GREEN FEED

Joint research project aims to align egg industry’s sustainability priorities.

MADELEINE BAERG

farmers care for the communities they serve.

KAREN DALLIMORE

B.C.’s

BY DAVID SCHMIDT

by Brett Ruffell

Poultry comes together for sustainability

The definition of sustainability seems to vary from industry to industry. One thing each sector shares, however, is that their interpretations have evolved from a focus on environmental impacts to a broader concept that requires a multi-layered strategy. Poultry is no different.

That’s why Canadian Poultry took a wide-ranging approach to this, our sustainability issue. The pages ahead cover everything from the efficient use of resources to the poultry industry’s social and economic impacts and more.

Our cover story on page 12, for example, is a profile of B.C.’s Lockwood Farms. Producers James and Cammy Lockwood recently became the first commercial layer barn in Canada to add black soldier fly larvae to their poultry diets. The insects are billed as a good source of protein that’s also environmentally friendly. In our story, we look at the evidence.

We also assess the chicken sector’s sustainability performance (see page 20) and the impact producers are having on the communities they serve through food bank donations.

And see page 15 to learn about how the egg industry’s research chairs came together to collaborate on a sustainability report. It’s a fascinating look

at how the researchers managed sustainability tradeoffs between their respective areas.

Another collaboration that’s making headway is the Poultry Sustainability Value Chain Roundtable. Established in 2017, the initiative brings policymakers together with industry leaders from the egg, broiler, turkey and hatching egg sectors, as well as their downstream supply chain partners.

Together, they collaborate on common priorities participants identified during a strategic planning session. These

“It is about more than just the environment. It is about the longterm sustainability of the entire Canadian poultry sector.”

focal points include antimicrobial use and resistance, food safety and animal care. The roundtable spawned four working groups tasked with advancing those key areas of concern: The Public Trust Working Group; AMR-AMU Working Group; Global Scan Working Group; and Research Coordination Working Group.

“It is about more than just the environment,” says Roger Peliserro, industry co-chair of the roundtable. “It is about the long-term sustainability

of the entire Canadian poultry sector.”

The group meets about once a year and has conference calls in between those face-to-face gatherings. At its most recent meeting, the group had a cross-sectoral discussion on Salmonella sp. reduction activities. Another highlight was the Public Trust Working Group unveiled ‘The Poultry Story’ – a communications tool that succinctly celebrates positive efforts across the poultry sector around animal welfare and food safety.

Peliserro says having stakeholders from across the poultry value chain collaborate on important issues has been invaluable. “The most significant takeaways from the roundtable are the moments of shared opportunity and learning,” he says.

For instance, he notes that Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC) was the first to roll out a quality mark program. As other poultry groups look to roll out similar programs –like, for example, Egg Farmers of Canada’s recently launched Egg Quality Assurance program – there is an opportunity to draw on CFC’s experience.

Looking ahead, the roundtable co-chair says the biggest sustainability challenges facing the poultry sector will be its ability to respond and adjust to changing consumer demands. “The future belongs to farmers and food producers who recognize that these values are changing and understand the opportunity ahead to ensure the long-term sustainability of our sector through collective action.”

canadianpoultrymag.com

Editor Brett Ruffell

bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

National Account Manager

Catherine Connolly

cconnolly@annexbusinessmedia.com 888-599-2228 ext 231 Cell: 289-921-6520

Account Coordinator

Alice Chen achen@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5217

Media Designer

Brooke Shaw

Circulation Manager

Anita Madden

amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-442-5600 ext 3596

VP Production/Group Publisher

Diane Kleer dkleer@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO Scott Jamieson

President/CEO

Mike Fredericks

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Circulation

Email: rthava@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 416-442-5600 ext 3555 Fax: 416-510-6875 or 416-442-2191

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Subscription Rates

Canada – 1 Year $32.50 (plus applicable taxes)

USA – 1 Year $70.50 USD

Foreign – 1 Year $79.50 USD

GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2019 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

FreeBird Your birds new, favorite song!

As the egg laying industry continues to evolve, equipment manufacturing companies must do the same. At LUBING we are fully aware of our need to progress with the changing industry and that is why our culture of innovation is the reason for our success. LUBING is leading the way by offering a wide variety of products for today’s Cage-Free housing demands as well as bio-security concerns.

Nipple Drinking Systems

Pullets / Layers with and without LitterGuard Cups

Egg Conveying Systems

Curve conveyors customizable to nearly any application Belt Conveyors ranging from 18, 24, 36, and 48 inches (capable of delivering up 600 cases/hr)

Accumulator Tables

Custom-made, all-stainless tables for all situations

Perch Systems

Ergonomic design allows birds to perch comfortably Reduces stress and helps create a calm environment

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664.3811

Fax: (519) 664.3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

Les Equipments Avipor

Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263.6222

Fax: (450) 263.9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963.4795

Fax: (780) 963.5034

What’s Hatching

New national poultry show coming next year

In April, ROI Event Management, the owners and operators of the Canadian Dairy XPO, launched the Canadian Poultry XPO (CPX). The event is a new, nationwide poultry trade show to be held annually. The inaugural CPX is slated to take place November 2020 in Stratford, Ont., and will feature dozens of exhibitors, interactive demonstrations of robotics and innovations, an educational component and networking opportunities.

Well-known ag exec joins tech company

JRS VirtualStudio Inc., a developer of web-based applications and data solutions for the global agriculture sector, appointed Mark Beaven vice-president, sales and marketing. Beaven brings nearly three decades of senior management experience leading a variety of initiatives in Ontario’s agri-food sector, including over 10 years as executive director of the Canadian Animal Health Coalition. In his new position, he will oversee business development and engagement activities for all of JRS VirtualStudio’s agri-tech enterprises, including Transport Genie and Trespass Tracker.

OMAFRA takes big budget hit

Ontario’s 2019 budget, unveiled in April, includes a mix of investments in rural communities and cutbacks. One area that took a big hit was the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), whose budget will be cut by $200 million in 2020. While OMAFRA’s interim budget for 2018-2019 is $1.1 billion, it’s down to $839 million in 2019/2020. On the plus side, the province is investing millions in rural broadband technology.

Premium coming for enriched egg production

10 cents/doz. is the premium Ontario egg farmers have been receiving for enriched egg production since January 2017.

As Canada’s egg industry works to phase out conventional cages by 2036, producers who’ve yet to make the transition have an important decision to make –whether to convert to enriched housing or go cage-free. A recent announcement is sure to impact that choice for some farmers.

11 cents/doz. is the premium farmers across Canada will be paid for enriched egg production starting in September.

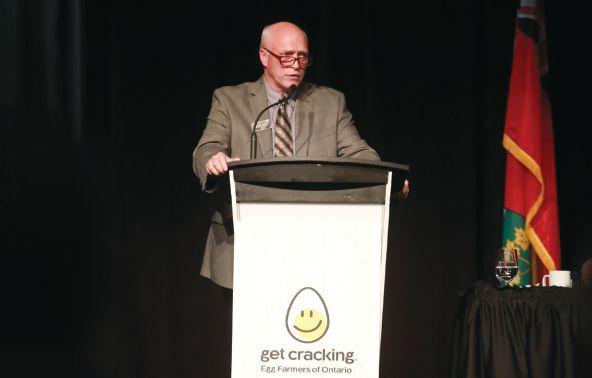

At Egg Farmers of Ontario’s AGM in Niagara Falls, Ont., chair Scott Graham revealed Canadian producers would soon be getting paid a premium for enriched egg production.

“Since the cost of production that determines egg prices is based on cost surveys for the predominant conventional system, we needed to develop transitional pricing to ensure fair compensation to egg farmers that are retooling, and to send the correct price signals to those making decisions about layer housing on their farms,” Graham said.

“A national committee to deal

with that issue has settled on a differential of 11 cents and this will be the net price difference in the farm price for eggs produced in enriched housing across Canada beginning this September.”

Notably, egg farmers in Ontario have already been receiving a 10 cents/doz. premium for enriched production since January 2017.

Manitoba farmers used to receive a premium as well, albeit a more modest one. At one point they received a four cents/doz. bonus, which was reduced to two cents and then phased out completely at the end of 2018.

