www.contenderbypierce.com

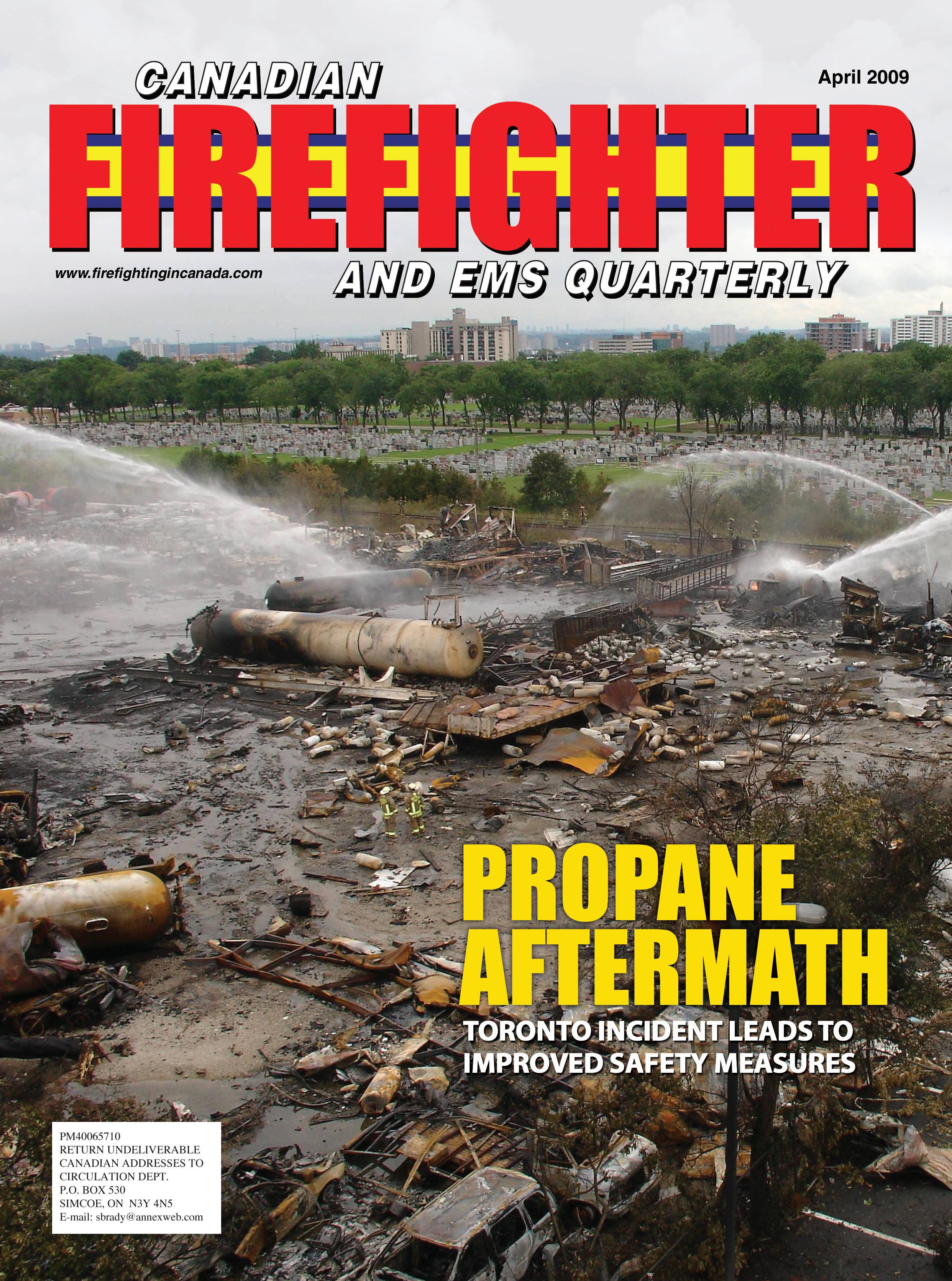

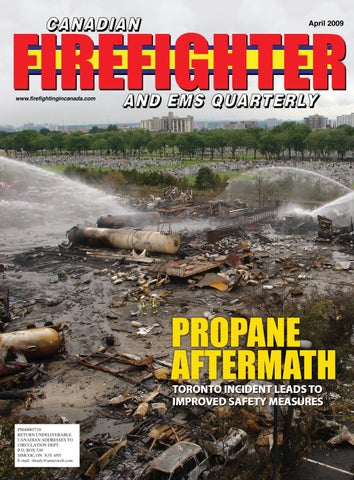

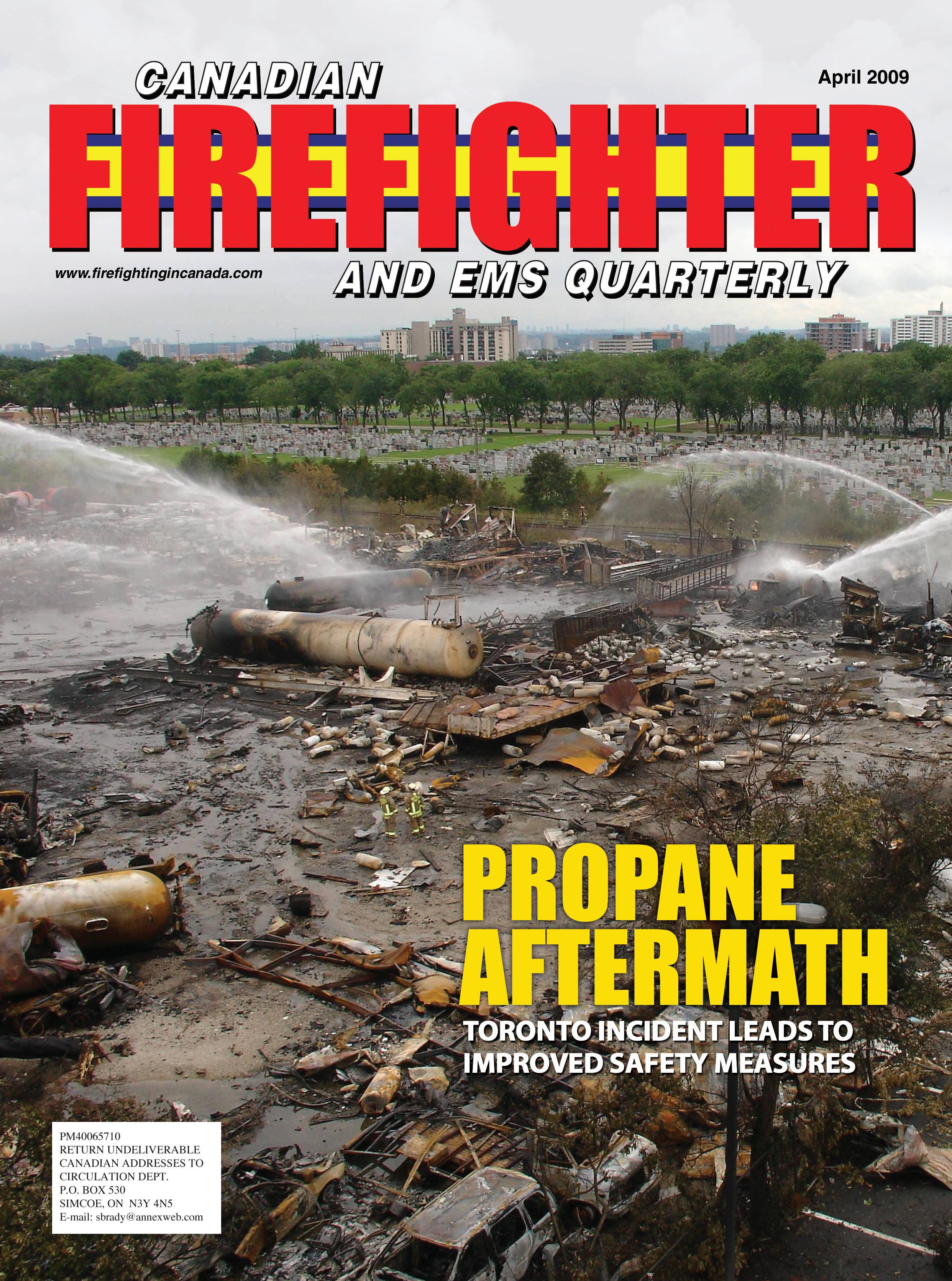

Unmanned master streams were used at the site of the Aug. 10, 2008, explosion and fire at Sunrise Propane in Toronto. Investigators remained on scene for 35 days but at press time had not found the cause.

www.contenderbypierce.com

Unmanned master streams were used at the site of the Aug. 10, 2008, explosion and fire at Sunrise Propane in Toronto. Investigators remained on scene for 35 days but at press time had not found the cause.

fter we went to press with this issue of Canadian Firefighter and EMS Quarterly, a lawyer with Stevensons LLP in Toronto, which specializes in litigation, was to ask a judge to allow a $300-million class-action lawsuit to proceed against Sunrise Propane and landowner Teskey Concrete Co. Ltd.

Months after the Aug. 10 explosion and fire, people who live near the Sunrise site still aren’t back in their homes, still don’t know who’s paying for the damage and still don’t understand how Sunrise managed to have so many propane tanks and other materials on its site, in apparent contravention of its licence.

There’s a simple answer. One watchdog monitors such things – the Technical Standards and Safety Authority (TSSA). It’s a provincial non-profit regulatory agency responsible for regulating fuels, amusement devices, elevators, boiler and pressure vessels and ski lifts, among other things.

With more than 5,800 licensed propane storage facilities in Ontario, the TSSA’s mandate is overwhelming. Indeed, the agency was chastised after the Sunrise blast when it couldn’t accurately state the number of propane depots in the province. And, as the NDP pointed out, Premier Dalton McGuinty criticized the creation of the TSSA when he was in opposition.

The Toronto Sun noted that the TSSA faces almost two dozen lawsuits over elevators and escalator accidents in Toronto alone. It also noted that in the wake of the Sunrise explosion, the TSSA was criticized for its lax propane inspection guidelines. To its credit, TSSA has posted on its website the 40 recommendations of a panel that reviewed the Sunrise incident and its responses to the recommendations.

