The Utrecht Historical Student Association 1926-2026

A Century United by History

Part 2 – A Hundred Years of UHSK Students

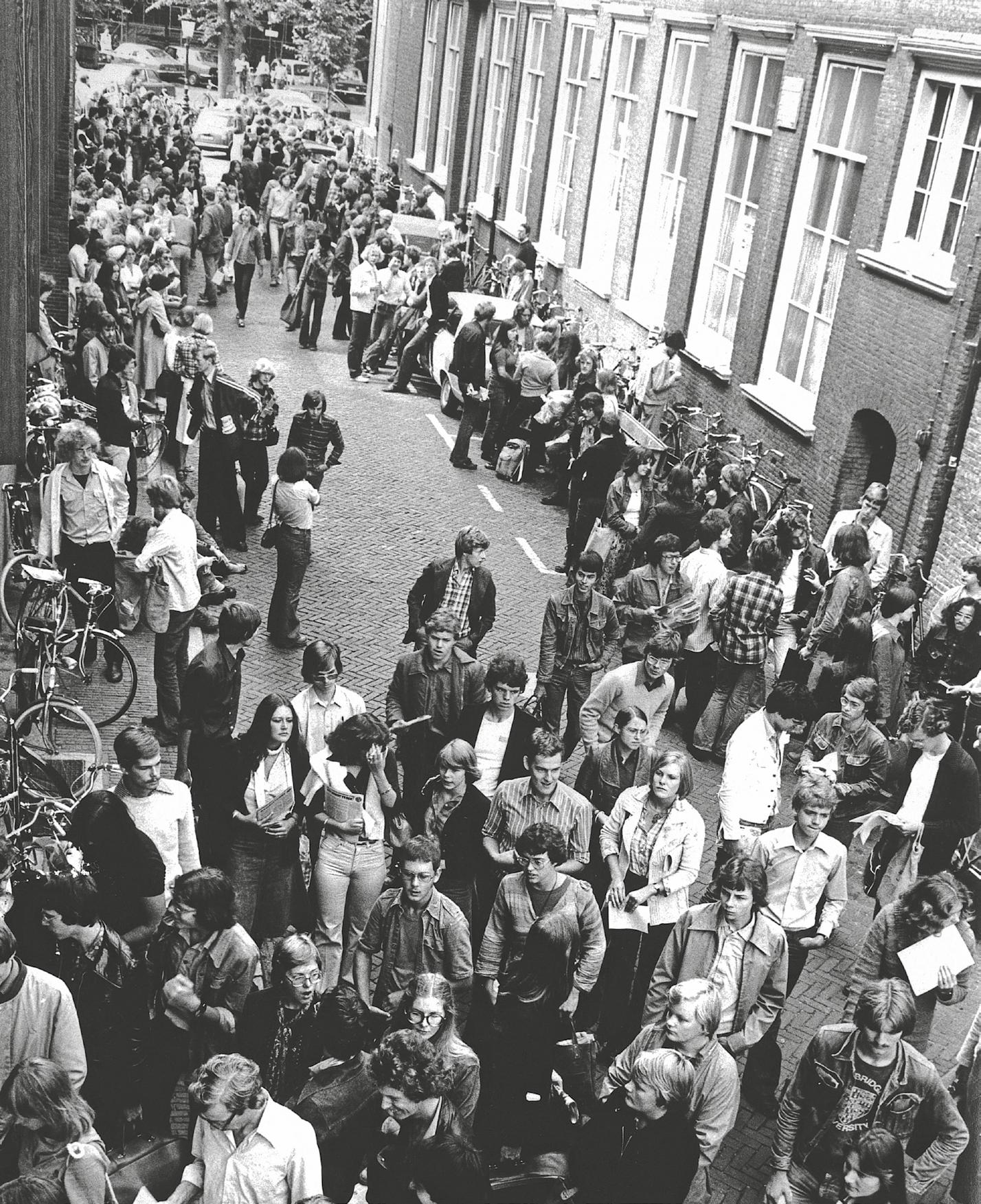

01| The minutes of the founding meeting, Friday 5 March 1926. The board was elected, but the decision on a name of the society was postponed until the meeting of 23 March | Het Utrechts Archief, access no. 1326, inv. no. 1

