NOW MORE THAN EVER.

Canadians want fresh, high-quality Canadian chicken and our farmers are proud to raise it to some of the highest standards in food safety and animal care. That’s what “Raised by a Canadian Farmer” means.

6

by Brett Ruffell

Canada’s supply management system has long been a target in trade negotiations with the U.S., and recent developments suggest we may be heading for another battle. While our government insists further concessions are not on the table, history –and the unpredictability of a Trumpled administration – suggests we should remain on high alert.

International Trade and Economic Development Minister Mary Ng recently reaffirmed Canada’s commitment to protecting supply manage-

“Strong rhetoric doesn’t always mean an unyielding position at the table. Vigilance is key.”

ment. In an interview on CTV News, she stated unequivocally that Canada would not concede on the issue, a sentiment echoed by Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly. However, this resolve will undoubtedly be tested as tensions rise south of the border.

Trump and his allies have made it clear that Canada’s supply management system is in their crosshairs.

Commerce Secretary nominee Howard Lutnick has accused Canada of treating U.S. farmers “horribly,” and Trump has lamented the lack of access for American agricultural products. Given that supply management was

already partially weakened during the CUSMA negotiations in 2018 – with Canada further opening portions of its domestic market to foreign competition – some experts expect the U.S. to push for greater concessions.

CUSMA’s dispute settlement process has already been used multiple times regarding dairy, with mixed results. These rulings highlight ongoing friction and the likelihood of further challenges that could extend to poultry, eggs, and other supply-managed commodities. With CUSMA up for review in 2026, Trump’s aggressive trade rhetoric and U.S. agricultural lobby frustrations suggest supply management could be a major point of contention.

Some believe modernization of the system may be necessary to address transparency concerns and ease tensions, while others warn that any erosion could destabilize the sector and leave Canadian farmers vulnerable. For now, Canada’s stance remains firm. But strong rhetoric doesn’t always mean an unyielding position at the table. With an unpredictable U.S. president, vigilance is key.

In a new podcast series, I spoke with leaders from different poultry sectors about these uncertain trade headwinds and what to expect in the year ahead. Listen to those conversations at canadianpoultrymag.com/ podcasts.

canadianpoultrymag.com

Reader Service

Print and digital subscription inquiries or changes, please contact Angelita Potal, Customer Service Rep.

Tel: (416) 510-5113

Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Editor Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

Brand Sales Manager

Ross Anderson randerson@annexbusinessmedia.com Cell: 289-925-7565

Account Coordinator

Julie Montgomery

jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5163

Media Designer Lisa Zambri

Group Publisher Michelle Bertholet mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Manager

Anita Madden amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5183

CEO Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Subscription Rates

Canada - Single-copy $10.00

Canada – 1 Year $33.15

Canada – 2 years

GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2025Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

LUBING’s eFlush regulator reduces labor, saves time, and ensures flushing is being done, and being done properly.

Easily control your water pressure and flush your lines with half of a turn of the regulator knob, or automate the process with our eFlush option. LOWER MORTALITY AND IMPROVED FEED CONVERSION

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664-3811

Fax: (519) 664-3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

Les Equipments Avipor Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263-6222

Fax: (450) 263-9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963-4795

Fax: (780) 963-5034

By Dr. Gigi Lin

Dr. Gigi Lin is a board-certified poultry veterinarian. She provides diagnostic, research, consultation, continuing education, and field services to all levels of the poultry industry in Western Canada. In this column, she will share case-based reviews of brooding best practices.

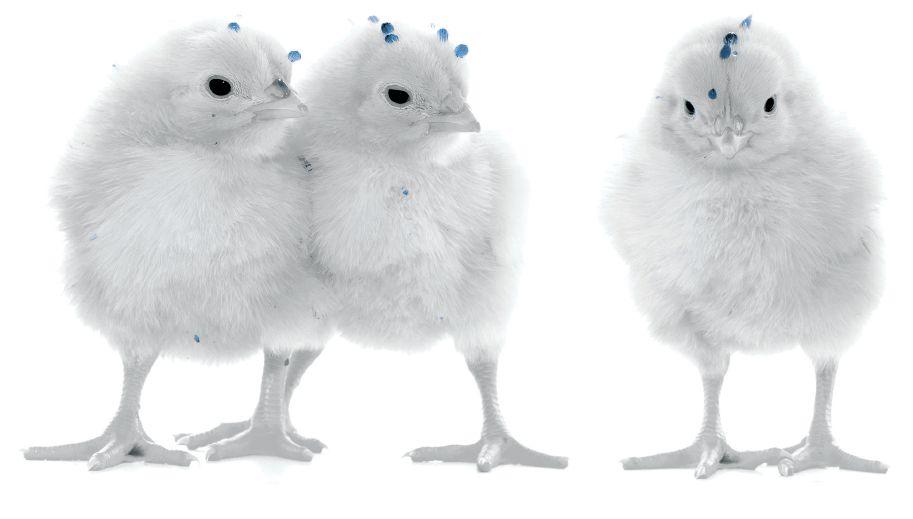

In the past two years, I’ve been hearing from more and more producers who are struggling with chick quality and performance issues. The recurring factor seems to be breeder flocks being kept longer than usual due to shortages caused by avian influenza. One producer I spoke with shared how their day-old broilers arrived weaker than expected with inconsistent body sizes. Despite their best efforts, these chicks struggled to thrive, requiring extra care and attention just to reach average performance.

This isn’t an isolated problem. Across Western Canada, breeder shortages caused by avian influenza have forced the industry to extend the production age of breeder flocks beyond their optimal range. While this is necessary to maintain the supply of chicks, compared to prime-aged breeders, older breeder flocks often produce eggs with poorer shell quality, lower hatchability, and, in some cases, chicks with inconsistent body weights.

Some producers face the added challenge of receiving chicks transported over longer distances or delayed placement, further increasing stress on already vulnerable birds. These challenges inevitably trickle down to broiler farms, where producers must put in additional efforts to navigate the compounding effects of compromised chick quality.

I would like to take this opportunity to highlight some practical tips for producers who are facing these challenges. These chicks require more careful brooding management to support weaker chicks and improve their performance, helping to offset the challenges posed by AI-related breeder shortages.

Weaker chicks are especially sensitive to temperature fluctuations; even slight differences of 1°F can significantly impact their health and performance.