The quick action of the Ontario government in commissioning the panel is commendable. But the fact remains that the Sunrise site was licenced for two propane storage tanks but was littered with hundreds of propane cylinders. In addition, tanker trucks were parked at the site, which lies in the middle of a residential neighbourhood. (See story on page 8.) After the blast, opposition politicians said regulation of the fuels sector should be returned to government.

In its extensive report, the review panel recommended:

• that licence approvals for propane facilities must make it clear that operators reassess the land development around them, and that municipalities need to notify propane facility operators about development plans close to a depot’s defined hazard distance;

• that the province ask the Canadian Standards Association to update the propane installation code, with a focus on setback distances, emergency response plans and special fire protection;

• that propane operators be required to carry insurance as a condition of licensing;

• that annual inspections of propane facilities are needed until the TSSA has enough data to develop a more rigorous, statistical approach to safety, under which higher-risk facilities would get more in-depth attention.

• and that there be better storage data on what’s at each site, including so-called transient storage in cylinders, tanks, tanker trucks and rail cars and improved safety training for propane workers.

The Sunrise blast caused millions in damages to nearby homes and put thousands of area residents at risk. Among those at most risk were the firefighters who responded to the call, not knowing what was on the site or what might happen next. The expectation by residents and politicians is that first responders will deal with whatever’s thrown at them – and they do. Having regulations in place that at least ensure a modicum of safety for first responders is the responsibility of the government lawmakers. It’s time they stepped up.

April 2009 Vol. 12, No. 2

Editor Laura King lking@annexweb.com 289-259-8077

Advertising Manager Hope Williamson hwilliamson@annexweb.com 888-599-2228 ext. 253

Sales Assistant Barb Comer bcomer@annexweb.com 519-429-5176 888-599-2228 ext 235

Production Artist Kelli Kramer

Group Publisher Martin McAnulty fire@annexweb.com

President Mike Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com

Mailing Address

PO Box 530, 105 Donly Dr. S., Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPT., P.O. BOX 530, SIMCOE ON N3Y 4N5 E-mail: sbrady@annexweb.com

Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. USPS 021028, ISSN 1488-0865. Published four times per year (Jan, Apr, Jul, Oct) by Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. US Office of publication c/of DDM Direct.com, 1175 William St., Buffalo, NY 14206-1805. US Postmaster send address change to P.O. Box 611 Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Printed in Canada ISSN 1488 0865

Circulation E-mail: sbrady@annexweb.com Ph: 866-790-6070 ext. 206 Fax: 877-624-1940

Mail: P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

Subscription Rates

Canada – 1 Year $ 12.72 (includes GST – #867172652RT0001) USA – 1 Year $ 40.00

From time to time, we at Canadian Firefighter and EMS Quarterly make our subscription list available to reputable companies and organizations whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you do not want your name to be made available, contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above. No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2009 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication. www.firefightingincanada.com

by Laura King

It’s ironic that Frank Lamie, Toronto’s deputy chief for fire prevention and public education, was among the first on the scene of the massive Sunrise Propane explosion in the early hours of Sunday, Aug. 10. Lamie, who lives in Thornhill, about 10 kilometres from the Sunrise Propane site in north Toronto, had been woken up just before 4 a.m. by the vibrations from the explosions, he believes.

Months after the blast, Lamie carefully chooses the words that accompany his PowerPoint presentation on the incident, aware of a pending class-action lawsuit but still leaving members of the Canadian Fire Safety Association shaking their heads over the sheer devastation.

Lamie, whose day-to-day focus is fire prevention and public education, was flabbergasted by what he found at the Sunrise site at 54 Murray Rd. in the former city of North York. The property was licensed for just two propane storage tanks but was littered with thousands of 33-pound propane cylinders and hundreds of 100-pound tanks most often used for heat at construction sites. No one knew whether the cylinders were empty or full of propane. There

were tanker trucks on site and it wasn’t clear what they contained, if anything. The company owner couldn’t immediately be located and there was no available paperwork on site to indicate what was in the various tanks.

Explosions were happening every five to 15 seconds. Debris rained down 325 metres away. Soffits and fascia were blown off of nearby homes. Sheets of drywall dropped from ceilings. The steel front door of one house was blown off, flipped 90 degrees and lodged in the hallway. A piece of a tanker truck ended up in a bus shelter a kilometre away; the end of another tanker blew off and lodged in a City of Toronto road-salt storage dome 350 metres away and a third piece of a tanker was embedded in an office building 250 metres away. The timing of the blast, early on a summer Sunday morning, likely spared dozens of lives, Laimie says.

Headstones at a nearby cemetery were damaged by shrapnel. Asbestos from pipe wrapping blew over a large area to the east of the site, affecting 580 homes and causing panic among residents.

Buildings in a 1.8-kilometre radius were evacuated; more than 10,000 people were forced to leave their homes, many taken by TTC bus to temporary shelter at York University.

Highway 401 was closed and CN and GO trains were shut down for fear of propane cylinders rocketing down the rail line. Planes at nearby Pearson International Airport were grounded out of concern that exploding propane cylinders that were flying hundreds of metres into the air could strike one of them.

Still, while media reports in February –six months after the blast – focused on displaced residents and legal wrangling among politicians and agencies over cleanup bills, Toronto Fire Services is focusing on the good that came from the Sunrise incident and the speed at which regulations surrounding propane handling, transport and storage have changed.

By the time Deputy Chief Lamie made his presentation to the CFSA in mid-January, a provincially ordered review of the incident by professional engineers Michael Birk, an expert in BLEVEs (boiling liquid

Investigators spent 35 days at the northToronto site of the Sunrise Propane explosion and fire in which an employee was killed and a Toronto firefighter died. Cause of the incident has not been determined.

panel’s recommendations, indicates which ones fall under TSSA authority and describes status/actions and timing of changes.

expanding vapour explosions) and Suzanne Katz, a former director and chief inspector for gas safety for the B.C. government, had resulted in the implementation of 30 recommendations with 10 more under review.

According to the report, more than 300,000 Ontario businesses and households consume about 650 million kilograms of propane every year in barbeques and vehicles and to provide heat for construction sites, farms and rural homes. More than 5,000 people are employed in the propane industry and about 5,800 storage facilities are licensed for propane storage in Ontario. The Technical Standards and Safety Authority oversees propane safety in Ontario and was the target of many of the recommendations in the report.

A fact sheet on the recommendations is online at http://www.sbe.gov.on.ca/ontcan/sbe/ en/news_propane_factsheet.jsp. The status of the recommendations is updated regularly.

The TSSA’s action plan on propane handling, storage and transport is available at http://www.tssa.org/home/default.asp?loc1 =home. The plan lists all 40 of the review

The review was ordered by the Ontario government on Aug. 28, 18 days after the blast, and was completed Nov. 7, by which time some new measures were already in place. In August, Ontario’s Minister of Small Business and Consumer Services asked the TSSA to audit propane facilities. Phase 1 involved a re-audit of all large propane facilities with permanent storage capacity by Aug. 31. Phase 2, involving smaller storage facilities, was completed by Dec. 31.

Amendments were made in the fall to the Propane Storage and Handling Regulation and Fuel Industry Certificates Regulation, both under the Technical Standards and Safety Act, 2000. They include:

• Inspections: Propane facilities will be inspected annually or more frequently.

• Licensing: Propane facilities will be required to create, implement and update risk and safety management plans and seek fire service approval of applications for new and expanded facilities. Municipalities will also be able to provide input on new and modified facilities where they may impact land-use planning.

• Operations: Propane operators must declare and abide by limits relating to the

total amount of storage and inventory of propane and keep records to demonstrate maintenance of fire safety equipment and systems.

• Qualifications: Propane safety trainers will be required to have both practical and theoretical knowledge of propane. Propane facility employees, as well as at least one partner, director or officer of every company operating a propane facility, will be required to carry and produce proof of their credentials, upon request, and their training will be reviewed at least every three years.

• Public interaction: Emergency preparedness sections of the risk and safety management plans for propane facilities will be made available to the public.

A discussion paper that preceded the review is available at http://propanesafetyreview.ca/Discussion_Paper-A_Review_of_ Propane_Safety_in_Ontario.pdf. It focuses on “propane-related legislation and regulations compared with internationally recognized best practices.”

The full report by the engineers is available at http://www.propanesafetyreview.ca/. Meanwhile, the TSSA is also the target of some public criticism and frustration. Toronto city councillor Maria Augimeri, in whose ward the explosion occurred, told

the Toronto Star in February that the “TSSA clearly wasn’t doing its job.”

And, because the TSSA can’t be sued for negligence, Toronto law firm Stevensons LLP, which represents thousands of residents affected by the blast was to ask a judge in March to allow a $300-million class-action lawsuit to proceed against Sunrise Propane and landowner Teskey Concrete Co. Ltd.

Bizarrely, Sunrise Propane’s website was still functioning at press time, promoting its 24-hour dispatch for customers. Sunrise’s licence was revoked shortly after the explosion and the site remains a shambles in a neighbourhood where homes are still boarded up and street lights were finally turned back on in February.

As Deputy Chief Lamie noted, fire officials and those from other agencies spent 35 days at the Sunrise Propane site trying to piece together the cause of the tragedy (the cause hadn’t been determined at press time) that killed an employee and during which

a fatal heart attack felled Toronto District Chief Bob Leek. By 4:05 a.m. the incident had been upgraded to a fifth alarm and a sixth alarm was called about an hour later.

Firefighters were dealing with BLEVEs, with unknown substances, with intense heat and flying debris, and fought the inferno with unmanned master streams pumping 500 gallons per minute.

Lamie’s frustration over regulatory violations at the Sunrise site, the danger to firefighters and nearby residents, and the lack of accountability in the aftermath was evident as he spoke to Canadian Fire Safety Association members. Lamie’s presentation about the incident is in demand – he’s making the rounds of fire chiefs association conferences starting this spring. The photos alone, detailing the magnitude of the devastation, are worth the price of admission.

Daryl Fuglerud, Toronto Fire’s deputy chief of staff services, administration and communications, also spoke to the CFSA

Top: Debris from the Sunrise Propane explosion landed hundreds of metres away, damaging homes and properties. Left: Forty recommendations about the transportation, storage and handling of propane from a report on the Sunrise Propane fire and explosion have been implemented or are under review.

about his experience at the Emergency Operations Centre during the Sunrise incident. He said lessons learned from the 2003 Ontario blackout helped city, fire and emergency officials better cope with the magnitude of the propane explosion and noted that since amalgamation of East York, Etobicoke, North York, Scarborough and York into Toronto in 1998, emergency responders have had to deal with larger incidents that require the co-operation of more agencies and more people.