The change is expected to make a significant difference in provinces that currently lack such a payment.

Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) notes that down the road industry stakeholders now plan to conduct a broader analysis for other production systems.

Eggs for breakfast benefits those with diabetes: study

While some cereals may be the breakfast of champions, a University of B.C. (UBC) professor suggests people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) should be reaching for something else.

Associate professor Jonathan Little, who teaches in UBC Okanagan’s School of Health and Exercise Sciences, published a study in April demonstrating that a high-fat, low-carb breakfast can help those with T2D control blood sugar levels throughout the day.

“The large blood sugar spike that follows breakfast is due to the combination of pronounced insulin resistance in the morning in people with T2D and because typical Western breakfast foods – cereal, oatmeal, toast and fruit – are high in carbohydrates,” Little says.

Breakfast, he says, is consistently the ‘problem’ meal that leads to the largest blood sugar spikes for people with T2D.

His research shows that eating a low-carb and high-fat meal first thing in the morning is a simple way to prevent this large spike, improve glycemic control throughout the day, and perhaps also reduce other diabetes complications.

Study participants with well-controlled T2D completed two experimental feeding days. On one day they ate an omelette for breakfast, and on another day, they ate oatmeal and some fruit. An identical lunch and dinner were provided on both days. A continuous glucose monitor – a small device that attaches to your abdomen and measures glucose every five minutes – was used to measure blood sugar spikes across the entire day. Participants also reported ratings of hunger,

fullness and a desire to eat something sweet or savoury.

Little’s study determined that consuming a very low-carbohydrate high-fat breakfast completely prevented the blood sugar spike after breakfast and this had enough of an effect to lower overall glucose exposure and improve the stability of glucose readings for the next 24 hours.

“We expected that limiting carbohydrates to less than 10 per cent at breakfast would help prevent the spike after this meal,” he says. “But we were a bit surprised that this had enough of an effect and that the overall glucose control and stability were improved. We know that large swings in blood sugar are damaging to our blood vessels, eyes and kidneys.

“The inclusion of a very low-carb high-fat breakfast meal in T2D patients may be a practical and easy way to target the large morning glucose spike and reduce associated complications.”

He does note that there was no difference in blood sugar levels in both groups later in the day, suggesting that the effect for reducing overall post-meal glucose spikes can be attributed to the breakfast responses – with no evidence that a low-carb breakfast worsened glucose responses to lunch or dinner.

“The results of our study suggest potential benefits of altering macronutrient distribution throughout the day so that carbohydrates are restricted at breakfast with a balanced lunch and dinner rather than consuming an even distribution and moderate amount of carbohydrates throughout the day.”

Coming Events

JUNE 2019

JUNE 9-11

CPEPC AGM and Convention Victoria, B.C. cpepc.ca/convention2019.html

JUNE 25

PIC Health Day

Stratford, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

JULY 2019

JULY 15-18

PSA Annual Meeting Montreal, Que. poultryscience.org

SEPTEMBER 2019

SEPT. 4

PIC Golf Tournament Baden, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

SEPT. 10-12

Canada’s Outdoor Farm Show Woodstock, Ont. outdoorfarmshow.com

SEPT. 22-26

IEC Global Leadership Conference, Denmark internationalegg.com

SEPT. 23

PIC Science in the Pub Guelph, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

OCTOBER 2019

OCT. 1-3

Poultry Service Industry Workshop Banff, Alta. poultryworkshop.com

OCT. 9-10

Alberta Livestock Expo Lethbridge, Alta. albertalivestockexpo.com

UBC associate professor Jonathan Little found that a high-fat, low-carb breakfast can help those with type 2 diabetes control blood sugar levels throughout the day.

Guts of Growth

By Dr. Kayla Price

Heat stress in poultry

After a long winter across Canada, summer and higher temperatures are approaching. That means it’s important to be prepared for the heat and the impact this could have on your birds.

What is heat stress?

Birds have a thermoneutral zone where a range of ambient temperatures allows them to regulate a normal internal body temperature through just heat loss and heat production. For example, the body temperature for chickens is 41.5°C (106.7 °F), turkeys is 41.2°C (106.°F) and ducks is 42.1°C (107.8°F).

Birds naturally produce their own body heat through metabolism as the byproduct of different internal biological processes. The amount of body heat they produce can be affected by many factors including body weight, production, activity and feed intake.

The perceived temperature the bird feels is impacted by relative humidity and environmental temperature, and when these factors rise, they can experience heat stress.

High humidity can make lower temperatures seem warmer than they are, and as a result heat stress may also happen at slightly lower temperatures if there is a higher relative humidity.

Not only can intensity and duration of exposure to heat stress play a role in how birds react, but so can other compounding factors.

Aggravating elements could include age, cyclic variation in temperature, body type and size and genotype.

How do birds manage excess heat loss?

Unlike humans, birds do not have sweat glands, so they release heat through convection, conduction, radiation, evaporative cooling and vasodilation. Birds lose heat through convection where heat rises off the body of the bird to the cooler surrounding air. In a heat stress situation, the birds may increase this type of heat loss through increasing their surface area via spreading their wings.

When birds lose heat through conduction, they transfer heat from one surface in direct contact with another surface. Essentially, the bird can sit on a floor or by a wall that may be slightly cooler than their body temperature to help release the heat. In a heat stress situation, birds may seek the perimeter of their environment. With birds reared on litter, this may mean that the birds seek out the walls or dig into the litter. With radiation as a heat loss method, heat can be transferred to a distant

surface or object.

Vasodilation is a method of heat loss where the blood vessels that are close to the outside of the body, such as in the comb and wattles of the bird, become wider and allow more blood to flow. This increase in blood flow near the outside of the body brings the internal body heat to the surface to be lost.

Evaporative cooling is another method of heat loss where the bird completes rapid, shallow breaths with their mouth open to release water from the mouth and respiratory tract to help remove heat from this surface. Panting requires muscle activity and energy use which can generate body heat, but slow panting allows for a balance between the heat produced and the heat lost.

On the other hand, fast panting (up to 10 times the resting rate), which may happen in high heat stress conditions, does not allow for this balance and is not sustainable. This fast panting requires increased muscle activity and energy use

Increasing ventilation during high heat periods and using cooling systems like the one pictured here are some of the critical first steps to help manage heat levels in the barn.

Dr. Kayla Price is poultry technical manager for Alltech Canada and is an expert in poultry intestinal health.

POTENTIAL

Guts of Growth

which can tire the birds (decrease production), alter gas, pH and electrolyte balance, and increase body heat due to the increased muscle activity. In high heat stress conditions, body heat production may decrease as feed consumption, activity and production decrease

Impact of heat stress on the bird

Heat stress can have negative impacts on many of different aspects of the bird’s function, but this article will only discuss the impact on the immune system and gut. Under thermoneutral conditions, stress molecules within the bird are balanced and different molecules help to regulate body temperature and metabolic activity. In heat stress conditions, some stress molecules may be increased, leading to an imbalance.

In humans, the imbalance and increase in stress molecules have been shown to have an impact on behaviour, heart rate, blood pressure and appetite. These stress molecules have also been shown to decrease immune function. This suppression of the immune system during heat stress has also been found in broiler and layer research. The immune system acts as the body’s defense system so if this protection is reduced, the bird may be more vulnerable to other stressors and changes.

Another area can be impacted during heat stress is the intestinal tract. Under heat stress conditions, the blood flow is decreased to the intestinal tract, which in turn decreases oxygen delivery to the tissue. This decrease in oxygen levels may lead to oxidative stress which can be damaging to tissues and organs. Oxidative damage can also impact tight junctions which connect adjunct intestinal cells and provide a protective barrier.

If the tight junctions are damaged or negatively impacted the intestinal tract cannot act as a good barrier. This damage can also lead to other issues such as increased inflammation, decreased ability of the intestine to absorb nutrients and may change the intestinal environment which could impact the intestinal microbe balance. In high heat stress conditions, the birds may reduce their feed intake which could have a further impact on the intestinal tract.

Managing heat stress

Elements to take into consideration to manage heat stress, include barn environment, feed and water management, as well as different additives that can be used in the water and feed. In the barn, increasing ventilation during high heat periods and using cooling systems are some of the critical first steps to help manage heat levels.

