Rotating c R ops

Intensive management can impact crop productivity and soil nutrients.

C NFIDENCE. O

TOP CROP

MANAGER

5 | Drones for better potato yields advancing the use of drone imagery as a more sophisticated tool for precision agriculture.

By Carolyn King

CROP MANAGEMENT rotating crops

By Trudy Kelly Forsythe

PESTS AND DISEASES

new control for Colorado potato beetle

By Julienne Isaacs

8 | The dark side of black cutworm growers in ontario and Western Canada are seeing more occurrences of this destructive pest.

By Rosalie I. Tennison Readers will find

Controlling weight gain with potatoes?

superior spuds

14 | Management practices for erosion new methods of handling tillage erosion and soil degradation.

By Julienne Isaacs

MANAGEMENT Scouts on it By Rosalie I.

Tennison

Taking control of biosecurity

By Stefanie Croley, editor

Un I vers I ty of Lethbr I dge we Lcomes new rese A rch ch AI r I n potAto sc I ence

The University of Lethbridge has appointed Dmytro Yevtushenko as research chair in potato science. Yevtushenko has studied the potato for more than 25 years and brings experience as a plant biologist to the role. www.AgAnnex.com

Photo

Stefanie Croley | eDitor

TAkING CONTROl Of bIOSECuRIT y

With 2015 behind us, a new growing season on the horizon brings a fresh start for Canada’s potato growers, especially those on prince edward Island who suffered a particularly concerning end to the year.

The prince edward Island government announced in early november that it would discontinue the provincial potato disinfection service, which was in place to prevent bacterial ring rot during the transport of potatoes. The discontinuation of the service –closing a station and removing mobile units by Dec. 31, 2015 – was a move that the p.e.I. potato Board found risky and upsetting.

But, by the beginning of January, the board had taken matters into its own hands, organizing a series of five workshops on cleaning and disinfecting trucks to help train the Island’s potato growers and exporters. provincial staff will be in place at the inspection station until March 31 to help with the transition.

The Canadian Food Inspection agency requires all trucks transporting seed potatoes to be cleaned and disinfected before being loaded, so the importance of these measures can’t be understated. The p e.I. potato Board says the Island’s industry has worked with many levels of government over the years to bring the disease to the point of functional eradication, and on-farm biosecurity measures are necessary to protect against potential sources of infection. To note, Manitoba had been free of bacterial ring rot for several years until this past spring when it was rediscovered in the province.

The discontinuation of the infection service is just one of the biosecurity issues that prince edward Island growers have recently faced. In fall 2014 and spring 2015, several cases of potato tampering were reported in p e.I. and nova Scotia, with consumers finding metal in potatoes purchased from the grocery store, prompting many warehouses to install metal detectors.

It’s surely not a stretch to say the Canadian potato industry is thankful for metal detectors and disinfection strategies, but let this be a good reminder that the security of your crop should always be top of mind. What do you do on your farm to protect your crop? Drawing a blank? perhaps it’s time to come up with a plan.

Do you have a disinfection routine at the beginning of the season to clean all equipment and storages? If you’ve ever visited a poultry farm or other biosecure area, you’re familiar with the disinfectant footbath that visitors are required to use before even stepping foot inside the barn. When you host a visitor, do you ask them to clean their shoes, or perhaps wear disposable shoe covers? Do you allow them to drive their truck – or even walk –on your field, tracking soil residue from somewhere else? Do you have biosecure zones clearly marked? are you confident in your inspection practices?

as we approach the new growing season, keep in mind that one seemingly small threat could be devastating to an entire crop. regardless of what provincial or private infrastructure exists., biosecurity is in your hands. now is not the time to be complacent.

TOP CROP

MANAGER

POTATOES IN CANADA SPrINg 2016

EDITOr Stefanie Croley • 888.599.2228 ext 277 scroley@annexweb.com

DIGITAL EDITOR — AgAnnex Lianne (Lia) Appleby • 226.971.2133 lappleby@annexweb.com

WESTErN NATIONAl ACCOuNT MANAgEr Michelle Allison • 204.596.8710 mallison@annexweb.com

ACCOuNT COOrDINATOr Alice Chen • 905.713.4369 achen@annexweb.com

MEDIA DESIgNEr Svetlana Avrutin

CIrCulATION MANAgEr Carol Nixon • 450.458.0461 cnixon@annexweb.com

VP PrODuCTION/grOuP PuBlISHEr Diane Kleer • 519-403-8816 dkleer@annexweb.com

DIrECTOr Of SOul/COO Sue fredericks

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710 rETurN uNDElIVErABlE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT. P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5 e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com

Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

CIrCulATION e-mail: subscribe@topcropmanager.com Tel.: 866.790.6070 ext. 202 Fax: 877.624.1940 Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SuBSCrIPTION rATES

Top Crop Manager West - 9 issuesFebruary, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.95 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada - 2 issuesSpring and Summer 1 Year - $16.50 Cdn. plus tax

All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industryrelated groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission © 2016 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication. www.topcropmanager.com

DRONES f OR b ETTER POTATO y IE l DS

Advancing the use of drone imagery as a more sophisticated tool for precision agriculture.

by Carolyn King

Drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles (UaVs), are becoming increasingly popular with crop growers as an easy way to take a look at their fields. now, researchers are fine-tuning the use of imagery from drones as a more advanced tool for precision management of Canadian potato fields.

This work with drone imagery is part of a major five-year project to boost potato yields. “about three years ago, potatoes new Brunswick and McCain Foods Canada came to me and said they were having issues in terms of potato productivity in eastern Canada,” says Bernie Zebarth, a research scientist with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) at the Fredericton research and Development Centre. “The data across north america show a slow but steady average increase over time in potato yields, going up about five hundredweight per acre per year. But in eastern Canada, that is not happening – the crop insurance data for new Brunswick suggest our yields are either stagnant or perhaps even decreasing slightly over time.

“That’s a serious concern for industry. For example, a lot of new Brunswick’s potato production is for French fries for export. To export, you have to be competitive. If you start losing yield, then you become less competitive. So they asked us to work with them to see what could be done about it.”

The project aims to increase yields by addressing the variability in productivity within potato fields. “The project has three main objectives. First, can we develop ways of mapping the variability in plant growth and yield in potato fields? Second, for the areas of the

fields that are not performing well, can we identify why? and third, can we overcome those yield limitations?” Zebarth says.

“In eastern Canada, precision agriculture is an exciting new area for us, and this is part of what we’re doing in the project,” he adds. So, they are trying out tools like drones and yield monitors to map in-field variability as a first step towards managing that variability through precision agriculture. according to Yves Leclerc, McCain’s director of agronomy for north america, managing in-field variability is key to improving yields and profitability for potato growers. “We need to understand profitability not only at the field level but also the subfield level, and manage fields at that level. It is no longer enough to manage a field based on the average conditions; we need to be more precise [to achieve a field’s full yield potential].”

The project’s initial phase, in 2013 and 2014, took place in new Brunswick only. For 2015 to 2017, the research is also taking place in prince edward Island and Manitoba. For the first two years, potatoes new Brunswick, McCain Foods Canada, aaFC and new Brunswick’s enabling agricultural research and Innovation program funded the project. With the expanded project, two additional agencies have come on board: the peI potato Board and the Manitoba Horticulture productivity enhancement Centre Inc. The project’s lead agency is potatoes new Brunswick.

Photos courtesy of Bernie

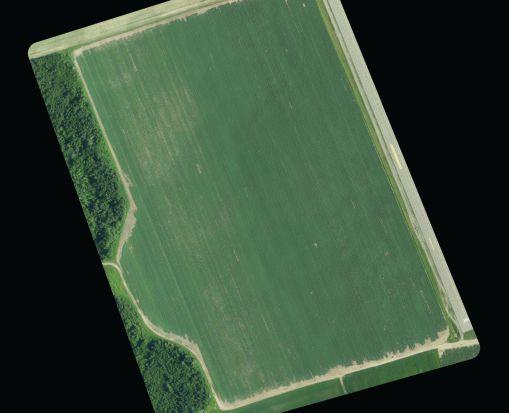

TOP: So far in the project, the drone has collected imagery from about 50 potato fields in New Brunswick.

