From the Editor

by Brett Ruffell

by Brett Ruffell

After years of avian influenza (AI) outbreaks that devastated flocks and communities, Canadian poultry producers may finally be catching their breath. Infection numbers are down. Anxiety has eased. And much of that hardearned progress is thanks to the rigorous biosecurity protocols producers have embraced, adapted and improved.

But this is no time for complacency.

“Everyone – from our frontline workers to our suppliers – needs to treat AI risk as an everyday reality, not just a crisis event.”

That’s why our September issue dives deep into the evolving world of biosecurity – from barn-level upgrades to new tech solutions and even how our landscapes shape risk. Across the country, producers and researchers are asking important questions.

How do we manage threats that aren’t always visible? Can predictive tools replace reactive policies? And who’s responsible for planning the next layer of defence?

Our cover story, “Mapping avian

threats” (pg. 10), explores how scientists are studying wild bird activity, compost piles and surrounding land use to better understand local transmission risk.

The researchers’ findings suggest that what happens within 500 metres of your barn may matter more than any factor farther away – and that small changes can make a big difference.

In “Too close for comfort?” (pg. 14), biosecurity experts argue that Canada’s lack of barn spacing regulations could leave us vulnerable to future outbreaks.

“We’re not planning ahead. We’re always reacting,” says veterinary professor Jean-Pierre Vaillancourt, highlighting a regulatory blind spot that still hasn’t been addressed since a major Ontario court case more than a decade ago.

Meanwhile, features like “The future of biosecurity is already here” (pg. 24) and “Duck no!” (pg. 26) showcase what’s working. From UVsensor hybrids to secure egg collection rooms, producers are proving that innovation and consistency are the real game-changers.

This issue is a reminder: the fight against AI isn’t over – it’s just changed.

And the best time to strengthen our defences is now, before the next storm hits.

canadianpoultrymag.com

Reader Service

Print and digital subscription inquiries or changes, please contact Angelita Potal, Customer Service Rep.

Tel: (416) 510-5113

Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Editor Brett Ruffell bruffell@annexbusinessmedia.com 226-971-2133

Brand Sales Manager

Ross Anderson randerson@annexbusinessmedia.com Cell: 289-925-7565

Account Coordinator Julie Montgomery jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5163

Media Designer Lisa Zambri

Group Publisher Michelle Bertholet mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Manager

Anita Madden amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5183

CEO Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40065710

Printed in Canada ISSN 1703-2911

Subscription Rates

Canada - Single-copy $10.00

Canada – 1 Year $33.15

Canada – 2 years $56.61

Canada – 3 years $78.54 (plus applicable taxes)

USA – 1 Year $93.33 CDN

Foreign – 1 Year $105.57 CDN

GST - #867172652RT0001

Occasionally, Canadian Poultry Magazine will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer

privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 800-668-2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission. ©2025Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions. All advertising is subject to the publisher’s approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertised. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

The LUBING OptiCOOL evaporative cooling system with plastic pad is easy to clean, keeps my broilers cool, and allows my ventilation system to run more efficiently. Best thing is, my birds are bigger!

Randall

Ruff - Ruff Acres

EFFICIENT AIR-FLOW

EFFECTIVE AND CONSISTENT COOLING

Keep your barn climate controlled and your flock cool and healthy with the LUBING OptiCOOL plastic evaporative cooling pad system—designed for easy cleaning and long-lasting performance.

Glass-Pac Canada

St. Jacobs, Ontario

Tel: (519) 664-3811

Fax: (519) 664-3003

Carstairs, Alberta

Tel: (403) 337-3767

Fax: (403) 337-3590

WATCH THIS VIDEO TO LEARN

Les Equipments Avipor Cowansville, Quebec

Tel: (450) 263-6222

Fax: (450) 263-9021

Specht-Canada Inc.

Stony Plain, Alberta

Tel: (780) 963-4795

Fax: (780) 963-5034

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith is considering pulling the province out of Canada’s national supply management system for dairy, poultry, and eggs, citing concerns over fairness. At a recent town hall, she noted Alberta holds less than nine per cent of the national milk quota despite making up over 11 per cent of the population. Smith said the idea of creating a provincial quota system or moving to a market-based model deserves further discussion with producers.

Canada’s poultry industry is backing a joint letter from more than two dozen agriculture organizations urging Prime Minister Mark Carney to make agriculture a national priority. The letter calls for increased investment, regulatory reform, modern infrastructure, and stronger risk management tools to unlock the sector’s full economic potential. With national poultry boards among the signatories, the industry is highlighting the urgent need for federal leadership to support food security, sustainability, and growth.

Ontario chicken farmers donated 350 kilograms of locally raised chicken to the Guelph Food Bank, providing over 3,000 meals to individuals and families in need. The donation was part of the CFO Cares: Farmers to Food Banks program, which has delivered more than 10 million meals to food banks since 2015.

A sample ad from CFC’s “Chicken. Eat it Anytime.” campaign encourages Canadians to choose chicken as a high-protein snack for busy, on-the-go lifestyles.

Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC) has launched a new national campaign encouraging Canadians to rethink how and when they eat chicken.

Titled Chicken. Eat it Anytime., the campaign presents chicken as a go-to protein snack for busy, health-conscious consumers.

is the percentage of consumers who want to eat more protein, according to a study by Chicken Farmers of Canada.

Aimed especially at Gen Z and Millennials, who often reach for processed bars and powders to meet their protein needs, the marketing campaign positions Canadian-raised chicken as a nutritious and satisfying snack alternative.

“The idea started with a simple question: why not chicken?” reveals Michael Laliberté, CEO of CFC. “It’s time to think beyond traditional meals and recognize chicken as the go-to snack for energy, taste, and trust in every bite.”

Chicken offers 23 grams or more of protein per 100-gram serving, depending on the cut, and the campaign is grounded in recent insights that show 71 per cent of consumers want to eat more protein. Protein has become the top nutritional priority for many Canadians, influencing the choices they make throughout the day.

The campaign features a series of digital ads, videos, and social media content that showcase convenient ways to enjoy chicken – whether in wraps, skewers, leftovers, or bites. The messaging is designed to resonate with modern consumers who are looking for whole, real food options that align with their active routines and dietary goals. Canadians are encouraged to explore snack-friendly recipes at chicken.ca.

latest poultry-related news, stories, blogs and analysis from across Canada at:

More than 1,200 poultry scientists, students, and industry professionals gathered in Raleigh, North Carolina for the Poultry Science Association’s (PSA) 2025 Annual Meeting.

Held over four days, the event featured nearly 600 abstracts presented through 398 oral talks and 128 posters, along with 70 expert-led presentations across 12 symposia. Key topics included avian influenza, immunity, smart farming, reproduction, genetics, and precision nutrition.

This year’s robust program, led by Laura Ellestad of the University of Georgia, kicked off each oral section with invited speakers who provided essential context and big-picture insights.

For the first time, the conference introduced an electronic poster session, giving attendees a more interactive way to explore new research and engage with presenters.

The meeting also included PSA’s signature Student Abstract Competition, dynamic workshops,

and a full slate of networking and social events. One highlight was the PSA BBQ at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, where participants enjoyed comfort food alongside hands-on museum exhibits.

The Association honoured numerous professionals at its annual awards celebration, including new Fellows Kenneth Koelkebeck and Randy Mitchell. Several early-career researchers were also recognized, including Indu Upadhyaya, Ariel Bergeron, and Andi Asnayanti.

The conference closed with the inaugural Presidential Symposium, chaired by retiring PSA president Martin Zuidhof (University of Alberta), who focused on innovations in precision nutrition and data- driven poultry production. Doug Korver, also of the University of Alberta, has been named the new PSA president.

Planning is already underway for the 2026 Annual Meeting in Toronto.

Doug Korver (left) steps into the role of PSA president, succeeding Martin Zuidhof, who chaired the 2025 Presidential Symposium.