Generally, birds drink around 1.6 to two times as much the equivalent weight of feed, but with increased panting and water loss through skin during heat stress the birds need to replenish this water by drinking more than non-stressed birds. It is important to make sure birds have access to cool (below 25°C ), clean water during times when temperatures and humidity are high. Adding electrolytes, flavours and organic acids can help encourage water consumption during these times. Other additives, like mannan oligosaccharides or bioavailable minerals, can help support the intestine’s natural defenses in heat-stressed birds, especially when feed intake has decreased. These additives may be used at strategic times such as during brooding and just before and during a heat stress time. Similar additives may also be used in the feed over time as another proactive approach.

When relative humidity and environmental temperature rise, birds can experience heat loss.

In addition, activity of the birds should be limited during the hottest times of the day. Birds placed in cool spring temperatures and raised through the heat of summer may experience more issues with heat stress as so it’s important to be prepared for that first heat wave. To help beat the heat and reduce the stress on the birds, assess the barn environment, water quality, feed management as well as additives for water and feed to help keep the birds comfortable during the heat.

Due to water loss, heat stressed birds drink more than non-stressed birds.

FRESH THINKING

You’re in the business of raising healthy birds. Cumberland ventilation is engineered with fresh thinking and customized for your operation. So, you can be confident in the well-being of your environment and your flock.

Cumberland’s highest performing fan features a springloaded butterfly door with a magnetic locking mechanism for a complete seal. The flush-mount design makes it easy to retrofit over wall openings from 57.5” to 63”.

Find your local expert at cumberlandpoultry.com and customize your new or retrofit ventilation solution.

Black flies, green feed

Lockwood Farms turns to insects in search of a sustainable protein source for its flock.

By David Schmidt

James and Cammy Lockwood of Lockwood Farms on Vancouver Island share a deep concern about the future of the planet. This inspired the couple to become the first commercial layer farm in Canada to include black soldier fly (BSF) larvae in their poultry diet. That innovation has led to the millennials being named B.C.’s Outstanding Young Farmers in March.

James grew up on a wholesale nursery but didn’t see that in his future. He was on his way to a career with the RCMP when he and his wife, Cammy, decided to grow a few vegetables and raise a few chickens to feed their soon-to-be family. They were instantly hooked on farming.

In 2011, James convinced his father, Barry, to let him grow a few rows of vegetables on a rundown property the family had acquired, which he and Cammy then sold at a local farmers market. Thus, Lockwood Farms was born.

At the same time, they converted an old shed into a home for 16 laying hens. That flock soon grew to 399 hens and a larger barn. Vege -

table production also expanded and the Lockwoods now grow over two acres of vegetables, salad mixes, tomatoes and peppers in both poly greenhouses and open fields.

Their foray into egg production got a huge boost in 2015 when they received a 3,000-bird quota in the B.C. Egg Marketing Board new entrant lottery. They have since acquired additional quota and now have 4,700 layers.

To accommodate the larger flock, they built a new barn with mirror image sides. Each side has a scratch floor and access to an outdoor range. Doors are manually operated so the Lockwoods can maintain an accurate record of outdoor access.

Feed, water, nest boxes and roosting areas are located on a slatted floor almost four feet higher than the scratch floor. Perch rails spaced 18 inches apart help the birds move up and down.

Environmental benefits

The big question was what to feed them. “I was trying to think more sustainably,” Cammy says. “I had read that soybean production was destroying the Amazon rainforest and didn’t want to contribute to that. ‘What are you doing [to help the environment]?’ is a question we’re often asked and I wanted to have an answer.”

The Lockwoods decided to feed their flock a GMO and soy-free diet but finding a protein source was difficult. A Google search led them to Enterra, a small feed company in Langley, B.C., that was starting to rear BSF larvae as a feed for poultry,

fish and pets. “We had to wait for them to get (Canadian Food Inspection Agency) approval before we could start using it in our feed,” Cammy says.

Enterra’s vice-president of operations, Victoria Leung, notes an adult BSF has no mouth to eat with. That means the larvae must store enough protein and fat to sustain the flies during their five to seven-day adult lifespan. As a result, mature BSF larvae are “40 per cent protein, 40 per cent fat, a natural source of methionine and super high in calcium and loric acid,” Leung says.

She notes the environment benefits because larvae are raised on a substrate of recycled food and grain byproducts, diverting foodwaste from landfills by recycling it into animal feed. Since the foodwaste is not certified organic, BSF larvae are not a certified organic animal feed. Interestingly, BSF larvae are permitted in the organic aquaculture standards.

Cammy notes feeding insects to poultry is perfectly natural since that is what free-range chickens dig for when they forage. She has become an evangelist for insect protein, stating “an acre of soy will only produce about 350 pounds of edible protein but an acre of insects have the potential to produce 100,000 pounds of usable protein.”

The cost factor

Nutritionist Everett Dixon of Top Shelf Feeds says the Lockwoods’ insistence on a GMO, corn and soy-free ration presented some significant constraints that BSF

The Lockwoods started with 16 laying hens housed in a converted old shed and now have 4,700.

helps to meet. “BSF brings energy and protein to the ration,” he says, explaining the ration is wheatbased supplemented with peas, extruded flax, calcium, phosphorus, minerals and vitamins.

“It’s a tight ration and there are some compromises with it,” Dixon adds, admitting that, “because of the ingredients and constraints it’s more expensive.” He did not say how much more expensive but Elijah Kiarie, the McIntosh Family professor in poultry nutrition at the University of Guelph, reports he paid $8/kg for BSF he purchased for a research project.

He says that, “to use insect meal in a feed formulation based on cost, [it] needs to be below $1/kg.”

Both Enterra and the Lockwoods readily admit the cost is much higher than a conventional layer

ration. Leung notes BSF is “still a premium ingredient. Today, it’s not really a commodity product but over the long run we will see the price come down.”

“We’re Enterra’s only commercial layer account,” James explains. “We are the guinea pigs and it does cost us.”

The Lockwoods recover those costs by self-marketing to restauranteurs who share their philosophy. “We set our prices based on the cost of producing the eggs, grading, packaging and labour. We aim to get similar returns as other egg farmers.”

Impact on performance

The price may be a major stumbling block for most commercial producers, but egg production should not be. The Lockwoods believe they are

getting similar production to other free-range flocks. That said, they note they are just completing their first full flock on the BSF diet. As a result, they don’t yet have the data to back up their assumptions.

However, Kiarie’s research indicates BSF could replace soybean meal in egg layer diets without too many adverse impacts. He and a research student recently completed a study to evaluate egg production, select internal egg quality and feed conversion in birds fed BSF larvae.

Forty-one per cent of soybean meal was replaced by BSF during weeks 19 to 27, while BSF larvae replaced all the soybean meal in weeks 28 to 43. During the first phase, the BSF larvae improved yolk colour, shell breaking strength and shell thickness. Hen-day egg

2018 is the year Enterra received regulatory approval for use of its whole dried black soldier fly larvae as a feed ingredient for poultry

40% is the product’s protein content

1,000,000% is the weight growth of larvae in under three weeks

0 additional water added to their diet

0 arable land required

0 methane produced

In search of an environmentally-friendly feed source, James and Cammy Lockwood added black solder fly larvae to their poultry diet.

Black soldier fly larvae by the numbers

Lockwood Farms is the first commercial layer barn to add Enterra’s black soilder fly larvae product, called EnterraGrubs, to its feed. Here are some key figures about the product.

production and egg mass were comparable to soybean meal-fed birds. However, the BSF increased feed intake, leading to a poorer feed conversion ratio.

There was also no impact on hen-day egg production during the second phase. The full BSF diet did reduce egg mass but increased yolk colour, shell strength and thickness. Kiairie says further research on nutrient digestibility is needed to improve the feed conversion ratio.

“Based on our research, [BSF] can be a good protein feed for laying hens,” Klairie states, adding, “we need to understand why we see a reduction on egg weight and an increase in feed intake. These two parameters will negatively affect feed conversion.”

“Based on our research, BSF can be a good protein feed for laying hens.”