To try to remedy yield limitations, the project team is looking at a wide variety of practices such as compost applications, fumigation, fall cover crops, nurse crops, furrow de-compaction and, in Manitoba, variable rate irrigation.

“We’re looking at everything from drones and drone imagery, to the thousands of holes we’re digging to look at soil compaction, to compost applications, to soil salinity – everything. We want to make sure that there’s literally no stone unturned,” says Matt Hemphill, executive director of potatoes new Brunswick. “There is no onesize-fits-all and no magic bullet in this process because we have such variability in soil and weather conditions.”

Drone imagery – advantages and hurdles

a drone with a specialized camera and advanced software can be used to map in-field variability. The drone flies over the field in parallel passes to capture the entire field in a series of overlapping images. The camera can be set up to capture particular wavelengths of light; for instance, near-infrared wavelengths may be of interest because healthy plants reflect more near-infrared light than stressed or dead plants. So a near-infrared image of a field could potentially be used to identify patches where the plants are stressed due to problems like disease or low nutrient levels.

“For instance, if we could use the imagery to identify the parts of a field that aren’t deficient in certain nutrients, then a potato producer wouldn’t need to waste time, energy and money in putting fertilizer products on those parts of the field,” Hemphill says. “Imagine, instead of broadcasting X number of tonnes per acre of lime across the whole field, you maybe only have to apply it to 25 per cent of the field. You can imagine how quickly those savings would add up. The same goes for other input costs.”

Zebarth explains that, before drones became available, the main way to map vegetation patterns was with satellite imagery, which has advantages and disadvantages compared to drone imagery. “one advantage of satellite imagery is that it’s calibrated [so the imagery data is easier to use in advanced analysis]. But there are two big problems with satellites. The first one is that you can’t control when they capture imagery of your field – they only fly over the field every so often, and they can’t see through the clouds. In new Brunswick, we have a lot of cloud cover. The other disadvantage of satellite imagery is its low resolution; a ‘pixel’, an individual point

of information, represents an area of maybe five by five to 30 by 30 metres in size [on the ground]. So we’ve never used satellite imagery very much to look at crops here in the east.”

Drones avoid those disadvantages. The user can choose where and when to capture the imagery, as long the operator flies the drone safely and legally. (anyone operating a drone in Canada must follow the rules set out in the Canadian Aviation Regulations and must respect all federal, provincial/territorial and municipal laws related to trespassing and privacy.) Cloud cover isn’t as much of an issue for drones because they fly below the clouds. and drone imagery is at a much higher resolution, about seven to 10 centimetres, depending on how high the drone is flown.

These advantages are making drones popular with crop growers. “people are already using drones, mostly for qualitative assessment. Drones are fantastic for that,” Zebarth notes. “one such application is to have a visual look at your field. For example, if you fly the drone when the crop is beginning to emerge, you can really see the field’s variability – where the crop is already emerging and doing well, where it is just emerging, and where it hasn’t emerged yet.”

another qualitative application is to target field scouting. Zebarth explains, “In the image of the field, you might see a patch that looks different. The imagery won’t tell you what the problem is; it will just tell you something is there. So you can go out to the field and look at that patch to identify the problem.”

However, the project team wants to take drone imagery a step further. “We’d like to get to where it’s a more sophisticated tool,” Zebarth says. “We want to determine quantitative differences, like trying to develop relationships between the imagery and things like yield and leaf area index, and so on.”

McCain Foods has its own drone, camera and software for this type of geo-referenced field mapping, and it has trained two of its employees to operate the drone, one as a pilot and the other as a spotter. For the project, they are flying the drone over commercial potato fields in new Brunswick. So far, they’ve collected imagery for about 50 fields.

They fly the drone over each field several times during the growing season. The first flight is when the soil is still bare, so they can look for differences in soil moisture and drainage across the field. The subsequent flights are timed to capture the crop during early and late emergence, mid-season, and early and late senescence. Zebarth says, “So we’re looking at: do we have variation

The researchers think a gradual decline in soil health, due to problems like erosion, is contributing to stagnant potato yields.

One of the commercial field sites participating in a multi-year project to boost potato yields

in the soil, the early canopy growth, and the canopy die-down.” one hurdle in their quantitative use of drone imagery is to correctly stitch together all the individual images from the drone’s flight over the field. “The drone might take perhaps 50 to 100 different images of the field. Those images have to be pieced together, which is called ‘mosaicking.’ If you have a discrete object, like a house or a fence in the images, mosaicking is not too difficult because you can easily find that object in the different images and align them. But if all you have in the image are rows of potato plants, there is not much to align with,” Zebarth notes. “There is mosaicking software to do that, but it’s not perfect. So we’re working with one of the drone companies to figure out how to get the images almost perfectly lined up so you can get down to looking almost at the [individual] plants.”

a second hurdle relates to calibration. “The drone’s camera is actually measuring how bright the light is in different bands; it is taking pictures that have red, green and blue, like a regular camera, but it may also have near-infrared. So it gives you a number from one to 255 in each of those bands, but it is just a relative number. To calculate things like vegetation indices, such as the nDVI [normalized difference vegetation index], you can use a relative brightness to get a relative value of the nDVI. However, you have to convert it to a reflectance value to get a true value for the nDVI that you can compare across fields or measurement dates. That’s where it has to be calibrated,” Zebarth explains.

The researchers are making good progress with overcoming both of these hurdles. plus, they are testing over 20 different vegetation indices to determine what each index is sensitive to and which ones work best for potato fields in new Brunswick.

“For instance, one index might be mostly sensitive to how much coverage there is of green leaves, whereas another one might be more sensitive to how much chlorophyll is in the leaves,” Zebarth says. They’ve already found that the nDVI, a common index for measuring vegetation cover, isn’t the best choice for potato crops. “For potatoes, the nDVI reading initially goes up as the canopy develops, but after the canopy reaches a certain density, the nDVI becomes insensitive.”

Some of the other indices don’t have that drawback.

once the researchers complete this work in the coming months, they’ll have a much better idea of how they can use the drone imagery. The information from this work could also help agronomists, crop advisors and growers with an interest in quantitative uses of drone imagery in potato production.

“In the long run, drone imagery is going to be a tool to add to our arsenal of tools, for sure,” Leclerc says.

Progress on agronomic findings

one of the project’s key agronomic findings so far is the degree of variability in potato fields. “We are seeing a lot more variability in our fields than we had expected. although some fields are relatively uniform, other fields have pretty dramatic variation,” Zebarth says.

The results so far indicate that, in new Brunswick, much of the variability is due to the soil. “What we think has been going on is a gradual decline in soil health over decades,” Zebarth says.

The wet spring in 2013 emphasized some of this soil variability. He says, “When we visited the field sites, we would see places in some fields where there wasn’t a single plant. It looked like problems with poor drainage or loss of soil structure or low soil organic matter. So that is why a lot of the remedies that we’re trying are ways to improve soil health, like compost applications or changing crop rotations.”

Leclerc notes, “The biggest challenge is determining the underlying causes of the differences in productivity. In some cases it’s fairly easy to pinpoint, especially [with the wet conditions] in the project’s first year, but in other cases it is a lot more difficult. We are examining that aspect with very precise soil and subsoil analysis.”

once a field’s variability is mapped and the causes of its differences in productivity are understood, then the field’s management zones can be defined and managed. “We can work on those management zones to improve the limitations, which are most likely soil-related. or, if that cannot be done, the idea is to manage the different zones differently. So perhaps we might back off in terms of inputs on the lower productivity zones and reallocate those resources to the higher productivity zones, and look at changing the spacing perhaps on the higher productivity zones to take advantage of their higher yielding capabilities,” Leclerc says.

after the trials with the various management practices are completed, the project team will analyze the results to see which practices provide the most consistent benefits, how effective they are, and under what conditions they are most effective, and to determine which options make the most economic sense.