Introduction

Mette Bruinsma, Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk & Jorrit Steehouder

Historians are not naturally inclined to partying. In addition, many cannot dance, so they stay away or come as wallflowers, which promotes drinking but not the atmosphere. Care should be taken to exclude these people from parties and to encourage those who can dance. EVERY DANCE PARTY AT THE INSTITUTE IS DOOMED TO FAILURE because of the uninviting square room.1

A union for aspiring left-wing historians, a social club where one can enjoy alcoholic refreshments at numerous events, a supplier of discounted textbooks, or a home away from home – the history of the Utrechtse Historische Studenten Kring (UHSK) is not a straightforward story. In its one hundred years of existence, the study association has taken many forms, with different members holding varied perceptions of the association, and its usefulness and role. Because of this multifaceted character of the UHSK, the history of the association offers a valuable insight into the comings and goings of a hundred cohorts of history students in Utrecht. This book therefore tells many small stories about

student life in Utrecht, while also highlighting major shifts in the contents and methods of academic history education, as well as a changing student population.

While this anniversary book focuses on the hundred years during which the UHSK has been associated with academic history at Utrecht University, 2 students were able to study the subject much earlier in Utrecht. The desire to offer students the opportunity to graduate in history dates back to the late nineteenth century, but the Higher Education Act of 1876 precluded this option. As a result, the first history courses were taught as part of other programmes at the Faculty of Arts.3 Only with the amendment of the Academic Statute in 1921 did history – along with several other fields of study – become an independent programme with its own curriculum. 4 In the same year, the Institute for Medieval History was founded, headed by the German medievalist Otto Oppermann. From this moment onwards, Utrecht students could formally enrol as history students at the university.

02 |

the early years

already a mixed group in which many female students also claimed their place. Fourth from the right is former

chair Jo

More about her can be found from page 62 onwards | Unknown photographer | Collection UHSK

A Circle of Students

In the first decades of the twentieth century, student life in Utrecht was mainly organised in large student fraternities and sororities, such as the Utrechtsch Studenten Corps (USC), the Utrechtsche Vrouwen Studenten Vereniging (UVSV), Unitas, and Veritas. Within the USC, there were so-called ‘faculties’ where students could join according to their field of study, such as the Literary Faculty (Litterarische Faculteit).5 For history students in the 1920s, this was the place to enrich their student life. However, the Utrechtsche Studenten Almanak (Utrecht Student Almanac) of 1926 reports about the inability to ‘bring the internal life of the Faculty to greater prosperity’. Students did not seem to realize ‘that an exchange of ideas with

students in a different field of study than their own deepens their own studies’, which meant that the ‘boundaries between the different disciplines’ remained in place.6 It therefore seems that history students minimally engaged with the Literary Faculty.

Thus, on 5 March 1926, “an association of university historians” was founded, without a name.7 According to the founding minutes, one of the founders, T.S. Jansma, suggested that all history students should become members of the Literary Faculty of USC.8 However, this measure failed to accumulate enough votes from the 19 members present. The new association thus did not join the larger student fraternity, which often revolved around ceremony and ritual, and in its early years remained “a sober

Lustrum dinner of 1941. In

of the UHSK, the association was

UHSK

Hollestelle.

society” where everyone was welcome.9 At a later meeting in the same month, the newly founded association was christened:

The next item on the agenda was to give the association a name: after a brief discussion, it was decided to call it “U.H.S.K.” 10

The association now had a name, a board consisting of chairman Gerard Panhuysen and other board members J.J. Beyerman and miss A.M.F. Kluijver. It had already negotiated their first result: “Prof. De Vooys had agreed to organize the exam in interpreting Middle Dutch and 17th-century texts in the old format during the course of the second academic year.” 11 That said, every beginning is difficult. After only six months, Panhuysen requested to be relieved of his chairmanship in accordance

with his graduation, and members began talking about a “reorganisation of the U.H.S.K.” 12