The way forward

Klairie says future poultry nutrition research needs to focus on improving the digestibility of feed ingredients. “Any nutrient poultry is not able to digest ultimately affects chicken house environment and nutrient leaching. Currently, chickens excrete about 15 to 20 per cent of the nutrients we feed them.”

He thinks the answer lies in fortifying poultry feed with amino acids. “It is possible to reduce inclusion of feed proteins such as insect protein [or] soybean meal [with use of] pure amino acids.”

Meanwhile, the Lockwoods are looking at other innovations to enhance their poultry production. As an example, they are considering planting kiwi in their range. The kiwi would not only provide additional revenue but, more importantly for the birds, provide summer shade as well as protection from predators.

Collaborative roadmap

Joint research project aims to align egg industry’s sustainability priorities. By

Madeleine Baerg

What will keep the Canadian egg industry healthy and sustainable into the future? Egg Farmers of Canada’s four research chairs – an ecological economist, an animal welfare scientist, a behavioural economist and a public policy researcher – recently combined efforts to start to answer exactly that question.

Their collaborative paper, titled ‘Sustainability in the Canadian Egg Industry – Learning from the Past, Navigating the Present, Planning for the Future’, was published in the journal Sustainability in September 2018. It marks a clear departure from isolated, single-discipline study. More research roadmap than production how-to guide, the paper is a vital first step towards positioning the egg industry for success into the future.

“The idea was not to advance a concrete set of recommendations for what farmers or Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) should

do,” says lead author Nathan Pelletier, research chair in sustainability at the University of British Columbia. “This paper was the first effort of all four research chairs towards beginning to articulate our common ground, to defining what are the most interesting opportunities to collaborate, and where are the clear intersections and overlaps looking forward.”

“The discussions we had [throughout the creation of the paper] raised a lot of questions,” adds Maurice Doyon, the egg industry economics research chair at the Université Laval. “That was our objective. You can read [the paper] and see it as our research agenda for the next five years. It’s not typical to raise all these questions and not have answers. But, it’s also not typical to have four specialists with four very different backgrounds and areas of interest collaborating in this way.”

CONFLICTING DEMANDS

Sustainability is difficult to calculate be -

cause it can be defined according to many measuring sticks and depends enormously on perspective.

An animal welfare scientist would typically define sustainability in terms of animal health and welfare markers such as disease outbreak management or evolving husbandry best practices.

An economist would generally think in terms of financial sustainability: one’s ability to react to changing input costs, shifting markets and evolving efficiencies. An environmental scientist would prioritize different parameters again: carbon and water footprints, waste production, input efficiency and run-off concerns.

The biggest challenge to a practical discussion about sustainability is that there is often conflict between various criteria. Consider, for example, that according to a recent study cited in the paper, upwards of 70 per cent of U.S. consumer respondents reported believing that a move from conventional to cagefree housing would have a positive impact

Egg Farmers of Canada’s four research chairs came together in search of viable answers to sustainability questions.

on hen health, hen behavior, natural resource use efficiency, worker health and safety, food safety and egg quality.

Science, however, points towards trade-offs: in many cases, the shift to cagefree may actually have negative impacts. For example, Doyon says, organic egg production requires more energy than conventional production because the lower hen density requires more supplemental heating of the barn, increasing the carbon footprint.

While meeting shifting consumer preferences is one of the key determinants of economic sustainability, doing so in this case would have negative impacts on multiple other aspects of industry sustainability. According to the joint paper, meaningful research into egg industry sustainability requires a multi-disciplinary approach that weighs various sustainability trade-offs against each other.

“Sustainability by nature is, first, an applied science and, second, so multi-faceted. The practical challenge facing the Canadian egg industry is that there are so many interactions between these various components of sustainability and so many desired outcomes. Research efforts really need to be undertaken on an interdisciplinary basis,” Pelletierexplains.

“Ultimately, I’m very cognisant that if I advance recommendations about environmental outcomes without consid -

ering animal welfare or economic tradeoffs, I’m not providing information that is actionable or that will support the industry going forward.”

AN INNOVATIVE SOLUTION

Part of the solution to aligning various sustainability priorities may lie in creating systems to value them by the same measuring stick. For example, Doyon says, if animal welfare could be monetized, economic and welfare sustainability would more naturally align.

“If you take a plane tomorrow, you can cancel out the carbon units [you’ll use] by

purchasing carbon credits from a market today. Some people have an idea – this idea doesn’t originate from us – of creating a market for animal welfare. Some farmers ‘produce’ more animal welfare.

“They could sell those credits to people who are worried about animal welfare. If you give your money to an animal welfare organization, there is a lot of friction – a lot of loss. Only a fraction of your money will actually go towards creating improved animal welfare. If you give directly to a farmer, you get a lot of welfare for your dollar.”

LOTS OF UNKNOWNS

While inter- and multi-disciplinary research is always valuable, the large-scale transition currently underway towards alternative layer housing makes collaborative research more vital than ever.

“When cage-based production was the norm in the industry, when the production system was fairly stable over a long period of time, multi-faceted research was less essential because there were not so many unknowns,” Pelletier explains. “Now, the industry is in the midst of housing system transition and a steep learning curve.

“What we tried to point to [in this paper] is why and where interdisciplinary

Lead author Nathan Pelletier is research chair in sustainability at the University of British Columbia.

Maurice Doyon is the egg industry economics research chair at the Université Laval.

research is necessary because we know there will be trade-offs, especially in the short term. We need to consider how the industry has come to the point it is at, what the challenges are that it currently faces largely because of changing societal expectations and looking forward what curveballs may be coming.”

The housing system shift is not the only change that could significantly impact the egg industry and for which multidisciplinary research collaboration is vital. According to the paper, some of the biggest future unknowns include: Whether supply management survives in its current or any form; in what direction societal demands and public policy shift; whether disruptive technologies like 3D food printing become mainstream; and how emerging technologies might impact resource use efficiency and, more broadly,

“We cannot do this kind of work without the willingness of farmers to be open and involved.”

farm economics.

Despite being written by four high level researchers, the paper – and, ultimately, any projects inspired by the paper’s many questions – is not intended to be solely academically focused.

“This isn’t ivory tower research,” Pelletier says. “We are generally looking to do research that can be put into practice and that can ultimately result in better, more sustainable and more profitable production.”

To that end, both Doyon and Pelletier respectfully request continued farmer support and collaboration.

“The most important thing egg farmers can do to enable the work we’ve identified in this paper is to be willing to collaborate directly with us, to welcome us onto their farms, to allow us to have insight into their management,” Pelletier says. “We cannot do this kind of work without the willingness of farmers to be open and involved.”

Sustainability:

It’s in everything we do

For Canadian egg farmers, sustainability is a way of life. We’ve been focused on responsible care of our land, animals and communities for generations. We’re always looking for new ways to improve our processes, to provide the fresh, high-quality eggs that Canadians love.

Learn more about our Sustainability Story at eggfarmers.ca

Social sustainability

How chicken farmers care for the communities they serve.

By Karen Dallimore

When companies and organizations talk about sustainability, they generally focus on three different aspects: environmental, economic and social. Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC) released their Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for the Canadian chicken industry in 2018, providing a glimpse of the chicken industry over the past 40 years in all three categories.

So far, so good

It seems the poultry industry has been doing a good job so far of looking after environmental sustainability. Based on data gathered from 300 farmers across the country along with over 60 businesses in the supply chain, the findings reflect significant progress.

In the last 40 years, since 1976, the carbon footprint associated with chicken production has decreased by 37 per cent, while water consumption and non-renewable energy use have declined by 45 and 37 per cent, respectively.

Economically, healthy benchmarking figures show that Canada’s 2,803 chicken farmers and 191 processors sustain 87,200 jobs, contribute $6.8 billion to the GDP, pay $2.2 billion in taxes and purchase 2.6 million tonnes of feed.

Defining social sustainability

Beyond the environmental and economic impact, chicken farmers and their business partners contribute to the well-being of the communities in which they operate. This is social sustainability:

looking after people.

For CFC, social sustainability involves adherence to their Raised by a Canadian Farmer On-Farm Food Safety Program (OFFSP) and Animal Care Program (ACP), two national, mandatory and third-party-audited programs ensuring farmers achieve high standards when it comes to animal care and food safety.