“at the end of the day, we need to look at the input costs and profitability,” Hemphill says. “The outcome needs to work for the growers and the processors in order for the industry to remain sustainable.”

As part of the project, the researchers are collecting soil samples to examine soil microbial community diversity.

A drone with a specialized camera is used to collect imagery in different bands of light.

Pests and DISEASES

Th E DAR k SIDE Of bl

AC k C u T wOR m

Growers in Ontario and Western Canada are seeing more occurrences of this destructive pest.

by rosalie I. Tennison

Just because black cutworms don’t overwinter in Canada doesn’t mean they aren’t a threat to potato crops. The insects spend their winters in the southern United States but travel north on low-level jet streams and, once they cross the border into Canada, they look for a tasty food source. Black cutworm moths prefer some of the weeds that grow in and around fields and, while potatoes are not their favourite food, they will adapt and can wreak havoc on an unmonitored field.

a researcher at the University of Minnesota says the cutworms’ new interest in potatoes could be the result of a change in potential host plants. If the moth’s desired weed is being well controlled in a field, it will eat what is available where the wind sets it down.

“Black cutworm moths are active flyers,” explains Ian Macrae, the extension entomologist at the university’s Crookston research station. “These insects can travel hundreds of miles in a short period of time aided by an extremely efficient bug highway [a jet stream].”

Macrae says if the wind and temperature are conducive and Canadian potato producers are able to get their crop planted in good conditions, there is a chance the moths will arrive about the same time as the plants are emerging. The possibility exists that early arrival could spawn a second generation of the insects later in the season. He says, once landed, reproduction occurs when the moths lay eggs. The emerging larvae will feed on the foliage, but once at the fourth or fifth larval stage they will begin actively eating near the base of the host plant, cutting it off.

“The first you might notice a cutworm problem will be plants that are cut at the base or wilting,” Macrae explains. “at night, the worms burrow into the soil and if the tubers are close to the surface, they will burrow into the tuber. They can do more damage to tubers in dry conditions because cracks in the soil will give the cutworms access to what is underneath.”

Damage to potato crops early in the season can be a greater problem because the young plants will not recover from being chewed off. There is a possibility that the seed piece might send up another shoot, but the crop will be set back. Macrae suggests early scouting will help identify the problem and allow time for control. There are effective insecticides for control of black cutworm and there are sources of natural mortality, such as predators or parasitic wasps. Birds may be less effective because of the location of the worms and their habit of eating at night.

“If you find yourself at a threshold of about 30 per cent of your plants cut, you may want to apply an insecticide,” Macrae says. “If defoliation is this high, it may be that natural mortality sources are not functioning well.”

ensure proper identification of the larvae as black cutworms so the correct product can be chosen for control. Combining regular field scouting with pheromone or light traps to catch the male moths

ABOVE: Black cutworm moths have a new interest in potatoes and can cause major problems to an unmonitored field.

Photo courtesy of e ugenia Banks.

is an effective way to identify the insects.

“When scouting, look for stalks at an odd angle or wilting,” Macrae suggests. “Look in the evening when the cutworms come out to feed, and look as much as a half metre away from the plant because they are good walkers. Black cutworms are aptly named because they are a dark caterpillar with a waxy appearance. They will often curl into a C if disturbed. They hang out during the day under clods of soil or in cracks.”

Macrae says climate change may be the reason black cutworms are being seen farther north. He doesn’t believe they will begin to overwinter in ontario or the prairies, but a warmer climate means they develop faster and may overwinter in more northern states, making the migration north earlier and causing greater problems.

“Black cutworms have certainly become a problem in ontario in the last few years,” Macrae says. “They can be a significant pest issue.”

Macrae adds there are some cultural practices that may minimize the impact of black cutworms when they arrive. planting late can put new, young plants directly on a collision course with the moths and their offspring, so plant early, if possible. He says controlling weeds will reduce the areas where the moths might lay eggs. growers in the United States use pre-plant tillage to turn over the soil to destroy potential habitat.

Potatoes in Canada Due to the pub: 1-15-16 4.625" x 10" Today’s date: January 8, 2016 2:30 PM Account Service: CG035686P412FVB Account Coordinator: Art Director: Production: Proofing:

Feed me Feed me Feed me

To date, there is no accurate monitoring system in place for potato crops, according to Macrae, but the cutworms also like corn and the corn growers in some states, such as Iowa, have a black cutworm monitoring network. “The moths seem to appear in ontario about three weeks after they are seen in the United States,” he says. ontario growers could tap into the monitoring networks south of the border and use that information as an early warning system, he suggests.

Black cutworms could be considered a stealthy yield robber because by the time you begin to notice a problem, it could be a challenge to execute effective control. The best defence is early and frequent field scouting and adopting cultural practices that could minimize the attractiveness of the crop. Macrae believes Canadian potato growers will see black cutworm more often in the coming years, so preparation for and understanding of the pest is a wise approach.

There’s a better way to feed your potato crop.

Crystal Green provides continuous, seasonlong, Root-Activated™ phosphorus, with nitrogen and magnesium to help crops thrive with a single application. Unlike conventional, water-soluble fertilizer, Crystal Green releases nutrients in response to organic acids exuded by growing roots. In other words, plants get what they need when they need it with minimal nutrient tie-up and loss due to leaching and runoff.

For more information, visit crystalgreen.com/potato

+ 10%Mg

ROTATING CROPS

Long-term, intensively managed irrigated potato rotations have potential to impact crop productivity and soil nutrient status.

by Trudy Kelly Forsythe

Careful management of irrigated potato crops over the longterm may help maintain crop productivity and nutrient availability within acceptable levels for agricultural production. This is the conclusion agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC) researchers reached when they did a field experiment the year after completing a long-term irrigated potato rotation study in Brandon, Man.

During that initial 14-year rotation study, ramona Mohr, a sustainable systems agronomist at aaFC, worked with a team of researchers to identify economically and environmentally sustainable rotations for irrigated potato.

From 1998 to 2011, Mohr and her colleagues grew six different rotations: potato-canola, potato-wheat, potatocanola-wheat, potato-oat-wheat, potatowheat-canola-wheat and potato-canola (underseeded to alfalfa)-alfalfa-alfalfa, and looked at their effects on various factors including crop yield and quality, diseases and weeds, soil quality and economics.

“generally accepted management practices were used during the 14-year

rotation study,” Mohr says. “We soil tested on an annual basis and adjusted our fertilizer management practices accordingly.”

In the year after the rotation study ended, the researchers conducted a followup study to assess the impact preceding rotations had on phosphorus, potassium and micronutrient concentrations in the soil, as well as on soybean yield, quality and nutrient concentration.

For the follow-up study, the group picked a glyphosate-tolerant variety of soybean as an indicator crop to try to minimize possible confounding effects of the previous rotations with respect to disease, weeds and nitrogen.

It was a unique opportunity to study the relative effects preceding rotations have on crop productivity and nutrient status of the plant-soil system, given the limited information available for Western Canada.

“This rotation study was one of only two longer-term irrigated potato rotation studies conducted in Western Canada over the past couple of decades,” Mohr says.

An aerial view of the potato rotation study located at Carberry, Man., in 2010.

TOP: Irrigating potato plots in the potato rotation study.

Photo

Taking multiple soil samples from each rotation in the spring of 2012, the researchers were able to compare them with samples taken in 1997 at the beginning of the long-term study. They discovered that the soil nutrient levels and the yield and quality of the soybean crop were all typical of the region.

“We saw some differences in nutrient levels among the different rotations, but no substantial depletion or build up of nutrients, and no large differences in soybean yield among the rotations,” Mohr says.