“It’s simple things like how work stations need to be set up,” he said. “The most important thing is how we interact with each other.”

Fuglerud said Incidents like the SARS outbreak of 2003 and the blackout have forced agencies to work together and work better together. For example, fire. EMS and police officials now meet once a month to discuss issues and incidents. The personal relationships that grow from those meetings have led to improved relations during emergencies, he said.

Meeting the universal goal of boosting size and strength

Most women on this planet would argue that men are fairly simple creatures. The more I learn about myself, and men and women in general, the more I unfortunately tend to agree. As hard as it is for me to admit this, nowhere is this more prevalent that in a gym. While women often strive for a variety of goals from flexibility to toning and weight loss or overall well-being, most men have a very specific mindset. As men in the gym we seem to have two broad goals – we’re either trying to lose weight or gain size and strength. Increasing size and strength is the overwhelming favourite with men, and it also seems to hold a lot of confusion. Many men struggle with this battle their whole lives and, unfortunately, are never satisfied with their progress. Here, we’ll explore the fundamentals and techniques of achieving this common goal of increasing size and strength that so many of us share.

Think back to the first time you set foot in a gym. It’s OK to admit that we were all quite overwhelmed. As you remember walking onto the floor, think of what came into your vision. Scattered around are hundreds of machines for just about anything you may want to do. If your experience was anything like mine, you could identify only a handful of these machines and you could operate even fewer. From there, most of us inched our way toward the dumbbell (for curls) and the flat bench for the obvious. Finish with a few sets of abs and your first workout was probably complete. The point I’m trying to make is that from that point the majority of us were self taught, or taught by a friend who initially dragged us in there. Most of us lack much in the way of formal training and, chances are, so did our friends and mentors who got us started. If this was familiar territory, read on and we’ll get to the basics of building mass.

When training for size and strength you simply combine the two categories of exercises. If you’re confused about which movements to select, stick to the basics first. There are four essential exercises you need to be doing to reach your goals – the big four are squats, deadlifts, pull-ups and chest presses. These are all compound movements dealing with very high exertion over several muscles. These lifts will also release the highest levels of your essential growth hormones. The better you are at these four movements the better your fitness level will become. Your isolation exercises will fall into place but your mass program is on the back burner until you have mastered the big four.

BrAd LAwreNce

‘The key to purpose training is becoming motivated enough that you’re excited about lifting.’

Motivation is one of the biggest speed bumps to overcome, not just in a gym, but in life. We all have good days and bad days in the gym. The key to purpose training is becoming motivated enough that you’re excited about lifting. If you’re training for mass you should get in there and feel like you want to leave blood on the barbells. To succeed, you need far more good days than bad. Ask yourself, on a scale of one to 10, how hard am I working? Your answer should be 10 or your reason for stagnant progress is obvious.

All exercises are not created equal. Different exercises exist because they offer different results. When choosing exercises for size and strength you’re looking for two things: first, for size, choose exercises that allow you to lift near maximum weight and offer a reasonable amount of isolation to the muscle you’re attacking; second, for strength, you should choose exercises that require a great deal of skill and still allow you to lift very heavy loads.

No matter how hard you train, your muscles simply won’t grow unless you overload them. One or two sets isn’t going to cut it; shoot for six to eight reps of maximum weight, and up to five sets. Each set should end in muscle failure; if you have something left in the tank you’re cheating yourself and holding back vital hormones from your muscles.

There are several important hormones in your body that can help you with no supplementation necessary. The three we are going to focus on are testosterone, growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor. These hormones all release with high-intensity workouts and high-intensity sprints. The reason you need to perform your big-four exercises, and the reason you need to become exhausted through them, is the release of these hormones. Testosterone is responsible for creating muscle mass among other things, and is crucial to your success. Growth hormone is commonly called the fountain of youth, and helps with all bodily functions, especially building muscle and lowering body fat. Growth hormone is released when you’re training and when you’re sleeping. That’s just one more reason to get a good night’s sleep and train like a champion.

Your body is built to adapt to anything you throw at it and weight training programs are no exception. The big-four exercises should be a staple; other things can be swapped in and out. If you plateau try “doubles” lifting: perform one full exercise at the beginning and end of your workout, for example, three sets of pull-ups, and three more at the end. Size and strength is a broad topic and we’ve merely scratched the surface. The goal you are tackling takes time. With proper knowledge and dedication it won’t be a lifetime goal, just one of your many goals.

Brad Lawrence is a firefighter with the Calgary Fire Department and a certified personal trainer. Brad has trained and coached countless firefighters through all aspects of fitness and overall well-being. E-mail bradmlawrence@gmail.com

by James Careless

With training time, proximity to training centres and funding for training cited in our recent Fire Fighting in Canada survey as major concerns, it’s clear that specialized training is not a priority for thousands of volunteer departments.

But not all departments need to be all things to all people.

In volunteer departments, “everybody has jobs and families that restrict how much time they can devote to specialized skills training,” says Randy Vilneff, training officer for the Marmora & Lake Fire Department in Ontario.

“Getting people out for training is the biggest challenge.”

As a result, specialized skills like ice/ water rescue training may be less in demand on the Prairies than in the Maritimes but high-angle and confined-space training for silo rescues is a must in farm regions.

Here’s a look at some specialized techniques, where and why they’re necessary and some budget-conscious training techniques.

Confined-space rescue can apply to natural spaces such as caves or man-made spaces such as silos and mines. For firefighters, the key is to learn how to work safely when access and room to manoeuver are limited and good air may be at a premium.

In southwestern Ontario, “we have two businesses within our jurisdiction that have hoppers; one is a glass recycling plant and the other does wood processing,” says John Uptegrove; captain and training officer with the Puslinch Fire Department. “The problems occur when they try and clean the hoppers. Sometimes people get trapped in the material inside, and we have to send in rescuers to pull them out of tall, very narrow confined spaces.”

Training for confined space rescue requires knowledge in roping, rigging and air quality management. “We train by making sure the right rigging is in place onsite, then sending our people in with ropes to practice working in the space and attaching harnesses to victims to pull them out safely,” says

Uptegrove. “We often have to use SCBA equipment – and train with it – because many of these spaces are not oxygen rich.”

Typically, extrication refers to cutting victims out of damaged cars and trucks –freeing them while supporting the vehicle weight so that it does not further harm them or injure the rescuers.

In the strictest sense, “extrication is the act of removing the vehicle from around the patient,” says Vilneff.

The Marmora & Lake department is mid-way between Ottawa and Toronto on the Trans-Canada Highway and in a tourist area, he says. To do the job, “we use hand tools, heavy hydraulics, lifting air bags and stabilizing equipment.”

For training, the Marmora department takes its members out to the local auto wrecking yard in good weather, letting them take apart a few wrecks so that they can get a feel for the equipment. “I never cease to be amazed at how easily the cutters will slice through a car’s roof pillars,” Vilneff says. The cost is negligible: the volunteers provide the time and the local auto yard provides the wrecks.

Biological, chemical, nuclear – just some of the material risks faced by officers on dangerous goods detail. Not surprisingly, dangerous goods or hazmat training is a sufficiently detailed skill that it is taught at the college level and in courses, rather than being left to the volunteers for an ad hoc weekend session. “We teach the NFPA’s hazmat program at the college,” says Dez Shubert, an instructor at Lakeland College in Vermillion, Alta. “In the classroom, we start by teaching our students chemical and product recognition, then get into subject areas such as evacuation and supervision. Once they have this knowledge, we get them into the hazmat suits and start giving them hands-on experience.”

Heavy urban search and rescue (HUSAR) is a specialty skill brought into focus after 9-11. It requires firefighters to become adept at supporting collapsed buildings – especially

concrete – then creating safe zones in which rescuers can excavate and remove victims. Logistics also plays a key role in HUSAR work, with teams being expected to bring in everything they need to live and work for weeks at a time, if need be. In Canada, the federal government is funding volunteer-based HUSAR teams in Vancouver, Calgary, Manitoba, Toronto and Halifax. Federal funding also helps support department-specific HUSAR training in smaller jurisdictions.