The history of the UHSK has witnessed many moments where the association internally questioned their organisation. Even the role of the board was not sacrosanct; between 1969 and 1992, the association lacked a formal board. The power relations between regular members and the board or ‘steering group’; between committees and the board; and between vocal individuals and the often ‘silent’ majority appears to have been a constant game. Who determines what the association actually is, and what it aspires to be? Is the next board chosen behind closed doors or is this a transparent process accessible even to the less involved members? Is the association there for every history student, or for a specific group, based on political preference,

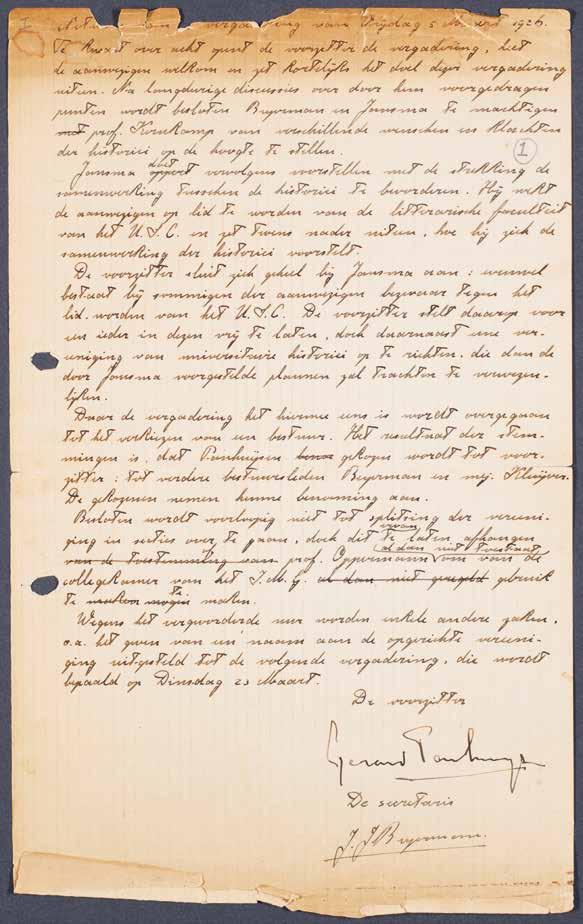

03| UHSK members barbecuing at a youth hostel in Weimar, 1969. Alumni often associate the UHSK with the many study trips that were made: excellent opportunitie for intellectually enriching activities, but, above all, moments when lifelong friendships were forged | Unknown photographer | Collection UHSK