To reduce cold stress, barns should be preheated thoroughly, and drinking water should be flushed well in advance – especially in cold weather. Check temperatures particularly under the brooders and eliminate drafty spots.

Hatchery and producers should carefully consider every step involved in transporting chicks from the hatchery to the farm. Hatcheries should ensure transport truck environments are well-controlled, providing consistent temperatures and uniform air flow.

Upon arrival, trucks should be parked so that chick boxes are shielded from direct wind during unloading.

Truck drivers and farm managers should move all the chick boxes into the barn first before placing the chicks on the floor, so that the chick boxes are not left outdoors to be exposed to coldness.

As I mentioned in the previous article, do not overly rely on the readings from in-house barn computer systems. To minimize operation errors, use handheld infrared thermometers to spot-check temperatures in various areas.

Depending on the size of the chicks, inspect and adjust feeder heights, waterline height, and water pressure upon chick placement. Make it easier for smaller chicks to access feed by placing additional feed on chick

“These challenges inevitably trickle down to broiler farms.”

paper or trays. Check crop fill after 24 hours, aiming for at least 95 per cent of chicks to have feed and water in their crops. If the target isn’t met, investigate why they aren’t eating or drinking adequately.

If additional stressors are anticipated, such as prolonged transport times, consider adding electrolytes and vitamins to the water for the first 24 to 48 hours as a supplementary source of nutrients. Do not forget to ensure the feeding areas are well-lit to attract chicks to feeders as soon as they arrive.

Under cold and windy conditions,

I highly recommend farm managers to spend more time in the barn observing chick behaviour during the first 24 to 72 hours. Are they huddled under the heat source? Are they panting or moving away from the heat? Are they spending too much time on the waterline? Is all the equipment operating properly? For a comprehensive evaluation, I suggest using a brooding checklist to guide adjustments to key factors like temperature, feed, light, air, and water (TFLAW). If you notice signs of illness or unusual increase in mortality, contact your veterinary or poultry pathologist immediately to obtain accurate diagnosis and timely interventions.

prolonged period of time.

Finally, collaboration with hatchery suppliers plays a crucial role in managing chicks with suboptimal quality. I always encourage producers to maintain open communication with their hatchery to gain insight into egg sources, breeder flock age, and hatching conditions.

By Treena Hein

According to poultry barn light researchers such as Dr. Karen Schwean-Lardner and Dr. Trever Crowe at the University of Saskatchewan, about 80 per cent of poultry farms in that province have now switched to LED. That’s probably representative of the national picture, and in the next few years, most of the remaining Canadian poultry farmers with old systems will have replaced them with LEDs, for energy savings and more.

Of course, electricity use reduction from switching from incandescent to LED is very high. Alabama-based poultry light consultant Kyle Keeton at SBS Electric Supply says he’s seen it as high as 79 per cent. And while Dr. Grégoy Bédécarrats of the University of Guelph explains that the efficiency of fluorescent lights is not that much lower than LEDs, fluorescents are hard to dim.

That’s a problem when poultry farmers need lower light intensity

in the barn and/or want to provide their birds with the many benefits of dusk/dawn transitions. Fluorescent lights also tend to have significant flicker (see sidebar), which causes stress to birds.

Regarding ROI for LEDs, Crowe says it’s rapid – they are so much more efficient at converting electricity to light energy – but it’s hard to give a timeline of when they’ve paid for themselves in a particular barn. “LEDs are more efficient in their ability to convert electrical energy to light, at about 100 lumens/Watt used compared to incandescent bulbs at about 15 lumens/W and fluorescent at 60 lumens/W,” he says. “The light experienced by the birds depends on the style and number of fixtures. It also depends on their spacing, reflectivity of surfaces, how far they are from the floor, and so on.”

Longevity of your LED bulbs is also an important factor in ROI. Bédécarrats explains, “you generally get what you pay for. The key component is the driver (electronics), with large differences in capabilities and reliability. The quality of its components will dictate the ability to dim, the flicker rate, harmonic distortion and the half-life of the bulb. Cheaper bulbs tend to use lower-quality electronics and are typically designed for household use.”

“LEDs are more efficient in their ability to convert electrical energy.”

Bédécarrats has been involved in the development of an LED bulb called Agrilux, designed from scratch to be used in poultry farming, where “every piece, from housing unit to sealant and electronics, was optimized for barn use and supported by on-farm data. We also played a lot with the spectral output to design sector-specific lighting.”

The life expectancy of the Agrilux bulb is 40,000 hours, about seven years in a layer barn and 10 years for broiler/broiler breeder barns, says Alex Thies, president of AgriLux Lighting Systems and Thies Electrical Distributing in Cambridge, Ont. He notes that his competitors with poultry-barn-specific lighting claim bulbs will last 50,000 hours.

Thies explains that with electricity costs savings, benefits of better egg production, feed savings and more compared to previous flocks on old lighting, his customers report ROI of 12 to 15 months. He’s sold systems so far in Canada, the U.S. and Puerto Rico, “in existing and new layer, pullet, broiler, broiler breeder, turkey poults and grower barn operations.”

Bédécarrats also points out that in barn lighting retrofits, the cost of installing LEDs will depend on the configuration of the existing system.

“For example, if you’re using a standard Edison socket you can easily retrofit to the Agrilux bulb but if you have fluorescent tube lighting, it may require re-wiring,” he explains.

“In the end, the other important part is the controller. Older control panels may not be compatible with LED lights, as they were not designed to handle low-energy output. In practice, using an incandescent bulb at the end of the line may be trick to help equalize the load.”

40,000 is how many hours the Agrilux bulb is expected to last, equivalent to about seven years in a layer barn and 10 years in broiler/ broiler breeder barns.

Schwean-Lardner also notes that dawn-to-dusk dimming saves a bit of power, but can also provide significant savings in preventing bird injury and death. “It’s a simple thing you can do with any type of light, to phase the light coming on or going off over five to 10 minutes instead of a sudden on-off,” she explains.

“Quite a few producers are doing it, and we’ve been talking about the benefits of this for a decade. Most light controller systems offer this as a setting, but in the older systems, you can stagger the banks of lights coming on or off and achieve a similar effect. It’s so important for bird welfare. They’re much calmer when they go to sleep and when they wake up.

It’s especially important at the

start of the day. You don’t get crowding at the feed line, which can cause injury and the need to cull.”