On the processing side, all federally registered processing plants are compliant with animal welfare regulations enforced by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

On the farm, social sustainability also

means providing safe and competitive working conditions, including training, supervision and protective equipment on the job.

It means establishing clear procedures to follow in case of an incident as well. In short, looking after workers.

Over 90 per cent of Canadian chicken farmers provide a salary over provincial minimum wage, an important factor in attracting and retaining farm employees.

Another piece of the social sustainability puzzle involves giving back to the community.

Chicken Farmers of Canada has supported the Ottawa Food Bank since 2007.

At

YOUR SUCCESS IS OUR SUCCESS

Our world is all about you.

Ninety percent of respondents had contributed to their communities, through volunteering, being involved with municipal or regional organizations or providing educating and outreach.

Feeding communities

Feeding those in need has become an important component of social sustainability. For its part, CFC has supported the Ottawa Food Bank since 2007, in turn supporting 114 local agencies to

feed 38,400 people each month, 36 per cent of which are children. “We believe that every Canadian should have access to a healthy source of protein, and we believe that we can make a contribution to help make that happen,” says Lisa Bishop-Spencer, CFC director of brand and communications.

In 2018, their annual Chicken Challenge food donation program provided $50,000 worth of frozen chicken products to the Ottawa Food Bank. This was the ninth successful year of the program, which solicits bids for frozen chicken products from a Canadian processor to be donated to the food bank.

“We believe that every Canadian should have access to a healthy source of protein.”

In addition, $4,500 was collected through year-long staff donations and 50 per cent matching CFC donations. Altogether, nearly $54,500 was donated in 2018.

This brings the total contribution to the food bank since CFC became partners and supporters in 2007 to over $544,500.

The Chicken Farmers of Ontario (CFO) has also embraced the opportunity to give back to their communities through the CFO Cares: Farmers to Food Banks Program that began in January 2015.

Patricia Shanahan, the program coordinator, explained that CFO’s partnership with Feed Ontario (formerly known as the Ontario Association of Food Banks) allows farmers to donate up to 700 kg of chicken each year – that’s 300 birds – to help fight the food insecurity

continued on page 36

Cooling

Lighting

Submetering

Assessments

Peak Shaving

IDEAS SET IN MOTION

There are a number of things producers can do to become more energy efficient. In this guide, experts share simple ways to save on energy as well as more advanced approaches. The supplement also includes updates on the latest technologies.

HOW TO OPTIMIZE ENERGY USE

What producers can do to use heat and electricity more efficiently.

By Treena Hein

The phrase ‘energy efficiency’ in a poultry industry context likely brings to mind shining rows of LED lights. It’s true that an increasingly large number of Canadian poultry farms have LEDs now.

Heat exchangers are another way poultry farmers – especially broiler farmers – are becoming more energy efficient. These systems recover heat that would have been exhausted to the outside through normal ventilation practices, and we’ve devoted an entire story in this issue to their design advancements (see page 29).

To determine which other energy efficiency technologies or strategies producers should consider, Canadian Poultry checked in with leading experts.

Farah Kanani and Yang Li note that demands for heating and ventilation can be reduced by optimizing the barn envelope (for example, building a barn with the right orientation to the sun, minimizing air infiltration). Interior factors such as weight of birds and air quality are also important.

Kanani and Li are graduate students of Nathan Pelletier, assistant

professor at the University of British Columbia and NSERC/Egg Farmers of Canada industrial research chair in sustainability. This year, they will complete a review of published studies on energy efficiency approaches in the poultry industry, identifying best technologies and management strategies on the farm and along the entire egg supply chain.

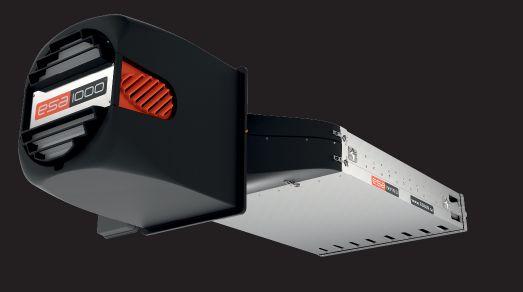

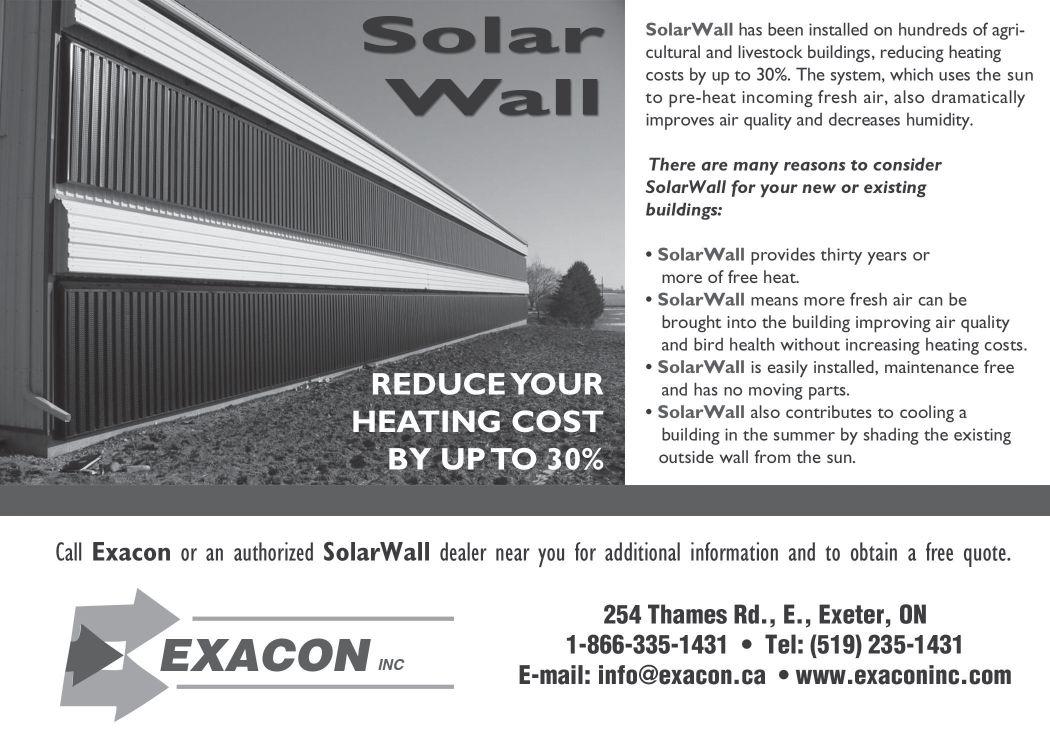

Solar pre-heating walls, which use unglazed solar collectors, are a passive way to reduce barn heating requirements over the cooler months of the year. These systems also contribute to cooling a building in summer by providing shade to an outside wall. Kanani and Li note that the air which enters through small openings in the outer wall can be pre-heated (in the space between the outer wall and the barn) by 15 to 20°C before it’s

ducted into the barn.

A case study of an Ontario egg farm with one of these systems done by SolarWall’s engineering arm concluded that it provided the barn on this particular farm with a total heated air volume of 20,000 ft3 per minute and provided a payback time of five years. However, individual farm ROI would obviously depend on many factors, including weather patterns each year.

Submetering and energy assessments

If you’ve already looked at solar pre-heating air systems and heat exchangers, minimized infiltration, optimized your equipment, installed LEDs, optimized insulation and are keeping motors and fans clean, a next useful step is a total farm energy assessment. This

Solar pre-heating walls, which use unglazed solar collectors, are a passive way to reduce barn heating requirements over the cooler months of the year.

New ECO model

Self cleaning

Built in cooling

Highest efficiency fans on the market

*As rated by BESS labs

Low or no-cost ways to save energy

The following points are summarized from Saving Energy on Your Farm BC Poultry Farms by B.C. Agriculture & Food.

• Use high efficiency motors in fans .

• Ensure fans are clean, balanced and otherwise in good condition.

• Use external wind covers on fan openings to prevent drafts during cooler periods.