Fax: 604-826-7850

e-mail: mal@stokes-int.com

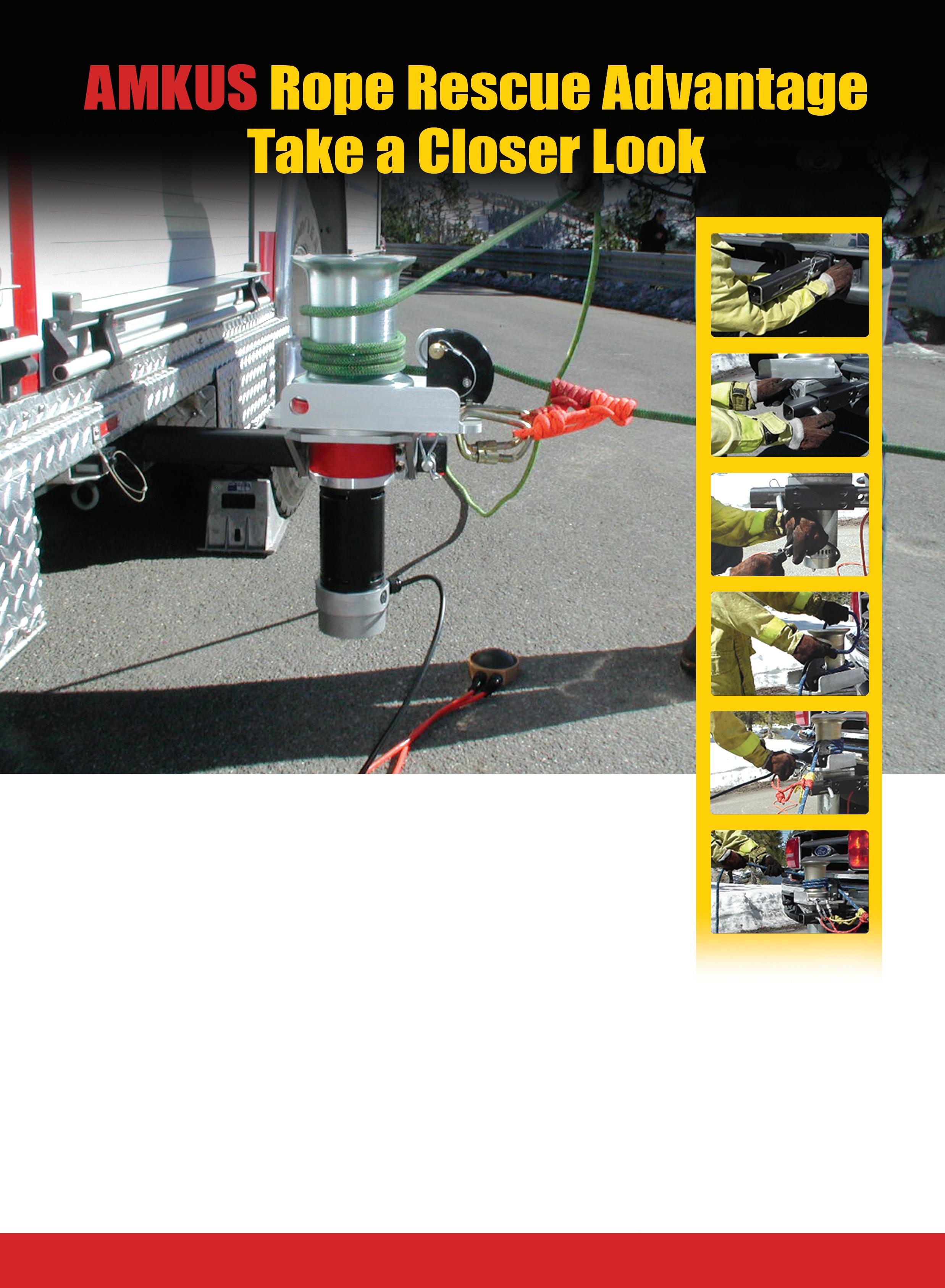

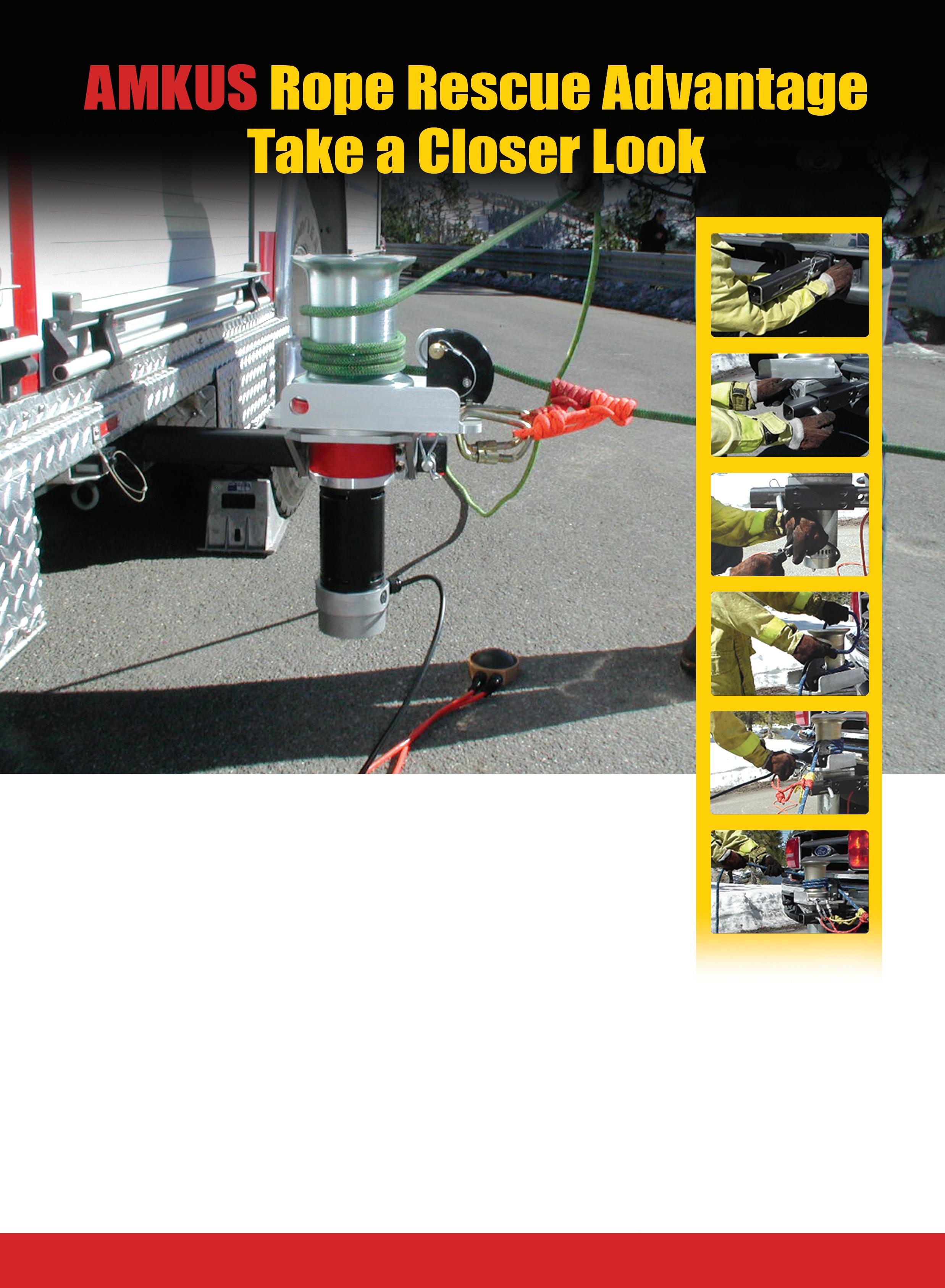

Technical rope rescue can be deployed on cliff-side situations or high-rise buildings. In either case, the art is to use gravity to aid firefighters as they dangle on a rope, trying to use very specialized equipment and techniques to access the victim and have them hoisted to safety.

Lakeland College teaches technical rope rescue as part of its NFPA 1001 1006-accredited firefighter training course. “Since rope skills are vital to effective high angle rescue, we teach all aspects of rope work,” says Shubert. “We start with basic low-slope work, such as rescuing someone whose car has gone off the road on a steep bank. The training progresses until our students learn how to retrieve an injured window washer from the side of a high-rise.”

In Canada, ice and water rescue is a regular part of most departments’ ongoing duties. Yet the task is sufficiently dangerous that careful training is required.

“Ice rescue requires some very specific skills,” says Ted Morrison, chief training officer with Ajax Fire & Emergency Services in Ontario.

“The officers have to learn how to work in dry suits, and how to approach the victim safely while remaining secured to land using ropes. Typically, we run our training by taking officers out onto a local pond when the weather’s gotten cold enough for it to freeze just a bit. We then put a dry-suited victim in the water and let the guys run through the drill.”

“Our area is dotted with water-filled gravel pits,” says Puslinch Fire & Rescue’s John Uptegrove. “People like to go there and party on the weekends, and some drown as a result. In fact, we’ve had two cars drive into water-filled pits. That’s why our people get out on the weekend to work with dry suits and boats, to learn in person what it is like to work in this environment.”

Suppressing industrial fires has to be one of the most thankless tasks

Continued on page 35

In the January issue we talked about air chisels in general, including their basic design, function, proper use and why they are gaining popularity again.

This time we’ll take a look at practical applications and uses for the air chisel.

When I teach extrication courses, students often ask why they would want to use an air chisel when hydraulics are available. My answer: why would they not want to use them? Here are a few examples of when this alternative could be quite handy:

• When performing two extrications on two separate vehicles at the same accident, such as in a head-on collision;

• When dealing with a multiple vehicle accident;

• Equipment failures such as breaking a cutter blade, spreader tip, arm or a hydraulic pump or PTO failure.

Most departments carry just one complement of hydraulic tools on a rescue truck and normally rely on mutual aid for a second set of hydraulics. Let’s assume you would rather not stand around waiting for assistance on your call.

Assuming size-up, safety checks, proper PPE and vehicle stabilization have been adhered to, start with gaining access under the hood for battery disconnection. If the hood-release lever is not accessible or operational, a quick option for the air chisel is to sever the rear corners of the hood completely to allow it to open.

portion of the bit about half way above the material being cut so it will not become buried or stuck.

Once you’re confident that one corner is completely severed, repeat on the opposite side. The hood can now be lifted up and bent toward the front of the vehicle with relative ease. The battery will be exposed and ready for disconnection. (See photos 1 and 2.)

rANdy Schmitz

‘ The Kwik or curved cutter bit is probably the most versatile and convenient for experienced users.’

Choose a location about 12 inches forward of the rear corner to start the cut. This will allow the chisel bit to cut beyond the hood hinges, which are made of thicker steel, and cut only the sheet metal.

Make the cut diagonally until the hood is disconnected.

Most hoods have two layers of sheet metal with a one-inch void in between the layers, so you might have to cut the top layer first and then the second layer to completely cut through the hood.

As mentioned in January, it is imperative to keep the cutting

1. This method can be performed on both front and rear doors. Remove all tempered glass from the door frame, invert a Jackall and insert the foot plate end in the top corner of the door frame as shown in photo 3. Slide the lifting nose on to the top of the doorsill and secure the Jackall in place by wrapping a three-eights rescue chain around the C-pillar and the steel shaft of the Jackall. This will ensure that the Jackall won’t slip off the top of the window frame once it is placed under tension. Operate the Jack handle up and down a few times until there is slight tension on the door. To reduce the workload of the Jackall, chisel cut the window frame where the top of the doorsill intersects, which would be the lower right hand corner. It will take less effort to force the door open once this cut is made. Continue to operate the Jackall until there has been enough force generated to create space between the strike plate of the door’s lock and latch mechanism and the Nader pin.

Insert an 18-inch flat chisel bit and rest the end of the bit on the Nader pin.

Similar to the way a hydraulic spreader is used, a Jackall forces the door out and down, which places stress on the lock and latch mechanism causing it to want to roll off the pin.

In a majority of cases, you can place the chisel bit on the Nader pin and vibrate the pin off the latch plate with minimal effort by simply increasing the air pressure of the air chisel to around 200 psi. (See photo 4.)