Similarly, there are costs savings in improving bird health, welfare and productivity through eliminating flicker. “With turkeys, for example, flicker causes them to attempt to hide and then they are not eating and drinking,” Schwean-Lardner explains. “We’ve looked at some chicken barns in Canada and it was quite severe in some of them.”

She and Crowe explain that LED systems produce flicker with dimmer systems that use electrical pulses. “It’s not apparent to the human eye past a certain frequency, but it may be to birds,” says Crowe, “so ask about borrowing a spectrometer (they cost about $5,000) from a hatchery or your provincial board. Some of the boards may have them

now. This device will show you light intensity (in units of lux or clux –see sidebar), light intensity as a function of wavelength and flicker frequency.” He adds that cellphone cameras with a high ‘shutter speed’ might detect the presence of flicker, but they typically don’t have software to calculate flicker frequency. If your frequency is at or below 119 hertz, you need to take action.” As Schwean-Lardner explains, “there may be a cost to dealing with it, but what’s the cost of ongoing negative effects on feeding, bird health and welfare?”

Explore Gradient Lighting – Consider gradient lighting, which is also actively being explored as an enrichment (giving the birds a choice of lighter and darker areas of the barn).

Essential light lingo: A quick guide

kWh

Unit of electrical power usage. One kilowatt-hour equals the energy delivered by one kilowatt of electricity over one hour.

Watt

Unit of energy/ power. Measures how much energy is transferred over time. Higher Watt bulbs use more power and consume more electricity (kWh).

Lumen

Unit of light intensity. It measures the total amount of visible light emitted by a source.

Lux

Measurement of brightness. One lux is one lumen per square meter. (Clux: lux corrected for light color.)

Wavelength

Characteristic of light, representing the length of a light wave (crest to crest). The visible spectrum is 380-740 nm in wavelength and 405-790 THz in frequency.

Flicker

Visible change in light intensity, caused by fluctuations in light generation, power supply, or dimmer incompatibility. Birds can detect flicker levels that humans cannot. Measured in hertz.

Optient, for example, is the newly released broiler gradient lighting system from U.S.-based Once by Signify, designed to focus most of the light on a small area of the barn floor near the feed lines (~200 lux) while the rest of the floor remains dim (<1 lux). “The design of this system allows it to consume approximately five times less power usage than traditional ceiling-mounted lighting systems,” says Joshua Munion, the firm’s engineering leader. “In addition to the energy savings, the Optient system has been shown to improve feed conversion by up to four points, resulting in significant cost savings.”

Test Before Committing – Don’t just believe what is written about bulbs on the package or marketing sheet, says Munion. Get some samples and test them. “Maybe install a couple of competitor lights and run them side by side in your barn to see which is a better fit,” he suggests. “Make sure the replacement bulbs are compatible with your dimmer.”

Keep Lenses and Heatsinks Clean – Munion also advises regularly removing dust buildup from the heatsinks and especially dirt off the lens of your lights, which

can cause the lenses to brown and produce less light over time.

AI-Integrated Lighting is the Future – Note that future barn lighting systems will integrate with AI, says Munion. For example, if the software detects bird crowding in a corner from a camera feed or heat or motion sensors, it can adjust lighting automatically to hopefully ameliorate the situation.

This turnkey operation boasts 4 two-storey barns with a total capacity of over 160,000 birds: 42.5 × 228 ft, 50 × 200 ft, and two 50 × 260 ft barns. Equipped with Maximus Computers, Cumberland feed pans, Ziggity drinkers, and Re-Verber-Ray tube heating. The property features 2 separate 400-amp services, 2 drilled wells, 2 natural gas standby generators, and revenue from a cellular tower. Residential buildings include a solid family home with a 1-bedroom suite and a mobile home for staff. Additional structures include two shops (40 × 72 ft and 30 × 40 ft), a hip roof barn, and a cow barn. High, dry land is prepped for expansion. Approx. 85,000 birds of BC broiler chicken quota available at market price!

A unique coccidiosis vaccine that balances the safety and efficacy needed for poultry that are raised without antibiotics, or in management programs to reduce resistance against anticoccidials.

By Brendan Graff

To attain high performance, the optimal microclimate in the barn must be provided using sufficiently energy-intensive ventilation and heating (cooling) air systems. Energy conservation is critical since it can range from 10 to 15 per cent of the total cost of production. There are simple and cost-effective ways to conserve energy, especially during cold weather.

A simple negative pressure test can be done to determine how well the house is sealed. Begin by closing all inlets and doors and turn on a fan capacity equivalent to 0.28 m 3/min for every square metre of floor area (1 ft3/ min for every square foot of floor area). Keep in mind that the fan capacity and floor area will not match exactly. Measure the pressure drop across any inlet or door. If the static pressure is approximately 37.5 Pa (0.15 IWC), then about 55 to 60 per cent of the air is entering the house through the inlets. In a newly built house, the pressure should be approximately 60 Pa (0.25 IWC), which means more than 70 per cent of the air enters through the perimeter inlets. Any result below 25 Pa (0.1 IWC) indicates a poorly sealed house. Energy lost during windy winter conditions will be very significant for poorly sealed houses, because, as wind speed increases, the pressure drop becomes greater. A wind

gust of 25 kph (15.5 mph) can produce a pressure drop of 27 Pa (0.11 IWC), which will result in significant energy loss in a house with poorly sealed inlets.

Perimeter inlet choice is closely associated to barn tightness and energy efficiency. In a well-sealed poultry house, more than 70 per cent of the incoming fresh air enters

through the perimeter inlets during minimum ventilation. Well-designed inlets are well insulated, which is particularly important in cold climates.

In extreme weather, preventing condensation and freezing of the inlets will always be a challenge for producers, making insulation essential.