SEPTEMBER

Sept. 1, 2025

National Chicken Month Kickoff chickenfarmers.ca

Sept. 2, 9, 16, 23, 30, 2025 Canadian Poultry Broiler School Webinar Series canadianpoultrymag.com

Sept. 3, 2025

PIC’S Golf Day, Baden, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

Sept. 9-11, 2025

Canada’s Outdoor Farm Show Woodstock, Ont. outdoorfarmshow.com

Sept. 9-11, 2025

Shell Egg Academy, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ia. shelleggacademy.org

Sept. 22, 2025

1,200 is the number of poultry scientists, students, and industry professionals who gathered for the PSA’s 2025 Annual Meeting.

PIC’S Science in the Pub Guelph, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

OCTOBER

Oct. 1-3, 2025

PSIW 2025, Banff, Alta. poultryworkshop.com

Oct. 23, 2025

PIC’S AGM, Hybrid Virtual and In-Person, Elora, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

NOVEMBER

Nov. 12, 2025

PIC’S Producer Update –All Breed, Virtual poultryindustrycouncil.ca

Nov. 20-21, 2025

PIC’S Innovation Conference Niagara Falls, Ont. poultryindustrycouncil.ca

By Dr. Gigi Lin

Dr. Gigi Lin is a board-certified poultry veterinarian. She provides diagnostic, research, consultation, continuing education, and field services to all levels of the poultry industry in Western Canada. In this new column, she will help producers understand and prevent condemnations.

In the last column, I talked about the risk factors of airsacculitis in broilers and briefly touched on the role that infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) plays in damaging the respiratory tract and affecting broiler performance. In this issue, I want to take a deeper dive into IBV, one of the most common and contagious viruses we face, and explore how to minimize its impact through biosecurity, surveillance, optimal brooding, and vaccination programs.

What is IBV and why does it matter?

IBV is an avian coronavirus that primarily targets the upper respiratory tract of chickens. Depending on the strain, it can also affect the kidneys or reproductive system. But regardless of where the damage ends up, IBV typically enters the bird through the lining of the respiratory tract. This matters because any damage to the upper air way – such as the nasal passages, sinuses, or trachea –makes birds more susceptible to infection.

In broilers, IBV does not always cause obvious signs like coughing or sneezing. In some cases, you might not notice clear respiratory signs at all. Instead, you may see poor uniformity, slower weight gain, or increased mortality from secondary bacterial infection like E. coli.These birds may later show up at processing with airsacculitis, septicemia, or underweights, leading to condemnation.

How does a broiler flock pick up IBV?

The virus is shed in respiratory secretions and feces. Infected birds release the virus when they cough, sneeze, breathe or defecate, contaminating the surrounding air and dust. Birds can become infected by inhaling aerosols, ingesting contaminated feed or water, or through contact with contaminated equipment. Infected broilers can shed virus for several weeks.

IBV can linger in dust, litter, and equipment and may survive for days to weeks, especially when protected by organic matter. If downtime between flocks is too short or cleaning isn’t thorough, the virus can be

reintroduced to the next flock. For the same reasons, multi-age sites that are not all-in-all-out carry a high risk.

IBV is highly contagious and can spread through the air, especially via dust and droplets. In high- density poultry regions, airborne spread from nearby farms is a real risk. The virus can also be carried between farms on equipment, vehicles, and personnel.

How do you know a flock has IBV?

This is where it gets tricky. As mentioned, not all birds with IBV show clear clinical signs. The severity of disease and how the bird responds depends on

many factors, including the strain of the virus, age of birds, immune status, the presence of environmental stressors, and concurrent diseases.

The first indication might be birds lagging slightly behind in weight. You might also notice poor uniformity, mild respiratory noises, or, in cases with secondar y bacterial infections, facial swelling and increased mortality.

To complicate things further, the signs of IBV can resemble those caused by other conditions, such as ammonia irritation, Mycoplasma gallisepticum, or even mild infectious laryngotracheitis. This is why early p ost-mortems and regular monitoring are so important. Work with your veterinarian to confirm the diagnosis.

As discussed in the last issue, IBV challenge can be detected through a blood test, which remains an inexpensive and pr actical surveillance tool. However, blood test results should always be interpreted alongside flock history and clinical data. A positive test does not always mean the virus is causing health issues, for two main reasons: 1) a recent vaccine can trigger a positive result; 2) a positive test simply indicates exposure, not necessarily a direct connection to clinical disease.

So how do we prevent it?

1. Biosecurity – the first line of defense: IBV is sensitive to disinfectants such as quaternary ammo - PHOTO: ALLTECH

nium compounds and glutaraldehyde. It is relatively easy to kill with proper chemical use and adequate contact time. However, the biggest challenge is organic matter. Dust and manure can protect the virus from disinfectants and even help it spread. Removing as much manure and dander as possible after ship-out is essential before cleaning and disinfection. Allowing an extended downtime period, when possible, also helps.

Producers in high-density areas should pay extra attention to ventilation and barn layout. Because IBV can travel in the air via aerosols and particulates, airflow patterns matter – especially during bird movements, m anure spreading, or wind shifts. Installing landscape fabric or other physical barriers near air inlets may help reduce exposure to airborne particles.

Basic farm and barn entry protocols are also crucial. Reinforcing practices such as vehicle disinfection stations and Danish entry systems can significantly reduce the risk of virus introduction. Visitors

should always follow strict biosecurity measures.

2. Vaccination programs: In IBV-endemic areas, broilers typically receive a spray vaccine at the hatchery. This early exposure is valuable because it gives the chick’s immune system a chance to recognize the virus and build early protection. Hatchery spray vaccination also allows for more uniform application, although it is important to avoid soaking the chicks which can lead to chilling.

In regions with higher IBV pressure or during certain seasons, field boosters may be added during the production cycle via coarse spray or drinking water. Always consult with your veterinarian when designing a vaccine program. Selecting the right strains, timing, and application method should be based on a strong understanding of local viral challenges thr ough ongoing surveillance. This is not a one-size-fitall decision, and programs may need to be adjusted throughout the year.

3.Brooding and bird immunity:

• IBV is a common, contagious virus that enters through the respiratory tract and can quietly affect performance, uniformity, and condemnation rates.

• Not all IBV infections are obvious. Look for subtle signs early and monitor flock proactively.

• Prevention starts with biosecurity: minimize dust, manage airflow, and clean and disinfect thoroughly.

• Hatchery vaccination provides early protection. Discuss with your veterinary team whether to modify vaccine programs in high-challenge locations or during high-risk seasons.

• Optimal brooding practices strengthen bird resilience and reduce the chance of clinical disease, even when birds are exposed.

Even if birds are exposed to IBV, how they respond depends largely on their immune status and brooding conditions. Chicks with strong immune systems are more likely to control the virus before complications develop.

• Poor air quality: High ammonia levels, poor ventilation, or dusty barns can damage the cilia in the airways. Cilia are tiny hair-like structures that play a critical role in clearing inhaled particles and pathogens. Once they are impaired, vir uses like IBV can more easily attach to the respiratory lining.

• Envir onmental stressors & concurrent infections: Other stressors such as poor litter management, suboptimal nutrition, and high stocking density can weaken birds’ immune response. Coinfection with pathogens like Mycoplasma gallisepticum, E. coli, or avian metapneumovirus can further worsen disease outcomes

• Chilling: Wet or cold chicks during spray application, transportation, or poor brooder setup are more vulnerable. Chilling lowers body temperature and weakens immune function. In my experience, spikes of IBV cases in broilers are more common during seasonal changes, especially in fall and winter, when sudden night time temperature drops are frequent.

Canadian scientists trace how wildlife and farm practices influence HPAI outbreaks on turkey farms.

