was a fad. Clearly it’s not a fad, so I wish people would see that it’s way more than that. I think it’s going to continue to have some growth every year.”

Field view

Kevin MacAulay has produced organic potatoes with his two sons Bradley and Jeffrey for the last nine years at their Prince Edward Island farm near Souris’ town limits. Their typical varieties are Alegria, Dakota Russet, Electra, Innovator, Kennebec and Norland Red.

MacAulay first decided to grow organic to try a more “environmentally friendly” brand of agriculture and explore the premium market space. The majority of their potatoes are exported to the eastern United States for the table-top market.

He says, where a 250 hundredweight (cwt) for potatoes is normal, a great result for organic would be 150 cwt. However, his weight typically hovers around 125 cwt.

At the farm, biologicals are being deployed in the fight against pests, weeds and fungi, including a copper product that has shown good results. In addition, MacAulay uses an organic pesticide with Spinosad as its active ingredient.

“We use the services of a crop scout and also use a weather station where we can get blight spores counts in the vicinity,” he says, adding that it is very hard to control the weeds. “You must watch things very closely, monitor the bins and move the potatoes

as quickly as possible.”

The short-season potatoes he grows work well with hot, dry summers, which naturally allows the potatoes to die on their own, saving on conventional spray applications. The farm equipment, including as his weeder and row spacer, is also specialized. He has been able to capitalize on provincial rebates, as well, which helps ease the financial burden.

The give-and-take on his farm is meticulously calculated, as inputs are costlier than a conventional potato farm.

“The input costs are higher, but we use less inputs because the land seems to be in better condition,” he explains.

He echoes the sentiments of Rempel and explains how, without more organic potato growers, companies do not see an economic return to develop new chemistries for farmers.

To be gentle on the organic spuds, MacAulay uses boxes rather than bulk bins. The pricier storage method makes it easier to spot rotten potatoes, which is helpful during sorting and moving product.

And since MacAulay is unable to use a sprout inhibitor on his potatoes, he has invested in venting and refrigeration systems.

“It is a must for organic growers,” he says. “This is costly, but many conventional farmers have them, also.”

He says demand continues, although it’s not as high as it has been at different times. Nonetheless, MacAulay believes that organic potatoes represent a premium market share he continues to provide for a tenth straight year.

“People want a nutritious, healthy product that is not going to have a negative impact on the environment.”

From left to right: Brad, Kevin and Jeff MacAulay. The three farm organic potatoes together near Souris, Prince Edward Island.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KEVIN MACAULAY.