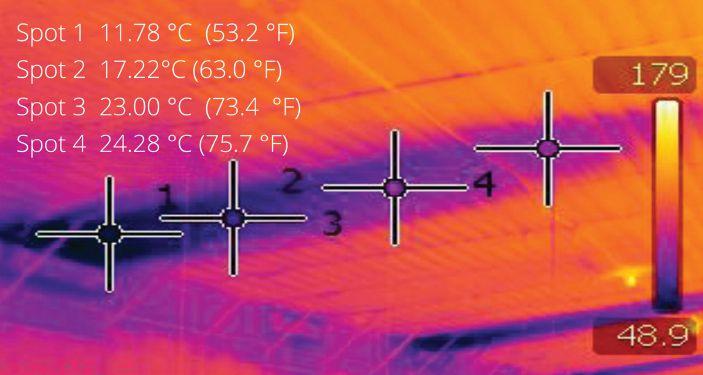

A well-designed inlet will always be recessed within the wall and have curved directional blades. This installation and design will ensure the cold incoming air jet reaches the center of the house before detaching from the ceiling (Figure 1). Bigger or wider perimeter inlets may be less expensive but cannot direct the cold incoming air jet correctly.

The perimeter inlets system is a small part of any new barn construction project but is arguably the most important. A continuous inlet is an example of an inexpensive alternative which will invariably leak and fails to correctly direct the incoming air jet especially during minimum ventilation.

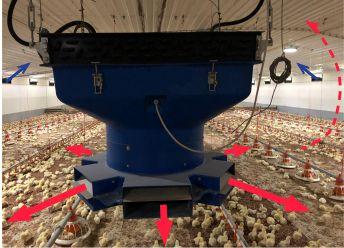

The circulation fan system is an essential requirement for all poultry barns. Its primary function is to break up the natural stratification created by the heating system and evenly distribute heat throughout the house. It ensures that temperatures are uniform from front to back, and side to side. These systems will always be operational when the barn is in perimeter inlet ventilation mode. They ensure even litter temperatures throughout and play a key role in moisture removal.

There are two types of circulation fan systems, horizontal and vertical. The horizontal system is made up of several small fans which work together as a group to provide destratification, air movement and circulation through the entire house.

The horizontal system is by far the most popular and less expensive of the two. In contrast to horizontal systems, vertical circulation fans work independently to provide destratification, air movement and circulation but within the zone around the fan (Figure 2).

There are many different configurations for the horizontal systems,

The Rotary Fork is designed and built in Ontario with the input from local poultry producers, ensuring it meets the needs of the industry. Its innovative design allows for faster and easier leveling of bedding, saving you time and money. With the Rotary Fork, you can use less bedding and achieve a flatter surface, ensuring that water nipples are at the same height for every bird.

The Rotary Fork is more efficient than hand spreading or blowing, saving you time, diesel, and wear on your tractors. Its effectiveness has been proven by broiler producers, who have seen the benefits of using the Rotary Fork in their barn operations. With the Rotary Fork, you can achieve the perfect level of bedding in three simple steps, making it the ideal solution for starting chicks.

Choose the Right Size for Your Needs—available in 10' and 6' forks— fitting standard doors. Whether you have a one, two, or three-story barn, the Rotary Fork is available in many popular attachment configurations. Choose the right size for your needs and see how the Rotary Fork can revolutionize your barn operations.

the simplest being a single row of fans straight down the center of a narrow barn.

In barns that are 16 m (50 ft) or wider, a double row of fans will be a good option. With a simple configuration in a 12 m (40 ft) wide barn, the fans start in the center and move air to opposite ends of the barn (Figure 3).

By Jane Robinson

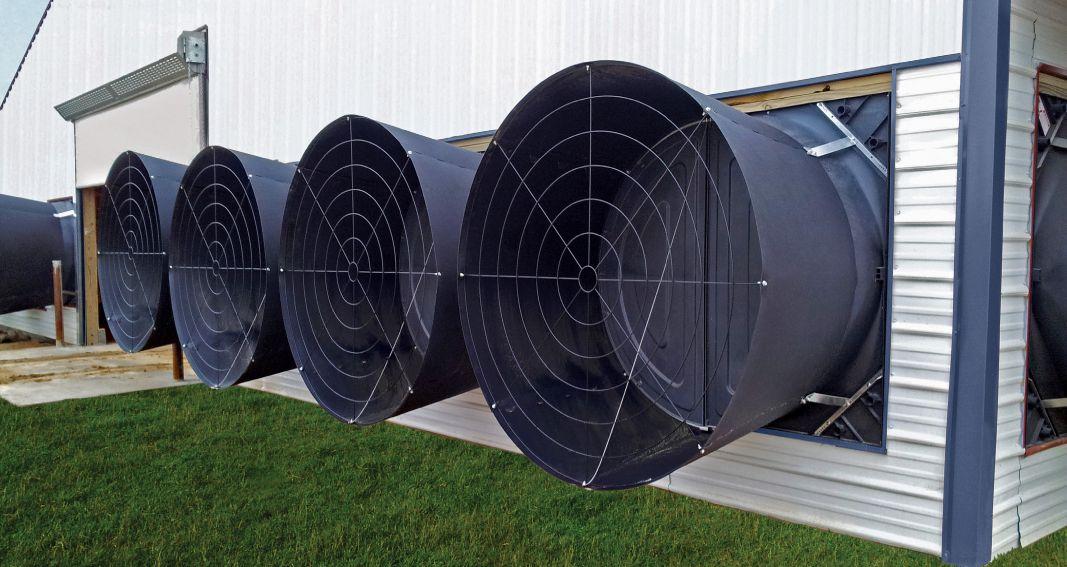

There’s no sign that energy costs are headed down, and wherever you farm in Canada, chances are temperature fluctuations are adding a new element to managing energy use and barn conditions. We looked at some of the latest options and technology in barn ventilation and insulation designed to optimize temperature, humidity, ammonia levels and airflow to balance bird health, performance and productivity with energy consumption. Whether you are looking at upgrades and retrofits to an existing barn, or a new build is on the books, here are some new ideas for air inlets, fans, controllers and insulation.

Tyler de Boer doesn’t need to work too hard to make ventilation matter to poultry producer customers in B.C. “Ventilation is always at the forefront and very important to producers because of the impact on bird health,” says de Boer, general manager of AgPro West Supply Ltd. in Abbotsford, B.C. “As we get a better understanding of how avian influenza spreads, we’ve been focusing on adding a filtration system to existing barns and into new builds as a preventative measure to remove dust and potential pathogens.”

Filters can be sized to fit air inlets as a simple upgrade to existing barns, and are becoming more important in densely populated poultry areas like B.C.’s Fraser Valley, where biosecurity has never been more

Mark Franklin and his wife Rosie manage broiler and hog operations for J&B Millen Farms in Great Village, N.S., as well as operating their own beef farm nearby. They are finishing up a new broiler barn with SKOV, after seeing the benefits with the company’s new build of two hog barns on the farm. Ventilation for the new 26,000 bird barn will be outfitted with SKOV air inlets, fans and controllers.