By Lilian Schaer

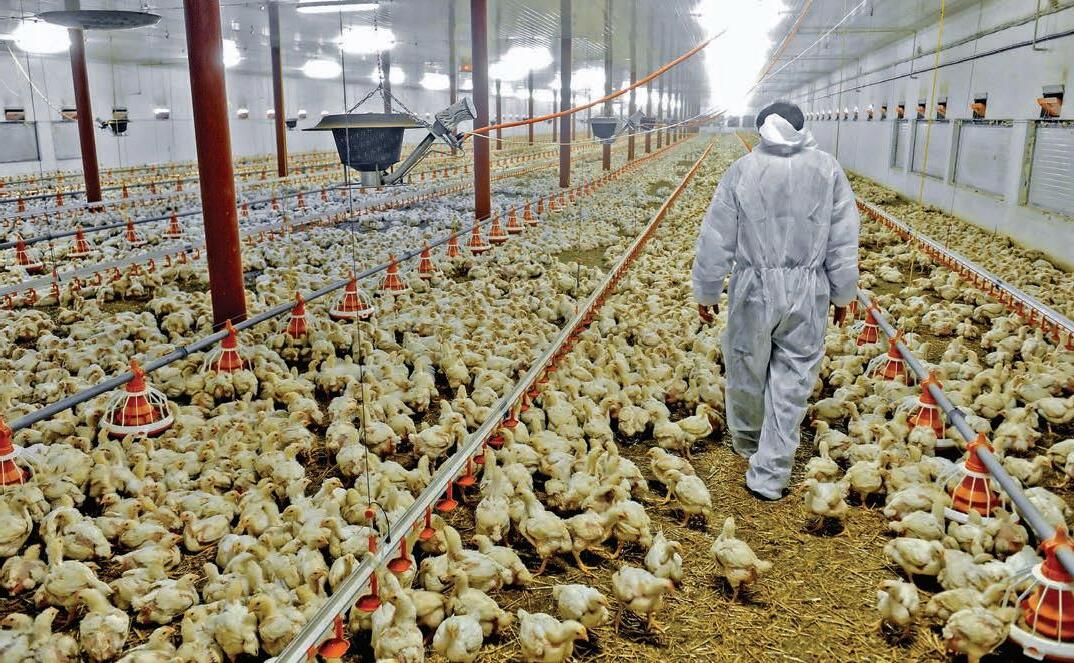

Amajor Canadian research initiative is giving turk ey producers new insights into how highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) spreads – and what they can do to better protect their farms without harming the environment.

Scientists from Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) are leading this three-pronged research project to identify how HPAI is spreading, what role wildlife plays in this spread, and what steps producers can take to reduce on-farm risk.

Since 2022, HPAI outbreaks have had a devastating impact not only on domestic poultry but also on wild bird populations. And for turkey producers, who tend to be overrepresented in infection numbers, that has meant heightened concern and need for clearer guidance on how to minimize risk.

Understanding the environmental piece Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) research scientist Dr. Jennifer

Provencher is co-leading a team from her agency and Carleton University, including students, studying how biodiversity and landscape features may be contributing to HPAI outbreaks. Until recently, most biosecurity measures focused on human activity and farm-to-farm interactions. But with HPAI now entrenched in wild bird populations, Provencher says it’s time to expand the biosecurity lens.

“What’s changed is the scale and impact of this virus on wild birds,” she says. “We’re seeing wild and migratory bird mortality events across Canada – dead seabirds on beaches, dead geese in the Prairies – which is why Environment and Climate Change Canada are now involved with a whole response team to look at how HPAI transmits across the landscape.”

In the past, Avian Influenza transmission into poultry flocks has been linked to wetlands or and the presence of wild bird populations – such as barn swallows for example, but Provencher notes there’s no real evidence to suggest these links actually exist or are behind onfarm infections.

The team has been working with 30 to 40 Ontario farms –

some infected and some not – to examine which wildlife species are visiting farms and how they might be contributing to virus spread. Using song meters and trail cameras, they’ve captured footage of coyotes, turkey vultures, and red-tailed hawks scavenging deadstock piles and compost areas.

Their findings could prompt a rethink on how producers manage compost piles and disposal areas, for example.

“ We’ve seen farms surrounded by wetlands and forests that haven’t had a single case, and others in less diverse landscapes that have been hit,” says Provencher. “It’s not just about

how many wild birds are around – it’s also about who else is around and what they’re doing in the landscape that could be behind transmission.”

Importantly, early results of data analysis from southern Ontario and Quebec suggest that landscape-level risk is mostly local. Variables at the 500-metre level (like adjacent crop type or tree cover) were more influential than those at two or 10 kilometres. That means farmers have more control than they may think when it comes to reducing risk.

While Provencher is examining

the broader environment, veterinary epidemiologist Dr. Manon Racicot from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is zooming in on farmlevel biosecurity and what can be learned from farms who’ve had HPAI infections.

Working with Dr. JP Vaillancourt at Université de Montréal, Racicot launched a case-control study in Quebec – later expanded to Ontario by Al Dam of the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agri-Business – to compare biosecurity practices on infected versus non-infected turkey farms. The goal: identify practical, evidence-based risk factors.

Key findings so far include several on-farm practices that appear to increase vulnerability. One is unprotected bedding storage. Farms that stored

bedding outside or with exposure to wild birds were more likely to be infected.

Even the process of bringing clean bedding into the barn matters – tractor wheels can unknowingly carry the virus inside, for example.

Another concern is split shipments to processing. When birds are shipped in multiple loads over several days, the risk of exposure increases – especially during migration season.

B iosecurity breaches during catching are potential transmission windows for birds remaining in the barn.

Outdoor bird movement has also emerged as a factor. Farms that moved poults between barns using outdoor equipment were more exposed. Even without direct bird contact, equipment moving between barns can carry contamination.

The well-being of your animals is paramount, but nuisance pests can negatively impact your livestock. That’s why Envu has the solutions to help empower you and stop the spread of diseases, reduce stress on your animals, and ensure your animals are in a healthier and happier environment.

Finally, practices around deadstock and composting play a role. Ontario farms, which primarily use on-site composting instead of rendering services, may be inadvertently attracting scavengers that carry HPAI.

In contrast, Quebec farms using rendering trucks collecting deadstock away from

barns and closer to the road saw reduced risk.

“We’re not saying you have to change everything overnight,” says Racicot. “But small changes – like moving your compost away from the barn, composting in a closed shed or improving entryway design – can make a difference in protecting your flock against HPAI.”

Although full analysis and final recommendations won’t be ready until this fall, both Provencher and Racicot say early findings already offer useful guidance that farmers can implement.

One key takeaway is to reinforce “double bubble” biosecurity. That means keeping strict farm-to-farm protocols but also paying attention to wildlife access to barns and compost or other vulnerable areas.

Another suggestion is to think local. Producers should focus mitigation efforts within 500 metres of their barns and adjust practices based on the actual species showing up on farms rather than just the presence of wetland or forest nearby.

Securing bedding and deadstock is also important. Farmers should protect storage areas from wild birds and manage dead piles in a way that avoids attracting scavengers.

Finally, producers are encouraged to rethink infrastructure.

If upgrading barns or entryways, they should design with biosecurity in mind. Barriers can make it easier to stick to hygiene protocols.

A major goal this fall will be to bring all the data – biodiversity, biosecurity, and farm design – into a single workshop to create practical, science-based recommendations.

“We’re going to bring together diverse experts who look at things in different ways and see what that tells us, and how we

Top risks identified:

• Split processing loads: Avoid multi-day shipping whenever possible. 90 per cent of farms in the control group were shipping in a single step, compared to only 65 per cent of infected farms.

• Unprotected bedding and compost piles: Keep unused bedding supplies dry and inaccessible to wild birds and manage deadstock to reduce visits from scavengers. Coyotes, turkey vultures, and red-tailed hawks frequently visit compost piles.

Sometimes it’s not what you think:

• Some of the most biodiverse farms studied had no infections – showing that risk depends on presence of specific wildlife species, not just the general presence of wildlife.

How you can act:

• Improve compost and deadstock area security.

• Rethink barn entryways for better biosecurity compliance.

• Focus risk reduction within 500 m of barns.

can make evidence-informed decisions that will work for both farms and the environment,”

Provencher says.