If this is not successful after a few short bursts of air, attempts can

be made to sever the Nader pin to release the door. (See photo 5.)

It is a good idea to secure the door with rope from the opposite side of the vehicle to minimize the chances of it flying open.

2. This technique is a good option when manpower is at a minimum. The same concept applies as listed above except our initial access will be attempted from behind the door in the rear quarterpanel area.

Start the cut a distance equal to the length of the air chisel back from the outer edge of the door at, or slightly lower than the door handle.

The idea is to create a void in the car body that will allow the tool to be completely inserted into the quarter panel,

There needs to be enough room to articulate the end of the chisel bit to cut the back of the Nader pin’s reinforced plate where it attaches to the vehicle.

Once a large enough cut-out has been created, manipulate the bit to cut completely around the reinforcement plate that holds the Nader pin locked in position to the door latching mechanism. Once this has been completed the door and Nader pin will no longer be latched to the vehicle. (See photos 6 and 7 and photo 8 on page 22.)

This can also be performed on front doors – the difference is that access to the latching mechanism can be gained by cutting an access hole through the outer door skin to cut around the lock and latch mechanism (see photos 9 and 10 on page 22).

Air chisel kits designed for the fire service usually come with an air impact gun. Unfortunately, this tool is often left in the box. When we talk of tools complementing each other, the chisel and the impact gun go hand in hand (see photo 11 on page 26).

An excellent option for door removal in a side-impact situation is to disassemble the door in the same manner that it was constructed on the production line. Side impact intrusions will often create a space large enough between the fender and the front edge of the door to expose the door hinges.

This allows a great opportunity to take advantage of a crashinduced purchase point. Simply select the proper-sized deep socket included in the chisel kit and remove the bolts that attach the door hinges to the vehicle body. The front portion of the door will drop toward the ground and this will create a space between the Nader pin and the latching mechanism. Try to manipulate the door handle to see if it will release the Nader pin out of the door latch. If that doesn’t work, continue to use the air chisel to cut around the exposed latch to release the door.

Note: Many hours spent disassembling vehicles have shown that an imperial nine-sixteenths inch, half-inch or metric 12 millimetre or 14 millimetre bolt is the most commonly used fastener. This holds true for passenger seat rails and seat backs, door hinges and hood spring assemblies. Just remember this is not all encompassing. There will be times when these sizes will not work, such as with bolts that require star bits. One way to differentiate the common sockets is to put coloured labelling tape around them for quick and easy recognition.

For patients trapped in the rear seating area of a two-door vehicle, a third-door conversion can be a quick and safe option. If a patient is pinned, the short penetrating strokes of a chisel bit allow good control when working to remove metal away from the patient. (See photo 12 on page 26.)

A couple of safety points to consider: Use hard protection between tools and patients; and remove plastic trim to identify unsuspecting

Continued on page 22

Since fires always go out, and since we usually don’t injure or kill firefighters in the process, we often walk away from those fires believing that things generally went well. But did they really? And are we doing everything in our power to ensure a culture that supports firefighter safety and survival?

Fire fighting is a risky profession. Although we all accept these risks, we often use them to excuse behaviours that expose firefighters to dangers that would not be permitted anywhere else.

The following factors, when applied consistently, will help to establish this culture and go a long way to ensuring the safety and survival of our members.

Most standard operating procedures, policies and unwritten rules have existed for generations. Many post-incident analyses identify a breakdown in command, communications, tactics and accountability in contributing to firefighter injuries and deaths. These key elements of incident scene management must be reviewed regularly to ensure that they reflect contemporary standards and regulations in your jurisdiction as well as current technologies and lessons learned from the fire service community.

The best policies and procedures are useless without consistent and continuous training. The fact that a policy or procedure is written down does not ensure compliance at the company level in the field.

Most departments are dealing with shrinking budgets and training is often the first to suffer. Chiefs must demonstrate a willingness to devote the necessary time and expense required to achieve job-wide delivery of programs, and support a strong relationship between training and company officers.

from lightweight structures in the absence of life hazards. It’s always worth repeating that no building (especially a lightweight building that will be torn down anyway) is worth the injury or death of a firefighter.

Two years ago, a friend and colleague survived pre-flashover fire conditions with temperatures approaching 1,100 F, followed by a three-storey fall when he and his crew were forced to bail out of a window. In addition to being the toughest firefighters I know, their lives were saved because they did everything right when they donned their PPE that day. An analysis revealed that their bunker gear, SCBA, flash hoods, gloves and helmets worked as intended to prevent further injuries. Unfortunately, the best equipment in the world will not help if it’s in your pocket (flash hood/gloves), not properly strapped on (SCBA), not buckled up (bunker gear) or not strapped to your chin (helmet).

Peter hUNt

‘The best policies and procedures are useless without consistent and continuous training.’

An important part of any training policy is a comprehensive pre-planning program. Beginning with those that present the greatest risk, buildings should be checked, strategy and tactics developed, information logged and made available to all members. Such a program will help ensure job-wide knowledge of existing risks and consistent fire fighting practices. Remember, the best idea, program, policy or procedure will die a slow death without consistent training, enforcement and leadership.

With policies in place and thorough training to back it up, all that remains is to take it to the street. A systemic problem in today’s fire service is the fact that there aren’t enough fires to ensure adequate experience in all aspects of fire fighting. One of the most contemporary issues is the clash of deeply entrenched fire-fighting tactics (aggressive interior fire fighting) with modern building construction (light-weight components). In the absence of experience, all members must share the responsibility of safely executing tactical policies and procedures, and incident commanders must diligently enforce safe practices.

We are in the midst of a cultural shift that must remove firefighters

Take a look around your department and observe how many of these critical factors are violated. Someone has to be the bad guy and insist that this stuff gets worn!

Another common violation of PPE use is the premature removal of SCBA during post-fire overhaul and salvage. By now, everyone is aware of the presence of hydrogen cyanide in the aftermath of a fire. Although air-quality monitoring is essential, it’s not necessary to remind us to stay on air immediately following extinguishment.

Fire fighting is a great profession but sometimes the camaraderie inhibits the honesty we require to establish a culture that ensures compliance. One of the best methods for providing positive feedback and reinforcement of desired behaviours is the post-incident analysis (PIA). A good PIA, in which lessons are learned and safe practices reinforced without blame or ill feelings, is not easy to accomplish. The PIA should also complement the incident being discussed. The more serious the incident, the more comprehensive the PIA. A written policy ensures consistency and objectivity and that all relevant issues are discussed openly. Don’t ignore the difficult issues; doing so could perpetuate unsafe practices.

There is no greater obligation in the fire service than to ensure the safety and survival of our firefighters. We must constantly work to create and maintain a culture that supports progressive policies, comprehensive training, strong incident scene management, inspired leadership and constant reinforcement of the safest possible fire-ground procedures.

Note: Thanks to Ottawa Fire Services safety officer Steve Brabazon for his assistance with this column.

Peter Hunt, a 29-year veteran of the fire service is a captain in the Ottawa Fire Department’s suppression division. He can be reached at peter.hunt@rogers.com

Continued from page 19

locations of un-deployed roof curtain cylinders. For example, model years 2001 to 2007 of the Mini Cooper three-door hatchback hide the roof curtain cylinders inside the rear quarter panel.

Always use sharps protection on any cut or exposed sheet metal.

The kipper-can technique received its name from extrication challenges during the hand-tool scenarios because they’re similar to opening a sardine can.

With the glass removed, the whole roof skin is cut out to locate the transversal front and rear structural cross members. Once these are exposed it becomes apparent where to make the most efficient cuts to remove them. The advantage here is the size of the egress hole from which the patient can be removed

Continued on page 26

Respect is key to learning to live among colleagues

Our culture is a product of tradition, which breeds an important hierarchy; by honouring established customs, respect is earned. In my short time on the job I have found that it is not solely our abilities as firefighters that bring us together as a crew, it is our respect for the traditions set by those who came before us that truly bring us into the family.

However, not all traditions are apparent, and usually they are not enforced (in an official capacity anyway). We can find a niche in our new life by watching, listening and learning about the way of life in our fire halls. It’s not hard to notice who answers the phone or makes the coffee. I am a strong believer in the family of the fire hall and maintaining the cultural aspect of our profession. We can accomplish this in many ways; one is to pass the torch of probationary life to those coming into our house.

I have had the opportunity to work beside some individuals for whom I have great respect. This admiration stems not necessarily from what they are capable of on scenes or their knowledge base but primarily for taking the time to show me the way. I recall one of our senior members giving me a gem that I won’t forget, a simple adage that I fall back on often; the four ups – listen up, clean up, step up and shut up. If all else fails, the four ups will save you at the fire hall.

the hall or stepping up when the time comes for public service outside work hours. It is by embracing these tasks or others that a new member can successfully earn a place as a brother or sister to those we serve beside.

JeSSe chALLoNer

‘ The first couple of years, particularly the probationary year, on the job can come with many challenges.’

The first couple of years, particularly the probationary year, on the job can come with many challenges. In addition to learning the many facets of fighting fires and treating medical emergencies, new members are adapting to the lifestyle and customs that come with being a firefighter. There are few careers where you do virtually everything together as a crew – train, cook, eat, clean, play, rest, work out, go on calls and socialize. Together as a family, we live and breathe. This depiction of a fire hall can be a tough transition for some, but with guidance, motivation and time, a new member is soon accepted as a trusted friend and important addition to his or her crew.

I am always interested to hear of other fire departments’ traditions – some are similar across the board and some are unique to their respective services. In my fire hall some of the traditions revolve around getting to know the equipment you will be using, such things as diligent truck checks every shift until you can recite the location and use of every tool on the rig. Some traditions focus on the probationary duties, the aforementioned answering of the phone, making coffee, or being the first one at the sink for dishes. Others are products of respecting what members prior have set as a standard. The nice touches in a probie’s repertoire could be making breakfast for the crew or always being the first member on shift that day/night, leading tours that come through

Something else that may require getting used to while learning to live in the fire house is the humor. This can be interesting for new members who are not used to its distinctiveness. We use our humor to help deal with the things we see and do, and to learn lessons for next time. There is value in listening to the anecdote told of the tough job or close call. We also use humor to include new members in life at the fire hall. Of course I am referring to pranks. So much planning and preparation goes into some of these elaborate jokes that half the fun is coming up with the scheme. These pranks are not meant to offend, but to embrace our new members and show them that not everything on this job is serious. In my first few weeks on the floor, I remember one of the brothers on my crew standing over me laughing. I was soaking wet head-to-toe and covered in flour. He said, “If they aren’t talking to you, pranking you or training you, then it’s time to worry.” By this he meant that I was slowly being accepted, they were including me, and acknowledging me as a probie. The new member on the job should know that pranks and jokes are a way of showing fondness. All you can do is laugh. . . and look up when you walk into the bay.