• Repair or upgrade fan louvers to ensure they seal properly when closed.

• Repair building leaks to reduce winter air infiltration.

If they haven’t already, poultry farmers should also create at least one windbreak on the farm (also called a shelterbelt). Windbreaks reduce wind velocities and affect wind currents, leading to reduced snow removal costs (by controlling blowing snow), lower building energy consumption and much more.

analysis of energy use throughout an entire operation by an outside expert can also include a close look at various modification options.

Full energy assessments include detailed load analysis using submetering: measuring electricity being used in a circuit, piece of equipment, entire building or another operational unit. To accomplish this, energy assessment companies temporarily install submeters to collect a few weeks of data. Some farms take it even further and permanently install a few sub-meters to gather data on an ongoing basis.

The data that’s gathered can inform the practice of peak shaving – using less electricity during hours when it’s most expensive (peak rate times) or reducing demand usage peaks (some electricity agencies charge higher rates for usage above certain levels). Peak shaving or demand shaving is obviously possible only in areas with different electricity rates throughout the day or peak demand billing.

An example of peak shaving on a poultry farm might involve scheduling, when possible, egg collection and processing, or feed/manure belt operation, so that it occurs when electricity rates are lower or when another operation is not occurring. However, experts note that any change in practice must be put in place permanently to gain benefits on your bill in the case of demand shaving. That’s because billing usually reflects the very highest peak use during a 12-month period.

Total savings of peak/demand shaving will obviously depend on the operation’s distribution tariff structure and what changes are made. That said, experts believe

most farms that operate above their contract demand level have an opportunity to save money by doing it.

Cost of an assessment

Numerous provinces offer funding for on-farm energy efficiency improvements, including energy assessments. Alberta for example, has offered funding for equipment upgrades, energy assessments and submetering activities for a few years, but as this story went to print, it was not possible to say which programs would be continued due to the recent election.

SaskPower has funding for various business customer energy efficiency projects. Manitoba Hydro offers financing for upgrades to gas and electrical systems on farms and more. And B.C. offered many opportunities from 2012 to 2018 through B.C. Agriculture Climate action. The province also still offers a free online B.C. Farm Energy Assessment Tool but does not track uptake numbers or type of farm that use it. There are also energy assessments being supported under the Environmental Farm Plan in B.C.

Hydro Quebec has a long list of efficiency opportunities that are eligible for funding on farms, from LED lighting to solar pre-heating systems. Efficiency Nova Scotia has an on-site energy manager for the agriculture industry who will review projects and provide farmers with step-by-step guidance on how to become more energy efficient. New Brunswick Agriculture and NB Power offer funding for on-farm energy efficiency audits and more.

However, it’s quite affordable to get assessments

Some provinces provide funding for energy efficient upgrades like installing LED lights.

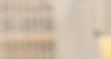

with ESA-1000 heat exchangers

Calculate your payback at esair.ca or contact our Sales Director Randy Taylor 1 (855) 573-2877

done without any funding. The cost varies depending on the level of detail, size of farm and more, notes Ron MacDonald, who is a semi-retired agriculture industry engineer who owned his own Ontario-based consulting firm called Agviro for decades and has done many farm energy assessments.

A basic walk-through of one barn, which takes a few hours and involves identification of issues and providing recommendations, costs at least $1,000. The payback for that, MacDonald says, can be virtually instant or at worst, within about a year. “We always find at least one thing,” he says.

A more detailed level two analysis (including ROI on recommended changes and computer simulations) starts at $4,000, and a level three analysis that includes submetering at a farm with multiple barns costs $6,000 to $10,000.

These level two and three assessments are often done, MacDonald explains, as

part of a process involving major upgrades. Therefore, ROI for the assessment itself is blended into the ROI for all the upgrade investments.

A little over a year ago, Deerfield Hutterite Colony in Magrath, Alta., had an energy assessment completed (paid for by covered under a funding agreement Egg Farmers of Alberta had with the funding program Growing Forward 2) and installed submeters at the barn level (paid for the Alberta government under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership program, which covers the cost of up to three energy meters per farm) a little over a year ago.

The free-run layer barn and pullet barn were new builds in 2017 and share a natural gas boiler heating system with some in-floor heating and some overhead heaters in both barns.

Barn manager Simon Waldner says electricity use for both barns in winter 2017/2018 and winter 2018/2019 was similar. A little less use has resulted from one of the energy

assessment recommendations to put a timer on the pump, which delivers hot water to sinks so it runs 10 minutes every couple of hours instead of constantly.

There were several other energy assessment recommendations, such as a installing a control for the fans in the egg cooler (which currently run constantly) but these have not been implemented as they weren’t deemed worthwhile by farm management.

Towards the future

As for which energy efficiency technologies will likely be used in the future on Canadian poultry farms, Kanani and Li note that factors like technology evolution, policy/regulatory incentives, identification of context-appropriate systems and strategies based on ‘life cycle thinking’ will all be important. They believe however, that technology choice is ultimately a business decision, one that “will likely be strongly influenced by ROI considerations.”

UPDATE ON HEAT EXCHANGERS

With new designs now available, it may be time to consider installing a heat exchanger.

By Treena Hein

It’s been many years since heat exchangers arrived on the poultry industry scene.

As with countless technologies, designs of new models are greatly improved over those of the past. Heat exchangers have become much easier to both clean and install, and in terms of efficiency, some manufacturers claim that current systems cut barn heating bills in half. The higher indoor

temperatures of broiler operations make them more worthwhile than egg producers.

Indeed, although most farmers today look at heat exchangers as a way to help reduce heating bills, that’s just one of the benefits they provide, says Mark Relouw, president at Exacon, which distributes AviAir exchangers in Ontario and also the Recov-Aire.

“Another advantage…is the

decreased time that incoming air has to warm up enough to start collecting moisture in the building, and the faster it can collect the ‘bad’ air to be exhausted out,” he says. “This very much helps with air quality and humidity control over regular exhaust ventilation.”

Mathieu Brodeur, president at Avi-Air, a heat exchanger manufacturer in Quebec, agrees that exchangers provide much more than savings on heating costs. “They are a great tool,” he says, “to improve your litter condition, bird health and welfare, and to reduce your farm’s environmental footprint.”

In years past, the high humidity and dust in poultry barns presented challenges for heat exchangers, requiring them to undergo a detailed cleaning during flock production. Now, most or all cleaning is between flocks and it’s much easier. For example, Brodeur notes that the core of the smaller units being manufactured in Canada today, in comparison to larger units that are mostly imported from Europe, are easily removed, allowing the cleaning process to be more efficient.

Some systems require more than one unit in the barn.

The higher indoor temperatures of broiler operations make heat exchangers more worthwhile for those facilities than egg farms. Pictured is the Eco ACU heat exchanger from Vencomatic.

Brodeur explains that having one larger unit with only one inlet requires recirculation ventilators to redistribute fresh air throughout the space, but smaller exchanger units are able to distribute the air around them (in the case of Avi-Air, about 80 feet). Older heat exchanger models also struggled with freezing in the winter months, notes Randy Taylor, sales director at manufacturer ESA, but these problems have been addressed.

Here is a roundup of attributes of some brands now available, with producer input where possible.

ESA

The ESA-SERIES exchangers use existing barn heat to defrost the inside of the unit as needed. They only require a 10-minute cleaning between flocks (remove the core, power wash and re-insert). The ESA-1000 also has a “very unique” patented ventilation system, Taylor says, with a single motor that pushes air in both directions and requires only single-phase power and 2.6 amps per unit.

“All other brands of heat exchangers use two motors and require twice the amount of electricity to operate them,” he says. “Another unique feature is our small footprint. We don’t require a slab of concrete and no ducting. You simply add more units depending on the quantity of chickens raised per flock. Our typical rule of thumb is one heat exchanger per 4,000 chicks.”

Broiler farmer Adam Schlegel installed an ESA exchanger last year in one of his barns at Schegelhome Farms near New Hamburg, Ont. He says he’s very pleased with the system and the barn environment it creates. He notes that it pre-warms incoming winter air by 15 to 20°C. “It’s a simple unit and it’s easy to clean,” Schlegel explains. “This design is also easy to put into a barn build. It’s a single opening and everything is mounted inside the barn. A lot of other systems have two fans, which obviously uses more power and requires more framing and so on to install.”