They’ve been happy with the company’s ventilation system in the hog barns and are looking forward to extending similar benefits for the broilers. “I am looking forward to the artificial intelligence built into the new controllers that anticipates the adjustments needed in the barn,” says Franklin. “I always seem to be playing with barn controls but I expect there will be less tweaking required with the new system, as well as better energy efficiency.”

The first birds are set to arrive in the barn at the end of March. To measure the efficiency of the new system, they’ll be tracking daily data on bird performance and heating costs, as well as watching how the birds act in the new space. “SKOV does a good job of controlling the environment for the animals, so we’re looking forward to that in the new barn,” says Franklin.

important considering its proximity to a major migratory route for wild birds.

“Pretreating the incoming air has become a bigger priority through filtration and the use of UV light as another option that is coming up,” says de Boer.

Poultry equipment manufacturer Chore-Time sees direct drive fans as part of the newer innovation in barn ventilation. “We’re really seeing a push for direct drive fans that have variable speeds to replace belt drive fans,” says Mindy Brooks, director of corporate marketing, advertising and communication for CTB, Chore-Time’s parent company, in Indiana.

Belt drive is the older, more familiar technology in poultry barns that is on or off, with no in between speed options. Direct drive fans are a newer technology where the fan blade is attached directly to the shaft of the motor, eliminating the belt and pulley system with belt drive fans. “One of the biggest benefits with direct drive fans is that you’re eliminating a lot of the maintenance that is required on belt drives,” says Brooks.

Add to that the ability to run direct drive fans at varying speeds, giving you more control over airflow and temperature with the greatest efficiency when fans are running at 60 to 80 per cent speed. That variability drives the energy efficiency aspect of these fans – running more fans at a lower speed is more efficient than fewer belt fans at full speed.

“It’s kind of counterintuitive but the sweet speed spot for direct drive fans allows you to get the same performance and airflow at a lower speed for a lower energy cost,” says Brooks. Plus, motors on direct drive fans tends to be

Ampex panels are encased in concrete for increased heat transfer to help achieve desired barn temperatures faster.

Alleguard manufactures insulating building materials with two main product lines for poultry barns.

• Ampex hydronic insulated panels deliver in-floor radiant heating for even heat distribution to consistently warm the barn closer to where birds are. There is a higher upfront cost with this type of heating in a new build, but over time producers can expect lower heating costs, humidity and C02 levels, and reduce the amount of bedding needed in the broiler barn.

• For wall insulation, Amvic’s insulated concrete forms (ICF) are a cost effective, durable and energy efficient alternative to traditional wall assemblies. With its airtight building envelope, ICFs are resistant to termites, rodents, mold and mildew.

quieter, more efficient and require less maintenance.

Chore-Time has a retrofit kit for customers using their belt drive Endura fans to make a simpler switch to the EnduraMax direct drive fans. Switching from belt drive to direct drive also brings the options to upgrade controllers to simplify the process for real-time tracking of barn variables and automatically adjusting fan speed.

“We’ve seen the market adopting direct drive fans a lot over the last three to five years as producers see the value in reduced maintenance and better energy efficiency,” says Brooks.

Higher energy costs in Canada, compared to the U.S., can

mean a shorter return on your investment in upgrading ventilation equipment. “And when you’re getting the correct performance from your ventilation, you’re going to get better bird performance, better floor quality and lower disease rates,” she says.

As barn ventilation becomes more adept at maintaining ideal bird conditions, controllers are keeping pace with new, smarter options.

James Black points to the way artificial intelligence is being integrating into how controllers think and operate in poultry barns. Black is the national sales manage for SKOV

• Automatic adaption of ventilation to all climate conditions

• Closed production environment

• Controlling temperature, humidity, air velocity, and air quality

• Same climate all over the house during cold periods

• Using air velocity as a chill effect during hot periods

31290 Wheel Ave. Abbotsford B.C. V2T 6H1 604 746-5376 www.agprowest.ca

– a Danish-based, global ventilation company.

“By tracking what’s happened in the barn, our AI-based controllers are able to predict what will happen next and respond by starting up a heater before there is a dip in temperature, for example,” says Black. “This advanced thinking – or adaptive learning – takes some of the onus off the end user.”

Compared to the company’s nonAI system controllers that are more reactive and base control adjustments on what’s happened in the last cycle, the AI controllers anticipate adjustments needed to avoid over or under ventilating barns.

SKOV does a lot of retrofits and one of Black’s best recommendations to customers is upgrading controllers. “A modern controller is going to make the barn much more efficient. It’s the best investment to breath new life into an older barn,” says Black.

When it comes to new designs for barn ventilation, Black is seeing Canadian farms adopt more of what is happening in the southern U.S. – new builds that can handle higher summertime temperatures and more sustained high temperatures.

“Traditional ventilation in poultry barns was cross or side vent – with all the inlets on one side and all the fans on the other,” says Black. “Then tunnel ventilation improved the efficiency of airflow by moving it down the length of the barn and shrinking the cross-section area it needed to move through.”

Now, SKOV’s combination tunnel style blends the best of these two systems. There are inlets and fans on all sides of the barn, used at different times depending on the need to cool or warm the barn. “We want to place the air more precisely, balancing the heating and cooling needs of the birds,” says Black.

“Ventilation is always at the forefront and very important to producers because of the impact on bird health.”

Filtered Inlets for Biosecurity – Adding filtration systems to air inlets is becoming essential, especially in high-density poultry areas. Filters help remove dust and pathogens, reducing the risk of avian influenza and other diseases.

Variable Speed Fans – Direct drive fans with variable speeds offer better control over airflow while cutting down on maintenance and energy costs. Running multiple fans at lower speeds is more efficient than fewer fans at full speed.

AI-Driven Smart Controllers

– Advanced controllers with artificial intelligence anticipate ventilation needs, adjusting conditions proactively rather than reactively. This technology helps maintain optimal barn conditions while reducing energy waste.

Combination Tunnel Ventilation – A hybrid approach to barn airflow, combining traditional side and tunnel ventilation, improves temperature regulation. This design is effective in handling extreme temperature shifts.