I trust that you, like me, look forward to going to work. We are fortunate to have the best job in the world. We are able to help those in need, work beside our friends and come home to the fire hall and laugh together.

For new members it is paramount to remember that this is more than a job, it’s a family, and part of belonging to a family entails chores, pranks, learning, listening and, above all, respect. Families don’t always get along, sometimes we argue and sometimes we make mistakes but the beauty of family is that we are always there for each other, from senior member to probie we help each other and pick each other up, and, no matter what, we are always there for one another.

Although it can take time to become incorporated into this culture and accepted as a member of the crew, it has been my experience that it is worth every ounce of effort put in.

Jesse Challoner has been with the Strathcona County Emergency Servies in Alberta for 2 ½ years and has been in the emergency services field since 2002. He is an EMT and is completing the two-year paramedic program at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology. Contact him at jchalloner@hotmail.com

and the time saved by not having to make A, B and C pillar cuts. This option can be a good choice if the vehicle is on its side or on its wheels. (See photo 13.)

These are just a few options that can expand your toolbox, so encourage your crew to become familiar with all available tools. Try not to rely too much on hydraulics as you never know when they may fail or not be readily available.

Calgary firefighter and extrication instructor Randy Schmitz has been involved in the extrication field for 16 years and has competed in all levels of extrication competition including world challenges. He is the Alberta chair for Transport Emergency Rescue Committee in Canada, chair of the T.E.R.C. Canada educational committee and a judge for T.E.R.C. Canada and U.S. Contact him at rwschmitz@shaw.ca

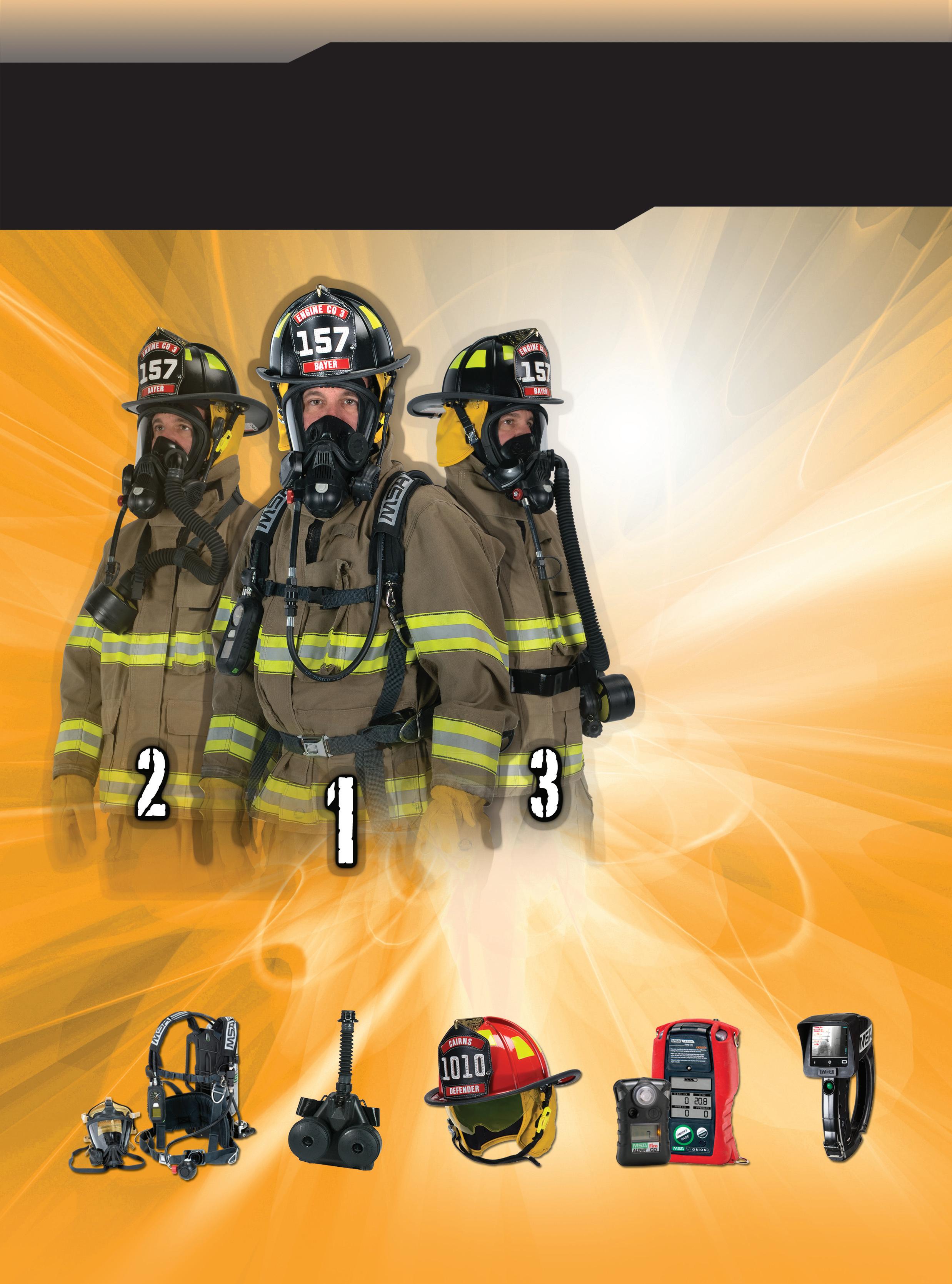

Fact is more firefighters across America rely on Scott Air-Pak® SCBA’s than all other SCBA’s combined. That’s why Scott is proud to be the first and only SCBA manufacturer to offer Upgrade Kits for both legacy NFPA 1981, 1997 and 2002 edition Air-Pak SCBA’s. These legendary Air-Pak SCBA’s incorporate Scott’s unique platform design, affording a dramatic increase in versatility, compatibility and compliance–traits not found in other SCBA’s. With Scott, you purchased a rich heritage of experience, unsurpassed engineering and quality, and the industry’s best warranty. And, that reflects well on you. Remember if it’s not an Air-Pak SCBA…it’s not a Scott.

Build on that Legacy

• Best warranty in class

• Lowest cost upgrade available

• Upgrade from NFPA 1981, 1997 or 2002 editions

• Upgrade to latest in technology

• Field upgradeable by Scott Authorized Service Center

• Now available to order and ship Visit ScottClassicUpgrades.com

by Paul Dixon

Canada’s population is aging. The first wave of baby boomers has turned 60 and entered retirement. StatsCan noted in the 2006 census report that by 2016 there will not be enough new workers entering the job market to replace those leaving through retirement. What does this mean for Canadian fire services?

We opted to look at composite departments from coast to coast – of which there are just over 200, according to the Canadian Association of Fire Chiefs – since we know many volunteer departments struggle with recruitment and retention and full-time departments have no trouble filling vacancies. Our informal survey of several composite agencies reveals a mixed response. Out west, in British Columbia and Alberta, there is at least anecdotal evidence of a deepening trend, while composite departments in central Canada and the Maritimes seem to be doing OK.

Dave Hodgins, managing director of Alberta’s Emergency Management Agency has heard enough complaints from around the province to initiate a formal survey on the question of recruitment but the data won’t be ready for some time.

In British Columbia, the Fire Services Liaison Group sent surveys on a wide range

of issues including recruitment and retention to the province’s more than 350 community based fire departments. The liaison group is made up of the Union of B.C. Municipalities and five groups representing operational firefighting in B.C. – The Fire Chiefs’ Association of B.C., The Fire Prevention Officers Association of B.C., the Fire Training Officers Association of B.C., the B.C. Professional Fire Fighters Association and the Volunteer Fire Fighters Association of B.C. The group is looking at potential new models for fire/rescue service systems. In its Dec. 1. draft report, of the 175 departments that responded to the survey, every agency that relies on volunteer or paid on-call fire fighters cites difficulty attracting and retaining members.

Over the past 20 years or so, many fire departments have become larger as a result of smaller municipalities amalgamating to form a single entity, either by choice or by decree of the provincial government. Halifax Regional Municipality and the City of Ottawa are two examples; the original cities formed the nucleus and adjoining smaller communities and rural areas were added to create the new mega-cities. The fire departments, as a result have career halls, composite halls in the outer suburbs and volunteer halls in the outlying rural regions.

Surrey, B.C., is evolving through a different model. Forty years ago, Surrey was considered a day trip from Vancouver –

somewhere out in the sticks. The fire department had four career halls and 12 volunteer halls. Twenty years ago it was the largest composite department in Canada, with more than 300 paid on-call firefighters. Today, as the city’s population rapidly approaches a half million, and Surrey has become the geographical centre of metro Vancouver, there are fewer than 100 volunteer firefighters in two composite halls and two volunteer halls, augmenting the 13 full-career halls. Deputy Chief Dan Barnscher acknowledges the dwindling reliance on volunteers. “We will still accept applications for paid on-call positions but we’re not actively recruiting for them.” Skill sets, equipment and apparatus have evolved as well. We all know there is much more to being a firefighter than fighting fires. This is reflected in the number of departments now known as fire rescue or fire and rescue. A retired B.C. chief recalls the process he took to become a paid on-call firefighter in his department. “Training was conducted by the career firefighters

Photo

Career and volunteer members of Halifax Fire and Emergency Services rush to reposition lines so Quint 5, a career truck, can be moved as it becomes threatened by a fastmoving fire in a large industrial/commercial building on the outskirts of Halifax in August 2008. The chief officer at left is a volunteer.

Volunteer members from Halifax Regional Fire and Emergency Services from Hubbards, an adjoining county to Halifax, work to extricate the lone survivor of a head-on crash on Highway 103 outside of Halifax in June 2008.

on shift at the time, generally three nights a month. It took about three years before you were fully qualified for interior attack and the like. You didn’t drive any department vehicles, even the pickup trucks. Only the career men drove the trucks. The selection process was by the other volunteers and not as it would be today, where the decision would be made by the chief based on competence. It was as much a popularity contest as anything. There was a long tradition of sons following fathers into the department as auxiliaries. It was important that you stayed around for a beer after practice, if you wanted to be voted in.”