Yield

preceding rotations affected soybean yield to a limited degree. Soybean yield was six per cent higher following the potato-oatwheat rotation than the potato-canolawheat rotation, although the reason for this difference wasn’t clear.

“We also noticed when soybean followed potato, it had a slightly higher yield than following cereals or canola, we suspect, because of greater availability of water because the potato crop was irrigated and none of the other crops were,” Mohr says.

The samples also showed that where preceding rotations included alfalfa, seed protein increased and oil concentration decreased. The researchers believe the limited yield differences may have been due, in part, to the selection of soybean as an indicator crop. This likely minimized the differences among rotations arising

“If producers were to grow other crop species, there might be a greater impact on crop productivity.”

from disease, weeds and nitrogen. Soybean had not been used in the rotation study and so was not susceptible to those diseases that had built up in the preceding rotations. also, it is a nitrogen-fixing crop that could supply its own nitrogen. as well, by selecting a glyphosate-tolerant soybean, weeds could be effectively controlled regardless of the previous rotation.

Nutrients

For nutrients, the researchers looked at phosphorus and potassium in the top 15 centimetres of the surface soil and found they fell within the same general range of what they saw in 1997.

Soil test phosphorus was slightly higher except for the rotation that included alfalfa hay. That rotation saw a reduction of both phosphorus and potassium, which the researchers determined was likely a result of the high nutrient removal rates of alfalfa hay and their fertilizer management practices during the long-term study.

For example, Mohr says they applied phosphorus in the alfalfa establishment

year, but not potassium because soil levels did not call for it. “When we saw a decline in soil potassium levels, we started applying potassium at that point.”

Soil test phosphorus levels were also found to be higher in the shorter rotations. “The two-year was greater than the three-year was greater than the four-year rotation,” Mohr says. again, the researchers attribute this to their fertilizer management practices since they applied a higher rate because they broadcast the fertilizer in potato, adding more phosphorus than the potato crop removed.

“The more frequently we grew potatoes, the higher the soil test level we tended to see,” Mohr says. “although we saw some difference in soil test levels, again they were within the range we see in agriculture fields.”

Micronutrients

Mohr and her colleagues also looked at micronutrients during their follow-up study. “The site had sufficient micronutrients for the crop so we didn’t need to add any fertilizer,” Mohr says, although certain of the fungicides applied to potato would have contained some copper or zinc. While the preceding rotation had minimal effects on soil copper and zinc levels, soybean established after the potato-canola-alfalfa rotations or directly following a potato crop contained comparatively higher seed copper and zinc concentrations.

This suggests, Mohr says, that including mycorrhizal crops, like potato and alfalfa, might have increased the availability of micronutrients to the following soybean crop. “The roots of potatoes and alfalfa form a relationship with mycorrhizal fungi in the soil, which may increase the availability of micronutrients. We didn’t measure mycorrhiza in this study, but we know that based on previous studies.”

Conclusion

The results of the follow-up study in 2012 do suggest that careful, long-term management of irrigated potato systems may help maintain crop productivity and nutrient availability within acceptable levels for agricultural production. However, Mohr stresses the impacts of disease, weeds and nitrogen fertility on crop growth may have been minimized because the researchers selected soybean as the indicator crop in this study.

“If producers were to grow other crop species, there might be a greater impact on crop productivity,” she says.

Rotational crops in the potato rotation study at Carberry, Man., in 2008.

Photo courtesy of a gricu L ture and a grif ood c anada.

N Ew CONTROl f OR C OlORADO POTATO b EET l E

RNAi can work two different ways, but both methods have shown 100 per cent effectiveness in field trials.

by Julienne Isaacs

New hope is on the horizon for potato growers engaged in the ongoing battle against Colorado potato beetle (CpB). researchers are currently field-testing one of the most effective controls ever developed for the potato’s chief insect villain, and it is entirely chemical-free.

rna interference (rnai) is a biological process whereby rna (ribonucleic acid) molecules activate a protective response against parasite nucleotide sequences by inhibiting their gene expression. In other words, it is the method by which organisms – including pests such as CpB – defend themselves against threats and regulate their own genes. But the same process that is used by a beetle to protect itself can be used to destroy it when it consumes the long double-stranded rna (dsrna) in genetically modified plants.

Since 2009, researchers at the Max planck Institute in potsdam and Jena, germany, have been developing genetically modified potato plants to enable their chloroplasts to accumulate dsrna targeted against essential CpB genes. after feeding on a potato’s leaves – and ingesting the dsrna – the beetles in the study showed 100 per cent mortality within five days.

Why chloroplasts, rather than plant cell nuclei? In past breeding projects, expression of dsrna in potato plants’ nuclei has proven inefficient because natural rnai pathways in nuclei prevented the plant from producing enough long dsrna. But long dsrna are free to accumulate in chloroplasts – which have no rnai mechanism –and the plants are fully protected against CpB.

according to Jiang Zhang, a professor with the College of Life Science at Hubei University in China, and the lead on the project, the technology shows great promise for the future of pest management, but there are no immediate plans for commercialization until all regulatory hurdles have been overcome.

“We encourage more scientists and industry involvement in this field for a better future,” Zhang says. “There is still a long way to go to make it really useful in daily life and be accepted by customers.”

RNAi-based biocontrol

rnai for control of CpB has also gained significant momentum in private research and development. Monsanto and Syngenta have both devoted major investments toward the technology.

In early 2015, Monsanto’s BioDirect technology platform targeted at CpB advanced to phase 2 – early product development –of the company’s research and development pipeline. The product will have to complete advanced product development and prelaunch before broad commercialization early in the next decade.

While the principle is the same, Monsanto’s product works differently than Max planck’s modified potato plant: it is sprayed

onto the plant’s foliage. rather than expressing dsrna in its leaves, dsrna is applied exogenously to the plant.

“The Colorado potato beetle consumes the leaves of the potato plant where we can focus the BioDirect application, versus needing a plant to produce the dsrna targeting the pest below-ground where sprays cannot reach,” explains greg Heck, weed control team lead for Monsanto’s chemistry technology area.

Heck says there are thousands of dsrna naturally present in host plants that serve a variety of functions, and beetles consume and incorporate dsrna all the time. “When targeting them for pest control, we seek to supply one additional dsrna that will turn down a specific gene critical to their ability to feed and grow on the plant.

“Field research conducted on our BioDirect treatment for Colorado potato beetles has already demonstrated some early positive results. This includes reduced Colorado potato beetle larva infestation and plant defoliation in multiple geographies.”

Syngenta’s most advanced rna-based biocontrol targets CpB in potato – and is also applied via a spray. The company has tested the product in multiple geographies over several years with positive results, says Luc Maertens, Syngenta’s rnai platform lead based in Belgium. The company hopes to commercialize the product early in the next decade pending continued development and regulatory reviews.

Maertens says the company’s biocontrol is highly selective and starts to work before CpB can cause too much damage.

“The biocontrol is not systemic [in the plant], nor does it work through contact,” he says. “It does not change or have any effect on the Dna of the pest, nor does it involve genetic modification of the plant.”

no technology can work forever, however. Insect resistance to rnai is a potential risk – one companies and researchers alike are keen to avoid so the technology has maximum benefit and longevity.

Maertens says that as resistance emerges to existing technologies, and the pest spectrum shifts along with climate change and other factors, growers’ needs will change. “Those challenges cannot be answered by only one technology,” he says. “It is imperative to gain insights into probable resistance mechanisms to rnai triggers in insects, to monitor possible resistance in the field, and to support the use of the technology with appropriate stewardship requirements.”

of the two methods of rnai application (genetic modification and spray-on), Zhang believes the former might be better for growers. “applying dsrna exogenously is much less cost-effective than expressing dsrna in the plant itself,” he says. “Spraying may also cause other potential problems in the environment.”

rnai is not meant to be a silver bullet and should be used as part of a multifaceted pest control strategy. regardless of the method of application, rnai may soon be working in a field near you.

mANAGE m ENT PRACTICES

f OR EROSION

New methods of handling tillage erosion and soil degradation.

by Julienne Isaacs

Anew Brunswick researcher says that despite the common perception that water and wind are responsible for erosion, tillage erosion is actually the leading cause of soil degradation in most cultivated fields in Canada.