Insulation and Pre-Treated Air – Better insulation and pre-treating incoming air with UV light or filters help regulate barn conditions efficiently, maintaining bird health and reducing costs.

The Poultry Industry Council (PIC) is a charity focused on creating relevant resources and events to support Ontario poultry farmers.

Did you attend the National Poultry Show? That’s one of our 30+ events! If you enjoyed it, check out what else we offer throughout the year!

March 19th, 2025 | Online | Scan to Learn More

Join us for a day of expert-led discussions on key industry topics. While broiler breeder-focused, all producers are welcome!

PIC Podcast & Educational Events – Stay informed with expert insights, industry trends, and best practices!

Networking & Community – Connecting farmers, veterinarians, and industry professionals

Email Updates – Get notified about events, poultry health alerts, & resources

Become a PIC Member – Get event discounts & be part of the voice shaping Ontario’s poultry industry!

Outbreak

numbers were

lower with the latest wave, but more tools are needed in the fight.

By Ronda Payne

Alot of knowledge from past years meant Canadian poultry farmers were prepared to face off against avian Influenza (AI) when outbreaks returned to farms in the fall of 2024. While they’ve been moderately successful in the fight, seeing lower numbers of infections than in some of the previous outbreaks, farmers still need more help navigating the future of the disease.

B.C. has been particularly hard hit for a number of unchangeable reasons, such as wild bird flight paths, weather patterns and farm proximity. So, new methods to combat infection and spread are needed and this requires more studies about the virus. Fortunately, B.C. isn’t alone in taking on the disease and past outbreaks have brought the country’s poultry industry together in sharing positive practices.

Winter came later to Southern B.C. this year but it’s the slowing of outbreaks that has Derek Janzen of Alderwest Poultry in Aldergrove, B.C. feeling optimistic. Janzen farms both layers and broilers, is on the board of directors for the B.C. Egg Marketing Board and has served on a number of other boards in the industry.

“It definitely has slowed,” he says of the rate of outbreaks in B.C. “I think we’re seeing some light here as we head towards the end of January.”

He personally knows the hardships his fellow producers face when they have a sick bird confirmed with AI.

“We were diagnosed at the beginning of December [2022]. We’d noticed that we had some abnormal mor-

Response times and improved biosecurity measures helped slow the spread of avian influenza during the latest wave of outbreaks.

tality and there had already been some other farms that had tested positive, so we kind of had an idea what it was. We did submit to our vet, and it was diagnosed as positive for HPAI,” he says. “We were pretty much devastated.”

He says accepting that the birds would be culled was one thing, but uncertainty around timing for the subsequent steps and getting approval to lay another flock was hard. Emotions run high and there are more questions than answers.

“It was the not knowing that was the hardest,” he says. There were no obvious answers for Janzen as to how the disease got in. There are no nearby water sources or neighbours who have poultry operations. It was a painful experience knowing he had done everything right from a biosecurity perspective but still got hit with AI.

Amanda Brittain, director communications and marketing with the B.C. Egg Marketing Board, says farmers have been following all biosecurity protocols in this “sixth wave” since 2022. There have been 80 infected premises in B.C. in the current wave and 71 of these have been in the Abbotsford/Chilliwack area.

Your local Georgia Poultry store is the place you count on for service and repairs. We feature GrowerSELECT® parts as cost-effective replacements for all types and brands of live production equipment. Stop by a store, shop online, or call

“We’ve had over one million layers destroyed,” from October 21 to January 10, she says. “Last year, it stopped around Christmas time and this year it continued, which is worrisome, but it’s much lower numbers.”

She says layers were hit particularly hard, but they don’t know why at this point.

According to the government of Canada’s AI update page, as of January 24, B.C. had 41 active premises and the next was Ontario at eight. B.C. had 198 previously released premises, Alberta had 85, Quebec 58 and other provinces had descending numbers from there.

The protocols of biosecurity and dealing with an outbreak haven’t changed. Once a bird is diagnosed with HPAI, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency takes the lead on the process, instituting a “very strict protocol,” according to Brittain. Birds are destroyed, the barns are cleaned then disinfected. Only then can approval of laying a new flock be granted.

Brittain feels the faster responses by farmers and organizations during this wave may have helped prevent spreading.

“All the agencies have learned from the past years,” she says. “Farmers are getting used to things and know what they need to do. It’s a horrible thing to get used to.”

Janzen agrees that the speed of response has improved since 2022, and this may be helping to keep numbers of infections down.

“The flocks, as soon as they’re diagnosed, are being euthanized and that’s preventing the spread of the virus,” he says. “Because every day the birds are in the barn, the virus is being exhausted out of the barn and it’s traveling.”

In B.C., the four poultry associations (B.C. Broiler Hatching Egg Producers Association, B.C. Chicken Grower’s Association, B.C. Egg Producers’ Association and B.C. Turkey Association) work well together in sharing information says Janzen.

“The commodities work really well together in coordinating efforts with the CFIA and also with the provincial government,” he says.

Brittain is the contact at the poultry emergency operation.

Red biosecurity measures remain in place in the region for all poultry farms in an effort to keep AI from getting into barns. All farms are on an “indoor order” meaning birds must stay indoors even if they are free range.

Some farms aren’t allowing egg truck drivers to get out of the vehicle so they load their own eggs into the truck. Others bleach entrances and may shower when entering the barn and shower again when leaving. Multiple footwear changes, clothing changes, banning non-essential people from going on site and more

measures were instituted several waves ago and are still the standard practice today.

When farmers are being so careful, the question remains as to how the disease is continuing to spread – albeit, slower than previously. The short answer is, no one knows for certain yet.

Studies are ongoing looking at whether AI can be transmitted or carried by things like rodents or insects or even dust. Brittain says CFIA will be working on studies about weather and wind patterns with outbreaks.

Part of the challenge is that AI can establish itself in a wide range of hosts, says Shayan Sharif, professor at Ontario Veterinary College at the University of Guelph.

“First and foremost, we know that this influenza virus has a really wide host range,” he says. “We’ve also learned that this virus can kill certain waterfowl that would, in the past, have been more resistant.”

The wide host range has led to infections in a number of mammals including marine mammals, arctic dwelling animals and dairy cows in California. There are justified fears of what could happen if AI were to infect cows in Canada.