This research is funded by a broad coalition of organizations, including Canadian Food Inspection Agency; Environment

and Climate Change Canada; Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness; Université de Montréal; Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation du Québec; University of Guelph; and other provincial and national partners.

6'x40' Continuous Composter—Capacity of 1,450 lbs per day.

Manufactured in Canada. The 6' x 40' model comes equipped with a hydraulic drive system, ensuring a soft start. A remote control for easy opening/closing of the 9ft wide loading door. The insulated drum reduces heat loss, ensuring the composting process is successful to increase the bio-security on your farm. Omnivore composting is easy to control and adjust, resulting in a faster and more consistent end product.

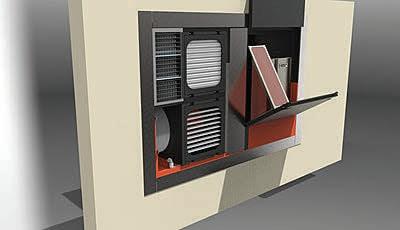

is installed flush with the inside of the barn wall.

is installed flush with the inside of the barn wall.

You don’t need to rebuild to reap the rewards of energy efficiency. With the ESA-3000 Heat Recovery System, retrofitting your current barn setup is easier—and smarter—than ever. The ESA-3000 integrates seamlessly with your existing infrastructure, transforming waste heat from motors, heating systems, and the animals into usable thermal energy that reduces your heating costs and boosts year-round barn performance.

As avian flu outbreaks rise, experts warn that the lack of barn spacing rules in Canada could turn isolated cases into regional crises.

In 2012, a court case in Ontario exposed a critical blind spot in Canada’s approach to managing disease risk in poultry production. A breeder operation was slated for construction just 800 metres from a farm housing great grandparent (GGP) stock under contract with Hybrid Turkeys.

The GGP producer raised concerns, citing the farm’s uphill location and prevailing winds. He even offered alternative land five kilometres away, but the neighbouring farm refused to relocate. Jean-Pierre Vaillancourt, professor at the University of Montreal, testified in the case. “I predicted that they would have high-path AI there in a few years,” he says. That’s exactly what happened. The breeder farm was the first to report infection, followed by the nearby GGP facility.

Over a decade later, with outbreaks

By Melanie Epp

increasingly frequent and complex, Canada still has no regulations governing how close poultry barns can be built. Scientists warn that while most avian influenza cases originate from wild birds, barn proximity could heighten the risk of secondar y spread, turning isolated outbreaks into wider regional crises.

Around the world, scientists have debated how physical distance between poultry farms contributes to disease prevention, particularly in the context of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). While most Canadian outbreaks have been traced to introductions from wild birds, experts agree that under certain conditions, the virus can move between farms. The question is how often, and by what means.

According to Vaillancourt, approximately

85 per cent of avian influenza cases in Canada are due to wild bird introductions, likely from bird feces being tracked into the barn on dirty boots. The remaining 15 per cent could be from lateral transmission, he said. That minority matters, especially in regions where farms are closely spaced and where time and distance cannot act as buffers.

The science behind lateral spread points to a range of possible vectors, including dust, feathers and aerosols, which can be carried by wind, he said. Rodents and insects such as flies can travel between barns, and human-mediated risks remain a constant.

However, quantifying airborne risk is a difficult task. During the major H7N7 outbreak in 2003 that affected 255 flocks and led to the culling of 30 million birds in the Netherlands, Dutch epidemiologist

Armin Elbers said there were indications that farm proximity may have played a role in disease transmission between closely situated farms. Many farmers certainly believed this to be the case.

“There is a definite tendency of poultry farmers to blame airborne transmission of diseases,” says Elbers, who pointed to biosecurity breaches as one among other possible causes. Farms situated in close proximity are more likely to see more visiting n eighbours, he said. In some cases, virus may be passed on by family members who farm nearby and share equipment.

Elbers also wanted to know the role of airborne transfer of contaminated fecal droppings of wild birds during outbreaks, so he conducted a study to evaluate small particle samples taken from ventilation system air inlets.

“We did a risk analysis,” he says. “It indicated that the daily probability of infection of a single poultry farm via aerosolization of contaminated feces from wild waterfowl is extremely low.”

Today, Elbers said farm-to-farm transmission is rare in the Netherlands– even in high density areas. Farmers learned the importance of strong biosecurity in 2003. They also learned about the importance of clear and quick communication. The Dutch have adopted a system they call ‘bucket sampling’ whereby farms in densely populated regions within a one-kilometre radius of an infected farm sample and test dead poultr y for avian influenza on these still uninfected farms. With that, proactive culling is no longer a first response in densely populated regions.

Elbers doesn’t consider proximity to farms the main factor in introduction of bird flu on poultr y farms in the Netherlands, but proximity to risk factors. It could be a neighbour borrowing equipment, or it could be proximity to waterways and grasslands that is an attractant for wild waterfowl. On this last front, researchers have mapped out high risk areas in The Netherlands, most of them in coastal regions.

“Complying to biosecurity measures is an important way to keep pathogens from entering a farm, but it’s also the most difficult to do, to consistently comply with every day,” he says. “It has to become a way of life for the farmer – and that’s very difficult.”

Canada’s regulatory blind spot Despite mounting biosecurity pressures, Canada has no national rules governing how far poultry barns should be spaced to reduce disease risk. Instead, siting decisions fall under a patchwork of municipal and provincial policies, most of which focus on odour, manure management or environmental buffers, not pathogen control.

According to Manon Racicot, Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) veterinarian and epidemiologist, barn proximity doesn’t fall under CFIA’s purview. Besides, as others have pointed out, several factors impact how avian influenza spreads between farms, including farm practices.

“It seems clear that farm density in the Fraser Valley has an impact on the infection rate, considering that 12 per cent of Canadian farms are located in British Columbia and that more than 50 per cent of highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks in commercial farms have occurred in BC,” she said. With approximately 600 commercial farms located mostly in a 100-kilometer stretch of Fraser Valley, BC has the highest farm density in the country.

Proximity and density do not necessarily predict infection, though, Racicot said. “Since 2022, 150 commercial farms have been infected in B.C.,” she says. “With the establishment of primary control zones, the CFIA monitored an additional 439 commercial farms in the same region, and

these farms remained negative for avian influenza over the past three years, despite high farm density and sometimes proximity to an infected premise.”

Vaillancourt worries, however, that Canada’s lack of regulatory guidance around barn proximity leaves the industry exposed, especially for high-value breeder operations. “They can follow all the national standards, but those standards were never designed to protect breeding stock,” he says. “They’re the basics.”

The 2012 Ontario court case involving Hybrid Turkeys underscored the limits of relying solely on federal biosecurity protocols. While the new breeder barn met r egulatory requirements, Vaillancourt argued it still posed an unacceptable risk. No rules prevented its construction – just 800 metres from the great grandparent facility.

More than a decade later, that legal gap still leaves breeding farms vulnerable. In the absence of government-led planning, it’s often up to individual producers to assess siting risks, sometimes without the data, tools or authority to push back. “We’re not planning ahead,” Vaillancourt says. “We’re always reacting.”

While Canada continues to rely on a patchwork of local regulations, countries facing similar disease pressures have taken a more centralized and proactive approach. In Italy, for example, rules governing the distance between poultry farms have evolved in response to recurring avian influenza outbreaks. Francesco Galuppo, who works in animal health for the Italian government, explained that proximity rules were not initially part of national disease control strategies.

Regulatory changes came in phases. The first major step was a zoning framework introduced in May 2023 following major outbreaks in 2022, which defined high-risk and surveillance zones. The second was the adoption of strict minimum distances between poultry farms. Farms of over 250 birds are divided into high-risk A and B zones. The rules do not apply to farms with fewer than 250 birds. In both zones A and B, minimum distance is set at 1.5 km, but in B zones no derogations are allowed.

“We’re not planning ahead,” Vaillancourt said. “We’re always reacting.”