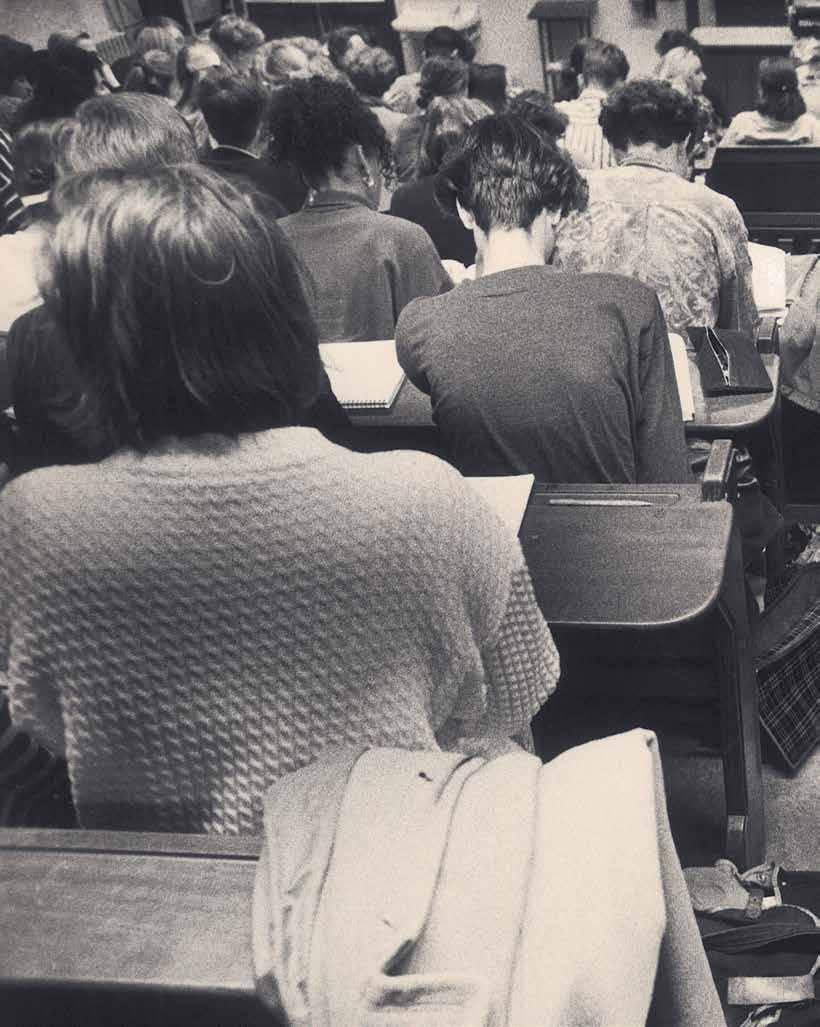

07 | A seminar at the

seminars, and excursions. Not only student life has changed over the past century, but also academic education itself | Maarten

Vondellaan, 1992. Lectures, tutorials,

Hartman | DUB Archive

A Century of Exam Stress: Hundred Cohorts of Utrecht History Students

Mette Bruinsma

Railway students, fraternity members, intellectuals, activists, feminists, bursary students, and nihilists: the history student at Utrecht University cannot be pigeonholed. What unites these groups is their experience with Utrecht’s history education. The duration of their studies has been subject to change. Various policy measures relating to student financing, ‘binding study advice’, and the threat of a so-called ‘long-term study penalty’ have shifted the focus to ‘efficient’ student years. Simultaneously, a shorter period of study, with more emphasis on obtaining credits, has also changed the nature of the student years as a formative period for young adults. Is there still time for self-development, room for experimentation and the evolution of one’s own identity? It is not only the experience of studying that has changed over the past hundred years; the content of the curriculum has also shifted.

This chapter focuses on three aspects of the experiences of a hundred cohorts of aspiring historians: the first part discusses the changing curriculum and

the structure of academic education. What exactly does a history student learn? Is the week filled with lectures, or is autonomous studying expected? Next, the relationship between teachers and students is discussed: whereas in 1926 students could still be asked to attend consultation hours or oral exams at the teacher’s private home, students in 2026 can no longer imagine doing this. In this development, not only the upscaling of higher education, but also its professionalisation and formalisation play a role in this.

How do students relate to lecturers, and vice versa?

Social expectations evolve, as do changes in forms of address: is it acceptable to begin an email to a lecturer with ‘Hey!’, or should it be ‘Dear Professor’? What role did the UHSK play in the relationship between lecturers and students? Finally, this chapter discusses the position of the UHSK within the departmental community. Was the UHSK an advocate for Utrecht history students, a guardian of educational quality, or a sparring partner for