“Cows can become infected, and they can share the virus through their milk,” Sharif says. “As early as the 50s, we knew that cattle could become infected with avian influenza virus, but we didn’t know how

Strict biosecurity measures, including multiple footwear changes, are essential to preventing the spread of avian influenza on poultry farms.

easily they could become infected. The reality is it was not on our radar at all. It was serendipitous that it was identified in the milk.”

While most cows recover from the virus, it’s still unknown to what extent they recover and whether their milk production returns to pre-infected levels after calving. If the disease becomes more virulent, it could kill cows, goats and other animals beyond poultry.

He advises that while AI is not making it into the human population readily, it is something that needs to be watched carefully.

“If it does gain that capacity, then it would become a pandemic or a pandemic capable virus,” he says. “We don’t want to see that happen.”

Goats can also catch the virus but so far sheep have shown resistance and it’s uncertain as to why. Dogs and cats are susceptible, he says. This leads to a closer point of contact to humans, but also a greater range of concern.

“If they can transmit the virus to humans, then we have a much more complicated situation,” Sharif says. “Sources of our food being taken out. We’d also have our companion animals that could be taken out. We could have a significant problem with transmission to humans. It’s still not finding its way through human populations, which is a good thing.”

He notes that the virus naturally changes as it progresses through a single animal. So, the virus present in an animal isn’t 100 per cent the same virus that infected the animal. However, he stresses that the backbone of AI is still the same.

“Viruses change all the time,” he says. “It hasn’t really made a significant leap. I don’t think we’ve seen a major change in the evolution of the virus. Mammals are not necessarily the preferred host of the virus.”

Each year, CABEF helps students to pursue rewarding agri-food careers through seven $2,500 scholarships. We’re looking for the future leaders who will help this industry meet tomorrow’s challenges.

Do you know someone who needs to fund their future in agri-food? Tell a student today.

Scholarship application deadline is April 30, 2025

Want to help support the next generation of agri-food leaders?

Become a “Champion of CABEF.” This program allows your organization to directly sponsor a deserving student. Contact CABEF at info@cabef.org.

This has to do with biological receptors. Those in the upper respiratory system in mammals are less compatible with the virus than the receptors of avians. But he does say the virus is highly unpredictable.

“This is not like COVID-19 that came out of nowhere,” Sharif says. “This virus has been around almost three-and-a-half years. Have we done enough to mitigate the concerns of emergence and transmission?”

He has great sympathy for B.C. producers and says he hopes research will deliver the solutions. Vaccination in France and China has been successful, but the decision rests with the CFIA.

“Understanding is only one part of it,” he says. “We have to do something. A preventative measure like vaccination should be on the agenda, in my view. But vaccination is just one part of it. It’s just the beginning of the journey.”

He thinks the focus should be put on B.C. and Alberta, then the rest of the country.

Wild waterfowl, particularly dabbling ducks like mallards, are the natural host, says Brian Stevens, wildlife pathologist with the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative. They are the main source of the virus in North America.

“They’re not really susceptible. They’re the ones that are going to have different strains of it,” Stevens says. “They’re the ones that are going to carry it and not necessarily die from it. I’ve seen 100 times more Canada geese die from it than I’ve seen Mallard ducks from it.”

Geese and ducks spread the disease to other waterfowl and into the environment.

“They could potentially spread it on their body, it can be spread via their excretions,” he says. “There are a couple of different

ways it could be put into the environment.”

Fortunately, where there are large herds of wild animals, Stevens isn’t seeing a large waterfowl population spreading the disease.

“We’ve actually been testing white tail deer in Ontario in the last few months and we’ve not detected it… and I don’t suspect we will,” he says.

While we see the biggest numbers of infections during the spring and fall migrations, Stevens says there are some changes in what experts have seen in wildlife versus what they expected.

“During the winter, when we get that really cold weather, we tend to get outbreaks a week or two after it hits -10 or -15 or -20,” he says. “I think that’s because we have a resident population that doesn’t migrate, then congregates. It might be related to a cold snap. That’s something we’re looking at.”

Additionally, despite common beliefs, the virus thrives in cold weather rather than dying.

“Freezing doesn’t kill it. It does fine at negative 20,” he says. “If you heat them up it will die much quicker.”

Stevens notes the need to keep up with biosecurity measures as the main tool to fight AI.

“Researchers are trying to figure out if it’s biosecurity issues or rodents or insects or songbirds that are the issue,” Stevens says. “Then we can start focusing on those areas where it’s getting in but figuring it out is going to be a tough task.”

While the science is continuing to evolve and studies are done, it’s important that the public hear the correct information from the industry and individual farmers.

“We are starting to see some social [media] posts about food safety,” says Brittain. “No food from an infected bird will be at a grocery store.”

She says some online reports implied that egg shortages were due to infected eggs being found and pulled from shelves. Instead, it was because of the reduced number of layers and the typical run on eggs seen during the holiday season.

Do you know an influential and innovative woman in Canadian agriculture? We’re looking for six women making a difference in the industry. This includes women in:

• Farm ownership and operations

• Ag advocacy and policy

• Research and education

• Agronomy

• Business development

• … and more!

By Jonathan Giret

The struggle to balance cost cutting with improved onfarm efficiency is taking on added urgency these days. Commodity prices, cost of production concerns – both with crops and birds – capital expenses for equipment inside the barn and food safety protocols are enough to keep any poultry producer hopping.

But now there are questions surrounding green energy systems and determining the best approach for on-farm efficiency. For me, these conditions apply whether I’m referring to a livestock producer or one who’s focused on crops.

A quick overview of my farm: I purchased my first farm in 2014, entered the broiler industry in 2016, and now own 250 acres. I attempt to operate as if I was advising another farmer on how to get started in the industry and have focused my efforts from the early years to expanding my acreage. Now, with land prices, I have

shifted investments towards my poultry production. The two things I identified as a fit for me were solar panels for net metering and heat exchangers.

One of the reasons I like solar net metering is the theory that it shouldn’t create any additional work for me as a farmer once they are up. The current net metering offer in Ontario is to create your own hydro, push it back to the grid, and if you create more than you use, your bill will be minimized to the portions of the bill not eligible for the offset. My last bill was less than $100 and would have been more than $600 were it not for net metering.

Without grants or tax credits, there is still a payback for pursuing solar, which is better than most of the investments in the farming community.