Derogations are permissible in A zones. Additional minimum distances are required between poultry farms and pig farms, as well as biogas plants.

While these rules already loosely applied in poultry-dense regions like Veneto, Lombardy and Emilia Romagna – where 70 per cent of Italian poultry production occurs – they now apply nationwide. In densely farmed areas, farmers looking to upgrade are unlikely to receive permits. In Canada, such a system could put farm families out of business. But in Italy’s cooperative-style sector, most farms work for the same company. “What we have is really adapted to the situation we have,” Galuppo says.

When it comes to barn proximity rules, Vaillancourt said the federal government is unlikely to lead. He believes the poultry industry is best positioned to define siting standards based on production type and disease risk. “It has to be industry-driven,” he said. “If it’s not the industry, it won’t happen.” Government’s role, he adds, should be to support enforcement once standards are in place. He pointed to pork as an example. “Swine has been better at this,” he says. “You don’t build next to a nucleus herd. You just don’t.”

As producers continue to grapple with avian influenza, the question of barn proximity remains unresolved in Canada. Distance isn’t a guarantee, but it can be a critical buffer when biosecurity fails. With no national rules and inconsistent oversight, siting decisions are left to individual judgement. Whether the industry will step in remains to be seen.

These exceptional students are the winners of the 2025 CABEF Scholarships. We are proud to support each of them with $2,500 for their ag-related post-secondary education.

Help us empower more students to pursue diverse careers in agri-food. Strengthen the future of Canadian agriculture and food by investing in the cream of the crop.

Become a Champion of CABEF and directly support a scholarship for a Canadian student.

Congratulations to this year’s CABEF scholarship recipients.

Leah Newcombe

Cambridge, NS Allison Morse Hatley, QC

Abbigail Mettler Wallenstein, ON

Messina Schrof Starbuck, MB

Morgan Debenham Kennedy, SK

Colby Scott Hanna, AB

Contact CABEF today to learn how you can become a “Champion of CABEF” at info@cabef.org

By Jane Robinson

Arecent study at Texas A&M

University predicts a rather dire downward trend for broiler breeder hatchability rates in the United States over the next few decades, and raises the call for greater collaboration to change the trajectory.

Dr. Giri Athrey, a geneticist in the department of poultry science at Texas A&M, was one of the authors of the recently published report How concerned should we be about broiler breeder fertility declines? The study analyzed fer tility rates among U.S. broiler breeders from 2013 to 2022 with data from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. With this historical base of information, the researchers used sophisticated modelling to extrapolate what hatchability rates for broiler chicks could be in the future if nothing changed related to breeding, management, etc.

“Our projections indicate the hatchability rate of broiler breeders in the U.S. could decrease to about 60 per cent by 2050 without any corrective action,” says Athrey. “So, y es, we should be concerned.”

As the most consumed animal protein around the globe, the poultry industry is under pressure to produce high-quality chicken to meet growing consumer demand. Athrey’s research looks at unintended effects of the rise in broiler growth rates and feed efficiency in the U.S., and fertility is an issue that’s been on his radar for a while. He wanted to put some estimates on hatchability rates to hopefully give some guidance to the whole industry.

“Fertility is complicated, multifaceted and difficult to measure, so we used hatchability – the number of eggs set

compared to the number of birds placed in broiler production – to infer fertility,” says Athrey.

They created a model called the broiler breeder performance index to better understand the hatchability trends. The index draws several aspects of broiler breeder production – hatchability, chick livability and production efficiency –into a single metric.

“The index is showing us that in the U.S. we are going to have a shortfall in producing enough broilers to meet the growing market demand for chicken,” says Athrey.

He’s quick to acknowledge

that fertility is influenced by many factors, including genetics, nutrition and management, so addressing a downward trend in

hatchability and its implications down the supply chain will require collaboration.

“The U.S. poultry industry is highly vertically integrated and are used to solutions that are compartmentalized. But this deficit can’t be addressed by management alone, or breeding or nutrition,” says Athrey.

In Canada, Dr. Martin Zuidhof doesn’t see the situation for broiler breeder hatchability as dire as the U.S. but acknowledges that it might be time for a bit of a wakeup call for the sector.

He’s been tracking hatchability trends in broiler breeders in Canada and the U.S. over the last decade. “I know the Canadian industry is paying a lot of attention to this and we’re doing about 2 per cent better on hatchability rates than the U.S.,” says Zuidhof, a professor of poultry systems modeling and precision feeding at the University of Alberta.

Fertility is a tough statistic to track, so Zuidhof has been zeroing in on hatchability and feeding management.

“The management of broiler breeder flocks is difficult and a big part of that, I believe, is male uniformity,” says Zuidhof. “If we can keep males to the right body weight, we can get more completed matings to make sure the eggs are fertile. That’s step one.”

Zuidhof is about a year away from commercializing a new precision feeding station for males designed to raise them to a better body weight for breeding. “When we have more uniform weight males, we’ve seen a 4– 6 per cent increase in fertility, compared to conventional feeding management,” says Zuidhof.

Precision feeding that’s targeted just on males could help

Brian Bilkes, CHEP

keep the cost of this new technology within reach for producers. Males represent about 10 per cent of the flock and this new system would potentially only require broiler breeder producers to replace about 10 per cent of their feeding system.

“This system is just one example of the kind of management changes that might make a big differ ence in overall hatchability for the industry,” says Zuidhof.

Brian Bilkes is very interested in the results of Zuidhof’s precision feeding research. Bilkes is chair of the Canadian Hatching Egg Producers (CHEP) and also doesn’t see the situation in Canada as Athrey is predicting for the U.S. “Generally, hatchability in Canada has improved, other than a blip in 2022–2024 when avian influenza resulted in a shortage of hatching eggs.”

Bilkes attributes some of the differences between the two countries to the way the sector is structured. “Unlike some other countries with vertically integrated systems, Canada’s broiler hatching egg farms are independently owned and operated,” says Bilkes. He says that means producers have greater control to optimize fertility outcomes by improving bird management, nutrition, egg handling and biosecurity.

In tracking average hatchability rates across Canada over the past decade, CHEP has seen

a rising trend – from about 81 per cent in 2017 to just under 85 per cent for 2025 (year to date). These numbers reflect the focus producers place on continuous improvement. Bilkes echoes the multifactorial nature of managing broiler breeder fertility. “On-farm practices are vital and so are upstream factors such as genetics and hatchery management. These elements are outside of producers’ direct control and that’s why collaboration across the supply chain is critical to maximize success,” says Bilkes.

That collaboration includes researchers working to improve industry productivity and fertility. “We’re looking forward to results from an in-barn experiment with Martin Zuidhof’s feeding system, to determine how widespread this approach could be on Canadian farms,” says Bilkes.

For Athrey, his report and the collaboration he would love to see throughout the sector comes down to food security. “Poultry is a very affordable protein that is needed around the world – and I’m very interested in finding ways to ensure we can produce enough to meet the demand,” he says.

CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR 2025 HONOUREES

Join us live online, from anywhere, to hear from our today’s most influential leaders and changemakers in Canadian agriculture.

Hear from the 2025 IWCA honourees and other agricultural trailblazers as they share their experiences, triumphs and lessons learned during the virtual IWCA Summit.

Join us for an afternoon of panels, interactive conversation and audience Q&A as our honourees pass down their knowledge, wisdom and advice to other women in agriculture.

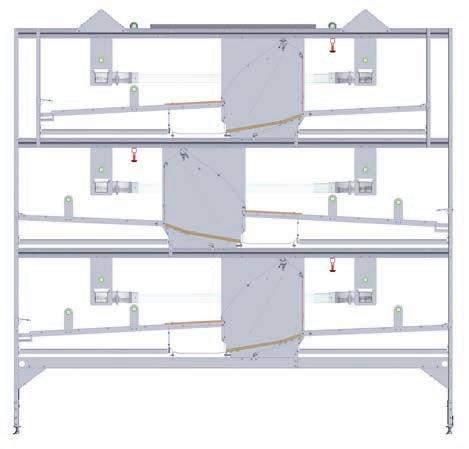

Each option offers pros and cons – but one stands out for breeder layer productivity, bird comfort and long-term ROI.