When Wayne Williams joined Penticton Fire & Rescue as deputy chief nine years ago there was a waiting list for on-call firefighters. Today, as chief, he reports that he is unable to fill vacancies for on-call positions despite running recruiting drives twice a year. In Penticton, as in many other departments, career vacancies were filled from the ranks of the volunteers. Today, as many would-be firefighters are acquiring NFPA Level I & II accreditation before applying for a job, they are willing to travel further for employment. Williams has seen several of his on-call firefighters hired away by Vancouver, Surrey and Edmonton in the past two years.

Bernie Turpin, administrative chief with Halifax Regional Fire & Emergency Service, says his department has a fairly constant turnover rate of about 10 per cent from year to year, but it’s also in a unique situation with lots of military personnel living in the region. “They are generally willing volunteers but they are subject to transfers every few years.”

Ottawa Fire Services has a 10 to 15 per cent annual turnover rate in its volunteer and on-call ranks. Gordon Mills, deputy chief (rural services), says that while family and relationship issues seem to be cited during exit interviews as reasons for leaving the fire service, Ottawa has created a powerful attraction by consistently drawing a significant portion of its new career hires from the volunteer ranks.

Training is even more important for all those other duties that have become part and parcel of the firefighter’s day as well as public expectation: road rescue/extrication; rope rescue; confined space rescue; hazardous materials; marine firefighting; wildland firefighting; swift-water rescue; ice rescue; urban search and rescue; and medical first response. Once the skills have been acquired and a minimal level of certification attained, that skill level must be maintained. It takes time and commitment.

Continued on page 34

In January, we discussed when to implement a rapid intervention team. Now, we will consider where the RIT will be staged and some procedures to follow. Every department operates differently. Some want the RIT located far away from the scene, some want it near the incident commander and some don’t know where to put the RIT. I have been exposed to all three of these situations over the years. At one fire department, it was policy to have the RIT at the command post. This was done to ensure good communication between the IC and the RIT officer. The drawback to this is that if the command post is far away from the scene then the RIT is also far away from the scene. Staging the RIT with the IC works when the IC is located right at the scene. Another department I worked for places the RIT

wherever there is room or wherever it will be out of the way. This is the afterthought model of RIT staging and does not work because consideration for the RIT staging is a last resort rather than a priority.

Staging the RIT should be strategic, not by chance. When an officer arrives on scene, he should consider where to stage the various pieces of equipment, apparatus and operations to effectively combat the fire. The RIT is a part of the operations and equipment portion of the size-up. Strategically placing the RIT will increase the response capability and allow the team to conduct its operations (sizeup, progressive fire-ground preparations). Depending on the size of the building and the stage of fire growth, there may be a need to stage the RIT in two, three or four different locations.

I can remember a call we went to on a hot and humid August day. We responded

to a possible structure fire as the RIT. There had been a thunder and lightning storm in the area and the house had been struck by lightning. Once we arrived on scene our officer in charge met with the IC and got a quick report of the situation. There were flames visible and the crews inside were on an offensive fire attack. Our officer decided to place us at the four corners of the house. We were split into teams of four because there were offensive operations taking place all around the house. Our best access for a quick response was to be at the four corners of the house. Our officer sized up the situation and, based upon strategy, staged us in the appropriate positions. It might have been

Emergency responders require a secure rapid entry system that allows fast access without damage to property or delays waiting for keys. The Knox-Box® Rapid Entry System is a comprehensive UL listed key control system that includes high security key boxes, cabinets, key switches, padlocks, master key retention devices and locking FDC plugs and caps. Rely upon the Knox System for all your rapid entry needs.

Offering: A 2 course certificate in incident command for experienced incident commanders. Please contact our office for more information.

Are you looking to take on more responsibility in your Department? Trying to round out your technical ability with leadership skills? Preparing to advance your career?

At Dalhousie University we offer a three course program, the “Certificate in Fire Service Leadership” to career and volunteer fire officers.The 3 courses Station Officer: Dealing with People,Station Officer:Dealing with New Operations and The Environment of the Fire Station are all offered in each of our 3 terms, September, January and April. The program can be completed in one year.

For more information and a program brochure please contact: Gwen Doary,Program Manager Dalhousie University Fire Management Certificate Programs 201-1535 Dresden Row,Halifax,Nova Scotia B3J 3T1 Tel:(902) 494-8838 • Fax:(902) 494-2598 • E-mail:Gwen.Doar y@Dal.Ca

You will also find the information in our brochures or at the following internet address:Web site:http://collegeofcontinuinged.dal.ca

easier to stage us in one location near the truck or by the street but that would have been a “chance” staging choice.

So you have arrived on scene. Now what do you do? Well, the officer in charge should report to the area of the IC in front of the building and remain in visual/verbal contact with the IC or safety officer at all times. The initial meeting with the IC is to receive an update on the situation. At this point, the IC can designate the staging area or the officer may be elected to decide that. Usually the IC allows the officer to decide the best location for staging. Once staged, the officer needs to stay in contact with the IC. This can be accomplished either visually or by radio communication. The IC or safety officer should update the RIT officer on numbers of personnel in the building at all times. If the IC or safety officer is not updating the RIT, then the RIT officer should be asking.

Once staged at the preferred location, the RIT now needs to bring all its tools to the staging area. Too often the RIT gets caught off guard because it left equipment on the truck. The equipment needs to be where the RIT is. (Remember that we discussed in October the tools of RIT.)

The primary task of the RIT is to respond to any firefighter in distress, caught in a collapse, lost or disoriented, out of air or in a flashover/backdraft. The RIT is not supplemental manpower for advancing hoselines, conducting salvage operations, filling air bottles or conducting rehab. The RIT is there to rescue firefighters. I have seen the RIT assigned different tasks by the IC. If the RIT is busy setting up the aerial and a mayday call comes in, how effective will the response be? The RIT needs to be ready at a moment’s notice. On that hot, humid August day

• Conduct a 360-degree walk around; locate all entrances and exits and ensure they are accessible by both firefighters and the RIT.

• Place ground ladders at all windows. This gives access for the RIT as well as an escape route for the firefighters inside.

• Set up a safety hose-line for the RIT. If we need a hose-line for our operations, relying on the engine company to supply it is not guaranteed.

• Know what type of building construction you are dealing with. This will give the RIT some insight on what is happening on the inside and allow the team to predict fire behaviour and growth. If the RIT needs to go in, knowing the type of building construction will help in making entry and exit through enlarged openings.

• Be aware of the accountability system. Knowing how many firefighters are on the inside, and their positions, will give the RIT a leg up on the situation.

• Monitor fire conditions. This will help

when I was a part of the RIT for the structure fire, we were positioned to respond and we stood or knelt on one knee for about an hour in the humidity. We were ready to respond; it was boring watching the offensive operation but it was necessary to ensure a quick, rapid response. When the IC needed more manpower for different operations, he called in mutual aid – he did not resort to using the RIT.

The team must monitor the fire ground frequency at all times. You may get only one chance to hear a mayday over the radio. If RIT members are too busy setting up the aerial, they may miss that call. Being on the RIT doesn’t mean you are on break. You need to be proactive and attentive to what is going on around you. This takes concentration and dedication. (See sidebar above.)

We need to teach firefighters to call for help and declare a mayday even if they just feel like they’re in trouble. If they wait until the last minute to declare a mayday, when they know they are in trouble, it will be too late. Give your location, your condition, the number of people in your crew, your air situation and the fire conditions present around you. Activate your PASS alarm, assume a position that

the RIT keep ahead of the game.

• Assume the worst. If you are the RIT leader and you have been deployed, this will prepare you for the unexpected. If you respond ready for the worst, you will be ahead of the game; respond not prepared for the worst, and you will be caught off guard.

• Consider last known location of the firefighter. This information can be supplied by the IC or by accountability. Either way, it should be determined.

• Listen – radio, tapping, PASS, screams. This may lead you quickly to the location of the firefighter.

• Trace hoseline if one was used. This will also lead you to the location of the firefighter.

• Open all exits to ensure that a way in and out is secure and accessible.

• Provide for rapid ventilation. This will increase your visibility; will provide some relief for the firefighter and the RIT.

will maximize audible effects. Try to conserve air supply by remaining calm; use skip breathing or controlled breaths. Attempt to find a way out. Do not sit there and wait for the RIT to rescue you. Do something to save yourself. If we teach these basic principles to every firefighter, it will help rapid intervention teams in their efforts to rescue you.

Staging the RIT is an important function that should be looked at from a strategic perspective; once staged, team members need to be proactive. Remember, the team’s job is to rescue firefighters. Don’t just stand around and wait for a tragedy to occur; help to prevent one by removing potential hazards. Be proactive!

Mark van der Feyst began his career in the fire service in 1998 with the Cranberry Township Volunteer Fire Company, Station 21, in Pennsylvania. He served as a firefighter and training officer for four years, then joined the Mississauga Fire & Emergency Services, where he served for three years as a firefighter and shift medical instructor. He is now with the City of Woodstock Fire Department in Ontario.

Aluminum & Fiberglass Fire Service Ladders

Our ladders feature Duo-Safety's famous tongue and groove construction

Our light weight design is cost effective compared to other competitors

Exclusive Welded and Expanded rung design offer the strongest rung to rail connection possible

Repaired rungs are same as factory original and can be repaired as many times as needed

Rungs never come loose

Continued from page 29

Mills from Ottawa says, “keeping their time structured, productive and fun is the key. Instilling a sense of pride with station clothing, uniforms, proper gear and reliable equipment that they feel competent in operating, all contributes to building a team and instilling a sense of ownership.”

It takes many hours of drill and training to meet minimum standards for volunteer or auxiliary firefighters. Even those arriving with Level I & II require a structured introduction and orientation into the department. Over the past 20 years, occupational health and safety, workers compensation legislation and ultimately Bill C-45 have put the onus on the employer to be proactive in providing the right equipment and training to do the job and responsible supervision, along with appropriate documentation.