One thing to note would be the connection

delays. Hydro One took six months after my solar was fully installed to allow us to start sending energy back to the grid. So, the lesson here is to plan, be patient and talk through the timelines before installing the panels.

You need to consider insurance liabilities, as well. My insurance company had no issues with putting solar on the roof, but if it is a concern with your insurer, consider ground-mount options. For any producer looking at building a barn, I suggest making sure their trusses are rated for a solar load. It’s an inexpensive addition when you’re building a barn.

I talked to many farmers who have solar and found it was about half and half to those who prefer solar on the roof, or those who were concerned about structural impacts of the solar panels on the roof. For me, the deciding factor was placement: I didn’t have any area on the farm that a ground mount would fit, not be in the middle of a field, and not have the poten-

tial to be in the way for future development in the next 50 years.

On my farm – with one barn and one house – the pay back without incentives was roughly 11 years, with an initial price of $130,000. I needed a 55-kilowatt (kW) system, but built the infrastructure for a 75kW system that will allow expansion up to 150 kW in the future. Crescent Ridge Services out of Tavistock, Ont., handled all aspects of the solar installation.

There is an Input Tax Credit (ITC) for 30 per cent, which incorporated farms are eligible to pursue. Unfortunately – for me – due to some accounting communication errors, I missed taking advantage of that opportunity for my farm. The good news is that by leveraging grants, I was still able to get the pay back down to about six years.

If you’re researching solar, be conscious to only listen to those that have experience in this realm. Many farmers without solar panels relayed concerns on longevity and significant costs for maintenance. I made the effort to engage with multiple farmers who participated in the early micro fit programs and have had their systems for

“For any producer looking at building a barn, I would suggest making sure their trusses are rated for a solar load.”

more than 10 years. The response was consistent that maintenance was minimal, the systems operated well, and degradation of the panels was not a concern.

On a personal note, the reason I love this system is that as I expand into the future, the question has shifted from “What I can do to reduce hydro use?”, to “What can I invest in that will show a return, and leverage extra hydro capacity?” It’s enabled me to look at energy usage in a different way and is an intriguing prospect that holds many opportunities for future development.

Heat exchangers also seemed like a great investment. Since my barn is a single cross, it has bothered me since construction that I’m bringing air in, heating it and then 60 feet across the barn, exhausting it out the side. A heat exchanger makes sense and if I can heat the barn more efficiently, I can ventilate more to ensure carbon dioxide (CO2), ammonia and humidity are always well within BMP targets.

When I constructed the barn, I was pitched on a large Vencomatic unit and given the cost compared to the

barn, it seemed like a second-generation poultry producer investment. The ESA units cost me roughly $50,000 for three and that seemed a reasonable investment with a manageable return.

I have an 18,000-square-foot barn and the dealer suggested I have five units installed. I went with three as a test, thinking that for the first four weeks of winter ventilation I should be fine with three. Typically, the last week to 10 days I am adding another fan, but this is also when I’m least concerned about supplementing heat in the barn.

The heat exchanger unit I chose to go with was the ESA-3000. My intent was to do an in-depth review of the return on investment (ROI) on my barn to validate the numbers from the company literature. Unfortunately, I recently learned that my insulation has settled to about r20 in the ceiling and will need to be topped up before next winter; on an eight-year-old barn that’s a painful pill to swallow. But such is life, and my ROI calculations will be limited to one winter of accurate numbers.

As I write this, it is -6°C in West Lorne, Ont., the barn is set to 28.6°C, and the heat exchanger is bringing in

fresh air at 15.3°C, for 62 per cent efficiency. Not far off ESA’s claim of reducing heating costs by up to 70 per cent. One thing worth noting is that it does take quite a bit of time to wash the heat exchanger cores. The units do come equipped with an auto flush system, but in my experience, it does take about an hour per unit to wash them well in between flocks.

Turkey Signals follows the cycle on a commercial turkey farm. The book describes how turkey focused management will improve production and welfare of the turkeys and thus the turkey farmer’s financial results.

Turkey Signals is a practical guide that shows you how to pick up the signals given by your animals at an early stage, how to interpret them and what action to take. This is a book with over 850 photographs and illustrations; a musthave for anyone involved in turkey farming.

Location

Wellesley, Ont.

Sector Broilers

The business

Hidden Spring Acres is a family-run broiler farm near Wellesley, Ont. Founded six years ago, it’s managed by Jane Lindner, her daughter Emily, and Emily’s husband Patrick. Their focus is broiler production, recently enhanced by a new barn.

The need

The decision to build stemmed from aging infrastructure. The farm’s two-story barns had steep driveways and outdated equipment. “The old barns were no longer practical,” Jane says.

The barn

The new, single-story barn, a 65 by 500-foot structure, was designed with efficiency and sustainability in mind. One of the standout additions is the Poultry Hawk Premium Trolley, a remotecontrolled trolley system that moves through the chicken house to transport poultry supplies and remove dead stock. Emily highlights, “As a seven-month pregnant farmer, having the Poultry Hawk do the heavy lifting has been a gamechanger.” The barn also features advanced ventilation and a SKOV system, which regulates air quality more effectively than the previous setup. Additionally, the new feed system includes sensors that trigger augers to keep feed lines consistently full, ensuring birds are always well-fed. The reduced labor and improved workflow are already evident, with Emily estimating the barn’s design has cut cleaning time by up to 10 hours per crop. Poultry

The National Environmental Sustainability and Technology Tool is a first-of-its-kind system that egg farmers can use to track, assess and benchmark the environmental impact of their farm.

How the tool can help you

You can use the tool to:

Understand the environmental impact of your farm

Compare your results to other egg farms

Improve your operations with tailored recommendations

Access the latest on-farm sustainability resources for egg farmers

How to access the tool

By using the tool, you’re supporting the broader movement of egg farmers who are collaborating and innovating for a more sustainable future.

All you need to get started is your Farm Registration ID!

Introducing Poulvac® Procerta™ HVT-IBD. Timing is everything in a poultry operation, and Zoetis created its newest vector vaccine to put time back on your side. Backed by the latest science resulting in excellent overall protection, studies found that Poulvac Procerta HVT-IBD protected chickens fast against classic IBD and AL-2.1-3 It’s a quick way to full protection from infectious bursal disease. Contact your Zoetis representative or visit PoulvacProcerta.com.