By Frank Luttels

Today’s growers are presented with multiple nest options for their layers. They can choose nests made of film-faced plywood, plastic or metal. But which one provides the best return on investment? Each material offers distinct advantages and drawbacks. Below is an overview to help choose the right one to maximize productivity and profitability in your operation.

Plastic and metal nests are favored for their smooth surfaces and ease of cleaning. However, one must keep in mind that poultry houses are not cleaned often – only in between flocks when a house is empty. Due to the infrequent nest cleaning, other factors can play a larger role in overall

house hygiene.

Wood, being naturally porous, can absorb moisture. While this property might seem to increase the risk of bacterial growth, research suggests otherwise. The capillary action in wood can help trap bacteria below the surface, where it then dies. With plastic and metal, bacteria stay on the surface, where it has a greater chance of getting picked up by birds, and it can live longer if moisture is present.

This effect can be seen in university research on cutting boards. For instance, a 1994 study, “Cutting Boards and Food Safety,” by Dr. Dean Cliver with the University of Wisconsin, found that bacteria such as Salmonella and E. coli introduced to wooden cutting boards declined significantly over time, even without

cleaning, aided by the porous properties of wood. Dr. Cliver led other r esearch with the University of California, Davis, which had similar findings, showing that plastic cutting boards tended to harbor more bacteria than wood.

Additionally, some types of wood possess natural antimicrobial properties, which can inhibit bacterial growth to an extent. Plastic lacks this ability, which can create a better environment for bacteria to live.

The material used for nests plays a significant role in influencing bird behaviour, contributing to overall productivity in the number of Grade A eggs produced. Wood is generally known to have an advantage here. The weight, density and other

characteristics of wood provide a stable and, most of all, quiet environment for birds. The noise dampening qualities of wood is attributed to higher nest acceptance than both plastic and metal nests.

Wageningen University in the Netherlands reinforced this claim through a study on broiler breeder hens, titled, “Relative

often show minimal signs of deterioration, even with repeated exposure to disinfectants and detergents.

Plastic, on the other hand, degrades over time. After years of pressure washing and exposure to disinfectants and detergents, plastic nests become brittle and are more likely to break. Also, sheet metal options

“The material used for nests plays a significant role in influencing bird behavior, contributing to overall productivity in the number of Grade A eggs produced.”

preference for wooden nests affects nesting behavior of broiler breeders.”

This study compared the number of nest and floor eggs between wooden and plastic nests. It revealed a higher proportion of eggs laid in wooden nests compared to plastic.

Camera data also showed a stronger preference for wooden nests, as more birds visibly spent a greater amount of time in them.

Nests constructed of metal create a very loud environment, which leads to even worse nest acceptance than plastic. Most growers understand this disadvantage and, as a result, metal nests are rarely used in broiler breeder operations today.

An added benefit of wood is its durability. Concerns about potential rot during cleaning are mitigated by the infrequent washing schedules in poultry houses. Since poultr y houses are typically pressure-washed less than once per year, the leng th of exposure to water is minimal. Additionally, these types of nests are made from marine-grade glued plywood with an outer film layer, which is highly suitable for contact with water and wipes down easily when cleaning.

In fact, the porosity of wood is an advantage when it comes to moisture exposure. Even though wood absorbs water, it is also able to dissipate moisture quickly. As a result, wooden nests over 15 years old

tend to rust over time, contributing to durability concerns.

It is important to note that not all wooden nests are created equal. The best options on the market are made with multiple layers of high-quality wood, contributing to the high strength, durability and noise dampening characteristics.

Cheaper versions likely use fewer layers of wood (for instance, five layers of plywood instead of nine), which lessens some of the benefits.

Wood is a renewable resource and can be sourced sustainably, making it a more environmentally friendly option than plastic or metal. This is especially true when sourced from sustainably managed forests.

On the other hand, plastic and metal

nests are produced from fossil fuels and minerals extracted from the earth. Because of this, they can be seen as less environmentally friendly options.

Wooden nests have the highest initial purchase price, followed by plastic and metal. Despite their cost, wooden nests often deliver the best return on investment. Their ability to foster a better environment and improve productivity outweighs concerns about upfront expenses.

Metal nests, though cheaper, are rarely used due to lower returns. Poor nest acceptance and more floor eggs hurt the farm’s profitability.

Given the importance of nests in a poultry house, choosing the right nest material is essential for optimizing productivity and profitability in poultry operations. Overall, film-faced plywood provides better value than plastic and metal alternatives, due to its natural properties that help create a comfortable environment, minimize bacteria growth, increase longevity of the nests and long-term costs. These advantages are often evident by increased bird welfare and a healthier bottom line.

Frank Luttels is the layer product manager for Chore-Time. He has over 25 years’ experience in the agricultural industry, helping develop early cage-free equipment innovations.

smart sensors to AI-powered risk models, a new wave of technologies is transforming how poultry producers protect their flocks

By Mark Beaven

The poultry industry has long recognized that robust biosecurity measures are essential for protecting animal health, ensuring food safety, and maintaining public confidence in our production systems. But as threats like avian influenza (AI), Salmonella, and emerging pathogens grow more complex, traditional protocols are being reimagined through innovation. The future lies not just in boots and disinfectants, but in sensors, satellites, artificial intelligence, and integrated data.

The biggest shift in biosecurity is from reactive to predictive prevention. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) now allow farm management systems to analyze internal and external data – like temperature, mortality, and proximity to wild bird flyways – to deliver real-time risk assessments.

This enables poultry producers to act proactively before a pathogen reaches their barn.

IoT sensor networks track barn conditions and alert managers when thresholds are exceeded. Some also monitor bird weight and behaviour to catch health issues early.

drones, and mapping

Geospatial intelligence is another valuable tool. Satellite and drone imagery can monitor flooding risks, waterfowl areas, and nearby land use – factors that influence pathogen spread. Paired with GIS mapping, this data supports better zoning and containment strategies.

Digital platforms simplify tracking of cleaning routines, visitor logs, vaccinations, and pest control. Cloud-based systems streamline compliance and provide v ital traceability during outbreaks. Increasingly, this transparency is expected by both regulators and global buyers.

Reducing human traffic in barns helps prevent disease. Robots are now performing egg collection, litter management, and monitoring tasks – boosting efficiency

and biosecurity by limiting movement across facilities.

Blockchain is being used to create tamper-proof records across the production chain. From sanitation to vaccination, each step can be logged on a secure ledger – helping build trust in biosecurity practices.

Cleaning and disinfection remain critical. But many traditional chemicals, like quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs), pose health and environmental risks. Newer alternatives – such as hydrogen peroxide and enzyme-based cleaners – are effective and biodegradable, supporting safer and more sustainable operations.

The power of these innovations lies in their integration. A connected system combining sensors, AI, traceability, and automation enables a holistic approach to disease prevention. Collaboration across industry players is key to making these tools usable on real farms.

Canada’s poultry sector is well-positioned to lead in biosecurity innovation. With strong partnerships, high standards, and a willingness to adopt new tools, disease prevention is becoming smarter, faster, and more effective. Biosecurity is evolving from a checklist into a dynamic, data-driven defense system. And the future? It’s already here.

Mark Beaven is president of EthoGuard and a longtime advocate for biosecurity innovation in poultry.