Li Sheng, a hydrology/croplands and water management expert with agriculture and agri-Food Canada, has been analyzing the causes of erosion in order to develop management recommendations. His message is surprisingly positive.

“our perception is that soil erosion is really bad in eastern and atlantic Canada, but it’s actually getting much better,” he says. “people are more aware of erosion, and a lot of structures have been put in place to reduce it. However, in critical times, you’ll still see a lot of erosion happening and erosion remains the number one cause of soil degradation in many fields.”

For the past few years, Sheng has led a research team conducting several studies in erosion. one study comparing water, wind and tillage erosion, conducted in partnership with David Lobb, a University of Manitoba soil researcher, found that wind erosion is much less severe than water erosion in eastern Canada. While it is more damaging in Western Canada, wind erosion in most fields is still not at the same level as water or tillage erosion.

The most worrying aspect of erosion on the east Coast, says Sheng, is the combined effect of water and tillage erosion.

These days, Sheng’s team is testing the hypothesis that water and tillage erosion work together to create a more severe problem – that tillage erosion actually offers a mechanism for soil to leave the field by water erosion.

“If you have gullies going down the field, cutting through the soil to the edge of the field, if you till the field and fill those gullies in, in the next major rainfall event, all of this loose soil will be washed away,” he explains. “We are thinking that in eastern Canada this is probably one of the major mechanisms of the transportation of sediments going out of the field.”

In the summer of 2015, Sheng and his team set up multiple research sites on prince edward Island and in new Brunswick. a gauging station on the edge of the field will measure sediment and take water samples. The research team also put cameras and erosion pins at different points in the fields to analyze surface changes due to erosion.

The study will run three years to allow the researchers time to collect solid data during potato rotation schedules.

Maintaining erosion structures

Sheng’s team has developed a list of best management practices to help growers minimize erosion. Conservation tillage and mulching are both key strategies, along with erosion management structures such as terracing and grassed waterways.

The latter might not be commonly used in Western Canada, but Sheng says it’s difficult to find potato fields on the east Coast that do not employ them.

The problem is a lack of maintenance.

Snowmelt erosion created a wide gully in this field.

Poorly-maintained grassed waterways turned into a source of erosion rather than a conservation feature.

Photos courtesy of Li s heng.

“a lot of these structures are not very well maintained – there’s certain maintenance that has to be done to keep them functioning,” Sheng says.

Diversion terraces (sometimes called contour terraces) are one good example. on hilly land, diversion terraces break up long, sloping fields into smaller sections with shorter slopes, to slow down and divert runoff. “The longer the slope, the higher the water erosion, and the greater potential for eroded soil to be carried away by that high-power runoff,” he says. Terracing can vastly mitigate this problem. But growers should ensure they use terraces to their maximum potential – and don’t cut corners.

“above the terrace berm, where the water comes down, there is supposed to be a one- to three-metre-wide channel, or runoff ditches, to allow runoff to flow at a non-erosive speed and sediments to deposit. However, many farmers will farm right to the edge of the berm, because allowing it means a loss of acreage and total production,” Sheng says.

Sometimes farmers are slow to clear out runoff ditches, but once filled, they lose their function. runoff during heavy rainfall events can cut across the terraces.

another example is the use of grassed waterways as informal roadways for field access, Sheng says. grassed waterways are used as roadways “by maybe 90 per cent of farmers,” resulting in severe

soil compaction, which can lead to reduced water infiltration and reduced function of grassed waterways on erosion control.

But the number one cause of soil erosion in many fields – tillage erosion – is the problem growers should focus on addressing.

“People are more aware of erosion, and a lot of structures have been put in place to reduce it.”

“Some farmers do recreational tillage – when they have some free time, they like to go out in the field and do additional tillage that is not needed,” Sheng says. But growers should reduce disturbance to the soil as much as possible, which means eliminating unnecessary tillage, and any other unnecessary disturbances during seeding or harvesting.

“reduce the frequency of tillage, the intensity of tillage, and the variability of tillage – the speed and depth,” he says. “Keep it as uniform as you can. Controlling speed and depth across the landscape will reduce tillage erosion.”

Most of all, growers should take a “landscape perspective” to erosion control, Sheng says, considering the entire system rather than individual fields and strategically employing best practices.

Tillage furrows along the slope facilitate water flow and enhance water erosion on this field.

Sediment traps were used to collect sediment samples in a study to quantify the sources of sediment.

Whitish subsoil is exposed on the lower sides of the terraces in this field, indicating terraces used to reduce water erosion may increase tillage erosion.

Field plot study being carried out to quantify tillage erosion.

C ONTROll ING w EIG h T

GAIN w IT h POTATOES ?

A potato extract could help fight obesity and other major health concerns.

by Carolyn King

Apotato extract that’s rich in beneficial compounds is looking very promising. In trials with mice, researchers at Mcgill University have found that this extract reduces weight gain and provides other important health benefits. now, they hope to conduct clinical trials to see if the extract produces similar benefits in people.

In this research, Danielle Donnelly, a potato researcher in Mcgill’s department of plant science, has teamed up with Stan Kubow and Luis agellon, who are both at Mcgill’s school of dietetics and human nutrition. The research had its beginnings in Donnelly’s research on genetic improvement of russet Burbank, the number one processing cultivar in Canada.

Because russet Burbank has limited fertility, traditional breeding techniques aren’t effective for developing improved lines. So, about 10 years ago, Donnelly and her research group developed a technique using tuber tissue to propagate plantlets that can differ genetically from the original tuber. These variants, called somaclones, can then be grown in the field and screened for various traits. Donnelly has produced about 800 russet Burbank somaclones.

“I had been screening my somaclones of russet Burbank for yield and processing characteristics after long-term storage, and doing the

selections and realizing that the somaclone technology could be very helpful there,” Donnelly explains. “Then, in talking to Stan Kubow, I realized that we should also be looking at nutritional parameters because the processing industry, and the whole potato industry, needs to be more concerned about the health of their consumers.”

Donnelly and Kubow started collaborating on potato nutrient research. In one part of this research, they examined the mineral content of 16 cultivars, including chippers, fryers and table stock, grown at five locations. “We found there was a lot of variation between the cultivars. potatoes are not created equal for minerals! russet Burbank and Yukon gold were particularly good,” Donnelly says.

They determined that one serving per day of russet Burbank, Yukon gold or Freedom potatoes provides a significant portion of the recommended daily intake for magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, copper, iron, selenium and zinc.

In another part of their nutritional studies, Donnelly and Kubow determined the antioxidant levels in her top 25 somaclones that were best for yield and processing traits. In potatoes, antioxidant

Photo courtesy

TOP: Luis Agellon, Danielle Donnelly and Stan Kubow discuss their potato extract that could help in controlling obesity.

activity comes from vitamin C, a number of polyphenolics and other compounds. out of the 25 somaclones, they selected the four that had the highest antioxidant activity plus a range of polyphenolic compounds.

From this screening and selection work, Donnelly currently has four advanced lines moving toward registration. She hopes to register the best one or two of those lines later this year. “all four lines have high yield, three of them do better than the russet Burbank control in fry tests, and all have very high protein and high antioxidant capacity,” she notes.

Fat-fighting extract

In a different aspect of the potato nutrient research, agellon, Kubow and Donnelly investigated the effects of potato polyphenols on diet-induced obesity. The possibility that eating polyphenols might control obesity may seem surprising, but obesity actually has a connection with inflammation. research has shown that obesity results in low-grade chronic inflammation due to the reaction of certain cells to excess nutrients and energy.

as a first step, Kubow and Donnelly grew 12 different potato cultivars for several growing seasons and compared their polyphenolic contents. They found that onaway and russet Burbank had higher and more consistent polyphenol levels than the other cultivars.

next, using these two cultivars, the researchers made an extract containing a mixture of potato polyphenols. “The extract concentrates the active ingredients, making it more likely to see the biological effects we were interested in,” Kubow explains. one dose of the extract has about 30 times the amount of polyphenols found in a single potato. The main polyphenol in the extract is chlorogenic acid, which has been shown to have anti-obesity effects in some situations.