For paid on-call and volunteer firefighters, responses during working hours can place a strain on their employers as call volumes rise in growing communities, especially between nine and five, Monday through Friday. Dave Mitchell, former communications chief with Vancouver Fire & Rescue and now a consultant, has done call-volume surveys for communities demonstrating that the hours of peak demand for firefighter availability are also the hours of lowest availability. There is a critical mass of population, call volume and public expectations that ultimately sees a community completing the volunteer-composite-full career staffing model. There are tipping points along the way, tied to the ability of the community to finance the change to career from volunteer.

The fixed costs associated with maintaining a fire department will remain constant whether the agency is made up of volunteers, career firefighters or a combination. The costs of the building, apparatus and equipment are the same. The variable in the equation is the cost of the human factor. Volunteers or paid on-call firefighters represent a fraction of the costs associated with a full-time, career position no matter how the volunteers are remunerated – honorarium, stipend or pay per call. As budgets have tightened over the past decade, and with that belt tightening now exacerbated by the economic events of the past year, many communities may have reached the point at which they should move to full-time firefighters, at least for the Monday to Friday daytime hours, but they just can’t afford to do so.

Continued from page 16

for firefighters. They never really know what hazards they will encounter, and what dangerous materials may be involved in the blaze.

“The toughest part about industrial training is that the requirements vary from site to site,” says Shubert. “Each department has to investigate the industrial sites in their jurisdiction to decide what range of skills are required. Not only do you have to assess hazmat requirements and potential chemical risks – including what dangerous substances are on site and how they are stored – but you have to decide what skills may be required.”

The good news: “Most industrial sites have their own corporate fire departments, and they are usually very knowledgeable about what the risks are and how they are to be contained,” Shubert says. “The most difficult part is ensuring that the corporate department and your own are ready to work together effectively before something happens, which requires preplanning and co-ordination”.

Our final example of specialty firefighting is the very changeable wildland fire, governed by wind speeds and direction, available fuel sources and human carelessness. Unlike urban fires, wildland fires are extremely unpredictable and volatile. If the weather goes against you, sometimes containment is the only option and sometimes it doesn’t work.

“Wildland fires are extremely unique in their behaviour,” says Shubert. “For the urban firefighter, they represent real challenges because there are new tactics that have to be learned, including how to position and build fire breaks and trenches, how to work with

Hazmat training is so specialized that in most cases it is taught at post-secondary institutions rather than at the department level.

limited water resources and so forth. This is a skill that requires real training to master.”

As the list above illustrates, there is a range of specialty fire fighting skills that your department may need to master, depending on the challenges in your territory. Trying to quantify the costs of such training is difficult, since such costs are based more on what a department can afford to spend versus how much it needs to spend.

As is often the case in Canada, our fire departments figure out what threats are the most prevalent, and train for them as best they can with the resources they’ve got.

The bridge to your future

•MUNICIPAL FIRE FIGHTING

• HAZARDOUS MATERIALS RESPONSE

• INDUSTRIAL FIRE FIGHTING

• CONFINED SPACE ENTRY/ RESCUE

• INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEM

• CUSTOM TRAINING TO MEET SPECIFIC NEEDS

• PRE-SERVICE FIREFIGHTER EDUCATION and TRAINING CERTIFICATE PROGRAM

• FIRE SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY DIPLOMA PROGRAM

FIRE & EMERGENCY RESPONSE TRAINING CENTRE

Raise awareness about hazardous materials/WMD incidents and give responders the knowledge they need to address emergencies safely, competently, and efciently. The fully revised and updated Hazardous Materials/Weapons of Mass Destruction Response Handbook delivers facts and authoritative advice —information that prepares rst responders and medical personnel for challenges in today’s world.

This powerful resource contains:

The full texts of the 2008 NFPA 472: Competence of Responders to Hazardous Materials/Weapons of

• Mass Destruction Incidents and the 2008 NFPA 473: Competencies for EMS Personnel Responding to Hazardous Materials/Weapons of Mass Destruction Incidents.

A wealth of authoritative commentary that provides vital input on the safety and protection of

• awareness-level personnel, operations-level responders, hazardous materials technicians, EMS personnel, and other specialists.

• Fully updated Supplements.

Separate indexes for Standards and commentary that help streamline searches.

• Item#: 472HB08

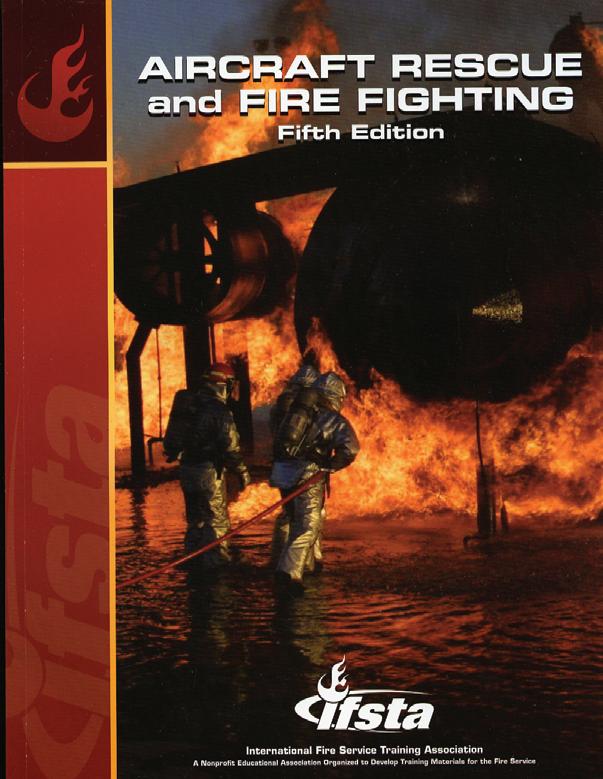

The 5th edition

This new and improved version of the original best seller, Incident Management for the Street-Smart Fire Ofcer, is for everyone who wants to learn new ways to enhance the ow of their re department’s management system. Whether you are a reghter looking to become an ofcer, or an ofcer whose future probably includes the word ‘Chief’, you will benet from this book.

Item#: 1593701505

Price: $93.14

and

ghting (ARFF) personnel, aircraft and airport familiarization, safety and aircraft hazards, ARFF communications, extinguishing agents, ARFF apparatus, rescue tools and equipment, ARFF driver/operator, airport emergency planning, and ARFF strategic and tactical operations.

CUSTOM TRAINING PROGRAMS: MESC will provide custom design training programs. Other courses available include: Building standards, Rescue program, Emergency Medical, Management Program, Fire Prevention, Public Safety and Hazardous Material. Manitoba Emergency Services College, Brandon, Manitoba, phone: (204) 726-6855.

LIVE FIRE FIGHTING EXPERIENCE: Short and long term courses available, Municipal and Industrial fire fighting. Incident Command System, Emergency Response/HazMat, three year Fire Science Technology Diploma program. Lambton College, Sarnia, Ontario, call 1-800-791-7887 or www.lambton.on. ca/p_c/technology/fire_emerg_resp.htm. Enroll today!

The best bet

A little bit of superstition goes a long way

C’mon Reed, buy a ticket.”

My grandfather kept his wallet firmly in his pocket. “Sorry, I don’t gamble.”

“But all the proceeds are for charity.”

Grandpa hesitated, then pulled out a dollar. “Here, but don’t put me in the draw.”

A few nights later, Grandpa heard honking and voices outside his bedroom window.

“Come out and get your prize Reed!”

He looked out, prepared for a practical joke. Instead, he saw a shiny yellow Crosley convertible. Grandpa’s friend had entered his name, and in spite of his scruples, he hit the jackpot. The car became the primary transportation for my mother and aunt during college.

I think all of us are gamblers to some degree. Look at highway crash statistics. Just my small department responds to 25 or 30 vehicle crashes a year on our lonely stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway. Considering that a rough average of 2,500 vehicles drive through here every day, those aren’t bad odds for the travelling public, but smart people still use lucky charms called seatbelts.

Some folks avoid anything that looks like gambling. I heard about a guy who didn’t like life insurance. His reasoning? He didn’t want to bet the insurance company he was going to die. And it seemed strange the insurance company was betting he wasn’t. An unusual way of looking at things, but it makes sense in a weird kind of way.

Luck? Now that’s even scarier than gambling. It could be defined as that last-ditch, end-of-the-rope factor that swings the balance in our favour when all else fails. It’s an interesting study to examine the dozens, perhaps hundreds, of lucky charms and quirky rituals we firefighters enlist to encourage fate’s smile; shamrocks, lucky coins, St. Florian necklaces. Some firefighters religiously refuse to clean their helmets. Most will give you a severe look if you say, “Man, it’s been quiet lately.” Some departments have superstitions about food. We went through a spell where we’d get a call every time one of our crew ate chocolate cake with a spaghetti dinner. It started out as a humorous observation, but after the third time we began to wonder. My kids even started picking up on it.

‘ Many of us vehemently deny any superstitions, but even a skeptic like me has to wonder sometimes.’

Firefighters are not exempt from taking a gamble now and then. In my rural department, we make a decision early on at every fire: is a pumper and tanker enough water to do the job? If not, the porta-tank comes off the truck and we start a water shuttle. This takes time and manpower – which we usually don’t have – so sometimes we hook the tanker directly to the pumper and go for broke. It only takes a few minutes to know if we made the right choice.

You might argue that a calculated decision isn’t a gamble. You do your size-up and make your decision. Simple. Except that there always seems to be that unknown factor that you find out after the place burns into the basement.

Of course, there are things that we do know ahead of time. In many northern departments mutual aid is so far away that they’ll arrive just in time to roast marshmallows. We don’t mind sharing, but they can roast them just as well over their own basements, so we don’t usually bother calling.

Other things you learn on the spot, like the time a trucker stuffed a mitt full of papers in my hands and wished me luck as he took off the other way. His burning truck was carrying corrosives, flammable liquids and radioactive materials. We managed the incident safely, but afterward I had to admit that we left a little too much to luck.

Many of us vehemently deny any superstitions, but even a skeptic like me has to wonder sometimes. Last fall, a hunter asked me if we responded to many moose hits on the highway. I said we did a few, but hadn’t had any for a while. Oops. I had this weird feeling as the words came out my mouth, but I consciously told myself that I didn’t believe that superstitious stuff. You weren’t going to catch me knocking on wood. A few hours later, my pager went off with a report of car versus moose east of Upsala.