Schlegel runs his system year-round. “Even in the summer, the barn temperature has to be really high for chicks and you want to recover as much heat as possible at night, for example,” he says. “For the first two to three weeks of the cycle, it’s the only ventilation I have going.”

Avi-Air

Last fall, Keet Farm in Georgeville, Que., installed 23 heat exchangers across its broiler barns. After looking

at various brands over the last few years, owner Jose Keet says he decided on Avi-Air as it had all the characteristics he was looking for: low maintenance, auto-flush and auto-defrost. “With the results we had this past winter, we figure they should pay for itself within four to five years depending on the barn efficiency,” he notes. “I have never seen such a dry litter in the winter since the installation of those machines.”

The core is washed between flocks, but dust is also flushed from the core of the Avi-Air every day through several automatic washing cycles. This rinsing system allows the cartridge to perform at full potential during broiler growing time, Brodeur says, and also make it a whole lot easier and much less time-consuming to clean compared to other systems.

Freezing of the condensate water in the core under cold temperatures is prevented by automated de-icing cycles. Brodeur adds that Avi-Air’s exchangers are compatible with the most popular Canadian modern controllers so that they are fully integrated with the barn’s ventilation and heating system.

“They are a great tool to improve your litter condition, bird health and welfare.”

“It becomes a much more cost-efficient investment since no standalone computer is needed to drive the Avi-Air in new barns,” he says. “However, a standalone is available for those barns equipped with older technologies.” Relouw adds that during the warm seasons, the intake fan can be used as an exhaust fan to almost double the exhaust ventilation.

Avi-Air has conducted its own studies on brooder heating time in two identical broiler barns next to each other, one with two Avi-Air heat exchangers and the

Avi-Air’s heat exchangers are low maintenance, auto-flush and auto-defrost.

other with conventional minimum ventilation.

“Over many flocks, from 2016 to 2018, we observed a yearly average of 45 per cent reduction in heating time in the barn with the heat exchangers,” Brodeur says. “Obviously, it was more significant from fall to spring than in summer; however, we observe some savings even in July for the first 10 days of production.”

This spring, Avi-Air is working with an independent organization called the Natural Gas Technology Centre to gather and analyze data on gas savings.

Recov-Aire

As mentioned earlier, Exacon also distributes the Recov-Aire heat exchanger, which has a smaller intake fan to help with heat recovery. Number of units depends on size of barn but its usually no more than two. “Installation is relatively easy depending how the customer wants incoming air brought in,” Relouw adds. “When the core is clean, it is very achievable to get 50 per cent efficiency and the units are very simple to operate. In very cold weather, frosting through the intakes can occur. In most cases, this can be managed depending how the exhaust and intake fans are assigned through the ventilation control.”

Eco ACU (AgroSupply)

In the winter, this unit achieves a thermal efficiency of up to 80 per cent, says Tom Randall, Eastern Canada sales representative at distributor Vencomatic. In warm conditions, recaptured condensation applied to the tubes causes considerable evaporative cooling of the incoming air – more than 13°C – without an increase in absolute humidity.

For cleaning, all side panels of the Eco ACU can be easily removed, making its core accessible from all sides, and the unit is now equipped with a fully automatic cleaning system. “Recycling of condensed water is used to clean the Eco ACU,” Randall explains. “The water from this cleaning system can be reused by filtering out particulates. This automatic cleaning system can now be used while the Eco ACU is in operation.”

Advice for potential purchase

Brodeur’s best advice for farmers thinking of purchasing heat exchangers is to investigate ROI timelines. “Therefore, CFM (ft3/minute) output per dollar and heat core efficiency are critical,” he says. “In fact, look for how many days in a broiler cycle you can rely only on the heat exchangers to assure your winter ventilation (0°C and below).

“It’s important to know that as soon as other conventional ventilators kick in to support additional ventilation the benefits of the heat exchanger will be diluted. If the system setup is too small or the ventilator maximum output is too weak, then conventional ventilators might kick in by 10 or 14 days of growth. You should aim for 21 days relying only on the heat exchangers to get significant improvements.”

Brodeur reminds broiler producers to remember that barn humidity starts to accumulate by one to three weeks of age. “You need 100 per cent of your exhaust air to go through the heat exchangers during that time,” he says, “to remove as much as humidity as possible.”

EFFICIENCY INNOVATOR

Award-winning expert Bill Revington shares his energy saving tips and tricks.

By Treena Hein

If you’ve been paying attention to energy efficiency developments in Canada’s poultry industry, you’ll know the name Bill Revington. Indeed, he’s had a long career as an energy efficiency innovator. As he was preparing for his April retirement from his role as general manager of farm operations at New Life Mills in Hanover, Ont., he sat down with Canadian Poultry to reflect on his achievements, share his best tips and predictions for the future.

“One thing I’ve learned about energy efficiency over my career is that little things can make a big difference,” he says. “In the past, electricity was relatively cheap, and it was the initial investment in energy-saving improvements that was expensive. Fluorescent lighting was more expensive than incandescent, for example. But now, electricity is the third or fourth largest expense item in poultry production after feed and bird cost, and I think the price is going to continue to rise. The good news is, compared to other expenses like feed, birds and wages/benefits, it offers the greatest number of trimming opportunities.”

Revington advises producers to

start monitoring operational electricity use and asking questions, if they haven’t already. “Collect data about your operations and study it,” he says. “You can use small measurement devices that show you what a motor uses, for example. Older fan motors can be terribly inefficient. Every time I’ve measured things, it’s been very instructive. If nothing else, it helps you

understand how much of your bill is going towards certain things.” Big users of electricity, like submersible pumps, could be running continuously due to leaks or faulty check-valves, but Revington says you would never know without monitoring (through having a time accumulator installed by an electrician, for example). Timers on big motors, like those on manure-

Bill Revington, who recently retired from New Life Mills, had a long career as an energy efficiency innovator in Canada’s poultry industry.

drying blowers, can also be added to minimize peak electricity use (if your province has such a fee system).

Besides monitoring, Revington points to a lot of small things producers can do on a regular basis to trim their electricity bills. Cleaning heaters and fans weekly, for example, will ensure top efficiency. Gas heater plenums should also be cleaned regularly to ensure a good burn and minimize fire risk. Another idea is to install timers or motion sensors on lighting in stairwells, sheds and more.

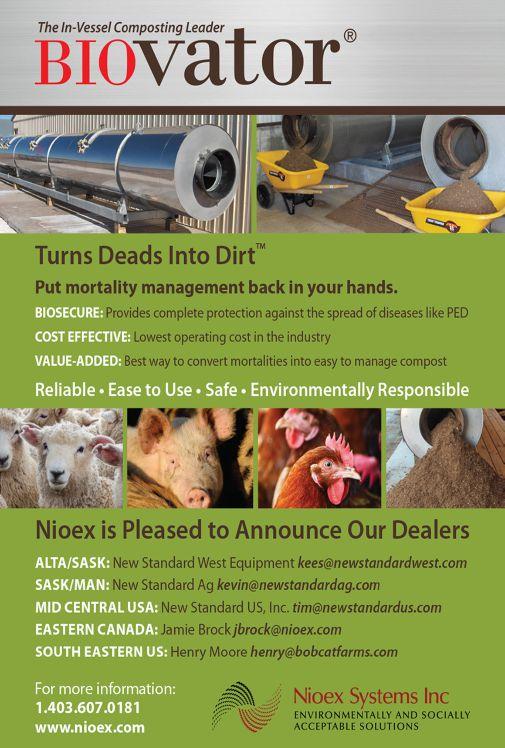

Optimizing LEDs

Revington recognizes that, by now, most producers are reaping the benefits of installing LEDs. However, he isn’t sure if those same producers are getting the usage correct. He says he was shocked at how much LEDs can save, up to 80 per cent, even after he first crunched the numbers some years back. “But you have to make sure you match your bulbs to the dimming equipment employed,” he reports. “A lot of good work has been done on this and with a bit of homework, you can achieve huge savings.”