Then the researchers conducted a feeding trial with mice to evaluate the effect of the extract. “The mice were fed a diet that is similar to what many north americans consume; it is high in calories, high in fat, and high in sugar content. We wanted to see if these polyphenols, when given to mice that are ingesting this high-fat diet, would help in preventing obesity,” agellon says.

one group of mice was fed just the high-fat diet. a second group was fed the high-fat diet plus the potato extract. and a third group was fed the high-fat diet plus an equivalent amount of a purified single polyphenol, either chlorogenic acid or ferulic acid.

“We were intrigued by a number of studies that tested single polyphenols reported to be active in some systems but that were not as effective when used in a purified form; it seems that the purified compound had lost its potency,” agellon explains. “We wondered if the desirable effect associated with a food like potato and the polyphenols that it contains, is because of a combination of the different compounds in the food.”

Their hypothesis was that each individual polyphenolic compound produces a small benefit for a particular area of the body, like the liver, but multiple polyphenols ingested together affect multiple pathways, producing a synergistic effect with major health benefits.

agellon says the extract’s benefits emerged quite quickly in the trial. “Midway through the 10-week study, we could see which of the groups had received the polyphenol extract. They had less weight gain and were much more active than the mice receiving the high-fat diet by itself.”

Kubow adds, “This effect wasn’t because the mice didn’t like the diet and didn’t eat it. They were eating as much or more of the highfat diet [as the other groups of mice]. normally, mice respond just like humans – if they eat a lot of fat, they gain a lot of body fat and body weight. But to our surprise, the extract had quite remarkable

potency in inhibiting that, regardless of how much they ate.”

The individual polyphenols were not quite as effective as the extract in reducing weight gain, suggesting synergistic benefits from the mix of polyphenols in the extract.

The researchers are excited by the extract’s potential human health benefits. agellon notes, “The extract could be a wonderful tool to help people suffering from obesity.” To move forward on this, they need to conduct clinical trials to assess the extract’s fat-fighting effect in people. “We’ve got a lot of data supporting this effect in animal trials and in some culture trials, but clinical trials are the key, critical step toward commercialization,” Kubow says.

Pollution protection

The researchers have also looked at the extract’s effect on another inflammation-related health problem: lung damage caused by air pollution. Kubow explains, “Inflammation is your immune system overreacting to various compounds, including pollutants. With air pollution, that overreaction causes damage in various tissues including the lungs. So our hypothesis was that the extract might be effective where people are overweight and exposed to pollutants at the same time.”

In this study, they fed two groups of mice a western-style diet, similar to the diet in the obesity trial but not quite as high-fat. For four weeks, one group was fed the high-fat diet, and the other group was fed the high-fat diet plus the extract. Then the mice were exposed to ozone for four hours, to replicate the effects of exposure to heavy smog. “We looked at their lungs 24 hours after that exposure because the body is continually overreacting with the inflammatory response. That allowed us to detect factors in the lungs associated with ozone damage and inflammation,” Kubow explains.

The results showed that the mice eating the potato extract had significantly less lung damage. “We think this study was an important first step to validate the use of this extract as a means of potentially having a supplement to combat air pollution, which would be the first such supplement,” Kubow says. “However, we need clinical trials for verification of the benefit in humans.”

Clinical trials are key

The researchers are currently seeking funding for clinical trials to see how well the extract fights obesity and lung damage in people. If those trials prove the extract’s effectiveness, then the extract could have commercial potential, for instance, as a dietary supplement or a cooking ingredient. So investment in the trials could be of interest not only to health agencies but also to the potato industry because of the extract’s value-added potential.

Donnelly sees a couple of ways the next steps in this research could help potato growers and processors. “First, there are the clinical trials, which would get a product out there. Secondly [with information on polyphenol levels in more cultivars] it could be that more potato growers could benefit because there is a lot of wasted potatoes – people growing small potatoes have big ones they can’t use, and big potato growers have little ones they don’t always know what to do with. It may be that some of these materials could be rescued from waste streams from processed potatoes. So there is a lot of potato that could be used for a product that no one has produced up until now, which is this extract.”

as well, a potato extract with proven health benefits might help enhance the health reputation of potatoes. Kubow says, “The public perception is that potato intake is bad for your weight, but we’re talking about potato decreasing the risk of overweight and obesity.”

Keep it in the family

Let’s tell the

story of family farms

Feeding the world is not just a big responsibility, it’s big business – with a world population over 7.3 billion, it has to be. However, many consumers don’t associate large-scale business with family business, even though 98% of

Canadian farms are family-owned and operated. As a result, many consumers don’t trust their food supply. We need to make sure the story of the family farm is being told, and that “big” doesn’t mean “bad.”

We all have stories we can share, whether you grew up on a family farm, or you work in an industry that serves farm families. Look for opportunities to tell the real story of Canadian agriculture, whether it be online, in the grocery store or at the dinner table.

Here are some talking points to get you started:

98% of Canadian farms are family farms

Almost all of the farms in Canada are family-owned and operated, and producing healthy, sustainable food is their first priority. Remember, farmers feed their own families the food they produce.

Family farms have evolved

They look different today than they did 50 years ago. But that doesn’t mean our food supply isn’t safe and healthy anymore. New technology has allowed farmers to do more with less, making agriculture more sustainable today. Farmers protect the environment because they want to pass their business on to the next generation.

Farming is a complex business

Families must manage food safety and traceability, detailed budgets and accounting, marketing, employees, everchanging technology, and more. Modern farms must be run as a business, and it makes good business sense for many family farms to incorporate. As a company, farms can minimize taxes. Plus, family members can own shares in the company, making it easier to pass the farm from generation to generation. But their business structure doesn’t change the fact that family members work side by side every day, bringing to life their shared passion and dedication for producing safe, healthy food.

We’re in this together

Everyone in the industry needs to work together to help improve perceptions. By being open and proactively communicating with the public about how we grow food and why we operate in the ways we do, we can maintain consumer trust and continue to produce high-quality, nutritious food in ways that are efficient and sustainable.

Social starters

The importance of family is something everyone can understand and relate to, whether you’re in ag or not. It’s common ground that can start a conversation.

Visit AgMoreThanEver.ca/resources to find a collection of photos that you can easily share on social media to start or support conversations about family farming.

The land is my lifestyle and my livelihood, but it’s also my legacy.

Providing safe, healthy food for my family is important to me too.

That’s why I farm.

I love ag for the life it gives my kids now…and the opportunities it gives in the future

Or, even better, share your own pictures and make your story personal.

Photo credit: CR Photography (Chantal Rasmuson) Pictured: Nate and Colin Rosengren

Photo credit: Aimée Ferré Stang

(photo by Jerri Judd)

What are others saying?

“My farm is a family farm. It is 100% owned by myself, my husband and his two parents. We love everything about agriculture with a fierce passion. We have never, ever, sold a product that we wouldn’t happily serve to our children. Every decision on the farm takes more than just finances into consideration. Our number one goal is to leave a farm to our children that is both environmentally and economically viable.”

“Agriculture is a fast-growing business, and it has to be run as a business. It involves family, of course, but we’re always looking at the latest research, we’re looking at what practices are evolving in other countries, and we’re adapting those practices so we can become more efficient to get our product into the marketplace.”

– John Thwaites, Ontario fruit and vegetable grower

– Adrienne Ivey, Saskatchewan rancher

Looking for more?