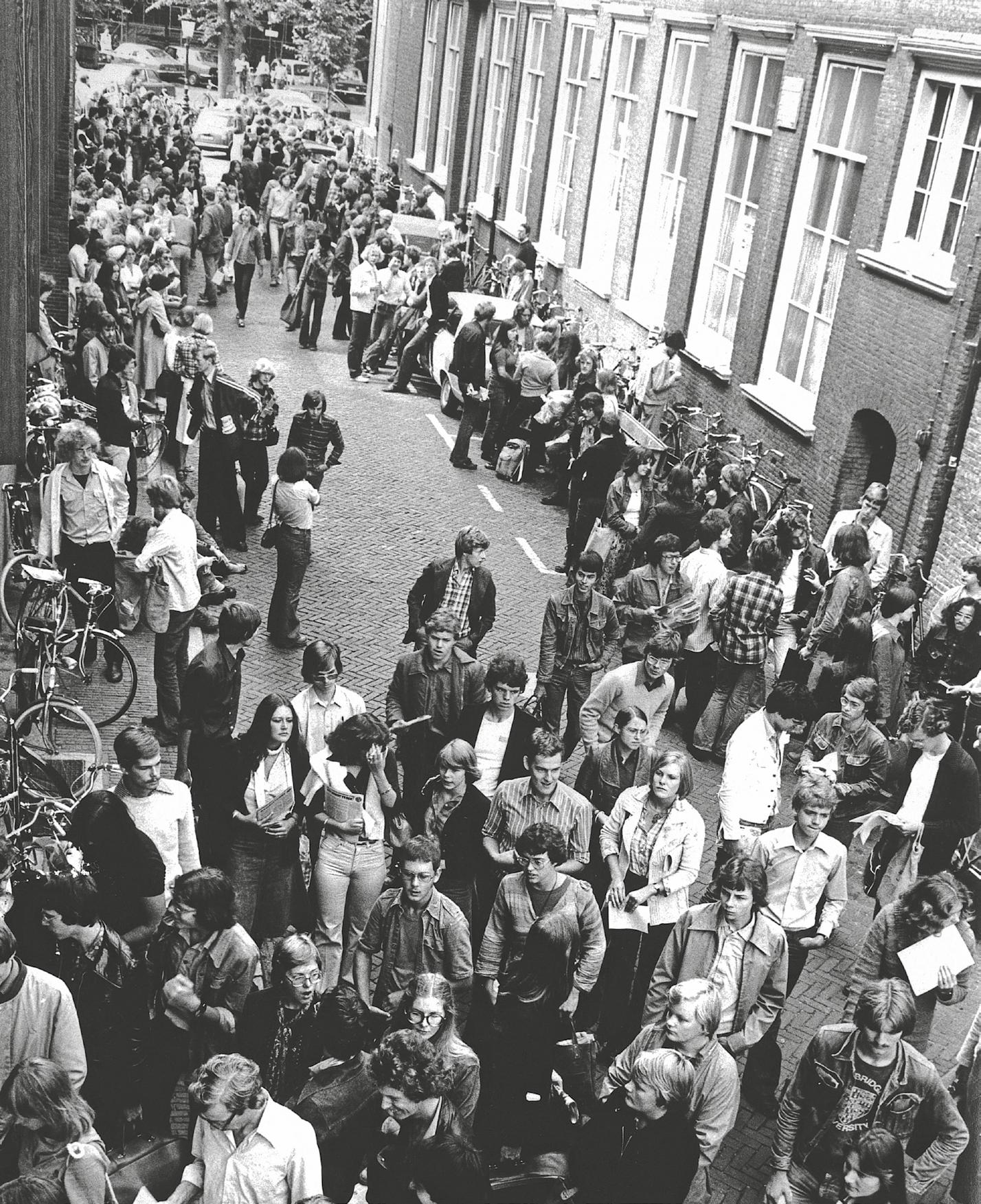

49 | View of the front façades of several buildings on the Drift, 1926. The Drift in Utrecht was where a large part of student life for the first generations of UHSK students took place | Unknown photographer | Het Utrechts Archief

From “Wall Newspaper” to “Social Meeting Place” : A Spatial History of the UHSK

Jorrit Steehouder

“It’s dirty here, a mess, shabby” and ‘you wouldn’t bring your mother here to show her, ‘Mom, this is what your son has achieved’,” said Professor Hans Righart in January 1991 in a plea for a new accommodation for the Institute of History. At the time, Utrecht historians were housed at Lucasbolwerk 5, a fire-hazardous building with serious defects. Every ten minutes, the bus to the Uithof arrived in front of the door with a ‘thunderous roar’. According to Righart, it was also “an antisocial building” that did not encourage “contact between teachers, or between students and teachers”. Regarding his plea, Righart ruled out a return to the “suicidal environment” of the Uithof (where the Institute had been housed from 1980 to 1986).1

Initially, the students endorsed Righart’s arguments, until it became clear that the intended new location at Kromme Nieuwegracht 22 did not include “space for student initiatives”. “Not exactly conducive to social contacts for a study programme with a minimum number of contact hours,” the students commented,

who consequently resisted and successfully managed to change the plans.2 The students demanded a physical space in the same building as their teachers.