By Treena Hein

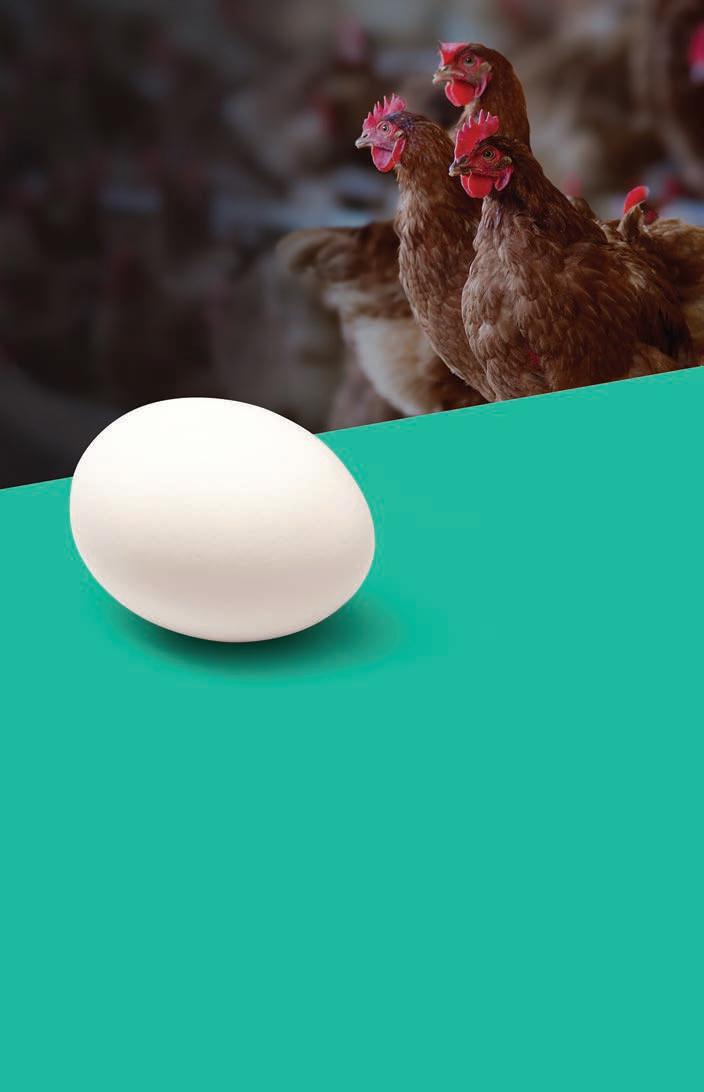

Summer provides a bit of a breather to Canadian poultry farmers in terms of the constant threat of highly-pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) risk, but at the same time, autumn wild bird migration – the time of greatest risk – looms. However, duck farmers in Quebec and across Canada, along with their chicken and turkey peers, are better prepared now than ever.

We know this in part due to a recent report looking at the significant biosecurity changes that commercial duck farmers in Quebec have made over the last two years, captured through detailed surveys and farm visits. Dr. Manon Racicot at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) and Dr. J.P. Vaillancourt at University of Montreal were asked to do this research by the Quebec Ministry of Agriculture (MAPAQ), and results were presented to the industry in June 2025.

MAPAQ instigated the research as duck farms have had proportionally more AI outbreaks than Quebec turkey, egg and broiler farms (although the agency is currently supporting biosecurity research in those sectors). Racicot also notes that most Quebec duck farms are located in local networks where employees and equipment are shared, which adds extra risk.

But first, let’s step back in time for a moment to remember how HPAI severely impacted two Canadian duck producers. In

a Canadian Poultry story from 2022, we learned that during April that year, HPAI was detected in four of 13 production sites at Canards du Lac Brome (Brome Lake Ducks) in Knowlton, Que., including its main site with all parent stock production and hatchery.

At King Cole Ducks in Stouffville, Ont., outbreaks impacted 10 of the 22 farm locations. At each operation, hundreds of thousands of production birds, breeders and eggs were lost – about 85 per cent of birds in total across both companies.

While there’s no complete list of commercial duck producers in Quebec, Racicot and Vaillancourt estimate there are 54 operations, with the recent biosecurity surveys completed by 36 of them (32 duck meat and four breeder operations). “Overall, MAPAQ had the aim of identifying biosecurity gaps, what needs to be changed, where they might assist with investments in training for example, and so on,” Racicot explains.

“Duck producers were very receptive to participation. Before we launched the survey, they gave feedback about the question-

naire to ensure it was thorough, the wording was clear, etc. and all participants filled it out twice, once relating to biosecurity at their operations before 2022 and once for current practices. This took a significant amount of time as there were over 100 questions.”

The survey was done in mid-2024.

Racicot and Vaillancourt used a survey called Biocheck developed at the University of Ghent in Belgium but added to it in areas such as bird movement, barn entrance procedures and bedding. In addition, a different version was given to duck breeders and duck meat producers. It’s a particularly useful survey, says Racicot, as it features a feedback scoring system for each section so producers can benchmark themselves against others.

Looking at results, Racicot first notes that in the big picture, only two Quebec poultry producers have experienced HPAI infections in 2024 and in 2025 so far, with one of those two a duck farm. This demonstrates in her view that the improvements made by duck farmers have already had a big impact. Specifically, in the area of biosecurity ‘organization’ (plans, training and so on),

Racicot calls the improvement “significant.”

The number of duck farms with a written biosecurity plan was found to be 75 per cent in mid-2024 compared to 25 per cent before HPAI outbreaks in 2022. A little over 80 per cent have a training program compared to 43 per cent before. Secondly, looking at barn-level biosecurity, the number of farms with a separation between dirty and clean areas of the barn entry area rose from 29 to 89 per cent. There have also been improvements in the areas of bird movements for gavage (direct transportation, cleanliness verification of crates, etc.).

However, Racicot and Vaillancourt note that overall sector biosecurity improvement opportunities remain in some areas such as bedding management and shipment to slaughter. For example, all ducks in a barn are not always shipped to slaughter at the same time, she says, increasing the likelihood of exposing remaining birds to HPAI. All the survey and farm visit results, including a comparison of biosecurity systems for duck farms that had or did not have HPAI infections, will be submitted for publication in a scientific journal this autumn.

Improvements at two farms

Let’s return to King Cole and Brome Lake for a look inside their updates. At King Cole, already in 2022, leadership ceased production at the original farm where the company’s processing plant is located. Production was spread over a wider area, and to maintain humane transportation for slaughter, transport was changed from open wagons to modules.

Although the company had a very efficient system of shared teams for washing, v accination and overall farm management, this was switched to a siloed system of one manager/one farm and dedicated equipment.

“We had strong biosecurity before AI but the experience of living through an outbreak encourages us all to be extremely vigilant,” says VP of Sales & Marketing Patti Thompson. “Our modules are completely washed and disinfected after every use. As well, our transport trucks and trailers go through an automated wash station after every load to ensure complete

cleaning and disinfection on and under. We also use this system with our other mobile equipment to ensure wheels and undercarriages are fully cleaned.”

Among other changes, bedding storage has been changed from a large single location to individual farm storage units. D utch entrances have been installed at every farm, along with ongoing strict

biosecurity training to ensure that every staff member understands its critical importance. In addition, Thompson also reports that “security cameras and secure access to all barns has been implemented so we can track all people entering our facilities during any time frame very quickly. We can also use this technology to track movement across locations.”

As with King Cole and other duck producers, Brome Lake has ensured changes implemented in 2022, such as adding showers between dirty and clean zones and retraining staff, have become day-to-day operational culture. “We’ve continued to refine protocols, invest in routine and continuous staff education and improve infrastructure to reinforce a culture of continuous vigilance,” reports General Manager Angela Anderson. This includes a review of traffic patterns, new signage and physical barriers.

Brome Lake has also modified the areas in its layer barns where eggs are held prior to pickup. “We built designated zones that allow hatchery staff to collect eggs without ever entering the barn itself, eliminating any direct contact between outside staff and internal barn environments,” explains Anderson. “Once the eggs are picked up, the area is thoroughly disinfected before any egg crates are brought back inside. It’s all

about eliminating risk at every possible touchpoint, no matter how small.”

There has also been a strong focus placed on keeping wild birds/animals off the property, using banger devices during peak migration/nesting periods and predator decoys placed around barns.