Watch The power of shared values webinar featuring Charlie Arnot, CEO of the Center for Food Integrity, who shares three simple steps to gain consumers’ trust by tapping into the power of shared values. Charlie helps bridge the divide between science and consumer perception and offers great insight into creating messages that are proven to resonate with consumers.

Visit AgMoreThanEver.ca/tag/webinar

AGvocate Challenge

There are 2.1 million Canadians working in agriculture and agri-food. Imagine the impact we could make if we all made a commitment to improve perceptions of agriculture. There are simple ways you can start being an agvocate today. Just choose to do one of the following:

1. Search the hashtags #FutureFarmer, #AgMoreThanEver, or #Farm365 and find a positive post to retweet.

2. When you overhear a misleading or inaccurate conversation about farming, find an appropriate time to share your story.

3. Dedicate one day to volunteer at an event that promotes agriculture such as Open Farm Days or Ag Literacy Week

4. Tell a friend or co-worker about the need to speak up, and ask them to take the agvocate challenge.

The power of shared values

We a ll sha re t he

a c hai r.

“ The natural environment is critical to farmers – we depend on soil and water for the production of food. But we also live on our farms, so it’s essential that we act as responsible stewards.”

– Doug Chorney, Manitoba

“ We take pride in knowing we would feel safe consuming any of the crops we sell. If we would not use it ourselves , it does not go to market.”

– Katelyn Duncan,

Saskatchewan

“ The welfare of my animals is one of my highest priorities. If I don’t give my cows a high quality of life, they won’t grow up to be great cows.”

– Andrew Campbell,

Ontario

Safe food; animal welfare; sustainability; people care deeply about these things when they make food choices. And all of us in the agriculture industry care deeply about them too. But sometimes the general public doesn’t see it that way. Why? Because, for the most part, we’re not telling them our story and, too often, someone outside the industry is.

The journey from farm to table is a conversation we need to make sure we’re a part of. So let’s talk about it, together.

Visit AgMoreThanEver.ca to discover how you can help improve and create realistic perceptions of Canadian ag.

Nu TRITIONA lly Su PERIOR SP u DS

Evaluating early maturing, coloured potato varieties for health traits.

by Carolyn King

Although many consumers aren’t aware of it, potatoes have a lot of good things going for them when it comes to human nutrition. For instance, potatoes contain vitamin C, minerals, fibre, protein and bioactive compounds, plus they help provide a feeling of fullness that discourages overeating. now an ontario project is identifying some especially healthy potato cultivars that could help win back health-conscious consumers.

The perception that potatoes are not a healthy food choice has resulted in decreased potato consumption and production in Canada, notes reena pinhero, a researcher in the department of food science at the University of guelph. She is leading this project along with rickey Yada, dean of the faculty of land and food systems at the University of British Columbia.

pinhero explains the potato’s bad reputation is based on two factors and she puts those two factors in perspective: “potatoes are generally considered as a carbohydrate-rich food contributing to high calorie intake and causing weight gain. The fact is a potato is mostly water, so if you don’t eat too many, then you will not take in too many carbohydrates or calories.

“The second bad reputation is their high glycemic index reported by some studies. However, potatoes are not that dense, so the glycemic load from an average serving of potatoes is actually not more than any other carbohydrate food.” potatoes tend to have low-medium to high glycemic loads, with the exact value depending on things like the food preparation method, the cultivar and where the potatoes were grown.

The project, which runs from 2014 to 2017, could help boost potato’s health reputation. “The project’s overall objective is to identify early maturing, coloured potato varieties with health benefits (low glycemic index and glycemic load, and high phytochemical antioxidants) and acceptable sensory qualities, that are affordable, accessible to low- and middle-income families, provide a price premium to growers, reduce importation, and provide retailers with local food,” pinhero explains.

The project focuses on cultivars that are both early maturing and coloured because both traits tend to be associated with enhanced nutritional attributes.

“early maturing potato cultivars usually have a lower dry matter and low glycemic index due to a different starch structure. So early potatoes may be good candidates for low glycemic load foods,” pinhero says.

“potatoes generally contain many phytochemicals, such as various polyphenols, flavonols, anthocyanins, carotenoids, vitamins, et cetera. Coloured varieties, especially based on their flesh or skin colour,

contain substantially higher amounts of these phytochemicals. These phytochemicals, which act as antioxidants, have [been linked to] many health benefits, such as providing anti-inflammatory effects and protection from cardiovascular diseases, many cancers and diabetes.”

according to pinhero, early potatoes receive a premium price compared to late maturing varieties, but in ontario at present, early fresh market potatoes are limited to white varieties. “The red and yellow varieties currently grown in ontario don’t mature until September, creating a need for imports.”

along with pinhero and Yada, this collaborative project brings together several other researchers with diverse expertise, including Qiang Liu, rong Cao and Benoit Bizimungu with agriculture and agri-Food Canada (aaFC), and alan Sullivan and andreas Boecker

Reena Pinhero is testing early maturing, coloured potato varieties to see which ones have the best nutritional qualities.

Photo

from the University of guelph. The project’s industry partner is grand Bend produce based in grand Bend, ont.

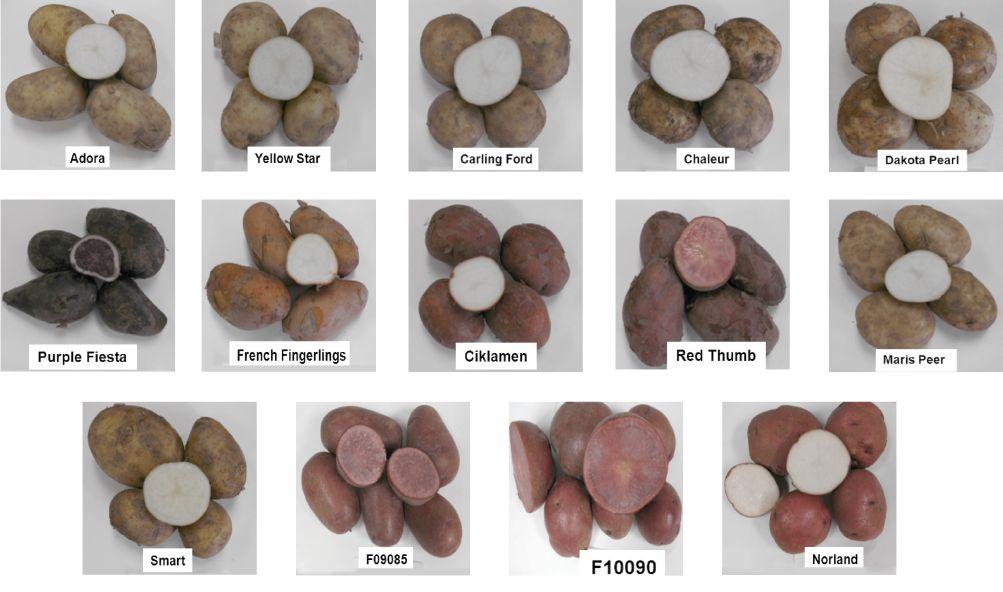

The researchers are currently testing 14 varieties, including two advanced lines developed by aaFC’s Fredericton research and Development Centre. Four of the varieties have coloured flesh and skin, five have either coloured skin or flesh, and the rest have either white or creamy skin and flesh colour.

They are evaluating each variety for protein, total starch, various starch fractions, available carbohydrates, total polyphenols, anthocyanins, flavonols and antioxidant potential.

“The various starch fractions – such as rapidly digestible starch, slowly digestible starch and resistant starch – are evaluated to estimate the glycemic index and glycemic load. The total starch and starch fractions, especially the slowly digestible and resistant starch, are very important as they affect human health by reducing the glycemic load. For example, resistant starch acts as a fibre,” pinhero explains. once the researchers have identified which of the varieties have the best nutritional qualities, they will conduct a sensory analysis of those varieties for consumer acceptance. as well, they are conducting marketing studies in collaboration with Boecker.