Indeed, if producers don’t do their homework, the LED lights they choose could end up costing them money. “We know that hours of light, intensity of light and the nature [or colour] of the light is critical to good performance in pullets and layers,” Revington says. “Many of the newer LED bulbs produce wavelengths that birds can see but humans cannot, and can make the light appear much brighter to birds, to the point of discomfort. This can cause production problems that are easy to miss. A light meter that measures wavelength and variables such as flicker [which birds abhor] is a really good investment.”

He adds that most LED bulbs do not dim in a linear fashion, and that some high-efficiency LEDs need to be dimmed to 50 per cent or less in order to reach the intended lux levels. When you replace your incandescent bulbs with LED, he advises that dimmers should be calibrated against a meter to ensure that correct settings are used.

Beyond electricity

Around 2005, Revington got the go-ahead

from New Life Mills to install an automated system in one of the firm’s turkey barns. It dimmed and turned off light fixtures in response to varying levels of natural light entering the barn throughout the day.

“We achieved energy savings of 60 per cent,” Revington says, “so it was really a big success. We worked with a local engineering firm. It was pretty exciting to win the award for it in 2007 (a Premier’s Award for Agri-Food Innovation Excellence). It really was quite thrilling to have recognition for our hard work and success with what was really cutting-edge technology at that time.”

The system was used in the only New Life Mills barn at that time that had curtain-walled sides. Because that property has since been sold, Revington is not sure if the system in still in use.

Revington also spearheaded the use of infrared tube heaters and they are now found in most New Life Mills barns. These systems radiate infrared heat down to bird level, and provide natural gas savings of 10 to 30 per cent compared to other heating systems. “One thing that was an issue was we were venting the exhaust from the heater motors into the barn,” remembers Revington, “and we had to work

with outside firms to make sure the CO2 and moisture was being handled properly.”

A few years ago, New Life Mills also changed its handling of deadstock, a move that improved energy efficiency at the same time it reduced biosecurity risks. At that point, deadstock was being picked up and taken away. While the company considered on-site incineration, it deemed it too costly upfront and also in terms of ongoing operation. Instead, New Life Mills chose the BIOvator, an enclosed made-inCanada composting system.

“We have three BIOvators now and it’s been terrific,” Revington says. “It gave us on-site control of the deadstock material and while the motor inside these units does use power to move material along and turn it, it’s allowed us to cut our freezer use significantly. We had two, three or four large chest freezers at most sites, running yearround, and we’ve been able to cut that back to one or two.”

Going forward, Revington thinks solar technology, now that it’s more advanced, will be something that Canada’s poultry industry will take advantage of. “Most barns have a lot of rooftop space and as the technology comes down in price and be -

comes more efficient, I think there will be significant opportunities for producers to benefit,” he says.

“Energy storage technologies are also improving. There are some really interesting things going on today that make me think that it may soon be possible for poultry operations to go ‘off grid,’ – if not entirely, then certainly in a significant way. Some folks are already doing this. Energy could become just one more farm commodity.”

Revington has been at New Life Mills for 29 years, and although it wasn’t always as an energy innovator, he has certainly made his mark in that position. He had actually started at the company as a nutritionist, then became head of that department, and then was offered the position of farm operations manager, which he has held ever since.

“It’s been my job to produce the product as economically as possible within the supply-managed system, to look for opportunities where we could make things more efficient,” he says. “New Life Mills has been terrific at embracing new ideas and putting investment into new technologies, and I’m pleased to say it has always paid off. It’s been a great company to be with, and I’ve had a lot of fun.”

Some high-efficiency LEDs need to be dimmed to 50 per cent or less in order to reach the intended lux levels, Revington says.

Going forward, Revington thinks solar technology, now that it’s more advanced, will be something that Canada’s poultry industry will take advantage of.

QUICK TIP

continued from page 22

that affects 360,000 adults and children across Ontario every month.

Feed Ontario has a goal of providing 60 per cent fresh food and they have a great need for protein; this goal is changing the way they operate and CFO is working closely with them, Shanahan explains. “They have this goal, we have the means. It makes it easy for us to give back.”

The Chicken Farmers of Nova Scotia (CFNS) also provide $25,000 per year to food banks through the Feed Nova Scotia program. Other initiatives over the past several years have included their involvement in Farm Credit Canada’s Drive Away Hunger program, donating chicken to community services such as the Lion’s Club, providing recipes and educational materials and individual donations to groups such as the Valley Community Learning Adult Literacy Mile initiative. Such involvement is done on a case-by-case basis, explains Melissa Taylor, CFNS program manager.

Is the social progress sustainable?

Going forward, Bishop-Spencer says that CFC will continue its partnership with the Ottawa Food Bank, just as provincial boards will likely continue to contribute to their local foodbanks.

“Thinking more broadly about the social sustainability aspects of animal health, continued implementation of our Raised by a Canadian Farmer Animal

Care Program remains important, as does the Antimicrobial Use (AMU) strategy, which continues to evolve as CFC continues surveillance and considers further reduction steps,” states Bishop-Spencer.

And, as the LCA report further explains, “Balancing consumers’ expectations, operational efficiency and optimal bird conditions remains a common challenge for the industry.

“There is an opportunity to strengthen the collaboration among all industry members and throughout every step in the supply chain to continue to improve performance with regard to animal health and care.”

This is not only important for the health of the birds but also for the health of the consumer.

For workers, the LCA reports room for improvement. For example, 40 per cent of respondents have not followed any occupational health and safety training in the past three years.

What’s more, 70 per cent of farmers do not formalize contracts with their employees in a written document.

Improvement in these areas could positively affect worker retention and satisfaction.

Looking ahead, the CFC will be spending 2019 examining the LCA data and exploring possible next steps for the chicken industry in terms of environmental initiatives and sustainability work in general.

CFO program enables farmers to give back to their community

Since January 2015, the CFO Cares: Farmers to Food Banks program has offered farmers the opportunity to give back to their local community through the donation of up to 700 kg of chicken per year, the equivalent of 300 birds.

Pat Shanahan manages the program for CFO. As she explains, through agreements with the processors a farmer can specify if they would like the donation to go to their local food bank or to be distributed through the Feed Ontario network, targeting the area with the greatest need at that time.

Feed Ontario has set a new target of 60 per cent fresh food with a large need for protein. “They have this goal, we have the means,” Shanahan says. “It makes it easy for us to give back.”

So far, 400 farmers have signed up for the program, details of which can be found at ontariochicken.ca. All farmers are eligible; donations are facilitated by the CFO.

“Our goal for this year is to get processors more engaged,” says Shanahan, who continues to work with the 18 primary processors and secondary provincial processors, looking for synergy to grow the program.

•

•

•

•

•

• Property also available

Selling price: $2.6m. Serious inquires only please.

For more info, reply to: biz-opportunity@hotmail.com

Bredenhof Farms

The business

In mid-January, Sean and Bonnie Bredenhof were about to place their first flock of organic laying hens after receiving a 3,000-bird quota in the B.C. Egg Marketing Board new entrant lottery about two years earlier.

The barn

SECTOR

After getting the “free” quota, the Bredenhofs acquired land and built a new pullet barn and layer barn with a Farmer Automatic Loggia aviary, the first such system in B.C. Although the two-tier housing system has a spacious walkway between its two rows, birds are not segregated and are free to travel between tiers and rows and access outdoor grazing areas through trap doors located on one side of the barn. However, they do not have to move as feed, water and nesting is available on each tier.

The strategy

Even with free quota, Sean says 3,000 birds is not enough for a viable operation, so he built the barn to house 7,000 birds. He then augmented the new entrant quota with 2,500 leased birds to bring the initial flock to 5,500 birds. Sean notes that leasing was the only way to increase their initial flock size. “New entrants don’t get a producer licence until they start shipping eggs,” he says. “We can’t acquire any quota until we’re actual producers or we would lose our new entrant quota.”

LOCATION

Chilliwack, B.C.

Layers, egg production

TOP: A close up of the aviary system. Note the trap doors providing outdoor access and the stairway to the upper tier.

ABOVE: Sean and Bonnie Bredenhof with their daughter, Brynn, outside the barn.

Tamara Carter Co-founder

Carter Cattle Company Ltd. Lacadena, SK