The indignant response to the proposed move shows the importance of the physical study environment to the bond between students and vice versa. The Institute’s community, to which the UHSK belonged, was closely linked to the space where staff and students could meet. According to the students, the Lucasbolwerk – despite all its shortcomings – was an important ‘meeting place’ in that respect, where everyone could easily bump into each other at the pigeonholes.3 The UHSK had its own room there, which served as an important meeting place. In addition, student magazines such as the Aanzet and DinaMiek had their own editorial offices.

This chapter focuses on the spatial history of the UHSK. On the one hand, this concerns the actual physical space in which student life took place. Where did students study and where did lectures, readings,

On the Road with Cheese and Buttermilk in Two Volkswagen Vans: UHSK Excursions in the 1950s

Marietje

van Winter

Emeritus Professor Marietje van Winter has been affiliated with the Institute for History in Utrecht since 1953. In 1979, she was appointed professor. Marietje has also been an Honorary Member of the UHSK since 1967.

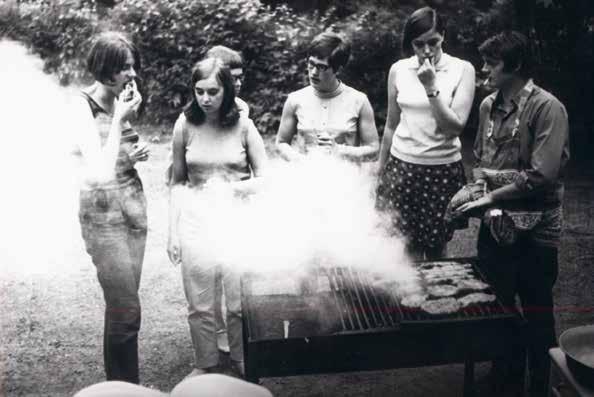

When I started as an assistant in Medieval History in Utrecht in September 1953 after completing my master’s degree in Groningen, the UHSK was only a small group. There were still a few members from before the war, and at most ten first-year students joined each year. They gave lectures to each other, sometimes with a guest speaker from outside: they never went on excursions. Apparently, this was not considered important for historians. The University Fund, which did send art history students to Florence for a month every year, did not provide subsidies for other students. I felt that excursions were just as necessary for history students as they were for art historians, so I introduced them almost immediately.

Our professor of Medieval History, Diederik Enklaar, suffered from multiple sclerosis and was unable to organise excursions himself, but his colleague dr. Jappe Alberts was willing to do so. Our first excursion in the spring of 1955 went to Bonn and Cologne, because Jappe had contacts at the universities there. The group was so small that we could take twelve students with us in two Volkswagen vans. We stayed in youth hostels and took care of our own breakfasts

and lunches as often as we could. Only dinner was in restaurants. I felt that we should eat as healthily as possible, so in addition to cheese and jam, I also bought cucumbers and buttermilk for our bread meals. One of the first participants was Hermann von der Dunk, then a student and later a professor of Modern History and Cultural History, who still teased me about it after many years, when I retired as a professor in December 1988.

Financially, the excursions were a challenge. Students did not receive any subsidies, but Jappe Alberts and I tried to raise our personnel expense allowances as high as possible, so that students could benefit from them. Later, the Institute prohibited this and each student received a subsidy of 10 guilders from the University Fund on the condition that he or she became a donor. A true understanding of the usefulness of excursions for history students had apparently not dawned on them.

Later excursions went to Münster, Ghent, Bruges, Leuven, and Liège, and eventually further afield: across the North Sea to England and, in 1968, to Prague, where we were surprised to find ourselves in the middle of the Prague Spring. We often visited politically controversial areas, such as Berlin and Weimar in the GDR and Budapest in the communist occupation zone. It was useful that our professor of Late Latin, Professor Órban, was of Hungarian descent and could show our Dutch driver the way.