Overall, consistency and vigilance are key. “Everyone – from our frontline workers to our suppliers – needs to treat AI risk as an everyday reality, not just a crisis event,” says Anderson. “We’ve also learned that

rapid communication between government, industry groups and producers is key. Having dedicated case managers at CFIA during the last outbreak made a meaningful difference.

“That model should continue and expand. Finally, a clear, science-based framework for risk zones and movement restrictions helps keep everyone on the same page when it matters most.”

In Anderson’s opinion, for producers who are already stretched (especially for those who made huge biosecurity investments post-2022), further upgrades like air filtration systems or new digital surveillance tools may be impossible without assistance.

“Our industry has shouldered an enormous portion of the cost on its own,” she notes. “Grant programs, emergency financial tools and stronger provincial-federal collaboration are essential if we want to keep duck production in Canada viable and competitive.”

Anderson adds that an aligned, national strategy for poultry is needed, with better integration of the duck industry into biosecurity discussions, AI response plans and food autonomy goals. “It also means strategic investment, in vaccine development, in industry research partnerships and in infrastructure to support geographically distributed production that reduces regional viral pressure,” she says.

“Finally, we must build our voice. We’re small but essential to Canada’s food diversity. To grow sustainably and strengthen our biosecurity posture, we need governments and associations to walk alongside us – not just during a crisis, but in the quiet moments before the next one.”

Poultry Spaces highlights new and renovated poultry facilities. Do you know of a good candidate to be featured? Let us know at poultry@annexweb.com.

Location

Lanoraie, Que.

Sector

Layers

The business

Pondoir Beauparlant is a multigenerational table egg operation with deep roots in Lanoraie, Que. Originally started by Gaspard Beauparlant, who sold eggs locally from 300 hens, the farm has steadily expanded its capacity and infrastructure over the decades. Today, the operation is led by William and Camille Beauparlant alongside their parents, François Beauparlant and Sylvie Blain. With five barns and a feed mill onsite, the family manages both pullet rearing and egg production. Over 60 per cent of their flock is housed in free-run systems, with the remainder in enriched or aviary housing.

The need

In 2024, the Beauparlants faced a familiar challenge: what to do with an aging con ventional cage barn that no longer met animal welfare standards under Canada’s new Code of Practice. Rather than

• Agri-fan- Exacon’s brand name since 1987!

• Flush Mount Direct Drive and Belt Drive Exhaust Fans

• Energy Efficient Multifan Motors

decommission the building, they opted to retrofit it. “We didn’t want to scrap the barn,” William explains. “We wanted to find a system that would fit within the existing footprint.”

•Canadian made from 14 gauge stainless steel

•Allows direction of airflow into corners and dead spots

• No CO2 production and reduction of ammonia

• Nonhazardous with no open flame

• Specialized polyurethane formula

• For exceptional insulation properties

• Creates a uniform climate

• Controls humidity at animal level

• Generates real time data

• FarmQuest Online Farm Management allows

• Access to data 24/7

Their solution was the Aviary PRO 12, a new multi-tier system from Hellmann Poultry. While its predecessor, the PRO 11, was too tall for the building, the more compact PRO 12 provided the perfect fit.

The retrofitted barn now houses 8,000 laying hens in an innovative two-tier aviary setup. As the first installation of the PRO 12 system worldwide, William admits it felt like a bold move – but one backed by experience. “We already had a Pro 11 system on another barn, so we were confident this would work,” he says.

The system’s compact layout makes bird monitoring and egg collection easier. “It’s much simpler to check both levels for mortality and maintenance,” says William. The system also includes dual-tier nests that reduce competition among hens and minimize traffic bottlenecks, improving access and reducing stress. Non-nest eggs are gently conveyed by small belts directly to the main egg belt, eliminating manual collection.

The renovation also included new ESA-3000 heat exchangers, known for reducing heating costs and improving air quality. “With layers producing more heat, we don’t need extra heating except in extreme cold,” William notes. LED lighting throughout the system and ceilings further enhances bird welfare and efficiency.

From easier cleaning to better airflow, the Beauparlants believe the barn is now well-positioned for the future. “This system is more efficient, easier to operate, and fits our long-term vision,” William says.

SESSIONS RUNNING THROUGHOUT SEPTEMBER

Join our webinar series designed to deliver fresh insights, proven strategies, and practical solutions for today’s commercial broiler producers.

Topics this year include:

• Ventilation best practices

• Managing lameness in broilers

• Alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters

• Using probiotics to control gut disease

• Preventing heat and cold stress

• Rethinking brooding light programs

• On-farm post-mortems

Webinar Speakers:

• Doug Korver

Alpine Poultry Nutrition

• Jerry Emmanuel

Cargill Animal Nutrition

• Dr. Gigi Lin

Poultry Veterinarian

• Dr. Deborah Adewole

University of Saskatchewan

• Dr. Mohammad Alizadeh

Ontario Veterinary College

• Dr. Jenny Nicholds

Prairie Livestock

Veterinarians

• Dr. Brian Fairchild

University of Georgia

Break the fly reproduction cycle with regular introductions of fly

Effective: Control flies before they mature and breed. Safe: For humans and other animals. Deadly for flies. Natural: Unlike pesticides, no harmful side effects. Economical: Comparable or less cost than pesticides.

The Illustrated Egg Handbook is a colourful guide that gives you a wide range of information on the structure and quality of eggs, as well as what can go wrong. Full of detailed illustrations and tables, this handbook is a perfect guide for people who want to gain knowledge in egg production and quality or even someone that just wants to know more about the inside of an egg. $71.25 | Item#1899043743

By Crystal Mackay

the conversations on food and farming as a keynote speaker and trainer.

Biosecurity. Think about it for a minute. To those unfamiliar with the term, it might sound cold or industrial, or from a laboratory as seen in movies like Jurassic Park

People in the poultry sector know why and how keeping birds healthy is a top priority on many levels. The fundamental principles of caring for animals were rooted in prevention over treatment long before the term biosecurity came about.

When having conversations with someone who doesn’t know poultry farming, it’s important to put the why we use biosecurity measures into perspective. With issues like avian influenza in mainstream media, it’s timely and relatable if you share the why behind the practice.

Here are the top four reasons why we want to keep birds healthy, including biosecurity practices, and how it can be explained in clear and simple terms:

We work hard to keep our birds healthy in many ways. This includes vaccinations and daily care, balanced diets, water and proper housing.

In addition to caring for birds, we use biosecurity, which are management practices designed to protect our flocks from infectious diseases and pests. Biosecurity includes actions like restricting and monitoring barn access, disinfecting barns, equipment and boots, and limiting access to wildlife.

We always prefer prevention over treatment. Fewer diseases means

Conversations that connect:

lower mortality, less medication, and better bird welfare.

Healthier birds mean higher quality meat and eggs, and reduces risks of bacterial contamination.

Good biosecurity includes monitoring bird health regularly, which helps with earlier detection of any potential problems. This is important to minimize and contain any disease, as we have seen with avian influenza.

“We can all build bridges about biosecurity and why it’s so important, one conversation, social media post or presentation at a time.”

Healthy birds mean more reach the market for meat or produce the eggs for us to sell, which is how we make our living.

And for all of the above… Be sure to include your personal

examples to make it real, so it’s not just industry jargon. “On our farm…” “On a farm I visited recently…” “On one of our customer’s farms…”

If you work in the sector and don’t have any personal experience on a farm to know why and how biosecurity works, make a plan to get some! Connect with a farmer to ask them what they do and why on their farms and how it’s made a difference.

We can all build bridges about biosecurity and why it’s so important, one conversation, social media post or presentation at a time.

Can’t get to a farm? Check out Farm & Food Care’s virtual farm tours at farmfood360.ca. Unsure of the terminology? Visit the UTENSIL Plain Language Guide to Food a nd Farming at utensil.ca . It’s searchable by term, acronym and sector – type in poultry!

Reduce mortality

Reduce E. coli associated lesions

Potential to reduce antibiotic use