So far, they are making good progress on the nutritional analyses. “We have analyzed the various starch fractions and the estimated glycemic index and glycemic load. We have identified 11 varieties that have low-estimated glycemic load, and three that have mediumestimated glycemic load,” pinhero says.

The data from the project’s first year show purple Fiesta, Carling Ford, Ciklamen, French Fingerlings, red Thumb and Yellow Star had the lowest values for estimated glycemic index and glycemic load. next, the researchers will be repeating the analysis of starch, glycemic index and glycemic load, but with fewer varieties and different cooking methods, and they’ll be conducting the phytochemical analysis.

Multiple benefits

“We are excited that this research will bring out potato’s many healthy characteristics so the consumer can make an informed decision of a healthier food choice and the industry will also benefit from it,” pinhero says.

She sees many potential benefits from the project for growers, retailers and consumers. ontario growers will have more choices for early maturing cultivars, along with more opportunities for obtaining the premium price for early potatoes. and, at the same time, they’ll have more choices for nutritionally superior cultivars desired by health-conscious consumers. retailers will have access to a greater variety of locally produced early potatoes and those varieties will be more nutritious. “availability of [local] early maturing, coloured potatoes with health-promoting bioactives, high antioxidant potential, and low glycemic index and glycemic load, would benefit the table potato market, potentially expanding the [ontario] market by $6.6 million,” pinhero says.

The information resulting from the project could be used in efforts to educate the public about the nutritional value of potatoes. Such efforts could contribute to an improved health reputation for potatoes and to increased potato consumption in Canada over time.

Consumers will benefit from more nutritious, low-cost food options.

“a recent study on vegetable cost metrics in the United States shows that potatoes and beans provide the most nutrient value, thereby providing affordable, healthy vegetables for low- and middle-income families,” she notes. “along with lifestyle changes, these healthy potatoes could be part of a variety of healthier food choices for prevention of obesity, Type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease and several forms of cancer.”

Funders for this project include the ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food and rural affairs, the potato Cluster 2 of the agriInnovation program of agriculture and agri-Food Canada, and the ontario potato Board.

Of the 14 cultivars tested in the project’s first year, 11 had low estimated glycemic loads and three had medium estimated glycemic loads. Going forward, the researchers will be repeating the analysis of starch, glycemic index and glycemic loads with fewer varieties.

S COu TS ON IT

Hiring a professional to monitor the crop can save time and money.

by rosalie I. Tennison

Potatoes are a high input, high value crop and ensuring their success should not be left to chance. Certain variables, like the weather, cannot be predicted or controlled, but monitoring the weather can certainly help assess if problems affected by weather can occur. But suspecting there could be a problem is not the same as knowing for certain the crop needs more attention than just a drive-by glance provides.

growers with numerous acres sown to different crops or with fields scattered across many miles may not have the time to monitor each and every facet of their farming operation. Sometimes it pays to hire experts. Many growers understand the value of hiring field scouts to monitor the activity in their fields, to alert them to possible problems and to advise them on solutions.

according to eugenia Banks, an ontario potato specialist, “field scouting is the backbone of a potato integrated pest management program.” In 2015, Banks offered classes on field scouting through the ontario Ministry of agriculture, Food and rural affairs to assist scouts in understanding more about the issues facing potato crops.

“The information collected by scouts is reported to growers who can make important pest control decisions based on their findings,” Banks explains. “a scout can provide timely information on the status of the crop, the level of insect populations and their distribution in the field, incidence of diseases and other problems caused by weather conditions, and potential issues with weed infestation. This information helps growers to time the application of crop protection products, and scouts are able to monitor the efficacy of the pesticide chosen. In addition, field scouting allows growers to do spot treatments for pests, which are possible when pests are concentrated only in specific areas of fields. Spot treatments help growers enhance farm sustainability and environmental protection.”

professional scouts make timely visits to a field to assess aspects of crop development and watch for disease, insects and weeds that could impede that development. By hiring a scout, growers can focus attention on other aspects of the operation, such as preparing storage to accept the crop or ensuring harvest equipment is ready to go to work. For a scout, the main focus is the crop and having a scout regularly walking the field is worth the fee. Most scouts contract to walk a field once a week, but many will visit more frequently depending on potential pest pressures or changes in the weather that could affect pest or disease development.

“Scouts can help prevent diseases because we are in the field at least once a week,” says Karen VanderZaag. She became a scout five years ago when her father hired her to scout his fields near alliston, ont., as a summer job. after discovering she liked the work, she takes Banks’ field scouting update courses annually.

“It’s important for a scout to refresh their knowledge every year and to learn what might be something new to watch for,” she explains.

“It can take an hour with multiple scouts to scout a field, but as much as two or three hours if the field is large or the risk of disease is

VanderZaag takes a close eye to the field, looking for pests, diseases, and anything else that may affect the crop. “My main concern is late blight, but I scout for everything from weed pressure at the beginning of the season to insects throughout the season. In 2015, Colorado potato beetle was identified as a problem early in the season and I considered insect pressure and thresholds before making a recommendation.”

Scouts offer “a close extra look or inspection while walking through the field,” according to VanderZaag. In her observation, not all growers hire scouts, but the benefits are hard to deny. an example of the value a scout can bring to an operation is the need to regularly watch for late blight. “If you don’t have someone scouting your field and you aren’t doing it regularly yourself and you have late blight, it can cross the entire field and will be in the neighbour’s field by the time you notice,” VanderZaag cautions.

Scouts can be hired on an hourly basis or through a crop protection dealer, who may offer scouting services as part of a package that includes custom spraying. For VanderZaag, scouting is her summer job while she completes her education in agriculture. But there are also businesses that offer scouting services. on average, expect to pay close to $6,000 annually for a scout. The value can vary, depending on whether you are hiring hourly or on a contract and how much you expect your scout to do.

Staying current is also part of a good scout’s resumé, which is why many take the courses offered by Banks or other experts. Most growers are too busy to maintain their knowledge of pests and disease identification, and with new pests arriving regularly, getting to know new ones is time consuming. a scout’s job is to know what is new or which old pests may be a problem in any given year.

averting such disasters as crop failure due to late blight, or losses due to a beetle infestation, will likely make up for the cost of the scout. Hiring a scout isn’t just about identifying pests and getting advice on spraying – it also buys peace of mind. Knowing your crop is in good hands is worth the cost.

high. You want to see the disease before it becomes a major problem across the field.”

Field scouting is an important part of managing your potato crop.

WHY ATTEND THE 2016 weed summit?

To gain a better understanding of herbicide resistance issues across Canada and around the world.

Our goal is to ensure participants walk away with a clear understanding on specific actions they can take to help minimize the devastating impact of herbicide resistance on agricultural productivity in Canada.

Some topics that will be discussed are:

• A global overview of herbicide resistance

• State of weed resistance in Western Canada and future outlook

• Managing herbicide resistant wild oat on the Prairies

• Distribution and control of glyphosate-resistant weeds in Ontario

• The role of pre-emergent herbicides, and tank-mixes and integrated weed management

• Implementing harvest weed seed control (HWSC) methods in Canada

MAKE TIME FOR WHAT REALLY MATTERS. CORAGEN® CAN HELP.

You’re proud of your potato crop. Let’s face it. No one ever looks back and wishes they’d spent more time controlling crop damaging, yield robbing insects. We get that. DuPont™ Coragen® is powered by Rynaxypyr ® , a unique active ingredient and a novel mode-of-action that delivers extended residual control of European corn borer, decreasing the number of applications needed in a season. And, if your Colorado potato beetle seed treatment control breaks late in the season, Coragen® can provide the added control you need, so you have time for more important things. Its environmental pro le makes Coragen® a great t for an Integrated Pest Management Program and it has minimal impact on bene cial insects and pollinators when applied at label rates.1 For farmers who want more time and peace of mind, Coragen® is the answer. Questions? Ask your retailer, call 1-800-667-3925 or visit coragen.dupont.ca