83 | Students travelling to Berlin, likely 1960s. Stops were made along the motorway for breaks and changing drivers | Unknown photographer | Collection UHSK

86 | The UHSK board of the centennium year, 2025-2026 |

Broddi Gautason | Collection UHSK

Epilogue

Daan Groot,

Chair of the UHSK 2025–2026

The UHSK is an association with a long and rich history. Over the course of its now 100-year existence, the association has changed enormously: whereas it once consisted of only a few dozen members, it now counts more than 750 active members. The organisation and public image of the association have also evolved significantly over the past century. Over the years, the UHSK has gone through phases in which it developed as an education-oriented association, a student union, and, today, a professional and inclusive association. However different these periods may appear, there has always been a strong common thread: the desire to be a home for all history students in Utrecht. Over time, this desire has taken different forms, shaped by the changing nature of the “average” history student. This is reflected in the various “phases” of the UHSK described in this book. In each of these phases, this desire was strongly present—and it remains so today.

In a world in which students are constantly confronted with frightening realities such as war, genocide, polarisation, and cuts to university funding, a safe

haven like the UHSK is of great importance. Students deserve a place where they can feel at home, form lifelong friendships, and develop themselves beyond the curriculum. For me, this association has always felt like a second home: a place where I could be myself and create wonderful memories. I believe every student deserves such a haven. The UHSK will continue to strive to be as open and accessible as possible to all its members, whoever they are and whatever they believe.

Just as the first members of the UHSK would hardly recognise the association as it is today, the association will probably look unfamiliar to me fifty years from now as well; after all, the association changes along with its members. The century of history the UHSK has now accumulated is therefore the history of all of its members. I therefore conclude with a word of appreciation to all members of the past, present, and future. Without them, the UHSK would not have become the association that has won a place in our hearts, and thanks to them, the association can certainly continue for at least another hundred years.

Colophon

Publication

WBOOKS, Zwolle info@wbooks.com wbooks.com

Editorial board

Mette Bruinsma, Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk & Jorrit Steehouder

Athors

Mette Bruinsma, Leen Dorsman, Chiara Evans, Beatrice de Graaf, Daan Groot, Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk, Jorrit Steehouder, Aigui Thewissen, Marietje van Winter & Zita Zwart.

Image editors

Mette Bruinsma, Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk, Jorrit Steehouder, Aigui Thewissen & Zita Zwart.

Cover design

Victor de Leeuw, DeLeeuwOntwerper(s)

Design interior and editorial coördination

Crius groep

© 2026 WBOOKS, Zwolle / the authors

All rights reserved. Nothing from this publication may be reproduced, multiplied, stored in an electronic data file, or made public in any form or in any manner, be it electronic, mechanical, through photocopying, recording or in any other way, without the advance written permission of the publisher.

The publisher has endeavoured to settle image rights in accordance with legal requirements. Any party who nevertheless deems they have a claim to certain rights may apply to the publisher.

Copyright of the work of artists affiliated with a CISAC organisation has been arranged with Pictoright of Amsterdam. © c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2026.

ISBN 978 94 625 8766 3 NUR 693

This book was made possible by generous support from the Departement Geschiedenis en Kunstgeschiedenis of the Universiteit Utrecht, the Cultuurfonds, the Professor van Winter Fonds and Fonds Vrienden van het Instituut Geschiedenis Utrecht (VIGU).

The Utrecht Historical Student Association 1926-2026

A Century United by History

The hundred-year history of the Utrecht Historical Student Association (UHSK) demonstrates how vital student associations are in fostering connections between students, lecturers, the university, and the city of Utrecht. This book presents a vivid portrait of many generations of history students as they found their way within the, the university, and the student association. For some students, the association functioned as a trade union for the left-leaning historian-in-the-making; for others, it was a social club that organised drinks and offered discounted textbooks; for some, a “home away from home,” and for many, the place where lifelong friendships were forged.

In-depth essays, personal interviews, and columns reflect on a century of academic education, student life, and changing student populations. There is one constant: within the UHSK, students come together, share experiences, and study history side by side. In short, history as a unifying factor.